Abstract

Background

Stressful life events (SLEs) play a key role in suicidal behavior among adults with alcohol use disorders (AUD), yet there are meager data on the severity of SLEs preceding suicidal behavior or the timing of such events.

Method

Patients in residential substance use treatment who made a recent suicide attempt (cases, n=101) and non-suicidal controls matched for site (n=101) were recruited. SLEs that occurred within 30 days of the attempt and on the day of the attempt in cases were compared to SLEs that occurred in the corresponding periods in controls. SLEs were categorized by type (interpersonal, non-interpersonal) and severity (major, minor) and were dated to assess timing. Degree of planning of suicide attempts was also assessed.

Results

Major interpersonal SLEs conferred risk for a suicide attempt, odds ratio (95% CI) = 5.50 (1.73, 17.53), p=.005. Cases were also more likely to experience an SLE on the day of the attempt than on the corresponding day in controls, OR (95% CI) = 6.05 (1.31, 28.02), p=.021. However, cases that made an attempt on the day of a SLE did not make lower planned suicide attempts compared to other cases, suggesting that suicide attempts that are immediately preceded by SLEs cannot be assumed to be unplanned.

Conclusions

Results suggest the central importance of major interpersonal SLEs in risk among adults with AUD, a novel finding, and documents that SLEs may lead to suicide attempts within a short window of time (i.e., same day), a daunting challenge to prevention efforts.

Keywords: alcohol use disorder, suicide attempt, suicide, stressful life event

1. Introduction

1.1. Stressful Life events (SLEs) and Suicide

Alcohol use disorders (AUD) are a potent risk factor for suicide (Cavanagh et al., 2003; Yoshimasu et al., 2008). Postmortem psychological autopsy studies (Hawton et al., 1998; Pouliot and De Leo, 2006) consistently document that interpersonal stressful life events (SLEs) precede suicide among adults with AUD. These studies have shown that interpersonal SLEs are the most common type of life event preceding suicide among individuals with AUD (Duberstein et al., 1993; Murphy, 1992; Rich et al., 1988), that interpersonal SLEs are more common among suicide decedents with AUD than suicides with depressive disorders (Duberstein et al., 1993; Heikkinen et al., 1994; Rich et al., 1988), and that interpersonal SLEs are elevated among suicide decedents with AUD compared to living community controls with AUD (Conner et al., 2003). These results demand attention to the role of interpersonal SLEs in suicide risk in individuals with AUD.

Psychological autopsy studies of individuals with AUD and other populations have focused on the role of SLE type (interpersonal event, legal event, etc.), with little attention to SLE severity, an omission that may be critical to interpreting SLE data. In particular it may be that interpersonal SLEs confer risk in individuals with AUD and other populations because the interpersonal SLEs recalled in psychological autopsy studies tend to be severe (e.g., partner separation). Providing indirect support for this idea, a national study in Finland showed that surviving spouses rated partner-relationship disruptions as the most severe type of SLE preceding suicide (Heikkinen et al., 1992). Accordingly, the severe nature of such events may explain why they confer risk. If it is event severity rather than event type per se that drives risk, then we would expect that SLEs judged to be severe, referred to hereafter as “major” events, confer risk regardless of event type (i.e., both major interpersonal events and major non-interpersonal events drive risk). Alternatively, if the interpersonal nature of SLEs is the critical ingredient rather than severity, then we would expect that interpersonal events confer risk regardless of the severity of such events (i.e., both major interpersonal events and minor interpersonal events confer risk). Finally, it may be that event type and severity are critical to consider in combination (i.e., major interpersonal events confer risk).

Psychological autopsy studies of adults with AUD have shown that interpersonal SLEs are concentrated within six weeks of death (Duberstein et al., 1993; Murphy and Robins, 1967; Murphy et al., 1979). The studies are limited by an uncontrolled research design and they may well miss critical patterns that emerge in far shorter time frames preceding suicidal behavior. Indeed, individuals with AUD are prone to suicidal behavior that is preceded by little planning (Jeon et al., 2010; Nock et al., 2010), suggesting that alcoholics may be especially vulnerable to a scenario whereby SLEs quickly lead to unplanned acts of suicide (Conner, 2004). Accordingly, we hypothesized that suicidal behavior that occurred on the same day as a SLE show lower planning (defined as the degree of forethought about an act of suicide prior to carrying it out) compared to suicidal acts that were not preceded by a SLE.

1.2. SLEs and Suicide Attempts

AUD also confers risk for non-fatal suicide attempts (Kessler et al., 1999) and it stands to reason that SLEs also precede suicide attempts. However, there are meager data on SLEs preceding suicide attempts among individuals with AUD because most data on attempts in this population are secondary analyses of datasets. Such analyses are capable of identifying distal risk factors but are not suited to identify difficulties that occur more proximally to suicidal behavior, the focus of psychological autopsy studies. Rare studies of SLEs preceding suicide attempts among adults with AUD are limited by long followback periods (i.e., one year) (Conner et al., 2003; Kingree et al., 1999), with unclear relevance to the individuals’ circumstances near to the attempt. With few exceptions (Yen et al., 2005), detailed studies of SLEs preceding suicide attempts are not available in other populations.

1.3. Purpose of Study

We examined the role of SLE type, severity, and timing in risk for suicide attempts in a clinical AUD sample. Using a case-control study design (Rothman and Greenland, 1998a), we tested the hypothesis that major interpersonal SLEs but not minor interpersonal SLEs confer risk for attempts, consistent with the idea that psychological autopsy studies of individuals with AUD have uncovered major interpersonal events, explaining their toxicity. We also explored risk for attempts associated with non-interpersonal SLEs, both major and minor. A further objective was to determine if SLEs were concentrated on the day of suicide attempts. Finally, we tested the hypothesis that attempts that occurred on the day of an SLE showed lower planning compared to other attempts.

2. Methods

2.1 Overview of Procedures

Participants were recruited from residential substance use treatment programs in Western New York State, USA. We screened all patient volunteers and administered in-depth interviews to potential cases and controls. The study was approved by the sites’ University institutional review boards. A Federal Certificate of Confidentiality was also obtained. Gift cards were used as compensation.

2.2 Screening

A total of 3043 patients were screened, representing 46.4% of admissions, including 2154 (70.8%) men and 889 (29.2%) women, with mean age = 38 ± 11 years, age range 18–73. Most were White non-Hispanic (1642, 54.0%) or Black non-Hispanic (1109, 36.4%). The screen determined case and control eligibility. Those who scored ≥8 on the 10-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test or AUDIT (Allen et al., 1997) and scored ≥21 on the Mini Mental Status Exam (Folstein et al., 1975), the recommended cutoff for use with clinical substance abuse populations (Smith et al., 2006), were eligible for inclusion. Cases and controls with regular intravenous drug use were excluded. Unique to cases, additional inclusion criteria were report of lifetime suicide attempt in response to the item “Have you ever tried to kill yourself or attempt suicide?” (Conner et al., 2007a) and follow-up questions indicating the most recent attempt occurred within 90 days of treatment entry. Unique to controls, additional exclusion criteria were any lifetime history of suicide attempt and any lifetime history of serious suicidal ideation in response to the item “Have you ever seriously thought about committing suicide?” (Kessler et al., 1999).

Of 3043 screened subjects, 128 (4.2%) were identified as potential cases, and 101 of these subjects were confirmed upon further questioning about suicide attempt history. For each case, a non-suicidal control subject at the same treatment site was recruited. Site was the only matching variable; we did not match controls to cases on age, sex, or other variables given potential biases associated with such matching (Kraemer, 2003; Rothman and Greenland, 1998b; Vandenbrouke et al., 2007).

2.3 Measures

2.3.1. Suicide attempt

Subjects were asked, “Have you ever tried to kill yourself or attempt suicide?” This item has shown high test-retest reliability, kappa = .82 (Conner et al., 2007a). Attempts were dated with a calendar.

2.3.2. Assessment of SLEs

We used a semi-structured SLE interview (Kendler et al., 1998; Kendler et al., 2003), with some modifications to suit an AUD treatment sample (e.g., increased coverage of victimization experiences). Interviewers were masked to case status to start the interview when the SLE assessment was conducted. Interviewers dated all events occurring within 90 days of admission to the substance use treatment program with the aid of a calendar. SLEs were defined as a new event that would be judged to be negative by the average person (e.g., being fired from job) or an event that marks the worsening of a chronic circumstance (e.g., being placed on probation at a job after prior warnings). We did not assess chronic stress or trivial hassles.

The SLE interviews were audiotaped or, if there was a technical difficulty, the interviewer took detailed notes. Subsequently, the tapes were played (or the notes reviewed) at a consensus meeting. The interviewer did not reveal the participant’s case status at these meetings. For each event, the team came to a decision about which type it represented (job, legal, etc.), and then proceeded to independently rate its “long-term contextual threat” (i.e., severity) on a 4-point scale (minor, low moderate, high moderate, severe). Severity ratings were based on the expected impact of a given SLE on an individual with a similar background facing similar circumstances. After making independent ratings, a consensus severity rating was reached. Average agreement between raters on severity, ICC=.62, was in the “good” range of agreement (Cicchetti, 1994) and comparable to prior research of the SLE instrument (Kendler et al., 1998).

For the analyses, we collapsed SLEs into two broad levels of severity including minor events (consensus rating of minor or low moderate) and major events (high moderate or severe) in the prior 30 days. We also collapsed SLEs into two broad types, interpersonal and non-interpersonal. Interpersonal SLEs include: divorce, separation, or break-up with a partner; problem getting along with a partner; separation in another relationship; problem getting along in another relationship; physical assault by someone known to the subject (except a mere acquaintance); rape or forced sex by someone known to the subject (except a mere acquaintance); death of an individual in the subject’s family or network. Non-interpersonal SLEs include: injury or illness; accident without injury; burglarized, robbed, or mugged; physical assault by an acquaintance or stranger; rape or forced sex by an acquaintance or stranger; move to unsafe neighborhood; housing problem; legal problem; job problem; lay off or fired from job; financial problem. Combining data on event severity and type, we created summary measures of interpersonal and non-interpersonal SLEs with three mutually exclusive categories: none, minor, major, yielding 6 scores. If a subject experienced both a minor and a major interpersonal event, major interpersonal SLE alone was coded. We excluded SLEs that coincided with the suicide attempt or followed the attempt because such SLEs were assumed not to play a causal role in the decision to attempt suicide. We retained the SLEs that occurred on the day of the attempt that temporally preceded the attempt because these events could conceivably play a causal role. For each control, we used the same corresponding exposure period. For example, for a case that made a suicide attempt on day 7 prior to admission to the substance use treatment program, we examined SLEs that occurred on days 7–37 in the case and in his/her corresponding control.

2.3.3. Planning of suicide attempts

Two Suicide Intent Scale or SIS items (Beck et al., 1974) on suicide preparation and premeditation respectively were used to assess planning (Beck et al., 1974; Conner, 2004). We also administered two self-report items created for the study. One item asked: “How much did you plan the suicide attempt?” with four choices from “none, no planning at all” (scored 0) to “great deal of planning, very well planned” (scored 3). The other item asked: “How long did you think about it before you made the suicide attempt?” with five choices from “less than 5 minutes” (scored 0) to “more than 1 week” (scored 4). The novel planning items showed acceptable test-retest reliability (r = .64, p<.001). To create a summary measure of planning, we doubled the scoring of each SIS item to score them 0, 2, or 4 (instead of 0, 1, or 2) and then took a sum of all items, yielding a 4-item measure with a range 0–15. Internal consistency was acceptable (α=.84) as was the item-total correlations for the SIS items (.65, .80) and the new items (.65, .71).

2.3.4. Covariates

Socio-demographic covariates were age (continuous), sex, race/ethnicity (white non-Hispanic, other), and education (< 12 years, ≥ 12). We also included four clinically-relevant covariates (Preuss et al., 2002; Roy et al., 1990). Alcohol-related severity: A reliable composite measure (α=.74) was created by combining assessments of 1) alcohol use based on AUDIT items 1–3, 2) alcohol-related difficulties based on AUDIT items 4–10, and 3) alcohol dependence symptom count assessed with the Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance Use and Mental Disorders or PRISM (Hasin et al., 1998; Hasin et al., 2006). Drug-related severity: A 10-item version of the Drug Abuse Screening Test (Cocco and Carey, 1998) was used to assess drug (non-alcohol) severity in the past year (α=.87). Aggression: We used the 5-item subscale of the Lifetime History of Aggression Questionnaire (Coccaro et al., 1997) (α=.76). Depression: Presence of major depressive episode within two months of treatment entry was assessed with the PRISM.

2.4. Analyses

2.4.1 Analyses of event type and severity

Unconditional logistic regression models were used (Agresti, 2002). Univariate analyses were first carried out to yield unadjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for suicide attempt associated with SLEs and covariates. Covariates with p-values <.20 in univariate analyses were retained in multivariate models (Neter et al., 1990). City of data collection was also used as a covariate. Two multivariate models were used to determine the associations between suicide attempt and SLEs; one included interpersonal SLEs (major, minor, none), and the other included non-interpersonal SLEs (major, minor, none). Hosmer and Lemeshow tests were used to assess model fits (Hosmer and Lemeshow, 1980). Primary analyses were analyzed using SAS statistical software version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, NC).

2.4.2. Analyses of event timing

Logistic regression models were also applied to the timing analyses in order to compare the probability of a case's exposure to a SLE on the day of the attempt to the probability of a corresponding control's exposure to a SLE. We also used a case-crossover analytic approach in which cases serve as their own controls (Borges et al., 2004; Maclure and Mittleman, 2000) in order to compare the probability of exposure of any SLEs on the same day of the suicide attempt (reference day) with the exposure of any SLEs on control periods defined as a) the day before the suicide attempt and b) each of the 30 days prior to the suicide attempt.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Data

Characteristics of cases and controls are presented in Table 1. Univariate analyses show that cases were more likely to be female (p=.002), to experience current depression (p<.001), and to have higher scores on alcohol severity (p=.030), drug severity (p<.001), and aggression (p<.001). Cases and controls did not differ on age (p=.195), race (p=.567), or education (p=.748), and consistent with our analytic strategy, the latter two variables were excluded from multivariate analyses.

Table 1.

Comparisons between suicide attempt cases and controls on stressful life events (SLEs) and covariates.

| Independent Variable | Descriptive Data | Univariate Results | Multivariate Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (101) N or Mean |

Controls (101) N or Mean |

OR (95% CI) | Interp SLE Model AOR (95% CI) |

Non-Interp SLE Model AOR (95% CI) |

|

| Female | 42 | 21 | 2.71** (1.46, 5.05) | 2.41* (1.18, 4.91) | 2.37* (1.18, 4.77) |

| Male | 59 | 80 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Age | 38.8 ± 9.7 | 40.7 ± 10.5 | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.02) |

| Nonwhite | 39 | 43 | 0.85 (0.48, 1.49) | N/A | N/A |

| White | 62 | 58 | 1.00 | N/A | N/A |

| Education < 12 yrs | 27 | 25 | 1.11 (0.58, 2.09) | N/A | N/A |

| Education ≥ 12 yrs | 74 | 76 | 1.00 | N/A | N/A |

| Alcohol severity score | 11.1 ± 2.9 | 10.2 ± 2.9 | 1.11* (1.01, 1.23) | 1.10 (0.98, 1.23) | 1.09 (0.97, 1.22) |

| Drug severity score | 7.5 ± 2.8 | 6.1 ± 3.1 | 1.18*** (1.07, 1.30) | 1.10 (0.98, 1.23) | 1.10 (0.99, 1.23) |

| Depressive episode | 63 | 28 | 4.32*** (2.39, 7.82) | 4.21*** (2.14, 8.30) | 4.11*** (2.12, 7.99) |

| Non-depressed | 38 | 73 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Aggression score | 16.0 ± 5.6 | 12.7 ± 4.9 | 1.13*** (1.06, 1.19) | 1.11** (1.04, 1.18) | 1.10** (1.04, 1.17) |

| Major interp SLE | 21a | 5 | 5.25** (1.88, 14.65) | 5.50** (1.73, 17.53) | N/A |

| Minor interp SLE | 12 | 11 | 1.36 (0.57, 3.28) | 0.93 (0.33, 2.60) | N/A |

| No interp SLE | 68 | 85 | 1.00 | 1.00 | N/A |

| Major non-interp SLE | 21 | 16 | 1.55 (0.74, 3.23) | N/A | 1.63 (0.69, 3.82) |

| Minor non-interp SLE | 19 | 13 | 1.73 (0.79, 3.78) | N/A | 1.27 (0.50, 3.25) |

| No non-interp SLE | 61 | 72 | 1.00 | N/A | 1.00 |

Note. Multivariate results depict a model with major- and minor interpersonal events adjusted for covariates (Interp SLE model) and a model with major- and minor non-interpersonal events plus covariates (Non-Interp SLE model).

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001.

OR = odds ratio. AOR = Adjusted odds ratio.

The 21 cases that experienced major interpersonal SLEs included divorce/separation (N=13), partner relationship problem (N=3), separation in another relationship (N=5), death of a family member or key network member (N=3), and physical assault victimization by an individual known to the subject (N=1). The events tally to > 21 because some cases experienced >1 major interpersonal SLE.

3.1.1. Additional descriptive information

Most participants (88.1% cases, 81.2% of controls) met alcohol dependence criteria, and dependence symptom count averaged (± SD) 5.4 ± 2.1 in cases and 4.8 ± 2.2 in controls. There was weekly or greater use of 1.6 ± 1.3 different categories of drugs (cannabis, cocaine, etc.) among cases and 1.1 ± 1.1 among controls. Suicide attempts were most often by drug ingestion (67%) or cutting (21%). Reattempts were common, with 80% of cases having made at least one prior suicide attempt, with mean lifetime number of attempts (including the index attempt) = 3.9 ± 4.1 and median = 3.

3.2. Analyses

3.2.1. Analyses of event type and severity

Univariate- and multivariate analyses of SLEs are shown in Table 1. The multivariate models fit the data well, with X2 = 4.21 (p=0.837) for the model with interpersonal SLEs, and X2 = 5.35 (p = 0.720) for the model with non-interpersonal SLEs. Major interpersonal SLEs conferred risk [OR (95% CI)] for suicide attempt in univariate [5.25 (1.88, 14.65), p=.002] and multivariate models [5.50 (1.73, 17.53), p=.005]. The other categories of SLEs were not associated with suicide attempt at a statistically significant level.

3.2.2. Analyses of event timing

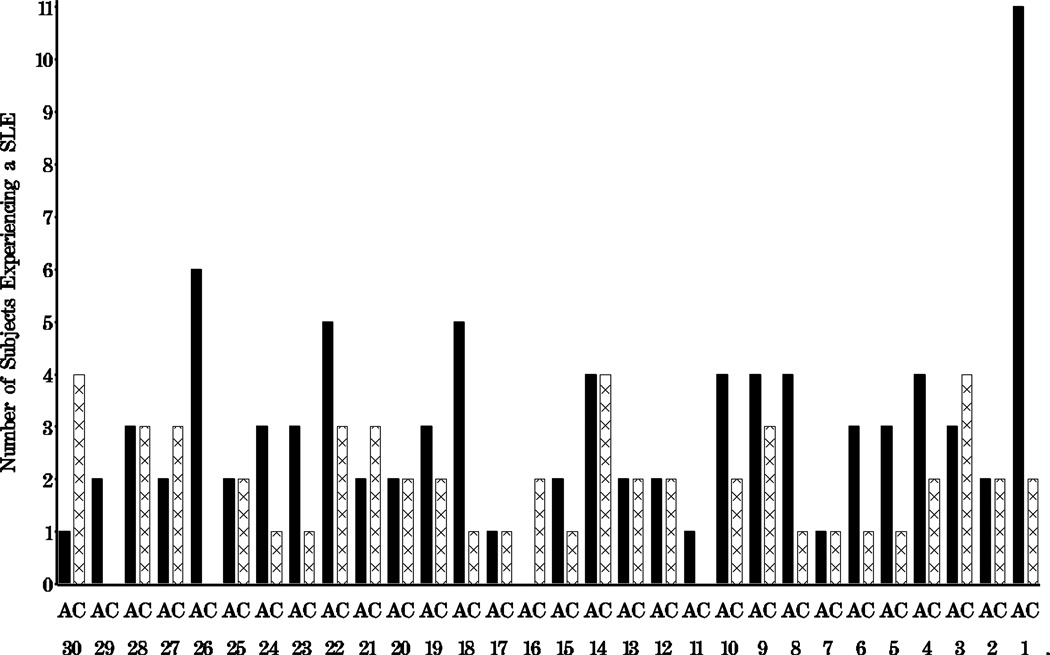

We plotted the day that SLEs occurred during the 30-day follow-back period in cases and the corresponding period in controls (Figure 1). Eleven cases showed an SLE on the day of the suicide attempt; these events were diverse including 2 major interpersonal SLEs, 3 minor interpersonal SLEs, 3 major non-interpersonal SLEs, and 4 minor non-interpersonal SLEs. The events sum > 11 because 1 case had two SLEs on the day of the attempt. Two controls experienced an SLE on the corresponding day. Because there were a limited number of SLEs on the day of the attempt and events of all type and severity were represented, we combined these events into a single category of exposure to SLE on the day of attempt (cases) and the corresponding day in controls.

Figure 1.

Number of suicide attempters (A) and controls (C) experiencing a SLE on a day-to-day basis over 30 days. Note. Day 1 = day of attempt in cases and the corresponding day in controls.

A univariate logistic comparison of SLEs on the day of attempt in cases and the corresponding day in controls was supportive of an elevation in SLEs in cases; OR (95% CI) = 6.05 (1.31, 28.02), p=.021. There were too few SLE occurrences within a day to adjust for covariates. Finally, in an analysis limited to cases and, using the novel 4-item measure of planning, we compared the degree of suicide planning of the 11 cases who experienced an SLE on the day of the suicide attempt (Mean = 5.36 ± 4.15) to the degree of planning in the remaining cases (4.92 ± 4.36). Results did not suggest a difference in planning in the two groups, t(1, 98) = −.032, p=.750.

3.3. Sensitivity Analyses

3.3.1. Sensitivity analyses of event type and severity

1) We re-ran the multivariate analysis by entering both types of events (interpersonal, non-interpersonal) simultaneously in a multivariate logistic model. 2) In the primary analyses we included deaths and physical- and sexual assaults perpetrated by individuals that subjects know and interact with (e.g., relationship partners) because such experiences involved interpersonal ties. In a sensitivity analysis we reassigned deaths and physical- and sexual assaults perpetrated by individuals that subjects know to the non-interpersonal SLE category and re-ran the multivariate analyses in order to determine if the results held when interpersonal SLEs were defined more narrowly. 3) We reran the multivariate analyses after removing 10 cases that did not show suicide intent (i.e., scored “0”) on the SIS items “perceived seriousness to end life” and “attitudes toward living/dying,” in order to meet a stricter definition of suicide attempt (Silverman et al., 2007). 4) We reran the primary models a) using robust logistic regression by employing sandwich estimates of the variance (White, 1980) using Stata software, Version Release 11 (Stata Corp, 2009, College Station, TX) and b) conditional logistic models using SAS that considered the case-control pairings (Hosmer and Lemeshow, 2000). In each analysis the same pattern of results were observed, with major interpersonal SLEs conferring substantial risk for attempt and none of the other SLE categories approaching significance.

3.3.2. Sensitivity analyses of event timing

1) In the logistic models, the same pattern of results were observed when we employed sandwich estimates and used conditional models, with cases more likely to experience an SLE on the day of the attempt than a corresponding day in controls. 2) Case-crossover analyses also indicated that cases were more likely to experience an SLE on the day of the attempt compared to a) the day before the suicide attempt, OR (95% CI) = 5.50 (1.22, 24.81), p=.027, and b) compared to each of the 30 days prior to the suicide attempt, OR (95% CI) = 4.49 (2.30, 8.75), p<.0001.

4. Discussion

4.1. SLE Type and Severity

The current study was the first to systematically examine both the type and severity of SLEs preceding suicidal behavior among adults with AUD. Results suggest that major interpersonal SLEs confer marked risk but that more minor interpersonal events and major non-interpersonal events do not. These results suggest the importance of determining if one of the mechanisms of change (Nock, 2007) for established individual treatments for suicidal behavior (Brown et al., 2005; Linehan et al., 2006) involves interrupting the cycle of interpersonal events and suicidal behavior by improving interpersonal relationships and, more specifically, by helping clients anticipate and plan for major inteprersonal SLEs, both affectively and pragmatically. The results also suggest that interventions that focus on major interpersonal life experiences such as Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depression (Klerman et al., 1984) should be tested to determine their potential to reduce risk for suicidal behavior among individuals with AUD. The current data and prior studies consistently show that partner-relationship separations are the most common interpersonal SLE preceding suicidal behavior among individuals with AUD (Conner et al., 2003; Duberstein et al., 1993; Murphy, 1992; Rich et al., 1988). Therefore, couples’ interventions demonstrated to be efficacious in the treatment of alcoholism, for example behavioral couples’ therapy (McCrady and Epstein, 2009), may also be evaluated for use with clients at-risk for suicidal behavior who are in partner relationships. The involvement in substance use treatment of key family members (e.g., parents) through regularly scheduled psychoeducational groups and more tailored family treatment session(s) can also be used to strengthen interpersonal relationships and provide a means to collaborate with family to develop strategies to monitor suicide risk and alert providers if warning signs appear or intensify (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2009).

4.2. SLE Timing

The current study was the first to use a detailed method to document SLEs on a day-to-day basis prior to suicidal behavior in an adult AUD sample. Among cases there was a concentration of SLEs on the day of attempts. These (same day) events were of various types and levels of severity, suggesting that even minor events and non-interpersonal events may confer a short-lived increased risk. In other words, the study does not support the idea that minor SLEs and non-interpersonal SLEs (minor or major) confer risk for an attempt when a 30-day exposure period is analyzed, but narrowing the exposure period brings out the fact that such events may increase risk for a short period of time (i.e., 1 day). There was no apparent difference in level of planning between suicide attempts that occurred within a day of an SLE and those that occurred more remotely, despite the crescendo of events preceding the act in some cases. A potential explanation is that SLEs serve as the “last straw” among vulnerable individuals who had been contemplating suicidal behavior (Conner et al., 2007b). Under this scenario, concentration of events but not unplanned suicidal behavior per se would be expected to occur, consistent with the results.

4.3. Limitations

There was a moderate participation rate and sample size. We studied suicide attempts in a generally severe adult alcoholism treatment sample. Therefore, generalization to suicide deaths and to other study populations or age groups is unclear. Nonetheless, the results seem consistent with the general literature that implicate interpersonal SLEs in suicidal behavior (Van Orden et al., 2010). The procedure to mask interviewers to case status during the inquiry into SLEs was not foolproof as some subjects revealed their case status prior to being asked. The limited number of first-time attempts in the sample precluded the ability to examine if SLEs conferred greater risk for first vs. repeat attempts, a question of interest in light of data that SLEs may play a greater role in first episodes of depression (Monroe and Harkness, 2005). The study did not address the role of chronic stress or distal events in risk; cohort studies are better equipped to examine the role of these stressors in suicidal behavior. Day-to-day drinking data were not gathered using retrospective followback methodology (e.g., (Sobell and Sobell, 1996) which could have served as an interesting complement to the daily assessments of SLEs.

4.4. Future Directions

The identification of mediators of the relationship between major interpersonal SLEs and suicidal behavior is a logical next step. One possibility is that interpersonal SLEs lead to thwarted belonging (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010) which has been shown to be associated with suicide attempts in substance use disorder patients (Conner et al., 2007a; You et al., 2011). Another potential mediator is “humiliation” which is linked to the onset of depression (Brown et al., 1995; Kendler et al., 2003) and is conceptually separable from thwarted belonging. The study also provides an organizing framework (i.e., SLE type, severity, and timing) for research on SLEs and suicidal behavior that is widely applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Litten RZ, Fertig JB, Babor T. A review of research on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1997;21:613–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Schuyler D, Herman I. Development of suicidal intent scales. In: Beck AT, Resnick CL, Lettieri D, editors. The Prediction of Suicide. Bowie, MD: Charles Press; 1974. pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Cherpitel CJ, Macdonald S, Giesbrecht N, Stockwell T, Wilcox HC. A case-crossover study of acute alcohol use and suicide attempt. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2004;65:708–714. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GK, Have TT, Henriques GR, Xie SX, Hollander JE, Beck AT. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:563–570. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris TO, Hepworth C. Loss, humiliation and entrapment among women developing depression: a patient and non-patient comparison. Psychol. Med. 1995;25:7–21. doi: 10.1017/s003329170002804x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh JTO, Carson AJ, Sharpe M, Lawrie SM. Psychological autopsy studies of suicide: a systematic review. Psychol. Med. 2003;33:395–405. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rep. No. HHS No. (SMA) 09-4381. Rockville, MD: 2009. Addressing Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors in Substance Abuse Treatment. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol. Assess. 1994;6:284–290. [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF, Berman ME, Kavoussi RJ. Assessment of life history of aggression: development and psychometric characteristics. Psychiatry Res. 1997;73:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(97)00119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocco KM, Carey KB. Psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test in psychiatric outpatients. Psychol. Assess. 1998;10:408–414. [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR. A call for research on planned vs. unplanned suicidal behavior. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2004;34:89–98. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.2.89.32780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Beautrais AL, Conwell Y. Risk factors for suicide and medically serious suicide attempts among alcoholics: analyses of Canterbury Suicide Project Data. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2003;64:551–554. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Britton PC, Sworts LM, Joiner T. Suicide attempts among individuals with opiate dependence: the role of belonging. Addict. Behav. 2007a;32:1395–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Phillips MR, Meldrum SC. Low intent and high intent suicide attempts in rural China. Am. J. Public Health. 2007b;97:1842–1846. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.077420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, Caine ED. Interpersonal stressors, substance abuse, and suicide. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1993;181:80–85. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199302000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Samet S, Nunes E, Meydan J, Matseoane K, Waxman R. Diagnosis of comorbid psychiatric disorders in substance users with the Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders for DSM-IV. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2006;163:689–696. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Trautman K, Endicott J. Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders: phenomenologically based diagnosis in patients who abuse alcohol or drugs. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1998;34:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Appleby L, Platt S, Foster T, Cooper J, Malmberg A. The psychological autopsy approach to studying suicide: a review of methodological issues. J. Affect. Disord. 1998;50:269–276. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen ME, Aro HM, Henriksson MM, Isometsä ET, Sarna SJ, Kuoppasalmi KI, Lonngvist JK. Differences in recent life events between alcoholic and depressive nonalcoholic suicides. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1994;18:1143–1149. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen ME, Aro HM, Lönnqvist JK. Recent life events and their role in suicide as seen by their spouses. Acta Pscyhiatr. Scand. 1992;86:489–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb03303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. A goodness-of-fit test for the multiple logistic regression model. Communication Stat. 1980;10:1043–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression (2nd Ed.) New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon HJ, Lee JY, Lee YM, Hong JP, Won SH, Cho SJ, Kim JY, Chang SM, Lee HW, Cho MJ. Unplanned versus planned suicide attempters, precipitants, methods, and an association with mental disorders in a Korea-based community sample. J. Affect. Disord. 2010;127:274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T. Why People Die by Suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Hettema JM, Butera F, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Life event dimensions of loss, humiliation, entrapment, and danger in the prediction of onsets of major depression and generalized anxiety. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2003;60:789–796. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Stressful life events and major depression: risk period, long-term contextual threat, and diagnostic specificity. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1998;186:661–669. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199811000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1999;56:617–625. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingree JB, Thompson MP, Kaslow NJ. Risk factors for suicide attempts among low-income women with a history of alcohol problems. Addict. Behav. 1999;24:583–587. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron ES. Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depression. New York: Basic Publishing; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC. Current concepts of risk in psychiatric disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2003;16:421–430. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ, Heard HL, Korslund KE, Tutek DA, Reynolds SK, Lindenboim N. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs. therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2006;63:757–766. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclure M, Mittleman MA. Should we use a case-crossover design? Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2000;21:193–221. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, Epstein EE. Overcoming Alcohol Problems: A Couples-focused Program: Therapist Guide. Oxford, New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Harkness KL. Life stress, the "kindling" hypothesis, and the recurrence of depression: considerations from a life stress perspective. Psychol. Rev. 2005;112:417–445. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.112.2.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy GE. Suicide in Alcoholism. Oxford, New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy GE, Armstrong JW, Hermele SL, Fischer JR, Clendenin WW. Suicide and alcoholism: interpersonal loss confirmed as a predictor. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1979;36:65–69. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780010071007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy GE, Robins E. Social factors in suicide. JAMA. 1967;199:81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neter J, Wasserman W, Kutner MH. Applied Statistical Models (3rd Ed.) Boca Raton, FL: CRC Lewis Publishers; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK. Conceptual and design essentials for evaluating mechanisms of change. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2007;31:S3–S12. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Mental disorders, comorbidity and suicidal behavior: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol. Psychiatry. 2010;15:868–876. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouliot L, De Leo D. Critical issues in psychological autopsy studies. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2006;36:491–510. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.5.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss UW, Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Danko GP, Buckman K, Bierut L, Bucholz KK, Hesselbrock MN, Hesselbrock VM, Reich T. Comparison of 3190 alcohol-dependent individuals with and without suicide attempts. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2002;26:471–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich CL, Fowler RC, Fogarty LA, Young D. San Diego suicide study III. relationships between diagnoses and stressors. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1988;45:589–592. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800300087012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Case-control studies. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, editors. Modern Epidemiology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1998a. pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Matching. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, editors. Modern Epidemiology (2nd Ed.) Philadelphia, PA: Lipincott-Raven; 1998b. pp. 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Roy A, Lamparski D, DeJong J, Moore V, Linnoila M. Characteristics of alcoholics who attempt suicide. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1990;147:761–765. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman MM, Berman AL, Sanddal ND, O'Carroll PW, Joiner TE. Rebuilding the Tower of Babel: a revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors part 2: suicide-related ideations, communications, and behaviors. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2007;37:264–277. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KL, Horton NJ, Saitz R, Samet JH. The use of the mini-mental state examination in recruitment for substance abuse research studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;82:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. User's Guide. Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation; 1996. Timeline Followback: A Calendar Method for Assessing Alcohol and Drug Use. [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite S, Selby EA, Joiner TE. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol. Rev. 2010;117:575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbrouke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, Poole C, Schlesselman JJ, Egger M the Strobe Initiative. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica. 1980;48:817–830. [Google Scholar]

- Yen S, Pagano ME, Shea MT, Grilo CM, Gunderson J, Skodol AE, McGlashan TH, Sanislow CA, Bender DS, Zanarini MC. Recent life events preceding suicide attempts in a personality disorder sample: findings from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005;73:99–105. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimasu K, Kiyohara C, Miyashita K. Suicidal risk factors and completed suicide: meta-analyses based on psychological autopsy studies. Environ. Health Prevent. Med. 2008;13:243–256. doi: 10.1007/s12199-008-0037-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You S, Van Orden K, Conner KR. Social connections and suicidal behavior. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2011;25:180–184. doi: 10.1037/a0020936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]