Abstract

The most lethal aspect of cancer is the metastatic spread of primary tumors to distant sites. Any mechanism revealed is a target for therapy. In our previous studies, we reported that the invasive activity of the bone metastatic C4-2B prostate cancer cells could be ascribed to the reorganization of the α2β1 integrin receptor and the α2 subunit-mediated association and activation of downstream signaling towards the activation of MMPs. In the present study, we demonstrate that expression of asialoGM1 in C4-2B cells correlates with cancer progression by influencing adhesion, migration and invasion, via reorganization of asialoGM1 and colocalization with integrin α2β1. These observations reveal an uncharacterized complex of asialoGM1 with the integrin α2β1 receptor promoting cancer metastatic potential through the previously identified integrin-mediated signaling pathway. The present findings promote further understanding of mechanisms by which glycosphingolipids modulate malignant properties and the results obtained here propose novel directions for future study.

Keywords: adhesion, migration, invasion, extracellular matrix, glycosphingolipid, prostate cancer

Introduction

Glycosphingolipids (GSLs), including gangliosides are common components of cell membranes. They are known to serve as major cell surface antigens, in particular tumor-associated antigens, as receptors for bacterial and viral toxins, involved in the process of microbial infection, and as mediators of cell adhesion/recognition and to modulate cell motility and signal transduction (1).

Several studies indicate that the expression of tumor-associated GSLs result from oncogenic transformation, and suggest that GSL expression varies with metastatic potential (2,3). Such a correlation has been shown for human melanoma and glioma cells as well as for renal cell carcinoma, where specific GSLs are found to be selectively expressed in invading tumor cells (4–6). Basically all GSLs, in tumor and normal cells, are clustered, interact with specific cell surface components and organize with intracellular signaling molecules, thereby profoundly affecting cellular function and phenotype (1,7).

In our previous study, we reported that the adhesive and invasive behavior of the bone metastatic derivative C4-2B cells of the LNCaP prostate cancer progression model are mediated through the lateral reorganization of the integrin α2β1 receptor and the α2 subunit-mediated association and subsequent activation of the FAK/src/paxillin/JNK/Rac pathway, resulting in enhanced activation of matrix metalloproteinases, MMP-2 and MMP-9 (8). In addition, we pointed out that the obtained results should not be viewed as the mechanism of a single player, instead we evoke that α2β1 integrin receptors are key components of a complex with other membrane proteins and lipids, initiating downstream signaling events via the α2 subunit of the integrin α2β1 receptor in C4-2B cells. Since GSLs are known to play crucial roles in integrin-mediated cell adhesion, migration and invasion through their effect on signal transduction pathways, which are influenced by cross-talk with other functional membrane components including tetraspanins and growth factor receptors (1,9,10), we continued our studies by investigating a possible functional role for GSLs in complex with α2β1 integrin receptors in the LNCaP progression model.

In this study, we demonstrate that in addition to the previously reported differences between LNCaP and C4-2B cells, namely increased adhesiveness to and invasiveness into collagen I of C4-2B cells (8), the velocity at which C4-2B cells migrate is higher as compared to the parental LNCaP cells. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the cell surface expression of asialoGM1 correlates with cancer progression and that asialoGM1 is a crucial factor to regulate cancer metastatic potential and this via lateral redistribution of asialoGM1 and colocalization with integrin α2β1 receptors. In conclusion, this is the first study to report that asialoGM1 is expressed on prostate cancer cells and that asialoGM1 plays a significant role in prostate cancer progression.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and other reagents

The antibodies against integrin α2β1, α3β1, α5β1, αvβ1 and αvβ1 receptors, GD2 and GD3 were from Millipore (Billerica, MA). The ganglioside antibodies to GM1, asialoGM1, GM2 were from EMD Biosciences (Gibbstown, NJ), while Gb3 and GM3 anti-bodies were purchased from Glycotech (Gaithersburg, MD). Secondary biotinylated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse, FITC-labeled anti-mouse, FITC- and TR-labeled anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). BCA protein assay reagent kit was from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Vectastain ABC-AmP kit was obtained from Vector Laboratories.

Cell culture

The human prostate cancer LNCaP cells and the derivative C4-2B cell line were a kind gift from Dr M. Bisoffi (UNM, School of Medicine, NM) (11) and were grown in RPMI-medium supplemented with 5% FBS, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C equilibrated with 5% CO2 in humidified air.

Wound healing assay/scratch assay

Cells were grown in 6-well plates until confluency and washed twice with PBS. After wounding the cells, 3 ml of medium in the presence or absence of function blocking integrin antibodies and/or ganglioside antibodies were added. After 24 and 48 h, the distances over which the cells migrated were measured and expressed as migratory velocity (µm/h).

Flow cytometry analysis

Cells were detached and suspended as single cells using 10 mM EDTA and 20 mM HEPES buffer in the appropriate medium. The EDTA was neutralized with CaCl2 and MgSO4, and washed again with medium containing 0.1% BSA. For permeabilization, cells were incubated with Tween-20 (0.5% in PBS). Cells (2.5×105) were incubated with asialoGM1 and GM1 antibodies, followed by secondary FITC-labeled antibodies. After washing, 1×104 stained cells were analyzed for fluorescence using the Cell Lab Quanta SC MPL (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL). Stainings without primary antibody were used as controls.

Cell adhesion assay

Cells were detached with trypsin/EDTA and resuspended at 5×105 cells/ml in RPMI supplemented with 2% FBS in the presence or absence of function blocking integrin α2β1 and/or asialoGM1 and GM1 ganglioside anti-bodies. Cell suspension (100 µl) was added to collagen I-precoated 96-well plates (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). After 90-min incubation at 37°C, wells were washed three times with PBS. The remaining cells were solubilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 and acid phosphatase activity was measured by addition of p-nitro-phenyl phosphate (Sigma). Absorbance values of the lysates were determined on a microplate reader at 405 nm.

Collagen type I invasion assay

Six-well plates were filled with 1.25 ml neutralized type I collagen (0.09%, Millipore) and incubated for 1 h at 37°C to allow gelification. For invasion into collagen type I, cells were harvested using trypsin/EDTA and seeded on top of collagen type I gels. Cultures were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in the presence or absence of function blocking integrin α2β1 and/or asialoGM1 and GM1 ganglioside antibodies. Numbers of cells penetrating into the gel or remaining at the surface were counted, using an inverted microscope and expressed as the invasion index, being the percentage of invading cells over the total number of cells (12).

Confocal-fluorescence immunostaining

Fluorescence microscopy

Cells were suspended in trypsin/EDTA and stained by an indirect immunofluorescence technique. Briefly, cells were incubated on a rotator at 4°C for 1 h with antibodies against integrin α2β1, asialoGM1 and GM1, washed three times with CMF-HBSS and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in CMF-HBSS for 20 min. Fixed cells were washed three times with CMF-HBSS and incubated with FITC-labeled anti-mouse secondary antibody. Stained cells were mounted with a drop of Glycergel mounting medium (Dako Corp., Carpinteria, CA) containing 1% 1,4-diazabicyclo [2.2.2]octane (fluorescence stabilizer). Fluorescence was observed by fluorescence microscopy (Olympus IX51 with Olympus U-CMAD3 camera).

Confocal microscopy

Cells were grown on glass cover slips (diameter, 12 mm) placed in 24-well plates. The glass cover slips were removed, washed and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde. Next, fixed cells were washed and incubated with primary antibodies against asialoGM1, GM1 and integrin α2β1, followed by incubation with FITC-labeled and TR-labeled secondary antibodies. Stained cells were mounted with Glycergel mounting medium (Dako) containing 1% 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2] octane (fluorescence stabilizer) and confocal fluorescence images were acquired using a Leica TCS SP2 confocal system (Leica Microsystems, Heidelberg, Germany). Images were taken using a 63× NA 1.32 objective. The standard LCS software was used. Cross-talk between different fluorochromes, which could give rise to false-positive colocalization of the signals, was totally avoided by careful selection of the imaging conditions. Standard filter combinations and Kalman averaging was used.

Co-immunoprecipitation of cell surface molecules

Cells at 70% confluency were lysed, using 0.5 ml lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 1% NP-40 and the following inhibitors: aprotinin (10 µg/ml), leupeptin (10 µg/ml), PMSF (1.72 mM), NaF (100 mM), NaVO3 (500 µM), and Na4P2O7 (500 µg/ml). Lysates, containing 2000 µg protein, were mixed with protein G-Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences, NJ) to preclear non-specific binding. Antibody to asialoGM1 (1:100) was added to the collected supernatant and rotated at 4°C overnight. Subsequently, protein G-Sepharose beads were used to recover the immunocomplexes. Immunoprecipitates were resolved in 150 µl SDS-PAGE sample buffer and heated to 95°C for 5 min. The supernatants were electrophoresed on 7.5% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Immobilon-P) (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). After transfer, membranes were incubated with antibody against integrin α2β1, followed by incubation with a secondary biotinylated antibody and developed by ECL (Vectastain ABC-AmP) detection kit. Membranes were imaged on the BioChemi System and analysis software (UVP, Upland, CA).

Statistical analyses

All treatments were matched and carried out at least three times. Data were analyzed using Excel, for determination of mean, SD, and Student's t-test (95%). Intensity of the immunoblotted bands was quantified by densitometry, using statistical software Scion Image (Scion Corp., Frederick, MD).

Results

Migratory differences between LNCaP and C4-2B cells

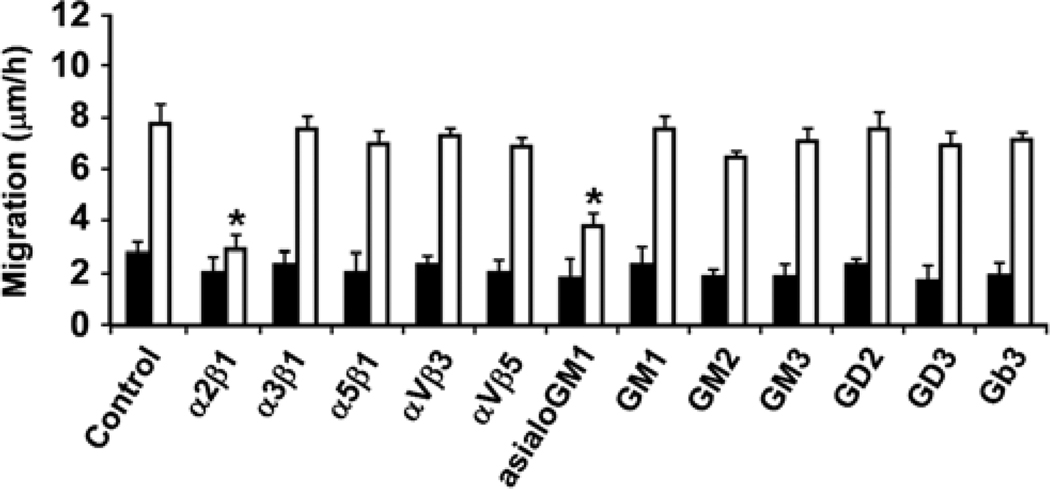

In addition to the previously reported differences between LNCaP and C4-2B cells, namely increased adhesiveness to and invasiveness into collagen I of C4-2B cells (8), we report herein that the velocity at which C4-2B cells migrate is higher as compared to the parental LNCaP cells (Fig. 1). Treatment with function blocking integrin and ganglioside antibodies reveals that integrin α2β1 antibody is the sole integrin antibody able to inhibit the migratory capacity of C4-2B cells, while asialoGM1 is the major ganglioside involved in the migration of C4-2B cells as compared to the parental LNCaP cells (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Migratory differences between LNCaP and C4-2B cells. Migration of LNCaP (closed bars) and C4-2B (open bars) cells. Cells grown in 6-well plates until confluency, were wounded and allowed to grow in the absence or presence of function blocking integrin (5 µg/ml) and/or ganglioside (1:500) antibodies. After 24 and 48 h, the distances over which the cells migrated were measured and results are expressed as migratory velocity (µm/h). Asterisks indicate statistical difference from untreated C4-2B cells (p<0.05).

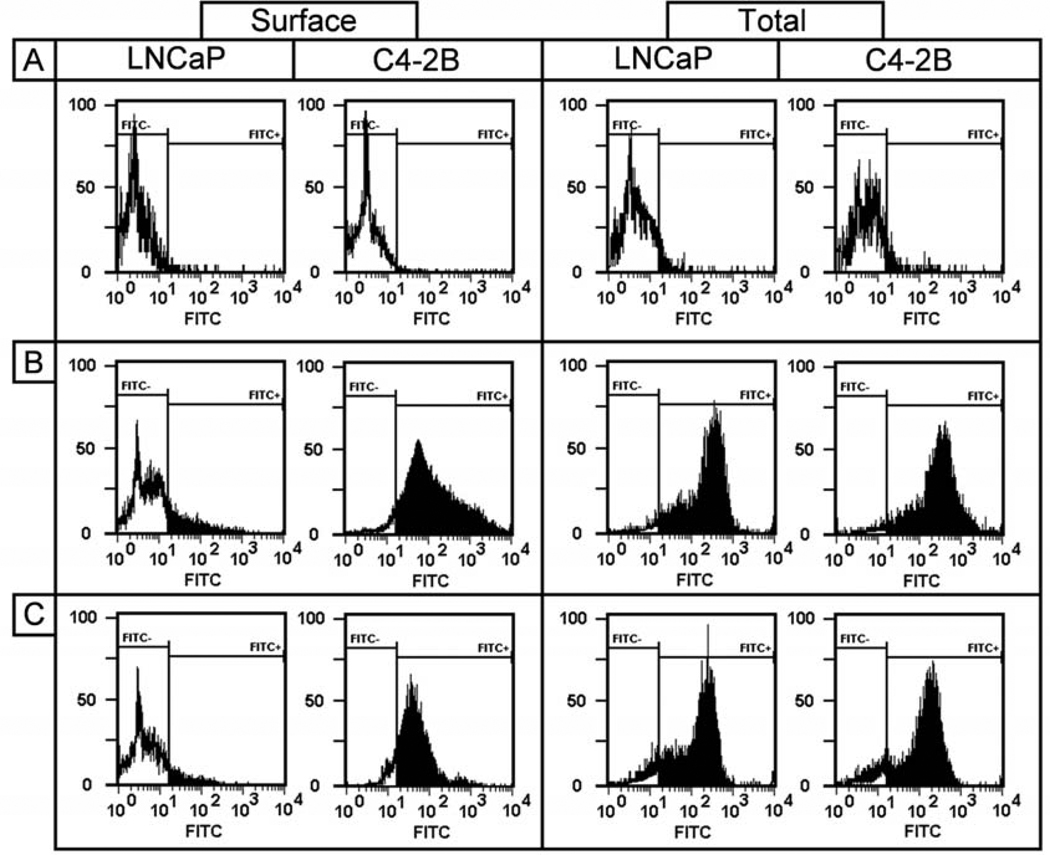

Cell surface and total expression of asialoGM1

We reported that there are no significant differences in the total expression and cell surface expression levels of integrin α2β1 in LNCaP and C4-2B cells (8). Next, we examined the cell surface (left panel) and total expression (right panel) levels of asialoGM1 on LNCaP and C4-2B cells by flow cytometry with respective antibodies, given the minor difference between asialoGM1 and GM1 (Fig. 2). The left panel of Fig. 2 shows that asialoGM1 (Fig. 2B) and GM1 (Fig. 2C) are expressed at the cell surface of C4-2B cells and could not be detected in the parental LNCaP cells as compared to the respective controls (Fig. 2A). The total expression levels were determined after permeabilization and the results in Fig. 2 (right panel) reveal that total expression levels of asialoGM1 (Fig. 2B) and GM1 (Fig. 2C) are comparable for both cell lines. In summary, the data suggest that the increased cell surface expression levels of asialoGM1 and GM1 in the bone metastatic derivative cell line might correlate with cancer progression.

Figure 2.

Cell surface and total expression levels of asialoGM1 and GM1. Left panel, cell surface expression levels of asialoGM1 (B) and GM1 (C) in LNCaP and C4-2B cells. Single cell suspensions were stained by relevant primary antibodies and FITC-labeled secondary antibodies. Right panel, total expression levels of asialoGM1 (B) and GM1 (C) in LNCaP and C4-2B cells, after permeabilization with Tween-20 (0.5% in PBS), followed by incubation with primary antibodies and FITC-labeled secondary antibodies. Control stainings were performed without primary antibody (A). Experiments were performed at least three times.

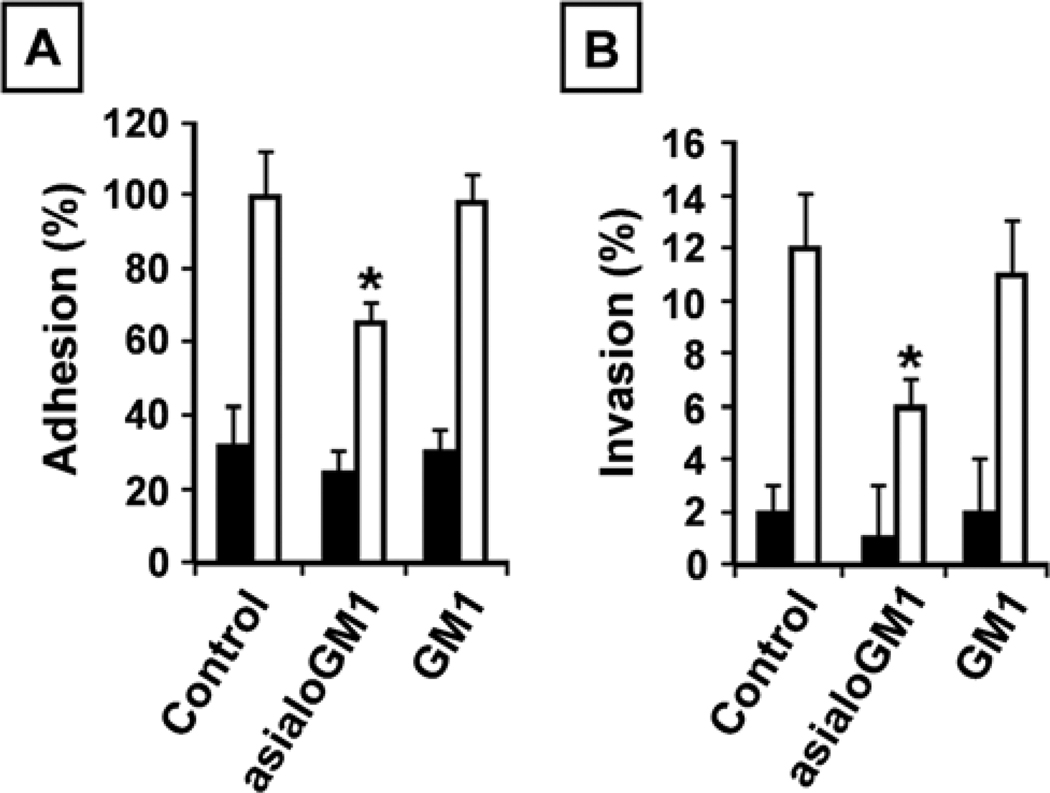

AsialoGM1 mediates adhesion and invasion

Given the pronounced cell surface expression of both asialoGM1 and GM1 in C4-2B cells and the profound influence of asialoGM1 on the migration of C4-2B cells, we investigated whether asialoGM1 and/or GM1 were involved in adhesion to and invasion into collagen I. The results reveal that treatment with GM1 antibody does not affect any of these processes, while asialoGM1 antibody treatment significantly reduces the adhesion to collagen I (Fig. 3A), as well as the invasiveness into collagen I of C4-2B cells (Fig. 3B). Overall, these results suggest that asialoGM1 plays a role in the different processes involved in cancer progression, i.e. adhesion, migration (Fig. 1) and invasion.

Figure 3.

AsialoGM1 mediates adhesion and invasion. (A) Adhesion to collagen I. LNCaP (5×104) (closed bars) and C4-2B (open bars) cells/100 µl, untreated or treated with asialoGM1 or GM1 antibodies (1:500) were seeded in a collagen I precoated 96-well plate. After 90 min, the cells were washed and acid phosphatase activity was measured. The percentage binding was calculated by subtracting non-specific binding and expressed as % adhesion compared to untreated LNCaP and C4-2B cells. Six wells were analyzed in each experiment. (B) Invasion into collagen I. LNCaP (1×104) (closed bars) and C4-2B (open bars) cells, untreated or treated with asialoGM1 or GM1 antibodies (1:500), were seeded on top of collagen type I gels and cultured for 24 h. The invasion index expresses the percentage of invading cells over the total number of cells. All data are means ± SD from three independent experiments, asterisks indicate statistical difference from untreated C4-2B cells (p<0.05).

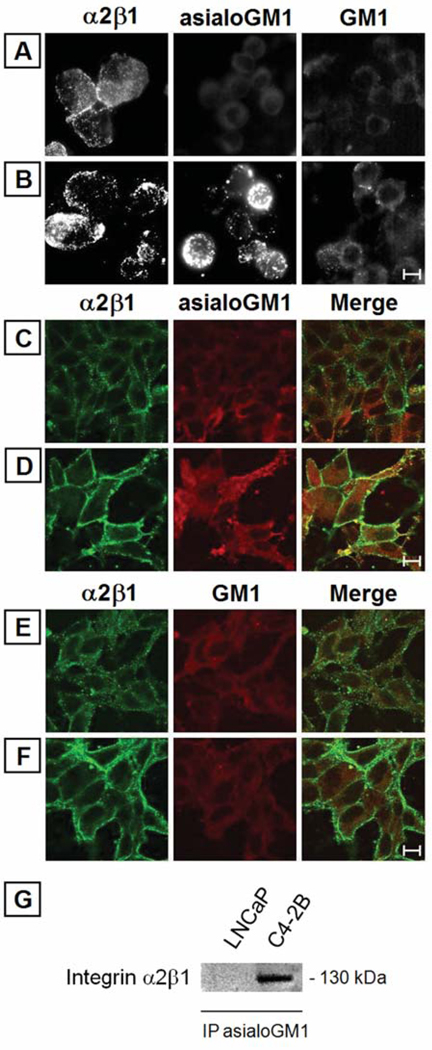

Organization of asialoGM1 and colocalization with integrin α2β1

The integrin α2β1 receptors were found reorganized in the derivative bone metastatic C4-2B cells and these changes in organizational pattern correlated with increased adhesion and cellular invasion. The major alterations in the organizational status, rather than increased expression, were responsible for the initiation and activation of signal transducers in the downstream pathway, leading to invasion via association with the integrin α2 subunit (8). Next, we examined the localization and distribution patterns of asialoGM1 and possible colocalization with integrin α2β1 receptors by fluorescence and confocal microscopy. The fluorescence immunostaining of LNCaP and C4-2B cells in suspension reveals major alterations in cell surface staining pattern for asialoGM1 and integrin α2β1 (8) but not for GM1 in C4-2B cells (Fig. 4B), as compared to the parental LNCaP cells (Fig. 4A). The confocal microscopy images (Fig. 4C–F) also display that asialoGM1 and integrin α2β1 are differentially organized and clustered in C4-2B cells (Fig. 4D), as compared to the parental LNCaP cells (Fig. 4C), and asialoGM1 is found to have colocalized with integrin α2β1 in C4-2B cells, while no such clustering and colocalization of GM1 with integrin α2β1 is found in LNCaP (Fig. 4E) and in C4-2B (Fig. 4F) cells. The close connection is further confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation of asialoGM1, demonstrating the association of integrin α2β1 in C4-2B cells and not in LNCaP cells (Fig. 4G).

Figure 4.

Organization of asialoGM1 and colocalization with integrin α2β1. Organization of integrin α2β1, asialoGM1 and GM1 by indirect fluorescence (A and B) and confocal microscopy (C–F). (A and B) Cell surface staining pattern of integrin α2β1, asialoGM1 and GM1 in LNCaP (A) and C4-2B (B) cells as analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Cells were suspended in trypsin/EDTA and incubated with relevant primary antibodies on a rotator at 4°C for 1 h, fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in CMF-HBSS and labeled with secondary FITC-labeled antibody. Reorganized staining patterns for integrin α2β1 and asialoGM1 are observed in C4-2B cells. (C–F) Co-localization of integrin α2β1 and asialoGM1 in LNCaP and C4-2B cells studied by confocal microscopy. Cells were grown on glass cover slips and double stained by integrin α2β1 and asialoGM1 primary antibodies and FITC- and TR-labeled secondary antibodies. In C4-2B, integrin α2β1 colocalized with asialoGM1 more extensively than in LNCaP cells. Control staining, for (A–F), were performed without primary antibody (data not shown); scale bar, 10 µm. Experiments were performed at least three times. (G) Different level of integrin α2β1/asialoGM1-association in LNCaP versus C4-2B cells. Aliqouts of immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting using the respective antibody. Experiments were performed at least three times.

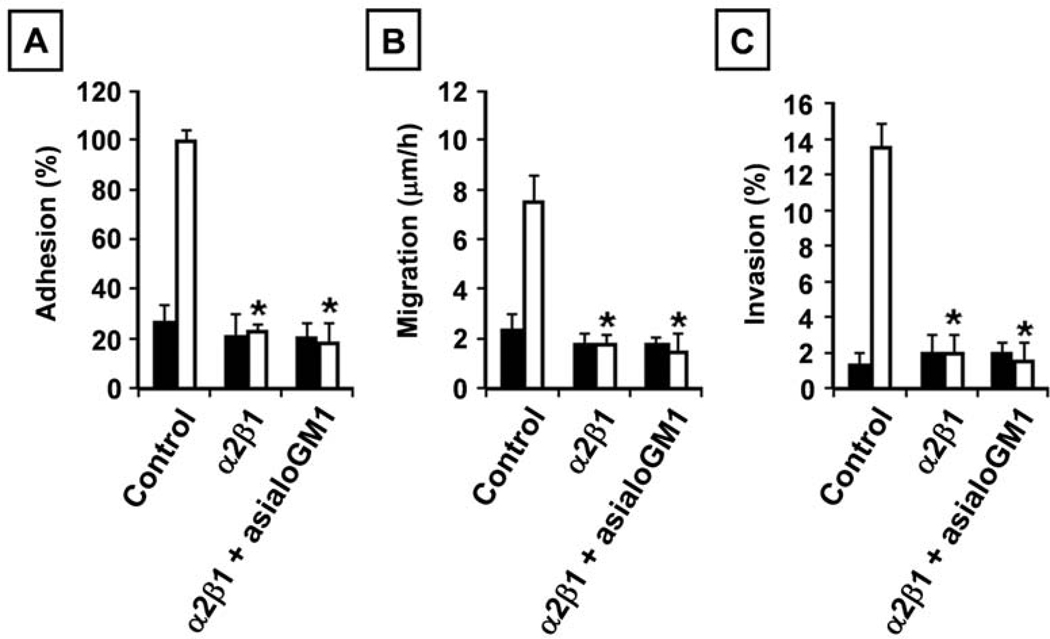

Possible synergistic interaction of asialoGM1 and integrin α2β1

Based on the above data, we wanted to determine the significance of the asialoGM1/integrin α2β1 interaction. Fig. 5A and C show that function blocking of the integrin α2β1 receptor blocks the adhesive and invasive behavior of C4-2B cells in collagen I, which is in line with our previously published results. Additionally, function blocking of integrin α2β1 reduces the migratory capacity of C4-2B cells (Fig. 1). Subsequently, we investigated whether blocking of both integrin α2β1 and asialoGM1 resulted in a synergistic effect. Co-treatment with antibodies against integrin α2β1 and asialoGM1 reduced even more the observed effects, however, not significantly different from the effect of the integrin α2β1 antibody by itself (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Is there a synergistic interaction of asialoGM1 and integrin α2β1? (A) Adhesion to collagen I. LNCaP (5×104) (closed bars) and C4-2B (open bars) cells/100 µl, untreated or treated with asialoGM1 (1:500) and function blocking integrin α2β1 (5 µg/ml) antibodies, were seeded in a collagen I precoated 96-well plate. After 90 min, the cells were washed and acid phosphatase activity was measured. The percentage binding was calculated by subtracting nonspecific binding expressed as % adhesion compared to untreated LNCaP and C4-2B cells. Six wells were analyzed in each experiment. (B) Migration. LNCaP (closed bars) and C4-2B (open bars) cells grown in 6-well plates until confluency were wounded and allowed to grow in the absence or presence of asialoGM1 (1:500) and function blocking integrin α2β1 (5 µg/ml) antibodies. The distances over which the cells migrated were measured, after 24 and 48 h, and results are expressed as migratory velocity (µm/h). (C) Invasion into collagen I. LNCaP (1×104) (closed bars) and C4-2B (open bars) cells, untreated or treated with asialoGM1 (1:500) and function blocking integrin α2β1 (5 µg/ml) antibodies, were seeded on top of collagen type I gels and cultured for 24 h. The invasion index expresses the percentage of invading cells over the total number of cells. All data are means ± SD from three independent experiments, asterisks indicate statistical difference from untreated C4-2B cells (p<0.05).

Discussion

Understanding the metastatic and invasive properties of tumor cells are of crucial importance in tumor malignancy. Every possible mechanism revealed could be a target for prevention or inhibition of tumor progression. Various studies indicate that tumor cell penetration into extracellular matrix (ECM), based on increased motility coupled with ECM-destructive activity is often associated with high metastasis (13). In our previous study, we showed that the bone-metastatic derivative C4-2B cells of the LNCaP progression model display enhanced invasiveness into and adhesiveness to collagen I as compared to the parental LNCaP cells. The observed differences were mediated through the reorganization of the α2β1 receptor, resulting in the activation of a downstream signaling pathway leading to increased activity of matrix metalloproteinases (8).

In the present study we found that, in addition to the markedly enhanced adhesion and invasion activity, C4-2B cells migrate faster than the parental LNCaP cells. Moreover, integrin α2β1 and asialoGM1 were identified as important mediators of cell migration. Suppression of these two molecules using asialoGM1 and integrin α2β1 receptor anti-bodies clearly demonstrated their particular roles in the increased cell migration of C4-2B cells. In contrast, LNCaP cells were scarcely affected by these treatments. Analysis of the cell surface and total expression levels of asialoGM1 and the related GM1 revealed enhanced expression of asialoGM1, at the cell surface in C4-2B cells as compared to LNCaP cells. On the other hand, no significant differences in total expression and cell surface levels were found for the integrin α2β1 receptor in the preceding study (8).

The neutral glycosphingolipid, asialoGM1, is expressed by T cells as well as by natural killer (NK) cells (14) and its expression correlates with the killing activity. Traces of asialoGM1 have also been found in nerve tissues and in cystic fibrosis respiratory epithelial cells (15,16). Furthermore, asialoGM1 has been described as an adhesion receptor for P. aeruginosa to regenerate respiratory epithelial cells (17,18). Moreover, it has been reported that asialoGM1 expression could vary according to the cellular phenotype (19) which is in agreement with our observations showing that the cell surface expression of asialoGM1 correlates with cancer progression and that asialoGM1 is a crucial factor to regulate cancer metastatic potential by influencing adhesion, migration and invasion.

In the immunostaining studies, differences in organizational pattern of asialoGM1 in the cell membrane were observed between LNCaP and C4-2B cells, indicating that reorganization of asialoGM1 correlates with the invasive phenotype. In addition, further microscopy studies revealed that asialoGM1 and integrin α2β1 colocalized in C4-2B cells. These results suggest a close connection of asialoGM1 with integrin α2β1, and co-immunoprecipitation of asialoGM1 in C4-2B cells, confirmed the association with integrin α2β1, while this could not be detected in the parental LNCaP cells.

These observations led us to explore the possibility that asialoGM1 and integrin α2β1 receptors act in synergy in C4-2B cells to mediate alterations in adhesive, migratory and invasive behavior. While no significant reduction was found in the different biological assays under the conditions used in this study, the idea that asialoGM1 and integrin α2β1 work together to achieve the phenotypic changes is plausible since signaling molecules found in the co-immunoprecipitates of asialoGM1 were previously identified as being involved in a major signaling pathway leading to expression of MMPs in C4-2B cells (data not shown).

These observations are in line with several studies demonstrating that glycosphingolipids play crucial roles in integrin-mediated cellular activities thereby affecting signal transduction pathways and that asialoGM1 is able to engage in cytoplasmic signaling networks (1,20). Moreover, there is a high possibility that GSLs are complexed with tetraspanins at the cell surface. Along this line, tetraspanins CD9 and CD82 are identified as motility inhibitors and decreased expression is reported to be associated with increased invasion and metastasis in prostate cancer (21,22). Although the mechanism largely remains unclear, detailed study on CD9 and CD82 indicate that these tetraspanins alone do not inhibit tumor cell motility or invasiveness rather such inhibition occurs through regulating the biological activities of associated proteins, as integrins, and/or reorganizing the components of the cell membrane (1,23). Correspondingly, we could not detect CD9 and CD82 in the co-immunoprecipitates of asialoGM1, although both tetraspanins are present on LNCaP and C4-2B cells (data not shown).

In our previous study, we pointed out that the increased cell adhesion and invasion as well as the activation of the downstream signaling pathway is attributed to major alterations in the organizational status of the α2β1 integrin receptor, rather than to increased expression, and reminded that the observations should not be considered as the mechanism of a single player, but as key components in complex with other crucial molecules (8). Herein, we report that asialoGM1 is reorganized and colocalized with integrin α2β1 in C4-2B cells, suggesting that the interaction of integrin α2β1 and asialoGM1 is necessary to maintain the invasive phenotype. The increased cell surface expression of asialoGM1 in C4-2B cells as compared to the parental LNCaP cells, however, remains at present unexplained. It has been generally accepted that in most cases the major pool of cellular GSLs is localized in the cell surface membrane. Minor sites of location are the subcellular organelles, where GSL metabolism occurs, or the vesicles, or other transport structures, involved in GSL intracellular traffic (24). Based on the latter, we presume the subcellular localization and/or accumulation of asialoGM1 in LNCaP cells, this may point out to the existence of specific sorting mechanisms that regulate the intracellular transport and localization of GSLs or the presence of agents that affect the sorting mechanisms between endosomes/Golgi apparatus and the cell membrane and is currently under investigation.

It is not yet clear why particularly asialoGM1 is involved in metastatic potential and not the related GM1, one possible explanation could be the presence of sialidases at the cell membrane that remove sialic acid from sialylated gangliosides (25). In fact, studies indicate that metastatic potential does not always parallel the sialic acid levels, instead there is evidence to believe that the altered sialidase expression is more important for metastases. In addition, increase in neuraminidase NEU3, is often detected in prostate cancer and correlates with the histological differentiation grade (26). Another possibility could be the metabolic recycling of sugar residues of glycosphingolipids, especially of sialic acids, since this is a way of saving energy and channeling sugars to sites of activation, through cytoskeleton microfilaments (24). Further studies based on these possibilities are in progress.

In conclusion, the present study reports that cell surface expression of asialoGM1 correlates with cancer progression and suggests that the reorganization and interaction of asialoGM1 with integrin α2β1 receptors are crucial in the regulation of cancer metastatic potential. To the best of our knowledge this is the first study to report that asialoGM1 is expressed on prostate cancer cells and that asialoGM1 plays a significant role in prostate cancer progression.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs L. Oomen and L. Brocks (Department of Tumor Biology, The Netherlands Cancer Institute, The Netherlands) for assistance with the confocal microscopy analysis. This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health [RR-16480] under the INBRE program of the National Center for Research Resources, the New Mexico Tech startup funds and the New Mexico Department of Veteran Services.

Abbreviations

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- GSL

glycosphinglipid

- JNK

c-jun NH2 terminal kinase

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

References

- 1.Hakomori SI. Structure and function of glycosphingolipids and sphingolipids: recollections and future trends. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780:325–346. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hakomori S. Tumor malignancy defined by aberrant glycosylation and sphingo(glycol)lipid metabolism. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5309–5318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruggieri S, Mugnai G, Mannini A, Calorini L, Fallani A, Barletta E, Mannori G, Cecconi O. Lipid characteristics in metastatic cells. Clin Exp Metastases. 1999;17:271–276. doi: 10.1023/a:1006662811948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furukawa K, Hamamura K, Nakashima H, Furukawa K. Molecules in the signaling pathway activated by gangliosides can be targets of therapeutics for malignant melanomas. Proteomics. 2008;8:3312–3316. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Von Holst H, Nygren C, Boström K, Collins VP, Fredman P. The presence of foetal ganglioside antigens 3'-isoLLM1 and 3'6'-isoLD1 in both glioma tissue and surrounding areas of the human brain. Acta Neurochir. 1997;139:141–145. doi: 10.1007/BF02747194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoon DS, Okun E, Neuwirth H, Morton DL, Irie RF. Aberrant expression of gangliosides in human renal cell carcinomas. J Urol. 1993;150:2013–2018. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35956-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohkawa Y, Miyazaki S, Miyata M, Hamamura K, Furukawa K, Furukawa K. Essential roles of integrin-mediated signaling for the enhancement of malignant properties of melanomas based on the expression of GD3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;373:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Slambrouck S, Jenkins AR, Romero AE, Steelant WFA. Reorganization of the integrin α2 subunit controls cell adhesion and cancer cell invasion in prostate cancer. Int J Oncol. 2009;34:1717–1726. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toledo MS, Suzuki E, Handa K, Hakomori S. Effect of ganglioside and tetraspanins in microdomains on interaction of integrins with fibroblast growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16227–16234. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Todeschini AR, Dos Santos JN, Handa K, Hakomori S. Ganglioside GM2-tetraspanin CD82 complex inhibits met and its cross-talk integrins providing a basis for control of cell motility through glycosynapse. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8123–8133. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611407200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thalmann GN, Sikes RA, Wu TT, Degeorges A, Chang SM, Ozen M, Pathak S, Chung LW. LNCaP progression model of human prostate cancer: androgen-independence and osseous metastasis. Prostate. 2000;44:91–103. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(20000701)44:2<91::aid-pros1>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sigstedt SC, Hooten CJ, Callewaert MC, Jenkins AR, Romero AE, Pullin MJ, Kornienko A, Lowrey TK, van Slambrouck S, Steelant WF. Evaluation of aqueous extracts of Taraxacum officinale on growth and invasion of breast and prostate cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2008;32:1085–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geho DH, Bandle RW, Clair T, Liotta LA. Physiological mechanisms of tumor-cell invasion and migration. Physiology. 2005;20:194–200. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00009.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore ML, Chi MH, Goleniewska K, Durbin JE, Peebles RS., Jr Differential regulation of GM1 and asialo-GM1 expression by T cells and natural killer (NK) cells in respiratory syncytial virus infection. Viral Immunol. 2008;21:327–339. doi: 10.1089/vim.2008.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dasgupta S, van Halbeek H, Hogan EL. Ganglio-N-tetraosylceramide (GA1) of bovine and human brain. Molecular characterization and presence in myelin. FEBS Lett. 1992;301:141–144. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81234-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saiman L, Prince A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa pili bind to AsialoGM1 which is increased on the surface of cystic fibrosis epithelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:1875–1880. doi: 10.1172/JCI116779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krivan HC, Ginsburg V, Roberts DD. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pseudomonas cepacia isolated from cystic fibrosis patients bind specifically to gangliotetraosylceramide (AsialoGM1) and gangliotriaosylceramide (AsialoGM2) Arc Biochem Biophys. 1988;260:493–496. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Bentzmann S, Roger P, Dupuit F, Bajolet-Laudinat O, Fuchey C, Plotkowski MC, Puchelle E. Asialo GM1 is a receptor for Pseudomonas aeruginosa adherence to regenerating respiratory epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1582–1588. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1582-1588.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Enzan H, Hiroi M, Saibara T, Onishi S, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto H, Hara H. Immunoelectron microscopic identification of asialoGM1-positive cells in adult rat liver. Virchows Arc B Cell Pathol. 1991;60:389–398. doi: 10.1007/BF02899571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNamara N, Basbaum C. Signaling networks controlling mucin production in response to Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Glycoconj J. 2001;18:715–722. doi: 10.1023/a:1020875423678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang JC, Bégin LR, Bérubé NG, Chevalier S, Aprikian AG, Gourdeau H, Chevrette M. Down-regulation of CD9 expression during prostate carcinoma progression is associated with CD9 mRNA modifications. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2354–2361. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong JT, Lamb PW, Rinker-Schaeffer CW, Vukanovic J, Ichikawa T, Isaacs JT, Barrett JC. KAI1, a metastasis suppressor gene for prostate cancer on human chromosome 11p112. Science. 1995;268:884–886. doi: 10.1126/science.7754374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lazo PA. Functional implications of tetraspanin proteins in cancer biology. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1666–1677. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tettamanti G. Ganglioside/glycosphingolipid turnover: new concepts. Glycoconj J. 2004;20:301–317. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000033627.02765.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyagi T, Wada T, Yamaguchi K, Hata K. Sialidase and malignancy: a minireview. Glycoconj J. 2004;20:189–198. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000024250.48506.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyagi T. Aberrant expression of sialidase and cancer progression. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2008;84:407–418. doi: 10.2183/pjab/84.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]