Background: TP53 members and NF-κB respond to stresses.

Results: TAp63α induced the expression of RelA and downstream genes involved in cell cycle arrest or apoptosis. TAp63α and RELA formed protein complexes resulting in their mutual stabilization, and TAp63α induced the RelA transcription.

Conclusion: We defined a novel a feedback loop between NF-κB and TP63.

Significance: TP53 members and NF-κB contribute to the regulation of cell death.

Keywords: Breast Cancer, Cell Death, NF-κB, p63, Protein Degradation, Protein-Protein Interactions, Transcription Factors, Tumor Suppressor Gene

Abstract

Tumor protein (TP)-p53 family members often play proapoptotic roles, whereas nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) functions as a proapoptotic and antiapoptotic regulator depending on the cellular environment. We previously showed that the NF-κB activation leads to the reduction of the TP63 isoform, ΔNp63α, thereby rendering the cells susceptible to cell death upon DNA damage. However, the functional relationship between TP63 isotypes and NF-κB is poorly understood. Here, we report that the TAp63 regulates NF-κB transcription and protein stability subsequently leading to the cell death phenotype. We found that TAp63α induced the expression of the p65 subunit of NF-κB (RELA) and target genes involved in cell cycle arrest or apoptosis, thereby triggering cell death pathways in MCF10A cells. RELA was shown to concomitantly modulate specific cell survival pathways, making it indispensable for the TAp63α-dependent regulation of cell death. We showed that TAp63α and RELA formed protein complexes resulted in their mutual stabilization and inhibition of the RELA ubiquitination. Finally, we showed that TAp63α directly induced RelA transcription by binding to and activating of its promoter and, in turn, leading to activation of the NF-κB-dependent cell death genes. Overall, our data defined the regulatory feedback loop between TAp63α and NF-κB involved in the activation of cell death process of cancer cells.

Introduction

TP53 members and NF-κB respond to a variety of intrinsic stresses, such as DNA damage, hypoxia, starvation, and cytokine activation (1–4). TP53 family members often play proapoptotic roles, whereas NF-κB functions as a proapoptotic and antiapoptotic regulator (1, 3, 5–7). However, any of these transcription factors are frequently deregulated in cancer cells (8). TP53 proteins promote cell death through senescence, cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and autophagy and promote metabolic changes. NF-κB, however, initiates the cellular responses utilizing specific metabolic pathways resulting in the synthesis of substrates for cell division (9–28). NF-κB consists of two subunits, p50 (NF-κB1) and p65 (RELA, NF-κB3), activated by cleavage and phosphorylation leading to a nuclear accumulation (29).

Tp63 encodes several protein isotypes with the long transactivation domain (TD)2 (TA-) and the short TD (ΔN-) (1, 2). ΔNp63 isotypes often function as a dominant negative inhibitor toward TAp63 isotypes and TP53 exerting the opposing transcriptional functions (1, 2). However, a few reports showed that ΔNp63 isotypes could play the proactive role in regulation of gene transcription, RNA splicing, and signaling leading to modulation of cell survival/cell death, tumorigenesis, and drug resistance (30–33). Recent findings further showed that the treatment of cancer cells with cisplatin generated phosphorylated (p)-ΔNp63α that appears to act similar to TAp63 isotypes or p53 by activating genes implicated in apoptosis and autophagy (34–36).

We and others previously showed that the NF-κB activation is a potential mechanism by which levels of ΔNp63α are reduced, thereby rendering the cells susceptible to cell death in the face of cellular stress (37–39). Although the NF-κB was found to regulate TAp63 promoter activity (40), the functional relationship between TAp63 isotypes and NF-κB is poorly understood. We showed that TAp63 and NF-κB form protein complexes and TAp63 regulates the NF-κB transcription and protein stability leading to a cell death phenotype.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals and Antibodies

Dimethyl sulfoxide (D8418) and MG-132 (C2211) were from Sigma-Aldrich. Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), TRIzolTM reagent, PCR primers for RelA, Bcl-xL, Bad, c-Myc, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphodehydrogenase (GAPDH), and the mouse monoclonal antibodies against RELA (436700) were from Invitrogen. We used the caspase (CASP)-3 Assay fluorometric kit (QIA70-1KIT; Calbiochem) and the Ready-To-GlowTM NF-κB Secreted Luciferase Reporter system (631743; Clontech). We used mouse monoclonal antibodies against poly(ADP-ribosylating) enzyme (PARP, sc-8007), TP63 (4A4, sc-71828), and histone H1 (sc-56403), and a rabbit polyclonal antibody against RELA (H-286, sc-7151), from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. We also used rabbit polyclonal antibodies to β-actin (AV40173) and FLAG (F7427), and mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibody (H3663), as well as a mouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (IgG, R3155) obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. A goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with HRP (LS-C55866) was from Lifespan Biosciences. The monoclonal antibodies to CDKN1A (p21WAF1, 2947), p-S536-RELA (3033), and polyclonal antibodies to BBC3 (Bcl2-binding component or PUMA), the TP53-up-regulated modulator of apoptosis (4976), Bcl-xL (2762), and caspase (CASP)-3 (9662) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology.

Cell Culture and Transfection

Immortalized human mammary epithelial cell line MCF10A (CRL-10317, expresses endogenous TAp63, and wild-type TP53) (41), and human non-small cell lung carcinoma cell line H1299 (CRL-5803, null for TP53 and TP63 expression) (33) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). H1299 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS. MCF10A were maintained in 1:1 mixture of DMEM and Ham's F12 medium with reduced Ca2+ 0.04 mm, 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, and 5% of Chelex-treated horse serum (all from Invitrogen), 100 ng/ml cholera toxin, 10 μg/ml insulin, 500 ng/ml (95%) hydrocortisone (all from Sigma). Cells were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Cells were transiently transfected with an empty vector or with the FLAG-tagged TAp63α, TAp63α, ΔNp63α, or RelA expression cassettes using FuGENE HD transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science) in accordance with the manufacturer's specifications. We used human TAp63α small interfering (si)RNA (5′-GCACACAGACAAAUGAAUUUU-3′, Stealth RNAiTM siRNA, HSS112631; Invitrogen), and RelA SureSilencing shRNA plasmid (5′-CTCAGAGTTTCAGCAGCTC-3′, KH01812P, SABiosciences). To eliminate the off-target effect of RelA-shRNA, a shRNA-resistant construct, pEGFP-p65Res (42) was used. Cells were transfected with 20 nm siRNA or 1 μg of shRNA using Lipofectamine SiRNAMAX (Invitrogen) or FuGENE HD (Roche Applied Science). Resulting cells were harvested 48 or 72 h after transfection. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were prepared as described (38, 39).

Plasmid Constructs

TAp63α was amplified from its cDNA and subcloned into the BamHI and NotI sites of the pFLAG-CMV-5.1 (E7901; Sigma) expression vector in front of the FLAG tag. Expression cassettes pCMV4-RelA, pCMV-HA-Ub, pBbc3-luc, and pCDKN1A-luc were purchased from Addgene (as deposited by Dr. Warner Greene, Gladstone Institute of Virology and Immunology, University of California at San Francisco, Dr. Dirk. P. Bohmann, University of Rochester, NY, and Dr. Bert Vogelstein, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD). The control (empty) TA-luc (LR0000) and RelA-luc (LR0051 and LR0052) reporter vectors were purchased from Panomics/Affymetrix. All clones were verified by sequencing.

Immunoblot Analysis

Cells were lysed on ice for 30 min in radioimmuneprecipitation assay buffer (150 mm NaCl, 100 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 1% Triton X-100, 1% deoxycholic acid, 0.1% SDS, 5 mm EDTA, and 10 mm NaF), supplemented with 1 mm PMSF and protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma). After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15min, the supernatant (total lysate) was harvested. Protein concentration was determined by Lowry-based DC Protein Assay kit (500-0112; Bio-Rad). 30 μg of protein mixed with Laemmli buffer (62.5 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.1 m DTT, and 0.01% bromphenol blue) was run on 4–12% NuPAGE, and proteins were detected by immunoblotting with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C followed by secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature, and bands were stained with an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Immunoprecipitation Analysis

Cells transfected with various constructs for 48 h were lysed using a lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100) with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma). Lysates were precleared with protein A-Sepharose beads and then incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with primary antibody or affinity matrix. Immune complexes were precipitated with protein A-Sepharose beads for 4h at 4 °C, and the nonspecific bound proteins were washed with the Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer at 4 °C. Beads in Laemmli buffer were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-FLAG or anti-HA antibodies.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

The empty pCMV vector, pCMV-TAp63α-FLAG construct, or siRNAs were introduced into MCF10A cells. A ChIP kit (Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions) along with the TP63 (4A4) antibody was used for ChIP, as described (32, 33, 35). The following primers were used: for the specific region, sense (−1900) 5′-CCCATCTCTATTTACAATAA-3′ (−1881), and antisense (−1570) 5′-CCGTGTCTCAAAAAATAAAT-3′ (−1551); for the nonspecific region, sense (−600) 5′-CCACAGCCGCATCTAGATTG-3′ (−581), and antisense (−370) 5′-GATCGGCGGGAGGGGGCCCT-3′ (−351) giving rise to the 350-bp and 250-bp PCR fragments, respectively. PCR was performed for 30 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 58 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 30 s using Taq polymerase (Invitrogen).

Semiquantitative (q)RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from 1 × 106 cells using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using qScriptTM cDNA SuperMix kit (Quanta Biosciences). Each semi-qRT-PCR was performed for 25 or 30 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 55 °C, and 1 min at 72 °C. Quantitation of the PCR product was performed after electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels and ethidium bromide staining. PCR primers are listed in supplemental Table S1.

Cellular Viability Assay (MTT Assay)

Cellular viability was monitored by the 3-(4,5-dimethyl thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide assay kit (MTT; ATCC). Briefly, 104 cells/well in 96-well plates were cultured in 5% FBS for 24h. 10 μl of MTT labeling reagent (5 μg/ml) was added to the culture medium without FBS, and the mix was then incubated in the dark for 4 h at 37 °C. Cells were lysed by the addition of 100 μl of an SDS-based detergent reagent, incubated for 2 h at 37 °C, and measurements (A570 nm to A650 nm) were obtained on a Spectra Max 250 96-well plate reader (Molecular Devices). Each assay was carried out in triplicate and repeated at least three times. Diagrams indicated the extent of cell viability expressed as a percentage of control.

Ubiquitination Assay

MCF10A cells were co-transfected with the pCMV-HA-Ub and pCMV4-RelA expression cassettes along with an empty vector, pCMV-TAp63α-FLAG plasmid or TAp63α siRNA. 48 h after transfection, cells were treated with 25 μm MG-132 and lysed in a buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma). Ubiquitinated proteins were recovered with the red anti-HA affinity gel (E6779; Sigma) and analyzed with the anti-RELA antibody.

NF-κB Luciferase Assay

MCF10A and H1299 cells were transfected with the pCMV-TAp63α-FLAG or control vector using FuGENE HD in the presence or absence of the pRelA-MetLuc2 reporter vector or pMetLuc2 control vector, and after 24–48 h, the RelA promoter-driven luciferase activity was determined by a Ready-To-Glow pNF-κB MetLuc luciferase reporter system (Clontech). Each transfection was performed in duplicate at least three times.

Measurement of RELA Half-life

100 μg/ml of cycloheximide (Sigma) was added to MCF10A cells 24 h after transfection with the indicated combination of plasmids. Protein levels were monitored at the indicated time points. To confirm equal loading, the membrane was reprobed with the β-actin antibody.

Promoter Luciferase Activity Assays

MCF10A cells were transiently transfected with the Bbc3-luc and pCDKN1A-luc reporter plasmids along with 500 ng of the pCMV-TAp63α expression plasmid (where indicated) in the presence or absence of the 1.0 μg pCMV4-RelA expression plasmid and the empty pGL3-Basic vector. For the NF-κB luciferase assay, MCF10A cells were transiently transfected with the RelA luciferase reporter plasmids along with the 500 ng of pCMV-TAp63α expression plasmid in the presence or absence of the 1.0 μg of pCMV4-RelA expression plasmid and the TA-luc empty vector. Transfection efficiency was determined by the Renilla luciferase gene-containing pRL-CMV plasmid (Promega). 48 h after transfection, cells were lysed in a lysis buffer (5× PLBR; Promega) with gentle shaking at room temperature for 20 min, and then total lysates were spun down at 13,000 rpm for 2 min to pellet the cell debris. The supernatants were transferred to a fresh tube, and the Dual luciferase activity in 2 μl (2 μg) of the cell lysates was measured according to the manufacturer's protocol (Promega). Firefly luciferase activity was monitored by a luminometer programmed as described elsewhere (38, 39). After stopping the firefly luciferase activity, the Renilla luciferase activity was then measured. Each experiment was repeated at three times with duplicate transfections.

Statistical Analysis

Data represent mean ± S.D. from independent experiments, and statistical analysis was performed using a Student's t test at a significance level of p < 0.05 to < 0.001.

RESULTS

TAp63α Regulates NF-κB/RelA Expression and Cell Death

TP63 plays a critical role in various cellular processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and senescence. We and others recently showed that NF-κB regulates ΔNp63α and TAp63α functions in cellular response to external stimuli (38, 39, 40). Because both TAp63α and NF-κB have been implicated in regulation of cell proliferation/differentiation, cell death/survival, we focused our studies on whether TAp63α plays a role in regulating NF-κB expression.

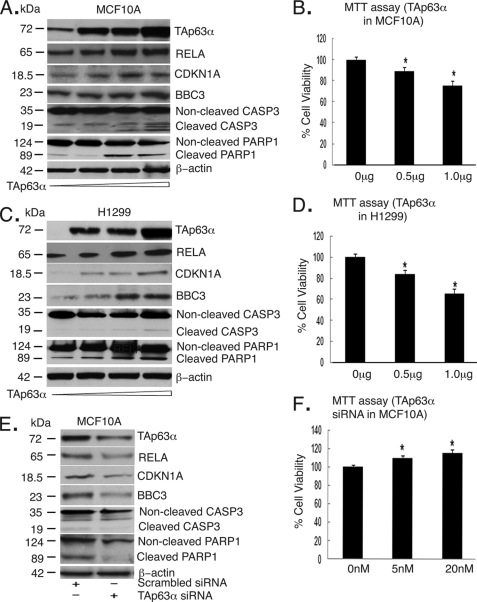

We initially examined how the TAp63α forced expression affects the RELA endogenous expression in MCF10A cells and H1299 cells (Fig. 1). We found that the RELA protein levels markedly increased by the ectopic TAp63α (0–1.5 μg) in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1, A and C). We further showed that TAp63α induced levels of CDKN1A and BBC3 proteins (Fig. 1, A and C), and subsequently increased cell death, as observed by the CASP3 and PARP cleavage (Fig. 1, A and C), and MTT assay (Fig. 1, B and D). Because MCF10A expresses detectable levels of the endogenous TAp63α, we next transfected MCF10A cells with the scrambled siRNA or TAp63α siRNA and found that the RELA protein levels markedly decreased upon the TAp63α silencing (Fig. 1E), whereas no changes were found under control (scrambled) conditions. Similarly, the TAp63α knockdown exclusively decreased the CDKN1A and BBC3 protein levels (Fig. 1E) and dramatically inhibited the cell death, as observed by a reduced CASP3 and PARP cleavage and MTT assay (Fig. 1F). These findings suggested that TAp63α could regulate RELA expression.

FIGURE 1.

TAp63α overexpression and siRNA affect the protein levels of RELA and cell death/cell cycle regulators and cell survival. A and C, immunoblotting of total lysates from MCF10A (A) and H1299 (C) cells with the indicated antibodies. B and D, MTT assay of MCF10A (B) and H1299 (D) cells after transfection with an increasing concentration (0–1.5 μg) of TAp63α for 24 h. E, Immunoblotting of total lysates (MCF10A cells) with the indicated antibodies. F, MTT assay performed on MCF10A cells after siRNA-dependent TAp63α down-regulation (20 nm siRNA, for 48 h). For CASP3 and PARP, positions of molecular mass markers are shown on the left. For the MTT assay, values from control cells transfected with the empty vector or scrambled siRNA were taken as 100%. *, p ≤ 0.05 (n = 3) compared with control (untransfected cells). Error bars, S.D.

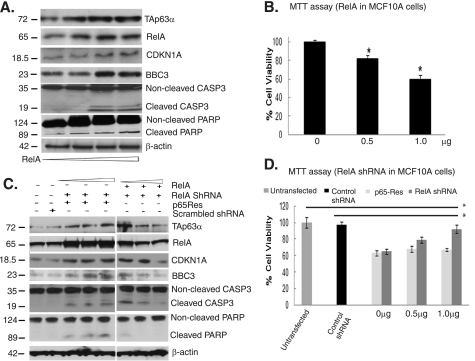

We next examined whether overexpression or down-regulation of RELA regulated CDKN1A, BBC3 protein levels, as well as cell survival. We showed that with the increased NF-κB expression (0–1.5 μg) up-regulated the TAp63α, CDKN1A, and BBC3 protein levels, increased the CASP3- and PARP-cleaved product levels (Fig. 2A), and markedly reduced the cell viability (Fig. 2B). At the same time, siRNA-mediated RELA knockdown decreased the TAp63α, CDKN1A, and BBC3 protein levels (Fig. 2C). To eliminate the off-target effect of RelA-shRNA, the shRNA-resistant pEGFP-p65Res construct (42) was added to the cells (Fig. 2D). Expression of p65Res in the RelA knocked-down MCF10A cells exhibited a “rescue” effect on TAp63α, CDKN1A, and BBC3 protein levels (Fig. 2D). However, shRNA-mediated knockdown of RELA dramatically reduced the cell death, as observed by the decreased CASP3 and PARP cleavage (Fig. 2C), or by cell viability assay (Fig. 2D), whereas co-transfection with the pEGFP-p65Res plasmid increased cell death (Fig. 2E). These data strongly suggest the specific effect of RelA down-regulation on TAp63α expression and cell death.

FIGURE 2.

Both RelA and TAp63α mediated cell death pathways. A and B, MCF10A cells transfected with the pCMV4-RelA expression cassette (0–1.5 μg) for 24 h. A, immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. B, MTT assay. C and D, MCF10A cells transfected with the RelA shRNA (0–1.5 μg) for 48 h followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. C, MCF10A cells were transfected with the 1 μg RelA or p65Res constructs for 24 h followed by transfection with RelA shRNA (0–1.5 μg) for 24 h and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. D, MTT assay. *, p ≤ 0.05 (n = 3) compared with control (untransfected cells or scrambled shRNA). Error bars, S.D.

To examine further the role for TAp63α/RelA axis in the cell death regulation, we transfected MCF10A cells with 20 nm TAp63α siRNA followed by increasing concentration of the ectopic RelA expression cassette (0–1.5 μg). In addition, we transfected MCF10A cells with 1 μg of RelA shRNA and then with the TAp63α expression cassette (0–1.5 μg). We found that the RELA up-regulation following the TAp63α down-regulation increased the CDKN1A, BBC3 protein levels, PARP cleavage, and induced cell death (Fig. 3, A and B). However, the TAp63α up-regulation following the RELA down-regulation failed to affect the CDKN1A, BBC3 protein levels, PARP cleavage, and cell death induction (Fig. 3, C and D). This observation suggests that TAp63α regulates cell viability of MCF10A cells through a RELA overexpression.

FIGURE 3.

TAp63α induced cell death pathways through RelA. MCF10A cells were transfected with the 20 nm TAp63α siRNA for 24 h followed by the increasing concentration of the ectopic RelA expression cassette (0–1.5 μg) for 24 h. A, immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. B, MTT assay. MCF10A cells were transfected with the 1 μg of RelA shRNA followed by the TAp63α expression cassette (0–1.5 μg). C, immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. D, MTT assay. For the MTT assay, values from control cells transfected with the empty vector or control (scrambled) siRNA/shRNA were taken as 100%. *, p ≤ 0.05 (n = 3) compared with control (untransfected cells). Error bars, S.D.

TAp63α Binds to RELA and Depresses Its Ubiquitin-mediated Degradation

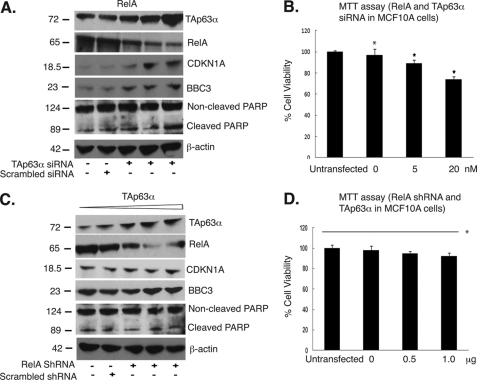

To explore the molecular mechanism underlying the TAp63α/NF-κB functional relationship, we transfected MCF10A cells with the TAp63α-FLAG expression cassette. We precipitated total lysates with an anti-FLAG antibody and probed TAp63α protein complexes with an antibody to RELA and vice versa. We showed that TAp63α and RELA, indeed, formed protein complexes in MCF10A cells (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

TAp63α-RELA protein interaction modulated the RELA protein level in MCF10A cells. A, complex formation between the TAp63α with RELA proteins. Top left panel, MCF10A cells were transfected with the TAp63α-FLAG or an empty FLAG vector. Immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed using anti-FLAG matrix and blotted with the anti-RELA antibody. Top right panel, MCF10A cells were transfected with the RelA-FLAG cassette or an empty FLAG-vector. Total lysates were precipitated with either control matrix or anti-RelA matrix and blotted with an anti-TP63 antibody. Immunoblotting for TAp63 and β-actin levels was used as input and loading controls, respectively. B, MCF10A cells were transfected with the scrambled siRNA or TAp63α siRNA for 48 h. Cells were treated with the 10 μm proteasome inhibitor, MG-132, for the indicated time periods. Total lysates were immunoblotted with the anti-RELA or anti-p63 antibodies. C–E, MCF10A cells were transfected with the 1.5 μg of RelA expression cassette along with the 1.5 μg of empty vector (C), 1.5 μg of TAp63α expression plasmid (D), or 20 nm TAp63α siRNA (E) for 48 h, as indicated. Cells were then treated with 100 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX). At the indicated time points, total lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. F, MCF10A cells were co-transfected with the RelA and HA-Ub expression plasmids, without or with the TAp63α expression vector or TAp63α siRNA for 36h and then treated with MG-132 for an additional 10 h. Total lysates were precipitated with anti-HA-matrix and blotted with the anti-RELA antibody. Immunoblot analysis for β-actin showed the loading levels.

We previously reported that IKKβ promotes a proteasomal degradation of ΔNp63α through a NF-κB-dependent pathway. Here, we further examined whether the physical interaction of TAp63α and RELA leads to a degradation of any of them. We transfected MCF10A cells with the scrambled siRNA and TAp63α siRNA and subsequently treated cells with the proteasome inhibitor, MG-132 or control medium. We found that the TAp63α down-regulation resulted in a decrease of the endogenous RELA, whereas the MG-132 treatment significantly restored the RELA levels (Fig. 4B), suggesting a proteasome-dependent mechanism for the RELA reduction induced by TAp63α knockdown.

To assess directly the role for TAp63α in regulation of RELA protein stability, we analyzed the effect of the TAp63α forced expression on the RELA half-life in MCF10A cells. Cells were co-transfected with the RELA and TAp63α expression cassettes or with scrambled and TAp63α siRNAs for 24 h. Cells were further exposed to cycloheximide for an additional 24 h. Immunoblot analysis of RELA at serial time intervals showed that the overexpression of the exogenous TAp63α increased the RELA half-life, whereas the down-regulation of the endogenous TAp63α dramatically modulated the RELA half-life (Fig. 4, C–E), supporting the notion that TAp63α positively regulates the RELA half-life in MCF10A cells.

Because TAp63α interacts with RELA and decreases its protein degradation, we further examined the role for ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in this process (43). We transfected MCF10A cells with the RelA and HA-Ub expression cassettes along with the increasing concentrations of the TAp63α or its siRNA for 36 h, and then cells were treated with MG-132 for an additional 10 h. Total lysates were precipitated with anti-HA-matrix, and then HA-Ub protein complexes were probed with the RELA antibody. We showed that the TAp63α down-regulation elevated the ubiquitination of RELA protein, whereas TAp63α overexpression modulated RELA ubiquitination in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4F, lane 2 to lanes 3-5, or lanes 6–7), suggesting that TAp63α effectively suppressed the RELA ubiquitination.

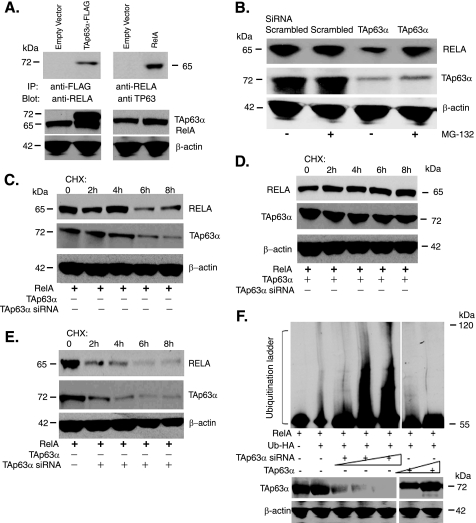

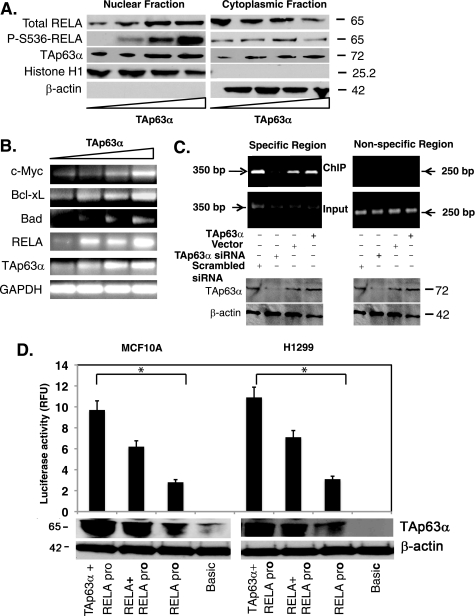

TAp63α Can Activate RelA Transcription

To exert its transcriptional activity, NF-κB is activated by phosphorylation and then translocates into the nucleus (29, 44). We showed that TAp63α overexpression led to an increasing Ser-536 phosphorylaton of RELA and subsequent translocation of activated RELA from cytoplasm to nucleus (Fig. 5A). Using semi-qRT-PCR we then found that TAp63α induction (0–1.5 μg) caused a significant increase in the RelA mRNA levels, and subsequently a dramatic increase in the levels of mRNAs (e.g. c-Myc, Bcl-xL and Bad) known to be up-regulated by RELA (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

TAp63α mediated the RelA transcriptional regulation. MCF10A cells were transfected with the TAp63α expression plasmid (0–1.5 μg). A, immunoblotting of the nuclear and cytosolic fractions with indicated antibodies. B, semi-qRT-PCR analysis for mRNA levels of indicated genes. C, ChIP assay performed with MCF10A cells, 72 h after transfection with the TAp63α expression construct or an empty vector, as well as with the TAp63α siRNA or scrambled siRNA. Total lysates aliquots of the same samples (for specific and nonspecific regions) were tested for both TAp63α and β-actin levels using immunoblotting, as indicated. TAp63α-bound RelA promoter DNA was precipitated with the 4A4 antibody followed by the PCR for the specific (−1900 to −1551bp; supplemental Fig. S1) and nonspecific regions (−600 to −351bp; supplemental Fig. S1), designated as ChIP. PCR with the purified DNA (Input) for both regions is shown. D, MCF10A (left) and H1299 (right) cells were transfected with the basic TA-luc and RelA-luc constructs along with the Renilla luciferase plasmid, with or without the TAp63α and/or RelA expression cassette for 24 h. The firefly luciferase activity was normalized for the Renilla luciferase activity. Immunoblotting for TAp63α and β-actin was performed. Data are presented as relative -fold change units (RFU) from the basic TA-luc activity designated as 1. *, p ≤ 0.001(n = 5) compared with basic TA-luc activity or RelA-luc activity alone.

We next performed the ChIP analysis of the endogenous RelA promoter (supplemental Fig. S1) in MCF10A cells transfected with an empty vector and TAp63α expression cassette or scrambled siRNA and TAp63α siRNAs. Using the anti-TP63 antibody, we found that TAp63α displayed a strong binding enrichment to the specific region (−1900 to −1551 bp, where TP63-responsive element is present) (32, 33) of the RelA promoter, whereas no binding with the nonspecific region (−600 to −351 bp, where TP63-responsive element is absent) of the RelA promoter (Fig. 5C). However, the siRNA-mediated TAp63α knockdown caused a significant decrease in its binding to the RelA promoter (Fig. 5C). Altogether, these data supported the notion that TAp63α directly regulates RelA transcription.

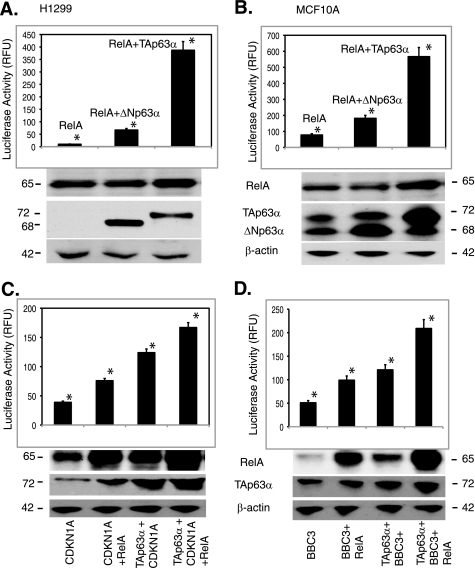

To examine further the effect of TAp63α on the RelA transcription, we transfected MCF10A cells and H1299 cells with the RelA luciferase reporter plasmid along with the TAp63α or RelA expression constructs. Using the luciferase reporter assay, we found that TAp63α dramatically increased the RelA promoter-driven luciferase activity in both MCF10A and H1299 cells (Fig. 5D). To confirm the activation of RelA after TAp63α up-regulation, we transfected MCF10A cells and H1299 cells with 1 μg of the TAp63α expression cassette along with the pRelA-MetLuc2 reporter construct or pMetLuc2 control construct (Fig. 6, A and B). Resulting cells were subjected to luciferase reporter assay (45). We thus found that the TAp63α overexpression significantly increased the RelA promoter-enhancer activity in both H1299 and MCF10A cells (Fig. 6, A and B).

FIGURE 6.

TAp63α increased levels of RelA-dependent genes. MCF10A cells were transfected with the TAp63α expression plasmid (0–1.5 μg). A and B, Ready-To-GlowTM Secreted Luciferase assay for the NF-κB/RelA response element-driven Metridia luciferase activity. 12 h after transfection of H1299 (A) and MCF10A (B) cells with the indicated constructs, the medium was replaced, and then after 16 h, samples of the medium were analyzed for secreted Metridia luciferase activity. The -fold induction was calculated following the substrate addition. C and D, luciferase reporter assay for the Cdkn1a (C) and Bbc3 (D) promoters. MCF10A cells were transfected with the basic TA-luc, pCdkn1a-luc, or Bbc3-luc constructs along with the Renilla luciferase plasmid and the TAp63α or RelA or basic vector for 24 h. Immunoblotting for each sample was performed for TAp63α, RelA, and β-actin. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized for the Renilla luciferase activity. Data presented as relative-fold change units (RFU) from the basic TA-luc activity are designated as 1. *, p ≤ 0.001(n = 5) compared with basic TA-luc activity, or pCdkn1a-luc (C) or Bbc3-luc (D) activities alone.

Next, we showed that both TAp63α and RELA concomitantly induced that expression of cell cycle arrest and pro-apoptotic genes, such as pCdkn1a and Bbc3 (46, 47). MCF10A cells were transfected with the pCdkn1a-luc or BBC3-luc constructs along with or without the TAp63α and/or RelA expression constructs for 24 h. We then showed that both TAp63α and RELA greatly increased Cdkn1a and Bbc3 promoter-driven luciferase activities (Fig. 6, C and D). In addition, co-transfection with the TAp63α and RelA expression cassettes further increased the Cdkn1a and Bbc3 promoter activities (Fig. 6, C and D), supporting the notion that TAp63α activates the RelA transcription leading to subsequent nuclear translocation of activated RELA and, in turn, to cooperative regulation of the NF-κB-dependent downstream target genes playing a critical role in cell cycle arrest or cell death.

DISCUSSION

TP53 family members (TP53, TP63, and TP73) shared their modular structure and function as key regulators of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis and as critical determinants of the tumor progression and chemotherapeutic response (1, 3, 9–11, 48–50) TP53 family proteins exert their function through activation or repression of the downstream target genes (1–3, 32, 51). The molecular mechanism underlying the choice between activation and repression of the target genes is very complex and not limited to the inhibitory effect of the protein isotypes lacking the long TD (also known as ΔN-isotypes).

TA-isotypes often displayed the “transactivation ability,” whereas the ΔN-isotypes may counter the function of p53 or TAp63 or TAp73 isotypes by various mechanisms, including competitive interaction with the same or similar cis-elements in target gene promoters (1–3, 9–11, 32, 51). However, ΔNp63 isotypes were shown to regulate the transcription of certain genes using their unique but short TD, as well as other mechanisms of molecular collaborating with other transcriptional factors (10, 37, 38). ΔNp63 induces proliferation and growth of tumor cells in vitro and in vivo and leads to an increased nuclear accumulation and signaling of β-catenin (30).

Conversely, siRNA knockdown of ΔNp63α from malignant cells overexpressing this oncogenic protein results in cell death, accompanied by the PARP1 cleavage (47, 48). Inhibition of endogenous ΔNp63α by lentivirus siRNA in squamous cell carcinoma cells was shown to induce the expression of proapoptotic genes, Bbc3 and Pmaip1 (phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-induced protein 1, Noxa), whereas induction of these genes following siRNA knockdown of ΔNp63α requires transactivation by p73 isotypes, suggesting that the elevation of endogenous ΔNp63α in squamous cell carcinoma cells promotes survival through direct repression of p73-dependent transcription of proapoptotic genes (48, 49).

As such, ΔNp63α can promote tumorigenesis through direct protein-protein interactions in key proliferative pathways, direct regulation of target genes, or inhibition of the transactivation activity of other TP53 family members (30, 32). Whereas p53 is stabilized and up-regulated in response to DNA damage induced by radiation or chemotherapeutic agents, ΔNp63 was shown to be down-regulated through the ATM-dependent phosphorylation mechanism (1, 3, 34–36, 38).

We defined a novel molecular mechanism underlying a reciprocal regulation (feedback loop) of the transcription factors NF-κB and TP63 in cells undergoing death pathway. We found that the TAp63α ectopic expression induced the expression of RelA, and downstream genes involved in cell cycle arrest or apoptosis and, in turn activated apoptotic pathways in MCF10A cells, whereas TAp63α siRNA inhibited these processes. We further found that the overexpression or down-regulation of RELA concomitantly modulated similar target genes and pathways leading to modulation of cell viability.

We then found that RELA is indispensable for the TAp63α-dependent regulation of cell death by forming TAp63α-RELA protein complexes resulting in mutual stabilization, as well as in decrease of RELA ubiquitination. On the contrary, the ΔNp63α-RELA functional relationship leads to a down-regulation of both ΔNp63α or RELA in squamous cell carcinoma cells (38, 39), whereas the forced ΔNp63α expression in MCF10A cells failed to affect the RELA and BBC3 protein levels. PARP cleavage Reduced CDKN1A level (supplemental Fig. S2). Finally, we determined that TAp63α directly induced the RelA transcription by binding to and activating of its promoter and, in turn leading to activation of the NF-κB-dependent target genes and contributing to regulation of cell survival. Our data support the notion that TAp63α and NF-κB exert a functional cooperation leading to regulation of the NF-κB-dependent downstream target genes playing a decisive role in cell cycle arrest/cell death (52–54). They also form a regulatory feedback loop that leads to a tune up-regulation of TAp63 or ΔNp63 expression by NF-κB and control of NF-κB expression by TAp63 or ΔNp63 under specific stress conditions and, in turn activate or repress death pathways in cancer cells upon ligand binding to transmembrane death receptors on the target cell (extrinsic caspase cascade pathway), or upon DNA damage/stress (intrinsic mitochondrial pathway associated with the release of cytochrome c, apoptosis-inducing factor, and Smac/Diablo proteins) (for review, see Refs. 55–57). Many components of these pathways are downstream transcriptional targets of TP53 and NF-κB (e.g. Apaf1, Bax, Bbc3, Bcl2, Bim, Casp1, Casp8, Casp11, Dapk1, Fas/CD95, FasL, Fadd, Gadd45B, Parp1, p53aip1, Pmaip1, Tnfr1, Tnfrsf6, Trail, and Xiap), as described elsewhere (58–65), suggesting the interplay between both apoptotic pathways.

The TP53 family and NF-κB proteins function as key regulators of cell death and survival, respectively (3, 7, 16, 27, 53, 55, 57). Under specific conditions, however, TP53 members can promote cell survival, whereas NF-κB can induce the cell death (7, 8, 22, 25, 26, 28). Given the transactivation ability for both NF-κB/RELA and TP53 members, it is very likely that the TP53 member-NF-κB protein complexes are essential for the transcriptional regulation of cell death/survival genes (7, 8, 22, 25, 28, 53, 54). Because TP53, TP63, or TP73 binds to the same or similar cis-elements (32), a recent cooperation between NF-κB and TP73 (20) should be extended to TP53 (22, 25, 28) and TP63 (37, 39). By transcriptional regulation and protein interactions, TP53 members and NF-κB contribute to the regulation of cell death, metabolism, and mitochondrial integrity, thereby emerging as important regulators of metabolic homeostasis (7, 8, 15–28, 50, 53, 59, 66, 67).

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-DE13561 through the NIDCR (to D. Sidransky and E. A. R.) and R01-EY018636-01 through the NEI (to D. Sinha and E. A. R.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2 and Table S1.

- TD

- transactivation domain

- CASP

- caspase

- luc

- luciferase

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethyl thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- PARP

- poly(ADP-ribosylating) enzyme

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR.

REFERENCES

- 1. Murray-Zmijewski F., Lane D. P., Bourdon J. C. (2006) Cell Death Differ. 13, 962–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Trink B., Osada M., Ratovitski E., Sidransky D. (2007) Cell Cycle 6, 240–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pietsch E. C., Sykes S. M., McMahon S. B., Murphy M. E. (2008) Oncogene 27, 6507–6521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fan Y., Dutta J., Gupta N., Fan G., Gélinas C. (2008) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 615, 223–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lin B., Williams-Skipp C., Tao Y., Schleicher M. S., Cano L. L., Duke R. C., Scheinman R. I. (1999) Cell Death Differ. 6, 570–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fujioka S., Schmidt C., Sclabas G. M., Li Z., Pelicano H., Peng B., Yao A., Niu J., Zhang W., Evans D. B., Abbruzzese J. L., Huang P., Chiao P. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 27549–27559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ak P., Levine A. J. (2010) FASEB J. 24, 3643–3652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vousden K. H. (2009) Aging 1, 275–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gressner O., Schilling T., Lorenz K., Schulze Schleithoff E., Koch A., Schulze-Bergkamen H., Lena A. M., Candi E., Terrinoni A., Catani M. V., Oren M., Melino G., Krammer P. H., Stremmel W., Müller M. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 2458–2471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Helton E. S., Zhang J., Chen X. (2008) Oncogene 27, 2843–2850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kawauchi K., Araki K., Tobiume K., Tanaka N. (2008) Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 611–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scherz-Shouval R., Weidberg H., Gonen C., Wilder S., Elazar Z., Oren M. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 18511–18516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jänicke R. U., Sohn D., Schulze-Osthoff K. (2008) Cell Death Differ. 15, 959–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maiuri M. C., Galluzzi L., Morselli E., Kepp O., Malik S. A., Kroemer G. (2010) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 181–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bitomsky N., Hofmann T. G. (2009) FEBS J. 276, 6074–6083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vousden K. H., Ryan K. M. (2009) Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 691–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rosenbluth J. M., Pietenpol J. A. (2009) Autophagy 5, 114–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Melino G., Bernassola F., Ranalli M., Yee K., Zong W. X., Corazzari M., Knight R. A., Green D. R., Thompson C., Vousden K. H. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 8076–8083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhou A., Scoggin S., Gaynor R. B., Williams N. S. (2003) Oncogene 22, 2054–2064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martin A. G., Trama J., Crighton D., Ryan K. M., Fearnhead H.O. (2009) Aging 1, 335–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schneider G., Henrich A., Greiner G., Wolf V., Lovas A., Wieczorek M., Wagner T., Reichardt S., von Werder A., Schmid R.M., Weih F., Heinzel T., Saur D., Krämer O. H. (2010) Oncogene 29, 2795–2806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Karl S., Pritschow Y., Volcic M., Häcker S., Baumann B., Wiesmüller L., Debatin K. M., Fulda S. (2009) J. Cell Mol. Med. 13, 4239–4256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang P., Qiu W., Dudgeon C., Liu H., Huang C., Zambetti G. P., Yu J., Zhang L. (2009) Cell Death Differ. 16, 1192–1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schneider G., Krämer O. H. (2011) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1815, 90–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ryan K. M., Ernst M. K., Rice N. R., Vousden K. H. (2000) Nature 404, 892–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dajee M., Lazarov M., Zhang J. Y., Cai T., Green C. L., Russell A. J., Marinkovich M. P., Tao S., Lin Q., Kubo Y., Khavari P. A. (2003) Nature 421, 639–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tergaonkar V., Pando M., Vafa O., Wahl G., Verma I. (2002) Cancer Cell 1, 493–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dey A., Tergaonkar V., Lane D. P. (2008) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7, 1031–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Karin M. (1991) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 3, 467–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Patturajan M., Nomoto S., Sommer M., Fomenkov A., Hibi K., Zangen R., Poliak N., Califano J., Trink B., Ratovitski E., Sidransky D. (2002) Cancer Cell 1, 369–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fomenkov A., Huang Y. P., Topaloglu O., Brechman A., Osada M., Fomenkova T., Yuriditsky E., Trink B., Sidransky D., Ratovitski E. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 23906–23914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Osada M., Park H. L., Nagakawa Y., Yamashita K., Fomenkov A., Kim M. S., Wu G., Nomoto S., Trink B., Sidransky D. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 6077–6089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sen T., Sen N., Brait M., Begum S., Chatterjee A., Hoque M. O., Ratovitski E., Sidransky D. (2011) Cancer Res. 71, 1167–1176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huang Y., Sen T., Nagpal J., Upadhyay S., Trink B., Ratovitski E., Sidransky D. (2008) Cell Cycle 7, 2846–2855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Huang Y. P., Chuang A., Romano R., Wu G., Sinha S., Legecous N., Trink B., Ratovitski E., Sidransky D. (2010) Cell Cycle 9, 328–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Huang Y., Ratovitski E. A. (2010) Aging 2, 959–968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. King K. E., Ponnamperuma R. M., Allen C., Lu H., Duggal P., Chen Z., Van Waes C., Weinberg W. C. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 5122–5131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chatterjee A., Chang X., Sen T., Ravi R., Bedi A., Sidransky D. (2010) Cancer Res. 70, 1419–1429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sen T., Chang X., Sidransky D., Chatterjee A. (2010) Cell Cycle 9, 4841–4847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wu J., Bergholz J., Lu J., Sonenshein G. E., Xiao Z. X. (2010) J. Cell. Biochem. 109, 702–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li N., Li H., Cherukuri P., Farzan S., Harmes D. C., DiRenzo J. (2006) Oncogene 25, 2349–2359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang J., Fu X. Q., Lei W. L., Wang T., Sheng A. L., Luo Z. G. (2010) J. Neurosci. 30, 11104–11113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Skaug B., Jiang X., Chen Z. J. (2009) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 769–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wan F., Lenardo M. J. (2010) Cell Res. 20, 24–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mauro C., Zazzeroni F., Papa S., Bubici C., Franzoso G. (2009) Methods Mol. Biol. 512, 169–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nakano K., Vousden K. H. (2001) Mol. Cell 7, 683–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yee K. S., Wilkinson S., James J., Ryan K. M., Vousden K. H. (2009) Cell Death Differ. 16, 1135–1145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rocco J. W., Leong C. O., Kuperwasser N., DeYoung M. P., Ellisen L. W. (2006) Cancer Cell 9, 45–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Leong C. O., Vidnovic N., DeYoung M. P., Sgroi D., Ellisen L. W. (2007) J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1370–1380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Eisenberg-Lerner A., Bialik S., Simon H. U., Kimchi A. (2009) Cell Death Differ. 16, 966–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kuribayashi K., Finnberg N., Jeffers J. R., Zambetti G. P., El-Deiry W. S. (2011) Cell Cycle 10, 2380–2389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pommier Y., Sordet O., Antony S., Hayward R. L., Kohn K. W. (2004) Oncogene 23, 2934–2949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tergaonkar V., Perkins N. D. (2007) Mol. Cell 26, 158–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Huang W. C., Ju T. K., Hung M. C., Chen C. C. (2007) Mol. Cell 26, 75–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Haupt S., Berger M., Goldberg Z., Haupt Y. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116, 4077–4085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Johnstone R. W., Ruefli A. A., Lowe S. W. (2002) Cell 108, 153–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Schmitt C. A., Fridman J. S., Yang M., Baranov E., Hoffman R. M., Lowe S. W. (2002) Cancer Cell 1, 289–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. O'Prey J., Crighton D., Martin A. G., Vousden K. H., Fearnhead H. O., Ryan K. M. (2010) Cell Cycle 9, 947–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yang X., Lu H., Yan B., Romano R. A., Bian Y., Friedman J., Duggal P., Allen C., Chuang R., Ehsanian R., Si H., Sinha S., Van Waes C., Chen Z. (2011) Cancer Res. 71, 3688–3700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Schilling T., Schleithoff E. S., Kairat A., Melino G., Stremmel W., Oren M., Krammer P. H., Müller M. (2009) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 387, 399–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Borrelli S., Candi E., Alotto D., Castagnoli C., Melino G., Viganò M. A., Mantovani R. (2009) Cell Death Differ. 16, 253–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Seitz S. J., Schleithoff E. S., Koch A., Schuster A., Teufel A., Staib F., Stremmel W., Melino G., Krammer P. H., Schilling T., Müller M. (2010) Int. J. Cancer 126, 2049–2066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Candi E., Dinsdale D., Rufini A., Salomoni P., Knight R. A., Mueller M., Krammer P. H., Melino G. (2007) Cell Cycle 6, 274–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ohanna M., Giuliano S., Bonet C., Imbert V., Hofman V., Zangari J., Bille K., Robert C., Bressac-de Paillerets B., Hofman P., Rocchi S., Peyron J. F., Lacour J. P., Ballotti R., Bertolotto C. (2011) Genes Dev. 25, 1245–1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pahl H. L. (1999) Oncogene 18, 6853–6866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Frank A. K., Leu J. I., Zhou Y., Devarajan K., Nedelko T., Klein-Szanto A., Hollstein M., Murphy M. E. (2011) Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 1201–1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Schuster A., Schilling T., De Laurenzi V., Koch A. F., Seitz S., Staib F., Teufel A., Thorgeirsson S. S., Galle P., Melino G., Stremmel W., Krammer P. H., Müller M. (2010) Cell Cycle 9, 2629–2639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.