ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE

To report chronic opioid therapy discontinuation rates after five years and identify factors associated with discontinuation.

METHODS

Medical and pharmacy claims records from January 2000 through December 2005 from a national private health network (HealthCore), and Arkansas (AR) Medicaid were used to identify ambulatory adult enrollees who had 90 days of opioids supplied. Recipients were followed until they discontinued opioid prescription fills or disenrolled. Kaplan Meier survival models and Cox proportional hazards models were estimated to identify factors associated with time until opioid discontinuation.

RESULTS

There were 23,419 and 6,848 chronic opioid recipients followed for a mean of 1.9 and 2.3 years in the HealthCore and AR Medicaid samples. Over a maximum follow up of 4.8 years, 67.0% of HealthCore and 64.9% AR Medicaid recipients remained on opioids. Recipients on high daily opioid dose (greater than 120 milligrams morphine equivalent (MED)) were less likely to discontinue than recipients taking lower doses: HealthCore hazard ratio (HR) = 0.66 (95%CI: 0.57–0.76), AR Medicaid HR = 0.66 (95%CI: 0.50–0.82). Recipients with possible opioid misuse were also less likely to discontinue: HealthCore HR = 0.83 (95%CI: 0.78–0.89), AR Medicaid HR = 0.78 (95%CI: 0.67–0.90).

CONCLUSIONS

Over half of persons receiving 90 days of continuous opioid therapy remain on opioids years later. Factors most strongly associated with continuation were intermittent prior opioid exposure, daily opioid dose ≥ 120 mg MED, and possible opioid misuse. Since high dose and opioid misuse have been shown to increase the risk of adverse outcomes special caution is warranted when prescribing more than 90 days of opioid therapy in these patients.

KEY WORDS: opioids, opioid misuse, persistence, discontinuation

INTRODUCTION

The long-term efficacy and safety of chronic opioid therapy (COT) for chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP) is not well established. In randomized controlled trials, oral opioids offer improved pain relief for musculoskeletal and neuropathic pain versus placebo over weeks to months.1 Efficacy data on longer term opioid use is limited to open label extensions of short term trials. These show that discontinuation of opioids is common, generally due to side effects or lack of efficacy.2–4 Professional pain guidelines note limitations in the evidence supporting COT and potential serious harms, but state that COT can “be effective therapy for carefully selected and monitored patients”.2,5

Use of COT for CNCP has dramatically increased over the past three decades.6–8 There has been a parallel increase in abuse of prescribed opioids7,9 with prescription opioid abuse the fastest growing form of drug abuse9 and prescription opioids most frequently associated with accidental fatal drug overdose.10 Evidence linking prescribed opioid dose with risk of adverse outcomes is emerging.11,12

It is not known how long COT recipients generally continue opioid therapy or who is likely to continue COT long term. Electronic health care data offers a unique opportunity to investigate duration of COT within large clinical populations over long time periods. In this study, we report opioid discontinuation rates of COT users over a follow-up period of up to five years and investigate factors associated with discontinuation in a geographically diverse national sample of COT recipients with commercial insurance and a state-based Medicaid sample.

METHODS

Data Source

Data were obtained from claims records from January 2000 through December 2005 from HealthCore, the country’s largest private health network, and Arkansas Medicaid. HealthCore data included plans from 14 states in the Western, Mid-Western, and South-Eastern United States. These two populations were chosen to assess the range of opioid use and its consequences in disparate populations. A waiver of the requirements for informed consent was granted from the Human Subjects Review Committees at participating institutions.

Study Sample

The analytical sample consisted of adult enrollees with continuous chronic opioid use. Inclusion Criteria: 1) At least one chronic opioid use episode with > 90 days of opioid supplied in any 6 month period between 3/6/2001 and 12/31/2004. Continuous chronic opioid use was defined as opioid use without a 32 day gap occurring between fill dates. The first day of the chronic opioid use episode was defined as the index date. 2) Continuous enrollment for 24 months, 12 months before and after the index date. Exclusion Criteria: 1) Any claim for long-term or hospice care, 2) Cancer diagnosis in the year prior to the index date (other than non-melanoma skin cancer). 23,419 enrollees in HealthCore and 6,848 in Arkansas Medicaid met these criteria. Details of the HealthCore and Arkansas Medicaid populations and their opioid use have been described elsewhere.8,13

Opioid Discontinuation

Subjects were followed from their first chronic opioid use episode until disenrollment, death, opioid discontinuation, or until the study period ended. Opioid discontinuation was defined as a period of at least 182 days of enrollment without any opioid prescription claims from the run out date (prescription fill date + days supplied) of the last prescription.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Variables

Data on sociodemographic variables came from the recipient enrollment files. For the HealthCore sample, census tracts and state level codes were used to describe minority, education, and income characteristics of the recipient’s area of residence. In each case, we coded whether a recipient came from a tract above or below the median value for the country. Clinical characteristics of the recipients based on ICD-9-CM codes were collected from claims records in the 12 months preceding the index date. The Charlson comorbidity index14 a common measure which weights 22 comorbidities that has been adapted for use with administrative data was used as a measure of overall medical comorbidity. Arthritis/joint pain, back pain, neck pain, and headache—the most common diagnoses for long-term opioid use in a general medical population8—were selected as tracer pain diagnoses, and tracked individually. The count of other (“non-tracer”) pain diagnoses: extremity pain, abdominal pain, chest pain, kidney stones/gallstones, pelvic pain, rheumatoid arthritis, fractures, neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, and temperomandibular joint pain was used as a measure of non-CNCP pain. Mental health and substance use disorders were grouped based on ICD-9-CM diagnoses using validated grouping software developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality15: adjustment disorders, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, personality disorders, and substance use disorders. Mood disorders were further classified as unipolar depression or bipolar disorder, and substance use disorders were further classified as alcohol use disorder, non-opioid drug use disorder, or opioid use disorder. Adjustment, anxiety, mood and personality disorders were summed to create a variable identifying the number of mental health disorder types.

Medication Variables

Data for medication use were collected for the 12-month pre-index and the 6-month post-index period. Morphine equivalent dose (MED) in the initial 6 month COT episode was calculated by multiplying the quantity of each prescription by the opioid strength, and multiplying this by a morphine equivalent conversion factor.8 Average opioid dose per day supplied was calculated by adding the total morphine equivalents for the three major opioid groups and dividing by the sum of the total days supply. If the total days supply exceeded the number of days in the period (180 days), suggesting concurrent use of different opioid types, daily dose was calculated by dividing total dose dispensed by 180 days. Mean daily dose was trichotomized: daily dose < median MED dose in each sample (33 mg MED HealthCore; 36 mg MED AR Medicaid), median MED ≤ daily dose < 120 mg, daily dose ≥ 120 mg MED. 120 mg MED was chosen because Washington State and Centers for Disease Control guidelines urge special precautions for doses greater than 120 mg MED. Types of opioid received were determined based on opioid class (defined by DEA schedule and duration of action). Subjects were coded as receiving a particular opioid class if they received at least 30 days supply of that class within the six-month period. Seven mutually exclusive opioid categories were derived: (1) Non-Schedule II short-acting (eg: hydrocodone/acetaminophen), (2) Schedule II short-acting (eg: morphine), (3) Schedule II long-acting (eg: oxycodone controlled release), (4) Non-schedule II plus Schedule II short acting, (5) Schedule II short-acting plus Schedule II long-acting, (6) Non-Schedule II short-acting plus Schedule II long-acting, and (7) all three opioid types. Intermittent prior exposure to opioids was defined as having 30 or more days of opioid supplied in the 6-month period immediately prior to the COT episode. We used data on days supply and measures of any exposure for the following non-opioid medications, often used in the treatment of patients with CNCP: sedative/hypnotics (mainly benzodiazepines, but also other hypnotic drugs), muscle relaxants, stimulants, Cox-II inhibitors, anticonvulsants, tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin or serotonin-norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitors (SSRI/SNRI), and other analgesic medications. An opioid misuse score based on excess days supplied of short- and long-acting opioids, the number of unique opioid pharmacies and opioid prescribers was calculated in the six-month post-index period.16 The misuse score was trichotomized with misuse scores of 0 to 1 representing the lowest probability of opioid misuse, 2–3 representing possible misuse, and scores of 4 or greater representing the highest probability of misuse.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic and clinical variables. We used Kaplan Meier survival models to estimate unadjusted time to discontinuation. Stepwise Cox proportional hazards models were estimated to identify factors associated with time until opioid discontinuation. Variables were classified into 6 groups, and the groups were ordered as follows: (1) demographic variables, (2) misuse variables, (3) pain diagnoses and Charlson index, (4) pharmacological variables, and (5) mental health/substance abuse diagnoses. Within each group, we performed a model selection process to choose the “final model” using the STEPWISE option in SAS 9.1 with a criteria of p < =0.05 to select and retain variables in the model.17 For each group, the models always retained the variables in the final model from the previous group(s). For example, if age was included in the final model of group (1), then it was retained in subsequent models evaluating variables in groups (2), (3), (4), and (5).

RESULTS

Of the 23,419 continuous chronic opioid recipients in HealthCore, 58.7% were female, 12.4% were 65 years of age or older and 55.2% had one or more tracer pain diagnoses (Table 1). The AR Medicaid sample of 6,848 chronic opioid recipients were comprised of more elderly (23.2%) and females (72.6%) (p < 0.001). The maximum follow-up time was 4.82 years in both samples and the median and mean follow-up times were 1.69 and 1.93 years in the HealthCore sample and 1.99 and 2.25 years in the AR Medicaid sample. The AR Medicaid sample had more tracer pain diagnoses, mental health diagnoses, and medical comorbidities (Charlson score) than the HealthCore sample (p < 0.05). Use of sedatives and non-opioid drugs with potential analgesic properties were similar in the two samples. In both samples, approximately 80% of chronic opioid users used schedule III and IV opioids (non-class II) as their primary opioid in the first six months; 3–4% of the samples used more than 120 mg MED per day. The mean days supplied of opioids in the six-month post-index period were 148 and 143 days in the HealthCore and AR Medicaid samples reflecting near daily consumption. Over half the persons in each sample received 30 or more days supply of opioids in the prior six months. Possible or probable misuse in the first six months (misuse scores ≥ 2) occurred in 16.7% and 12.3% of the HealthCore and AR Medicaid samples.

Table 1.

Demographic, Comorbidity, Drug and Medical Use Variables HealthCore and Arkansas Medicaid 2000 – 2005

| Variables | Categories | HealthCore | AR Medicaid | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 23,419 | N = 6,848 | |||

| Age | 18–30 | 1282 (5.5%) | 518 (7.6%) | <0.001 |

| 31–40 | 4001 (17.1%) | 1186 (17.3%) | ||

| 41–50 | 7305 (31.2%) | 1730 (25.3%) | ||

| 51–64 | 7927 (33.8%) | 1822 (26.6%) | ||

| > = 65 | 2904 (12.4%) | 1592 (23.2%) | ||

| Female | 13739 (58.7%) | 4969 (72.6%) | <0.001 | |

| Index year | 2001 | 5678 (24.2%) | 1718 (25.1%) | <0.001 |

| 2002 | 6462 (27.6%) | 1662 (24.3%) | ||

| 2003 | 6308 (26.9%) | 1609 (23.5%) | ||

| 2004 | 4971 (21.2%) | 1859 (27.1%) | ||

| Race – black* | --- | 1421 (20.8%) | --- | |

| From census tract with: | ||||

| Predominantly some college† | 12448 (56.8%) | --- | --- | |

| Predominantly Minority† | 8624 (39.3%) | --- | ||

| Median Income or Higher† | 10749 (49.0%) | --- | ||

| Pre-index opioid days supplied > 30 | 12595 (53.8%) | 4165 (60.8%) | <0.001 | |

| CNCP type | None | 10501 (44.8%) | 1865 (27.2%) | <0.001 |

| back pain only | 3949 (16.9%) | 1200 (17.5%) | ||

| neck pain only | 629 (2.7%) | 105 (1.5%) | ||

| joint pain only | 1648 (7.0%) | 929 (13.6%) | ||

| headache only | 1305 (5.6%) | 312 (4.6%) | ||

| 2 or more CNCP | 5387 (23.0%) | 2437 (35.6%) | ||

| Charlson score | Mean(SD) | 0.4 (1) | 1.1 (1) | <0.001 |

| Non-tracer pain | 0 | 9666 (41.3%) | 1746 (25.5%) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 6634 (28.3%) | 1863 (27.2%) | ||

| 2-3 | 6066 (25.9%) | 2587 (37.8%) | ||

| > = 4 | 1053 (4.5%) | 652 (9.5%) | ||

| Opioid type | non-class II only | 18639 (79.6%) | 5576 (81.4%) | <0.001 |

| class II short only | 500 (2.1%) | 179 (2.6%) | ||

| class II long only | 1042 (4.4%) | 284 (4.1%) | ||

| non-class II + class II short | 761 (3.2%) | 237 (3.5%) | ||

| non-class II + class II long | 1578 (6.7%) | 370 (5.4%) | ||

| class II short + long | 538 (2.3%) | 127 (1.9%) | ||

| All 3 types | 361 (1.5%) | 75 (1.1%) | ||

| Opioid daily dose | < median | 12835 (54.8%) | 3844 (56.1%) | <0.001 |

| median-120 | 9595 (41.0%) | 2788 (40.7%) | ||

| >120 | 989 (4.2%) | 216 (3.2%) | ||

| Misuse Score | No misuse (0–1) | 19474 (83.2%) | 6003 (87.7%) | <0.001 |

| Possible misuse (2–3) | 3399 (14.5%) | 747 (10.9%) | ||

| Probable Misuse (4+) | 523 (2.2%) | 98 (1.4%) | ||

| Pre-Index Pharmacological Variables | ||||

| NSAIDS/COXII | 3481 (14.9%) | 975 (14.2%) | 0.198 | |

| Muscle relaxants | 7550 (32.2%) | 2367 (34.6%) | <0.001 | |

| Sedative/hypnotics | 9024 (38.5%) | 2693 (39.3%) | 0.236 | |

| SSRI/SNRI | 8550 (36.5%) | 2352 (34.3%) | <0.001 | |

| Stimulants | 496 (2.1%) | 63 (0.9%) | <0.001 | |

| Antimigraine | 1979 (8.5%) | 164 (2.4%) | <0.001 | |

| Anticonvulsants | 3106 (13.3%) | 1007 (14.7%) | <0.001 | |

| Any of above RX use pre-index | 17419 (74.4%) | 5252 (76.7%) | <0.001 | |

| Post-Index Pharmacological Variables | ||||

| NSAIDS/COXII | 3157 (13.5%) | 613 (9.0%) | <0.001 | |

| Muscle relaxants | 8111 (34.6%) | 2362 (34.5%) | 0.827 | |

| Sedative/hypnotics | 9768 (41.7%) | 2782 (40.6%) | 0.109 | |

| SSRI/SNRI | 8723 (37.2%) | 2285 (33.4%) | <0.001 | |

| Stimulants | 522 (2.2%) | 71 (1.0%) | <0.001 | |

| Antimigraine | 1703 (7.3%) | 130 (1.9%) | <0.001 | |

| Anticonvulsants | 3814 (16.3%) | 999 (14.6%) | 0.001 | |

| Any of Above RX use post-index | 18602 (79.4%) | 5399 (78.8%) | 0.289 | |

| Adjustment disorder | 439 (1.9%) | 134 (2.0%) | 0.661 | |

| Anxiety disorder | 1777 (7.6%) | 1203 (17.6%) | <0.001 | |

| Mood disorder | 2758 (11.8%) | 1544 (22.5%) | <0.001 | |

| Personality disorder | 46 (0.2%) | 135 (2.0%) | <0.001 | |

| Substance disorder | 547 (2.3%) | 427 (6.2%) | <0.001 | |

| Miscellaneous Psychiatric disorder | 611 (2.6%) | 125 (1.8%) | <0.001 | |

| Alcohol use disorder | 309 (1.3%) | 225 (3.3%) | <0.001 | |

| Opioid use disorder | 130 (0.6%) | 36 (0.5%) | 0.772 | |

| Non-opioid drug use disorder | 242 (1.0%) | 235 (3.4%) | <0.001 | |

*Race was only available for AR Medicaid

†Based on Geographic Area of Residence

CNCP – Chronic Non-Cancer Pain

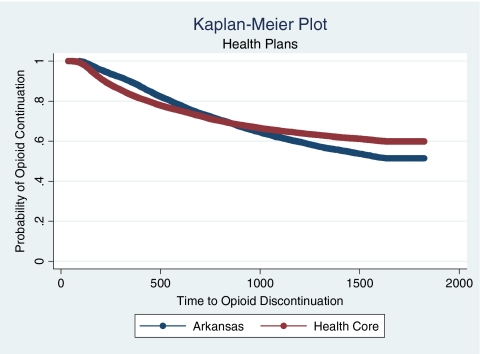

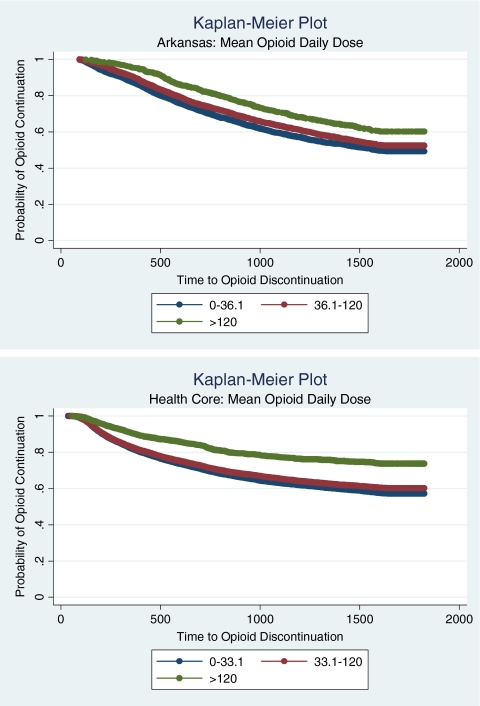

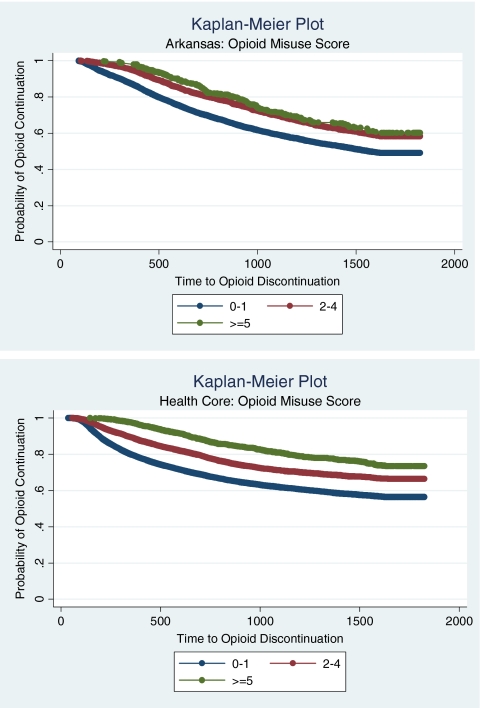

Sixty seven percent and 64.9% of HealthCore and AR Medicaid chronic opioid patients remained on opioids before they became censored (Fig. 1). In both samples, the most significant and consistent predictors of opioid discontinuation were mean daily opioid dose and prior intermittent opioid use [Table 2]. Persons on average daily doses greater than 120 MED were 34% less likely to discontinue than persons taking doses at or below the median daily dose in the both samples (Fig. 2). Persons with a misuse score of ≥ 2 were about 20% less likely to discontinue than persons with a misuse score of < 2 in the HealthCore sample (Fig. 3). Persons with opioid exposure prior to beginning their COT were 24–45% less likely to discontinue as those without 30 days or more of exposure. For AR Medicaid, the types of opioid used were not associated with discontinuation. However, in HealthCore persons prescribed only short acting Schedule II opioids were significantly more likely to continue than persons prescribed only schedule III and IV opioids.

Figure 1.

Days until opioid discontinuation by health plan type, 2001–2005.

Table 2.

Cox Proportional Hazard Model Results of Time until Opioid Discontinuation HealthCore and Arkansas Medicaid, 2000–2005

| Variables | HEALTHCORE | ARKANSAS MEDICAID | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | |

| Age: 18–30 | 1.11 | [0.99, 1.25] | 1.04 | [0.87, 1.23] |

| Age: 31–40 | 1.03 | [0.95, 1.13] | 0.88 | [0.77, 1.01] |

| Age: 41–50 | 0.90 | [0.83, 0.97] | 0.77 | [0.69, 0.87] |

| Age: 51–64 | 0.89 | [0.82, 0.96] | 0.80 | [0.72, 0.90] |

| Referent: Age: 65+ | ||||

| Female | 0.85 | [0.81, 0.89] | --- | --- |

| Referent: Male | ||||

| Index year: 2002 | --- | --- | 0.93 | [0.84, 1.02] |

| Index year: 2003 | --- | --- | 0.77 | [0.69, 0.87] |

| Index year: 2004 | --- | --- | 0.50 | [0.43, 0.58] |

| Referent: Index year 2001 | ||||

| Some college or above | 1.11 | [1.06, 1.16] | --- | --- |

| Referent: high school or less | ||||

| Ethnic minority | 1.04 | [0.99, 1.10] | --- | --- |

| Referent: non-minority | ||||

| Misuse score 2-3 | 0.83 | [0.78, 0.89] | 0.78 | [0.67, 0.90] |

| Misuse score > =4 | 0.80 | [0.67, 0.95] | 0.89 | [0.61, 1.25] |

| > = 30 opioids days in pre-index period | 0.55 | [0.53, 0.58] | 0.76 | [0.70, 0.82] |

| CNCP: back only | --- | --- | 0.98 | [0.87, 1.11] |

| CNCP: neck only | --- | --- | 0.84 | [0.60, 1.15] |

| CNCP: joint only | --- | --- | 1.01 | [0.89, 1.15] |

| CNCP: head only | --- | --- | 1.01 | [0.82, 1.23] |

| CNCP: 2 or more | --- | --- | 0.82 | [0.73, 0.91] |

| Referent: No CNCP | ||||

| Charlson score | 0.97 | [0.95, 1.00] | 1.06 | [1.03, 1.09] |

| class II short only | 0.72 | [0.59, 0.86] | --- | --- |

| class II long only | 1.14 | [1.01, 1.28] | --- | --- |

| non-class II + class II short | 1.08 | [0.94, 1.24] | --- | --- |

| non-class II + class II long | 1.15 | [1.05, 1.27] | --- | --- |

| class II short + long | 0.99 | [0.83, 1.17] | --- | --- |

| All 3 types | 1.06 | [0.86, 1.30] | --- | --- |

| Referent: non – class II only | ||||

| Opioid daily dose: median-120 | 0.92 | [0.88, 0.97] | 0.87 | [0.80, 0.94] |

| Opioid daily dose: >120 | 0.66 | [0.57, 0.76] | 0.66 | [0.50, 0.85] |

| Referent: Opioid daily dose < median | ||||

| RX: pre-index sedative/hypnotics | 0.89 | [0.85, 0.94] | --- | --- |

| RX: post-index Cox-2 s | 1.08 | [1.01, 1.15] | --- | --- |

| RX: post-index muscle relaxants | 0.91 | [0.87, 0.96] | --- | --- |

| RX: post-index SSRI/SNRIs | 0.94 | [0.89, 0.99] | ||

| RX: post-index anti-migraine drugs | 0.82 | [0.74, 0.91] | --- | --- |

| Referent: No exposure to other analgesic drugs | ||||

| MH: personality disorder | 1.76 | [1.05, 2.74] | --- | --- |

| MH: mood disorder | --- | --- | 1.15 | [1.04, 1.27] |

| Referent: No mental health diagnoses | ||||

| SA: alcohol | 1.22 | [1.00, 1.47] | 1.33 | [1.06, 1.64] |

Referent: No substance abuse diagnoses

Cox2s-Cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors; SSRIs—Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors; SNRIs – Serotonin–Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors

Figure 2.

Days until opioid discontinuation by mean daily opioid dose for Arkansas Medicaid and healthcore, 2001–2005.

Figure 3.

Days until opioid discontinuation by misuse score for Arkansas Medicaid and healthcore, 2001–2005.

Demographic factors were not strongly associated with discontinuation, though persons between the ages of 41 and 64 were approximately 10% less likely to discontinue than elderly counterparts. Persons with multiple tracer pain conditions were 18% less likely to discontinue than persons without any tracer conditions in AR Medicaid. Discontinuation was not associated with the number of non-tracer painful conditions in either sample. Persons with a personality disorder were 76% more likely to discontinue in HealthCore than those without any personality disorders. An alcohol abuse diagnosis in AR Medicaid and HealthCore was associated with a greater likelihood of discontinuation,; however, an opioid abuse diagnosis was not associated with discontinuation in either sample (variable not entered in stepwise selection process). Use of sedative hypnotics, muscle relaxants, antidepressants, and anti-migraine medications was associated with a lower likelihood of discontinuation in HealthCore, but not in AR Medicaid.

DISCUSSION

Among this large and diverse sample of continuous chronic opioid users, approximately two thirds of persons remained on opioid therapy years later. This suggests that continuous opioid therapy for at least three months often leads to a course of opioid therapy that persists over years.

Previous evidence on COT duration is limited to withdrawal rates from extensions of open label clinical trials, where it has been reported that 32% discontinue due to adverse events and 12% due to inadequate pain relief over a 6- to 18-month time period.1 However, professional COT guidelines address discontinuation largely as a consequence of aberrant drug behaviors.2 There are no randomized trials or controlled observational studies comparing outcomes with continuation vs. discontinuation of COT over extended periods. In our current study, we are unable to distinguish between patients who discontinue because of improved pain and function vs. those who discontinue because of side effects, analgesic failure, or aberrant drug behaviors. What can be learned from our data is that once a person has transitioned to COT, more than half will likely continue to use opioids a half a decade later under existing practice patterns. This is an important point for clinicians to consider and discuss with patients prior to deciding on a regimen of COT.

Prior intermittent opioid use had the strongest association with opioid discontinuation, even though we required at least a 32-day gap between any prior intermittent use and the beginning of their COT therapy, so that the start point of their COT could be clearly defined. Over half of persons who go on to receive COT, have intermittent use beforehand, implying that many persons who are prescribed intermittent opioids are gradually titrated up to daily or near-daily COT.

Other strong predictors of opioid continuation were daily opioid doses over 120 mg MED and possible opioid misuse. The effect of high dose opioids on discontinuation is consistent with a study of workers with back injury where the maximum dose of opioids in the first three months after injury was the strongest prognostic factor for continued opioid use at one year.18 Though the mechanisms of opioid analgesic tolerance are still unclear,19 the association between high daily doses and longer durations suggest that opioid tolerance and withdrawal symptoms may drive escalating doses and longer durations of therapy. Opioid dose may be a marker for more difficult to treat pain conditions or other comorbidities; however, it remained significant in multivariable models that attempted to control for a range of comorbidities. This association of high dose COT and continuation is of concern since prescribed daily opioid dose over 100 mg MED has been associated with increased risks of overdose11 fracture,12 dependence 13 and death.20

Patients with possible opioid misuse were also significantly less likely to discontinue opioid therapy, but probable misuse was not significantly associated with longer durations of opioid therapy in the AR Medicaid sample; this is likely due to the relatively small number of patients (n = 98) in this category. Our misuse score is derived from excess days supplied of opioid, multiple opioid prescribers and multiple opioid pharmacies and may reflect “doctor shopping”, diversion or other aberrant medication behaviors; this measure has been shown to be associated with substance abuse diagnoses,16 but may also reflect legitimate care delivered by multiple providers. Nevertheless, the 20% increase in the time until opioid discontinuation associated with possible misuse in both samples is worrisome since higher daily opioid doses and opioid misuse have been associated with adverse outcomes of COT. Overall, these data show that approximately 1 in 7 persons on COT potentially misuse opioids and these patients take opioids for durations that are measured in years. With the increase in prescription monitoring programs throughout the U.S., some of the measures with which our misuse score were derived can be monitored in order to deter aberrant opioid behaviors but future research will be needed to assess the effectiveness of these strategies.

Recipient demographics had modest and variable effects on the time until discontinuation. Younger persons 18–30 years old were relatively more likely to discontinue than middle aged persons. This might be due to the increased risk for misuse and abuse of opioids among younger persons,13,21 which may lead to greater vigilance of prescribers and pharmacists or may reflect less persistent and severe pain. Persons with prior non-opioid drug or alcohol abuse were also more likely to discontinue, which might also suggest greater vigilance in this higher risk group. The lack of consistent associations between most mental health disorders and discontinuation is surprising given previous studies demonstrating increased use of COT for CNCP among persons with mental health disorders and substance use disorders.22–26 Nearly 40% of the COT users in both samples also had a sedative hypnotic prescribed and in the Health Core sample, these drugs were associated with a lower discontinuation rate. The high rate of co-prescribing of sedative hypnotics to COT raises safety concerns as benzodiazepines are the most frequent co-intoxicants in opioid related deaths.27

Although long-acting opioids are often recommended in COT guidelines,2,5 we found that only 13–15% of COT recipients used a long acting opioid and did not find that long-acting opioids were associated with COT continuation. In the HealthCore sample, recipients using only short-acting schedule II opioids in the first six months of their opioid episode were less likely to discontinue COT. Furthermore, over three quarters of COT recipients received non-schedule II opioids as their primary opioid in the initial six months of COT. While recent federal efforts in responding to the prescription drug abuse problem have focused on the risks of long-acting opioids,28 our data suggest that this would only address 1 in 6 COT recipients.

These data should be interpreted in light of the following limitations to our study. First, all the recipients in this sample were prescribed a minimum of 90 days of supply of continuous opioid therapy over a 6 month period. Rates of discontinuation are likely higher for persons exposed to shorter or less continuous opioid therapy. Future work could determine if there is a duration threshold, beyond which discontinuation becomes much less likely. Second, our definition of discontinuation relied on the absence of any opioid prescription claims for at least 182 days. Recipients who used opioids intermittently or had gaps of less than 182 days between opioid prescriptions were not classified as discontinuations. This long period to define discontinuation minimizes, but does not eliminate the chances that a person continued to use opioids that they “stockpiled”. The data were drawn from two disparate sources, a geographically dispersed commercial population and a single state’s Medicaid population and it is unknown to what extent these findings can be generalized to other settings. We found differences between the samples for some of the factors associated with discontinuation which suggest these weaker factors may be less generalizable; however, the relative consistency of the rates of discontinuation and the associations with dose and prior use common in both samples are more likely to be representative of long term opioid use in the U.S. We used stepwise procedures to identify the significant factors in our Cox models; this can lead to model mis-specification errors which may exclude relevant variables and include spurious factors; however, model mis-specification errors are less likely for those factors identified in both samples. When inspecting the Kaplan Meier curves (Figs. 2 and 3), the key variables appear to meet the proportional hazards assumption; however, interactions between time and key variables were significant in models checking the proportional hazards assumption, which suggests that the hazard ratios we report represent the average effect and this may not be strictly proportional throughout the follow-up period. Lastly, because we did not have links between diagnoses and prescriptions nor have patient reported data, it was not possible to identify the specific reason for COT or the pain severity level; this makes it difficult to interpret some of our associations, particularly for high daily opioid doses and lower discontinuation rates.

CONCLUSIONS

Over half of persons prescribed 90 days of opioid therapy over a six-month period remained on opioids years later and these rates of extended use should be considered and discussed with patients prior to initiating a course of COT. The factors most strongly associated with opioid continuation were prior opioid exposure, daily opioid doses of 120 mg MED per day, and possible misuse; however the data from which these associations were observed did not have clinical measures such as pain or disease severity. Additional caution and monitoring is advised for those who receive more than 90 days of continuous opioid therapy, particularly those who are on high doses or exhibit patterns of potential misuse.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse DA022560 to Dr. Mark D. Sullivan. Dr. Jennifer Brennan Braden was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NRSA) Institutional Research Training Grant [T32 MH20021 (Katon)]. Gary Moore provided invaluable programming support in preparing the analytic files from AR Medicaid. The Arkansas Department of Human Services, Division of Medical Services provided no-cost access to the AR Medicaid claims files. Dr. Andrea DeVries is an employee of HealthCore. Dr. Ming-Yu Fan is currently an employee of eBay. Dr. Bradley C. Martin is a consultant to Daiichi Sankyo for work unrelated to the current study. Dr. Mark D. Sullivan had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data andthe accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Noble M, Tregear SJ, Treadwell JR, Schoelles K. Long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and safety. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(2):214–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trescot AM, Boswell MV, Atluri SL, et al. Opioid guidelines in the management of chronic non-cancer pain. Pain Physician. 2006;9(1):1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandner-Kiesling A, Leyendecker P, Hopp M, Tarau L, Lejcko J, Meissner W, Sevcik P, Hakl M, Hrib R, Uhl R, Dürr H, Reimer K. Long-term efficacy and safety of combined prolonged-release oxycodone and naloxone in the management of non-cancer chronic pain. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(6):763–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02360.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papaleontiou M, Henderson CR, Jr, Turner BJ, Moore AA, Olkhovskaya Y, Amanfo L, Reid MC. Outcomes associated with opioid use in the treatment of chronic noncancer pain in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(7):1353–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02920.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. American Pain Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines Panel. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10(2):113–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caudill-Slosberg MA, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Office visits and analgesic prescriptions for musculoskeletal pain in US: 1980 vs. 2000. Pain. 2004;109(3):514–519. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilson AM, Ryan KM, Joranson DE, Dahl JL. A reassessment of trends in the medical use and abuse of opioid analgesics and implications for diversion control: 1997–2002. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28(2):176–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Fan MY, DeVries A, Braden JB, Martin BC. Trends in use of opioids for non-cancer pain conditions 2000–2005 in Commercial and Medicaid insurance plans: the TROUP study. Pain. 2008;138:440–449. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Compton WM, Volkow ND. Major increases in opioid analgesic abuse in the United States: concerns and strategies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81(2):103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paulozzi LJ, Ryan GW. Opioid analgesics and rates of fatal drug poisoning in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(6):506–511. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):85–92. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saunders KW, Dunn KM, Merrill JO, et al. Relationship of opioid use and dosage levels to fractures in older chronic pain patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(4):310–5. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1218-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Fan MY, DeVries A, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Risks for opioid abuse and dependence among recipients of chronic opioid therapy: Results from the TROUP Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112(1–2):90–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clinical Classification Software (CCS) for ICD-9 CM [computer program]. Version. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- 16.Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Fan MY, Devries A, Brennan Braden J, Martin BC. Risks for possible and probable opioid misuse among recipients of chronic opioid therapy in commercial and Medicaid insurance plans: The TROUP Study. Pain. 2010;150(2):332–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.SAS [computer program]. Version 9.1. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc.

- 18.Franklin GM, Rahman EA, Turner JA, Daniell WE, Fulton-Kehoe D. Opioid use for chronic low back pain: A prospective, population-based study among injured workers in Washington state, 2002–2005. Clin J Pain. 2009;25(9):743–751. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181b01710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballantyne JC, Shin NS. Efficacy of opioids for chronic pain: a review of the evidence. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(6):469–78. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31816b2f26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Dhalla IA, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. Opioid dose and drug-related mortality in patients with nonmalignant pain. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(7):686–91. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White AG, Birnbaum HG, Shiller M, Tang J, Katz NP. Analytic models to identify patients at risk for prescription opioid abuse. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(12):897–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reid MC, Engles-Horton LL, Weber MB, Kerns RD, Rogers EL, O'Connor PG. Use of opioid medications for chronic noncancer pain syndromes in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(3):173–179. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becker WC, Sullivan LE, Tetrault JM, Desai RA, Fiellin DA. Non-medical use, abuse and dependence on prescription opioids among U.S. adults: psychiatric, medical and substance use correlates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94(1–3):38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breckenridge J, Clark JD. Patient characteristics associated with opioid versus nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug management of chronic low back pain. J Pain. 2003;4(6):344–350. doi: 10.1016/S1526-5900(03)00638-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Devries A, Fan MY, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Trends in use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain among individuals with mental health and substance use disorders: the TROUP study. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181b99f35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Zhang L, Unutzer J, Wells KB. Association between mental health disorders, problem drug use, and regular prescription opioid use. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(19):2087–2093. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.19.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolf BC, Lavezzi WA, Sullivan LM, Flannagan LM. One hundred seventy two deaths involving the use of oxycodone in Palm Beach County. J Forensic Sci. 2005;50(1):192–5. doi: 10.1520/JFS2004194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.PRESCRIPTION DRUG ABUSE CRISIS. http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/publications/pdf/rx_abuse_plan.pdf (last accessed April 27, 2011).