Background: Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) modulates cancer cell metabolism and survival.

Results: The novel compound OSU-53 directly activates AMPK, inhibits multiple metabolic and oncogenic pathways, and induces apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancer cells.

Conclusion: OSU-53 acts through a broad spectrum of antitumor activities downstream of AMPK activation.

Significance: OSU-53 is a potent small molecule AMPK activator with translational potential for breast cancer therapy.

Keywords: Akt PKB, AMP-activated Kinase (AMPK), Breast Cancer, Cancer Therapy, Lipogenesis, mTOR, Tumor Metabolism, IL-6, Stat3, Drug Discovery

Abstract

The antitumor activities of the novel adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activator, OSU-53, were assessed in in vitro and in vivo models of triple-negative breast cancer. OSU-53 directly stimulated recombinant AMPK kinase activity (EC50, 0.3 μm) and inhibited the viability and clonogenic growth of MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells with equal potency (IC50, 5 and 2 μm, respectively) despite lack of LKB1 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells. Nonmalignant MCF-10A cells, however, were unaffected. Beyond AMPK-mediated effects on mammalian target of rapamycin signaling and lipogenesis, OSU-53 also targeted multiple AMPK downstream pathways. Among these, the protein phosphatase 2A-dependent dephosphorylation of Akt is noteworthy because it circumvents the feedback activation of Akt that results from mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition. OSU-53 also modulated energy homeostasis by suppressing fatty acid biosynthesis and shifting the metabolism to oxidation by up-regulating the expression of key regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis, such as a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α and the transcription factor nuclear respiratory factor 1. Moreover, OSU-53 suppressed LPS-induced IL-6 production, thereby blocking subsequent Stat3 activation, and inhibited hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in association with the silencing of hypoxia-inducible factor 1a and the E-cadherin repressor Snail. In MDA-MB-231 tumor-bearing mice, daily oral administration of OSU-53 (50 and 100 mg/kg) suppressed tumor growth by 47–49% and modulated relevant intratumoral biomarkers of drug activity. However, OSU-53 also induced protective autophagy that attenuated its antiproliferative potency. Accordingly, cotreatment with the autophagy inhibitor chloroquine increased the in vivo tumor-suppressive activity of OSU-53. OSU-53 is a potent, orally bioavailable AMPK activator that acts through a broad spectrum of antitumor activities.

Introduction

The functional role of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK)2 in regulating energy homeostasis at both cellular and whole body levels is well recognized (1–4). In response to stimuli such as exercise, cellular stress, and adipokines, this cell energy-sensing enzyme induces a series of metabolic changes to balance energy consumption via multiple downstream signaling pathways controlling nutrient uptake and energy metabolism (5). More recently, accumulating evidence suggests a link between AMPK and cancer cell growth and survival in light of its ability to activate tuberous sclerosis complex 2, a tumor suppressor that negatively regulates protein synthesis by inhibiting mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (6). Thus, AMPK integrates growth factor signaling with cellular metabolism through the negative regulation of mTOR (5). From a therapeutic perspective, considering the feedback activation of Akt that occurs in response to rapamycin-based mTOR inhibitors, targeting AMPK activation represents a promising therapeutic strategy in cancer (7, 8). This premise is supported by recent preclinical findings that metformin and the AMP analog 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribose (AICAR), both pharmacological activators of AMPK, exhibit in vivo efficacy in blocking carcinogen-induced tumorigenesis and/or suppressing tumor growth in animal models (9, 10). Moreover, epidemiologic data of population-based cohort studies indicate a significantly reduced risk of breast cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes who are taking metformin on a long term basis compared with those taking thiourea, suggesting metformin as a potential candidate for breast cancer prevention (11–14). Despite this strong rationale, drawbacks associated with metformin as a chemopreventive agent include low in vitro efficacy with IC50 in the millimolar range (15), dependence on the tumor suppressor liver kinase B1 (LKB1) to mediate AMPK activation (16, 17), and untoward gastrointestinal side effects (2). Thus, there is an urgency to develop potent activators of this fuel-sensing enzyme with a distinct mode of action. Based on our finding that thiazolidinediones activated AMPK, in part, via a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)γ-independent mechanism, we used ciglitazone as a scaffold to develop a lead AMPK-activating agent, OSU-53 (18). OSU-53, a PPARγ-inactive derivative, stimulates AMPK kinase activity through direct activation with high potency, a mechanism distinct from that of metformin (16) or AICAR (19). For example, although AICAR requires intracellular phosphorylation to form an AMP analog to induce AMPK activation, the inhibition of complex 1 of the mitochondrial respiratory chain with the consequent increase in cytosolic AMP concentrations has been implicated in the mode of action of metformin (20). Moreover, the effects of both agents have also been linked to AMPK-independent mechanisms (21, 22)

In this study, we investigated the translational potential of OSU-53 as a therapeutic agent for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), a subtype of breast cancer characterized by a lack of estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human EGF receptor (HER)2 expression (23). Unlike estrogen receptor-positive and HER2-overexpressing breast cancers, the only available therapeutic options for TNBC patients are chemotherapies, which are associated with poorer overall prognosis (24). Thus, relevant target(s) and optimal treatments remain to be defined in TNBC.

We obtained evidence that OSU-53 at low micromolar concentrations effectively inhibited TNBC cell proliferation by concurrently blocking multiple oncogenic signaling pathways and energy metabolism through AMPK activation. Also noteworthy is the ability of OSU-53 to inhibit hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) by reducing hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α expression. Moreover, oral OSU-53 suppressed TNBC xenograft tumor growth in vivo. This in vivo efficacy, along with the broad spectrum of antitumor activities of OSU-53, provides a proof-of-concept that targeting AMPK activation with small molecule agents represents a therapeutically relevant strategy for TNBC.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

The TNBC cell lines, MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468, were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The nonmalignant MCF-10A breast epithelial cells were a kind gift from Dr. Robert Brueggemeier, Ohio State University. MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen), and MCF10A cells were maintained in DMEM/F-12 medium supplemented with 5% horse serum (Invitrogen), 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 100 ng/ml cholera toxin, 10 μg/ml insulin, and 20 ng/ml recombinant human EGF. All cells were cultured in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. For experiments requiring hypoxic conditions, cells were first cultured under normoxic conditions to obtain the desired level of confluence before experimentation under strictly controlled hypoxic conditions (0.3% O2) using the Proox model C21 O2/CO2 controller and C-Chamber (BioSperix, Lacona, NY).

Reagents and Antibodies

OSU-53 was synthesized according to a published procedure (18). For in vitro experiments, OSU-53 was dissolved in DMSO, diluted in culture medium, and added to cells at a final DMSO concentration of 0.1%. For in vivo studies, OSU-53 was prepared as a suspension in vehicle (0.5% methylcellulose, 0.1% Tween 80 in sterile water) for oral administration to tumor-bearing immunocompromised mice.

Mouse monoclonal antibodies against lysosome-associated membrane protein (LAMP)2 and β-actin were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and MP Biomedicals (Irvine, CA), respectively. Rabbit antibodies against Thr(P)172-AMPK, AMPK, Ser(P)2448-mTOR, mTOR, Thr(P)389-p70S6K, p70S6K, Ser(P)79-acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), ACC, fatty acid synthase (FASN), Myc tag, Ser(P)9-glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)3β, GSK3β, Ser(P)473-Akt, Thr(P)308-Akt, Akt, Tyr(P)705-Stat3, Stat3, Tyr(P)1007/1008-Jak2, Jak2, HIF-1α, E-cadherin, vimentin, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), and microtubule-associated light chain (LC)3 were obtained from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA); Ser(P)872-hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR), HMGCR, and PPARγ coactivator (PCG)-1α from Millipore (Billerica, MA); cyclin D1, Twist, and Slug from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; and Snail from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Alexa Fluor dye-conjugated phalloidin (Alexa Fluor 488) and secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488 and 555) were purchased from Invitrogen.

Cell Viability and Colony Formation Assays

Cell viability was determined by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays as reported previously (18). Cells were seeded at 3 × 103 cells/well 24 h prior to treatment. For colony formation assays, cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 103 cells per 6-cm dish. After 24 h, cells were exposed to different concentrations of OSU-53 for 10–12 days with changes of drug-containing medium every 3 days. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS and stained with a 0.5% crystal violet solution in 25% methanol. Colonies of more than 15 cells were counted.

Cell Cycle Analysis

Cells were plated in 6-cm plates (4 × 105 cells/well) and were exposed to OSU-53 at the indicated concentrations for 48 h. Cell cycle distribution was analyzed by propidium iodide staining, followed by flow cytometry (FACScan; BD Biosciences).

Radiometric in Vitro AMPK Kinase Assay

The kinase activity of the recombinant AMPK holoenzyme α1β1γ2 was assessed in an in vitro radiometric assay using the SAMS peptide (HMRSAMSGLHLVKRR) as substrate and [γ-32P]ATP as phosphate donor. Twenty ng of the recombinant AMPK (Cell Signaling, catalog no. 7381) was incubated with different concentrations of OSU-53 or AMP in 15 μl of AMPK kinase assay buffer (Cell Signaling, catalog no. 9802) at room temperature for 20 min. The reaction was initiated by addition of 5 μl of SAMS peptide (1.0 μg/μl) and 5 μl of [γ-32P]ATP solution (0.16 μCi/μl), and after incubation at 30 °C for 30 min, the reaction was terminated by addition of 10 μl of 1% phosphoric acid. The reaction mixtures were spotted onto P81 phosphocellulose paper, followed by washes in 75 mm phosphoric acid. The 32P-labeled peptides were measured by scintillation counting.

Transient Transfection

Cells were transfected with 3 μg of plasmid encoding the K45R kinase-dead dominant-negative AMPK (Addgene, Cambridge, MA) or empty vector by electroporation using the Amaxa Nucleofector system (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Treatments were initiated 48 h after transfection. Expression of dominant-negative AMPK was confirmed by immunoblotting of the Myc tag, phosphorylated AMPK, and downstream targets of AMPK.

RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from drug-treated cells with TRIzol (Invitrogen) and then reverse-transcribed to cDNA using the Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The sequences of the primers used in this study are listed as follows: FASN, forward 5′-TTCTACGGCTCCACGCTCTTCC-3′ and reverse 5′-AGGCGTAGTAGACCGTGCAG-3′; PGC-1α, forward 5′-CAAGCCAAACCAACAACTTTATCTCT-3′ and reverse 5′-CTGCCAATCAGAGGAGACATC-3′; nuclear respiratory factor (NRF)-1, forward 5′-CCACGTTACAGGGAGGTGAG-3′ and reverse 5′-TGTAGCTCCCTGCTGCATCT-3′; mitochondrial transcription factor A (mtTFA), forward 5′-TATCAAGATGCTTATAGGGC-3′ and reverse 5′-ACTCCTCAGCACCATATTTT-3′; IL-6 forward 5′-AGAAAGGAGACATGTAACAAGAGT-3′ and reverse 5′-GCGCAGAATGAGATGAGTTGT-3′; GAPDH, forward 5′-AGGGGTCTACATGGCAACTG-3′ and reverse 5′-CGACCACTTTGTCAAGCTCA-3′. The cycle numbers for the RT-PCR of each target gene were as follows: FASN, 30; PGC-1α, 31; NRF-1. 33; mtTFA, 33. IL-6, 32; GADPH, 26.

Immunoblotting

Cells were suspended in SDS sample buffer, sonicated, and boiled for 10 min. After brief centrifugation, equivalent amounts of proteins from the soluble fractions of cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotted as described previously (18).

MitoTracker Assay

Mitochondria mass was determined by MitoTracker Green FM staining (Invitrogen). Cells were plated in 6-well plates (2 × 105 cells/well), incubated with OSU-53 at the indicated concentrations for 48 h, washed with serum-free DMEM, and stained with 100 nm Mitotracker Green FM in serum-free DMEM versus dye-free medium for 30 min. Cells were washed three times with serum-free DMEM and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Protein Phosphatase (PP)2A Phosphatase Activity Assay

PP2A activity was measured using the PP2A DuoSet IC activity assay kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, MDA-MB-231 cells were exposed to OSU-53 at the indicated concentrations or DMSO vehicle in 5% FBS-supplemented medium for 48 h following a 30-min pretreatment with okadaic acid (100 nm) or DMSO vehicle. Cells were then lysed in a phosphate-free lysis buffer, and aliquots of cell lysates containing 100 μg of protein were loaded onto 96-well plates coated with a capture antibody specific for PP2A (R&D Systems) for immunocapture at 4 °C for 3 h. After washing twice, synthetic phosphopeptide substrates (200 μm) were added for the dephosphorylation reaction catalyzed by PP2A. The level of free phosphate was determined by a sensitive dye-binding assay using malachite green and molybdic acid according to the manufacturer's instructions followed by measurement of the absorbance at 620 nm.

Cell Migration Assay

Cell migration was assessed using FalconTM cell culture inserts (8.0 μm pore size) in a 24-well format (BD Biosciences) according to the vendor's instructions. MDA-MB-468 cells were cultured under hypoxic conditions (0.03% O2) for 4 days to induce EMT and then exposed to different concentrations of OSU-53 or DMSO vehicle for an additional 48 h under hypoxic conditions. The surviving cells were collected by trypsinization, counted, and reseeded onto the membranes of the upper chambers (3 × 104 cells/insert), which had been inserted into the wells of 24-well plates containing 10% FBS-supplemented medium. After 18 h, the cells were fixed with 100% methanol and stained with Giemsa. Unmigrated cells remaining in the upper chambers were removed by wiping the top of the insert membranes with a damp cotton swab leaving only those cells that had migrated to the underside of the membranes. The membranes were mounted on glass slides, and the numbers of cells in three randomly chosen high power fields were counted. Experiments were performed three times.

Immunofluorescence

Treated cells were washed with cold PBS, fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at 37 °C, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min at room temperature, and then blocked with 3% BSA in PBS overnight at 4 °C. After washing with PBS, the cells were incubated with primary antibody in PBS containing 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature and then with secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (for LC3) or 555 (for LAMP2) for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with DAPI contained in the Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Confocal images were obtained with an Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope (Olympus Corp., Japan) using the 40× oil immersion lens. To visualize actin cytoskeletal structure, treated cells were fixed, permeabilized, and blocked as described above and then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated phalloidin in the presence of 1% BSA for 30 min.

MDA-MB-231 Xenograft Tumor Model

Xenograft tumors were established in female NCr athymic nude mice (5–7 weeks of age; NCI, Frederick, MD) by subcutaneous injection of 1 × 106 MDA-MB-231 cells in a total volume of 0.1 ml of PBS containing 50% Matrigel (BD Biosciences). To assess the activity of OSU-53 as a single agent, mice with established tumors (46.8 ± 8.4 mm3) were randomized to three groups (n = 7) receiving single daily treatments of OSU-53 at 50 or 100 mg/kg or vehicle (0.5% methylcellulose, 0.1% Tween 80 in water) for 28 days by oral gavage. In a separate study to investigate the effect of combining OSU-53 with the autophagy inhibitor chloroquine (CQ), mice with established tumors (53.6 ± 11.6 mm3) were randomized to four groups (n = 7) receiving the following treatments once daily: (a) CQ alone (50 mg/kg) plus methylcellulose/Tween 80 vehicle; (b) OSU-53 alone (100 mg/kg) plus PBS vehicle; (c) CQ (50 mg/kg) plus OSU-53 (100 mg/kg), and (d) both vehicles. OSU-53 and its vehicle (methylcellulose/Tween 80) were administered by oral gavage, and CQ and the PBS vehicle were delivered by intraperitoneal injection at a volume of 10 μl/g body weight. Tumor volumes were calculated from weekly caliper measurements using a standard formula (volume = width2 × length × 0.52). Body weights were measured weekly. At terminal sacrifice, tumors were harvested, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until used for biomarker analysis as described in the text. All experimental procedures using live animals were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by Ohio State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Homology Modeling and Molecular Docking

The primary sequence of human AMPK was retrieved from NCBI (no. 94557301), and the crystal structure of the kinase domain (KD)-autoinhibitory domain (AID) of Schizosaccharomyces pombe AMPK (Protein Data Bank code 3H4J) was used as a template for the homology target of human AMPK α-subunit structure. Sequence similarity and alignment were analyzed by using Discovery Studio 2.1 (Accelrys Inc., San Diego). The construction of the three-dimensional model was carried out by means of homology modeling that was geometry-optimized with CHARMM forced field calculation and further refined by molecular dynamics simulations. The Profiles-3D and Ramachandran plot programs were used to check the validity of human AMPK α-subunit three-dimensional structure by measuring the compatibility of that structure with the sequence of the protein. The structure of OSU-53 was constructed by geometry optimization with CHARMM force field calculation. Docking of OSU-53 into the KD-AID cleft was carried out using the CHARMM-based molecular docking algorithm implemented in the Discovery Studio 2.1 program. Flexibility of OSU-53 was taken into account by including different orientations and its rotatable torsion angles in the docking procedure. Accordingly, 108 conformation structures were generated, among which representatives of 102 stable conformations were obtained for analysis of the OSU-53-docked human KD-AID structure. The remaining results were minimized, and the lowest energy docking result was used as a starting point for further molecular dynamics simulations.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data from in vitro experiments are presented as means ± S.D. Data from in vivo experiments are expressed as means ± S.E. Differences among group means were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance or unpaired Student's t test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago).

RESULTS

OSU-53, a Direct Activator of AMPK, Exhibits High Potency in Inhibiting Cell Proliferation in TNBC Cells Irrespective of the Functional Status of LKB1

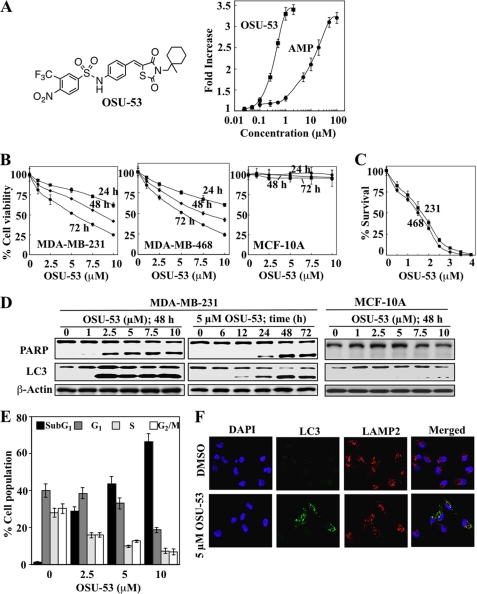

Radiometric kinase assays to assess the activity of the recombinant AMPK α1β1γ2 showed that OSU-53 (Fig. 1A, left panel) directly stimulated kinase activity with an EC50 of 0.3 μm vis à vis 8 μm for AMP (Fig. 1A, right panel). This finding indicates that the mode of action for OSU-53 in AMPK activation is distinctly different from those of metformin and AICAR.

FIGURE 1.

OSU-53 activates AMPK, inhibits breast cancer cell proliferation, and induces apoptosis and autophagy. A, left panel, structure of OSU-53. Right panel, effect of OSU-53 on the kinase activity of recombinant AMPK. Kinase activity was determined in the presence of OSU-53 or AMP at the indicated concentrations by measuring 32P-phosphorylation of the SAMS peptide substrate as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Points, mean; bars, S.D. (n = 3). B, effects of OSU-53 on the viability of MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells and MCF-10A breast epithelial cells. Cells were treated with OSU-53 at the indicated concentrations in 5% FBS-supplemented medium for 24, 48, and 72 h, and cell viability was assessed by MTT assays. Points, mean; bars, S.D. (n = 6). C, effects of OSU-53 on clonogenic survival of breast cancer cell lines (231, MDA-MB-231; 468, MDA-MB-468). Cells were treated with OSU-53 at the indicated concentrations for a total of 10–12 days, then fixed, stained, and counted as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Points, mean; bars, S.D. (n = 3). D, Western blot analysis of the concentration- and/or time-dependent effects of OSU-53 on PARP cleavage, a marker of apoptosis, and LC3-II conversion, a marker of autophagy, in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-10A cells. E, dose-dependent effect of OSU-53 on cell cycle distribution in MDA-MB-231 cells after 48 h of treatment. Data are presented as means ± S.D. of three independent experiments. F, effect of OSU-53 on autophagosome formation in MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were treated with 5 μm OSU-53 for 48 h and then stained for LC3 and LAMP2 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Colocalization of LC3 with LAMP2 was visualized by confocal microscopy. Green, LC3 (Alexa Fluor 488); red, LAMP2 (Alexa Fluor 555); blue, nuclei (DAPI). Magnification, ×40.

The results of MTT and clonogenic assays show a concentration- and time-dependent suppressive effect of OSU-53 on the viability (Fig. 1B) and survival (Fig. 1C) of LKB1-deficient MDA-MB-231 and LKB1-functional MDA-MB-468 cells with nearly equal potency (IC50, 5 and 2 μm for MTT and clonogenic assays, respectively). This antiproliferative potency is 3–4 orders-of magnitude higher than that reported for metformin (15) and AICAR (25) in breast cancer cells. Moreover, this LKB1-independent activity of OSU-53 contrasts with the reported insensitivity of MDA-MB-231 cells to metformin because of the lack of LKB1 expression in this cell line (26). Notably, OSU-53 had no apparent effect on the viability of nonmalignant MCF-10A cells over the same concentration range (Fig. 1B, right panel), indicating the selectivity of OSU-53 for malignant cells.

The suppressive effect of OSU-53 on cancer cell viability was, at least in part, attributable to apoptosis, as evidenced by PARP cleavage (Fig. 1D) and increases in the sub-G1 apoptotic population (Fig. 1E). In addition, it is well recognized that AMPK activation promotes autophagy in cancer cells via mTOR inhibition (27). The ability of OSU-53 to induce autophagy concomitantly with apoptosis was manifested by the parallel conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, immunocytochemical analysis revealed the accumulation of LC3-positive puncta following OSU-53 (5 μm) treatment, which colocalized with the lysosomal marker LAMP2, indicative of the formation of autophagosomal vacuoles (Fig. 1F). In contrast, MCF-10A cells were not susceptible to the effect of the drug on apoptosis and autophagy, as indicated by lack of PARP cleavage and LC3-II conversion (Fig. 1D).

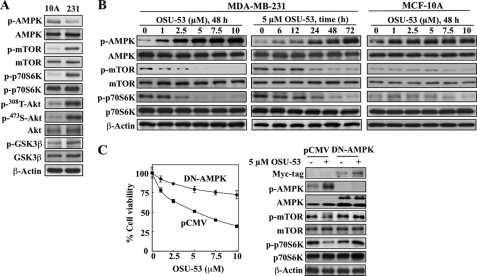

The basis of this discriminative effect of OSU-53 between tumor and nonmalignant cells may lie in differences in the activation status of signaling kinases associated with AMPK and Akt pathways. In principle, cancer cells evade genomic instability-induced apoptosis and acquire aggressive phenotype by up-regulating survival signaling pathways, the so-called oncogenic addiction (28), which is manifested by sharp differences in the activation status of mTOR, p70S6K, Akt, and GSK3β between MDA-MB-231 cells and MCF-10A cells (Fig. 2A). Relative to MDA-MB-231 cells, MCF-10A cells exhibited extremely low basal phosphorylation levels of these kinases, indicating that these signaling pathways are not up-regulated.

FIGURE 2.

Mechanistic underpinnings for the discriminative antiproliferative effect of OSU-53 between tumor and nonmalignant cells. A, Western blot analysis of the basal phosphorylation levels of AMPK, mTOR, p70S6K, Akt, and GSK3β in MCF-10A versus MDA-MB-231 cells. B, Western blot analysis of the concentration- and/or time-dependent effects of OSU-53 on the phosphorylation of AMPK and its downstream targets mTOR and p70S6K in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-10A cells. C, effects of the ectopic expression of dominant-negative (DN)-AMPK on cell viability (left panel) and mTOR-p70S6K signaling (right panel) in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with OSU-53 for 72 h as determined by MTT assays and Western blot analysis, respectively. Transfection with the empty pCMV vector served as control. Points, mean; bars, S.D. (n = 6).

Mechanistic Validation of the Role of AMPK Activation in OSU-53-mediated Antitumor Effects

It has been reported that the ability of metformin and AICAR to suppress cancer cell proliferation is attributable to the suppressive effect of AMPK activation on mTOR-p70S6K signaling (26) and lipogenesis (9). Thus, we assessed the effects of OSU-53 on biomarkers pertinent to these signaling pathways to verify its mode of antiproliferative action.

mTOR-p70S6K Signaling

Western blot analysis indicates that even at 1 μm, OSU-53 was able to induce concentration- and time-dependent increases in the phosphorylation levels of AMPK accompanied by parallel decreases in those of mTOR and its downstream target p70S6K in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 2B). In contrast, although OSU-53 facilitated dose-dependent activation of AMPK in MCF-10A cells, changes in the already low levels of phosphorylation of mTOR and p70S6K were imperceptible (Fig. 2B).

Considering the lack of LKB1 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells, the modulation of the AMPK-mTOR-p70S6K pathway by OSU-53 refutes the involvement of LKB1 as the upstream kinase mediating AMPK activation in response to OSU-53 treatment, which supports the notion that OSU-53 is a direct AMPK activator.

To validate the causal relationship between AMPK activation and the cytotoxicity of the drug, we examined the effect of the ectopic expression of dominant-negative AMPK, specifically a K45R kinase-dead α1-subunit (29), on OSU-53-mediated inhibition of cell viability. As shown, dominant-negative inhibition of AMPK, as evidenced by the abrogation of the effect of OSU-53 on biomarkers relevant to the AMPK-mTOR signaling pathway (Fig. 2C, right panel), protected cells from the antiproliferative activity of the drug (left panel).

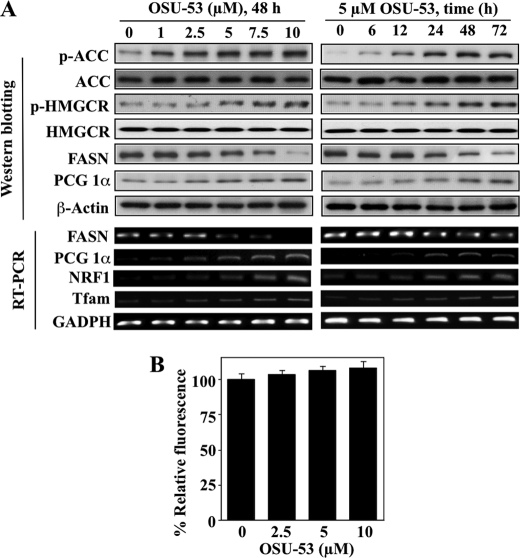

Lipogenesis and Mitochondrial Biogenesis

Reminiscent of the reported effects of metformin and AICAR on lipogenesis (2, 8, 9, 30), OSU-53 inactivated or repressed key enzymes involved in the de novo synthesis of fatty acids and cholesterol in MDA-MB-231 cells. As shown in Fig. 3A, OSU-53 treatment led to increased phosphorylation and consequent inactivation of two AMPK downstream targets, ACC and HMGCR, as well as reduced mRNA and protein expression levels of FASN in time- and concentration-dependent manners. Moreover, AMPK has been reported to play a key role in regulating mitochondrial biogenesis in muscle and neuronal cells (31), in part by up-regulating the expression of key regulators of mitochondrial functions, including PCG-1α, the transcription factor NRF1, and the NRF1 target mtTFA (32). The stimulatory effect of OSU-53 on the PGC-1α-NRF1 pathway was also noted in treated MDA-MB-231 cells as drug treatment led to concentration- and time-dependent increases in the protein and/or mRNA levels of these three key regulators (Fig. 3A). However, despite up-regulation of these mitochondrial biogenesis markers, MitoTracker Green FM staining indicates that OSU-53 did not cause significant increases in mitochondrial mass (Fig. 3B). This discrepancy might be due to the mitochondrial dysfunction reported in MDA-MB-231 cells (33). OSU-53 also interferes with a series of signaling pathways governing the survival and aggressive phenotype of TNBC cells through AMPK activation, which are delineated as follows.

FIGURE 3.

OSU-53 modulates biomarkers associated with lipogenesis and mitochondrial biogenesis. A, concentration- (left panel) and time- (right panel) dependent effects of OSU-53 on the phosphorylation and expression levels of markers of lipogenesis and mitochondrial biogenesis in MDA-MB-231 cells, including the phosphorylation levels of ACC and HMGCR, and protein levels of FASN and PGC-1a (upper panels, Western blotting), as well as the mRNA levels of FASN, PGC-1α, NRF1, and mtTFA (bottom panels, RT-PCR). B, MitoTracker Green FM staining analysis of the dose-dependent effect of OSU-53 on mitochondrial mass. Cells were treated with the indicated concentration of OSU-53 for 48 h and then stained with MitoTracker Green FM as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data are presented as means ± S.D. of three independent experiments.

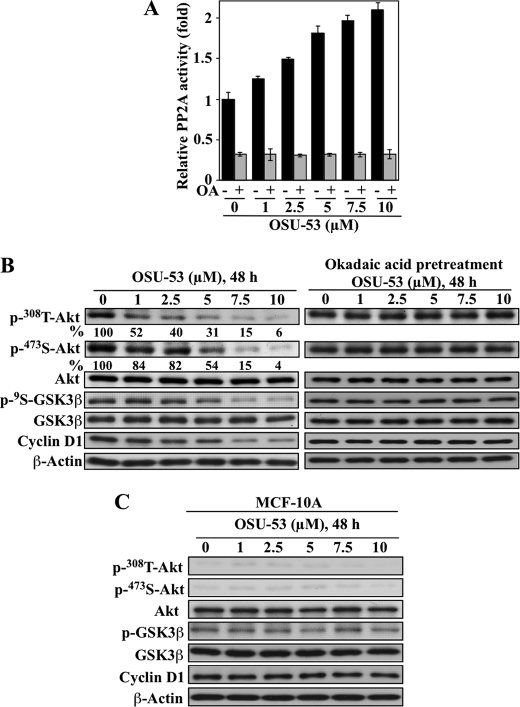

Akt Signaling

It has been reported previously that adiponectin-induced AMPK activation facilitated the dephosphorylation of Akt by stimulating PP2A activity (34). Pursuant to this finding, we demonstrated that OSU-53 significantly increased PP2A activity in MDA-MB-231 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A), which was abolished by pretreatment of cells with the PP2A inhibitor okadaic acid. This PP2A activation led to the dephosphorylation of Akt at Thr308 to a greater extent than that at Ser473 (Fig. 4B), which is characteristic of PP2A (35). This reduction in p-Akt levels was accompanied by parallel decreases in GSK3β phosphorylation and cyclin D1 expression, indicative of the blockade of the Akt signaling cascade. Moreover, okadaic acid abrogated the suppressive effect of OSU-53 on Akt signaling, supporting the functional role of PP2A. The ability of OSU-53 to inactivate Akt is noteworthy because it represents an advantage over current mTOR inhibitors, which cause a compensatory activation of Akt. Relative to MDA-MB-231 cells, MCF-10A cells exhibited very low phosphorylation levels of Akt and GSK3β (Fig. 2A) and were thus not susceptible to the suppressive effects of OSU-53 on Akt signaling, as manifested by a lack of appreciable changes in cyclin D1 expression, a marker of GSK3β activation status (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Role of PP2A in OSU-53-mediated activation of Akt signaling. A, effect of OSU-53 on PP2A activity. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of OSU-53 with and without a 30-min pretreatment with 100 nm okadaic acid. The phosphatase activity of immunoprecipitated PP2A was subsequently measured. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. B, Western blot analysis of the effects of OSU-53 alone (left panel) and after 30 min pretreatment with okadaic acid (100 nm; right panel) on phosphorylated Akt levels and downstream markers of Akt activity, including phospho-GSK3β and cyclin D1 protein expression in MDA-MB-231 cells. The values in percentage denote the relative intensities of protein bands of drug-treated samples to that of the respective DMSO vehicle-treated controls after being normalized to the respective internal reference β-actin. Each value represents the average of two independent experiments. C, Western blot analysis of the dose-dependent effect of OSU-53 on the phosphorylation/expression levels of Akt, GSK3β, and cyclin D1 in MCF-10A cells after 48 h of exposure.

IL-6 Signaling

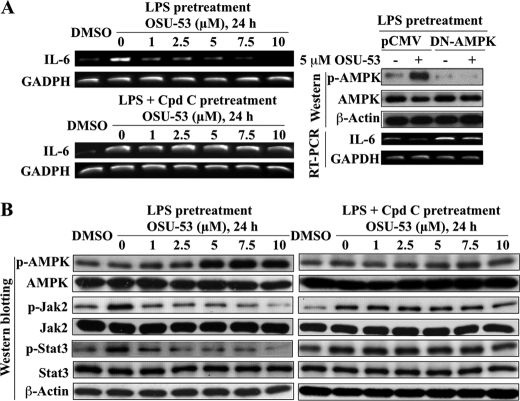

AMPK activation has been shown to suppress the expression of the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 (36–38), which plays a key role in promoting breast cancer progression via Jak2/Stat3 signaling (39). We obtained evidence that OSU-53 at low micromolar concentrations was effective in blunting LPS-mediated activation of the IL-6/Jak2/Stat3 pathway through AMPK activation. As shown, relative to DMSO control, LPS stimulated the mRNA expression of IL-6 (Fig. 5A, left, upper panel), accompanied by higher levels of Jak2 and Stat3 phosphorylation (Fig. 5B, left panel), which, however, could be blocked by OSU-53 in a concentration-dependent manner. This suppressive effect of OSU-53 on LPS-induced IL-6 production and the subsequent activation of Jak/Stat3 signaling was attributable to AMPK activation as it could be abolished by the pharmacological inhibition of AMPK by compound C (Fig. 5, A, left, lower panel, and B, right panel) and/or the ectopic expression of dominant-negative AMPK (Fig. 5A, right panel).

FIGURE 5.

OSU-53 inhibits IL-6 signaling through activation of AMPK. A, RT-PCR analysis of the concentration-dependent effect of OSU-53 alone (left upper panel) and after 6 h of pretreatment with 10 μm of the AMPK inhibitor compound C (left lower panel; Cpd C) on LPS-stimulated IL-6 mRNA expression in MDA-MB-231 cells in 5% FBS-containing medium. Right panel, ectopic expression of dominant-negative (DN)-AMPK protects MDA-MB-231 cells against OSU-53-mediated suppression of LPS-stimulated IL-6 mRNA levels. B, Western blot analysis of the concentration-dependent effect of OSU-53 alone (left panel) and after 6 h of pretreatment with 10 μm compound C (right panel) on the phosphorylation levels of AMPK and of downstream markers of IL-6 signaling, including Jak2 and Stat3, in LPS-pretreated MDA-MB-231 cells in 5% FBS-containing medium.

Hypoxia-induced EMT

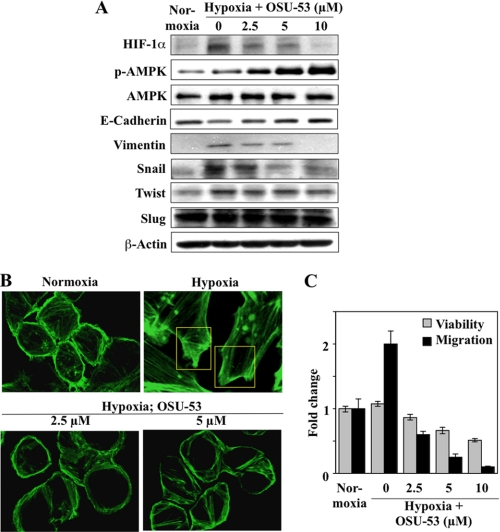

Substantial evidence indicates that EMT, as characterized by reduced expression of the epithelial cell adhesion marker E-cadherin and aberrant induction of the mesenchymal marker vimentin, underlies enhanced metastasis and unfavorable clinical outcome in breast cancer (40). EMT is triggered by many types of stimuli in the tumor microenvironment, including growth factors, inflammatory cytokines, cell-cell interactions, and hypoxia (41, 42). In this study, we assessed the effect of OSU-53 on hypoxia-induced EMT, in which HIF-1α plays a crucial role (43). We rationalized that OSU-53 could inhibit hypoxia-induced HIF-1α expression through two distinct AMPK-dependent mechanisms as follows: inhibition of mTOR-mediated HIF-1α translation (44) and induction of GSK3β-stimulated HIF-1α degradation (45). As MDA-MB-231 cells lack E-cadherin expression (46), we examined the drug effect in MDA-MB-468 cells. As expected, relative to the normoxic control, hypoxia stimulated HIF-1α protein expression, which was accompanied by changes in EMT markers, including reduced E-cadherin expression and increased vimentin expression (Fig. 6A). In support of our premise, these hypoxia-induced changes to HIF-1α and both EMT markers were abrogated by OSU-53 in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6A). The results also suggest that this inhibition of EMT might be attributable to the suppressed expression of Snail and, to a much lesser extent, Twist, both of which are known repressors of E-cadherin (47, 48) under HIF-1α regulation (49).

FIGURE 6.

OSU-53 inhibits hypoxia-induced EMT and cell migratory capacity in breast cancer cells. A, Western blot analysis of concentration-dependent effects of OSU-53 on hypoxia-induced changes to the expression of HIF-1α, the epithelial marker E-cadherin, and the mesenchymal markers vimentin, Snail, Twist, and Slug in MDA-MB-468 cells. Cells were cultured under hypoxic conditions (0.03% O2) for 4 days followed by 48 h of treatment with OSU-53 under continued hypoxia. B, effect of OSU-53 on hypoxia-induced actin cytoskeletal rearrangement and lamellipodia formation in MDA-MB-468 cells. Hypoxic cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of OSU-53 followed by staining for F-actin with fluorescent dye-labeled phalloidin. Boxes indicate stress fiber assembly and lamellipodial protrusions. OSU-53 inhibited these hypoxia-induced structural changes (bottom panels). Magnification, ×40. C, concentration-dependent suppressive effect of OSU-53 on the viability and migration of MDA-MB-468 cells under hypoxia. Cells were treated as described above in A and then harvested for assessment of migration as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The data are presented as means ± S.D. of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Furthermore, OSU-53 was able to suppress processes characteristic of the EMT-associated aggressive phenotype, such as hypoxia-stimulated actin cytoskeletal rearrangement and cell migration, in MDA-MB-468 cells. Relative to normoxia, hypoxia stimulated stress fiber assembly at the cell edge, as manifested by filopodial and lamellipodial protrusions (Fig. 6B, upper panels). These hypoxia-induced changes in F-actin structure, however, could be blocked by OSU-53 at 2.5 and 5 μm (Fig. 6B, lower panels). As these cytoskeletal rearrangements play a central role to cell migration, we assessed the effect of OSU-53 on MDA-MB-468 cell migration in the Boyden chamber system. As shown, hypoxia increased the migration of MDA-MB-468 cells by 2-fold after 48 h of treatment, which was blocked by OSU-53 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6C). As the extent of OSU-53-mediated inhibition of cell migration was substantially greater than that of cell viability, this inhibition was not solely attributable to increased cell death.

Suppressive Effect of OSU-53 on MDA-MB-231 Xenograft Tumor Growth

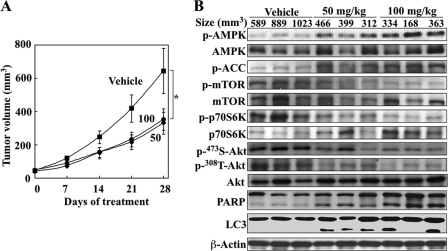

The in vivo antitumor efficacy of OSU-53 was evaluated in ectopic MDA-MB-231 tumor xenograft models. Athymic nude mice bearing established subcutaneous MDA-MB-231 tumors were treated orally with OSU-53 once daily at 50 or 100 mg/kg versus vehicle control (n = 7 for each group). OSU-53 at both doses was well tolerated as the mice showed no overt signs of toxicity or loss of body weight (data not shown). Although treatment with oral OSU-53 at either dose resulted in significant suppression of tumor growth relative to the vehicle control (p < 0.05) after 28 days of treatment, no dose dependence in the tumor-suppressive response was noted (49 and 48% suppression for 50 and 100 mg/kg, respectively; Fig. 7A). However, examination of intratumoral markers associated with drug activity showed a higher degree of AMPK phosphorylation and parallel decreases in the phosphorylation levels of mTOR, p70S6K, and Akt in the 100 mg/kg group than in the 50 mg/kg group (Fig. 7B), suggesting a dose-related delivery of drug to the tumor. Also noted was a greater extent of apoptosis and autophagy, as indicated by increased PARP cleavage and LC3-II conversion, in the higher dose group.

FIGURE 7.

OSU-53 inhibits breast tumor growth in vivo. A, effect of OSU-53 on MDA-MB-231 xenograft tumor growth in athymic nude mice. Mice with established subcutaneous MDA-MB-231 xenograft tumors were treated orally once daily with OSU-53 at 50 and 100 mg/kg or vehicle for 28 days, and tumor growth was monitored as described under the “Experimental Procedures.” Points, mean; bars, S.E. (n = 7). *, p < 0.05. B, Western blot analysis of intratumoral biomarkers of drug activity in three representative MDA-MB-231 tumors from each group of mice treated for 28 days as described above in A.

CQ Enhances Antiproliferative Activity of OSU-53

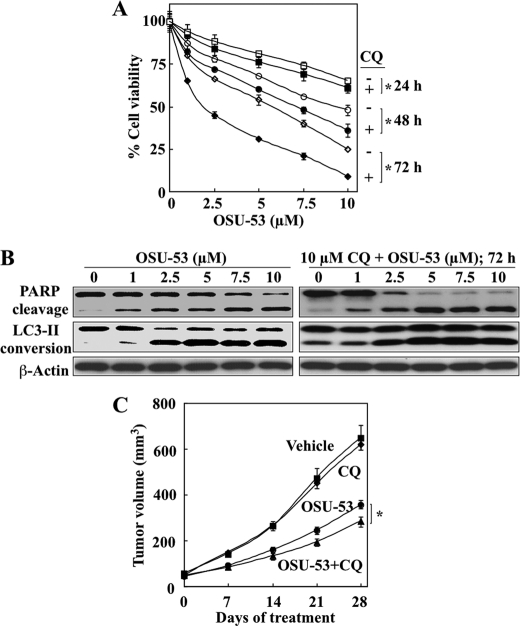

Although autophagy can mediate either protective or destructive cellular response to metabolic stress or therapeutic agents (50), evidence indicates that autophagy acts as a survival signal in response to inhibitors of the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling axis (51). In this context, we examined the effect of CQ, a lysosomotropic inhibitor of autophagy, on antiproliferative activity in vitro of the OSU-53. As shown, CQ at 10 μm significantly increased (*, p < 0.05) the suppressive effect of OSU-53 on the viability of MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 8A). Western blot analysis indicates that this increase was attributable to a higher extent of drug-induced apoptosis as a result of autophagy inhibition (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

OSU-53 induces both apoptosis and protective autophagy in breast cancer cells. A, effect of autophagy inhibition on the antiproliferative activity of OSU-53 in MDA-MB-231 cells. Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay after treatment with OSU-53 alone or in combination with 10 μm CQ for 24, 48, and 72 h. B, Western blot analysis of the dose-dependent effects of OSU-53 alone or in combination with 10 μm CQ on PARP cleavage and LC3-II conversion. C, effect of cotreatment with OSU-53 and the autophagy inhibitor CQ on MDA-MB-231 xenograft tumor growth. Mice with established subcutaneous MDA-MB-231 xenograft tumors were treated once daily with OSU-53 (100 mg/kg; oral gavage) or CQ (50 mg/kg; intraperitoneal) as single agents or in combination for 28 days. Points, mean; bars, S.E. (n = 7). *, p < 0.05.

This drug combination was also tested in vivo. As shown, CQ (50 mg/kg daily, intraperitoneal injection) was able to enhance the suppressive effect of daily oral OSU-53 at 100 mg/kg on MDA-MB-231 xenograft tumor growth (60% suppression for the combination versus 47% for OSU-53 alone), although CQ alone exhibited no appreciable tumor inhibitory activity (Fig. 8C; n = 7 in each group).

Mechanism by Which OSU-53 Activates AMPK

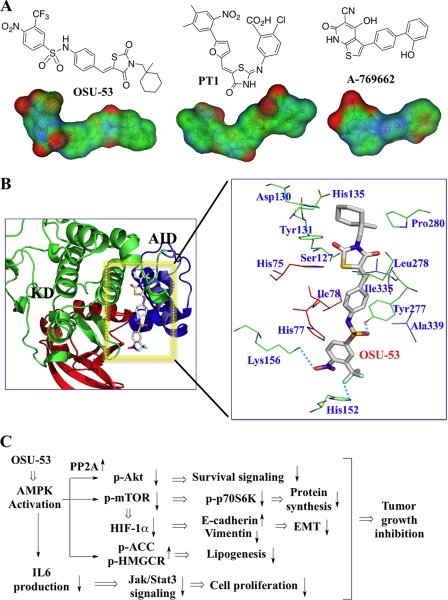

Our data indicate that OSU-53 is a direct activator of AMPK. In the literature, two other direct, small molecule AMPK activators have been reported, PT1 (52) and A-769662 (53), each of which exhibit a distinct mode of activation. Evidence suggests that PT1 antagonizes AMPK autoinhibition by binding to the α-subunit near the autoinhibitory domain (AID) (52) and that A-769662 stabilizes the active conformation of AMPK through allosteric binding to the γ-subunit (53). As the electrostatic potential map of OSU-53 exhibited a high degree of similarity to that of PT1 (Fig. 9A), we conducted molecular simulation by docking OSU-53 into the putative binding site formed between the KD and the AID of the α-subunit through homology modeling (Fig. 9B). As shown, OSU-53 bound to the AID domain through electrostatic interactions with His152, Lys156, and Tyr277 in a manner reminiscent of that of PT1. Mutational analysis to confirm this mode of ligand recognition is currently under way.

FIGURE 9.

Mechanism of AMPK activation by OSU-53. A, structures and surface electrostatic potentials of OSU-53 versus PT-1 and A-769662. The electron densities of individual areas are colored in red and blue to denote positive and negative electrostatic potentials, respectively, and changes in electrostatic potential from positive to negative are seen in transition from red to blue. B, schematic representation of the homology model of the human AMPK α-subunit (KD-AID) and speculative binding mode of docked OSU-53. The N- and C-lobes of the kinase domain (KD) are colored in red and green, respectively, the AID is in blue, and OSU-53 is shown as a stick structure with carbon atoms in gray, nitrogen in blue, sulfur in orange, chloride in light blue, and oxygen in red. The enlarged view of residues within 5 Å surrounding the docked OSU-53 shows where the potential hydrogen bonds exist (dotted lines). C, summary of the pathways by which OSU-53 inhibits tumor cell growth. OSU-53 acts as an AMPK activator, resulting in hallmark cellular responses, including the following: (a) PP2A induction leading to Akt dephosphorylation and consequent suppression of Akt-mediated survival signaling; (b) inhibition of mTOR signaling resulting in reduced protein synthesis and cell growth via the conventional mTOR-p70S6K pathway, and in the down-regulation of HIF-1α expression which suppresses hypoxia-induced EMT; (c) activation of ACC and HMGCR which inhibits lipogenesis, and (d) inhibition of IL-6 production resulting in reduced Jak/Stat3 signaling and consequent inhibition of cell proliferation.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we obtained evidence of the translational potential of OSU-53, a novel thiazolidinedione-derived AMPK activator, as a therapeutic agent for TNBC. OSU-53 exhibits 3 orders of magnitude higher antiproliferative potency than metformin (IC50, low micromolar versus millimolar) and, more importantly, directly activates AMPK (EC50, 0.3 μm) independent of its upstream kinase LKB1. This finding may have important therapeutic implications as LKB1 expression is often lost or down-regulated in breast tumors (54). Moreover, considering the pivotal role of LKB1 in mediating metformin-induced AMPK activation (17), LKB1-deficient breast tumors may be resistant to the chemopreventive and therapeutic effects of metformin (55), which represents a potential therapeutic advantage of OSU-53.

Our findings also show that OSU-53 is a potent antitumor agent that exhibits in vitro and in vivo efficacy in suppressing TNBC cell proliferation via diverse AMPK-dependent mechanisms. In addition to the AMPK-induced down-regulation of mTOR signaling and lipogenesis, which have been shown to underlie the antiproliferative activities of metformin (26) and AICAR (9), respectively, OSU-53 also modulates a series of pathways downstream of the AMPK cascade that govern survival, mitochondrial biogenesis, cytokine production, and EMT, as manifested by effects on the phosphorylation/expression levels of Akt, PCG-1α, IL-6, and HIF-1α (Fig. 9C).

The suppressive effect of OSU-53 on Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 4) is particularly noteworthy, because it circumvents the feedback activation of Akt that results from mTOR inhibition, a drawback to the use of early generation mTOR inhibitors. The ability of OSU-53 to concurrently block signaling through both kinases, reminiscent of that of the second generation mTOR inhibitors and dual PI3K-mTOR inhibitors (56), provides therapeutic advantages over rapamycin. Moreover, OSU-53-facilitated Akt dephosphorylation in MDA-MB-231 cells was mediated through a PP2A-dependent mechanism, which is consistent with that described for adiponectin-induced AMPK activation in the same cell line (34). However, this result contrasts with recent reports that metformin facilitated Ser473 Akt dephosphorylation in MCF-7 cells via an insulin receptor substrate 1-dependent pathway (15) and that AICAR stimulated Akt phosphorylation through insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor-dependent and -independent mechanisms (57). This discrepancy might reflect the differences in the modes of action among these AMPK activators, which warrants investigation.

The effects of OSU-53 on energy homeostasis in TNBC cells, which parallel those reported for metformin and AICAR in skeletal muscle and neuronal cells (32, 58, 59), were characterized by the blocked activation or expression of key enzymes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis (ACC, HMGCR, and FASN) and enhanced expression of regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis (PCG-1α, NRF1, and mtTFA) (Fig. 3A). Jointly, these effects on energy homeostasis can contribute to the antiproliferative activity of OSU-53 by inhibiting fatty acid synthesis and shifting cellular metabolism toward oxidation. Such changes in lipid metabolism have been shown experimentally, by use of the fatty-acid synthase inhibitor C75, to induce apoptotic death in breast cancer cells (60).

The ability of OSU-53 to suppress IL-6 production is clinically relevant in light of the major role of this cytokine in driving Stat3 activation in breast cancer (61). Stat3 represents an important therapeutic target in breast cancer because constitutively activated Stat3, which occurs in over 50% of primary breast tumors and is associated with a poor prognosis, endows tumor cells with chemoresistance and angiogenic potential (62). Moreover, the silencing of expression of HIF-1α and the E-cadherin repressor Snail may underlie the suppressive effect of OSU-53 on hypoxia-induced EMT and migratory activity in TNBC cells (Fig. 6) suggesting the ability to repress the aggressive phenotype associated with EMT.

Despite this broad spectrum of antitumor activities, nonmalignant MCF-10A mammary epithelial cells were unaffected by OSU-53, in part, due to the low basal activation levels of Akt and mTOR (Fig. 2). This low cytotoxicity is consistent with the lack of overt toxicity in tumor-bearing athymic nude mice after treatment with tumor-suppressive doses of up to 100 mg/kg of OSU-53 for 28 days (Fig. 7). Nonetheless, consistent with mTOR inhibition and reminiscent of the reported effects of many other therapeutic agents, OSU-53 induced a protective autophagy that attenuated its antiproliferative potency. In this context, cotreatment with the autophagy inhibitor CQ increased the in vitro antiproliferative activity and the in vivo tumor-suppressive effects of OSU-53, suggesting a possible strategy to enhance positive clinical responses to agents such as OSU-53.

In conclusion, these results show that OSU-53 is a novel, orally bioavailable AMPK activator with a distinct mode of action that inhibits TNBC by modulating multiple signaling pathways associated with cancer cell survival, metabolism, and progression. Evaluations of the activity of OSU-53 in other preclinical models of cancer, in support of its clinical translation, are underway.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01CA112250 and R21CA158807 (USPHS) from NCI (to C. S. C.).

- AMPK

- adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

- mTOR

- mammalian target of rapamycin

- AICAR

- 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribose

- PPARγ

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ

- TNBC

- triple-negative breast cancer

- EMT

- epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- ACC

- acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- FASN

- fatty-acid synthase

- PARP

- poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- LC3

- microtubule-associated light chain 3

- HMGCR

- hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- mtTFA

- mitochondrial transcription factor A

- CQ

- chloroquine

- KD

- kinase domain

- AID

- autoinhibitory domain.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hardie D. G. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 774–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hardie D. G. (2007) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 47, 185–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hardie D. G., Sakamoto K. (2006) Physiology 21, 48–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kahn B. B., Alquier T., Carling D., Hardie D. G. (2005) Cell Metab. 1, 15–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shackelford D. B., Shaw R. J. (2009) Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 563–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Inoki K., Zhu T., Guan K. L. (2003) Cell 115, 577–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hadad S. M., Fleming S., Thompson A. M. (2008) Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 67, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zadra G., Priolo C., Patnaik A., Loda M. (2010) Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 3322–3328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guo D., Hildebrandt I. J., Prins R. M., Soto H., Mazzotta M. M., Dang J., Czernin J., Shyy J. Y., Watson A. D., Phelps M., Radu C. G., Cloughesy T. F., Mischel P. S. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12932–12937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Memmott R. M., Mercado J. R., Maier C. R., Kawabata S., Fox S. D., Dennis P. A. (2010) Cancer Prev. Res. 3, 1066–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bodmer M., Meier C., Krähenbühl S., Jick S. S., Meier C. R. (2010) Diabetes Care 33, 1304–1308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Evans J. M., Donnelly L. A., Emslie-Smith A. M., Alessi D. R., Morris A. D. (2005) BMJ 330, 1304–1305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goodwin P. J., Ligibel J. A., Stambolic V. (2009) J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 3271–3273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jiralerspong S., Palla S. L., Giordano S. H., Meric-Bernstam F., Liedtke C., Barnett C. M., Hsu L., Hung M. C., Hortobagyi G. N., Gonzalez-Angulo A. M. (2009) J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 3297–3302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zakikhani M., Blouin M. J., Piura E., Pollak M. N. (2010) Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 123, 271–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fryer L. G., Parbu-Patel A., Carling D. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 25226–25232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xie Z., Dong Y., Scholz R., Neumann D., Zou M. H. (2008) Circulation 117, 952–962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guh J. H., Chang W. L., Yang J., Lee S. L., Wei S., Wang D., Kulp S. K., Chen C. S. (2010) J. Med. Chem. 53, 2552–2561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 19. Sun Y., Connors K. E., Yang D. Q. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 306, 239–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang L., He H., Balschi J. A. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 293, H457–H466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zang Y., Yu L. F., Pang T., Fang L. P., Feng X., Wen T. Q., Nan F. J., Feng L. Y., Li J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 6201–6208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Foretz M., Hébrard S., Leclerc J., Zarrinpashneh E., Soty M., Mithieux G., Sakamoto K., Andreelli F., Viollet B. (2010) J. Clin. Invest. 120, 2355–2369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reis-Filho J. S., Tutt A. N. (2008) Histopathology 52, 108–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carey L. A., Dees E. C., Sawyer L., Gatti L., Moore D. T., Collichio F., Ollila D. W., Sartor C. I., Graham M. L., Perou C. M. (2007) Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 2329–2334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kuznetsov J. N., Leclerc G. J., Leclerc G. M., Barredo J. C. (2011) Mol. Cancer Ther. 10, 437–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dowling R. J., Zakikhani M., Fantus I. G., Pollak M., Sonenberg N. (2007) Cancer Res. 67, 10804–10812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Meijer A. J., Codogno P. (2007) Autophagy 3, 238–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Weinstein I. B., Joe A. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 3077–3080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dyck J. R., Gao G., Widmer J., Stapleton D., Fernandez C. S., Kemp B. E., Witters L. A. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 17798–17803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhou G., Myers R., Li Y., Chen Y., Shen X., Fenyk-Melody J., Wu M., Ventre J., Doebber T., Fujii N., Musi N., Hirshman M. F., Goodyear L. J., Moller D. E. (2001) J. Clin. Invest. 108, 1167–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jornayvaz F. R., Shulman G. I. (2010) Essays Biochem. 47, 69–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yu L., Yang S. J. (2010) Neuroscience 169, 23–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ma Y., Bai R. K., Trieu R., Wong L. J. (2010) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1797, 29–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim K. Y., Baek A., Hwang J. E., Choi Y. A., Jeong J., Lee M. S., Cho D. H., Lim J. S., Kim K. I., Yang Y. (2009) Cancer Res. 69, 4018–4026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bayascas J. R., Alessi D. R. (2005) Mol. Cell 18, 143–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lihn A. S., Pedersen S. B., Lund S., Richelsen B. (2008) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 292, 36–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sag D., Carling D., Stout R. D., Suttles J. (2008) J. Immunol. 181, 8633–8641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nerstedt A., Johansson A., Andersson C. X., Cansby E., Smith U., Mahlapuu M. (2010) Diabetologia 53, 2406–2416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bromberg J., Wang T. C. (2009) Cancer Cell 15, 79–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sullivan N. J., Sasser A. K., Axel A. E., Vesuna F., Raman V., Ramirez N., Oberyszyn T. M., Hall B. M. (2009) Oncogene 28, 2940–2947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tse J. C., Kalluri R. (2007) J. Cell. Biochem. 101, 816–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kalluri R., Weinberg R. A. (2009) J. Clin. Invest. 119, 1420–1428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yang M. H., Wu M. Z., Chiou S. H., Chen P. M., Chang S. Y., Liu C. J., Teng S. C., Wu K. J. (2008) Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 295–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bernardi R., Guernah I., Jin D., Grisendi S., Alimonti A., Teruya-Feldstein J., Cordon-Cardo C., Simon M. C., Rafii S., Pandolfi P. P. (2006) Nature 442, 779–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Flügel D., Görlach A., Michiels C., Kietzmann T. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 3253–3265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mbalaviele G., Dunstan C. R., Sasaki A., Williams P. J., Mundy G. R., Yoneda T. (1996) Cancer Res. 56, 4063–4070 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Batlle E., Sancho E., Francí C., Domínguez D., Monfar M., Baulida J., García De Herreros A. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 84–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vesuna F., van Diest P., Chen J. H., Raman V. (2008) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 367, 235–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Foubert E., De Craene B., Berx G. (2010) Breast Cancer Res. 12, 206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Codogno P., Meijer A. J. (2005) Cell Death Differ. 12, Suppl. 2, 1509–1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fan Q. W., Cheng C., Hackett C., Feldman M., Houseman B. T., Nicolaides T., Haas-Kogan D., James C. D., Oakes S. A., Debnath J., Shokat K. M., Weiss W. A. (2010) Sci. Signal. 3, ra81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pang T., Zhang Z. S., Gu M., Qiu B. Y., Yu L. F., Cao P. R., Shao W., Su M. B., Li J. Y., Nan F. J., Li J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 16051–16060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sanders M. J., Ali Z. S., Hegarty B. D., Heath R., Snowden M. A., Carling D. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 32539–32548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shen Z., Wen X. F., Lan F., Shen Z. Z., Shao Z. M. (2002) Clin. Cancer Res. 8, 2085–2090 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Memmott R. M., Dennis P. A. (2009) J. Clin. Oncol. 27, e226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vilar E., Perez-Garcia J., Tabernero J. (2011) Mol. Cancer Ther. 10, 395–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Leclerc G. M., Leclerc G. J., Fu G., Barredo J. C. (2010) J. Mol. Signal. 5, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zhang B. B., Zhou G., Li C. (2009) Cell Metab. 9, 407–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Thomson D. M., Winder W. W. (2009) Acta Physiol. 196, 147–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhou W., Simpson P. J., McFadden J. M., Townsend C. A., Medghalchi S. M., Vadlamudi A., Pinn M. L., Ronnett G. V., Kuhajda F. P. (2003) Cancer Res. 63, 7330–7337 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Berishaj M., Gao S. P., Ahmed S., Leslie K., Al-Ahmadie H., Gerald W. L., Bornmann W., Bromberg J. F. (2007) Breast Cancer Res. 9, R32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Diaz N., Minton S., Cox C., Bowman T., Gritsko T., Garcia R., Eweis I., Wloch M., Livingston S., Seijo E., Cantor A., Lee J. H., Beam C. A., Sullivan D., Jove R., Muro-Cacho C. A. (2006) Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 20–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]