Abstract

Current drugs for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis are inadequate. No novel compound is in the pipeline. Since economic returns on developing a new drug for neglected disease, leishmaniasis is so low that therapeutic switching represents the only realistic strategy. It refers to “alternative drug use” discoveries which differ from the original intent of the drug. Amphotericin B, paromomycin, miltefosine and many other drugs are very successful examples of “new drugs from old”. This article reviews the discovery, growth and current status of these drugs and concluded that the potential of this approach (therapeutic switching) may use in the development of new antileishmanials in future also.

Keywords: Therapeutic switching, Leishmania chemotherapy, Miltefosine, Amphotericin B, Paromomycin

Introduction

Visceral leishmaniasis, also known as kala-azar, is a disseminated protozoan infection caused by the Leishmania donovani complex and transmitted via phlebotomine sandflies. It is nearly always fatal, if left untreated because the parasite migrates into the vital organs. The disease is associated with intermittent fever, weight loss, massive hepatosplenomegaly, and progressive deterioration of the host; hemorrhages and edemas may develop late in the course. Although the disease is endemic in more than 60 countries, with 200 million people at risk, 90% of the 500,000 cases every year happen in five countries: India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sudan, and Brazil (Griensven et al. 2010). Even VL was selected by the World Health Organization for elimination by 2015, along with other neglected tropical diseases (Maltezou 2010). Since there is no anti-leishmanial vaccine in clinical use, control of VL relies exclusively on chemotherapy but available anti-leishmanial therapy is inadequate and suffers from several drawbacks. The first-line therapy includes sodium stibogluconate (SbV) which has unfortunately developed resistance in some areas of Bihar, India where failure rates of up to 65% have been reported and the use of antimony has been abandoned (Sundar 2001). New compounds that have entered the clinical phase are known drugs resulting in the discovery of anti-leishmanial activity of paromomycin, amphotericin B, and serendipitous discovery of miltefosine. This approach is known as therapeutic switching, refers to alternative drug use discoveries which differ from the original intent of the drug. In all cases, the preclinical work was already done. Other known drugs that were identified and brought forward to the preclinical phase are the anti-leishmanial biphosphonates and the antifungal azoles (fluconazole and other azoles). All of these are very successful examples of “therapeutic switching” in leishmania chemotherapy. Therapeutic switching (also known as Piggy back chemotherapy, drug repurposing, drug re-profiling, drug repositioning, and drug re-tasking) have many advantages. Since, leishmaniasis infection is strongly linked with poverty and if the drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are known, drug repositioning “discoveries” are less costly and quicker than traditional discovery efforts (Ashburn and Thor 2004), which typically takes 10–15 years (Dimasi 2001) and upwards of $1 billion (Dimasi et al. 2003).

Paromomycin

Paromomycin, initially named aminosidine (Fig. 1a), was first isolated in the 1950s from filtrates of Streptomyces krestomuceticus. The spectrum of activity of paromomycin was found to encompass, like other aminoglycosides, most Gram-negative and many Gram-positive bacteria. The antibacterial action of paromomycin relates to its binding to the 30S ribosomal subunit, impairing protein synthesis. Unusually, paromomycin is also effective against some protozoa and cestodes and it is the only aminoglycoside with clinically important anti-leishmanial activity. Injectable paromomycin was extensively used as an antibiotic until Pharmacia (Milan, Italy) ceased production and marketing in the mid-1980s when cephalosporins and quinolones became popular antibiotics. Paromomycin in methylbenzethonium chloride ointment is used as a topical treatment for cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) (L. major) in Israel (Leshcutan; Teva, Patah Tiqva, Israel). Paromomycin is poorly absorbed after oral dosing and is still marketed as an oral treatment for amoebiasis and giardiasis and to decrease bacterial load in the gut in hepatic coma (Humatin; Parke-Davis, Morris Plains, NJ, USA). The anti-leishmanial properties of paromomycin were recognised by Kellina (1961) and were confirmed by Neal et al. (1968; 1995). Two ‘proof of concept’ studies, by the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) in Nairobi (Chunge et al. 1990) and the Hospital for Tropical Diseases in London, showed excellent therapeutic activity against VL (Scott et al. 1992).

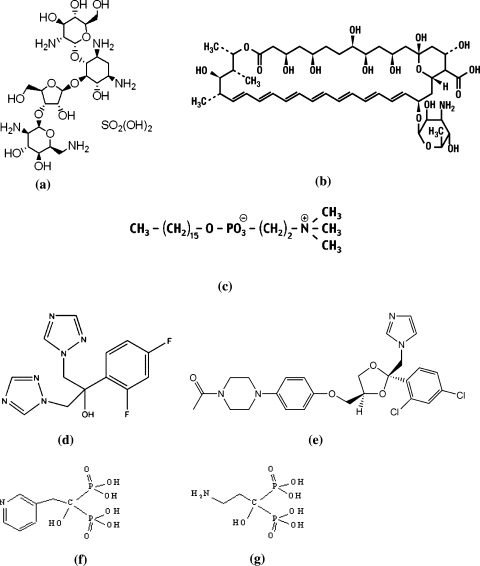

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of different antileishmanials. a Paraomomycin sulphate. b Amphotericine B. c Miltefosine. d Fluconazole. e Ketoconazole. f Residronate. g Pamidronate

The drug was being considered as a promising anti-leishmanial by the WHO/TDR. In 1991, a massive epidemic of VL occurred in western Upper Nile province in south Sudan. To combat this situation a humanitarian medical agency Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) decided to evaluate a short-course combination of paromomycin plus SSG, which was by then also being studied in India by the WHO/TDR (Thakur et al. 1992). Seaman et al. (1993) conducted a randomised controlled trial of combination of paromomycin sulphate 15 mg/kg/day plus SSG 20 mg/kg/day, i.m., daily for 17 days on 200 Sudanese VL patients and were found to be as effective as SSG monotherapy, with a lower mortality.

The leishmanicidal action of paromomycin is likely to be complex (Maarouf et al. 1997) L. donovani may be killed through inhibition of parasite metabolism and mitochondrial respiration. In vitro studies have shown that paromomycin can effectively kill both promastigotes and amastigotes (Neal and Croft 1984; Gebre-Hiwot et al. 1992; Neal et al. 1995). The 50% effective dose (ED50) of paromomycin against L. donovani amastigotes ranges from 10 to 50 μM. Data from mouse VL models and naturally infected dogs demonstrated that paromomycin is effective in vivo against L. donovani/L. infantum (Neal et al. 1995; Buffet et al. 1996; Gangneux et al. 1997; Poli et al. 1997; Vexenat et al. 1998; Williams et al. 1998).

Several studies have been conducted on paromomycin, alone or in combination with other drugs, as treatment for VL. It should be noted that paromomycin sulfate 15 mg/kg ≈paromomycin base 11 mg/kg. The most important study is done by Sundar and Olliaro (2007), which led to the licensing of paromomycin for VL in India. Neal et al. (1995) showed paromomycin and SSG to be synergistic in vitro and additive in a mouse model of VL. In a study of interactions between anti-leishmanial drugs, Seifert and Croft (2006) reported miltefosine and paromomycin to be additive in vitro and synergistic in the mouse VL model. Several clinical trials have shown the combination of paromomycin and SSG to be more efficacious than monotherapy with either drug (Chunge et al. 1990; Seaman et al. 1993; Thakur et al. 2000). The largest report of paromomycin plus SSG is detailed by Melaku et al. (2007).

In 2007, injectable paromomycin was licensed in India as an effective and well tolerated treatment for VL and was included in the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for the treatment of VL. The drug costs for a 21 day course for a 35 kg VL patient (€4.19) make this the cheapest treatment available. Currently, the drugs for neglected diseases initiative (DNDi) is conducting studies on paromomycin (as monotherapy and in combination) in VL in Africa, and the Institute of One World Health (iOWH) is conducting a Phase IV study in India. Little knowledge is present in reference to resistance of paromomycin. Further studies are needed to define the mechanisms of action drug resistance in Leishmania. Maarouf et al.(1998) studied on selected populations of promastigotes demonstrated that resistance was related to decreased drug uptake in L. donovani but due neither to enzymatic modifications nor to any mutation of the small-subunit rRNA gene in L. tropica (Fong et al. 1994). Clinically there has been only one report against cutaneous leishmaniasis, suggesting resistance could develop. Following a 60 day parenteral course for treatment of two L. aethiopica cases, isolates taken from relapse patients were three to fivefold less sensitive to the drug after treatment than isolates taken before treatment in an amastigote-macrophage assay (Teklemariam et al. 1994).

Because of the need to prevent the emergence of drug-resistant leishmaniasis in areas of human-to-human (anthroponotic) transmission (India and Africa), we consider that paromomycin should be used as part of combination therapy for VL, for example combined with SSG (where this is still effective) or liposomal amphotericin B (all regions). In addition, the distribution of paromomycin (like other drugs for leishmaniasis) should be well regulated, for example by being restricted to the public sector. These strategies should delay or prevent the emergence of resistance and ensure the longevity of paromomycin as a useful drug for VL.

Amphotericin B and its formulations

Amphotericin B is a fungal antibiotic. Conventional amphotericin B (fungizone®) is a macrolide polyene (Fig. 1b), characterized by hydrophilic polyhydroxyl and hydrophobic polyene aspects. It makes complexes with 24-substituted sterols, such as ergosterol in cell membrane, thus causing pores which alter ion balance and results in cell death (Roberts et al. 2003). Leishmania parasites have same sterol (ergosterol) in their cell wall. It is a highly effective and highly costly treatment option for VL which is used as a first-line drug in India, where resistance to pentavalent antimonials is common. The best amphotericin B regimen is 15 doses of 1 mg/kg on alternate days (Pape 2008). Oral amphotericin B is currently being assessed in phase I as well as undergoing (animal) efficacy studies for VL. The drug could be considered for phase II development by the end of 2009 (den Boer et al. 2009). Although this antibiotic has been widely used in the treatment of VL, there have been two small inconclusive studies on the emergence of amphotericin B resistance in L. infantum/HIV-infected cases in France. One study failed to find a change in sensitivity in promastigotes derived from isolates taken before and after the treatment of one patient (Durand et al. 1998). In contrast, a decrease in sensitivity was observed in isolates taken over several relapses from another patient (Di Giorgio et al. 1999). In a study, a micellar formulation of amphotericin B (AmB) solubilized with poloxamer 188 was evaluated against an AmB L. donovani-resistant line. Amastigotes showed 100 times less ED50 against this formulation than that of the control AmB formulation (Espuelas et al. 2000). With the increasing use of amphotericin B in lipid formulations that have longer half-lives, the possibility of resistance cannot be ignored. AmBisome accumulates in tissues and is only slowly released and excreted (Bekersky et al. 2002). This would theoretically increase the risk of resistant strains, but despite extensive use in VL, no in vivo resistance has yet been identified. This is likely to be due to the fact that parasites are killed very quickly by AmBisome, and thus get little opportunity to develop into resistant strains. As well as-VL patients treated with amphotericin B, care in a relatively well-equipped hospital for 30 days is required because of the risk of potentially serious side effects (especially renal toxicity). This makes it unfeasible for the treatment of patients. To make conventional amphotericin B, tolerable and preferable many formulations have been prepared.

Liposomal amphotericin B

The efficacy of the antibiotic amphotericin B has been improved by the development of less toxic lipid formulations (L-ampB). Although originally developed for the treatment of systemic mycoses, L-ampBs have been successfully exploited for VL with a high therapeutic index, short treatment courses and absence of side effects. It has an additional advantage of targeting the drug to infected macrophages of the liver and spleen. The liposomal amphotericin B formulation, AmBisome®, is registered treatment for visceral leishmaniasis (Meyerhoff 1999). It has superior cure rates, lower relapse rates, few side effects and much better compliance and convenience and health care providers but its use in VL endemic regions is limited by cost. However, now it is available in India at a WHO negotiated price of 10% of its original price and therefore has become affordable within the national elimination program. This is very significant because now ambisome can be considered as a first-line drug for VL (Sundar, unpublished work) A regimen of 20 mg/kg (total dose) of AmBisome was recommended based on previous experience in different parts of the world in treating patients. However, lower doses may be sufficient for the Indian subcontinent. In India, in a small study, a single dose of 5 mg/kg of AmBisome was effective in 91% of patients (den Boer et al. 2009).With recent preferential pricing offered by the manufacturer to patients in the public sector in East Africa, it is possible that AmBisome® could become economically feasible for treatment, even in resource—poor countries (DNDi annual report 2007–2008). Other commercial L-ampB formulations have been used for the treatment of VL.

Other commercial amphotericin B

Several other lipid forms have been evaluated in VL, such as Abelcet® (an amphotericin B lipid complex at the dose of 1–5 mg/kg per day) and Amphocil® (amphotericin B colloidal dispersion at the dose of 1 mg/kg of body weight). But none of these lipid formulations have yet been compared to AmBisome in a clinical trial. A promising oral form of amphotericin B is in an early stage of development by DNDi and partners being evaluated in phase I as well as undergoing (animal) efficacy studies for VL. Berman et al. 1998 also reported effectiveness of unilamellar liposome formulation of AmBisome, against VL in immunocompetent adults and children in Europe, Sudan, Kenya and India.

Miltefosine

It was discovered in Goettingen by Prof. Hansjörg Eibl from the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, and Prof. Clemens Unger from Clinic for Tumor Biology at the Albert Ludwig University in Freiburg. The active substance miltefosine—its chemical name being hexadecylphosphocholine (HPC), an analog of phosphatidylcholine (PC)—has a simple molecular structure (Fig. 1c). Croft et al. (Croft et al. 1987) in the late 1980s demonstrated that miltefosine which was initially developed as an anticancer agent, quickly and effectively eliminated Leishmania promastigotes from culture. Attention to this compound led to preclinical and clinical studies conducted for leishmaniasis. As a result, miltefosine has been registered for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in Germany and India, as well as for cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis in Colombia.

Identification of the anti-leishmanial potential of miltefosine started in the late 1980s (Croft et al. 2003). The development of miltefosine for leishmaniasis began with studies on the metabolism of phospholipids in L. donovani promastigotes in 1982 (Hermann and Gercken 1982), where it concluded that ethers of lysophospholipids (LPAs) such as 1-O-alkylglycerophosphocholine, 1-O-alkylglycerophosphoethanolamine and 1-O-hexadecyl-sn-glycerol were active and completely eliminated the parasites after less than 5 h of exposure to 25 μM. Miltefosine was then administered orally to BALB/c mice infected with L. donovani and L. infantum, and 95% parasite elimination was achieved with a dosage of 20 mg/kg bodyweight (Kuhlencord et al. 1992). The results stimulated the creation of a clinical program for visceral leishmaniasis in India, where the first phase I/II study was completed in 1997 (Sundar et al. 1998). In 2000 and 2001, it was demonstrated that miltefosine was effective in immunodeficient animals in contrast with the lack of activity of sodium stibogluconate (Murray 2000; Escobar et al. 2001).

Although analogs of lipophospholipids (LPAs) were developed as anticancer agents, these compounds also have strong antiparasitic activity in vitro (Singh and Sivakumarm 2004). Due to its chemical nature as a lecithin analog, LPAs interact with a variety of sub cellular structures and biochemical pathways. In mammalian cells, LPA induces programmed cell death associated with the inhibition of phosphocholine biosynthesis. Due to its molecular structure, LPAs have been intensively investigates as potential inhibitors of the enzymes involved in the synthesis, degradation and modification of the lipid membrane (Wieder et al. 1999). The metabolism of miltefosine was investigated in L. mexicana (Lux et al. 2000) and it was found that these compounds inhibit the specific alkyl-specific acyl CoA acyltransferase, a key enzyme for ether lipid remodeling, which may exert an effect on cellular growth of parasites. PCD in Leishmania due to miltefosine is characterized by a typical apoptotic phenomenon, such as cellular shrinking, DNA fragmentation and phosphatidyl serine exposition, with preservation of the integrity of the plasmatic membrane, which may cause programmed cell death in these organisms and can explain the selective antiparasitic effects of such compounds in vivo (Paris et al. 2004).

Miltefosine is only orally bioavailable anti-leishmanial drug but its efficacy is seriously compromised with teratogenicity and long half-life (approximately 150 h) which may facilitates the development of resistance. This drug should not be administered to women pregnant up to 2 months following drug discontinuation (Wadhone 2009). In India miltefosine is available over the counter, a fact that may expose this drug to misuse and emergence of resistance (Maltezou 2008). Experiences in this region have shown a decrease of efficacy from 97% in the phase III trial to 82% in phase IV trail (Bhattacharya et al. 2007). A case of a healthy patient with VL who relapsed 10 months after successful treatment with miltefosine for 28 days was reported recently (Pandey et al. 2009).

Resistance to miltefosine may emerge easily during treatment due to single point mutations. Decrease in drug accumulation is the common denominator in all miltefosine resistant Leishmania lines studied to date, and this could be achieved through decreased uptake, increased efflux, faster metabolism, or altered plasma membrane permeability; the first two mechanisms have been already described in models of experimental miltefosine resistance. Two proteins, miltefosine transporter LdMT and its specific beta subunit LdRos3, form part of the miltefosine translocation machinery at the parasite plasma membrane, and are required for miltefosine uptake (Maltezou 2010). Experimental mutations at LdMT or LdRos3 rendered the parasites remarkably less sensitive to miltefosine, and this resistance persisted in vivo. But the cross-resistance with other anti-leishmanials was not detected (Seifert et al. 2007). The overexpression of ABC transporters is another mechanism for acquisition of miltefosine resistance, through reduction of the drug intracellular accumulation (P′erez-Victoria et al. 2006; Castanys-Munoz et al. 2008). Recently, a novel flavonoid derivative was designed and it was shown that the use of suboptimal doses in order to overcome the overexpression of LtrMDR1 (a P-glucoprotein-like transporter belonging to the ATP binding cassette superfamily) was associated with a fourfold increase of intracellular miltefosine accumulation in the resistant Leishmania lines (P′erez-Victoria et al. 2006). Furthermore, modifications in lipid compositions of membranes and sterol biosynthesis have been detected in miltefosine resistant L. donovani promastigotes. Since membrane fluidity and permeability are influenced by lipid composition, their modification may affect drug-membrane interactions (Rakotomanga et al. 2005).

Azoles

Azoles are the one of the others that were also developed as anti-leishmanial drugs. Leishmania resemble fungi in synthesizing 24-substituted sterols such as ergosterol. Leishmania cell membrane synthesis involves the conversion of squalene to ergosterol. Azole exerts its effect by selectively inhibiting the cytochrome P450 enzyme 14 α-demethylase. The result is a loss of normal sterols and the accumulation of 14 α-methyl sterols within the cell (Ghannoum and Rice 1999). The efficacy of azoles against L. tropica was first reported by Berman (1981). Fluconazole, ketoconazole (Fig. 1d, e) and itraconazole have undergone several trials for CL and VL with equivocal results. In one controlled trial, ketoconazole was found to have some activity against L. mexicana, but not against L. braziliensis infections (Navin et al. 1992). Al-Abdely et al. in 1999 has also reported oral activity of posoconazole in a L. amazonensis experimental model. The results from in vitro studies that have investigated the intrinsic differences in sensitivity of Leishmania species to sterol biosynthesis inhibitors have produced contradictory data. In a comparative study on the sensitivity of promastigotes to ketoconazole, L. donovani, L. braziliensis, and L. amazonensis were found to be more sensitive than L. aethiopica, L. major, L. tropica, and L. mexicana (Beach et al. 1998). However, in contrast, Rangel et al. (1996) observed that L. braziliensis was relatively insensitive to ketoconazole and the bistriazole D087, whereas L. mexicana was sensitive to ketoconazole. Both sets of results differ from those of an earlier study using an amastigote-macrophage model, which showed that L. donovani was more sensitive to ketoconazole than L. mexicana or L. major (Berman 1981). The lack of concordance is probably due to different assay conditions, already shown to greatly influence antifungal activities, as well as the ability of amastigotes to salvage sterols, such as cholesterol, from host cell macrophages. This factor can reduce the sensitivity of this life cycle stage to azoles (Roberts et al. 2003). A number of clinical studies have suggested that these sterol biosynthesis inhibitors are more effective against L. major and L. mexicana infections than against L. donovani or L. braziliensis infections. One placebo-controlled trial on the treatment of CL showed that L. mexicana infections (89%) were more responsive than L. braziliensis infections (30%) to ketoconazole (Croft et al. 2006). Both ketoconazole and fluconazole have undergone evaluation in VL in India. However, despite reports of the former’s usefulness, their anti-leishmanial activity was not enough to induce clinical cure by themselves (Sundar and Chatterjee 2006) Fluconazole was used clinically due to its good oral absorption, minimal protein binding character, few adverse reactions and similar mode of action to that of amphotericin B (Jha 1998). Sundar et al. (1996) reported that fluconazole elicited clinical and parasitological cure in only 50% of cases when it was used at the dose of 6 mg/kg/day for 30 days, but these had relapses within 2 months. Fluconazole was used clinically in combination with allopurinol in the treatment of VL (Torrus et al. 1996) and this combination is used successfully by Colakoglu et al. (2006) in the patients of VL with renal failure. Against CL it has also shown promise (Mussi and Fernandes 2007). In a study in Saudi Arabia, fluconazole showed a cure rate of 79% in patients of CL caused by L. major (Alrajhi et al. 2002). Combination of ketoconazole and allopurinol was used clinically by Hueso et al. (1999) and Llorente et al. (2000) in the patients of VL treated with glucantime who developed abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and acute pancreatitis, respectively. Halim et al. (1993) also reported that a case of a renal transplant recipient who developed pancreatitis during stibogluconate treatment for VL was also successfully treated with this combination.

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates, for example risedronate and pamidronate (Fig. 1f, g), which are in widespread use in the treatment of bone disorders such as osteoporosis, have also shown activity against leishmaniasis in experimental models (Rodriguez et al. 2002; Yardley et al. 2002). These studies followed the characterization of acidocalcisomes in trypanosomatids with high polyphosphate and pyrophosphate content, and the hypothesis that bisphosphonates could interfere with pyrophosphate metabolism, although it is now thought that the prime target might be farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase—a key enzyme in isoprenoid biosynthesis (Martin et al. 2001). In Oldfeild et al. 2001 also described the use of farnesylpyrophosphate synthase inhibitors (bisphosphonates), as a new chemotherapeutic approach in leishmania chemotherapy. Paterson (2002) described the importance of pamidronate for the potential cure for leishmaniasis. Study of Ortiz-Gómez et al. (2006) stated the resistance towards the risedronate in L. major promastigotes by overproduction of farnesylpyrophosphate synthase enzyme under different conditions of exposure to this drug.

Conclusion

Leishmania infection is strongly linked with poverty. Risk for infection is mediated through poor housing conditions, environmental sanitation and lack of personal protective measures. Since, poverty is associated with poor nutrition and other infectious diseases; the risk that a person will progress to the more serious stage of infection is very high. Lack of access to healthcare causes delays in appropriate diagnosis and treatment and increases leishmaniasis morbidity and mortality (Homsi and Makdisi 2010).

Current research for VL has mainly been focused on the biological aspects of the parasite, an approach that is not of benefit to the many patients who need treatment today and not targeted to identifying promising new drugs. However, with the foundation of iOWH and DNDi, prospects have been improving. To register one new drug through new formulations of existing treatments and therapeutic switching is one of the long term objectives of DNDi. Oral amphotericin B is currently being assessed in Phase I as well as undergoing (animal) efficacy studies for VL and another oral formulation of amphotericin B (iCo) is currently in preclinical development. Sitamaquine (8-Aminoquinolone; analog of the antimalarial agent primaquine) has undergone phase II trials but issues remain about safety and relatively limited efficacy (under 90%).1

Drug screening programs for VL have received a financial boost; three highly effective new treatments for VL were identified through therapeutic switching (amphotericin B, paromomycin, and miltefosine) and have been licensed in the past 10 years. This approach has been one of the most important methods for the study and clinical introduction of novel drugs for leishmaniasis and can deliver new drugs more quickly and at lower cost as much of the development work has already been done. On reviewing the available treatments against VL, it is concluded that therapeutic switching is an efficient strategy for the therapy. It may provide new therapeutic regimen in the future also. This is CDRI communication no. 8067.

Footnotes

Contributor Information

Nishi Shakya, Email: nscdri@gmail.com.

Preeti Bajpai, Email: preeti2874@gmail.com.

Suman Gupta, Phone: +09415755899, FAX: +91-0522-2623938, Email: suman_gupta@cdri.res.in.

References

- Al-Abdely HM, Graybill JR, Loebenberg D, Melby PC. Efficacy of the triazole SCH 56592 against L. amazonensis and L. donovani in experimental murine cutaneous and visceral leishmaniases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2910–2914. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.12.2910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alrajhi AA, Ibrahim EA, Vol EB, Khairat M, Faris RM, Maguire JH. Fluconazole for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania major. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:891–895. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburn TT, Thor KB. Drug repositioning: identifying and developing new uses for existing drugs. Nat Rev. 2004;3:673–683. doi: 10.1038/nrd1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach DH, Goad LJ, Holz GG., Jr Effects of antimycotic azoles on growth and sterol biosynthesis of leishmania promastigotes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;31:149–162. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(88)90166-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekersky I, Fielding RM, Dressler DE, Lee JW, Buell DN, Walsh TJ. Pharmacokinetics, excretion, and mass balance of liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) and amphotericin B deoxycholate in humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:828–833. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.828-833.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman JD. Activity of imidazoles against Leishmania tropica in human macrophage cultures. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;30:566–569. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1981.30.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman JD, Goad LJ, Beach DH, Holz GG., Jr Effects of ketoconazole on sterol biosynthesis by L. mexicana amastigotes in murine macrophage tumor cells. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1981;20:85–92. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(86)90145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman JD, Badaro R, Thakur CP, Wasunna KM, Behbehani K, Davidson R, Kuzoe F, Pang L, Weerasuriya K, Bryceson AD. Efficacy and safety of liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) for visceral leishmaniasis in endemic developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76:25–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya SK, Sinha PK, Sundar S. Phase 4 trial of miltefosine for the treatment of Indian visceral leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(4):591–598. doi: 10.1086/519690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffet PA, Garin YJ, Sulahian A, Nassar N, Derouin F. Therapeutic effect of reference antileishmanial agents in murine visceral leishmaniasis due to Leishmania infantum. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1996;90:295–302. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1996.11813054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castanys-Munoz E, P′erez-Victoria JM, Gamarro F, Castanys S. Characterization of an ABCG-like transporter from the protozoan parasite Leishmania with a role in drug resistance and transbilayer lipid movement. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3573–3579. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00587-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chunge CN, Owate J, Pamba HO, Donno L. Treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in Kenya by aminosidine alone or combined with sodium stibogluconate. Trans Royal Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84:221–225. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90263-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colakoglu M, Yaylali G, Colakoglu NY, Yalmaz M. Successful treatment of visceral leishmania with fluconazole and allupurinol in a patient with renal failure. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38:208–210. doi: 10.1080/00365540500321405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft S, Neal R, Pendergast W, Chan JH. The activity of alkyl phosphocholines and related derivates against Leishmania donovani. Biochem Pharmacol. 1987;36:2633–2636. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(87)90543-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft SL, Seifert K, Duchene M. Antiprotozoal activities of phospholipid analogues. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;126:165–172. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(02)00283-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft SL, Seifert K, Yardley V. Current scenario of drug development for leishmaniasis. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:399–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boer ML, Alvar J, Davidson RN, Ritmeijer K, Balasegaram M. Developments in the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2009;14:395–410. doi: 10.1517/14728210903153862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giorgio C, Faraut-Gambarelli F, Imbert A, Minodier P, Gasquet M, Dumon H. Flow cytometric assessment of amphotericin B susceptibility in Leishmania infantum isolates from patients with visceral leishmaniasis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;44:71–76. doi: 10.1093/jac/44.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMasi JA. New drug development in the United States from 1963 to 1999. Clin Pharmacol Therapeut. 2001;69:286–296. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.115132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMasi JA, Hansen RW, Grabowski HG. The price of innovation: new estimates of drug development costs. J Health Econom. 2003;22:151–185. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand R, Paul M, Pratlong F, Rivollet D, Dubreuil-Lemaire DL, Houin R, Astier A, Deniau M. Leishmania infantum: lack of parasite resistance to amphotericin B in a clinically resistant visceral leishmaniasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2141–2143. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar P, Yardley V, Croft SL (2001) Activities of hexadecylphosphocholine (miltefosine), AmBisome, and sodium stibogluconate (pentostam) against Leishmania donovani in immunodeficient SCID mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:1872–1875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ghannoum MA, Rice LB (1999) Antifungal agents: mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev 12:501–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Espuelas S, Legrand P, Loiseau PM, Bories C, Barratt G, Irachel JM. In vitro reversion of amphotericin B resistance in Leishmania donovani by poloxamer 188. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2190–2192. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.8.2190-2192.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong D, Chan MM, Rodriguez R, Gately LJ, Berman JD, Grogl M. Paromomycin resistance in Leishmania tropica: lack of correlation with mutation in the small subunit ribosomal RNA gene. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:758–766. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangneux JP, Sulahian A, Garin YJ, Derouin F. Efficacy of aminosidine administered alone or in combination with meglumine antimoniate for the treatment of experimental visceral leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania infantum. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:287–289. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebre-Hiwot A, Tadesse G, Croft SL, Frommel D. An in vitro model for screening antileishmanial drugs, the human leukaemia monocyte cell line, THP-1. Acta Trop. 1992;51:237–245. doi: 10.1016/0001-706X(92)90042-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griensven J, Balasegaram M, Meheus F, Alvar J, Lynen L, Boelaert M. Combination therapy for visceral leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:184–194. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halim MA, Alfurayh O, Kalin ME, Dammas S, Al-Eisa A, Damanhouri G. Successful treatment of visceral leishmaniasis with allopurinol plus ketoconazole in a renal transplant recipient after the occurrence of pancreatitis due to stibogluconate. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:397–399. doi: 10.1093/clind/16.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann H, Gercken G. Metabolism of 1-O-[1′-14C]octadecyl-sn-glycerol in Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Ether lipid synthesis and degradation of the ether bond. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1982;5:65–76. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(82)90042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homsi Y, Makdisi G. Leishmaniasis: A forgotten disease among neglected people. Internet J Health. 2010;11:2. [Google Scholar]

- Hueso M, Bover J, Seron D, Gil-vernet S, Rufí G, Alsina J, Grinyó JM. The renal transplant patient with visceral leishmaniasis who could not tolerate meglumine antimoniate cure with ketoconazole and allopurinol. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:2941. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.12.2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha BB. Fluconazole in visceral leishmaniasis. Indian Pediatr. 1998;35:268–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellina OI. A study of experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis in white mice [in Russian] Med Parasitol (Mosk) 1961;30:684–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlencord A, Maniera T, Eibl H, Unger C. Hexadecylphosphocholine, oral treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1630–1634. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.8.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente S, Gimeno L, Navarro MJ, Moreno S, Rodriguez-Girones M. Therapy of visceral leishmaniasis in renal transplant recipients intolerant to pentavalent antimonials. Transplantation. 2000;70:800. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200009150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lux H, Heise N, Klenner T, Hart D, Opperdoes F. Ether-lipid (alkyl-phospholipid analog) metabolism and the mechanism of action of ether lipid analogs in Leishmania. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;111:1–14. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(00)00278-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maarouf M, Lawrence F, Brown S, Robert-Gero M. Biochemical alterations in paromomycin-treated Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Parasitol Res. 1997;83:198–202. doi: 10.1007/s004360050232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maarouf M, Adeline MT, Solignac M, Vautrin D, Robert-Gero M. Development and characterization of paromomycin-resistant Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Parasite. 1998;5:167–173. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1998052167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltezou HC. Visceral leishmaniasis: advances in treatment. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov. 2008;3:192–198. doi: 10.2174/157489108786242341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltezou HC. Drug resistance in visceral leishmaniasis. J Biomed Biotech. 2010;617521:8. doi: 10.1155/2010/617521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin MB, Grimley JS, Lewis JC, Heath HT, Bailey BN, Kendrick H, Yardley V et al (2001) Bisphosphonates inhibit the growth of Trypanosoma brucei, Trypanosoma cruzi, Leishmania donovani, Toxoplasma gondii, and Plasmodium falciparum: a potential route to chemotherapy. J Med Chem 44:909–916 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Melaku Y, Collin SM, Keus K, Gatluak F, Ritmeijer K, Davidson RN. Treatment of kala-azar in southern Sudan using a 17 day regimen of sodium stibogluconate combined with paromomycin, a retrospective comparison with 30 day sodium stibogluconate monotherapy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerhoff A. US food and drug administration approval of AmBisome (liposomal amphotericin B) for treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:42–48. doi: 10.1086/515085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray H. Suppression of post-treatment recurrence of experimental visceral leishmaniasis in T-cell-deficient mice by oral miltefosine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3235–3236. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.11.3235-3236.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mussi SV, Fernandes AP, Ferreira LAM. Comparative study of the efficacy of formulations containing fluconazole or paromomycin for topical treatment of infections by Leishmania (Leishmania) major and Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis. Parasitol Res. 2007;100:1221–1226. doi: 10.1007/s00436-006-0394-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navin TR, Arana BA, Arana FE, Berman JD, Chajon JF. Placebo-controlled clinical trial of sodium stibogluconate (pentostam) versus ketoconazole for treating cutaneous leishmaniasis in Guatemala. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:528–534. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.3.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal RA. The effect of antibiotics of the neomycin group on experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1968;62:54–62. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1968.11686529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal RA, Croft SL. An in vitro system for determining the activity of compounds against the intracellular amastigote form of Leishmania donovani. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1984;14:463–475. doi: 10.1093/jac/14.5.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal RA, Allen S, McCoy N, Olliaro P, Croft SL. The sensitivity of Leishmania species to aminosidine. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:577–584. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.5.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield E, Croft SL, Martin MB, Yardley V, Docampo R (2001) New approaches to chemotherapy using farnesylpyrophosphate synthase inhibitors: interscience conference on antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. Abstr Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother, University of Illinois, Urbana, Dec 16–19

- Ortiz-Gómez A, Jiménez C, Estévez AM, Carrero-Lérida J, Ruiz-Pérez LM, González-Pacanowska D. Farnesyl diphosphate synthase is a cytosolic enzyme in Leishmania major promastigotes and its overexpression confers resistance to risedronate. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:1057–1064. doi: 10.1128/EC.00034-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- P′erez-Victoria JM, Cortes-Selva F, Parodi-Talice A, et al. Combination of suboptimal doses of inhibitors targeting different domains of LtrMDR1 efficiently overcomes resistance of Leishmania spp. to miltefosine by inhibiting drug efflux. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:3102–3110. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00423-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey BD, Pandey K, Kaneko O, Yanagi T, Hirayama K. Relapse of visceral leishmaniasis after miltefosine treatment in a Nepalese patient. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:580–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape LP. Development of new antileishmanial drugs-current knowledge and future prospects. J Enzym Inhib Med Chem. 2008;23:708–718. doi: 10.1080/14756360802208137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris C, Loiseau P, Bories C, Breard J. Miltefosine induces apoptosis-like death in Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:852–859. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.3.852-859.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson R (2002) Pamidronate next on list as potential cure for leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis 2:515

- Pérez-Victoria FJ, Sanchez-Canete MP, Seifert K, et al. Mechanisms of experimental resistance of Leishmania to miltefosine: implications for clinical use. Drug Resist Updates. 2006;9:26–39. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poli A, Sozzi S, Guidi G, Bandinelli P, Mancianti F. Comparison of aminosidine (paromomycin) and sodium stibogluconate for treatment of canine leishmaniasis. Vet Parasitol. 1997;71:263–271. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(97)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakotomanga M, Saint-Pierre-Chazalet M, Loiseau PM. Alteration of fatty acid and sterol metabolism in miltefosine-resistant Leishmania donovani promastigotes and consequences for drug-membrane interactions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2677–2686. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.7.2677-2686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangel H, Dagger F, Hernandez A, Liendo A, Urbina JA (1996) Naturally azole-resistant Leishmania braziliensis promastigotes are rendered susceptible in the presence of terbinafine: comparative study with azole-susceptible Leishmania mexicana promastigotes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 40:2785–2791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Roberts CW, McLeod R, Rice DW, Ginger M, Chance ML, Goad LJ (2003) Fatty acid and sterol metabolism: potential antimicrobial targets in apicomplexan and trypanosomatid parasitic protozoa. Mol Biochem Parasitol 126:129–142 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez N, Bailey BN, Martin MB, Oldfield E, Urbina JA, Docampo R (2002) Radical cure of experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis by the bisphosphonate pamidronate. J Infect Dis 186:138–140 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Scott JA, Davidson RN, Moody AH, Grant HR, Felmingham D, Scott GM, et al. Aminosidine (paromomycin) in the treatment of leishmaniasis imported into the United Kingdom. Trans Royal Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992;86:617–619. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman J, Pryce D, Sondorp HE, Moody A, Bryceson AD, Davidson RN. Epidemic visceral leishmaniasis in Sudan, a randomized trial of aminosidine plus sodium stibogluconate versus sodium stibogluconate alone. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:715–720. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.3.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert K, Croft SL. In vitro and in vivo interactions between miltefosine and other antileishmanial drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:73–79. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.1.73-79.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert K, Pérez-Victoria FJ, Stettler M, Sanchez-Canete MP, Castanys S, Gamarro F, Croft SL. Inactivation of the miltefosine transporter, LdMT, causes miltefosine resistance that is conferred to the amastigote stage of Leishmania donovani and persists in vivo. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;30:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Sivakumarm R. Challenges and new discoveries in the treatment of leishmaniasis. J Infect Chemother. 2004;10:307–315. doi: 10.1007/s10156-004-0348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundar S. Drug resistance in Indian visceral leishmaniasis. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:849–854. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundar S, Chatterjee M. Visceral leishmaniasis—scurrent therapeutic modalities. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:345–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundar S, Olliaro PL. Miltefosine in the treatment of leishmaniasis, clinical evidence for informed clinical risk management. Therapeut Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3:733–740. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundar S, Singh VP, Agrawal NK, Gibbs DL, Murray HW. Treatment of kala-azar with oral fluconazole. Lancet. 1996;348:614. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)64828-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundar S, Rosenkaimer F, Makharia MK, Goyal AK, Mandal AK, Voss A, Hilgard P, Murray HW. Trial of miltefosine for visceral leishmaniasis. Lancet. 1998;352:1821–1823. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teklemariam S, Hiwot AG, Frommel D, Miko TK, Ganlov G, Bryceson A. Aminosidine and its combination with sodium stibogluconate in the treatment of diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania aethiopica. Trans Royal Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88:334–339. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(94)90106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur CP, Olliaro P, Gothoskar S, Bhowmick S, Choudhury BK, Prasad S, Kumar M, Verma BB. Treatment of visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) with aminosidine (paromomycin)-antimonial combinations, a pilot study in Bihar, India. Trans Royal Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992;86:615–616. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90150-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur CP, Kanyok TP, Pandey AK, Sinha GP, Zaniewski AE, Houlihan HH, Olliaro P. A prospective randomized, comparative, open-label trial of the safety and efficacy of paromomycin (aminosidine) plus sodium stibogluconate versus sodium stibogluconate alone for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. Trans Royal Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:429–431. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(00)90130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrus D, Boix V, Massa B, Portilla J, Perez-Mateo M. Fluconazole plus allopurinol in treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:1042–1043. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.5.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vexenat JA, Olliaro PL, Fonseca de Castro JA, Cavalcante R, Furtado Campos JH, Tavares JP, Miles MA. Clinical recovery and limited cure in canine visceral leishmaniasis treated with aminosidine (paromomycin) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:448–453. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadhone P, Maiti M, Agarwal R, Kamat V, Martin S, Saha B (2009) Miltefosine promotes IFN-γ-dominated anti-leishmanial immune response. J Immunol 182:7146–7154 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wieder T, Reutter W, Orfanos C, Geilen C. Mechanisms of action of phospholipid analogs as anticancer compounds. Prog Lipid Res. 1999;38:249–259. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7827(99)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D, Mullen AB, Baillie AJ, Carter KC. Comparison of the efficacy of free and non-ionic-surfactant vesicular formulations of paromomycin in a murine model of visceral leishmaniasis. J Pharmaceut Pharmacol. 1998;50:1351–1356. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1998.tb03358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yardley V, Khan AA, Martin MB, Slifer TR, Araujo FG, Moreno SN, Docampo R, Croft SL, Oldfield E. In vivo activity of the farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase inhibitors alendronate, pamidronate, and risedronate against Leishmania donovani and Toxoplasma gondii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:929. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.929-931.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]