Abstract

Objective

Develop a clinically relevant model of pediatric asphyxial cardiopulmonary arrest in rats.

Design

Prospective interventional study.

Setting

University research laboratory.

Subjects

Post-natal day (PND) 16-18 rats.

Interventions

Anesthetized rats were endotracheally intubated and mechanically ventilated, and vascular catheters were inserted. Vecuronium was administered and the ventilator was disconnected from the rats for 8 min, whereupon rats were resuscitated with epinephrine, sodium bicarbonate, and chest compressions until spontaneous circulation returned. Shams underwent all procedures except asphyxia.

Measurements and Main Results

Asphyxial arrest typically occurred by 1 min after the ventilator was disconnected. Return of spontaneous circulation typically occurred <30 sec after resuscitation. An isoelectric electroencephalograph was observed for 30 min after asphyxia and rats remained comatose for 12-24 h. Survival rate in rats after asphyxia was 75%. Motor function measured using beam balance and inclined plane tests was impaired on d 1 and 2, but recovered by d 3, in rats after asphyxia vs. sham injury (n=9/group; P<0.05). Spatial memory acquisition measured using the Morris-water maze on d 7–14 and 28–35 was also impaired in rats after asphyxia vs. sham injury (total latency 379±28 vs. 501±40 sec, respectfully; n=9/group; P<0.05). CA1 hippocampal neuron survival after asphyxia was 39-43% (n=9/group; P<0.001 vs. sham). DNA fragmentation was detected in CA1 hippocampal neurons bilaterally in separate rats on d 3-7 after asphyxia (n=3-4/group). Neurodegeneration detected using Fluorojade-B was seen in bilateral CA1 hippocampi and layer III cortical neurons 3-7 d after asphyxia, with persistent neurodegeneration in CA1 hippocampus detected up to 5 wks after asphyxia. Evidence of DNA or cellular injury was not detected in sham rats.

Conclusions

This model of asphyxial cardiopulmonary arrest in PND 17 rats produces many of the clinical manifestations of pediatric hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. This model may be useful for the pre-clinical testing of novel and currently available interventions aimed at improving neurological outcome in infants and children after cardiopulmonary arrest.

Keywords: Brain injury, Cardiac arrest, Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, Development, Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, Neurodegeneration

Introduction

Cardiopulmonary arrest in infants and children remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality (1). In the United States, it is estimated that 16,000 children die annually of unexpected cardiopulmonary arrest. A recent review summarizing the results from 44 studies totaling 3,094 pediatric patients after cardiopulmonary arrest (1) showed an overall survival after cardiopulmonary arrest of 13% (24% for in-hospital arrest, 9% for out-of-hospital arrest), with unfavorable neurologic outcome in approximately 50% of the survivors where outcome was reported. In addition to physical debilitation in pediatric survivors of cardiopulmonary arrest and the emotional burden to family, there are also significant monetary and psychosocial burdens (2). The lifelong cost for continued care of a moderately to severely disabled child can easily exceed $1 million (3). Boys and girls suffering cardiorespiratory arrest are essentially equally represented (50-60% male), and many patients are < 1 year-of-age (1, 4). Less than 10% of patients were found to have ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation, most had asystole, bradycardia, or pulseless electrical activity and were a consequence of asphyxia (1). Both out-of-hospital and in-patient cardiopulmonary arrests in pediatric patients are predominantly associated with asystole, rather than ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation, in contrast to adult patients (5).

The principle factor that influences outcome in survivors of cardiopulmonary arrest is the neurologic sequelae resulting from hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) (6). Unfortunately, there are no interventions to reverse the cellular consequences of HIE (7). Recent clinical trials in adult patients suggest that some degree of HIE can be prevented if therapies are initiated early after cardiac arrest (8, 9). However, whereas a cardiac etiology is the principle cause of cardiopulmonary arrest in adults, asphyxia is the principle cause of cardiopulmonary arrest in infants and children, resulting in systemic hypoxemia, hypercapnea, acidosis and ultimately hypotension and bradycardia culminating in complete cardiovascular collapse (1). To date, there is no contemporary age-appropriate pediatric model of HIE for the evaluation of prolonged neurodegeneration and long-term neurologic outcome. Some insight into developmental aspects of HIE can be extrapolated from the well-established model of carotid artery ligation followed by hypoxemia in immature rodents (10), or asphyxial arrest in piglets (11, 12); however, these models either do not model global and systemic hypoxemia/ischemia or are impractical in terms of long-term outcome assessment, respectively. To address these limitations, we have developed a model of pediatric asphyxial cardiac arrest in post-natal day (PND) 17 rats that has the capacity for 1) invasive physiologic monitoring and acute resuscitation that closely mimics guidelines used in humans; 2) acute and long-term biochemical and cellular assessment utilizing currently available molecular tools tested in rodents; 3) acute and long-term functional outcome assessment utilizing standardized behavioral tools developed for use in rodents with the potential for application of rehabilitation strategies; and 4) testing of potential clinically relevant therapies and their related mechanisms.

Material and Methods

Experimental Procedure

Studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pittsburgh. An established asphyxial cardiac arrest model in adult rats (13-16) was modified for use in pediatric-aged rats. Mixed-litter, mixed-gender PND 16-18 Sprague-Dawley rats (35-40 g) were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane/50% N2O/ balance O2 in a plexiglass chamber until unconscious, then intubated with an 18-gauge angiocatheter, and mechanically ventilated with 1% isoflurane/50% N2O/balance O2 for surgery. Typical ventilatory rates were 45-75 breaths/min with tidal volumes ∼0.6 ml for PND 16 - 18 rats. All procedures were performed using aseptic technique. Femoral arterial and venous catheters (PE 10) were inserted. Mean arterial blood pressure was monitored continuously. Vecuronium (1 mg/kg/h, i.v.) was used for immobilization and was administered 10 min before asphyxia. FiO2 was reduced to 0.21 (room air) for 1 min prior to asphyxia to avoid hyper-oxygenation pre-insult. At 2 min prior to asphyxia isofluorane/N2O was discontinued. This anesthetic washout was performed to reduce the confounding effects of inhaled anesthetics (17). Previous pilot experiments testing the anesthetic regimen in uninjured PND 16 - 18 rats monitored with scalp electrodes showed that EEG activity began to recover in frequency and amplitude by 2 min, just as animals were emerging from general anesthesia. After the anesthetic washout the ventilator was turned off for 8 min, then restarted using an FiO2 = 1.0. Epinephrine 0.005 mg/kg and sodium bicarbonate 1 mEq/kg were administered intravenously, followed by rapid manual chest compressions until return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC). Rats received 10 ml/kg D10W .45 NS subcutaneously at 60 min. Vascular catheters were removed, and the rats were weaned from mechanical ventilation and extubated. Muscle relaxation was not reversed; however, by 60 min adequate spontaneous respiratory effort was observed (see Table 1). Rats were observed in FiO2 = 1.0 for 1 h, then returned to their mothers. Shams underwent all procedures except asphyxia and resuscitation.

Table 1. Physiologic variables.

| Sham (n = 9) | Asphyxia (n = 9) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Baseline | ROSC 10 min | ROSC 30 min | ROSC 60 min | |

| Temperature (°C) | 37.2 ± 0.1 | 37.3 ± 0.1 | 37.0 ± 0.1 | 37.2 ± 0.1 | 37.2 ± 0.1 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 367 ± 9 | 357 ± 8 | 352 ± 12 | 371 ± 7 | 356 ± 6 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 58.9 ± 3.0 | 59.4 ± 2.9 | 58.1 ± 5.0 | 46.1 ± 2.0* | 51.1 ± 2.7 |

| pH | 7.34 ± 0.01 | 7.32 ± 0.01 | 7.30 ± 0.02 | 7.36 ± 0.01 | 7.36 ± 0.01 |

| PaCO2 | 39.44 ± 1.26 | 39.56 ± 1.13 | 37.44 ± 1.43 | 41.89 ± 0.90 | 42.63 ± 0.82 |

| PaO2 | 260.3 ± 6.8 | 252.0 ± 11.5 | 424.1 ± 20.5* | 416.4 ± 18.2* | 429.9 ± 16.5* |

| HCO3 | 21.09 ± 0.46 | 21.36 ± 0.55 | 18.36 ± 0.75* | 23.14 ± 0.42 | 23.58 ± 0.38* |

| Base excess | -3.64 ± 0.55 | -3.63 ± 0.69 | -7.3 ± 0.75* | -1.22 ± 0.44* | -0.60 ± 0.48* |

Mean ± SEM,

P < 0.05 vs. baseline

Functional Outcome Assessment

Gross vestibulomotor function was assessed in each rat by an observer blinded to experimental group using the beam balance and inclined plane tests (18) on days 1 – 5 after asphyxia or sham injury. For the beam balance task, each rat was placed on a suspended, narrow wooden beam (1.5 cm wide) and the latency that the rat remained on the beam was measured up to a maximum of 60 sec. For the inclined plane task, each rat was placed on a flat board at an initial angle of 45°. The angle of the plane was then increased in 5° increments to a maximum of 80°. The angle at which the rat could maintain its position on the board for 10 sec was recorded.

Spatial memory acquisition was assessed in each rat by an observer blinded to experimental group using the Morris water maze (19) on days 7 – 14 and 28 – 35 after asphyxia or sham injury. The Morris water maze employs a 180 cm diameter and 60 cm high metal pool filled with water to a depth of 28 cm and kept at 20-22°C. A platform 10 cm in diameter and 26 cm high (i.e. 2 cm below the water's surface) is used as the hidden goal platform in a room with constant extra-maze cues. A video tracking system (Polytrack) was used to record and quantify the swimming motions of the rats. The hidden platform was used to assess the rat's ability to learn spatial relations between distal cues and the escape platform. On each of 4 daily acquisition trials, the rat was placed in the pool facing the wall starting from 4 possible randomized start locations. Rats were given up to 120 sec to find the hidden platform. If the rat failed to find the platform after 120 sec, it was placed on the platform and allowed to remain on the platform for 30 sec before being placed in a heated incubator between trials (4-min inter-trial interval). A single probe trial was performed in which the platform is removed and the percent time spent in the platform quadrant is measured by the video tracking system. A visible platform task was performed on the last 2 days of each weekly trial where the platform is raised 2 cm above the surface of the water. The visible platform task examined for potential deficits in visual and motor function.

Histological Assessment

Separate rats at 3 and 7 d after asphyxia or sham injury (3-4/group), and all rats used for the functional outcome studies at 35 d after asphyxia or sham injury, were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane/50% N2O/ balance O2 as described above, then transcardially perfused with 250 mL ice-cold heparinized saline followed by 250 mL 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed and further post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Paraffin embedded brains were then blocked and cut into 5 μm coronal sections. Gross ischemic cellular changes were evaluated in hemotoxolyn and eosin (H&E) stained sections. In rats at 35 d after asphyxia or sham injury, viable neurons within the dorsal CA1 region of the hippocampus were counted by an observer blinded to experimental condition (C. D. M.).

FluoroJade B staining of tissue sections was used to identify degenerating neurons (20). Briefly, 5 μm coronal brain sections were deparaffinized in a series of xylenes, immersed twice in 100% ethanol (EtOH) and 1% sodium hydroxide (in 80% EtOH) for 90 sec, then 70% EtOH for 30 sec. Slides were then placed on a shaker in 0.06% potassium permangante for 10 min and washed in distilled water before immersion in a 0.006% working solution of Fluoro-Jade B with DAPI for 30 min. After a series of distilled water washes, slides were drained and placed on a slide warmer at 50°C for 10 min, then cover-slipped with DPX mounting medium.

DNA damage was assessed using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated biotin-dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) as previously described (21). Briefly, deparaffinized sections were incubated in Proteinase K (Boeringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN), then incubated in 300 U/ml terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase and 20 nmol/ml biotin-16-dUTP (Boeringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) at 37°C for 90 min. Sections were then incubated in avidin-biotin complex (ABC standard kit, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA), and TUNEL visualized with diaminobenzidine (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA).

Data Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Between group differences in baseline physiologic variables and neuronal cell counts were determined using a t-test. Within group differences in physiologic variables were determined using repeated measures ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc test. Between and within group differences in body weights and functional outcome tests were determined using two-way repeated measures ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc test. Fluorojade-B and TUNEL were qualitatively assessed.

Results

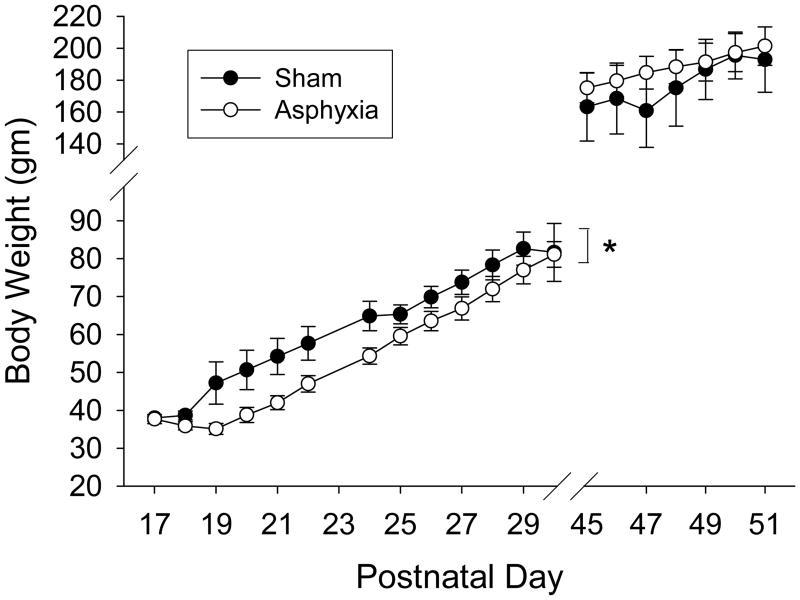

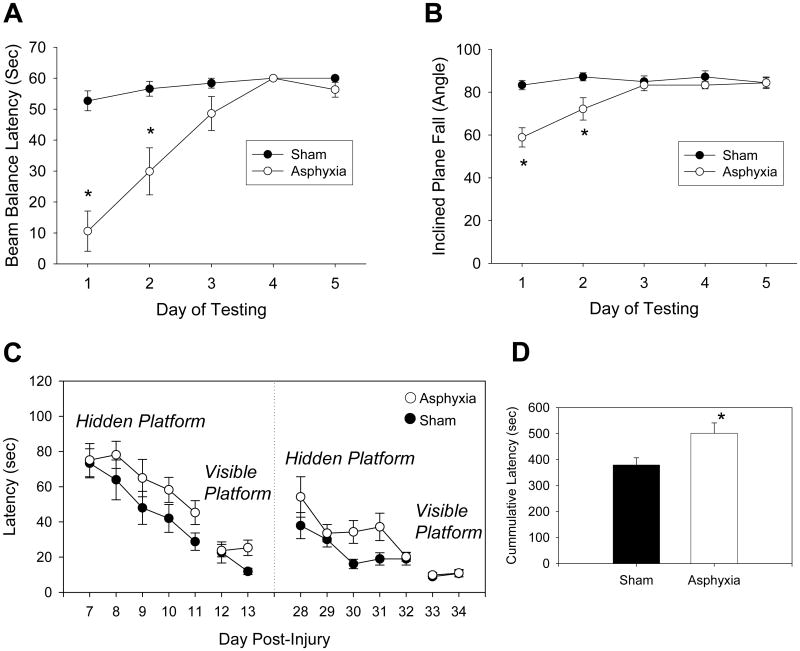

Eight min of asphyxia in PND 16-18 rats was chosen based on pilot studies and previous experience with the model in adult rats (14-16). A 2 min anesthetic washout period was used to reduce the potential confounding effects of general anesthesia (17). At the end of the anesthetic washout, burst suppression was seen on EEG, at which point the ventilator was turned off (Fig. 1). Loss of spontaneous circulation (MAP < 10 mmHg without pulsation) occurred after approximately 1 min of asphyxia. Return of spontaneous circulation after resuscitation was achieved in all rats and typically occurred in < 30 sec. Baseline and post-ROSC physiologic variables are shown in Table 1. Transient hypotension and metabolic acidosis were seen after asphyxia (P < 0.05; vs. baseline). Isoelectricity was seen initially on EEG with a burst suppression pattern at 60 min. After cardiopulmonary arrest, rats were in flaccid coma, but were spontaneously breathing and all were successfully weaned from mechanical ventilation. By 24 h rats were generally ambulatory, had returned to the litter, and were feeding. Survival rate for rats after asphyxia was 75% (9/12), with deaths occurring between 1 and 24 h. Weight gain was delayed by 3 – 4 d in rats after asphyxia compared with sham rats, but by postnatal d 30 (post-asphyxia d 14) body weights were similar between groups (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

EKG, BP, and EEG monitoring in a typical PND 17 rat after 8 min asphyxial cardiac arrest. Partial recovery of EEG is seen after a 2 min anesthetic washout. Return of spontaneous circulation occurs here at 22 sec post-resuscitation. Note that the monitor speed was changed at several positions in the tracing.

Fig. 2.

Body weight comparison between sham and asphyxiated rats recorded on PNDs 17 - 30 and 45 - 51. *P < 0.05 sham vs. asphyxia.

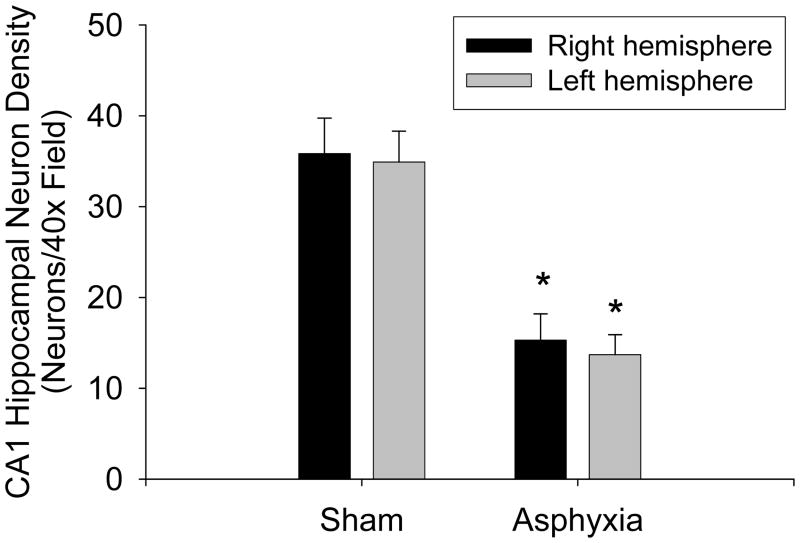

Profound motor function deficits were seen acutely after asphyxia compared with sham rats. The latency for rats to stay on the beam balance apparatus was reduced on d 1 and 2 in asphyxia compared with sham rats (P < 0.05; Fig. 3A). Similarly, the angle necessary for rats to fall from the inclined platform was reduced on d 1 and 2 in asphyxia compared with sham rats (P < 0.05; Fig. 3B). As is typical of rodents after brain injury, performance on the motor tasks recovered by d 3. Weakness of the hind limb ipsilateral to catheter placement was seen up to 5 d after surgery in both sham rats and rats after asphyxia, therefore, motor deficits detected using the beam balance and inclined plane likely reflect CNS rather than musculoskeletal dysfunction. Disturbances in spatial memory acquisition as assessed using the Morris-water maze were also detected at 1 and 4 wks after asphyxia (Fig. 3C). Latency to find the hidden platform was longer in rats after asphyxia vs. shams when tested on d 7-11 (P = 0.046) and 28-32 (P = 0.041) after asphyxia or sham-injury. The cumulative latencies for all days of hidden platform testing were also increased in asphyxia vs. sham rats (P < 0.05; Fig. 3D). Probe trials examining time spent in the target quadrant were not different between groups (data not shown). Swim speeds were not different between groups indicating that increased latency to find the hidden platform was not due to inter-group differences in motor performance in the maze (data not shown). Similarly, rats in both groups quickly found the visible platform, indicating that differences between groups in performance in the water maze did not result from differences in visual acuity.

Fig. 3.

Functional deficits seen in PND 16 - 18 rats after 8 min asphyxial cardiac arrest. Profound motor deficits are seen in A. beam balance latency and B. inclined plane fall angle on d 1 and 2 vs. sham. C. Modest deficits in the latency to find the hidden platform in the Morris-water maze are seen on d 7-11 and 28-32, intergroup differences were detected (P < 0.05 sham vs. asphyxia). D. Cumulative latencies for all days of hidden platform testing. Mean ± SEM, n = 9/group, *P < 0.05 vs. sham.

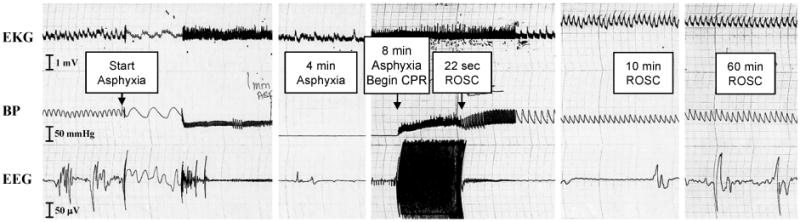

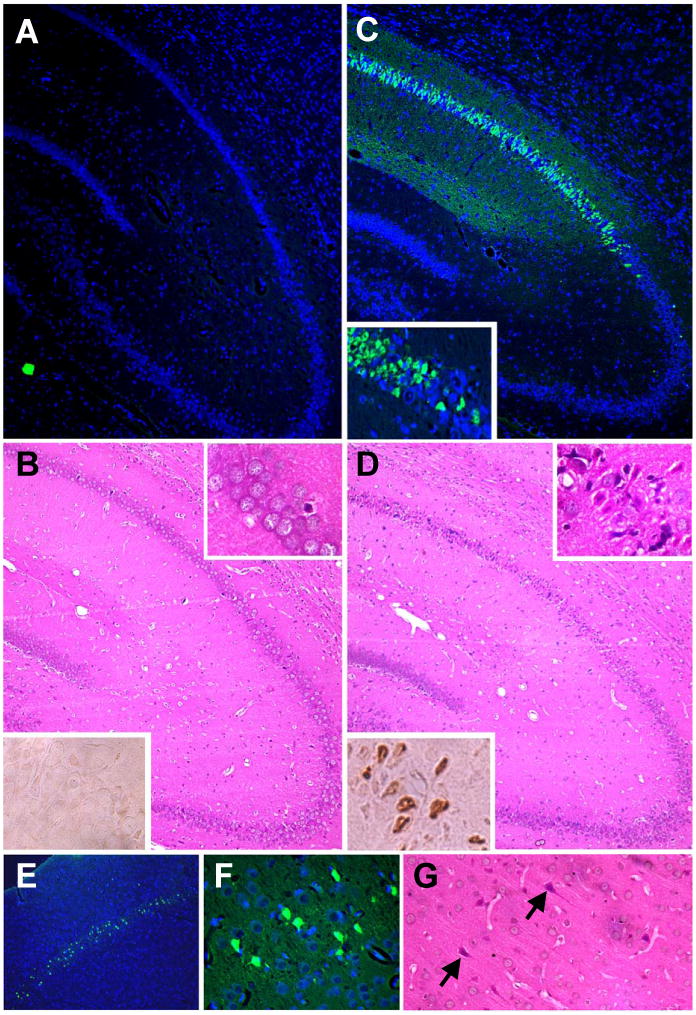

Eight min of asphyxial cardiopulmonary arrest produced selective cortical and CA1 hippocampal neuronal cell degeneration with DNA fragmentation. At 3-7 d after asphyxia (but not sham injury), shrunken, eosinophilic neurons that were TUNEL-positive were seen in the CA1 region of the hippocampus bilaterally (Fig. 4). Similar numbers of CA1 hippocampal neurons were identified with Fluorojade-B. Fluorojade-B labeling was seen in the cell bodies as well as apical and basal dendritic layers of CA1, suggesting complete degeneration of CA1 neurons. Both ischemic neuronal changes detected using H&E staining and Fluorjade B labeling in the CA1 sector were evident out to 5 wks after asphyxia. At 5 wk after asphyxia, CA1 neuron density was 39 – 43% of sham values (Fig. 5; P < 0.001). Right dorsal CA1 neuron density was 15.3±2.9 vs. 35.8±3.9 neurons/40× field in asphyxia vs. sham, respectively. Left dorsal CA1 neuron density was 13.7±2.2 vs. 34.9±3.4 neurons/40× field in asphyxia vs. sham, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Selective neuronal cell death in the CA1 region of the hippocampus and layer III cortical neurons after asphyxial cardiac arrest in PND 16 – 18 rats. A and C. Fluorojade B labeling (green) of degenerating neurons in CA1 hippocampus 5 wk after sham-injury (A) or asphyxia (C). Inset, higher magnification; sections were co-labeled with DAPI which stains cell nuclei blue. B and D. H&E staining (upper inset, higher magnficiation) and TUNEL (lower inset; brown nuclear labeling) in CA1 hippocampus 7 d after sham-injury (B) or asphyxia (D). E-G. Degenerating neurons in layer III cortical neurons at 7 d.

Fig. 5.

CA1 hippocampal neuron density in PND 16 – 18 rats assessed at 5 wk after recovery from 8 min asphyxial cardiac arrest or sham-injury. Mean ± SEM, n = 9/group, *P < 0.001 vs. sham.

Fluorojade B labeling and ischemic neuronal changes, but not TUNEL, were also seen in motor and somatosensory cortices, predominantly layer III (Fig. 4E-G). In the CA1 hippocampus approximately 50-70% of neurons were labeled with Fluorojade B (non-Fluorojade B labeled neurons were detected by DAPI staining). Fluorojade B labeling in layer III cortical neurons was less dense compared with the CA1 hippocampus, and was seen in approximately 20-50% of neurons in this region. Occasional TUNEL and Fluorojade B positive cells were also seen in the hilas and cerebellum at 3-7 d (not shown). Selective neuronal degeneration in CA1 hippocampal neurons and layer III cortical neurons without infarction, seen in this model, is consistent with other models of complete global ischemia with reperfusion.

Discussion

Since 1980 there have been over 250 scientific reports utilizing a model of neonatal hypoxia-ischemia (Rice-Vannucci model). This model requires permanent unilateral carotid artery occlusion and temporary systemic hypoxemia to produce focal cerebral infarction and impaired brain development (10) and is feasible in neonatal (PND 7) rats. This model has produced many seminal findings related to hypoxic-ischemic damage in the developing brain related to both mechanism (including: (22, 23) and treatment (including: (24-26), leading to a significant advancement in the understanding of neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Parallel studies examining mechanisms and treatment in age-appropriate models of pediatric hypoxia-ischemia; however, are lacking. The development of a piglet model of asphyxial cardiac arrest has led to progress in this regard, particularly in relation to studies determining the effectiveness of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (27). In addition, Agnew and colleagues have recently reported that 24 h of hypothermia reduces striatal damage in PND 5-7 day old piglets after 30 min of hypoxia followed by 7 min of asphyxia (12). Mechanistic information can also be extrapolated from models of temporary global ischemia such as the four-vessel occlusion model (28) or cardiac arrest initiated by ventricular fibrillation (29). However, these models lack a period of systemic hypoxemia prior to cardiac arrest, an important mechanistic factor determining cell fate after insult (30), and a key factor in pediatric cardiopulmonary arrest.

We report a model of pediatric cardiopulmonary arrest that has many clinically relevant features. This model closely mimics the clinical scenario of cardiopulmonary arrest in infants and children, i.e. respiratory arrest with systemic hypoxemia followed sequentially by cardiac arrest, resuscitation and reperfusion. In addition, the model produces significant hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and neurodegeneration. Certain neurons, such as those in the CA1 hippocampus and layer III cortex are known to be selectively vulnerable to cellular damage from global hypoxia-ischemia with reperfusion (28). Importantly, selective vulnerability of hippocampal neurons has also been described in humans after cardiopulmonary arrest (31, 32). Similarly in this study, evidence of selective neurodegeneration in these regions was detected using histological assessment and Flurojade-B. Flurojade B is reportedly specific primarily for degenerating neurons; however, vascular elements and choroid plexus can also stain positively (20). Although white matter damage was not detected by either standard histological assessment or Flurojade-B, further study is necessary utilizing specific methods such as somatosensory evoked potentials (33) or biochemical markers of white matter damage (34) to determine if white matter injury occurs in this model. White matter damage is a prominent finding in both experimental and clinical perinatal asphyxia (35-37), and thus may occur after asphyxial cardiac arrest outside the perinatal period as well. Detection of DNA damage by TUNEL and cellular morphology in the CA1 hippocampus suggests that some degree of cell death occurs via apoptosis in this model, also consistent with experimental models of ischemia-reperfusion in adult animals (38), and a mechanism operative in infants and children after acute brain injury (39).

This model produces quantifiable and persistent, acute and long-term functional deficits. The presence of functional neurological deficits and the effect of treatment on functional neurological outcome over an extended observation period are important for the determination of clinical relevance of potential therapies in models of cerebral ischemia (40, 41). Profound motor function deficits were observed using the beam balance and inclined plane tests, anatomically corresponding to neurodegeneration within the cerebral cortex. Differences between asphyxia and sham groups in the Morris water maze were more modest. In this study, approximately 60% CA1 hippocampal neuronal loss was seen. Others have reported that near total destruction of the dorsal CA1 hippocampus is required to produce robust deficits in spatial memory acquisition (42), suggesting that the duration of insult in our model may have to be increased in order to produce readily quantifiable cognitive impairment of a magnitude useful for testing of therapies.

PND 16 – 18 rats were used based upon a number of factors and criteria. PND 16 – 18 represents a time of active synaptogenesis (43-46), analogous to young children, and is also a critical time when mature synaptic function, important in memory formation, is being established (47). Moreover, brain growth velocities, alterations in energy metabolism, and neurotransmitter system development in PND 16 – 18 rats have important parallels with toddler-aged children (48-50). Thus, injury in this model occurs at a stage where CNS development is roughly equivalent to that of a 2 – 4 year old human (46). PND 16-18 rats appear to tolerate asphyxia better than adult rats, given that a shorter duration of asphyxia (7 min) produces significant Morris-water maze deficits in adult rats (15). Furthermore, 8 min of asphyxia produces more widespread neuronal damage in adult vs. PND 16-18 rats, with moderate injury seen in thalamus and cerebellum (not seen after 8 min of asphyxia in PND 16-18 rats), in addition to hippocampal and cortical damage (16). This parallels the clinical impression that pediatric patients are more resistant to ischemic injury than adult patients.

In conclusion, a model of pediatric cardiopulmonary arrest has been developed that may prove useful for investigating mechanisms resulting in hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in the developing brain. Future pre-clinical studies testing both currently available and novel therapies utilizing this model appear warranted.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Robert Garman for supplying the Fluorjade B method. We appreciate the generous support from the Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh and the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurologic Diseases and Stroke RO1 NS 38620 and P50 NS30318.

References

- 1.Young KD, Seidel JS. Pediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a collective review. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:195–205. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70394-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borta M. Psychosocial issues in water-related injuries. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 1991;3:325–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ronco R, King W, Donley DK, et al. Outcome and cost at a children's hospital following resuscitation for out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:210–4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170140092017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuisma M, Suominen P, Korpela R. Paediatric out-of-hospital cardiac arrests--epidemiology and outcome. Resuscitation. 1995;30:141–50. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(95)00888-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reis AG, Nadkarni V, Perondi MB, et al. A prospective investigation into the epidemiology of in-hospital pediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation using the international Utstein reporting style. Pediatrics. 2002;109:200–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson CM, Joffe AR, Moore AJ, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome of young pediatric intensive care unit survivors of serious brain injury. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2002;3:345–350. doi: 10.1097/00130478-200210000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kochanek PM, Clark RS, Ruppel RA, et al. Cerebral resuscitation after traumatic brain injury and cardiopulmonary arrest in infants and children in the new millennium. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001;48:661–81. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70333-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, et al. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:557–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Hypothermia After Cardiac Arrest Study Group. Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:549–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rice JE, 3rd, Vannucci RC, Brierley JB. The influence of immaturity on hypoxic-ischemic brain damage in the rat. Ann Neurol. 1981;9:131–41. doi: 10.1002/ana.410090206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berg RA, Otto CW, Kern KB, et al. A randomized, blinded trial of high-dose epinephrine versus standard-dose epinephrine in a swine model of pediatric asphyxial cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:1695–700. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199610000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agnew DM, Koehler RC, Guerguerian AM, et al. Hypothermia for 24 hours after asphyxic cardiac arrest in piglets provides striatal neuroprotection that is sustained 10 days after rewarming. Pediatr Res. 2003;54:253–262. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000072783.22373.FF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hendrickx HH, Rao GR, Safar P, et al. Asphyxia, cardiac arrest and resuscitation in rats. I. Short term recovery. Resuscitation. 1984;12:97–116. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(84)90062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz L, Ebmeyer U, Safar P, et al. Outcome model of asphyxial cardiac arrest in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1995;15:1032–9. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1995.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hickey RW, Akino M, Strausbaugh S, et al. Use of the Morris water maze and acoustic startle chamber to evaluate neurologic injury after asphyxial arrest in rats. Pediatr Res. 1996;39:77–84. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199601000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hickey RW, Ferimer H, Alexander HL, et al. Delayed, spontaneous hypothermia reduces neuronal damage after asphyxial cardiac arrest in rats. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3511–6. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200010000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Statler KD, Kochanek PM, Dixon CE, et al. Isoflurane improves long-term neurologic outcome versus fentanyl after traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2000;17:1179–89. doi: 10.1089/neu.2000.17.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adelson PD, Dixon CE, Robichaud P, et al. Motor and cognitive functional deficits following diffuse traumatic brain injury in the immature rat. J Neurotrauma. 1997;14:99–108. doi: 10.1089/neu.1997.14.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark RSB, Kochanek PM, Watkins SC, et al. Caspase-3 mediated neuronal death after traumatic brain injury in rats. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2000;74:740–753. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.740740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmued LC, Albertson C, Slikker W., Jr Fluoro-Jade: a novel fluorochrome for the sensitive and reliable histochemical localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain Res. 1997;751:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01387-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clark RSB, Chen J, Watkins SC, et al. Apoptosis-suppressor gene bcl-2 expression after traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurosci. 1997;17:9172–9182. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09172.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dwyer BE, Nishimura RN, Powell CL, et al. Focal protein synthesis inhibition in a model of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 1987;95:277–89. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(87)90138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin LJ, Brambrink AM, Lehmann C, et al. Hypoxia-ischemia causes abnormalities in glutamate transporters and death of astroglia and neurons in newborn striatum. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:335–48. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altman DI, Young RS, Yagel SK. Effects of dexamethasone in hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in the neonatal rat. Biol Neonate. 1984;46:149–56. doi: 10.1159/000242058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young RS, Olenginski TP, Yagel SK, et al. The effect of graded hypothermia on hypoxic-ischemic brain damage: a neuropathologic study in the neonatal rat. Stroke. 1983;14:929–34. doi: 10.1161/01.str.14.6.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng Y, Deshmukh M, D'Costa A, et al. Caspase inhibitor affords neuroprotection with delayed administration in a rat model of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1992–1999. doi: 10.1172/JCI2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berg RA, Hilwig RW, Kern KB, et al. “Bystander” chest compressions and assisted ventilation independently improve outcome from piglet asphyxial pulseless “cardiac arrest”. Circulation. 2000;101:1743–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.14.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pulsinelli WA, Brierley JB. A new model of bilateral hemispheric ischemia in the unanesthetized rat. Stroke. 1979;10:267–72. doi: 10.1161/01.str.10.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bottiger BW, Schmitz B, Wiessner C, et al. Neuronal stress response and neuronal cell damage after cardiocirculatory arrest in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:1077–87. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199810000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vaagenes P, Safar P, Moossy J, et al. Asphyxiation versus ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest in dogs. Differences in cerebral resuscitation effects--a preliminary study. Resuscitation. 1997;35:41–52. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(97)01108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ng T, Graham DI, Adams JH, et al. Changes in the hippocampus and the cerebellum resulting from hypoxic insults: frequency and distribution. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1989;78:438–43. doi: 10.1007/BF00688181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kinney HC, Korein J, Panigrahy A, et al. Neuropathological findings in the brain of Karen Ann Quinlan. The role of the thalamus in the persistent vegetative state. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1469–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405263302101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lesnick JE, Coyer PE, Michele JJ, et al. Comparison of the somatosensory evoked potential and the direct cortical response following severe incomplete global ischemia: selective vulnerability of the white matter conduction pathways. Stroke. 1986;17:1247–50. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.6.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Povlishock JT, Erb DE, Astruc J. Axonal response to traumatic brain injury: Reactive axonal change, deafferentation, and neuroplasticity. J Neurotrauma. 1992;9:S189–S200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thoresen M, Haaland K, Loberg EM, et al. A piglet survival model of posthypoxic encephalopathy. Pediatric Research. 1996;40:738–48. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199611000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.du Plessis AJ, Volpe JJ. Perinatal brain injury in the preterm and term newborn. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2002;15:151–7. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200204000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rose VC, Shaffner DH, Gleason CA, et al. Somatosensory evoked potential and brain water content in post-asphyxic immature piglets. Pediatric Research. 1995;37:661–6. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199505000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graham SH, Chen J. Programmed cell death in cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:99–109. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clark RS, Kochanek PM, Adelson PD, et al. Increases in bcl-2 protein in cerebrospinal fluid and evidence for programmed cell death in infants and children after severe traumatic brain injury. J Pediatr. 2000;137:197–204. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.106903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hunter AJ, Mackay KB, Rogers DC. To what extent have functional studies of ischaemia in animals been useful in the assessment of potential neuroprotective agents? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19:59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01157-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corbett D, Nurse S. The problem of assessing effective neuroprotection in experimental cerebral ischemia. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;54:531–48. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nelson A, Lebessi A, Sowinski P, et al. Comparison of effects of global cerebral ischaemia on spatial learning in the standard and radial water maze: relationship of hippocampal damage to performance. Behavioural Brain Research. 1997;85:93–115. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)00167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Izumi Y, Zorumski CF. Developmental changes in long-term potentiation in CA1 of rat hippocampal slices. Synapse. 1995;20:19–23. doi: 10.1002/syn.890200104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jackson PS, Suppes T, Harris KM. Stereotypical changes in the pattern and duration of long-term potentiation expressed at postnatal days 11 and 15 in the rat hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1412–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.4.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harris KM, Jensen FE, Tsao B. Three-dimensional structure of dendritic spines and synapses in rat hippocampus (CA1) at postnatal day 15 and adult ages: implications for the maturation of synaptic physiology and long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2685–705. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02685.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rice D, Barone S., Jr Critical periods of vulnerability for the developing nervous system: evidence from humans and animal models. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108 3:511–33. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakazawa K, Quirk MC, Chitwood RA, et al. Requirement for hippocampal CA3 NMDA receptors in associative memory recall. Science. 2002;297:211–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1071795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dobbing J, Sands J. Comparative aspects of the brain growth spurt. Early Human Development. 1979;3:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(79)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Booth RF, Patel TB, Clark JB. The development of enzymes of energy metabolism in the brain of a precocial (guinea pig) and non-precocial (rat) species. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1980;34:17–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1980.tb04616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hagberg H, Bona E, Gilland E, et al. Hypoxia-ischaemia model in the 7-day-old rat: possibilities and shortcomings. Acta Paediatrica. 1997;422(Supplement):85–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb18353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]