Abstract

The generation of effective antibodies depends upon somatic hypermutation (SHM) and class-switch recombination (CSR) of antibody genes by activation induced cytidine deaminase (AID) and the subsequent recruitment of error prone base excision and mismatch repair. While AID initiates and is required for SHM, more than half of the base changes that accumulate in V regions are not due to the direct deamination of dC to dU by AID, but rather arise through the recruitment of the mismatch repair complex (MMR) to the U:G mismatch created by AID and the subsequent perversion of mismatch repair from a high fidelity process to one that is very error prone. In addition, the generation of double-strand breaks (DSBs) is essential during CSR, and the resolution of AID-generated mismatches by MMR to promote such DSBs is critical for the efficiency of the process. While a great deal has been learned about how AID and MMR cause hypermutations and DSBs, it is still unclear how the error prone aspect of these processes is largely restricted to antibody genes. The use of knockout models and mice expressing mismatch repair proteins with separation-of-function point mutations have been decisive in gaining a better understanding of the roles of each of the major MMR proteins and providing further insight into how mutation and repair are coordinated. Here, we review the cascade of MMR factors and repair signals that are diverted from their canonical error free role and hijacked by B cells to promote genetic diversification of the Ig locus. This error prone process involves AID as the inducer of enzymatically-mediated DNA mismatches, and a plethora of downstream MMR factors acting as sensors, adaptors and effectors of a complex and tightly regulated process from much of which is not yet well understood.

Keywords: mismatch repair, class switch recombination, somatic hypermutation, AID, DSB, epigenetic, antibody diversity

Organisms from all kingdoms of life are under constant cytotoxic threats. Genotoxic insults are particularly detrimental because they could alter the genetic code, ultimately affecting the integrity of the heritable cellular material. That is why cells have evolved intricate DNA repair signaling cascades to deal with such insults. Ironically, though, specific cell types have developed ways to ‘hijack’ and ‘manipulate’ DNA damage to their advantage. Germ cells, for example, promote DNA damage during meiosis to create biodiversity and drive evolution [1,2,3,4]; while B cells instigate DNA damage at various stages of their development to generate a large repertoire of high affinity protective antibodies [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]

AID, an inducer of enzymatically-mediated DNA mismatches

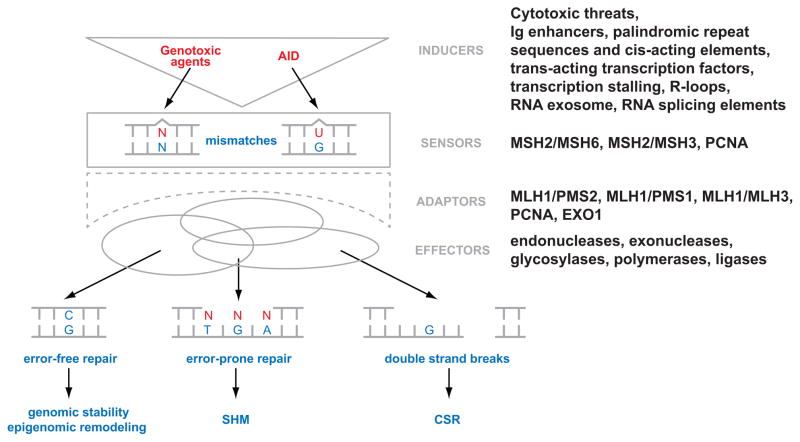

In vertebrates, germline encoded antibodies are usually of low affinity, hence ineffective in protecting from pathogenic organisms and their products. Upon interaction with antigen, antibody forming B cells increase their expression of the cytosine deaminating enzyme, AID, which creates U:G mismatches primarily at the immunoglobulin (Ig) V region. This mutagenic step, albeit induced and regulated, mimics the formation of a spontaneously or chemically provoked DNA mismatch, which could confront any cell. The distinctive difference from what takes place outside the Ig locus, is that the AID-mediated U:G mismatches promote the error prone dimension of mismatch repair (MMR) and base excision repair (BER) machineries (Figure 1) [5,6,7,8,9,10,12]. Together these repair complexes amplify the mutation frequency of AID to reach 10−5-10−3/base-pair/generation [13]. This somatic hypermutation (SHM) process, along with the selection for higher-affinity clones, is responsible for the affinity maturation of antibodies [14,15,16,17,18].

Figure 1.

The multifaceted MMR system encompasses the hierarchical recruitment of a plethora of factors with distinct functions, which are activated upon the generation of a DNA mismatch by inducers like AID. One way to categorize these MMR factors is based on their major role as sensors of the mismatch, as adaptors that orchestrate the diverse downstream signaling cascade, or as final effectors. Beyond the canonical role of MMR to assure genomic stability, there is the potential impact of DNA repair in AID/APOBEC-induced epigenetic remodeling, as well as the non-canonical role of MMR in SHM and CSR in B cells.

AID induced U:G mismatches are also required to initiate class switch recombination (CSR) at the switch (S) repeat regions upstream of the Ig constant region genes [19,20,21]. While many of the details have yet to be resolved, unlike SHM, the U:G mismatches here are processed into concerted DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) at two different S regions. This allows recombination of the rearranged V region from Sμ to one or another of the downstream constant regions in different progeny of the B cell clone [22,23]. Isotype switching allows each antigen-binding site to be expressed with each of the isotypes (8 total in humans), so that the resulting antibodies can be distributed throughout the body and carry out a wide variety of effector functions.

Patients who have inactivating mutations in AID are unable to carry out either SHM or CSR, have Type II Hyper-IgM Immunodeficiency Syndrome and require antibody replacement therapy and antibiotics to survive [24,25]. The AID-dependent mutations and the recombination process required for CSR are sometimes mistargeted to proto-oncogenes [26,27], such as Bcl6 and c-myc, and the resulting uncontrolled expression of those oncogenes is responsible for ~85% of non-Hodgkin’s B cell malignancies in humans [28,29].

How and why is AID preferentially directed to specific regions of the Ig locus remains unclear but recent studies have demonstrated that AID targeting and activity require transcription, Ig enhancers, palindromic repeat sequences, trans-acting transcription factors, transcription stalling, R-loop formation, RNA splicing elements and RNA exosome degradation and processing [5,30,31,32,33,34,35,36].

Genetic and epigenetic consequences of enzymatically-mediated DNA mismatches

AID belongs to a family of cytosine deaminases, collectively known as APOBECs. Because cytosines in vertebrates can be methylated, they are conferred with a unique epigenetic property [11,37,38,39,40]. Enzymes, such as APOBECs, that can deaminate cytosine bases tend to also affect the cellular epigenetic code by creating T:G mismatches, since the deamination of 5-methylcytosine (meC) transforms the base into a thymine. In fact, due to the evolutionary conservation of the APOBECs and their expression in many different cell types, it might not be surprising if their epigenetic capability is their truly original activity [41,42,43]; while B cells usurped that property of AID to mediate mutations at the Ig locus of B cells [10]. The role of meC and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (hmC) [44,45,46] has been epigenetically implicated in the regulation of histone modifications and of gene expression [47,48]. Recent studies strongly suggest that APOBEC proteins – including AID – have the potential to promote demethylation of meC [38,49,50,51] and hmC [47], which could result in epigenomic remodeling of the cell (Figure 1). This is initiated by cytosine deamination which leads to the emergence of a T:G or hmU:G mismatches, respectively. APOBEC/AID hence could activate or inactivate the expression of individual genes either by causing mutations or by actively demethylating promoters of critical genes [43,47]. But to do that APOBEC/AID will require the activity of repair factors, likely including MMR, which could recognize and process the ensued mismatch. The glycosylase TDG has already been implicated in DNA demethylation [52,53]. It remains to be seen whether other glycosylases, such as MDB4, with an affinity towards T:G mismatches, may also be involved.

What is clear though is that AID is necessary to induce an enzymatically-mediated mismatch in the DNA – be it of genetic or epigenetic consequences – but it is not sufficient in itself. AID requires the activity of a number of downstream DNA repair pathways – primarily MMR – to conclude its function. In this brief review, we will use the AID-mediated enzymatic DNA mismatch as our focal point to describe the downstream MMR signaling cascades that govern the mediation of SHM and CSR. We will also, when appropriate, compare and contrast the differences in signaling between what happens at the Ig locus versus elsewhere in the genome.

MMR sensors and the detection of DNA mismatches

Mismatch repair is highly conserved from bacteria to humans [54,55]. During normal DNA replication in mammalian cells, between 70 and 200 dUs are thought to be spontaneously generated during each S phase of the cell cycle [56]. This is but a subset of the broader MMR substrate recognition library, yet it is indistinguishable from the U:G mismatches created by AID cytosine deamination. In either case, MMR recognizes single mismatched bases by the MSH2/MSH6 heterodimer (MutSα) (Figure 1). Larger mismatches – possibly caused by deamination of cytosine clusters or by insertions/deletions – are recognized by MSH2/MSH3 (MutSβ). Since a functional role for the latter complex has not been observed in SHM or CSR (Table 1) [57,58], we will henceforth focus on the sensing mechanism of MutSα.

Table 1.

MMR protein deletions and mutants in SHM and CSR

| Key MMR Factor | Deletions & Mutants | Key Disturbed Domain(s) | Affected Binding Partners | Suspected Properties Affected | Ig Phenotype | References | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | A | E | SHM | CSR | |||||||

| GC | AT | Frq | μH | ||||||||

| MSH2 | Msh2−/− | DNA; PIP box; Msh3/6; ATPase | All | ✓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [61,81,146,147, 148,149] | ||

| Msh2G674A | ATPase | Unknown | ✓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | [67] | |||

| MSH3 | Msh3−/− | DNA; Msh2; ATPase | All | ✓ | = | = | = | = | [57,58] | ||

| MSH6 | Msh6−/− | PIP box; DNA; Msh2; ATPase | All | ✓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | = | [57,58] | ||

| Msh6T1217D | ATPase | Unknown | ✓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | = | [68] | |||

| MLH1 | Mlh1−/− | ATPase; Msh2/6; MLH3/Pms1/2 | All | ✓ | = | = | ↓ | ↑ | [79,80,81] | ||

| Mlh1G167R | ATPase | None Suspected | ✓ | = | = | ↓ | ↑ | Unpublished data | |||

| MLH3 | Mlh3−/− | ATPase; Mlh1; | All | ✓ | ↓ | ↑ | = | ↓ | [83,84] | ||

| PMS1 | Pms1−/− | ATPase; Mlh1; HMG-box (DNA binding) | All | ✓ | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| PMS2 | Pms2−/− | ATPase; Mlh1; Endonuclease | All | ✓ | ✓ | = | = | ↓ | ↑ | [82] | |

| Pms2E702K | Endonuclease | None Suspected | ✓ | = | = | ↓ | = | [88] | |||

| PCNA | Pcna−/− | DNA binding; Protein binding | All | ✓ | ✓ | NA | NA | NA | NA | [12] | |

| PcnaK164R | Error prone protein binding | Polη; Other | ✓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [12,62] | |||

| MBD4 | Mbd4−/− | Mlh1; meCpG; Glycosylase | All | ✓ | = | = | = | NA | [113] | ||

| EXO1 | Exo1Δex6 | Msh2/6; Mlh1; Exonuclease | Unknown | ✓ | ✓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [150] | |

| POLη | Polη−/− | PIP box; Polymerase | All | ✓ | ↑ | ↓ | = | NA | [66,99] | ||

| LIG1 | Lig1−/− | DNA ligase; DNA binding | All | ✓ | NA | NA | NA | NA | [151] | ||

S: sensor; A: adaptor; E: effector; Ig: Immunoglobulin; SHM: somatic hypermutation; CSR: class switch recombination; Frq: frequency; μH: S-S microhomologies; NA: not available

It is unclear whether the MSH2/MSH6 complex is constantly scanning the genome for mismatches or whether it binds to DNA in situ as a mismatch arises. Some suggest that since PCNA binds Msh2 and Msh6, this allows the sensor complex to scan the DNA along with PCNA. Alternatively, the sensor complex could recruit PCNA after processing a DNA mismatch, which transiently exposes a nicked ssDNA leading to the loading of the PCNA clamp followed by polymerases required to fill the ensued DNA gap [59,60]. It is also plausible that both processes happen but in different stages of the cell cycle, whereby the first scenario is more likely to occur during S phase. This has proven hard to verify conclusively since PCNA null mice are not viable. However, studies on PCNAK164R mice, where PCNA cannot be ubiquitylated, lends further credence to the idea that additional factors are recruited by ubiquitylated PCNA at a subsequent step since PCNAK164R B cells develop milder SHM and CSR defects compared to Msh2 or Msh6 null or mutant cells (Table 1) [10,12,61,62]. How PCNA is mono- and poly-ubiquitylated as well as what downstream mechanisms are activated upon ubiquitylation are just beginning to be understood. RAD6/RAD18-mediated site-specific mono-ubiquitylation of PCNA at lysine residue 164 [63,64] and deubiquitylation primarily by USP1 [65] are thought to control the recruitment of error prone polymerases like Polη, which is a major contributor to SHM after MSH2/MSH6/PCNA have identified a mismatch [66].

In either case, the active sensing of a U:G mismatch causes MSH2/MSH6 to trigger a cascade of ATP dependent events that recruit specialized adaptors, which in turn activate downstream effectors (Figure 1). Both MSH2 and MSH6 have ATPase domains (Table1). The ATPase function of either members of the MutSα complex appears to be essential for the DNA mismatch. B cells with ATPase defective MSH2 (MSH2G674A) or MSH6 (MSH6T1217D) have varying reductions in SHM and CSR in comparison with MSH2 or Msh6 null activated B cells, respectively (Table 1) [67,68]. The Msh2G674A missense mutation allows the continued expression of the MSH2 protein and its binding to DNA, but interferes with the binding and processing of ATP by MSH2 [69]. This blocks its ability to repair the mismatched bases. Similar MSH2 mutations that affect ATP processing are frequently found in HNPCC patients [70,71]. In mouse cells, the mutant protein retains the ability – in vitro and in vivo – to bind to mismatches and to signal for apoptosis, but Msh2G674A/G674A cells and lysates cannot repair mismatched bases. As with Msh2−/− mice, V region mutations in Msh2G674A/G674A mice were primarily in G:C pairs within AID hot spot motifs and there was a significant decrease in A:T mutations. Like the Msh2−/− B cells, there was a 30–50% decrease in isotype switching to IgG1 and IgG3 in primary mouse B cells that were stimulated to switch in vitro. Comparing the switch recombination sites in Msh2G674A/G674A with Msh2−/− and wild type mice, we found that the mutant mice had an increase in large insertions, which is also seen in Msh2−/− mice. However, the MSH2-deficient or wild type mice did not show the longer microhomologies that were later seen in PMS2- and MLH1-deficient mice (Table1). These differences in the detailed characteristics of the recombination sites must reflect differences in how MSH2, the MSH2G674A mutant and the downstream MMR elements function during recombination in vivo. This suggests that the various MMR factors have overlapping, but also distinct functions that could include providing scaffolding for different downstream factors. Studies with the ATPase mutant of MSH2 indicated that the major role of MMR in SHM and CSR is error prone repair of the G:U mismatch, and that the ability of MMR to signal for apoptosis was not important either in the mutation of Ig V and SRs or in lymphomagenesis [67].

MSH6 knock-in mice (Msh6T1217D) carrying a mutation that affects the ATPase function of MutSα have been generated. A comparable mutation in yeast causes a loss of the ATPase activity of the MSH2/MSH6 dimer and in humans leads to early onset HNPCC [72]. In mice, this mutation allows the MSH2/MSH6 dimer to bind the mismatch, but it cannot be released from DNA by ATP in vitro and there is no repair of the mismatch. However, signaling for apoptosis is retained [72]. Like the Msh6−/− mice, the Msh6TD/TD mice have a decrease in SHM largely attributable to a loss of mutations in A:T. However, the actual decrease in SHM in the Msh6TD/TD mice is intermediate between the wild type and the knock out, suggesting that the MSH6 protein has an ATP independent function that does not require the repair of the mutation. The Msh6TD/TD mice have a decrease in CSR that is comparable to the knock out, but the sites of recombination in the S-S microhomologies, which were abnormal in the knockout, are like the wild type mice, again suggesting a role for the MSH6 protein itself. Like the MSH6-deficient mice, the mutations in V are more focused than in the wild type mice and Msh2−/− mice, with fewer hotspots being targeted. By analyzing a very large number of sequences, we were able to show that the actual hotspots that are mutated in G:C in the TD mice are different from those observed in Msh6−/− and wild type mice and that more AID cold spots were targeted, some of which do not undergo mutation in either the wild type or knockout mice. Since the MSH6TD protein remains associated with DNA in vitro, and there is a dominant negative phenotype for cancer [72], one of many possibilities is that this mutant protein binds to AID induced mismatches and blocks subsequent deamination of neighboring bases by AID in the next round of AID induced mutations. Recent studies on the possible functional interaction of AID with MSH2 and MSH6 seem to support some sort of role for MutSα in recruiting AID to hotspots [73].

It has been a long-standing question whether MSH2 and MSH6 could have independent functions in MMR. MSH2/MSH6 doubly defective and MSH2/MSH6/MSH3 triply defective mice have been analyzed for SHM and CSR and appear largely indistinguishable from the single Msh2−/− and Msh6−/− deficient mice [61]. Combined, all these results suggest that the heterodimer formed by MSH2 and MSH6, but not MSH3, is critical for detecting AID-generated mismatches at the Ig locus and plays the major role activating the downstream mechanisms that introduce mutations at the A:T bases surrounding the initial U:G mismatch. To reiterate, MSH2 and MSH6 are unlikely to be just sensors. Owing to their variety of domains (Table 1) they are also structurally required as adaptors for the recruitment of downstream factors, such as PCNA, MLH1, PMS2, and EXO1 [74,75,76]. Whether the ATPase activity would be required to mediate the sensory and/or adapter functions of MutSα remains to be seen. But the separation-of-function phenotypes observed in point mutant mice have and continue to offer unique opportunities to study the overlapping functions of MSH2 and MSH6 in antibody diversification.

MMR adaptors and their role in relaying the signaling response

MLH1/PMS2 (MutLα), MLH1/PMS1 (MutLβ), or MLH1/MLH3 (MutLγ) are considered the canonical MMR adaptor molecules or “match-makers” that coordinate the recognition of the mismatch with its excision via recruitment of downstream factors and introduction of a single stranded nick 5′ or 3′ to the mismatch [77,78] (Figure 1). However, only MutLα has been significantly associated to the repair of AID-generated mismatches at the Ig locus. Yet, it has been confounding that mice deficient in MLH1 or PMS2 have a significant defect in CSR but undergo normal SHM ([79,80,81,82]; Table1); a phenotype distinct from the one observed in MSH2- or MSH6-deficient mice. One possibility is that there are other MMR proteins that could substitute for MLH1 and PMS2. But analysis of the most likely candidates – PMS1 and MLH3 – renders the likelihood of that option remote. MLH3 deficient mice have a normal rate of CSR and display only a slight increased rate of SHM (Table 1) [83,84]. PMS1 mouse models, on the other hand, are yet to be generated; but studies have – so far – not suggested a PMS1 function that is independent of MLH1 [76,85]. These findings support the notion that MutLα might be the major orchestrator that distinctly favors CSR over SHM.

Since redundancies could not explain the variance in the antibody phenotype between MutSα and MutLα complexes, this has led to the suggestion that MutLα – as characteristic of adaptors – diverges the MMR signaling cascade downstream of the sensor in a differential manner in SHM and CSR, which vary in their DNA damage preference. Hence, MutLα is believed to favor the formation of DSBs for the latter process but is dispensable for the generation of point mutations in V regions for the former [10,79,80,81]. But how does MutLα mechanistically do this? One possibility is that MutLα affects the processivity of the downstream exonuclease(s), such as EXO1, hence provides a better chance for DSB formation. But in vitro studies in that regard has been inconclusive [86,87]. Yet, it is possible that in vivo, there could be some effect of MutLα on EXO1 processivity, but that might depend on auxiliary factors that could be missing in the purified protein analysis [86,87]. In support of a possible role in vivo, the interactome studies done on human MutLα has shown that MLH1 and PMS2 interact with a number of known and uncharacterized proteins [85]. Of particular interest from those hits is the interaction of both MLH1 and PMS2 (but not PMS1) with DNAPK-cs among other DNA repair proteins. DNAPK-cs is considered an orchestrator of the NHEJ repair pathway and this recruitment could bias the system towards NHEJ repair hence minimizing the chance of DNA end resection and generation of microhomology. Furthermore, Pms2−/− mice display an increase in S-S microhomology, while PMS2 nuclease defective mice show normal microhomology even though both have a decrease in CSR ([88]; discussed below). This suggests that there must be PMS2 nuclease dependent and independent functions and, therefore, that MutLα might be needed as an adaptor to recruit additional proteins which might be necessary for DNA end processing downstream of the DSB at S regions.

Still, why is MutLα important for global MMR but superfluous for SHM? Is this duality regulated through ATPase-dependent conformational changes driven by MLH1? And if not MutLα, what then mediates missense mutations at the Ig locus? Firstly, the ATPase function of MLH1 appears to be essential for its role in CSR (Table1), but the exact mechanism of how that is mediated and why there are redundancies in ATPase activities among the MutS and MutL complexes remains an open question. Secondly, a potential answer to how error prone repair might be targeted to Ig genes [89] was introduced by the discovery of translesional and other error prone polymerases in mammalian cells [90] and the subsequent description in yeast that these enzymes could be recruited to DNA lesions, including G:U mismatches, by PCNA that had been mono-ubiquitylated at residue K164 [64,91,92]. Biochemical studies show that mono-ubiquitylated PCNA binds Polη [91,92], though there is some debate as to whether this modification is required to fully activate Polη [93,94]. Avian DT40 cells that lack the ability to mono-ubiquitylate PCNA do not seem to carry out the MMR-dependent phase of SHM, and mutations in the V region are decreased as a result [95,96,97]. Likewise in mammalian B cells, ubiquitylation of PCNA plays a role in recruiting error prone repair to the Ig V region during the MMR-mediated second phase of SHM [12,62]. However, the fact that there are persisting mutations in A:T in PCNAK164R B cells suggests that Polη can still be recruited by PCNA even in the absence of mono-ubiquitylation [98] or that other error prone polymerases are compensating for the deficient recruitment of Polη. Another thorny issue is why B cells from PCNAK164R also display a decrease in CSR; especially since error prone polymerases – such as Polη-deficient mice – have not been shown to be involved in CSR [66,99]. This suggests that mono-ubiquitinated PCNA might have additional roles in CSR, possibly through DSB repair, which remain to be explored.

Taken together, the ideas presented above seem to suggest that at least three diverging signaling responses take place downstream of the sensor MutSα (Figure 1). The first occurs at V regions during SHM and is mediated by a mono-ubiquitinated PCNA adaptor, which recruits error prone polymerases to amplify the AID-initiated missense mutations. The second occurs via the MutLα adaptor and occurs at S repeats to promote DSB formation and CSR. The third is what takes place globally in the rest of the genome, which relies on faithful DNA polymerases, and is possibly dependent on unmodified or alternate modified forms of PCNA [100,101,102]. What triggers this signaling divergence is still under intense investigation. Some believe cis-acting elements in the Ig locus drives the MMR response in favorable directions others believe that the chromatin architecture along with protein interactions and modifications play an important role [103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111].

MMR effectors and their role in Ig diversification

MMR effectors can be glycosylases or DNA nucleases that lead to the excision of the mismatch and the removal of a stretch surrounding it [112]. Effectors also are responsible for re-synthesizing the excised DNA strand by high or low fidelity polymerases, and ultimately promoting the ligation of the DNA ends, primarily by DNA ligase I (Figure 1).

Most DNA glycosylases, such as UNG and SMUG1, are part of the BER machinery and differentially contribute to Ig gene mutation in SHM and CSR [14]. Others, like MBD4, a glycosylase that primarily recognizes T:G mismatches, stood out as a direct interactor with MLH1 but did not demonstrate a significant role in SHM or CSR [113]. In summary, multiple sensor and adaptor functions could be ascribed to BER in what appears to be a parallel cascade to MMR. However, recent work has explored an intriguing and yet not well understood cooperation between BER and MMR to repair AID lesions [114,115].

As such, DNA nucleases remain the main excising factors in MMR. It is known in bacteria that MMR uses the MutH endonuclease to introduce nicks in the strand that contains the mismatched base based on its DNA methylation status, but the homologue of MutH in eukaryotes has not been identified [54,116]. The discovery of a latent endonuclease activity in PMS2 (and MLH3) and the confirmation of the importance of this activity in yeast [78,117] provide the first clue as to how the necessary single stranded nicks might occur in mammalian cells [77,78]. In addition, it provided an additional and unexpected effector activity for the MutLα complex to go along its adaptor function. Subsequent studies on PMS2 nuclease defective mice (PMS2E702K) [88] provided intriguing results. It turns out that although the PMS2 nuclease activity is indeed critical for CSR, presumably through the generation of DSBs, it strikingly did not alter S-S region microhomologies. This suggests that the generation and processing of DSBs are a multi-step process where MLH1 and PMS2 function at multiple different steps in the generation, processing, and repair of DSBs during CSR (Table1).

Since PMS2 functions as an endonuclease, an exonuclease is still required to resect DNA ends for subsequent polymerase filling. Exonuclease 1 (EXO1) is a 5′-3′ exonuclease that is recruited by the MSH2/MSH6 heterodimer once it has engaged mismatched bases. It is still possible that there are other exonucleases that may play a role in MMR [85], but EXO1-deficient mice had a decrease in A:T mutations in the V region and 70% reduction in CSR that was comparable to that seen in the MSH2-deficient and mutant mice. This confirms that EXO1, be it directly or indirectly, is involved in excising the DNA strand containing the G:U mismatch in SHM and CSR. The analysis of the switch recombination sites revealed a decrease in long microhomologies and an increase in long insertions when compared to wild type littermates. These are the same changes that are seen in Msh2−/− mice.

In mice and humans deficient in Polη, mutations in A:T bases are greatly reduced, indicating that it is the major translesional error prone polymerase recruited to antibody V regions by MMR [66,118,119,120]. However, other translesional polymerases – such as Polθ, Polι, and Polζ – may work in concert with Polη, or may be able to substitute for it [119,121,122,123,124,125].

In CSR, the U:G mismatches created by AID are converted into single-stranded nicks by UNG and apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease (APE1), or by MMR [126], and are further processed to form the double stranded breaks that are required for the recombination between the donor and recipient S repeat [127,128]. This process is completed by the DNA DSB repair machinery – primarily the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) branch – which involves many additional factors which follow an independent signaling cascade constituted by a separate set of DNA damage sensors, adaptors, and effectors. This signaling cascade has been recently described in more detail [129,130,131,132,133].

The paradoxical dichotomy

As described so far, the complete loss or mutations in MMR proteins can lead to immunodeficiency due to decreased mutation rates at the Ig locus during SHM and CSR. This error prone function of MMR has been observed in both humans and mice [10,134,135]. Ironically, mutations in MMR proteins are also associated with impairment of their canonical error free function, resulting in global microsatellite instability, increased genomic mutations, and tumor formation both in humans and in mice [136]. In this sense, MMR protein mutations are a major cause of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC or Lynch syndrome) and are seen in sporadic colon cancer as well as endometrial, lung, breast, pancreatic, gastric and prostate cancers [137]. Many of the mutations in HNPCC are in MSH2 and MLH1 and some are in MSH6 [138].

These seemingly paradoxical outcomes have been an intriguing aspect in the study of MMR. Even though the mechanistic details are yet to be worked out, the most plausible explanation for such a discrepancy is that signaling downstream of the DNA mismatch occurs differently at the Ig locus versus the rest of the genome. Interestingly, a recent study has shown that error prone repair of AID-induced mutations also occurs in a number of non-Ig genes such as Bcl6, even though they have much lower rates of mutation than V and SRs. Intriguingly, many non-Ig genes that are targeted by AID are repaired in a mostly error free way [27]. However, AID-dependent mutations in the Ig locus are repaired in an error prone way. This suggests that the Ig genes are both targeted for error prone repair and protected or excluded from error free repair. But how is that really achieved? Selective targeting of error prone MMR repair to V and different S repeats is likely to require, among other things, enhanced accessibility to those regions [107]. Since accessibility is partly mediated by changes in chromatin structure [139], studies have now shown that modifications in histone acetylation and methylation are associated with S repeats that are targeted for mutation and recombination by stimulation with cytokines [109,140,141,142,143,144]. These and other histone modifications might be important in targeting the various factors responsible for CSR, and potentially SHM. In summary, the overall mechanism is likely a combination of, specific targeting of the mismatch inducer (AID), cis-acting DNA elements, transcriptional regulation and epigenetic modifications that demarcate the Ig locus from the rest of the genome.

Conclusion

Paradoxically, MMR maintains stability throughout the genome but is responsible for up to 60% of the mutations in V and S regions of the Ig locus; and thus much of the genomic instability in GC B cells [145]. How activated B cells selectively maintain the tight balance between the error prone versus the error free aspects of MMR during the different phases of their cell cycle remains an intriguingly open question. More rigorous biochemical and cellular analyses along with separation-of-function mutations in animal models will undoubtedly unravel a better understanding of the intricate signaling cascades that govern antibody diversification. This might eventually help uncover the mechanistic associations between the maintenance of genomic integrity and tumorigenesis in the adaptive immune response.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants CA72649 and CA102705 (to M.D.S.) and CA76329 and CA93484 (to W.E.). M.D.S. is supported by the Harry Eagle Chair, provided by the National Women’s Division of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Marcon E, Moens PB. The evolution of meiosis: recruitment and modification of somatic DNA-repair proteins. BioEssays : news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 2005;27:795–808. doi: 10.1002/bies.20264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Youds JL, Boulton SJ. The choice in meiosis - defining the factors that influence crossover or non-crossover formation. Journal of cell science. 2011;124:501–513. doi: 10.1242/jcs.074427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen SL, Sekelsky J. Meiotic versus mitotic recombination: two different routes for double-strand break repair: the different functions of meiotic versus mitotic DSB repair are reflected in different pathway usage and different outcomes. BioEssays : news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 2010;32:1058–1066. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson SP, Bartek J. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature. 2009;461:1071–1078. doi: 10.1038/nature08467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pavri R, Nussenzweig MC. AID targeting in antibody diversity. Adv Immunol. 2011;110:1–26. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387663-8.00005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenberg BR, Papavasiliou FN. Beyond SHM and CSR: AID and related cytidine deaminases in the host response to viral infection. Adv Immunol. 2007;94:215–244. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)94007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudhuri J, Basu U, Zarrin A, Yan C, Franco S, Perlot T, Vuong B, Wang J, Phan RT, Datta A, Manis J, Alt FW. Evolution of the immunoglobulin heavy chain class switch recombination mechanism. Adv Immunol. 2007;94:157–214. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)94006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durandy A, Peron S, Taubenheim N, Fischer A. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase: structure-function relationship as based on the study of mutants. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:1185–1191. doi: 10.1002/humu.20414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu Z, Fulop Z, Zhong Y, Evinger AJ, 3rd, Zan H, Casali P. DNA lesions and repair in immunoglobulin class switch recombination and somatic hypermutation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1050:146–162. doi: 10.1196/annals.1313.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peled JU, Kuang FL, Iglesias-Ussel MD, Roa S, Kalis SL, Goodman MF, Scharff MD. The biochemistry of somatic hypermutation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:481–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maul RW, Gearhart PJ. AID and somatic hypermutation. Adv Immunol. 2010;105:159–191. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(10)05006-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roa S, Avdievich E, Peled JU, Maccarthy T, Werling U, Kuang FL, Kan R, Zhao C, Bergman A, Cohen PE, Edelmann W, Scharff MD. Ubiquitylated PCNA plays a role in somatic hypermutation and class-switch recombination and is required for meiotic progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16248–16253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808182105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacob J, Przylepa J, Miller C, Kelsoe G. In situ studies of the primary immune response to (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl)acetyl. III. The kinetics of V region mutation and selection in germinal center B cells. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1293–1307. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.4.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Noia JM, Neuberger MS. Molecular Mechanisms of Antibody Somatic Hypermutation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:1–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.061705.090740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maizels N. Immunoglobulin gene diversification. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:23–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.110544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Z, Woo CJ, Iglesias-Ussel MD, Ronai D, Scharff MD. The generation of antibody diversity through somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1–11. doi: 10.1101/gad.1161904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teng G, Papavasiliou FN. Immunoglobulin Somatic Hypermutation. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41:107–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Carter RH. CD19 regulates B cell maturation, proliferation, and positive selection in the FDC zone of murine splenic germinal centers. Immunity. 2005;22:749–761. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muramatsu M, Kinoshita K, Fagarasan S, Yamada S, Shinkai Y, Honjo T. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 2000;102:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muramatsu M, Sankaranand VS, Anant S, Sugai M, Kinoshita K, Davidson NO, Honjo T. Specific expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a novel member of the RNA-editing deaminase family in germinal center B cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18470–18476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stavnezer J. Complex regulation and function of activation-induced cytidine deaminase. Trends in immunology. 2011;32:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manis JP, Tian M, Alt FW. Mechanism and control of class-switch recombination. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:31–39. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stavnezer J. Molecular processes that regulate class switching. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2000;245:127–168. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59641-4_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Revy P, Muto T, Levy Y, Geissmann F, Plebani A, Sanal O, Catalan N, Forveille M, Dufourcq-Labelouse R, Gennery A, Tezcan I, Ersoy F, Kayserili H, Ugazio AG, Brousse N, Muramatsu M, Notarangelo LD, Kinoshita K, Honjo T, Fischer A, Durandy A. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) deficiency causes the autosomal recessive form of the Hyper-IgM syndrome (HIGM2) Cell. 2000;102:565–575. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Durandy A, Peron S, Fischer A. Hyper-IgM syndromes. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006;18:369–376. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000231905.12172.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pasqualucci L, Bhagat G, Jankovic M, Compagno M, Smith P, Muramatsu M, Honjo T, Morse HC, 3rd, Nussenzweig MC, Dalla-Favera R. AID is required for germinal center-derived lymphomagenesis. Nat Genet. 2008;40:108–112. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu M, Duke JL, Richter DJ, Vinuesa CG, Goodnow CC, Kleinstein SH, Schatz DG. Two levels of protection for the B cell genome during somatic hypermutation. Nature. 2008;451:841–845. doi: 10.1038/nature06547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monti S, Savage KJ, Kutok JL, Feuerhake F, Kurtin P, Mihm M, Wu B, Pasqualucci L, Neuberg D, Aguiar RC, Dal Cin P, Ladd C, Pinkus GS, Salles G, Harris NL, Dalla-Favera R, Habermann TM, Aster JC, Golub TR, Shipp MA. Molecular profiling of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identifies robust subtypes including one characterized by host inflammatory response. Blood. 2005;105:1851–1861. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okazaki IM, Kotani A, Honjo T. Role of AID in Tumorigenesis. Adv Immunol. 2007;94:245–273. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)94008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Storb U, Shen HM, Longerich S, Ratnam S, Tanaka A, Bozek G, Pylawka S. Targeting of AID to immunoglobulin genes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;596:83–91. doi: 10.1007/0-387-46530-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michael N, Shen HM, Longerich S, Kim N, Longacre A, Storb U. The E box motif CAGGTG enhances somatic hypermutation without enhancing transcription. Immunity. 2003;19:235–242. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen HM, Michael N, Kim N, Storb U. The TATA binding protein, c-Myc and survivin genes are not somatically hypermutated, while Ig and BCL6 genes are hypermutated in human memory B cells. Int Immunol. 2000;12:1085–1093. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.7.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Storb U, Peters A, Klotz E, Kim N, Shen HM, Hackett J, Rogerson B, Martin TE. Cis-acting sequences that affect somatic hypermutation of Ig genes. Immunol Rev. 1998;162:153–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peters A, Storb U. Somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes is linked to transcription initiation. Immunity. 1996;4:57–65. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pavri R, Gazumyan A, Jankovic M, Di Virgilio M, Klein I, Ansarah-Sobrinho C, Resch W, Yamane A, Reina San-Martin B, Barreto V, Nieland TJ, Root DE, Casellas R, Nussenzweig MC. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase targets DNA at sites of RNA polymerase II stalling by interaction with Spt5. Cell. 2010;143:122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Basu U, Meng FL, Keim C, Grinstein V, Pefanis E, Eccleston J, Zhang T, Myers D, Wasserman CR, Wesemann DR, Januszyk K, Gregory RI, Deng H, Lima CD, Alt FW. The RNA exosome targets the AID cytidine deaminase to both strands of transcribed duplex DNA substrates. Cell. 2011;144:353–363. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chahwan R, Wontakal SN, Roa S. Crosstalk between genetic and epigenetic information through cytosine deamination. Trends Genet. 2010;26:443–448. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morgan HD, Dean W, Coker HA, Reik W, Petersen-Mahrt SK. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase deaminates 5-methylcytosine in DNA and is expressed in pluripotent tissues: implications for epigenetic reprogramming. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52353–52360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407695200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Conticello SG, Langlois MA, Yang Z, Neuberger MS. DNA deamination in immunity: AID in the context of its APOBEC relatives. Adv Immunol. 2007;94:37–73. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)94002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beale RC, Petersen-Mahrt SK, Watt IN, Harris RS, Rada C, Neuberger MS. Comparison of the differential context-dependence of DNA deamination by APOBEC enzymes: correlation with mutation spectra in vivo. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:585–596. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rai K, Huggins IJ, James SR, Karpf AR, Jones DA, Cairns BR. DNA demethylation in zebrafish involves the coupling of a deaminase, a glycosylase, and gadd45. Cell. 2008;135:1201–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Popp C, Dean W, Feng S, Cokus SJ, Andrews S, Pellegrini M, Jacobsen SE, Reik W. Genome-wide erasure of DNA methylation in mouse primordial germ cells is affected by AID deficiency. Nature. 2010;463:1101–1105. doi: 10.1038/nature08829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhutani N, Brady JJ, Damian M, Sacco A, Corbel SY, Blau HM. Reprogramming towards pluripotency requires AID-dependent DNA demethylation. Nature. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nature08752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loenarz C, Schofield CJ. Oxygenase catalyzed 5-methylcytosine hydroxylation. Chem Biol. 2009;16:580–583. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kriaucionis S, Heintz N. The nuclear DNA base 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is present in Purkinje neurons and the brain. Science. 2009;324:929–930. doi: 10.1126/science.1169786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arlt MF, Glover TW. Inhibition of topoisomerase I prevents chromosome breakage at common fragile sites. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:678–689. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo JU, Su Y, Zhong C, Ming GL, Song H. Hydroxylation of 5-Methylcytosine by TET1 Promotes Active DNA Demethylation in the Adult Brain. Cell. 2011;145:423–434. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sytnikova YA, Kubarenko AV, Schafer A, Weber AN, Niehrs C. Gadd45a is an RNA binding protein and is localized in nuclear speckles. PLoS One. 2011;6:e14500. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Altshuler D, Daly MJ, Lander ES. Genetic mapping in human disease. Science. 2008;322:881–888. doi: 10.1126/science.1156409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Larijani M, Frieder D, Sonbuchner TM, Bransteitter R, Goodman MF, Bouhassira EE, Scharff MD, Martin A. Methylation protects cytidines from AID-mediated deamination. Molecular Immunology. 2005;42:599–604. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bransteitter R, Pham P, Scharff MD, Goodman MF. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase deaminates deoxycytidine on single-stranded DNA but requires the action of RNase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4102–4107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cortazar D, Kunz C, Selfridge J, Lettieri T, Saito Y, MacDougall E, Wirz A, Schuermann D, Jacobs AL, Siegrist F, Steinacher R, Jiricny J, Bird A, Schar P. Embryonic lethal phenotype reveals a function of TDG in maintaining epigenetic stability. Nature. 2011;470:419–423. doi: 10.1038/nature09672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cortellino S, Xu J, Sannai M, Moore R, Caretti E, Cigliano A, Le Coz M, Devarajan K, Wessels A, Soprano D, Abramowitz LK, Bartolomei MS, Rambow F, Bassi MR, Bruno T, Fanciulli M, Renner C, Klein-Szanto AJ, Matsumoto Y, Kobi D, Davidson I, Alberti C, Larue L, Bellacosa A. Thymine DNA glycosylase is essential for active DNA demethylation by linked deamination-base excision repair. Cell. 2011;146:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iyer RR, Pluciennik A, Burdett V, Modrich PL. DNA mismatch repair: functions and mechanisms. Chem Rev. 2006;106:302–323. doi: 10.1021/cr0404794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kunkel TA, Erie DA. DNA mismatch repair. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:681–710. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kavli B, Otterlei M, Slupphaug G, Krokan HE. Uracil in DNA--general mutagen, but normal intermediate in acquired immunity. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wiesendanger M, Kneitz B, Edelmann W, Scharff MD. Somatic mutation in MSH3, MSH6, and MSH3/MSH6-deficient mice reveals a role for the MSH2-MSH6 heterodimer in modulating the base substitution pattern. J Exp Med. 2000;191:579–584. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Z, Scherer SJ, Ronai D, Iglesias-Ussel MD, Peled JU, Bardwell PD, Zhuang M, Lee K, Martin A, Edelmann W, Scharff MD. Examination of Msh6- and Msh3-deficient mice in class switching reveals overlapping and distinct roles of MutS homologues in antibody diversification. J Exp Med. 2004;200:47–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kirchmaier AL. Ub-family modifications at the replication fork: Regulating PCNA-interacting components. FEBS letters. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee KY, Myung K. PCNA modifications for regulation of post-replication repair pathways. Mol Cells. 2008;26:5–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roa S, Li Z, Peled JU, Zhao C, Edelmann W, Scharff MD. MSH2/MSH6 complex promotes error-free repair of AID-induced dU:G mispairs as well as error-prone hypermutation of A:T sites. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Langerak P, Nygren AO, Krijger PH, van den Berk PC, Jacobs H. A/T mutagenesis in hypermutated immunoglobulin genes strongly depends on PCNAK164 modification. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1989–1998. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoege C, Pfander B, Moldovan GL, Pyrowolakis G, Jentsch S. RAD6-dependent DNA repair is linked to modification of PCNA by ubiquitin and SUMO. Nature. 2002;419:135–141. doi: 10.1038/nature00991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garg P, Burgers PM. Ubiquitinated proliferating cell nuclear antigen activates translesion DNA polymerases eta and REV1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18361–18366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505949102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ulrich HD. Deubiquitinating PCNA: a downside to DNA damage tolerance. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:303–305. doi: 10.1038/ncb0406-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Delbos F, Aoufouchi S, Faili A, Weill JC, Reynaud CA. DNA polymerase eta is the sole contributor of A/T modifications during immunoglobulin gene hypermutation in the mouse. J Exp Med. 2007;204:17–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Martin A, Li Z, Lin D, Bardwell PD, Iglesias-Ussel MD, Edelmann W, Scharff MD. Msh2 ATPase Activity is Essential for Somatic Hypermutation at A-T Basepairs and for Efficient Class Switch Recombination. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1171–1178. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li Z, Zhao C, Iglesias-Ussel MD, Polonskaya Z, Zhuang M, Yang G, Luo Z, Edelmann W, Scharff MD. The mismatch repair protein Msh6 influences the in vivo AID targeting to the Ig locus. Immunity. 2006;24:393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lin DP, Wang Y, Scherer SJ, Clark AB, Yang K, Avdievich E, Jin B, Werling U, Parris T, Kurihara N, Umar A, Kucherlapati R, Lipkin M, Kunkel TA, Edelmann W. An Msh2 point mutation uncouples DNA mismatch repair and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:517–522. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peltomaki P. Lynch syndrome genes. Familial cancer. 2005;4:227–232. doi: 10.1007/s10689-004-7993-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peltomaki P, Vasen H. Mutations associated with HNPCC predisposition -- Update of ICG-HNPCC/INSiGHT mutation database. Dis Markers. 2004;20:269–276. doi: 10.1155/2004/305058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang G, Scherer SJ, Shell SS, Yang K, Kim M, Lipkin M, Kucherlapati R, Kolodner RD, Edelmann W. Dominant effects of an Msh6 missense mutation on DNA repair and cancer susceptibility. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ranjit S, Khair L, Linehan EK, Ucher AJ, Chakrabarti M, Schrader CE, Stavnezer J. AID Binds Cooperatively with UNG and Msh2-Msh6 to Ig Switch Regions Dependent upon the AID C Terminus. Journal of Immunology. 2011;187:2464–2475. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Steele EJ. Mechanism of somatic hypermutation: critical analysis of strand biased mutation signatures at A:T and G:C base pairs. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:305–320. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee SD, Alani E. Analysis of interactions between mismatch repair initiation factors and the replication processivity factor PCNA. J Mol Biol. 2006;355:175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Drotschmann K, Hall MC, Shcherbakova PV, Wang H, Erie DA, Brownewell FR, Kool ET, Kunkel TA. DNA binding properties of the yeast Msh2-Msh6 and Mlh1-Pms1 heterodimers. Biol Chem. 2002;383:969–975. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kadyrov FA, Dzantiev L, Constantin N, Modrich P. Endonucleolytic function of MutLalpha in human mismatch repair. Cell. 2006;126:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kadyrov FA, Holmes SF, Arana ME, Lukianova OA, O’Donnell M, Kunkel TA, Modrich P. Saccharomyces cerevisiae MutL{alpha} Is a Mismatch Repair Endonuclease. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37181–37190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707617200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schrader CE, Vardo J, Stavnezer J. Mlh1 can function in antibody class switch recombination independently of Msh2. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1377–1383. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schrader CE, Vardo J, Stavnezer J. Role for mismatch repair proteins Msh2, Mlh1, and Pms2 in immunoglobulin class switching shown by sequence analysis of recombination junctions. J Exp Med. 2002;195:367–373. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schrader CE, Edelmann W, Kucherlapati R, Stavnezer J. Reduced isotype switching in splenic B cells from mice deficient in mismatch repair enzymes. J Exp Med. 1999;190:323–330. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.3.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Peron S, Metin A, Gardes P, Alyanakian MA, Sheridan E, Kratz CP, Fischer A, Durandy A. Human PMS2 deficiency is associated with impaired immunoglobulin class switch recombination. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2465–2472. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li Z, Peled JU, Zhao C, Svetlanov A, Ronai D, Cohen PE, Scharff MD. A role for Mlh3 in somatic hypermutation. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:675–682. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu X, Tsai CY, Patam MB, Zan H, Chen JP, Lipkin SM, Casali P. A role for the MutL mismatch repair Mlh3 protein in immunoglobulin class switch DNA recombination and somatic hypermutation. J Immunol. 2006;176:5426–5437. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cannavo E, Gerrits B, Marra G, Schlapbach R, Jiricny J. Characterization of the interactome of the human MutL homologues MLH1, PMS1, and PMS2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2976–2986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609989200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang Y, Yuan F, Presnell SR, Tian K, Gao Y, Tomkinson AE, Gu L, Li GM. Reconstitution of 5′-directed human mismatch repair in a purified system. Cell. 2005;122:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Genschel J, Modrich P. Functions of MutLalpha, replication protein A (RPA), and HMGB1 in 5′-directed mismatch repair. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21536–21544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.021287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.van Oers JM, Roa S, Werling U, Liu Y, Genschel J, Hou H, Jr, Sellers RS, Modrich P, Scharff MD, Edelmann W. PMS2 endonuclease activity has distinct biological functions and is essential for genome maintenance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008589107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Poltoratsky V, Goodman MF, Scharff MD. Error Prone Candidates Vie for Somatic Mutation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:F27–F30. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.10.f27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tippin B, Goodman MF. A new class of errant DNA polymerases provides candidates for somatic hypermutation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:47–51. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Friedberg EC. Reversible monoubiquitination of PCNA: A novel slant on regulating translesion DNA synthesis. Mol Cell. 2006;22:150–152. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lehmann AR, Niimi A, Ogi T, Brown S, Sabbioneda S, Wing JF, Kannouche PL, Green CM. Translesion synthesis: Y-family polymerases and the polymerase switch. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:891–899. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Acharya N, Brahma A, Haracska L, Prakash L, Prakash S. Mutations in the ubiquitin binding UBZ motif of DNA polymerase eta do not impair its function in translesion synthesis during replication. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:7266–7272. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01196-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Haracska L, Unk I, Prakash L, Prakash S. Ubiquitylation of yeast proliferating cell nuclear antigen and its implications for translesion DNA synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6477–6482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510924103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Simpson LJ, Ross AL, Szuts D, Alviani CA, Oestergaard VH, Patel KJ, Sale JE. RAD18-independent ubiquitination of proliferating-cell nuclear antigen in the avian cell line DT40. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:927–932. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bachl J, Ertongur I, Jungnickel B. Involvement of Rad18 in somatic hypermutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12081–12086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605146103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Arakawa H, Moldovan GL, Saribasak H, Saribasak NN, Jentsch S, Buerstedde JM. A role for PCNA ubiquitination in immunoglobulin hypermutation. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Krijger PH, van den Berk PC, Wit N, Langerak P, Jansen JG, Reynaud CA, de Wind N, Jacobs H. PCNA ubiquitination-independent activation of polymerase eta during somatic hypermutation and DNA damage tolerance. DNA Repair. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Delbos F, De Smet A, Faili A, Aoufouchi S, Weill JC, Reynaud CA. Contribution of DNA polymerase eta to immunoglobulin gene hypermutation in the mouse. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1191–1196. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kleczkowska HE, Marra G, Lettieri T, Jiricny J. hMSH3 and hMSH6 interact with PCNA and colocalize with it to replication foci. Genes Dev. 2001;15:724–736. doi: 10.1101/gad.191201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Das-Bradoo S, Nguyen HD, Bielinsky AK. Damage-specific modification of PCNA. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3674–3679. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.18.13121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Das-Bradoo S, Nguyen HD, Wood JL, Ricke RM, Haworth JC, Bielinsky AK. Defects in DNA ligase I trigger PCNA ubiquitylation at Lys 107. Nature cell biology. 2010;12:74–79. doi: 10.1038/ncb2007. sup pp 71–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yang SY, Fugmann SD, Schatz DG. Control of gene conversion and somatic hypermutation by immunoglobulin promoter and enhancer sequences. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2919–2928. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ju Z, Volpi SA, Hassan R, Martinez N, Giannini SL, Gold T, Birshtein BK. Evidence for physical interaction between the immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region and the 3′ regulatory region. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35169–35178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705719200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Garrett FE, Emelyanov AV, Sepulveda MA, Flanagan P, Volpi S, Li F, Loukinov D, Eckhardt LA, Lobanenkov VV, Birshtein BK. Chromatin architecture near a potential 3′ end of the igh locus involves modular regulation of histone modifications during B-Cell development and in vivo occupancy at CTCF sites. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1511–1525. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.4.1511-1525.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Manis JP, van der Stoep N, Tian M, Ferrini R, Davidson L, Bottaro A, Alt FW. Class switching in B cells lacking 3′ immunoglobulin heavy chain enhancers. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1421–1431. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sleckman BP, Gorman JR, Alt FW. Accessibility control of antigen-receptor variable-region gene assembly: role of cis-acting elements. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:459–481. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bottaro A, Lansford R, Xu L, Zhang J, Rothman P, Alt FW. S region transcription per se promotes basal IgE class switch recombination but additional factors regulate the efficiency of the process. Embo J. 1994;13:665–674. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kuang FL, Luo Z, Scharff MD. H3 trimethyl K9 and H3 acetyl K9 chromatin modifications are associated with class switch recombination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:5288–5293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901368106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.McBride KM, Gazumyan A, Woo EM, Barreto VM, Robbiani DF, Chait BT, Nussenzweig MC. Regulation of hypermutation by activation-induced cytidine deaminase phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8798–8803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603272103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Barreto V, Reina-San-Martin B, Ramiro AR, McBride KM, Nussenzweig MC. C-Terminal Deletion of AID Uncouples Class Switch Recombination from Somatic Hypermutation and Gene Conversion. Mol Cell. 2003;12:501–508. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00309-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Unniraman S, Schatz DG. Strand-biased spreading of mutations during somatic hypermutation. Science. 2007;317:1227–1230. doi: 10.1126/science.1145065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bardwell PD, Martin A, Wong E, Li Z, Edelmann W, Scharff MD. Cutting Edge: The G-U Mismatch Glycosylase Methyl-CpG Binding Domain 4 Is Dispensable for Somatic Hypermutation and Class Switch Recombination. J Immunol. 2003;170:1620–1624. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Krijger PH, Langerak P, van den Berk PC, Jacobs H. Dependence of nucleotide substitutions on Ung2, Msh2, and PCNA-Ub during somatic hypermutation. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2603–2611. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Frieder D, Larijani M, Collins C, Shulman M, Martin A. The concerted action of Msh2 and UNG stimulates somatic hypermutation at A. T base pairs. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5148–5157. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00647-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Jiricny J. The multifaceted mismatch-repair system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:335–346. doi: 10.1038/nrm1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Erdeniz N, Nguyen M, Deschenes SM, Liskay RM. Mutations affecting a putative MutLalpha endonuclease motif impact multiple mismatch repair functions. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:1463–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Martomo SA, Yang WW, Wersto RP, Ohkumo T, Kondo Y, Yokoi M, Masutani C, Hanaoka F, Gearhart PJ. Different mutation signatures in DNA polymerase eta- and MSH6-deficient mice suggest separate roles in antibody diversification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8656–8661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501852102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Masuda K, Ouchida R, Hikida M, Kurosaki T, Yokoi M, Masutani C, Seki M, Wood RD, Hanaoka F, OWJ DNA polymerases eta and theta function in the same genetic pathway to generate mutations at A/T during somatic hypermutation of Ig genes. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:17397–17394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611849200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zeng X, Winter DB, Kasmer C, Kraemer KH, Lehmann AR, Gearhart PJ. DNA polymerase eta is an A-T mutator in somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin variable genes. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:537–541. doi: 10.1038/88740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.McDonald JP, Frank EG, Plosky BS, Rogozin IB, Masutani C, Hanaoka F, Woodgate R, Gearhart PJ. 129-derived strains of mice are deficient in DNA polymerase iota and have normal immunoglobulin hypermutation. J Exp Med. 2003;198:635–643. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Faili A, Aoufouchi S, Flatter E, Gueranger Q, Reynaud CA, Weill JC. Induction of somatic hypermutation in immunoglobulin genes is dependent on DNA polymerase iota. Nature. 2002;419:944–947. doi: 10.1038/nature01117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zan H, Komori A, Li Z, Cerrutti M, Flajnik MF, Diaz M, Casali P. The translesional polymerase zeta plays a major role in Ig and Bcl-6 somatic mutation. Immunity. 2001;14:643–653. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00142-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Diaz M, Verkoczy LK, Flajnik MF, KNR Decreased Frequency of Somatic Hypermutation and Impaired Affinity Maturation but Intact Germinal Center Formation in Mice Expressing Antisense RNA to DNA Polymerase zeta. J Immunol. 2001;167:327–335. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Casali P, Pal Z, Xu Z, Zan H. DNA repair in antibody somatic hypermutation. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Larson ED, Duquette ML, Cummings WJ, Streiff RJ, Maizels N. MutSalpha binds to and promotes synapsis of transcriptionally activated immunoglobulin switch regions. Curr Biol. 2005;15:470–474. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Rush JS, Fugmann SD, Schatz DG. Staggered AID-dependent DNA double strand breaks are the predominant DNA lesions targeted to S mu in Ig class switch recombination. Int Immunol. 2004;16:549–557. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Stavnezer J, Schrader CE. Mismatch repair converts AID-instigated nicks to double-strand breaks for antibody class-switch recombination. Trends Genet. 2006;22:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Chaudhuri J, Alt FW. Class-switch recombination: interplay of transcription, DNA deamination and DNA repair. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:541–552. doi: 10.1038/nri1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ramachandran S, Chahwan R, Nepal RM, Frieder D, Panier S, Roa S, Zaheen A, Durocher D, Scharff MD, Martin A. The RNF8/RNF168 ubiquitin ligase cascade facilitates class switch recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:809–814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913790107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Lieber MR. The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2010;79:181–211. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.093131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lee-Theilen M, Matthews AJ, Kelly D, Zheng S, Chaudhuri J. CtIP promotes microhomology-mediated alternative end joining during class-switch recombination. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2011;18:75–79. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Stavnezer J, Bjorkman A, Du L, Cagigi A, Pan-Hammarstrom Q. Mapping of switch recombination junctions, a tool for studying DNA repair pathways during immunoglobulin class switching. Adv Immunol. 2010;108:45–109. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380995-7.00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Duvvuri B, Duvvuri VR, Grigull J, Martin A, Pan-Hammarstrom Q, Wu GE, Larijani M. Altered spectrum of somatic hypermutation in common variable immunodeficiency disease characteristic of defective repair of mutations. Immunogenetics. 2011;63:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00251-010-0483-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Kracker S, Gardes P, Durandy A. Inherited defects of immunoglobulin class switch recombination. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;685:166–174. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6448-9_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Edelmann L, Edelmann W. Loss of DNA mismatch repair function and cancer predisposition in the mouse: animal models for human hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2004;129:91–99. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Chao EC, Lipkin SM. Molecular models for the tissue specificity of DNA mismatch repair-deficient carcinogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:840–852. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Peltomaki P. DNA mismatch repair and cancer. Mutat Res. 2001;488:77–85. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Mostoslavsky R, Alt FW, Bassing CH. Chromatin dynamics and locus accessibility in the immune system. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:603–606. doi: 10.1038/ni0703-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Jeevan-Raj BP, Robert I, Heyer V, Page A, Wang JH, Cammas F, Alt FW, Losson R, Reina-San-Martin B. Epigenetic tethering of AID to the donor switch region during immunoglobulin class switch recombination. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1649–1660. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Daniel JA, Santos MA, Wang Z, Zang C, Schwab KR, Jankovic M, Filsuf D, Chen H-T, Gazumyan A, Yamane A, Cho Y-W, Sun H-W, Ge K, Peng W, Nussenzweig MC, Casellas R, Dressler GR, Zhao K, Nussenzweig A. PTIP Promotes Chromatin Changes Critical for Immunoglobulin Class Switch Recombination. Science. 2010:science.1187942. doi: 10.1126/science.1187942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Chowdhury M, Forouhi O, Dayal S, McCloskey N, Gould HJ, Felsenfeld G, Fear DJ. Analysis of intergenic transcription and histone modification across the human immunoglobulin heavy-chain locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15872–15877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808462105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Wang L, Wuerffel R, Feldman S, Khamlichi AA, Kenter AL. S region sequence, RNA polymerase II, and histone modifications create chromatin accessibility during class switch recombination. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2009;206:1817–1830. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Wang L, Whang N, Wuerffel R, Kenter AL. AID-dependent histone acetylation is detected in immunoglobulin S regions. J Exp Med. 2006;203:215–226. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Rada C, Di Noia JM, Neuberger MS. Mismatch recognition and uracil excision provide complementary paths to both Ig switching and the A/T-focused phase of somatic mutation. Mol Cell. 2004;16:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Phung QH, Winter DB, Cranston A, Tarone RE, Bohr VA, Fishel R, Gearhart PJ. Increased hypermutation at G and C nucleotides in immunoglobulin variable genes from mice deficient in the MSH2 mismatch repair protein. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1745–1751. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.11.1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Ehrenstein MR, Neuberger MS. Deficiency in msh2 affects the efficiency and local sequence specificity of immunoglobulin class-switch recombination: parallels with somatic hypermutation. Embo J. 1999;18:3484–3490. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.12.3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Min IM, Schrader CE, Vardo J, Luby TM, D’Avirro N, Stavnezer J, Selsing E. The Smu tandem repeat region is critical for Ig isotype switching in the absence of Msh2. Immunity. 2003;19:515–524. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Rada C, Ehrenstein MR, Neuberger MS, Milstein C. Hot spot focusing of somatic hypermutation in MSH2-deficient mice suggests two stages of mutational targeting. Immunity. 1998;9:135–141. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80595-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Bardwell PD, Woo CJ, Wei K, Li Z, Martin A, Sack SZ, Parris T, Edelmann W, Scharff MD. Altered somatic hypermutation and reduced class-switch recombination in exonuclease 1-mutant mice. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:224–229. doi: 10.1038/ni1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Bentley DJ, Harrison C, Ketchen AM, Redhead NJ, Samuel K, Waterfall M, Ansell JD, Melton DW. DNA ligase I null mouse cells show normal DNA repair activity but altered DNA replication and reduced genome stability. Journal of cell science. 2002;115:1551–1561. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.7.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]