Abstract

Disruption of retinoic acid signaling causes a variety of pharyngeal arch artery and great vessel defects, as well as malformations in many other tissues, including those derived from the pharyngeal endoderm. Previous studies implied that arch artery defects in the context of defective RA signaling occur secondary to pharyngeal pouch segmentation defects, although this model has never been experimentally verified. In this study, we examined arch artery morphogenesis during mouse development, and the role of RA in this process. We show in normal embryos that the arch arteries form by vasculogenic differentiation of pharyngeal mesoderm. Using various genetic backgrounds and tissue-specific mutation approaches, we segregate pharyngeal arch artery and pharyngeal pouch defects in RA receptor mutants, and show that RA signal transduction only in pharyngeal mesoderm is required for arch artery formation. RA does not control pharyngeal mesodermal differentiation to endothelium, but instead promotes the aggregation of endothelial cells into nascent vessels. Expression of VE-cadherin was substantially reduced in RAR mutants, and this deficiency may underlie the arch artery defects. The consequences of disrupted mesodermal and endodermal RA signaling were restricted to the 4th and 6th arch arteries and to the 4th pharyngeal pouch, respectively, suggesting that different regulatory mechanisms control the formation of the more anterior arch arteries and pouches.

Keywords: Arch artery, Retinoic acid, Pharyngeal mesoderm, Pharyngeal endoderm, VE-cadherin

Introduction

Pharyngeal arch arteries are transient conduits between the heart and systemic circulation during early embryogenesis. One arch artery forms within each pharyngeal arch as the arches themselves form sequentially in a rostral to caudal direction (Hiruma et al., 2002). In normal mouse embryos at E9.5, the 1st arch arteries have already lost their connections to the outflow tract of the heart and the 2nd and 3rd arch arteries carry cardiac output; the 4th and 6th arch arteries have not yet formed at this time. By E10.5, the 2nd arch arteries are no longer connected to the outflow tract, and the 3rd, 4th, and 6th arch arteries carry blood flow. Starting from E11, these become asymmetrically reorganized into the great vessels of the heart. Defects in arch artery formation and reorganization lead to a variety of congenital great vessel defects that are prominent in the human population.

The endothelium of the arch arteries is derived from pharyngeal mesoderm, whereas their smooth muscle is derived from neural crest. Between each pharyngeal arch, the haryngeal endoderm is organized into pouches that form or contribute to several pharyngeal organs, including the thymus and parathyroids (3rd pouch) and the ultimobranchial bodies (4th pouch). Pharyngeal organ and arch artery defects often occur together, possibly because of the close physical relation of the pharyngeal pouches and arch arteries and their potential interactions during development.

Retinoic acid (RA) is a vitamin A derivative that is widely used as a signaling molecule in vertebrate development. The RA receptor is a heterodimer of RAR and RXR, both members of the nuclear receptor family of ligand-dependent transcription factors. In humans and mice, there are three RAR genes and three RXR genes (identified as α, β, and γ), and each gene gives rise to two major isoforms (numbered 1 and 2) based on alternative promoter utilization. Great vessel defects occur in many experimental models of compromised RA signaling, including several different mouse mutant backgrounds (Mendelsohn et al., 1994; Lee et al., 1997; Dupe et al., 1999; Niederreither et al., 2003), nutritional vitamin A deficiency in rat embryos (Wilson and Warkany, 1949), and treatment of mouse embryos with a pan-RAR antagonist (Wendling et al., 2000). Many additional malformations occur in these models as well. A primary target of RA signaling is the pharyngeal endoderm, and many perturbations of RA signaling cause defective 3rd and 4th pharyngeal pouch formation and consequent pharyngeal organ defects (Mulder et al., 1998; Wendling et al., 2000; Matt et al., 2003; Niederreither et al., 2003; Kopinke et al., 2006; 4 Bayha et al., 2009). Arch artery defects in embryos with compromised RA signaling have been concluded to result indirectly from an initial perturbation in pharyngeal endoderm structure (Wendling et al., 2000) or signals (Mark et al., 2004, 2009).

A limitation of past studies has been the lack of conditional mutagenesis approaches to directly test the tissue-specific functions of RA signaling. In this study, we examined arch artery development in several RA receptor mutant backgrounds, with particular attention to addressing the previously-implied explanation for arch artery abnormalities as resulting indirectly from primary defects in the pharyngeal endoderm. Using tissue-specific mutagenesis, we have segregated pharyngeal artery and pouch defects seen in RAR mutant embryos. We confirm that RA signaling in pharyngeal endoderm supports pharyngeal pouch morphogenesis. For arch artery morphogenesis, however, RA receptor function is independently required in pharyngeal mesoderm, where it promotes the assembly of endothelial precursors into nascent blood vessels.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All mouse alleles used in this study have been previously reported: Rara1 null (Li et al., 1993), Rarb null (Luo et al., 1995), conditional Rxra (Chen et al., 1998), CAGG-Cre (Hayashi and McMahon, 2002), Mesp1Cre (Saga et al., 1999), Tie2Cre (Kisanuki et al., 2001), Foxa2Cremcm (Park et al., 2008), R26R (Soriano, 1999), and conditional Rara403 (Rajaii et al., 2008). Noon of the day of observation of a copulatory plug was defined as developmental day E0.5. Embryos were isolated as close as possible to 6:00 AM, noon, 6:00 PM, or midnight when specific developmental stages were obtained. The 4th and 6th arch arteries are not present at E9.5 and are functional at E10.5; similarly, the 3rd and 4th pharyngeal pouches are not morphologically apparent at E9.5 but are evident at E9.75 and expanded at E10.0.

Tamoxifen-induced gene knockout

Pregnant females were treated with a single intraperitoneal injection of tamoxifen (75 mg/kg; Sigma T5648) dissolved in corn oil. For temporal analysis using CAGG-Cre, females were treated at defined times. For endoderm-specific recombination using Foxa2Cremcm, females were treated at E6.75 as described previously (Park et al., 2008).

LacZ staining

Embryos were isolated and fixed in 0.2% glutaraldehyde followed by staining in Xgal solution as whole mount preparations. Embryos were then embedded and paraffin sectioned, followed by nuclear fast red counterstaining.

Ink injection

Embryos were isolated at E10.5 and placed in ice cold PBS. India ink (Martin’s Bombay Black, diluted in PBS as needed) was injected into the ventricle through a pulled glass micropipet until the small vessels were stained. The embryos were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS overnight.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Embryos were isolated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS overnight, then dehydrated and embedded in paraffin or OCT for sectioning. Primary antibodies used in this study were calcitonin (Abcam ab45007), PECAM1 (BD Pharmagen 553370), Vegfr2/Flk1 (R&D Systems AF644), SM22 (Abcam ab10135), and VE-cadherin (BD Pharmagen 550548). For immunohistochemistry, the sections were followed by biotinylated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz) and HRP-coupled streptavidin (Jackson Immunologicals), and DAB staining (Invitrogen) and hematoxylin counterstaining. For immunofluorescence, chromophore-labeled secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were used.

In situ hybridization

As described previously (Li et al., 2010), embryos were fixed in 4% PFA and paraffin-sectioned or processed as whole mount. ISH probe sequences included for parathyroid hormone positions 29–535 of NM_020623.2 (provided by N. Manley) and for Pax1 positions 1027–1466 of NM_008780.2. Probes were labeled by digoxygenin (DIG, Roche) and signal was detected by AP-coupled anti-DIG primary antibody and BM Purple substrate.

Cytospin

The 4th and 6th pharyngeal arch regions of E10.0 embryos were isolated as single tissue fragments in cold PBS by manual dissection. Tissue was dissociated using 1mg/ml collagenase IV digested for 10 min at 37°C, then washed with PBS. The cell suspensions were resuspended in 0.4 ml PBS and deposited onto slides using a Cytospin apparatus, then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 15 min, and labeled by immunofluorescence staining.

Results

RA regulates the initial formation of pharyngeal arch arteries

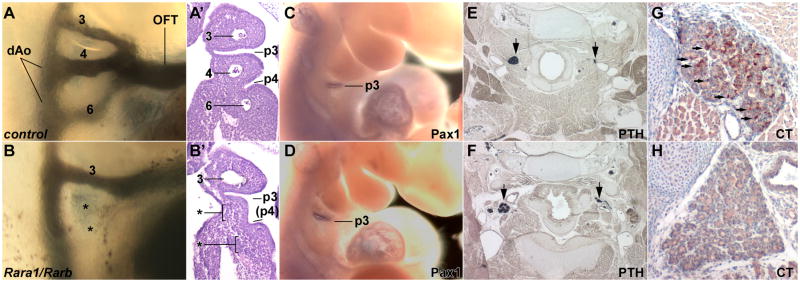

Embryos lacking the α1 isoform of the Rara gene are completely normal, whereas embryos globally lacking RARα1 plus all isoforms of the Rarb gene (designated as Rara1/Rarb) or lacking RARα1 and RXRα (Rara1/Rxra) have a variety of great vessel malformations (Lee et al., 1997); similar vascular defects have been observed in other contexts where RA signaling has been disrupted (Wilson and Warkany, 1949; Mendelsohn et al., 1994; Wendling et al., 2000; Niederreither et al., 2003). We injected ink into the hearts of E10.5 embryos to visualize the developing vasculature in the Rara1/Rarb mutant background. In normal embryos at this stage, the 3rd, 4th, and 6th arch arteries are present bilaterally. In all Rara1/Rarb mutants, we observed bilateral absence or hypoplasia of the 4th and/or 6th arch arteries (Fig. 1A–B, Table 1); 3rd arch artery defects were never observed. In most cases, one vessel was missing on each side, although occasionally, the 4th and 6th arch arteries were both missing on one side (Fig. 1B) with only one missing on the other side. There was no overall bias in which of the two vessels was impacted and there was no concordance in which vessels were missing from one side of an embryo to the other. The spectrum and frequency of these arterial defects at E10.5 are consistent with our prior inferences based on the mature vascular pattern at E14.5 (Lee et al., 1997). These observations show that the great vessel defects are caused by compromised early formation of the arch arteries.

Fig. 1.

Pharyngeal morphogenesis in RAR mutants. Upper row images are of control embryos, lower row is of Rara1/Rarb global mutants. A,B, Arch artery organization in E10.5 embryos visualized by ink injection. In this mutant (B), note the absence of the 4th and 6th arch arteries (indicated by asterisks). A′, B′, Frontal sections of the same embryos as in panels A and B, showing normal 3rd pouch but defective 4th pouch formation in a mutant (B′), and also showing the absence of the 4th and 6th arch arteries. This example of defective 4th pouch formation is of an intermediate severity; in other mutant embryos there was no 4th pouch formed whatsoever. C,D, In situ hybridization at E10.5 for Pax1, a marker of the 3rd pouch at this stage. E,F, In situ hybridization at E18.5 for parathyroid hormone (PTH), a marker of the parathyroids (arrows); because of section angle, only one parathyroid in each embryo is shown in full size. G,H, Immunohistochemical detection of calcitonin (CT) at E18.5 in the thyroids; arrows point to selected scattered positive cells in the control embryo, whereas the mutant is missing all such cells. Numbers, 3rd, 4th, 6th arch arteries; p3 and p4, 3rd and 4th pharyngeal pouches; (p4), a hypoplastic 4th pouch; dAo, dorsal aorta; OFT, outflow tract.

Table 1. Arch artery defects at E10.5 assessed by ink injection.

Frequency of arch artery defects in various RAR mutant backgrounds, assessed at E10.5 by ink injection. The table lists the number and of embryos in which 4th or 6th arch rtery defects were found, and whether such defects were bilateral or unilateral

| Genotype | Embryos | Bilateral defects | Unilateral defects | Normal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rara1/Rarb (global) | 12 | 12 | 100% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| CAGG-Cre/Rara1/Rxra (*) | |||||||

| E8.5 | 12 | 4 | 33% | 3 | 25% | 5 | 42% |

| E9.5 | 18 | 4 | 22% | 8 | 44% | 6 | 33% |

| E10.5† | 8 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 8 | 100% |

| Wnt1Cre‡ | |||||||

| Rara403 | 14 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 14 | 100% |

| Foxa2Cremcm § | |||||||

| Rara1/Rxra | 23 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 23 | 100% |

| Rara403 | 28 | 3 | 11% | 7 | 25% | 18 | 64% |

| Mesp1Cre | |||||||

| Rara1/Rxra | 13 | 7 | 54% | 2 | 15% | 4 | 31% |

| Rara403 | 16 | 16 | 100% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Tie2Cre | |||||||

| Rara1/Rxra | 14 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 14 | 100% |

| Rara403 | 22 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 22 | 100% |

The stages indicated represent the onset of RAR-RXR deficiency. CAGG-Cre mice were treated with tamoxifen 24 hr before the indicated times; as previously documented (Li et al., 2010), RXRα protein is essentially eliminated 24 hr after tamoxifen injection.

For CAGG-Cre/Rara1/Rxra mice treated with tamoxifen at E9.5 receptor deficiency starting from E10.5), to ensure that RA signaling is not also required later in development, E14.5 embryos were also analyzed; none of 12 embryos had any great vessel defect.

A previous study (Jiang et al., 2002) showed that Wnt1Cre/Rara1/Rxra mutants also had no cardiovascular phenotype.

All Foxa2Cremcm embryos were treated with tamoxifen at E6.75.

The CAGG-Cre transgene (Hayashi and McMahon, 2002) expresses tamoxifen-dependent Cre recombinase in a ubiquitous manner. In a previous study, we combined CAGG-Cre with a conditional Rxra allele and documented the time course of elimination of RXRα protein following a single dose of tamoxifen (Li et al., 2010). We combined the CAGG-Cre line with the conditional Rxra allele and with global deficiency of Rara1 to define the temporal requirement for RAR function in arch artery development. When RA receptor function was ablated prior to E9.5, approx. 60% of CAGG-Cre/Rara1/Rxra conditional mutant embryos had 4th or 6th arch artery defects at E10.5 (Table 1); a similar frequency of great vessel defects was also seen when embryos were analyzed by histology at E14.5 (not shown). 3rd arch artery defects were never observed in CAGG-Cre/Rara1/Rxra embryos. The incomplete penetrance of 4th and 6th arch artery defects is explained by litter to litter variation in Rxra gene recombination efficiency associated with tamoxifen treatment, and by the observation that great vessel defects are not fully penetrant in the global Rara1/Rxra double mutant background. However, when RA signaling was compromised starting at E10.5, all embryos were normal (Table 1). Thus, RA signaling is necessary for 4th and 6th arch artery morphogenesis between E9.5 and E10.5, the period during which these arteries form.

4th pharyngeal pouch defects in RA receptor mutants

To further study pharyngeal development, frontal sections of Rara1/Rarb double global mutant embryos at E10.5 were compared with littermates. In all cases, the 3rd arch arteries were properly formed, whereas missing or extremely hypoplastic 4th and/or 6th arch arteries were readily observed. (Fig. 1A′–B′).

This analysis also allowed us to examine the organization of the pharyngeal pouches. The 3rd pouch was always present in Rara1/Rarb mutants (Fig. 1 A′–B′), and Pax1, a 3rd pouch endodermal marker at this stage, was normally expressed (Fig. 1C–D). The thymus and parathyroids originate from the 3rd pouch; our previous analysis of Rara1/Rarb mutants showed normal thymic development (Lee et al., 1997), and using parathyroid hormone as a marker, we observed normal parathyroid formation in all E18.5 embryos (Fig. 1E–F). These results collectively indicate that 3rd pouch development occurs normally in Rara1/Rarb mutants.

In contrast, in all E10.5 Rara1/Rarb mutants, the 4th pouches were bilaterally compromised (Fig. 1A′–B′). In some cases, the 4th pouch was partially formed, but in all cases there was some degree of fusion of the 4th and 6th arches. The 4th pouch gives rise to the ultimobranchial body, which contributes the calcitonin-expressing cells that become distributed within the thyroid (Kameda et al., 2007). In E18.5 Rara1/Rarb mutants, we observed an absence of calcitonin immunoreactivity in the thyroid, although the organ itself was of normal morphology (Fig. 1G–H). These results confirm the severity of the 4th pouch defects in Rara1/Rarb mutants.

Because of the combined occurrence of caudal arch artery and pouch defects in Rara1/Rarb mutants, it was possible that the 4th and 6th arch arterial defects occurred as an indirect consequence of a primary defect in the 4th pouch. However, in 6/7 CAGG-Cre/Rara1/Rxra embryos with arch artery defects, pharyngeal pouch morphology was normal (Suppl. Fig. 1), although in one embryo, the 4th pouch was poorly formed (not shown). Thus, the Rara1/Rxra mutant background shows that arch artery defects can occur in the context of apparently normal pharyngeal pouch segmentation.

Segregation of RAR endodermal and mesodermal roles by conditional mutagenesis

To further address the relationship between pharyngeal arch artery and pouch morphogenesis, we combined several tissue-specific Cre drivers with the conditional Rxra allele coupled with global Rara1 deficiency. We also combined the same Cre drivers with a conditional dominant negative RAR allele (Rara403) expressed from the R26R locus (Rajaii et al., 2008). This latter strategy relies on conditional expression of a dominant negative protein that should block all RAR functions, rather than inactivation of subsets of RA receptor genes followed by potentially slow turnover of preexisting protein; it is therefore expected to more rapidly, efficiently, and comprehensively block RA signaling relative to conditional single or double receptor gene disruption. Using Wnt1Cre, we showed previously that neural crest-specific Rara1/Rxra conditional mutants had no cardiovascular defects (Jiang et al., 2002). In the present analysis, we observed that Wnt1Cre/Rara403 mutants also had no cardiovascular defects (Table 1). This confirms that neural crest cells are not direct targets for RA signaling during cardiac and arch artery development.

We used the tamoxifen-regulated Foxa2Cremcm line to address the role of RA receptors in endoderm. As previously reported (Park et al., 2008), following a single tamoxifen injection at E6.75, highly efficient endodermal recombination was evident (Suppl. Fig. 2B, D–G), although there was some variation in efficiency among embryos and between litters. Foxa2Cremcm/Rara1/Rxra conditional embryos were similarly treated at E6.75. When isolated at E10.5 and evaluated by ink injection, none of 23 treated conditional mutant embryos had any arch artery defect (Table 1); similarly, as evaluated by histology, none of 8 Foxa2Cremcm/Rara1/Rxra conditional embryos had defects in any of the pharyngeal pouches (not shown). The frequent occurrence of arch artery defects in global Rara1/Rxra mutants and in CAGG-Cre/Rara1/Rxra conditional mutants, but not in Foxa2Cremcm/Rara1/Rxra conditional mutants, implies that the combination of Rara1 and Rxra mutation selectively interferes with arch artery formation, and does so by action in a tissue other than pharyngeal endoderm.

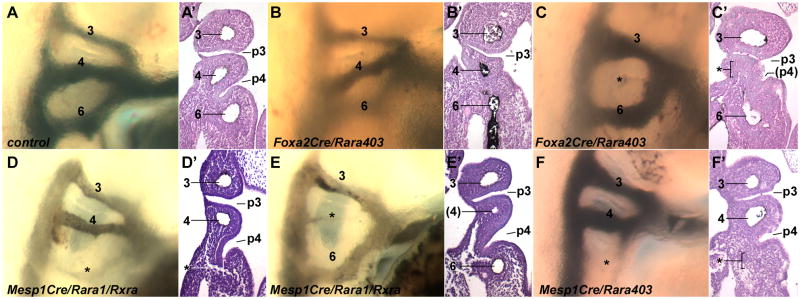

In contrast, of 11 Foxa2Cremcm/Rara403 embryos treated with tamoxifen at E6.75 and isolated at E10.5, we often observed defective 4th pouch organization (Fig. 2B′–C′): 4 embryos had bilateral 4th pouch defects, 5 had a unilateral 4th pouch defect, and 2 were normal. 3rd pouch formation in Foxa2Cremcm/Rara403 embryos was always normal. Immunostaining of the thyroid showed that half of Foxa2Cremcm/Rara403 embryos at E18.5 had no calcitonin-expressing cells (e.g., Suppl. Fig. 3B), whereas the other half had calcitonin expression ranging from highly deficient to normal (not shown); this is consistent with the frequency and severity of pouch defects seen by histology at E10.5. These results demonstrate that RA signaling in endoderm is important for 4th pouch segmentation, although with reference to the lack of pouch defects in Foxa2Cremcm/Rara1/Rxra embryos, this signaling does not require the RARα1 and RXRα receptors. In most tamoxifen-treated Foxa2Cremcm/Rara403 embryos (18 of 28), as assessed by ink injection, all pharyngeal arch arteries were present bilaterally, and the only vascular alteration was a mild perturbation in some of these in the position of the 4th arch artery (Fig. 2B), which we attribute to the missing 4th pouch. In a smaller number of cases (10 of 28), arch artery defects were observed (Fig. 2C, Table 1). Arch artery abnormalities only occurred when there were 4th pouch defects, but we found several examples of normal arch artery formation with defective 4th pouch organization (e.g., Fig. 2B, B′). Endodermal perturbation of RA signaling therefore can result in arch artery defects, but 4th pharyngeal pouch disruption does not invariably result in arterial defects.

Fig. 2.

Arch artery and pouch defects in tissue-specific RAR mutants. All embryos are at E10.5, ink injection was first used to visualize arch artery patterns, and then sections of the same embryos were taken to visualize pharyngeal organization. A, Control embryo. B,C, Two different Foxa2Cremcm/Rara403 mutants, both have a normal 3rd pouch and a severely hypoplastic 4th pouch, one has normal arch arteries (B) and one has an arch artery defect (C). D,E, Two different Mesp1Cre/Rara1/Rxra mutants, both have normal 3rd and 4th pouches, and each has an arch artery defect. F, An Mesp1Cre/Rara403 mutant, showing normal pouch formation and an arch artery defect.

In parallel, we used Mesp1Cre (Saga et al., 1999), which achieves highly efficient and specific recombination in pharyngeal mesoderm starting from very early stages (Suppl. Fig. 2A,C). As assessed by ink injection at E10.5, every Mesp1Cre/Rara403 embryo exhibited hypoplastic or absent 4th or 6th arch arteries, and always bilaterally (Table 1), and absent 4th or 6th arch arteries were observed in most (9 of 13) Mesp1Cre/RARa1/RXRa embryos (Table 1, Fig. 2D–F). Similar to global Rara1/Rarb mutants, 4th vs. 6th arch artery defects were randomly distributed in both Mesp1Cre conditional mutant backgrounds, and there was no incidence of 3rd arch artery defects in either conditional background. Equally importantly, the 4th pharyngeal pouch defects seen in global Rara1/Rarb mutants and in Foxa2Cremcm/Rara403 embryos were not seen in mesoderm-specific conditional mutants, even when arch arteries were obviously missing (Fig. 2D–F). Furthermore, in late stage mesoderm-specific RAR mutants, a normal distribution of calcitonin-expressing cells in the thyroid was observed (Suppl. Fig. 3C–D), implying normal ultimobranchial body (4th pouch) morphogenesis, and thymus morphology was also always normal (not shown). These results unambiguously demonstrate that RA receptor function in mesoderm is required for the formation of the 4th and 6th pharyngeal arch arteries. These results additionally show that disruption of mesodermal RAR function does not impact pharyngeal pouch development. Collectively, these genetic manipulations uncouple mesodermal arch artery development and endodermal 4th pouch development as independent and genetically separable processes.

The angiopoietin receptor Tie2 (TEK) is expressed in mature endothelial cells. We used Tie2Cre (Kisanuki et al., 2001) to refine the mesodermal requirement of RA signaling in arch artery morphogenesis. In 14 Tie2Cre/Rara1/Rxra conditional mutants analyzed at E10.5 (by ink injection), there were no defects in the pharyngeal arch arteries (Table 1), and in 7 embryos analyzed at E14.5 (by histology), there were no great vessel defects (not shown). Similarly, no defects in the arch arteries were observed in 22 Tie2Cre/Rara403 embryos at E10.5, nor great vessel defects in 6 embryos at E14.5. This outcome may indicate that RA receptor function in arch artery development occurs prior to or concurrent with terminal endothelial cell differentiation and Tie2 expression; alternatively, RA receptor function might occur in a nonendothelial mesodermal population of the arch.

Pharyngeal arch arteries form by vasculogenesis

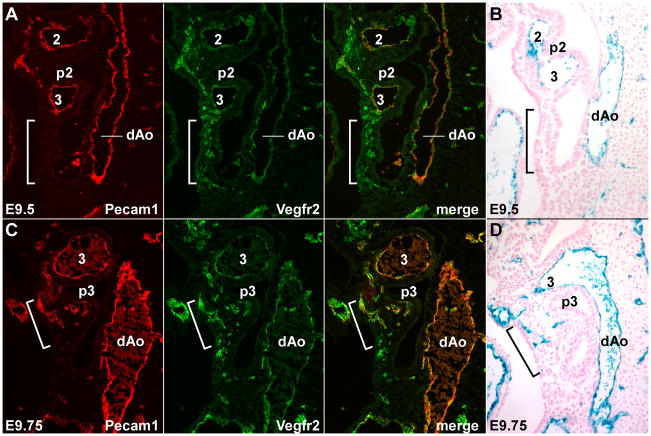

Two alternative processes have been invoked to explain the initial formation of the pharyngeal arch arteries. The angiogenesis model argues that the arch arteries form by sprouting from preexisting vessels (e.g., the dorsal aortae or the outflow tract) into the pharyngeal arch (Noden, 1990). The vasculogenesis model involves de novo differentiation of endothelial cells in the center of the arch, which form an initial tube that then extends outward bidirectionally to ultimately meet and fuse with the dorsal aorta and outflow tract (Anderson et al., 2008). To our knowledge, these models have not yet been resolved in mouse arch artery development. We used a number of molecular markers to distinguish these processes in normal mouse embryos and in order to understand the basis of arch artery defects observed in RAR mutants.

The VEGF receptor Vegfr2 (also known as Flk1) is expressed in endothelial cell progenitors (angioblasts) early in their differentiation from mesoderm; with further endothelial differentiation, these cells continue to express Vegfr2 but also initiate expression of Pecam1 and of Tie2 (Ferguson et al., 2005). In normal embryos at E9.5, the 4th and 6th arch arteries have not yet formed, and the endothelium of the dorsal aortae and the 2nd and 3rd arch arteries were double positive for Vegfr2 and Pecam1 (Fig. 3A), indicating that these are fully differentiated endothelial cells. Many Vegfr2+, Pecam1− angioblasts but no Vegfr2+, Pecam1+ endothelial cells were present at E9.5 in the posterior pharyngeal region where the 4th and 6th arch arteries will form (bracketed region in Fig. 3A); the absence of Pecam1 expression identifies these cells as angioblasts. At E9.75, Vegfr2+, Pecam1− cells were still present in this caudal region, but in addition a number of Vegfr2+, Pecam1+ cells were now present as isolated cells or in small aggregations within the forming 4th arch (Fig. 3C). By E10.5, the 4th and 6th arch arteries are functional and all endothelial cells were double positive for these markers. (Suppl. Fig. 4A). These observations imply that the caudal pharyngeal arch arteries form by vasculogenesis. Our results are not compatible with a model of angiogenic sprouting from a mature vessel into the arch, since such endothelial cells would be Pecam1+ throughout the process of arch artery formation.

Fig. 3.

Caudal pharyngeal arch arteries form by vasculogenesis. Sagittal sections through normal embryos at E9.5 (A,B) and E9.75 (C,D), showing Vegfr2 and Pecam1 immunofluorescence staining (A,C) and Tie2Cre/R26R Xgal staining (B,D). The brackets in all panels identify the region caudal to the 3rd arch, prior to (A,B) or during (C,D) formation of the 4th arch and 4th arch artery. The embryos shown in B and D are different from but at the same developmental stage as those shown in A and C, respectively.

The Vegfr2+ angioblasts seen at E9.5 could be derived by de novo mesodermal differentiation or by dedifferentiation of mature endothelial cells. We used Tie2Cre to clarify the derivation of endothelial cells in the pharyngeal arches. Tie2 is expressed beginning approximately coincident with the onset of Pecam1 expression, but is not expressed in Vegfr2+, Pecam1− angioblasts (Ferguson et al., 2005). Tie2Cre therefore marks endothelial cells that are newly differentiated as well as those derived from previously differentiated endothelium. In E9.5 Tie2Cre/R26R embryos, the endothelium of the dorsal aorta and of the anterior arch arteries was Xgal− positive, and there were no labeled cells in the region of the future 4th and 6th arch arteries (Fig. 3B). At E9.75, scattered positive cells were present in the caudal pharynx although not connected to the dorsal aorta or outflow tract (Fig. 3D). These cells presumably correspond to the Vegfr2+, Pecam1+ cells seen in the same location at the same time, as described above (Fig. 3C). If the Vegfr2+, Pecam1− angioblasts at E9.5 in the caudal pharynx were derived by dedifferentiation of mature endothelial cells (e.g., from the dorsal aorta or from the outflow tract) that migrated into the arch prior to their redifferentiation, they would remain Xgal+ throughout. The absence of Xgal+ cells at E9.5 in the region where Vegfr2+ cells are readily observed indicates instead that these cells arise by de novo differentiation of pharyngeal mesoderm.

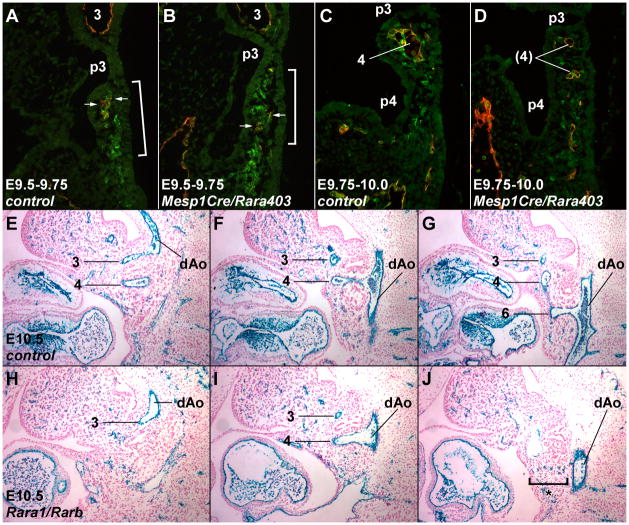

RA signaling regulates endothelial cell coalescence during arch artery vasculogenesis

We compared control and Mesp1Cre/Rara403 conditional embryos to investigate the role of mesodermal RA signaling in endothelial cell differentiation and arch artery formation. At E9.5– E10.0, in conditional dominant negative embryos, Vegfr2+, Pecam1− angioblasts were observed in a similar number and distribution within the caudal pharynx as in control embryos (Fig. 4AD). At E9.75 and later stages, a normal number of Vegfr2+, Pecam1+ differentiated endothelial cells were also present (Fig. 4C–D). In all control embryos at E9.75, Vegfr2+, Pecam1+ cells were aggregating to form a nascent blood vessel (Fig. 4C). In mutants at E9.75, we observed a range of phenotypes: in some cases, there was normal or relatively normal vessel formation (not shown), whereas in others, the Vegfr2+, Pecam1+ endothelial cells remained mostly isolated and either failed to aggregate or only formed small and scattered structures with small lumina (Fig. 4D). Similarly, in Mesp1Cre/Rara403 mutant embryos at E10.5, all Vegfr2+ cells were also positive for Pecam1, and scattered cells that were not assembled into a vessel were readily observed in some arches (Suppl. Fig. 4B). These results imply that the process of pharyngeal mesoderm differentiation, first to Vegfr2+ angioblasts and then to Vegfr2+, Pecam1+ endothelial cells, occurs normally in RAR mutants, but imply a variably penetrant defect in vascular formation starting around E9.75. This timing is consistent with our temporal analysis of RAR function using CAGG-Cre (Table 1), which implied a requirement for RA signaling between E9.5–10.5.

Fig. 4.

Normal endothelial cell differentiation but altered vessel assembly in RAR mutants. A–D, Merged Vegfr2 (green) and Pecam1 (red) immunofluorescence staining of E9.5–9.75 (A,B) and E9.75–10.0 (C,D) control vs. Mesp1Cre/Rara403 mutant embryos. These embryos are slightly more advanced than the E9.5 and E9.75 stage embryos shown in Fig. 3. Arrows in A and B point to the very small number of double positive cells at this time. E–J, Tie2Cre/R26R Xgal staining of a control (E–G) vs. a global Rara1/Rarb mutant (H–J) at E10.5; for each embryo, three sections of a series are shown, selected for passing through the 3rd (E,H), 4th (F,I), and 6th (G,J) arch and arch artery. The bracket in (J) indicates scattered Xgal+ endothelial cells that failed to form the 6th arch artery in this mutant.

To further examine this process, we evaluated Tie2Cre/R26R Xgal staining in Rara1/Rarb global mutants. In E9.5 mutants, the staining pattern in mutants was normal (e.g., with no stained cells caudal to the 3rd arch artery as in Fig. 3B; not shown). In E10.5 control embryos, the 3rd–6th arch arteries have formed and all Xgal+ endothelial cells were associated with functional vessels (Fig. 4E–G). In contrast, in RAR mutants in the arches where vessels failed to form, Xgal+ cells remained unincorporated into vessels and persisted as scattered cells (bracket in Fig. 4J). Our results suggest that RA signaling is not required for terminal endothelial cell differentiation, but rather is required for Pecam1+ and Tie2+ endothelial cells in the pharyngeal arches to coalesce into a nascent vessel.

Neural crest cells in the pharyngeal arches differentiate into the smooth muscle of the arch arteries (Jiang et al., 2000; Etchevers et al., 2001), a process that is necessary for stabilizing the newly formed vessels (Waldo et al., 1996). We previously documented normal neural crest cell migration and distribution in Rara1/Rarb global mutants (Jiang et al., 2002), and our observations of neural crest-specific RAR mutants (Table 1) show that RA signaling in neural crest cells is not necessary for arch artery development. In Mesp1Cre/Rara403 embryos at E10.5, we observed normal smooth muscle differentiation around 4th or 6th arch arteries that successfully formed, and no apparent smooth muscle differentiation when these vessels failed to form (Suppl. Fig. 5). These results suggest that the primary defect in Mesp1Cre/Rara403 mutants is in arch artery formation, and that smooth muscle differentiation by the neural crest depends on the initial formation of a vessel.

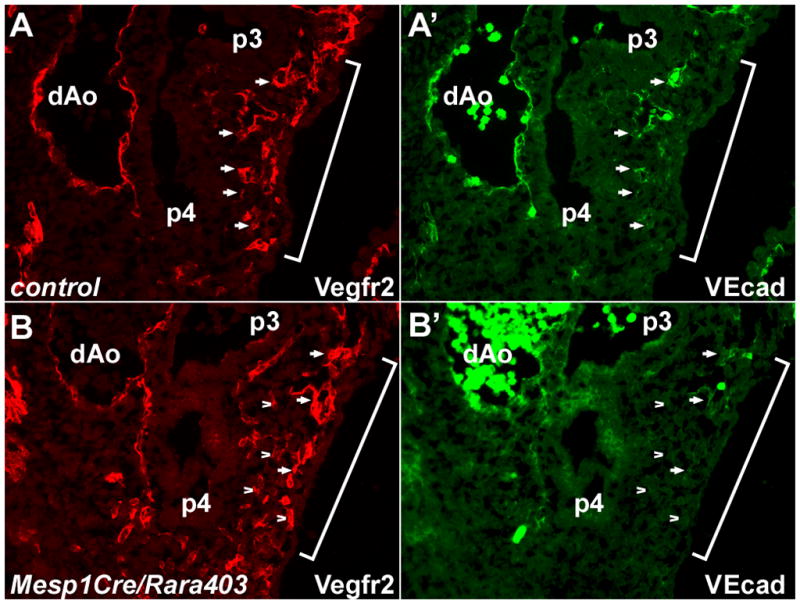

The arch artery phenotype of RAR mutants is suggestive of a defect in the process of endothelial cell adhesion and aggregation (Vestweber et al., 2009). VE-cadherin (Cdh5) is an endothelium-specific adhesion molecule that facilitates the establishment of endothelial cell contacts and communication (Vestweber, 2008). VE-cadherin is not expressed in angioblasts but is expressed in differentiated endothelial cells. In control and Mesp1Cre/Rara403 conditional mutant embryos, VE-cadherin was strongly expressed in mature functional vascular structures, such as the dorsal aortae and in properly formed pharyngeal arch arteries. In sections of control embryos at E9.75, virtually all Vegfr2+ endothelial cells in the caudal pharynx also expressed VE-cadherin (Fig. 5A). In conditional mutants, some Vegfr2+ cells expressed VE-cadherin, although the majority of Vegfr2+ cells did not (Fig. 5B). Dissociation of caudal pharyngeal arch tissue at E10.0 confirmed a reduced number of VE-cadherin+ endothelial cells in mutant embryos (Suppl. Fig. 6). RA signaling in pharyngeal angioblasts may regulate the expression of adhesion molecules such as VE-cadherin and thereby control the assembly of endothelial cells into pharyngeal blood vessels.

Fig. 5.

Deficient VE-cadherin expression in RAR mutants. Sections of E9.75 embryos are shown labeled for Vegfr2 and VE-cadherin; the brackets indicate the region of the forming 4th pharyngeal arch. In the control embryo (A), virtually all Vegfr2+ cells are also VE-cadherin+ as well (selected cells are identified by arrows for comparison registry). In the mutant embryo (B), there are some Vegfr2+, VEcad+ cells (selected examples identified by arrows), but the majority of Vegfr2+ cells are not expressing VE-cadherin (selected examples identified by arrowheads).

Discussion

The cellular and molecular events that lead to the formation of the arch arteries have been unclear. In zebrafish embryos, time-lapse cinematography demonstrated the de novo appearance of Fli (the homolog of mammalian Vegfr2) -positive cells within each arch, rather than the migration of Fli1+ cells into the arch, implying a vasculogenic process (Anderson et al., 2008). Our results support a similar vasculogenic process in mouse embryos, based on the sequential appearance of Vegfr2+, Pecam1− and then Vegfr2+, Pecam1+ cells prior to the formation of the arch arteries. We also showed using Tie2CreR26R as a lineage tracer that the initial arch artery endothelial progenitors are not derived from a previously differentiated source. Our results imply that mouse pharyngeal mesoderm undergoes vasculogenic differentiation to generate Vegfr2+ angioblasts, and that these cells then further differentiate and assemble into nascent vessels that ultimately form the arch arteries. A variant of this model that we cannot formally exclude is that Vegfr2+ angioblasts originate by mesodermal differentiation elsewhere and then migrate into the pharyngeal arches, where they then undergo further differentiation.

The primary focus of this study has been to address the role of retinoic acid signaling in this process. Prior studies argued that arch artery defects occur secondary to segmentation or signaling defects in the pharyngeal endoderm (Wendling et al., 2000; Mark et al., 2004, 2009). These models are contradicted by our genetic analysis, where we show clearly that the endodermal and mesodermal functions of RA signaling in pouch and arch artery formation are separable and distinct. Specifically, the presence of arch artery defects and the invariant absence of pouch defects in Mesp1Cre/Rara403 and Mesp1Cre/Rara1/Rxra mutants demonstrate that arch artery morphogenesis requires RA receptor function within the pharyngeal mesoderm lineage. Similarly, in endoderm-specific RAR mutants, we frequently recovered embryos in which a normal arch artery pattern occurred even when there was no 4th pouch, indicating that arch artery formation does not have an obligate dependence on pharyngeal organization or segmentation, nor on RA signaling in endoderm. We did see occasional examples of isolated arch artery defects in Foxa2Cremcm/Rara403 mutants with 4th pouch defects. Possibly, the distortion of the pharyngeal architecture caused by endodermal RAR mutation simply makes it less likely for endothelial cells to aggregate and form an arch artery.

One of the unexpected outcomes of this analysis was the selective impact of RAR disruption on only the caudal (4th and 6th) arch arteries and the caudal (4th) pouch; defects in the 3rd arch arteries and 3rd pouch were never seen. A summary of many previously studied experimental models of deficient RA signaling noted the common occurrence of 3rd–6th pharyngeal arch, 3rd –6th arch artery, and 3rd –4th pouch defects (Mark et al., 2004). It is unlikely that the absence of 3rd arch artery and 3rd pouch defects in the mutants described in our study is due to insufficient recombination by Mesp1Cre and Foxa2Cremcm in more anterior regions of the pharynx (Suppl. Fig. 2, based on Xgal staining of R26R embryos; note also that R26R is allelic to Rara403 so there should not be any difference in recombination efficiency between the two based on chromosomal location). A more likely explanation is that 4th and 6th arch artery and 4th pouch formation employ distinct regulatory programs involving retinoic acid signaling in mesoderm and endoderm that are simply not required for the formation of the more anterior pharyngeal region. One possibility is that RA signaling in pharyngeal ectoderm or neuroectoderm might support or augment 3rd arch artery and 3rd pouch morphogenesis. RA signaling in ectoderm is clearly important in hindbrain patterning (Dupe et al., 1999; Wendling et al., 2001; Serpente et al., 2005; Vitobello et al., 2011), although one study also presented evidence that hindbrain patterning per se is not responsible for endodermal or mesodermal pharyngeal defects (Niederreither et al., 2003). In our analysis, we have not considered ectodermal RA signaling and so cannot address the possibility of an ectodermal influence on anterior pharyngeal morphogenesis.

In our study, Mesp1Cre/Rara403 mutants survived to full term and were of normal size. Although we did not undertake a careful analysis outside of the pharyngeal arches, general vascular organization must have been sufficient to support organogenesis and overall embryo growth, as also previously inferred (Wendling et al., 2000). Thus, the vascular consequences of blocking mesodermal RA signaling might not only exclude the 1st–3rd arch arteries within the pharynx, but also exclude the rest of the embryo. Retinoic acid has been implicated in several aspects of endothelial cell vasculogenesis and angiogenesis (Pal et al., 2000; Suzuki et al., 2004; Ribes et al., 2007) and smooth muscle differentiation and function (Miano et al., 1996; Medhora, 2000; Kosaka et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2008). Our results do not support the developmental importance of these observations, at least within the recombination domain of Mesp1Cre for mesoderm and of Wnt1Cre for neural crest (a subset of smooth muscle). Yolk sac vasculogenesis has also been shown to be dependent on RA signaling (Lai et al., 2003; Bohnsack et al., 2004), and this was clearly not compromised in Mesp1Cre/Rara403 mutants, although vasculogenesis in the yolk sac may occur earlier than when Mesp1Cre becomes active.

Our results show that RA signaling is not involved in the differentiation of pharyngeal mesoderm to Vegfr2+ angioblasts, nor in the further differentiation of these angioblasts to Pecam1+ and Tie2+ endothelium, at least insofar as the appearance of cells expressing these markers was normal in mutant embryos. Rather, we observed a failure in endothelial cell assembly into nascent vessels as the process that is compromised in RAR mutants. Endothelial cells express several types of adhesion molecules that support their aggregation and assembly into functional vessels, including VE-cadherin (Cdh5), which promotes lumen formation and maintains endothelial cell adherens junctions (Vestweber et al., 2009). Cdh5 null mouse embryos have a grossly impaired systemic vascular organization (Carmeliet et al., 1999) and die at E9.5, prior to the formation of the caudal arch arteries. Zebrafish morphants in which VE-cadherin expression is eliminated show a similar globally defective vascular phenotype, but survive late enough to confirm that the arch arteries are also poorly formed (Montero-Balaguer et al., 2009). Deficient VE-cadherin expression may therefore underlie the arch artery defect of RAR mutants. At present, it is not clear how to interpret the deficiency of VE-cadherin expression in 4th and 6th arch endothelial cells in terms of the developmental role of RA signaling. One possibility is that VE-cadherin may be part of a separate subprogram of differentiation that is specifically regulated by RA, although RA does not control overall pharyngeal endothelial differentiation (as defined by Pecam1 and Tie2 expression). Alternatively, Cdh5 expression may be a transcriptionally regulated aspect of gene expression in pharyngeal endothelial cells. RA induces Cdh5 in a breast cancer cell line (Prahalad et al., 2010), suggesting at least the possibility of a transcriptional rather than differentiation role. If so, this mode of regulation must be narrowly constrained to the time immediately upon endothelial cell differentiation, as our genetic observations show no required function for RARs in endothelial cells that express Tie2Cre.

Our results demonstrate a stochastic component to the process of arch artery formation. In different RAR mutant backgrounds, although the frequency of arch artery defects varied, there was always a random occurrence of 4th vs. 6th arch artery defects, and no association between the left vs. right side of an embryo in terms of which vessel formed. Our observations are compatible with a model in which a rate limiting early step in the formation of an arch artery is the aggregation of a critical number of endothelial cells within an arch to form a nascent vessel. The likelihood of endothelial cells to aggregate in this manner might depend on the expression of VE-cadherin or other adhesion or signaling molecules that are controlled by mesodermal RA signal transduction, and could be indirectly compromised when pharyngeal architecture is altered (e.g., as in some Foxa2Cremcm/Rara403 embryos). The observation that some arch arteries form even when mesodermal RA signaling is completely ablated (e.g., in Mesp1Cre/Rara403 embryos) suggests that initial endothelial cell aggregation is not absolutely dependent on RA signaling. Furthermore, once an initial aggregation of endothelial cells has successfully occurred, subsequent processes presumably stabilize the vessel, allow further angiogenic extension, and support VE-cadherin expression in a way that no longer depends on RA.

Supplementary Material

Arch artery defects with normal pharyngeal pouch morphogenesis in CAGGCre/Rara1/Rxra mutants. The arch artery pattern was visualized by ink injection, and the embryo then sectioned to visualize pharyngeal organization. Note the missing 6th arch artery (asterisk) and the normal 4th pouch.

Tissue-specific recombination patterns in normal embryos. Mesp1Cre/R26R embryos (A,C) or Foxa2Cremcm/R26R embryos treated with tamoxifen at E6.75 (B,D–G) were isolated at the indicated times and Xgal stained. Unstained mesenchymal cells in sections of Mesp1Cre/R26R embryos are neural crest-derived. 1,2, 1st and 2nd arch arteries, p1–p4, 1st – 4th pouches, FG, foregut. Sections in panels A–D and G are coronal, in panel F is transverse.

Thyroid calcitonin expression at E18.5. Selected immunoreactive cells are indicated by arrows in control (A) and both mesoderm-specific RAR mutant backgrounds (C–D). In this example of a Foxa2Cremcm/Rara403 embryo (B), there are no calcitonin-positive cells present, although in other such mutants, positive cells were detected at variable levels (see text).

Vascular differentiation at E10.5. A. Sections of a normal embryo at E10.5 were stained to visualize Vegfr2 and Pecam1; virtually all labeled cells are positive for both markers at this stage. Compare to earlier stages shown in Fig. 3. B. Sections of a Mesp1Cre/Rara403 mutant at E10.5; all labeled cells are positive for both markers, and scattered double positive cells persist in the 4th arch where the 4th arch artery failed to form (asterisk and bracket).

Smooth muscle differentiation at E10.5. Shown are a control embryo (A) and two Mesp1Cre/Rara403 mutants, one with a missing 6th arch artery (B) and one with a missing 4th arch artery (C). Upper panels show the vascular pattern as visualized by ink injection. Lower panel shows merged immunofluorescence detection in sections of the same embryos using Pecam1 (red) and the smooth muscle marker SM22 (green). Red and green signals are adjacent around functional vessels, whereas there is no SM22 expression in the vicinity of endothelial cells that fail to form a vessel (brackets).

Quantitation of VE-cadherin expressing cells. Pharyngeal tissue from E10.0 embryos was manually dissected and dissociated, then spun onto slides for immunostaining. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). A. An example of one field of cells showing 6 Vegfr2+ cells, two of which are also positive for VE-cadherin expression (arrows) and four that are not (arrowheads). B. Quantitation of antigen expression. The percentages of Vegfr2+ cells that were also VE-cadherin+ in pharyngeal region cell suspensions from control (n=6 embryos) and Mesp1Cre/Rara403 mutants (n=5) were measured. There were no VE-cadherin+ cells that were not also Vegfr2+. *, statistically significant (p=0.02 using a two-tailed t test). Because of the manual dissection technique, this assay unavoidably has a relatively high although unmeasured background of contaminating double positive endothelial cells from arteries and veins unrelated to the 4th or 6th arch arteries that were also present in the isolated tissue fragments, presumably in equal amounts regardless of embryo genotype.

Highlights.

(“Retinoic acid autonomously regulates endothelial cell coalescence in caudal pharyngeal arch artery vasculogenesis”)

Mammalian pharyngeal arch arteries form by vasculogenesis.

4th pharyngeal pouch formation requires endodermal retinoic acid (RA) signaling.

Caudal (4th and 6th) arch artery formation requires mesodermal RA signaling.

RA controls endothelial cell coalescence into nascent vessels, not differentiation.

VE-cadherin may be an effector of RA signaling in caudal arch artery formation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grant HL078891.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson MJ, Pham VN, Vogel AM, Weinstein BM, Roman BL. Loss of unc45a precipitates arteriovenous shunting in the aortic arches. Dev Biol. 2008;318:258–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayha E, Jorgensen MC, Serup P, Grapin-Botton A. Retinoic acid signaling organizes endodermal organ specification along the entire antero-posterior axis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5845. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack BL, Lai L, Dolle P, Hirschi KK. Signaling hierarchy downstream of retinoic acid that independently regulates vascular remodeling and endothelial cell proliferation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1345–1358. doi: 10.1101/gad.1184904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Lampugnani MG, Moons L, Breviario F, Compernolle V, Bono F, Balconi G, Spagnuolo R, Oosthuyse B, Dewerchin M, Zanetti A, Angellilo A, Mattot V, Nuyens D, Lutgens E, Clotman F, de Ruiter MC, Gittenberger-de Groot A, Poelmann R, Lupu F, Herbert JM, Collen D, Dejana E. Targeted deficiency or cytosolic truncation of the VE-cadherin gene in mice impairs VEGF-mediated endothelial survival and angiogenesis. Cell. 1999;98:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Kubalak SW, Chien KR. Ventricular muscle-restricted targeting of the RXRalpha gene reveals a non-cell-autonomous requirement in cardiac chamber morphogenesis. Development. 1998;125:1943–1949. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.10.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupe V, Ghyselinck NB, Wendling O, Chambon P, Mark M. Key roles of retinoic acid receptors alpha and beta in the patterning of the caudal hindbrain, pharyngeal arches and otocyst in the mouse. Development. 1999;126:5051–5059. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.22.5051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etchevers HC, Vincent C, Le Douarin NM, Couly GF. The cephalic neural crest provides pericytes and smooth muscle cells to all blood vessels of the face and forebrain. Development. 2001;128:1059–1068. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.7.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson JE, 3rd, Kelley RW, Patterson C. Mechanisms of endothelial differentiation in embryonic vasculogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2246–2254. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000183609.55154.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S, McMahon AP. Efficient recombination in diverse tissues by a tamoxifeninducible form of Cre: a tool for temporally regulated gene activation/inactivation in the mouse. Dev Biol. 2002;244:305–318. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiruma T, Nakajima Y, Nakamura H. Development of pharyngeal arch arteries in early mouse embryo. J Anat. 2002;201:15–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Rowitch DH, Soriano P, McMahon AP, Sucov HM. Fate of the mammalian cardiac neural crest. Development. 2000;127:1607–1616. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Choudhary B, Merki E, Chien KR, Maxson RE, Sucov HM. Normal fate and altered function of the cardiac neural crest cell lineage in retinoic acid receptor mutant embryos. Mech Dev. 2002;117:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00206-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameda Y, Nishimaki T, Chisaka O, Iseki S, Sucov HM. Expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin by thyroid C cells and their precursors during murine development. J Histochem Cytochem. 2007;55:1075–1088. doi: 10.1369/jhc.7A7179.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisanuki YY, Hammer RE, Miyazaki J, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Yanagisawa M. Tie2-Cre transgenic mice: a new model for endothelial cell-lineage analysis in vivo. Dev Biol. 2001;230:230–242. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopinke D, Sasine J, Swift J, Stephens WZ, Piotrowski T. Retinoic acid is required for endodermal pouch morphogenesis and not for pharyngeal endoderm specification. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:2695–2709. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaka C, Sasaguri T, Komiyama Y, Takahashi H. All-trans retinoic acid inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation targeting multiple genes for cyclins and cyclindependent kinases. Hypertens Res. 2001;24:579–588. doi: 10.1291/hypres.24.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai L, Bohnsack BL, Niederreither K, Hirschi KK. Retinoic acid regulates endothelial cell proliferation during vasculogenesis. Development. 2003;130:6465–6474. doi: 10.1242/dev.00887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RY, Luo J, Evans RM, Giguere V, Sucov HM. Compartment-selective sensitivity of cardiovascular morphogenesis to combinations of retinoic acid receptor gene mutations. Circ Res. 1997;80:757–764. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li E, Sucov HM, Lee KF, Evans RM, Jaenisch R. Normal development and growth of mice carrying a targeted disruption of the alpha 1 retinoic acid receptor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:1590–1594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Pashmforoush M, Sucov HM. Retinoic acid regulates differentiation of the secondary heart field and TGFbeta-mediated outflow tract septation. Dev Cell. 2010;18:480–485. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Pasceri P, Conlon RA, Rossant J, Giguere V. Mice lacking all isoforms of retinoic acid receptor beta develop normally and are susceptible to the teratogenic effects of retinoic acid. Mech Dev. 1995;53:61–71. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00424-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark M, Ghyselinck NB, Chambon P. Retinoic acid signalling in the development of branchial arches. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark M, Ghyselinck NB, Chambon P. Function of retinoic acid receptors during embryonic development. Nucl Recept Signal. 2009;7:e002. doi: 10.1621/nrs.07002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matt N, Ghyselinck NB, Wendling O, Chambon P, Mark M. Retinoic acid-induced developmental defects are mediated by RARbeta/RXR heterodimers in the pharyngeal endoderm. Development. 2003;130:2083–2093. doi: 10.1242/dev.00428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medhora MM. Retinoic acid upregulates beta(1)-integrin in vascular smooth muscle cells and alters adhesion to fibronectin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H382–387. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.1.H382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn C, Lohnes D, Decimo D, Lufkin T, LeMeur M, Chambon P, Mark M. Function of the retinoic acid receptors (RARs) during development (II). Multiple abnormalities at various stages of organogenesis in RAR double mutants. Development. 1994;120:2749–2771. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.10.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miano JM, Topouzis S, Majesky MW, Olson EN. Retinoid receptor expression and all-trans retinoic acid-mediated growth inhibition in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 1996;93:1886–1895. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.10.1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero-Balaguer M, Swirsding K, Orsenigo F, Cotelli F, Mione M, Dejana E. Stable vascular connections and remodeling require full expression of VE-cadherin in zebrafish embryos. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5772. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder GB, Manley N, Maggio-Price L. Retinoic acid-induced thymic abnormalities in the mouse are associated with altered pharyngeal morphology, thymocyte maturation defects, and altered expression of Hoxa3 and Pax1. Teratology. 1998;58:263–275. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199812)58:6<263::AID-TERA8>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederreither K, Vermot J, Le Roux I, Schuhbaur B, Chambon P, Dolle P. The regional pattern of retinoic acid synthesis by RALDH2 is essential for the development of posterior pharyngeal arches and the enteric nervous system. Development. 2003;130:2525–2534. doi: 10.1242/dev.00463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden DM. Origins and assembly of avian embryonic blood vessels. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;588:236–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb13214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal S, Iruela-Arispe ML, Harvey VS, Zeng H, Nagy JA, Dvorak HF, Mukhopadhyay D. Retinoic acid selectively inhibits the vascular permeabilizing effect of VPF/VEGF, an early step in the angiogenic cascade. Microvasc Res. 2000;60:112–120. doi: 10.1006/mvre.2000.2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EJ, Sun X, Nichol P, Saijoh Y, Martin JF, Moon AM. System for tamoxifeninducible expression of cre-recombinase from the Foxa2 locus in mice. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:447–453. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad P, Dakshanamurthy S, Ressom H, Byers SW. Retinoic acid mediates regulation of network formation by COUP-TFII and VE-cadherin expression by TGFbeta receptor kinase in breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaii F, Bitzer ZT, Xu Q, Sockanathan S. Expression of the dominant negative retinoid receptor, RAR403, alters telencephalic progenitor proliferation, survival, and cell fate specification. Dev Biol. 2008;316:371–382. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribes V, Otto DM, Dickmann L, Schmidt K, Schuhbaur B, Henderson C, Blomhoff R, Wolf CR, Tickle C, Dolle P. Rescue of cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (Por) mouse mutants reveals functions in vasculogenesis, brain and limb patterning linked to retinoic acid homeostasis. Dev Biol. 2007;303:66–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saga Y, Miyagawa-Tomita S, Takagi A, Kitajima S, Miyazaki J, Inoue T. MesP1 is expressed in the heart precursor cells and required for the formation of a single heart tube. Development. 1999;126:3437–3447. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.15.3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serpente P, Tumpel S, Ghyselinck NB, Niederreither K, Wiedemann LM, Dolle P, Chambon P, Krumlauf R, Gould AP. Direct crossregulation between retinoic acid receptor {beta} and Hox genes during hindbrain segmentation. Development. 2005;132:503–513. doi: 10.1242/dev.01593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Komi Y, Ashino H, Yamashita J, Inoue J, Yoshiki A, Eichmann A, Amanuma H, Kojima S. Retinoic acid controls blood vessel formation by modulating endothelial and mural cell interaction via suppression of Tie2 signaling in vascular progenitor cells. Blood. 2004;104:166–169. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestweber D. VE-cadherin: the major endothelial adhesion molecule controlling cellular junctions and blood vessel formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:223–232. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.158014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestweber D, Winderlich M, Cagna G, Nottebaum AF. Cell adhesion dynamics at endothelial junctions: VE-cadherin as a major player. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitobello A, Ferretti E, Lampe X, Vilain N, Ducret S, Ori M, Spetz JF, Selleri L, Rijli FM. Hox and Pbx Factors Control Retinoic Acid Synthesis during Hindbrain Segmentation. Dev Cell. 2011;20:469–482. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldo KL, Kumiski D, Kirby ML. Cardiac neural crest is essential for the persistence rather than the formation of an arch artery. Dev Dyn. 1996;205:281–292. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199603)205:3<281::AID-AJA8>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Han M, Zhao XM, Wen JK. Kruppel-like factor 4 is required for the expression of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation marker genes induced by all-trans retinoic acid. J Biochem. 2008;144:313–321. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvn068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendling O, Dennefeld C, Chambon P, Mark M. Retinoid signaling is essential for patterning the endoderm of the third and fourth pharyngeal arches. Development. 2000;127:1553–1562. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendling O, Ghyselinck NB, Chambon P, Mark M. Roles of retinoic acid receptors in early embryonic morphogenesis and hindbrain patterning. Development. 2001;128:2031–2038. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.11.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JG, Warkany J. Aortic-arch and cardiac anomalies in the offspring of vitamin A deficient rats. Am J Anat. 1949;85:113–155. doi: 10.1002/aja.1000850106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Arch artery defects with normal pharyngeal pouch morphogenesis in CAGGCre/Rara1/Rxra mutants. The arch artery pattern was visualized by ink injection, and the embryo then sectioned to visualize pharyngeal organization. Note the missing 6th arch artery (asterisk) and the normal 4th pouch.

Tissue-specific recombination patterns in normal embryos. Mesp1Cre/R26R embryos (A,C) or Foxa2Cremcm/R26R embryos treated with tamoxifen at E6.75 (B,D–G) were isolated at the indicated times and Xgal stained. Unstained mesenchymal cells in sections of Mesp1Cre/R26R embryos are neural crest-derived. 1,2, 1st and 2nd arch arteries, p1–p4, 1st – 4th pouches, FG, foregut. Sections in panels A–D and G are coronal, in panel F is transverse.

Thyroid calcitonin expression at E18.5. Selected immunoreactive cells are indicated by arrows in control (A) and both mesoderm-specific RAR mutant backgrounds (C–D). In this example of a Foxa2Cremcm/Rara403 embryo (B), there are no calcitonin-positive cells present, although in other such mutants, positive cells were detected at variable levels (see text).

Vascular differentiation at E10.5. A. Sections of a normal embryo at E10.5 were stained to visualize Vegfr2 and Pecam1; virtually all labeled cells are positive for both markers at this stage. Compare to earlier stages shown in Fig. 3. B. Sections of a Mesp1Cre/Rara403 mutant at E10.5; all labeled cells are positive for both markers, and scattered double positive cells persist in the 4th arch where the 4th arch artery failed to form (asterisk and bracket).

Smooth muscle differentiation at E10.5. Shown are a control embryo (A) and two Mesp1Cre/Rara403 mutants, one with a missing 6th arch artery (B) and one with a missing 4th arch artery (C). Upper panels show the vascular pattern as visualized by ink injection. Lower panel shows merged immunofluorescence detection in sections of the same embryos using Pecam1 (red) and the smooth muscle marker SM22 (green). Red and green signals are adjacent around functional vessels, whereas there is no SM22 expression in the vicinity of endothelial cells that fail to form a vessel (brackets).

Quantitation of VE-cadherin expressing cells. Pharyngeal tissue from E10.0 embryos was manually dissected and dissociated, then spun onto slides for immunostaining. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). A. An example of one field of cells showing 6 Vegfr2+ cells, two of which are also positive for VE-cadherin expression (arrows) and four that are not (arrowheads). B. Quantitation of antigen expression. The percentages of Vegfr2+ cells that were also VE-cadherin+ in pharyngeal region cell suspensions from control (n=6 embryos) and Mesp1Cre/Rara403 mutants (n=5) were measured. There were no VE-cadherin+ cells that were not also Vegfr2+. *, statistically significant (p=0.02 using a two-tailed t test). Because of the manual dissection technique, this assay unavoidably has a relatively high although unmeasured background of contaminating double positive endothelial cells from arteries and veins unrelated to the 4th or 6th arch arteries that were also present in the isolated tissue fragments, presumably in equal amounts regardless of embryo genotype.