Background: Gephyrin clusters inhibitory GABAA and glycine receptors at postsynaptic sites.

Results: GABAA and glycine receptor binding to gephyrin is a mutually exclusive process relying on distantly related sequence motifs.

Conclusion: Clustering of GABAA and glycine receptors is mediated by a shared binding site on gephyrin.

Significance: Gephyrin-dependent synaptic clustering of chloride-permeable ligand channels at synaptic sites relies on an evolutionarily conserved mechanism.

Keywords: GABA Receptors, Glycine Receptors, Protein-Protein Interactions, Scaffold Proteins, Synaptic Plasticity, Gephyrin, Postsynaptic Membrane, Receptor Clustering

Abstract

Gephyrin is the major protein determinant for the clustering of inhibitory neurotransmitter receptors. Earlier analyses revealed that gephyrin tightly binds to residues 398–410 of the glycine receptor β subunit (GlyR β) and, as demonstrated only recently, also interacts with GABAA receptors (GABAARs) containing the α1, α2, and α3 subunits. Here, we dissect the molecular basis underlying the interactions between gephyrin and GABAARs containing these α-subunits and compare them to the crystal structure of the gephyrin-GlyR β complex. Biophysical and biochemical assays revealed that, in contrast to its tight interaction with GlyR β, gephyrin only loosely interacts with GABAAR α2, whereas it has an intermediate affinity for the GABAAR α1 and α3 subunits. Despite the wide variation in affinities and the low overall sequence homology among the identified receptor subunits, competition assays confirmed the receptor-gephyrin interaction to be a mutually exclusive process. Selected gephyrin point mutants that critically weaken complex formation with GlyR β also abolished the GABAAR α1 and α3 interactions. Additionally, we identified a common binding motif with two conserved aromatic residues that are central for gephyrin binding. Consistent with the biochemical data, mutations of the corresponding residues within the cytoplasmic domain of α2 subunit-containing GABAARs attenuated clustering of these receptors at postsynaptic sites in hippocampal neurons. Taken together, our experiments provide key insights regarding similarities and differences in the complex formation between gephyrin and GABAARs compared with GlyRs and, hence, the accumulation of these receptors at postsynaptic sites.

Introduction

Gephyrin was initially discovered by co-purification with glycine receptors (GlyRs)2 (1) and was found to accumulate these receptors at postsynaptic sites by simultaneous binding of the GlyR β subunit (2–4) and elements of the cytoskeleton (5, 6). Gephyrin is a modular protein composed of an N-terminal domain (GephG, residues 1–181) followed by a presumably unstructured linker (residues 182–317) and a C-terminal domain (GephE, residues 318–736) that mediates interactions with the GlyR. The crystal structure of GephE in complex with a peptide derived from the large cytoplasmic loop between transmembrane helices 3 and 4 (TM3–4) of the GlyR β subunit (7) defined the interactions in atomic detail. GephE forms a dimer, and residues 398–410 of the GlyR β subunit engage in critical interactions at the dimer interface; however, they primarily interact with only one monomer. Specifically, the interaction of Phe-330 and Asp-327 in GephE with Phe-398, Ser-399, and Ile-400 of the GlyR β-subunit was found to be a major contributor to the overall binding strength. Concurrently the F398A mutant significantly weakened the gephyrin-GlyR β complex as verified by pulldown assays, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), and transient expression in HEK 293 cells (7).

Gephyrin was also shown to co-localize with γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors (GABAARs) harboring the α1–3, β2/3, or γ2 subunits (8, 9). Conflicting results have been published, however, on the role gephyrin plays in GABAAR clustering. Whereas gephyrin knock-out and antisense RNAi knockdowns in mice completely abolished all GlyR clusters, GABAAR clustering could still be observed, albeit depending on their subunit composition, at reduced levels. In particular GABAARs harboring the α2 or γ2 subunit showed a significantly reduced level of clustering (10–14). Conversely, gephyrin clustering itself was shown to depend on GABAARs containing either the α1, α3, or γ2 subunits (15–20), and a recent analysis of GABAAR α2 knock-out mice demonstrated a differential subcellular effect on gephyrin and GABAAR α1 clustering (21). Additionally, both GlyRs and GABAARs can co-exist within single postsynaptic densities. Mixed glycinergic/GABAergic inhibitory synapses have been functionally identified in motoneurons of the hypoglossal nucleus (22) and abducens nucleus (23), in interneurons of the spinal cord (24, 25), and the lateral superior olive (26). Which developmental role mixed inhibitory synapses play and how receptor co-clustering is mediated on the molecular level remains to be determined.

Recent studies demonstrated direct interactions of GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 subunits with gephyrin (27–29), possibly explaining the mutual dependence of GABAARs and gephyrin and GlyRs for postsynaptic accumulation. Interestingly, alanine-scanning mutagenesis identified residues 325–334 of GephE to be essential for GABAAR α3 (28) and residues 325–343 to be essential for GABAAR α2 (30) interaction and hence suggest overlapping binding sites for these GABAAR subtypes and the GlyR β-subunit. Here, we study in detail how the GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 subunits mediate the proposed gephyrin interactions at the molecular level and compare it to the gephyrin-GlyR β interaction.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Expression and Purification

Gephyrin variants were expressed and purified as described earlier (7). The large cytoplasmic loops between TM3–4 of the GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 subunits were PCR-amplified and inserted into the NcoI/NotI sites of the pETM-11 vector. Sequence numbers given in the text refer to the mature receptors without the signal sequence. Mutations were generated with the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 loop variants were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 cells (Stratagene, CA) as His6-tagged proteins. Cells were grown in LB medium at 30 °C, and protein expression was induced after the addition of 0.5 mm isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside for 18 h at 30 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (4000 × g), resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mm NaCl, 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol), and passed through a cell disruptor (Constant Systems), and cell debris was removed by centrifugation (70,000 × g). All proteins were initially purified using 5 ml of HisTrap FF crude columns according to the instructions of the manufacturer (GE Healthcare). Protein-containing fractions were collected, concentrated, and applied to a 26/60 Superdex 200 size exclusion column (Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated with buffer (10 mm Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 250 mm NaCl, 1 mm β-mercaptoethanol). Pure fractions were pooled, concentrated to 1–100 mg/ml, flash-frozen in 0.5 ml aliquots, and stored at −80 °C.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

Before all ITC experiments, protein samples were extensively dialyzed against 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 250 mm NaCl, 1 mm β-mercaptoethanol at 4 °C overnight followed by filtration and degassing. To analyze the gephyrin-receptor subtype interaction, 300 μl of a solution containing 180–1640 μm concentrations of the recombinant GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 subtype intracellular loops, the respective variants, or the synthesized GlyR β-subunit-derived peptide (DFSIVGSLPRDFEL, Genscript) were titrated as the ligand into the 1.5-ml sample cell containing 9–100 μm GephE, GephG with linker, or full-length gephyrin (P2 splice variant). In each experiment a volume of 10–15 μl of ligand was added at a time with a total number of 20–30 injections, resulting in a final molar ratio of ligand to protein of 4.5:1. All experiments were performed using a VP-ITC instrument (MicroCal, Northampton, MA) at 25 °C. Buffer-to-buffer titrations were carried out as described above, so that the heat produced by injection, mixing, and dilution could be subtracted before curve-fitting. The binding enthalpy was directly measured, whereas the dissociation constant (KD) and stoichiometry (N) were obtained by data analysis using the ORIGIN software, assuming a single site binding model. Binding parameters from singly performed measurements are given with standard derivations resulting from curve-fitting in ORIGIN. Measurements conducted several times are given as mean values and the resulting standard deviation (supplemental Table S2).

Native Gel Electrophoresis

Protein samples were mixed with OrangeG dye (Carl Roth) and 10% glycerol. 5-μl samples containing 5–100 μm concentrations of the respective protein were applied to 0.8% NEE0 ultra quality agarose (Carl Roth) gels containing 50 mm Tris/glycine, pH 8.4, buffer. Electrophoresis was conducted at 4 °C and terminated when the dye front was leaving the gel. Gels were stained for 10 min in 5% CH3COOH, 10% C2H5OH, and 0.005% Coomassie Brilliant Blue R250 (Carl Roth) and destained at least 1 day in 5% CH3COOH and 10% C2H5OH.

Pulldown Assays

N-terminally biotinylated GABAAR α1 (KNNTYAPTATSYTPN)-, α3 (KNTTFNIVGTTYPIN)-, and GlyR β (FSIVGSLPRDFEL)-derived peptides were synthesized by PANATecs. Because of excessive hydrophobicity, the corresponding GABAAR α2-derived peptide (QNNAYAVAVANYAPN) could not be synthesized. The biotinylated peptides were coupled to streptavidin beads and incubated with GephE (50 μm) in 10 mm Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 250 mm NaCl, and 1 mm β-mercaptoethanol for 1 h. After three washing steps with the same buffer, the beads were boiled with Laemmli buffer containing 10% SDS, and the supernatant was applied to an SDS-PAGE.

cDNA Constructs and Cell Culture

The full-length GABAAR α2 subunit (rat) used for the live imaging was modified with an N-terminal pHluorin as described previously (27). Double mutations were introduced using sequential PCR with appropriate sets of primers. Hippocampal neurons were prepared and nucleofected as described previously from E18 rat embryos of either sex (31, 32). All imaging experiments were performed using 18–21 days in vitro hippocampal cultures.

Antibodies, Immunocytochemistry, and Image Analysis

The GFP antibody (mouse monoclonal) was purchased from Roche Diagnostics, and the VIAAT (rabbit polyclonal) antibody was a generous gift from Dr. Bruno Gasnier (CNRS).

For immunostaining, cultures were lightly fixed, incubated with anti-GFP antibody followed by permeabilization with 0.4% Triton X-100, and incubated with the VIAAT antibody and subsequently with fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA).

Images were acquired using a Nikon Eclipse Ti series confocal microscope with a 60× objective (NA = 1.4) and analyzed using the MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Downington, PA) as described earlier (29, 32). A receptor cluster was defined as being ∼0.5 μm2 in size and ∼2–3-fold more intense than background diffuse fluorescence. Synaptic clusters were co-localized with or directly opposed to VIAAT staining. Analyses are based upon the number of cells (n) as indicated in the text from at least three independent cultures. Statistical analysis (unpaired t test) was performed using Kaleidagraph (Synergy Software, Reading, PA) software.

RESULTS

Comparative Binding Studies on the GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 Gephyrin Interactions

After the initial observation that gephyrin directly interacts with α2 subunit-containing GABAARs (27), an interaction of gephyrin with the α1 (29) and α3 subunits (28) has been described involving the large cytoplasmic TM3–4 loop.

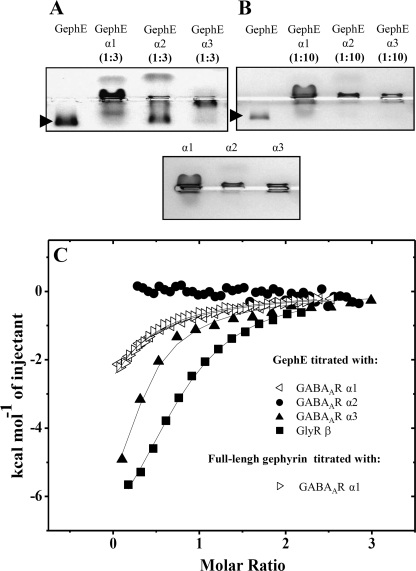

We cloned, expressed, and purified the corresponding loops of the GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 subunits and investigated their complex formation with GephE on native gels. Unlike GABAAR α1 and α3, which fully shifted GephE already at a molar ratio of 3 to 1 (Fig. 1A), only a 10-fold stoichiometric excess of GABAAR α2 was sufficient to complex all GephE under the experimental conditions (Fig. 1B), suggesting a significantly lower affinity of α2 for gephyrin compared with α1 and α3. To analyze gephyrin interactions with GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 in more detail, we determined their binding parameters under similar experimental conditions by ITC (Fig. 1C). The GABAAR α3 subunit intracellular loop displayed the strongest interaction with GephE (KD = 5.3 ± 1.5 μm) followed by the GABAAR α1 subunit intracellular loop (KD = 17 ± 11 μm). Under the same experimental conditions, an interaction between the α2 subunit of GABAAR and gephyrin could not be detected by ITC. This finding is in line with our native gel experiments, which together suggest that GABAAR α2 and gephyrin form a rather loose complex.

FIGURE 1.

Complex formation between GephE and the GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 subunits. A, native gel electrophoresis of GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 subunits applied in a 3-fold stoichiometric excess over GephE. Whereas GABAAR α1 and GABAAR α3 retain GephE in the gel pocket, incomplete GephE GABAAR α2 complex formation allows GephE (arrowhead) to enter the gel. B, native gel electrophoresis of GABAAR α1–3 at a 10-fold stoichiometric excess over GephE. This molar ratio does not allow any GephE (arrowhead) to enter the gel and migrate toward the anode. The migration of the receptor subunits in the absence of GephE (control) is shown below. C, ITC derived binding isotherms of GephE titrated with GABAAR α1 307–393 (TM3-TM4), GABAAR α2 307–391 (TM3-TM4), GABAAR α3 360–457 (TM3-TM4), GlyR β 398–411, and full-length gephyrin titrated with GABAAR α1 307–393 (TM3-TM4) are shown. Measured binding enthalpies are plotted as a function of the molar ratio of the respective receptor loop to gephyrin. Data of the titration of GABAAR α2 to GephE could not be analyzed due to very weak binding. Titration of GephE and full-length gephyrin with GABAAR α1 yields very similar binding isotherms.

Binding Site Mapping of the GABAAR α1 and α3 and GlyR β Gephyrin Interaction

The binding affinities between full-length gephyrin, different gephyrin domains, and selected GABAAR α1 and α3 variants were further investigated via ITC (Fig. 1) and pulldown assays (supplemental Fig. S1) as summarized in Table 1. Similar to what we observed earlier for the interaction between the GlyR β subunit and gephyrin, titration of full-length gephyrin with GABAAR α1 yielded similar binding parameters as the titration of GephE alone (Fig. 1C). Conversely, titration with GephG and the largest part of the linker region showed no detectable interaction (data not shown), thus confirming that the binding site resides in the E domain (Table 1A).

TABLE 1.

GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 and GlyR β loop gephyrin binding site mapping

Summary of the ITC data presented here (Fig. 1C) and earlier (28, 29) together with native gel (Fig. 1, A and B) and pulldown assays (supplemental Fig. S1) data. +++, KD = 0.1–1 μm; ++, KD = 1–20 μm; +, no interaction detectable in ITC but verified via native PAGE or pulldown assays; −, no interaction detectable via ITC, native PAGE, or pulldown assays.

| No. | Gephyrin | Receptor | Affinity |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1–734 (full-length) | GABAAR α1 307–393 (TM3-TM4) | ++ |

| 1–303 (G domain + Linker) | GABAAR α1 307–393 (TM3-TM4) | − | |

| 318–734 (E domain) | GABAAR α1 307–393 (TM3-TM4) | ++ | |

| B | E domain | GABAAR α1 307–393 (TM3-TM4) | ++ |

| E domain | GABAAR α1 Δ333–348 | − | |

| E domain | GABAAR α1 334–348 | + | |

| C | E domain | GABAAR α2 307–391 (TM3-TM4) | + |

| D | E domain | GABAAR α3 332–429 (TM3-TM4) | ++ |

| E domain | GABAAR α3 Δ369–378 | − | |

| E domain | GABAAR α3 364–378 | + | |

| E | E domain | GlyR β 398–411 | ++ |

| E domain | GlyR β 387–426 (TM3-TM4) | +++/++ |

After our deletion variant mapping we studied binding of the identified minimum peptides of α1 (residues 334–348, Table 1B), and α3 (residues 364–378, Table 1D), which were determined to be crucial for binding and exhibit only limited homology. ITC analysis of the GlyR β-derived peptide containing just the critical 14 amino acids visible in the crystal structure (referred to as GlyR short) displayed a significantly lower binding affinity (KD = 4.9 ± 0.4 μm) (Fig. 1C and Table 2) compared with the 49-residue construct (referred to as GlyR long) used for the structural studies (7). GlyR long, in addition to binding more tightly, also necessitated the use of a two-site binding model for data analysis resulting in dissociation constants of 0.14 ± 0.1 and 7.7 ± 0.1 μm for the high and low affinity binding sites, respectively (Table 2). Similar to the GlyR β loop, shortening of the GABAAR α1 and α3 loops lowered their affinity significantly; hence, the α1- and α3-derived minimum peptides could not be studied by ITC (data not shown). Instead we performed streptavidin pulldown experiments with the corresponding peptides covalently linked to biotin (supplemental Fig. S1). The pulldown data demonstrated that the residues contained within these peptides are sufficient to mediate a specific interaction with GephE with their relative binding strengths mirroring the full-length loops (supplemental Fig. S1 and Table 1, B and D).

TABLE 2.

Similar receptor residues show a correlated contribution to the overall GephE binding strength

Summary of the GABAAR α1 and α3 affinities for GephE determined by ITC here (Fig. 4, C and D) and the GlyR β loop affinities determined earlier (7). Underlined residues were mutated.

| Receptor | Binding motif | KD | Receptor | Binding motif | KD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm | μm | ||||

| GlyR β (long) | 398FAIVGSLP405 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | GABAAR α1 | 340AAPTATSY347 | ND |

| GABAAR α1 | 340YAPTATSY347 | 17 ± 11 | GABAAR α3 | 368ANIVGTTY375 | ND |

| GABAAR α2 | 339YAVAVANY346 | ND | GlyR β (long) | 398ASIVGSLP405 | 13 ± 0.1 |

| GABAAR α3 | 368FNIVVTTY375 | ND | GABAAR α3 | 368FNAVGTTY375 | ND |

| GABAAR α3 | 368FNIVGTTY375 | 5.3 ± 1.5 | GlyR β (long) | 398FSAVGSLP405 | 2.7 ± 0.7 |

| GlyR β (short)a | 398FSIVGSLP405 | 4.9 ± 0.4 | GABAAR α1 | 340YAPTATSA347 | ND |

| GlyR β (long)b2 | 398FSIVGSLP405 | 0.14 ± 0.1/7.7 ± 0.1 | GABAAR α3 | 368FNIVGTTA375 | ND |

a Residues 398–411 (FSIVGSLPRDFELS).

b Residues 378–426 (VGETRCKKVCTSKSDLRSNDFSIVGSLPRDFELSNYDCYGKPIEVNNGL).

Binding of Gephyrin to GABAAR α1 and α3, and GlyR β Is Mutually Exclusive

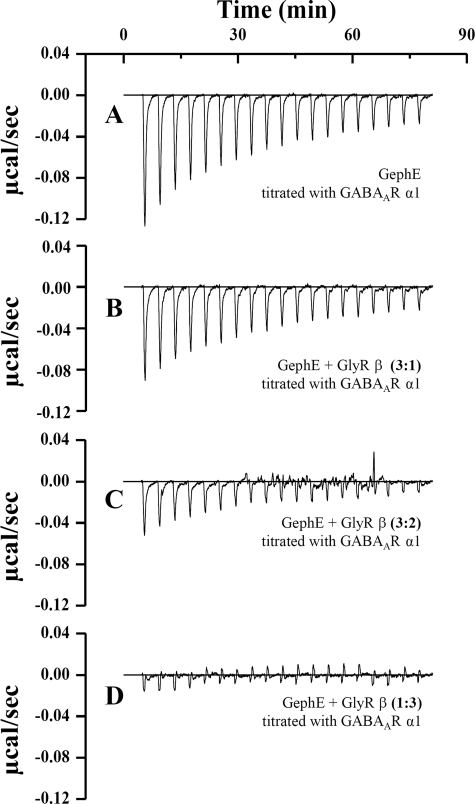

On the basis of the mapping experiments described here and published recently (28, 29), our binding studies identified the core motifs in the GABAAR α1 and α3 and GlyR β subunits, which directly interact with GephE. The wide range of affinities and the moderate overall homology observed here suggested different binding mechanisms for the respective receptor subunits. Concurrently recent studies (28, 30) did not identify individual residues within the core motifs that play a key role in binding to gephyrin. To address this issue, we conducted ITC competition experiments between GABAAR α1 and GlyR β (Fig. 2), which exhibit the lowest overall identity in their gephyrin-interacting region. Should GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 and GlyR β share a single binding site on gephyrin, we expected receptor binding by gephyrin to occur in a mutually exclusive fashion. Strikingly, our experiments revealed that pre-equilibration of gephyrin with a GlyR β-derived peptide containing only the 14-residue core motif was sufficient to significantly weaken and ultimately abolish the GABAAR α1 gephyrin interaction depending on the molar ratio of both loops (Fig. 2). This experiment can be rationalized as follows; upon pre-equilibration of GephE with GlyR β (Fig. 2, B–D) fewer unoccupied GABAAR α1 binding sites are available. Although the GABA AR α1 loop at high concentrations will eventually replace the GlyR β peptide, this will not be accompanied by a significant heat release because both binding events are exothermic reactions (Fig. 1C) and, hence, cancel each other out. Accordingly, the characteristic heat signature of the GABAAR α1 GephE titration (Fig. 2A) is significantly weakened upon applying a 3-fold molar excess of GlyR β peptide (Fig. 2D). Vice versa GABAAR α1 also interferes with GlyR β binding to GephE (supplemental Fig. S2), and taken together this indicates that GABAAR α1 and GlyR β compete for a single binding site located in the gephyrin E domain.

FIGURE 2.

ITC competition assay. Shown is the heat signature of 10 μm GephE titrated with 200 μm GABAAR α1 loop A in the absence and in the presence of 3 μm GlyR β (B), 6 μm GlyR β (C), and 30 μm GlyR β (D) peptide. Increasing amounts of GlyR β significantly reduce the heat released resulting from GephE-GABAAR α1 binding.

Comparison of the Identified GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 and GlyR β Motifs Reveals Common Elements

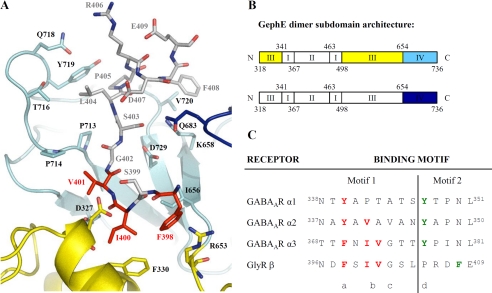

On the basis of the finding of exclusive binding of the receptors to gephyrin, we investigated the GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 binding motifs and also the gephyrin-interacting region of the GlyR β subunit for common sequence features. Each gephyrin subunit is composed of four subdomains (I-IV) of which subdomains III and IV are important for the interaction with the GlyR (Fig. 3, A and B). Several elements, summarized in Fig. 3C, appear noteworthy; our earlier structural analysis defined that Phe-398 of the GlyR β subunit is of major importance for the interaction with gephyrin by forming hydrophobic interactions involving Phe-330 in subdomain III of GephE (Fig. 3A). Strikingly, the corresponding residues Phe-397 in GABAAR α3 and Tyr-339 in GABAAR α1 and α2 appear to be strongly conserved aromatic residues (a in Fig. 3C), thus suggesting a similar role for the respective residues. Adjacent to this type-conserved aromatic residue, the GephE-GlyR β co-crystal structure displays a hydrogen bond-donating residue, Ser-399, in GlyR β that interacts with the gephyrin Asp-327 followed by two hydrophobic residues, Ile-400 and Val-401, in GlyR β that tightly fit into the hydrophobic pocket formed by subdomains III and IV of GephE (Fig. 3A). Noteworthy, the corresponding residues are strongly conserved in GABAAR α3 (Asn-370, Ile-371, and Val-372) and moderately in GABAAR α1 and α2 (Fig. 3C, b). Gly-402 in the GlyR β loop points toward subdomain IV of the gephyrin E domain, and interestingly the corresponding residues in GABAAR α3 and α1 are also very small (Gly-373 and Ala-344) (Fig. 3C, c), whereas GABAAR α2 has a significantly bulkier residue at this position (Val-343). GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 subtypes share a conserved tyrosine positioned eight residues C-terminal of the first conserved aromatic residue (Fig. 3C, d), yet the corresponding residue in GlyR β is a proline, thus suggesting that at least the C-terminal half of the GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 binding site relies on a different binding mechanism as compared with GlyR β.

FIGURE 3.

Sequence and structural determinants of gephyrin-receptor interactions. A, summary of binding interactions in the GephE-GlyR β loop complex crystal structure. GephE is colored according to its subdomain architecture and is represented as a ribbon diagram with residues central for the GlyR β loop binding shown as stick model (7). Residues of the GlyR β loop are also displayed in stick representation with C-atoms in gray and residues critical for GephE interaction marked in red. B, subdomain architecture of the GephE dimer. Subdomains I and II of the first monomer (top) and subdomains I, II, and III of the second monomer (bottom) are not visible in this view and hence have not been assigned a color. C, sequence alignment of the different motifs recognized by gephyrin. Residues critical for the GephE-GlyR β loop complex, which are strongly conserved in the GABAAR α3 subtype and moderately in α1 and α2, form a hydrophobic core motif marked in red. The tyrosine residue positioned in the C-terminal half of the motif (green) is conserved among the GABAAR subtypes but not in GlyR β. The binding sites are divided into an N-terminal region (motif 1) and a C-terminal part (motif 2). Elements a, b, and c are conserved among all receptor subtypes and together form motif 1. Motif 2 relies on a conserved tyrosine residue (element d), which is conserved among GABAAR subtypes but not in the GlyR β subunit.

Similar Interactions Are Central to Complex Formation between GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 and GlyR β with Gephyrin

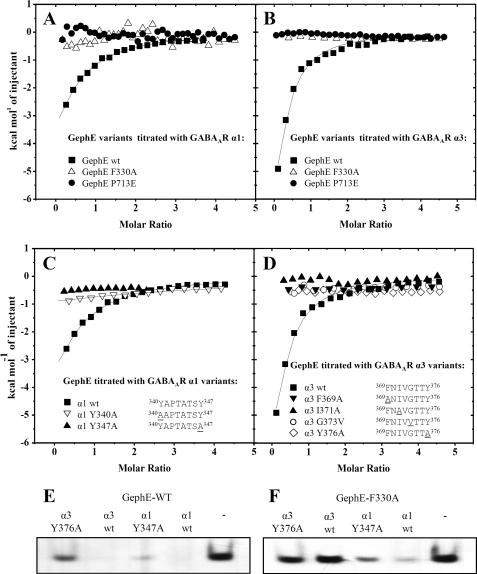

Based on the mutually exclusive binding and the identified features shared among the receptor motifs, we assumed that GephE binding to the N-terminal motif of the GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 binding site is mechanistically very similar to the interaction of the homologous residues in the GlyR β subunit. To test this and to explore the molecular basis of this phenomenon, we analyzed the effect on GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 binding of two critical gephyrin point mutants identified earlier. The mutation P713E in gephyrin was shown to completely abolish the tight GlyR β binding (7), possibly by introducing its bulky and negatively charged side chain into the receptor binding pocket formed by subdomains III, IV, and IV (Fig. 3A). A less severe change is represented by the gephyrin mutant F330A, which nevertheless significantly weakens GlyR β binding, most likely by diminishing the contribution of the hydrophobic interactions mediated by the hydrophobic core of the GlyR β loop and subdomain III of GephE. The binding of both mutants was analyzed by ITC for the GABAAR α1 and α3 subunits, and interestingly, both impaired binding so strongly that it could no longer be assessed by ITC (Fig. 4, A and B). The effect of the P713E variant supports the hypothesis that the binding site for the GlyR β subunit overlaps with that of the GABAAR α1 and α3 subunits in the vicinity of Pro-713. The impaired binding of the F330A variant likewise demonstrates overlap of the different binding sites in the vicinity of this residue but also argues that interactions with the GABAAR α1 and α3 subunits are driven by a similar contribution of the hydrophobic core region (Fig. 3C, a and b). The corresponding residues interacting with Phe-330 are strongly conserved among the GABAAR α3 and GlyR β subunits and to some extent also in GABAAR α1 and α2.

FIGURE 4.

Identification of residues crucial for the gephyrin-GABAAR α1 and α3 complex formation. Gephyrin point mutations critically reduce GABAAR α1 and α3 affinity in a comparable manner. Overlaid binding isotherms of different GephE variants titrated with the GABAAR α1 loop (A) and the GABAAR α3 loop (B) are plotted as a function of the molar ratio of receptor loop to GephE. Residues that are conserved among GlyR β and GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 appear to be critical for GephE complex formation. Overlaid binding isotherms of GephE-titrated with different GABAAR α1 loop (C) and GABAAR α3 loop (D) variants (mutated residues are underlined) are plotted as a function of the molar ratio of receptor loop to GephE. E and F, GephE variants alone and in the presence of the intracellular loop of GABAAR α1 WT, α3 WT, α1 Y347A, and α3 Y376A applied to native gel electrophoresis. Whereas GephE variants alone migrate toward the anode, GephE variants bound to the basic intracellular loops hardly enter the gel. E, native PAGE of GephE WT, which when complexed with WT receptor loops, does not enter the gel. Under the same experimental conditions GephE interacting with the altered subtypes partially enters the gel indicating a weakening of the complex formation. F, an analogous experiment with the F330A variant of GephE. The presence of the GABAAR intracellular loops of the α3 subunit (wild type and Y376A variant) does not alter GephE F330A migration toward the anode, indicating a completely abolished complex formation. In contrast, the α1 and α1 Y347A subunit show residual binding to GephE F330A, partially retaining it in the gel pocket.

Following the idea of a similar binding mechanism, we identified several residues corresponding to GlyR β residues that were identified earlier to be key contributors to the complex formation with GephE. Based on an alignment of the identified motifs, we predicted that Phe-369 of GABAAR α3 and Tyr-340 of GABAAR α1 are positioned in an analogous fashion as Phe-398 of GlyR β. In line with the >100-fold reduction in binding strength for GlyR β F398A, binding was no longer detectable by ITC (Fig. 4, C and D) and native gel electrophoresis (Fig. 4, E and F) for the GABAAR α3 F369A and GABAAR α1 Y340A variants. In an analogous fashion we proposed a similar role for GABAAR α3 Ile-371 as compared with GlyR β Ile-400, which critically weakened the gephyrin interaction upon alanine mutation. Not surprisingly, the GABAAR α3 I371A mutant was also significantly impaired in interacting with GephE (Fig. 4D).

Puzzled by our finding of a very weak GABAAR α2 affinity for GephE despite the high homology to the GABAAR α1 and α3 subunits, we carefully compared the identified binding regions, also in light of the GephE-GlyR β complex. This analysis focused our attention on Gly-374, which points toward subdomain IV of GephE in the GlyR β-GephE complex structure and is strictly conserved in GABAAR α3 (Gly-373) and type-conserved in GABAAR α1 (Ala-344) but not conserved in GABAAR α2, where it is replaced by a bulkier residue (Val-343) (Fig. 3C, c). In line with our suggestion of similar binding modes, we proposed this residue to repel the receptor loop by sterically clashing with subdomain IV of GephE (Fig. 3A), thus possibly explaining our observation of a rather weak GephE affinity as compared with GABAAR α1 and α3. We replaced the corresponding residue in GABAAR α3 with valine (G373V), and subsequent ITC analysis (Fig. 4D) revealed a significantly reduced affinity. Although we could not reconstitute binding to the level of the GABAAR α1 or α3 subtype, native gel electrophoresis of the corresponding GABAAR α2 mutant (V343G) visualizes an increased gephyrin affinity (supplemental Fig. S3). Taken together this indicates that this residue could at least be partially responsible for the observed weak GephE GABAAR α2 affinity.

Hydrophobic Interactions Mediated by Aromatic Residues Are Critical for GABAAR α1 and α3 GephE Complex Formation

After our mutational analysis we wanted to dissect the relative contributions to the overall binding strength of the conserved N-terminal hydrophobic motif (Fig. 3C, a and b) and the C-terminal parts (Fig. 3C, d) of the respective GABAAR α1 and α3 motifs. Given that ITC is not sensitive enough to display any residual binding for the respective mutants, we instead used native gel electrophoresis. As expected, the gel electrophoresis experiments verified a major impact on binding strength for all of the analyzed mutants (Fig. 4, E and F). In line with our ITC experiments, no residual binding could be detected for GephE F330A incubated with GABAAR α3. The Y376A variant of the GABAAR α3 subunit was also significantly impaired; however, it allowed for some residual binding to GephE. In the case of the GABAAR α1 subunit, the corresponding substitutions displayed a similarly weakened receptor binding. The simultaneous alanine substitutions of GephE Phe-330 and GABAAR α1 Tyr-347 synergistically weakened the interaction, yet some residual binding could still be detected. Taken together these results document major contributions of the hydrophobic motif at the N terminus (Fig. 3C, a and b) and the conserved aromatic residues for GABAAR α1 and α3 (Fig. 3C, d) but also suggest additional distinct contributions to the binding strength unique to the GABAAR α1 subunit.

Clustering of α2-containing GABAARs in Hippocampal Neurons Critically Depends on Two Conserved Aromatic Residues

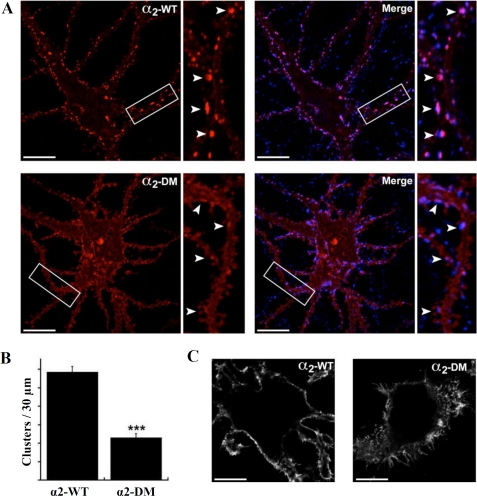

Our in vitro data obtained from the native gel electrophoresis and ITC experiments identified two conserved aromatic residues in the α1 and α3 subunits of GABAARs and GlyR β subunit (a and d in Fig. 3C) to be critical for direct and exclusive binding to gephyrin. Earlier studies demonstrated that the region containing these two aromatic residues is crucial in vivo for gephyrin-mediated clustering of GABAAR subtypes α1 (29) α2 (27), α3 (28), and GlyR β (4), and our earlier studies demonstrated that two aromatic residues (Phe-398 and Phe408 together with Ile-400) are critical for GlyR β clustering by gephyrin in HEK 293 cells (7). Therefore, we tested whether the aromatic residues, Tyr-339 and Tyr-346, are also crucial for clustering of α2 containing GABAARs. We mutated both residues to alanine and compared (Fig. 5A) the synaptic accumulation of GABAARs between wild-type and the α2 subunit double mutant (DM), both modified with N-terminal pHluorin reporters (pHα2 WT and pHα2 DM (Y339A/Y346A), respectively). Confocal imaging was performed on hippocampal neurons at ∼21 days in vitro expressing pHα2 WT and pHα2 DM after cells were lightly fixed and stained with the respective antibodies. Surface staining with a GFP antibody revealed a significant loss of GABAARs clusters per 30 μm (11.7 ± 0.6 versus 4.6 ± 0.4, n = 30 neurons, pHα2 WT and pHα2 DM, respectively, unpaired t test; p ≤ 0.001) (Fig. 5B). These clusters are primarily synaptic as they are either co-localized or opposed to VIAAT-positive puncta. Moreover, cells expressing mutant pHα2 subunit are positive for VIAAT puncta, suggesting that they are innervated by inhibitory presynaptic terminals.

FIGURE 5.

Mutation of conserved tyrosine residues attenuates the clustering of α2-containing GABAARs at postsynaptic sites. Hippocampal neurons were nucleofected with pHα2-WT and pHα2-DM (Y339A/Y346A), lightly fixed (∼21 days in vitro), stained with GFP antibody against extracellular pHluorin tag (red), and subsequently stained with presynaptic marker VIAAT (blue) in the presence of 0.04%Triton. A, a single plane confocal image shows the clustering pattern of pHα2-WT (upper panel) and pHα2-DM (lower panel). Note that although pHα2-WT can form mostly synaptic clusters, as demonstrated by a predominant co-localization with VIAAT puncta (blue, merge), the ability to form clusters is greatly attenuated for pHα2-DM as cluster number and intensity are both strongly reduced. For each panel, a higher magnification image of the boxed area is shown on the right, with arrows pointing to clusters (scale bar = 15 μm). B, quantification of the average number of clusters formed by pHα2-WT and pHα2-DM. Clusters that are opposed to VIAAT-positive puncta were counted along dendrites per 30 μm (n = 30 cells each, unpaired t test, p < 0.001). C, to test whether attenuation of the clusters formed by pHα2-DM is not due to compromised assembly or surface trafficking, pHα2 and pHα2-DM were expressed along with the β3 subunit in HEK 293 cells. Cells were lightly fixed and surface-labeled with GFP antibody against extracellular pHluorin tag (red). Confocal images show that both pHα2-WT (left panel) and pHα2-DM (right panel) can access the surface membrane to a similar extent (scale bar = 15 μm).

To control for possible negative effects of mutations on receptor assembly or surface trafficking, we examined the ability of the pHα2 WT and pHα2 DM subunit to gain access to the plasma membrane on co-expression with the β3 subunit in HEK 293 cells. Transfected cells were surface-labeled (without permeabilization) with GFP antibodies. Fig. 5C shows that in the presence of the β3 subunit, both pHα2 WT and pHα2 DM subunits gain access to the surface membrane to a similar extent. This process seems specific as we observed minimal surface trafficking when expressing pHα2 subunit alone (data not shown). Collectively these experiments suggest that both tyrosine residues are critical for regulating the accumulation of GABAARs α2 and α1 subunits at inhibitory postsynaptic sites via a direct interaction with gephyrin.

DISCUSSION

Gephyrin has been implicated for quite some time in the anchoring of GABAARs; however, a direct interaction between this protein and specific receptor subunits has only been demonstrated recently for the α1, α2, and α3 subunits (27–29). Following up on these studies we investigated the interaction between the full-length intracellular TM 3–4 loops of the GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 subunits and the gephyrin E domain and observed that the affinities varied considerably. Moderately tight interactions that could be described by a one-site binding model were observed for the GABAAR α1 (KD = 17 ± 11 μm) and α3 (KD = 5.3 ± 1.5 μm) subunits, whereas the GephE interaction with GABAAR α2 was too weak to be analyzed by ITC. Concurrently, the analysis via native PAGEs revealed the same order of relative binding strengths for the receptor loops, and this ranking is maintained at different pH values (pH 7–9) and salt concentrations ranging from 50 to 250 mm (data not shown). The measured moderate GABAAR α1 and α3 affinities match the binding constants determined for the interactions between the C-terminal tails of excitatory NMDA and AMPA receptors and PDZ (post synaptic density protein (PSD95)) domain-containing scaffolding proteins that play a critical role in the formation of the postsynaptic density at excitatory synapses and are characterized by KD values varying between 1 and 50 μm (33).

In contrast, the much weaker gephyrin-GABAAR α2 affinity seems not sufficient for receptor anchoring and instead suggests that additional binding partners are involved, or that affinity is enhanced by posttranslational modifications. Interestingly, it was recently shown that GABAAR α2 but not α3 forms a tripartite complex with collybistin (30), a brain-specific Cdc42-activating GDP-GTP exchange factor that promotes submembrane clustering of gephyrin and is essential for the postsynaptic localization of gephyrin and GABAARs.

In contrast to the moderately tight single site interaction between GABAAR α1 and α3 subunits and gephyrin, earlier biochemical and biophysical analyses of GlyR β residues 387–426, which cover the central part of the TM 3–4 loop, suggested two binding sites with KD values of 0.14 ± 0.1 and 7.7 ± 0.1 μm, respectively (3). A subsequent co-crystal structure (7) revealed that residues 398–411 of the GlyR β subunit engage in close contacts with a binding site near the GephE dimer interface. In this study we also investigated the interaction between the core region (residues 398–411) of the GlyR β subunit and GephE by ITC and observed, in contrast to the 49 residue GlyR β fragment, only a single binding site that displayed an affinity of 4.9 ± 0.4 μm. Because the triple alanine GlyR β mutation F398A/I400A/F408A is sufficient to completely abrogate complex formation in vitro and in vivo (7), we conclude that GlyR β residues 398–411 represent the core binding site, whereas residues 387–397 and 412–426 contain elements that enhance the affinity of this core motif. In a comparable manner, applying only the homologous core motifs of either the GABAAR α1 or α3 subunits resulted in a decreased affinity as compared with the respective full-length loops. Our native gel assays, ITC, and cell culture experiments, however, provide evidence that mutation of the conserved aromatic residues (Fig. 3C, a and d) is sufficient to completely abrogate GephE binding and, hence, strongly argue against the existence of other major gephyrin binding determinants in the remaining parts of the receptor loop. How this increase in affinity for the full-length loops can be explained on the molecular level, and how it is connected to the observed second binding site in the case of the GlyR remain open questions. Possibly there are structural rearrangements in either GephE or the intracellular loops.

Our binding studies with deletion variants described here and published earlier (28, 29) identified a moderately conserved core motif in GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 and GlyR β that is essential for gephyrin binding. Recent yeast two-hybrid studies (28, 30) suggested that both receptors bind to distinct, albeit partially overlapping binding sites; however, neither the role of individual residues in gephyrin-mediated receptor binding nor the question as to whether gephyrin can simultaneously bind to GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 and GlyR β subunits has been addressed. Regarding the last issue, ITC experiments revealed competitive binding between GABAAR α1 and GlyR β. Taking into account that the GABAAR α1 and GlyR β sequences display the lowest degree of homology among all analyzed subunits, this finding strongly suggest that, in addition to GABAAR α1 and GlyR β, GABAAR α2 and α3 also compete for the same binding site.

The mutually exclusive binding was confirmed by two GephE mutants (P713E and F330A) that abolished or weakened binding to the GABAAR α1 and α3 as well as GlyR β subunits. Within the common binding pocket, GephE Phe-330 mediates conserved hydrophobic interactions with a conserved aromatic residue (Fig. 3C, a) This finding may present a molecular explanation for earlier studies that proposed GephE residues 325–334 to be essential for GABAAR α3 (28) and residues 325–343 to be essential for GABAAR α2 (30) binding. Disruption of the N-terminal helix of GephE (residues 326–336) by introduction of poly-alanine blocks may have affected Phe-330 of GephE, which we have identified here to be a major determinant of GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 binding.

To verify whether a similar mechanism is also crucial for GABAAR α2 and gephyrin complex formation and, hence, its synaptic accumulation, we studied the respective alanine mutations in GABAAR α2 receptors by in vivo co-localization of the receptor and gephyrin in cultured hippocampal neurons. Significantly, compared with wild type, the clustering of the GABAAR α2 Y339A/Y346A double mutant revealed a significant loss of clustering in cultured hippocampal neuron. These findings support the relevance of our in vitro results for in vivo receptor clustering and demonstrate that our mutational studies can be extended to the GABAAR α2 subunit, which due to its weak binding to gephyrin, could not be analyzed in great detail in vitro. Additionally the major importance of the conserved aromatic residues presents a possible molecular explanation for earlier findings (29), which proposed a negative regulation of clustering upon GABAAR α1 Thr-348 phosphorylation. In vitro and in vivo studies verified a significantly weakened interaction for the phosphomimetic T348E mutation as compared with the wild type or the respective alanine mutant. Introduction of a negative charge at the adjacent residue apparently interfered with the critical hydrophobic interactions mediated by the conserved tyrosine (Tyr-347). Interestingly, earlier studies identified both GABAAR α1 tyrosines determined here as critical mediators of GephE binding to be phosphorylated in vivo and hence represent possible regulatory mechanism for the gephyrin GABAAR α1 interaction (34, 35).

Collectively our in vitro and in vivo studies on the pleiotropic effects of the mutants define two different hotspots of GABAAR recognition by gephyrin. The first is the N-terminal half of the ∼15-residue core binding site. This region relies on interactions that are highly similar to the GlyR β subunit and involves hydrophobic contacts between the gephyrin Phe-330 and the respective aromatic residues in GABAAR α1, α2, and α3. This conserved interaction is also at least in part responsible for a mutually exclusive binding between the different GABAAR subtypes and the GlyR β subunit. The second is the C-terminal half of the core region. This region displays a conserved tyrosine residue in the GABAAR α1, α2, and α3 subunits; however, it is distinct from the important second aromatic residue of the GlyR β subunit. Further details of the gephyrin-GABAAR interaction, however, will have to await the structural characterization of a complex involving the E domain of gephyrin and a peptide derived from the α1, α2, or α3 subunits.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Bodo Sander for contributions to the project.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (RVZ FZ 82, Schi 425/2-1, and SFB487 C7; to H. S.) and the European Community (EC-FP7 integrated project “Neurocypres”; HEALTH-F4-2008-202088; to V. T.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1–S3.

- GlyR

- glycine receptor

- GABAAR

- GABA subtype A receptor

- GephE

- E domain of gephyrin

- TM

- transmembrane

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- VIAAT

- vesicular inhibitory amino acid transporter

- DM

- double mutant.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pfeiffer F., Graham D., Betz H. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 9389–9393 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meyer G., Kirsch J., Betz H., Langosch D. (1995) Neuron 15, 563–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schrader N., Kim E. Y., Winking J., Paulukat J., Schindelin H., Schwarz G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 18733–18741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kneussel M., Hermann A., Kirsch J., Betz H. (1999) J. Neurochem. 72, 1323–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Giesemann T., Schwarz G., Nawrotzki R., Berhörster K., Rothkegel M., Schlüter K., Schrader N., Schindelin H., Mendel R. R., Kirsch J., Jockusch B. M. (2003) J. Neurosci. 23, 8330–8339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kirsch J., Langosch D., Prior P., Littauer U. Z., Schmitt B., Betz H. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 22242–22245 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim E. Y., Schrader N., Smolinsky B., Bedet C., Vannier C., Schwarz G., Schindelin H. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 1385–1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sassoè-Pognetto M., Kirsch J., Grünert U., Greferath U., Fritschy J. M., Möhler H., Betz H., Wässle H. (1995) J. Comp. Neurol. 357, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sassoè-Pognetto M., Panzanelli P., Sieghart W., Fritschy J. M. (2000) J. Comp. Neurol. 420, 481–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kneussel M., Brandstätter J. H., Laube B., Stahl S., Müller U., Betz H. (1999) J. Neurosci. 19, 9289–9297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fischer F., Kneussel M., Tintrup H., Haverkamp S., Rauen T., Betz H., Wässle H. (2000) J. Comp. Neurol. 427, 634–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lévi S., Logan S. M., Tovar K. R., Craig A. M. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24, 207–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kneussel M., Brandstätter J. H., Gasnier B., Feng G., Sanes J. R., Betz H. (2001) Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 17, 973–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yu W., Jiang M., Miralles C. P., Li R. W., Chen G., de Blas A. L. (2007) Mol. Cell Neurosci. 36, 484–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schweizer C., Balsiger S., Bluethmann H., Mansuy I. M., Fritschy J. M., Mohler H., Lüscher B. (2003) Mol. Cell Neurosci. 24, 442–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alldred M. J., Mulder-Rosi J., Lingenfelter S. E., Chen G., Lüscher B. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25, 594–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li R. W., Yu W., Christie S., Miralles C. P., Bai J., Loturco J. J., De Blas A. L. (2005) J. Neurochem. 95, 756–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kralic J. E., Sidler C., Parpan F., Homanics G. E., Morrow A. L., Fritschy J. M. (2006) J. Comp. Neurol. 495, 408–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Winsky-Sommerer R., Knapman A., Fedele D. E., Schofield C. M., Vyazovskiy V. V., Rudolph U., Huguenard J. R., Fritschy J. M., Tobler I. (2008) Neuroscience 154, 595–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Studer R., von Boehmer L., Haenggi T., Schweizer C., Benke D., Rudolph U., Fritschy J. M. (2006) Eur. J. Neurosci. 24, 1307–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Panzanelli P., Gunn B. G., Schlatter M. C., Benke D., Tyagarajan S. K., Scheiffele P., Belelli D., Lambert J. J., Rudolph U., Fritschy J. M. (2011) J. Physiol. 589, 4959–4980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O'Brien J. A., Berger A. J. (1999) J. Neurophysiol. 82, 1638–1641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Russier M., Kopysova I. L., Ankri N., Ferrand N., Debanne D. (2002) J. Physiol. 541, 123–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Geiman E. J., Zheng W., Fritschy J. M., Alvarez F. J. (2002) J. Comp. Neurol. 444, 275–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Keller A. F., Coull J. A., Chery N., Poisbeau P., De Koninck Y. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 7871–7880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nabekura J., Katsurabayashi S., Kakazu Y., Shibata S., Matsubara A., Jinno S., Mizoguchi Y., Sasaki A., Ishibashi H. (2004) Nat. Neurosci. 7, 17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tretter V., Jacob T. C., Mukherjee J., Fritschy J. M., Pangalos M. N., Moss S. J. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 1356–1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tretter V., Kerschner B., Milenkovic I., Ramsden S. L., Ramerstorfer J., Saiepour L., Maric H. M., Moss S. J., Schindelin H., Harvey R. J., Sieghart W., Harvey K. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 37702–37711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mukherjee J., Kretschmannova K., Gouzer G., Maric H. M., Ramsden S., Tretter V., Harvey K., Davies P. A., Triller A., Schindelin H., Moss S. J. (2011) J. Neurosci. 31, 14677–14687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Saiepour L., Fuchs C., Patrizi A., Sassoè-Pognetto M., Harvey R. J., Harvey K. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 29623–29631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kittler J. T., Thomas P., Tretter V., Bogdanov Y. D., Haucke V., Smart T. G., Moss S. J. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12736–12741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jacob T. C., Bogdanov Y. D., Magnus C., Saliba R. S., Kittler J. T., Haydon P. G., Moss S. J. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25, 10469–10478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jemth P., Gianni S. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 8701–8708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Munton R. P., Tweedie-Cullen R., Livingstone-Zatchej M., Weinandy F., Waidelich M., Longo D., Gehrig P., Potthast F., Rutishauser D., Gerrits B., Panse C., Schlapbach R., Mansuy I. M. (2007) Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 283–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ballif B. A., Carey G. R., Sunyaev S. R., Gygi S. P. (2008) J. Proteome Res. 7, 311–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.