Abstract

Background

Despite the large number of studies on the recurrence after surgery for equinus foot deformity in cerebral palsy (CP) patients, only a few investigations have reported long-term recurrence rates. Furthermore, little is known on the interval between the recurrent surgeries and the factors that lead to early recurrence. This study aimed to assess the overall recurrence after surgery for equinus foot deformity in patients with CP and to assess the factors associated with recurrence. We also aimed to determine the predisposing factors for early recurrence.

Methods

The medical records of 186 patients (308 feet) were reviewed in order to determine the recurrence after surgery for equinus foot deformity. The type of CP, type of surgery, age at surgery, functional mobility, passive dorsiflexion of the ankle at the last follow-up visit, and subsequent treatment were recorded. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was employed, with the end point defined as reoperation.

Results

The mean age at surgery was 6.8 ± 2.5 years (range, 2.2–13.1). With the mean follow-up period of 11.3 years (range, 7.2–17.7), the overall recurrence rate was 43.8%. The recurrence rate was highest among patients with hemiplegia (62.5%). The Kaplan–Meier survival without repeat surgery estimate was shown to be 88.6% at 5 years and 59.6% at 10 years. Among children with hemiplegia and diplegia, the younger children (≤8 years of age) showed a higher rate of recurrence compared with the older children (P = 0.04 and P = 0.01, respectively). In 41 feet (30.4%), reoperations were performed within 5 years after the primary surgery. Early recurrence was most prevalent among children with hemiplegia (50.0%). In children with diplegia and quadriplegia, the younger children underwent the secondary operation later than the older children (P = 0.04 and P = 0.02, respectively).

Conclusion

Recurrence after surgery for equinus foot deformity is common and the age at surgery has a significant influence on recurrence. Recurrence can occur at any age while the child is still growing; therefore, it is advised to follow those patients until they reach skeletal maturity.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Keywords: Equinus deformity, Recurrence, Cerebral palsy

Introduction

Equinus foot deformity, caused by contracture of the triceps surae, is one of the most common deformities seen in patients with cerebral palsy (CP), with a direct impact on standing ability and gait [1–5]. The goal of treatment for the equinus deformity is to improve the gait in ambulatory patients and to achieve a plantigrade foot that enhances standing ability in non-ambulatory patients. Treatment modalities for equinus deformity consist of non-operative methods such as stretching the contracted tissue through serial casting, physical therapy, brace management, injection of botulinum toxin, and, finally, surgical lengthening of the triceps surae if the equinus deformity persists [4, 5]. Although the goal in equinus surgery is to obtain a plantigrade foot and improve gait and standing function, there is also a great fear of overcorrection to hyperdorsiflexion, leading to progressive crouch [6, 7].

Recurrence of the deformity after surgical treatment is common and the outcomes after surgical intervention has been widely reported [8–14]. The reported rate of recurrence after surgical treatment varies from 6 to 54% [13, 15–18]. Suggested risk or predisposing factors associated with the recurrence of equinus deformity include the age at the time of surgery, type of CP, type of surgery, and gender [16, 19–23]. Among these factors, the patient’s age at the time of surgery has been considered as the most important predisposing factor for recurrence. Several studies have shown that children who are younger at the time of surgery have a higher rate of recurrence [8, 13, 16]. Despite the large number of studies on the outcome of surgery for equinus foot deformity, only a few studies have evaluated the long-term outcome. However, longer-term follow-up is essential because the recurrence of equinus deformity may require 5 or more years to become evident and some studies have shown that the final results of equinus correction could not be evaluated until the child has reached skeletal maturity [20, 24, 25]. In addition, little is known about the interval between the recurrent surgeries and the factors that lead early recurrence.

The purpose of this study was to assess the rate of recurrence after surgery for equinus foot deformity in CP patients and to assess the risk factors associated with recurrence. We also aimed to determine the predisposing factors that lead to early recurrence.

Materials and methods

Approval was obtained from our institutional review board for this retrospective study. From 1988 to 1998, 282 consecutive patients with CP had surgery for equinus deformity correction. We included the patient if the index surgery occurred before 14 years of age, if there was no previous surgery on the calf, and there was a minimum of 7 years of clinical follow-up. With these restrictions, our final sample size was 186 patients (308 feet). Medical records were reviewed to determine the type of CP, sex, age at the index surgery, type of equinus surgery, ambulatory status, and subsequent treatment. We had 72 patients who did not have the minimal 7-year follow-up. It is likely that there were a few patients who did not want further surgery when it was indicated and moved to another doctor or stopped seeing a doctor. The type of CP was assigned at each visit and the last clinical evaluation was used for categorization in this study. Patients were assigned the diagnosis of hemiplegia if they had unilateral involvement, diplegia if there was bilateral involvement allowing independent ambulation with or without an assistive device gait, and quadriplegia if there was bilateral involvement and independent gait was not possible. Functional mobility was retrospectively classified based on medical record review using Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) [26] criteria for 6–12-year-olds, since the 12–18-year-olds criteria were not published at the time of this record review.

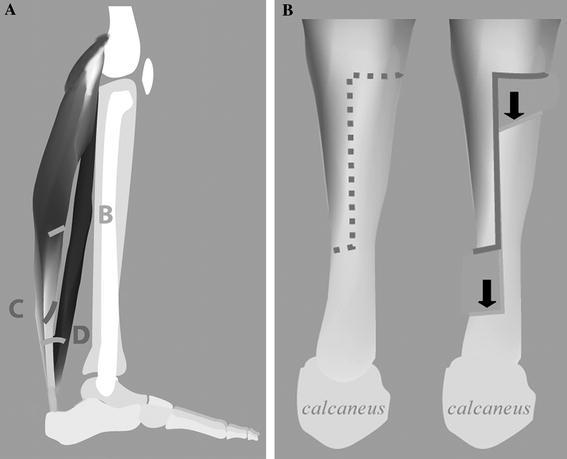

During this treatment period, all patients had the surgery performed by one surgeon who also did all of the clinical follow-up. Most patients were seen for a clinical outpatient evaluation by the surgeon every 6–12 months. During this visit, the range of motion of the ankle joint was always recorded in both knee-extended and knee-flexed positions. Ankle dorsiflexion is recorded with the subtalar joint in neutral or as close as possible. The indications for surgery were made on initial clinical evaluation and those with functional ambulation also having a diagnostic gait analysis to assist in making the final surgical plan. The surgical plan followed current indications for multi-level surgery, with the vast majority of the children also having hamstring lengthening for increased stance knee extension, as well as torsional malalignment corrections, and correction of foot deformities. The surgery was indicated when a fixed equinus deformity interfered with walking, standing ability, or wearing an orthosis. Surgical procedures were performed using one of two techniques, namely, gastrocnemius recession (GR), in which the fascia of the gastrocnemius was transected or a tendo-Achilles lengthening (TAL), in which there was an open exposure of the Achilles tendon and a step-cut was made, followed by a sliding lengthening, which was then repaired with a suture. Specifically, GR was indicated in patients who had dorsiflexion limitation of less than neutral with the knee fully extended, but passive dorsiflexion to at least neutral with the knee flexed. All gastrocnemius surgeries were performed open, with the level of the lengthening chosen by the degree of gastrocnemius and soleus contracture. The GR was performed through an incision at the posterior medial border of the calf. By visual inspection, the outline of the distal end of the gastrocnemius is identified. The incision was carried through the subcutaneous tissue and the fascia overlying the gastrocnemius was identified. The interval between the gastrocnemius and soleus was identified and explored to its lateral border. For patients with early plantarflexion moments on gait analysis and maximum dorsiflexion on physical examination of less than −10° of dorsiflexion (i.e., 10° plantarflexion) with the knee extended, only the fascia of the gastrocnemius was lengthened. If there was more contracture of the gastrocnemius than −10° of dorsiflexion with the knee extended but no soleus contracture defined as at least 10° of dorsiflexion with the knee flexed, then a complete release of the gastrocnemius tendon from the soleus was performed. If there was more soleus contracture between 10° and −10° of dorsiflexion with the knee flexed, myofascial lengthening of the conjoined gastrocsoleus tendon was performed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

a This figure of the lateral aspect of the plantarflexors illustrates the level of the gastrocnemius lengthening with level B showing the gastrocnemius fascia-only level, level C shows the complete gastrocnemius release from the soleus, and level D shows the fascial release of the conjoint tendon. b The open sliding lengthening is demonstrated

TAL was indicated in patients with severe contractures involving the soleus, in which the maximum dorsiflexion was less than −10° of dorsiflexion (i.e., 10° of plantarflexion) with the knee flexed. All TALs were open Z-plasty technique with careful repair at −10° of dorsiflexion. The incision was made in the medial aspect just anterior to the bulk of the Achilles tendon. The incision was carried down to the subcutaneous tissue by sharp dissection into the peritenon of the Achilles tendon. A longitudinal cut was made through the midsubstance of the Achilles tendon over 3–4 cm, with the distal end detached medially if the child has varus tendency and laterally if the child has valgus tendency. The contralateral side was detached proximally. The tendon was allowed to slide into lengthening and was repaired with a running, absorbable suture.

In 71 feet, additional procedures were performed on the foot to correct either equinovarus (43 feet) or planovalgus (28 feet) deformity. All patients, regardless of the associated procedures, were placed in weight-bearing short-leg casts, with neutral ankle position for TAL and 10° dorsiflexion for all myofascial lengthenings, and instructed to bear weight and walk as soon as pain allowed. The night time knee extension splinting was prescribed to place stretch on the gastrocnemius for the duration of cast wear, usually 4–5 weeks. Following the cast removal, children were prescribed physical therapy, encouraged to walk as tolerated with regular sneakers, and were evaluated by the surgeon 3 to 4 weeks after cast removal for a decision on the orthotic needs.

A total of 575 additional procedures were performed in 251 limbs concurrently on other sites. The additional procedures include: hamstring lengthenings (194), adductor tenotomies (117), rectus femoris transfer (98), psoas lengthening (77), femoral derotational osteotomies (62), tibial derotational osteotomies (17), and others (10). The equinus deformity was considered to have recurred when there was a sufficient limitation of ankle dorsiflexion and gait dysfunction based on clinical evaluation to require a second operation for which the same indications for surgery were used as for the primary procedure. If the deformity recurred within 5 years after the primary surgery, we classified it as early recurrence.

Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test were used to assess the independence in the categorical variables, while the t-test was used to compare mean differences in the continuous variables. All tests were two-tailed, with 0.05 as the significance level. Kaplan–Meier survival estimate was utilized, with the end point defined as reoperation to determine the overall recurrence. STATA version 10.0 statistical software (STATA Corp., College Station, TX) was used for the analysis of the data.

Results

There were 308 feet in 186 patients. The mean age at surgery was 6.8 ± 2.5 years (range, 2.2–13.1), with male predominance (63.4%). Of the 308 feet, there was a recurrence in 135 (43.8%). Within the recurrence group, there were 41 feet (30.4%) in the early versus 94 feet (69.6%) in the later recurrence groups. The mean age at the second surgery was 13.1 ± 3.1 years (range, 7.0–20.3), while the mean interval between the primary and the second surgery was 6.9 ± 2.8 years (range, 1.8–15.0). The mean age at the last follow-up was 18.1 ± 2.5 years (range, 11.5–21.0). Of the 186 patients, 145 patients (78.0%) were over 16 years of age at the final follow-up, indicating that they likely were at skeletal maturity at the time of final follow-up visit. The mean passive dorsiflexion of the ankle at the last visit was 6.1 ± 9.1° (range, −10.0 to 28.0) with the knee extended and 14.4 ± 6.4° (range, −10.0 to 36.0) with the knee flexed.

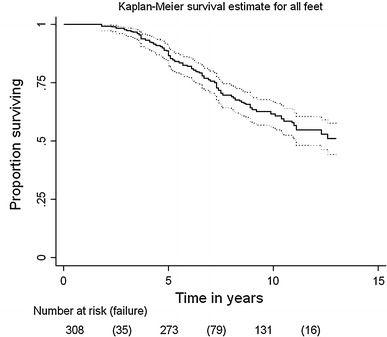

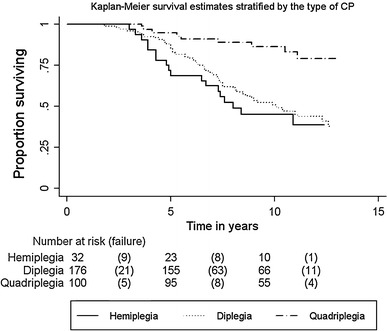

The overall rate of recurrence was 43.8%. The recurrence rate was highest among the patients with hemiplegia (62.5%), followed by diplegia (55.7%), and quadriplegia (17.0%). The Kaplan–Meier survival estimate was shown to be 88.6% at 5 years and 59.6% at 10 years not needing repeat surgery (Fig. 2). The estimate was shown to be 71.9% at 5 years and 43.8% at 10 years not requiring repeat surgery in patients with hemiplegia, 88.1% at 5 years and 49.0% at 10 years in patients with diplegia, and 95.0% at 5 years and 85.4% at 10 years in patients with quadriplegia not needing repeat surgery (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimate for all feet. The estimate was shown to be 88.6% at 5 years and 59.6% at 10 years until repeat surgery. The upper curve represents the upper 95% confidence limit, while the lower curve represents the lower confidence limit

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimate stratified by the type of cerebral palsy (CP). The estimate was shown to be 71.9% at 5 years and 43.8% at 10 years until repeat surgery in patients with hemiplegia, 88.1% at 5 years and 49.0% at 10 years in patients with diplegia, and 95.0% at 5 years and 85.4% at 10 years in patients with quadriplegia

Among children with hemiplegia, 20 feet (62.5%) underwent a second operation at the mean age of 12.3 ± 3.6 years (range, 7.4–20.3). The mean interval between the two surgeries was 6.6 ± 3.4 years (range, 3.0–15.0). The mean passive dorsiflexion of the ankle at the last follow-up was 5.4 ± 8.8° (range, −10 to 20) with the knee extended and 10.4 ± 8.6° (range, 0–28) with the knee flexed. The children who were 8 years and younger at the time of surgery had a higher rate of recurrence compared to the children who were older than 8 years (P = 0.04). The patients who underwent simultaneous surgery for varus foot correction had a lower rate of recurrence (P = 0.01). Ninety-eight of 176 feet (55.7%) underwent a second operation in children with diplegia. The mean interval between the two surgeries was 7.0 ± 2.7 years (range, 1.8–15.0) and the mean age at the second operation was 13.3 ± 3.0 years (range, 7.3–19.5). The mean passive ankle dorsiflexion at the last visit was 4.6 ± 8.9° (range, −10 to 30) with the knee extended and 13.3 ± 9.4° (range, −10 to 34) with the knee flexed. Similarly to the patients with hemiplegia, the younger children had a higher rate of recurrence compared to the older children in patients with diplegia (P = 0.01). Seventeen of 100 feet (17.0%) underwent a second operation in children with quadriplegia. The mean interval between the two surgeries was 6.8 ± 2.8 years (range, 3.6–11.1) and the mean age at the second operation was 12.9 ± 3.0 years (range, 7.0–16.7). The mean passive ankle dorsiflexion of the ankle at the last visit was 9.4 ± 9.6° (range, −10.0 to 30.0) with the knee extended and 17.8 ± 10.5 (range, −5.0 to 36.0) with the knee flexed. In contrast to the patients with hemiplegia and diplegia, the age at surgery was not a factor that characterizes recurrence risk in patients with quadriplegia (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the children who underwent surgery for equinus foot deformity stratified by the type of cerebral palsy (CP)

| Variables | Hemiplegia | Diplegia | Quadriplegia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurred | Non-recurred | P-value | Recurred | Non-recurred | P-value | Recurred | Non-recurred | P-value | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Sex | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.94 | ||||||

| Male | 12 (57.1) | 9 (42.9) | 63 (53.9) | 54 (46.2) | 10 (17.2) | 48 (82.8) | |||

| Female | 8 (72.7) | 3 (27.3) | 35 (59.3) | 24 (40.7) | 7 (16.7) | 35 (83.3) | |||

| Functional mobility | 1.0 | 0.08 | 0.35 | ||||||

| GMFCS I/II | 19 (61.3) | 12 (38.7) | 21 (44.7) | 26 (55.3) | – | – | |||

| GMFCS III/IV | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 77 (59.7) | 52 (40.3) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (100.0) | |||

| GMFCS V | – | – | – | – | 17 (18.7) | 74 (81.3) | |||

| Type of surgery | 0.34 | 0.58 | 0.87 | ||||||

| TAL | 18 (66.7) | 9 (33.3) | 35 (53.0) | 31 (47.0) | 10 (17.5) | 47 (82.5) | |||

| GR | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | 63 (57.3) | 94 (42.7) | 7 (16.3) | 36 (83.7) | |||

| Age at surgery | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.30 | ||||||

| ≤8 years | 18 (72.0) | 7 (28.0) | 81 (61.4) | 51 (38.6) | 14 (19.4) | 58 (80.6) | |||

| >8 years | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) | 17 (38.6) | 27 (61.4) | 3 (10.7) | 25 (89.3) | |||

| Concurrent surgery | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.39 | ||||||

| No | 12 (75.0) | 4 (25.0) | 13 (44.8) | 16 (55.2) | 1 (8.3) | 11 (91.7) | |||

| Yes | 8 (50.0) | 8 (50.0) | 85 (57.8) | 62 (42.2) | 16 (18.2) | 72 (81.8) | |||

| Varus/valgus | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.53 | ||||||

| Equinovarus | 2 (25.0) | 6 (75.0) | 15 (62.5) | 9 (37.5) | 2 (18.2) | 9 (81.8) | |||

| Equinus | 18 (75.0) | 6 (25.0) | 76 (57.6) | 56 (42.4) | 15 (18.5) | 66 (81.5) | |||

| Planovalgus | – | – | 7 (35.0) | 13 (65.0) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (100.0) | |||

n the numbers are given as the number of limbs and not the patients; TAL tendo-Achilles lengthening; GR gastrocnemius recession; Varus/valgus surgery for varus or valgus foot correction

Evaluating the impact of gait function was done by segmenting children by GMFCS level into three groups, I–II, III–IV, and V. Because gait function does not correlate to bilateral involvement (hemiplegia vs. diplegia) and this pattern separation was shown to be an important factor, we chose to analyze gait function by pattern segmentation. Because hemiplegics almost all have very good function (almost all were in group I–II) and all of the quadriplegics were group V, there was no ability to assess function independent of pattern. The children with diplegia were almost evenly spread between functional groups I–II and III–IV. There was a trend toward higher recurrence rate in group III–IV compared to group I–II; however, it was not significant (P = 0.08). There was no impact of age on recurrent surgery when segmented by pattern of involvement and gait function (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the children with recurrent equinus surgery

| Variables | Hemiplegia | Diplegia | Quadriplegia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | Later | P-value | Early | Later | P-value | Early | Later | P-value | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Sex | 0.36 | 0.73 | 0.31 | ||||||

| Male | 5 (41.7) | 7 (58.3) | 16 (25.4) | 47 (74.6) | 2 (20.0) | 8 (80.0) | |||

| Female | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | 10 (28.6) | 25 (71.4) | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | |||

| Functional mobility | 1.0 | 0.43 | – | ||||||

| GMFCS I/II | 9 (47.4) | 8 (52.6) | 7 (33.3) | 14 (66.7) | – | – | |||

| GMFCS III/IV | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 19 (24.7) | 58 (75.3) | – | – | |||

| GMFCS V | – | – | – | – | 5 (29.4) | 12 (70.6) | |||

| Type of surgery | 1.0 | 0.28 | 0.31 | ||||||

| TAL | 9 (50.0) | 9 (50.0) | 7 (20.0) | 28 (80.0) | 2 (20.0) | 8 (80.0) | |||

| GR | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 19 (30.2) | 44 (69.8) | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | |||

| Age at surgery | 0.47 | 0.04 | 0.02 | ||||||

| ≤8 years | 10 (55.6) | 8 (44.4) | 18 (22.2) | 63 (77.8) | 2 (14.3) | 12 (85.7) | |||

| >8 years | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 8 (47.1) | 9 (52.9) | 3 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Concurrent surgery | 0.36 | 0.76 | 0.29 | ||||||

| No | 5 (41.7) | 7 (58.3) | 3 (23.1) | 10 (76.9) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Yes | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | 23 (27.1) | 62 (72.9) | 4 (25.0) | 12 (75.0) | |||

| Varus/valgus | 0.47 | 0.82 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Equinovarus | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (20.0) | 12 (80.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | |||

| Equinus | 8 (44.4) | 10 (55.6) | 21 (27.6) | 55 (72.4) | 5 (33.3) | 10 (66.7) | |||

| Planovalgus | – | – | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) | |||||

n the numbers are given as the number of limbs and not the patients; TAL tendo-Achilles lengthening; GR gastrocnemius recession; Varus/valgus surgery for varus or valgus foot correction

Early recurrence was the most prevalent among patients with hemiplegia (50.0%). In children with diplegia and quadriplegia, who had the primary surgery before or at the age of 8 years tended to recur later than those who had the initial surgery after 8 years of age (P = 0.04 and P = 0.02, respectively; Table 2).

There were 10 feet in 10 patients (four hemiplegia, four diplegia, and two quadriplegia) who required a third plantarflexor lengthening (3.2%). The third procedure was performed in 12.5% of patients with hemiplegia, 2.3% of the patients with diplegia, and 2.0% of patients with quadriplegia. The mean age at the first surgery of these 10 patients was significantly lower than the patients who had only one or two operations (4.8 years versus 6.8 years, P = 0.002).

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study was designed to assess the recurrence rate and predisposing risk factors for recurrence after surgery for equinus foot deformity in children with CP. We have demonstrated a moderate rate of recurrence (43.8%) and found that the recurrence risk factors are age at primary surgery and pattern of CP. Patients with hemiplegia showed an overall increased risk of recurrence compared to the patients with diplegia or quadriplegia. This finding is clinically plausible due to the fact that most patients with quadriplegia are GMFCS V; as long as the foot is plantigrade in an orthosis, the equinus does not increase as fast and some mild equinus is well tolerated. The goal for hemiplegia and diplegia is to develop good plantarflexor strength without orthotics. Since the indication for surgical treatment considers both the actual degree of contracture and the functional impact of the contracture on the patient’s function, patients with quadriplegia develop less contracture and have less functional impact of mild or moderate equinus than those with hemiplegia, which explains part of the significantly different recurrent rates reported in this study. A similar explanation may apply to the patients with diplegia who are not as functional as the patients with hemiplegia; however, there was a trend toward higher recurrent rates in the less functional patients with GMFCS I–II versus II–IV. This suggests that there may be a fundamental difference between hemiplegia compared to diplegia. Patients with diplegia have a different response to growth, which we assessed here by chronologic age and not height directly, as they have a higher tendency to develop crouch gait, probably because they have an obligatory use of the impaired limb for non-protected weight-bearing, therefore stretching the gastrocsoleus with each step [4]. Patients with hemiplegia tend to reduce stance time and force requirement in the plegic limb as the weight increases, thereby, getting less stretch on the involved muscle and, more likely, recurrent contracture with growth [3, 4]. There may also be some still undefined neurologic impacts on the muscles that are different between hemiplegia and diplegia which explain the different recurrent rates.

In this study, younger children were more likely to have recurrence than older children. Other studies also have reported similar findings [8, 13, 16]; however, few studies have reported no relationship between the age at surgery and recurrence [9, 21, 27], although these studies have small patient numbers or relatively short durations of follow-up (2.1–7.0 years) [9, 21, 27]. Based on our findings and the published data, we feel that age is a factor in recurrence, with younger age of primary surgery increasing the risk of recurrent surgery. The need for surgery at a younger age likely indicates greater impact of growth discrepancy between the spastic muscle and the relatively normal bone growth, which is not affected by treatment but continues to be present throughout the child’s whole growth period, seems to be the most likely explanation for this age-related risk factor [16, 28].

The risk of recurrent contracture continues through adolescent growth, as demonstrated by the current rate in this study; therefore, the duration of follow-up is an important variable in determining the recurrence rate of equinus deformity. Saraph et al. [29] reported a 0% recurrence rate after Baumann’s procedure in 22 patients with diplegia and Cheng and So [30] reported a 5.6% recurrence rate after percutaneous TAL, most of whom were patients with diplegia and hemiplegia. The mean follow-up period in these studies was 2.2 and 2.7 years, respectively [29, 30]. However, several studies have indicated that the interval between equinus surgeries was approximately 4–5 years, although both longer and shorter times have been reported [20, 25, 28]. We have shown 88.6% survival (11.4% recurrence rate) at 5 years and 59.6% survival (40.4% recurrence rate) at 10 years. This finding implies that studies with shorter follow-up are likely to underestimate the recurrence rate.

Early recurrence was also the most prevalent in patients with hemiplegia. Our observation of early recurrence may also be explained in part by the natural history of progression of equinus foot pathology [1, 2, 4]. In patients with diplegia and some patients with quadriplegia, the feet tend to be in planovalgus and, hence, decreased early recurrence surgery compared with the patients with hemiplegia that appeared to be in equinovarus requiring earlier surgery to correct the deformity. In the varus foot, the equinus magnifies the varus deformity, while the planovalgus deformity compensates for the equinus contracture. Early recurrences were shown in our data to occur in older children with diplegia and quadriplegia. It is possible for younger children to remain stable after primary surgery until they reach the adolescent growth spurt. There may also be a tendency of the surgeon’s choice of procedures between TAL and GR leading to a skewing of early recurrence in older ambulatory children, although we found no difference in the recurrence rate between TAL and gastrocnemius lengthening. There is a much greater concern to avoid overcorrection, especially in diplegia in older children; therefore, there is a tendency to undercorrect the deformity in this population.

The limitations of this study include the retrospective cohort design used to assess the overall and early recurrence following primary surgery in CP patients with equinus foot deformity. Because of the retrospective design, we were not able to collect variables such as the Functional Motor Scale (FMS) to assess gait function, which might have allowed us to assess more risk factors associated with recurrence. Also, it is important to note that all of these cases were pre-operatively assessed and indicated for surgery and almost all have preoperative gait analysis, the same surgical treatment and rehabilitation, and the follow-up were all performed by the same surgeon. The bias of the surgeon was definitely toward conservative lengthening and the assessment for indicating the need for recurrent surgery was primarily based on clinical assessment, which was also the method for assessing overcorrection. Although this is evaluation method is subjective, we found no case of overlengthening by chart review. To fully assess objective recurrent equinus deformity as well as overcorrection, full follow-up gait studies are required. Because of our restrictions on funding, we are unable to routinely carry out full gait analysis unless we are using it for pre-operative planning. We were also not able to follow up 72 children who had a primary plantarflexor lengthening; these were patients who left the practice short of the minimal 7-year follow-up but were otherwise similar.

In summary, among CP patients diagnosed with equinus foot deformity who underwent primary gastrocsoleus lengthening surgery, the pattern of CP and the age at surgery have a significant influence on recurrence. The same factors (CP pattern and age at surgery) are significant predictors of early recurrence. Since recurrence tends to occur later in younger children compared to older children, it is advised to follow these patients until they reach skeletal maturity. Clinicians should be cautious in the interpretation and the utilization of these findings in decision-making regarding surgery for equinus foot deformity, since the primary goal of surgery is not to reduce the recurrence rate but to improve the patient’s function. It is within this context of improving the patient’s function and avoiding overcorrection that we would also like to reduce the surgical exposure rate by reducing recurrence. It is important to notify the family of this risk of recurrence and explain that it is not a failure of the treatment but should be part of the planned whole surgical treatment plan, which will not be concluded until the child’s growth is complete.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have received financial support for this study.

Footnotes

This study was conducted at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, DE, USA.

References

- 1.O’Connell PA, D’Souza L, Dudeney S, Stephens M. Foot deformities in children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;18:743–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennet GC, Rang M, Jones D. Varus and valgus deformities of the foot in cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1982;24:499–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1982.tb13656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wren TA, Rethlefsen S, Kay RM. Prevalence of specific gait abnormalities in children with cerebral palsy: influence of cerebral palsy subtype, age, and previous surgery. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:79–83. doi: 10.1097/00004694-200501000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller F. Cerebral palsy. New York: Springer Science & Business Media Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein M, Harper DC. Management of cerebral palsy: equinus gait. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43:563–569. doi: 10.1017/S0012162201001025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodda JM, Graham HK, Nattrass GR, Galea MP, Baker R, Wolfe R. Correction of severe crouch gait in patients with spastic diplegia with use of multilevel orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:2653–2664. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segal LS, Thomas SE, Mazur JM, Mauterer M. Calcaneal gait in spastic diplegia after heel cord lengthening: a study with gait analysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1989;9:697–701. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198911000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham HK, Fixsen JA. Lengthening of the calcaneal tendon in spastic hemiplegia by the White slide technique. A long-term review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:472–475. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.70B3.3372574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damron TA, Greenwald TA, Breed AL. Chronologic outcome of surgical tendoachilles lengthening and natural history of gastroc-soleus contracture in cerebral palsy. A two-part study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;301:249–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kay RM, Rethlefsen SA, Ryan JA, Wren TA. Outcome of gastrocnemius recession and tendo-achilles lengthening in ambulatory children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2004;13:92–98. doi: 10.1097/00009957-200403000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yngve DA, Chambers C. Vulpius and Z-lengthening. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16:759–764. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199611000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strecker WB, Via MW, Oliver SK, Schoenecker PL. Heel cord advancement for treatment of equinus deformity in cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 1990;10:105–108. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199001000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant AD, Feldman R, Lehman WB. Equinus deformity in cerebral palsy: a retrospective analysis of treatment and function in 39 cases. J Pediatr Orthop. 1985;5:678–681. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198511000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee CL, Bleck EE. Surgical correction of equinus deformity in cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1980;22:287–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1980.tb03707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banks HH, Green WT. The correction of equinus deformity in cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1958;40:1359–1379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rattey TE, Leahey L, Hyndman J, Brown DC, Gross M. Recurrence after Achilles tendon lengthening in cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:184–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craig JJ, van Vuren J. The importance of gastrocnemius recession in the correction of equinus deformity in cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1976;58:84–87. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.58B1.1270500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olney BW, Williams PF, Menelaus MB. Treatment of spastic equinus by aponeurosis lengthening. J Pediatr Orthop. 1988;8:422–425. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198807000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borton DC, Walker K, Pirpiris M, Nattrass GR, Graham HK. Isolated calf lengthening in cerebral palsy. Outcome analysis of risk factors. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:364–370. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B3.10827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharrard WJ, Bernstein S. Equinus deformity in cerebral palsy. A comparison between elongation of the tendo calcaneus and gastrocnemius recession. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1972;54:272–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sala DA, Grant AD, Kummer FJ. Equinus deformity in cerebral palsy: recurrence after tendo Achillis lengthening. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39:45–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb08203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phelps WM. Long-term results of orthopaedic surgery in cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1957;39:53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uyttendaele D, Kimpe E, Dellaert F, De Stoop N, Claessens H. Simple Z-lengthening of the Achilles tendon and Scholder procedure. Long-term follow-up and comparison of both methods. Acta Orthop Belg. 1984;50:213–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silver CM, Simon SD. Gastrocnemius-muscle recession (Silfverskiold operation) for spastic equinus deformity in cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1959;41-A:1021–1028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conrad JA, Frost HM. Evaluation of subcutaneous heel-cord lengthening. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1969;64:121–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, Russell D, Wood E, Galuppi B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39:214–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemperg R, Hagberg B, Lundberg A. Achilles tenoplasty for correction of equinus deformity in spastic syndromes of cerebral palsy. Acta Orthop Scand. 1969;40:507–519. doi: 10.3109/17453676909046536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Truscelli D, Lespargot A, Tardieu G. Variation in the long-term results of elongation of the tendo Achillis in children with cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1979;61:466–469. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.61B4.500758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saraph V, Zwick EB, Uitz C, Linhart W, Steinwender G. The Baumann procedure for fixed contracture of the gastrosoleus in cerebral palsy. Evaluation of function of the ankle after multilevel surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:535–540. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.82B4.9850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng JC, So WS. Percutaneous elongation of the Achilles tendon in children with cerebral palsy. Int Orthop. 1993;17:162–165. doi: 10.1007/BF00186378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]