Abstract

The transcriptional co-regulator SKI is a potent inhibitor of TGFβ-growth inhibitory signals. SKI binds to receptor-activated Smads in the nucleus, forming repressor complexes containing HDACs, mSin3, NCoR and other protein partners. Alternatively, SKI binds to activated Smads in the cytoplasm, preventing their nuclear translocation. SKI is necessary for anchorage-independent growth of melanoma cells in vitro, and most important, for human melanoma xenograft growth in vivo. We recently identified a novel role of SKI in TGFβ signaling. SKI promotes the switch of Smad3 from repressor of proliferation to activator of oncogenesis by facilitating phosphorylations in the linker domain. High levels of endogenous SKI are required by the tumor promoting trait of TGFβ to induce expression of the plasminogen-activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), sustained expression of C-Myc and for aborting upregulation of p21Waf-1. Here we discuss how SKI diversifies and amplifies its functions by associating with multiple protein partners and by promoting Smad3 linker phosphorylation(s) in response to TGFβ signaling in melanoma cells.

Keywords: melanoma, SKI protein complexes, Smad3 linker phosphorylations

SKI Promotes Oncogenic Smad3 Phosphorylations and Melanoma Tumor Growth in vivo

SKI is a transcriptional coregulator that activates or represses transcription in a manner that depends on its interactions with protein complexes containing either histone acetyltransferases or histone deacetylases, and on the cellular context. We have demonstrated previously that SKI is expressed in human melanoma tumors in parallel with disease progression.1 Recently, we demonstrated that downregulation of SKI in melanoma cells prevents both anchorage-independent growth, and more important, melanoma xenograft growth in vivo.2It has been proposed that Ski functions as a tumor suppressor in the mouse since ski−/− animals display increased susceptibility to carcinogenesis.3 However, re-expression of SKI in ski−/− mouse melanocytes showed that SKI neither promoted growth inhibition nor transformation to melanoma when compared to control cells lacking SKI (Chen D and Medrano EE, unpublished). Together these data suggests that SKI cooperates with other pathways to induce melanoma genesis and progression.

Although SKI can be downregulated by high levels of TGFβ and Arkadia,4,5 we and others demonstrated that SKI is prominently detected in human primary and metastatic melanoma tumors regardless of TGFβ levels present in the tumor microenvironment or secreted by the melanoma cells.1,6 Furthermore, treatment of serum-deprived melanoma cells with a low dose of TGFβ (8pM) was sufficient for inducing maximal, C-terminus phosphorylation of pSmad2C465/467 and pSmad3423/425 without inducing SKI degradation in a variety of human melanoma cell lines including UCD-Mel-N, A375, IIB-Mel-J, SK-Mel-93.3, SK-Mel-119 and others (ref. 2 and unpublished data). TGFβ inhibits the growth of most epithelial cell types and the neural crest-derived melanocytes. However, interactions of TGFβ with the Ras and JNK pathways are associated with oncogenesis and metastasis.7–9 The linker region of Smad3 (Smad3L) comprises four phosphorylations sites; Thr179, Ser204, Ser208 and Ser213. Mutations in the RAS signaling pathway and mitogenic activity result in activation of the extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) and phosphorylations in Smad3L at Thr179, Ser204 and Ser208.10 In a different cellular context, ERK was not responsible for Smad3L phosphorylations after TGFβ treatment.11

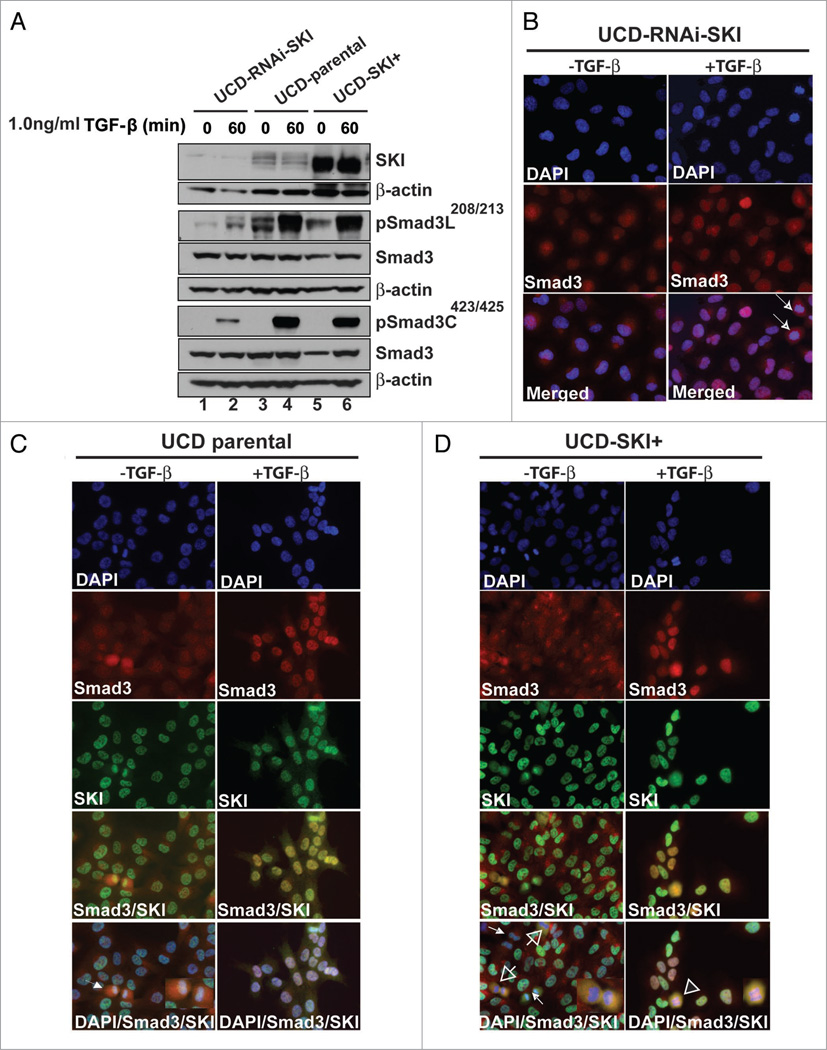

The UCD-Mel-N and A375 melanoma cell lines display the RASQ61R and BRAFV600E mutations respectively and consequent activation of ERK. We have found that the presence of endogenous SKI in UCD-Mel-N and A375 melanoma cells2 was sufficient for inducing maximal Smad3L208/213 phosphorylation after TGFβ-treatment of melanoma cells (Fig. 1A and reviewed in ref. 2). This conclusion is based on evidence showing that overexpression of SKI (UCD-SKI+) did not further increase pSmad3L (Fig. 1A and compare lane 4 with lane 6). In the presence of TGFβ, Smad3 displayed different degrees of co-localization with SKI (Fig. 1C and D). In contrast, pSmad3L was below detection in normal melanocytes, which display negligible levels of SKI.2 In turn, downregulation of SKI in UCD-Mel-N cells resulted in significantly attenuated pSmad3L compared to the parental cell line (Fig. 1A and compare lane 2 with lane 4). We also found that Thr179 is constitutively phosphorylated in UCD-Mel-N and A375 cells and that treatment with TGFβ did not further increase these levels (Lin Q and Medrano EE, data not shown). Phosphorylation of Thr179 appears to be cell-type and/or pathway-dependent as it is phosphorylated by TGFβ in mouse embryonic fibroblasts12 and HaCaT13 cells. In addition, phosphorylation of both the C-terminus and the linker region of Smad3 are required for activation of TGFβ pro-tumorigenic signals in human colorectal cancer.8,14 C-myc, a prototype of TGFβ regulated gene; can be downregulated by protein complexes containing C-terminus phosphorylated Smad3. This phosphorylation also results in de-repression of p15INK4b and p21Waf-1 (reviewed in ref. 15). We have found that SKI abrogates TGFβ-mediated C-myc downregulation, and upregulation of p21Waf-1. SKI also promotes sustained expression of PAI-1, a protein associated with tumor invasion.2 Presently, we can only speculate how SKI promotes Smad3L phosphorylations; it may be a direct consequence of its interaction with the MH2 domain and a fraction of the linker region of Smad3,16 and/or also require the cooperation of Ras/BRAF and JNK kinases. In fact, both pathways are notoriously activated in human melanoma.17

Figure 1.

Phosphorylations of Smad3L in melanoma are SKI-dependent. (A) A western blot shows that endogenous or overexpressed SKI in UCD-Mel-N promotes high levels of Smad3C and Smad3L phosphorylations after treatment with TGFβ for 1 hr. The western blot was probed with anti-SKI, anti-SmadCSer423/425, anti-Smad3LSer208/213 rabbit IgG affinity purified (Immuno-Biological laboratories, Gunma Japan), anti-Smad3 and anti-β-actin antibodies. The Abs were used at concentrations suggested by the manufacturers (reviewed in ref. 2). (B) Immunofluorescence analysis of Smad3 localization in melanoma cells with downregulated SKI (UCD-RNAi-SKI). (C and D) In the presence of SKI, Smad3 had a variable intensity under basal conditions; some cells showed intense nuclear staining while others displayed nucleo/cytoplasmic distribution, or a punctate, cytoplasmic localization. After treatment with TGFβ, Smad3 co-localized with SKI in a large number of the cells. Arrows indicate Smad3 immunoreactivity in metaphase cells. Note that SKI/Smad3 co-localization was prominent in anaphase (arrows) and late anaphase (arrowhead) regardless of any addition of TGFβ. The co-localization diminished or was undetectable in telophase when cytokinesis has begun (small white arrows).

SKI Diversifies and Amplifies its Functions by Associating with Multiple Protein Partners

The immunofluorescence studies described above were followed up by co-immunoprecipitation analyses. Using a Smad2/3 Ab, we showed that SKI and mSin3 are stable components of the Smad2/3 complex under basal conditions, whereas addition of TGFβ resulted in the association of the Smad2/3/SKI complex that included with mSin3, HDAC1 and RB (reviewed in ref. 2). Downregulation of SKI disrupted these complexes regardless of the presence or absence of TGFβ. It is likely that in these conditions the transcriptionally active Smad2/3 complex also included co-activators such as p300.

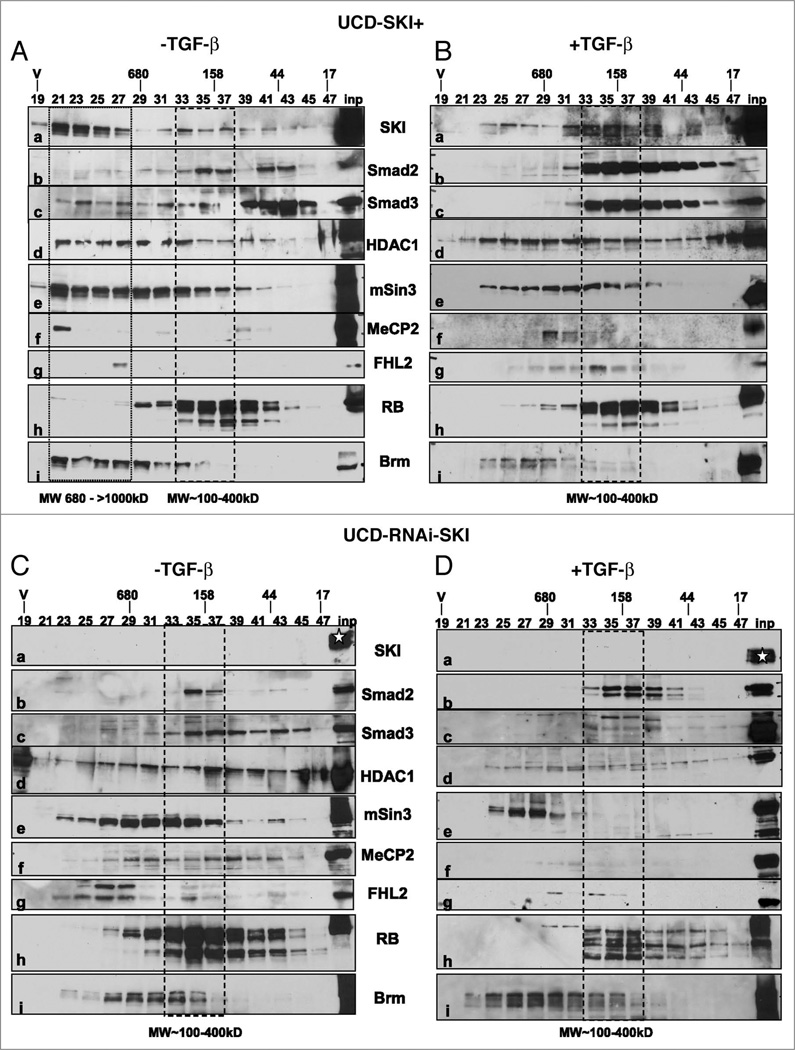

To learn more about the dynamics of Smad/SKI complexes, we also used gain- and loss-of function. In the absence of TGFβ, a size exclusion chromatography analysis showed that the bulk of SKI localized to different chromatographic fractions containing protein-protein complexes of high molecular weight masses (Fig. 2A, fractions 21–27, MW: 680 to >1,000 kD) in UCD-SKI+ cells. These results also suggest that the SKI/Smad3 partners identified by co-immunoprecipitation (reviewed in ref. 2) also contain yet to be identified protein partners. A small fraction of SKI was also found in intermediate-low molecular weight complexes (chromatographic fractions 33–37, MW: 100–400 kD) (Fig. 2A-a). Several known SKI-interacting proteins including Smad3, HDAC1, mSin3A, MeCP2 and FHL2 (reviewed in refs. 18 and 19) co-localized with SKI in high molecular weight containing complexes (Fig. 2, lanes b–g). Mouse Ski is required for the repressor activity of the N-CoR(SMRT) complex that contains mSin3 and his-tone deacetylases,20 whereas human SKI cooperates with FHL2 and p300 to activate Wnt-regulated promoters.21 Previous studies in HaCaT cells showed that under basal conditions, Smad3 but not Smad2, localizes to different gel filtration fractions including a distinct peak at a molecular weight of ~700 kD.22 Consistent with these data, our results showed that Smad3 is a component of high and low molecular fractions in UCD-SKI+ cells (Fig. 2Ac).

Figure 2.

SKI functions as a sensor and modifier of TGFβ. (A and B) Gel-filtration analysis and western blotting demonstrated that SKI moves from fractions containing high molecular weight to intermediate molecular weight complexes after TGFβ treatment. Preparation of cell extracts and gel filtration chromatography were performed following protocols described in ref. 37. (C and D) Downregulation of SKI changes the composition of basal and TGFβ-induced Smad2/3 complexes. Western blots of cell extracts fractionated by HPLC show the characteristic doublets of TGFβ-activated Smad2 and Smad3 that localize in intermediate mass complex(es). A star indicates position of input SKI from wild-type melanoma cells. Cells were lysed in a 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0) buffer containing 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF plus a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail set II (Calbiochem). The polyclonal anti-pSmad2L (S250–255) and anti-Smad3L (S208–213) antibodies,9 and monoclonal G8 anti-Ski Ab were used as described previously.38 The following commercial Abs were used following manufacturer’s instructions: polyclonal Abs Smad2 (Invitrogen, 51–1300); Smad3 (Invitrogen, 51–1500), polyclonal SKI Ab (Santa Cruz, sc-9140), HDAC1 (Santa Cruz, sc-7872), mSin3 (Santa Cruz, sc-994); MeCP2 (Millipore, 07–013), pSmad2C (Ser465–467) (Abcam, Ab5451), pSmad3C (Ser423–425) (Cell Signaling, Ab 3108) and monoclonal Abs RB (Lab Vision, Ab1-1F8) and Brm (Becton-Dickinson, BD 610389).

The SKI-Smad3 interactions are enhanced upon TGFβ stimulation.16 Treatment of UCD-SKI+ cells with TGFβ resulted in the shift of the high molecular weight SKI complexes to fractions co-migrating with Smad2/3, HDAC1, mSin3 and RB (fractions 33–37) (Fig. 2B, lanes a–e, and h). RNAi-mediated depletion of SKI established that the high molecular weight Smad3 complexes shifted to fractions containing lower molecular weight complexes (compare Fig. 2Ac with Cc), and also altered the distribution patterns of mSin3, MeCP2 and Brm (Fig. 2C, lanes e–g and j). Both Smad2 and Smad3 showed the characteristic shifts in their molecular masses that result from phosphorylations by the TGFβ receptor (Fig. 2D-b and c). Together, the results provide insights on the dynamic of Smad2/3 complexes and suggest that SKI functions as a sensor and modifier of TGFβ signaling.

Conclusions

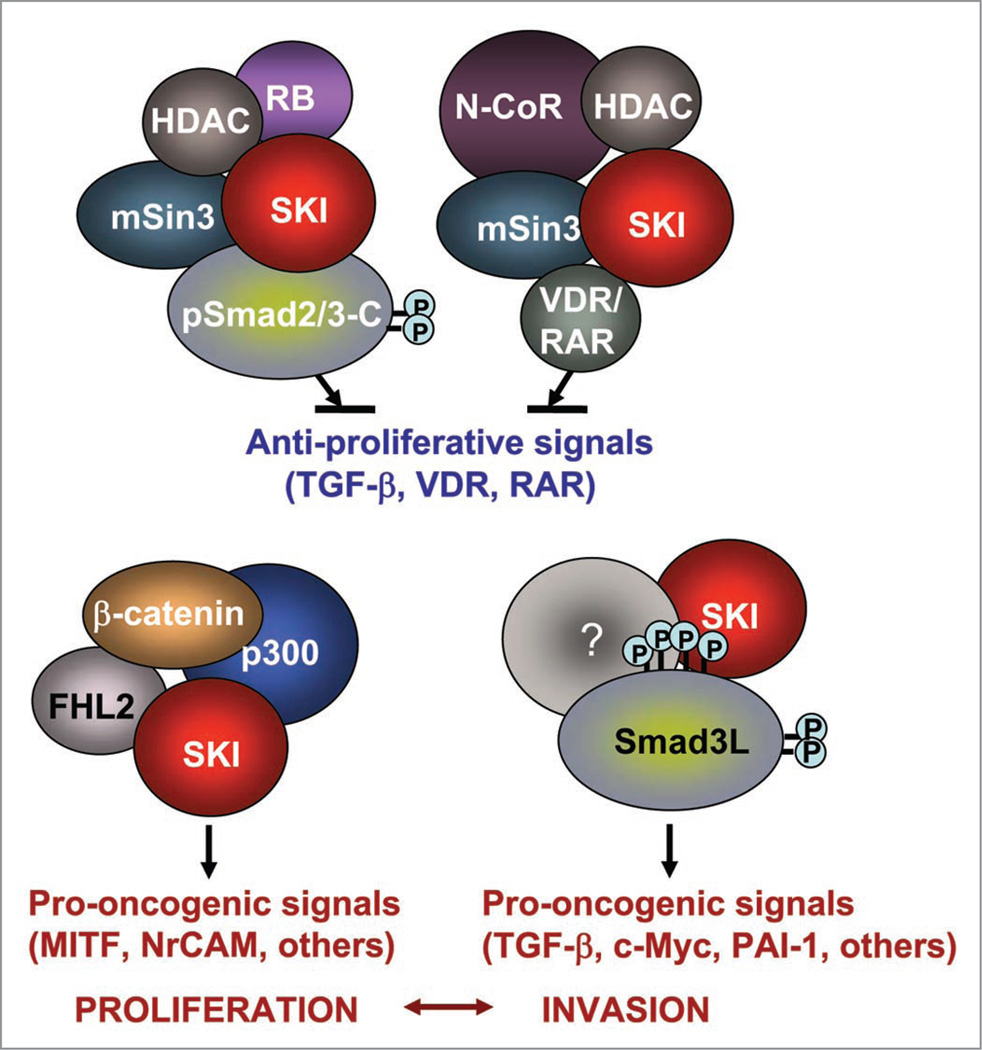

SKI functions a sensor and modifier of TGFβ signaling for melanoma promotion and progression. Recently, novel roles of SKI have been discovered by several groups. That includes inhibition of the retinoic acid receptor in acute myeloid leukemia,23 promotion of hematopoietic stem cell activity,24 promotion of tumor growth and angiogenesis in diffuse-type gastric carcinoma cells25 and association and cooperation with Mel1 (MDS1/EVI1-like gene) to inhibit TGFβ signaling in gastric cancer cells.26 SKI also displays dual activities as tumor promoter and suppressor of metastasis in pancreatic cells,27 and promotes early colorectal cancer.28 To this partial list, we can add that SKI is required for both human melanoma xenograft growth and for promotion of Smad3 linker phosphorylations that participate in the switch of TGFβ from tumor suppressor to oncogenic functions.2 SKI has paradoxical, poorly understood roles in some cancer cell lines. For example, SKI does not affect tumor growth but increases metastasis of breast and lung xenografts.4 In contrast, SKI is required for tumor growth in vitro and in vivo but reduces metastasis of pancreatic cancer cell lines.29 We propose that melanoma tumors respond to TGFβ in a SKI-dependent manner. In non-invasive primary melanoma tumors exhibiting low number of SKI-positive cells, SKI may essentially promote proliferation via association with FHL2 and activation of the β-catenin pathway,21 whereas the SKI-negative cells may be still be susceptible to inhibition by TGFβ. As the majority of the tumor cells become SKI-positive, interactions of SKI with the TGFβ pathway may switch melanoma cells to the invasive phenotype (Fig. 3). This hypothesis is supported by recent data from the Hoek group showing that melanoma tumors can switch from proliferative to invasive phenotypes that are characterized by lower rates of proliferation, high motility and resistance to TGFβ.30

Figure 3.

The multiple functions of SKI in melanoma are mediated by protein-protein interactions and protein-partner phosphorylations (Smad3L phosphorylations). See text for an explanation of the model presented in this figure.

Our immunofluorescence studies also highlight the heterogeneity of the TGFβ response and Smad3/SKI localization when analyzed in single cells (Fig. 1C and D). In this regard, some cells that exhibit intense staining with a SKI Ab, displayed a weak staining for Smad3 and visceversa. Also, intense brightness of both SKI and Smad3 was observed in late anaphase/telophase cells, and coincided with their co-localization (Fig. 1C and D). The strong association of SKI with Smad3 in mitosis has not been identified before, but is supported by independent data showing that Smad3 is activated in mitotic cells,31 and that SKI levels peak in mitosis. 32 Further studies are needed to understand the biological significance of this phenomenon.

We don’t yet know whether additional SKI functions may also be important for melanoma progression. For example, SKI can negatively regulate vitamin D-mediated transcription by directly interacting with the vitamin D receptor (VDR).33 SKI also inhibits retinoic acid receptor (RAR) signaling by forming stable complexes with HDAC3 on RAR-target genes.34 Considering the renewed interest for both RAR and VDR in melanoma prognosis and progression,35,36 it would be instructive to know if SKI has any role in these pathways.

Finally, the wealth of data already available suggest that targeting SKI by small molecule inhibitors should be included in the “to do” list of novel anti-melanoma therapies.

Acknowledgements

We thank Monique Aumailley for the generous gift of the FHL2 Ab. E.E.M. is supported by NIH grants R01 CA084282, R01 AG032135 and RC2 AG036562, and by a Baylor/M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Multidisciplinary Research Program. N.A.T. is supported by NIH grants RO1 AG20752, RO1 CA100070 and RO1 GM55188.

References

- 1.Reed JA, Bales E, Xu W, Okan NA, Bandyopadhyay D, Medrano EE. Cytoplasmic localization of the oncogenic protein ski in human cutaneous melanomas in vivo: functional implications for transforming growth factor Beta signaling. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8074–8078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen D, Lin Q, Box N, Roop D, Ishii S, Matsuzaki K, et al. SKI knockdown inhibits human melanoma tumor growth in vivo. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009;22:761–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2009.00603.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shinagawa T, Nomura T, Colmenares C, Ohira M, Nakagawara A, Ishii S. Increased susceptibility to tumorigenesis of ski-deficient heterozygous mice. Oncogene. 2001;20:8100–8108. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le SE, Zhu Q, Wang L, Bandyopadhyay A, Javelaud D, Mauviel A, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta suppresses the ability of Ski to inhibit tumor metastasis by inducing its degradation. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3277–3285. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagano Y, Mavrakis KJ, Lee KL, Fujii T, Koinuma D, Sase H, et al. Arkadia induces degradation of SnoN and c-Ski to enhance transforming growth factor-beta signaling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20492–20501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701294200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boone B, Haspeslagh M, Brochez L. Clinical significance of the expression of c-Ski and SnoN, possible mediators in TGFbeta resistance, in primary cutaneous melanoma. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;53:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuzaki K. Smad3 phosphoisoform-mediated signaling during sporadic human colorectal carcinogenesis. Histol Histopathol. 2006;21:645–662. doi: 10.14670/HH-21.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuzaki K, Kitano C, Murata M, Sekimoto G, Yoshida K, Uemura Y, et al. Smad2 and Smad3 phosphorylated at both linker and COOH-terminal regions transmit malignant TGFbeta signal in later stages of human colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5321–5330. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sekimoto G, Matsuzaki K, Yoshida K, Mori S, Murata M, Seki T, et al. Reversible Smad-Dependent Signaling between Tumor Suppression and Oncogenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5090–5096. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wrighton KH, Feng XH. To (TGF)beta or not to (TGF)beta: fine-tuning of Smad signaling via post-translational modifications. Cell Signal. 2008;20:1579–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang G, Matsuura I, He D, Liu F. Transforming growth factor-β-inducible phosphorylation of Smad3. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9663–9673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809281200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Millet C, Yamashita M, Heller M, Yu LR, Veenstra TD, Zhang YE. A negative feedback control of transforming growth factor-beta signaling by glycogen synthase kinase 3-mediated Smad3 linker phosphorylation at Ser-204. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19808–19816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.016667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao S, Alarcon C, Sapkota G, Rahman S, Chen PY, Goerner N, et al. Ubiquitin ligase Nedd4L targets activated Smad2/3 to limit TGFbeta signaling. Mol Cell. 2009;36:457–468. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hachimine D, Uchida K, Asada M, Nishio A, Kawamata S, Sekimoto G, et al. Involvement of Smad3 phosphoisoform-mediated signaling in the development of colonic cancer in IL-10-deficient mice. Int J Oncol. 2008;32:1221–1526. doi: 10.3892/ijo_32_6_1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin X, Chen Ye-Guang, Feng Xin-Hua . Transcriptional Control via Smads. In: Derynck R, Miyazono K, editors. The TGFβ family. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2008. pp. 287–332. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu W, Angelis K, Danielpour D, Haddad MM, Bischof O, Campisi J, et al. Ski acts as a co-repressor with Smad2 and Smad3 to regulate the response to type beta transforming growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5924–5929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090097797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez-Bergami P, Huang C, Goydos JS, Yip D, Bar-Eli M, Herlyn M, et al. Rewired ERK-JNK Signaling Pathways in Melanoma. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:447–460. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medrano EE. Repression of TGFbeta signaling by the oncogenic protein SKI in human melanomas: consequences for proliferation, survival and metastasis. Oncogene. 2003;22:3123–3129. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reed JA, Lin Q, Chen D, Mian IS, Medrano EE. SKI pathways inducing progression of human melanoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2005;24:265–272. doi: 10.1007/s10555-005-1576-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nomura T, Khan MM, Kaul SC, Dong HD, Wadhwa R, Colmenares C, et al. Ski is a component of the his-tone deacetylase complex required for transcriptional repression by Mad and thyroid hormone receptor. Genes Dev. 1999;13:412–423. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.4.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen D, Xu W, Bales E, Colmenares C, Conacci-Sorrell M, Ishii S, et al. SKI activates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in human melanoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6626–6634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jayaraman L, Massague J. Distinct oligomeric states of SMAD proteins in the transforming growth factor-beta pathway. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40710–40717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005799200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ritter M, Kattmann D, Teichler S, Hartmann O, Samuelsson MK, Burchert A, et al. Inhibition of retinoic acid receptor signaling by Ski in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2006;20:437–443. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deneault E, Cellot S, Faubert A, Laverdure JP, Frechette M, Chagraoui J, et al. A functional screen to identify novel effectors of hematopoietic stem cell activity. Cell. 2009;137:369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiyono K, Suzuki HI, Morishita Y, Komuro A, Iwata C, Yashiro M, et al. c-Ski overexpression promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis through inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta signaling in diffuse-type gastric carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1809–1816. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahata M, Inoue Y, Tsuda H, Imoto I, Koinuma D, Hayashi M, et al. SKI and MEL1 cooperate to inhibit transforming growth factor-beta signal in gastric cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:3334–3344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808989200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang P, Chen Z, Meng ZQ, Fan J, Luo JM, Liang W, et al. Dual role of Ski in pancreatic cancer cells: tumor-promoting versus metastasis-suppressive function. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1497–1506. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bravou V, Antonacopoulou A, Papadaki H, Floratou K, Stavropoulos M, Episkopou V, et al. TGFbeta repressors SnoN and Ski are implicated in human colorectal carcinogenesis. Cell Oncol. 2009;31:41–51. doi: 10.3233/CLO-2009-0460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang P, Chen Z, Meng Z, Fan J, Luo J, Liang W, et al. Dual role of Ski in pancreatic cancer cells: Tumor-promoting versus metastasis-suppressive function. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1497–1506. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoek KS, Eichhoff OM, Schlegel NC, Dobbeling U, Kobert N, Schaerer L, et al. In vivo switching of human melanoma cells between proliferative and invasive states. Cancer Res. 2008;68:650–656. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujita T, Epperly MW, Zou H, Greenberger JS, Wan Y. Regulation of the anaphase-promoting complex-separase cascade by transforming growth factor-beta modulates mitotic progression in bone marrow stromal cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:5446–5455. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-03-0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marcelain K, Hayman MJ. The Ski oncoprotein is upregulated and localized at the centrosomes and mitotic spindle during mitosis. Oncogene. 2005;24:4321–4329. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ueki N, Hayman MJ. Signal-dependent N-CoR requirement for repression by the Ski oncoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24858–24864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303447200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao HL, Ueki N, Marcelain K, Hayman MJ. The Ski protein can inhibit ligand induced RARalpha and HDAC3 degradation in the retinoic acid signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;383:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.03.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chakravarti N, Lotan R, Diwan AH, Warneke CL, Johnson MM, Prieto VG. Decreased expression of retinoid receptors in melanoma: entailment in tumorigenesis and prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4817–4824. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Egan KM. Vitamin D and melanoma. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:455–461. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iakova P, Awad SS, Timchenko NA. Aging Reduces Proliferative Capacities of Liver by Switching Pathways of C/EBPalpha Growth Arrest. Cell. 2003;113:495–506. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00318-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colmenares C, Teumer JK, Stavnezer E. Transformation-defective v-ski induces MyoD and myogenin expression but not myotube formation. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1167–1170. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.2.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]