Background: Adhesion is a prerequisite to infectious diseases.

Results: A novel streptococcal Galα1–4Gal-recognizing adhesin was identified, which has no homology to known Galα1–4Gal-recognizing proteins.

Conclusion: SadP is an example of convergent evolution of adhesins to binding to the same receptor, Galα1–4Gal, abundant in glycolipids.

Significance: Identification of SadP helps to understand the molecular basis of streptococcal pathogenicity.

Keywords: Adhesion, Carbohydrate-binding Protein, Carbohydrate Structure, Cell Adhesion, Cell Surface Receptor, Glycolipids, Lectin, Bacterial Adhesion, Globotriaosylceramide GbO3, Streptococcus

Abstract

Bacterial adhesion is often a prerequisite for infection, and host cell surface carbohydrates play a major role as adhesion receptors. Streptococci are a leading cause of infectious diseases. However, only few carbohydrate-specific streptococcal adhesins are known. Streptococcus suis is an important pig pathogen and a zoonotic agent causing meningitis in pigs and humans. In this study, we have identified an adhesin that mediates the binding of S. suis to galactosyl-α1–4-galactose (Galα1–4Gal)-containing host receptors. A functionally unknown S. suis cell wall protein (SSU0253), designated here as SadP (streptococcal adhesin P), was identified using a Galα1–4Gal-containing affinity matrix and LC-ESI mass spectrometry. Although the function of the protein was not previously known, it was recently identified as an immunogenic cell wall protein in a proteomic study. Insertional inactivation of the sadP gene abolished S. suis Galα1–4Gal-dependent binding. The adhesin gene sadP was cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli. Characterization of its binding specificity showed that SadP recognizes Galα1–4Gal-oligosaccharides and binds its natural glycolipid receptor, GbO3 (CD77). The N terminus of SadP was shown to contain a Galα1-Gal-binding site and not to have apparent sequence similarity to other bacterial adhesins, including the E. coli P fimbrial adhesins, or to E. coli verotoxin or Pseudomonas aeruginosa lectin I also recognizing the same Galα1–4Gal disaccharide. The SadP and E. coli P adhesins represent a unique example of convergent evolution toward binding to the same host receptor structure.

Introduction

Streptococcus suis is an important emerging worldwide pig pathogen and zoonotic agent causing severe meningitis, pneumonia, and sepsis in pigs and also meningitis in humans. S. suis is an invaluable model for streptococcal infections because infection studies and modern genome-wide screens can be and have been conducted in the natural host (1–4). Polysaccharide capsule, muramidase-released protein, extracellular protein factor, peptidoglycan N-deacetylase, and suilysin are among the known virulence factors, and newly emerging pathogenic mechanisms have recently been found (5–10). From 33 different capsular polysaccharide-based serotypes, S. suis serotype 2 strains have been thought to be the most virulent, and this is a major type isolated from zoonosis (9). S. suis is an emerging pathogen and has recently been reported as the primary pathogen of adult meningitis in Vietnam (11). A recent outbreak in China was caused by type 2 strains and was associated with high mortality to humans (12). In addition to individual virulence factors, pathogenicity islands and islands for pilus biogenesis have recently been identified (13–15).

Bacterial adhesion is an important step in the bacterial infection process. Adhesion to specific cell surface receptors, such as glycoconjugates (e.g. glycolipids and glycoproteins) and extracellular matrix molecules, prevents clearance by the host mucociliary defense mechanisms, aids bacterial invasion into cells, and has a role determining bacterial tissue tropism and host specificity (16–18). Because of an urgent need for alternative antimicrobial therapies beyond antibiotics, there is a need to develop efficient antiadhesion compounds. Soluble oligosaccharides and their derivatives offer novel approaches to prevent infectious diseases by inhibiting adhesion of microbes to cell surfaces (16, 17, 19, 20). Furthermore, bacterial adhesins are promising targets for antimicrobial drugs, because their biological function (i.e. recognition of the receptor) remains conserved, although they may undergo substantial sequence variation (21). Because the chemical structures of adhesin inhibitors are similar to the natural attachment ligands used by bacteria, it is unlikely that resistance would give the bacteria the capability to overcome the inhibitory effect of the antiadhesive drug without impairing their ability to adhere and colonize the host (22).

We have previously characterized in S. suis an adhesion activity to Galα1–4Galβ1 (galabiose)-containing glycolipids (23, 24). Galabiose occurs as a terminal or internal structure in Globo-series glycolipids, and in humans they form the blood group P antigen system. Globo-series glycolipids are also receptors for uropathogenic Escherichia coli P fimbriae, as well as Shiga toxins of Shigella dysenteriae and verotoxins of E. coli O157 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa lectin I (25–28).

In this study, we have identified a previously functionally unknown protein (SSU2053) as the adhesin mediating the Galα1–4Gal-specific adhesion activity of S. suis. This protein, designated here as SadP (streptococcal adhesin P) has previously been studied as a vaccine candidate inducing protective immunity (29). SadP is a unique bacterial adhesin with no apparent sequence similarity with the Galα1–4Galβ1-specific E. coli P fimbrial adhesins; therefore, these adhesins have evolved through convergent evolution in the two Gram-positive and -negative bacterial species for binding to the same host receptor.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains

Hemagglutination-positive S. suis strains have been described before (24, 30) (supplemental Table S1). The genome of S. suis strain P1/7 has been sequenced by the S. suis Sequencing Group at the Sanger Institute. Bacteria were grown in Todd Hewitt broth supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract (THY) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. S. suis strains hemagglutinating weakly due to phase variation were subjected to enrichment of hemagglutinating bacteria by adsorption to human blood group B+ erythrocytes as described before (23). E. coli were grown in Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract and with 1.5% agar for plates. Antibiotics were used at concentrations of 30 or 50 μg/ml kanamycin, 34 μg/ml chloramphenicol, and 12.5 μg/ml tetracyclin for E. coli and 500 μg/ml kanamycin for S. suis.

Purification of the Columba livia Egg White Ovomucoid and Coupling of the Ovomucoid to the Affinity Chromatography Matrix

Pigeon ovomucoid containing terminal Galα1–4Gal residues was purified as described before (31). Briefly, 1 g of lyophilized pigeon egg white was dissolved into 100 ml of water. Crude pigeon ovomucoid preparation was obtained by mixing 1 volume of egg white with 1 volume of 0.5 m trichloroacetic acid/acetone (1:2, v/v) on ice. The mixture was centrifuged at 5000 × g, +4 °C for 20 min. The supernatant was mixed with 2 volumes of ice-cold acetone, and after centrifugation, the precipitated crude pigeon ovomucoid was lyophilized and dialyzed 48 h against water. Pigeon ovomucoid was further purified with anion chromatography using a Resource Q column (GE Healthcare). The fractions were tested for hemagglutination inhibition, and fractions containing ovomucoid were pooled, dialyzed against water, lyophilized, and stored at −20 °C. To prepare an affinity matrix for adhesin purification, pigeon ovomucoid was coupled to 1 ml of Affi-Gel 15 (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Coupling in the presence of 0.1 m MOPS, pH 7.5, 0.6 m NaCl resulted in the incorporation of 6 mg of pigeon ovomucoid/ml of gel. As a control, bovine fetuin (Sigma) was coupled to Affi-Gel 15 using the same conditions (8 mg of protein/ml of gel). The coupling was monitored using the Bio-Rad protein assay.

Affinity Purification of the Galabiose-binding Proteins of S. suis

S. suis strain D282 was grown for 9 h in THY, and the cultured cells were used to inoculate 250 ml of fresh medium. The bacteria were grown to an A600 of 0.5 and centrifuged at 2000 × g, +4 °C for 20 min. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.15 m NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 8.1 mm Na2HPO4, 1.5 mm KH2PO4), the bacteria were suspended into 2.5 ml of cell wall extraction buffer (30% sucrose in PBS supplemented with EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science)). The bacteria were incubated with 4 mg/ml lysozyme at 37 °C for 75 min with gentle mixing. The cell wall extract was obtained by centrifugation of the lysate suspension twice at 16,000 × g, +4 °C. The PD-10 desalting column (Amersham Biosciences) was utilized to exchange the buffer to plain PBS buffer. The cell wall extract was incubated in batch with 150 μl of pigeon ovomucoid-coupled Affi-Gel 15 at +8 °C for 2 h with gentle mixing. Bovine fetuin-coupled Affi-Gel 15 was used as a control. The matrix was washed three times with PBS at +4 °C. The ovomucoid-binding proteins were separated from the affinity matrix by boiling in 150 μl of SDS-PAGE sample buffer for 5 min. After SDS-PAGE, the gel was either silver-stained and the protein bands were processed for LC-ESI-MS3 analysis as described below, or the proteins were transferred to Hybond-P membrane (GE Healthcare) for Western blot probing with biotinylated pigeon ovomucoid.

LC-MS/MS Analysis

Tryptic peptides were dissolved in 10 μl of 2% formic acid, and 5 μl was subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis. The LC-MS/MS analysis was performed on a nanoflow HPLC system (CapLC, Waters) coupled to a QSTAR Pulsar mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex) equipped with a nanoelectrospray ionization source (Proxeon). Peptides were first loaded on a trapping column (0.3 × 5-mm PepMap C18, LC Packings) and subsequently separated inline on a 15-cm C18 column (75 μm × 15 cm, Magic 5 μm 100 Å C18, Michrom BioResources Inc.). The mobile phase consisted of water/acetonitrile (98:2 (v/v)) with 0.2% formic acid (solvent A) or acetonitrile/water (95:5 (v/v)) with 0.2% formic acid (solvent B). A linear 20-min gradient from 2 to 35% B was used to elute peptides.

MS data were acquired automatically using Analyst QS 1.1 software (Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex). An information-dependent acquisition method consisted of a 1-s time-of-flight MS survey scan of mass range 350–1500 m/z and 2-s product ion scans of mass range 50–2000 m/z. The two most intensive peaks over 30 counts, with charge state 2–4, were selected for fragmentation. Once an ion was selected for MS/MS fragmentation, it was put on an exclusion list for 60 s. Curtain gas was set at 20, nitrogen was used as the collision gas, and the ionization voltage used was 2300 V.

Data files were searched for protein identification using in-house Mascot (version 2.2.06). Data were searched against the Sprot-Trembl database (release 2010_07). The following search parameters were used: taxonomy, bacteria (eubacteria) (7185883 sequences); enzyme, trypsin; variable modifications, carbamidomethyl (C), oxidation (M); mass values, monoisotopic; protein mass, unrestricted; peptide mass tolerance, ±0.3 Da; fragment mass tolerance, ±0.3 Da.

Inactivation of sadP by Insertional Mutation

The genomic sequence of SSU0253, the putative galabiose-binding protein, was obtained utilizing Sanger's genome sequence of S. suis strain P1/7, in order to design primers for cloning of an internal fragment of the gene (supplemental Table S2). For insertional mutagenesis, the 433-bp fragment of S. suis D282 was amplified with Phusion high fidelity DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) with primers (SadP-KOs and SadP-KOa, TAG Copenhagen A/S), creating PstI and EcoRI cutting sites. The insert was purified with NucleoSpin Extract II (Macherey-Nagel). Both insert and vector pSF151 were digested with PstI and EcoRI enzymes (Promega) and gel-purified utilizing NucleoSpin Extract II. The insert was cloned to the vector pSF151, and the produced pSadP-KO plasmid was transformed to E. coli DH5α cells. Plasmids were purified from the transformants, and they were analyzed for cloned inserts first by digesting with PstI and EcoRI (Promega). S. suis strain D282 was transformed with plasmid pSadP-KO using the S. suis transformation protocol described before (30), and KanR colonies were selected after a 48-h incubation at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

The insertion of the plasmid pSadP-KO into the putative adhesin gene was verified by PCR using the forward and reverse primers (supplemental Table S2) specific for the vector and primers specific for the insert sequence as described before (32). PCR amplification with sense primer (pSF151MCS) from the pSF151 multiple cloning site and S. suis sense primer (SadPLICs) from the start codon of the gene produced a 0.7-kb product, which confirmed that the plasmid had integrated into the gene annotated as SSU0253.

Inactivation of srtA by Insertional Mutation

An internal 573-bp fragment of srtA was amplified from D282 genomic DNA by PCR using the primers SRTA-5′-KO and SRTA-3′-KO (supplemental Table S2). The resulting PCR product was digested with EcoRI and PstI and cloned into the EcoRI-PstI-digested pSF151, as described above, to generate pSrtA-KO. pSrtA-KO was transformed by electroporation into D282 as described (30), and kanamycin-resistant (KanR) colonies were selected. Insertion of the pSrtA-KO into the genomic srtA was verified by PCR using the primers SRTA-PROM (annealing upstream of the srtA), pSF151-MCS (annealing to the vector DNA), and SRTA-3′-KO.

Expression and Purification of the Truncated SadP Proteins

For expression in E. coli, the S. suis gene SSU0253 was cloned into vector pET-28a (Novagen). The primers SadPs and SadPa (supplemental Table S2) were designed to exclude the N-terminal signal sequence predicted by the SignalP program (available on the World Wide Web, Center for Biological sequence analysis, Technical University of Denmark) and the LPNTG peptidoglycan anchor motif and to contain BamHI and XhoI cutting sites for directional cloning. The 1-kb N-terminal fragment N(31–328) of SadP excluding the C-terminal repeat region was cloned with primers SadPs and N(31–328)a. The gene was amplified with Phusion high fidelity DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) producing a 2.1-kb SadP PCR product or 1-kb N(31–328) product and was cloned into vector pET-28a after purification with NucleoSpin Extract II (Macherey-Nagel). After cloning into pET28a and transformation into E. coli DH5α, plasmids were sequenced and were then transformed to the BL21(DE3) or Novablue(DE3) expression strains (Novagen). The protein was produced in E. coli by growing the bacteria to an A550 of 0.5, inducing with 1 mm IPTG, and growing for 3 h. Harvested bacteria were stored at −70 °C. Bacteria were lysed with 0.2 mg/ml lysozyme in PBS buffer (containing 0.5 m NaCl, 1 mm PMSF, 20 mm imidazole, 20 μg/ml DNase, 1 mm MgCl2). The lysate was centrifuged at 16,000 × g, +7 °C for 20 min and applied onto an Ni2+-NTA affinity chromatography spin column (HisTrap FF, GE Healthcare). The affinity column was washed with PBS buffer containing 20 mm imidazole, and the fusion protein was eluted with 500 mm imidazole. The purified protein was analyzed with SDS-PAGE.

Detection of SadP with Biotinylated Ovomucoid and Western Blot

Pigeon ovomucoid was biotinylated with Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cell wall extracts were separated in SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred with semidry blotting equipment onto Amersham Biosciences Hybond-P membrane (GE Healthcare). For pigeon ovomucoid-biotin probing, the membranes were saturated with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBST buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 0.15 m NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20), for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at +8 °C. The membranes were incubated with biotinylated ovomucoid (700 ng/ml) in TBST buffer for 2 h at room temperature. After washing three times, the membranes were incubated with Amersham Biosciences streptavidin-HRP conjugate (GE Healthcare) in TBST buffer for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, the membranes were developed with ECLTM Western blotting detection reagent (GE Healthcare). Truncated N(31–328) fragment of SadP was separated with native PAGE (4–20% mini-PROTEAN precast gel, Bio-Rad) and was transferred with the Bio-Rad tank transfer system onto nitrocellulose Protran membrane (Whatman). The membrane was saturated with 5% milk powder, 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS for 2 h at room temperature. The saturated membrane was probed with biotinylated ovomucoid (700 ng/ml) in 1% BSA, 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS for 2 h at room temperature. After washing three times, the membrane was incubated with Amersham Biosciences streptavidin-HRP conjugate (GE Healthcare) in 1% BSA, 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS buffer for 1 h at room temperature, and membrane was developed with ECLTM Western blotting detection reagent (GE Healthcare).

Adhesion to Glycoproteins Using Solid Phase Binding Assays

Glycoproteins were adsorbed to MaxiSorp (white) microtiter plates (Nunc) by incubation in sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 0.15 m NaCl overnight at +8 °C in an orbital shaker. Glycoproteins hen egg albumin, porcine thyroglobulin, fetal calf serum fetuin, human milk lactoferrin, invertase from baker's yeast, and asialomucin from bovine submaxillary gland were obtained from Sigma. Galα1–4Gal-containing proteins were Pk-BSA (Carbohydrates International) and pigeon ovomucoid purified as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The unbound proteins were washed with TBS-Tween buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.15 m NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20), and the wells were saturated with 2% BSA in TBS-Tween. After blocking, 10 μg/ml histidine-tagged SadP diluted in TBS-Tween buffer, with or without dilutions of oligosaccharide inhibitors, was allowed to bind to the wells for 2 h at room temperature with shaking. The unbound adhesin was washed with TBS-Tween four times for 5 min. The bound adhesin was detected with anti-His antibody (Sigma; 1:6000) and anti-mouse HRP-coupled antibody (DAKO, 1:2000) diluted in TBS-Tween, 1% BSA. The binding was quantitated by pipetting 100 μl of Pico Supersignal ELISA chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Thermo Scientific) into the wells. The chemiluminescence (expressed in RLU), was analyzed with a Victor2 1420 Multilabel counter (Wallac). All measurements were done as triplicates. The data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism software.

Oligosaccharide Inhibition Assay with Adhesin-coated Europium-labeled Nanoparticles

100 μl of OptiLink carboxylate-modified microparticles (Seradyn, diameter 69 nm, 1% solids) were coated with 1 mg of truncated His-tagged SadP in 1 ml of 0.05 m MES, pH 6.1, according to the manufacturer's instructions. After adsorption, the particles were washed twice by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 1 h at +7 °C and suspended into 1% BSA in TBS-Tween. Black F96 microtiter wells (Nunc) were coated with 50 ng/ml pigeon ovomucoid and blocked with 2% BSA in TBS-Tween. Nanoparticles were diluted 1:400 in TBS-Tween containing 0.2% BSA and incubated in the wells with or without 10-fold dilution series of inhibitors for 2 h at room temperature with shaking. After washing four times with TBS-Tween, the bound nanoparticles were detected with a Victor2 1420 multilabel counter (Wallac; excitation, 340 nm; emission, 615 nm). Each measurement was done in triplicate.

Pigeon Ovomucoid-Adhesin Interaction Analysis by Surface Plasmon Resonance

Purified pigeon ovomucoid was immobilized on a Biacore CM5 sensor chip surface (Biacore) by amine coupling according to the manufacturer's instructions to yield a surface of ∼1500 resonance units. Binding of histidine-tagged SadP and N(31–328) was tested in HBS-P buffer (10 mm Hepes, 0.15 m NaCl, 0.005% P-20, pH 7.4) at a flow rate of 20 μl/min with BiacoreX (Biacore). The activated-deactivated flow cell without any immobilized protein was used as a control. This background signal was subtracted from the signal obtained from the pigeon ovomucoid-coated flow cell before results were used to evaluate binding. Binding kinetics were calculated using BIAevaluation 4.1 software. After each run, the chip was regenerated with 10 mm NaOH (5 μl). The tested galabiose inhibitor was diluted in HBS-P buffer and incubated with the truncated SadP or N(31–328) (10 μg/ml) for 5 min before injection over the sensor chip.

DNA Sequencing and Sequence Analysis

DNA sequencing was done with an ABI PRISM 3130xl® Genetic Analyzer using the dye terminator method. Sequence comparisons were done with Sanger's S. suis genomic sequence database by Blast searches and with NCBI Blast server. Protein sequences were analyzed with the SignalP program for signal peptides, with the Radar analysis program (available on the Expasy proteomics server) for tandem repeats and with the Coils program for coiled-coil regions.

RESULTS

Identification of a Candidate Galα1–4Gal-specific Adhesin of S. suis

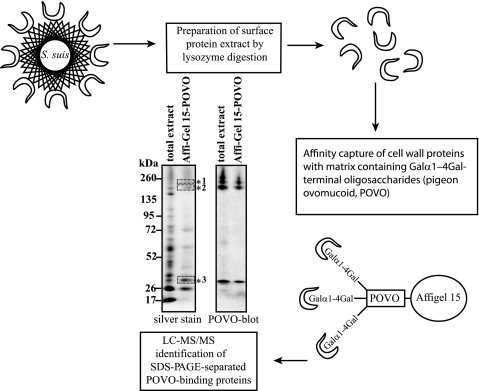

We have earlier shown that trypsin treatment of the bacteria abolishes Galα1–4Gal-dependent hemagglutination, which suggested that the corresponding bacterial adhesin is a protein (33). In this study, we envisioned that lysozyme might solubilize proteins that are either covalently or non-covalently anchored to the cell wall and therefore would allow affinity capture of the Galα1–4Gal-specific adhesin of S. suis. Lysozyme treatment, in the presence of 30% sucrose to prevent lysis of the protoplasts, was able to solubilize material that partially inhibited hemagglutination (data not shown). In the subsequent experiments, affinity purification using pigeon ovomucoid (glycoprotein abundant in Galα1–4Gal-containing N-glycans) coupled to Affi-Gel 15 captured a number of components from the lysozyme extract, among them two major bands of about 200 kDa accompanied by a spectrum of higher molecular weight components in a ladder-like pattern and a band of about 35 kDa (Fig. 1). These protein bands were identified to bind pigeon ovomucoid by probing a PVDF membrane of a replica SDS-PAGE gel with biotinylated pigeon ovomucoid (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the components were absent from a control purification employing fetuin-coupled affinity matrix (supplemental Fig. 1). The high molecular weight components as well as the small component were isolated from the silver-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel and subjected to LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis. Both of the high molecular weight bands binding biotinylated ovomucoid (Fig. 1, *1 and *2) were identified as products of the S. suis gene C5VYS7 (strain P1/7, UniprotKB accession entry SSU0253) with 32% peptide sequence coverage (supplemental Files 1 and 2). A similar spectrum of bands is often seen when cell wall proteins are solubilized with N-acetylmuramidases (34). SSU0253 was predicted to have an N-terminal signal sequence for secreted proteins as well as a C-terminal LPNTG cell wall anchorage motif of Gram-positive bacteria (supplemental Fig. 2). As described below, it was identified as the Galα1–4Gal-specific adhesin and was therefore designated as SadP (streptococcal adhesin P). The 35-kDa protein (Fig. 1, *3) was identified as SSU981782, a gene with homology to an ABC-type periplasmic component of a metal ion transporter (supplemental File 3).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic diagram of the strategy and identification of the Galα1–4Gal-specific adhesin of S. suis using the pigeon ovomucoid affinity matrix. A proteomics approach combining traditional affinity chromatography and peptide sequencing was applied for the identification of the Galα1–4Gal-specific adhesin of S. suis. The Galα1–4Gal-containing glycoprotein pigeon ovomucoid (POVO) (68) was used as the affinity ligand to isolate cell wall proteins recognizing Galα1–4Gal. Cell wall proteins solubilized with lysozyme treatment from ∼2.2 × 1010 cfu and proteins eluted from 150 μl of pigeon ovomucoid-Affi-Gel 15 matrix by boiling in SDS-sample solution were resolved by SDS-PAGE. The separated proteins were identified with silver staining of the gel and by probing with biotinylated pigeon ovomucoid after transfer onto PVDF membrane. Two high molecular weight bands (*1 and *2) with an approximate size of 200 kDa and one protein band (*3) of 35 kDa were excised from the silver-stained gel and were identified with LC-ESI-MS/MS.

Genetic Identification of SadP as the Galα1–4Gal-specific Adhesin of S. suis

Agglutination of sialidase-treated human erythrocytes is dependent on the recognition of Galα1–4Gal-glycans by S. suis. To genetically show that SadP is the Galα1–4Gal-binding adhesin, we generated SadP-deficient mutants by insertional inactivation. Because insertion of suicide vector containing transcriptional terminator could terminate the transcription of genes downstream of the knock-out gene, causing a polar effect, the genomic region of sadP (Fig. 2) was analyzed for possible polycistronic operons, promoter sequences, and terminators. SadP was not located in an operon, and promoter sequences typical for Gram-positive bacteria upstream of the gene and a Rho-independent terminator were predicted using the program Brom on the Softberry server. This suggests that disruption of the adhesin gene most likely would not cause a polar effect. The wild-type S. suis D282 strain strongly agglutinated human erythrocytes, whereas strain D282 with knock-out in SadP was clearly negative (Fig. 3A). Four independent insertional mutants of the sadP gene of strain D282 and two independent insertion mutants of strain P1/7 that were verified by PCR (supplemental Fig. 3, A–C) were all hemagglutination-negative. These findings strongly indicate that pleiotropic effects did not cause the hemagglutination-negative phenotypes and that sadP was the Galα1–4Gal-specific adhesin of S. suis. An insertional mutant of the gene encoding for the 35-kDa pigeon ovomucoid-binding protein SSU981782 (Fig. 1, *3) was hemagglutination-positive, which indicated that this molecule did not mediate Galα1–4Gal-dependent hemagglutination (Fig. 3A). In previous studies, we have also identified in S. suis the protein Dpr (Dps-like peroxide resistance protein) as a pigeon ovomucoid-binding molecule (35). As shown in Fig. 3A, the allelic replacement mutant D282-Δdpr (30) as well as the insertional mutant D282-33 (36), both lacking Dpr, were still agglutinating erythrocytes, which suggests that dpr is not responsible for the Galα1–4Gal-specific hemagglutination phenotype of S. suis strain D282.

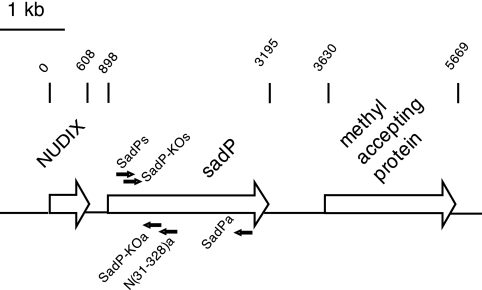

FIGURE 2.

Genomic organization of the sadP region of S. suis strain P1/7. A gene annotated as SSU0253, predicted to code a functionally unknown LPNTG-anchored protein, was identified with LC-MS/MS analysis as described in the legend to Fig. 1 and was designated as sadP. In the S. suis P1/7 genomic sequence, the gene upstream of the sadP codes for a hypothetical protein belonging to an NPT hydrolase family (NUDIX). The downstream gene of sadP codes for a methyl-accepting protein. Sequencing of the chromosomal region of S. suis D282 sadP revealed an identical genomic organization.

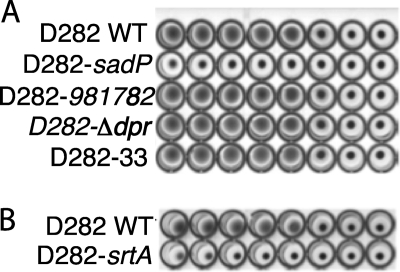

FIGURE 3.

Characterization of S. suis D282-sadP and S. suis D282-srtA knock-out strains. A, the phenotype of the S. suis D282-sadP knock-out strain, after the insertion of the suicide vector into the sadP (supplemental Fig. 3) was confirmed, was tested in a 96-well microtiter plate hemagglutination assay. 5 × 109 cfu/ml of bacteria were 2-fold diluted in microtiter wells and were then mixed with sialidase-treated erythrocytes (2.5% (v/v) final concentration). Wild-type S. suis D282 strain caused a positive reaction up to a concentration of 3 × 108 cfu/ml whereas the D282-sadP knock-out strain was negative even in the lowest dilution. Strain D282-981782 is an insertional knock-out mutant of the 35-kDa pigeon ovomucoid-binding protein (*3 in Fig. 1). Strain D282-Δdpr is a full deletion mutant, and D282-33 is an insertional mutant of S. suis dpr, which encodes for a bacterial ferritin-like protein Dpr required for H2O2 resistance of catalase-negative S. suis (30, 36), previously identified as a pigeon ovomucoid-binding protein (35). B, wild-type S. suis D282 strain caused a positive reaction up to a concentration of 3 × 108 cfu/ml whereas the sortase A-negative D282-srtA knock-out strain was negative.

Because SadP was identified as a cell wall-anchored protein based on its extraction by lysozyme and on the presence of an N-terminal signal peptide for secretion and a C-terminal LPNTG motif, we generated a sortase A-deficient mutant of strain D282 by insertional inactivation (supplemental Fig. 3D). Sortases catalyze the covalent linkage of secreted proteins via the LPNTG motif into the peptidoglycan cell wall, and SrtA has been reported to be functionally a major sortase isoform in S. suis (37). As shown in Fig. 3B, the SrtA knock-out mutant was hemagglutination-negative. The data indicate that the Galα1–4Gal-binding adhesin is processed by conventional SrtA-mediated cell wall anchoring and genetically add further proof that SadP is the Galα1–4Gal-binding adhesin of S. suis. The genomic organization of srtA in S. suis genomic locus NCTC10234 (nucleotide accession code AB066353) indicates that the hemagglutination-negative phenotype due to disruption of the srtA gene in strain D282 most likely was not the cause of a polar effect to the downstream genes in the srtA mutant (supplemental Fig. 3E).

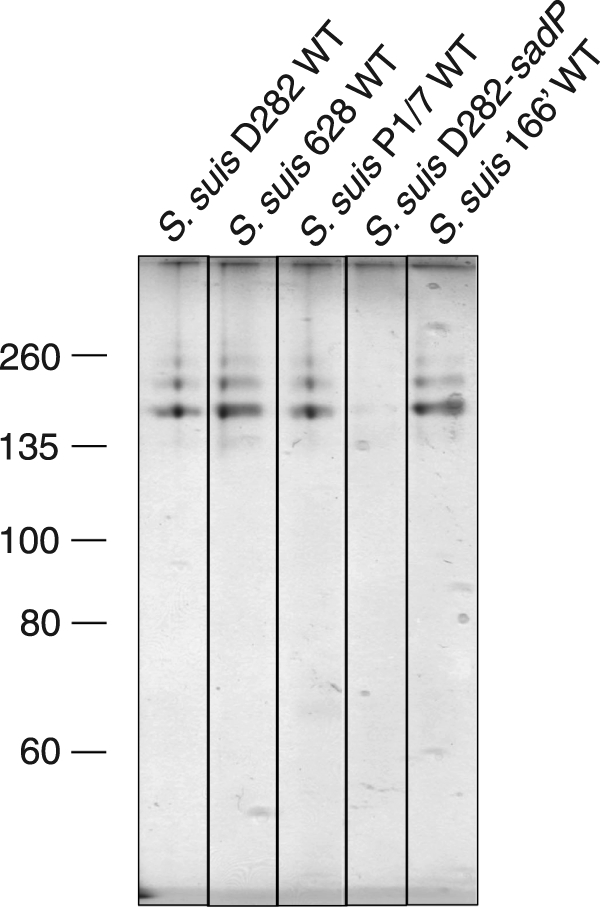

SadP Expression in Different S. suis Strains

Pigeon ovomucoid affinity capture assays were done with known hemagglutination-positive wild-type serotype 2 strains D282, 628, P1/7, and mutant D282-sadP as well as with wild-type serotype 2 strain 166′, shown recently to be highly virulent for pigs (38, 39). The cleared lysozyme extracts of the bacteria were incubated with pigeon ovomucoid affinity matrix, and the bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4). Silver staining revealed similar ladder-like high molecular weight bands in all the wild-type strains, whereas the knock-out mutant D282-sadP completely lacked these bands (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Pigeon ovomucoid-binding proteins of wild-type S. suis and SadP knock-out strain. Cell wall proteins of the Galα1–4Gal-specific hemagglutination-positive serotype 2 strains D282, 628, and P1/7 and a hemagglutination-negative invasive clinical type 2 strain 166′ were solubilized with lysozyme and incubated with the pigeon ovomucoid Affi-Gel matrix. The bound proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected with silver staining.

Expression of the Recombinant SadP

The predicted size of SadP excluding the signal sequence and the C-terminal LPNTG anchor motif (for the amino acid sequence, see supplemental Fig. 2) was calculated to be 76,332 Da. The truncated fusion protein cloned in frame with histidine and S-tags in plasmid pET-28a (without signal sequence and LPNTG anchor motif) had a predicted size of 79,600 Da. The apparent molecular sizes in SDS-PAGE of the proteins purified from S. suis (Fig. 1, *1 and *2) and of the recombinant protein (supplemental Fig. 4A) indicate much higher molecular weight, which suggests that SadP may form a structure consisting of tightly associated monomers (possibly a trimer) that resists denaturing conditions. Indeed, LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis of recombinant SadP (data not shown) did not reveal any traces of other proteins, which appears to rule out a possibility of a tightly associated and co-purifying component. Furthermore, two of the components (Fig. 1, *1 and *2) of the high molecular weight ladder were both identified as SadP with no clear indication of additional peptide components. Pigeon ovomucoid probing of D282 lysozyme extract and recombinant SadP (supplemental Fig. 4B) showed that both the native SadP and the recombinant protein have the same mobility in native PAGE, which suggests that they fold and form multimers in the same fashion.

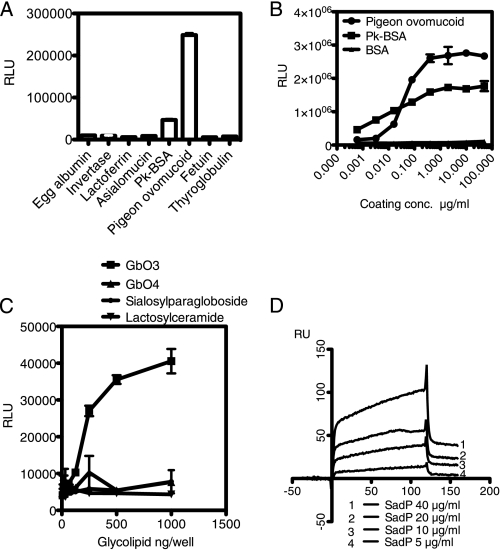

SadP Binds to Galα1–4Gal-containing Glycoproteins and Glycolipids

We have previously shown that whole S. suis bacteria bind to Galα1–4Gal-terminating glycoproteins in solid phase binding assays (24). S. suis SadP bound to pigeon ovomucoid and Pk-BSA neoglycoprotein conjugate (Pk-BSA) but not to the control glycoprotein hen egg ovalbumin and invertase containing high mannose glycans, human lactoferrin with Fucα1–3-residues, bovine submandibular asialomucin with GalNAcα1 residues in O-glycans, bovine fetuin containing terminal NeuNAcα2–3/6-linked residues, or porcine thyroglobulin with terminal Galα1–3Gal-residues (Fig. 5A). His-tagged SadP fusion protein bound dose-dependently to pigeon ovomucoid and Pk-BSA (Fig. 5B). SadP bound strongly to the glycolipid trihexosylceramide, Galα1-Galβ1–4Glcβ1-O-Cer, and weakly to globoside, containing internal Galα1–4Gal. As a control, SadP did not bind to lactosylceramide (Galβ1–4Galβ1-O-Cer) and sialosylparagloboside (NeuAcα2–6Galβ1–4GlcNAβ1–3Galβ1–4Glcβ1-O-Cer) (Fig. 5C). In addition, in a surface plasmon resonance assay, SadP bound to pigeon ovomucoid in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5D). Altogether, these results give biochemical support to the genetic evidence that SadP is the Galα1–4Gal-binding adhesin of S. suis.

FIGURE 5.

Characterization of the binding of SadP fusion protein to Galα1–4Gal-containing glycoproteins and glycolipids. A, Ni2+-NTA affinity chromatography-purified SadP (10 μg/ml) was applied into microtiter wells coated with the glycoconjugates indicated. Binding of SadP to Galα1–4Gal-containing proteins (Pk-BSA, pigeon ovomucoid) and to the control glycoproteins (hen egg albumin, invertase from baker's yeast, human milk lactoferrin, asialomucin from bovine sumandibular gland, fetal calf serum fetuin, and porcine thyroglobulin). B, concentration-dependent binding of histidine-tagged SadP fusion protein to glycoproteins on microwells (5-fold dilutions of proteins). BSA served as a control. C, binding of SadP fusion protein to glycolipids immobilized in microtiter wells. D, binding of SadP to pigeon ovomucoid studied under flow conditions in a surface plasmon resonance assay. The binding of SadP to pigeon ovomucoid-coated surface plasmon resonance chip was studied at the indicated concentrations of SadP. Error bars, S.E.

Probing of SadP Binding Specificity by Galα1–4Gal Disaccharide Derivatives

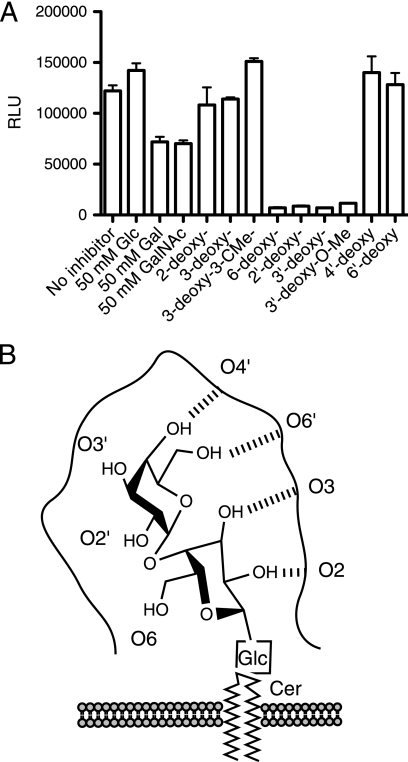

We have earlier thoroughly examined the roles of individual hydroxyl groups of the Galα1–4Gal disaccharide in the hemagglutination activity of the bacteria (24). Deoxy derivatives of the disaccharide Galα1–4Gal were therefore tested as inhibitors of SadP binding to pigeon ovomucoid. SadP binding to pigeon ovomucoid was inhibited with 0.5 mm 2′-deoxy and 3′-deoxy derivatives and 6-deoxy derivative of Galα1–4Gal, whereas the 2-, 3-, 4′-, and 6′-deoxy derivatives representing the key hydroxyl groups required for the interaction were not inhibiting (Fig. 6A; for numbering of the hydroxyls, see Fig. 6B). This is in accordance with the previous inhibition data obtained by a solid phase inhibition experiment using whole intact hemagglutination-positive S. suis strains (24) (supplemental Table S3).

FIGURE 6.

Identification of the hydroxyls involved in the binding of the SadP adhesin to Galα1–4Gal. A, microtiter wells were coated with 1 μg/ml pigeon ovomucoid, and inhibition studies were performed by incubating 5 μg/ml SadP adhesin in the presence of 50 mm d-glucose, d-galactose, or N-acetylgalactosamine or a 500 μm concentration of the O-deoxy derivatives of Galα1–4Gal as indicated. B, schematic diagram of the binding mechanism of S. suis SadP adhesin to Galα1–4Gal. Error bars, S.E.

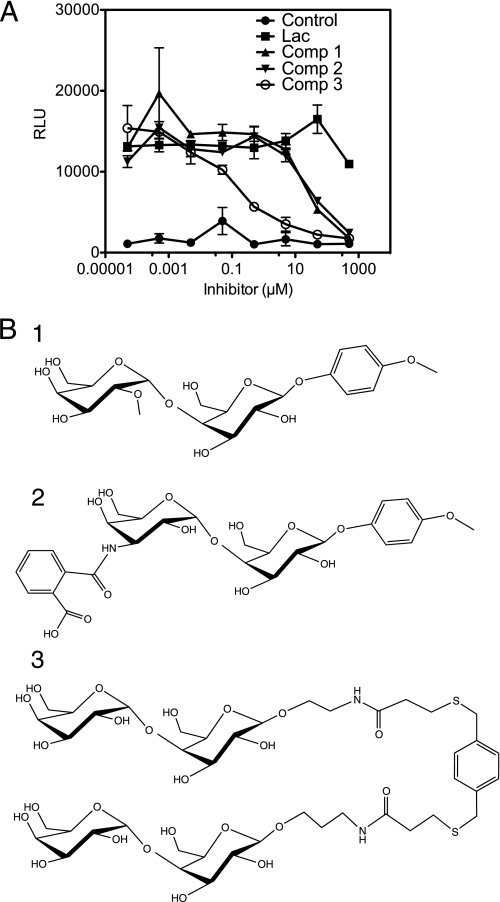

Previous studies have revealed that S. suis hemagglutinating strains have fine specificity for the recognition of terminal Galα1–4Gal disaccharide, although a subset of strains, including the S. suis D282 used in this study, can also tolerate internal Galα1–4Gal as in globotetraosyl ceramide (Fig. 5C) and can also tolerate other bulky chemical substituents in the HO-3′ position (24, 40). Representatives of these galabiose oligosaccharides were therefore chosen to analyze the fine specificity of SadP binding. Solid phase inhibition studies were performed with adhesin-coated fluorescent nanoparticles in microtiter plates, which proved to be a robust method in analyzing multiple samples (Fig. 7A). The results show that two galabiose derivatives, one with a methoxyphenyl group at the O2′ position (compound 1; Fig. 7B) and one with the amido derivative 2-carboxybenzamido at the C3′ position (compound 2), are strong inhibitors of SadP. These results indicate that specificity of SadP is of the subtype (PN) allowing substitution at these two sites. In addition, the strong inhibition of binding with the divalent Galα1–4Gal dendrimer (compound 3) at an IC50 of 100 nm is in accordance with previous observations with whole bacteria that the divalent galabiose inhibitor was a 300-fold stronger inhibitor of hemagglutination as compared with the monovalent derivative (22).

FIGURE 7.

Effect of receptor disaccharide valence on the binding of SadP adhesin. A, binding of europium-labeled nanoparticles coated with SadP fusion protein was tested in a solid phase inhibition assay. The binding was recorded using europium fluorescence (RLU) and using pigeon ovomucoid as a target. Lactose, Galβ1–4Glc, was used as a negative control. B, the inhibitors used were as follows: compound 1, Galα1–4Gal derivatized with methoxyphenyl group at the C1 position and with methoxymethylation at the O2′ position; compound 2, amide derivative of Galα1–4Gal with 2-carboxybenzamido at the C3′ position; compound 3, divalent Galα1–4Gal dendrimer (22, 44). Error bars, S.E.

Definition of the Galα1–4Gal-binding Site and Determination of Its Association and Dissociation Kinetics

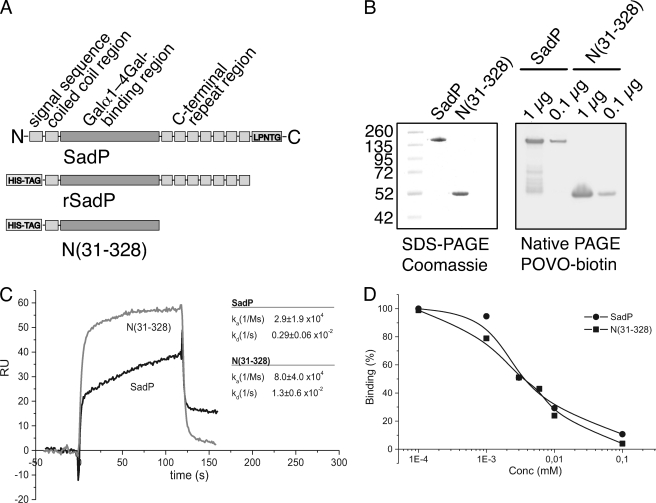

The 36.6-kDa N-terminal fragment N(31–328) of SadP excluding the C-terminal tandem repeat region (Fig. 8A) was cloned and expressed in E. coli. The size of the protein in SDS-PAGE appeared to correspond to a monomer. N(31–328) was separated in native PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. It was recognized by biotinylated pigeon ovomucoid in a ligand blotting assay (Fig. 8B) as strongly as the full-length SadP.

FIGURE 8.

Definition of the Galα1–4Gal-binding region of SadP and its binding kinetics. A, the N-terminal fragment of SadP, N(31–328), excluding the C-terminal tandem repeat region, was cloned and expressed in E. coli. B, SDS-PAGE of N(31–328). For ligand blotting, full-length SadP and N(31–328) were separated with native PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane and probed with biotinylated pigeon ovomucoid (1 and 0.1 μg). C, pigeon ovomucoid was coated on a Biacore sensor chip, the binding of SadP or N(31–328) to the coated surface was recorded, and the association and dissociation constants were calculated. For clarity, only binding curves of a 10 μg/ml concentration of the adhesins are shown. D, SadP or N(31–328) was mixed with synthetic galabiose inhibitor (Galα1–4Galβ1-OMe) at the concentrations indicated and allowed to adhere to ovomucoid-coated sensor chip. Binding is expressed as percentage of binding in the absence of inhibitor.

In a surface plasmon resonance assay, the N-terminal fragment N(31–328) bound to a pigeon ovomucoid-coated surface and showed somewhat different kinetics of binding from the whole SadP (Fig. 8C). The obtained binding curves did not fit to any preprogrammed binding models in the BIAevaluation program; therefore, the ka and kd values were calculated separately. Binding was measured at five different adhesin concentrations (5, 10, 20, 40, and 60 μg/ml). Both the association and dissociation phases of the N-terminal fragment were faster than those of the whole SadP molecule. The binding of both SadP and N(31–328) were inhibited by synthetic galabiose inhibitor (Fig. 8D).

DISCUSSION

S. suis is an important pig pathogen causing substantial economical losses and is also an emerging zoonotic pathogen with new variants causing streptococcal toxic shock syndrome in humans (9–11). Understanding the molecular mechanisms that are important for S. suis to adhere to host cells could provide a basis for design of novel antiadhesive drugs and vaccines. We have earlier characterized S. suis strains adhering specifically to Galα1–4Gal-containing glycoconjugates (23, 24). The adhesion activity mediates agglutination of sialidase-treated erythrocytes and binding to glycolipid GbO3 and participates in the binding of S. suis to pig pharyngeal epithelium (24). Strains that recognize NeuNAcα2–3Galβ1 terminal structures in glycoproteins have also been identified in S. suis, but they appear to be less common than the Galα1–4Gal-binding strains (41).

Comparison of the mechanisms of galabiose recognition by Gram-positive S. suis and Gram-negative uropathogenic E. coli P fimbrial PapG adhesins, by using receptor derivatives, suggests that the bacteria recognize their receptor from different sides of the disaccharide (24). The solved three-dimensional crystal structure of E. coli PapG has provided a view of the molecular mechanisms of the tropism of E. coli toward uroepithelium in the human kidney (42). The Galα1–4Gal-specific adhesion of S. suis represents an example where galabiose analogs or polyvalent dendrimers have been shown to be exceptionally efficient inhibitors at nanomolar concentrations (22, 43, 44); however, the identity and structure of the adhesin have remained elusive. In this study, we have identified the adhesin, which will allow study of the adhesin-oligosaccharide interaction in more detail.

In the current study, we set out to identify the Galα1–4Gal-binding adhesin of S. suis by the use of mass spectrometry of surface proteins that bind to a pigeon ovomucoid affinity matrix containing Galα1–4Gal oligosaccharides. This approach led to the identification of a previously functionally unknown S. suis LPNTG-anchored cell wall protein (SSU0253) as the S. suis Galα1–4Gal-binding adhesin, designated here as SadP. Insertional inactivation of the gene abolished SadP expression and Galα1–4Gal-dependent hemagglutination. Functional studies with recombinant protein showed that the SadP binds to its natural glycolipid receptor GbO3 (CD77). The fine specificity of the protein to Galα1–4Gal-containing oligosaccharides and their derivatives resembles in detail the activity of the whole bacteria (24).

This is the first report that shows that an LPXTG-anchored protein in S. suis recognizes carbohydrate receptors. Although a number of streptococcal and Gram-positive bacterial adhesins are known (45), there are only a few adhesins that have been reported to recognize carbohydrates. Examples of those are the sialic acid-binding streptococcal adhesins serine-rich repeat protein GpsA and Hsa (46–50). Another example of sialic acid-specific adhesion is the pneumococcal sialidase NanA, which is involved in pneumococcal biofilm formation and invasion into brain microvascular endothelial cells (51, 52). In addition, Gram-positive bacteria are known to express adhesins that bind glycosaminoglycans (53–57). S. suis SadP binding to Galα1–4Gal represents a unique Gram-positive cell surface protein recognizing glycolipids.

The primary structure of SadP consists of an N-terminal signal sequence for secreted proteins, C-terminal tandem repeats, and an LPXTG motif for anchorage of the protein to the cell wall. In our study, a mutation in SrtA abolished hemagglutination, thus supporting the identification of SadP as a cell wall protein. Earlier studies have shown that knock-out strains constructed to the sortase gene srtA in S. suis lack at least four LPXTG-anchored proteins in their cell walls and that proteins sorted by SrtA have a significant role in the adhesion of S. suis to porcine brain microvascular endothelial cells (58).

A common feature of LPXTG-anchored Gram-positive proteins is that they have repeated sequences in their C-terminal part. S. suis SadP contains seven glutamate- and proline-rich tandem repeats of a length of 57 amino acids, as identified with the Radar program (supplemental Fig. 2). Based on Blast comparisons, these appear to have low similarity to the repeats of two pneumococcal proteins PspC (E 0.019) and IgA-binding protein (e 0.021) and also to Streptococcus agalactiae IgA-binding C protein (e 3 × 10−12). The N-terminal part of the protein contains a coiled-coil structure, but the N terminus has no significant homology to any other known bacterial protein as illustrated in the ClustalW multiple alignment (supplemental Fig. 5). The cloned N-terminal fragment was shown to bind Galα1–4Gal. The sequence comparisons suggest that SadP is a unique protein with no significant orthologs in other Gram-positive or other bacterial species. It is of particular interest that there is no similarity to the P fimbrial adhesin PapG, which mediates binding of E. coli to uroepithelial glycolipids containing the Galα1–4Gal disaccharide.

The glycolipid receptor of SadP, trihexosylceramide (GbO3), is abundant in endothelial and some epithelial cells and has been identified as the receptor for E. coli verotoxin and P. aeruginosa lectin I (28, 59). Indirect evidence that brain capillary endothelial cells are rich in GbO3 receptors has been obtained with Galα1–4Gal-binding verotoxins that have been shown to target strongly to pig brain microvascular endothelial cells (60, 61). Considering the Galα1–4Gal specificity of S. suis strains able to cause meningitis and the presence of Galα1–4Gal oligosaccharides in microvascular endothelial cells, the SadP adhesin may be a potential target for antiadhesion drugs and vaccines. Indeed, SadP (SSU0253) has recently been shown to be a highly antigenic protein, to be expressed by most type 2 S. suis strains, and to induce protective antibodies in mice (62, 63).

The GbO3 glycolipid, also present in lipid rafts, has been implicated in various cellular functions, such as being a lipid associated with the metastasis of cancer cells (64–66). It has been shown that the carbohydrate-binding pentameric B-subunit of E. coli verotoxin causes apoptosis in susceptible endothelial cells, such as the Eahy.926 hybridoma cell line, upon binding to the GbO3 glycolipid receptor (64, 65), which makes the interaction of GbO3 with endogenous and exogenous ligands a potential target for therapies. The availability of the SadP with its distinct and well characterized Galα1–4Gal binding specificity could be a useful tool in studies aiming at these goals.

It is remarkable that two bacterial adhesins of different origin, S. suis SadP and E. coli PapG, target host tissues via the same Galα1–4Gal disaccharide. On one hand, this indicates that among the multitude of carbohydrate structures in the host, Galα1–4Gal has properties that make it advantageous for these microbes to use it as their target. On the other hand, recognition of GbO3 by biologically diverse microbes may represent an example of the evolutionarily convergent trait of pathogenic adaptation (67) toward recognition of a host receptor that is important for tissue tropism and could have a role in compromising the host defense mechanism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jukka Karhu for excellent technical assistance, Dr. Anne Rokka (Turku Center for Biotechnology, Proteomics) for LC-MS/MS analysis, and Oso Rissanen (Turku Center for Biotechnology, Microarray and Sequencing) for DNA sequencing. We thank Susann Teneberg (University of Gothenburg) for the donation of glycolipid sialosylparagloboside.

This study was supported by Finnish Academy Grant 114100, the Turku University Foundation, the Duodecim Society of Turunmaa and the Finnish Graduate School of Glycosciences.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1-S3, Figs. 1–5, and Files 1–3.

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- Pk-BSA

- Galα1–4Galβ1–4Glcβ1-O-CETE-BSA neoglycoprotein conjugate

- CETE

- 2(2-carboxyethylthio)-ethyl

- RLU

- relative light units.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gu H., Zhu H., Lu C. (2009) BMC Microbiol. 9, 201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Li W., Liu L., Qiu D., Chen H., Zhou R. (2010) Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 300, 482–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tan C., Liu M., Jin M., Liu J., Chen Y., Wu T., Fu T., Bei W., Chen H. (2008) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 278, 108–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wilson T. L., Jeffers J., Rapp-Gabrielson V. J., Martin S., Klein L. K., Lowery D. E., Fuller T. E. (2007) Vet. Microbiol. 122, 135–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Charland N., Harel J., Kobisch M., Lacasse S., Gottschalk M. (1998) Microbiology 144, 325–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smith H. E., Damman M., van der Velde J., Wagenaar F., Wisselink H. J., Stockhofe-Zurwieden N., Smits M. A. (1999) Infect. Immun. 67, 1750–1756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Greeff A., Buys H., Verhaar R., Dijkstra J., van Alphen L., Smith H. E. (2002) Infect. Immun. 70, 1319–1325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fittipaldi N., Sekizaki T., Takamatsu D., de la Cruz Domínguez-Punaro M., Harel J., Bui N. K., Vollmer W., Gottschalk M. (2008) Mol. Microbiol. 70, 1120–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Higgins R., Gottschalk M. (2005) in Diseases of Swine, 9th Ed. (Straw B. E., Zimmerman J. J., D'Allaire S., Tailor D. J. eds) pp. 769–776, Iowa State University Press, Ames, IA [Google Scholar]

- 10. Feng Y., Zhang H., Ma Y., Gao G. F. (2010) Trends Microbiol. 18, 124–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mai N. T., Hoa N. T., Nga T. V., Linh le D., Chau T. T., Sinh D. X., Phu N. H., Chuong L. V., Diep T. S., Campbell J., Nghia H. D., Minh T. N., Chau N. V., de Jong M. D., Chinh N. T., Hien T. T., Farrar J., Schultsz C. (2008) Clin. Infect. Dis. 46, 659–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yu H., Jing H., Chen Z., Zheng H., Zhu X., Wang H., Wang S., Liu L., Zu R., Luo L., Xiang N., Liu H., Liu X., Shu Y., Lee S. S., Chuang S. K., Wang Y., Xu J., Yang W. (2006) Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12, 914–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen C., Tang J., Dong W., Wang C., Feng Y., Wang J., Zheng F., Pan X., Liu D., Li M., Song Y., Zhu X., Sun H., Feng T., Guo Z., Ju A., Ge J., Dong Y., Sun W., Jiang Y., Wang J., Yan J., Yang H., Wang X., Gao G. F., Yang R., Wang J., Yu J. (2007) PLoS One 2, e315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ye C., Zheng H., Zhang J., Jing H., Wang L., Xiong Y., Wang W., Zhou Z., Sun Q., Luo X., Du H., Gottschalk M., Xu J. (2009) J. Infect. Dis. 199, 97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takamatsu D., Nishino H., Ishiji T., Ishii J., Osaki M., Fittipaldi N., Gottschalk M., Tharavichitkul P., Takai S., Sekizaki T. (2009) Vet. Microbiol. 138, 132–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pizarro-Cerdá J., Cossart P. (2006) Cell 124, 715–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sharon N., Ofek I. (2000) Glycoconj. J. 17, 659–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Strömberg N., Marklund B. I., Lund B., Ilver D., Hamers A., Gaastra W., Karlsson K. A., Normark S. (1990) EMBO J. 9, 2001–2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Karlsson K. A. (1986) Chem. Phys. Lipids 42, 153–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ofek I., Hasty D. L., Sharon N. (2003) FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 38, 181–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moschioni M., Emolo C., Biagini M., Maccari S., Pansegrau W., Donati C., Hilleringmann M., Ferlenghi I., Ruggiero P., Sinisi A., Pizza M., Norais N., Barocchi M. A., Masignani V. (2010) Infect. Immun. 78, 5033–5042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hansen H. C., Haataja S., Finne J., Magnusson G. (1997) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 6974 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haataja S., Tikkanen K., Liukkonen J., François-Gerard C., Finne J. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 4311–4317 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haataja S., Tikkanen K., Nilsson U., Magnusson G., Karlsson K. A., Finne J. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 27466–27472 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Strömberg N., Nyholm P. G., Pascher I., Normark S. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 9340–9344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lindberg A. A., Brown J. E., Strömberg N., Westling-Ryd M., Schultz J. E., Karlsson K. A. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 1779–1785 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lingwood C. A., Law H., Richardson S., Petric M., Brunton J. L., De Grandis S., Karmali M. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 8834–8839 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Blanchard B., Nurisso A., Hollville E., Tétaud C., Wiels J., Pokorná M., Wimmerová M., Varrot A., Imberty A. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 383, 837–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen B., Zhang A., Li R., Mu X., He H., Chen H., Jin M. (2010) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 307, 12–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pulliainen A. T., Haataja S., Kähkönen S., Finne J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7996–8005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. François-Gerard C., Gerday C., Beeley J. G. (1979) Biochem. J. 177, 679–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pulliainen A. T., Hytönen J., Haataja S., Finne J. (2008) J. Bacteriol. 190, 3225–3235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kurl D. N., Haataja S., Finne J. (1989) Infect. Immun. 57, 384–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Navarre W. W., Ton-That H., Faull K. F., Schneewind O. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 29135–29142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tikkanen K., Haataja S., François-Gerard C., Finne J. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 28874–28878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pulliainen A. T., Kauko A., Haataja S., Papageorgiou A. C., Finne J. (2005) Mol. Microbiol. 57, 1086–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Osaki M., Takamatsu D., Shimoji Y., Sekizaki T. (2002) J. Bacteriol. 184, 971–982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Berthelot-Hérault F., Cariolet R., Labbé A., Gottschalk M., Cardinal J. Y., Kobisch M. (2001) Can. J. Vet. Res. 65, 196–200 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Berthelot-Hérault F., Gottschalk M., Morvan H., Kobisch M. (2005) Can. J. Vet. Res. 69, 236–240 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Krivan H. C., Roberts D. D., Ginsburg V. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 6157–6161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liukkonen J., Haataja S., Tikkanen K., Kelm S., Finne J. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 21105–21111 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dodson K. W., Pinkner J. S., Rose T., Magnusson G., Hultgren S. J., Waksman G. (2001) Cell 105, 733–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Joosten J. A., Loimaranta V., Appeldoorn C. C., Haataja S., El Maate F. A., Liskamp R. M., Finne J., Pieters R. J. (2004) J. Med. Chem. 47, 6499–6508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ohlsson J., Larsson A., Haataja S., Alajääski J., Stenlund P., Pinkner J. S., Hultgren S. J., Finne J., Kihlberg J., Nilsson U. J. (2005) Org. Biomol. Chem. 3, 886–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nobbs A. H., Lamont R. J., Jenkinson H. F. (2009) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 73, 407–450, Table of Contents [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jakubovics N. S., Kerrigan S. W., Nobbs A. H., Strömberg N., van Dolleweerd C. J., Cox D. M., Kelly C. G., Jenkinson H. F. (2005) Infect. Immun. 73, 6629–6638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Loimaranta V., Jakubovics N. S., Hytönen J., Finne J., Jenkinson H. F., Strömberg N. (2005) Infect. Immun. 73, 2245–2252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Takamatsu D., Bensing B. A., Prakobphol A., Fisher S. J., Sullam P. M. (2006) Infect. Immun. 74, 1933–1940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Urano-Tashiro Y., Yajima A., Takashima E., Takahashi Y., Konishi K. (2008) Infect. Immun. 76, 4686–4691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yajima A., Urano-Tashiro Y., Shimazu K., Takashima E., Takahashi Y., Konishi K. (2008) Microbiol. Immunol. 52, 69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Parker D., Soong G., Planet P., Brower J., Ratner A. J., Prince A. (2009) Infect. Immun. 77, 3722–3730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Uchiyama S., Carlin A. F., Khosravi A., Weiman S., Banerjee A., Quach D., Hightower G., Mitchell T. J., Doran K. S., Nizet V. (2009) J. Exp. Med. 206, 1845–1852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Baron M. J., Bolduc G. R., Goldberg M. B., Aupérin T. C., Madoff L. C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 24714–24723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Frick I. M., Schmidtchen A., Sjöbring U. (2003) Eur. J. Biochem. 270, 2303–2311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Duensing T. D., Wing J. S., van Putten J. P. (1999) Infect. Immun. 67, 4463–4468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schmidt K. H., Ascencio F., Fransson L. A., Köhler W., Wadström T. (1993) Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 279, 472–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Winters B. D., Ramasubbu N., Stinson M. W. (1993) Infect. Immun. 61, 3259–3264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vanier G., Sekizaki T., Domínguez-Punaro M. C., Esgleas M., Osaki M., Takamatsu D., Segura M., Gottschalk M. (2008) Vet. Microbiol. 127, 417–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lingwood C. A., Binnington B., Manis A., Branch D. R. (2010) FEBS Lett. 584, 1879–1886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tyrrell G. J., Ramotar K., Toye B., Boyd B., Lingwood C. A., Brunton J. L. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 524–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Boyd B., Tyrrell G., Maloney M., Gyles C., Brunton J., Lingwood C. (1993) J. Exp. Med. 177, 1745–1753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mandanici F., Gómez-Gascón L., Garibaldi M., Olaya-Abril A., Luque I., Tarradas C., Mancuso G., Papasergi S., Bárcena J. A., Teti G., Beninati C., Rodríguez-Ortega M. J. (2010) J. Proteomics 73, 2365–2369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhang A., Xie C., Chen H., Jin M. (2008) Proteomics 8, 3506–3515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Schweppe C. H., Bielaszewska M., Pohlentz G., Friedrich A. W., Büntemeyer H., Schmidt M. A., Kim K. S., Peter-Katalini J., Karch H., Müthing J. (2008) Glycoconj. J. 25, 291–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Devenica D., Cikes Culic V., Vuica A., Markotic A. (2010) Med. Oncol., in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kovbasnjuk O., Mourtazina R., Baibakov B., Wang T., Elowsky C., Choti M. A., Kane A., Donowitz M. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 19087–19092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sikora S., Strongin A., Godzik A. (2005) Trends Microbiol. 73, 522–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Suzuki N., Khoo K. H., Chen H. C., Johnson J. R., Lee Y. C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 23221–23229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.