Background: Some glycosylation-deficient patients do not make enough mannose-1-P from mannose-6-P. Preventing mannose-6-P catabolism might improve glycosylation in cells and patients.

Results: Inhibitors of mannose-6-P catabolism direct more mannose toward N-glycosylation in many cell types.

Conclusion: Increasing exogenous mannose and blocking mannose-6-P catabolism can improve glycosylation in some glycosylation-deficient cells.

Significance: Increasing activated mannose flux might benefit some glycosylation-deficient patients.

Keywords: Carbohydrate Metabolism, Genetic Diseases, Glycobiology, Glycoprotein, Glycosylation, CDG-Ia, Mannose, Metabolic Flux, Phosphomannomutase, Phosphomannose Isomerase

Abstract

Congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) are rare genetic disorders due to impaired glycosylation. The patients with subtypes CDG-Ia and CDG-Ib have mutations in the genes encoding phosphomannomutase 2 (PMM2) and phosphomannose isomerase (MPI or PMI), respectively. PMM2 (mannose 6-phosphate → mannose 1-phosphate) and MPI (mannose 6-phosphate ⇔ fructose 6-phosphate) deficiencies reduce the metabolic flux of mannose 6-phosphate (Man-6-P) into glycosylation, resulting in unoccupied N-glycosylation sites. Both PMM2 and MPI compete for the same substrate, Man-6-P. Daily mannose doses reverse most of the symptoms of MPI-deficient CDG-Ib patients. However, CDG-Ia patients do not benefit from mannose supplementation because >95% Man-6-P is catabolized by MPI. We hypothesized that inhibiting MPI enzymatic activity would provide more Man-6-P for glycosylation and possibly benefit CDG-Ia patients with residual PMM2 activity. Here we show that MLS0315771, a potent MPI inhibitor from the benzoisothiazolone series, diverts Man-6-P toward glycosylation in various cell lines including fibroblasts from CDG-Ia patients and improves N-glycosylation. Finally, we show that MLS0315771 increases mannose metabolic flux toward glycosylation in zebrafish embryos.

Introduction

Congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG)2 are genetic disorders resulting from abnormal glycosylation. CDG-Ia is caused by mutations in PMM2 (1) with >800 reported cases with hypomorphic mutations showing 0.1–30% residual PMM2 activity (2). Patients suffer a range of multi-organ symptoms, including coagulopathy, hypotonia, cardiomyopathy, hepatointestinal symptoms, and psychomotor and developmental delays (3). CDG-Ia has a mortality rate of about 20% in the early years (3). There is no therapy currently available for CDG-Ia patients.

Mannose is phosphorylated by hexokinase to Man-6-P, which is converted to Man-1-P by PMM2. Man-6-P is generated by phosphorylation of mannose using hexokinase or via phosphomannose isomerase (MPI or PMI) from fructose 6-phosphate (Fru-6-P), which is the major pathway (Scheme 1).

Deficiency of either PMM2 or MPI results in unoccupied N-glycosylation sites on glycoproteins (4). Heterozygous parents are asymptomatic in both disorders. CDG-Ib patients can be treated with dietary mannose supplements; however, CDG-Ia patients do not respond to mannose therapy. PMM2 competes with MPI for the common substrate, Man-6-P, the majority of which is catabolized by MPI, leaving only a very small proportion for glycosylation (5). We hypothesized that inhibition of MPI would increase Man-6-P toward glycosylation via residual PMM2 activity in CDG-Ia patients. Consequently, MPI inhibition combined with mannose supplementation might help normalize N-glycosylation and improve CDG-Ia pathology.

Previously described MPI inhibitors, such as erythrose 4-phosphate and arabinose 5-phosphate, are cell-impermeable, and therefore, not useful for in vivo studies (6). We recently reported the optimization of a series of benzoisothiazolone derivatives that are potent, cell-permeable MPI inhibitors (7). Structure/activity relationship studies showed that the compounds from benzoisothiazolone series are MPI-specific and exhibit favorable absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion profiles (7). We tested several compounds and selected MLS0315771 from this series for further characterization. Herein we describe the biological activity of MLS0315771. It was effective in several cell lines including CDG-Ia fibroblasts and directed mannose flux in favor of glycosylation in whole zebrafish embryos.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Radiolabels and Stable Isotopes

[2-3H]Mannose and [35S]Met/Cys were obtained from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. [6-3H]Glucose (60 Ci/mmol) and [1-14C]mannose (50 mCi/mmol) were from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc. [1,2-13C]Glucose and [4-13C]mannose were purchased from Omicron Biochemicals, South Bend, IN.

Cell Lines

HeLa cells, C3a hepatoma cells, and normal fibroblasts were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. C2C12 skeletal muscle cell line was a generous gift from Dr. Eva Engvall. The cells were grown in either α-minimal essential medium or Dulbecco's minimum Eagle's medium containing 2 mm glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum, and penicillin-streptomycin. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells were grown in endothelial cell medium, from Cell Applications, Inc., San Diego, CA. Hepatocytes required DMEM/F-12 (1:1) with insulin:transferrin:selenium supplement, 40 ng/ml dexamethasone, and 10% fetal bovine serum for growth. Media and FBS were obtained from Mediatech (Manassas, VA) and Thermo Scientific, respectively. Glutamine and antibiotics were purchased from Omega Scientific Inc., Tarzana, CA.

Reagents

MLS0315771 was obtained from Chemical Block Ltd., Limassol, Cyprus or synthesized from commercial reagents (7). A 10 mm stock in DMSO was frozen in aliquots at −20 °C. All other reagents were purchased from Sigma, except siLentFectTM, which was purchased from Bio-Rad, and siRNAs, which were from Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA. siRNA sequences are as follows: 1) sense, GCCUUAUGCAGAGUUGUGGtt; antisense, CCACAACUCUGCAUAAGGCtt; 2) sense, GCCAGUGGAUUGCUGAGAAtt, antisense, UUCUCAGCAAUCCACUGGCtt; 3) sense, GGAGAUUGUAACCUUUCUAtt, antisense, UAGAAAGGUUACAAUCUCctc.

PMM2 and MPI Enzyme Assays

A standard coupled assay using phosphoglucose isomerase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase with NADPH readout at 340 nm was used to estimate MPI and PMM2 activities (8). The original protocol was modified to a final volume of 200 μl, and enzyme activity was measured in a 96-well plate for 2 h using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Monosaccharide Analysis of [3H]Glucose- and [14C]Mannose-labeled Glycoproteins

Cells were labeled for 1 h with [6-3H]glucose and [1-14C]mannose at the same specific activity in medium containing physiological concentration of 5 mm glucose and 50 μm mannose. Monosaccharide analysis was performed as described previously (5).

MPI Knockdown

MPI was knocked down in HT29 colonic epithelial cells with three different siRNAs at different concentrations using siLentFectTM from Bio-Rad according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Cell-based Assay of MPI Inhibition Using [2-3H]Mannose

Cells were grown in 24-well plates to 70% confluency, incubated for 2 h with the indicated amounts of MPI inhibitor or DMSO in DMEM with 5 mm glucose, treated with 50 μCi/ml [2-3H]mannose and 5 μCi/ml [35S]Met/Cys, and incubated for another hour at 37 °C. The medium was removed, and cells were washed twice to remove free radiolabel. Cells were harvested and lysed in 10 mm Tris-HCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40 (pH 7.4). A portion of the lysate was precipitated using trichloroacetic acid (TCA), and radiolabel was determined. [3H]Mannose incorporation into N-glycans of glycoproteins was normalized to protein synthesis as measured by 35S incorporation. In some experiments, [2-3H]mannose labeling was done in the absence or presence of the indicated amount of unlabeled mannose.

Endoglycosidase H (Endo H) Digestion

Fibroblasts were grown in a 6-well plate to 75% confluency, and the indicated amount of mannose was added to the respective wells. The cells were labeled in the absence or presence of the inhibitor with 50 μCi/ml [2-3H]mannose and 5 μCi/ml [35S]Met/Cys in 0.5 mm glucose DMEM. Cell lysates were treated with or without Endo H overnight (9). Glycoproteins were precipitated with TCA as described above, the amount of radiolabel was determined, and Endo H sensitivity of N-glycans was calculated as a percentage of the control (without inhibitor).

Stable Isotope Labeling and Sample Preparation

Normal and CDG patient fibroblasts were preincubated with 10 μm MLS0315771 for 1 h in DMEM with 5% dialyzed FBS followed by the addition of [1,2-13C]glucose and [4-13C]mannose at a final concentration of 5 mm glucose and 50 or 200 μm mannose. After 4 h of incubation, the cells were washed thrice with PBS and extracted with chloroform-methanol (2:1), deionized water, and chloroform-methanol-water (10:10:3) solution (5). The cell pellet was dried and resuspended in PBS, 1% SDS, and N-glycans were released by N-glycosidase F. Purified glycans were hydrolyzed by 2 m trifluoroacetic acid at 100 °C and dried, and the hydrolysate was derivatized as described in Ref. 10. Dried derivatized products were resuspended in chloroform and analyzed by GC/MS.

Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry

Sugar analysis was done using a 15 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm SHRXI-5ms column (Shimadzu Corp, Kyoto, Japan) on a QP2010 Plus gas chromatograph/mass spectrometer (GC-MS) (Shimadzu) with an m/z range of 140–500 and ∼1.5 kV detector sensitivity. GC-MS ion fragments were corrected for natural 13C abundance using GC/MS-Solution version 2.50SU3 from Shimadzu. For each fragment, the intensities were corrected for the natural abundance of each element using matrix-based probabilistic methods as described (11–13). The 13C/(12C + 13C) ratios were used to calculate isotopic labeling proportion. For labeled hexoses, a fragmentation series of m/z 242 and 314 represents the [1,2-13C]glucose origin, and m/z 217 and 314 represent the [4-13C]mannose origin. Glucose contribution to mannose was calculated as an average of spectra intensity ratios at m244/(m242 + m244) and m316/(m314 + m316). Mannose contribution was calculated as an average of spectra intensity ratios at m218/(m217 + m218) and m315/(m314 + m315). Error bars in Figs. 3–7 indicate a range between two fragments used to calculate the abundance of each sugar (m242 and m314 for [1,2-13C]glucose origin and m217 and m314 for [4-13C]mannose origin).

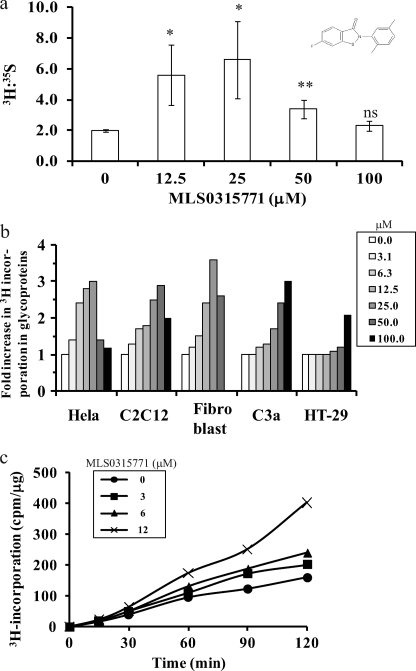

FIGURE 3.

MLS0315771 is a potent MPI inhibitor in cells. a, HeLa cells were labeled in the absence and presence of different concentrations of MLS0315771 with 50 μCi/ml [2-3H]mannose and 5 μCi/ml [35S]Met/Cys. The proteins were precipitated with TCA, and 3H incorporation in N-glycans was normalized to 35S incorporation. Data are an average of three independent determinations. Results with inhibitor were compared with those without inhibitor to calculate p values (Student's t test) *, p = 0.02–0.05, **, p = 0.01 or less, ns = not significant. b, inhibitor efficacy was compared in HeLa cells, C2C12 muscle cells, 42F fibroblasts, C3a hepatoma cells, and HT-29 colon cells. The cell lines were labeled with 50 μCi/ml [2-3H]mannose in the presence of different concentrations of MLS0315771, and [2-3H]mannose in the precipitated glycoproteins was determined. c, HeLa cells were labeled with 50 μCi/ml [2-3H]mannose in the absence and presence of different concentrations of MLS0315771. The cells were harvested and lysed at the indicated times (0, 30, 60, 90, 120 min). [2-3H]Mannose incorporation in the precipitated glycoproteins was determined.

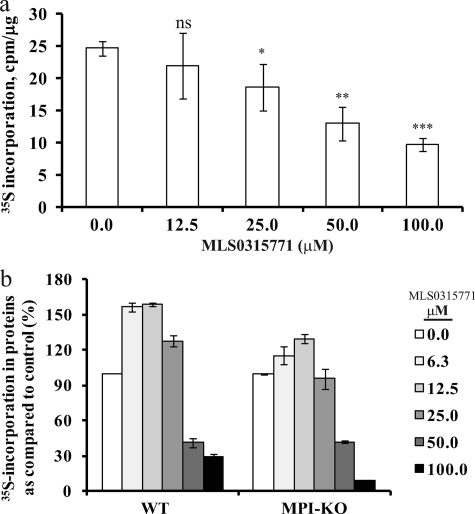

FIGURE 4.

MLS0315771 toxicity at higher concentrations is an off-target effect. a, HeLa cells were labeled with [35S]Met/Cys for 3 h in the presence of MLS0315771. 35S incorporation in TCA-precipitated glycoproteins was determined. The data with inhibitor were compared with data without inhibitor to calculate p values. *, p = 0.02–0.05, **, p = 0.01 or less, ***, p = 0.001 or less, ns = not significant. Significance values were calculated as compared with untreated control. b, mouse embryonic fibroblasts from WT and Mpi-KO mice were labeled with [35S]Met/Cys, and 35S incorporated into proteins was determined. Data presented are an average of three independent determinations.

FIGURE 5.

MLS0315771 increases mannose flux toward glycosylation. a and b, normal and CDG-Ia fibroblasts were preincubated with MLS0315771 for 2 h followed by labeling with 50 μCi/ml [2-3H]mannose and 5 μCi/ml [35S]Met/Cys for 1 h in the presence or absence of different concentrations of mannose without (a) or with MPI inhibitor (b). 3H and 35S incorporation was determined in precipitated glycoproteins. Data presented here are representative of two independent determinations. c and d, normal (c) and CDG-Ia (d) fibroblasts were preincubated with MLS0315771 for 1 h and then labeled for 4 h with stable labels: 5 mm [1,2-13C]glucose and 50 or 200 μm [4-13C]mannose. The glycans were isolated and hydrolyzed, and mannose was analyzed by GC/MS. The percentage of total N-glycan labeled with each isotope was determined. Numbers on top of each bar indicate the relative contribution to mannose from each isotope. Error bars indicate a range between two fragments used to the calculate abundance of each sugar (m242 and m314 for [1,2-13C]glucose origin and m217 and m314 for [4-13C]mannose origin). Data presented here are representative of two independent determinations.

FIGURE 6.

A subset of CDG-Ia patient fibroblasts responds to MLS0315771 treatment. Samples were treated with Endo H before precipitation and compared with untreated sample. a, Endo H sensitivity of CDG-Ia fibroblast line with or without inhibitor in the presence of mannose. b and c, Endo H sensitivity of different CDG-Ia fibroblasts bearing different mutations in PMM2 labeled in the absence (b) or presence (c) of the indicated amount of mannose. d, stable isotope labeling of three CDG-Ia patient fibroblasts with 5 mm [1,2-13C]glucose and 50 or 200 μm [4-13C]mannose and GC/MS analysis of mannose in N-glycans from CDG-Ia fibroblasts. − indicates no inhibitor, and + indicates 10 μm MLS0315771. Details of this analysis are same as in Fig. 5d. Data presented here are representative of two independent determinations.

FIGURE 7.

MLS0315771 modulates mannose flux in zebrafish embryos. a, 2-day old zebrafish embryos (10 per well) were treated without or with different concentrations of the inhibitor, and survival was determined over 2 days. Results are from two independent experiments. b, 4-day-old zebrafish embryos (30 per well) were labeled with 50 μCi/ml [2-3H]mannose and 5 μCi/ml [35S]Met/Cys in the absence or presence of the indicated amount of MPI inhibitor. Radiolabel was measured in glycoproteins precipitated from whole zebrafish lysate. Data are an average of two independent experiments. Significance values were calculated as compared with untreated control. *, p = 0.02–0.05, **, p = 0.01 or less, ns = not significant.

Zebrafish Protocols

Survival

Two-day-old zebrafish embryos were dechorionated, incubated with the indicated amounts of inhibitor or DMSO, and monitored for 2 days to check the viability of embryos.

Labeling

Four-day-old embryos were treated without or with the indicated amounts of MPI inhibitor and labeled with 50 μCi/ml [2-3H]mannose and 5 μCi/ml [35S]Met/Cys for 20 min. The embryos were washed thrice; lysed and proteins were precipitated using TCA as described above for the cells.

RESULTS

PMM2/MPI Ratio Determines the Contribution of Mannose to N-Glycans and Forms the Basis for Therapeutic Strategy for CDG-Ia

Earlier, we showed that glucose produces most Man-6-P in mammalian cell types (5). Because both PMM2 and MPI compete for Man-6-P, we hypothesized that the PMM2/MPI ratio partially determined the amount of mannose toward glycosylation. We labeled nine different cell lines with [6-3H]glucose and [1-14C]mannose and plotted the mannose contribution in N-glycans against the PMM2/MPI ratio (Fig. 1). Most cell types such as SKNSH neuroblastoma cells, C2C12 muscle cells, mouse hepatocytes, C3a hepatoma cells, and 293 kidney cells showed minimal contribution from mannose (2–4%). However, some of the fibroblasts and human umbilical vein endothelial cells showed a 10–20% contribution of mannose to glycoproteins, which correlated with their high PMM2/MPI ratio. CDG-Ib fibroblasts, which are deficient in MPI, exhibited the highest PMM2/MPI ratio and showed a preference for mannose over glucose for N-glycan synthesis. These findings suggest that modulating the ratio in favor of PMM2 via MPI inhibition increases the flux of available mannose toward glycosylation.

FIGURE 1.

Source of mannose in N-glycans depends on PMM2/MPI ratio. Nine cell lines were double-labeled with [6-3H]glucose and [4-14C]mannose at the same specific activity in the medium containing physiological concentration of 5 mm glucose and 50 μm mannose. The proportion of mannose-derived and glucose-derived mannose in N-glycans was calculated based on mannose analysis of acid hydrolysate and plotted against the ratio of enzymatic activities (PMM2/MPI). Cell lines assayed were CDG-Ib patient fibroblasts, CRL1947 fibroblasts, 42F fibroblasts, human umbilical vein endothelial cells, SKNSH neuroblastoma cells, C2C12 muscle cells, hepatocytes, C3a hepatoma cells, and 293 kidney cells.

We confirmed this further by siRNA-mediated MPI inhibition in HT-29 colonic epithelial cells and mannose flux measurement using [2-3H]mannose, which is a specific label commonly used to determine the fate of mannose within cells. [2-3H]Mannose is either catabolized through glycolysis ([2-3H]mannose → [2-3H]Man-6-P → Fru-6-P + 3H2O) or incorporated in glycoproteins (Scheme 1). MPI inhibition should divert more mannose toward glycosylation via PMM2, resulting in more [2-3H]Man-6-P incorporation into glycoproteins. MPI expression was knocked down by using three different siRNAs at various concentrations that reduced MPI enzyme activity by 40–70% (Fig. 2a). MPI knockdown followed by labeling with [2-3H]mannose indicated that 50–70% Mpi inhibition increases [3H]mannose incorporation into proteins by 4–7-fold (Fig. 2b). These data show that reducing MPI activity by even 40–50% could increase Man-6-P flux into the glycosylation pathway.

FIGURE 2.

siRNA-mediated MPI inhibition increases mannose flux for glycosylation. HT-29 human colonic epithelial cells were treated with three MPI siRNAs at different concentrations to block MPI activity to varying levels followed by labeling with [2-3H]mannose and glycoprotein precipitation using TCA. a, MPI activity in knockdown cells as compared with untreated cells. b, [2-3H]mannose incorporated in glycoproteins in siRNA-treated cells was plotted against the percentage of MPI inhibition (calculated using data from panel a).

MLS0315771 Is a Biologically Active Competitive MPI Inhibitor

We recently reported the synthesis and optimization of a series of benzoisothiazolone MPI inhibitors (7). We tested the compounds with IC50 < 25 μm from this series in a direct MPI assay using [2-3H]Man-6-P as substrate and measuring 3H2O ([2-3H]Man-6-P → Fru-6-P + 3H2O). MLS0315771 has IC50 ∼1 μm (7). Kinetic assay measurements showed that MLS0315771 is a competitive inhibitor, with Ki = 1.4 ± 0.3 μm (data not shown).

To assess the activity of MLS0315771 in cells, HeLa cells were labeled with [2-3H]mannose and [35S]Met/Cys. 3H incorporation into N-glycans was assessed as an indicator of the biological activity of the compound. It was normalized to protein synthesis, as estimated by 35S incorporation into proteins. MLS0315771 showed almost 3-fold increase in [2-3H]mannose incorporation in glycoproteins at 12.5 μm (Fig. 3a). To ensure that this activity was not cell line-specific, we tested MLS0315771 in four other human cell lines: C3a hepatoma cells, C2C12 muscle cells, dermal fibroblasts, and HT-29 colonic epithelial cells. Comparable efficacy was seen in all cell lines tested (Fig. 3b). The time course of [3H]mannose incorporation into HeLa cells at different MLS0315771 concentrations showed that the drug acts rapidly in cells (Fig. 3c).

MLS0315771 Toxicity Is an Off-target Effect

[35S]Met/Cys incorporation into proteins decreased at concentrations greater than 12.5–25.0 μm MLS0315771, indicating potential toxicity (Fig. 4a). A 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide assay based on mitochondrial dehydrogenases of viable cells as well as ATP determination using ATPliteTM showed no cellular toxicity up to 50–100 μm MLS0315771 in HeLa cells (data not shown). Also, no apoptosis was observed in the cells treated with MLS0315771 for 3 h (data not shown). To rule out any on target effect, we repeated the analysis on mouse embryonic fibroblasts from Mpi knock-out mice (Mpi-KO) (14). If adverse drug effects are due to MPI inhibition, then drug-treated Mpi-KO cells (devoid of MPI) should incorporate 35S label at levels comparable with untreated cells. However, when wild-type (WT) and Mpi-KO mouse embryonic fibroblasts were labeled with [3H]mannose and [35S]Met/Cys, we observed reduced incorporation of [35S]Met/Cys into both WT and Mpi-KO cells with increasing MLS0315771 concentration (Fig. 4b). This result strongly suggests that toxicity is an off-target effect. Based on these findings, we chose 10 μm MLS0315771 for subsequent experiments in CDG-Ia fibroblasts.

Mannose Supplementation Improves N-Glycan Structures in Some MLS0315771-treated CDG-Ia Fibroblast Lines

Fibroblasts from CDG-Ia patients incorporate 3–10-fold less [3H]mannose into N-glycans than fibroblasts from non-affected individuals (15). Mannose normalizes [2-3H]mannose incorporation of CDG-Ia fibroblasts in a dose-dependent manner. We hypothesized that treating CDG-Ia fibroblasts with MLS0315771 would allow lower concentrations of mannose to normalize [2-3H]mannose incorporation.

To evaluate this strategy, we labeled CDG-Ia patient and normal fibroblasts with [3H]mannose in the presence of the indicated amounts of mannose without (Fig. 5a) or with MLS0315771 (Fig. 5b). In the absence of inhibitor, we observed 30–50% reduced incorporation of [3H]mannose in CDG-Ia fibroblasts, whereas the addition of 10 μm MLS0315771 normalized [3H]mannose incorporation in N-glycans at a mannose concentration as low as 12.5 μm in cells from CDG-Ia patients (Fig. 5, a and b). We used low glucose medium for efficient uptake of [2-3H]mannose by fibroblasts. To confirm the relevance of our observations under physiological conditions, normal and CDG-Ia fibroblasts were differentially labeled with stable heavy isotopes [1,2-13C]glucose and [4-13C]mannose at 5 mm glucose and 50 or 200 μm mannose. N-Glycans were isolated and hydrolyzed, and mannose was estimated by GC-MS as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The percentage of total N-glycan labeled with [1,2-13C]glucose and [4-13C]mannose was determined, and the relative contribution from each isotope was calculated. The addition of MLS0315771 indeed increased the contribution from [4-13C]mannose in N-glycans in both normal as well as CDG-Ia fibroblasts (Fig. 5, c and d). [4-13C]Mannose incorporation in N-glycans from CDG-Ia fibroblasts increased from 9% (without inhibitor) to 24% (with inhibitor) in the presence of 50 μm mannose in CDG-Ia fibroblasts (Fig. 5d).

Endo H sensitivity of radiolabeled N-glycans was used to determine the proportion of normal high mannose glycan structures (9). Endo H is an endoglycosidase that acts on high mannose structure (-Asn-GlcNAc2Man6–9). It has been shown earlier that CDG-Ia fibroblasts synthesize truncated N-glycan structures that are Endo H-insensitive because of their smaller size (16). The proportion of N-glycans in normal fibroblasts that is Endo H-sensitive (80–100%) is higher than those in CDG-Ia patient cells (25–60%) (15). Mannose normalizes Endo H sensitivity in a dose-dependent manner (15). We predicted that modulation of mannose flux toward N-glycosylation should extend the truncated glycan structures in CDG-Ia cells, rendering an increased proportion Endo H-sensitive. The addition of 10 μm MLS0315771 along with mannose indeed increased the proportion of Endo H-sensitive N-glycans on CDG-Ia glycoproteins. Mannose as low as 6.25 μm was effective, suggesting that mannose was diverted toward N-glycosylation and improved the amount of complete glycan structures in CDG-Ia patient fibroblasts (Fig. 6a). Because CDG-Ia patients harbor different PMM2 mutations, we evaluated the effect of MLS0315771 in the cells from different CDG-Ia patients by Endo H digestion of radiolabeled N-glycans as well as analysis of stable isotope-labeled N-glycans. We predicted that the patient fibroblasts with sufficient residual activity will respond to MPI inhibitor. Patient cells with mutations C9Y/I132N and C9Y/D148N in PMM2 showed an increase in proportion of Endo H-sensitive N-glycans in the presence of 10 μm MLS0315771 and 12.5 μm mannose (Fig. 6, b and c). Mutations C9Y/D148N (Fig. 5d) and R123Q/C241S (Fig. 6d), when labeled with stable isotopes, also showed an increased contribution from mannose in the presence of MLS0315771 at 50 μm mannose, implying a positive response to MPI inhibitor under physiological conditions as well. R141H/C241S CDG-Ia showed an increase in mannose contribution at 200 μm mannose, but not at physiological mannose concentration. This suggests that R141H/C241S CDG-Ia patient cells required more mannose along with the inhibitor to correct glycosylation. R141H/V231M showed neither increased contribution from mannose with stable isotope labeling (Fig. 6d) nor increased proportion of Endo H-sensitive radiolabeled N-glycans (Fig. 6, b and c) in the presence of MPI inhibitor, suggesting non-responsive effect. Stable isotope results (Figs. 5d and 6d) are in agreement with the results of Endo H analysis of radiolabeled glycoproteins (Fig. 6, b and c). Our data showed that four out of nine patient cell lines responded favorably to MLS0315771 (Table 1), suggesting that our strategy might be useful for a subset of CDG-Ia patients. We also estimated PMM2 activities in patient fibroblasts (Table 1), which demonstrates that response to MLS0315771 depends not only on the residual activities, but also on the type of mutations.

TABLE 1.

CDG-Ia patient mutations and response to MLS0315771

+ indicates favorable response, and − indicates no response. Residual PMM2 activity in the patient fibroblasts was determined by the standard coupled assay described under “Experimental Procedures” and is expressed as the percentage of normal fibroblasts. Data presented here are an average of two independent determinations.

MLS0315771 Modulates Mannose Flux in a Whole Organism

We next asked whether MLS0315771 can alter metabolic flux in a whole animal. We chose zebrafish embryos because of cost-effectiveness, easier manipulation, and feasibility of testing multiple conditions. We first determined the survival of zebrafish embryos in the absence and presence of different concentrations of MLS0315771. The inhibitor was toxic to the embryos above 2 μm. At 8–10 μm, ∼50% embryos appeared sick within 20 min, and most of them died by 30–60 min (Fig. 7a).

To determine whether an MPI inhibitor diverts [3H]mannose toward glycosylation, 4-day-old zebrafish embryos were labeled with [3H]mannose in the absence and presence of different concentrations of MLS0315771 for 20 min (short time frame in which most of the embryos are alive at higher concentration). We have shown earlier that during labeling of cells with [3H]mannose, glycosylation precursors such as Man-6-P, Man-1-P, GDP-mannose, and dolichol-P-Man reach steady state within 10–15 min, which eventually are incorporated in glycoproteins (5). Labeled glycoproteins increased in the presence of MLS0315771, ∼4-fold at 8 μm (Fig. 7b), which corresponds to 55% MPI inhibition based on data in Fig. 2. These data demonstrate that it is possible to use small molecules to modulate metabolic flux in favor of glycosylation in vivo.

DISCUSSION

CDG patients have insufficient glycosylation. The number of cases being diagnosed and the types of CDG are rapidly growing (17, 18). Unfortunately, only two CDG types are treatable: CDG-Ib, treatable by mannose therapy, and CDG-IIc, treatable by fucose supplementation (19). The most common disorder, CDG-Ia, has no therapy. In the past, cell-permeable derivatives of mannose 1-phosphate (product of PMM2; Scheme 1) were synthesized and tested on CDG-Ia cell lines (20). Although they restored glycosylation to normal levels, their serum half-life was too short, necessitating a dose higher than 100 μm (20). Modulating metabolic flux in favor of glycosylation might be an effective therapeutic strategy. Recently zaragozic acid, a squalene synthase inhibitor, was shown to divert polyisoprene toward dolichol by lowering cholesterol biosynthesis, which could improve protein N-glycosylation (21).

In the present study, we describe a strategy based on recently discovered small molecules that could be useful to treat some CDG-Ia patients (7). Unlike CDG-Ib patients, who harbor mutations in the gene encoding MPI and show reversal of most symptoms when given 300–750 mg/kg of mannose per day (22), CDG-Ia patients do not benefit from mannose supplementation in part because MPI catabolizes most of the Man-6-P generated from incoming mannose. Therefore, we hypothesized that mannose supplementation in conjunction with MPI inhibition might represent a therapeutic strategy for CDG-Ia patients. It is likely that MPI could be inhibited in patients by 50% without adverse effects because heterozygous CDG-Ib individuals do not manifest the disease.

MLS0315771, a competitive MPI inhibitor from the benzoisothiazolone series, indeed diverted mannose flux toward glycosylation in several cell lines, including some CDG-Ia fibroblast lines. It extended glycan structure, as assessed by Endo H digestion of radiolabeled glycoproteins as well as stable isotope labeling. CDG-Ia patients have nearly 100 known mutations in PMM2. R141H and F119L are the most common. R141H is found in more than 75% of Caucasian patients (23). Homozygosity for R141H is incompatible with life; however, patients homozygous for F119L have been found (23). 88% of Danish patients have at least one of these two mutations, and 64% are compound heterozygotes for these mutations (24). Efficacy of MPI inhibitors will depend not only on the residual activity but also on the effects of the mutation on enzyme stability, substrate binding, and capacity to dimerize. Our results provide evidence that a single therapy would benefit only a subset of CDG-Ia patients.

Five out of six CDG-Ia patient lines harboring one R141H allele did not show any improvement in N-glycosylation. Structural studies show that the R141H mutant is impaired in substrate binding and has essentially no activity (25). If R141H allele is in combination with another allele that produces an unstable protein (V231M) or protein impaired in dimer interface interaction (F119L, P113L) (25, 26), then no improvement is observed with MPI inhibitor. Even if Man-6-P pools were mobilized toward mutant PMM2, they could not be utilized for glycosylation. R141H/C241S and R123Q/C241S fibroblasts where both R141H and R123Q are impaired in substrate binding showed improvement in mannose flux in the presence of MLS0315771 and mannose (Fig. 6d) because residual C241S-PMM2 is able to utilize mannose diverted by MPI inhibition (26). Interestingly, both C9Y/R141H and C9Y/I132N retain nearly 20% PMM2 activity, and only C9Y/I132N responds to MLS0315771. This clearly suggests that the effect of inhibitor on patients will depend not only on the residual PMM2 activity but also on the type of PMM2 mutations involved. MPI inhibitors may benefit only patients who retain sufficient residual stable and functional enzyme to be able to utilize the diverted substrate, e.g. mutations that cause an increase in Km or mutations in regulatory regions that will produce a reduced amount of fully active enzyme. For mutations such as F119L, V231M, and P113L, stabilizing PMM2 protein may be a better strategy.

MLS0315771 proved to be a potent MPI inhibitor in vitro and in vivo but is toxic to the cells above 10 μm. Our experiments strongly suggest that MLS0315771 toxicity is independent of MPI inhibition. Further optimization of the MLS0315771 scaffold is now required to produce a compound with comparable efficacy but lacking toxicity. Co-crystallization of a candidate inhibitor with MPI may identify residues involved in MPI binding, and then other residues could be altered to obtain a less toxic compound.

Pmm2 knock-out mice exhibit embryonic lethality (27). CDG patients have some residual activity. Thus, viable hypomorphic animal models are required to further test and optimize potential therapies. Given the difficulty and expense of generating numerous mouse models with varying genotypes, zebrafish are likely better suited for such studies. Generation of multiple hypomorphic lines of pmm2 by knocking in relevant patient mutations in zebrafish is easier than in mice. Also, the large number of embryos from zebrafish enables high throughput screening and identifying different therapeutic interventions appropriate for a particular set of mutations.

In summary, here we show that small molecules can be used to manipulate metabolic flux within cells and in a whole organism. This strategy can be used to divert Man-6-P toward glycosylation pathways, which might benefit a subset of CDG-Ia patients.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. Lars Bode for siRNA sequences and Dr. Duc Dong for providing zebrafish facilities. We appreciate Dr. Cherise Guess and Femke Hoevenaars for help in screening the compounds. We thank Dr. David Scott for help in GC-MS analysis. We also thank the members of our laboratory, Drs. Geetha Srikrishna and Jorge Munera, for providing comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-DK55615 and R21-HD062914 and The Rocket Fund (to H. H. F.).

- CDG

- congenital disorders of glycosylation

- MPI

- phosphomannose isomerase

- PMM2

- phosphomannomutase

- HK

- hexokinase

- Endo H

- endoglycosidase H

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide.

REFERENCES

- 1. Van Schaftingen E., Jaeken J. (1995) FEBS Lett. 377, 318–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pirard M., Matthijs G., Heykants L., Schollen E., Grünewald S., Jaeken J., van Schaftingen E. (1999) FEBS Lett. 452, 319–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grünewald S. (2009) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1792, 827–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Freeze H. H. (2006) Nat. Rev. Genet. 7, 537–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sharma V., Freeze H. H. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 10193–10200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Proudfoot A. E., Payton M. A., Wells T. N. (1994) J. Protein Chem. 13, 619–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dahl R., Bravo Y., Sharma V., Ichikawa M., Dhanya R. P., Hedrick M., Brown B., Rascon J., Vicchiarelli M., Mangravita-Novo A., Yang L., Stonich D., Su Y., Smith L. H., Sergienko E., Freeze H. H., Cosford N. D. (2011) J. Med. Chem. 54, 3661–3668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gracy R. W., Noltmann E. A. (1968) J. Biol. Chem. 243, 3161–3168 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Freeze H. H., Kranz C. (2010) in Current Protocols in Molecular Biology (Ausubel F. M., Brent R., Kingston R. E., Moore D. D., Seidman J. G., Smith J. A., Struhl K. eds) Vol. 4, pp. 17.13A. 1–17.13A. 25, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 10. Price N. P. (2004) Anal. Chem. 76, 6566–6574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nanchen A., Fuhrer T., Sauer U. (2007) Methods Mol. Biol. 358, 177–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Winden W. A., Wittmann C., Heinzle E., Heijnen J. J. (2002) Biotechnol. Bioeng. 80, 477–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Portnoy V. A., Scott D. A., Lewis N. E., Tarasova Y., Osterman A. L., Palsson B. Ø. (2010) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 6529–6540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DeRossi C., Bode L., Eklund E. A., Zhang F., Davis J. A., Westphal V., Wang L., Borowsky A. D., Freeze H. H. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 5916–5927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Panneerselvam K., Freeze H. H. (1996) J. Clin. Invest. 97, 1478–1487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Freeze H. H., Aebi M. (2005) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15, 490–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Haeuptle M. A., Hennet T. (2009) Hum. Mutat. 30, 1628–1641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jaeken J. (2010) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1214, 190–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Freeze H. H., Sharma V. (2010) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 655–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eklund E. A., Merbouh N., Ichikawa M., Nishikawa A., Clima J. M., Dorman J. A., Norberg T., Freeze H. H. (2005) Glycobiology 15, 1084–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haeuptle M. A., Welti M., Troxler H., Hülsmeier A. J., Imbach T., Hennet T. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 6085–6091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Niehues R., Hasilik M., Alton G., Körner C., Schiebe-Sukumar M., Koch H. G., Zimmer K. P., Wu R., Harms E., Reiter K., von Figura K., Freeze H. H, Harms H. K., Marquardt T. (1998) J. Clin. Invest. 101, 1414–1420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schollen E., Kjaergaard S., Legius E., Schwartz M., Matthijs G. (2000) Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 8, 367–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kjaergaard S., Skovby F., Schwartz M. (1998) Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 6, 331–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Silvaggi N. R., Zhang C., Lu Z., Dai J., Dunaway-Mariano D., Allen K. N. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 14918–14926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vega A. I., Pérez-Cerdá C., Abia D., Gámez A., Briones P., Artuch R., Desviat L. R., Ugarte M., Pérez B. (2011) J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 34, 929–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thiel C., Lübke T., Matthijs G., von Figura K., Körner C. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 5615–5620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vuillaumier-Barrot S., Hetet G., Barnier A., Dupré T., Cuer M., de Lonlay P., Cormier-Daire V., Durand G., Grandchamp B., Seta N. (2000)) J. Med. Genet. 37, 579–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Briones P., Vilaseca M. A., Schollen E., Ferrer I., Maties M., Busquets C., Artuch R., Gort L., Marco M., van Schaftingen E., Matthijs G., Jaeken J., Chabás A. (2002) J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 25, 635–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]