Abstract

Background

Medications are a cornerstone of the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease. Long-term medication adherence has been the subject of increasing attention in the developed world but has received little attention in resource-limited settings, where the burden of disease is particularly high and growing rapidly. To evaluate prevalence and predictors of non-adherence to cardiovascular medications in this context, we systematically reviewed the peer-reviewed literature.

Methods

We performed an electronic search of Ovid Medline, Embase and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts from 1966 to August 2010 for studies that measured adherence to cardiovascular medications in the developing world. A DerSimonian-Laird random effects method was used to pool the adherence estimates across studies. Between-study heterogeneity was estimated with an I2 statistic and studies were stratified by disease group and the method by which adherence was assessed. Predictors of non-adherence were also examined.

Findings

Our search identified 2,353 abstracts, of which 76 studies met our inclusion criteria. Overall adherence was 57.5% (95% confidence interval [CI] 52.3% to 62.7%; I2 0.98) and was consistent across study subgroups. Studies that assessed adherence with pill counts reported higher levels of adherence (62.1%, 95% CI 49.7% to 73.8%; I2 0.83) than those using self-report (54.6%, 95% CI 47.7% to 61.5%; I2 0.93). Adherence did not vary by geographic region, urban vs. rural settings, or the complexity of a patient’s medication regimen. The most common predictors of poor adherence included poor knowledge, negative perceptions about medication, side effects and high medication costs.

Interpretation

Our study indicates that adherence to cardiovascular medication in resource-limited countries is sub-optimal and appears very similar to that observed in resource-rich countries. Efforts to improve adherence in resource-limited settings should be a priority given the burden of heart disease in this context, the central role of medications in their management, and the clinical and economic consequences of non-adherence.

KEY WORDS: cardiovascular medications, cardiovascular disease, compliance, cardiovascular risk reduction

Non-infectious chronic diseases have long been thought to primarily affect affluent populations. However, these conditions are responsible for more deaths, both in absolute numbers and relative proportions, in resource limited settings.1 Cardiovascular disease imposes a particular burden and is the leading cause of death in all age groups in virtually all low and middle income nations. Its prevalence in these regions is increasing at more than twice the rate observed in resource-rich countries.1 Thus, the prevention and management of cardiovascular illness has become a major focus of healthcare providers worldwide.1

Medications are a cornerstone of cardiovascular risk reduction.2 In resource-rich settings, substantial effort has been devoted to improving appropriate prescribing.2 However, longer-term adherence to evidence-based medications remains suboptimal.2 For example, only half of patients who experience an acute coronary event are adherent to their prescribed statin two years after starting therapy.3,4

Despite its disproportionate share of disease burden, much less is known about medication adherence in resource-limited regions. Access to healthcare, cultural beliefs, education about chronic disease and the role of medication, the nature of patient-physician interactions and social supports, among many other factors, are very different in resource-limited countries and may profoundly affect rates of adherence.5,6 A greater understanding of these factors will help in the development of quality improvement activities in this context. Accordingly, we systematically reviewed the published literature in order to evaluate prevalence and predictors of non-adherence to cardiovascular medications in resource-limited settings.

METHODS

We performed an electronic search of Ovid Medline, Embase and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts from January 1, 1966 to August 19, 2010 for studies that reported adherence to cardiovascular medications in resource-limited regions of the world.

Search Strategy

Our electronic search strategy included medical subject headings (MESH) and keywords related to medication adherence (e.g. “adherence”, “compliance”, “non-adherence”, “non-compliance”, “treatment refusal”), cardiovascular disease (e.g. “hypertension”, “hyperlipidemia”, “anti-diabetic”, “anti-atherosclerosis”), adherence measures (e.g. “medication monitoring”, “pill count”), cardiovascular medication classes (e.g. “ACE inhibitor”, “metformin”, “HMG CoA reductase inhibitors”, and “statins”), and resource-limited countries. Our list of resource-limited countries was based upon the International Monetary Fund list of “emerging and developing economies”, which include 153 countries in Africa, Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe, the Former Soviet states, Central and South America.7

Study Selection

Using pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, two investigators (ADKB, JLL) independently reviewed the electronic search results to identify potentially relevant articles. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. We retrieved the published version of candidate articles and reviewed their reference lists to identify other studies that our search strategy may have missed.

We included studies that evaluated adherence to one or more cardiovascular medications. We excluded studies that: (1) did not present original data, (2) did not evaluate medications for the treatment of prevention of cardiovascular disease, (3) did not present quantitative adherence measures or (4) were not conducted in a resource-limited region. Included studies were not restricted to the English language and were translated accordingly.

Data Extraction

Data on patient and study characteristics, outcomes and study quality were independently extracted from each article by two investigators (ADKB, JLL) using a standardized protocol and reporting form. Specific information collected included study design (i.e. cohort, cross-sectional, randomized control trial), setting (i.e. country and rural or urban environment), patient demographics (including age and gender), the disease and drug evaluated and the method by which adherence was measured. Study quality was assessed with the Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale8 for observational studies, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)9 tool for rating cross-sectional studies and Jadad10 assessment for randomized control trials. A study quality score from each scale was calculated as a proportion of total points that each paper received. We also recorded information on predictors of adherence if any were reported.

Studies were categorized into four mutually exclusive categories based on the disease being treated: (1) diabetes, (2) hypertension, (3) congestive heart failure or (4) coronary artery disease. Studies that evaluated more than one disease (e.g. diabetes and hypertension) and presented these results separately were included in their appropriate category. Studies that did not report results disaggregated by disease sub-type or that did not specify the type of heart disease that patients had were included in the coronary artery disease category.

We also classified studies based on the method by which adherence was assessed: (1) pill counts, (2) self-report or (3) other. The latter category included studies that used electronic pill-bottles (e.g. medication event monitoring system [MEMS]), assessments by healthcare professional, reviews of health records and biochemical assays. In post-hoc analyses, we also evaluated subgroups based upon the complexity of medication regimens, the care setting, the use of drugs for primary as compared with secondary prevention, whether or not medications were provided to patients for free, age, gender and study quality.

Data Analysis

The main outcome measure of our study was a summary estimate of medication adherence. In order to pool studies, the variances of the raw proportions from individual studies (variance[r]) were stabilized using a Freeman–Tukey-type arcsine square root transformation: y = arcsine [√(r/n + 1] + arcsine[√(r + 1)/(n + 1)] with a variance of 1/(n + 1), where n represents the sample size of the study.11,12 A DerSimonian-Laird random effects method was then used to pool the transformed proportions.3,13,14 Our results are reported as summary estimates with 95% confidence intervals. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS v9.2 (Cary, NC).

Between-study heterogeneity was explored in several ways. First, we visually inspected the plot of overall adherence proportions to look for outliers. Second, the proportion of the overall variation in adherence that was attributable to between-study heterogeneity was estimated with an I2 statistic.15 Third, heterogeneity was re-evaluated after influential studies were excluded. Finally, pooled adherence was calculated for each of our pre-specified study sub-categories. Pooling was only performed in subgroups with three or more studies.

Predictors of medication adherence were evaluated from those studies that reported empirical results about factors affecting adherence. Included studies either presented adherence rates stratified by a given predictor (e.g. men vs. women) or regression parameters (or correlation coefficients) for the association between adherence and a potential predictor. To maintain consistency across studies, predictors were reoriented, if necessary, to evaluate their association with rates of non-adherence rather than adherence. For example, if a study reported that lower medication costs were associated with higher rates of adherence, we report this as demonstrating a relationship between higher drug costs and higher rates of non-adherence. Because not all studies tested the statistical significance of the given predictor, we conservatively assumed that the associations of these predictors with adherence were not statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Characteristics

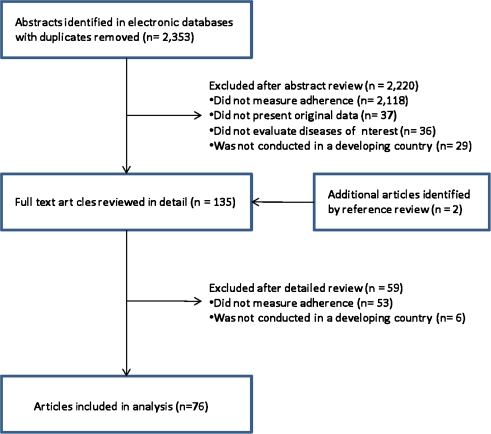

Our search identified 2,353 abstracts, of which 76 studies met our inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). These studies included a total of 124,733 subjects (sample size range 17 to 100,691, median 157 subjects). Forty-nine studies evaluated adherence to antihypertensive medications16–64 and an additional 17,23,55,65–79 380–82 and 983–91 studies assessed medications for diabetes, congestive heart failure and coronary artery disease, respectively. The studies were predominantly performed in urban settings and were mostly based in Africa (40%), Asia (34%) or Central and South America (14%). All studies were either cross-sectional or cohort studies, with the exception of 5 randomized control trials. The majority assessed adherence using pill counts (n = 16) or self-report (n = 49). Further details of the study designs and patient demographics are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Source | Patient Population | Sample Size | Country | Rural/ Urban | Design | Adherence Measure | Definition of Adherence | Adherence Rate (%) | Quality Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | |||||||||

| Venter, 199165 | Randomly selected diabetes clinic patients | 68 | South Africa | Urban | Cross sectional | Urine test | Drug detected in urine | 35 | 50 |

| Garay-Sevilla, 199571 | Sample of diabetic patients not previously on treatment at “diabetes clubs” | 200 | Mexico | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 92 | 88 |

| Kaur, 199874 | Diabetic patients in resettlement colony | 35 | India | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 63 | 13 |

| Khattab, 199975 | All registered diabetic patients at a health center | 142 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | Cohort | Pill Count | Regular medication use | 98 | 11 |

| El-Shazly, 200070 | Random selection of diabetic patients with complete health service insurance records | 1000 | Egypt | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | … | 89 | 100 |

| Duran, 200169 | Adults with type 2 diabetes not taking insulin | 150 | Mexico | Urban | Cross sectional | Pill Count | ≥80% pills taken | 54 | 38 |

| Yousuf, 200178 | All eligible hospital patients with diabetes | 163 | Pakistan | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 41 | 38 |

| Srinivas, 200277 | Population-based sample of registered diabetics on medication for >1 year | 111 | India | Rural | Cross sectional | Self report | No interruption of more than 1 month within the last year | 43 | 50 |

| Hernandez 200373 | Consecutive clinic patients with type 2 diabetes | 58 | Mexico | Urban | Cross sectional | Pill Count | … | 59 | 50 |

| Cui, 200567 | Hospital inpatients with diabetes | 144 | China | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | … | 74 | 50 |

| Zhang, 200579 | Hospital inpatients with diabetes | 176 | China | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 53 | 50 |

| Babwah, 200666 | Consecutive patients at medical and diabetes clinics | 360 | Trinidad | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 71 | 75 |

| Duff, 200668 | Randomly selected clinic patients with diabetes | 86 | Jamaica | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 45 | 75 |

| Hanko, 200772 | Patients with diabetes from randomly selected pharmacies | 211 | Hungary | Mix | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 53 | 75 |

| Roaeid, 200776 | Diabetes clinic patients with diabetes for >1 year | 805 | Libya | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 73 | 50 |

| Coronary artery disease | |||||||||

| Olubodun, 199089 | Hypertensive patients referred to hospital cardiac unit | 37 | Nigeria | Urban | Cohort | Self report | Regular medication use | 0 | 63 |

| Wiseman, 199191 | Sample of patients attending cardiac clinic outpatients | 137 | South Africa | Urban | Cross sectional | Serum drug titers | Serum concentration differs from measured by < 50% | 60 | 38 |

| Chizzola, 199685 | Sample from outpatient cardiology referral center | 185 | Brazil | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 41 | 75 |

| Dantas, 200286 | Hospital inpatients who had undergone CABG surgery in the prior 5 months | 17 | Brazil | Urban | Cohort | Self report | Regular medication use | 65 | 22 |

| Rotchford, 200290 | Patients with diabetes presenting for clinic follow up | 253 | South Africa | Rural | Cross sectional | Self report | Taking medication in previous 24 hours | 94 | 50 |

| El-Gatit, 200387 | Clinic patients post aortic valve replacement surgery | 62 | Libya | Urban | Cohort | MEMS | Regular medication use | 93 | 11 |

| Asefzadeh, 200584 | Randomly selected clinic patients with cardiovascular disease | 56 | Iraq | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 59 | 50 |

| Kocer, 200688 | Clinic patients at risk for stroke | 612 | Turkey | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 56 | 50 |

| Moodley, 200683 | Medical scheme beneficiaries on lipid reducing medications | 100,691 | South Africa | … | Prospective cohort | Pharmacy claims | … | 87 | 63 |

| Heart failure | |||||||||

| Joshi, 199981 | Consecutive inpatients with congestive heart failure | 125 | India | Urban | Cross sectional | Pill Count | ≥80% pills taken | 55 | 50 |

| Bhagat, 200180 | Patients with clinically stable heart failure from 4 general practice clinics | 22 | Zimbabwe | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use and knowledge | 73 | 38 |

| Sadik, 200582 | Hospital in- and outpatients with heart failure | 208 | UAE | Urban | Randomized controlled trial | Self report | Regular medication use | 33 | 60 |

| Hypertension | |||||||||

| Buchanan, 197923 | Sample of black diabetic and hypertensive clinic patients | 100 | South Africa | Urban | Cohort | Home visits | ≥85% pills taken | 38 | 75 |

| Unterhalter197955 | Sample of black diabetic clinic patients | 50 | South Africa | Urban | Cross sectional | Pill Count | ≥85% pills taken | 38 | 50 |

| Supramaniam, 198254 | Random sample of armed force personnel with hypertension | 102 | Malaysia | Rural | Cross sectional | Self report, visit records | … | 41 | 25 |

| Marshall, 198843 | Random sample of women not previously receiving treatment | 88 | South Africa | Rural | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 73 | 0 |

| Roy, 199048 | Hospital inpatients with hypertension who had a prior stroke | 66 | Bangladesh | Urban | Cohort | Self report | Regular medication use | 12 | 22 |

| Stein, 199053 | Sample of hypertension clinic patients | 18 | Zimbabwe | Urban | Open cross-over | Pill Count | Correct number of pills returned | 97 | 75 |

| Saunders, 199151 | Consecutive clinic patients with hypertension | 20 | South Africa | Urban | Randomized controlled trial | Pill count | ≥80% pills taken | 15 | 20 |

| Lim, 199239 | Consecutive hospital outpatients with hypertension | 168 | Malaysia | Urban | Cohort | Pill count, self report | ≥80% pills taken | 74 | 63 |

| Hungerbuhler, 199534 | Consecutive clinic patients with uncontrolled hypertension | 187 | Seychelles | … | Cohort | Urine test | Pills taken “concordant” with pills prescribed | 56 | 50 |

| Joshi, 199635 | Consecutive new clinic patients with hypertension | 139 | India | Urban | Cohort | Pill Count | ≥80% pills taken | 66 | 63 |

| Khalil, 199762 | Random sample of health centers patients with hypertension | 347 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | Cohort | Pill Count | ≥80% pills taken | 47 | 63 |

| Maro, 199742 | Cardiac clinic patients starting antihypertensive treatment | 146 | Tanzania | Urban | Cohort | Self report or pill count | ≥75% pills taken | 90 | 44 |

| Lunt, 199841 | Community health center patients with hypertension | 889 | South Africa | Urban | Cohort | Drug pick up | Collected drugs on ≥ 75% of visits | 77 | 33 |

| Salome Kruger, 199850 | Outpatients attending clinic for at least 1 year | 132 | South Africa | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 38 | 50 |

| Zdrojewski, 199960 | Elderly patients with hypertension | 198 | Poland | … | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 71 | 50 |

| Elzubier, 200029 | Consecutive clinic patients with hypertension | 198 | Sudan | Urban | Cross sectional | Pill Count | ≥80% pills taken | 60 | 75 |

| Bovet, 200221 | Random sample of patients with sustained hypertension | 50 | Seychelles | Rural | Cohort | MEMS | ≥86% pills taken | 46 | 44 |

| Jiang, 200261 | Clinic patients with hypertension from general hospitals in 8 cities | 4510 | China | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | … | 44 | 38 |

| Youssef, 200257 | Random selection of hypertensive patients at health insurance clinics | 316 | Egypt | Urban | Cross sectional | Records, self report | ≥90% pills taken | 74 | 50 |

| Bharucha, 200320 | Random population sample of patients with hypertension | 453 | India | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | … | 64 | 38 |

| Li, 200338 | Clinic patients with hypertension from 8 cities | 3112 | China | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 44 | 75 |

| Salako, 200349 | Consecutive clinic patients with hypertension | 422 | Nigeria | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | … | 80 | 25 |

| Buabeng, 200422 | All new clinic patients with hypertension | 128 | Ghana | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | ≥80% pills taken | 7 | 38 |

| Chen, 200425 | Sample of patients with hypertension on medication | 312 | China | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 43 | 50 |

| Hadi, 200432 | All eligible patients with hypertension who attended clinic consultation | 250 | Iran | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | ≥90% pills taken | 40 | 100 |

| Lu, 200440 | Sample of patients with hypertension | 1831 | China | Urban | Cross sectional | … | … | 74 | 63 |

| Naddaf, 200444 | Randomly selected clinic patients with hypertension | 100 | Jordan | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | No missed doses in prior 30 days | 58 | 38 |

| Peltzer, 200446 | Consecutive clinic patients with hypertension for >1 year | 100 | South Africa | Mix | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 65 | 75 |

| Sookaneknun, 200452 | Pharmacy and primary care patients with hypertension | 217 | Thailand | Mix | Randomized controlled trial | Pill Count | ≥80% pills taken | 61 | 49 |

| Akpa, 200516 | Consecutive cardiology clinic patients with hypertension | 100 | Nigeria | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | ≥75% pills taken | 60 | 25 |

| Coelho, 200526 | Randomly selected clinic patients with hypertension | 245 | Brazil | Urban | Cohort | Self report | … | 87 | 22 |

| Feng, 200530 | Hospital inpatients with essential hypertension | 164 | China | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 65 | 75 |

| Fodor, 200531 | All hypertensive employees at workplace | 359 | Austria, Hungary, Slovakia | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 54 | 75 |

| Xiao, 200556 | Hospital inpatients with hypertension | 119 | China | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | … | 41 | 50 |

| Yusuff, 200559 | Clinic outpatients presenting with hypertension | 200 | Nigeria | … | Cohort | Record | Regular medication use | 83 | 44 |

| Almas, 200617 | Outpatients with hypertension | 200 | Pakistan | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Did not miss dose for 6 months | 57 | 63 |

| Ben Abdelaziz, 200619 | Representative sample of hypertensive patients in regional health care facilities | 292 | Tunisia | Urban | Cross sectional | Healthcare assessment | Pharmacy contacts | 59 | 38 |

| Hassan, 200633 | Clinic patients with hypertension on medications for at least 3 months | 242 | Malaysia | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | ≥80% pills taken | 44 | 100 |

| Lambert, 200637 | Convenience sample of hypertension clinic patients | 98 | South Africa | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 24 | 63 |

| Amira, 200718 | Consecutive clinic patients with hypertension | 225 | Nigeria | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 65 | 75 |

| Castro, 200724 | Consecutive patients with hypertension from a family health program | 66 | Brazil | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | Regular medication use | 67 | 63 |

| de Souza, 200727 | Consecutive patients at a cardiovascular pharmacology clinic | 48 | Brazil | Urban | Cohort | Pill count | ≥80% pills taken | 64 | 44 |

| Dennison, 200728 | Black patients with hypertension at local primary care clinics | 403 | South Africa | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | … | 48 | 88 |

| Konin, 200736 | Consecutive clinic patients who were hypertensive | 200 | Ivory Coast | Urban | Cross sectional | Self report | … | 13 | 50 |

| Prado, 200764 | Random sample of health center patients with mild to moderate hypertension | 120 | Brazil | Urban | Cross sectional | Pill count | ≥80% pills taken | 38 | 75 |

| Qureshi, 200747 | Patients in the control arm of a hypertension health education trial | 100 | Pakistan | Urban | Randomized controlled trial | MEMS | Regular medication use | 48 | 60 |

| Yusuff, 200758 | Random sample of hypertension clinic patients | 400 | Nigeria | Urban | Cross sectional | Healthcare assessment | … | 49 | 63 |

| Nugmanova, 200845 | Sample of patients with hypertension | 227 | Kazakhstan | Urban | Randomized controlled trial | Self report | Medication taken on the morning of interview | 38 | 40 |

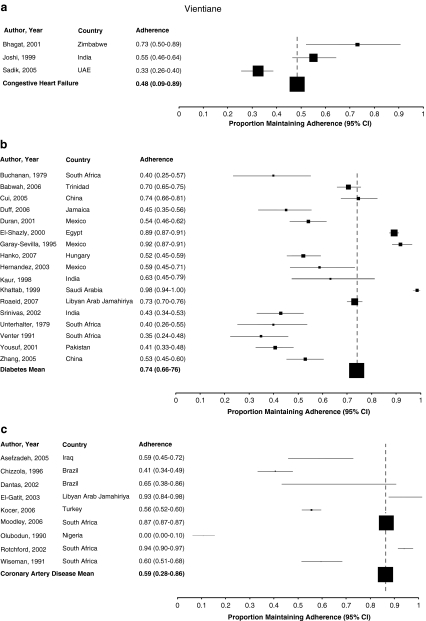

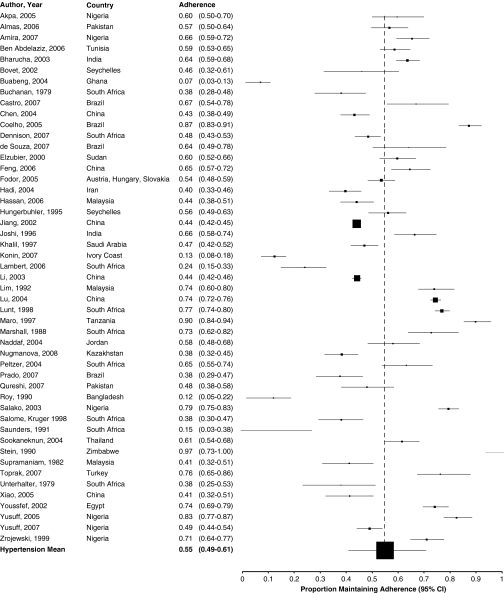

Reported Adherence

The included studies reported adherence ranging from 0 to 98% (Fig. 2a-d). Only eighteen (23%) studies reported that, on average, patients were fully adherent to their prescribed therapy. Pooled across studies, overall adherence to cardiovascular drugs was 57.5% (95% confidence interval [CI] 52.3% to 62.7%; I2 0.98).

Figure 2.

a Adherence to medications for congestive heart failure. b Adherence to medications for diabetes. c Adherence to medications for coronary artery disease. d Adherence to medications for hypertension.

Subgroups

Reported adherence was relatively consistent across study subgroups (Table 2), although adherence to medications for congestive heart failure was lower (48.4%, 95% CI 9.0% to 89.2%; I2 0.68) than that for other disease categories. Studies using pill counts reported higher levels of adherence (62.1%, 95% CI 49.7% to 73.8%; I2 0.83) than those using self-report (54.6%, 95% CI 47.7% to 61.5%; I2 0.93) or other methods (63%, 95% CI 51% to 74.3%, I2 0.96) to estimate adherence. Adherence did not vary by geographic region or urban vs. rural settings, but when assessed in the context of randomized controlled trials, adherence was lower (42.6%, 95% CI 25.3% to 60.9%; I2 0.67) than in observational studies (59.0%, 95% CI 52.6% to 64.1%; I2 0.98). Similarly, adherence did not significantly change according to gender, age, the complexity of medication regimens, by clinical setting or the integrity of the studies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Reported Adherence by Subgroup

| Characteristic | Subgroup | N | Summary estimate (95%CI) | I2 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | Diabetes | 17 | 0.74 (0.66 to 0.76) | 0.94 (0.86 to 0.93) |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 9 | 0.59 (0.28 to 0.86) | 0.96 (0.94 to 0.97) | |

| CHF | 3 | 0.48 (0.09 to 0.89) | 0.68 (0.11 to 0.91) | |

| Hypertension | 49 | 0.55 (0.49 to 0.61) | 0.91 (0.89 to 0.93) | |

| Adherence Measure | Count | 16 | 0.62 (0.5 to 0.74) | 0.83 (0.73 to 0.89) |

| Self report | 48 | 0.55 (0.48 to 0.62) | 0.93 (0.92 to 0.94) | |

| Other | 14 | 0.63 (0.51 to 0.74) | 0.96 (0.94 to 0.97) | |

| Geographic Region | Africa | 34 | 0.58 (0.48 to 0.68) | 0.96 (0.95 to 0.97) |

| Asia | 26 | 0.54 (0.46 to 0.61) | 0.91 (0.88 to 0.93) | |

| Central & South America | 11 | 0.61 (0.36 to 0.83) | 0.87 (0.73 to 0.93) | |

| Eastern Europe, Soviet Union | 7 | 0.57 (0.46 to 0.67) | 0.63 (0.15 to 0.84) | |

| Study Design | Observational | 73 | 0.59 (0.53 to 0.64) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.98) |

| Randomized controlled trial | 5 | 0.43 (0.25 to 0.61) | 0.67 (0.15 to 0.88) | |

| Proportion of male patients | > median | 34 | 0.64 (0.64 to 0.64) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.98) |

| < median | 34 | 0.63 (0.64 to 0.64) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.98) | |

| Age | > median | 29 | 0.61 (0.53 to 0.69) | 0.9 (0.87 to 0.92) |

| < median | 27 | 0.58 (0.48 to 0.69) | 0.92 (0.89 to 0.94) | |

| Journal Impact Factor | > median | 28 | 0.53 (0.43 to 0.62) | 0.9 (0.87 to 0.93) |

| < median | 13 | 0.54 (0.37 to 0.7) | 0.96 (0.94 to 0.97) | |

| Unknown | 37 | 0.62 (0.56 to 0.69) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.98) | |

| Proportion of patients receiving study medication for free | 1-49% | 4 | 0.31 (0.02 to 0.74) | 0.81 (0.49 to 0.93) |

| 50-99% | 3 | 0.52 (0.26 to 0.78) | 0.51 (0.69 to 0.86) | |

| Unknown | 54 | 0.59 (0.53 to 0.65) | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.94) | |

| Proportion of patients taking medications more than twice daily | <50% | 4 | 0.56 (0.32 to 0.78) | 0.84 (0.59 to 0.94) |

| >50% | 4 | 0.71 (0.38 to 0.95) | 0.85 (0.62 to 0.94) | |

| Unknown | 70 | 0.57 (0.51 to 0.62) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.98) | |

| Proportion of patients taking 2 or more medications | <50% | 14 | 0.66 (0.57 to 0.76) | 0.96 (0.94 to 0.97) |

| >50% | 13 | 0.54 (0.43 to 0.65) | 0.75 (0.56 to 0.85) | |

| Unknown | 51 | 0.55 (0.48 to 0.62) | 0.94 (0.92 to 0.95) | |

| Clinical setting | Primary care | 14 | 0.52 (0.38 to 0.66) | 0.9 (0.85 to 0.93) |

| Secondary or tertiary care | 43 | 0.59 (0.51 to 0.67) | 0.93 (0.92 to 0.94) | |

| Primary, secondary or tertiary care | 2 | 0.59 (0 to 1) | 0.8 (0.12 to 0.95) | |

| Unknown | 18 | 0.58 (0.49 to 0.67) | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.97) | |

| Patients taking medications for the first time (i.e. new users) | Yes | 11 | 0.47 (0.28 to 0.67) | 0.78 (0.62 to 0.88) |

| No | 19 | 0.59 (0.47 to 0.7) | 0.9 (0.86 to 0.93) | |

| Unknown | 48 | 0.59 (0.55 to 0.65) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.98) | |

| Drugs being used for primary prevention | Yes | 29 | 0.53 (0.44 to 0.62) | 0.89 (0.85 to 0.91) |

| No | 4 | 0.58 (0.05 to 1) | 0.9 (0.76 to 0.95) | |

| Unknown | 45 | 0.6 (0.54 to 0.67) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.98) | |

| Length of study follow-up | >6 months | 26 | 0.54 (0.45 to 0.63) | 0.89 (0.85 to 0.92) |

| < 6 months | 30 | 0.61 (0.51 to 0.71) | 0.95 (0.93 to 0.96) | |

| Unknown | 21 | 0.57 (0.48 to 0.66) | 0.96 (0.95 to 0.97) | |

| Overall | 76 | 0.58 (0.52 to 0.63) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.98) |

Predictors of Adherence

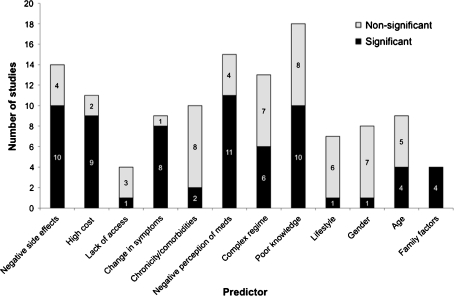

Of the 76 papers included in our study, 29 reported factors associated with adherence. The most commonly and consistently reported predictors of non-adherence were poor knowledge (10 of 18 studies evaluating this factor reported a statistically significant association), negative perceptions about medications (11 of 15 studies evaluating this factor reported a statistically significant association), the occurrence of side effects (10 of 14 studies evaluating this factor reported a statistically significant association) and high medication costs (9 of 11 studies evaluating this factor reported a statistically significant association) (Fig. 3). All studies (n = 4) reporting social factors (e.g. lack of family support) as a predictor of non-adherence reported a significant association, as did the majority of studies (79%) evaluating a change (improvement or worsening) of symptoms. Patient factors such as age, gender, lifestyle factors, complex treatment regimens, and lack of access to health care services were not consistently associated with non-adherence. Restricting our analysis to studies that used significance testing to compare risk factors between adherent and non-adherent patients did not change our findings.

Figure 3.

Factors predicting non-adherence to cardiovascular medication.

DISCUSSION

The role of medications in the management of cardiovascular disease is well recognized. While these conditions impose a greater burden in resource-limited than resource-rich countries, medication adherence in this context has received very little attention. Even the World Health Organization report1 which highlights the global problem of non-adherence relies almost exclusively on studies data from the developed world. To fill this void, we systematically reviewed studies in the peer-reviewed published literature that evaluated adherence to cardiovascular medications in the developing world. We found that although there was substantial heterogeneity across studies, overall adherence was 58%. This rate is remarkably similar to that observed in resource-rich regions.4,92,93 As such, our results highlight the quality improvement opportunity that exists worldwide from improving adherence to essential medications.

Given the scarcity of health resources available in resource-scarce countries, only quality improvement interventions that are cost-efficient are likely to be feasible.94 As a whole, increasing adherence to evidence-based medications is likely to be a more efficient strategy for improving cardiovascular outcomes than increasing treatment initiation rates or developing and evaluating new cardiovascular medications.95 Further, improved adherence has been shown to improve the effectiveness of interventions which target lifestyle modifications96 and may represent an opportunity to not only improve health quality but also reduce health care spending.1,2,4 This may be particularly true in resource-limited settings where the majority of cardiovascular medications are available as low-cost generic products.97

Unfortunately, the literature contains virtually no published reports of successfully implemented and rigorously evaluated cardiovascular medication adherence improvement strategies in resource-limited countries. Numerous strategies to improve adherence have been studied in the developed world. These include approaches that are “informational” (e.g. telephonic coaching, group classes, or the mailing of instructional materials), “behavioral” (e.g. pillboxes, mailed reminders, simplifying treatment regimens, or audit and feedback), “family and social focused” (e.g. support groups and family counseling), or some combination thereof.6

The studies we reviewed included a broad range of factors affecting adherence, with poor knowledge, negative perceptions about medications, the occurrence of side effects and high medication costs being evaluated most often and being most consistently associated with non-adherence. The literature evaluating reasons for non-adherence in resource-poor settings is extremely limited, and the most robust data comes from studies evaluating therapies for HIV. Mills et al. have found cost, complexity and perception of medications to be consistent reasons for non-adherence to medications in this context.6,98 These factors have also been observed in resource-rich settings as well.4,99 Thus, general approaches to non-adherence used in resource-rich settings may hold promise once translated into the developing world context.

We found adherence to be consistently poor across all of the disease subgroups we evaluated. The slightly worse adherence rates in studies of congestive heart failure medications may have been the result of the nature of the patient population or the severity of their disease, although these factors were not explored in any of the studies we evaluated. Interestingly, when assessed by pill count, adherence rates were better than when evaluated by self-report. This is somewhat different than studies in resource-limited settings where subjective measures tend to provide higher estimates of adherence than those provided by objective measures.92 While the reason for our apparently contrary findings are unclear, it may be that patients’ perceptions of medications and the social stigma associated with chronic disease may actually lead patients to under-report their true levels of adherence. Nevertheless, future adherence improvement in these resource-limited areas should pay particular attention to study design and the use of rigorous assessment methods.

Our study has several limitations. Although we have evaluated studies that have studied adherence rates in resource-rich countries, we did not directly compare adherence rates between the resource-rich and resource-limited countries, as no such studies exist. Although our search strategy included a wide range of electronic sources and our literature search sample was quite large, we may have missed some studies, especially if research conducted in resource-limited countries is less likely to be published. Furthermore, we did not include studies presented in abstract form at a scientific meeting but which were not subsequently published in the peer-reviewed literature. Due to the variation in trial size and methodology, there is significant heterogeneity between the studies, despite our having performed numerous subgroup analyses. It is possible that some of the between study differences in adherence we observed were due to differences in adherence patterns associated with different classes of medications to treat a single condition (for example, diuretics as compared to ACE inhibitors for hypertension).100 The included studies do not provide sufficient detail to explore this further. While our study summarizes possible predictors of non-adherence to cardiovascular medications, in some cases, these predictors were only reported by a minority of studies. As such, we are only able to comment on the importance of these factors as a proportion of studies actually report on them.

In conclusion, adherence to cardiovascular medication in resource-limited countries is sub-optimal and appears similar to rates observed in the developed world. Greater attention to long-term adherence in resource-limited countries should be a priority given the burden of heart disease in this context, the central role of medications in their management, and the clinical and economic consequences of non-adherence.

Acknowledgement

This work was not funded by any external sources.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.WHO. Adherence to Long-term Therapies: Evidence for action. World Health Organisation 2003.

- 2.Choudhry NK. Improving the pathway from cardiovascular medication prescribing to longer-term adherence: new results about old issues. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:223–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.957142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choudhry NK, Setoguchi S, Levin R, Winkelmayer WC, Shrank WH. Trends in adherence to secondary prevention medications in elderly post-myocardial infarction patients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17:1189–96. doi: 10.1002/pds.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choudhry NK, Winkelmayer WC. Medication adherence after myocardial infarction: a long way left to go. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:216–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0478-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bangsberg DR, Hecht FM, Charlebois ED, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitors, HIV-1 viral load, and development of drug resistance in an indigent population. AIDS. 2000;14:357–66. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003100-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Buchan I, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa and North America: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;296:679–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.6.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Monetary Fund. World economic and financial surveys: List of emerging and developing economies; 2009.

- 8.Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses.

- 9.West S, King V, Carey ST, et al. Systems to Rate the Strength Of Scientific Evidence: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2002 April 2002.

- 10.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaynes ET. Confidence intervals vs. Bayesian intervals. In: Harper WL, Hooker CA, editors. Foundations of probability theory, statistical inference, and statistical theories of science. Dordrecht: Reidel; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stuart A, Ord JK. Kendall's Advanced Theory of Statistics. 6. London: Arnold Publishers; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fleiss JL. The statistical basis of meta-analysis. Stat Methods Med Res. 1993;2:121–45. doi: 10.1177/096228029300200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akpa MR, Agomuoh DI, Odia OJ. Drug compliance among hypertensive patients in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2005;14:55–7. doi: 10.4314/njm.v14i1.37136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Almas A, Hameed A, Ahmed B, Islam M. Compliance to antihypertensive therapy. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2006;16:23–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amira OC, Okubadejo NU. Frequency of complementary and alternative medicine utilization in hypertensive patients attending an urban tertiary care centre in Nigeria. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7:30. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ben Abdelaziz A, Ben Othman A, Mandhouj O, Gaha R, Bouabid Z, Ghannem H. [Audit of management of arterial hypertension in primary health care in Sousse] Tunis Med. 2006;84:148–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bharucha NE, Kuruvilla T. Hypertension in the Parsi community of Bombay: a study on prevalence, awareness and compliance to treatment. BMC Public Health. 2003;3:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bovet P, Burnier M, Madeleine G, Waeber B, Paccaud F. Monitoring one-year compliance to antihypertension medication in the Seychelles. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:33–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buabeng K. Unaffordable drug prices: the major cause of non-compliance with hypertension medication in Ghana. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2004;7:350–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchanan N, Shuenyane E, Mashigo S, Mtangai P, Unterhalter B. Factors influencing drug compliance in ambulatory Black urban patients. S Afr Med J. 1979;55:368–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castro RA, Moncau JE, Marcopito LF. Hypertension prevalence in the city of Formiga, MG, Brazil. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2007;88:334–9. doi: 10.1590/S0066-782X2007000300013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen W, Huang X, Zheng J, Huang W. Survey on drug compliance of patients with hypertension in residents at Shangmeilin new community in Shenzhen. Chin J Clin Rehabil. 2004;8:5790–1. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coelho EB. Moyses Neto M, Palhares R, Cardoso MC, Geleilete TJ, Nobre F [Relationship between regular attendance to ambulatory appointments and blood pressure control among hypertensive patients] Arq Bras Cardiol. 2005;85:157–61. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2005001600002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Souza WA, Yugar-Toledo JC, Bergsten-Mendes G, Sabha M, Moreno H., Jr Effect of pharmaceutical care on blood pressure control and health-related quality of life in patients with resistant hypertension. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:1955–61. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dennison CR, Peer N, Steyn K, Levitt NS, Hill MN. Determinants of hypertension care and control among peri-urban Black South Africans: the HiHi study. Ethn Dis. 2007;17:484–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elzubier AG, Husain AA, Suleiman IA, Hamid ZA. Drug compliance among hypertensive patients in Kassala, eastern Sudan. East Mediterr Health J. 2000;6:100–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng L, Lui J, Duan Y. Medical order-obeying behavior in 164 patients with essential hypertension. Chin J Clin Rehabil. 2005;9:150–1. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fodor GJ, Kotrec M, Bacskai K, et al. Is interview a reliable method to verify the compliance with antihypertensive therapy? An international central-European study. J Hypertens. 2005;23:1261–6. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000170390.07321.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hadi N, Rostami-Gooran N. Determinant factors of medication compliances in hypertensive patients of Shiraz, Iran. Archives of Iranian Medicine. 2004;7:292–6. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hassan NB, Hasanah CI, Foong K, et al. Identification of psychosocial factors of noncompliance in hypertensive patients. J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20:23–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hungerbuhler P, Bovet P, Shamlaye C, Burnand B, Waeber B. Compliance with medication among outpatients with uncontrolled hypertension in the Seychelles. Bull World Health Organ. 1995;73:437–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joshi PP, Salkar RG, Heller RF. Determinants of poor blood pressure control in urban hypertensives of central India. J Hum Hypertens. 1996;10:299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Konin C, Adoh M, Coulibaly I, et al. Black Africans' compliance to antihypertensive treatment. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2007;100:630–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lambert EV, Steyn K, Stender S, Everage N, Fourie JM, Hill MN. Cross-cultural validation of the hill-bone compliance to high blood pressure therapy scale in a South African, primary healthcare setting. Ethn Dis. 2006;16:286–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li W, Jiang X, Ma H, et al. Awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in patients attending hospital clinics in China. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1191–7. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200306000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lim TO, Ngah BA. The Mentakab Hypertension Study project. Part II–Why do hypertensives drop out of treatment? Singapore Med J. 1991;32:249–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu J, Li LM, Cao WH, Zhan SY, Hu YH. Postmarketing surveillance on Benazepril. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2004;25:412–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lunt DW, Edwards PR, Steyn K, Lombard CJ, Fehrsen GS. Hypertension care at a Cape Town community health centre. S Afr Med J. 1998;88:544–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maro EE, Lwakatare J. Medication compliance among Tanzanian hypertensives. East Afr Med J. 1997;74:539–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marshall RA, Yach D. Management of hypertension in Mamre women. S Afr Med J. 1988;74:346–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Naddaf A. Lifestyle of hypertensive patients and their drug compliance. Bulletin of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2004;27:307–14. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nugmanova A, Pillai G, Nugmanova D, Kuter D. Improving the management of hypertension in Kazakhstan: Implications for improving clinical practice, patient behaviors, and health outcomes. Global Public Health. 2008;3:214–31. doi: 10.1080/17441690701872664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peltzer K. Health beliefs and prescription medication compliance among diagnosed hypertension clinic attenders in a rural South African Hospital. Curationis. 2004;27:15–23. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v27i3.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qureshi NN, Hatcher J, Chaturvedi N, Jafar TH. Effect of general practitioner education on adherence to antihypertensive drugs: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;335:1030. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39360.617986.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roy PK, Arif SM, Alam MR, Khan FD, Ahmad Q, Chowdhury SG. Stroke in patients having inadequate or irregular antihypertensive therapy. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 1990;16:52–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salako BL, Ajose FA, Lawani E. Blood pressure control in a population where antihypertensives are given free. East Afr Med J. 2003;80:529–31. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v80i10.8756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salome Kruger H, Gerber JJ. Health beliefs and compliance of black South African outpaitents with antihypertensive medication. Journal of Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 1998;15:201–9. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saunders LD, Irwig LM, Gear JS, Ramushu DL. A randomized controlled trial of compliance improving strategies in Soweto hypertensives. Med Care. 1991;29:669–78. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199107000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sookaneknun P, Richards RM, Sanguansermsri J, Teerasut C. Pharmacist involvement in primary care improves hypertensive patient clinical outcomes. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:2023–8. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stein CM, Neill P, Mwaluko GM, Kusema T. Combination of a thiazide, a vasodilator and reserpine compared with methyldopa plus hydrochlorothiazide in the treatment of hypertension in Zimbabwe. S Afr Med J. 1990;77:243–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Supramaniam V. Study of Malaysian military hypertensives–therapy compliance. Med J Malaysia. 1982;37:249–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Unterhalter B. Compliance with Western medical treatment in a group of black ambulatory hospital patients. Soc Sci Med [Med Psychol Med Sociol] 1979;13A:621–30. doi: 10.1016/0271-7123(79)90107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xiao H-M, Jiang X-Y. Drug compliance of elderly patients with hypertension. Chin J Clin Rehabil. 2005;9:30–1. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Youssef RM, Moubarak II. Patterns and determinants of treatment compliance among hypertensive patients. East Mediterr Health J. 2002;8:579–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yusuff K, Alabi A. Assessing patient adherence to anti-hypertensive drug therapy: Can a structured pharmacist-conducted interview separated the wheat from the chaff? International Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2007;15:295–300. doi: 10.1211/ijpp.15.4.0007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yusuff KB, Balogun OB. Pattern of drug utilization among hypertensives in a Nigerian teaching hospital. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:69–74. doi: 10.1002/pds.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zdrojewski T, Januszko W, Drygas W, et al. Pharmacotherapy of arterial hypertension and pharmacoeconomic aspects of hypotensive therapy in elderly patients in Poland. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 1999;102:787–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiang X, Li W, Ma L, Kong L, Jin S, Liu L. Knowledge on hypertension and the effect of management on hypertension in patients attending hospital clinics. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2002;23:269–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khalil SA, Elzubier AG. Drug compliance among hypertensive patients in Tabuk, Saudi Arabia. J Hypertens. 1997;15:561–5. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715050-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Toprak D, Demir S. Treatment choices of hypertensive patients in Turkey. Behav Med. 2007;33:5–10. doi: 10.3200/BMED.33.1.5-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Prado JC, Jr, Kupek E, Mion D., Jr Validity of four indirect methods to measure adherence in primary care hypertensives. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21:579–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Venter HL, Joubert PH, Foukaridis GN. Compliance in black patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus receiving oral hypoglycaemic therapy. S Afr Med J. 1991;79:549–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Babwah F, Baksh S, Blake L, et al. The role of gender in compliance and attendance at an outpatient clinic for type 2 diabetes mellitus in Trinidad. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2006;19:79–84. doi: 10.1590/S1020-49892006000200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cui J. Association of educational level and behavior of medical compliance with the level of blood glucose in diabetic patients. Chin J Clin Rehabil. 2005;2005:36. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Duff EM, O'Connor A, McFarlane-Anderson N, Wint YB, Bailey EY, Wright-Pascoe RA. Self-care, compliance and glycaemic control in JAMAican adults with diabetes mellitus. West Indian Med J. 2006;55:232–6. doi: 10.1590/S0043-31442006000400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Duran-Varela BR, Rivera-Chavira B, Franco-Gallegos E. Pharmacological therapy compliance in diabetes. Salud Publica Mex. 2001;43:233–6. doi: 10.1590/S0036-36342001000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.El-Shazly M, Abdel-Fattah M, Zaki A, et al. Health care for diabetic patients in developing countries: a case from Egypt. Public Health. 2000;114:276–81. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3506(00)00345-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Garay-Sevilla ME, Nava LE, Malacara JM, et al. Adherence to treatment and social support in patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 1995;9:81–6. doi: 10.1016/1056-8727(94)00021-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hanko B, Kazmer M, Kumli P, et al. Self-reported medication and lifestyle adherence in Hungarian patients with Type 2 diabetes. Pharm World Sci. 2007;29:58–66. doi: 10.1007/s11096-006-9070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hernandez-Ronquillo L, Tellez-Zenteno JF, Garduno-Espinosa J, Gonzalez-Acevez E. Factors associated with therapy noncompliance in type-2 diabetes patients. Salud Publica Mex. 2003;45:191–7. doi: 10.1590/S0036-36342003000300008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kaur K, Singh MM, Kumar, Walia I. Knowledge and self-care practices of diabetics in a resettlement colony of Chandigarh. Indian J Med Sci. 1998;52:341–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Khattab MS, Aboifotouh MA, Khan MY, Humaidi MA, al-Kaldi YM. Compliance and control of diabetes in a family practice setting, Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 1999;5:755–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Roaeid RB, Kablan AA. Profile of diabetes health care at Benghazi Diabetes Centre, Libyan Arab JAMAhiriya. East Mediterr Health J. 2007;13:168–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Srinivas G, Suresh E, Jagadeesan M, Amalraj E, Datta M. Treatment-seeking behavior and compliance of diabetic patients in a rural area of south India. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;958:420–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb03017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yousuf M, Ali M, Bano I. Non-compliance of drug therapy in diabetics- Experience at Lahore. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 2001;17:74–8. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang CY, Xie S, Li Y, Li Z. Survey of the drug compliance of type 2 diabetic patients in Chenghai district of Shantou city. Chin J Clin Rehabil. 2005;9:14–5. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bhagat K, Mazayi-Mupanemunda M. Compliance with medication in patients with heart failure in Zimbabwe. East Afr Med J. 2001;78:45–8. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v78i1.9112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Joshi PP, Mohanan CJ, Sengupta SP, Salkar RG. Factors precipitating congestive heart failure–role of patient non-compliance. J Assoc Physicians India. 1999;47:294–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sadik A, Yousif M, McElnay JC. Pharmaceutical care of patients with heart failure. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60:183–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Moodley I. Analysis of a medical aid administrator database for costs and utilisation of benefits by patients claiming for lipid-lowering agents. Cardiovasc J S Afr. 2006;17:140–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Asefzadeh S, Asefzadeh M, Javadi H. Care management: Adherence to therapies among patients at Bu-Alicina Clinic, Qazvin, Iran. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2005;10:343–8. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chizzola PR, Mansur AJ, Luz PL, Bellotti G. Compliance with pharmacological treatment in outpatients from a Brazilian cardiology referral center. Sao Paulo Med J. 1996;114:1259–64. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31801996000500004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dantas RA, Aguillar OM, Santos Barbeira CB. Implementation of a nurse-monitored protocol in a Brazilian hospital: a pilot study with cardiac surgery patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46:261–6. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(01)00162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.El-Gatit AM, Haw M. Relationship between depression and non-adherence to anticoagulant therapy after valve replacement. East Mediterr Health J. 2003;9:12–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kocer A, Ince N, Kocer E, Tasci A. Factors influencing treatment compliance among Turkish people at risk for stroke. J Prim Prev. 2006;27:81–9. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-0020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Olubodun JO, Falase AO, Cole TO. Drug compliance in hypertensive Nigerians with and without heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 1990;27:229–34. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(90)90164-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rotchford AP, Rotchford KM. Diabetes in rural South Africa–an assessment of care and complications. S Afr Med J. 2002;92:536–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wiseman IC, Miller R. Quantifying non-compliance in patients receiving digoxin–a pharmacokinetic approach. S Afr Med J. 1991;79:155–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Matteo M. Variations in patients' adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004;42:200–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114908.90348.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chan DC, Shrank WH, Cutler D, et al. Patient, physician, and payment predictors of statin adherence. Med Care. 2010;48:196–202. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181c132ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gaziano Cardiovascular disease in the developing world and its cost-effective management. Circulation. 2005;112:3547–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.591792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Woolf SH, Johnson RE. The break-even point: when medical advances are less important than improving the fidelity with which they are delivered. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:545–52. doi: 10.1370/afm.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Green CA. What can patient health education coordinators learn from ten years of compliance research? Patient Education & Counseling. 1987;10:167–74. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(87)90096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kesselheim AS, Choudhry NK. The international pharmaceutical market as a source of low-cost prescription drugs for U.S. patients. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:614–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-8-200804150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Bangsberg D. Adherence to HAART: A Systematic Review of Developed and Developing Nation Patient-reported Barriers and Facilitators. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Choudhry NK, Fischer MA, Avorn J, et al. The implications of therapeutic complexity on adherence to cardiovascular medications. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:814–22. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Choudhry NK. Promoting persistence: improving adherence through choice of drug class. Circulation. 2011;123:1584–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.024471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]