Background: Nrf1 regulates cellular stress response, but nothing is known about how Nrf1 is regulated.

Results: Fbw7 binds Nrf1 to promote its ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome.

Conclusion: Nrf1 expression is regulated by Fbw7.

Significance: These findings broaden the understanding of how Nrf1 is regulated and suggest that Fbw7 may regulate cellular stress response by controlling turnover of the Nrf family of proteins.

Keywords: Gene Regulation, Oxidative Stress, Protein Turnover, Transcription Factors, Ubiquitin Ligase, CNC-bZIP

Abstract

Nuclear factor E2-related factor 1 (Nrf1) is a basic leucine zipper transcription factor that plays important roles in cellular stress response and development. Currently, the mechanism regulating Nrf1 expression is poorly understood. We report here that Nrf1 is a short-lived protein that is targeted by F-box protein Fbw7, which is the substrate-specifying component of SCF (Skp1-Cul1-Fbox protein-Rbx1)-type ubiquitin ligase for degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. We show that Fbw7 directly binds Nrf1 through a Cdc4 phosphodegron and that enforced expression of Fbw7 promotes the ubiquitination and degradation of Nrf1. Conversely, depletion of endogenous Fbw7 leads to decreased Nrf1 ubiquitination and accumulation of Nrf1 protein. Accordingly, expression of Fbw7 leads to down-regulation of antioxidant response element-driven gene activation, whereas disruption of Fbw7-mediated destabilization of Nrf1 leads to increased antioxidant response element-driven gene expression. Together, these data identify Fbw7 as a regulator of Nrf1 expression and reveal a novel function of Fbw7 in cellular stress response.

Introduction

Nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-related factor 1 (Nrf1)2 is a member of the CNC subfamily of basic leucine zipper (CNC-bZIP) transcription factors, which also includes p45 NF-E2, Nrf2, Nrf3, Bach1, and Bach2 (1–5). Members of this protein family are characterized by a 43-amino acid homology region, termed the “CNC” (cap-n-collar) domain, located immediately at the N terminus of the basic DNA-binding domain (6). CNC-bZIP transcription factors form heterodimers with small Maf proteins (Maf G, Maf K, and Maf F) and cAMP-response element-binding protein/activating transcription factor proteins for DNA binding (7).

Nrf1 is ubiquitously expressed, and high levels are seen in muscle, heart, kidney, and brain (2). Nrf1 has been implicated in various developmental processes and in maintaining cellular homeostasis (8). In addition, loss of Nrf1 function in hepatocytes leads to liver tumors in mice, suggesting that Nrf1 functions as a tumor suppressor (9). Nrf1 has been shown to control expression of genes involved in cellular stress response through cis-acting sequences known as antioxidant response elements (AREs) (10, 11). These elements have been identified in the regulatory regions of genes encoding phase-2 detoxification enzymes and various other cytoprotective proteins such as NADPH quinone oxidoreductase, metallothioneins, glutamate-cysteine ligase, and as recently revealed, genes encoding subunits that make up the proteasome (11–15).

Several Nrf1 isoforms have been reported. Previous data indicate that the 120-kDa isoform of Nrf1 (herein referred as Nrf1 for simplicity) is retained in the endoplasmic reticulum, whereas the N-terminal-truncated form (65 kDa) appears to be constitutively localized to the nucleus (16, 17). Although molecular details involved in the endoplasmic reticulum to nuclear translocation of Nrf1 have yet to be defined, evidence suggests that Nrf1 mediates gene activation, whereas the 65-kDa protein antagonizes ARE-mediated gene expression (17). Expression of Nrf1 is up-regulated in response to oxidative stress, but the underlying mechanisms are not known (18). Nrf1 shares structural similarities with Nrf2, including the presence of a functional Neh2 (Nrf2-ECH homology 2) domain that serves to destabilize Nrf2 through interaction with the Keap1 protein. Although Nrf1 binds Keap1, Keap1 does not appear to regulate Nrf1 function or its localization in the cell (16, 19).

The ubiquitin proteasome system regulates the turnover of a number of transcription factors (20). Proteins regulated by the ubiquitin proteasome system are first conjugated with ubiquitin moieties, and ubiquitinated substrates are subsequently targeted to the 26 S proteasome where they undergo proteolysis. The addition of ubiquitin conjugates occurs through the successive action of three classes of enzymes, including ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2), and ubiquitin-protein ligase (E3) (21). Although there are one or two E1(s) and dozens of E2s, there are hundreds of E3s that are substrate-specific.

E3 ligases are classified on the basis of their subunit composition. Cullin-RING type ligase forms a large class of E3s that regulate a wide variety of protein polyubiquitylation events. The SCF complex is an archetypal Cullin-RING type ligase that is composed of Cullin-1 (Cul1) protein that acts as a scaffold. Cul1 binds Rbx1 (Roc1/Hrt1), a RING finger protein that recruits E2-conjugating enzymes, and Skp1, an adaptor protein that recruits F-box proteins (22). Many F-box motif-containing proteins have been identified, and they function as adaptors to recruit specific substrates to the complex (22). The F-box protein, Fbw7 (also known as AGO, CDC4, and SEL10), has been shown to regulate a number of transcription factors, including, c-Myc, c-Jun, c-Myb, and sterol regulatory element binding proteins (23). In this present study, we demonstrate that Nrf1 expression is regulated, by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway through the F-box protein Fbw7.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), and Lipofectamine 2000 were purchased from Invitrogen. The Myc tag (9B11) mouse monoclonal antibody, hemagglutinin (HA) tag (6E2) monoclonal antibody, horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit IgG, and anti-mouse IgG antibodies were from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA). Anti-FLAG (M2) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and Cdc4/Fbw7/hSel 10 antibody (12292) was purchased from Abcam. MG132 and cycloheximide were purchased from Sigma. Nrf1 antibody has been previously described (16).

Plasmids

pCMVNrf1-Myc was generated as described previously (16). Deletions of Cdc4 phosphodegron (CPD) motifs in Myc-tagged Nrf1 were generated using a Phusion Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) with the following primers: 5′-GGGACAGAATCACCATTTGATTTG and 3′-CTCACTCTCACTAGGCACTGC; 5′-AGCCTGCCTGTGGCTAGCAGCTCC and 3′-GAAGAGGGAGAAGTCCTGACTGC for Nrf1Δ269–273 and Nrf1Δ350–354 constructs, respectively. The Nrf1 Δ269–273;350–354 double deletion construct was generated by PCR amplification of Nrf1Δ350–354 using primers for the Δ269–273 deletion. pcDNA3-DN-hCUL1-flag, pcDNA3-DN-hCUL2-flag, pcDNA3-DN-hCUL3-flag, pcDNA3-DN-hCUL4A-flag, pcDNA3-DN-hCUL4B-flag, and pRetrosuper Fbw7 shRNA-1 and -2 were from Addgene. A dominant negative, FLAG-tagged Cullin-5 construct was a gift from Dr. A. J. Berk's laboratory (University of California, Los Angeles). pFLAG-Fbw7alpha, pFLAG-Fbw7beta, and pFLAG-Fbw7gamma were a gift from Guy J. Rosman and A. Dusty Miller (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA). The Luciferase reporter driven by the NQO1 ARE was a gift from Dr. J. Johnson (University of Wisconsin, Madison). HA-tagged expression plasmids encoding Fbw1a, Fbw2, Fbw4, and Fbw7 were gifts from Dr. M. Matsumoto (Kyushu University, Japan). HA-tagged Ubiquitin expression plasmid was a gift from Dr. Peter Kaiser (University of California, Irvine). GRP78-Luc plasmid was from Dr. Amy Lee (University of Southern California, Los Angeles).

Cell Culture

293 HEK cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 units/ml penicillin at 37 °C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere. The cells were transfected using Lipofectamine reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol. The cells were plated at least 8 h before transfection. The cells were harvested 48 h after transfection, and cellular extracts were prepared.

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in cold radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm EDTA, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, 5 μg/ml leupeptin) and cleared by centrifugation for 15 min at 4 °C. Protein concentrations were determined using Bio-Rad protein assay reagent. An equal volume of 2× SDS sample buffer (100 mm Tris, pH 6.8, 25% glycerol, 2% SDS, 0.01% bromphenol blue, 10% 2-mercaptoethanol) was added to cell lysates, and the mixture was boiled for 5 min. The samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking with 5% skim milk in TBS-T (150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 0.05% Tween-20), the membranes were probed with the indicated antibodies. The antibody-antigen complexes were detected using the ECL system.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Subconfluent HEK293 cells were transfected with pFLAG-Fbw7alpha, pFLAG-Fbw7beta, pFLAG-Fbw7gamma, and Nrf1 expression vectors or just pFLAG-Fbw7alpha, pFLAG-Fbw7beta, pFLAG-Fbw7gamma, or HA-Ub and pRetrosuper Fbw7 shRNA-1 and -2 using Lipofectamine 2000, and then lysed in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer 48 h after transfection. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation for 15 min at 4 °C followed by overnight incubation with anti-Myc antibody or anti-Nrf1 antibody. The next day, protein G-Sepharose beads were added followed by a 1-h incubation in the cold. The beads were collected by brief centrifugation and then washed extensively with radioimmune precipitation assay buffer. The proteins were eluted in 1× SDS sample buffer and heating at 95 °C for 5 min. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, followed by immunoblotting with indicated primary antibodies and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Detection of peroxidase signal was performed using the enhanced chemiluminescence method.

Luciferase Assay

Cells were transfected in 24-well plates using Lipofectamine. Expression from Renilla luciferase was used to determine transfection efficiency. After 48 h, cells were lysed and subjected to the luciferase assay using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter System (Promega, Madison, WI), and light units were measured on a TD20/20 Luminometer (Turner Design, Sunnyvale, CA).

RESULTS

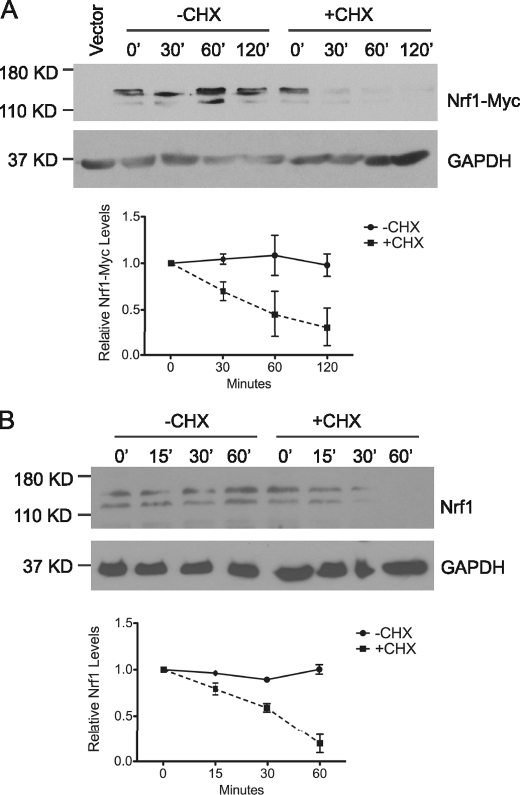

Nrf1 Is an Unstable Protein

To examine the half-life of Nrf1 protein, a cycloheximide chase assay of HEK293 cells transfected with Myc-tagged Nrf1 (Nrf1-Myc) was performed. Immunoblot analysis showed Nrf1-Myc levels decreased steadily following protein synthesis inhibition by cycloheximide treatment (Fig. 1A). The half-life of Nrf1-Myc in HEK293 cells was <30 min, and almost no protein could be detected after 60 min of incubation in cycloheximide. Cycloheximide chase analysis of endogenous Nrf1 in HEK293 cells showed a short half-life similar to exogenously expressed Nrf1 (Fig. 1B). Analogous results were obtained in different cell lines (mouse embryonic fibroblasts, HeLa) suggesting that the short half-life of the Nrf1 protein is independent of cell type (data not shown). Together these results indicate that Nrf1 is an unstable protein.

FIGURE 1.

Nrf1 has a short half-life. A, HEK293 cells were transfected with vector or Myc-tagged Nrf1, followed by treatment with 50 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) for 0, 30, 60, and 120 min. Western blot analysis was done on the whole cell lysates using anti-Myc antibody. GAPDH was used as the loading control. The graph shows quantitative analysis of CHX chase data. Each point represents the mean (± S.E.) of the remaining protein. B, HEK293 cells were treated with 50 μg/ml CHX for 0, 30, 60, and 120 min. Western blot analysis was done on the whole cell lysates for detection of endogenous Nrf1 using anti-Nrf1 antibody. GAPDH was used as the loading control. The graph shows quantitative analysis of cycloheximide chase data. Each point represents the mean (± S.E.) of the remaining protein.

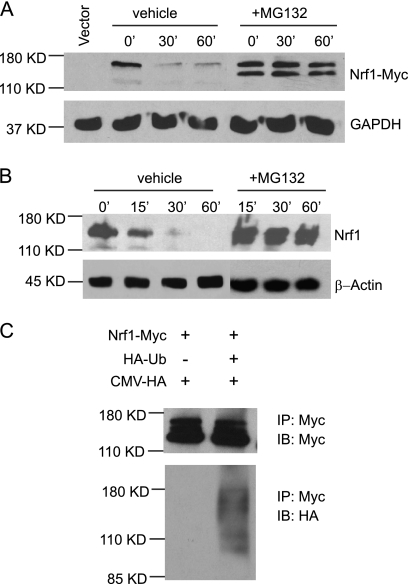

Nrf1 Is Degraded by Ubiquitin-dependent Pathway

Degradation of many transcription factors proceeds via the 26 S proteasome pathway. Thus, we examined the effect of 26 S proteasome inhibition on the turnover of Nrf1. Inhibition of proteasome activity by MG132 treatment increased Nrf1-Myc protein levels in HEK293 cells (Fig. 2A). The effect of proteasome inhibition on endogenous Nrf1 was also determined by immunoblotting. A marked increase in endogenous Nrf1 protein levels was also seen in HEK293 cells after MG132 treatment (Fig. 2B). Cells treated with epoxomicin, which is another proteasome inhibitor, showed similar results (data not shown) indicating that stabilization is not restricted to MG132 treatment.

FIGURE 2.

Nrf1 is ubiquitinated and stabilized by proteasomal inhibition. A, HEK293 cells were transfected with Nrf1-Myc, followed by treatment with vehicle (DMSO) or 10 μm of the proteasomal inhibitor, MG132, for 5 h followed by treatment with 50 μg/ml CHX. Cells were harvested at 0, 30, and 60 min, and Western blotting was done using an anti-Myc antibody. GAPDH was used as the loading control. B, HEK293 cells were treated vehicle (DMSO) or 10 μm of the proteasomal inhibitor, MG132, for 5 h followed by treatment with 50 μg/ml CHX. Cells were harvested at 0, 30, and 60 min, and Western blotting was done on endogenous Nrf1 using anti-Nrf1 antibody. GAPDH was used as the loading control. C, HEK293 cells were transfected with Nrf1-Myc, HA-Ub, and CMV-HA. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Myc antibody and analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-ubiquitin antibody. For input control, filter was blotted with anti-Myc antibody.

Proteins targeted for proteasome destruction are polyubiquitinated. To obtain evidence that Nrf1 is ubiquitinated, an in vivo ubiquitination assay was performed. HEK293 cells expressing Nrf1-Myc alone, or in combination with HA-tagged ubiquitin (HA-Ub) were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody, and Nrf1 proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting using an anti-HA antibody. High molecular weight species of Nrf1 were observed in cells co-expressing HA-tagged ubiquitin and Nrf1-Myc (Fig. 2C), indicating that Nrf1 is subjected to ubiquitination in cells. Together, these findings suggest that the proteasome pathway plays a role in regulating Nrf1 stability in the cell.

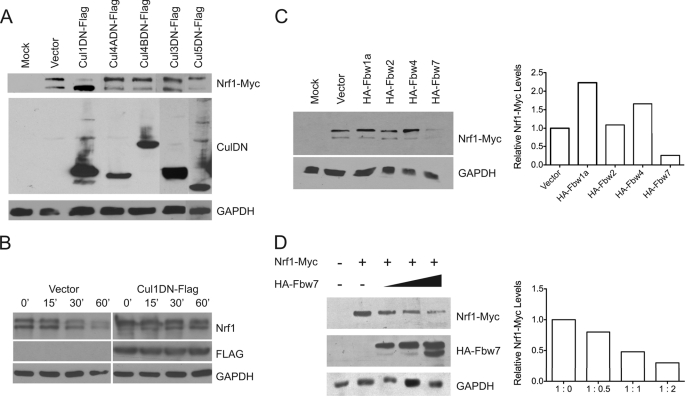

SCFFbw7 Facilitates Nrf1 Turnover

To identify the specific E3 ligase complex that targets Nrf1 for degradation, the effect of dominant-negative cullins on Nrf1 protein stability was examined. HEK293 cells were transfected with Myc-tagged Nrf1 alone or together with expression vectors encoding various dominant-negative cullin proteins, and levels of Nrf1-Myc was analyzed by Western blotting. Co-expression of a dominant negative mutant of cullin 1 (Cul1DN) increased Nrf1-Myc levels in HEK293 cells (Fig. 3A). In contrast, co-expression of other dominant negative cullin proteins (Cul3DN, 4ADN, 4BDN, and 5DN) had no effect on Nrf1-Myc levels. Endogenous Nrf1 was also increased by expression of Cul1DN in HEK293 cells (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Nrf1 is destabilized by SCFFbw7. A, HEK293 cells were transfected with Nrf1-Myc, and FLAG-tagged dominant negative constructs of Cullin 1, 3, 4A, 4B, and 5. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-Myc and anti-FLAG antibodies. Protein loading was determined by immunoblotting against GAPDH. B, HEK293 cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged dominant negative Cullin 1 expression plasmid. 48 h after transfection, the cells were treated with 50 μg/ml CHX and harvested after 0, 15, 30, and 60 min. Cell extracts were immunoblotted for endogenous Nrf1, using Nrf1 antibody, and for Cul1DN expression using anti-FLAG antibody. GAPDH was used as the loading control. C, HEK293 cells were transfected with Nrf1-Myc and HA-tagged F-box expression constructs. Cells were harvested 48 h thereafter and Western blotted with anti-Myc. GAPDH was used as the loading control. D, Nrf1-Myc and HA-Fbw7 were co-transfected in HEK293 cells in the ratios 1:0, 1:0.5, 1:1, and 1:2. Cell extracts were analyzed for Nrf1-Myc and Fbw7 expression by using anti-Myc and anti-FLAG antibodies. Protein loading was determined by GAPDH immunoblotting. Densitometric quantitations of band intensities are shown in the bar graphs.

Cullin1 acts as scaffold protein for the SCF (Skp1/Cullin/F-box protein) class of E3 ubiquitin ligases, and F-box proteins serve as substrate-specific adaptors of the SCF complex. To identify F-box proteins that regulate Nrf1, we examined the effects of a panel of expression constructs for F-box proteins on Nrf1 stability in cells. F-box expression plasmids were transfected along with Myc-tagged Nrf1 plasmid, and expression of Nrf1-Myc was examined by immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 3C, expression of Fbw7 reduced the expression of Nrf1-Myc in HEK293 cells. In contrast, co-expression of other F-box proteins (Fbw1a, Fbw2, and Fbw4) did not reduced Nrf1-Myc levels in HEK293 cells (Fig. 3C). In addition, enforced expression of Fbw7 decreased endogenous Nrf1 levels in a dose-dependent manner in HEK293 cells. These results suggest that Fbw7 is a specific ligase for Nrf1 (Fig. 3D).

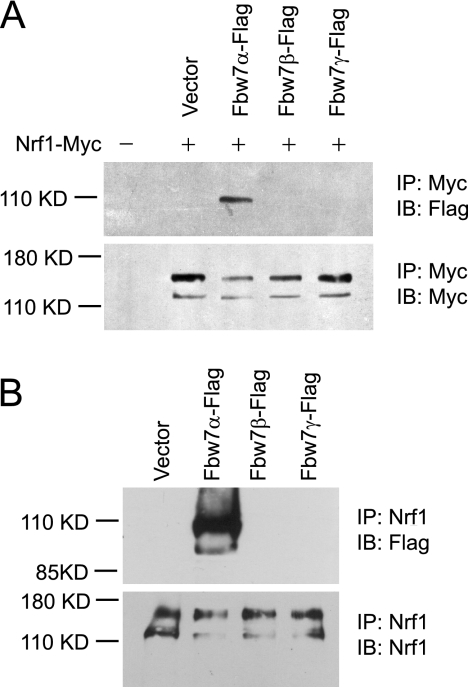

Fbw7 Binds Nrf1

To determine if Nrf1 interacts with Fbw7, co-immunoprecipitation assays were done. Fbw7 has three isoforms (α, β, and γ) that are generated by alternative splicing (24). The three proteins differ at their N termini, but the substrate-binding domain located at the C terminus is identical in all three isoforms, and each is localized to different subcellular compartments (24). HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with Myc-tagged Nrf1 alone and in combination with the three different isoforms of Fbw7 that are tagged with the FLAG-epitope. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibodies and then probed for Fbw7 by anti-FLAG antibody. Western blotting revealed that the nuclear-localized Fbw7α was readily co-precipitated with Nrf1-Myc (Fig. 4A). In contrast, only small amounts of the cytoplasmic Fbw7β and nucleolar Fbw7γ were detected in the Nrf1-Myc immunoprecipitates after long exposure of the Western blots (data not shown). To determine if endogenous Nrf1 and Fbw7 could interact, HEK293 cells transfected with the different isoforms of Fbw7 that are FLAG-tagged were immunoprecipitated with anti-Nrf1 antibody and probed for FLAG. Western blotting revealed that Fbw7α co-precipitated with endogenous Nrf1 (Fig. 4B). These results demonstrate that Nrf1 and Fbw7α proteins interact with each other in vivo.

FIGURE 4.

Nrf1 and Fbw7 interact in vivo. A, HEK293 cells were transfected with equal amounts of Nrf1-Myc and FLAG-tagged Fbw7α, Fbw7β, or Fbw7γ. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody, followed by Western blotting with anti-Myc or anti-FLAG antibody. B, HEK293 cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged Fbw7α, Fbw7β, or Fbw7γ. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-Nrf1 antibody, followed by immunoblotting with anti-Nrf1 or anti-FLAG antibody.

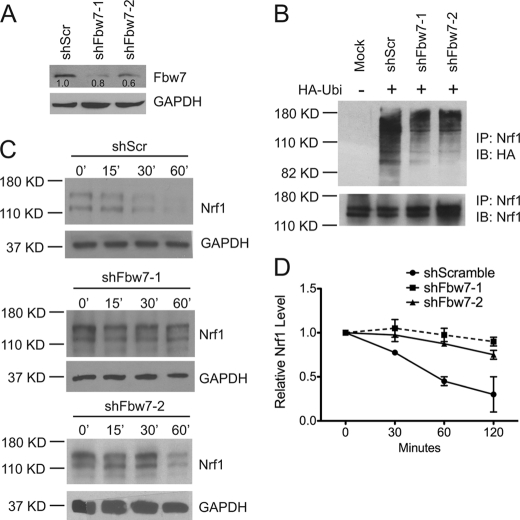

Knockdown of Fbw7 Stabilizes Nrf1

To further establish a role for Fbw7 in regulating Nrf1, the effects of Fbw7 knockdown on Nrf1 were examined. Two different shRNA constructs were used to knock down Fbw7 in HEK293cells, and efficiencies of Fbw7 knockdown were determined by immunoblotting. Compared with cells expressing scramble control shRNA (shScr), shFbw7-1 and shFbw7-2 decreased expression of Fbw7 by 80 and 60%, respectively (Fig. 5A). Using these knockdown constructs, we next tested the effect of Fbw7 depletion on ubiquitination of Nrf1. HEK293 cells were transfected with HA-tagged ubiquitin along with shFbw7-1, shFbw7-2, or shScr control, and endogenous Nrf1 was immunoprecipitated with anti-Nrf1 and then immunoblotted with anti-HA antibody. Compared with cells expressing shScr control, expression of shFbw7-1 or shFbw7-2 reduced the level of ubiquitinated derivatives of Nrf1 (Fig. 5B). We next assessed the effect of Fbw7 knockdown on turnover of endogenous Nrf1 protein. A cycloheximide chase assay revealed that the half-life of Nrf1 in shFbw7-1 and shFbw7-2 knockdown cells was increased compared with cells expressing shScr (Fig. 5, C and D). These data suggest that Fbw7 facilitates the ubiquitination and degradation of Nrf1.

FIGURE 5.

Nrf1 is stabilized by depletion of Fbw7. A, HEK293 cells were transfected with scramble-control, Fbw7shRNA1, and Fbw7shRNA2. Knockdown of endogenous Fbw7 expression was analyzed 48 h thereafter by immunoblotting using anti-Fbw7 antibody. Equal loading of lanes was determined by GAPDH Western blotting. B, HEK293 cells were transfected with HA-tagged ubiquitin and scramble-control, Fbw7shRNA1, or Fbw7shRNA2. Endogenous Nrf1 was then immunoprecipitated with anti-Nrf1 antibody, and then immunoblotted with anti-HA antibody. Immunoprecipitates were also immunoblotted with anti-Nrf1 antibody as loading control. C, HEK293 cells were transfected with scramble-control, Fbw7shRNA1, and Fbw7shRNA2. 48 h later, cells were treated with 50 μg/ml CHX and harvested at 0, 15, 30, and 60 min after treatment for Western blotting against Nrf1. Protein loading was determined by GAPDH immunoblotting. D, the graph shows quantitative analysis of cycloheximide chase data in C. Each point represents the mean (± S.E.) of the remaining protein.

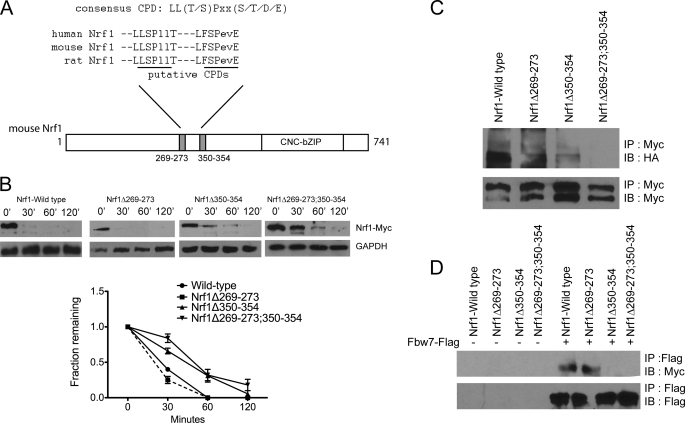

Fbw7 Regulates Nrf1 via a CPD Motif

The action of SCF ligase is dependent on binding by F-box proteins to substrates that are modified by phosphorylation (25), and Fbw7 is known to target substrates containing a consensus motif termed the Cdc4 phosphodegron (CPD) comprising residues that are phosphorylated by serine/threonine kinases (26). As shown in Fig. 6A, sequence analysis of Nrf1 revealed two putative CPDs located at residues 269–273 and 350–354. To test if these motifs in Nrf1 are critical for regulation by Fbw7, Myc-tagged Nrf1Δ269–273, Nrf1Δ350–354, and Nrf1Δ269–273;350–354 deletion constructs were generated. Cycloheximide chase studies were done to examine the effects of the deletions on Fbw7-mediated degradation. Compared with wild-type Nrf1, deletion of residues 269–273 did not affect protein stability (Fig. 6B). In contrast, the half-life of Nrf1 was increased 2-fold by deletion of residues 350–354 (Fig. 6B). The half-life of the double mutant Nrf1Δ269–273;350–354 was similar to 350–354 deletion mutant suggesting that only the second CPD motif at residues 350–354 is a functional Fbw7 degradation signal. We next tested the effect of the deletions on ubiquitination of Nrf1. Myc-tagged deletion constructs were transfected into HEK293 cells along with HA-tagged ubiquitin. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc and then immunoblotted with anti-HA antibody. Consistent with the above results, deletion of residues 350–354 reduced the level of Nrf1 ubiquitination compared with cells expressing wild-type Nrf1 (Fig. 6C). Next, HEK293 cells were co-transfected with FLAG-tagged Fbw7 along with either Nrf1Δ269–273, Nrf1Δ350–354, or Nrf1Δ269–273;350–354 to examine binding with Fbw7. Both wild-type Nrf1 and Nrf1Δ269–273 co-precipitated with Fbw7 (Fig. 6D). In contrast, Nrf1Δ350–354 and Nrf1Δ269–273;350–354 did not form a detectable complex with Fbw7 (Fig. 6D). Together, these data indicate that the CPD located at residues 350–354 of Nrf1 interacts with Fbw7 and functions as a degradation motif.

FIGURE 6.

Fbw7 regulates Nrf1 via a CPD motif. A, schematic diagram of Nrf1 showing two putative Cdc4 CPDs. Alignment of Nrf1 proteins from various species shows strong conservation of the putative CPDs. B, HEK293 cells were transfected from the indicated Myc-tagged Nrf1 constructs. Following CHX treatment at the indicated times, whole cell lysates were Western-blotted for Myc. GAPDH was used as the loading control. The graph shows quantitative analysis of CHX chase data from two experiments. Each point represents the mean (± S.E.) of the remaining protein. C, HEK293 cells were transfected with HA-Ub and the indicated Myc-tagged Nrf1 constructs. Lysates were then subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-Myc antibodies followed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody. For input control, the membrane was blotted with anti-Myc antibody. D, plasmids expressing Myc-tagged wild-type and deletion mutants of Nrf1 were co-transfected with FLAG-Fbw7. Lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG antibody followed by immunoblotting for Myc. For input control, the membrane was blotted with anti-FLAG antibody.

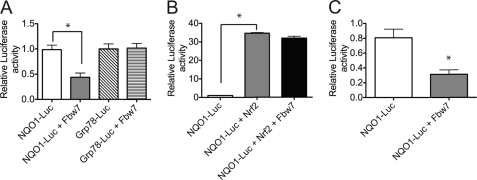

Fbw7 Limits Nrf1-mediated Activation of ARE-driven Gene Activation

To determine the biological implications of Fbw7 regulating Nrf1 turnover, we monitored the effect of Fbw7 on Nrf1-mediated activation of ARE-driven genes. Enforced expression of Fbw7 reduced ARE-driven luciferase expression by 50% in HEK293 cells (Fig. 7A). However, the expression of GRP78-luciferase, which was under the control of an unrelated promoter element, was not affected by Fbw7 (Fig. 7A). To exclude the possibility that the effects of Fbw7 on ARE-luciferase expression are mediated through Nrf2, we examined whether Fbw7 can down-regulate Nrf2-mediated reporter activation. As shown in Fig. 7B, reporter expression was activated by transfection of Nrf2, and expression of Fbw7 did not suppress reporter activation by Nrf2. To further substantiate these results, the effect of Fbw7 on ARE-mediated gene activation was examined in Nrf2−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Similar to results obtained in HEK293 cells, Fbw7 suppressed luciferase expression in Nrf2-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (Fig. 7C). These results suggest that Fbw7 can modulate ARE-mediated gene transcription in cells through Nrf1.

FIGURE 7.

Fbw7 limits Nrf1-mediated ARE gene activation. A, luciferase expression in HEK293 cells transiently co-transfected with Fbw7 expression plasmid and NQO1- or GRP78-luciferase reporter construct. Promoter activity was analyzed by Dual-Luciferase assay. Data represent luciferase activities normalized to Renilla luciferase. B, luciferase expression in HEK293 cells transiently transfected with the NQO1-luciferase reporter along with Nrf2 or Nrf2 and Fbw7. C, luciferase expression in Nrf2−/− mouse embryonic fibroblast cells transiently transfected with the NQO1-luciferase reporter with and without Fbw7 expression plasmid. Data represent luciferase activities normalized to Renilla luciferase activities. Experiments were performed three times, and error bars represent ± S.D. *, p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Here we report that the Nrf1 transcription factor is a labile protein, and it is targeted by the SCFFbw7 ubiquitin ligase for proteasome degradation. We provide evidence to show that (i) Nrf1 expression is down-regulated by enforced expression of Fbw7; (ii) Nrf1 binds Fbw7; (iii) Fbw7 promotes Nrf1 ubiquitination in vivo; (iv) Nrf1 expression is stabilized by shRNA-mediated knockdown of Fbw7; (v) Fbw7 regulates Nrf1 in a CPD-dependent manner; and (vi) activation of Nrf1-dependent transcription is modulated by Fbw7 expression. These data indicate that Fbw7 as a regulator of Nrf1 stability and function.

Nrf1 has been shown to regulate ARE-driven genes encoding antioxidant proteins, and recently, genes encoding the proteasome. Because sustained activation of stress-response genes is thought to be deleterious to the cell, the rapid turnover of Nrf1 allows Nrf1-dependent pathways to be turned off after triggers of cellular stress have been eliminated. Although Nrf1 has been shown recently to be targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation pathway mediated by Hrd1 E3 ligase (27), it is not clear how this pathway regulates the active pool of Nrf1 given that nuclear localization is necessary for transcription factors to function. It is possible that the endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation pathway may play a role in regulating steady-state levels of Nrf1. It is known that proteasomes are also present in the nucleus, and other transcription factors have been shown to undergo ubiquitination and proteasome degradation in this compartment (28–30). Our results suggests the active pool of Nrf1 in the nucleus is regulated by Fbw7α, the nuclear isoform of Fbw7. Consistent with this notion, we show that endogenous Nrf1 binds with Fbw7α, and little or no binding to the cytoplasmic or nucleolar isoform was observed even though all three Fbw7 isoforms share the same substrate-binding domain. We also show that overexpression of Fbw7 decreased activation of ARE-driven promoter by Nrf1, whereas depletion of endogenous Fbw7 enhanced ARE-mediated gene activation. The ability to degrade Nrf1 in the nucleus is advantageous to the cell, because it allows for rapid control when an active Nrf1 response is no longer needed.

Although Fbw7-mediated turnover of Nrf1 is addressed here, other mechanisms of Nrf1 down-regulation are likely to be involved given that Nrf1 has been implicated in other cellular functions. Nrf1 contains an Neh2-like domain located near its N terminus (16). The Neh2 domain in Nrf2 functions to recruit Keap1, a component of Cullin-3-type ubiquitin E3 ligase for ubiquitin-dependent degradation under normal conditions (31, 32). Upon exposure to oxidative stress, Keap1-Nrf2 interaction is disrupted thus allowing stabilization of Nrf2 with subsequent induction of antioxidant gene expression. Although Nrf1 has been shown to interact with Keap1 via the Neh2 domain, deletion of the Neh2-like domain in Nrf1 does not appear to affect its function or localization in the cell (16). Consistent with these previous results, the stability of Nrf1 was not affected by expression of a dominant-negative mutant of cullin-3. Whether Keap1 contributes directly to Nrf1 expression will require further studies.

In summary, we have shown that Nrf1 is a substrate for Fbw7, and Fbw7 targets Nrf1 for ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation. Fbw7 is a tumor suppressor that is frequently inactivated in different types of cancer (33). Nrf1 has also been linked to liver cancer in mice (9). However, Nrf1 may function as a tumor suppressor in this instance as tumorigenesis is associated with inactivation of Nrf1 in hepatocytes. Nonetheless, one could envision that up-regulation of Nrf1, through Fbw7 deficiency, might provide cells undergoing transformation a growth advantage by increased expression of stress response genes. Hence, it is reasonable to speculate that up-regulation of Nrf1, together with other Fbw7 substrates, such as c-Jun, c-Myc, and cyclin E, promotes tumorigenesis.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant CA091907.

- Nrf1

- nuclear factor E2-related factor 1

- ARE

- antioxidant response element

- Cul1

- Cullin-1

- CPD

- Cdc4 phosphodegron

- Cul1DN

- dominant negative Cullin-1

- SCF

- Skp1-Cul1-Fbox protein-Rbx1

- shScr

- scramble control shRNA

- CNC

- cap-n-collar.

REFERENCES

- 1. Andrews N. C., Erdjument-Bromage H., Davidson M. B., Tempst P., Orkin S. H. (1993) Nature 362, 722–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chan J. Y., Han X. L., Kan Y. W. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 11371–11375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kobayashi A., Ito E., Toki T., Kogame K., Takahashi S., Igarashi K., Hayashi N., Yamamoto M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 6443–6452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moi P., Chan K., Asunis I., Cao A., Kan Y. W. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 9926–9930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oyake T., Itoh K., Motohashi H., Hayashi N., Hoshino H., Nishizawa M., Yamamoto M., Igarashi K. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 6083–6095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chan J. Y., Cheung M. C., Moi P., Chan K., Kan Y. W. (1995) Hum. Genet. 95, 265–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Motohashi H., O'Connor T., Katsuoka F., Engel J. D., Yamamoto M. (2002) Gene 294, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Biswas M., Chan J. Y. (2010) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 244, 16–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xu Z., Chen L., Leung L., Yen T. S., Lee C., Chan J. Y. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 4120–4125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Johnsen O., Murphy P., Prydz H., Kolsto A. B. (1998) Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 512–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kwong M., Kan Y. W., Chan J. Y. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 37491–37498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Myhrstad M. C., Husberg C., Murphy P., Nordström O., Blomhoff R., Moskaug J. O., Kolsto A. B. (2001) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1517, 212–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ohtsuji M., Katsuoka F., Kobayashi A., Aburatani H., Hayes J. D., Yamamoto M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33554–33562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Radhakrishnan S. K., Lee C. S., Young P., Beskow A., Chan J. Y., Deshaies R. J. (2010) Mol. Cell 38, 17–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Venugopal R., Jaiswal A. K. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 14960–14965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang W., Chan J. Y. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 19676–19687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang W., Kwok A. M., Chan J. Y. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 24670–24678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhao R., Hou Y., Xue P., Woods C. G., Fu J., Feng B., Guan D., Sun G., Chan J. Y., Waalkes M. P., Andersen M. E., Pi J. (2011) Environ. Health Perspect. 119, 56–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang Y., Crouch D. H., Yamamoto M., Hayes J. D. (2006) Biochem. J. 399, 373–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schwartz A. L., Ciechanover A. (2009) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 49, 73–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pickart C. M. (2001) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 503–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Petroski M. D., Deshaies R. J. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 9–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fujii Y., Yada M., Nishiyama M., Kamura T., Takahashi H., Tsunematsu R., Susaki E., Nakagawa T., Matsumoto A., Nakayama K. I. (2006) Cancer Sci. 97, 729–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Welcker M., Clurman B. E. (2008) Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 83–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Steffen J., Seeger M., Koch A., Krüger E. (2010) Mol. Cell 40, 147–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Floyd Z. E., Trausch-Azar J. S., Reinstein E., Ciechanover A., Schwartz A. L. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 22468–22475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lenk U., Sommer T. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 39403–39410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shirangi T. R., Zaika A., Moll U. M. (2002) Faseb J. 16, 420–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Minella A. C., Clurman B. E. (2005) Cell Cycle 4, 1356–1359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hao B., Oehlmann S., Sowa M. E., Harper J. W., Pavletich N. P. (2007) Mol. Cell 26, 131–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang H. C., Nguyen T., Pickett C. B. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 42769–42774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kobayashi M., Yamamoto M. (2005) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 7, 385–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Crusio K. M., King B., Reavie L. B., Aifantis I. (2010) Oncogene 29, 4865–4873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]