Background: The glucocorticoid (GR) and peroxisome proliferator-activated (PPARγ) receptors are antagonists of lipid metabolism.

Results: Protein phosphatase 5 (PP5) dephosphorylates GR and PPARγ to reciprocally control their activities.

Conclusion: PP5 is a switch point in nuclear receptor control of lipid metabolism.

Significance: PP5 is a potential new drug target in the treatment of obesity.

Keywords: Adipogenesis, Chaperone Chaperonin, Glucocorticoid Receptor, Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor (PPAR), Protein Phosphatase, Protein Phosphatase 5, TPR Proteins, Glucocorticoid Receptor, Lipid

Abstract

Glucocorticoid receptor-α (GRα) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) regulate adipogenesis by controlling the balance between lipolysis and lipogenesis. Here, we show that protein phosphatase 5 (PP5), a nuclear receptor co-chaperone, reciprocally modulates the lipometabolic activities of GRα and PPARγ. Wild-type and PP5-deficient (KO) mouse embryonic fibroblast cells were used to show binding of PP5 to both GRα and PPARγ. In response to adipogenic stimuli, PP5-KO mouse embryonic fibroblast cells showed almost no lipid accumulation with reduced expression of adipogenic markers (aP2, CD36, and perilipin) and low fatty-acid synthase enzymatic activity. This was completely reversed following reintroduction of PP5. Loss of PP5 increased phosphorylation of GRα at serines 212 and 234 and elevated dexamethasone-induced activity at prolipolytic genes. In contrast, PPARγ in PP5-KO cells was hyperphosphorylated at serine 112 but had reduced rosiglitazone-induced activity at lipogenic genes. Expression of the S112A mutant rescued PPARγ transcriptional activity and lipid accumulation in PP5-KO cells pointing to Ser-112 as an important residue of PP5 action. This work identifies PP5 as a fulcrum point in nuclear receptor control of the lipolysis/lipogenesis equilibrium and as a potential target in the treatment of obesity.

Introduction

In humans, obesity often results from alterations to carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, processes principally controlled by insulin, glucocorticoids, and fatty acids. Metabolic disorders or high fat diets cause dysregulation of metabolism, resulting in lipid accumulation in adipose, muscle, and liver and bestowing resistance to insulin and other hormones. In times of stress or fasting, glucocorticoids (GCs)3 stimulate fat breakdown in adipose tissue and protein degradation in muscle to redistribute to the liver non-hexose substrates, such as amino acids and glycerol for gluconeogenesis and fatty acids for β-oxidation (1). Interestingly, chronic glucocorticoid elevation leads to insulin resistance and glucose intolerance, which may result in type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome. In adipose, the equilibrium between lipolysis and lipogenesis is controlled by two opposing nuclear receptor members: glucocorticoid receptor-α (GRα) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) (2). In adipose, GRα regulates the expression of lipolytic and antilipogenic genes, such as hormone-sensitive lipase, diacylglycerol acyltransferase-1 (DGAT1), glucocorticoid-inducible leucine zipper, lipoprotein lipase inhibitor angiopoietin-like protein-4 (ANGPTL4), and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-4 (3–6). Conversely, PPARγ up-regulates the expression of genes, such as the fatty acid importer cluster of differentiation-36 (CD36), lipoprotein lipase, sterol-responsive element-binding protein-1c, and perilipin, that promote lipid uptake, synthesis, and storage (7–9). For these reasons, signaling molecules that can regulate the balance of actions of these hormones would be important factors controlling the lipometabolic equilibrium.

The Hsp90 chaperone complex plays an essential role in the regulation of GRα and other nuclear receptors (10, 11). As co-chaperones to Hsp90, the tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) proteins FK506-binding protein 52 (FKBP52), FKBP51, and protein phosphatase 5 (PP5) are important modulators of GRα activity (12–14). Hormone-free GRα in most cells preferentially interacts with FKBP51 and PP5 with a reduced presence of FKBP52 (15). Despite this, FKBP52 is still needed as a positive regulator of GRα to control its transcriptional activity in a gene-specific manner (16), whereas most studies suggest that FKBP51 and PP5 are negative regulators of GRα (17–19). In contrast to GRα, very little is known concerning Hsp90 and TPR protein involvement with PPARs. Studies by Vanden Heuvel, Perdew, and co-workers (20, 21) showed interaction of Hsp90 with PPARα, PPARβ, and PPARγ with an inhibitory effect on PPARα transcriptional activity. Of particular interest, use of a peptide specific to the TPR domain of PP5 caused a large increase in PPARα activity (21), providing the first, albeit indirect, evidence that PP5-mediated dephosphorylation is important to PPAR action.

GRα and PPARγ are differentially regulated by phosphorylation. In response to ligand, GRα phosphorylation at serines 212, 220, and 234 (mouse sequence) has been observed with most studies showing a positive correlation with GRα activity (22, 23). Phosphorylation of PPARγ is typically induced by growth factors that utilize MAPK signaling to target serine 112 (mouse sequence) and inhibit the differentiation-inducing properties of the receptor (24, 25). Dephosphorylation of GRα by PP5 has been documented (17, 26–28), and in general, the results support a model in which PP5 modulates gene-specific GRα activity. Interestingly, no phosphatase specifically targeting PPARγ has been identified.

PP5 is a unique member of the phosphoprotein phosphatase family of serine/threonine phosphatases in that it contains a TPR domain (29–31). Binding of PP5 to Hsp90 occurs through the TPR domains and is required to activate phosphatase activity. Interestingly, the TPR domain contains binding sites for long-chain, polyunsaturated fatty acids, the binding of which also activates PP5 activity (32, 33). We, therefore, reasoned that a major role of PP5 is to regulate phosphorylation of signaling molecules, especially nuclear receptors, involved in lipid metabolism. In this work, we addressed this hypothesis by testing the role of PP5 in models of adipogenesis controlled by GRα and PPARγ. We showed that PP5 can directly regulate the phosphorylation of GRα and PPARγ to control the balance of lipolysis and lipogenesis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Dexamethasone (Dex), HEPES, powdered DMEM, Tris, EDTA, PBS, sodium molybdate, protease inhibitor mixture, and sodium chloride were all obtained from Sigma. Iron-supplemented newborn calf serum and fetal bovine serum were from Hyclone Laboratories Inc. (Logan, UT). Immobilon-FL polyvinylidene fluoride membrane was obtained from Millipore Corp. (Bedford, MA). Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent and Opti-MEM were obtained from Invitrogen.

Cell Lines and Adipogenesis Assays

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were isolated from wild-type (WT) and PP5 knock-out (KO) E13.5 embryos as described previously (34). Cells were routinely cultured in DMEM containing 10% bovine calf serum with 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Adipogenic differentiation of MEF cells was achieved by treatment with 1 μm Dex, 830 nm insulin, 100 μm isobutylmethylxanthine, and 5 μm rosiglitazone on Day 0 and 830 nm insulin plus 5 μm rosiglitazone on Day 2 followed by continued incubation with 5 μm rosiglitazone in 10% FBS until Day 8 (35, 36). This is referred to as the Dex, insulin, isobutylmethylxanthine, and rosiglitazone (“DIIR”) protocol. Upon differentiation, cells were stained with Nile Red to visualize lipid content, and densitometry was used as a direct measure. Total RNA extracted from Nile Red-stained cells was used for real time PCR analysis (see below). Quantitation of free fatty acid content in media was performed with the Wako NEFA-C non-esterified free fatty acid kit (Wako Chemicals USA, Inc., Richmond, VA) and measurement on a Spectra Max Plus spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices).

Quantitative Real Time PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from mouse tissues using the 5-Prime PerfectPure RNA Tissue kit (Fisher). Total RNA was read on a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer, and cDNA was synthesized using the iScript cDNA Synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). PCR amplification of the cDNA was performed by quantitative real time PCR using the qPCR Core kit for SYBR Green I (Applied Biosystems). The thermocycling protocol consisted of 10 min at 95 °C and 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 61 °C, and 20 s at 72 °C and finished with a melting curve ranging from 60 to 95 °C to allow distinction of specific products. Primers specific to each gene were designed using Primer Express 3.0 software (Applied Biosystems). Normalization was performed in separate reactions with primers to 18 S mRNA (TTCGAACGTCTGCCCTATCAA and ATGGTAGGCACGGCGACTA). All primer sequences were uploaded to PRIMERFinder, a primer database.

Transfections

WT and PP5-KO cells were plated on 6-well dishes in DMEM containing 10% iron-supplemented calf serum prestripped of endogenous steroids by 1% (w/v) dextran-coated charcoal (for GRα studies) or in serum-free DMEM (for PPARγ studies). At 85–90% confluence, cells were washed with Opti-MEM and transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 according manufacturer's protocol. For GRα studies, cells were either left untransfected or were transfected with the triple serine to alanine mutant (serines 203, 211, and 226) of human GR (GR3A) followed by adipogenesis assay or reporter gene assay using murine mammary tumor virus-luciferase. For PPARγ studies, cells were transfected with expression plasmids for PPARγ2 (newly isolated cDNA inserted into pcDNA3.1+) or the S112A-PPARγ2 mutant, and retinoid X receptor-α followed by adipogenesis assay or reporter gene assay using peroxisome proliferator response element-luciferase. In reporter gene assays, pRL-CMV-Renilla was used for normalization of transfection efficiency. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were treated with vehicle, 1 μm Dex, or 1 μm rosiglitazone for an additional 24 h until harvest. Cell lysates were prepared, and the assay was performed using the Promega luciferase system.

Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) Imaging

WT and PP5-KO MEF cells were seeded on laminin-coated coverslips in 60-mm dishes at 300,000–500,000 cells/dish in DMEM containing charcoal-stripped serum. Cells were transfected with GFP-GRα, GFP-PPARγ2, or empty vector (pEGFP-C1) constructs. Fluorescent images of the living cells were obtained 24 h post-transfection and 1 h after vehicle or hormone treatment using a Leica DMIRE2 confocal microscope (Leica, Mannheim, Germany). Cells were scanned at low laser power to avoid photobleaching. Leica confocal software was used for data analysis. The figures show representative cells from each type of transfection. At least 50–100 cells from each transfection were inspected.

Whole Cell Extraction

Cells were washed and collected in 1× PBS followed by centrifugation at 1500 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 1× PBS. After a short spin at 20,800 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, the pellet was rapidly frozen in a dry ice/ethanol mixture and stored at −80 °C overnight. The frozen pellet was then resuspended in 3 volumes of cold whole cell extract buffer (20 mm HEPES, 25% glycerol, 0.42 m NaCl, 0.2 mm EDTA, pH 7.4) with protease and phosphatase inhibitors and incubated on ice for 10 min. The samples were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Protein levels were measured spectrophotometrically using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE). The supernatants were either stored at −80 °C or used immediately for Western analysis.

Immunoadsorption of GR and PPAR Complexes

Cells were harvested in HEMG (10 mm HEPES, 3 mm EDTA, 20 mm sodium molybdate, 10% glycerol, pH 7.4) plus protease inhibitor mixture and set on ice for 20 min followed by Dounce homogenization. Supernatants (cytosol) were collected after a 10-min 4 °C centrifugation at 20,800 × g and then precleared with protein A or G-Sepharose nutating for 1 h at 4 °C. Samples were spun down, split into equal aliquots of cytosol, and immunoadsorbed overnight with FiGR antibody against total GR, GFP antibody for PPARγ, and appropriate controls (non-immune mouse IgG) at 4 °C under constant rotation. Pellets were washed five to seven times with TEG (10 mm Tris, 3 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol, 50 mm NaCl, 20 mm sodium molybdate, pH 7.4), and complexes were eluted with 6× SDS sample buffer.

Gel Electrophoresis and Western Blotting

Protein samples were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electrophoretically transferred to Immobilon-FL membranes. Membranes were blocked at room temperature for 1 h in TBS (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl) containing 3% BSA plus phosphatase inhibitors. Incubation with primary antibody was done overnight at 4 °C. After three washes in TBST (TBS plus 0.1% Tween 20), membranes were incubated with infrared anti-rabbit (IRDye 800; green) or anti-mouse (IRDye 680; red) secondary antibodies (LI-COR Biosciences) at 1:15,000 dilution in TBS for 2 h at 4 °C. Immunoreactivity was visualized and quantified by infrared scanning in the Odyssey system (LI-COR Biosciences). FiGR monoclonal antibody against GR and rabbit polyclonal antibody against PP5 were generous gifts from Jack Bodwell (Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, NH) and Michael Chinkers (University of South Alabama College of Medicine, Mobile, AL), respectively. Phospho-GRα Ser-112, Ser-220, and Ser-234 antibodies were made as described previously (37) and provided by Dr. Michael Garabedian (New York University). Antibodies against PPARγ (sc-7273) and Hsp90 (sc-8262) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Ser-112 Phospho-PPARγ2 antibody was purchased from Abcam (Abcam PLC, Cambridge, MA). Anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal IgG (F-3165) was from Sigma.

Fatty-acid Synthase Enzyme Activity

Fatty-acid synthase activity was assayed by the incorporation of radiolabeled malonyl-CoA into palmitate as described previously (38). Briefly, cells were lysed in buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 1.0 mm EDTA, 1.0 mm DTT, phosphatase and protease inhibitors) and centrifuged (12,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C). Lysates were incubated (20 min at 37 °C) with 166.6 μm acetyl-CoA, 100 mm potassium phosphate, pH 6.6, 0.1 μCi of [14C]malonyl-CoA, and 25 nm malonyl-CoA in the absence or presence of 500 μm NADPH. The reaction was stopped with a 1:1 chloroform:methanol solution, mixed (30 min at 20 °C), and centrifuged (12,500 × g for 30 min). The supernatant was vacuum-dried, and the pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of water-saturated butanol. Following addition of 200 μl of double distilled H2O, vortexing, and spinning (1 min), the upper layer was removed for re-extraction. The butanol layer was dried and counted. Protein was quantified by Bio-Rad protein assay, and results were expressed as relative cpm 14C incorporated/μg of cell lysate.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) using analysis of variance combined with Tukey's post-test to compare pairs of group means or unpaired t tests. p values of 0.05 or smaller were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Interaction of PP5 with GR and PPARγ

We have previously described the generation of mice with global ablation of PP5 and isolation of WT and PP5-ablated (KO) MEF cells (34). Western blot analysis showed that the PP5-KO cell line was completely devoid of PP5 protein and the development of a “rescued” PP5-KO cell line expressing FLAG-tagged PP5 (Fig. 1A). As seen below, these MEF cells readily responded to adipogenic stimuli, allowing us to investigate the potential contribution of PP5 to nuclear receptor control of the process. As a first test of this hypothesis, the interaction of PP5 with GR and PPARγ in MEF cells was investigated by co-immunoprecipitation analysis. Results in WT MEF cells show that hormone-free GR selectively interacted with FKBP51 and PP5 but had little to no interaction with FKBP52 or Cyp40 (Fig. 1B). These results are in agreement with those obtained in mouse L929 fibroblast cells (15). In the PP5-KO cells, the level of FKBP51 interaction with GR was unchanged, and no increased recruitment of FKBP52 or Cyp40 was observed. This suggests that compensatory interaction with GR by other TPR proteins does not occur in the absence of PP5. To date, no interactions between PPARγ and co-chaperones have been reported. Our initial attempts showed very little binding between PP5 and ligand-free PPARγ. However, when cells were treated with rosiglitazone, a rapid and transient recruitment of PP5 to PPARγ was observed (Fig. 1C). Because rosiglitazone induces the proadipogenic activity of PPARγ, we reasoned that PP5 was most likely serving as a positive regulator of receptor activity (tested below). In contrast, hormonal activation of GR promotes recruitment of the positive regulator FKBP52 but no recruitment of PP5 (39).

FIGURE 1.

Interaction of PP5 with GRα and PPARγ. A, Western blot analysis of whole cell extracts from WT and PP5-KO MEF cells demonstrating a complete lack of PP5 in the KO cells and restoration of PP5 expression following rescue of PP5-KO cells with FLAG-PP5 (KO-R). Hsp90 was used as loading control. B, co-immunoadsorption of hormone-free GR heterocomplexes demonstrating preferential interaction with FKBP51 and PP5. GR complexes from WT and PP5-KO cells were adsorbed to protein G-Sepharose using FiGR monoclonal antibody to GR (I) or non-immune IgG (NI) followed by Western blotting for GR and associated TPR proteins. C, co-immunoadsorption of PPARγ with PP5 is dependent on rosiglitazone activation. WT MEF cells were transfected with GFP-PPARγ2 construct followed by a time course of treatment with 1 μm rosiglitazone. Cell extracts were immunoadsorbed with antibody to GFP (I) or non-immune IgG (NI) followed by Western blotting for PPARγ and PP5. A representative of three independent experiments is shown.

PP5 Deficiency Blocks Adipogenesis

Robust induction of adipogenesis in the MEF cells was achieved by treatment with a mixture containing DIIR. This mixture has been successfully used on similar MEF cell lines (35, 36), producing an adipogenic response comparable with similarly treated 3T3-L1 cells (40). Fig. 2, A and B, shows a strong lipogenic response in WT cells as measured by Nile Red staining and direct biochemical assay. In contrast, PP5-KO cells had dramatically decreased lipid accumulation. Lack of induction was not an artifact of the PP5-KO cell line as rescue of PP5 expression in the KO line completely reversed the phenotype. To address the relative contributions of fatty acid import and de novo lipogenesis to the observed phenotype in PP5-KO cells, assays were performed for free fatty acid (FFA) levels in the culture media and for intracellular fatty-acid synthase activity (Figs. 2, C and D). As expected, differentiated WT cells exhibited increased fatty-acid synthase activity and reduced levels of FFAs in the media, indicating that both de novo synthesis and FFA import contribute to the lipid-laden phenotype. In contrast, differentiated PP5-KO cells showed significantly higher FFA in the media and reduced fatty-acid synthase activity compared with differentiated WT cells, suggesting an impairment of both processes.

FIGURE 2.

PP5 is required for lipogenesis and induction of adipogenic genes. A, detection of lipid accumulation in WT, PP5-KO, and rescued PP5-KO cells by Nile Red staining. Adipogenic differentiation (D) or undifferentiation (U) was achieved by treatment of MEF cells with DIIR mixture for 8 days followed by staining for lipid content. Phase-contrast images are also shown. B, quantification of intracellular lipid in cells treated in A. ###, p < 0.001 (versus WT undifferentiation); ***, p < 0.001 (versus WT differentiation); ∧∧∧, p < 0.001 (versus PP5-KO differentiation) (±S.E.; n = 3). C, biochemical quantification of free fatty acid content in the growth media of cells treated in A. ##, p < 0.01 (versus WT undifferentiation); **, p < 0.01 (versus WT differentiation); #, p < 0.05 (versus WT differentiation) (±S.E.; n = 3). D, fatty-acid synthase (FAS) enzymatic activity of cells treated in A. ##, p < 0.01 (versus WT undifferentiation); ***, p < 0.001 (versus WT differentiation). E, PP5 is required for induction of adipogenic markers. qRT-PCR analysis of WT, PP5-KO, and rescued PP5-KO (KO-R) cells following differentiation (D) or undifferentiation (U) with DIIR mixture. #, versus WT undifferentiation ; *, versus WT differentiation ; ∧, versus KO differentiation (±S.E.; n = 6–9). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. The same parameters apply to # and symbols. HSL, hormone-sensitive lipase.

To investigate the underlying changes, qRT-PCR was performed on RNA extracted from the same set of differentiated and undifferentiated MEF cells. The data show elevated expression of seven adipogenic markers in treated WT cells (Fig. 2E). Interestingly, PP5-KO cells showed reduced expression of all seven markers, a pattern that was completely reversed in the PP5 rescued cells. In PP5-KO cells, the strongest repression was observed for PPARγ2, the fatty acid-binding protein aP2, the lipid-storing protein perilipin, and the fatty acid importer CD36. Less robust repression was seen for hormone-sensitive lipase, the glucose transporter Glut-4, and adiponectin. Interestingly, very high mRNA levels of the preadipocyte marker (Pref-1) were observed in treated PP5-KO cells. In WT MEF cells, GRα levels did not change with differentiation, but elevation of GRβ was observed. As the recently discovered mouse GRβ isoform appears to act as a dominant-negative inhibitor of GRα (41), we speculate that attenuation of GRα activity might be an essential aspect of adipogenesis, most likely in the later stages. Curiously, highly elevated expression of GRα was seen in differentiated PP5-KO cells that was decreased upon rescue of PP5 expression. This suggests that elevated expression of GRα may be contributing to the lipid-lean phenotype in the KO cells. Taken as a whole, these data, combined with the fatty-acid synthase activity results above, suggest that loss of PP5 disrupts most aspects of adipogenesis, including lipogenesis, lipid storage, lipid and glucose import, and adipocyte signaling.

Loss of PP5 Increases Antilipogenic Actions of Glucocorticoids

Because there are reports that PP5 acts as a negative regulator of GRα, we reasoned that elevated antilipogenic activity of GRα may contribute to the inability of PP5-KO cells to accumulate lipid. In many in vitro models of adipogenesis, Dex is typically used on the 1st day of treatment to promote early differentiation steps (42), but the preponderance of evidence suggests that GCs promote lipolysis over lipogenesis in the mature adipocyte (43–45). In our system, GRα activation could occur as the result of the single Dex treatment on the 1st day of induction through endogenous steroids in the serum or steroids produced in the cell. To test the former, Dex was excluded from the 1st day of the adipose-inducing regimen. As seen in Fig. 3, exclusion of Dex from the mixture did not block lipid accumulation in WT cells, showing that GCs are not important contributors to the lipogenic response in our system. Interestingly, exclusion of Dex did not reverse the lipid-lean phenotype in PP5-KO cells. Although this suggests that Dex-activated GRα does not contribute to the lipid-resistant state of PP5-KO cells, when Dex was added during the entire adipogenic process, greatly reduced lipid buildup was observed in WT cells and was even lower in KO cells. This demonstrates that GCs are indeed largely antilipogenic in adipocyte cells and that PP5 negatively regulates this process. Because protein kinase A (PKA) signaling is known to induce lipolysis in adipocytes (46), we reasoned that elevated PKA activity might explain the lipid-lean phenotype of PP5-KO cells. This was tested by treating WT and PP5-KO cells with H89 PKA inhibitor during adipogenic stimulation (Fig. 3A). Results show that PP5-KO cells retained low lipid content in the presence of H89. The inhibitor greatly increased total lipid content in WT cells, and it statistically increased content in the PP5-KO cells. However, it did not rescue lipid buildup in PP5-KO cells even to levels seen in control WT cells, suggesting that PP5 is not acting through PKA signaling. Taken as a whole, these observations are evidence that GRα is a contributor to the lipid-resistant state of PP5-KO cells but that other factors, most likely PPARγ, must also be involved.

FIGURE 3.

Role of dexamethasone in MEF cell adipogenesis. A, WT and PP5-KO MEF cells were treated with adipogenic mixture containing Dex on the 1st day of treatment (+Dex) or not containing Dex (−Dex) or with mixture containing Dex on each day of treatment (+Dex ET). Lipid accumulation was detected by Nile Red staining. To test for the involvement of PKA signaling, MEF cells were also exposed to H89 PKA inhibitor on each day of DIIR treatment (+H89 ET). B, direct biochemical measurement of intracellular lipid content in cells of A. *, versus WT same condition; #, versus WT +Dex; ∧, versus KO −Dex, ± S.E., n = 3. ## and ∧∧, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

Reciprocal Control of GRα and PPARγ by PP5

To directly test the roles of PP5 on GRα and PPARγ, transcriptional activities of each receptor were measured in WT and PP5-KO MEF cells (Fig. 4). In initial experiments, MEF cells were transfected with reporter genes. The results obtained demonstrated elevated Dex-induced GRα activity at the murine mammary tumor virus-luciferase construct in the KO cells (data not shown) but greatly reduced basal and rosiglitazone-induced PPARγ activity using a peroxisome proliferator response element-luciferase reporter in the same cells (see Fig. 6). Analysis of receptor levels by Western blotting (Fig. 4A) showed reduced levels of GRα in the PP5-KO cells but higher levels of PPARγ in the KO cells (see also Fig. 6). Taken together, the results show that loss of PP5 augmented GRα activity but diminished PPARγ despite opposite effects on receptor protein levels. Importantly, the results suggest that PP5 may regulate the balance of lipolysis and lipogenesis by reciprocally modulating the activities of the receptors.

FIGURE 4.

Reciprocal regulation of GRα and PPARγ activity by PP5. A, Western blot analysis of endogenously expressed GRα and transiently transfected PPARγ2 in WT and PP5-KO cells. B, absence of PP5 increases GRα activity at endogenous metabolic genes. Undifferentiated WT and PP5-KO MEF cells were treated with or without Dex for 2 h followed by qRT-PCR analysis of the indicated genes. #, WT versus WT; *, KO versus WT; , KO versus KO (±S.E.; n = 6–9). C, absence of PP5 decreases PPARγ activity at select metabolic genes. Undifferentiated WT and PP5-KO MEF cells transfected with PPARγ2 were treated with or without rosiglitazone (Rosi) for 2 h followed by qRT-PCR analysis of the indicated genes. #, WT versus WT; *, KO versus WT; , KO versus KO (± S.E.; n = 6–9). *, #, and , p < 0.05; ** and ##, p < 0.01; ***, ###, and , p < 0.001. GILZ, glucocorticoid-inducible leucine zipper; SGK, serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase; PEPCK, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase; Hes1, hairy enhancer of split; FAS, fatty-acid synthase; SREBP, sterol-responsive element-binding protein; PDK4, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-4.

FIGURE 6.

PP5 control of GRα and PPARγ phosphorylation. A, PP5 controls GRα phosphorylation at serines 212 and 234. Whole cell extracts of WT and PP5-KO MEF cells treated with or without Dex for 1 h were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies specific to serines 212, 220, and 234 of mouse GRα. FiGR antibody was used to detect total GRα. Quantitation of GRα bands was performed by infrared spectrophotometry. Phospho-GR (pGR) signals were normalized to total GR at each condition. #, WT versus WT; *, KO versus WT; , KO versus KO (±S.E.; n = 4). B, PP5 controls PPARγ phosphorylation at serine 112. Whole cell extracts of WT and PP5-KO MEF cells transfected with wild-type PPARγ2 or S112A mutant were analyzed by Western blotting with antibody specific to serine 112 or antibody against total PPARγ. Prior to harvest, cells were untreated (C) or treated with tetradecanoylphorbol acetate (TPA) or rosiglitazone (Rosi). Quantitation of PPARγ2 bands was performed by infrared spectrophotometry. Phospho-PPARγ signals were normalized to total PPARγ at each condition. #, WT versus WT; *, KO versus WT (±S.E.; n = 4). C, absence of PP5 does not reduce activity of the S112A-PPARγ2 mutant. WT and PP5-KO MEF cells transfected with wild-type PPARγ2 or S112A mutant were analyzed for rosiglitazone-induced reporter activity using peroxisome proliferator response element (PPRE)-luciferase (Luc) or by a qRT-PCR assay at the indicated endogenous genes. #, WT versus WT; *, KO versus WT (±S.E.; n = 6). D, the S112A-PPARγ2 mutant rescues lipid accumulation in PP5-KO cells. WT and PP5-KO MEF cells were transfected with wild-type PPARγ2 or S112A mutant followed by treatment with DIIR mixture and Nile Red staining for lipid content. Quantitation of lipid content is shown to the right. #, WT versus WT; *, KO versus WT; , KO versus KO (±S.E.; n = 3). E, the GR3A mutant increases lipid in WT but not PP5-KO cells. WT and PP5-KO MEF cells were transfected with the GR3A mutant followed by treatment with DIIR mixture and Nile Red staining for lipid content. Quantitation of lipid content is shown to the right. #, WT versus WT; *, KO versus WT (±S.E.; n = 3). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. The same parameters apply to # and ∧ symbols. PEPCK, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase.

As a more relevant test, qRT-PCR analysis was performed to determine the role of PP5 in the expression of endogenous metabolic genes controlled by each receptor. In response to Dex, GRα activity in the KO cells was greater at all genes tested (Fig. 4B). For some genes, elevated expression was seen under basal conditions, suggesting that the absence of PP5 causes derepression of ligand-bound and unbound GR. Interestingly, elevated basal and Dex-induced expression of PPARγ was observed in the KO cells. In theory, this should produce a heightened adipogenic state in the KO cells. But as seen below, even in the presence of PPARγ overexpression, the absence of PP5 effectively blocked PPARγ activation. In the cases of glucocorticoid-inducible leucine zipper and CD36, the elevated expression is consistent with the antilipogenic response seen in the KO cells. Glucocorticoid-inducible leucine zipper was recently shown to inhibit adipogenesis in mesenchymal cells (4), whereas the CD36 results demonstrate that PP5 loss can also increase GRα-mediated gene repression of this important lipid importer. In contrast, elevated expression of serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase should stimulate, rather than inhibit, adipogenesis as serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase was recently shown to promote differentiation and lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 cells (47). Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-4 is a metabolic gating protein that promotes gluconeogenesis in liver and glyceroneogenesis in adipose by preventing the shunting of pyruvate to de novo lipid synthesis (48–50).

In contrast to Dex treatment, PP5-KO MEF cells treated with rosiglitazone showed significantly reduced expression of some, but not all, PPARγ-regulated genes (Fig. 4C). Most notable was CD36, which showed dramatic reductions in both basal and ligand-induced expression. Reduced basal expression most likely reflects the ability of PP5 to control the ligand-independent activity of PPARγ or PPARγ that is activated by endogenous or serum-derived fatty acids. Indeed, phosphorylation of human PPARγ has been shown to inhibit both its ligand-dependent and -independent activities (25). Because CD36 was repressed by GRα but induced by PPARγ, the reciprocal nature of PP5 regulation on these receptors may result in near-maximal repression of its expression in the PP5-KO cells. This alone may be the single greatest contributor to reduced lipid content observed in the PP5-KO MEF cells (Fig. 2). However, other PPARγ-regulated genes were affected in the KO cells, such as phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, which promotes glyceroneogenesis in adipose (51), and hairy enhancer of split (HES1) a known repressor of lipogenic gene expression (52). Curiously, repression of HES1 by PPARγ in the WT cells was converted to activation in the KO cells, suggesting that PP5 may differentially regulate the transactivation versus transrepression properties of the receptor at some genes. In any case, the high level of HES1 in KO cells is also consistent with the lipid-lean phenotype of these cells. PP5 regulation of PPARγ appears to be gene-specific as no change in rosiglitazone-induced sterol-responsive element-binding protein-1c expression was seen in the absence of PP5.

Localization and Hormone-induced Translocation of GRα and PPARγ Are Not Affected by PP5

Hormone-induced nuclear translocation is an integral step in the activation of most nuclear receptors. In the case of GRα, circumstantial evidence suggests that PP5 may regulate this process as it can be bound by dynein, the motor protein of microtubule-based transport (53). Similarly, the cellular localization of PPARγ could be directly or indirectly controlled by PP5. As an initial test of this hypothesis, the localization of PP5 in MEF cells was determined by indirect immunofluorescence (Fig. 5A). Consistent with observations in other cell lines (15, 30), the majority of PP5 was perinuclear, suggesting a potential role in nuclear transport. The localization of receptors was determined by transfecting WT and PP5-KO MEF cells with GRα-GFP and PPARγ2-GFP expression constructs. GRα-GFP was localized to the cytoplasm under basal conditions and translocated to the nucleus with Dex treatment in both WT and PP5-KO cells (Fig. 5B). GRα-GFP imaging was consistent with fractionation analysis (data not shown). In contrast to GRα, inactive PPARγ2-GFP was primarily localized to the nucleus, although a small fraction was observed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5C). Treatment with rosiglitazone had no effect on the distribution in WT and PP5-KO cells. These results demonstrate that PP5 does not prevent or promote hormone-induced nuclear translocation of GRα or PPARγ2, suggesting that altered activities result from intrinsic functions of the promoter-occupied receptor, most likely due to changes in phosphorylation.

FIGURE 5.

PP5 does not regulate intracellular trafficking of GRα and PPARγ. A, localization of PP5 in WT and PP5-KO MEF cells by indirect immunofluorescence. B, localization of GRα-GFP in WT and PP5-KO cells treated with or without Dex for 1 h. C, localization of PPARγ-GFP in WT and PP5-KO cells treated with or without rosiglitazone (Rosi) for 1 h.

PP5 Regulates Phosphorylation States of GRα and PPARγ

To directly test whether PP5 controls the phosphorylation states of GRα and PPARγ, Western blot analyses were performed with phosphoserine antibodies specific to each receptor. In the case of GRα, hormone activation is known to cause elevated phosphorylation at serines 212, 220, and 234 (mouse sequence) in the AF-1 region of the protein (27, 28). Some studies report a positive correlation between phosphorylation status and hormone-induced transcriptional activity of the GRα (17, 54). In Fig. 6A, GRs from WT and PP5-KO cells treated with Dex were compared for phosphorylation status at serines 212, 220, and 234. In WT cells, Dex-induced phosphorylation was significantly increased at serines 220 and 234. In PP5-KO cells, hyperphosphorylation was observed at all three residues with the largest increases at serines 212 and 234. No increase of basal GRα phosphorylation in PP5-KO cells was observed. These results are strong evidence that GRα is a direct target of PP5 phosphatase activity and that the primary role of PP5 is to attenuate GRα action by preventing hyperphosphorylation.

Like GRα, PPARγ is also a phosphoprotein. However, most studies show that phosphorylation of PPARγ, especially by mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways, causes inhibition of its activity (55, 56). The best known target of mitogen signaling is serine 112 of mouse PPARγ2 (homologous to Ser-114 in humans), and a S112A mutation results in a receptor with elevated basal and ligand-induced adipogenic activity (57, 58). To determine whether PP5 dephosphorylates Ser-112, WT and PP5-KO cells were transfected with wild-type PPARγ2 and the S112A mutant. Western blot analysis with an antibody against Ser-112 showed significantly increased phosphorylation at Ser-112 for untreated and rosiglitazone-bound PPARγ2 (Fig. 6B). A trend of increased Ser-112 phosphorylation was also seen in PP5-KO cells treated with tetradecanoylphorbol acetate to activate phosphorylation cascades. Curiously, levels of total PPARγ2 protein (WT and S112A) were higher in the PP5-KO cells. Although we do not know the reason, elevated expression of PPARγ in PP5-KO cells can also be seen in Fig. 4; however, PPARγ activity levels were dramatically reduced.

PP5 Dephosphorylation of PPARγ Ser-112 Is Principal Determinant of Lipid Accumulation

The ability of PP5 to target Ser-112 was also tested by comparing activities of WT PPARγ2 and the S112A mutant following transfection of each receptor into WT and PP5-KO cells (Fig. 6C). Results show significantly reduced activity of WT PPARγ2 at a peroxisome proliferator response element-driven reporter gene in the PP5-KO cells. In contrast, the S112A mutant demonstrated elevated activity in the PP5-KO cells at the same reporter. Elevated S112A activity in the KO cells was also seen at two endogenous PPARγ-regulated genes, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and CD36, suggesting that the lipogenic potential of the PP5-KO cells might have been restored. This was directly tested by measuring lipid content following DIIR treatment (Fig. 6D). As expected, there was a trend of increased lipid content in WT cells transfected with the S112A mutant. More importantly, the inability of PP5-KO cells to accumulate lipid was completely reversed following S112A transfection, indicating that PP5 targeting of PPARγ at serine 112, rather than GR, might be the major determinant altering lipid accumulation in these cells. This was confirmed by analysis of a human GR mutant (GR3A) in which the three major serine phosphorylation sites 203, 211, and 226 (equivalent to mouse Ser-112, Ser-220, and Ser-234) were mutated to alanine. The GR3A mutant has reduced hormone-induced transcriptional activity (37, 59). In WT cells subjected to DIIR, expression of GR3A resulted in elevated lipid content, most likely due to dominant-negative inhibition of endogenous WT GR (see “Discussion”). However, only a small increase in lipid was seen in PP5-KO cells transfected with GR3A. Taken as a whole, these results show that abrogation of PPARγ activity was the dominant mechanism preventing lipid accumulation in the PP5-KO cells.

DISCUSSION

Growth and accumulation of adipose tissue are largely governed by the balance between lipolysis and lipogenesis, a process that is reciprocally regulated by glucocorticoids (1) and PPARγ receptors (2). Until now, it has been generally accepted that each of these opposing receptors acts independently to control lipid content in response to hormonal and dietary stimuli as intracellular factors controlling or modulating this reciprocity have been unknown. In this work, we identified protein phosphatase 5 as an intracellular fulcrum point in GRα- and PPARγ-mediated control of lipid metabolism. Cells deficient in PP5 expression were resistant to lipid accumulation in the face of adipogenic stimuli due to simultaneously elevated GRα and reduced PPARγ activities at genes controlling lipid metabolism. PP5 exerted this control by dephosphorylating each receptor at specific serine residues, a result that is consistent with the previously known ability of phosphorylation to increase GRα activity (23) while simultaneously decreasing PPARγ (56).

Because PP5 has many potential direct and indirect targets other than GRα and PPARγ (14), it was important to show that the lipid-resistant state of PP5-KO cells was directly attributable to one or both of these receptors. This was achieved through use of the S112A-PPARγ mutant, which completely reversed the fat-deficient phenotype in the KO cells (Fig. 6). Thus, not only was PPARγ activity controlled by PP5 at serine 112, it appeared to be the dominant target of PP5 actions to promote lipid accumulation in these cells. Although the triple serine to alanine mutant of GRα showed little to no ability to reverse the lipid-lean state of the KO cells (Fig. 6), for a variety of reasons, it is still likely that GRα lipolytic activity is controlled by PP5. For example, GRα-mediated repression of CD36 was much higher in the KO cells (Fig. 4) as was the ability of Dex to stimulate lipid loss (Fig. 3). In addition, expression of GR3A, which has intrinsically low transcriptional activity (37, 59), in WT cells caused elevated lipid levels (Fig. 6). The latter effect most likely results from dominant-negative suppression by GR3A of the lipolytic actions of endogenous GRα. Although the contribution of GR serine phosphorylation to adipogenesis has not been shown previously, the dominant-negative properties of GR3A and similar mutants have been documented in molecular assays. Precise mechanism aside, this result is further evidence that GRα phosphorylation at serines 212, 220, and 234 is needed for its lipolytic actions. Viewed from this perspective, it simply may be that the GR3A mutant cannot by itself rescue lipid accumulation in the KO cells because the overall lipid-importing and de novo synthesis properties of PPARγ are absent. In short, blockage of lipolysis by GR3A or any other means is meaningless in the absence of lipid.

Our results provide strong evidence that PP5 is critical to lipid accumulation in response to adipogenic stimuli; however, the exact lipometabolic pathways controlled by PP5 are still unclear. Gene profiling suggested that lipid import may be compromised as levels of CD36 and aP2, which rose dramatically during differentiation in WT cells, were extremely low in the KO cells. Consistent with this were higher levels of FFAs in the media of KO cells compared with WT. However, de novo synthesis capability also appears to be compromised as evidenced by direct measurement of reduced fatty-acid synthase enzymatic activity in the KO cells. Thus, it is likely that PP5 controls many aspects of lipid metabolism, the precise contribution of which will require dedicated measurements using lipid flux assays. Interestingly, PP5 may also control key differentiation steps of adipogenesis because levels of Pref-1 were extremely high in treated KO cells. Pref-1 is a preadipocyte marker that is completely suppressed upon differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells and can block differentiation of these cells upon overexpression (60). Although it is not clear why Pref-1 levels are low in untreated PP5-KO MEF cells, its dramatic rise in treated KO cells underscores how resistant these cells are to adipogenic stimulation.

PP5 is a member of the PPP serine/threonine-specific family of protein phosphatases that includes PP1 and PP2A (14, 61, 62). To date, all three of these phosphatases have been found to control GRα activity (17, 27, 28, 63), although only PP5 as demonstrated here appears to have an effect on GRα control of lipid metabolism. Within the PPP family, PP5 is unique because of the presence of TPR motifs for protein interaction. PP5 was the last member of the family to be discovered as it exhibits very low basal activity. Indeed, activation of PP5 activity requires binding of its TPR domain to Hsp90 and other client substrates. PP5 is also known to be bound and activated by polyunsaturated fatty acids (32, 33, 64). Thus, PP5 not only appears to play an essential role in the attenuation of phosphorylation pathways controlling GRα and PPARγ but may do so in response to intracellular free fatty acid content.

The PP5 interaction with GR has been known for some time (65). Our demonstration here of PP5 interaction with PPARγ is the first of its kind, although earlier work did provide indirect evidence when a TPR peptide derived from PP5 was shown to alter PPARγ and PPARα activities (21). Curiously, the PP5/PPARγ interaction was dependent on rosiglitazone activation and was highly transient. We do not yet know the consequence of these kinetics, but they are similar to the rapid, hormone-induced swapping of FKBP52 for FKBP51 seen in both GR (39, 66) and mineralocorticoid receptor (67) complexes. Thus, it might be that other TPR proteins take the place of PP5 before or after its interaction with PPARγ.

Acute stimulation of adipocyte lipolysis is typically regulated by catecholamine binding of adrenergic receptors and stimulation of cAMP-induced phosphorylation cascades mediated by PKA (46, 68). Several targets of this PKA action have been identified, including perilipin, which is down-regulated, and hormone-sensitive lipase, which is activated. Recently, GCs have been found to indirectly facilitate adrenergic lipolysis by down-regulating expression of cAMP phosphodiesterase 3B, leading to elevated cAMP levels and PKA activity (45). For these reasons, we speculated that loss of PP5 activity might contribute to lipolysis either by promoting GR-mediated repression of phosphodiesterase 3B or by loss of function at direct targets, such as hormone-sensitive lipase, leading to hyperphosphorylation and elevated activity. The former possibility was tested by treating PP5-KO cells with the PKA inhibitor H89, which elevated lipid levels in WT cells as expected but which only had a small effect in the KO cells. Thus, increased PKA activity does not appear to be a major mechanism contributing to the lipid-resistant state of PP5-KO cells. Although we cannot at present exclude a direct effect of PP5 on lipid-regulating proteins, our results with the S112A-PPARγ mutant suggest that this is the major mechanism.

In our studies, we showed that PP5 acts as a negative regulator of GRα activity at the genes tested. These observations are in good agreement with studies by Honkanen and co-workers (17, 26) using antisense knockdown of PP5, which demonstrated increased transcriptional activity of GRα and increased GC-mediated growth arrest. Studies by Garabedian and co-workers (27) and Goleva and co-workers (28) using PP5 siRNA also found elevated phosphorylation of GRα; however, GRα activity was reduced rather than increased. It should be noted that the study by Garabedian and co-workers (27) showed reduced GRα activity at three genes not tested in our study and no effect on a fourth, glucocorticoid-inducible leucine zipper, which we found to be up-regulated with PP5 loss. Thus, it is likely that PP5 exerts gene-specific control on GRα and other nuclear receptors in much the same way as serine-specific phosphorylation of GR also controls subsets of genes (59, 69).

Until this study, no phosphatase that specifically targets PPARγ had been identified. At this late date, this observation is somewhat surprising. Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 has been shown to dephosphorylate PPARα (70), and rosiglitazone-activated PPARγ can up-regulate mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 expression (71). To the best of our knowledge, mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 actions on PPARγ have yet to be reported. Because phosphorylation inhibits PPARγ but has a positive effect on PPARα (72), it is possible that mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 up-regulation is the mechanism by which PPARγ antagonizes the actions of PPARα. With this is mind, it will be interesting to see whether PP5 also targets PPARα to decrease its activity. Future studies will also determine whether PP5 targets the newly discovered Ser-273 phosphorylation site of PPARγ (73). Ser-273 phosphorylation increases with obesity due to elevated cyclin-dependent kinase-5 activity in adipose tissue. Interestingly, altered Ser-273 phosphorylation does not change the lipid-promoting activity of PPARγ but reduces other responses, such as adiponectin secretion. Thus, it is not likely that the lipid-lean phenotype observed in PP5-KO cells is due to elevated phosphorylation of Ser-273.

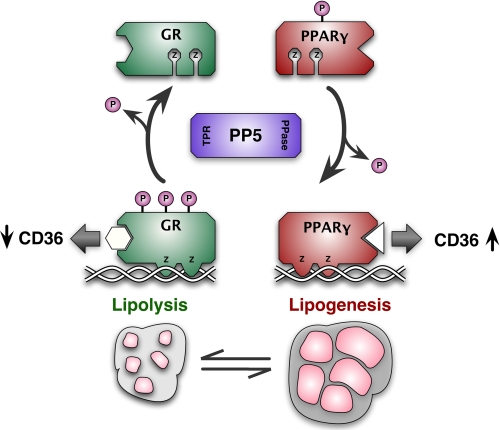

In summary, we identified protein phosphatase 5 as a reciprocal modulator of GRα and PPARγ that serves to antagonize the antilipogenic actions of GRα while simultaneously promoting the adipogenic actions of PPARγ (Fig. 7). PP5 achieves this by selectively dephosphorylating GRα at serines 212 and 234, causing inhibition of GRα activity at genes, such as CD36. PP5 dephosphorylates PPARγ at serine 112, promoting its transcriptional activity at the prolipogenic genes CD36, aP2, and others. Thus, PP5 can be considered a prolipogenic phosphatase, making it a new candidate for the treatment of obesity. PP5 is becoming an attractive drug target (74, 75), and its specificity for polyunsaturated over saturated fatty acids suggests that the development of an inhibitory fatty acid analog is feasible.

FIGURE 7.

PP5 serves as fulcrum in lipogenesis-lipolysis equilibrium by reciprocally modulating GRα and PPARγ. PP5 is a reciprocal modulator of GRα and PPARγ that antagonizes the antilipogenic actions of GRα while simultaneously promoting the lipogenic actions of PPARγ. PP5 achieves this by selectively dephosphorylating GR at serines 212 and 234, causing inhibition of GRα activity at genes, such as CD36. PP5 dephosphorylates PPARγ at serine 112, promoting its transcriptional activity at prolipogenic genes, for example CD36. PPase, phosphatase.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Jack Bodwell (Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, NH) and Michael Chinkers (University of South Alabama College of Medicine, Mobile, AL) for the gifts of GR and PP5 antibodies, respectively, and Dr. Mitch Lazar for the gift of S112A mutant PPARγ. We are especially indebted to Dr. Michael J. Garabedian (New York University School of Medicine) for the gift of phosphospecific antibodies to GR and the GR3A mutant and for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK70127 (to E. R. S.), DK73402 (to W. S.), DK054254 and DK083850 (to S. M. N.), and F31DK84958, a national research service award (to T. D. H.).

- GC

- glucocorticoid

- GR

- glucocorticoid receptor

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- PP

- protein phosphatase

- TPR

- tetratricopeptide repeat

- FKBP

- FK506-binding protein

- Dex

- dexamethasone

- DIIR

- Dex, insulin, isobutylmethylxanthine, and rosiglitazone

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR.

REFERENCES

- 1. Vegiopoulos A., Herzig S. (2007) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 275, 43–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lehrke M., Lazar M. A. (2005) Cell 123, 993–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Slavin B. G., Ong J. M., Kern P. A. (1994) J. Lipid Res. 35, 1535–1541 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shi X., Shi W., Li Q., Song B., Wan M., Bai S., Cao X. (2003) EMBO Rep. 4, 374–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sugden M. C., Holness M. J. (2006) Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 112, 139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koliwad S. K., Kuo T., Shipp L. E., Gray N. E., Backhed F., So A. Y., Farese R. V., Jr., Wang J. C. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 25593–25601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Spiegelman B. M. (1998) Diabetes 47, 507–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lefterova M. I., Lazar M. A. (2009) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 20, 107–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. White U. A., Stephens J. M. (2010) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 318, 10–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pratt W. B., Toft D. O. (1997) Endocr. Rev. 18, 306–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smith D. F., Toft D. O. (2008) Mol. Endocrinol. 22, 2229–2240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith D. F. (2004) Cell Stress Chaperones 9, 109–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Davies T. H., Sánchez E. R. (2005) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 37, 42–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hinds T. D., Jr., Sánchez E. R. (2008) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 40, 2358–2362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Banerjee A., Periyasamy S., Wolf I. M., Hinds T. D., Jr., Yong W., Shou W., Sanchez E. R. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 10471–10480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wolf I. M., Periyasamy S., Hinds T., Jr., Yong W., Shou W., Sanchez E. R. (2009) J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 113, 36–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zuo Z., Urban G., Scammell J. G., Dean N. M., McLean T. K., Aragon I., Honkanen R. E. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 8849–8857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reynolds P. D., Ruan Y., Smith D. F., Scammell J. G. (1999) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 84, 663–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Denny W. B., Valentine D. L., Reynolds P. D., Smith D. F., Scammell J. G. (2000) Endocrinology 141, 4107–4113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sumanasekera W. K., Tien E. S., Turpey R., Vanden Heuvel J. P., Perdew G. H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 4467–4473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sumanasekera W. K., Tien E. S., Davis J. W., 2nd, Turpey R., Perdew G. H., Vanden Heuvel J. P. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 10726–10735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bodwell J. E., Webster J. C., Jewell C. M., Cidlowski J. A., Hu J. M., Munck A. (1998) J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 65, 91–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ismaili N., Garabedian M. J. (2004) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1024, 86–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hu E., Kim J. B., Sarraf P., Spiegelman B. M. (1996) Science 274, 2100–2103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adams M., Reginato M. J., Shao D., Lazar M. A., Chatterjee V. K. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 5128–5132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dean D. A., Urban G., Aragon I. V., Swingle M., Miller B., Rusconi S., Bueno M., Dean N. M., Honkanen R. E. (2001) BMC Cell Biol. 2, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang Z., Chen W., Kono E., Dang T., Garabedian M. J. (2007) Mol. Endocrinol. 21, 625–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang Y., Leung D. Y., Nordeen S. K., Goleva E. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 24542–24552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chinkers M. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 11075–11079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen M. X., McPartlin A. E., Brown L., Chen Y. H., Barker H. M., Cohen P. T. (1994) EMBO J. 13, 4278–4290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Becker W., Kentrup H., Klumpp S., Schultz J. E., Joost H. G. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 22586–22592 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kang H., Sayner S. L., Gross K. L., Russell L. C., Chinkers M. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 10485–10490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ramsey A. J., Chinkers M. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 5625–5632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yong W., Bao S., Chen H., Li D., Sánchez E. R., Shou W. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14690–14694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rangwala S. M., Rhoades B., Shapiro J. S., Rich A. S., Kim J. K., Shulman G. I., Kaestner K. H., Lazar M. A. (2003) Dev. Cell 5, 657–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang H. H., Huang J., Düvel K., Boback B., Wu S., Squillace R. M., Wu C. L., Manning B. D. (2009) PLoS One 4, e6189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang Z., Frederick J., Garabedian M. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 26573–26580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Najjar S. M., Yang Y., Fernström M. A., Lee S. J., Deangelis A. M., Rjaily G. A., Al-Share Q. Y., Dai T., Miller T. A., Ratnam S., Ruch R. J., Smith S., Lin S. H., Beauchemin N., Oyarce A. M. (2005) Cell Metab. 2, 43–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Davies T. H., Ning Y. M., Sánchez E. R. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 2030–2038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wolins N. E., Quaynor B. K., Skinner J. R., Tzekov A., Park C., Choi K., Bickel P. E. (2006) J. Lipid Res. 47, 450–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hinds T. D., Jr., Ramakrishnan S., Cash H. A., Stechschulte L. A., Heinrich G., Najjar S. M., Sanchez E. R. (2010) Mol. Endocrinol. 24, 1715–1727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gregoire F. M., Smas C. M., Sul H. S. (1998) Physiol. Rev. 78, 783–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Caprio M., Fève B., Claës A., Viengchareun S., Lombès M., Zennaro M. C. (2007) FASEB J. 21, 2185–2194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Campbell J. E., Fediuc S., Hawke T. J., Riddell M. C. (2009) Metabolism 58, 651–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Xu C., He J., Jiang H., Zu L., Zhai W., Pu S., Xu G. (2009) Mol. Endocrinol. 23, 1161–1170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Carmen G. Y., Víctor S. M. (2006) Cell. Signal. 18, 401–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Di Pietro N., Panel V., Hayes S., Bagattin A., Meruvu S., Pandolfi A., Hugendubler L., Fejes-Tóth G., Naray-Fejes-Tóth A., Mueller E. (2010) Mol. Endocrinol. 24, 370–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sugden M. C., Holness M. J. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 284, E855–E862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nye C., Kim J., Kalhan S. C., Hanson R. W. (2008) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 19, 356–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wan Z., Thrush A. B., Legare M., Frier B. C., Sutherland L. N., Williams D. B., Wright D. C. (2010) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 299, C1162–C1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tontonoz P., Hu E., Devine J., Beale E. G., Spiegelman B. M. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 351–357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Herzig S., Hedrick S., Morantte I., Koo S. H., Galimi F., Montminy M. (2003) Nature 426, 190–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Galigniana M. D., Harrell J. M., Murphy P. J., Chinkers M., Radanyi C., Renoir J. M., Zhang M., Pratt W. B. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 13602–13610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zuo Z., Dean N. M., Honkanen R. E. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 12250–12258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lazar M. A. (2005) Biochimie 87, 9–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Burns K. A., Vanden Heuvel J. P. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1771, 952–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Camp H. S., Tafuri S. R. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 10811–10816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Camp H. S., Tafuri S. R., Leff T. (1999) Endocrinology 140, 392–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chen W., Dang T., Blind R. D., Wang Z., Cavasotto C. N., Hittelman A. B., Rogatsky I., Logan S. K., Garabedian M. J. (2008) Mol. Endocrinol. 22, 1754–1766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Smas C. M., Sul H. S. (1993) Cell 73, 725–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chinkers M. (2001) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 12, 28–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Golden T., Swingle M., Honkanen R. E. (2008) Cancer Metastasis Rev. 27, 169–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. DeFranco D. B., Qi M., Borror K. C., Garabedian M. J., Brautigan D. L. (1991) Mol. Endocrinol. 5, 1215–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chen M. X., Cohen P. T. (1997) FEBS Lett. 400, 136–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Chen M. S., Silverstein A. M., Pratt W. B., Chinkers M. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 32315–32320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Davies T. H., Ning Y. M., Sánchez E. R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 4597–4600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Galigniana M. D., Erlejman A. G., Monte M., Gomez-Sanchez C., Piwien-Pilipuk G. (2010) Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 1285–1298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Londos C., Brasaemle D. L., Schultz C. J., Adler-Wailes D. C., Levin D. M., Kimmel A. R., Rondinone C. M. (1999) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 892, 155–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Blind R. D., Garabedian M. J. (2008) J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 109, 150–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Vanden Heuvel J. P., Kreder D., Belda B., Hannon D. B., Nugent C. A., Burns K. A., Taylor M. J. (2003) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 188, 185–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jan H. J., Lee C. C., Lin Y. M., Lai J. H., Wei H. W., Lee H. M. (2009) Cancer Lett. 277, 141–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Shalev A., Siegrist-Kaiser C. A., Yen P. M., Wahli W., Burger A. G., Chin W. W., Meier C. A. (1996) Endocrinology 137, 4499–4502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Choi J. H., Banks A. S., Estall J. L., Kajimura S., Boström P., Laznik D., Ruas J. L., Chalmers M. J., Kamenecka T. M., Blüher M., Griffin P. R., Spiegelman B. M. (2010) Nature 466, 451–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Swingle M., Ni L., Honkanen R. E. (2007) Methods Mol. Biol. 365, 23–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ni L., Swingle M. S., Bourgeois A. C., Honkanen R. E. (2007) Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 5, 645–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]