Abstract

Paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesias is a paroxysmal movement disorder characterized by recurrent, brief attacks of abnormal involuntary movements induced by sudden voluntary movements. Although several loci, including the pericentromeric region of chromosome 16, have been linked to paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesias, the causative gene has not yet been identified. Here, we identified proline-rich transmembrane protein 2 (PRRT2) as a causative gene of paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesias by using a combination of exome sequencing and linkage analysis. Genetic linkage mapping with 11 markers that encompassed the pericentromeric of chromosome 16 was performed in 27 members of two families with autosomal dominant paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesias. Then, the whole-exome sequencing was performed in three patients from these two families. By combining the defined linkage region (16p12.1–q12.1) and the results of exome sequencing, we identified an insertion mutation c.649_650InsC (p.P217fsX7) in one family and a nonsense mutation c.487C>T (p.Q163X) in another family. To confirm our findings, we sequenced the exons and flanking introns of PRRT2 in another three families with paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesias. The c.649_650InsC (p.P217fsX7) mutation was identified in two of these families, whereas a missense mutation, c.796C>T (R266W), was identified in another family with paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesias. All of these mutations completely co-segregated with the phenotype in each family. None of these mutations was identified in 500 normal unaffected individuals of matched geographical ancestry. Thus, we have identified PRRT2 as the first causative gene of paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesias, warranting further investigations to understand the pathogenesis of this disorder.

Keywords: proline-rich transmembrane protein 2, paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesias, whole-exome sequencing, linkage analysis

Introduction

Paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesias (PKD) is a relatively rare neurological disorder of unknown cause. The characteristic of PKD is recurrent and brief attacks of involuntary movements that are triggered by sudden voluntary movements (Kertesz, 1967; Goodenough et al., 1978; Demirkiran and Jankovic, 1995; Bruno et al., 2004).The episodes usually present with dystonia, chorea, athetosis, ballism or their combination. The attacks usually last from a few seconds to a few minutes. During the attacks, there is absolutely no loss or alteration of consciousness. However, the prognosis of PKD is favourable and the patients usually show excellent responses to antiepileptic drugs (Kertesz, 1967; Goodenough et al., 1978; Houser et al., 1999; Lotze and Jankovic, 2003; Bruno et al., 2004). It is noteworthy that in some patients or their first- and second-degree relatives, PKD is often combined with other intermittent neurological disorders, like infantile convulsions or infantile convulsion and choreoathetosis (Tomita et al., 1999; Swoboda et al., 2000; Bruno et al., 2004). PKD can be classified as primary or secondary according to its aetiology (Goodenough et al., 1978; Demirkiran and Jankovic, 1995; Blakeley and Jankovic, 2002). Most of the cases with secondary PKD are caused by multiple sclerosis, head injury, metabolic derangements or cerebral perfusion insufficiency (Blakeley and Jankovic, 2002; Perona-Moratalla et al., 2009). Primary PKD can be further classified as idiopathic or familial PKD according to the hereditary nature. Familial PKD cases are the most common and are usually inherited in an autosomal dominant manner (Goodenough et al., 1978; Demirkiran and Jankovic, 1995; Marsden, 1996; Perona-Moratalla et al., 2009). Tomita et al. (1999) performed a genome-wide linkage and haplotype analysis in eight Japanese families and assigned the first PKD-critical region to a region between D16S3093 and D16S416. They named this 12.4cM region at 16p11.2–q12.1 as EKD1 (episodic kinesigenic dyskinesias 1). In the following years, a number of other linkage studies on a variety of ethnicities confirmed EKD1, which encompassed the pericentromeric of chromosome 16 and shared a minimum overlap region between D16S3093 and D16S3396 (Bennett et al., 2000; Swoboda et al., 2000; Cuenca-Leon et al., 2002; Kikuchi et al., 2007; Wang X et al., 2010). Moreover, two other regions that did not overlap with EKD1 were also identified and defined as EKD2 (16q13–q22.1) and EKD3, respectively (Valente et al., 2000; Spacey et al., 2002). Nevertheless, no causative gene of PKD has been identified thus far.

A recently developed technology using whole-exome capture and high-throughput sequencing provides a powerful and affordable means to identify disease-causing genes. Recent studies have demonstrated the sensitivity and accuracy of the exome-sequencing approach in the identification of the causal genes of several rare monogenic diseases such as Miller syndrome (Ng et al., 2010) and Bartter syndrome (Choi et al., 2009). In 2010, we identified transglutaminase 6 as a novel causative gene of spinocerebellar ataxias using the combined strategy of exome sequencing and linkage analysis (Wang JL et al., 2010). Here, we applied a similar strategy to screen the causative gene of PKD.

Materials and methods

Families and patients

This study was approved by the Expert Committee of Xiangya Hospital of the Central South University in China (equivalent to an Institutional Review Board). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Five Chinese Han PKD families presenting as autosomal dominant inheritance were included. A total of 75 members including 24 patients with PKD were enrolled. Families A and B were PKD pedigrees associated with other intermittent neurological disorders, in which both Patients III: 2 and III: 5 in Family A as well as Patients III: 3 and III: 5 in Family B were diagnosed with infantile convulsion and choreoathetosis syndrome. Families C–E were PKD pedigrees without any other paroxysmal conditions such as epilepsy, migraine or episodic ataxia. Among the 24 patients, the mean age at onset of the disease was 9.6 years (range 4–18 years). Attacks were usually precipitated by sudden movements, intention to move, startles, stress and anxiety. The symptoms of attacks consisted of dystonia, chorea and athetoid movements. The duration of the entire attack lasted from a few seconds to 1 min. Neither loss nor impairment of consciousness was observed in the attacks. Neurological examinations and imaging findings between attacks were entirely normal.

All the available affected individuals were subjected to a thorough neurological examination by two or more experienced neurologists. Clinical data were collected by interviews and clinical questionnaires, and the diagnosis of PKD was determined according to the criteria designed by Bruno et al. (2004). Individuals were diagnosed with infantile convulsions if they experienced non-febrile convulsions at the age of 3–12 months (Rochette et al., 2008). Infantile convulsion and choreoathetosis syndrome diagnoses were made according to Szepetowski et al. (1997). Unaffected individuals (n = 500) of matched geographic ancestry were also included as healthy controls. Genomic DNA was prepared from venous blood by standard procedures.

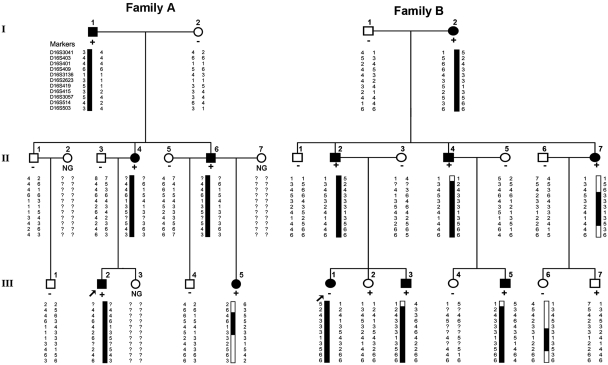

The first set of analyses was performed in Families A and B (Fig. 1). A total of 11 subjects (Patients I: 1–2; II: 1, 3–6; III: 1–2, 4–5) in Family A and 16 subjects (Patients I: 1–2; II: 1–7; III: 1–7) in Family B were included in the linkage study. Three individuals (Patient II: 4 in Family A, Patients II: 2 and II: 4 in Family B) were studied with exome sequencing. Three additional unrelated autosomal dominant PKD pedigrees (Families C–E) were used for subsequent mutational screening.

Figure 1.

Linkage analysis of Families A and B mapped the PKD to a region on chromosome 16p12.1-q12.1. The partial pedigrees of Families A and B were shown and haplotype analysis was indicated on chromosome 16 using 11 markers. The haplotype assumed to carry the disease allele is indicated with black bars. The haplotype with recombination event is indicated with black and white bars. Subjects in Families A and B are identified by the Arabic numerals above the symbol; and the Roman numerals denote the generations. Open symbols = unaffected; filled symbols = affected; symbols with a diagonal line = deceased subjects; squares = male; circles = female; arrow = the proband; minus = wild-type allele; plus = mutant allele; NG = not genotyped.

Genotyping for linkage analysis

Genotyping was performed using 11 microsatellite markers (D16S3041, D16S403, D16S401, D16S409, D16S3136, D16S2623, D16S419, D16S415, D16S3057, D16S514, D16S503) in chromosome 16 with primers tagged with fluorescence (HEX, FAM). The markers were amplified by polymerase chain reaction using the method as described (Tang et al., 2004). Relative positions were derived from the human genome draft sequence and the Marshfield map (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Two-point logarithm of odds scores were calculated using Linkage 5.2 package, with the assumptions that, in the two families, PKD is inherited in an autosomal dominant mode with 95% penetrance, that the frequency of the mutant allele is 0.0001, and that the allele frequency of each marker locus is equal (Lathrop and Lalouel, 1984; Dib et al., 1996). The haplotype in the two pedigrees was reconstructed manually using the Cyrillic program.

Exome sequencing

Library preparation and exome sequencing

Qualified genomic DNA extracted from the three patients (Patient II: 4 from Family A, Patients II: 2 and II: 4 from Family B) was sheared by sonication and then hybridized to the SureSelect Biotiny lated RNA Library (BAITS) for enrichment, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The enriched library targeting the exome was sequenced on the HiSeq 2000 platform to get paired-end reads with read length of 90 bp.

Alignment, single-nucleotide polymorphism and insertions or deletions calling

The sequenced reads were aligned to the human genome reference (UCSC hg 18 version) using SOAPaligner (Li et al., 2008). Those reads were then aligned in the designed target regions and were collected for single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) calling and subsequent analysis. We estimated the consensus genotype and quality by SOAPsnp (v 1.03) (Li et al., 2010). The low-quality variations were filtered out by the following criteria: (i) consensus quality score <20 (Q20); (ii) average copy number at the allele site ≥2; (iii) distance of two adjacent SNPs <5 bp; and (iv) sequencing depth <4 or >500. For insertions or deletions (indels) in the targeted exome regions, we aligned the reads to the reference genome using bwa. The alignment result was used to identify the breakpoints by gatk. Finally, we annotated the genotypes of insertions and deletions (Li and Durbin, 2010).

Analysis protocol for exome-sequencing results

Based on the hypothesis that the mutation underlying families with PKD should not be present in the general population, non-synonymous/splice acceptor and donor site/insertions or deletions (NS/SS/Indel) variants reported in the dbSNP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/, Build 129), eight previously exome-sequenced HapMap samples (‘HapMap 8’) and 1000 Genome Project (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Ftp/) were removed. Synonymous changes were identified and filtered from the variant list using SIFT software (version 4.0, http://sift.jcvi.org/).

Moreover, we only focused on the genes with NS/SS/Indel variants occurring in the linkage region. We further assumed that all three exome-sequenced patients should show NS/SS/Indel variants in the same gene, although the NS/SS/Indel variants might not be identical in all patients. Sanger sequencing using customized primers was performed to determine the presence of the variants in all the clinically affected subjects and to screen the unaffected members in Families A and B for co-segregation analysis. We then sequenced all the exons and flanking introns of the PRRT2 gene (NM_145239) in patients of three additional families (Families C–E) to detect other mutation sites using the traditional method. As an additional step, the detected variants were sequenced in 500 neurologically normal control subjects.

Results

The clinical characteristics of families with paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesias

Detailed clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The five families in our study shared some common features of PKD such as trigger and duration of attack, no loss of consciousness during attack and good response to treatment with anticonvulsants. Besides these features, the five families also presented with a wide spectrum of clinical heterogeneity. The onset age of the patients in Families A and C–E was ∼10 years old, while some patients in Family B (Patients III: 3 and III: 5) were younger (4 and 5 years old). The characteristics of the attacks varied not only between families but also among individuals in the same family. For example, there were two members separately diagnosed with infantile convulsion and choreoathetosis syndrome in infancy in Family A (Patients III: 2 and III: 5) and Family B (Patients III: 3 and III: 5). The main manifestation in Family A was dystonia, choreoathetosis or athetosis, while dystonia were predominant in Family B. We noted that dystonia of the upper limbs was more obvious in Family D, while in Family C lower limbs were more likely to be involved and the patients tended to fall down when attacks occurred. Although sudden movements induced attacks in all cases, there may have been some other triggers such as anxiety, startle and intention to move in a relatively smaller number of patients.

Table 1.

Clinical features in 24 affected members from the five PKD families

| Patient and sex | Patient age (years) |

Features of PKD |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At present | At onset | At remission | Trigger | Sensory aura | Duration of attacks (second) | Involuntary movement | Response to anticonvulsants | History of IC (month) | EEG | CT or MRI scan | |

| A(I: 1), M | 65 | 18 | ≥20 | SM | No | <5 | D | No treatment | None | – | – |

| A(II: 4), F | 41 | 10 | 25–26 | SM | No | <5 | D/A | No treatment | None | – | – |

| A(II: 6), M | 39 | 6 | Current | SM/S | Yes | 10–60 | D/C | PHT(+) | None | Normal | – |

| A(III: 2), M | 19 | 10 | Current | SM/S | Yes | <30 | D/C | CBZ(+) | 6–24 | Normal | Normal |

| A(III: 5), F | 18 | 10 | Current | SM/An | No | <5 | A | CBZ(+) | 12–24 | Normal | Normal |

| B(I: 2), F | 63 | 13 | 20 | SM | No | <30 | D | No treatment | None | – | – |

| B(II: 2), M | 41 | 10 | 26 | SM | No | <5 | D | No treatment | None | Normal | Normal |

| B(II: 4), M | 38 | 8 | 28 | SM | No | <30 | D | No treatment | None | – | – |

| B(II:7), F | 36 | 8 | 25 | SM | No | 30–60 | D | No treatment | None | Normal | Normal |

| B(III: 1), F | 19 | 16 | Current | SM/S | No | <30 | D | CZ(+) | None | – | – |

| B(III: 3), M | 6 | 4 | Current | SM | No | <5 | D | CBZ/CZ(+) | 6–24 | Normal | Normal |

| B(III: 5), M | 7 | 5 | Current | SM | No | <5 | D | CBZ/CZ(+) | 6–24 | Normal | Normal |

| C(II: 3), M | 59 | 10 | 29 | SM/S/IM | Yes | <30 | D/C | No treatment | None | – | – |

| C(II: 6), F | 52 | 9 | 24 | SM/S/IM | Yes | 30–60 | D | No treatment | None | – | – |

| C(II: 10), M | 50 | 9 | 25 | SM/S/IM | Yes | <30 | D/C | No treatment | None | – | Normal |

| C(II: 11), M | 47 | 10 | 30 | SM/S/IM | Yes | <30 | D | CBZ(+) | None | Normal | Normal |

| C(III: 17), F | 19 | 8 | Current | SM/S/IM | Yes | 30–60 | D | CBZ(+) | None | Normal | Normal |

| C(III: 19), F | 16 | 9 | Current | SM/IM | Yes | <30 | D/C | CBZ(+) | None | Normal | Normal |

| D(II: 1), M | 48 | 8 | 23 | SM/IM | No | <30 | D/C | PHT/PB(+) | None | Normal | – |

| D(II: 8), F | 43 | 10 | 25 | SM | No | <30 | D | No treatment | None | – | – |

| D(III: 1), M | 26 | 9 | 35 | SM/IM | No | <30 | D/C | CBZ(+) | None | Normal | Normal |

| D(III: 3), M | 21 | 13 | Current | SM/IM | Yes | <30 | D/C | CBZ(+) | None | Normal | Normal |

| E(I: 2), F | 48 | 8 | 23 | SM | No | <5 | D | No treatment | None | – | – |

| E(II: 1), F | 22 | 10 | Current | SM | Yes | <30 | D | CBZ(+) | None | Normal | Normal |

F = female; M = male; SM = sudden movement; S = stress or startle; IM = intention to move; An = anxiety; D = dystonia; C = choreoathetosis; A = athetosis; CBZ = carbamazepine; PHT = phenytoin; PB = phenobarbital; CZ = clonazepam.

Linkage mapping of the syndrome to chromosome 16p12.1-q12.1

Two-point logarithm of odds scores are shown in Table 2. A maximum two-point logarithm of odds score of 3.77 (θ = 0) was obtained at mark D16S409, when penetrance was assumed to be 0.95. The highest probability haplotype in Families A and B was reconstructed manually using the Cyrillic program (Fig. 1) and some key recombinant events were identified. In Family A, recombination was present between D16S403 and D16S401 in the short arm as well as between D16S2623 and D16S419 in the long arm of chromosome 16 in Patient III: 5, suggesting the candidate risk gene in Family A was located in a region between D16S403 and D16S419.

Table 2.

Two-point logarithm of odds scores between the disease locus and 11 microsatellite markers on chromosome 16 in Families A and B

| Marker | LOD score at θ = * |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | |

| D16S3041 | −10.85 | −1.48 | −0.57 | −0.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Family A | −4.71 | −0.45 | −0.20 | −0.08 | −0.02 | 0.00 |

| Family B | −6.14 | −1.03 | −0.37 | −0.09 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| D16S403 | −8.14 | 0.28 | 0.58 | 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.00 |

| Family A | −4.42 | −0.22 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| Family B | −3.72 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0.28 | 0.00 |

| D16S401 | −2.99 | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.67 | 0.37 | 0.00 |

| Family A | 0.87 | 0.74 | 0.59 | 0.42 | 0.23 | 0.00 |

| Family B | −3.86 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.00 |

| D16S409 | 3.77 | 3.14 | 2.45 | 1.68 | 0.84 | 0.00 |

| Family A | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.41 | 0.22 | 0.00 |

| Family B | 2.90 | 2.41 | 1.87 | 1.26 | 0.62 | 0.00 |

| D16S3136 | 1.47 | 1.20 | 0.91 | 0.59 | 0.28 | 0.00 |

| Family A | 0.87 | 0.74 | 0.59 | 0.42 | 0.23 | 0.00 |

| Family B | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| D16S2623 | 1.91 | 1.88 | 1.56 | 1.10 | 0.57 | 0.00 |

| Family A | 1.47 | 1.20 | 0.91 | 0.59 | 0.28 | 0.00 |

| Family B | 0.44 | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.51 | 0.30 | 0.00 |

| D16S419 | −2.22 | 1.87 | 1.64 | 1.15 | 0.56 | 0.00 |

| Family A | −3.83 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.00 |

| Family B | 01.6 | 1.62 | 1.34 | 0.93 | 0.46 | 0.00 |

| D16S415 | 1.89 | 1.82 | 1.46 | 0.99 | 0.47 | 0.00 |

| Family A | 0.87 | 0.70 | 0.52 | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.00 |

| Family B | 1.02 | 1.13 | 0.95 | 0.65 | 0.31 | 0.00 |

| D16S3057 | 1.61 | 1.63 | 1.35 | 0.95 | 0.49 | 0.00 |

| Family A | 1.47 | 1.20 | 0.90 | 0.59 | 0.28 | 0.00 |

| Family B | 0.14 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.22 | 0.00 |

| D16S514 | −2.53 | 1.05 | 1.18 | 0.95 | 0.53 | 0.00 |

| Family A | 1.17 | 0.95 | 0.70 | 0.45 | 0.20 | 0.00 |

| Family B | −3.70 | 0.1 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.00 |

| D16S503 | 0.59 | 0.46 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| Family A | 0.59 | 0.46 | 0.31 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| Family B | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

LOD = logarithm of odds; * = different recombination fraction.

In Family B, recombination was observed between D16S401 and D16S409 in the short arm, as well as between D16S3057 and D16S514 in the long arm of chromosome 16 in Patient II: 7. While the unaffected descendents (Patient III: 6) of this patient carried partial haplotype with recombination near D16S2623 and D16S3057, suggesting the candidate risk gene in Family B was located in a region between D16S401 and D16S2623. Together with the results of Family A, a single haplotype between D16S401 and D16S2623 co-segregated with the phenotype in all examined patients with PKD in these two families (Fig. 1). Therefore, the haplotype analyses traced PKD to chromosome 16p12.1-q12.1 with a maximum two-point logarithm of odds score of 3.77(θ = 0).

Exome sequencing identified PRRT2 as the candidate gene

To identify the causative gene of PKD, exome sequencing was performed on DNA samples obtained from three affected members of Families A and B (Fig. 1: Patient II: 4 in Family A, Patients II: 2 and II: 4 in Family B). We generated an average of 6.82 Gb of sequence from each affected individual as paired-end, 90-bp reads; 6.15 Gb (90.18%) passed the quality assessment and were aligned to the human reference sequence; and an average of 3.62 Gb of sequence data was mapped to the target region.

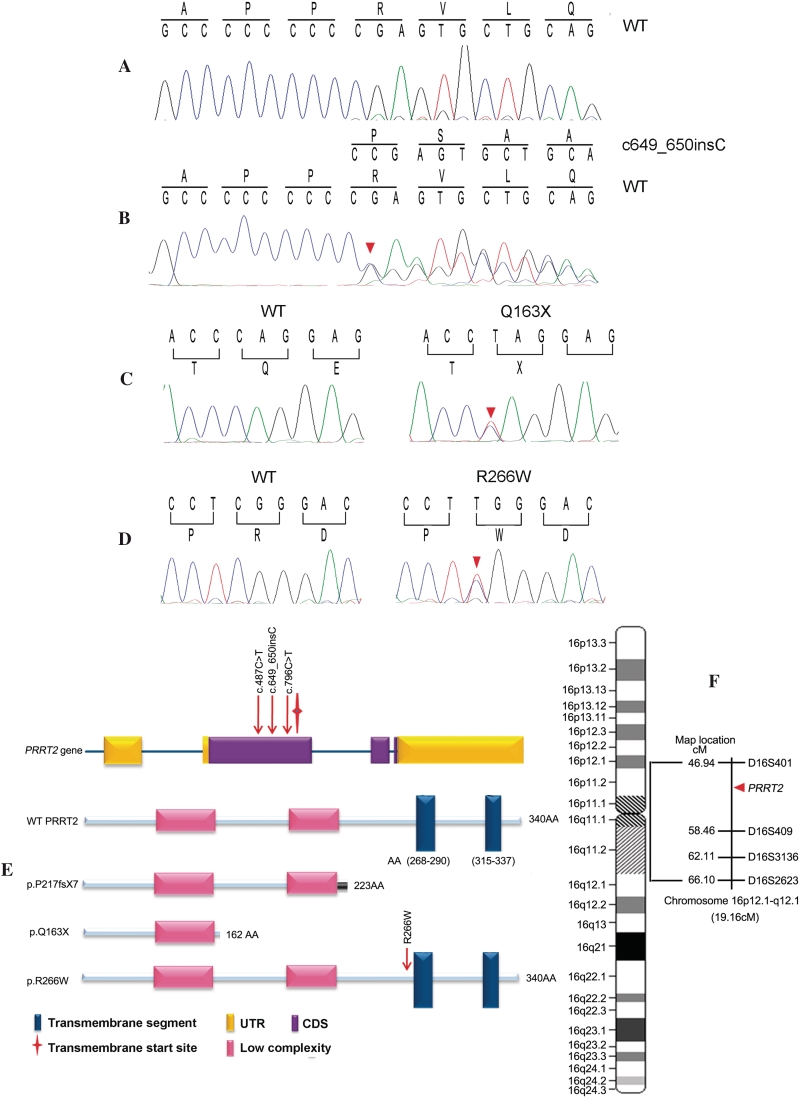

After SNPs and Indels calling, we identified a mean of 96 645 variants from the reference sequence per subject, in which an average of 10 756 NS/SS/Indel variants were detected in each of the PKD patients sequenced. Given that this is a rare disorder, it is unlikely that causative variants will be present in the general population. We therefore removed the NS/SS/Indel variants reported in the dbSNP129, ‘HapMap 8’ and the SNP release of the 1000 Genome Project. After this initial filter, we generated an average of 612 NS/SS/Indel variants from each patient. We then focused on the genes with NS/SS/Indel variants occurring in the linkage region (16p12.1-q12.1). During this step, we identified five, three and five NS/SS/Indel variants from Patient II: 4 in Family A, and Patients II: 2 and II: 4 in Family B, respectively. Finally, we assumed that all three patients should show NS/SS/Indel variants in the same gene. As a result, PRRT2 was found to be the sole gene with mutations occurring in all three patients (Fig. 3F). The mutations included an insertion mutation c.649_650InsC (p.P217fsX7) in Family A, and a nonsense mutation c.487C>T (p.Q163X) in Family B. The mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Fig. 3B and C).

Figure 3.

Mutations of the PRRT2 gene. (A) Sanger sequencing of codons 214–220 of PRRT2 in a wild-type (WT) subject and (B) the c.649_650InsC (p.P217fsX7) mutation. The mutation results in a frame-shift, which generates different sequences starting at position 217 and introduces a premature stop codon at position 224. (C) Sanger sequencing of codons 162–164 of PRRT2 in a wild-type subject (left) and an affected subject (right) with c.487C>T (p.Q163X) mutation. (D) Sanger sequencing of codons 265–267 of PRRT2 in a wild-type subject (left) and an affected subject (right) with c.796C>T p.R266W mutation. The mutant sites are indicated by red triangles in B–D. (E) Schematic diagram of PRRT2 gene and wild-type or mutant PRRT2 protein. The three mutations identified in this study are indicated with arrows. PRRT2 gene consists of four exons. PRRT2 protein has two domains: two low complexity segments followed by two transmembrane segments. All three mutations are located upstream of the coding region of the first transmembrane segment of PRRT2 protein. (F) The diagram of chromosome 16 indicating the relative position of PKD locus. The minimal linkage interval of PKD is 19.16 cM between D16S401 and D16S2623 on chromosome 16p12.1-q12.1. The PRRT2 position is indicated with a red triangle.

Mutation in PRRT2 gene

As shown in Fig. 3E, the PRRT2 gene consists of four exons and its protein has two domains: two low complexity segments followed by two transmembrane segments located at amino acids 268–290 and 315–337, respectively. The c.649_650InsC (p.P217fsX7) mutation is a frameshift mutation, which generates a different sequence starting at position 217 and introduces a premature stop codon at position 224, generating a truncated protein with only 223 amino acids. The c.487C>T (p.Q163X) mutation is a nonsense mutation found in the second exon of PRRT2, which substitutes the codon for Q163 (CAG) with a stop codon (TAG) and generates a truncated protein with only 162 amino acids. As a result, both mutant proteins lack the transmembrane segments.

To confirm PRRT2 as the causative gene of PKD, we used Sanger sequencing to screen all members of Families A and B with respective variants (c.649_650InsC in Family A and c.487C>T in Family B). As shown in Fig. 1, all five clinically affected subjects, but none of those who were unaffected in Family A, carried the heterozygous c.649_650InsC mutation. Similarly, all seven patients, but none of the unaffected individuals in Family B, were heterozygous for the c.487C>T mutation. Thus, the mutations in PRRT2 completely co-segregated with the PKD phenotype within these two families.

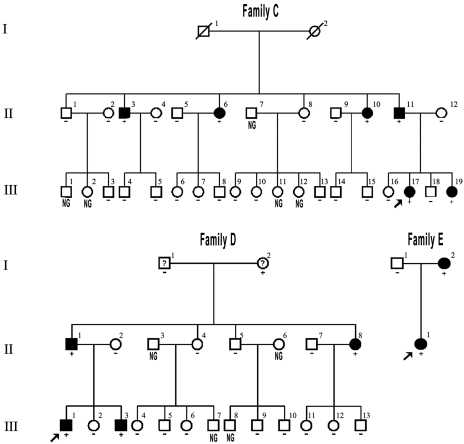

To further study the contribution of PRRT2 to PKD, we sequenced all the exons and flanking introns of the PRRT2 gene of patients and unaffected members in another three unrelated PKD pedigrees. As shown in Fig. 2, the c.649_650InsC (p.P217fsX7) insertion was identified in Families C and D. We also identified a missense mutation c.796C>T (p.R266W) in Family E (Fig. 3D). The c.796C>T (p.R266W) is a missense mutation found in the second exon, causing an arginine to tryptophan substitution at codon 266 (Fig. 3D and E). As shown in Fig. 2, these two variants also co-segregated with the PKD phenotype in Families C–E. Additionally, these three mutations were not detected in 500 unaffected control individuals of matched geographical ancestry, as examined by Sanger sequencing.

Figure 2.

Pedigrees of three additional families with PKD. Subjects in Families C–E were identified by the Arabic numerals above the symbol, and Roman numerals denote the generation. Symbols are the same as in Fig. 1.

Discussion

PKD is a neurological disorder with dystonic posturing, chorea, athetosis, ballism or a combination of these hyperkinetic symptoms (Kertesz, 1967; Goodenough et al., 1978; Demirkiran and Jankovic, 1995; Bruno et al., 2004). We have identified PRRT2 as the causative gene of PKD. PRRT2 had three different mutations, c.487C>T (p.Q163X), c.649_650InsC (p.P217fsX7) and c.796C>T (p.R266W), in five different autosomal dominant PKD families. Several lines of evidence supported the causal role of PRRT2 in PKD: (i) the linkage analysis in two families mapped locus of our PKD families to a pericentromeric region (16p12.1–q12.1) on chromosome 16; (ii) PRRT2 was the only gene with mutations shared by all three patients in the linkage region; (iii) two additional PKD families (Families C and D) carried the insertion mutation (c.649_650InsC), and a third PKD family (Family E) carried a different missense mutation (c.796C>T); (iv) all the mutations co-segregated with the phenotype; and (v) absence of such mutations in 500 normal unaffected individuals of matched geographical ancestry.

Although all of the patients with PKD in our study had mutations in PRRT2, their clinical features, except the core syndrome, varied among families. For instance, the insertion mutation (c.649_650InsC) was found in Families A, C and D, but the clinical manifestation of these three families varied from each other. Family A had two patients (Patients III: 2, III: 5) who presented with infantile convulsion and choreoathetosis, whereas the patients in Families C and D did not report any other history of intermittent neurological disorder. Families C and D also had different presentations. Family C presented with dystonia in lower limbs; however, Family D presented mainly with dystonia in upper limbs. It is possible that other unappreciated gene mutations may contribute to the heterogeneity of PKD phenotypes. Indeed, we also found abundant novel mutations and SNPs in other genes by exome sequencing in every patient with PKD (Table 3).

Table 3.

Identification of the causative gene for PKD from three patients by exome sequencing

| Filter | Sample II: 4 (Family A) | Sample II: 2 (Family B) | Sample II: 4 (Family B) | Shared genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of variants | 98 581 | 90 317 | 101 037 | 9083 |

| Number of NS/SS/ Indel | 10 811 | 10 530 | 10 927 | 2840 |

| Number of NS/SS/ Indel after Filter 1 | 1603 | 1572 | 1607 | 265 |

| Number of NS/SS/ Indel after Filter 2 | 1122 | 1098 | 1162 | 187 |

| Number of NS/SS/ Indel after Filter 3 | 562 | 539 | 736 | 135 |

| SULT1A2(K258N) | CD19(V217M) | AC138894.2-1(N44S) | ||

| NS/SS/indel in 16p12.1-q12.1 | FAM57B(P27A) | LAT(V163M) | PRRT2(Q163*) | |

| ITGAX(Q856H) | PRRT2(Q163*) | CORO1A(V229L) | PRRT2 | |

| PRRT2 (P217fsX7) | ZNF646(G1793E) | |||

| ZNF720 (Indel) | AC136932.2 (Indel) |

‘Shared genes’ indicates the gene mutations occurred in all three samples. In the step of Filter 1, we first removed the NS/SS/Indel variants reported in the dbSNP129. Then, the NS/SS/Indel variants reported in the eight previously exome-sequenced HapMap samples (‘HapMap 8’) were further removed in Filter 2. Consequently, the NS/SS/Indel variants reported in the 1000 Genome Project were removed in Filter 3; * = stop codon.

PRRT2 is a member of the transmembrane protein family, including PRRT1-4. Interestingly, two of the mutations identified in this study (p.Q163X and p.P217fsX7) resulted in truncated PRRT2 proteins lacking the transmembrane domain. These truncated proteins cannot anchor to the membrane and may be loss-of-function. However, similar to some soluble membrane receptors, the soluble PRRT2 may still preserve binding ability to the interactive proteins or ligands and attenuate their binding to the wild-type PRRT2, i.e. dominant negative effect (Celli et al., 1998). Nevertheless, the exact underlying molecular mechanism as to how these mutations caused PKD, either haploinsufficiency or dominant negative effect, requires further investigation.

There is a limited amount of research regarding the function of PRRT2; however, some indirect evidence suggested its role in the pathogenesis of PKD. First, PRRT2 was found to be mainly expressed in the basal ganglia (http://human.brain-map.org), a brain area possibly involved in the PKD pathogenesis (Hamano et al., 1995; Hayashi et al., 1997; Ko et al., 2001; Shirane et al., 2001; Volonte et al., 2001; Iwasaki et al., 2004). Secondly, SNAP25, an interactive protein of PRRT2, is also expressed in the brain, especially the basal ganglia (Stelzl et al., 2005). Third, SNAP25 participates in the regulation of neurotransmitter release (Graham et al., 2002). Finally, recent research studies have revealed that SNAP25 might be involved in the aetiology of the attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (Gizer et al., 2009; Banaschewski et al., 2010), whereas the core features of PKD are also a paroxysmal hyperkinetic (Demirkiran and Jankovic, 1995).

Since the first description by Kertesz (1967), PKD has been widely studied. However, the mechanism is still unclear. Here, we have identified PRRT2 as the first causative gene for PKD, warranting future research to understand the pathogenesis of PKD.

Funding

The Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (973 Program) (grant number 2011CB510000) and the State Key Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81130021) was provided by Department of Neurology, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University. (They mainly completed the work about Family A, Family E, and exome analysis). The Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (973 Program) (grant number 2011CB504104) and Key Discipline program of Shanghai Municipality (grant number S30202) were provided by Department of Neurology & Institute of Neurology, Ruijin Hospital. (They mainly completed the work about Family B, and linkage analysis). National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 30671154) was provided by Department of Neurology, the First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University. (They mainly completed the work about Family C, Family D, and sequencing analysis).

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to all the patients and family members for their generous participation in this work.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- PKD

paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesias

- PRRT2

proline-rich transmembrane protein 2

- NS/SS/Indel

non-synonymous/splice acceptor and donor site/insertions or deletions

- SNP

single-nucleotide polymorphism

References

- Banaschewski T, Becker K, Scherag S, Franke B, Coghill D. Molecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an overview. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19:237–57. doi: 10.1007/s00787-010-0090-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett LB, Roach ES, Bowcock AM. A locus for paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia maps to human chromosome 16. Neurology. 2000;54:125–30. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakeley J, Jankovic J. Secondary paroxysmal dyskinesias. Mov Disord. 2002;17:726–34. doi: 10.1002/mds.10178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno MK, Hallett M, Gwinn-Hardy K, Sorensen B, Considine E, Tucker S, et al. Clinical evaluation of idiopathic paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia: new diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 2004;63:2280–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000147298.05983.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celli G, LaRochelle WJ, Mackem S, Sharp R, Merlino G. Soluble dominant-negative receptor uncovers essential roles for fibroblast growth factors in multi-organ induction and patterning. EMBO J. 1998;17:1642–55. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi M, Scholl UI, Ji W, Liu T, Tikhonova IR, Zumbo P, et al. Genetic diagnosis by whole exome capture and massively parallel DNA sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19096–101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910672106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca-Leon E, Cormand B, Thomson T, Macaya A. Paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia and generalized seizures: clinical and genetic analysis in a Spanish pedigree. Neuropediatrics. 2002;33:288–93. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-37079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirkiran M, Jankovic J. Paroxysmal dyskinesias: clinical features and classification. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:571–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dib C, Faure S, Fizames C, Samson D, Drouot N, Vignal A, et al. A comprehensive genetic map of the human genome based on 5,264 microsatellites. Nature. 1996;380:152–4. doi: 10.1038/380152a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gizer IR, Ficks C, Waldman ID. Candidate gene studies of ADHD: a meta-analytic review. Hum Genet. 2009;126:51–90. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0694-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenough DJ, Fariello RG, Annis BL, Chun RW. Familial and acquired paroxysmal dyskinesias. A proposed classification with delineation of clinical features. Arch Neurol. 1978;35:827–31. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1978.00500360051010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham ME, Washbourne P, Wilson MC, Burgoyne RD. Molecular analysis of SNAP-25 function in exocytosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;971:210–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamano S, Tanaka Y, Nara T, Nakanishi Y, Shimizu M. Paroxysmal kinesigenic choreoathetosis associated with prenatal brain damage. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1995;37:401–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.1995.tb03342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi R, Hanyu N, Yahikozawa H, Yanagisawa N. Ictal muscle discharge pattern and SPECT in paroxysmal kinesigenic choreoathetosis. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1997;37:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser MK, Soland VL, Bhatia KP, Quinn NP, Marsden CD. Paroxysmal kinesigenic choreoathetosis: a report of 26 patients. J Neurol. 1999;246:120–6. doi: 10.1007/s004150050318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki Y, Nakamura T, Hamada K. [Late-onset of idiopathic paroxysmal kinesigenic choreoathetosis: a case report] Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2004;44:365–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz A. Paroxysmal kinesigenic choreoathetosis. An entity within the paroxysmal choreoathetosis syndrome. Description of 10 cases, including 1 autopsied. Neurology. 1967;17:680–90. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.7.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi T, Nomura M, Tomita H, Harada N, Kanai K, Konishi T, et al. Paroxysmal kinesigenic choreoathetosis (PKC): confirmation of linkage to 16p11-q21, but unsuccessful detection of mutations among 157 genes at the PKC-critical region in seven PKC families. J Hum Genet. 2007;52:334–41. doi: 10.1007/s10038-007-0116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko CH, Kong CK, Ngai WT, Ma KM. Ictal (99m)Tc ECD SPECT in paroxysmal kinesigenic choreoathetosis. Pediatr Neurol. 2001;24:225–7. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(00)00257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathrop GM, Lalouel JM. Easy calculations of lod scores and genetic risks on small computers. Am J Hum Genet. 1984;36:460–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–95. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Li Y, Kristiansen K, Wang J. SOAP: short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:713–4. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Zhu H, Ruan J, Qian W, Fang X, Shi Z, et al. De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Res. 2010;20:265–72. doi: 10.1101/gr.097261.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotze T, Jankovic J. Paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesias. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2003;10:68–79. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9091(02)00012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden CD. Paroxysmal choreoathetosis. Adv Neurol. 1996;70:467–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng SB, Buckingham KJ, Lee C, Bigham AW, Tabor HK, Dent KM, et al. Exome sequencing identifies the cause of a mendelian disorder. Nat Genet. 2010;42:30–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perona-Moratalla AB, Argandona L, Garcia-Munozguren S. [Paroxysmal dyskinesias] Rev Neurol. 2009;48(Suppl 1):S7–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochette J, Roll P, Szepetowski P. Genetics of infantile seizures with paroxysmal dyskinesia: the infantile convulsions and choreoathetosis (ICCA) and ICCA-related syndromes. J Med Genet. 2008;45:773–9. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.059519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirane S, Sasaki M, Kogure D, Matsuda H, Hashimoto T. Increased ictal perfusion of the thalamus in paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:408–10. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.3.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spacey SD, Valente EM, Wali GM, Warner TT, Jarman PR, Schapira AH, et al. Genetic and clinical heterogeneity in paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia: evidence for a third EKD gene. Mov Disord. 2002;17:717–25. doi: 10.1002/mds.10126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelzl U, Worm U, Lalowski M, Haenig C, Brembeck FH, Goehler H, et al. A human protein-protein interaction network: a resource for annotating the proteome. Cell. 2005;122:957–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swoboda KJ, Soong B, McKenna C, Brunt ER, Litt M, Bale JF, Jr, et al. Paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia and infantile convulsions: clinical and linkage studies. Neurology. 2000;55:224–30. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szepetowski P, Rochette J, Berquin P, Piussan C, Lathrop GM, Monaco AP. Familial infantile convulsions and paroxysmal choreoathetosis: a new neurological syndrome linked to the pericentromeric region of human chromosome 16. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:889–98. doi: 10.1086/514877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang BS, Luo W, Xia K, Xiao JF, Jiang H, Shen L, et al. A new locus for autosomal dominant Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2 (CMT2L) maps to chromosome 12q24. Hum Genet. 2004;114:527–33. doi: 10.1007/s00439-004-1102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita H, Nagamitsu S, Wakui K, Fukushima Y, Yamada K, Sadamatsu M, et al. Paroxysmal kinesigenic choreoathetosis locus maps to chromosome 16p11.2-q12.1. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:1688–97. doi: 10.1086/302682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente EM, Spacey SD, Wali GM, Bhatia KP, Dixon PH, Wood NW, et al. A second paroxysmal kinesigenic choreoathetosis locus (EKD2) mapping on 16q13-q22.1 indicates a family of genes which give rise to paroxysmal disorders on human chromosome 16. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 10):2040–5. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.10.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volonte MA, Moresco RM, Gobbo C, Messa C, Carpinelli A, Rizzo G, et al. A PET study with [11-C]raclopride in Parkinson's disease: preliminary results on the effect of amantadine on the dopaminergic system. Neurol Sci. 2001;22:107–8. doi: 10.1007/s100720170067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Sun W, Zhu X, Li L, Du T, Mao W, et al. Paroxysmal kinesigenic choreoathetosis: evidence of linkage to the pericentromeric region of chromosome 16 in four Chinese families. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:800–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JL, Yang X, Xia K, Hu ZM, Weng L, Jin X, et al. TGM6 identified as a novel causative gene of spinocerebellar ataxias using exome sequencing. Brain. 2010;133:3510–8. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]