Abstract

The resolving power of differential ion mobility spectrometry (FAIMS) was dramatically increased recently by carrier gases comprising up to 75% He or various vapors, enabling many new applications. However, the need for resolution of complex mixtures is virtually open-ended and many topical analyses demand yet finer separations. Also, the resolving power gains are often at the expense of speed, in particular making high-resolution FAIMS incompatible with online liquid-phase separations. Here, we report FAIMS employing hydrogen, specifically in mixtures with N2 containing up to 90% H2. Such compositions raise the mobilities of all ions and thus the resolving power beyond that previously feasible, while avoiding the electrical breakdown inevitable in He-rich mixtures. The increases in resolving power and ensuing peak resolution are especially significant at H2 fractions above ~50%. Higher resolution can be exchanged for acceleration of the analyses by up to ~4 times, at least. For more mobile species such as multiply-charged peptides, this exchange is presently forced by the constraints of existing FAIMS devices, but future designs optimized for H2 should consistently improve resolution for all analytes.

Introduction

Ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) comprises1–3 methods for separating, characterizing, or identifying ions based on their transport through gases driven by an electric field of some intensity (E). The role of IMS coupled to mass spectrometry (MS) in analytical science had steadily risen over the last decade, as IMS/MS has grown from a niche technique for structural elucidation of exotic clusters to a broadly useful alternative or complement to condensed-phase approaches of liquid chromatography (LC) or electrophoresis for rapid bioanalytical separations.4 In parallel with the emergence of new applications, IMS capabilities have been expanded through introduction of novel methods and commercial instrumentation exploiting them. Of note is the development of differential or field asymmetric waveform IMS (FAIMS)3,5 based not on the absolute ion mobilities (K) employed by conventional IMS (whether drift tube1 or traveling wave6 IMS), but the difference of K between low and high E.

That difference is measured in FAIMS directly, by subjecting ions to a dynamic field in a gap between two electrodes, established using a periodic asymmetric waveform of some peak amplitude (termed “dispersion voltage”, DV). Ions injected into the gap oscillate and migrate to one of the electrodes because of different mobilities during opposite-polarity segments with unequal E. For a species with given difference between those K values, the net migration can be offset using a weak time-independent “compensation field” (EC) superposed on the separating field. Scanning EC reveals the spectrum of species present. Performance strongly depends on the gap shape. Broad metrics of FAIMS separation power are the resolving power (R) - the EC value for a peak divided by its full width at half maximum (w), and peak capacity (p) - the separation space for a given analyte set divided by w. The metric for specific analytes is resolution (r) - the EC difference between two peaks divided by w. An inhomogeneous field in curved (cylindrical or spherical) gaps permits equilibrating multiple species simultaneously, which broadens the peaks. Therefore, all three metrics are maximized with planar gaps, where the field is homogeneous and only one species can be in perfect equilibrium at any time.3,7 For example, planar units have provided R ~ 40 – 70 for multiply-charged peptide ions vs. ~6 – 12 in a commercial device with cylindrical gap of equal 2 mm width (using the same DV = 4 kV, 1:1 He/N2 gas mixture, and “standard” filtering time of t = 0.2 s).8

Another factor in IMS is the buffer (carrier) gas identity. The mobility at low E depends on the masses of the ion (m) and gas molecule (M), and the ion - molecule collision integral or cross section (Ω) by the Mason-Schamp equation:2

| (1) |

where k is the Boltzmann constant, ze is the ion charge, and T and N are the gas temperature and number density. Ions of interest are normally much larger and heavier than the common gas molecules (He, N2, or CO2), and Ω is primarily controlled by ion size and shape, whereas the reduced mass nearly equals M. Thus varying the gas composition generally scales the mobilities of all ions similarly and hence affects conventional IMS separations only marginally, if at all.9,10 The resolving power is independent of gas identity:1

| (2) |

The small variation of separation properties and no variation of R mean virtually no effect on the peak capacity; indeed, that for tryptic digests is essentially independent of the gas (He, CH4, N2, or Ar).9 The relative peak positions for smaller ions such as iodo-, bromo-, and chloro- anilines (128 – 220 Da), arginine and phenylalanine (166 and 175 Da), or lorazepam and diazepam (284 and 302 Da) may be shifted and even inverted11–13 by switching between gases with differing molecular polarizabilities (a): He (0.20 Å3), Ar (1.64 Å3), N2(1.74 Å3), and CO2 (2.91 Å3). This may be useful for targeted separations,11–13 but not global analyses as the peak capacity remains unchanged. Such shifts are not observed for medium-size ions (e.g., tetrapeptides)11 or larger species, for which Ω is primarily dictated by ion properties as stated above. Thus, conventional IMS has largely utilized convenient and inexpensive N2 (air) or He that permits simpler and more accurate a priori mobility calculations and thus is preferred for structural determination.14

In contrast, the K(E) derivative that underlies FAIMS is governed by the details of ion - gas molecule potential that are sensitive to the physical and chemical properties of the molecule.3,5,15 Hence modifying the gas composition may sharply affect separations; even the EC sign may be inverted15 by switching from CO2 or N2O to O2, N2, or SF6. Small amounts of moisture or organic (e.g., alcohol) vapors in the gas may not only change species peak order, but greatly increase EC values, expanding the separation space and peak capacity.16–19 For example, the maximum resolving power for phthalic acid isomers (o-, m-, and p-) can be raised fivefold19 (from 27 to 140) by adding 1.5% methanol vapor to N2. This is caused by reversible clustering, where vapor molecules adsorb on an ion during the weak-field segment of the waveform (when the ion temperature TI is low) and evaporate in the “warmer” strong-field segment (as field heating elevates TI). This process may drastically decrease K at low (but not high) E, creating much steeper K(E) curves and thus wider separation spaces than feasible in true gases.16–18 This approach has had success for smaller 1+ ions such as amino acids and dipeptides, but so far not for larger and particularly multiply-charged species such as proteolytic peptides (ordinarily with ~5 – 25 residues) and proteins generated by electrospray ionization (ESI) and relevant to proteomics. At least in part, that is due to facile charge reduction of multiply-charged ions by exothermic proton transfer to vapor molecules or clusters with higher proton affinities.

Alternatively, the separation power of FAIMS with any gap shape is generally improved when He is added to heavier gases, such as8,20–28 N2, CO2, or SF6. First, in planar devices at moderate E, the peak widths scale3,29 as K−1/2. This scaling is not exact, mostly because the anisotropy of ion diffusion at high E breaks the linear dependence of the diffusion coefficient (D) on mobility, but is a fair approximation for “full-size” (not miniaturized) analyzers.29,30 Hence making ions more mobile narrows the peaks and improves all separation power metrics that are proportional to 1/w. As noted above, the K values for reasonably large ions in the low-E limit scale as 1/(ΩM1/2). This approximately applies in FAIMS, as the mobilities of these ions at moderate E deviate from K(0) only marginally. Thus, the mobilities for larger ions with equal Ω in He (M = 4 Da) exceed those in N2 (M = 28 Da) by ~71/2 = 2.65 times. Ions also have lower cross sections with He atoms than the larger and more polarizable N2 molecules.11,13,31,32 This factor increases the ratio of mobilities in He and N2 by ~10 – 50% (more so for smaller ions where the collision partner identity is more important), and typical biomolecular ions are more mobile in He by ~3 – 4 times11,13,31,32 than in N2. By Blanc's law, the mobilities in He/N2 then exceed those in N2 by ~1.5 – 1.6 and ~2 – 2.3 times at 50% and 75% He, respectively. (Although the “law” is not accurate at higher fields,3,28 it suffices for such estimates.) The FAIMS peaks narrow accordingly, contributing about half to the resolution gains upon He addition.8,23,24 The other half comes from expanding separation space due to (1) stronger K(E) dependences in He compared to N2 and (2) non-Blanc phenomena that tend to magnify those dependences in mixtures of molecules that form dissimilar potentials with ions,28 such as He and N2.

However, He promotes electrical breakdown in gas, and its threshold drops with increasing He content.33 This drawback limits the He fraction in usable mixtures, for He/N2 to ~50 – 75% (depending on the peak E), although higher fractions tend to improve separations.23,24 Increasing the He content from zero to the maximum raises R of planar FAIMS devices for multiply-charged peptides by ~5 – 10 times (from ~10 – 40 to ~100 – 220 in t = 0.2 s),8,23–25 opening new applications such as routine separation of sequence and localization isomers.25,26 The gains for smaller ions are similar,20,22,27 in particular enabling resolution of isotopologues.27

Close to the threshold, breakdown across the gap may be triggered by minor variations of DV output, ambient gas pressure, temperature, or composition, and/or changes of nature or quantity of ions in the gap during EC scan or due to source intensity fluctuations. Such breakdown causes analysis failure, sample loss, downtime for system cleaning and recalibration, and can also damage equipment and impede automation by necessitating close operator oversight. Stable operation requires tight control of all relevant parameters and tolerance of the waveform generator to shorting across the load should breakdown occur. Many existing systems, including those with active feedback loops for DV control in some current products, do not withstand such shorting and must be operated well below the breakdown threshold despite the diminished performance.

Another factor is helium cost, projected to increase in the near future.34 The flow rate of carrier gas to typical FAIMS devices (Q) is ~2 – 4 L/min,23–26,35 and the cost of consumed He significantly impedes the acceptance of FAIMS, particularly outside of the US where He is more expensive and harder to procure.34 Unfortunately, use of just N2 has so far not produced the high resolution provided by He/N2 mixtures and needed for advanced separations.34

As usual for separations in media, FAIMS resolving power scales as t1/2. This is rigorous in the infinite t limit, where the time for onset of filtering (required for ions migrating toward electrodes to fill a finite gap) is negligible in comparison,29,36 and a good approximation with long filtering times needed for high resolution. Thus, even higher R (up to ~330 for multiply-charged peptides) were reached36 by extending t from 0.2 s to 0.5 – 0.8 s. However, the minimum time for an EC scan is ~2pt, accounting for downtime while ions exit the gap once EC is incremented. This situation renders even t = 0.2 s too long for many applications, crucially integration with LC/MS without slowing the LC gradient or sacrificing the peak capacity through selective stepping.37 For example, a scan with p ~ 130 for tryptic digests23 (provided by maximum R ~ 200) takes at least ~1 min, which substantially exceeds the eluting peak widths in modern HPLC. Raising the resolving power by extending t augments the problem as both p and t increase. For instance, a scan with p ~ 200 achievable36 in t = 0.5 s takes at least ~3 min or >10 times the peak widths in practical HPLC.

Desiring to improve the FAIMS resolution and throughput without compromising the other and to increase both from present levels, we explored a buffer using hydrogen, specifically in H2/N2 mixtures. This medium provides the resolving power and resolution matching or exceeding that achieved in He/N2, while substantially accelerating analyses.

Experimental Methods

We used a planar FAIMS unit coupled to a modified LTQ ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher).23–26 The H2/N2 gas with the H2 fraction (v/v) of 0 – 100% was formulated by flow meters (MKS Instruments, Andover, MA) and supplied at Q = 1.0 – 2.7 L/min. This value was limited by the highest H2 inflow permitted by present MS pumping capacity, below. Calculated ion residence time in the gap, which is proportional to 1/Q, was t = 0.40 – 0.15 s. As with He/N2 mixtures, the samples were infused at ~0.5 μL/min. Performance was evaluated using reserpine and selected peptides, dissolved to ~10 μM in our previously adopted ESI infusion solvent (50/49/1 water/methanol/acetic acid).

Flammability of H2 requires safety precautions, and the major concern is H2 expelled into the lab. While some carrier gas is evacuated through the MS system into the pumping exhaust, most enters the lab from the FAIMS inlet and the unsealed FAIMS/MS interface (especially at elevated Q values). In a small and/or poorly ventilated space, the H2 inflow can accumulate and cause fire or explosion, conceivably triggered by a spark in the unit. Hence the instrument was installed in a spacious, thoroughly ventilated laboratory where even continuous operation at maximum H2 flow could not build up dangerous H2 concentrations. The risk of leaks from the line taking H2 from its source to the unit was mitigated by placing the H2 cylinder in a ventilated cabinet and connecting it to the unit using steel (rather than common plastic) tubes with Swagelok fittings. The local H2 concentrations near the ESI/FAIMS and FAIMS/MS junctions can still be high, and a discharge between the ESI emitter and curtain plate (cp) of the FAIMS device can ignite the gas coming out of the cp orifice. Thus, at the higher H2 fractions, we have decreased the cp voltage from the usual 1 to ~0.7 kV, reduced the offset of ESI emitter over cp from ~2.4 to ~1.6 kV, and increased the distance from the emitter tip to cp.

The turbomolecular pumps of LTQ MS lose efficiency when evacuating23 He, and even more so for H2. With Q = 2 L/min, the pressures measured by the ion and convectron gauges increase from, respectively, 1 × 10−5 and 1.3 Torr in N2 to ~2.4 × 10−5 and ~9 Torr at >70% H2. While we operated in that regime for hours, it is far above the normal pressure range for this and other common commercial API/MS platforms that are not designed to aspirate H2-rich mixtures from the inlet. Elevated pressure in the MS manifold may affect the accuracy, resolution, and/or sensitivity of MS analyses and cause hardware failures. Present MS system shuts down when the convectron gauge measures >10 Torr, precluding Q above ~2.5 L/min for H2-rich mixtures

Fundamentals of Resolving Power for FAIMS Employing Hydrogen

Hydrogen improves FAIMS resolution for the same reasons as He. The key advantage of H2 are breakdown thresholds that greatly exceed those for He, e.g., ~4.5 kV vs. ~1 kV for a dc voltage over a 2-mm gap at atmospheric pressure and temperature.33 The values for high-frequency rf voltages are slightly greater, and our device with a 1.88-mm gap sustains up to 100% H2 at DV = 4.6 kV and ~92% H2 (versus ~50% He in He/N2) at the maximum DV = 5.4 kV - the highest ever reported.7,24 Given that N2, CO2, or SF6 resist breakdown better33 than H2, nearly all mixtures of H2 with those gases can be employed without breakdown.

As H2 molecules (M = 2 Da) have half the mass of He, the mobilities of large ions with same Ω in H2 are 21/2 = 1.41 times those in He. While early fundamental studies of the mobilities for smallest ions included H2 and its mixtures,38–41 analytical IMS has not, and no cross sections of larger ions with H2 have been measured. These should somewhat exceed Ω with He because diatomic H2 is larger and more polarizable (α = 0.82 Å3), resulting in deeper ion-molecule potentials. However, H2 is smaller and less polarizable than N2, meaning shallower potentials and smaller Ω values. Thus, the difference of Ω between He and H2 should be less than the ~1.1 – 1.5 times between He and N2, and mobilities in H2 are likely greater than those in He, at least for relevant larger ions where Ω depends on the gas only weakly. Hence the peaks for such ions in FAIMS using H2/N2 mixtures should be slightly (up to ~15%) narrower than those in He/N2 with same N2 fractions.

Much more important is the ability to operate at up to ~100% H2, impossible with He as we explained. For the same Ω, the mobilities in H2 exceed those in N2 by 141/2 = 3.74 times, respectively, as opposed to the (Blanc-law) factor of 1.45 in He/N2 with a maximum of 50% He at DV = 5.4 kV. Considering the smaller cross sections in H2 than in N2, the mobilities in H2 should be ~4 – 5 times those in N2, vs. the said 1.5 – 1.6 times in 1:1 He/N2. Thus, substituting H2 for He in mixtures with N2 should increase K values by up to ~2.7 – 3.1 times, further narrowing the spectral peaks by ~1.6 – 1.8 times. With 90% H2 workable at the maximum DV here, the calculated mobilities are somewhat smaller at ~3 – 4 times those in N2 and ~2 – 2.5 times those in 1:1 He/N2, hence the peak narrowing relative to the latter would be a lesser ~1.4 – 1.6 times.

As we mentioned, R and p are proportional to EC and separation space, respectively. Experiments for representative analytes (below) prove that EC values and thus separation space widths in He/N2 and H2/N2 are close for He or H2 concentrations up to 50%. However, as the H2 fraction goes to 100%, the EC values far exceed those for He/N2 with 50% He, adding to the advantage of narrower peaks. As a result, much higher FAIMS resolving power can be attained in equal time using H2/N2 than He/N2 compositions.

Ion beams in gases are broadened by diffusion and space-charge expansion due to Coulomb repulsion.42 The former is independent of the ion density σ, while the latter scales as σ2. The σ value in FAIMS is limited by Coulomb expansion eliminating excess ions, thus diffusion dominates.42 For optimum performance, the effective gap width ge in a FAIMS device (mechanical width g less the amplitude of ion oscillations in the waveform cycle d) must compare3 with the beam broadening during filtering time t. As D and K values are approximately proportional at moderate E, the beams spread in H2 much faster than in N2 or permissible He/N2 mixtures - by ~3 times relative to 1:1 He/N2 based on the mobilities estimated above (and actually more because of enhanced field heating of the ions). The value of d is proportional to mobility and thus is scaled by the same factor. For many polyatomic ions with1K ~ 1 – 2 cm2/(Vs) in N2, this means going from d ~ 0.15 – 0.3 mm in 1:1 He/N2 to d ~ 0.4 – 1 mm in H2 (for the present 2:1 bisinusoidal waveform with DV = 5.4 kV and 750 kHz frequency). With unchanged g ~ 2 mm, nearly all ions for species with K > ~1.2 cm2/(Vs) are non-selectively destroyed on electrodes over the typical t = 0.2 s. This limits the H2/N2 mixtures in that regime to ~55 – 80% H2 for many analytes, which caps the resolution gains provided by H2 in existing devices not designed for such buffers. With the diffusional broadening scaling as (Dt)1/2, the ge value suitable for 1:1 He/N2 gas has to be raised by at least ~60 – 80% for H2, e.g., from the present ~1.6 – 1.7 mm to ~2.6 – 3.1 mm. This increase translates into an increase of physical width from ~1.9 mm to ~3.2 – 3.8 mm (at least). Then, for constant E, one has to scale DV in proportion, i.e., from 5.4 kV to ~9 – 11 kV.

A FAIMS unit with 2 mm gap can, in principle, utilize higher H2 fractions with faster separations. For same ion transmission efficiency, one would have to decrease t by a factor of 1/D (or ~3 times as estimated above for H2 versus 1:1 He/N2) had the oscillation amplitude remained constant. The greater d value computed above decreases the effective gap width by ~15 – 40% (from ~1.6 – 1.7 mm in 1:1 He/N2 to ~0.9 – 1.5 mm in H2). To compensate, t is to be shortened by further ~1.4 – 3 times (or ~4 – 10 times total), i.e., from 0.2 s to 20 – 50 ms. This would be achieved by increasing the rate of gas flow to the device, presently from Q = 2 L/min (for t = 0.2 s) to ~8 – 20 L/min. However, the pumping constraints (experimental section) have precluded Q > 2.4 – 2.7 L/min at high H2 fractions. According to the above square-root scaling, the consequent reduction of t by ~1.2 – 1.35 times (to 0.15 – 0.17 s) broadens the peaks by ~10 – 15%, less than the benefit of higher ion mobilities that we estimated as ~1.6 – 1.8 times for H2 and ~1.4 – 1.6 times for 9:1 H2/N2. Hence both higher resolution and faster separation are achievable. With that, we move to the experimental evaluation for representative analytes.

Demonstration of FAIMS Analyses in Hydrogen

A widely used standard in IMS and FAIMS is reserpine, which commonly contains 3,4-dehydroreserpine due to oxidative dehydrogenation.43 In positive-mode ESI, these produce 1+ protonated ions with m/z = 609 and 607, respectively. As the H2 fraction grows from 0 to 80%, the FAIMS resolution of these species in t = 0.2 s increases 9-fold (from r = 1.1 to 9.7) as the peaks narrow while the distance between them expands (Fig. 1). Even higher r ~ 15 – 16 were reached at 80 – 88% H2 using t = 0.27 – 0.4 s, which is still shorter than 0.6 s needed for the maximum resolving power in He/N2 mixtures. The EC values in H2/N2 mixtures are close to those in He/N2 up to 50% H2 or He, but at the near-maximum 90% H2 exceed the highest in He/N2 (at 50% He) by 1.9 times (Fig. 2a). The flattening of curve at ~90% H2 portends the EC decrease at higher H2 fractions, suggesting that those would not improve separation even if the electrical breakdown could be averted. As anticipated from calculations, the peaks measured using H2/N2 in t = 0.2 s are somewhat narrower than those using He/N2 mixtures for equal t and N2 content (in the region of overlap), and the widths for >50% H2 lie on the extrapolation of the trend up to 50% H2 (Fig. 2b). The values for t > 0.2 s adjusted to t = 0.2 s via multiplication by (t/0.2 s)1/2 track the same trend, also in agreement with theory. With t = 0.2 s, the resolving power exceeds that using He/N2 already at 50% H2 (because of narrower peaks) and rapidly increases at higher H2 fractions as EC values escalate - to 105 (or >3 times that in 1:1 He/N2)24 at 85% H2 (Fig. 2c). The results at 85% H2 and t = 0.4 s were verified by 20 replicates, yielding a mean w = 0.755 ± 0.031 V/cm with 95% confidence (Fig. S2) and R = 159 ± 7, which is 2.6 times that achieved36 using 1:1 He/N2 despite a longer t = 0.6 s. The value for dehydroreserpine is yet greater, R = 176. The resolution of different species improves in proportion (Fig. 1). Such resolution gains despite faster separation evidence the potential for FAIMS in H2-rich mixtures.

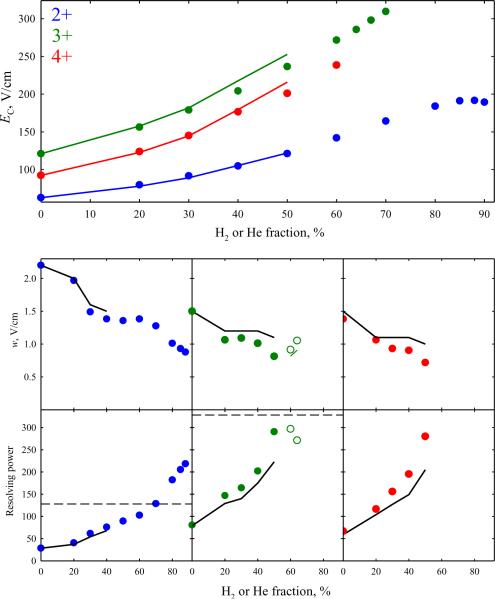

Fig. 1.

Spectra for 1+ reserpine and 3,4-dehydroreserpine ions measured using DV = 5.4 kV in H2/N2 with 0 – 90% H2 and filtering times as labeled. The peak resolution values are marked. Data for more H2 fractions are shown in Fig. S1.

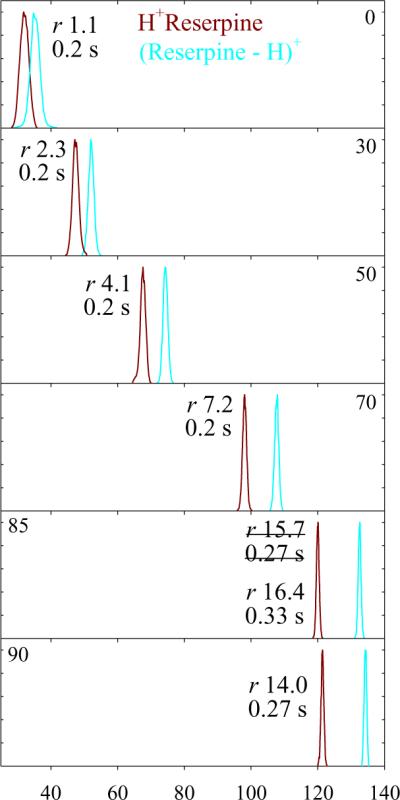

Fig. 2.

Separation properties for reserpine from Fig. 1 and those measured in He/N2 mixtures24 using the “standard” t = 0.2 s: compensation field (a), peak width (b), and resolving power (c). Black lines are for He/N2, circles are for H2/N2: filled for t = 0.2 s, blank (b, c) for t = 0.27 – 0.4 s. The brown line in (b) shows the widths adjusted to t = 0.2 s as explained in the text. The dashed line in (c) marks the maximum R achieved36 with He/N2 mixtures (using t = 0.6 s).

More topical are separations of peptides, especially isomers such as those derived from proteolytic digestion of isomeric proteins ubiquitous in biology.25,26,44,45 Their major categories are sequence inversions where residues are transposed,26 and localization variants where post-translational modifications (PTMs) are moved along the backbone.25 These isomers normally differ in biological activity, but are often challenging to characterize by tandem MS using ergodic methods such as collision-induced dissociation (CID). This is the case for sequence isomers with basic amino acids or permuted N-terminal and next residues.26,44 Particularly difficult are inversions of modified peptides with “electron predator” PTMs such as nitrate, which are preferentially abstracted during CID and produce uninformative fragments upon electron capture or transfer dissociation (EC/TD).26,46,47 For localization variants, CID again causes PTM abstraction with uninformative fragments and PTM migration that yields misleading fragments, while EC/TD is inefficient and non-specific, leading to low sensitivity.25,45 Mixtures of three or more variants cannot be characterized by MS/MS (either CID or EC/TD) in principle because of the absence of unique fragments for at least one isomer.25,45,48 Separation of peptide isomers prior to MS are thus called for, yet known chromatographic approaches to that are slow, require extensive method development, and frequently do not deliver satisfactory resolution.49 Such species were recently separated using FAIMS with He/N2 mixtures,25,26 and we evaluate the utility of H2/N2 for this application below.

The tryptic peptide nYAAAAAAK (782 Da), where nY is nitrotyrosine, has seven tryptic sequence isomers that were distinguished by FAIMS using He/N2 mixtures (albeit not easily).26 For example, AAnYAAAAK (3) and AAAnYAAAK (4) were baseline-resolved as 1+ ions only at extended filtering times (at least 0.33 s), Fig. 3. The resolutions of 3 and 4 obtained26 in He/N2 with 40% He at t = 0.2 and 0.33 s are matched using H2/N2 with 40% and 60% H2, respectively, at t = 0.2 s. In line with the results for reserpine, adding H2 up to 88% about doubles the R and r values at a similar filtering time.

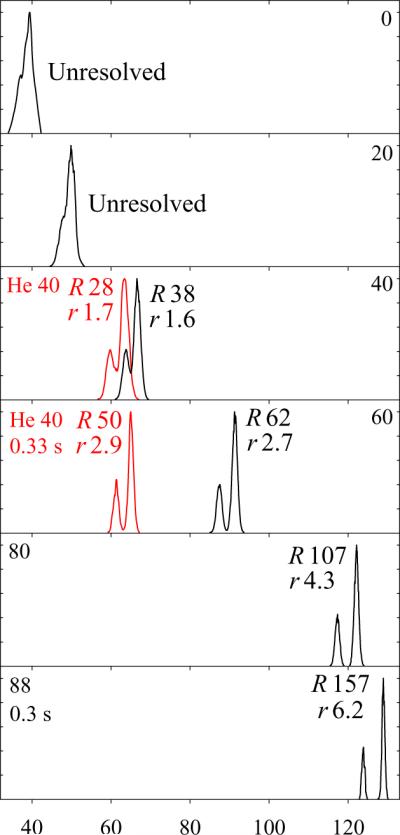

Fig. 3.

Separation of 1+ protonated nitropeptide isomers 3 and 4 (with nY shifted by single residue) in H2/N2 mixtures with 0 – 88% H2, as labeled, and filtering times of 0.2 s up to 80% H2 and as stated for >80% H2 (black lines). For comparison, the spectra in 40:60 He/N2 obtained26 using t = 0.2 s and 0.33 s are added (red lines) to the panels with similar peak resolution in H2/N2. The isomer 3 always has a lower EC. The R and r values are marked. Date for more H2 fractions are shown in Fig. S4.

Modern proteome analyses mainly involve ESI and related ion sources that tend to generate multiply protonated peptides, commonly with the charge state (z) of 2. Conformational, sequence, and localization isomers of peptides with z = 2 – 4 were separated by FAIMS in He/N2 with resolving power and resolution generally superior8,23–26,45 to those for z = 1. Resolution of multiply-charged peptides may be investigated using Syntide 2 (1508 Da) that produces abundant 2+, 3+, and 4+ ions in ESI and served as a benchmark in our FAIMS studies8,23–26,45 in He/N2. The higher mobilities of 2+ and particularly 3+ and 4+ peptides50 bring about their faster elimination from the gap compared to 1+ peptides, effectively limiting the H2 content for z = 3 and 4 to less than 90%, namely ~70% for z = 3 and ~60% for z = 4. For the same reason, we could not employ extended t to maximize the resolving power for these peptides at higher H2 fractions, and actually had to use t < 0.2 s to measure the data for z = 3 and 4 at ~60 – 70% H2.

At t = 0.2 s, the maximum EC values (obtained at or near the highest possible H2 fractions) exceed those in 1:1 He/N2 for all z: by ~60% for z = 2 and ~10 – 20% for z = 3 and 4 (Fig. 4). The smaller increases for 3+ and particularly 4+ ions are consequent upon a lower maximum H2 content, as the absolute EC values would be higher at ~85 – 90% H2. In other aspects, the findings follow the trends for 1+ ions noted above: the peak widths in H2/N2 mixtures are slightly below those24 in He/N2 with equal N2 fractions up to the maximum He content (50%), then decrease along the same linear trends until t has to be reduced, and then stay roughly level. As a result, the maximum resolving powers at t = 0.2 s exceed those obtained24 using He/N2 mixtures by ~3 times (R ~ 200 vs. ~70) for z = 2 and ~30 – 40% (R ~ 280 – 300 vs. ~200 – 220) for z = 3 and 4 (Fig. 4). These metrics were validated by replicate analyses (Fig. S4), yielding a mean w = 1.03 ± 0.064 V/cm and R = 185 ± 12 for z = 2 using 84% H2 and mean w = 0.818 ± 0.060 V/cm and R = 291 ± 21 for z = 3 using only 50% H2 (at 95% confidence). For z = 2, the maximum R achieved here is greater than ~130 reached36 in He/N2 using the longest feasible t = 0.5 s. The diminishing benefit of H2 substitution for higher peptide charge states at least partly results from increasing K values that preclude the highest H2 fractions with the current restricted gaps. This is a limitation of the present device rather than the H2/N2 medium per se, and can likely be remedied by widening the gap as specified above.

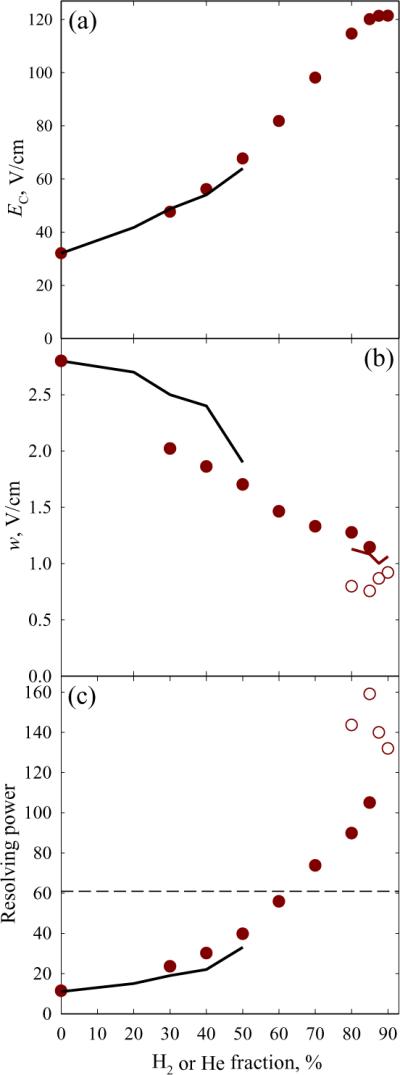

Fig. 4.

Separation properties for major peaks of protonated Syntide 2 with z = 2 – 4 in H2/N2 and He/N2 mixtures: compensation field (top panel), peak widths (middle row), and resolving power (bottom row). Black lines are for the data24 in He/N2 and circles are for H2/N2: filled for t = 0.2 s, blank (middle and bottom rows) for z = 3 at t = 0.15 – 0.16 s. The green line (middle row) shows the peak widths for z = 3 upon adjustment to t = 0.2 s as explained above. The dashed lines (bottom panel) indicate the maximum R achieved36 for z = 2 and 3 with He/N2 mixtures (using t = 0.5 s).

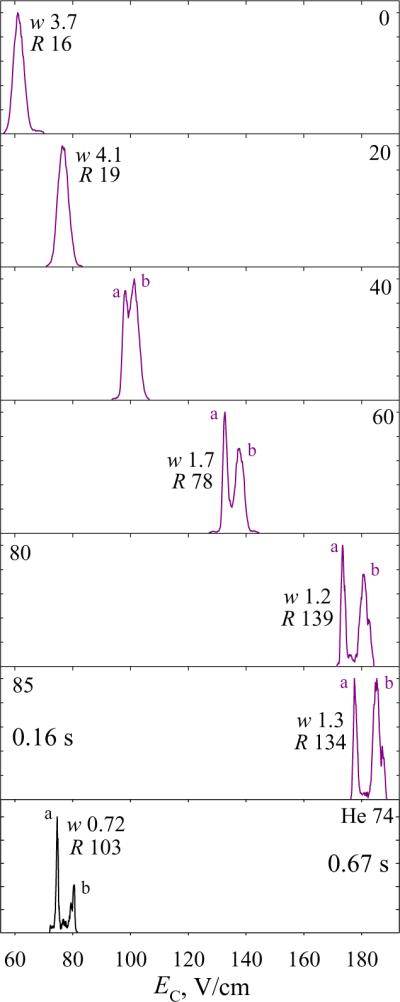

Gas-phase peptides commonly exhibit multiple conformers, some mirroring those in solution.51 Their separation and characterization is of interest for structural biology and investigations of protein misfolding disorders.52 To gauge the utility of hydrogen-based media for separating peptide conformers (in particular, multiply-charged ones), we explored the 2+ ions of bisphosphorylated45 APLpSFRGSLPKpSYVK (1809 Da), Fig. 5. As with Syntide 2, the EC values increase upon H2 addition, while peak widths decrease with fixed t and remain constant with reduced t at >80% H2. These gains translate into better resolution, with the conformers (a) and (b) separated increasingly well. The spectrum at 70% H2 resembles that in He/N2 with the maximum He content,36 while those at 75 – 85% H2 exhibit slightly better resolution despite a fourfold acceleration of analysis. Using He/N2, (a) and (b) could be only partly resolved in t = 0.2 s.36,45 Thus FAIMS in H2-rich mixtures allows faster filtering singly or multiply-charged peptides with specificity close to or exceeding that in He/N2. The relative separation of both primary and secondary structure isomers tracks that in He/N2.

Fig. 5.

Spectra for 2+ ions of protonated APLpSFRGSLPKpSYVK in H2/N2 mixtures with 0 – 85% H2, as labeled, and (bottom panel)36 He/N2 using DV = 4 kV and 74% He - the maximum avoiding an electrical breakdown. The filtering times were 0.2 s up to 80% H2. The widths (V/cm) and resolving power values are given for the major peaks. Data for more H2 fractions are shown in Fig. S5.

Increasing the He fraction in mixtures with N2 or other heavier gases accelerates ion diffusion, which reduces the ion transmission through planar gaps and thus FAIMS sensitivity. The effect is greater with H2 mixtures because of somewhat faster diffusion as discussed above and higher possible light gas fractions. For example, moving from 0 to 80% H2 decreased the reserpine ion counts by ~3 – 4 times (at t = 0.2 s), and the losses for more mobile ions were steeper such that the signal often vanished by ~60 – 70% H2 as we described. However, addition of H2 must also affect the ESI desolvation efficiency (especially as the emitter voltage and geometry were varied at high H2 content) and reduce ion transmission through the FAIMS inlet, FAIMS/MS junction, MS inlet capillary, and whole MS system flooded with H2 at abnormal pressure near the boundary of operating envelope. Deconvoluting those phenomena is beyond the scope of this work, but redesigning the FAIMS unit as explained above and optimizing the MS platform for H2 aspiration through raised pumping capacity and other changes is expected to improve the sensitivity of FAIMS/MS analyses employing either helium or hydrogen.

Conclusions

Replacing helium in He/N2 and other FAIMS carrier gases with hydrogen relaxes the electrical breakdown constraint on the lighter gas fraction. This removes the risks to equipment, improves system stability, and substantially raises the resolving power while reducing the ion filtering time up to fourfold. In particular, 176 for dehydroreserpine (1+) and 185 for Syntide 2 (2+) demonstrated here (with statistical confirmation) are the highest R values reported for singly and doubly charged ions. The spectral profiles for various species in H2/N2 mixtures are close to those in He/N2, and greater resolving power directly translates into the resolution and peak capacity gains that rapidly increase at H2 fractions above 50%. The H2/N2 mixtures suffer no electrical breakdown up to ~92% H2 even at the maximum DV = 5.4 kV here, and separations improve up to ~90% H2 (where EC values for many species start dropping). However, the mechanical and electrical constraints of the present FAIMS design limited the H2 content in H2/N2 for many analytes to ~55 – 80%, with lower values for more mobile ions. This circumstance reduced the benefit of H2 for highest-mobility ions, such as 3+ and 4+ peptides. This problem can be addressed by optimizing the analyzers, and moving toward ~90% H2 should further improve separation power and/or speed.

Media rich in H2 can be useful for FAIMS alone and platforms involving other stages such as MS, conventional IMS,53 and/or various spectrometries.54 The acceleration of scanning should facilitate the use of FAIMS in conjunction with LC. Additionally, H2 is cheaper than He and can be generated from water at little cost beyond a one-time expense of commercial equipment. The reduced operating cost and availability of H2 on demand from compactly stored materials or ambient water should make high-resolution FAIMS devices more practical and portable.

The relatively low weight, power requirements, and ruggedness of IMS and FAIMS analyzers make them attractive for in situ characterization of outer space objects and their atmospheres, and several such missions are contemplated.55 In this context, FAIMS using hydrogen-rich media may be ideal for probing exoplanet atmospheres with dominant H2 fractions (e.g., ~87 – 96% for the Jupiter and Saturn).56,57

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ron Moore, Karl Weitz, Heather Brewer, and Dr. Keqi Tang for help in the lab, Dr. Andrew Creese and Prof. Helen Cooper (Birmingham, UK) for the peptide samples, and Dr. David Koppenaal for discussions. Portions of this research were supported by the NIH National Center for Research Resources (RR18522) and Battelle. Work was performed in the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, a US DoE OBER national scientific user facility at PNNL.

References

- 1.Eiceman GA, Karpas Z. Ion Mobility Spectrometry. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mason EA, McDaniel EW. Transport Properties of Ions in Gases. Wiley, NY: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shvartsburg AA. Differential Ion Mobility Spectrometry. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilkins CL, Trimpin S, editors. Ion Mobility Spectrometry - Mass Spectrometry: Theory and Applications. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guevremont R. J. Chromatogr. A. 2004;1058:3–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pringle S. D., Giles, K., Wildgoose JL, Williams JP, Slade SE, Thalassinos K, Bateman RH, Bowers MT, Scrivens JH. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2007;261:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shvartsburg AA, Li F, Tang K, Smith RD. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:3706–3714. doi: 10.1021/ac052020v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shvartsburg AA, Tang K, Smith RD. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:32–35. doi: 10.1021/ac902133n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruotolo BT, McLean JA, Gillig KJ, Russell DH. J. Mass Spectrom. 2004;39:361–367. doi: 10.1002/jms.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker ES, Clowers BH, Li F, Tang K, Tolmachev AV, Prior DC, Belov ME, Smith RD. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2007;18:1176–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asbury GR, Hill HH. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:580–584. doi: 10.1021/ac9908952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beegle LW, Kanik I, Matz L, Hill HH. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:3028–3034. doi: 10.1021/ac001519g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matz LM, Hill H. H. Beegle, L. W., Kanik I. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2002;13:300–307. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(01)00366-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shvartsburg AA, Schatz GC, Jarrold MF. J. Chem. Phys. 1998;108:2416–2423. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnett DA, Ells B, Guevremont R, Purves RW, Viehland LA. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2000;11:1125–1133. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(00)00187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krylova N, Krylov E, Eiceman GA, Stone JA. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2003;107:3648–3654. doi: 10.1021/jp0221136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eiceman GA, Krylov EV, Krylova NS, Nazarov EG, Miller RA. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:4937–4944. doi: 10.1021/ac035502k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider BB, Covey TR, Coy SL, Krylov EV, Nazarov EG. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:1867–1880. doi: 10.1021/ac902571u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rorrer LC, Yost RA. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2011;300:173–181. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCooeye MA, Ells B, Barnett DA, Purves RW, Guevremont R. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2001;25:81–87. doi: 10.1093/jat/25.2.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnett DA, Ells B, Guevremont R, Purves RW. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2002;13:1282–1291. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(02)00527-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cui M, Ding L, Mester Z. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:5847–5853. doi: 10.1021/ac0344182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shvartsburg AA, Danielson WF, Smith RD. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:2456–2462. doi: 10.1021/ac902852a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shvartsburg AA, Prior DC, Tang K, Smith RD. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:7649–7655. doi: 10.1021/ac101413k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shvartsburg AA, Singer D, Smith RD, Hoffmann R. Anal. Chem. 2011;82:5078–5085. doi: 10.1021/ac200985s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shvartsburg AA, Creese AJ, Smith RD, Cooper HJ. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:6918–6923. doi: 10.1021/ac201640d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shvartsburg AA, Clemmer DE, Smith RD. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:8047–8051. doi: 10.1021/ac101992d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shvartsburg AA, Tang K, Smith RD. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:7366–7374. doi: 10.1021/ac049299k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shvartsburg AA, Smith RD. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2007;18:1672–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shvartsburg AA, Smith RD, Wilks A, Koehl A, Ruiz-Alonso D, Boyle B. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:6489–6495. doi: 10.1021/ac900892u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karpas Z, Berant Z. J. Phys. Chem. 1989;93:3021–3025. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beegle LW, Kanik I, Matz L, Hill HH. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2002;216:257–268. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(01)00366-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meek JM, Craggs JD. Electrical Breakdown of Gases. Wiley, NY: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barnett DA, Ouellette RJ. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2011;25:1959–1971. doi: 10.1002/rcm.5078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barnett DA, Belford M, Dunyach JJ, Purves RW. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2007;18:1653–1663. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shvartsburg AA, Smith RD. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:23–29. doi: 10.1021/ac202386w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Venne K, Bonneil E, Eng K, Thibault P. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:2176–2186. doi: 10.1021/ac048410j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Albritton DL, Miller; T. M.; Martin DW, McDaniel EW. Phys. Rev. 1968;171:94–102. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ellis HW, Pai RY, McDaniel EW. J. Chem. Phys. 1976;64:3492–3493. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thackston MG, Eisele FL, Ellis HW, McDaniel EW. J. Chem. Phys. 1977;67:1276–1277. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takata N. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 1985;18:1795–1802. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shvartsburg AA, Tang K, Smith RD. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2004;15:1487–1498. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Awang DVC, Dawson BA, Girard M, Vincent A, Ekiel I. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:4443–4448. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winter D, Pipkorn R, Lehmann WD. J. Sep. Sci. 2009;32:1111–1119. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200800691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shvartsburg AA, Creese AJ, Smith RD, Cooper HJ. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:8327–8334. doi: 10.1021/ac101878a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones AW, Mikhailov VA, Iniesta J, Cooper HJ. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2010;21:268–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jones AW, Cooper HJ. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010;12:13394–13399. doi: 10.1039/c0cp00623h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xuan Y, Creese AJ, Horner JA, Cooper HJ. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2009;23:1963–1969. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singer D, Kuhlmann J, Muschket M, Hoffmann R. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:6409–6414. doi: 10.1021/ac100473k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valentine SJ, Kulchania M, Srebalus Barnes CA, Clemmer DE. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2001;212:97–109. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pierson NA, Valentine SJ, Russell DH, Clemmer DE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:13810–13813. doi: 10.1021/ja203895j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bernstein SL, Dupuis NF, Lazo ND, Wyttenbach T, Condron MM, Bitan G, Teplow DB, Shea JE, Ruotolo BT, Robinson CV, Bowers MT. Nat. Chem. 2009;1:326–331. doi: 10.1038/nchem.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tang K, Li F, Shvartsburg AA, Strittmatter EF, Smith RD. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:6381–6388. doi: 10.1021/ac050871x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Papadopoulos G, Svendsen A, Boyarkin OV, Rizzo TR. Faraday Discuss. 2011;150:243–255. doi: 10.1039/c0fd00004c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson PV, Beegle LW, Kim HI, Eiceman GA, Kanik I. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2007;262:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Niemann HB, et al. Science. 1996;272:846–849. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hanel R, et al. Science. 1981;212:192–200. doi: 10.1126/science.212.4491.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.