Abstract

Objectives

To determine whether adults accurately perceived their weight status category and could report how much they would need to weigh in order to be classified as underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obese.

Research Methods and Procedures

Height and weight were measured on 104 White and African American men and women 45 to 64 years of age living in North Carolina. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated for each participant, and participants were classified as underweight (<18.5), normal weight (≥18.5 to <25.0), overweight (≥25.0 to <30.0), or obese (≥30.0). Participants self-reported their weight status category and how much they would have to weigh to be classified in each weight status category.

Results

Only 22.2% of obese women and 6.7% of obese men correctly classified themselves as obese (weighted kappa: 0.45 in women and 0.31 in men). On average, normal weight women and men were reasonably accurate in their assessment of how much they would need to weigh to be classified as obese; however, obese women and men overestimated the amount. Normal weight women thought they would be obese with a BMI of 28.9 kg/m2, while obese women thought they would be obese with a BMI of 38.2 kg/m2. The estimates were 30.2 kg/m2 and 34.5 kg/m2 for normal weight and obese men, respectively.

Limitations

The sample size was small and was not selected to be representative of North Carolina residents.

Discussion

Obese adults’ inability to correctly classify themselves as obese may result in ignoring health messages about obesity and lack of motivation to reduce weight.

Keywords: Body mass index, body image, body size, awareness, perception

The World Health Organization1 and the National Institutes of Health2 have set clinical guidelines using body mass index (BMI) to categorize adult weight status as underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (≥18.5 to <25.0 kg/m2), overweight (≥25.0 to <30.0 kg/m2), and obese (≥30.0 kg/m2). While these weight status categories are widely used by researchers and clinicians, little is known about whether laypersons can accurately place themselves within these categories. Researchers have shown that adults can self-report their height and weight with reasonable accuracy,3–5 although overweight and obese adults tend to underestimate their body weight while normal weight adults tend to overestimate their body weight. Given the growing obesity epidemic6 and the consequences of obesity,1,7,8 it is important to know how well obesity can be identified in order to design interventions that will reduce the numbers of people who are overweight. If people do not perceive themselves to be overweight or obese, they may not try to lose weight and may not believe that public health messages about obesity apply to them. The objectives of this study were to examine the ability of women and men to accurately (1) self-report their height and weight, (2) perceive their weight status category, and (3) recognize how much they would need to weigh in order to be classified in each weight status category.

METHODS

Study Participants and Recruitment

We recruited a purposive sample of 104 White and African American men and women (26 per race-gender group) 45 to 64 years of age selected to represent a predefined range of BMI levels. Participants were recruited via an email announcement to faculty, staff, and students at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and via flyers distributed in the Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill area of North Carolina. Participants were asked to participate in a study to help improve our understanding of waist measurements and weight maintenance. Exclusion criteria were underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), self-reported poor health, inability to read and write in English, lack of transportation to the General Clinical Research Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and health problems that would cause pain, discomfort, or skin irritation when having waist and hip circumferences or tricep and subscapular skinfolds measured. This study was approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Public Health Institutional Review Board as research involving human subjects.

Anthropometrics

Body weight was measured without shoes on a standard physician’s balance beam scale and was recorded to the nearest pound (1 lb=0.454 kg). Height without shoes was measured to the nearest centimeter (1 cm=0.394 in) using a metal rule attached to a wall and a standard triangular headboard using a vertical ruler. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms (kg) divided by height in meters squared (m2). Based on participants’ measured BMI (kg/m2), they were classified as normal weight, overweight, or obese.

Self-Administered Questionnaire

Prior to the anthropometric measurements, participants completed a brief self-administered questionnaire. Self-reported BMI and weight status categories were based on the participant’s self-reported height (feet and inches) and weight (pounds). Participants were asked, “Would you consider yourself now [underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obese]?” (hereafter described as perceived weight status). They were also asked, “How much would you have to weigh to classify yourself as [underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese]?” (4 separate questions). Since height varied across participants, the reported weights were converted to BMI using the participant’s measured height (hereafter reported as BMI cutpoint for underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obesity).

Statistical Analysis

Differences between self-reported and measured height, weight, and BMI were calculated such that negative values indicated that participants underestimated their actual height, weight, or BMI. Linear regression models (using the PROC GENMOD procedure) were used to estimate (1) the mean difference between self-reported and measured height, weight, and BMI, and (2) the mean reported BMI cutpoint for each weight status category. All models were stratified by gender and adjusted for age and race. The LSMEANS option was used to determine whether the adjusted means differed by measured weight status category. Frequency distribution and corresponding unweighted and weighted kappa statistics were calculated to assess the percent agreement between measured and perceived weight status categories. All analysis was done using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Table 1 shows demographics characteristics in women and men by measured weight status. Normal weight women and men were slightly younger than those women and men who were overweight and obese. Normal weight women and men were predominately White (80.0% and 68.8%, respectively), whereas a substantially lower percentage of obese women and men were White (27.8% and 13.3%, respectively).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics by Measured Weight Status Categories†

| Measured Weight Status Categories | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | |||||

| Normal Weight (n=15) |

Overweight (n=19) |

Obese (n=18) |

Normal Weight (n=16) |

Overweight (n=21) |

Obese (n=15) |

|

| Age: years (SD‡) | 50.9 (4.6) | 53.0 (5.4) | 52.5 (4.5) | 51.5 (5.6) | 55.2 (4.4) | 52.4 (5.9) |

| Race: %White | 80.0 | 47.4 | 27.8 | 68.8 | 61.9 | 13.3 |

| Measured Anthropometrics | ||||||

| Weight: lbs (SD) | 131.2 (14.7) | 164.1 (13.9) | 209.6 (32.3) | 166.2 (18.2) | 194.9 (18.0) | 236.2 (39.0) |

| Height: in (SD) | 64.6 (2.1) | 64.8 (1.9) | 64.2 (2.1) | 70.5 (3.3) | 70.2 (2.8) | 70.3 (2.4) |

| BMI: kg/m2 (SD) | 22.1 (1.8) | 27.4 (1.5) | 35.7 (4.6) | 23.5 (1.0) | 27.8 (1.6) | 33.5 (4.7) |

Measured weight status categories were based on participants’ measured height and weight.

Standard deviation

Self-Reported Versus Measured Weight and Height

Overall, the correlation between self-reported weight, height, and BMI and the measured values were 0.99, 0.91, and 0.99 in women and 0.99, 0.95, and 0.98 in men, respectively. In general, participants tended to slightly underestimate their weight (−0.5 lbs in women and −0.2 lbs inmen) and overestimate their height (0.8 cm in women and 1.0 cm in men) resulting in underestimation of BMI (−0.4 kg/m2 in women and men).

Percent Agreement Between Perceived and Measured Weight Status Categories

The percent agreements between perceived and measured weight status categories for women and men are shown in Table 2. We found that 66.7% of normal weight women and 89.5% of overweight women correctly perceived their weight status category. However, 33.3% of normal weight women considered themselves to be overweight (overreported) and 10.5% of overweight women considered themselves to be normal weight (underreported). In contrast, only 22.2% of obese women considered themselves to be obese. Seventy-two percent of obese women considered themselves to be overweight and 5.6% perceived themselves as normal weight. In normal weight men, 75.0% correctly identified themselves as normal weight, 12.5% underreported, and another 12.5% overreported their weight status. However, 42.9% of overweight men considered themselves to be normal weight, and 57.1% correctly perceived themselves as overweight. Only 6.7% of the obese men considered themselves to be obese. Similar to women, the majority (73.3%) classified themselves as overweight, and 20% considered themselves to be normal weight.

Table 2.

| Measured Weight Status Categories | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | |||||

| Perceived Weight Status Categories |

Normal Weight (n=15) |

Overweight (n=19) |

Obese (n=18) |

Normal Weight (n=16) |

Overweight (n=21) |

Obese (n=15) |

| Underweight | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Normal Weight | 66.7 | 10.5 | 5.6 | 75.0 | 42.9 | 20.0 |

| Overweight | 33.3 | 89.5 | 72.2 | 12.5 | 57.1 | 73.3 |

| Obese | 0.0 | 0.0 | 22.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 |

| (kappa=0.38; weighted kappa=0.45) | (kappa=0.21; weighted kappa=0.31) | |||||

Perceived weight status categories were based on participants’ response to the question,“Would you consider yourself now [underweight, normal weight, overweight or obese]?”

Measured weight status categories were based on participants’ measured height and weight.

Reported BMI Cutpoints for Underweight, Normal Weight, Overweight, and Obesity

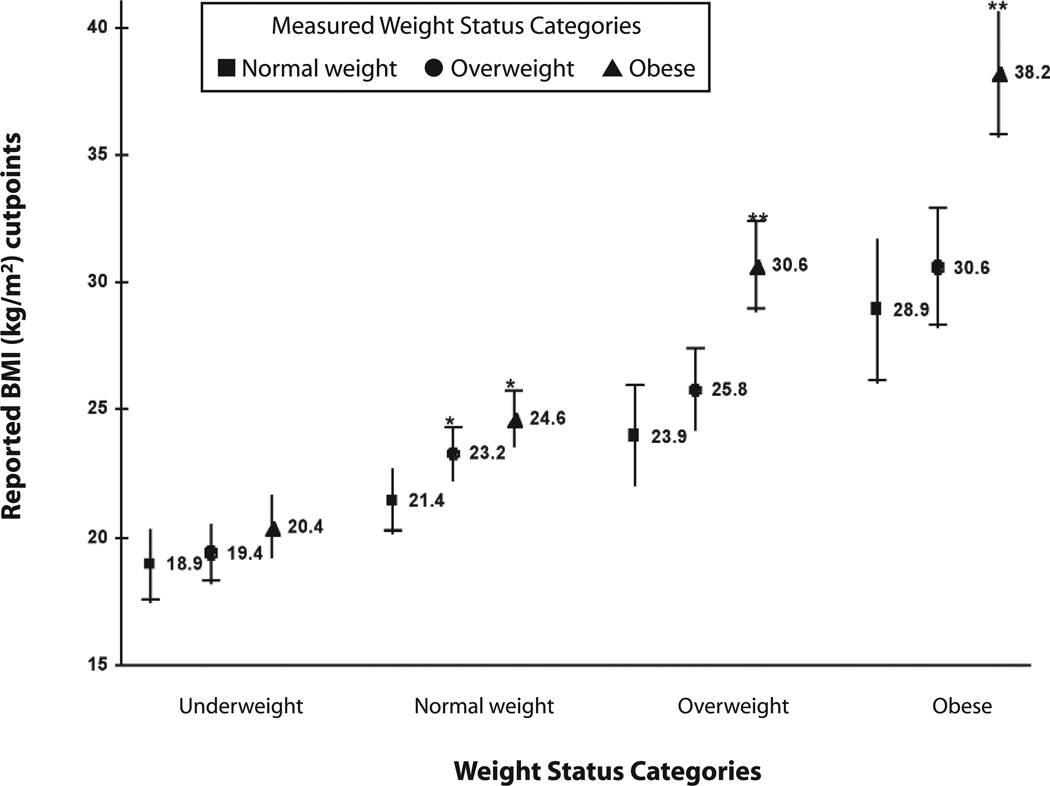

The reported BMI cutpoint for underweight was similar across measured weight status categories. (See Figure 1.) Overweight and obese women’s reported BMI cutpoints for normal weight (23.2 kg/m2 and 24.6 kg/m2) were within the normal weight definition but were significantly higher than BMI cutpoints reported by normal weight women (21.2 kg/m2). The magnitude of the differences reported by normal weight and overweight women compared to obese women increased when examining the BMI cutpoints for overweight and obesity.

Figure 1.

Reported BMI Cutpoints for Underweight, Normal Weight, Overweight, and Obese in Women by Measured Weight Status Category (Models were Adjusted for Age and Race.)

* Significantly different (p<0.05) than normal weight women.

** Significantly different (p<0.05) than normal weight and overweight women.

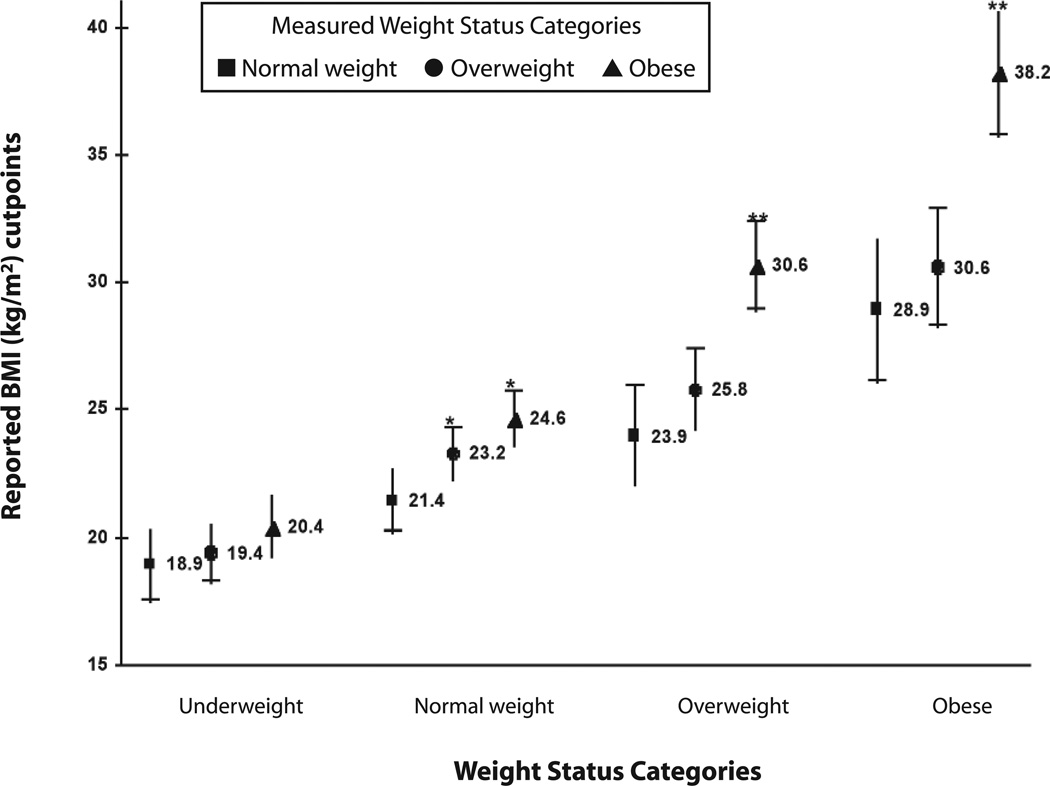

The discrepancies in the reported BMI cutpoints for underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obesity across measured weight status categories appeared smaller in men (see Figure 2) than in women. Reported BMI cutpoints for underweight and normal weight among obese men (23.9 and 26.7 kg/m2) were significantly larger than for normal weight (20.9 and 23.5 kg/m2) and overweight (22.3 and 25.5 kg/m2) men. In addition, obese men’s reporting of BMI cutpoints for overweight and obesity differed significantly from that of normal weight men.

Figure 2.

Reported BMI Cutpoints for Underweight, Normal weight, Overweight, and Obese in Men by Measured Weight Status Category (Models were Adjusted for Age and Race.)

* Significantly different (p<0.05) than normal weight women.

** Significantly different (p<0.05) than normal weight and overweight women.

DISCUSSION

The current study examined the accuracy of self-reported height and weight, perceived weight status category (underweight, normal weight, overweight or obese), and ability to recognize how much one would need to weigh in order to be classified in each weight status category. Our results showed that in general women and men tended to slightly underreport their weight and overreport their height, thus causing BMI to be slightly underreported. These findings are consistent with other studies.3–5,9 Using self-reported weight and height, the majority of subjects would have been categorized into the correct weight status category. In general, the magnitude of underreporting for obesity was greater among women than men (3.9 versus 1.9 percentage points). Similar patterns were found using data from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES III), where the prevalence of obesity was underreported by 4.5 and 6.1 percentage points in White and African American women and 3.2 and 2.3 percentage points in White and African American men10 when they were categorized using BMI from self-reported height and weight.

We saw less accuracy when participants classified themselves into the weight status categories, and 40.4% of women and 51.9% of men misclassified their weight status category. Researchers wanting to classify adults into weight categories should ask participants to report their weight and height and use these data to construct weight status categories rather than asking participants to classify themselves into a category.

Perceptions of how much one needed to weigh in order to be classified in each weight status category varied by gender and measured weight status. Given our findings, a normal weight woman 64 inches (5 ft, 4 in) tall would estimate overweight to be 139 pounds (BMI=23.9 kg/m2) and obesity to be 168 pounds (BMI=28.9 kg/m2), whereas an obese woman of the same height would estimate 178 pounds (BMI=30.6 kg/m2) and 222 pounds (BMI=38.2 kg/m2), respectively. A normal weight man 70 inches (5 ft, 10 in) tall would estimate normal weight to be 164 pounds (BMI=23.5 kg/m2) and obesity to be 210 pounds (BMI=30.2 kg/m2), whereas an obese man of the same height would estimate 186 pounds (BMI=26.7 kg/m2) and 241 pounds (BMI=34.5 kg/m2), respectively.

Other investigators have examined how accurately adults can identify their weight status.11–14 Using data from the NHANES III study, Chang et al found moderate agreement between self-perceived and measured weight status (kappa=0.48 for women and 0.45 for men).11 Approximately 27.5% of women and 29.8% of men misclassified their weight status.11 The smaller percentage of weight status misclassification in the Chang et al study compared to the current study may have been due to the number of categories listed. In the current study, subjects were able to select from 4 weight status categories (underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese) as opposed to the 3 categories used in the NHANES III study.11 Australia’s 1995 National Health Survey and National Survey also used only 3 weight status categories (acceptable weight, underweight, overweight) and found less misclassification (28% of women and 50.7% of men)12 than found in the current study (40.4% of women and 51.9% of men). If we combined the overweight and obese categories in the current study, the misclassification percentage decreased to 15.4% in women and 30.8% in men and the kappa statistics increased in women (unweighted: 0.38 to 0.61, weighted: 0.45 to 0.61) and men (unweighted: 0.21 to 0.40, weighted: 0.31 to 0.43). This suggests that many women may not distinguish between overweight and obesity, whereas many men may not distinguish between normal weight and overweight.

Another possible explanation for the larger percentage of misclassification in the current study is the use of the term obese as one of the weight status categories. Wardle et al found that approximately 35% of men and women misclassified their weight status;13 however, the largest weight status category was referred to as very overweight instead of obese. In a study of Dutch men and women, Blokstra et al asked participants to describe their weight status as too fat, too thin, or just right.14 The majority of normal weight men (79.2%) and women (73.3%) considered their weight to be just right. In addition, the majority of obese men (91.4%) and women (97.2%) considered themselves to be too fat. The findings from these studies suggest that adults may be more reluctant to label themselves obese as opposed to very overweight or too fat.

Blokstra et al asked participants their ideal body weight and converted it to BMI units.14 The reported ideal BMI was higher among obese men and women (27.5 and 27.1 kg/m2) compared to normal weight men and women (22.7 and 21.3 kg/m2). Crawford et al asked participants, “Ideally, how much would you like to weigh at the moment?” and “In your opinion, what is the most you could weigh and still not consider yourself overweight?”15 Using measured heights 1 year prior, the weights were converted into BMI units. The BMIs considered ideal and overweight were 22.7 and 23.7 kg/m2 among women and 24.9 and 26.1 kg/m2 among men. Both estimates increased across measured weight status categories. This is similar to our finding that as weight status increased, the reported BMI cutpoints for each weight status category increased.

Whisenhunt et al asked women to report (given specified heights) the weight range for 6 weight categories (extremely underweight, underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese, and extremely obese).16 They found significant differences between normal weight and overweight participants in the lower and upper BMI cutpoints reported for normal weight, overweight, and obesity. For example, normal weight participants defined normal weight as 19.95 to 22.12 kg/m2 and obesity as 26.75 to 30.83 kg/m2, whereas obese women defined these categories as 21.65 to 24.27 kg/m2 and 32.19 to 37.68 kg/m2. In the current study we did not ask participants for a weight range, therefore it is plausible that differences between the categories could be due to normal weight participants reporting minimum weights and obese participants reporting maximum weights for each category.

Another potential reason for the lower percentage of obese women and men correctly identifying themselves could be their reluctance to report that they are obese to a health care researcher. However, it is important to note that the obese subjects self-reported their current weight and height with reasonable accuracy. The main discrepancy came when they had to put a label on their weight. The term obesity can have social associations such as negative bias, stigma, and discrimination.17 These associations may make adults more reluctant to label themselves as obese. In addition, images of obesity in popular media often show class II or III obesity (BMI≥35.0 kg/m2). This could distort the perceived definition of obesity.

Limitations

This study has limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. The study sample was composed of volunteers living in specific areas of North Carolina and was not selected to be representative of a population. Therefore caution must be used in the generalization of results. Another limitation was the small sample size. We were able to detect some differences by gender and race; however, more subtle trends may have been missed including bias associated with education or employment The study design resulted in unequal distribution of normal weight, overweight, and obese women and men in each race-gender group. It is possible that ethnic differences in attitudes toward weight could have influenced our findings, although we did not find any significant or suggestive race interactions. Other investigators have shown that African American women express a greater amount of body satisfaction and acceptance at higher BMI levels compared to White women.18–23 In addition, other studies have shown that African Americans tend to have lower rates of perceived overweight compared to Whites.24–27

Another limitation is that demographic variables (ie, marital status, education level) that have been shown to be associated with perceived weight status were not collected. Wardle et al found that adults in lower socioeconomic status classes were less likely (OR=0.57, 95% CI: 0.39 – 0.84) to perceive themselves as overweight compared to socioeconomic class 1 and 2 (higher social class).28 Paeratakul et al also found higher rates of self-perceived overweight in adults with higher education level (OR=1.6, 95% CI: 1.1–2.3) and higher income level (OR=1.5, 95% CI: 1.2–1.7).25 This study did not examine why obese women and men did not consider themselves to be obese. Possible reasons include skewed perception, denial, and reluctance to report obesity in a study setting.

CONCLUSIONS

This work suggests that women and men can report their weight and height with reasonable accuracy, but most obese women and men do not consider themselves to be obese. This has implications for research and for public health efforts. Researchers seeking to classify adults into weight status categories will obtain more accurate data by using self-reported weight and height to classify participants than by using self-report of weight status. Public health messages about the consequences of obesity may not reach their targets as obese individuals do not think of themselves as such. More research is needed in larger and more generalizable samples to help our understanding of why obese women and men do not consider themselves to be obese. This will help guide future obesity intervention research.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Eva Katz, the General Clinical Research Center staff, and participants of the study for their important contributions. This research was supported in part by a grant (RR00046) from the General Clinical Research Center’s program of the Division of Research Resources, National Institutes of Health, and by a grant (R01 DK069678) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Contributor Information

Kimberly P. Truesdale, Department of Nutrition in the School of Public Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She can be reached at kim_truesdale (at) unc.edu..

June Stevens, Department of Nutrition in the School of Public Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill..

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic: Report of a WHO Consultation on Obesity. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998. World Health Organization Technical Report Series 894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults - The Evidence Report. Obes Res. 1998;6 Suppl 2:51S–209S. [PubMed]

- 3.Stevens J, Keil JE, Waid LR, Gazes PC. Accuracy of current, 4-year, and 28-year self-reported body weight in an elderly population. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(6):1156–1163. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart AL. The reliability and validity of self-reported weight and height. J Chronic Dis. 1982;35(4):295–309. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(82)90085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stunkard AJ, Albaum JM. The accuracy of self-reported weights. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34(8):1593–1599. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/34.8.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295(13):1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevens J, Truesdale KP. Epidemiology and consequences of obesity. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7(4):438–442. doi: 10.1016/S1091-255X(03)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolf AM, Colditz GA. Current estimates of the economic cost of obesity in the United States. Obes Res. 1998;6(2):97–106. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1998.tb00322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuskowska-Wolk A, Bergstrom R, Bostrom G. Relationship between questionnaire data and medical records of height, weight and body mass index. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1992;16(1):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gillum RF, Sempos CT. Ethnic variation in validity of classification of overweight and obesity using self-reported weight and height in American women and men: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutr J. 2005;4:27. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-4-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang VW, Christakis NA. Self-perception of weight appropriateness in the United States. Amer J Prev Med. 2003;24(4):332–339. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donath SM. Who’s overweight? Comparison of the medical definition and community views. Med J Aust. 2000;172(8):375–377. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb124010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wardle J, Johnson F. Weight and dieting: examining levels of weight concern in British adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26(8):1144–1149. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blokstra A, Burns CM, Seidell JC. Perception of weight status and dieting behaviour in Dutch men and women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(1):7–17. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crawford D, Campbell K. Lay definitions of ideal weight and overweight. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(7):738–745. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whisenhunt BL, Williamson DA. Perceived weight status in normal weight and overweight women. Eat Behav. 2002;3(3):229–238. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(02)00067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puhl RM, Moss-Racusin CA, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Weight stigmatization and bias reduction: perspectives of overweight and obese adults. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(2):347–358. doi: 10.1093/her/cym052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altabe M. Ethnicity and body image: quantitative and qualitative analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 1998;23(2):153–159. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199803)23:2<153::aid-eat5>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flynn KJ, Fitzgibbon M. Body images and obesity risk among black females: a review of the literature. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20(1):13–24. doi: 10.1007/BF02893804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumanyika S, Wilson JF, Guilford-Davenport M. Weight-related attitudes and behaviors of black women. J Am Diet Assoc. 1993;93(4):416–422. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(93)92287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powell AD, Kahn AS. Racial differences in women’s desires to be thin. Int J Eat Disord. 1995;17(2):191–195. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199503)17:2<191::aid-eat2260170213>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith DE, Thompson JK, Raczynski JM, Hilner JE. Body image among men and women in a biracial cohort: the CARDIA Study. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;25(1):71–82. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199901)25:1<71::aid-eat9>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens J, Kumanyika SK, Keil JE. Attitudes toward body size and dieting: differences between elderly black and white women. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(8):1322–1325. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.8.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennett GG, Wolin KY, Goodman M, et al. Attitudes regarding overweight, exercise, and health among Blacks (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17(1):95–101. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-0412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paeratakul S, White MA, Williamson DA, Ryan DH, Bray GA. Sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and BMI in relation to self-perception of overweight. Obes Res. 2002;10(5):345–350. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuchler F, Variyam JN. Mistakes were made: misperception as a barrier to reducing overweight. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(7):856–861. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bennett GG, Wolin KY. Satisfied or unaware? Racial differences in perceived weight status. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3:40. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wardle J, Griffith J. Socioeconomic status and weight control practices in British adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(3):185–190. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.3.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]