Abstract

Objectives

Commercial advertising and patient education have separate theoretical underpinnings, approaches, and practitioners. This paper aims to describe a collaboration between academic researchers and a marketing firm working to produce demographically targeted public service anouncements (PSAs) designed to enhance depression care-seeking in primary care.

Methods

An interdisciplinary group of academic researcherss contracted with a marketing firm in Rochester, NY to produce PSAs that would help patients with depressive symptoms engage more effectively with their primary care physicians (PCPs). The researchers brought perspectives derived from clinical experience and the social sciences and conducted empirical research using focus groups, conjoint analysis, and a population-based survey. Results were shared with the marketing firm, which produced four PSA variants targeted to gender and socioeconomic position.

Results

There was no simple, one-to-one relationship between research results and the form, content, or style of the PSAs. Instead, empirical findings served as a springboard for discussion and kept the creative process tethered to the experiences, attitudes, and opinions of actual patients. Reflecting research findings highlighting patients’ struggles to recognize, label, and disclose depressive symptoms, the marketing firm generated communication objectives that emphasized: a) educating the patient to consider and investigate the possibility of depression; b) creating the belief that the PCP is interested in discussing depression and capable of offering helpful treatment; and c) modelling different ways of communicating with physicians about depression. Before production, PSA prototypes were vetted with additional focus groups.

The winning prototype, “Faces,” involved a multi-ethnic montage of formerly depressed persons talking about how depression affected them and how they improved with treatment, punctuated by a physician who provided clinical information. A member of the academic team was present and consulted closely during production. Challenges included reconciling the marketing tradition of audience segmentation with the overall project goal of reaching as broad an audience as possible; integrating research findings across dimensions of words, images, music, and tone; and dealing with misunderstandings related to project scope and budget.

Conclusion

Mixed methods research can usefully inform PSAs that incorporate patient perspectives and are produced to professional standards. However, tensions between the academic and commercial worlds exist and must be addressed.

Practice implications

With certain caveats, implementation and dissemination researchers should consider opporutnities to join forces with marketing specialists. The results of such collaborations should be rigorously evaluated.

1. INTRODUCTION

Patients generally receive higher quality of care and achieve more positive clinical outcomes if they are well informed and involved in treatment.[1-3] How to best help patients achieve this state of activation, however, remains a central challenge to researchers and clinicians. Although various approaches to patient education and counseling have shown promise, few have attained the kind of consistent success enjoyed by direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) of prescription drugs.[4, 5] Research conducted in the United States shows that DTC advertisements stimulate patient requests during medical office visits.[6] Furthermore, when patients make requests for directly-advertised pharmaceuticals, physicians are likely to prescribe the requested medications even when ambivalent about the appropriateness of doing so.[7, 8]

1.1 The Powers and Perils of Direct-to-Consumer Advertising

What makes DTCA so powerful? Even skeptics (who are many) acknowledge the power of consumer-targeted ads to command and hold attention, motivate consumers, and prompt patients to make brand-specific prescription requests.[4, 9] These ads draw on theories of motivation emphasizing goal attainment, threat avoidance, and cognitive dissonance reduction.[10-12] They work because of compelling visuals, emotional appeals combined with varying amounts of factual evidence, persuasive print and audio messaging, solid production values, and message repetition.[10, 13, 14] Unfortunately from the public health perspective, such ads often sell product better than they convey balanced information that supports informed, shared clinical decision making.[15, 16] Specifically, DTCA may promote over-treatment of patients who want, but do not “need” the advertised medication.[17] For this reason, among others, direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription pharmaceuticals is banned in all Western nations except the United States and New Zealand.[18]

Though applied to a wide range of common conditions, DTCA and other marketing approaches seem particularly suitable for conditions that have ambiguous or subjective criteria for prescribing (e.g. neutropenia,[19] social anxiety[20]) or that are socially stigmatized (e.g., erectile dysfunction).[21, 22] Our work has focused on depression, which fulfills all three critera; it is common, under-recognized and under-treated, and associated with significant disability. Treatment for depression is usually effective, yet treatment criteria are somewhat subjective and ambiguous. Most patients first present with depression-related symptoms in primary care settings; yet primary care physicians (PCPs) frequently fail to recognize, treat and refer patients appropriately.[23] Physician education alone has proven insufficient to improve depression care, and systems interventions such as on-site mental health services have been inconsistently implemented. In addition, patient barriers to symptom recognition, acceptance of the need for treatment, and adherence to treatment remain formidable.[24] Thus there is a need for creative approaches to improving the recognition and treatment of depression in primary care.

Economic analyses correlating DTCA expenditures and antidepressant prescribing suggest that DTCA has a “class-expanding effect” in depression, meaning that depressed patients exposed to DTCA are more likely to receive an antidepressant medicine (though not necessarily the specific advertised drug).[25] In addition, direct experimental evidence using standardized patients (actors trained to portray a clinical role) indicates that when patients ask directly for advertised antidepressants, their likelihood of receiving an antidepressant prescription rises sharply; furthermore, this increase occurs whether or not depressive symptoms are clinically significant.[17]

Impressed with the promise of DTCA as a means of motivating patients but concerned by its potential to promote overtreatment, we sought to wed the power of DTCA with an approach that encourages information sharing and deliberation between patients and their physicians. In short, we wanted to preserve the verve of DTCA (ability to grab and hold patients’ attention) without the hype (high pressure sales techniques). Instead, our model envisions an informed patient and supportive primary care physician forming a productive partnership that facilitates reporting and exploration of distress followed by mutual consideration of treatment options. Further, we sought to surmount a limitation of traditional patient education and counseling paradigms – a sole focus on improving knowledge or generic communication skills may not take into account that patients often have difficulty recognizing, accepting, and discussing mental health conditions.[24]

In order to test the effectiveness of this approach, we created brief videos (“public service announcements,” or PSAs) on depression targeted to working-aged adults segmented along the lines of gender and socioeconomic status. The goal was to inform patients about depression while simultaneously persuading them to disclose their symptoms to PCPs and to consider a variety of treatment options.

1.2 Bridging Disciplines

The research and marketing teams came from different organizational cultures and embraced different perspectives. Given their academic and clinical backgrounds, the researchers’ conceptual framework was primarily informed by empirical studies of patients’ perceptions and experiences (including descriptive work conducted expressly for this project), clinical experience derived from practice and teaching, and clinical evidence on depression care. They borrowed from the fields of clinical medicine and communication and favored the use of messages and channels directly supported by previously published literature or new mixed methods research conducted expressly for this study.

The marketing team, while attentive to research, focused on gaining an intuitive understanding of how the customer thinks, feels, and responds. They emphasized using metaphor and creativity to generate concepts, language, and imagery that would capture and hold the attention of the audience. While the marketing team attended carefully to empirical data in the form of the recurring themes and natural language of focus group participants assembled for this project, they used these data to fuel the imagination of their creative team.

1.3 Overview

In the remainder of this article, we review the procedures employed to create the final PSAs, beginning with our approach to collection and interpretation of qualitative and quantitative data and ending with the PSA production process. The purpose of this descriptive exercise is to provide other academic researchers with guideposts by which they might embark on similar collaborations. We conclude by discussing the partnership’s interim successes, challenges, and lessons learned. The effects of the PSAs on depression care seeking and outcomes are currently being studied in an ongoing randomized trial.

2. METHODS

2.1 Team Composition and Background

The core academic team included two research-oriented primary care physicians, two research psychologists (one with an active clinical practice), a medical sociologist, and a health communication specialist. They were supported by a project manager at the University of California, Davis (UCD) and research assistants at the University of Rochester (NY) and the University of Texas (UT) in Austin, TX and by a private market research firm in Sacramento, CA. The marketing team was housed at Roberts Communications in Rochester and consisted of a project leader, a creative director, and an art director. The Roberts team was supported by a film director, film editor, and sound editor hired by contract.

2.2 Formative Research

The academic team conducted three sets of research activities (focus groups, a conjoint analysis, and a population-based survey) aimed at establishing the knowledge base necessary to reach, hold, and motivate the target audience. Focus groups were held in Sacramento, CA, Austin, TX, and Rochester, NY over an 8-month period in 2008. Methodological details related to these groups are available elsewhere.[26] Low and middle income target zip codes were identified within each of the 3 cities, and working age adults (25 to 64 years) were recruited to participate through advertisements, fliers, door-to-door canvassing, and direct mail. Working age adults (a group that includes both the currently employed and unemployed) were the population of interest because depression in this age group has significant economic and inter-generational consequences. Participants needed to have a personal history of depression or a first degree relative with depression. Guiding questions explored participants’ experiences with recognizing and coming to terms with depression, deciding whether to seek help, dealing with stigma and problems with access to care, and negotiating treatment with their primary care physician (if applicable). A total of 15 focus groups (5 in each city, with a total of 130 participants) were conducted by experienced focus group leaders. In addition, two additional focus groups with exclusively African American and Latino participants were held in Sacramento (n=14). Finally, to assess primary care physicians’ possible reactions to patients activated by PSAs, physician focus groups were conducted at the two sites with academic health centers: Sacramento (n=9 physician participants) and Rochester (n=7 physician participants). Discussions were transcribed and analyzed using standard approaches for qualitative data collection and analysis.[27, 28] The academic team extracted key messages related to depression recognition, causes, consequences, treatability and stigma for further testing in conjoint analysis and survey research (Table 1). More complete descriptions of focus group methods and results have been published elsewhere.[24, 26, 29]

Table 1.

Summary of Key Focus Group Findings

| Central Challenge | Specific Barriers to Care-Seeking for Depression |

|---|---|

| Recognizing symptoms as manifestations of a specific mental health condition (depression) |

|

| Forming an explanatory model that promotes treatment and care-seeking |

|

| Engaging in care for depression |

|

Conjoint analysis is a tool developed in marketing and used to assess consumer preferences for products and services typically employed to test the differential appeal and impact of different combinations of messages derived from focus group data.[30] Briefly, key findings from the focus groups were extracted, summarized in the form of short statements, and administered to 249 members of an online depression forum at DailyStrength.org. Adaptive conjoint analysis software was used to distill respondents’ preferences for specific messages within each of several content domains into “utilities,” numerical indicators of the strength of message appeal. Table 2 shows content domains and corresponding messages listed in descending order of utility (from highest to lowest).[31]

Table. 2.

Test messages sorted in order from most to least preferred, by attribute.

| Attribute | Test Messages Listed in Order of Utility |

|---|---|

|

Problems of Understanding Misunderstanding of the symptoms of depression (SYMPTOMS) |

“The major signs of depression are sadness and loss of interest lasting at least 2 weeks.” |

| “Depression affects people differently and can include sadness, hopelessness, loss of interest, changes in sleep or appetite, difficulty concentrating, and physical aches and pains.” |

|

| “For some people, depression feels like sadness and not wanting to spend time with people. For others, depression causes tiredness or pain.” |

|

| Depression is rare (so I probably don’t have it) (RARE) |

“Depression is very common.” |

| “About 1 in 10 patients you see in a typical doctor’s waiting room clinical depression.” |

|

| “At any given time, at least 5% to 10% of people in your neighborhood are living with depression.” |

|

| “Approximately 1 in 5 Americans will experience a serious bout of depression sometime in their lives.” |

|

|

Problems of

Communicating with One’s Physician |

“Depression is a serious condition.” |

| Depression is not a real medical condition, and thus does not need to be brought to my doctor’s attention. (MEDICAL) |

“Depression is just as much a medical condition as high blood pressure and diabetes.” |

| “Just like many other medical conditions, depression can run in families.” | |

| “Depression can result from an imbalance of chemical messengers in the brain.” | |

| I am shamed by my depression (SHAME) |

“Having depression is nothing to be ashamed of.” |

| “Having depression is not your fault.” | |

| “Depression can happen to anyone regardless of who they are.” | |

| “Depression treatment is between you, your family, and your doctor. Nobody else has to know.” |

|

| My depression will eventually go away on its own (and thus does not need to be treated). (PERSIST) |

“Depression does not usually just go on its own.” |

| “You would not expect high blood pressure to go away without treatment. Depression won’t just go away either.” |

|

| I don’t know how to raise the issue of my depression with my doctor. (TOPIC) |

“If you think you have depression, tell your doctor.” |

| “If you think you have depression, ask your doctor if medication or therapy might help.” |

|

| “If you are not feeling like yourself as your doctor, “Could I have depression?” | |

| My depression is a private matter and should be kept to myself (PRIVATE) |

“Having depression can seriously affect your life.” |

| “Having depression can seriously affect your and the lives of loved ones.” | |

| “When someone with depression suffers, their family and friends suffer too.” | |

|

Problems of Treatment

Acceptance |

“Depression can be treated with medication, counseling, or both.” |

| If I ask for help, my doctor will just want to give me drugs. (TREATMENTS) |

“There are many options for treating depression. Ask your doctor.” |

| “Depression can often be treated without medication.” | |

| If I ask for help, I may be given medications that have risky side effects (RISKS) |

“Side effect of antidepressants…usually go away with continued use.” |

| “All medications can have side effects, such as occasional stomach upset and restlessness, but antidepressants are generally well tolerated. |

|

| “Side effects from antidepressant medication, such as occasional stomach upset and restlessness, usually go away with continued use.” |

|

| “The newer antidepressants have fewer side effects.” | |

| If I ask for help, I may be given medications that don’t work. (EFFECTIVE) |

“Medications for depression help most patients.” |

| “Medications for depression help 70% of patients who take them.” | |

| “Finding the right antidepressant can take time, but an effective medication will be found for most patients.” |

To assess the generalizability of lessons derived from focus groups and the conjoint analysis, we partnered with a professional survey research group to conduct a follow-on telephone survey of 1054 participants in the 2008 California Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey.[32] Adults with a history of depression as well as adults with current PHQ-8 scores of 5 or greater were oversampled. (The PHQ-8 is equivalent to the PHQ-9 except for the absence of a single question on suicidality. A PHQ-9 score >=5 indicates a mild burden of depressive symptoms, though not necessarily a diagnosis of major depression.[33]) Survey questions focused on demographics, mental and physical health status, depression-related attitudes (stigma, toughness), perceived barriers to care-seeking, and treatment preferences. Among the key findings were that patients were uncertain that it is the doctor’s job to deal with psychological issues like depression and that less stigma was attached to the diagnosis of depression than to specific depression treatments (unpublished data not shown).

2.3 From Formative Research to Transmissible Knowledge

From the perspective of the research team, the formative research was intellectually engaging and academically productive. It was far from inevitable, however, that the findings could be synthesized in a useful way. In a series of conference calls, the research team discussed the formative findings and attempted to craft a summary that would provide actionable guidance to the marketers. Several questions fueled the discussion. First, could we encourage care-seeking without promoting unrealistic patient expectations? Depression is “treatable,” but complete remission of clinical symptoms is elusive even with optimal treatment.[34] Promises of a quick cure would not only be morally suspect, but could derail patient trust, underplay the vital importance of patience and perseverance in depression care, and tread perilously close to the line dividing fact from hyperbole. We wanted patients to talk with their primary care physicians about depressive symptoms; we wanted them to feel optimistic about their chances of recovery. But we did not want them to experience disappointment when their problems failed to clear up in the first weeks or months of treatment.

Second, could we engage and target segments of the population at risk without stereotyping? The research team was concerned with two main issues: (1) Could we transcend our own presuppositions about the manifestations of depression in different groups? (2) How could we use information about the “average” member of a group without assuming that all group members would share the same attitudes, beliefs, and preferences? Focus groups were stratified by gender and income (a proxy for socioeconomic status) in anticipation of developing PSAs targeted to low income men, middle income men, low income women, and middle income women. Certainly in our qualitative data, there were discernible differences in the ways these groups understood, articulated, and responded to psychological distress. For example, low income women tended to feel worthless and unworthy of the doctor’s attention, whereas middle income men tended to feel shame and the sense that generalist physicians were not interested in feelings. Nonetheless, there was considerable intra-group variation (only partially related to ethno-cultural differences) which could not be discounted, and we worried about pigeonholing patients in ways that might be false and counterproductive.

Third, how confident could we be that conclusions gleaned from studies of patients with a personal history of depression would reflect the experiences of patients who were confronting depression for the very first time? Although we asked focus group participants to reflect on the time before they were diagnosed, their memories were almost certainly colored by subsequent experiences of diagnosis and treatment. Given the difficulty of exploring barriers to depression care with those who do not even realize that they are depressed, we had to rely on the experiences of the previously diagnosed.

In the end, the academic group synthesized the findings of the three formative studies into a comprehensive summary document for review by the marketing firm. The research group anticipated the upcoming process of distillation, rendition, and production but lacked an understanding of how much work was ahead and the degree to which subtle nuances in presentation could affect the impact of the message.

2.4 Bringing Ideas to Market

Based on review of the summary document and participation in several conference calls, the marketing team transformed 30 pages of single-spaced text and tables into clear, simple, coherent messages. Using an approach that Roberts dubs “Customer Think®,” they sought to “get inside the head of” potential viewers, moving them from possible feelings of avoidance, stigma, passivity and shame to greater awareness of depressive symptoms; knowledge that doctors are there to help; ability to communicate feelings of distress to a physician; and confidence that effective treatments are available. As illustrated in Table 3, differences among our four targeted subgroups (lower and higher income men and women) were addressed by nuances of meaning and language use.

Table 3.

Current and desired attitudes among targeted patient subgroups, stratified by sex and income.

| Low Income Women | Low Income Men | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Attitude |

How they feel

toward: |

Current Attitude |

How they feel

toward: |

||

| Themselves | Worthless, low self esteem, denial, lazy | Themselves | Afraid, threatened, insecure, less of a man, crazy |

||

| Doctors | Do not feel worthy of a doctor’s attention in sharing their feelings |

Doctors | Doctors are judgmental | ||

| Treatment | Fear pills and would rather talk it over with a trusted confidant |

Treatment | Fear of psychiatry. “I don’t want to talk about it” |

||

| Desired Attitude | Themselves | You’re not alone and there is nothing to be ashamed of. It’s not okay to feel this way |

Desired Attitude | Themselves | “This is not my fault”, this is a medical problem and it is okay to ask for help |

| Doctors | Doctors do care how you feel | Doctors | Doctors will take this seriously because this is a medical problem like diabetes or high blood pressure |

||

| Treatment | There are options beyond pills; counseling, exercise, community support groups |

Treatment | Doctors can assist in making me feel better with a customized medical approach to my needs |

||

| Middle Income Women | Middle Income Men | ||||

| Current Attitude |

How they feel

toward: |

Current Attitude |

How they feel

toward: |

||

| Themselves | Unappreciated, guilty for feeling this way, embarassed, concerned about what others think |

Themselves | Shame, not successful, denial, behaving strangely |

||

| Doctors | Trust their doctors but not for psychiatry. They want someone to listen to them. |

Doctors | Doctors are not there to discuss feelings | ||

| Treatment | Fear pills and would rather talk it over with a trusted confidant |

Treatment | Fear of psychiatry. “I don’t want to talk about it” |

||

| Desired Attitude | Themselves | Take time to take care of yourself | Desired Attitude | Themselves | Empowered to make changes. “It’s okay to stop and ask for directions.” Successful people can be depressed. |

| Doctors | Doctors will listen | Doctors | Doctors will take this seriously because this is a medical problem like diabetes or high blood pressure |

||

| Treatment | Treatment is a process not just a pill; counseling, exercise, acupuncture |

Treatment | Doctors can assist in making me feel better with a customized medical approach to my needs |

||

Working from this broad framework, the marketing team developed six creative concepts:

○ “Nudge” -- a young, hip appearing character gets in the face of the viewer, urging him to seek treatment

○ “Twins” -- a person has a dialogue with his or her depressed twin self, showing before- and after-treatment images in parallel

○ “Inner Voices” -- a person is trapped by negative self-messages which he/she overcomes.

○ “Faces” -- a multiracial cast in which each person talks about how depression affected them and how they improved with treatment, punctuated by a physician who provides clinical information.

○ “Glass Box” -- a character appears caged in a glass box, watching the world -- and his/her family -- go by. Treatment releases him/her from the box.

○ “Life Tour” -- a content character looks back on a former (depressed) self, reflecting on how treatment allowed re-entry into the world

While elements of each concept incorporated formative research findings, the actual storylines embedded in each concept reflected a more intuitive process. The creative team at Roberts Communication transplanted ideas derived from the research into an audiovisual platform that would grab and hold the viewer’s attention. The academic researchers were, in general, awestruck by the creative power of the concepts presented. But at the same time, they struggled to imagine how each concept would play out before real patients seeing real physicians.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Tensions, Deliberations, and Resolution

The academic and marketing teams resolved most of their questions through a series of telephone discussions. Some questions were settled quickly, but others engendered vigorous debate. For example, in the interest of maximizing audience impact, the agency recommended an audience segmentation approach rather than a broadly splayed messaging campaign. In contrast, the research team was more concerned about crafting messages that would appeal to the broadest possible audience, while not stereotyping or ignoring vulnerable or minority populations. There were also questions of message content, narrative style, imagery and persuasion. For example, should the PSAs use “real people” with a story to tell or scripted actors? Should the framework be informational or dramatic? Should the ending be realistic or idealized? Should the end product have high production values or appear home-made? While theories from marketing and communication together with data from the empirical studies could provide guidance, their application to the details of media production was indirect at best. Instead, the academic and marketing teams found common ground through an iterative process of vetting and reacting. For example, early PSA prototypes contained language that “your doctor is absolutely interested in hearing about your depression.” The academic team was concerned that this message might over-sell the willingness and capacity of less psychosocially-oriented PCPs to respond to emotional distress.[35] Instead, the message was altered to convey that “your doctor wants to know about your depression but needs your help.” Language supporting this message was lifted from focus group transcripts and permuted to comport with a range of individual experiences and preferences: “This is hard, but I thought I should tell you.” “My sister – she thinks I might be depressed.” “Do you think this might be depression?” In addition, patients were urged to disclose depression-related concerns early in the visit, to avoid the “doorknob syndrome” in which critical issues are raised just as the doctor needs to move on to the next patient.[36] While maintaining a stance of mutual respect, the academic and marketing teams did have a few misunderstandings. Most were due to lack of knowledge of each others’ frames of reference and the logistics of producing media materials. The academic grant proposal, initially submitted some 3 years before, specified that the PSAs would be targeted to the explanatory models, cultural mores, and aesthetic values of four or more groups (as distinguished by gender, ethnicity and socioeconomic status); the academic team’s eventual vision was to produce 4 distinct videos, each with a completely different concept, structure and story (such as “Glass box” for middle-income women, “Life Tour” for middle-income men, etc.). Based on their own hard-won experience, the marketing team entered the project with a different set of assumptions. Knowing that the funds budgeted for the project (about $200,000 U.S.) would not be sufficient for creating 4 completely distinct PSA concepts, the marketing team proposed shaping a single concept (such as “Faces”) to the different target population segments. This misunderstanding represented a critical juncture in the partnership which was resolved by working on achieving the targeting goals through more subtle means: differences in the scripts to include the actual language used by the focus group participants, different actors and dress to appeal to the target audience, different facial expressions and tone of voice to capture different participants’ images of depressed and non-depressed states – even with PSAs that had the same underlying concept, structure and story. For example, we tried to have the PSAs incorporate our formative research suggesting that depressed men tend to express shame and fear whereas depressed women tend to express worthlessness and feeling unappreciated. Similarly, in the non-depressed states, we chose facial expressions that predominantly expressed happiness or strength, depending on the target audience.

3.2 Market Testing

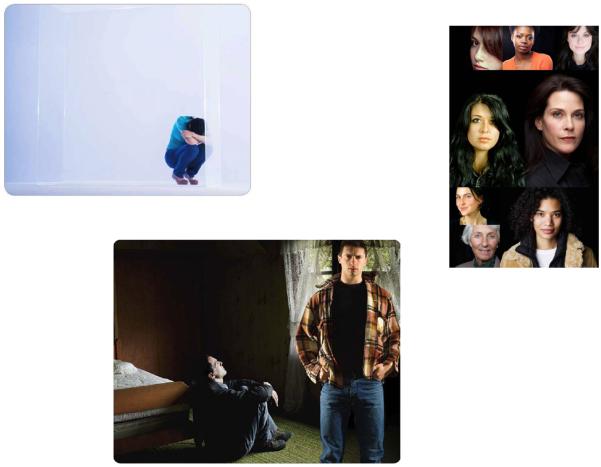

Following intensive deliberation, three creative concepts remained in the running: Glass Box, Life Tour, and Faces (Figure 1). Each had advantages. Glass Box was engaging, creative, and exquisitely tuned to the remarks of a number of female focus group participants, who recalled the core feeling of depression as separation, walling-off, and exclusion. Life Tour sent a strong signal of hope: no matter how bad things are now, they can get better with treatment. And Faces adeptly borrowed verbatim utterances from the focus groups to convey the many ways depression is experienced as well as the varied paths to recovery. To assess the appeal of each concept, we worked with a market research firm in Sacramento to convene 4 additional focus groups, each consisting (respectively) of 8-12 lower income men, middle income men, lower income women, and middle income women. All focus groups included at least one person of Asian, African-American, and Hispanic descent. The Roberts Communications Creative Director presented each concept in turn, reading from a script to illustrate how the dialog and visuals would coincide. A majority of members of three of the focus groups (both women’s groups as well as the lower income men) selected Faces as their strong favorite. For the middle income men, Faces ran second to Life Tour, but only because the actors selected for Faces were “too perfect.” Faces was anointed the winning concept.

Figure 1.

Visual motifs for PSA concept finalists: “Glass Box,” “Life Tour,” and “Faces”

3.3 Moving into Production

Production consisted of script-writing, casting, filming, editing and final assembly, including music. The script included nine segments. In three patient segments, each of four patients described aspects of their experience - recognition of symptoms, talking to the doctor and testimonials of success. The patient segments alternated with four doctor segments - information about depression, how to talk to your doctor, hope for recovery, and encouragement to take the next step. The beginning and end of the videos were brief clips of each patient, with physician voice-over and music. The patient lines were taken from verbatim transcripts from the focus groups.

Once the script was finalized, casting began. Two hundred actors were auditioned for the 2 physician roles and 16 patient roles. Filming took 2 entire days, with up to 10 takes of each segment for each actor, each with a different inflection, facial expression, lighting and, sometimes, clothing. Review of the first cuts took several days by the producer followed by two days with the entire team, viewing up to 20 versions of the same line uttered by different actors, to choose those that not only reflected the desired mood and message but also those who spoke most clearly to the targeted demographic group. Draft production took an additional two days, resulting in elimination of about 1/3 of the actors from consideration, and making subtle changes in timing, hue, volume of voices, transitions between scenes, and timing and choice of music. Final production involved another 2 days, mostly adjusting sound and lighting using sophisticated software.

Our efforts resulted in four PSAs, each approximately 2.5 minutes in length. Initial feedback was sought from a number of end-users after production, including participants at a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)-sponsored conference (“Targeted and Tailored Messages for Dealing with Depresison”, Sacramento, CA, April 8, 2010). In general, the feedback reassured us that that the PSAs spoke to the targeted groups, were considered both persuasive and informative, and maintained the viewer’s attention. The PSAs are now being evaluated in a randomized controlled trial in which patients with and without clinically significant depressive symptoms are randomly assigned to one of three interventions (targeted PSA as described here, tailored interactive multimedia computer program, or control). Outcomes of interest include disclosure of depressive symptoms and detection and treatment of clinically significant depression.

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

4.1 Discussion

While a full evaluation awaits completion of the randomized trial, our work over the past three years suggests that academics and marketers can work together successfully on projects designed to change health behaviors within clinical settings. We began the project convinced of the logic that melding clinical experience, communication theory, empirical evidence and marketing expertise could produce a powerful intervention capable of addressing the long-neglected problem of under-treatment of depression in primary care. But in charting a specific course from empirical research to the creative enterprise and back again, we had little experience or past research to guide us. Rather, we embarked on this collaboration based on three postulates.

First, we posited that PSAs produced by an academic-marketing collaborative would preserve the best of both worlds while suppressing the worst. With some notable exceptions (most prominently the anti-smoking campaign in California)[37], social marketing campaigns developed by academic researchers have been theoretically grounded, factually accurate, carefully conducted, and only inconsistently effective. One reason for the inconsistency is sporadic attention to the four pillars of social marketing: product (the health behavior itself), price (the “cost” of performing the behavior or giving up alternatives), place (the site where the desired behavior is to be performed), and promotion (the actual messages delivered).[38] But another reason for spotty outcomes is the sheer aridity of some academically-led campaigns. At the same time, direct-to-consumer marketing is attention-grabbing and widely assumed to work (why else would drug manufacturers have invested $4.2 billion in this strategy in 2005?) but has been attacked for exaggerating benefits, downplaying adverse effects, and appealing to emotions rather than logic. We engaged in this collaboration believing (but assuredly not knowing) that the academic tradition would provide the necessary intellectual ballast, while the creative impulses and technical virtuosity of the marketers would allow the campaign to captivate – and motivate – the intended audience.

Second, we posited that a satisfactory evidentiary basis for our depression campaign could be extracted from a small set of empirical studies. In planning the formative research designed to support the collaborative, the academic group decided to enlist a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods including focus groups, conjoint analysis, and survey methods. In the end, focus group data were the primary source of general themes as well as much of the specific language incorporated into the PSAs. Survey methods were used mainly as a check against the eventuality that focus group material was atypical or idiosyncratic. In obtaining data from diverse sources, we aimed to capitalize on the strengths of each method. Yet we harbored no illusions that our surveys were perfectly generalizable or that our focus groups accounted fully for critical contextual factors even within the narrow confines in which the data were collected.

Finally, we posited that the empirical findings could be seamlessly integrated into the PSAs in a manner reflecting their relative importance while maximizing the intervention’s capacity to capture the attention of the intended audience and motivate effective action. Our plan was structured much along the lines of the intervention mapping approach, in which development of program components proceeds from consultation with intended participants and implementers to creation of program scope and sequence, preparation of design documents, review of existing models, creation of program materials, and pretesting.[39] Nevertheless, there was no convincing way to weight the findings quantitatively; therefore we relied on consensus to move the process forward. Arguably, the broad, interdisciplinary make-up of the group enhanced the likelihood – but by no means guaranteed – that our choices were valid.

This project focused on making PSAs designed for viewing in physicians’ waiting rooms right before an office visit. We chose this approach, rather than constructing targeted messages for traditional mass media and the Internet, because we would be using the PSAs for a proof-of-concept study in which participants agreed to be a captive audience and to view the video material immediately prior to the physician visit. Use of mass media and the Internet, though, could greatly enhance the reach of an intervention, multiplying its public health impact.[40] Thus, regardless of the of the current trial results, more work will be needed to establish the optimal media for wider dissemination, and to further adapt the content and production format.

4.2 Conclusion and Practice Implications

In sum, this 3-year collaboration suggests that it is feasible to develop targeted PSAs that are not only empirically grounded but also captivating and persuasive. Furthermore, the process itself, despite the many challenges, was stimulating and fun. The research team enjoyed the opportunity to engage with marketing professionals in a highly creative enterprise; the marketers enjoyed the process of churning evidence into a compelling user experience. We believe such approaches can respect the ethical mandate to enhance patient autonomy through information, motivate patients using imagery and persuasion, and be deployed in primary care office settings. In sharing our experience, we hope to encourage others to undertake similar collaborations while being cognizant of the issues that can jeopardize success. Needless to say, the results of this and similar collaborations will require rigorous empirical study to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the resulting interventions.

Acknowledgements

Funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH079387 [Kravitz], K24 MH072756 [Kravitz], and K24 MH072712 [Duberstein]). Dr. Duberstein also received support from the Hendershot Research Funds, Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester. The authors wish to acknowledge Jennifer Becker, Dawn Case, and Ron King for research and administrative assistance and Rachel Spence for artistic direction.

Role of Funder Funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH079387). The funder played no role in the analysis or interpretation of data.

Contributor Information

Richard L. Kravitz, Department of Internal Medicine and Center for Healthcare Policy and Research, University of California at Davis, Sacramento, California, USA.

Ronald M. Epstein, Departments of Family Medicine, Psychiatry, Oncology and Nursing, and the Center for Communication and Disparities Research, University of Rochester, New York, USA.

Robert A. Bell, Departments of Communication and Public Health Sciences, University of California at Davis, Davis, California, USA.

Aaron B. Rochlen, Department of Psychology, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA.

Paul Duberstein, Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester, New York, USA.

Caroline H. Riby, Roberts Communications, Rochester, New York, USA and Syracuse University Newhouse School of Communications, Syracuse, New York, USA.

Anthony F. Caccamo, Roberts Communications, Rochester, New York, USA.

Christina K. Slee, Center for Healthcare Policy and Research, University of California at Davis, Sacramento, California, USA.

Camille S. Cipri, Center for Healthcare Policy and Research, University of California at Davis, Sacramento, California, USA.

Debora A. Paterniti, Departments of Internal Medicine and Sociology and Center for Healthcare Policy and Research, University of California at Davis, Sacramento, California, USA.

References

- 1.Cegala DJ, Street RL, Jr., Clinch CR. The impact of patient participation on physicians’ information provision during a primary care medical interview. Health Commun. 2007;21(2):177–85. doi: 10.1080/10410230701307824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenfield S, Kaplan S, Ware JE., Jr. Expanding patient involvement in care. Effects on patient outcomes. Annals of internal medicine. 1985 Apr;102(4):520–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-4-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE, Jr., Yano EM, Frank HJ. Patients’ participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 1988 Sep-Oct;3(5):448–57. doi: 10.1007/BF02595921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbody S, Wilson P, Watt I. Benefits and harms of direct to consumer advertising: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005 Aug;14(4):246–50. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.012781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilkes MS, Bell RA, Kravitz RL. Direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising: trends, impact, and implications. Health Aff (Millwood) 2000 Mar-Apr;19(2):110–28. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.2.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell RA, Kravitz RL, Wilkes MS. Direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising and the public. J Gen Intern Med. 1999 Nov;14(11):651–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.01049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mintzes B, Barer ML, Kravitz RL, Bassett K, Lexchin J, Kazanjian A, et al. How does direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) affect prescribing? A survey in primary care environments with and without legal DTCA. Cmaj. 2003 Sep 2;169(5):405–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mintzes B, Barer ML, Kravitz RL, Kazanjian A, Bassett K, Lexchin J, et al. Influence of direct to consumer pharmaceutical advertising and patients’ requests on prescribing decisions: two site cross sectional survey. BMJ. 2002 Feb 2;324(7332):278–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7332.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frosch DL, Grande D, Tarn DM, Kravitz RL. A decade of controversy: balancing policy with evidence in the regulation of prescription drug advertising. Am J Public Health. 2010 Jan;100(1):24–32. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frosch DL, Krueger PM, Hornik RC, Cronholm PF, Barg FK. Creating demand for prescription drugs: a content analysis of television direct-to-consumer advertising. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2007;5(1):6. doi: 10.1370/afm.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roth MS. Media and Message Effects on DTC Prescription Drug Print Advertising Awareness. Journal of Advertising Research. 2003;43:180–93. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harker M, Harker D. Direct-to-consumer-advertising of prescription medicines: a theoretical approach to understanding. Leadersh Health Serv (Bradf Engl) 2007;20(2):76–84. doi: 10.1108/17511870710745411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinto MB. On the nature and properties of appeals used in direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs. Psychological reports. 2000;86(2):597. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2000.86.2.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moons WG, Mackie DM, Garcia-Marques T. The impact of repetition-induced familiarity on agreement with weak and strong arguments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009 Jan;96(1):32–44. doi: 10.1037/a0013461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kravitz RL, Bell RA. Direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs: balancing benefits and risks, and a way forward. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007 Oct;82(4):360–2. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berndt ER. To inform or persuade? Direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs. N Engl J Med. 2005 Jan 27;352(4):325–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kravitz RL, Epstein RM, Feldman MD, Franz CE, Azari R, Wilkes MS, et al. Influence of patients’ requests for direct-to-consumer advertised antidepressants: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2005 Apr 27;293(16):1995–2002. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.16.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mintzes B, Morgan S, Wright JM. Twelve years’ experience with direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs in Canada: a cautionary tale. PloS one. 2009;4(5):e5699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abel GA, Lee SJ, Weeks JC. Direct-to-consumer advertising in oncology: a content analysis of print media. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Apr 1;25(10):1267–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.5968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Healy D. Have drug companies hyped social anxiety disorder to increase sales. Yes: marketing hinders discovery of long-term solutions. West J Med. 2001;175(6):364. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.175.6.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donohue JM, Berndt ER, Rosenthal M, Epstein AM, Frank RG. Effects of pharmaceutical promotion on adherence to the treatment guidelines for depression. Medical care. 2004 Dec;42(12):1176–85. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Block AE. Costs and benefits of direct-to-consumer advertising: the case of depression. Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25(6):511–21. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200725060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schulberg HC, Katon W, Simon GE, Rush AJ. Treating major depression in primary care practice: an update of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Practice Guidelines. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998 Dec;55(12):1121–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.12.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epstein RM, Duberstein PR, Feldman MD, Rochlen AB, Bell RA, Kravitz RL, et al. “I didn’t know what was wrong:” how people with undiagnosed depression recognize, name and explain their distress. J Gen Intern Med. 2010 Sep;25(9):954–61. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1367-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donohue JM, Berndt ER. Effects of direct-to-consumer advertising on medication choice: The case of antidepressants. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing. 2004;23(2):115–27. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kravitz RL, Paterniti DA, Epstein RM, Rochlen AB, Bell RA, Cipri C, et al. Relational barriers to depression help-seeking in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2011 Jun 4;82:207–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morgan D, Krueger RA. The Focus Group Kit. Sage Publications; Newberry Park: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2nd ed Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rochlen AB, Paterniti DA, Epstein RM, Duberstein P, Willeford L, Kravitz RL. Barriers in diagnosing and treating men with depression: a focus group report. Am J Mens Health. 2010 Jun;4(2):167–75. doi: 10.1177/1557988309335823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bell RA, Paterniti DA, Azari R, Duberstein PR, Epstein RM, Rochlen AB, et al. Encouraging patients with depressive symptoms to seek care: a mixed methods approach to message development. Patient Educ Couns. Feb;78(2):198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bell RA, Paterniti DA, Azari R, Duberstein PR, Epstein RM, Rochlen AB, et al. Encouraging patients with depressive symptoms to seek care: a mixed methods approach to message development. Patient Educ Couns. 2010 Feb;78(2):198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernandez YGE, Franks P, Jerant A, Bell RA, Kravitz RL. Depression treatment preferences of Hispanic individuals: exploring the influence of ethnicity, language, and explanatory models. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011 Jan-Feb;24(1):39–50. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.01.100118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Sep;16(9):606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warden D, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR. The STAR*D Project results: a comprehensive review of findings. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007 Dec;9(6):449–59. doi: 10.1007/s11920-007-0061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cepoiu M, McCusker J, Cole MG, Sewitch M, Belzile E, Ciampi A. Recognition of depression by non-psychiatric physicians—a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Journal of general internal medicine. 2008;23(1):25–36. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0428-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodondi PY, Maillefer J, Suardi F, Rodondi N, Cornuz J, Vannotti M. Physician Response to “By-the-Way” Syndrome in Primary Care. Journal of general internal medicine. 2009;24(6):739–41. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0980-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siegel M. Mass media antismoking campaigns: a powerful tool for health promotion. Annals of internal medicine. 1998;129(2):128. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-2-199807150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andreasen AR. Marketing social marketing in the social change marketplace. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing. 2002;21(1):3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH. Planning health promotion programs: An intervention mapping approach. Jossey-Bass; [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zatzick DF, Koepsell T, Rivara FP. Using target population specification, effect size, and reach to estimate and compare the population impact of two PTSD preventive interventions. Psychiatry. 2009 Winter;72(4):346–59. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2009.72.4.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Not recognizing or denying that something is the matter.

Not recognizing or denying that something is the matter. Not understanding that the symptoms might represent a problem.

Not understanding that the symptoms might represent a problem. Inability or unwillingness to accept the possibility of having depression.

Inability or unwillingness to accept the possibility of having depression. Conflict with self-image.

Conflict with self-image. Negative social support: shame, stigma, negative messages from others.

Negative social support: shame, stigma, negative messages from others. Interpreting distress as purely situational.

Interpreting distress as purely situational. Adopting characterologic explanations for symptoms

Adopting characterologic explanations for symptoms Holding rigid ideas about treatment options.

Holding rigid ideas about treatment options. Skepticism that primary care physicians (PCPs) are interested in and/or competent to provide care for depression.

Skepticism that primary care physicians (PCPs) are interested in and/or competent to provide care for depression. Lack of trust in PCP.

Lack of trust in PCP. Fear of being labeled “crazy” or being locked up.

Fear of being labeled “crazy” or being locked up. Concern that attention to emotional distress would distract focus from physical problems.

Concern that attention to emotional distress would distract focus from physical problems. Financial and logistic barriers to care.

Financial and logistic barriers to care. Desire for a quick fix.

Desire for a quick fix.