Abstract

The motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease (PD) are widely thought to arise from an imbalance in the activity of the two major striatal efferent pathways following the loss of dopamine (DA) signaling. In striatopallidal, indirect pathway spiny projection neurons (iSPNs), intrinsic excitability rises following the loss of inhibitory D2 receptor signaling. Because these receptors are normally counterbalanced by adenosine A2a adenosine receptors, antagonists of these receptors are being examined as an adjunct to conventional pharmacological therapies. However, little is known about the effects of sustained A2a receptor antagonism on striatal adaptations in PD models. To address this issue, the A2a receptor antagonist SCH58261 was systemically administered to DA-depleted mice. After 5 days of treatment, the effects of SCH58261 on iSPNs were examined in brain slices using electrophysiological and optical approaches. SCH58261 treatment did not prevent spine loss in iSPNs following depletion, but did significantly attenuate alterations in synaptic currents, spine morphology and dendritic excitability. In part, these effects were attributable to the ability of SCH58261 to blunt the effects of DA depletion on cholinergic interneurons, another striatal cell type that co-expresses A2a and D2 receptors. Collectively, these results suggest that A2a receptor antagonism improves striatal function in PD models by attenuating iSPN adaptations to DA depletion.

Keywords: adenosine, dopamine, A2a, D2, cholinergic interneuron, medium spiny neuron, striatopallidal, patch clamp, two photon laser scanning microscopy, spine, Parkinson’s disease

Introduction

The motor symptoms of PD have long been thought to be the product of an imbalance in the so-called direct and indirect striatal output pathways, leading to sustained inhibition of the motor thalamus and difficulty in initiating movement (Albin et al., 1989). The best evidence for this hypothesis comes from studies showing that excitability of indirect pathway, striatopallidal spiny projection neurons (iSPNs), is increased following DA depletion. In vivo, the spontaneous activity and synaptic responsiveness of antidromically-identified iSPNs is elevated following depletion (Ballion et al., 2009; Mallet et al., 2006) and reducing their activity ameliorates the motor symptoms associated with DA depletion (Kravitz et al., 2010). In brain slices from depleted mice, dendritic excitability is elevated in iSPNs and plasticity at excitatory glutamatergic synapses becomes biased toward long-term potentiation (LTP) (Day et al., 2006; Kreitzer and Malenka, 2007; Malenka and Bear, 2004; Shen et al., 2008). This elevated excitability triggers a form of homeostatic plasticity (Turrigiano, 2007), leading to a dramatic loss in iSPN excitatory synaptic connections and spines in the days following DA depletion (Day et al., 2006), partially disconnecting the cerebral cortex from the striatum.

Diminishing the change in iSPN excitability following DA depletion should attenuate these adaptations and ameliorate motor impairment. Indirect and direct DA receptor agonists are commonly used to this end, but they often have unwanted side-effects or limited efficacy (Jenner, 2003b). Adenosine A2a receptor (A2aR) antagonists are being examined as potential adjuncts to DA receptor based therapies (Hauser and Schwarzschild, 2005; Jenner, 2003a; Pinna et al., 2010). A2aRs are expressed primarily in the striatum where they are found in iSPNs and cholinergic interneurons, both of which also robustly express D2 receptors (D2Rs) (Hauser and Schwarzschild, 2005; Preston et al., 2000; Song et al.; Surmeier et al., 2009). These two signaling pathways negatively interact at several levels (Canals et al., 2004; Morelli et al., 2007; Svenningsson et al., 1999), suggesting that following DA depleting lesions, not only does D2R signaling fall, but A2aR signaling also rises. This antagonism also suggests that an elevation in A2aR signaling should reduce the ability of residual DA to effectively modulate iSPNs (Fuxe et al., 2007). In agreement with this view, in human patients with PD, it has been hypothesized that A2aR antagonists will decrease the amount of levodopa required to achieve symptomatic relief and, in so doing, decrease dyskinesias (Hauser and Schwarzschild, 2005; Jenner, 2003a; Morelli et al., 2007). In animal models, A2aR antagonists have similar effects (Hauser and Schwarzschild, 2005; Jenner, 2003a; Morelli et al., 2007).

Beyond the immediate effects on cellular excitability to be expected by potentiating residual D2R signaling, it is not clear what antagonizing A2aRs will achieve. Considering recent work (Shen et al., 2008), A2aR antagonists should diminish biasing of synaptic plasticity at glutamatergic synapses toward LTP after DA depletion. This should, in principle, decrease the responsiveness of iSPNs to cortical activity, helping to bring iSPN activity back toward normal levels. However, it remains to be determined whether sustained DA depletion in vivo leads to the potentiation of corticostriatal glutamatergic synapses on iSPNs. Furthermore, it is far from clear whether all the effects of A2aR antagonism are directly mediated by actions on iSPNs. As mentioned above, A2aRs and D2Rs are also co-expressed by cholinergic interneurons and these interneurons exert a powerful effect on iSPNs and the striatal circuitry (Pisani et al., 2007; Tozzi et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2006).

This study was undertaken to provide answers to some of these questions. Our studies show that although the A2aR antagonist SCH58261 did not prevent the loss of spines and synapses following DA depletion, it did significantly reduce other adaptations in iSPNs. Moreover, the SCH58261 effect on at least one of these adaptations – an increase in dendritic excitability – appeared to be mediated indirectly through cholinergic interneurons.

Materials and Methods

Behavior

Catalepsy responses were measured by means of the bar method. The forepaws of the mice were placed over a steel horizontal bar, 0.5 cm in diameter and 10 cm long, fixed at a height of 3 cm above the working surface. The duration of catalepsy was measured as the time from forepaw placement on the bar until the mice removed both forepaws from the bar or climbed over the bar with the hind limbs. Mice were given three trials. Total time was calculated as the sum of the 3 trials with a maximum time of 15 min. The bar test was performed 4 hours after drug administration to coincide with the time of electrophysiology and Ca2+ imaging experiments that were performed on the fifth day of drug administration 4 hours after the last injection.

6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) DA depletion

6OHDA DA depletion was produced by a unilateral lesion of the nigrostriatal system by 6-OHDA injection into the medial forebrain bundle (MFB). In brief, mice at postnatal day 23–28 were anesthetized with a SurgiVet isoflurane vaporizer (Smiths Medical PM, Inc., Norwell, MA). After immobilization on a stereotaxic frame (Model 940, David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) with a Cunningham adaptor (Harvard Apparatus, USA), a hole was drilled (~1 mm diameter) at 0.7 mm posterior and 1.1 mm lateral to bregma for injection into the MFB (0.7 AP = anterior-posterior, 1.1 ML = medial-lateral, 4.8 DV = dorsal-ventral). 1 µL of 6-OHDA HCl was dissolved at a concentration of 3.5 µg/µl saline with 0.02% ascorbate and injected using a calibrated glass micropipette (2-000-00, Drumond Scientific Company, Broomall, PA), at a depth of 4.8 mm from the surface of the skull, conducting at a rate of 0.02 µl/min. The micropipette was left in situ for another 30 minutes after the injection to maximize tissue retention of 6-OHDA and decrease capillary spread upon pipette withdrawal. Electrophysiological experiments were performed 3–4 wks later.

Brain Slice Preparation

Horizontal brain slices (275 µm) were obtained from 27–37day old BAC D2 or D1 transgenic mice following procedures approved by the Northwestern University Animal Care and Use Committee and guidelines of the National Institutes of Health. The mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (Baxter, Deerfield, IL) and decapitated. Brains were rapidly removed and sectioned in oxygenated, ice-cold, artificial cerebral spinal fluid (ACSF) using a Leica VT1000S vibratome (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). The ACSF contained the following (in mM): 126 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 1 NaH2PO4, and 16.7 D-(+)-glucose. The slices were transferred to a holding chamber where they were incubated in ACSF at 35°C for 30 min, after which they were stored at room temperature until whole-cell recording experiments (1–5 hours). The external ACSF solutions were bubbled with 95%O2/5%CO2 at all times to maintain oxygenation and a pH≈7.4. The solutions were periodically checked and adjusted to maintain physiological osmolality (300 mOsm/l).

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were obtained using standard techniques. Slices were transferred to a submersion-style recording chamber mounted on an Olympus BX51-WI upright, fixed-stage microscope (Melville, NY). The slices where continuously perfused with oxygenated 1.5 ml/min ACSF at room temperature. For strEPSC voltage-clamp experiments, pipettes (3–5 MΩ) were filled with a Cs+ internal solution containing the following (in mM): 120 CsMeSO3, 15 CsCl, 8 NaCl, 10 TEA-Cl, 10 HEPES, 2–5 QX-314, 0.2 EGTA, 2 Mg-ATP, 0.3 Na-GTP, pH 7.3 adjusted with CsOH, and were performed at room temperature. Ca2+ was replaced with Sr2+ and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5- methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid (AMPA) mediated quantal events (strEPSCs) were collected during a 300-ms period beginning 50 ms following each stimulus (delivered once every 30 s) in an external ACSF solution containing 50 µM D-APV, 10 µM (−) SR95531 (gabazine), 2 mM Sr2+ and 0 Ca2+. Miniature events were analyzed using Minianalysis software (Synaptosoft, Decatur, Georgia) with detection parameters set at greater than 5 pA amplitude and individually verified. For each cell, at least 300 strEPSCs were taken for constructing cumulative probability plots and calculating mean strEPSC amplitudes and frequencies. Stimulation (50–200 µs) was performed using steel concentric electrodes (Frederick Haer & Co, Bowdoin, ME). The corticostriatal afferents were stimulated by placing the stimulation electrode between layer V and VI in the cortex (Fig. 2a).

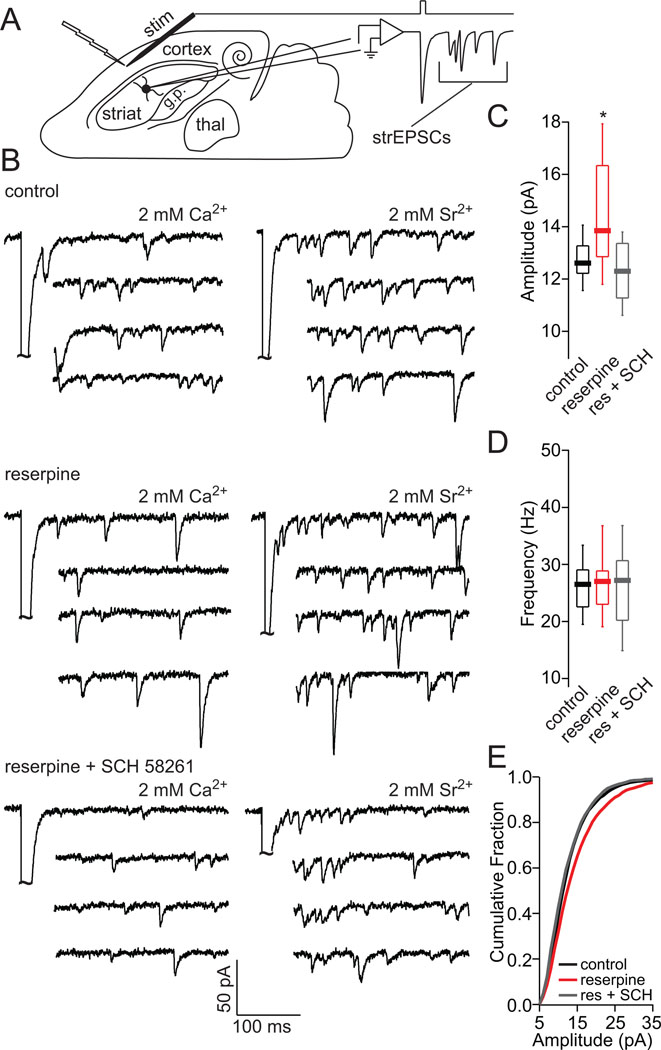

Figure 2.

SCH58261 treatment normalizes increased cortical strEPSCs amplitude in iSPNs of reserpinized mice. (A) Horizontal diagram of mouse brain with recording setup. (B) Sample traces of strEPSCs in iSPNs evoked by cortical stimulation in the presence of 2 mM Ca2+ or 2 mM Sr2+/0 Ca2+. (C) Box-plot summary showing a significant increase in strEPSC amplitude at corticostriatal synapses of iSPNs of reserpinized mice as compared to control and SCH58261 + reserpine iSPNs. (D) Box-plot summary of asynchronous release frequency. (E) Cumulative amplitude plot of strEPSCs in 2 mM 2 mM Sr2+/0 Ca2+ solution evoked by cortical stimulation. The asterisk indicates statistical significance from control.

2-photon laser scanning microscopy (2PLSM), Ca2+ imaging, and spine morphology

Slices were transferred to a submersion-style recording chamber mounted on an Olympus BX51-WIF upright, fixed-stage microscope (Melville, NY). The slices where continuously perfused with oxygenated 1.5 ml/min ACSF at room temperature. D2 (BAC D2) receptor expressing SPNs were identified by somatic eGFP two photon excited fluorescence using an Ultima Laser Scanning Microscope (2PLSM) system (Prairie Technologies, Middleton, WI). A DODT contrast detector system was used to provide a bright-field transmission image in registration with the fluorescent images. The green GFP signals (490–560 nm) were acquired using 810 nm excitation (Verdi/Mira laser: Coherent Laser Group, Santa Clara, CA). SPNs were patched using video microscopy with a Hitachi CCD camera (model KP-M2RN, Tokyo, Japan) and an Olympus UIS1 60X/0.9 NA water-dipping lens. Patch electrodes were made by pulling BF150-86-10 glass on a P-97 Flaming/Brown micropipette puller (Sutter Instrument Co., Novato, CA). The pipette solution contained the following (in mM): 135 KMeSO4, 5 KCl, 5 HEPES, 2 MgATP, 0.5 Na2GTP, 10 phosphocreatine-Na, pH=7.25–7.3 with KOH, 270mOsm/l. Electrophysiological recordings were obtained with a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA) and then digitized with the scanning computer (PCI MIO-16E-4, National Instruments, Austin, TX). The stimulation, display and analysis software was a custom-written shareware package, WinFluor (John Dempster, Strathclyde University, Glasgow, Scotland; UK). WinFluor automated and synchronized the two-photon excited fluorescence with the electrophysiological stimulation. As measured in the bath, the pipette resistance was ~3 MΩ. High resistance (> 1 GΩ) seals were formed in voltage-clamp mode on somata. After patch rupture, the series-resistance decreased to 10–15 MΩ. The inclusion of Alexa 568 (50 µM) in the pipette allowed visualization of cell bodies, dendrites, and spines. Following patch rupture somata were current-clamped and monitored, the internal solution was allowed to equilibrate for 15–20 minutes before imaging. The laser-scanned images were acquired with 810 nm light pulsed at 90 MHz (~250 fs pulse duration). Power attenuation was achieved with two Pockels cells electro-optic modulators (models 350–80 and 350–50, Con Optics, Danbury, CT). The two cells were aligned in series to provide an enhanced modulation range for fine control of the excitation dose (0.1% steps over four decades). For 2PLSM imaging of Ca2+ transients, the neurons were filled via the patch pipette with the Ca2+ indicator Fluo-4 (200 µM). A burst of 3 bAPs were generated by injecting current pulses (2 nA, 2 ms) at 50 Hz. Green fluorescent line scan signals were acquired (as described above) at 6 ms per line and 512 pixels per line with 0.08 µm pixels and 10 µs pixel dwell time. The line scan was started 200 ms before the stimulation protocol and continued 1.3 s after the stimulation to obtain the background fluorescence and to record the decay of the optical signal after stimulation. To reduce photo-damage and photobleaching, the laser was fully attenuated using the second Pockels cell at all times during the scan except for the 500 ms period directly flanking the stimulation protocol. For analysis of the Ca2+ transient, the Fluor-4 fluorescence (G signal) was normalized to Alexa Fluor 568 fluorescence (R signal) (G/R ratio) and the area under the curve was calculated. The glutamate and GABA receptor blockers (in µM) 5 NBQX diNa, 1 MPEP HCl, 50 CPCCoEt, 50 D-APV, 10 Sr-95531 HBr, 1 CGP55845 were bath applied throughout the imaging experiments by dissolving them in the external ACSF. High magnification maximum projection images of distal dendrite segments (30–50 µm in length, with a minimum distance of 90 µm away from the soma) were acquired with 0.072 µm2 pixels with 10 µs dwell time; 30–50 images were taken with 0.2 µm focal steps. Maximum projection images of the soma and dendrites were acquired with 0.36 µm2 pixels with 10 µs pixel dwell time; ~80 images were taken with 1 µm focal steps. Projection stacks were deconvolved with AutoDeblur (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD) and analyzed using NeuronStudio (CNIC, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY). For spine counting and morphology analysis high magnification distal dendrite projections were used. Dendrites were initially auto-constructed and inspected for congruency. Spines were then auto-detected and -classified and individually verified. Noise that was classified as spines was discarded. Cell, dendrite, and spine 3-D perspective images were rendered using Imaris (Bitplane, St. Paul, MN).

Data analysis and statistics methods

Data analysis was done with Clampfit 9.2 (Molecular Devices, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA), Igor Pro 5.0 (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR), Matlab R2009b (Mathworks, Natic, MA) and Minianalysis software (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA). Statistical analyses were performed using Sigmastat 3.5 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA). Summary data are reported as average ± standard error or medians. Bar graphs of average + SE and box plots were used for graphic illustration of data. Non-matched samples were analyzed with the nonparametric Mann-Whitney rank sum test.

Reagents and chemicals

All reagents were obtained from Sigma except KMeSO4 (ICN Biochemicals Aurora, OH), Na2GTP (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN), SR95531, D-APV, CGP55845, NBQX diNa, MPEP HCl, CPCCoEt, SCH58261 (Tocris, Ellisville, MO).

Results

A2aR antagonism reduced reserpine-induced catalepsy

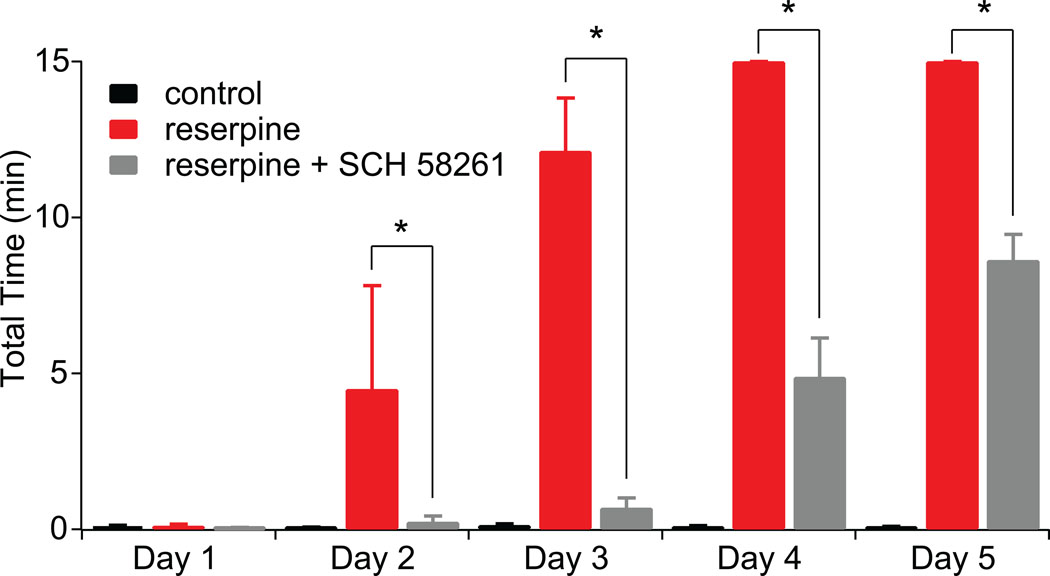

To validate our treatment regimen, the behavioral consequences of the A2aR antagonist SCH58261 on reserpine-induced catalepsy were examined. Previous work (Shiozaki et al., 1999) has shown that the A2aR antagonist KW-6002 reduced catalepsy in mice 24 hrs after a single injection of reserpine. To test the ability of SCH58261 to reproduce this effect, catalepsy was assessed using the bar test 4 hrs after reserpine injection. Reserpine treatment (5 mg/kg/day) alone progressively increased the total time on the bar (a measure of catalepsy) (Fig. 1). Co-administration of SCH58261 (5 mg/kg/day) significantly reduced catalepsy measured on days 2, 3, 4, and 5 (Fig. 1; control: n=4; reserpine: n=4; reserpine + SCH: n=4; p<0.05, Repeated Measures ANOVA, Bonferroni post hoc). These results demonstrate that A2aR antagonism with SCH58261 at the given dose had a significant effect on DA-depletion induced motor behavior. The anatomical and physiological correlates of this effect were then pursued in brain slices from treated mice.

Figure 1.

SCH58261 treatment protects against the development of reserpine-induced catalepsy in mice. Bar graph summary of catalepsy in D2R BAC mice that received control saline, reserpine, or reserpine + SCH58261 as measured by the bar method. Total time was calculated as latency of decent in 3 trials with a maximum latency of 15 min. Catalepsy was significantly decreased in mice that received reserpine + SCH58261 as compared to reserpine treated mice on days 2–5. The asterisk indicates statistical significance.

A2aR antagonism blunted alterations in corticostriatal synaptic currents following DA depletion

Following DA-depletion, D2R stimulation is lost, biasing glutamatergic synaptic plasticity in iSPNs toward an A2aR-dependent LTP (Shen et al., 2008). Because the expression of LTP in SPNs is postsynaptic, this should increase the average amplitude of AMPA receptor mediated unitary synaptic events (Malenka and Bear, 2004). However, it has not been determined whether this happens in vivo following DA depletion. To test this hypothesis, mice were depleted of DA using reserpine and either given concomitant saline or SCH58261 injections for 5 days. At the end of this period, brain slices from these mice were prepared and corticostriatal miniature excitatory synaptic potential currents (strEPSCs) evoked by cortical stimulation in the presence of Sr2+ were measured in D2R expressing iSPNs (Ding et al., 2008). These experiments were conducted using an internal solution containing cesium to maximize the detection of small amplitude events and in the presence of a GABAA receptor antagonist (gabazine) to isolate postsynaptic glutamatergic responses. In iSPNs from saline treated mice, the amplitude, but not the frequency, of cortical strEPSCs was significantly increased (Fig. 2; amplitude: control median=12.6 pA; reserpine median=13.9 pA, p<0.05, Mann-Whitney; frequency: control median=26.6 Hz, reserpine median=27.1 Hz, p>0.05, Mann-Whitney; control n=13, reserpine n=16). In contrast, strEPSC amplitude was reduced in D1 receptor (D1R) expressing, striatonigral, direct pathway spiny projection neurons (dSPNs) (Fig. S1). Administration of the A2aR antagonist SCH58261 (5mg/kg) blocked the increase in strEPSC amplitude with DA-depletion in iSPNs (Fig. 2; reserpine + SCH amplitude median=12.3 pA, frequency median= 27.3 Hz, p>0.05, Mann-Whitney; n=11).

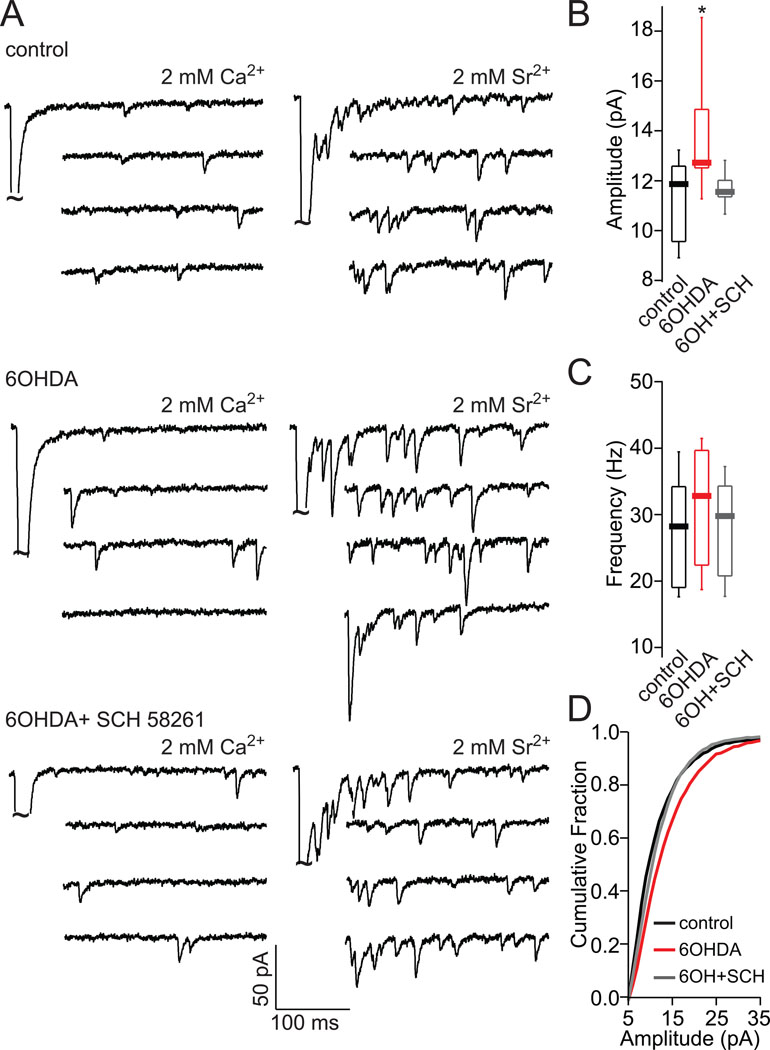

To validate these effects in a second DA depletion model, the medial forebrain bundle of mice was lesioned with 6-OHDA. Three weeks after the lesion, mice were injected with SCH58261 (5mg/kg) or saline for 5 days and then sacrificed for electrophysiological study. The amplitude, but not the frequency, of cortical strEPSCs in iSPNs was significantly increased in animals that received the saline treatment (Fig. 3; amplitude: control median=11.86 pA; 6OHDA median=12.72 pA, p<0.05, Mann-Whitney; frequency: control median=28.342 Hz, 6OHDA median=32.89 Hz, p>0.05, Mann-Whitney; control n=8, 6OHDA n=12). In contrast, administration of SCH58261 reversed the increase in strEPSC amplitude (Fig. 3; 6OHDA + SCH amplitude median=11.55 pA, frequency median=29.90 Hz, p>0.05, Mann-Whitney; n=10).

Figure 3.

SCH58261 treatment normalizes increased cortical strEPSCs amplitude in iSPNs of 6OHDA lesioned mice. (A) Sample traces of strEPSCs in iSPNs evoked by cortical stimulation in the presence of 2 mM Ca2+ or 2 mM Sr2+/0 Ca2+. (B) Box-plot summary showing a significant increase in strEPSC amplitude at corticostriatal synapses of iSPNs of 6OHDA lesioned mice as compared to control and SCH58261 + 6OHDA lesioned iSPNs. (C) Box-plot summary of asynchronous release frequency. (D) Cumulative amplitude plot of strEPSCs in 2 mM 2 mM Sr2+/0 Ca2+ solution evoked by cortical stimulation. The asterisk indicates statistical significance from control. striat – striatum, stim – stimulator, g.p.- globus pallidus, thal – thalamus

A2aR antagonism blunted alterations in spine morphology but not density

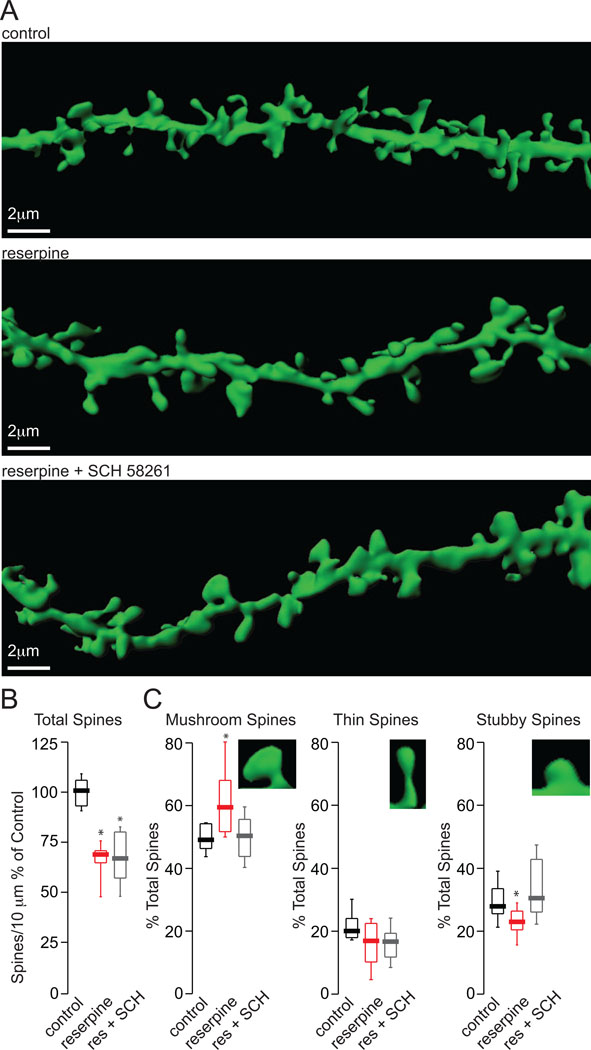

DA depletion triggers a rapid down-regulation in spine and synaptic density in iSPNs that could contribute to the motor symptoms in PD (Day et al., 2006). This loss appears to be a form of homeostatic plasticity triggered by the loss of tonic inhibitory D2R activity. As noted above, one of the consequences of diminishing D2R signaling is that synaptic plasticity becomes biased toward LTP. Because iSPNs are reliant upon glutamatergic synaptic input to generate spikes, this bias could be a significant factor in triggering the homeostatic spine pruning. To test this possibility, SCH58291 was administered in conjunction with reserpine. As shown above, this regimen prevented the elevation in corticostriatal strEPSC amplitude, indicating it disrupted biasing of synaptic plasticity toward LTP. However, the spine loss induced by DA depletion was not significantly reduced by A2aR antagonism (Fig. 4a,b; reserpine median density (% of control)= 68.9%, n=8; reserpine + SCH median=66.9%, n=10; p<0.05, Mann-Whitney).

Figure 4.

SCH58261 treatment normalizes relative spine number in iSPNs in reserpinized mice. (A) Representative rendered high magnification 2PLSM images of distal dendrites (90–120 mm) of iSPNs in 275 mm thick corticostriatal slices from BAC D2R mice that had received the indicated treatment. (B) Box plot summary of total spines/10 µm as % of control. (C) Box plot summaries of mushroom, thin and stubby spines as % of total spines with magnified representations. The asterisk indicates statistical significance from control.

Although A2aR antagonism did not alter spine loss following DA-depletion, it did normalize alterations in the morphology of the remaining spines. In other cell types following the induction of LTP, spines enlarge and become more mushroom-like and the number of smaller ‘stubby’ spines is reduced (presumably because many spines become mushroom-like) (Matsuzaki et al., 2004; Medvedev et al., 2010). Following reserpine treatment, the percentage of mushroom spines increased and the percentage of stubby spines in iSPNs decreased; antagonism of A2aRs prevented this change (Fig. 4c; mushroom: control median (% mushroom)=49.1%; reserpine median=59.5%, n=8; reserpine + SCH median= 50.4%; stubby: control median (% stubby)=27.9%; reserpine median=22.5%; reserpine + SCH median=30.5%; p<0.05, Mann-Whitney). This finding provides a morphological correlate of the effect of A2aR antagonism on cortico-striatal strEPSCs.

A2aR antagonism blunted alterations in dendritic excitability

Another potential factor in the pathology of iSPNs in PD models is a dysregulation of dendritic Ca2+ signaling. Following short-term DA depletion, back-propagating action potential (bAPs) evoke a substantially larger increase in distal (> 100 µm from the soma) intraspine Ca2+ concentration in iSPNs (Day et al., 2008). To determine whether A2aR antagonism would alter dendritic excitability, SCH58261 was co-administered with reserpine and dendritic excitability examined in brain slices using a combination of whole cell patch clamping and Ca2+ imaging with two-photon laser scanning microscopy (2PLSM). As previously described (Day et al., 2008), a short burst of somatic action potentials (3 spikes at 50 Hz) significantly increased intracellular Ca2+ concentration in distal (>100 µm from the soma) spines of iSPNs in DA depleted mice (Fig. 5a–c; control median=0.024, n=34; reserpine median=0.037, n=13; p<0.05, Mann-Whitney). Co-administration of SCH58261 prevented this depletion-induced enhancement of the bAP-evoked dendritic Ca2+ signal (Fig. 5b,c; reserpine + SCH median=0.025, n=33; p>0.05, Mann-Whitney).

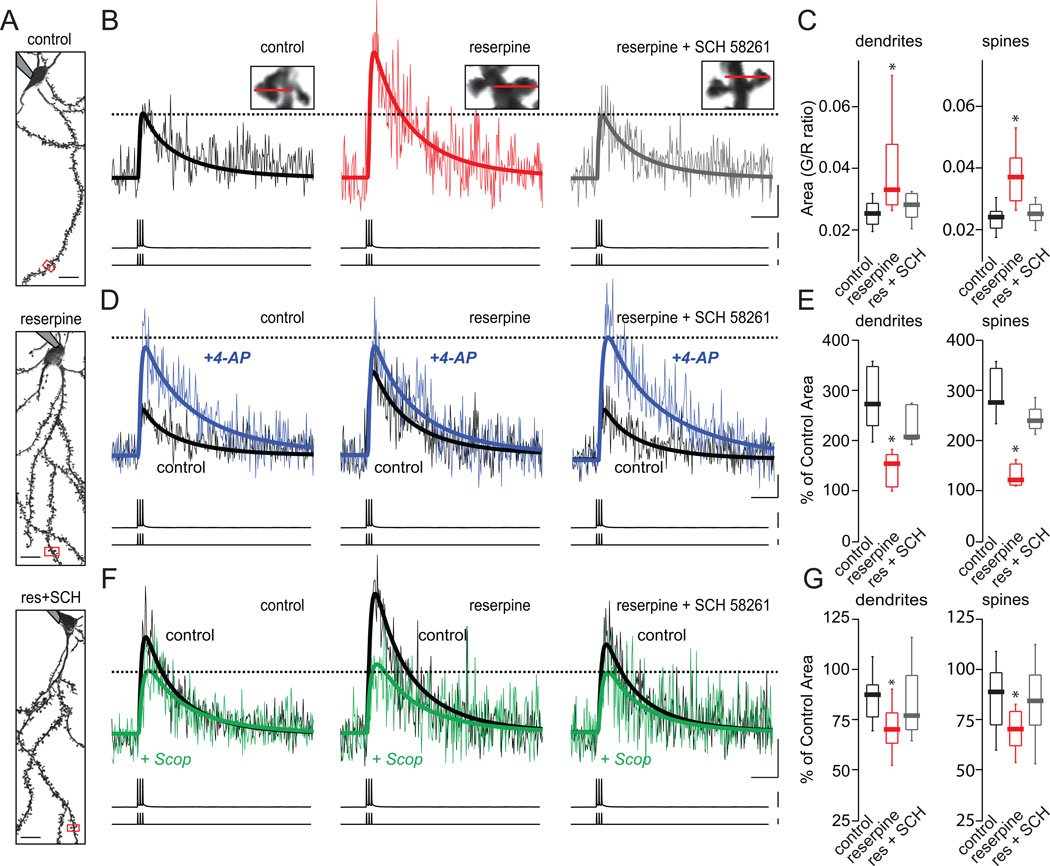

Figure 5.

SCH58261 treatment normalizes increased Kv4 K+ channel mediated BAPs-evoked dendritic Ca2+ signaling in iSPNs of reserpinized mice. (A) Rendered 2PLSM images of iSPNs in 275 µm thick corticostriatal slices from BAC D2R mice that had received the indicated treatment. (B) Ca2+ transients of distal spines (100 µm from soma) elicited by a 3-spike burst (50 Hz) induced by somatic current injection delivered through the recording pipette. Ca2+ signals were detected via line scans, indicated by the red line through the spine shown (high-magnification projections of dendrite segments from the regions outlined by the red boxes in A). (C) Box plot summary of area under the curve of Ca2+ signals in distal spines and dendrites of iSPNs. (D) Representative BAPs-evoked Ca2+ signaling in distal spines (100 µm from soma) of iSPNs in control ACSF (black traces) and in the presence of bath applied 1 mM 4-AP (blue traces). (E) Box plot summary of % of control area under the curve of BAPs-evoked Ca2+ signal in spines and dendrites in the presence of 1 mM 4-AP. (F) Representative BAPs-evoked Ca2+ signaling in distal spines (100 µm from soma) of iSPNs in control ACSF (black traces) and in the presence of bath applied 20 µM scopolamine (green traces). (G) Box plot summary of % of control area under the curve of BAPs-evoked Ca2+ signals in distal spines and dendrites of iSPNs in the presence of 20 µM scopolamine. Scale bars: (A) Horizontal=10µm; (B,D,F) Horizontal=0.2 s, Ca2+ signal=0.05G/R, voltage recording= 100 mV, current injection=1 nA. The asterisk indicates statistical significance from control.

The enhanced Ca2+ signal in distal dendrites following DA-depletion is attributable in part to better invasion of the bAPs because of down-regulation of functional Kv4 K+ channels that oppose invasion (Day et al., 2008). The role of these channels is evident in iSPNs from control mice where treatment with the Kv4 K+ channel antagonist 4-aminopyridine (4-AP, 1 mM) significantly increases the bAP-evoked elevation in intraspine Ca2+ concentration (Fig. 5d,e; control median=275.4%, n=12). Reserpine treatment also increased this bAP-evoked Ca2+ signal and dramatically reduced the impact of 4-AP, in agreement with the hypothesis that depletion was having its effect in part by down-regulating Kv4 K+ channels (Fig. 5d,e; reserpine median=126.6%, n=7; p<0.05, Mann-Whitney). Co-administration of SCH58291 prevented DA depletion from down-regulating the 4-AP sensitive K+ channels regulating the bAP evoked Ca2+ change in iSPNs (Fig. 5d,e; reserpine + SCH median=246.6%, n=10; p>0.05, Mann-Whitney). This effect of A2aR antagonism was significant in both spines and dendritic shafts (Fig. 5c; dendrite: control median=0.025, n=24; reserpine median=0.033, n=12; reserpine + SCH median=0.025, n=26; e; dendrite: control median=281.1%, n=12; reserpine median= 153.6%, n=5; reserpine + SCH median=207%, n=7; p<0.05, Mann-Whitney).

A2aR antagonism blunted depletion-induced muscarinic modulation of dendritic excitability

The ability of A2aR antagonists to attenuate the elevation of iSPN dendritic excitability induced by DA depletion was not a consequence of acute alterations in A2aR signaling. Washing SCH58261 out of the slice or transient (5 minutes) application of SCH58261 had no detectable effect on dendritic excitability (data not shown). Furthermore, brief application of the A2aR agonist had no detectable effect on iSPN dendritic excitability (data not shown).

Previous work by our group has suggested that DA-depletion induced enhancement of dendritic iSPN excitability is dependent upon the down-regulation of dendritic Kv4 K+ channels by acetylcholine (Day et al., 2008). M1R activation inhibits these channels in iSPNs, leading to an increase in the Ca2+ signal at distal spines in response to bAPs. To test the involvement of M1Rs in the normalization of the dendritic Ca2+ signal in iSPNs by SCH58261, the broad spectrum muscarinic receptor antagonist scopolamine (20 µM) was bath applied. In iSPNs of reserpine treated mice, scopolamine reduced the dendritic Ca2+ signal by 30% (Fig 4f,g; reserpine median=70.3%, n=16). This was a significantly greater reduction as compared to the modest effect of scopolamine on the Ca2+ signal at distal spines seen in saline treated controls and reserpinized mice that were co-administered SCH58261, 11% and 16% reduction, respectively (Fig. 4f,g; control median=88.8%, n=22; reserpine + SCH median=84.3%, n=17; p>0.05, Mann-Whitney). These results suggest that M1R activation in iSPNs was reduced in DA depleted mice by SCH58261.

Discussion

The data presented provide new insight into the mechanisms by which antagonism of A2aRs reshape the parkinsonian striatum. Although systemic administration of an A2aR antagonist at behaviorally effective doses did not prevent the pruning of synaptic connections and spines in iSPNs in the days following profound DA depletion, it did prevent the anomalous enhancement of remaining corticostriatal synapses. This effect was evident in measurements of corticostriatal strEPSC amplitude and of spine morphology following depletion. A2aR antagonism also attenuated the rise in iSPN dendritic excitability following DA depletion. This effect appeared to be mediated in part by a normalization of muscarinic receptor activity, suggesting that A2aR antagonism blunted the effects of DA depletion on acetylcholine release. Both consequences of A2aR antagonism should serve to decrease the activity of iSPNs and help re-establish a balance with dSPNs. This balance is widely thought to be important to normal action selection and motor control.

A2aR antagonism blunted depletion-induced alterations in synaptic function

DA depletion creates an imbalance in the excitability of dSPNs and iSPNs, which is thought to underlie the core motor symptoms in PD (Gerfen and Surmeier, 2011). In the classical formulation, this imbalance is created by the immediate effects on cellular excitability produced by the loss of inhibitory D2R signaling in iSPNs and excitatory D1R signaling in dSPNs. Although based upon indirect evidence, subsequent studies have put this model on firm electrophysiological ground (Surmeier et al., 2009).

However, this model fails to account for alterations in A2aR signaling in the parkinsonian state. A number of studies have uncovered a negative interaction between postsynaptic A2aR and D2R signaling, suggesting that the loss of constitutive activation of D2Rs should potentiate A2aR signaling (Fuxe et al., 2005; Salmi et al., 2005). Recent work has elegantly demonstrated this iSPN specific interaction in the regulation of postsynaptic NMDA receptors and Ca2+ channels (Higley and Sabatini, 2010). This shift in signaling should enhance the induction of LTP at corticostriatal synapses (Flajolet et al., 2008; Schiffmann et al., 2003; Shen et al., 2008). In fact, the loss of D2R signaling and the enhancement of A2aR signaling leads to a broadening of the conditions under which LTP can be induced in iSPNs (Shen et al., 2008). Thus, DA depletion not only leads to an elevation in the intrinsic excitability of iSPNs (as posited in the classical model), but a strengthening of excitatory synaptic connections with cerebral cortex pyramidal neurons.

Our results corroborated this conclusion, showing that corticostriatal strEPSC amplitude in iSPNs (but not dSPNs) increased following DA depletion and that this increase was blunted by concomitant A2aR antagonism. In agreement with the postsynaptic locus of LTP expression, strEPSC frequency (a measure of glutamate release probability) was not altered by DA depletion. These experiments isolated corticostriatal synapses by using a slice preparation that preserved connectivity between the cortex and striatum (Ding et al., 2008) and by inducing asynchronous glutamate release in stimulated terminals by replacing extracellular Ca2+ with Sr2+ (Xu-Friedman and Regehr, 2000). This isolation was critical because a substantial (~40%) of the glutamatergic input to SPNs is derived from thalamic neurons whose synaptic properties are distinct from those of cortical projections (Ding et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2004). Interestingly, antagonism of A2aRs weeks after DA depletion induced by 6-OHDA lesions also effectively normalized strEPSC amplitude, arguing that synaptic strength remains malleable and in a neuromodulator-dependent dynamic equilibrium.

Because corticostriatal LTP is expressed postsynaptically, it should be accompanied by morphological changes, including an increase in postsynaptic AMPA receptors (Malenka and Bear, 2004). A growing body of evidence suggests that at axospinous synapses, the induction of LTP is accompanied by a visible increase in spine surface area (Bourne et al., 2007; Harvey and Svoboda, 2007; Matsuzaki et al., 2004). This increase can be manifested as a shift from thin to mushroom-like spines (Matsuzaki et al., 2004). Our studies are consistent with this model, revealing that following DA depletion the proportion of iSPN mushroom spines significantly increased, in parallel with the increase in strEPSC amplitude. This was not true in dSPNs. Like the change in stEPSC amplitude, this shift in the distribution of spine shapes was blunted by antagonism of A2aRs. Thus, A2aR antagonism largely prevented or reversed depletion-induced alterations in the properties of corticostriatal synapses that remained on iSPNs.

A2aR antagonism also dampens cholinergic signaling

Although the most parsimonious interpretation of our results is that the primary site of A2aR antagonism is at iSPNs, cholinergic interneurons also express these receptors (Preston et al., 2000; Song et al., 2000; Tozzi et al., 2011). Striatal acetylcholine has profound effects on corticostriatal glutamatergic synaptic transmission, acting both at presynaptic M2-class and postsynaptic M1-class muscarinic receptors (Ding et al., 2010; Higley et al., 2009; Shen et al., 2005; Shen et al., 2007). Tozzi and colleagues (2011) have recently shown the importance of the reciprocity between D2Rs and A2aRs in controlling the firing rate of cholinergic interneurons. Their study also highlights the role of this reciprocity in regulating the activity of cholinergic interneurons in models of PD and the influence of cholinergic signaling on SPNs. Following DA depletion, cholinergic signaling has long been thought to rise (Pisani et al., 2007). Our results provided corroboration for this view, showing that in brain slices postsynaptic M1 muscarinic receptor tone was elevated, increasing dendritic excitability in iSPNs. 4-AP, at concentrations that antagonize Kv4 K+ channels, occluded this modulation, suggesting that M1 receptors were down-regulating Kv4 channel function (Hoffman and Johnston, 1998). This modulation in conjunction with the down-regulation of Kir2 K+ channels (Shen et al., 2007) should promote the dendritic depolarization necessary to open NMDARs involved in the induction of LTP. Previous work has implicated M1 receptors in enhancement of postsynaptic summation of corticostriatal glutamatergic EPSPs (Ding et al., 2010) and in the induction of corticostriatal LTP (Calabresi et al., 1999). Although postsynaptic M4 muscarinic receptors may play a role in these effects, these receptors are expressed at very low levels by iSPNs (Bernard et al., 1992; Yan and Surmeier, 1996), suggesting that M1 receptors are the principal mediators of the observed effects. Chronic A2aR antagonism prevented this elevation in cholinergic tone. As cholinergic interneurons also express D2Rs, it is possible that the loss of DA disinhibits A2aR signaling, leading to increased acetylcholine release (Kurokawa et al., 1996). A2aR signaling also could contribute to the upregulation of RGS4 expression in interneurons, which results in the attenuation of M4 autoreceptor function and enhanced cholinergic signaling in PD models (Ding et al., 2006).

A2aR antagonism did not prevent DA-depletion induced loss of spines

In contrast to the effects on synaptic plasticity, A2aR antagonism did not prevent the pruning of spines in iSPNs in the days following DA depletion (Day et al., 2006; Deutch et al., 2007; Ingham et al., 1993). This event appears to be a manifestation of homeostatic plasticity engaged in iSPNs by D2R-dependent disinhibition and increased spiking. Spiking is thought to open L-type channels that allow entry of Ca2+ linked to activation of the Ca2+-dependent protein phosphatase calcineurin and dephosphorylation of myocyte enhancer factor-2 (MEF2) (Tian et al., 2010); translocation of dephosphorylated MEF2 to the nucleus stimulates transcription of genes (e.g., Nur77, Arc) that promote spine elimination (Flavell et al., 2006; Shalizi et al., 2006). It is somewhat surprising that antagonism of A2aRs and the attenuated aberrant LTP did not have a significant effect on spine pruning in iSPNs, as normalizing synaptic strength should have diminished the homeostatic drive for pruning. Apparently, the elevation in intrinsic excitability produced by loss of D2R signaling, particularly the disinhibition of L-type Ca2+ channels (Olson et al., 2005), was more important to the homeostatic response than changes in synaptic strength.

In view of the unequivocal evidence for synaptic pruning in iSPNs following DA depletion, their increased responsiveness of to cortical stimulation might appear puzzling (Mallet et al., 2006). However, this adaptation is not difficult to understand in light of our results. In large measure, the increased responsiveness is attributable to 1) an elevation in postsynaptic excitability in iSPNs and 2) the A2aR-dependent potentiation of remaining corticostriatal synapses. These adaptations will complement the attenuation of recurrent collateral GABAergic signaling following DA-depletion (Taverna et al., 2008) in promoting evoked cortical responses. Our results also provide an explanation for why, when physiological salts are used to record mEPSPs/mEPSCs (which bias’ measurements toward large events), event frequency increases following sustained DA depletion (Calabresi et al., 1993).

Clinical implications for early stage PD

A2aR antagonists are currently being tested in clinical trials as an adjunct therapy in PD patients (Hauser and Schwarzschild, 2005; Jenner, 2003a; Morelli et al., 2007; Pinna et al., 2010). Our data provide a physiological rationale for this approach, complementing the biochemical one upon which it was originally proposed. The fact that A2aR antagonism appeared to work in part by normalizing cholinergic signaling following depletion suggests that muscarinic receptor antagonism, a common treatment in early stage PD (Pisani et al., 2007), should have minimal benefit as an adjunct therapy in patients being treated with A2aR antagonists. More importantly, the failure of A2aR antagonism to prevent spine loss shows that at therapeutically relevant doses, antagonists do not effectively normalize the excitability of iSPNs when DA depletion is near complete. This conclusion is consistent with the view that A2aR antagonists used as an adjunct to L-DOPA therapy in moderate-to-severe PD patients, although beneficial, might not be optimal (Pinna et al., 2010). A new clinical trial is underway that is testing the effectiveness of A2aR antagonist treatment in early stage PD patients (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01155479). Our data suggests that this might be a more effective intervention.

Research Highlights.

A2a receptor antagonist treatment in a Parkinson's disease (PD) model-

Attenuated PD related motor deficits.

Prevented aberrant strengthening of corticostriatal synapses.

Prevented aberrant alterations in spine morphology.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Reserpine treatment reduces cortical strEPSCs amplitude in dSPNs. (A) Sample traces of strEPSCs in dSPNs evoked by cortical stimulation in the presence of 2 mM Sr2+/0 Ca2+. (B) Box-plot summary showing a significant decrease in strEPSC amplitude at corticostriatal synapses of dSPNs of reserpinized mice as compared to control (control median=13.5; reserpine median=12, p<0.05, Mann-Whitney). (C) Box-plot summary of asynchronous release frequency (control median=26.2; reserpine median=22.4, p>0.05, Mann-Whitney). The asterisk indicates statistical significance (control n=11, reserpine n=14).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Karen Saporito and Sasha Ulrich for excellent technical assistance. Supported by (D.J.S.), Picower Foundation (D.J.S.), Dystonia Medical Research Foundation (J.D.P.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jayms D. Peterson, Email: j-peterson@northwestern.edu.

Joshua A. Goldberg, Email: joshua-goldberg@northwestern.edu.

References

- Albin RL, et al. The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:366–375. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballion B, et al. D2 receptor stimulation, but not D1, restores striatal equilibrium in a rat model of Parkinsonism. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;35:376–384. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard V, et al. Phenotypical characterization of the rat striatal neurons expressing muscarinic receptor genes. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1992;12:3591–3600. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-09-03591.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne JN, et al. Warmer preparation of hippocampal slices prevents synapse proliferation that might obscure LTP-related structural plasticity. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi P, et al. Activation of M1-like muscarinic receptors is required for the induction of corticostriatal LTP. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:323–326. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi P, et al. Electrophysiology of dopamine-denervated striatal neurons. Implications for Parkinson's disease. Brain : a journal of neurology. 1993;116(Pt 2):433–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canals M, et al. Homodimerization of adenosine A2A receptors: qualitative and quantitative assessment by fluorescence and bioluminescence energy transfer. J Neurochem. 2004;88:726–734. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day M, et al. Selective elimination of glutamatergic synapses on striatopallidal neurons in Parkinson disease models. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:251–259. doi: 10.1038/nn1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day M, et al. Differential excitability and modulation of striatal medium spiny neuron dendrites. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11603–11614. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1840-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutch AY, et al. Striatal plasticity and medium spiny neuron dendritic remodeling in parkinsonism. Parkinsonism & related disorders. 2007;13 Suppl 3:S251–S258. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(08)70012-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J, et al. RGS4-dependent attenuation of M4 autoreceptor function in striatal cholinergic interneurons following dopamine depletion. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:832–842. doi: 10.1038/nn1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J, et al. Corticostriatal and thalamostriatal synapses have distinctive properties. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6483–6492. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0435-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding JB, et al. Thalamic gating of corticostriatal signaling by cholinergic interneurons. Neuron. 2010;67:294–307. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flajolet M, et al. FGF acts as a co-transmitter through adenosine A(2A) receptor to regulate synaptic plasticity. Nature neuroscience. 2008;11:1402–1409. doi: 10.1038/nn.2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavell SW, et al. Activity-dependent regulation of MEF2 transcription factors suppresses excitatory synapse number. Science. 2006;311:1008–1012. doi: 10.1126/science.1122511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuxe K, et al. Adenosine A2A and dopamine D2 heteromeric receptor complexes and their function. Journal of molecular neuroscience : MN. 2005;26:209–220. doi: 10.1385/JMN:26:2-3:209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuxe K, et al. Adenosine receptor-dopamine receptor interactions in the basal ganglia and their relevance for brain function. Physiology & behavior. 2007;92:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR, Surmeier DJ. Modulation of striatal projection systems by dopamine. Annual review of neuroscience. 2011;34:441–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey CD, Svoboda K. Locally dynamic synaptic learning rules in pyramidal neuron dendrites. Nature. 2007;450:1195–1200. doi: 10.1038/nature06416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser RA, Schwarzschild MA. Adenosine A2A receptor antagonists for Parkinson's disease: rationale, therapeutic potential and clinical experience. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:471–482. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higley MJ, Sabatini BL. Competitive regulation of synaptic Ca2+ influx by D2 dopamine and A2A adenosine receptors. Nature neuroscience. 2010;13:958–966. doi: 10.1038/nn.2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higley MJ, et al. Cholinergic modulation of multivesicular release regulates striatal synaptic potency and integration. Nature neuroscience. 2009;12:1121–1128. doi: 10.1038/nn.2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DA, Johnston D. Downregulation of transient K+ channels in dendrites of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons by activation of PKA and PKC. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3521–3528. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03521.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingham CA, et al. Morphological changes in the rat neostriatum after unilateral 6-hydroxydopamine injections into the nigrostriatal pathway. Experimental brain research. Experimentelle Hirnforschung. Experimentation cerebrale. 1993;93:17–27. doi: 10.1007/BF00227776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner P. A2A antagonists as novel non-dopaminergic therapy for motor dysfunction in PD. Neurology. 2003a;61:S32–S38. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000095209.59347.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner P. Dopamine agonists, receptor selectivity and dyskinesia induction in Parkinson's disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003b;16 Suppl 1:S3–S7. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200312001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravitz AV, et al. Regulation of parkinsonian motor behaviours by optogenetic control of basal ganglia circuitry. Nature. 2010;466:622–626. doi: 10.1038/nature09159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitzer AC, Malenka RC. Endocannabinoid-mediated rescue of striatal LTD and motor deficits in Parkinson's disease models. Nature. 2007;445:643–647. doi: 10.1038/nature05506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa M, et al. Adenosine A2a receptor-mediated modulation of striatal acetylcholine release in vivo. J Neurochem. 1996;66:1882–1888. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66051882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC, Bear MF. LTP and LTD: an embarrassment of riches. Neuron. 2004;44:5–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet N, et al. Cortical inputs and GABA interneurons imbalance projection neurons in the striatum of parkinsonian rats. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3875–3884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4439-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki M, et al. Structural basis of long-term potentiation in single dendritic spines. Nature. 2004;429:761–766. doi: 10.1038/nature02617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedev NI, et al. The N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist CPP alters synapse and spine structure and impairs long-term potentiation and long-term depression induced morphological plasticity in dentate gyrus of the awake rat. Neuroscience. 2010;165:1170–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli M, et al. Role of adenosine A2A receptors in parkinsonian motor impairment and 1-DOPA-induced motor complications. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;83:293–309. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson PA, et al. G-protein-coupled receptor modulation of striatal CaV1.3 L-type Ca2+ channels is dependent on a Shank-binding domain. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25:1050–1062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3327-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna A, et al. A new ethyladenine antagonist of adenosine A(2A) receptors: behavioral and biochemical characterization as an antiparkinsonian drug. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:613–623. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani A, et al. Re-emergence of striatal cholinergic interneurons in movement disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston Z, et al. Adenosine receptor expression and function in rat striatal cholinergic interneurons. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:886–890. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmi P, et al. Adenosine-dopamine interactions revealed in knockout mice. Journal of molecular neuroscience: MN. 2005;26:239–244. doi: 10.1385/JMN:26:2-3:239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffmann SN, et al. A2A receptor and striatal cellular functions: regulation of gene expression, currents, and synaptic transmission. Neurology. 2003;61:S24–S29. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000095207.66853.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalizi A, et al. A calcium-regulated MEF2 sumoylation switch controls postsynaptic differentiation. Science. 2006;311:1012–1017. doi: 10.1126/science.1122513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, et al. Dichotomous dopaminergic control of striatal synaptic plasticity. Science. 2008;321:848–851. doi: 10.1126/science.1160575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, et al. Cholinergic suppression of KCNQ channel currents enhances excitability of striatal medium spiny neurons. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25:7449–7458. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1381-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, et al. Cholinergic modulation of Kir2 channels selectively elevates dendritic excitability in striatopallidal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1458–1466. doi: 10.1038/nn1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozaki S, et al. Actions of adenosine A2A receptor antagonist KW-6002 on drug-induced catalepsy and hypokinesia caused by reserpine or MPTP. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;147:90–95. doi: 10.1007/s002130051146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Y, et al. The thalamostriatal system: a highly specific network of the basal ganglia circuitry. Trends in neurosciences. 2004;27:520–527. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song WJ, et al. Adenosine receptor expression and modulation of Ca(2+) channels in rat striatal cholinergic interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:322–332. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.1.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmeier DJ, et al. Dopamine and synaptic plasticity in dorsal striatal circuits controlling action selection. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:621–628. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenningsson P, et al. Distribution, biochemistry and function of striatal adenosine A2A receptors. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;59:355–396. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taverna S, et al. Recurrent collateral connections of striatal medium spiny neurons are disrupted in models of Parkinson's disease. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28:5504–5512. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5493-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X, et al. MEF-2 regulates activity-dependent spine loss in striatopallidal medium spiny neurons. Molecular and cellular neurosciences. 2010;44:94–108. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozzi A, et al. The distinct role of medium spiny neurons and cholinergic interneurons in the D/AA receptor interaction in the striatum: implications for Parkinson's disease. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2011;31:1850–1862. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4082-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano G. Homeostatic signaling: the positive side of negative feedback. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, et al. Dopaminergic control of corticostriatal long-term synaptic depression in medium spiny neurons is mediated by cholinergic interneurons. Neuron. 2006;50:443–452. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu-Friedman MA, Regehr WG. Probing fundamental aspects of synaptic transmission with strontium. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2000;20:4414–4422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04414.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z, Surmeier DJ. Muscarinic (m2/m4) receptors reduce N- and P-type Ca2+ currents in rat neostriatal cholinergic interneurons through a fast, membrane-delimited, G-protein pathway. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1996;16:2592–2604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02592.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Reserpine treatment reduces cortical strEPSCs amplitude in dSPNs. (A) Sample traces of strEPSCs in dSPNs evoked by cortical stimulation in the presence of 2 mM Sr2+/0 Ca2+. (B) Box-plot summary showing a significant decrease in strEPSC amplitude at corticostriatal synapses of dSPNs of reserpinized mice as compared to control (control median=13.5; reserpine median=12, p<0.05, Mann-Whitney). (C) Box-plot summary of asynchronous release frequency (control median=26.2; reserpine median=22.4, p>0.05, Mann-Whitney). The asterisk indicates statistical significance (control n=11, reserpine n=14).