Abstract

Background. Back pain is a common problem and a major cause of disability and health care utilization. Purpose. To evaluate the efficacy, harms, and costs of the most common CAM treatments (acupuncture, massage, spinal manipulation, and mobilization) for neck/low-back pain. Data Sources. Records without language restriction from various databases up to February 2010. Data Extraction. The efficacy outcomes of interest were pain intensity and disability. Data Synthesis. Reports of 147 randomized trials and 5 nonrandomized studies were included. CAM treatments were more effective in reducing pain and disability compared to no treatment, physical therapy (exercise and/or electrotherapy) or usual care immediately or at short-term follow-up. Trials that applied sham-acupuncture tended towards statistically nonsignificant results. In several studies, acupuncture caused bleeding on the site of application, and manipulation and massage caused pain episodes of mild and transient nature. Conclusions. CAM treatments were significantly more efficacious than no treatment, placebo, physical therapy, or usual care in reducing pain immediately or at short-term after treatment. CAM therapies did not significantly reduce disability compared to sham. None of the CAM treatments was shown systematically as superior to one another. More efforts are needed to improve the conduct and reporting of studies of CAM treatments.

1. Introduction

Back pain is a general term that includes neck, thoracic, and lower-back spinal pain. In the majority of cases, the aetiology of back pain is unknown and therefore is considered as “nonspecific back pain”. Back pain is considered “specific” if its aetiology is known (e.g., radiculopathy, discogenic disease). Although back pain is usually self-limited and resolves within a few weeks, approximately 10% of the subjects develop chronic pain, which imposes large burden to the health-care system, absence from work, and lost productivity [1]. In a recent study, the direct costs of back pain related to physician services, medical devices, medications, hospital services, and diagnostic tests were estimated to be US$ 91 billion or US$ 46 per capita [2]. Indirect costs related to employment and household activities were estimated to be between US$ 7 billion and US$ 20 billion, or between US$25 and US$ 71 per capita, respectively [3–5]. One study published in 2007 showed that the 3-month prevalence of back and/or neck pain in USA was 31% (low-back pain: 34 million, neck pain: nine million, both back and neck pain: 19 million) [6].

The prevalence of back pain and the number of patients seeking care with complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies in the US has increased over the last two decades [7]. The most prevalent CAM therapies for back and neck pain in the US are spinal manipulation, acupuncture, and massage [7]. The exact mechanisms of action of CAM therapies remain unclear. Recently, many randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted to study the effects of CAM therapies for back pain. The results of many systematic reviews [8–12], meta-analyses [13], and clinical practice guidelines [14–17] regarding the effectiveness of CAM therapies for back pain relative to no treatment, placebo, or other active treatment(s) in reducing pain and disability have been inconsistent.

The agency for healthcare research and quality (AHRQ) and the national center for complementary and alternative medicine (NCCAM) commissioned the University of Ottawa Evidence-based Practice Center (UO-EPC) to review and evaluate evidence regarding the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and safety of the most prevalent CAM therapies (i.e., acupuncture, manipulation, mobilization, and massage) used in the management of back pain. This technical report can be viewed at the AHRQ website (http://www.ahrq.gov/) [18]. The present paper summarizes the evidence from this technical report with a focus on a subset of studies reporting pain, disability, and harms outcomes compared between CAM therapies and other treatment approaches deemed relevant to primary care physicians (i.e., waiting list, placebo, other CAM therapies, pain medication, and physical therapy including exercise, electrotherapy and/or other modalities). The specific aims of this study were to systematically review and compare the efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and safety of acupuncture, manipulation, mobilization, and massage in adults (18 years or older) with neck or low-back pain.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Searches

We searched MEDLINE (1966 to February 2010), EMBASE (1980 to week 4 2010), the Cochrane Library (2010 Issue 1), CINAHL (1982 to September 2008), AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine Database: 1985 to January 2010), Mantis (1880 to October 2008), and EBM Reviews—ACP Journal Club (1991 to August 2008). Two specialized CAM databases, the Index to Chiropractic Literature (ILC; October 2008) and Acubriefs (2008 October) were also searched. We searched using controlled vocabulary and keywords for conditions pertaining to neck pain, back pain, spinal diseases, sciatica, and various CAM interventions including acupuncture, electroacupuncture, needling, acupressure, moxibustion, manipulative medicine, manipulation, chiropractic, and massage. (Appendix A: Complete search strategies for each database). The searches were not restricted by language or date. We also reviewed reference lists of eligible publications.

2.2. Study Selection

RCTs reporting efficacy and/or economic data of CAM therapies in comparison with no treatment, placebo, or other active treatments in adults with low-back, neck, or thoracic pain were eligible. Nonrandomized controlled trials and observational studies (e.g., cohort, case-control, cross-sectional) reporting harms were also included. Reports published in English, German, Dutch, Chinese, Japanese, Italian, French, Portuguese, and Spanish were eligible for inclusion. Systematic and narrative reviews, case reports, editorials, commentaries or letters to the editor were excluded.

Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts and later reviewed the full-text reports of potentially eligible records. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

2.3. Data Extraction and Risk of Bias Assessment

Two independent reviewers extracted data on study and population characteristics, treatment, study outcomes, and duration of posttreatment followup. The abstracted data were verified and conflicts were resolved by consensus.

Treatment efficacy outcomes were pain intensity (e.g., Visual Analog Scale-VAS, McGill Pain Questionnaire-MPQ) and disability (e.g., Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire-RMDQ, Northwick Park Neck Pain Questionnaire-NPQ, Pain Disability Index-PDI, Oswestry Disability Index). The timing of posttreatment followup for outcomes was ascertained and categorized into four groups: immediate, short- (<3 months), intermediate- (3 to 12 months), and long-term (>12 months) posttreatment followup. Harms (e.g., any adverse event, withdrawals due to adverse events, specific adverse events) were extracted as proportions of patients with an event.

For cost-effectiveness analysis, data was extracted on: (a) costs to the health care sector, (b) costs of production loss, (c) costs in other sectors, (d) patient and family costs, and (e) total costs.

The risk of bias for RCTs was assessed using the 13-item criteria list (item rating: Yes, No, Unclear) recommended in the Updated Method Guidelines for Systematic Reviews in the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group [19]. The risk of bias for each RCT was classified into three groups: good (score: 4), fair (score: 2-3), and poor (score: 0-1) depending on the number of “Yes” ratings (score range: 0–4) across the four domains (treatment allocation concealment, balance in baseline characteristics, blinding, and number/reasons for dropouts). Assessment of quality of reporting in observational studies was done by using the modified 27-item tool of Downs and Black [20]. Methodological quality of economic studies was determined using the 19-item Consensus Health Economic Criteria [21].

2.4. Rating the Strength of the Body of Evidence

The overall strength (i.e., quality) of evidence was assessed using the grading system outlined in the Methods guide prepared for the AHRQ Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) program [22]. The grading was based on four domains: overall risk of bias, consistency, directness, and precision (applied to pooled results only). The overall risk of bias (high, medium, and low) was derived by averaging the risk of bias (good, fair, and poor) across individual trials. If evidence consisted of only one study (or multiple studies of the same risk of bias score), then the risk of bias for individual study corresponded to the overall risk of bias for this evidence as follows: “poor” (score: 0 or 1) = risk of bias (high), “fair” (score: 2 or 3) = risk of bias (medium), and “good” (score: 4) = risk of bias (low). In case of evidence consisting of multiple studies with different risk of bias scores (studies that scored “poor”, “fair”, and “good” mixed together), the mean risk of bias score (i.e., mean number of “Yes”) was calculated and the overall risk of bias was defined as “high” (mean score < 2), “medium” (2 ≤ mean score < 4), and “low” (mean score = 4). Consistency was judged based on qualitative assessment of forest plots of meta-analyses (direction and 95% confidence intervals of the effects in individual trials). Results were considered consistent when statistically significant or nonsignificant effects in the same direction were observed across trials. When pooling was not possible, consistency was judged based on qualitative summary of the trial results. The pooled estimate with relatively narrow 95% CIs leading to clinically uniform conclusions was considered as “precise evidence”. Relevant health outcomes (pain, disability) were defined as “direct” as opposed to intermediate or surrogate outcomes (“indirect”). The grade of the evidence for a given outcome was classified into four groups: high, moderate, low, or insufficient (no evidence). The initial “high” grade was reduced by one level (from high to moderate) for each of the domains not met (i.e., overall risk of bias, consistency, directness, precision) and by two levels in case of high risk of bias (e.g., from high to low grade).

2.5. Data Synthesis and Analysis

The results were grouped according to the type of experimental intervention (e.g., acupuncture, manipulation, mobilization, massage), pain location in spinal region (low-back, neck, head, thorax), duration of pain (acute/subacute, chronic, mixed, unknown), and cause of pain (specific, nonspecific). Study, treatment, population, and outcome characteristics were summarized in text and summary tables.

We meta-analyzed RCTs with similar populations (demographics, cause, location, and duration of spinal pain), same types of experimental and controls treatments, and outcomes measured with the same instruments (and scale) at similar posttreatment followup time points. The meta-analyses of pain were based on the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS; score range: 1–10). The random-effects models of DerSimonian and Laird were used to generate pooled estimates of weighted end point mean difference (WMDs) with 95 percent confidence intervals (95% CIs). Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated using the Chi-square test and the I 2 statistic (low: 25.0%; moderate: 50.0%; high: 75.0%). Subgroup (e.g., patients' age, gender) and sensitivity (e.g., trial quality) analyses were planned to investigate the sources of heterogeneity.

The degree of clinical importance for the observed differences in pain scores between the treatment groups was specified according to the Updated Method Guidelines of Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group [19]: small (WMD < 10% of the VAS scale), medium (10% ≤ WMD < 20% of the VAS scale), and large (WMD ≥ 20% of the VAS scale).

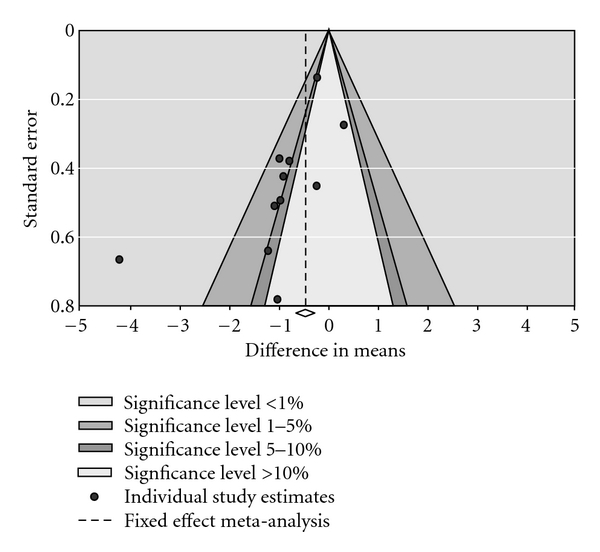

Publication bias was examined through visual inspection of funnel plot asymmetry and the Egger's regression-based method [23].

2.6. Role of the Funding Source

This topic was nominated by NCCAM and selected by AHRQ. A representative from AHRQ served as a Task Order Officer and provided technical assistance during the conduct of the full evidence report and comments on draft versions of the full evidence report. AHRQ did not directly participate in the literature search, determination of study eligibility criteria, data analysis or interpretation, preparation, review, or approval of the paper for publication.

3. Results

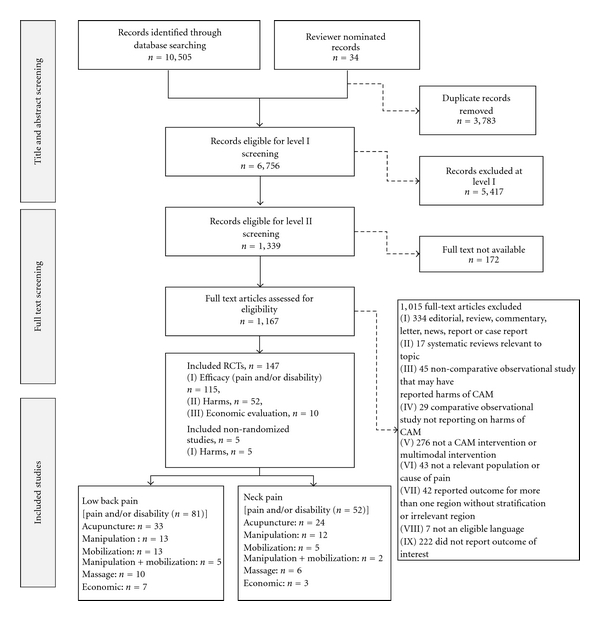

Our literature search identified 152 unique studies: 147 RCTs and 5 nonrandomized studies (1 controlled trial and 4 observational) were included in the review (Figure 1). One hundred and fifteen RCTs reported data on efficacy (pain and disability) and/or harms. Additionally, 23 RCTs that did not report pain and disability outcomes provided data on harms. Five nonrandomized studies reported harms. Ten RCTs reported on cost-effectiveness (one of the 10 RCTs also reported efficacy).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

3.1. Study Characteristics

The included studies were published between 1978 and 2009. The studies were published in English (74.5%), Chinese (3.3%; all acupuncture) [24–28], German (<1.0%; massage of lumbar region) [29], Japanese (2.6%; all acupuncture) [30–33], and one in Spanish (spinal mobilization) [34]. All 10 reports of economic evaluation of CAM treatments were published in English [35–44].

3.2. Population Characteristics

The majority of trials (>90%) included adult men and women aged 18–65 years. Six trials included adults aged 55 years or older [45–50]. In total, 61% of all studies included subjects with nonspecific pain. About 85%, 14%, and 12% of acupuncture, spinal manipulation/mobilization, and massage trials, respectively, enrolled subjects with nonspecific cause of back pain. The remaining trials enrolled subjects with specific causes of back pain (e.g., disc perturbation, whiplash, myofascial pain, cervicogenic headache, or underlying neurological causes).

3.3. Treatment Characteristics

3.3.1. Acupuncture Studies

A large variety of methods of acupuncture treatments were used to compare the effect of acupuncture and control treatments. The control treatments in these trials included active (i.e., physical modalities and exercise) or inactive treatments (i.e., placebo, no treatment). The treatment providers were trained or licensed acupuncturists, general practitioners or physicians with especial training in acupuncture, neuropathy physicians, general practitioners, and trained physiotherapists. In the majority of Chinese trials, the treatment provider was referred as “therapist”.

3.3.2. Manual Treatment Studies

Interventions were provided by experienced and licensed chiropractors, physical therapists, general practitioners, licensed or qualified manual therapy practitioners, nonspecified clinicians, neurologists or rheumatologists, folk healers, and osteopaths.

3.3.3. Massage Studies

Treatment providers were licensed or experienced massage therapists, physical therapists, reflexologists, acupressure therapists, folk healers, general practitioners, manual therapists, experienced bone setters, and chiropractic students.

3.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.4.1. RCTs Reporting Efficacy and Harms

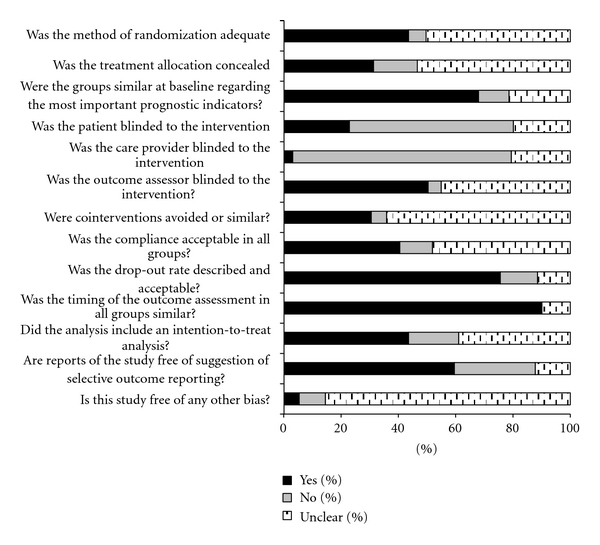

The risk of bias was assessed for 131 RCTs. Overall, the methodological quality of the RCTs was poor (median score = 6/13; inter-quartile range: 4, 7). Only 71 (54%) of the studies scored 6 or higher based on the 13 items of risk of bias tool. An adequate method of randomization was described in 57 (43.5%) studies. The remaining 74 studies either did not report the method used for randomization (n = 8; 6.0%) or the method used was not clearly described (n = 66; 50.0%). Concealment of treatment allocation was judged as adequate for 41 (31.3%) of RCTs and inadequate for 20 (15.3%) of RCTs (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Table 1.

Risk of bias assessment of RCTs of all interventions for low-back pain and neck pain (total of 131 RCTs).

| Quality components | N studies | % |

|---|---|---|

| Adequate method of randomization | 57 | 43.5% |

| Adequate method of allocation concealment | 41 | 31.3% |

| Similarity at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators | 89 | 67.9% |

| Appropriate patient blinding to the intervention | 30 | 22.9% |

| Appropriate care provider blinding to the intervention | 4 | 3.1% |

| Appropriate outcome assessor blinding to the intervention | 66 | 50.4% |

| Similar or no cointerventions between-groups | 40 | 30.5% |

| Acceptable compliance in all groups | 53 | 40.5% |

| Described and acceptable drop-out rates | 99 | 75.6% |

| Similarity of timing of the outcome assessment in all groups | 118 | 90.1% |

| Inclusion of an intention-to-treat analysis | 57 | 45.5% |

| Absence of selective outcome reporting | 78 | 59.5% |

| Absence of other potential bias | 7 | 5.3% |

|

| ||

| Total risk of bias scores (max 13); median (IQR) | 6 | 4–7 |

Figure 2.

3.4.2. RCTs Reporting Economic Evaluation

Of the 10 studies reporting cost-effectiveness data, 3 studies collected costs appropriate to their chosen perspective. Two studies did not state the perspective adopted for the economic evaluation. Most studies measured costs using diaries, questionnaires, practice/insurance records, and valued costs appropriately using published sources. Most studies conducted an incremental cost-effectiveness analysis. The length of followup across the studies was at least one year. In one study with a length of followup of more than one year, discounting was undertaken [39].

3.4.3. Observational Studies (Cohort and Case-Control)

The objectives and the main outcome (an adverse event) of the 4 studies were well described. The studies had a large sample size ranging from 68 to 3982 subjects, providing sufficient power to detect clinically important effects.

3.5. Efficacy of Acupuncture for Low-Back Pain

This section included 33 trials (Table 2 for efficacy results and evidence grading (Appendix B)) [26, 30–33, 35, 36, 41, 45, 47–49, 51–73]. One study [26] was published in Chinese and four studies were published in Japanese [30–33]. The trials were conducted in China (37%), Europe (United Kingdom, Germany, Ireland, and Sweden; 35%), and USA (28%).

Table 2.

Summary of findings of acupuncture for low-back pain (only pain and functional outcomes).

| Duration and cause of pain | Outcomes | GRADE* | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acupuncture versus no treatment | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, mixed, and unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Moderate

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: yes Directness: yes Precision: yes |

Four trials showed a significant immediate/short-term posttreatment benefit of acupuncture [35, 48, 51, 52]. The pooled estimate was based on 3 trials (short-term posttreatment mean score difference: −1.19, 95% CI: −2.17 to −0.21) [35, 48, 52]. See Figure 3. |

| Pain Disability Index |

Moderate

Design: RCT ROB: Low Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

One trial showed greater improvement in pain disability index with acupuncture (Mean difference: −8.2, 95% CI: −12.0 to −4.4) [51]. | |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Acupuncture versus placebo | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Moderate

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: yes Directness: yes |

In two trials [31, 53], short-term posttreatment pain intensity score was not significantly different between acupuncture and placebo groups. Mean score difference: 10.6, 95% CI: −4.1, 25.3,Mean score: 49.9 ± 22.2 versus 51.8 ± 26.1, P > 0.05). |

| Roland-Morris Disability score |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial, acupuncture was not significantly different from placebo at 3 months (mean score difference: 2.6, 95% CI: −0.7, 5.9) [53]. | |

|

| |||

| Acute/sub acute specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Pain intensity score (modified MPQ, VAS, von Korff Chronic Pain Grade Scale: 0–10) |

Moderate

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: yes Directness: yes Precision: yes |

Acupuncture was compared to placebo in 16 trials [32, 45, 51, 54–67]. The results of these trials were conflicting. The pooled estimates of 10 trials showed a significant benefit of acupuncture but only immediately posttreatment (mean score difference −0.59, 95% CI: −0.93, −0.25) [51, 55, 56, 58, 59, 61–65, 67]. The mean score differences at short- (−1.11, 95% CI: −2.33, 0.11) [54–56, 58], intermediate- (−0.18, 95% CI: −0.85, 0.49) [51, 54, 67], and long-term (−0.21, 95% CI: −0.64, 0.22) [51, 54, 63, 67] followups after the sessions were not statistically significant. See Figure 4 |

| Roland-Morris Disability score |

Moderate

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: yes Directness: yes |

The pooled estimate of two trials was not statistically significant (mean score difference: 0.81, 95% CI: −0.27, 1.9) [62, 67]. | |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mixed (specific, nonspecific) | NA | NA | NA |

|

| |||

| Unknown nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Moderate

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: yes Directness: yes |

In one trial [68], there was no significant difference in the proportions of subjects with improved pain (not specified) between the acupuncture versus placebo (sham-acupuncture). Either real needling [30] or total body acupuncture [33] was superior to sham needling in reducing pain intensity immediately posttreatment. For example, in one study [30], the mean pain intensity (VAS score) was 37.3 in acupuncture group and 64.1 in the placebo group. |

|

| |||

| Unknown specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Acupuncture versus medication | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: no Directness: yes |

There was no significant difference between acupuncture and medication immediately posttreatment. The pooled estimate was based on four trials (mean score difference: 0.11, 95% CI: −1.42, 1.65) [49, 69–71]. |

| Oswestry Disability Index |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: no Directness: yes |

In one trial, [69, 72] acupuncture achieved better score than medication (13 versus 24). The pooled estimate based on two trials showed no significant difference (mean score difference: −2.40, 95% CI: −12.20, 7.40) [69, 70]. | |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mixed nonspecific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mixed specific | No pain or function outcome reported | — | NR |

|

| |||

| Unknown nonspecific | No pain or function outcome reported | — | NR |

|

| |||

| Unknown specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Acupuncture versus physiotherapy | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute (specific, nonspecific) |

Insufficient

No trial |

||

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Oswestry Disability Index |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

One trial showed manual acupuncture to be significantly superior to physiotherapy (consisted of light, electricity, and/or heat therapy) [26]. Acupuncture group: 38.58 ± 5.0 (before) and 11.55 ± 3.24 (after) Physiotherapy group: 40.24 ± 5.8 (before) and 18.83 ± 5.24 (after). |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mixed/unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Acupuncture versus manipulation | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute (specific, nonspecific) |

Insufficient

No trial |

||

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: no Directness: yes Precision: yes |

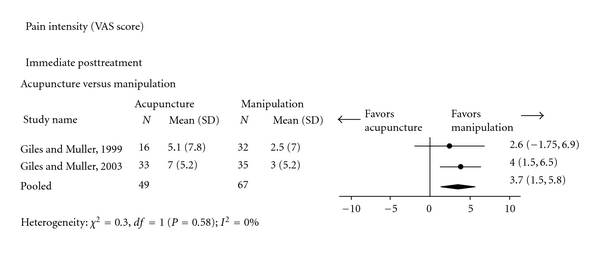

There were significant reductions in pain intensity in favour of manipulation (pooled mean difference in VAS score: 3.70, 95% CI: 1.5, 5.8) [69, 70]. See Figure 5. |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mixed/unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Acupuncture versus massage | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Symptom bothersomeness scale score (0 to 10) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

One trial showed massage to be significantly better than manual acupuncture at long-term followup (P = 0.002) [36]. Massage group—at baseline: 6.2 (95% CI: 5.8, 6.6) and at 1 year: 3.2 (95% CI: 2.5, 3.9). Acupuncture group—at baseline: 6.2 (95% CI: 5.8, 6.5) and 4.5 (95% CI: 3.8, 5.2). |

| Roland-Morris Disability score |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

One trial showed massage to be significantly better than manual acupuncture at immediate- (P = 0.01) or long-term followup (P = 0.05) [36]. Mean values at baseline, 4 weeks and 1 year after treatment in the massage group: 11.8 (95% CI: 10.8, 12.7), 7.9 (95% CI: 6.9, 9.0), and 6.8 (95% CI: 5.5, 8.1) [36]. Mean values at baseline, 4 weeks and 1 year after treatment in the acupuncture group: 12.8 (95% CI: 11.7, 13.8), 9.1 (95% CI: 7.8, 9.9) and 8.0 (95% CI: 6.6, 9.3) [36]. |

|

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mixed/unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Acupuncture versus usual care | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute nonspecific | Roland-Morris Disability score |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [41], the addition of acupuncture to usual care did not improve the degree of disability (RMDQ score) compared to usual care alone immediately, shortly, or intermediate-term posttreatment. |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Roland-Morris Disability score |

Moderate

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: yes Directness: yes |

In two trials, subjects who received acupuncture significantly improved in disability compared to subjects in usual care groups at short-term or intermediate-term followup after treatment [47, 67]. |

| Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Moderate

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: yes Directness: yes |

In two trials, subjects who received acupuncture significantly improved in pain intensity compared to subjects in usual care groups at short-term or intermediate-term followup after treatment [47, 67]. | |

|

| |||

| Mixed specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mixed nonspecific | Disability score (Oswestry) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [208], a long-term posttreatment disability score was not significantly different between the acupuncture and usual care groups (Oswestry score: −3.4, 95% CI: −7.8, 1.0). |

| Pain intensity score (MPQ) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [208], a long-term posttreatment pain intensity was not significantly different between the acupuncture and usual care groups (mean difference in MPQ score: −0.2, 95% CI: −0.6, 0.1). | |

|

| |||

| Unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

*Precision in formal grading was applied only to pooled results.

VAS: visual analog scale; RMDQ: Roland-Morris disability scale; MPQ: McGill pain questionnaire; PDI: pain disability index; NPQ: neck pain questionnaire; NA: not applicable; ROB: risk of bias; RCT: randomized controlled trial.

3.5.1. Acupuncture versus Inactive Treatment

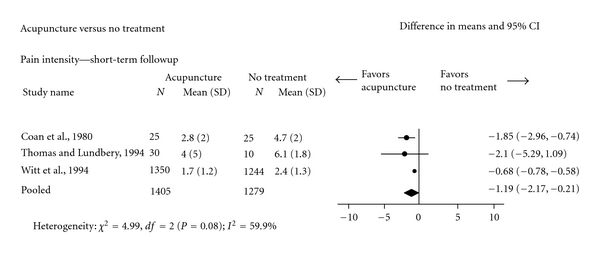

One meta-analysis (Figure 3) showed that subjects with chronic nonspecific LBP receiving acupuncture had statistically significantly better short-term posttreatment pain intensity (3 trials; pooled VAS: −1.19, 95% CI: −2.17, −0.21) [48, 52, 74] and less immediate-term functional disability (1 trial) [51] compared to subjects receiving no treatment.

Figure 3.

Acupuncture versus no treatment for chronic nonspecific low-back pain (Pain intensity: Visual Analogue Scale).

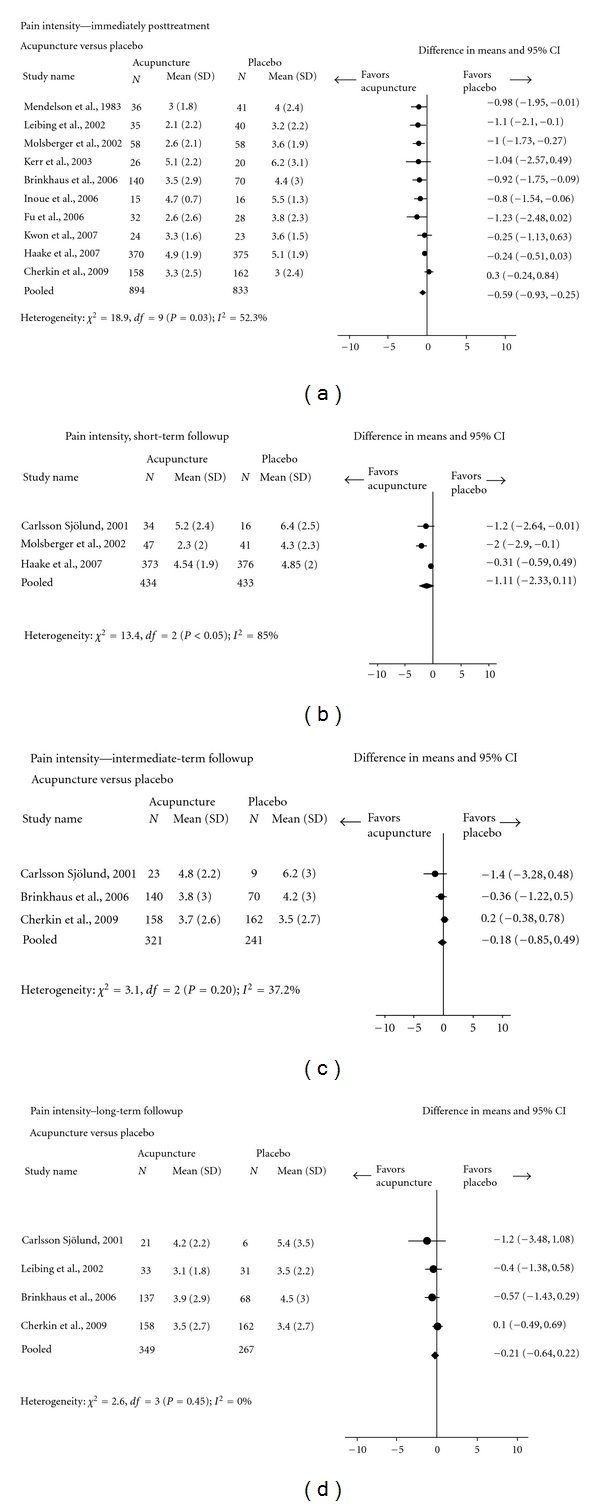

Trials comparing acupuncture to placebo yielded inconsistent results with respect to pain intensity. For subjects with acute/subacute nonspecific LBP, acupuncture did not significantly differ from placebo on pain or disability outcomes [31, 53]. In a meta-analysis (Figure 4) of subjects with chronic nonspecific LBP, acupuncture compared to placebo led to statistically significantly lower pain intensity, but only for the immediate-posttreatment followup (10 trials; pooled VAS: −0.59, 95% CI: −0.93, −0.25) [51, 55, 56, 58, 59, 61–65, 67]. The mean pain intensity scores in the acupuncture and placebo groups were not significantly different at short- [51, 55, 56, 58] intermediate-[51, 54, 58], and long-term [51, 54, 63, 67] followups. Acupuncture did not significantly differ from placebo in disability [62, 67]. Trials using sham-TENS, sham-laser, or placebo medication tended to produce results in favor of acupuncture in relation to pain intensity and disability compared to trials using sham-acupuncture.

Figure 4.

Acupuncture versus placebo for chronic nonspecific low-back pain (Pain intensity: Visual Analogue Scale).

3.5.2. Acupuncture versus Active Treatment

Two meta-analyses showed that acupuncture did not significantly differ from pain medication in reducing immediate posttreatment pain (4 trials; VAS score) [49, 69–71] or disability (2 trials; Oswestry score) [69, 70] in patients with chronic nonspecific low-back pain (Data is not presented in Figures).

Another meta-analysis (Figure 5), based on subjects with chronic nonspecific low-back pain, indicated that manipulation was significantly better than acupuncture in reducing pain immediately after the treatment (2 trials; VAS score: 3.70, 95% CI: 1.50, 5.80) [69, 70].

Figure 5.

Acupuncture versus Manipulation for chronic nonspecific low-back pain (Pain intensity: Visual Analogue Scale).

One trial showed that subjects receiving acupuncture had significantly better immediate posttreatment pain and disability than subjects receiving a combination of physical modalities (the light, electricity, heat) [26].

Massage was significantly better than acupuncture in reducing pain intensity and disability at immediate- or long-term followups for subjects with chronic nonspecific LBP [36].

Subjects with chronic nonspecific LBP receiving acupuncture compared with those receiving usual care (analgesics, anti-inflammatory drugs, primary care, recommendation for physical therapy visits) had significantly better short-/intermediate-term posttreatment pain intensity (2 trials; VAS score) [47, 67] and disability (2 trials; RMDQ score) [47, 67]. However, in subjects with acute nonspecific LBP, posttreatment disability (RMDQ) was not significantly different between the acupuncture plus usual care (limited bed rest, education, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, activity alterations) and usual care alone groups (1 trial) [41].

3.6. Efficacy of Acupuncture for Neck Pain

This section included 24 trials (Table 3 for efficacy results and evidence grading (Appendix B)) [24, 27, 28, 69, 70, 72, 75–94]. About 38% of studies were conducted in Europe (Germany, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, United Kingdom), 17% in Australia, 8% in Japan, and 8% in the USA. The remaining 29% of trials were conducted in Brazil, South Korea, and Taiwan. All studies in this section were published in English language.

Table 3.

Summary of findings of acupuncture for neck pain (only pain and functional outcomes).

| Duration and cause of pain | Outcomes | GRADE* | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acupuncture versus no treatment | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, chronic, and mixed, (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Unknown specific | Pain intensity score (SF-MPQ) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [75], acupuncture was significantly better than no treatment in reducing pain intensity short-term after the end of treatment (mean change: −15.2 ± 13.3 versus −5.3 ± 8.7, P = 0.043). |

|

| |||

| Unknown nonspecific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Acupuncture versus placebo | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute specific, nonspecific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Moderate

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: yes Directness: yes Precision: yes |

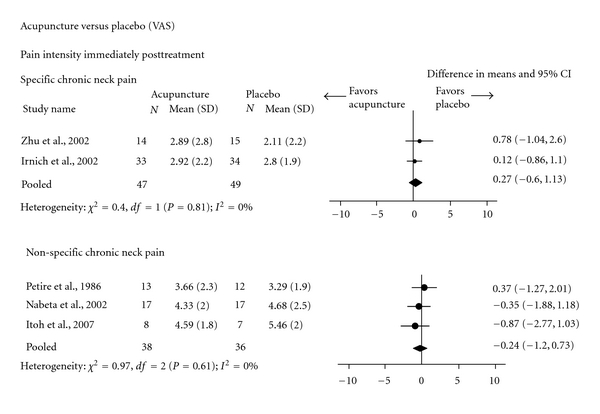

In three trials, acupuncture [77, 209] or dry needling [78] was similar to sham acupuncture [77] or laser acupuncture [78, 209] immediately or at short term after the treatment. In one of these trials [78], posttreatment mean VAS values in dry needling and sham laser acupuncture groups were 29.2 (±21.9) and 28.0 (±19.4), respectively. The meta-analysis of two trials indicated no significant difference between acupuncture and placebo immediately after the end of treatment (pooled mean difference: 0.27, 95% CI: −0.60, 1.13) [79]. See Figure 6. |

| NDI score |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [77], the mean disability score was not significantly different between acupuncture and sham-acupuncture groups immediately posttreatment (5.5 ± 4.5 versus 6.2 ± 3.1, P = 0.52). | |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: no Directness: yes Precision: yes |

The meta-analysis of three trials showed no significant difference between acupuncture and sham-acupuncture immediately posttreatment (pooled mean difference: −0.24, 95% CI: −1.20, 0.73) [80–82] (See Figure 6). Trials comparing acupuncture to other types of placebos (e.g., TENS, drug) [83, 85–87, 210] could not be pooled due to heterogeneity across outcomes, followup periods, or missing data. |

| NDI score |

Moderate

Design: RCT ROB: Low Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [83, 210], intermediate posttreatment mean disability was significantly reduced in acupuncture compared to placebo group (8.89 ± 6.57 versus 10.72 ± 9.11, P < 0.05). | |

|

| |||

| Mixed specific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [88], there was no significant difference between acupuncture and placebo (laser pen) at intermediate-term posttreatment followup (2.59 ± 2.18 versus 2.89 ± 2.63, P > 0.05). |

|

| |||

| Mixed nonspecific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Unknown specific | No pain or disability outcome reported | NA | One trial [27] reporting % subjects without symptoms. |

|

| |||

| Unknown nonspecific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Acupuncture versus pain medication | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, mixed (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | Pain intensity score (VAS, SF-MPQ) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: no Directness: yes |

Of the three trials [89–91] comparing acupuncture to medications, in two [89, 90] there was no significant difference between acupuncture and injection of lidocaine [89, 90], lidocaine plus corticoid [90], or botulinum toxin [90] at short-term posttreatment followup. In one of the trials [89], two-week posttreatment mean VAS values were 3.82 ± 2.47 for acupuncture and 3.46 ± 2.47 for lidocaine (P > 0.05). In another trial [91], acupuncture was better than NSAIDs immediately after treatment (mean VAS score: 1.87 ± 1.90 versus 4.76 ± 2.05, P < 0.05). |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: yes Directness: yes |

None of three trials comparing acupuncture to medication (e.g., NSAIDs, analgesics) demonstrated significant between-group differences [69, 70, 87]. In one of the trials [69], acupuncture had a better mean score versus pain medication group at immediate (mean VAS score: 4.0 ± 4.4 versus 6.0 ± 4.4) or at intermediate-term followup (mean VAS score: 2.5 versus 4.7) [69, 72]. |

|

| |||

| Unknown specific | Pain intensity score (VAS, SF-MPQ) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: yes Directness: yes |

In two trials [28, 92], acupuncture was significantly more effective than injection of lidocaine in the short-term. In one trial [28], the mean pain scores were 5.71 ± 2.49 versus 6.91 ± 3.22 (P < 0.05). |

|

| |||

| Unknown nonspecific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Acupuncture versus physiotherapy | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, chronic, mixed, or unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Acupuncture versus mobilization | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, mixed, or unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [93], there was no significant difference between acupuncture and standard localized mobilization techniques at short- or intermediate-term posttreatment followup (no numerical data on mean scores were reported). |

| Disability (NPQ score) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [93], there was no significant difference between acupuncture and standard localized mobilization techniques at short- or intermediate-term posttreatment followup (no numerical data on mean scores were reported). | |

|

| |||

| Acupuncture versus usual care | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, mixed, or unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Disability (NPQ score) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [94], acupuncture was added to general practice care and showed no difference in disability (NPQ) compared to general practice care alone immediately posttreatment (22.73 ± 18.64 versus 25.72 ± 16.29, P > 0.05). |

|

| |||

| Acupuncture versus manipulation | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, mixed, or unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [24], there was no significant difference between acupuncture and spinal manipulation at short-term followup (mean VAS: 4.46 ± 3.11 versus 4.43 ± 2.51). |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Pain intensity score (mean % VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: no Directness: yes |

In one trial [69], acupuncture was better than manipulation in reducing pain intensity at short-term followup (50.0% versus 42.0%). In another trial [70], immediate posttreatment reduction in pain intensity was significantly greater in manipulation (VAS: 33.0%) versus acupuncture (VAS score % reduction not reported). |

| Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [69, 72], median pain intensity scores in the acupuncture and manipulation groups did not differ at intermediate-term followup (VAS median scores: 2.5 versus 2.8, P = NR). | |

| Disability score (NDI) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: yes Directness: yes |

Two trials demonstrated significant superiority of manipulation over acupuncture in improving neck disability. In the first trial [70], median NDI score reduction in neck disability immediately posttreatment was significantly greater in manipulation (−10.0, 95% CI: −14.0, −4.0) than acupuncture group (−6.0, 95% CI: −16.0, 2.0). In the second trial [69], the posttreatment NDI values were significantly more improved in manipulation (median: 22; range: 2–44) than acupuncture group (median: 30; range: 16–47); P value not reported. |

|

|

| |||

| Acupuncture versus massage | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, mixed, or unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [209], acupuncture was significantly better (VAS score scale: 0–100) compared to massage in a short-term posttreatment followup (mean VAS score change from baseline: 24.22 versus 7.89, P = 0.005). |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

*Precision in formal grading was applied only to pooled results.

VAS: visual analog scale; RMDQ: Roland-Morris disability scale; NHP: Nottingham health profile; MPQ: McGill pain questionnaire; PDI: pain disability index; SF: short form; NPQ: neck pain questionnaire; SF-PQ: short form pain questionnaire; PRI: pain rating index; PPI: present pain intensity; NA: not applicable; NDI: neck disability index.

3.6.1. Acupuncture versus Inactive Treatment

In one trial of subjects with unknown duration of myofascial neck pain [75], acupuncture was significantly better than no treatment in reducing pain intensity (McGill pain questionnaire) shortly after the end of treatment (mean change from baseline: −15.2 ± 13.3 versus −5.3 ± 8.7, P = 0.043). There was no evidence comparing acupuncture to no treatment in subjects with neck pain of acute/subacute, chronic, and mixed duration.

Two meta-analyses (Figure 6) indicated no significant difference between acupuncture and sham-acupuncture in subjects with chronic-specific (two trials; VAS score: 0.27, 95% CI: −0.60, 1.13) [77, 78] or nonspecific pain (three trials; VAS score: − 0.24, 95% CI: −1.20, 0.73) [80–82] for immediate posttreatment pain intensity. Similarly, one trial of subjects with mixed specific pain showed no significant difference between acupuncture and placebo in reducing pain intensity (VAS score) or improving disability immediately after treatment [88]. There was no evidence comparing acupuncture to placebo in subjects with acute/subacute duration of neck pain.

Figure 6.

Acupuncture versus placebo for chronic-specific and nonspecific neck pain (Pain intensity: Visual Analogue Scale).

3.6.2. Acupuncture versus Active Treatment

There were inconsistent results for immediate- or short-term posttreatment pain intensity between acupuncture and pain medication in subjects with chronic and unknown duration of pain (8 trials) [28, 69, 70, 87, 89–92]. For subjects with chronic nonspecific pain, acupuncture was significantly better in reducing pain than NSAIDs immediately after treatment [91]. Similarly, in two trials, acupuncture was significantly more effective than injection of Lidocaine in short-term followup for treatment of unknown nonspecific neck pain [28, 92]. In other five trials, there was no significant difference between acupuncture and pain medication [69, 70, 87, 89, 90].

There were inconsistent results for immediate- or short-term posttreatment pain intensity between acupuncture and spinal manipulation for chronic pain (3 trials) [24, 70, 72]. Immediate/short-term posttreatment disability score (NDI) was better in manipulation than acupuncture groups of subjects with chronic nonspecific pain (2 trials) [69, 70].

Acupuncture did not differ from mobilization [93] or laser therapy [95, 96] in short-term posttreatment pain intensity or disability (3 trials).

In one trial [76], acupuncture was significantly better than massage in reducing pain intensity at short-term posttreatment followup (mean VAS score change from baseline: 24.22 versus 7.89, P = 0.005).

3.7. Efficacy of Manipulation for Low-Back Pain

This section included 13 studies using manipulation alone [69, 70, 72, 97–108]. (Table 4 for efficacy results and evidence grading (Appendix B)). About 62% of studies were conducted in North America (USA and Canada), 15% in Australia, and the remaining 23% in Europe (United Kingdom, Italy), and (Egypt).

Table 4.

Summary of findings of spinal manipulation for low-back pain (only pain and functional outcomes).

| Duration and cause of pain | Outcomes | GRADE* | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manipulation versus no treatment | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute nonspecific | Pain intensity score (0 to 5) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [97], there was a significantly lower immediate posttreatment pain intensity in the manipulation group (change from 2.8 to 1.0; P = 0.03) compared to “no treatment” group (change from 2.0 to 2.1, P > 0.05). |

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mixed nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [98], manipulation showed significant reduction (from baseline) in immediate/short-term posttreatment pain intensity (VAS: 12.20 versus 10.40, P < 0.05), while the “no treatment” group did not experience significant reduction in pain intensity (P = 0.10). |

|

| |||

| Mixed specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic or Unknown (nonspecific and specific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Manipulation versus placebo | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Moderate

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: yes Directness: yes |

Four trials [97, 99, 101, 211] showed significant improvements for manipulation in reducing immediate or short-term posttreatment pain. For example, in one trial [211], manipulation was significantly superior to placebo at short-term followup (four-point VAS; P < 0.01). Intermediate-term posttreatment data of the same trial showed no significant difference between the groups. In another trial [101], manipulation showed significantly better immediate-term posttreatment pain intensity (percentage of pain-free subjects: 92.0% versus 25.0%, P < 0.01). |

| Oswestry Disability Index |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

One trial [99] showed no between-group differences in the immediate and short-term posttreatment follow-ups. | |

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: no Directness: yes |

In two trials [102, 211], manipulation was significantly better than placebo. In a third trial [103], the immediate posttreatment pain intensity improved more in the manipulation group (1.3 versus 0.7) and in the short-term posttreatment (2.3 versus0.6). There was a significant change within the manipulation group but not within the placebo group. The P value for between-group comparison was not reported and therefore the between-group significant difference was not assumed. |

| Oswestry Disability Index |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [102], manipulation was significantly better than placebo immediately posttreatment (9.5 ± 6.3 versus 15.5 ± 10.8, P = 0.012), but the difference in the short-term posttreatment was not statistically significant (10.6 ± 11.7 versus 14.0 ± 11.7, P = 0.41). | |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mixed nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

One trial [104] showed that immediate posttreatment improvement was numerically greater in the manipulation group (numerical data not reported, and statistical test results were not provided). |

|

| |||

| Mixed specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Manipulation versus pain medication | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

One trial showed a nonsignificant advantage of manipulation at the immediate posttreatment followup [211]. This advantage was not sustained at the short- and intermediate posttreatment followups (numerical data not reported, and statistical test results were not provided). |

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) Immediate posttreatment |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: yes Directness: yes |

Two trials [69, 70] showed significantly greater pain reductions with spinal manipulation. The median (IQR) pain intensity went from 5 (4 to 8) to 3 (0 to 7) (P = 0.005) with manipulation, and from 5 (3 to 8) to 5 (2 to 7) (P = 0.77) with medication [52]. In the other trial, the change was −2.5 (95% CI: −5.0, −21) in the manipulation group and +0.3 (95% CI: −1.0, 1.7) in the medication group [70]. |

| Pain intensity (subjective score: 5 = poor, 32 = excellent) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

One trial [211] showed that spinal manipulation was not significantly different from medication. Subjective score with manipulation were 2.6 and 4.3 in the short- and intermediate-term. Subjective score with medication were 2.2 and 4.0 in the short- and intermediate-term. (Statistical test results were not provided). |

|

| Oswestry Disability Index |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: yes Directness: yes |

Two trials [69, 70] showed significantly greater mean reduction in disability in the manipulation versus pain medication group immediately after treatment (50% [69] and 30.7% [70]). | |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mixed or unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Manipulation versus physiotherapy | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

One trial [211] showed better scores with manipulation at the immediate-, short- and intermediate posttreatment followups (Numerical data not reported, and statistical test results were not provided). |

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

One trial [211] showed better scores with physiotherapy versus manipulation at the immediate-, short- and intermediate posttreatment followups (numerical data not reported, and statistical test results were not provided). |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mixed nonspecific | Pain intensity score (11-point pain scale) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [105], no significant differences were found in short-term posttreatment effects between manipulation and physiotherapy (McKenzie technique based on diagnoses of derangement, dysfunction or postural syndromes). |

| Roland-Morris Disability score |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [105], there was no significant difference between manipulation and physiotherapy (McKenzie technique based on diagnoses of derangement, dysfunction or postural syndromes) in the short-term posttreatment effects. | |

|

| |||

| Mixed specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Manipulation versus usual care | |||

|

| |||

| Mixed nonspecific | Pain intensity score (100-mm VAS score) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Low Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [106], high or low velocity spinal manipulation was not significantly different from minimal conservative medical care. Mean VAS score difference between high velocity manipulation and usual care was 4.0 (95% CI: −4.0, 12.0), whereas this difference between low velocity manipulation and usual care was 5.8 (95% CI: −2.3 to 14.0). |

|

| |||

| Roland-Morris Disability score |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Low Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

One trial [106] showed that manipulation was significantly more effective than medical care alone in improving disability at immediate, short-, or intermediate-term posttreatment followup. The adjusted RMDQ mean change from baseline in the high and low velocity manipulation and medical care groups were 2.7 (95% CI: 2.0, 3.3), 2.9 (95% CI: 2.2, 3.6), and 1.6 (95% CI: 0.5, 2.8), respectively. | |

|

| |||

| Mixed specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Acute, chronic or unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Manipulation versus massage | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute nonspecific | Pain intensity score (100-mm VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [107], there was no significant difference between manipulation and massage immediately posttreatment (mean difference: −24.1 ± 27 and −17.2 ± 25.1, resp.). |

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Pain (duration of pain relief) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: no |

In one trial [108], manipulation was significantly better than massage immediately—and in the short-term after treatment. The mean (SE) duration of pain relief was 8.01 ± 2.02 with manipulation versus 2.94 ± 0.52 with massage. |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mixed or unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

*Precision in formal grading was applied only to pooled results.

VAS: visual analog scale; RMDQ: Roland-Morris disability scale; MPQ: McGill pain questionnaire; PDI: pain disability index; NPQ: neck pain questionnaire; NA: not applicable; ROB: risk of bias; RCT: randomized controlled trial.

3.7.1. Manipulation versus Inactive Treatment

In subjects with acute/subacute [97, 99–101, 109] and mixed duration [98, 104] nonspecific LBP, manipulation was significantly more effective than placebo [97, 99–101, 104, 109] or no treatment [97, 98] in reducing pain intensity immediately or in the short-term following treatment. There was no significant difference between manipulation and placebo in posttreatment pain disability. In subjects with chronic nonspecific LBP, manipulation was significantly more effective than placebo in reducing pain intensity (VAS score) immediately or short-term after the end of treatment [100, 102, 103].

3.7.2. Manipulation versus Active Treatment

Manipulation was significantly better (in immediate posttreatment pain) or no different (in intermediate-term posttreatment pain) than pain medication in improving pain intensity [69, 70]. Manipulation did not differ from pain medication in reducing pain intensity at short- and intermediate-term followup after treatment [100].

In older subjects with mixed LBP duration, spinal manipulation was significantly better than medical care (exercise, bed rest, analgesics) in improving immediate and short-term posttreatment disability (Oswestry), although no significant difference could be found in pain intensity [106].

In two large trials [110, 111], subjects receiving combination of manipulation and exercise or manipulation and best care by general practitioner (analgesics or muscle relaxants) improved in pain and disability compared to subjects with no spinal manipulation treatment.

3.8. Efficacy of Manipulation for Neck Pain

This section included 12 trials (Table 5 for efficacy results and evidence grading (Appendix B)) [69, 70, 72, 112–121]. About half of the studies were conducted in North America (USA and Canada), 16% in Europe (Germany, Spain) and the remaining 34% of the studies in Australia.

Table 5.

Summary of findings of manipulation for neck pain (only pain and functional outcomes).

| Duration and cause of pain | Outcomes | GRADE* | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manipulation versus no treatment | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, chronic, and mixed, (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Unknown specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Unknown nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [112], there was no significant difference between manipulation and “no treatment” groups in immediate-term posttreatment pain intensity. |

|

| |||

| Manipulation versus placebo | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: yes Directness: yes |

In two trials [113, 114], manipulation was significantly more effective than placebo immediately after treatment. In the first trial [113] ipsilateral manipulation (but not contralateral; P = 0.93) was significantly better than placebo ultrasound (mean VAS score: 23.6 ± 18.6 versus 46.5 ± 21.8, P = 0.001). In the other trial [114], manipulation was significantly better than placebo (light hand placement on the side of neck without application of any side-different pressure or tension) (numerical data not reported; P = 0.01). |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) | Moderate Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: yes Directness: yes |

In two studies [115, 116], manipulation techniques were significantly better than placebo immediately after treatment. In the first trial [115] cervical osteopathy was better than placebo (sham ultrasound). In the second trial [116] a single thoracic manipulation was significantly better than placebo (hand manoeuvre without high velocity thrust). |

| Disability score (NDI) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [116] a single thoracic manipulation was significantly better than placebo (hand manoeuvre without high velocity thrust). | |

|

| |||

| Mixed (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Unknown specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Unknown nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [117], manipulation was significantly better than placebo immediately after treatment (P < 0.001). The mean VAS reductions in manipulation and placebo groups were 15.5 (95% CI: 11.8, 19.2) and 4.2 (95% CI: 1.9, 6.6), respectively. |

|

| |||

| Manipulation versus pain medication | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, mixed, or unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: no Directness: yes |

In one trial [118] although both manipulation and medication (Diazepam) groups improved, there was no between-group significant difference at short-term followup after treatment (5.0 ± 3.2 versus 1.8 ± 3.1, P = 0.20). In two other trials [69, 70], manipulation was significantly better than medication (e.g., NSAIDs, Celebrex, Vioxx, Paracetamol) at immediate/short-term followup after treatment. In one of these trials [69] the proportion of pain-free patients after the treatment was significantly greater in the manipulation group compared to the medication group (27.3% versus 5.0%, P = 0.05). |

| Disability score (NDI) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: yes Directness: yes |

In two other trials [69, 70], manipulation was significantly better than medication (e.g., NSAIDs, Celebrex, Vioxx, Paracetamol) at immediate/short-term followup after treatment. In one trial, [69] the median (IQR) values for manipulation and medication groups were 22 [26, 30–33, 35, 36, 41, 45, 47–49, 52–66, 66, 68–72, 75, 77–83, 85, 208–210] versus 42 [26, 27, 30, 33, 36, 41, 47, 49, 66–72, 75, 77–83, 85–91, 208–210], respectively. No between-group P value was reported. In the other trial [70] the median (95% CI) changes (from baseline) in manipulation and medication groups were −10.00 (95% CI: −14.0, −4.0) versus 0.0 (95% CI: −14.0, 2.7), respectively (P < 0.001). | |

|

| |||

| Manipulation versus physiotherapy | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, chronic, mixed, or unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Manipulation versus mobilization | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [114], there was no statistically significant difference between manipulation and mobilization immediately after treatment (P = 0.16; no other numerical data were reported). |

|

| |||

| Mixed, specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mixed, nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS)—immediately after treatment |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: yes Directness: yes |

Two trials reported comparison of pain intensity between manipulation and mobilization at immediate followup [119, 120]. In the first trial [120] spinal manipulation was significantly better than mobilization (P < 0.001). The mean VAS reductions in manipulation and mobilization groups were 3.5 (95% CI: 3.1, 3.9) and 0.4 (95% CI: 0.2, 0.5), respectively. In the second trial [119], manipulation was significantly better (but at borderline due probably to low study power) than mobilization (mean reduction on NRS-101: −17.3 ± 19.5 versus −10.5 ± 14.8, P = 0.05). |

| Pain intensity score (VAS)—intermediate-term after treatment |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [121] the intermediate-term posttreatment differences between the manipulation and mobilization groups were clinically negligible and statistically nonsignificant (NRS-11: −0.02, 95% CI: −0.69, 0.65) and disability (NDI: 0.46, 95% CI: −0.89, 1.82). | |

| Disability (NDI score) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (only 1 trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [121] the intermediate-term posttreatment differences between the manipulation and mobilization groups were clinically negligible and statistically nonsignificant (mean difference in NDI score: 0.46, 95% CI: −0.89, 1.82). | |

|

| |||

| Chronic or unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Manipulation versus usual care | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, chronic, mixed, or unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Manipulation versus acupuncture (see Table 3 for acupuncture for neck pain) | |||

|

| |||

| Manipulation versus massage | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, chronic, mixed, or unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Manipulation versus exercise | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, chronic, mixed, or unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

*Precision in formal grading was applied only to pooled results.

VAS: visual analog scale; RMDQ: Roland-Morris disability scale; NHP: Nottingham health profile; MPQ: McGill pain questionnaire; PDI: pain disability index; SF: short form; NPQ: neck pain questionnaire; SF-PQ: short form pain questionnaire; PRI: pain rating index; PPI: present pain intensity; NA: not applicable; NDI: neck disability index; IQR: interquartile range.

3.8.1. Manipulation versus Inactive Treatment

There was no significant difference in reducing pain intensity between manipulation and “no treatment” groups in immediate-term posttreatment in subjects with unknown nonspecific pain (1 trial) [112].

Subjects with acute, subacute, chronic or unknown neck pain receiving manipulation had significantly better posttreatment pain (4 trials) [113–116] and disability (1 trial) [116] compared to those taking placebo.

3.8.2. Manipulation versus Active Treatment

In two trials [69, 70], manipulation was significantly better than medication (e.g., NSAIDs, Celebrex, Vioxx, Paracetamol) in reducing pain intensity and improving disability score at immediate/short-term followup.

In subjects with acute/subacute nonspecific pain there was no statistically significant difference between manipulation and mobilization immediately after treatment (1 trial) [114]. In subjects with mixed duration nonspecific neck pain, manipulation was statistically significantly more effective than mobilization in reducing pain immediately after treatment (2 trials) [119, 120]. In one trail [121], there were no clinically or statistically significant differences between manipulation and mobilization in reducing pain or improving disability at intermediate term followup [121].

3.9. Efficacy of Mobilization for Low-Back Pain

This section included 13 trials (Table 6 for efficacy results and evidence grading (Appendix B)) [25, 34, 122–134]. About 30% of the trials were conducted in the US, 54% in Europe (Finland, United Kingdom, Sweden, Spain), and 16% in Australia, Thailand, and China. Two studies were published in either Spanish [34] or Chinese [25].

Table 6.

Summary of findings of spinal mobilization for low-back pain (only pain and functional outcomes).

| Duration and cause of pain | Outcomes | GRADE* | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobilization versus no treatment | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute, nonspecific | Pain intensity (MPQ) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [122] mobilization group had significantly lower pain intensity immediately posttreatment (P = 0.048). No further numerical data was provided. |

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [34] mobilization (Kaltenborn's wedge assisted posteroanterior) was significantly superior to “no treatment.” Immediate posttreatment mean pain score values were 33.40 for mobilization versus 49.77 for “no treatment” (P < 0.001). |

| Roland-Morris Disability score |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [34] mobilization (Kaltenborn's wedge assisted posteroanterior) was significantly superior to “no treatment.” Immediate posttreatment mean pain score values were 7.69 for mobilization versus 10.64 for “no treatment” (P < 0.003). | |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | Oswestry Disability Index |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

One trial [123] showed no difference between-groups immediately posttreatment in disability index: 5.57 (2.38) with mobilization and 2.19 (1.54) with “no treatment”. |

|

| |||

| Mixed nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [124] mobilization did not significantly differ from “no treatment” immediately after treatment. The mean difference in pain (overall %) was −24.7 with mobilization and −11.1 with no treatment (F = 2.63, P > 0.05). |

|

| |||

| Mixed specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mobilization versus placebo | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute nonspecific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute specific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial, [125, 126] of subjects with sacroiliac joint dysfunction (96% women), there was no statistically significant difference immediately posttreatment between mobilization and placebo (no numerical data was reported). |

|

| |||

| Chronic (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mixed nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial, [127] mobilization did not significantly differ from placebo in reducing immediate or short-term posttreatment pain intensity. The mean (SD) pain intensity immediately posttreatment was 4.2 (2.5) with mobilization and 4.3 (2.2) with placebo (P = 0.8). |

|

| |||

| Mixed specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mobilization versus physiotherapy | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: no Directness: yes |

The pooled estimate of 2 trials showed a significant benefit of mobilization immediately posttreatment (mean difference in VAS score: −0.50, 95% CI: −0.72, −0.28) [128–130]. |

| Oswestry Disability Index | Moderate Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: yes Directness: yes |

The pooled estimate of 2 trials [128–130] showed a significant benefit of mobilization immediately posttreatment (mean difference in disability score: −4.93, 95% CI: −5.91, −3.96). | |

|

| |||

| Chronic specific | Oswestry Disability Index |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

One trial [123] showed no difference between-groups immediately posttreatment in disability index: 5.57 (2.38) with mobilization and 2.55 (1.03) with physiotherapy (physical modalities including exercise). |

|

| |||

| Mixed nonspecific | Oswestry Disability Index |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [131] there was no difference between mobilization and physiotherapy in disability. Mean change (95% CI) in mobilization group at immediate-, short-term, intermediate-term and long-term posttreatment were 7.0 (3.4, 10.2), 5.1 (1.7, 8.4), 9.4 (6.7, 12.1) and 8.4 (5.2, 11.6), respectively. Mean change (95% CI) in the physiotherapy group at immediate-, short-term, intermediate-term and long-term posttreatment were 2.0 (−1.1, 5.1), 4.0 (1.3, 6.7), 4.7 (1.5, 7.9), and 4.4 (1.2, 7.6), respectively. The between-group difference was statistically significant at intermediate and long-term posttreatment followups only. |

|

| |||

| Mixed specific | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mobilization versus manipulation | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute (nonspecific) | Roland-Morris Disability score |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: Medium Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial, [132] the manipulation group had a significantly better disability score compared to the mobilization group immediately posttreatment. The mean (SD) disability scores were 9.1 (5.3) with manipulation and 3.9 (4.3) with mobilization (P < 0.04). |

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute (specific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic, mixed, unknown (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mobilization versus massage | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic (nonspecific) | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [133], short-term posttreatment pain intensity was slightly but significantly greater in the mobilization group compared to the massage group (3.36 ± 0.25 versus 2.48 ± 0.25, P = 0.017). |

|

| |||

| Chronic (specific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mixed (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Unknown (nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Unknown (specific) | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |

In one trial [25] of subjects with disc protrusion, there was no statistically significant difference in posttreatment pain intensity between the groups (5.59 ± 0.80 versus 4.71 ± 0.52, P > 0.05). |

|

| |||

| Mobilization versus exercise | |||

|

| |||

| Acute/subacute (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Chronic (specific, nonspecific) | NA |

Insufficient

No trial |

NA |

|

| |||

| Mixed nonspecific | Pain intensity score (VAS) |

Low

Design: RCT ROB: High Consistency: NA (one trial) Directness: yes |