Abstract

Background

Previous reports have shown an antiproliferative effect of the synthetic, 3-thia fatty acid tetradecylthioacetic acid (TTA) on different cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. The mechanisms behind the observed effects are poorly understood. We therefore wanted to explore the molecular mechanisms involved in TTA-induced growth inhibition of the human colon cancer cell line SW620 by gene expression profiling.

Methods

An antiproliferative effect of TTA on SW620 cells in vitro was displayed in real time using the xCELLigence System (Roche). Affymetrix gene expression profiling was performed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms behind the antiproliferative effect of TTA. Changes in gene expression were verified at protein level by western blotting.

Results

TTA reduced SW620 cell growth, measured as baseline cell index, by 35% and 55% after 48 h and 72 h, respectively. We show for the first time that TTA induces an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response in cancer cells. Gene expression analysis revealed changes related to ER stress and unfolded protein response (UPR). This was verified at protein level by phosphorylation of eukaryote translation initiation factor 2 alpha (eIF2α) and downstream up-regulation of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4). Transcripts for positive and negative cell cycle regulators were down- and up-regulated, respectively. This, together with a down-regulation of Cyclin D1 at protein level, indicates inhibition of cell cycle progression. TTA also affected transcripts involved in calcium homeostasis. Moreover, mRNA and protein level of the ER stress inducible C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP), Tribbles homolog 3 (Drosophila) (TRIB3) and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta (C/EBPβ) were enhanced, and the C/EBPβ LIP/LAP ratio was significantly increased. These results indicate prolonged ER stress and a possible link to induction of cell death.

Conclusion

We find that TTA-induced growth inhibition of SW620 cells seems to be mediated through induction of ER stress and activation of the UPR pathway.

Keywords: Cell cycle, Colon cancer, Docosahexaenoic acid, Endoplasmic reticulum stress, Gene expression analysis, Phosphorylated eIF2α, Tetradecylthioacetic acid, Thia fatty acids, Unfolded protein response

Background

Colon cancer is one of the most common incident cancers across Europe [1]. There is an urgent need for finding novel, alternative or supplementary cancer treatments. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are able to inhibit growth of both colon and several other types of cancer cells in vitro and in vivo ([2-5] and reviewed in [6-8]). During the last two decades, chemical modified fatty acid (FA) analogs have been produced in an attempt to achieve FAs having increased metabolic stability and more selective and targeted effects (reviewed in [9]). Among these is the bioactive, saturated 3-thia FA tetradecylthioacetic acid (TTA). TTA has been shown to have both a cardioprotective effect, as well as an antiproliferative effect on cancer cells (reviewed in [10]). TTA has been found to inhibit growth of glioma [11,12], leukemia [13-16] and colon cancer cell lines [11,17] in vitro and in vivo, and hepatoma [18] and breast cancer cells [19] in vitro. TTA seems to be more potent in reducing cell growth compared with the omega-3 (n-3) PUFAs eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) [20]. A diet containing TTA has also resulted in increased vascularisation of colon cancer xenografts in mice [17] and improved the survival of mice having leukemia xenografts [11,14]. TTA food supplementation seems to be generally well tolerated by healthy persons [15,21], and TTA therefore may have a potential in cancer treatment alone or in combination with other therapies.

The structure of TTA is equal to the saturated palmitic acid (PA), except that TTA has a sulphur atom inserted at the third position in the carbon chain [19]. The sulphur atom makes TTA resistant to mitochondrial β-oxidation and probably contributes substantial to its biological effects (reviewed in [10]). TTA is capable of reducing the growth of cancer cells that are not growth inhibited by PA [17,20,22]. TTA is degraded relatively slowly to various dicarboxylic acids via ω-oxidation and sulphur oxidation in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and subsequent β-oxidation in the peroxisomes. Except from blocked mitochondrial β-oxidation, the chemical properties and metabolism of TTA resembles those of normal FAs. TTA is activated by binding to coenzyme A and incorporated into various lipids, especially phospholipids (reviewed in [10,23]).

Before any recommendations regarding use of TTA in cancer treatment can be given, it's important to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the growth inhibitory effect of TTA. In some, but not all, cancer cells, TTA inhibits cancer cell growth via increased lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress [12], or partly via activation of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma [22]. Also, TTA has been shown to induce apoptosis in several glioma [12,13] and leukemia cell lines [13,14]. Induction of apoptosis seems to be related to effects on mitochondria. TTA can induce a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential [13,24] and lead to release of cytochrome C (cyt C) and a reduction in mitochondrial glutathione, the latter indicating a selective modulation of the mitochondrial redox equilibrium [13]. Most of the biological effects of TTA assumed to be implicated in mediating the inhibitory effect of TTA on cancer cells do not seem to be specific for TTA, since they also are assumed to be involved in the growth inhibitory effect of other FAs like n-3 PUFAs [25-27].

We have previously shown that TTA inhibits the growth of SW620 human colon cancer cells in vitro and in vivo [17]. SW620 cell growth is also inhibited by n-3 PUFAs [2,4]. By using gene expression analysis, we found that DHA induces extensive changes in the expression of transcripts involved in biological pathways like ER stress and unfolded protein response (UPR), protein degradation, Ca2+ homeostasis, cell cycle progression and apoptosis [28]. Others have found that PA also can induce ER stress in human [29] and rat cancer cells [30].

The main functions of ER are protein synthesis and folding, lipid synthesis and maintenance of Ca2+ homeostasis. Disruption of these processes causes accumulation of misfolded proteins in ER lumen, leading to ER stress and activation of the cellular stress response UPR. The purpose of UPR is to restore cell homeostasis and promote cell survival, but during prolonged ER stress, apoptosis may be activated. During ER stress, one of the three ER stress sensors; eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha (eIF2α) kinase 3 (EIF2AK3/PERK) is known to phosphorylate eIF2α, thereby attenuating global protein synthesis to reduce the protein load of ER. Reduced synthesis of e.g. cyclin D1 promotes cell cycle arrest, creating time to cope with the stress. However, translation of certain mRNAs is allowed, like mRNAs for activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) and its downstream target C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP) [31,32]. CHOP, which is also regulated by X-box binding protein 1 (XBP-1) (reviewed in [33]), promotes apoptosis by down-regulating anti-apoptotic factors like B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) [34] and up-regulating pro-apoptotic factors like the Bcl-2-interacting protein Bim [35].

During ER stress XBP-1 also activates the transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta (C/EBPβ) [36], which participates in regulation of differentiation, cell growth, cell survival and apoptosis [37,38]. Human C/EBPβ is mainly expressed as two 46 and 42 kDa liver enriched activator protein isoforms (LAP and LAP*) and a 20 kDa liver enriched inhibitor protein isoform (LIP) [39], which are synthesized from different AUG start codons within the C/EBPβ mRNA [40]. Since LIP lacks a transcription activation domain [41] and suppresses the transactivation by LAP, the LIP/LAP ratio influences on the extent of C/EBPβ-activated transcription [40].

LIP has been shown to decrease during early ER stress, and increase during prolonged ER stress, causing an increase in the LIP/LAP ratio [42]. Increased LIP seems to be essential for CHOP-induced apoptosis, since heterodimerization of LIP with CHOP promotes nuclear translocation of CHOP and pro-apoptotic gene regulation by CHOP [43]. In addition, CHOP-C/EBPβ [44] and CHOP-ATF4 [45] heterodimeres up-regulate the pro-apoptotic pseudo-kinase Tribbles homolog 3 (Drosophila) (TRIB3), which can promote apoptosis by inhibiting the anti-apoptotic kinase Akt [46] and the transcription factor nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) [47]. CHOP- and TRIB3-promoted cell death might be accompanied by the ER stress-induced caspase 4 (CASP4) and calpains [32,48,49].

In this report we have used Affymetrix gene expression analysis to search for possible molecular mechanisms underlying the growth inhibitory effect of TTA on SW620 cells in vitro. The results indicate that TTA reduces SW620 cell growth through activation of ER stress and UPR, by a similar mechanism as observed after treatment with DHA [28].

Results

TTA reduces growth of SW620 cells

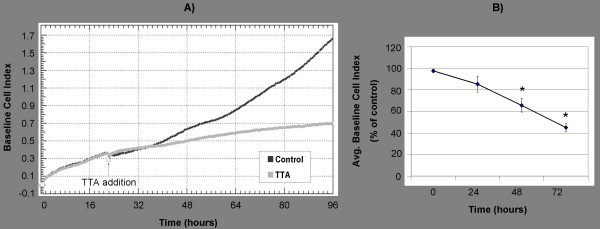

In accordance with previous results [17], we verified a growth inhibitory effect of TTA (75 μM) on SW620 colon cancer cells by cell counting (data not shown) and by measuring the growth real time by using the xCELLigence System (Roche) (Figure 1A). The SW620 growth curve, which is presented as baseline cell index, showed that TTA (75 μM) significantly reduced the baseline cell index by 35% and 55% after 48 h and 72 h, respectively, compared to the control (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Real time monitoring of TTA-induced growth inhibition of SW620 cells. SW620 colon cancer cells were seeded in 16 well E-plates. After ~24 h, TTA (75 μM) or NaOH (control) were added. Cell growth was monitored using the xCELLigence RTCA DP Instrument (Roche). (A) SW620 cell growth presented as baseline cell index from one representative experiment. (B) Average baseline cell index (± SD) of TTA-treated cells, presented as percent of control, at indicated time points. Mean was calculated from at least two duplicate measurements in four independent experiments. * Significantly different from control (one-tailed Student's t-test, P < 0.05).

TTA induces extensive changes at mRNA level indicating ER stress and UPR

In an attempt to unravel the mechanisms underlying the growth-inhibiting effect of TTA, SW620 cells were cultivated in the absence or presence of 75 μM TTA for 24 h, followed by gene expression profiling. Differentially expressed transcripts are presented and listed by full and short names in Table 1 and Additional file 1.

Table 1.

Gene expression results

| Gene Symbol | Affymetrix ID | Refseq NCBI ID | Transcript name | SW620 Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | ||||

| ER stress and unfolded protein response | ||||

| ATF3 | 202672_s_at |

NM_001030287 NM_001040619 NM_001674 NM_004024 |

Activating transcription factor 3 | 3.5 |

| ATF4 | 200779_at |

NM_001675 NM_182810 |

Activating transcription factor 4 | 1.7 |

| ATF6 | 217550_at 231927_at 203952_at |

NM_007348 | Activating transcription factor 6 | 1.5 1.3 1.2 |

| CEBPB | 212501_at | NM_005194 | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), beta | 3.2 |

| CHOP/DDIT3 | 209383_at |

NM_001130101 NM_001130102 NM_004083 NM_005693 |

DNA-damage-inducible transcript 3 | 2.7 |

| GADD34 | 37028_at 202014_at |

NM_014330 | Growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible 34 | 2.0 2.0 |

| IRE1/ERN1 | 235745_at | NM_001433 | Inositol-requiring enzyme 1/Endoplasmic reticulum to nucleus signaling 1 | 1.7 |

| NRF2/NFE2L2 | 201146_at |

NM_001145412 NM_001145413 NM_006164 |

Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 | 1.3 |

| TRIB3 | 1555788_a_at 218145_at |

NM_021158 | Tribbles homolog 3 (Drosophila) | 5.1 4.9 |

| XBP1 | 242021_at 200670_at |

NM_001079539 NM_005080 |

X-box binding protein 1 | 1.2 1.6 |

| Chaperones/Protein folding/Unfolded protein response/Protein degradation/Amino acid synthesis | ||||

| ASNS | 205047_s_at |

NM_001673 NM_133436 NM_183356 |

Asparagine synthetase | 4.8 |

| CREB3L2 | 212345_s_at | NM_194071 | cAMP responsive element binding protein 3-like 2 | 1.4 |

| CREB3L3 | 234361_at | NM_032607 | cAMP responsive element binding protein 3-like 3 | 3.0 |

| DNAJB2 | 202500_at |

NM_001039550 NM_006736 |

DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily B, member B2 | 1.3 |

| DNAJB14 | 222850_s_at | NM_001031723 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily B, member B14 | 1.2 |

| DNAJC24 | 242562_at | NM_181706 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily C, member 24 | 1.4 |

| EDEM1 | 203279_at | NM_014674 | ER degradation enhancer, mannosidase alpha-like 1 | 1.3 |

| EDEM3 | 220342_x_at | NM_025191 | ER degradation enhancer, mannosidase alpha-like 3 | 1.2 |

| ERO1LB | 231944_at | NM_019891 | ERO1-like beta (S. cerevisiae) | 1.3 |

| HMOX1/HSP32 | 203665_at | NM_002133 | Heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 | 1.6 |

| HSPA13 | 202557_at 202558_s_at |

NM_006948 | Heat shock 70kDa protein 13 | 1.4 1.7 |

| PDIA2 | 206691_s_at | NM_006849 | Protein disulfide isomerase family A, member 2 | 1.2 |

| PFDN2 | 218336_at | NM_012394 | Prefoldin 2 | 1.4 |

| PSMB1 | 214289_at | NM_002793 | Proteasome subunit, beta type, 1 | 1.3 |

| SQSTM1 | 201471_s_at 213112_s_at 239004_at 244804_at |

NM_001142298 NM_001142299 NM_003900 |

Sequestosome 1 | 2.1 3.1 1.3 2.1 |

| UBE2B | 239163_at | NM_003337 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2B (RAD6 homolog) | 1.5 |

| SEC61A2 | 219499_at 228747_at |

NM_001142627 NM_001142628 NM_018144 |

Sec61 alpha 2 subunit (S. cerevisiae) | 1.3 1.2 |

| SEC61B | 244700_at | NM_006808 | Sec61 beta subunit | 1.6 |

| SEC63 | 201914_s_at 201915_s_at 201916_s_at |

NM_007214 | SEC63 homolog (S. cerevisiae) | 1.3 1.2 1.3 |

| Ca2+ homeostasis, signaling and transport | ||||

| ATP2B4/PMCA4 | 205410_s_at 212135_s_at 212136_at |

NM_001001396 NM_001684 |

ATPase, Ca2+ transporting, plasma membrane 4 | 1.5 2.7 5.4 |

| CAPN1 | 232012_at | NM_005186 | Calpain 1, (mu/I) large subunit | 1.4 |

| CAPN2 | 208683_at 214888_at |

NM_001146068 NM_001748 |

Calpain 2, large subunit | 1.4 1.8 |

| CAPN5 | 205166_at | NM_004055 | Calpain 5 | 1.4 |

| HERPUD1 | 217168_s_at |

NM_001010989 NM_001010990 NM_014685 |

Homocysteine-inducible, endoplasmic reticulum stress-inducible, ubiquitin-like domain member 1 | 1.9 |

| ITPR1 | 244090_at | --- | Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor, type 1 | 1.3 |

| ITPR3 | 201187_s_at 201188_s_at 201189_s_at |

NM_002224 | Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor, type 3 | 1.3 1.5 1.5 |

| PLCD3 | 234971_x_at 1552476_s_at |

NM_133373 | Phospholipase C, delta 3 | 1.3 1.3 |

| S100A10 | 200872_at 238909_at |

NM_002966 | S100 calcium binding protein A10 | 1.2 2.4 |

| S100P | 204351_at | NM_005980 | S100 calcium binding protein P | 4.9 |

| STC2 | 203438_at 203439_s_at |

NM_003714 | Stanniocalcin 2 | 2.1 2.7 |

| Cell cycle/Apoptosis | ||||

| ATF5 | 204998_s_at 204999_s_at |

NM_012068 | Activating transcription factor 5 | 1.5 1.7 |

| AURKA | 208080_at |

NM_003600 NM_198433 NM_198434 NM_198435 NM_198436 NM_198437 |

Aurora kinase A | -1.3 |

| BIRC5 | 202094_at 202095_s_at 210334_x_at |

NM_001012270 NM_001012271 NM_001168 |

Baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 5/Survivin | -1.7 -1.3 -1.3 |

| CASP4 | 213596_at |

NM_001225 NM_033306 |

Caspase 4 | 1.4 |

| CCNA2 | 203418_at 213226_at |

NM_001237 | Cyclin A2 | -1.2 -1.2 |

| CCND3 | 201700_at |

NM_001136017 NM_001136125 NM_001136126 NM_001760 |

Cyclin D3 | -2.0 |

| CCNE1 | 213523_at |

NM_001238 NM_057182 |

Cyclin E1 | -1.3 |

| CCNE2 | 205034_at 211814_s_at |

NM_057749 | Cyclin E2 | -2.9 -3.1 |

| CCNF | 204827_s_at | NM_001761 | Cyclin F | -1.2 |

| CDC2/CDK1 | 203214_x_at |

NM_001130829 NM_001786 NM_033379 |

Cell division cycle 2, G1 to S and G2 to M | -1.2 |

| CDK2 | 204252_at 211804_s_at |

NM_001798 NM_052827 |

Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 | -1.3 -1.4 |

| CDK4 | 202246_s_at | NM_000075 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 | -1.4 |

| CDK5 | 204247_s_at |

NM_001164410 NM_004935 |

Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 | -1.5 |

| CDK6 | 224847_at 224848_at 224851_at 243000_at |

NM_001145306 NM_001259 |

Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 | -1.4 -1.5 -1.3 -1.3 |

| CDKN2A | 211156_at |

NM_000077 NM_058195 NM_058197 |

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (melanoma, p16, inhibits CDK4) | 1.3 |

| CDKN2B | 207530_s_at 236313_at |

NM_004936 NM_078487 |

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2B (p15, inhibits CDK4) | 1.5 2.0 |

| CDKN2D | 210240_s_at |

NM_001800 NM_079421 |

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2D (p19, inhibits CDK4) | 1.2 |

| CUL1 | 238509_at | NM_003592 | Cullin 1 | 1.4 |

| KLF4 | 220266_s_at 221841_s_at |

NM_004235 | Kruppel-like factor 4 (gut) | 1.9 2.4 |

| PDCD4 | 202731_at 212593_s_at |

NM_014456 NM_145341 |

Programmed cell death 4 (neoplastic transformation inhibitor) | 1.3 1.3 |

| PDCD6 | 222152_at 222380_s_at |

NM_013232 | Programmed cell death 6 | 1.3 1.3 |

| SFN | 33322_i_at 33323_r_at 209260_at |

NM_006142 | Stratifin | 1.6 1.7 1.6 |

Significantly differentially expressed transcripts in SW620 treated with TTA (75 μM) for 24 h as determined by Affymetrix microarray analysis (P < 0.05).

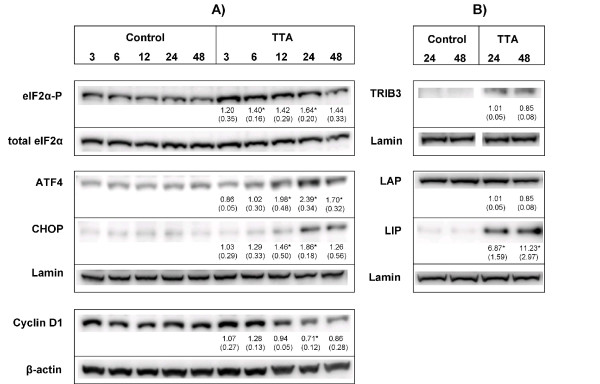

After incubation with TTA, the transcription level of several genes involved in ER stress and UPR were affected. The ER stress sensors inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1) and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), and downstream targets of these, like XBP-1, were up-regulated (Table 1). However, most changes in the ER stress signaling pathway were found downstream of PERK. Phosphorylation of eIF2α by PERK is a hallmark of ER stress (reviewed in [31]). After TTA treatment, phosphorylated eIF2α (eIF2α-P) was found significantly increased after 6 h and 24 h (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

TTA induces proteins involved in ER stress and UPR. SW620 cells were treated with TTA (75 μM) or NaOH (control) for indicated time periods, and proteins were quantified by western blotting. (A) Analysis of eIF2α-P and Cyclin D1 from cytosolic protein extracts and ATF4 and CHOP from nuclear protein extracts. (B) Analysis of TRIB3 and the C/EBPβ protein isoforms LAP (45 kDa) and LIP (20 kDa) from nuclear protein extracts. Blots were quantified, and band intensities normalized relative to the respective loading control; β-actin (Cyclin D1), Lamin (nuclear extracts) or total level of eIF2α (eIF2α-P), to adjust for unequal protein loading within the membranes. Band intensities were related to the 24 h control band to adjust for differences in signal intensities between the membranes, except for TRIB3 where the band intensities are related to the 24 h TTA band (not expressed in control). Quantified results show mean fold change (± SD) of TTA-samples relative to control at indicated time periods for three independent experiments. One representative blot is shown. * Significantly different from control (one-tailed Student's t-test, P < 0.05).

Phosphorylation of eIF2α induces transcription of ATF4 and its downstream targets, like ATF3, CHOP, growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible 34 (GADD34), TRIB3 [50,51] and heme oxygenase 1 (HMOX1) [52]. All these transcripts were up-regulated upon TTA treatment (Table 1). Moreover, the protein levels of ATF4, CHOP (Figure 2A) and TRIB3 (Figure 2B) were also increased. ATF4 is known to induce genes involved in amino acid synthesis, and several transcripts involved in amino acid synthesis and transport were also up-regulated (Table 1 and Additional file 1).

When UPR is activated, cells try to up-regulate the folding capacity e.g. through up-regulation of chaperones and heat shock proteins (Hsps) [31]. Transcripts of the folding machinery were found to be up-regulated in the SW620 cells after incubation with TTA. These include prefoldin 2 (PFDN2), DnaJ (HSP40) homolog, subfamily B, member 2 (DNAJB2), DNAJB14, DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily C, member 24 (DNAJC24), heat shock protein 13 (HSPA13), HSP32 (HMOX1) and hypoxia up-regulated 1 (HYOU1) (Table 1 and Additional file 1). Protein disulfide isomerase family A, member 2 (PDIA2) and ERO1-like beta (ERO1LB), which are known to catalyze protein folding [31,53], were also up-regulated (Table 1). However, some DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog subfamily members and Hsps were also found to be down-regulated (Additional file 1).

During ER stress, improperly folded proteins are transferred to ER degradation enhancer, mannosidase alpha-like protein (EDEM) and translocated to cytosol for proteasomal degradation; a process called ER associated degradation (ERAD) [31]. EDEM1 and EDEM3, in addition to several proteasomal subunits and ubiquitin-related transcripts, were up-regulated upon TTA treatment. Also, proteasome subunit, beta type, 1 (PSMB1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2B (RAD6 homolog) (UBE2B) and cullin1 (CUL1) were up-regulated (Table 1 and Additional file 1). In addition, TTA also up-regulated sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1), which is able to sequester and shuttle polyubiquitinated, misfolded proteins to the proteasome (reviewed in [54]) (Table 1). Moreover, TTA up-regulated transcripts for parts of the ER translocation machinery which transports proteins to the cytosol, like Sec61 alpha 2 subunit (SEC61A2), Sec61 beta subunit (SEC61B) and SEC63 homolog (SEC63) (Table 1).

TTA affects Ca2+ homeostasis

Another indication of an ER stress condition in SW620 cells treated with TTA is the altered expression of transcripts coding for proteins involved in Ca2+ homeostasis. The more than 5-fold up-regulation of ATPase, Ca2+-transporting, plasma membrane 4 (ATP2B4/PMCA4) might indicate the presence of a high Ca2+ concentration in the cytosol (Table 1). A possible high Ca2+ level in the cytosol may be part of the ER stress response, with Ca2+ leaking from ER through the up-regulated IP3 receptors, type 1 and 3 (ITPR1 and 3, Table 1). We also found Phospholipase C D3 (PLCD3), which is known to participate in the generation of IP3 [55], to be up-regulated at mRNA level after TTA-treatment (Table 1).

Among other important Ca2+-related transcripts, we found several S100 Ca2+ binding proteins to be differentially expressed after TTA-treatment, e.g. S100P and S100A10 were up-regulated (Table 1 and Additional file 1). Also, TTA caused up-regulation of Stanniocalcin 2 (STC2), which is induced downstream of PERK and critical for survival after UPR [56]. TTA further up-regulated homocysteine-inducible endoplasmic reticulum stress-inducible ubiquitin-like domain member 1 (HERPUD1) (Table 1), which is known to counteract Ca2+ disturbances during ER stress [57].

Effect of TTA on cell cycle

TTA affected the mRNA level of several cell cycle transcripts, most of them having rather small fold change values. Positive cell cycle regulators were down-regulated and negative regulators were up-regulated, as outlined below.

The cell cycle is known to be positively regulated by cyclins (CCNs) and cyclin dependent kinases (CDKs). The mRNA level of cyclin D3 (CCND3), but not cyclin D1, was down-regulated upon TTA treatment (Table 1). However, the protein level of cyclin D1 was significantly decreased after incubation with TTA (Figure 2A). Moreover, transcripts for CCNA2, CCNE1, CCNE2, CCNF, CDK1/CDC2, CDK2, CDK4, CDK5 and CDK6 were down-regulated (Table 1), indicating inhibition of cell cycle progression. The CDK4 inhibitors CDK inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A), CDKN2B and CKDN2D, which are negative regulators of cell cycle, were increased (Table 1). In addition, the tumor suppressor programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4), which is able to reduce the protein level of CDK4 [58], and PDCD6 were up-regulated (Table 1).

Other important cell cycle related transcripts that were up-regulated by TTA were ATF5, stratifin (SFN/14-3-3 sigma) and kruppel like factor 4 (KLF4) (Table 1). TTA also induced down-regulation of aurora kinase A (AURKA) and survivin/baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 5 (BIRC5) (Table 1).

TTA changes expression of transcripts involved in ER stress-related apoptosis

Transcripts related to ER stress-induced apoptosis were also up-regulated upon TTA treatment. In addition to the up-regulation of CHOP and TRIB3, TTA also increased transcription of CASP4, calpain 1, large subunit (CAPN1), CAPN2 and CAPN5 (Table 1).

The C/EBPβ LIP isoform is known to augment ER stress-induced cell death by interfering with the expression of TRIB3 [59]. C/EBPβ (CEBPB) was up-regulated 3.2-fold at mRNA level (Table 1) after TTA treatment. Western blotting mainly displayed two C/EBPβ isoforms; a highly expressed 45 kDa LAP isoform and a lower expressed 20 kDa LIP isoform. The 42 kDa LAP* isoform was only found in very low amounts (Figure 2B). TTA did not affect the level of LAP, but induced a significant 6.9- and 11.2-fold induction of LIP after 24 and 48 h, respectively (Figure 2B). The accumulation of LIP at these time points caused a significant 6.6- and 13.3-fold increase in the LIP/LAP ratio after 24 h and 48 h, respectively, compared to control cells.

During ER stress, cAMP responsive element binding protein 3-like 2 and 3 (CREB3L2 and CREB3L3) are induced in order to attenuate ER stress-induced cell death [60]. These transcripts were also up-regulated (Additional file 1).

Discussion

Several studies have shown that TTA inhibits the growth of various cancer cells in vitro and in vivo [13,20,22]. We have previously shown that TTA inhibits DNA synthesis in SW620 human colon cancer cells in a time- and dose-dependent manner [17], and the growth inhibitory effect of TTA on this cell line was confirmed in the current study by xCELLigence proliferation assay. This assay monitors cell growth real time by measuring changes in electric impedance between two golden electrodes embedded in the bottom of the cell culture wells. The impedance, which is converted to a cell index value, is directly proportional to the number of cells and also reflects the cells' viability, morphology and adhesion strength [61]. The baseline cell index declined compared to the control from approximately 20 hours after TTA-supplementation. Previous studies have indicated that TTA affects multiple biochemical pathways that might play a role in its growth-limiting effect on different cancer cells. However, the exact mechanisms are not yet clear.

This is the first study demonstrating that TTA is able to induce ER stress in cancer cells. Transcripts involved in ER stress and downstream of all three ER stress sensors, like ATF6, IRE1, XBP-1 and ATF4, were found to be differentially expressed after treating SW620 cells with TTA. Also, the increased expression of Hsps and DNAJs indicates that the cells try to increase their protein folding capacity. The up-regulation of EDEM1 and EDEM3, SQSTM1, proteasomal subunits and ubiquitin-related transcripts indicates activation of ERAD.

The PERK branch of UPR was found to be activated, supported by the increased protein level of eIF2α-P and ATF4, as well as up-regulation of several downstream targets of ATF4, like ATF3, ASNS, CHOP and TRIB3, at mRNA level. CHOP and TRIB3, also induced at protein level, are known to link ER stress to ER stress-induced cell death (reviewed in [32]). The enhanced level of these proteins and transcripts for CASP4 and calpains indicates that TTA causes prolonged ER stress and direct the cell fate towards induction of death. We have previously shown that DHA induces ER stress with increased eIF2α-P, ATF4 and CHOP in the same cell line [28,62]. We also found HL-60 leukemia cells to induce ER stress upon EPA treatment [63].

In SW620 cells, TTA up-regulated the C/EBPβ LIP isomer, while LAP was unchanged. LIP is capable of modulating the ER stress response by augmenting cell death, e.g. by enhancing the activity of CHOP [43]. On the contrary, LAP may attenuate ER stress and ER stress induced cell death by inhibiting CHOP [59,64]. However, Li et al. found that LAP modulated the ER stress response by enhancing the expression of pro-apoptotic genes. They also proposed that the ER stress response may be modulated by regulation of the LIP/LAP ratio [42]. We found this ratio to be increased after 24 and 48 h of TTA treatment, supporting the assumption that TTA causes prolonged ER stress and a switch towards induction of cell death. Even if C/EBPβ mRNA was up-regulated, we only found an increase of LIP at protein level. Different regulation of LIP and LAP might be explained by different synthesis and degradation rates of these isomers [42].

Our results also indicate that TTA affects several transcripts involved in cell cycle progression. Transcripts involved in regulation of both the G1/S and G2/M phases were differentially expressed. In general, positive cell cycle regulators (like CDKs, cyclins, AURKA and survivin) were down-regulated, and negative cell cycle regulators (like ATF5, SFN and KLF4) were up-regulated, which indicates a stop in the cell cycle progression. We have previously demonstrated that DHA treatment of the SW620 cells affects several cell cycle transcripts and proteins like CDKs, cyclins and survivin etc. [62] and arrests the cells in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle [2]. Brewer et. al. stated that cell cycle arrest might be induced during ER stress to prevent cells from completing cell division when the conditions are compromising proper folding and assembly of proteins [65].

TTA also seems to induce changes in expression of transcripts involved in maintenance of Ca2+ homeostasis. The ER lumen contains a high Ca2+ concentration, and induction of ER stress may either come from and/or culminate with a release of Ca2+ from the ER (reviewed in [66,67]). ER stress-accompanied changes in the Ca2+ metabolism may lead to a pro-apoptotic signal via the mitochondria [66]. We have previously shown that DHA and EPA affect Ca2+ homeostasis in cancer cells [28,63]. Apoptosis has been observed in other cancer cells treated with TTA [13,22], and it has been proposed that this effect is mediated via mitochondrial alterations, such as decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential and release of Cyt C [13]. CHOP and C/EBPβ may be involved in the regulation of mitochondrial stress genes like TRIB3 [44] in response to accumulation of unfolded proteins in mitochondria [68]. Their up-regulation by TTA may indicate that the SW620 cells are undergoing a mitochondrial stress after TTA treatment.

Madsen et al. found TTA to be incorporated mainly into phospholipids in liver after TTA supplementation to rats [69]. The inner mitochondrial membrane phospholipid cardiolipin (CL) is essential for the function of several mitochondrial protein complexes. It interacts with mitochondrial Cyt C, which might utilize reactive oxygen species and cause oxidation of CL. Oxidized CL is required for release of pro-apoptotic factors like Cyt C to cytosol [70]. Enrichment of EPA and DHA in CL isolated from colonic mucosa in rats fed fish oil or EPA/DHA ethyl esters might result in high susceptibility to lipid peroxidation due to the FAs' high degree of unsaturation. This may trigger release of pro-apoptotic factors from mitochondria (reviewed in [71]). Decreased synthesis of CL has also been related to Cyt C release from mitochondria during PA-induced apoptosis (reviewed in [9]). It remains to be investigated if this is the case with TTA.

Conclusions

TTA induces extensive changes in the expression of genes involved in several biological pathways. TTA causes accumulation of misfolded proteins in ER, causing ER stress and activation of UPR. The results show that TTA inhibits SW620 cell growth, at least partly, via the same mechanisms as DHA. Thus, cancer cells seem to cope with stress induced by various FAs through the same mechanisms.

Methods

Materials and cell culture

TTA was prepared at the Department of Chemistry, University of Bergen, Norway, as described previously [72] and in Supplementary experimental procedures (Additional file 2). All other solvents were of reagent grade from commercial sources. Antibody specifications are found in Additional file 2. The human colon carcinoma cell line SW620 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD) and cultivated in Leibovitz's L-15 medium (Cambrex, BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with L-glutamine (2 mM), FBS (10%) and gentamicin (45 mg/l) (complete growth medium), in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2: 95% air at 37°C.

Cell proliferation assay by xCELLigence

SW620 cells were seeded in 16 well plates (E-plate 16, Roche, Mannheim, Germany) (12.000 cells in 150 μl medium/well), following the xCELLigence Real Time Cell Analyzer (RTCA) DP instrument manual as provided by the manufacturer (Roche). After ~24 h, TTA (75 μM, prepared as described in Additional file 2) or the vehicle NaOH (control medium) was added, and the experiment was allowed to run for 72 h. Average baseline cell index and percent reduction of baseline cell index for TTA-treated cells compared to control cells were calculated for at least two measurements from 4 replicate experiments ± SD. Significance was calculated using one-tailed Student's t-test (P < 0.05).

RNA isolation, gene expression profiling and statistical analysis

SW620 cells were seeded in 175 cm2 flasks (3.5 × 106 cells in 28 ml medium). After 24 h incubation, cells were treated with TTA (75 μM) or NaOH (control) for 24 h. Cell harvesting and total RNA isolation was performed as elaborated in [28], using the High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche). Gene expression profiling was performed following the Eukaryote expression manual from Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA), using the Human Genome U133 2.0 Plus Array (Affymetrix), as described in Additional file 2. Statistical analysis of gene expression results was performed using the RMA method. Differentially expressed genes were identified using a linear model with a modified T-statistic [73], and results were corrected for multiple testing using the method described in [74] with a false discovery rate of 0.05. Annotations of probe sets and biological information of genes were retrieved from the web-based NetAffx Analysis Center at affymetrix.com and eGOn at genetools.no. Signal values presented are mean values of 3 replicate experiments. All experiments have been submitted to Array-Express with accession number E-MEXP-2590.

Western blot analysis

Cells were treated with TTA (75 μM) or NaOH for 3, 6, 12, 24 and/or 48 h, as described in the gene expression profiling method. For detection of eIF2α-P and cyclin D1, cells were harvested as elaborated in [28], and cytosolic protein extracts were prepared immediately in lysis buffer as described in [63]. Nuclear protein extracts for detection of ATF4, CHOP, TRIB3 and C/EBPβ were obtained by using Nuclear Extract Kit (Active Motif, Rixensart, Belgium) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Protein concentrations were measured using Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and the protein extracts were snap-freezed in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until further use. Cytosolic and nuclear proteins (80 or 50 μg per well, respectively) were separated on 10% precast denaturing NuPAGE® gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, US) and transferred onto Immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Membranes were blocked in phosphate buffered saline buffer with 0.1% (v/v) Tween® 20 (BioRad, Hercules, CA) and 5% blocker non-fat dry milk, before incubated with primary and secondary horse radish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) dissolved in this blocking buffer as described in Additional file 2. eIF2α-P incubations were performed using tris-buffered saline Tween 20 buffer as described in [63]. Blots were detected by chemiluminescense using SuperSignal® West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and visualized by Kodak Image Station 4000R (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, NY). Western blot band intensities were quantified using Kodak Molecular Imaging Software (version 4.0.1). Quantified western blot results, based on 3 independent replicates, were analysed as described in the proliferation assay method.

List of abbreviations

Transcript short names are to be found in Table 1 and Additional file 1.

Cyt C: Cytochrome C; DHA: Docosahexaenoic acid; eIF2α: Eukaryote translation initiation factor 2 alpha; EIF2AK3/PERK: eIF2α kinase 3; eIF2α-P: phoshorylated eIF2α; EPA: Eicosapentaenoic acid; ER: Endoplasmic reticulum; ERAD: ER-associated degradation; FAs: Fatty acids; Hsps: Heat shock proteins; LAP: Liver enriched activator protein; LIP: Liver enriched inhibitor protein; n-3: Omega-3; PA: Palmitic acid; PUFAs: Polyunsaturated fatty acids; TTA: Tetradecylthioacetic acid; UPR: Unfolded protein response

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Rolf K Berge and Kjetil Berge have stocks in Thia Medica AS. There is no conflict of interest.

Authors' contributions

AGL carried out cell experiments, xCELLigence experiments, western blots and helped to draft the manuscript. CHHP carried out cell experiments, gene expression experiments and drafted the manuscript. KB participated in study design, carried out initial experiments and helped to draft the manuscript. RKB participated in study design. SAS participated in study design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary gene expression results. Functional categories of significantly differentially expressed transcripts affected in SW620 cells treated with TTA (75 μM) for 24 h, as determined by Affymetrix microarray analysis (P < 0.05).

Supplementary experimental procedures. The file contains supplementing information about the experimental procedures including preparation of TTA stock solution and medium, gene expression experiments and antibodies used.

Contributor Information

Anne G Lundemo, Email: anne.g.lundemo@ntnu.no.

Caroline HH Pettersen, Email: caroline.h.pettersen@ntnu.no.

Kjetil Berge, Email: kjetil.berge@akerbiomarine.com.

Rolf K Berge, Email: rolf.berge@med.uib.no.

Svanhild A Schønberg, Email: svanhild.schonberg@ntnu.no.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Endre Anderssen, Norwegian Microarray Consortium (NMC), Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim, Norway for microarray statistical analysis. The work was supported by The Faculty of Medicine, NTNU, The Cancer Research Fund, The Research Council of Norway through grants from the Functional Genomics Program (FUGE) and grants from Helse Vest, Norway. Microarray experiments were performed at the microarray core facility at the Norwegian Microarray Consortium (NMC), Trondheim, which is supported by the FUGE, The Norwegian Research Council.

Mailing address for reprints:

Svanhild A. Schonberg, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Children's and Women's Health, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, N-7006, Trondheim, Norway.

References

- Ferlay J, Autier P, Boniol M, Heanue M, Colombet M, Boyle P. Estimates of the cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2006. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(3):581–592. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonberg SA, Lundemo AG, Fladvad T, Holmgren K, Bremseth H, Nilsen A, Gederaas O, Tvedt KE, Egeberg KW, Krokan HE. Closely related colon cancer cell lines display different sensitivity to polyunsaturated fatty acids, accumulate different lipid classes and downregulate sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1. FEBS J. 2006;273(12):2749–2765. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finstad HS, Myhrstad MC, Heimli H, Lomo J, Blomhoff HK, Kolset SO, Drevon CA. Multiplication and death-type of leukemia cell lines exposed to very long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. Leukemia. 1998;12(6):921–929. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bathen TF, Holmgren K, Lundemo AG, Hjelstuen MH, Krokan HE, Gribbestad IS, Schonberg SA. Omega-3 fatty acids suppress growth of SW620 human colon cancer xenografts in nude mice. Anticancer Res. 2008;28(6A):3717–3723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonberg SA, Rudra PK, Noding R, Skorpen F, Bjerve KS, Krokan HE. Evidence that changes in Se-glutathione peroxidase levels affect the sensitivity of human tumour cell lines to n-3 fatty acids. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18(10):1897–1904. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.10.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roynette CE, Calder PC, Dupertuis YM, Pichard C. n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and colon cancer prevention. Clin Nutr. 2004;23(2):139–151. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockbain AJ, Toogood GJ, Hull MA. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids for the treatment and prevention of colorectal cancer. Gut. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rose DP, Connolly JM. Omega-3 fatty acids as cancer chemopreventive agents. Pharmacol Ther. 1999;83(3):217–244. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7258(99)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronstad KJ, Berge K, Berge RK, Bruserud O. Modified fatty acids and their possible therapeutic targets in malignant diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2003;7(5):663–677. doi: 10.1517/14728222.7.5.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge RK, Skorve J, Tronstad KJ, Berge K, Gudbrandsen OA, Grav H. Metabolic effects of thia fatty acids. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13(3):295–304. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200206000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge K, Tronstad KJ, Abdi-Dezfuli F, Ranheim T, Mahesparan R, Bjerkvig R, Berge RK. Poorly oxidizable fatty acid analogues inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells in culture. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;466:205–210. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46818-2_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronstad KJ, Berge K, Dyroy E, Madsen L, Berge RK. Growth reduction in glioma cells after treatment with tetradecylthioacetic acid: changes in fatty acid metabolism and oxidative status. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;61(6):639–649. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(01)00525-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronstad KJ, Gjertsen BT, Krakstad C, Berge K, Brustugun OT, Doskeland SO, Berge RK. Mitochondrial-targeted fatty acid analog induces apoptosis with selective loss of mitochondrial glutathione in promyelocytic leukemia cells. Chem Biol. 2003;10(7):609–618. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(03)00142-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen PO, Sorensen DR, Tronstad KJ, Gudbrandsen OA, Rustan AC, Berge RK, Drevon CA. A bioactively modified fatty acid improves survival and impairs metastasis in preclinical models of acute leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(11 Pt 1):3525–3531. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronstad KJ, Bruserud O, Berge K, Berge RK. Antiproliferative effects of a non-beta-oxidizable fatty acid, tetradecylthioacetic acid, in native human acute myelogenous leukemia blast cultures. Leukemia. 2002;16(11):2292–2301. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikstein BS, McCormack E, Tronstad KJ, Schwede F, Berge R, Gjertsen BT. Protein kinase A activators and the pan-PPAR agonist tetradecylthioacetic acid elicit synergistic anti-leukaemic effects in AML through CREB. Leuk Res. 2010;34(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen LR, Berge K, Bathen TF, Wergedahl H, Schonberg SA, Bofin A, Berge RK, Gribbestad IS. Effect of dietary tetradecylthioacetic acid on colon cancer growth studied by dynamic contrast enhanced MRI. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6(11):1810–1816. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.11.4887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen HN, Norrheim L, Spydevold O, Gautvik KM. Uptake and receptor binding of dexamethasone in cultured 7800 C1 hepatoma cells in relation to regulation of cell growth and peroxisomal beta-oxidation. Int J Biochem. 1990;22(10):1171–1177. doi: 10.1016/0020-711X(90)90117-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdi-Dezfuli F, Berge RK, Rasmussen M, Thorsen T, Aakvaag A. Effects of saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids and their 3-thia fatty acid analogues on MCF-7 breast cancer cell growth. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;744:306–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb52748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdi-Dezfuli F, Froyland L, Thorsen T, Aakvaag A, Berge RK. Eicosapentaenoic acid and sulphur substituted fatty acid analogues inhibit the proliferation of human breast cancer cells in culture. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1997;45(3):229–239. doi: 10.1023/A:1005818917479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen RJ, Salem M, Skorve J, Ulvik RJ, Berge RK, Nordrehaug JE. Pharmacology and safety of tetradecylthioacetic acid (TTA): phase-1 study. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2008;51(4):410–417. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181673be0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge K, Tronstad KJ, Flindt EN, Rasmussen TH, Madsen L, Kristiansen K, Berge RK. Tetradecylthioacetic acid inhibits growth of rat glioma cells ex vivo and in vivo via PPAR-dependent and PPAR-independent pathways. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22(11):1747–1755. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.11.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrede S, Sorensen HN, Larsen LN, Steineger HH, Hovik K, Spydevold OS, Horn R, Bremer J. Thia fatty acids, metabolism and metabolic effects. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1344(2):115–131. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(96)00138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge K, Tronstad KJ, Bohov P, Madsen L, Berge RK. Impact of mitochondrial beta-oxidation in fatty acid-mediated inhibition of glioma cell proliferation. J Lipid Res. 2003;44(1):118–127. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200312-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noding R, Schonberg SA, Krokan HE, Bjerve KS. Effects of polyunsaturated fatty acids and their n-6 hydroperoxides on growth of five malignant cell lines and the significance of culture media. Lipids. 1998;33(3):285–293. doi: 10.1007/s11745-998-0207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calviello G, Serini S, Piccioni E, Pessina G. Antineoplastic effects of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in combination with drugs and radiotherapy: preventive and therapeutic strategies. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61(3):287–301. doi: 10.1080/01635580802582777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards IJ, O'Flaherty JT. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and PPARγ in Cancer. PPAR Research. 2008;2008:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2008/358052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen CH, Storvold GL, Bremseth H, Follestad T, Sand K, Mack M, Olsen KS, Lundemo AG, Iversen JG, Krokan HE. et al. DHA induces ER stress and growth arrest in human colon cancer cells: associations with cholesterol and calcium homeostasis. J Lipid Res. 2008;49(10):2089–2100. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700389-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Li K, Laybutt DR, He ML, Zhao HL, Chan JC, Xu G. Bip overexpression, but not CHOP inhibition, attenuates fatty-acid-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in HepG2 liver cells. Life Sci. 2010;87(23-26):724–732. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Wang D, Pagliassotti MJ. Saturated fatty acid-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis are augmented by trans-10, cis-12-conjugated linoleic acid in liver cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;303(1-2):105–113. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9461-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder M, Kaufman RJ. ER stress and the unfolded protein response. Mutat Res. 2005;569(1-2):29–63. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szegezdi E, Logue SE, Gorman AM, Samali A. Mediators of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2006;7(9):880–885. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyadomari S, Mori M. Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11(4):381–389. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough KD, Martindale JL, Klotz LO, Aw TY, Holbrook NJ. Gadd153 sensitizes cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress by down-regulating Bcl2 and perturbing the cellular redox state. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(4):1249–1259. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1249-1259.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthalakath H, O'Reilly LA, Gunn P, Lee L, Kelly PN, Huntington ND, Hughes PD, Michalak EM, McKimm-Breschkin J, Motoyama N. et al. ER stress triggers apoptosis by activating BH3-only protein Bim. Cell. 2007;129(7):1337–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Dudenhausen EE, Pan YX, Zhong C, Kilberg MS. Human CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta gene expression is activated by endoplasmic reticulum stress through an unfolded protein response element downstream of the protein coding sequence. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(27):27948–27956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313920200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piwien Pilipuk G, Galigniana MD, Schwartz J. Subnuclear localization of C/EBP beta is regulated by growth hormone and dependent on MAPK. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(37):35668–35677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305182200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smink JJ, Leutz A. Rapamycin and the transcription factor C/EBPbeta as a switch in osteoclast differentiation: implications for lytic bone diseases. J Mol Med. 2010;88(3):227–233. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0567-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin BR, Timchenko NA, Zahnow CA. Epidermal growth factor receptor stimulation activates the RNA binding protein CUG-BP1 and increases expression of C/EBPbeta-LIP in mammary epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(9):3682–3691. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.9.3682-3691.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descombes P, Schibler U. A liver-enriched transcriptional activator protein, LAP, and a transcriptional inhibitory protein, LIP, are translated from the same mRNA. Cell. 1991;67(3):569–579. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poli V, Mancini FP, Cortese R. IL-6DBP, a nuclear protein involved in interleukin-6 signal transduction, defines a new family of leucine zipper proteins related to C/EBP. Cell. 1990;63(3):643–653. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90459-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Bevilacqua E, Chiribau CB, Majumder M, Wang C, Croniger CM, Snider MD, Johnson PF, Hatzoglou M. Differential control of the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBPbeta) products liver-enriched transcriptional activating protein (LAP) and liver-enriched transcriptional inhibitory protein (LIP) and the regulation of gene expression during the response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(33):22443–22456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801046200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiribau C-B, Gaccioli F, Huang CC, Yuan CL, Hatzoglou M. Molecular symbiosis of CHOP and C/EBP beta isoform LIP contributes to endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(14):3722–3731. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01507-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa F, Akimoto T, Yamamoto H, Araki Y, Yoshie T, Mori K, Hayashi H, Nose K, Shibanuma M. Gene expression profiling identifies a role for CHOP during inhibition of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. J Biochem. 2009;146(1):123–132. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohoka N, Yoshii S, Hattori T, Onozaki K, Hayashi H. TRB3, a novel ER stress-inducible gene, is induced via ATF4-CHOP pathway and is involved in cell death. EMBO J. 2005;24(6):1243–1255. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du K, Herzig S, Kulkarni RN, Montminy M. TRB3: a tribbles homolog that inhibits Akt/PKB activation by insulin in liver. Science. 2003;300(5625):1574–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.1079817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Xu LG, Zhai Z, Shu HB. SINK is a p65-interacting negative regulator of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(29):27072–27079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209814200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitomi J, Katayama T, Eguchi Y, Kudo T, Taniguchi M, Koyama Y, Manabe T, Yamagishi S, Bando Y, Imaizumi K. et al. Involvement of caspase-4 in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis and Abeta-induced cell death. J Cell Biol. 2004;165(3):347–356. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200310015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki S, Hiratsuka T, Kuwahara R, Katayama T, Tohyama M. Caspase-4 is partially cleaved by calpain via the impairment of Ca2+ homeostasis under the ER stress. Neurochem Int. 2010;56(2):352–356. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(7):519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress responses. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65(6):862–894. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7383-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He CH, Gong P, Hu B, Stewart D, Choi ME, Choi AM, Alam J. Identification of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) as an Nrf2-interacting protein. Implication for heme oxygenase-1 gene regulation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(24):20858–20865. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101198200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagani M, Fabbri M, Benedetti C, Fassio A, Pilati S, Bulleid NJ, Cabibbo A, Sitia R. Endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductin 1-lbeta (ERO1-Lbeta), a human gene induced in the course of the unfolded protein response. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(31):23685–23692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003061200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibenhener ML, Geetha T, Wooten MW. Sequestosome 1/p62--more than just a scaffold. FEBS Lett. 2007;581(2):175–179. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh DY, Shin SH, Rhee SG. Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C and mitogenic signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1242(2):99–113. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(95)00006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito D, Walker JR, Thompson CS, Moroz I, Lin W, Veselits ML, Hakim AM, Fienberg AA, Thinakaran G. Characterization of stanniocalcin 2, a novel target of the mammalian unfolded protein response with cytoprotective properties. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(21):9456–9469. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9456-9469.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chigurupati S, Wei Z, Belal C, Vandermey M, Kyriazis GA, Arumugam TV, Chan SL. The homocysteine-inducible endoplasmic reticulum stress protein counteracts calcium store depletion and induction of CCAAT enhancer-binding protein homologous protein in a neurotoxin model of Parkinson disease. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(27):18323–18333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.020891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen AP, Camalier CE, Colburn NH. Epidermal expression of the translation inhibitor programmed cell death 4 suppresses tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2005;65(14):6034–6041. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meir O, Dvash E, Werman A, Rubinstein M. C/EBP-beta regulates endoplasmic reticulum stress-triggered cell death in mouse and human models. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9516. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo S, Saito A, Hino S, Murakami T, Ogata M, Kanemoto S, Nara S, Yamashita A, Yoshinaga K, Hara H. et al. BBF2H7, a novel transmembrane bZIP transcription factor, is a new type of endoplasmic reticulum stress transducer. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(5):1716–1729. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01552-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abassi YA, Xi B, Zhang W, Ye P, Kirstein SL, Gaylord MR, Feinstein SC, Wang X, Xu X. Kinetic cell-based morphological screening: prediction of mechanism of compound action and off-target effects. Chem Biol. 2009;16(7):712–723. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slagsvold JE, Pettersen CHH, Storvold GL, Follestad T, Krokan HE, Schonberg SA. DHA alters expression of target proteins of cancer therapy in chemoresistant SW620 colon cancer cells. Nutr Cancer. 2010;62(5):611–621. doi: 10.1080/01635580903532366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slagsvold JE, Pettersen CH, Follestad T, Krokan HE, Schonberg SA. The antiproliferative effect of EPA in HL60 cells is mediated by alterations in calcium homeostasis. Lipids. 2009;44(2):103–113. doi: 10.1007/s11745-008-3263-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abreu MM, Sealy L. The C/EBPbeta isoform, liver-inhibitory protein (LIP), induces autophagy in breast cancer cell lines. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316(19):3227–3238. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JW, Hendershot LM, Sherr CJ, Diehl JA. Mammalian unfolded protein response inhibits cyclin D1 translation and cell-cycle progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(15):8505–8510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Bailly-Maitre B, Reed JC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: cell life and death decisions. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(10):2656–2664. doi: 10.1172/JCI26373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A, Toescu EC. Endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) homeostasis and neuronal death. J Cell Mol Med. 2003;7(4):351–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2003.tb00238.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Wang J, Levichkin IV, Stasinopoulos S, Ryan MT, Hoogenraad NJ. A mitochondrial specific stress response in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 2002;21(17):4411–4419. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen L, Froyland L, Grav HJ, Berge RK. Up-regulated delta 9-desaturase gene expression by hypolipidemic peroxisome-proliferating fatty acids results in increased oleic acid content in liver and VLDL: accumulation of a delta 9-desaturated metabolite of tetradecylthioacetic acid. J Lipid Res. 1997;38(3):554–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayir H, Fadeel B, Palladino MJ, Witasp E, Kurnikov IV, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Amoscato AA, Jiang J, Kochanek PM. et al. Apoptotic interactions of cytochrome c: redox flirting with anionic phospholipids within and outside of mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757(5-6):648–659. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapkin RS, Seo J, McMurray DN, Lupton JR. Mechanisms by which docosahexaenoic acid and related fatty acids reduce colon cancer risk and inflammatory disorders of the intestine. Chem Phys Lipids. 2008;153(1):14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spydevold O, Bremer J. Induction of peroxisomal beta-oxidation in 7800 C1 Morris hepatoma cells in steady state by fatty acids and fatty acid analogues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;1003(1):72–79. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(89)90101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3:Article 3. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to muliple testing. J R Stat Soc. 1995;57(1):289–300. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16740248 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary gene expression results. Functional categories of significantly differentially expressed transcripts affected in SW620 cells treated with TTA (75 μM) for 24 h, as determined by Affymetrix microarray analysis (P < 0.05).

Supplementary experimental procedures. The file contains supplementing information about the experimental procedures including preparation of TTA stock solution and medium, gene expression experiments and antibodies used.