Background: Ileal bile acid-binding proteins display different degrees of binding cooperativity.

Results: The structure of a low cooperativity protein complexed with bile salts was determined. The protein was mutated to enhance its cooperativity.

Conclusion: Cooperative binding requires few latch residues to stabilize an H-bond network.

Significance: Knowledge of the determinants of cooperativity in protein carriers is the key to understanding bile acid trafficking.

Keywords: Cooperativity, Lipid-binding Protein, Molecular Dynamics, NMR, Protein Structure

Abstract

Ileal bile acid-binding proteins (I-BABP), belonging to the family of intracellular lipid-binding proteins, control bile acid trafficking in enterocytes and participate in regulating the homeostasis of these cholesterol-derived metabolites. I-BABP orthologues share the same structural fold and are able to host up to two ligands in their large internal cavities. However variations in the primary sequences determine differences in binding properties such as the degree of binding cooperativity. To investigate the molecular requirements for cooperativity we adopted a gain-of-function approach, exploring the possibility to turn the noncooperative chicken I-BABP (cI-BABP) into a cooperative mutant protein. To this aim we first solved the solution structure of cI-BABP in complex with two molecules of the physiological ligand glycochenodeoxycholate. A comparative structural analysis with closely related members of the same protein family provided the basis to design a double mutant (H99Q/A101S cI-BABP) capable of establishing a cooperative binding mechanism. Molecular dynamics simulation studies of the wild type and mutant complexes and essential dynamics analysis of the trajectories supported the role of the identified amino acid residues as hot spot mediators of communication between binding sites. The emerging picture is consistent with a binding mechanism that can be described as an extended conformational selection model.

Introduction

Intracellular bile acid-binding proteins (BABP)2 belong to the fatty acid-binding protein (FABP) family and are composed of small (14–15 kDa) β-barrel proteins that act as lipid chaperones (1–3). Specifically, BABPs are found abundantly expressed in the enterocytes and hepatocytes of various vertebrates and have been shown to play a pivotal role in the transcellular trafficking and enterohepatic circulation of bile salts (4). During the last decade a growing amount of evidence has been presented to show that the various FABPs that interact with lipids not only facilitate their transport in aqueous media but, by interacting with specific targets, also modulate their subsequent biological action or metabolism (5). Thus, structural and mechanistic knowledge of the interactions between lipids and their cognate binding proteins has become mandatory in understanding the action of lipids as signaling compounds and metabolic intermediates (6).

The binding features of BABPs appear difficult to capture, although recent studies have set important milestones in the atomic level description of BABP-ligand interactions (7–10). It has been definitively ascertained that BABPs can form at least ternary complexes by hosting two ligand molecules inside a large protein cavity (11–14). One of the most intriguing features described for some members of the family relates to binding cooperativity, i.e. the energetic coupling between separate binding sites, a property that provides an additional level of signaling or regulation. Human ileal BABP (hI-BABP) and chicken liver BABP (cL-BABP) display an extraordinary degree of positive cooperativity associated with two internal binding sites, illustrated qualitatively by a Hill coefficient close to 2 (11, 15). The two proteins can thus effectively sequester ligands from the intracellular milieu, suggesting that they play a role in offering cytoprotection against high concentrations of bile acids. Cooperativity often arises from allosteric communication, a phenomenon that frequently escapes detection by common biochemical approaches (16). NMR and calorimetric studies performed on hI-BABP and on a series of mutants have attempted to identify the communication pathways between the two binding sites (9, 10). Further interaction studies reported for other members of the BABP family describe the binding stoichiometry and affinity of the rabbit ileal protein (rI-BABP) (17) as well as the binding thermodynamics and crystallographic structure of fully complexed zebrafish ileal protein (zI-BABP) (13).

Along this line of investigation, we reported previously on chicken I-BABP (cI-BABP) (18, 19). Isothermal titration calorimetry measurements supported by NMR titration experiments allowed us to establish a thermodynamic binding model describing two consecutive binding events. At variance with the human protein, a single bound cI-BABP was found to be relatively abundant at a low ligand/protein ratio, indicative of poor cooperativity. Indeed, a previous analysis of all available thermodynamic data for I-BABPs allowed us to place the proteins in an indicative cooperativity scale based on the estimated free energy of coupling (ΔΔG) between the internal binding sites. The two extremes were defined by hI-BABP (maximum cooperativity, ΔΔG = −15.50 kJ·mol−1) and cI-BABP (lowest cooperativity, ΔΔG = −0.87 kJ·mol−1). In the case of cI-BABP, analysis of the energetics of binding and of chemical shift perturbations (19) further indicated that the first binding event triggers a global structural rearrangement associated with a substantial enthalpic contribution (ΔH = −50.3 ± 5 kJ·mol−1). The protein thus appears capable of establishing long-range interactions, although it displays poor energetic coupling between the binding sites. In line with the classical definition of cooperativity (20), we thus proposed that cI-BABP behaves as an allosteric system, making it a promising model for exploration of the determinants of cooperativity.

The goal of the present study was to gain more insight into the structural basis of positive cooperativity in I-BABPs through the comparative analysis of key interactions in proteins with different coupling energies. As a necessary starting point we determined the solution structure of cI-BABP in complex with two molecules of the physiologically prevalent bile acid glycochenodeoxycholic acid (GCDA). The structural details have been analyzed to guide the identification of key residues capable, upon mutation, of turning a low cooperative system into one displaying increased binding efficiency. The mutant analysis has the potential to single out functional interactions more directly than expected on the basis of structural comparisons between homologous proteins displaying a limited, but still significant, variability in amino acid composition. Single and double mutants were produced and ligand titration was monitored by NMR, as it was shown previously that NMR can capture the signature of cooperativity in these systems (11, 19). The double bound wild type and mutant proteins were studied additionally by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to identify long-range communication networks at the basis of cooperativity. The present structural and binding data are discussed in terms of an “extended conformational selection” binding model (21, 22).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Sample Preparation

The expression plasmids for the single (A101S) and double (H99Q/A101S) mutant were obtained from that of wild type chicken I-BABP using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit. Recombinant unlabeled (u-) and 15N,13C-labeled wild type and mutant I-BABPs were expressed as described previously (19). u-GCDA was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. [15N]- and [15N,13C]glycine conjugates of chenodeoxycholic acid were prepared as reported previously (18).

NMR Spectroscopy

NMR samples were prepared in 30 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, containing 0.05% NaN3 and 90:10% H2O:D2O or 99% D2O. A pH value slightly lower than the physiological value was chosen to facilitate the observation of NMR signals. Experiments repeated at pH 7.0 however demonstrated the equivalence of the experimental conditions for the purpose of this work. NMR spectra were acquired at 25 °C with a Bruker Avance III spectrometer operating at 600.13 MHz and equipped with a 5-mm TCI cryoprobe and Z-field gradient.

Samples containing 0.4–0.8 mm [15N,13C]cI-BABP in complex with u-GCDA at a ligand/protein ratio of 4 were typically employed for three-dimensional experiments. The backbone assignment was available (19), whereas the side chain resonance assignment was based on (H)CCH-TOCSY and H(C)CH-TOCSY experiments. A three-dimensional NOESY-1H,15N HSQC and two three-dimensional NOESY-1H,13C HSQC (one in H2O and one in D2O) were recorded to obtain intramolecular NOE-based distance restraints for the protein structure determination in the holoform.

F1/F2-15N,13C-filtered NOESY (mixing time 70 ms) and TOCSY (mixing time 80 ms) experiments were run to filter out the 1H resonances of doubly labeled protein allowing the resonances assignment of ligands in the bound form. Two three-dimensional F1-15N,13C-filtered, F2-13C-separated, F3-13C-edited NOESY-HSQC spectra (optimized for either aliphatic or aromatic residues) were recorded in D2O (mixing time 120 ms) for intermolecular NOE detection. The first transients of F1- 13C-edited, F3- 13C-filtered three-dimensional HMQC-NOESY experiments with mixing times ranging from 0 to 200 ms were acquired as described previously (12).

15N-Enriched-ligand/protein ratios of 0.3, 1, 1.2, 1.5, 2, 2.2, and 4 were employed in HSQC titration experiments on 0.4 mm protein samples (either wild type or mutants). Random samples, at different ligand/protein ratios, were prepared three times; spectra were accumulated under identical conditions, and the error on the measured peak volume was estimated to be on the order of 5%. NMR data were processed with Topspin 2.1 (Bruker) and analyzed with NMRView (23).

Structure Calculation

The structure of the protein-ligand complex was calculated in two steps: (i) determination of the protein conformation based on experimentally derived intramolecular restraints and (ii) data-driven docking of the ligand molecules into the previously calculated protein scaffold. This approach ensures the highest accuracy of the protein structure in the complex while exploiting the better capability of the docking algorithm to search the intermolecular conformational space (24).

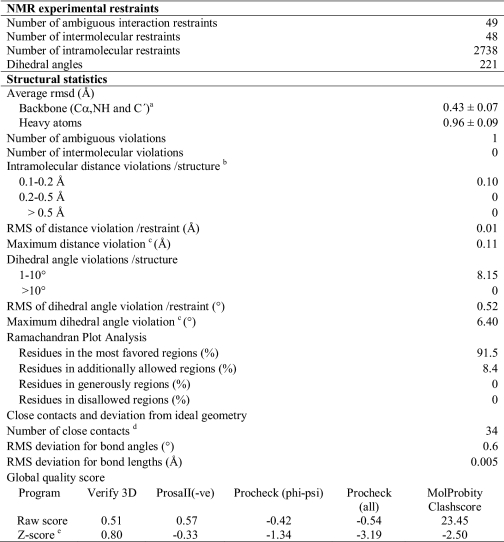

For the first step, the intramolecular restraints were obtained from NOE cross-peak intensities identified in the three-dimensional NOESY-HSQC spectra and from secondary chemical shifts that were translated into the preferred ranges of backbone dihedral angles using the TALOS+ program (25). The structure was then calculated using the torsion angle dynamics program CYANA 2.1 (26). The CANDID module of CYANA (27) was used for automated assignment of the NOE cross-peaks followed by a manual check prior to the final calculations. In summary, the solution structure was determined from 2738 NOE-based distance restraints and 221 chemical shift-based angle restraints. A total of 2959 restraints were used to generate 100 structures, and the 20 conformers with the lowest target function were chosen to represent the solution structure.

For the second step of the structure calculation we used the software HADDOCK 2.1 (28) in combination with crystallography and NMR system (CNS) software (29). The starting protein coordinates were those of the 10 best structures of the final bundle calculated with CYANA. GCDA coordinates were computed with the SMILE program (30) by adding a glycine residue to a chenodeoxycholic acid molecule. The topology and parameter files of the ligands were generated from the PRODRG server (31). The protein was kept fully flexible during docking, although conformational searching was limited due to the presence of the mentioned intramolecular restraints. The ligands were considered as semiflexible segments, and their docking was driven by both computed interaction energies (the force field) and intermolecular restraints. The latter included: (i) ambiguous interaction restraints derived from chemical shift mapping data (19) and isotope-filtered NMR experiments and (ii) unambiguous intermolecular NOEs defined as upper distance limits of 6.0 Å between protein and ligand carbons. Histidines were defined as charged or uncharged on the basis of their chemical shifts at the specified pH (see supplemental Fig. S1). During rigid body docking, 4000 structures were calculated. A total of 400 complex structures selected after rigid body docking were subjected to optimization by fully flexible simulated annealing followed by refinement in explicit water. Electrostatic and van der Waals terms were calculated with an 8.5 Å distance cut-off using the OPLS nonbonded parameters from the parallhdg5.3.pro parameter file (32). The resulting solutions were clustered using the algorithm of Daura (33) with a 0.5 Å cut-off. The structures were divided into 12 clusters, and the best 20 structures were selected for each cluster. According to the HADDOCK score we defined a final bundle of 20 structures.

The protein-ligand contacts were analyzed using the software LIGPLOT (34), and the r.m.s.d. referred to ligand coordinates was calculated after all-atom fitting with PROFIT software. The coordinates and restraints were deposited in the Protein Data Bank (code 2LBA), and the chemical shifts were deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BioMagResBank code 17551).

Bioinformatic Analysis

A phylogenetic tree was obtained according to the following methods. The evolutionary history was inferred using the minimum evolution method (35). The evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method (36) and are in units of the number of amino acid substitutions per site. The minimum evolution tree was searched using the close-neighbor-interchange (CNI) algorithm (37) at a search level of 1. The neighbor-joining algorithm (38) was used to generate the initial tree. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated from the data set (complete deletion option). There were a total of 89 positions in the final data set. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted in MEGA4 (39). Tree comparison was performed taking into account the work of Schaap et al. (40).

MD Simulations

The starting coordinates for the wild type protein were from the calculated NMR structures. The H99Q/A101S mutant protein was modeled by point mutations of the residues using the Mutator plug-in in VMD (41). Both wild type and doubly mutated proteins were simulated in explicit aqueous solution inserted into a cubic box of water molecules, ensuring that the solvent shell would extend for at least 1.2 nm around them. Gromos96, in combination with the simple point charge (SPC) force field, was used for the simulation. Long-range electrostatic interactions were treated with the particle mesh Ewald (PME) method using a grid with a spacing of 0.12 nm (42). The cut-off radius for the Lennard-Jones interactions, as well as for the real part of the PME calculations, was set to 0.9 nm. The LINCS algorithm (43) was used to constrain all bond lengths involving hydrogen atoms, and the time step used was 2 fs. The systems were energy-minimized imposing harmonic position restraints of 1000 kJ mol−1 nm−2 on solute atoms, allowing the equilibration of the solvent without distorting the solution structure. After an energy minimization of the solvent and the solute without harmonic restraints, the temperature was gradually increased from 0 to 300 K in 200 ps of simulation. Each system was finally simulated for 50 ns. All simulations were performed with the GROMACS software package (44). The module g_cluster was used to clusterize the trajectory with an r.m.s.d. cut-off of 0.1 nm. The latter analysis was performed to extract the representative structures of the most populated clusters, that is, the most visited conformations along the entire length of MD simulations. The analysis of structural features was carried out on the representative structures. The large scale motions were investigated by calculating the eigenvectors of the covariance matrix of Cα atoms using the g_covar and g_anaeig modules of GROMACS. The residue-based root mean square fluctuations were calculated by projecting each trajectory on the first eigenvector. The hydrogen bonds formed during the simulations were extracted using the GROMACS program g_hbond.

RESULTS

Identification of a Singly Ligated cI-BABP

cI-BABP was shown able to bind at least two molecules of bile salt. However, previous NMR and thermodynamic data on cI-BABP (19) had predicted a considerable concentration of singly bound protein over a wide range of ligand/protein (L/P) molar ratios, accounting for up to 50% of all protein when 1 < L/P < 2. The structural analysis of the singly ligated species was expected to be very informative for understanding the sequence of binding events. Therefore, we performed an analysis of ligand resonances at various L/P values in order to identify the conditions suitable for such a characterization. At L/P = 2 (supplemental Fig. S2) an intense signal in the two-dimensional F1/F2-15N,13C-filtered NOESY experiment of a [15N,13C]cI-BABP·u-GCDA sample, connecting the resonances at 0.42 and 0.57 ppm, was assigned to an exchange cross-peak between C18 methyl groups of unbound and singly bound GCDA. This assignment was confirmed by the fact that on increasing ligand concentration this cross-peak disappeared. Complementary NMR experiments, namely F1-edited, F3-filtered, three-dimensional HMQC-NOESY (12) with mixing times ranging from 0 to 200 ms, were performed (supplemental Fig. S3), confirming the assignments of all the methyl groups of the doubly and singly ligated species. It was thus possible unambiguously to identify signals corresponding to ligand in the singly bound protein; however, the complexity of the spectra prevented a rigorous structural analysis, and we focused the study on the double bound species only.

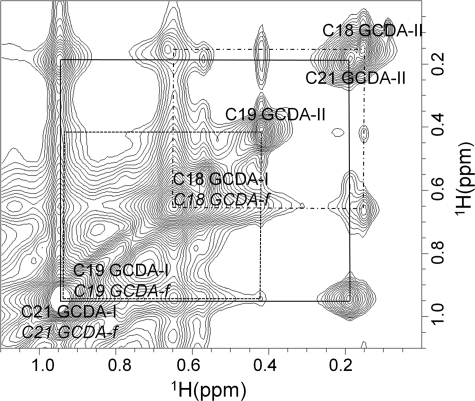

Identification of Intermolecular Restraints for the Double Bound cI-BABP

cI-BABP forms a ternary complex with two ligand molecules (19). The major difficulty in the structure determination of the complex consists in the assignment of the two identically bound molecules of bile acids. The chemical shift dispersion of GCDA protons is very poor, but the presence of the three methyl groups, C18, C19, and C21 (see Scheme 1 for numbering), which appear in the unbound bile salt as two high intensity singlets (reported chemical shifts for C18 and C19 are 0.67 and 0.93 ppm, respectively) and as a doublet (C21, 0.95ppm) resonating at high fields (45), constituted a good entry point for the assignment of the bound molecules. Two-dimensional F1/F2-15N,13C-filtered NOESY experiments performed on a [15N,13C]cI-BABP·u-GCDA sample with L/P = 4 were used to filter out 1H protein signals, allowing the observation of the GCDA resonances. Three high field resonating signals could be distinguished at 0.15, 0.19, and 0.42 ppm (Fig. 1). These resonances exhibited NOESY exchange peaks with intense signals at the chemical shift of free GCDA (in excess in the sample) and were assigned to the methyl groups of one bound GCDA molecule (hereby called GCDA-II). Specifically, the identification of C19 and C21, showing almost superimposed signals in the free ligand, was possible on the basis of a double filtered TOCSY experiment of the complex, where only the C21 methyl groups can display cross-peaks. If two molecules of GCDA are bound to cI-BABP, then a total of six different methyl signals are expected in this region in addition to those of the free GCDA. The resonances of the ligand bound to site I (GCDA-I) resulted coincident with those of free GCDA based on the following observations: (i) The 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of u-cI-BABP·[15N]GCDA showed a single averaged resonance at 7.89 ppm for the amide group of free GCDA and GCDA-I, and (ii) the HACA and HNCA spectra of u-cI-BABP·[15N,13C]GCDA exhibited a single Cα chemical shift for the free and bound (to site I) ligand.

SCHEME 1.

Glycochenodeoxycholic acid structure, showing numbering of carbon atoms.

FIGURE 1.

Identification of ligand NMR resonances. High field region of the two-dimensional F1/F2-15N,13C-filtered NOESY spectrum (mixing time 70 ms) of an 0.4 mm sample of cI-BABP in complex with GCDA at L/P = 4 is shown. The sample was dissolved in 30 mm phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, at 298 K. The assignment of the methyl groups of GCDA molecules is reported on the spectrum. GCDA-I, GCDA-II, and GCDA-f indicate the ligand bound to site I, the ligand bound to site II, and the ligand in free form, respectively. C18, C19, and C21 refer to the three methyl groups of GCDA (see Scheme 1 for atom numbering). Connections of NOESY exchange cross-peaks are indicated by lines.

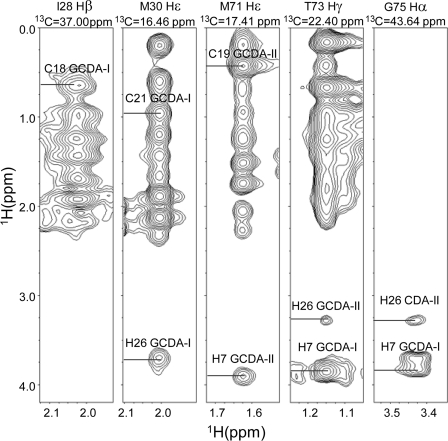

Few additional ligand resonances beyond those of the methyl groups were sufficiently resolved at L/P = 4 and could be unambiguously assigned, including the signals of H-7 (GCDA-I 3.85 ppm, GCDA-II 3.89 ppm) and H-3 of GCDA-I (3.46 ppm) as well as H-26 of both bound molecules (3.78 and 3.27 ppm for GCDA-I and GCDA-II, respectively). These assignments allowed the identification of 35 intermolecular NOEs (Fig. 2) used in the first run of structure calculations of the complex.

FIGURE 2.

Identification of intermolecular distance restraints. Representative F1–F3 slices are shown of the three-dimensional F1-15N,13C-filtered, F2-13C-separated, F3-13C-edited NOESY-HSQC spectrum of an 0.8 mm sample of cI-BABP in complex with GCDA at L/P = 4. The strips corresponding to 13C chemical shifts of Ile-28-Cβ, Met-30-Cϵ, Met-71-Cϵ, Thr-73-Cγ, and Gly-75-Cα are shown from left to right.

Structure Calculation of the Ternary Complex between cI-BABP and Two Molecules of GCDA

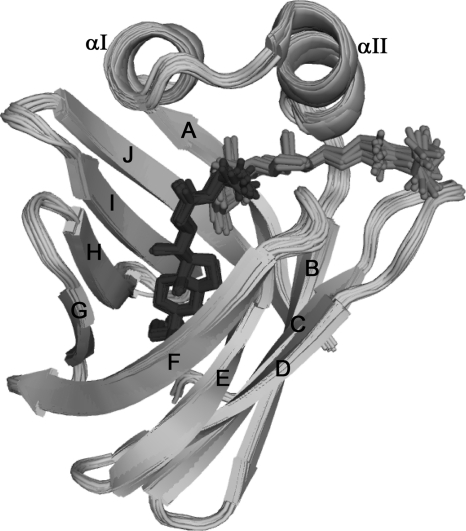

First, the protein-only coordinates of the fully complexed species were determined on the basis of intramolecular experimental restraints. The computed family of conformers resulted of high quality r.m.s.d. = 0.49 ± 0.08 Å for backbone atoms and 1.07 ± 0.08 Å for all heavy atoms (86% of the backbone angles in the most favored region and 14% in additionally favored regions of the Ramachandran plot with a G-factor for backbone/all dihedral angles of −0.62/−0.72). Subsequently, the ligand poses and conformations were determined with a data-driven docking approach (28, 46) based on the calculated structures. To identify the interaction surface, the average HN and N chemical shift changes between the free and bound states (19) were analyzed. Resonances with significant chemical shift perturbations, deviating by more than twice the standard deviation from the mean chemical shift perturbation, included residues 53, 57–59, 97, and 98 residing in the CD loop and β-strand H. These residues were treated as ambiguous interaction restraints. Intermolecular NOEs, derived from edited-filtered experiments, were introduced as ambiguous interaction restraints in the first HADDOCK run. Subsequent rounds of the docking procedure coupled with spectral analysis led to the identification of 48 unambiguous restraints between the ligands and the protein from which the structure of the complex was derived. A complete list of ambiguous and unambiguous restraints is given in supplemental Table S1. The 20 lowest energy structures in the best energy score cluster were retained. The structural statistics of the cluster with the best average HADDOCK score are presented in Table 1, and Fig. 3 displays the HADDOCK model that best represents the structure of the complex. The 20 best structures in the selected cluster have average r.m.s.d. values of 0.43 ± 0.07 and 0.96 ± 0.09 Å for the backbone and all heavy atoms, respectively. The average r.m.s.d. values of the ligands were 1.15 Å for GCDA-I and 0.72 Å for GCDA-II.

TABLE 1.

Structural statistics of the 20 lowest energy structures in the HADDOCK lowest energy cluster

a Root mean square deviations of atomic coordinates were calculated over residues 1–127 using MOLMOL (55).

b Calculated for all restraints for the given residues, using sum over r−6.

c Largest restraint violation among all reported structures.

d Within 1.6 Å for hydrogen atoms and 2.2 Å for heavy atoms.

e Z-score computed using protein structure validation server (PSVS) (56).

FIGURE 3.

NMR structure of cI-BABP in complex with two glycochenodeoxycholate molecules. This is a superposition of the 20 lowest energy structures belonging to the best HADDOCK cluster. The protein backbone is shown in schematic representation, and the secondary structure elements are labeled. GCDA-I and GCDA-II are represented as dark gray and black sticks, respectively.

Structural Correlates of Cooperativity: Analysis of I-BABP Subfamily

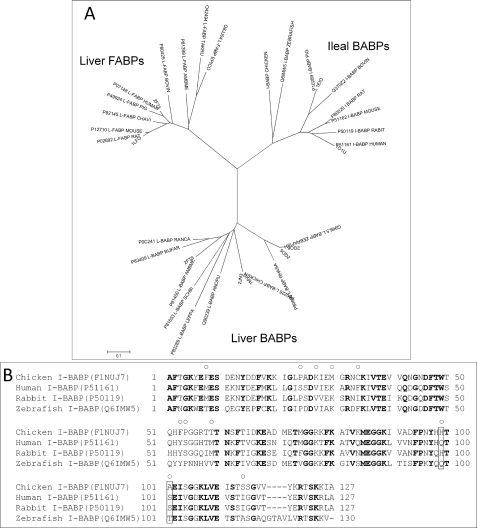

A phylogenetic analysis of the FABP family was performed as the starting point for a comparative functional analysis. The protein sequences closest to cI-BABP cluster in three well defined groups corresponding to liver FABPs, liver BABPs, and ileal BABPs (Fig. 4A). Thus the investigation of functional amino acids in cI-BABP was concentrated only on its closest relatives, the I-BABPs, including both mammalian and non-mammalian species.

FIGURE 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of the I-BABP subfamily of FABPs. A, evolutionary relationships within the FABP family. The optimal tree with the sum of branch length = 5.11196057 is shown. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. B, sequence alignment of chicken I-BABP with human, rabbit, and zebrafish I-BABPs. Conserved residues are highlighted in bold. Residues presenting nonconservative mutations in the four proteins pointing toward the ligand-binding cavity are indicated with a circle. Positions 99 and 101 are framed in black. UNIPROT ID codes are shown in parentheses.

Within the family of I-BABPs, only a few members have been studied in terms of ligand interaction properties. Some thermodynamic binding data have been presented in the literature for human (9, 11), rabbit (17), zebrafish (13), and chicken ileal BABPs (19), which allowed us to place these proteins in an indicative cooperativity scale as mentioned in the Introduction. Because it was expected that the most and the least cooperative proteins would present the largest functional differences, we focused on the structural comparison between cI-BABP (low cooperativity) and hI-BABP (high cooperativity). For the latter, only a single bound complex has been reported (Protein Data Bank code: 1O1V), as it was determined at temperatures at which one of the two ligands could not be observed because of exchange broadening of the NMR signals (47, 48). However, the protein scaffold can be predicted to represent the protein bound to two ligands with good approximation.

All of the available structural and binding data were used to point out the structural correlates of cooperativity according to the following approach. To identify functional residues, all the nonconserved amino acids pointing into the internal protein cavity were selected and mapped onto the sequence alignment plot, including the other homologous proteins (Fig. 4B). To point out the relevant interactions, pairs of amino acids were analyzed. The 11 nonconserved residues (residues 8, 24, 27, 30, 34, 53, 54, 59, 99, 101, and 114) within the protein cavity may give rise to 55 possible pairs. Among these pairs only eight were made of residues exhibiting a reciprocal average distance shorter than 4 Å and six (residues 53/54, 53/34, 54/34, 24/27, 27/30, and 30/34) were found in both human and chicken proteins (Table 2). Only the residue pairs 54/34 and 24/27 displayed changes in the amino acid type that correlate with the cooperativity scale; however, the nature of the interactions formed in human and chicken proteins is conserved. The two pairs, residues 54/27 and 99/101, were present only in the human protein, with only the 99/101 pair displaying changes in amino acid type that correlated with cooperativity.

TABLE 2.

Pairs of nonconserved residues exhibiting distances shorter than 4 Å in chicken and human I-BABPs

| Residue pair | cI-BABP residues | zI-BABP residues | rI-BABP residues | hI-BABP residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 53/54 | Phe/Pro | Tyr/Pro | Tyr/Ser | Tyr/Ser |

| 53/34 | Phe/Cys | Tyr/Phe | Tyr/Ile | Tyr/Phe |

| 54/34 | Pro/Cys | Pro/Phe | Ser/Ile | Ser/Phe |

| 24/27 | Pro/Lys | Pro/Val | Pro/Val | Ser/Val |

| 27/30 | Lys/Met | Val/Lys | Val/Lys | Val/Lys |

| 30/34 | Met/Cys | Lys/Phe | Lys/Ile | Lys/Phe |

| 54/27a | Pro/Lys | Pro/Val | Ser/Val | Ser/Val |

| 99/10a | His/Ala | Gln/Thr | His/Ser | Gln/Ser |

| ΔΔGb (kJ·mol−1) | −0.87 | −4.55 | −6.96 | -15.50 |

a Residue pair displaying interactions only in human I-BABP.

b The ΔΔG values are the upper limits of the free energy coupling between the two binding events and provide a measure of cooperativity (19).

Mutant Analysis

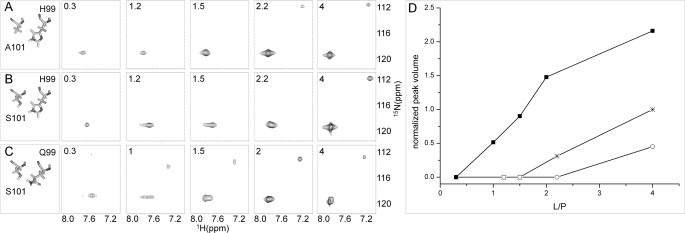

The ultimate confirmation of the correct identification of functionally relevant amino acids can be obtained by introducing function in a nonfunctional system. This approach provides in principle more definitive results compared with a loss-of-function experimental scheme. We therefore set out to verify the role of the above identified amino acid pair 99/101 in establishing efficient binding cooperativity, with the optimal interaction represented by the couple Q/S. For this purpose, two mutants were designed and engineered: the single mutant A101S cI-BABP (same amino acids as in rabbit I-BABP) and the double mutant H99Q/A101S cI-BABP (same amino acids as in hI-BABP) to reproduce an intermediate and high cooperativity system, respectively. The stability and fold of the protein mutants produced were verified (supplemental Fig. S4). The proteins were titrated with increasing amounts of [15N]GCDA, and the recorded 1H,15N HSQC spectra were employed to monitor the binding events. Here we exploited the already assessed power of NMR to gain site-specific binding information and detect positive cooperativity in these systems (11, 15, 19). Titration experiments performed on the wild type protein show the appearance of the signal of GCDA-II (δ(1H) = 7.18 ppm, δ(15N) = 112.0 ppm) only at L/P > 2, indicative of low cooperativity (Fig. 5). For the A101S mutant the corresponding ligand signal is also not visible before L/P = 4, suggesting that other concurring amino acids may be involved in establishing the intermediate energetic coupling value reported for rI-BABP. However, in the case of the double mutant H99Q/A101S, the resonances corresponding to both bound ligands are already present at low ligand concentrations (L/P ≥ 1), an indication of acquired positive binding cooperativity. The altered binding site occupancy in the mutant proteins is shown quantitatively in Fig. 5D, reporting the integrated volumes of the peak of GCDA-II along the titrations. The stepwise occupancy of binding site 1 could not be monitored because the resonance of GCDA-I is overlapped with that of the free ligand.

FIGURE 5.

NMR ligand-observed titration experiments. 1H,15N HSQC spectra were recorded during the titration of [15N]GCDA into unlabeled cI-BABP wild type (A), mutant A101S (B), and mutant H99Q/A101S (C). The cross-peak resonating at about 120 ppm in the nitrogen dimension corresponds to the overlapped peaks of GCDA bound to site I and in the unbound form, and the peak appearing at around 112 ppm (15N) is attributed to GCDA bound to site II. The GCDA/protein molar ratios are indicated on each panel (A–C). A stick representation of the wild type and mutated residues is shown corresponding to each titration. D, line scatter plot reporting the volume of peaks attributed to GCDA-II versus the ligand/protein molar ratio (L/P) for titrations of wild type (*), A101S (○), and H99Q/A101S (■).

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

To gain a deeper understanding of the structural and dynamic basis of cooperativity in the systems under study, two 50-ns MD simulation runs were collected for the wild type and double mutant complexes. The calculated NMR structure provided the starting coordinates for wild type cI-BABP as well as for the mutant protein, with the simple substitution of the mutated amino acids. The analysis of the conformations sampled by the systems was performed by calculating the time evolution of the atom-positional r.m.s.d. from the initial structures for each protein. The r.m.s.d. values stabilized after 10 ns at around 0.15 nm from the initial structure in the case of the wild type protein and after 15 ns at around 0.2 nm in the case of the mutant (supplemental Fig. S5), showing the substantial stability of the complexes under the simulation conditions. The overall conservation of structural properties was also apparent in the secondary structure analysis. No major variation could be detected, indicating the absence of large conformational changes or folding-unfolding events. The position of the ligands inside the binding cavity was checked continuously during the MD simulations as a further validation of the entire procedure. Indeed, the spatial restraints between the protein and the ligands, observed in the NMR experiments, were maintained (not violated) during the simulations.

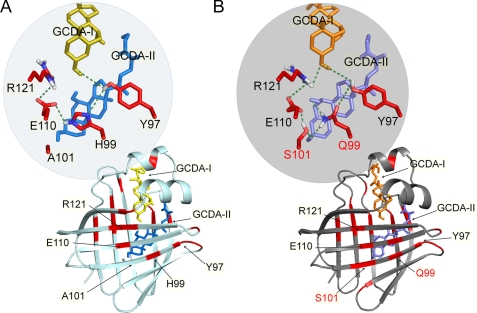

A detailed inspection of hydrogen-bonding patterns along the trajectories highlighted interesting, distinctive features between the wild type and mutant proteins (supplemental Figs. S6 and S7). In the former, a “lower region” H-bond network was established and maintained throughout the simulation involving Y97-Hη and H99-Nδ1, H99-Hϵ2 and E110-Oϵ1,ϵ2, and E110-Oϵ1ϵ2 and R121-Hϵ. In this protein region only Tyr-97 is connected to GCDA-I, whereas no residue binds GCDA-II through the H-bonds (Fig. 6A). A very different pattern is found in the double mutant (Fig. 6B). During the simulation the hydroxyl group of Ser-101 forms hydrophilic contacts with Glu-110-Oϵ1,ϵ2, Gln-99-Hϵ2, and OH-3 of GCDA-II. The presence of Ser-101 also decreases the probability of the formation of an H-bond between Gln-99 and Glu-110. Additional H-bonds are formed between Gln-99 and the OH groups of GCDA-II and between OH-3 of GCDA-I and both Tyr-97 and Arg-121. Ser-101 and Gln-99 thus provide an anchor region for GCDA-II in the lower part of the cavity that is not present in the wild type. A comparison of Fig. 6, A and B, clearly shows that only in the double mutant is a continuous pattern of hydrophilic interactions established throughout the protein, involving the two bound ligands in the communications pathway.

FIGURE 6.

Hydrogen-bonding patterns in MD representative structures. The residues displaying the most relevant side chain-side chain H-bonds are highlighted in red on the cartoon structures of wild type (A) and H99Q/A101S (B) cI-BABP·GCDA complexes. In the respective insets, the hydrogen bonds conserved throughout the 50-ms MD simulations are shown (dotted green lines) connecting residues (sticks) in the ligand binding regions and close to the mutation sites. Residues highlighted in the inset are labeled, and the mutated residues are labeled in red.

A further analysis of MD trajectories was performed through essential dynamics to identify the relevant, low frequency, concerted motions of groups of residues (49), which can be appreciated by residue-based root mean square fluctuations (supplemental Fig. S8, RMSF) projected along the directions of the eigenvectors. A significant difference between both holosystems was observed; in the wild type protein a concerted fluctuation is apparent only for the CD loop and, to a lesser extent, for the αI-αII and EF loops, both being in contact with the carboxyl tails of the ligands in the NMR structure. On the contrary, for the double mutant, correlated motions are transmitted throughout the protein segments defining the protein open end, namely the αI-αII, CD, GH, and IJ loops. Additional concerted motions are present at the closed end of the protein at the level of the BC loop.

DISCUSSION

Structural Comparison with Related Protein Complexes

High resolution structures of BABP-bile salt complexes are still very few. The only ternary complex of an I-BABP available for comparative analysis of the determined structure herein is that of zI-BABP bound to two cholate molecules (Protein Data Bank code: 3EM0) (13). Superposition of the structures of zI-BABP and cI-BABP yielded r.m.s.d. values of 1.72 Å and indicated substantial differences localized to helix-II, loops EF and IJ, all defining the protein open end. The binding sites appeared to be almost coincident, with the internal ligand essentially superimposable after the protein coordinates were matched, whereas the ligands in site I were twisted reciprocally by ∼90° around the longest molecular axis.

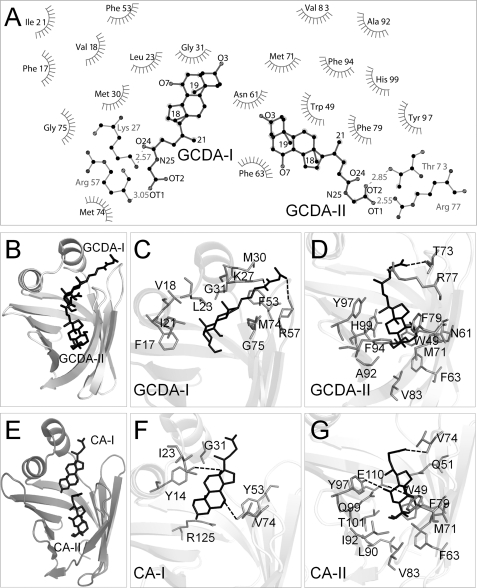

The binding cavities of the two proteins were analyzed with LIGPLOT, a software that generates two-dimensional schematic diagrams of protein-ligand interactions, highlighting both hydrophilic and hydrophobic contacts. A diagram representing the interactions of cI-BABP with two GCDA molecules is shown in Fig. 7. In the zebrafish holoprotein the bound ligands are cholate molecules (CA), presenting shorter side chains compared with GCDA as well as an additional hydroxyl group in position 12. In the two proteins, the internal ligand establishes interactions via its carboxylate group with the EF loop (residues Thr-73 and Arg-77 in chicken and residue Val-74 in zebrafish protein). Additional hydrophilic interactions are established in the zebrafish protein between OH-7 and Glu-110 and OH-12 and Tyr-97. The hydrophobic interactions of the internal ligand are similar in the two proteins, although a more extended hydrophobic environment is present in cI-BABP, attendant with the increased hydrophobicity of GCDA compared with CA.

FIGURE 7.

Comparative analysis of protein-bile salts interactions. A, LIGPLOT diagram of interactions observed between cI-BABP and GCDA-I (left) and GCDA-II (right). Hydrogen bonds are dashed gray lines with distances indicated in Å. Residues in hydrophobic contact with the ligands are represented by semicircles with radiating spokes. B, full view of the structure of cI-BABP·GCDA. C, enlarged view of binding site I showing the residues involved in hydrophilic and hydrophobic contacts. D, enlarged view of binding site II. E, full view of the structure of zI-BABP·CA. F and G, enlarged views of binding sites I and II, respectively.

The more external ligand, GCDA-I, in chicken protein, makes two H-bonds between its C24 carbonyl group and the side chain of Lys-27, its terminal carboxylate and the backbone amide of Arg-57. In zebrafish, H-bonds are established between OH-7 and Tyr-53 and OH-12 and Tyr-14. Therefore, the main difference between the two proteins is that the ligand hydrophilic anchoring moiety is constituted by the sterol rings in zI-BABP and by the linear chain in cI-BABP. Hydrophobic contacts with the external cholate in zI-BABP appear more limited compared with cI-BABP.

In summary, the binding site geometries of the two bile salt complexes appear relatively similar. The differences, however, relate to the patterns of hydrophilic interactions involving the more externally bound ligand as well as to an increased number of hydrophobic contacts observed for the chicken protein.

Structure-Cooperativity Relationship and Mechanistic Implications

In I-BABPs, residues 99 and 101 are buried within the protein cavity. The pair 99/101, with the exception of the chicken protein, is always constituted by polar amino acids: Gln/Thr (zI-BABP), His/Ser (rI-BABP), and Gln/Ser (hI-BABP). It is interesting to note that in the human protein, five residues (Tyr-97, Gln-99, Ser-101, Glu-110, and Arg-121) constitute a connected platform where H-bonds are formed between the pairs 97/99, 99/101, and 110/121. It is possible that residues Ser-101 and Tyr-97 keep Gln-99 in a favorable position to produce a polar cavity capable of anchoring one ligand. In the chicken protein, which lacks a polar residue at position 101, His-99 establishes a very stable H-bond with Tyr-97 and Glu-110, which in turn is connected with Arg-121 through an H-bond. Thus a very rigid H-bond pattern is formed, possibly disfavoring the conformational flexibility needed for an efficient coupling between the binding subcavities. The nature and orientation of residue 99 may thus have an effect on the binding mechanism. Indeed, calorimetry data coupled to mutation experiments reported for the human protein indicate that the mutant Q99A exhibits a strong decrease in cooperativity for binding to GCDA (9).

The functional relevance of the amino acid couple 99/101 is supported by both the structural and dynamic information derived from MD simulations. A comparison between representative structures of the computed trajectories of the wild type and H99Q/A101S proteins highlights the fact that in the double mutant a rearranged conformational state is stabilized (supplemental Fig. S9) displaying a closure of the open end that can be ascribed to a positional change of the CD, GH, and IJ loops. Importantly, in this structure the mutated residues allow an extension of the H-bond hyper-network, increasing the communication between binding sites (Fig. 6). This notion supports a long-range effect on ligand binding instead of a local affinity change. In addition to these structural (mainly enthalpic) contributions to binding affinity, differential protein flexibility may also play a role in ligand recognition (entropic contribution). To investigate this possibility, essential dynamics was carried out on the MD trajectories of the complexes. This analysis indicated that in the wild type protein the CD loop undergoes the largest fluctuation, with correlated motions substantially confined to loops that are in contact with the carboxyl tails of the two ligands (supplemental Fig. S8). The double mutant complex instead shows fluctuations of minor amplitude, however, spanning a larger protein domain, extending beyond residues in contact with the ligands, and defined by loops in the so-called portal area. It is interesting to note that these loops connect strands involved in the major H-bond network, whereas the EF loop, connecting strands E and F, is excluded from the main correlated motions. A functional consequence of the described equilibrium fluctuations could be the stabilization of a “closed” structural architecture characterized by shorter average distances between the interhelix and CD loops.

Altogether, our observations establish the involvement of specific amino acids in the reorganization of the protein structure that occurs upon ligand binding. In our previous work (19) we described cI-BABP as allosterically activated by the first ligand binding event. Indeed, NMR chemical shifts of the unbound and fully complexed proteins revealed sensitive indicators of atom positional changes, which are presumably small but distributed over the entire protein, suggestive of a global structural rearrangement. It was proposed previously that, in BABPs, allostery derives from conformational selection (50–52), and it was further hypothesized that positive cooperativity in hI-BABP may be related to a slow conformational change of the protein, occurring after the second binding step (10). The acquisition observed herein of an extended H-bond network in the double mutant cI-BABP represents a final binding event that could be described according to an “indues fit” model.

In summary, the cooperative binding mechanism in ileal BABPs requires the presence of a small number of latch residues located in the inner protein cavity that “click in” to their final conformation upon ligand binding and stabilize an extended communication network necessary for establishing energetic coupling between binding sites. The available data fit very well with the proposed extended conformational selection model (21), described as an initial conformational selection where ligands bind one of the several fluctuating protein conformers and induce a subsequent conformational rearrangement of the protein. Binding cooperativity can be particularly important for the ileal BABP family as it can provide ability to function as an on-off switch by responding to changes in bile acids concentration and protecting the cell against their toxic effects (53, 54). Interestingly, I-BABPs have been shown to display different degrees of cooperativity, which may correlate with species-specific differences in the bile acid pool size. We have demonstrated that key interactions established by amino acids specific to the human protein can be introduced artificially in cI-BABP to gain energetic coupling between binding sites. The determined correlates of cooperativity provide a structural perspective on the functional differences among BABPs and may be of value for the rational design of synthetic drugs aimed at controlling bile acid circulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Simona Tomaselli for help with structure calculations. We thank the European Community (EU-NMR Contract RII3-026145) for access to the HWB-NMR facility at Birmingham, United Kingdom; the Consorzio Interuniversitario di Risonanze Magnetiche di Metalloproteine Paramagnetiche (CIRMMP) for access to high field spectrometers; the e-NMR project (a European FP7 e-Infrastructure grant, Contract 213010), supported by the national GRID Initiatives of Italy, Germany, and the Dutch BiG Grid project (Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research) for the use of Web server facilities; and the University of Verona and the Cariverona Foundation for financial support for the acquisition of an NMR spectrometer and cryoprobe.

This work was supported by the Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca (Fondo per gli Investimenti della Ricerca di Base, Futuro in Ricerca 2008, Grant RBFR08R7OU).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S9 and Table S1.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 2LBA) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- BABP

- bile acid-binding protein

- I-BABP

- ileal bile acid-binding protein

- cI-

- hI-, rI-, and zI-BABP, chicken, human, rabbit, and zebrafish I-BABP, respectively

- FABP

- fatty acid-binding protein

- GCDA

- glycochenodeoxycholic acid

- MD

- molecular dynamics

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation

- L/P

- ligand/protein

- u-

- unlabeled

- CA

- cholic acid

- CDA

- chenodeoxycholic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Veerkamp J. H., Maatman R. G. (1995) Prog. Lipid Res. 34, 17–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Houten S. M. (2006) Cell Metab. 4, 423–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Houten S. M., Watanabe M., Auwerx J. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 1419–1425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Argmann C. A., Houten S. M., Champy M. F., Auwerx J. (2006) Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2006, chapter 29: Unit 29B.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lew J. L., Zhao A., Yu J., Huang L., De Pedro N., Peláez F., Wright S. D., Cui J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 8856–8861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hamilton J. A. (2004) Prog. Lipid Res. 43, 177–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tochtrop G. P., Bruns J. L., Tang C., Covey D. F., Cistola D. P. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 11561–11567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tochtrop G. P., DeKoster G. T., Covey D. F., Cistola D. P. (2004) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 11024–11029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Toke O., Monsey J. D., DeKoster G. T., Tochtrop G. P., Tang C., Cistola D. P. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 727–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Toke O., Monsey J. D., Cistola D. P. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 5427–5436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tochtrop G. P., Richter K., Tang C., Toner J. J., Covey D. F., Cistola D. P. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 1847–1852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eliseo T., Ragona L., Catalano M., Assfalg M., Paci M., Zetta L., Molinari H., Cicero D. O. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 12557–12567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Capaldi S., Saccomani G., Fessas D., Signorelli M., Perduca M., Monaco H. L. (2009) J. Mol. Biol. 385, 99–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kouvatsos N., Meldrum J. K., Searle M. S., Thomas N. R. (2006) Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 44, 4623–4625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pedò M., D'Onofrio M., Ferranti P., Molinari H., Assfalg M. (2009) Proteins 77, 718–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smock R. G., Rivoire O., Russ W. P., Swain J. F., Leibler S., Ranganathan R., Gierasch L. M. (2010) Mol. Syst. Biol. 6, 414–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kouvatsos N., Thurston V., Ball K., Oldham N. J., Thomas N. R., Searle M. S. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 371, 1365–1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guariento M., Raimondo D., Assfalg M., Zanzoni S., Pesente P., Ragona L., Tramontano A., Molinari H. (2008) Proteins 70, 462–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guariento M., Assfalg M., Zanzoni S., Fessas D., Longhi R., Molinari H. (2010) Biochem. J. 425, 413–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cui Q., Karplus M. (2008) Protein Sci. 17, 1295–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Csermely P., Palotai R., Nussinov R. (2010) Trends Biochem. Sci. 35, 539–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reichheld S. E., Yu Z., Davidson A. R. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 22263–22268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johnson B. A. (2004) Methods Mol. Biol. 278, 313–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tomaselli S., Zanzoni S., Ragona L., Gianolio E., Aime S., Assfalg M., Molinari H. (2008) J. Med. Chem. 51, 6782–6792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shen Y., Delaglio F., Cornilescu G., Bax A. (2009) J. Biomol. NMR 44, 213–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Güntert P. (2004) Methods Mol. Biol. 278, 353–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Herrmann T., Güntert P., Wüthrich K. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 319, 209–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dominguez C., Boelens R., Bonvin A. M. (2003) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 1731–1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brünger A. T., Adams P. D., Clore G. M., DeLano W. L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J. S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N. S., Read R. J., Rice L. M., Simonson T., Warren G. L. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54, 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Eufri D., Sironi A. (1989) J. Mol. Graph. 7, 165–169, 158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schüttelkopf A. W., van Aalten D. M. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 1355–1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Linge J. P., Williams M. A., Spronk C. A., Bonvin A. M., Nilges M. (2003) Proteins 50, 496–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Daura X., Antes I., van Gunsteren W. F., Thiel W., Mark A. E. (1999) Proteins 36, 542–555 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wallace A. C., Laskowski R. A., Thornton J. M. (1995) Protein Eng. 8, 127–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rzhetsky A., Nei M. (1992) Mol. Biol. Evol. 9, 945–967 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zuckerkandl E., Pauling L. (1965) Evolving Genes and Proteins (Bryson V., Vogel H. J. eds) pp. 97–116, Academic Press, New York: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nei M., Kumar S. (2000) Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics, Oxford University Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 38. Saitou N., Nei M. (1987) Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. (2007) Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1596–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schaap F. G., van der Vusse G. J., Glatz J. F. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 239, 69–77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. (1996) J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38, 27–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Darden T. A., Pedersen L. G. (1993) Environ. Health Perspect. 101, 410–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chau C. D., Sevink G. J., Fraaije J. G. (2011) Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 83, 016701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Van Der Spoel D., Lindahl E., Hess B., Groenhof G., Mark A. E., Berendsen H. J. (2005) J. Comp. Chem. 26, 1701–1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ijare O. B., Somashekar B. S., Jadegoud Y., Nagana Gowda G. A. (2005) Lipids 40, 1031–1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. van Dijk A. D., Bonvin A. M. (2006) Bioinformatics 22, 2340–2347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kramer W., Sauber K., Baringhaus K. H., Kurz M., Stengelin S., Lange G., Corsiero D., Girbig F., Konig W., Weyland C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 7291–7301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kurz M., Brachvogel V., Matter H., Stengelin S., Thuring H., Kramer W. (2003) Proteins 50, 312–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nunez S., Wing C., Antoniou D., Schramm V. L., Schwartz S. D. (2006) J. Phys. Chem. A 110, 463–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cogliati C., Ragona L., D'Onofrio M., Gunther U., Whittaker S., Ludwig C., Tomaselli S., Assfalg M., Molinari H. (2010) Chemistry 16, 11300–11310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ayers S. D., Nedrow K. L., Gillilan R. E., Noy N. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 6744–6752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ragona L., Catalano M., Luppi M., Cicero D., Eliseo T., Foote J., Fogolari F., Zetta L., Molinari H. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 9697–9709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Elkin R. G., Wood K. V., Hagey L. R. (1990) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 96, 157–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hagey L. R., Schteingart C. D., Ton-Nu H. T., Hofmann A. F. (1994) J. Lipid Res. 35, 2041–2048 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Koradi R., Billeter M., Wuthrich K. (1996) J. Mol. Graph. 14, 51- 55, 29–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bhattacharya A., Tejero R., Montelione G. T. (2007) Proteins 66, 778–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.