Abstract

Background

Charcot Marie Tooth disease (CMT) affects one in 2500 people. Genetic testing is often pursued for family planning purposes, natural history studies and for entry into clinical trials. However, identifying the genetic cause of CMT can be expensive and confusing to patients and physicians due to locus heterogeneity.

Methods

We analyzed data from more than 1000 of our patients to identify distinguishing features in various subtypes of CMT. Data from clinical phenotypes, neurophysiology, family history, and prevalence was combined to create algorithms that can be used to direct genetic testing for patients with CMT.

Findings

The largest group of patients in our clinic have slow motor nerve conduction velocities (MNCV) in the upper extremities. Approximately 88% of patients in this group have CMT1A. Those who had intermediate MNCV had primarily CMT1X (52.8%) or CMT1B (27.8%). Patients with very slow MNCV and delayed walking were very likely to have CMT1A (68%) or CMT1B (32%). No patients with CMT1B and very slow MNCV walked before 15 months of age. Patients with CMT2A form our largest group of patients with axonal forms of CMT.

Interpretation

Combining features of the phenotypic and physiology groups allowed us to identify patients who were highly likely to have specific subtypes of CMT. Based on these results, we created a series of algorithms to guide testing. A more detailed review of this data is published in Annals of Neurology (1).

Key words: CMT, Charcot Marie Tooth disease, genetic testing

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) is the eponym for inherited peripheral neuropathy (2, 3). It is a genetic heterogeneous condition with more than 30 causative genes and more than 44 loci identified (http://www.molgen.ua.ac.be/CMTMutations/Mutations/MutByGene.cfm). CMT is classified into subtypes based on the pattern of inheritance and the electrophysiology. Autosomal dominant (AD) demyelinating (CMT1), AD axonal (CMT2), autosomal recessive and X-linked (CMTX) forms of CMT exist. The large number of CMT causing genes is often challenging for clinicians and patients when trying to determine the underlying genetic diagnosis. There is little information available to guide which gene to test and testing a patient for mutations in all commercially available CMT genes is not cost effective. Nevertheless, family planning and prognosis often require an accurate genetic diagnosis and current treatment trials depend on knowing the genetic cause of a patient's CMT even if no cures are presently available.

Recently, a practice parameter guideline was published simultaneously in Neurology, Muscle and Nerve and PMR that also addressed the issue of genetic testing for CMT (4-6). The practice parameter guideline proposed an algorithm based on the prevalence of particular genetic types of CMT in the literature, whether MNCV were < 38 m/s, and whether or not there was a family history of neuropathy (4-6). The algorithm was an important advance in how to focus genetic testing for CMT. However, by incorporating phenotypic as well as more specific neurophysiologic data we now believe that we can further improve diagnostic yields of genetic testing for CMT. To assess this we analyzed data from 1024 of our patients to identify distinguishing clinical and physiological features of the subtypes that could be used to direct genetic testing for patients with CMT. We developed an algorithm based on clinical phenotypes, neurophysiology, family history data, and prevalence that we propose as a guide to help focus genetic testing for various forms of CMT.

To investigate whether combining phenotypic data with physiology further improved our ability to predict an accurate genetic diagnosis, patients were categorized into groups based on motor nerve conduction velocities and age of onset. Results were used to create algorithms for testing.

In terms of MNCVs affected patients were categorized into four groups: (1) those with normal MNCV (> 45 m/sec); (2) those with mild or "intermediate slowing (35 < and ≤ 45 m/sec); (3) those with slow MNCV (15 < and ≤ 35 m/sec) and those with very slow MNCV (≤ 15 m/sec). Patients with CMT clustered into three broad phenotypic groups based on age of onset. The first group we have characterized as the "classical phenotype", based on the descriptions of Harding and Thomas (7, 8). Affected patients with a classical phenotype begin walking on time, usually by a year to 15 months of age, and develop weakness or sensory loss during the first two decades of life. Impairment slowly increases thereafter, and rarely do patients require ambulation aids beyond ankle foot orthotics (AFOs) (9, 10). The second phenotype we define as infantile onset in which patients do not begin walking until they are at least 15 months of age. These patients are often severely affected and many required walkers or wheel-chairs for ambulation by 20 years of age. The third phenotype is defined as adult onset, in which patients do not develop symptoms of CMT until adulthood.

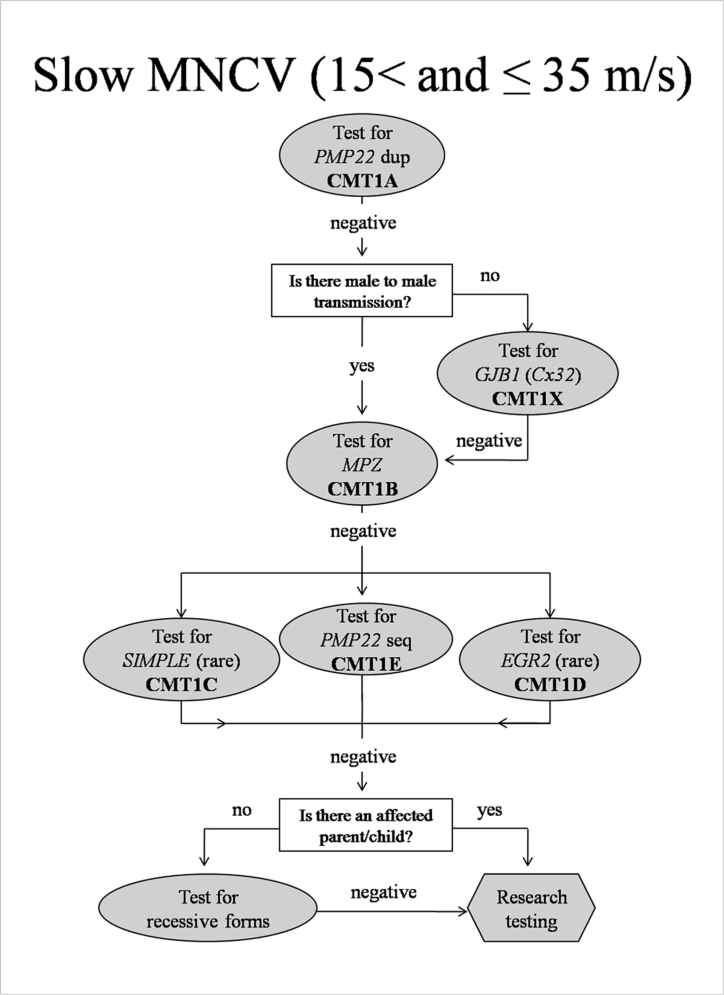

Slow MNCV (15-35 m/s) (Fig. 1)

Figure 1.

Algorithm to guide genetic testing for CMT in patients with slow ulnar motor nerve conduction velocities. This algorithm is designed to be a general guide and is not intended to encompass every potential clinical scenario nor all possible genetic etiologies. Dup= duplication; Seq=sequencing.

The largest group of patients in our clinic began have slow MNCV in the upper extremities between 15 and 35 m/s. Approximately 88% of this group will have CMT1A and we propose to initially test ONLY for the CMT1A causing duplication in these patients. Screening for CMT1A should commence irrespective of whether there is a positive family history, as approximately 10% of CMT1A cases present with apparently de novo mutations (11). Additional testing will be pursued only if the patient does not have CMT1A. In this event, we propose first ascertaining whether there is a family history of male-to-male transmission (father and son affected), since CMT1X is the next most common form of CMT in this group based on results from our clinic. Only if this testing is negative or if there is male-to-male transmission in the pedigree should testing proceed for an unusual presentation of CMT1B, then CMT1E or other cause of dominantly inherited demyelinating neuropathy. In the absence of consanguinity, it is predicted that recessive forms of CMT will occur in at most 10% of our patients (12). Therefore we propose to only test for AR forms when the family history clearly suggests this inheritance pattern (multiple affected siblings with no parent, child, or other family members affected) or when the dominant forms of demyelinating neuropathies have been excluded. In the rare cases with a clear AD family history, we suggest next undertaking research testing to identify novel CMT causing genes.

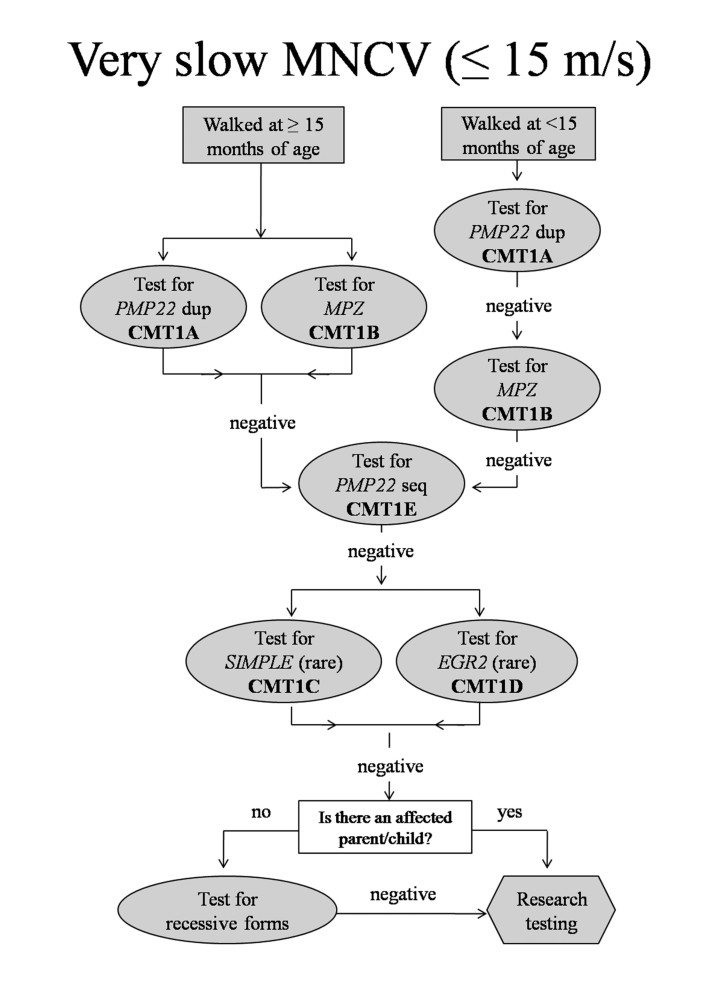

Severely slow MNCV ( ≤ 15 m/s) (Fig. 2)

Figure 2.

Algorithm to guide genetic testing for CMT in patients with very slow ulnar motor nerve conduction velocities. This algorithm is designed to be a general guide and is not intended to encompass every potential clinical scenario nor all possible genetic etiologies. Dup= duplication; Seq=sequencing.

For those with severely slow MNCV ( ≤ 15 m/s) genetic testing should be guided by the age of onset. Many patients in this group did not begin walking independently until after 15 months of age. These patients were very likely to have CMT1A (68%) or CMT1B (32%). Accordingly, we propose to begin testing for the PMP22 duplication or mutations in the MPZ gene for all patients in this category.

For patients with very slow MNCV ( ≤ 15 m/s) who began walking before 15 months we propose to begin testing for only CMT1A. None of our patients with CMT1B and MNCV ≤ 15 m/s walked before 15 months of age. If this testing is negative, the next most common cause of CMT in our clinic population of patients with very slow MNCV is CMT1B. Because AD neuropathy is much more frequent than AR neuropathy in our clinic population, we again propose continuing with AD disorders, even if there is no obvious family history of CMT. If there is no PMP22 duplication and if MPZ sequencing is normal we suggest sequencing PMP22 (CMT1E), a less frequent cause of this presentation. Only if these tests are negative should testing proceed to CMT1C and CMT1D, very rare forms of CMT1 in our patient group. If testing for these is also negative, the presence or absence of an affected parent or child can be used to determine whether to next test for AR disorders or whether research testing for novel genes is more appropriate.

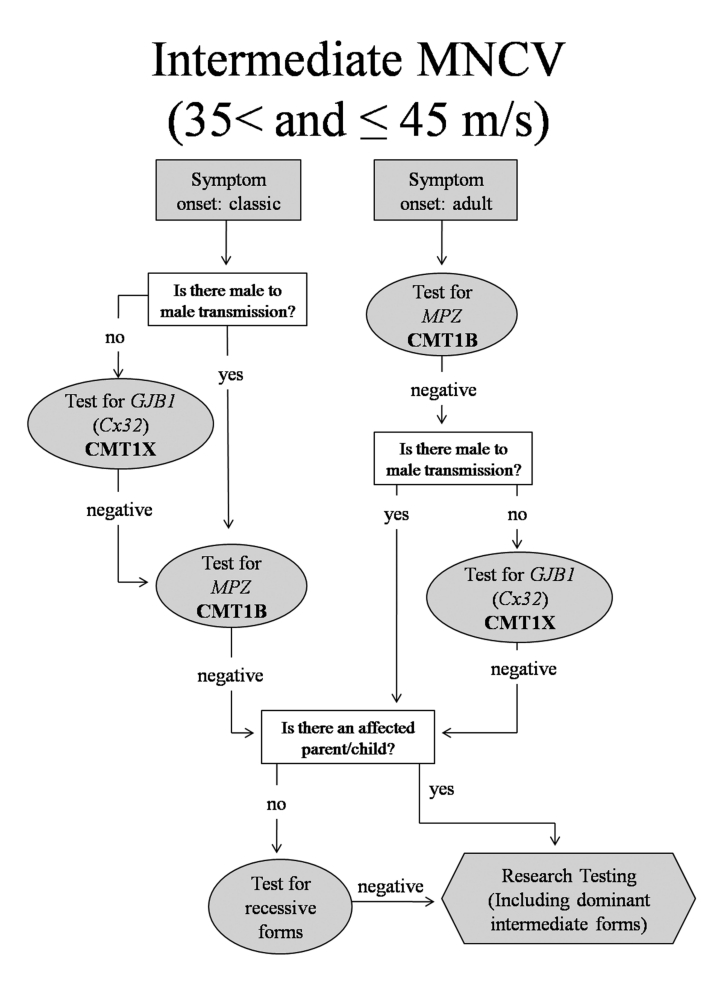

CMT with Intermediate MNCV (35-45 m/s) (Fig. 3)

Figure 3.

Algorithm to guide genetic testing for CMT in patients with intermediate ulnar motor nerve conduction velocities. This algorithm is designed to be a general guide and is not intended to encompass every potential clinical scenario nor all possible genetic etiologies.

Patients with identified genetic causes of CMT who had intermediate MNCV (35-45 m/s) had primarily CMT1X (52.8%) or CMT1B (27.8%). For patients with intermediate MNCV, the first step is to determine whether the phenotype is classical or adult onset and then whether there is evidence of male-to-male transmission. For patients with intermediate conductions and a classical phenotype, the first test should be for GJB1 mutations (CMT1X) (78%). It is important to note that testing for X-linked forms of CMT should only be pursued in the absence of male-to-male transmission. If this testing is negative, testing should proceed to MPZ mutations. Alternatively, if there is male-to-male transmission, testing for CMT1B should occur first since the inheritance pattern would formally exclude CMT1X.

If patients with intermediate MNCV first develop symptoms in adulthood, testing should begin with CMT1B, as this is most likely according to our results. As no patients with CMT1A had intermediate conduction velocities, testing for a PMP22 duplication would not be warranted. If all testing is negative, the presence or absence of an affected parent or child can be used to determine whether to next test for rare or AR disorders or whether research testing for novel genes is more appropriate. Some rare genes for the dominant intermediate forms of CMT include DNM2 (DI-CMTB) and YARS (DI-CMTC) mutations. These are not included on the flow diagram because there are no genetically confirmed cases of these in our clinic. However, it is possible that they will make up a clinically significant part of the CMT population in the future, and these flow charts can be altered to reflect that. Patients with HNPP were identified in the intermediate NCV group with childhood and adult onset of symptoms. This disorder was not included in Figure 3 (or Fig. 4) because of its characteristic presentation of focal episodes of weakness or sensory loss and focal slowing of MNCV that distinguish it from other forms of CMT. These clinical and physiological findings should, by themselves, suggest testing for HNPP (13, 14).

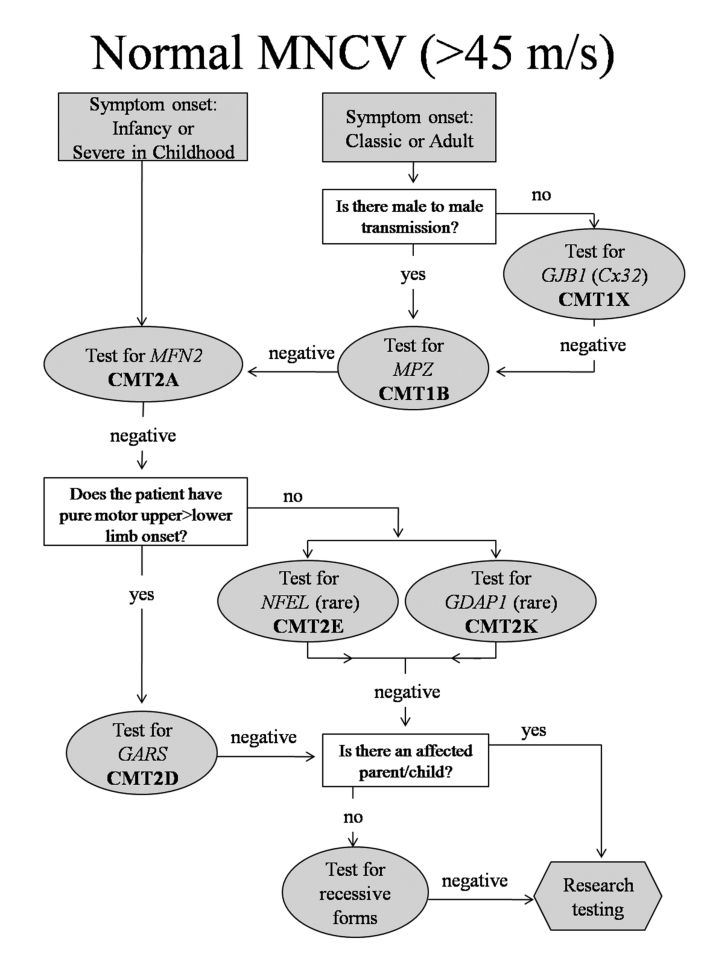

Figure 4.

Algorithm to guide genetic testing for CMT in patients with normal ulnar motor nerve conduction velocities. This algorithm is designed to be a general guide and is not intended to encompass every potential clinical scenario nor all possible genetic etiologies.

Targeted testing for normal or unobtainable NCV (Fig. 4)

Patients with CMT2A were frequently severely affected in infancy and childhood to the extent that their CMAP amplitudes and NCV were unobtainable by testing in the upper extremities, Since patients with CMT2A form our largest group of patients with CMT2 (Feely, submitted) we propose to test patients with severe axonal neuropathies in childhood initially for mutations in MFN2, the cause of CMT2A. The other two common forms of CMT that presented with normal MNCV in the arms were CMT1X (particularly women), and CMT1B. Testing for CMT1B and CMT1X would be reasonable for late onset patients with normal MNCV unless there was male-to-male transmission in the pedigree, in which case only CMT1B is appropriate. Testing for all other forms of CMT2 would be far less likely to be successful and would be reserved for those patients who were negative for CMT2A, CMT1X and CMT1B. In our clinic, we have four patients with mutations in NEFL causing CMT2E, five patients with a single (identical) mutation in GDAP1 causing CMT2K, and three patients with mutations in GARS causing CMT2D. Other potential causes of CMT2 including mutations in HSP22 (CMT2L) or HSP27 (CMT2F) might then be considered. Patients with RAB7 (CMT2B) and SPTLC1 (HSN1) mutations have predominantly sensory phenotypes, and patients with GARS (CMT2D) or BSCL2 (Silver syndrome) mutations often have relatively pure motor syndromes. Moreover, patients with CMT2D often note hand impairment prior to leg impairment that is unusual for patients with CMT. Thus in CMT2 we propose to use these specific phenotypes to direct additional genetic testing after initial negative testing. It may be necessary to perform nerve conductions on proximal nerves if CMAP and SNAP potentials are unobtainable distally.

Before pursuing genetic testing we feel it is important to consider that not every patient with a genetic neuropathy wants or needs genetic testing (15). We believe that the ultimate decision to undergo genetic testing rests with the patient or the patient's parents if a symptomatic child is under 18 years of age. Reasons that patients give for obtaining testing include identifying the inheritance pattern of their CMT, making family planning decisions, and obtaining knowledge about the cause and natural history of their form of CMT. Natural history data is available for some forms of CMT such as CMT1A (10) and CMT1X (16), which can provide guidance for prognosis, recognizing that there can be phenotypic variability in these subtypes. Patients with other forms of CMT frequently choose to undergo genetic testing to contribute to the natural history data collection for other patients with the same subtype. There are also reasons why patients do not want genetic testing. These include the high costs of commercial testing and fears of discrimination in the workplace or in obtaining health insurance. Since there are currently no medications to reverse any form of CMT, many patients decide against testing since their therapies will not depend on the results. We maintain that it is always the patient's decision whether or not to pursue genetic testing.

Once a genetic diagnosis has been made in a patient, other family members usually do not need genetic testing and can be diagnosed by clinical evaluation with neurophysiology. We do not typically test patients for multiple genetic causes of CMT simultaneously. It is our current policy to only consider genetic testing clinically affected family members if their phenotype is atypical for the type of CMT in the family. In addition, we do not test asymptomatic minors with a family history of CMT, either by electrophysiology or genetic testing, due to the chance for increased psychological harm to the child (17). We do routinely perform limited nerve conduction studies, though not needle EMG, on symptomatic children with CMT. Since nerve conduction changes, including slowing, are often uniform and detectable in early childhood in CMT (18), testing of a single nerve is often adequate to guide genetic testing or determine whether a symptomatic child is affected in a family with CMT.

In summary, patients with inherited neuropathies can serve as models of their own disease if their phenotypes are carefully analyzed and their genotypes characterized. Molecular mechanisms of demyelination, axonal loss and axo-glial interactions can thus be investigated and rational therapies can be developed, not only for CMT but for related neurodegenerative disorders. However genotyping of families is essential for this approach, is confusing to patients and physicians and is very expensive to undertake commercially or in research laboratories. We have developed what we believe is a focused approach to testing based on phenotype, physiology and prevalence that we hope will prove useful in our clinic and to others who care for patients with inherited neuropathies.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Muscular Dystrophy Association, the National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and Office of Rare Diseases (U54NS065712) and the Charcot Marie Tooth Association. The authors deeply appreciate the patients and families that participated in this study.

Ethics Committee Approval

This study has received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Wayne State University.

Footnotes

Dr. Shy is on the Speakers Bureau of Athena Diagnostic Laboratories. There are no other disclosures for any author. Dr. Shy, the corresponding author, has full access to the data used in this study and has final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

References

- 1.Saporta ASD, Sottile SL, Miller LJ, et al. Charcot Marie Tooth (CMT) subtypes and genetic testing strategies. Annals of Neurology. 2011;69:22–33. doi: 10.1002/ana.22166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charcot J, Marie P. Sur une forme particulaire d'atrophie musculaire progressive souvent familial debutant par les pieds et les jamber et atteingnant plus tard les mains. Re Med. 1886;6:97–138. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tooth H. The peroneal type of progressive muscular atrophy. London: Lewis; 1886. [Google Scholar]

- 4.England JD, Gronseth GS, Franklin G, et al. Evaluation of distal symmetric polyneuropathy: the role of laboratory and genetic testing (an evidence-based review) Muscle Nerve. 2009;39:116–125. doi: 10.1002/mus.21226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.England JD, Gronseth GS, Franklin G, et al. Practice Parameter: evaluation of distal symmetric polyneuropathy: role of laboratory and genetic testing (an evidence-based review). Report of the American Academy of Neurology, American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Neurology. 2009;72:185–192. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000336370.51010.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.England JD, Gronseth GS, Franklin G, et al. Practice parameter: the evaluation of distal symmetric polyneuropathy: the role of laboratory and genetic testing (an evidence-based review) PM R. 2009;1:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harding AE, Thomas PK. The clinical features of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy types I and II. Brain. 1980;103:259–280. doi: 10.1093/brain/103.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shy M, Lupski JR, Chance PF, et al. The Hereditary Motor and Sensory Neuropathies: an overview of the clinical, genetic, electrophysiologic and pathlogic features. In: Dyck PJ TP, editor. Peripheral Neuropathy. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2005. pp. 1623–1658. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krajewski KM, Lewis RA, Fuerst DR, et al. Neurological dysfunction and axonal degeneration in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 7):1516–1527. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.7.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shy ME, Chen L, Swan ER, et al. Neuropathy progression in Charcot- Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. Neurology. 2008;70:378–383. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000297553.36441.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelis E, Broeckhoven C, Jonghe P, et al. Estimation of the mutation frequencies in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1 and hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies: a European collaborative study. Eur J Hum Genet. 1996;4:25–33. doi: 10.1159/000472166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubourg O, Azzedine H, Verny C, et al. Autosomal-recessive forms of demyelinating Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neuromolecular Med. 2006;8:75–86. doi: 10.1385/nmm:8:1-2:75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Krajewski K, Lewis RA, et al. Loss-of-function phenotype of hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies. Muscle Nerve. 2004;29:205–210. doi: 10.1002/mus.10521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J, Krajewski K, Shy ME, et al. Hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsy: the electrophysiology fits the name. Neurology. 2002;58:1769–1773. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.12.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krajewski KM, Shy ME. Genetic testing in neuromuscular disease. Neurol Clin. 2004;22:481–508. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2004.03.003. v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shy ME, Siskind C, Swan ER, et al. CMT1X phenotypes represent loss of GJB1 gene function. Neurology. 2007;68:849–855. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256709.08271.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Society of Human Genetics Board of Directors, Directors, ACoMGBo, authors. ASHG/ACMG REPORT Points to Consider: Ethical, Legal, and Psychosocial Implications of Genetic Testing in Children and Adolescents. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:1233–1241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis RA, Sumner AJ, Shy ME. Electrophysiological features of inherited demyelinating neuropathies: a reappraisal in the era of molecular diagnosis. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:1472–1487. doi: 10.1002/1097-4598(200010)23:10<1472::aid-mus3>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]