Abstract

Background

While some studies have reported detection of oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) in colorectal tumors, others have not.

Methods

We examined the association between oncogenic HPV infection and colorectal polyps in a case-control study of individuals with colorectal adenomas (n=167), hyperplastic polyps (n=87), and polyp-free controls (n=250). We performed real-time PCR for HPV-16 /18 DNA, and SPF PCR covering 43 HPV types, on lesional and normal colorectal tissue samples. Plasma antibodies for oncogenic HPV types were assessed via a bead-based multiplex Luminex assay.

Results

HPV DNA was not found in any of the 609 successfully assayed colorectal tissue samples from adenomas, hyperplastic polyps, normal biopsies adjacent to polyps, or normal biopsies of the rectum of disease-free controls. Also, there was no association between HPV seropositivity for all oncogenic HPV types combined, for either polyp type, and for men or women. When analyses were restricted to participants without a previous history of polyps, among men [adenomas (n=31), hyperplastic polyps (n=28), and controls (n=68)], there was an association between seropositivity and hyperplastic polyps when all oncogenic HPV types were combined (odds ratio=3.0; 95% confidence interval: 1.1–7.9).

Conclusions

Overall, our findings do not support an etiologic relationship between HPV and colorectal adenomas or hyperplastic polyps; however, our finding suggesting an association between HPV seropositivity and hyperplastic polyps in men may warrant further investigations.

Impact

After stringent controls for contamination and three methods to assess HPV infection, we report no evidence for HPV in the etiology of colorectal neoplasia for either men or women.

Keywords: HPV, colorectal adenomas, hyperplastic polyps, DNA, antibodies

Introduction

Oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is a necessary cause of cervical cancer and is strongly associated with other epithelial malignancies, such as oropharyngeal, penile, vaginal, vulvar, and anal cancers (1–3). HPV DNA 16 and other oncogenic types are present in precursor lesions of HPV-related cancers, as well as the carcinomas themselves (4). In all of the known HPV-related carcinomas, the most common types detected are types -16 and -18, which cause over 70% of HPV-related carcinomas (5–8).

Although 100% of cervical cancer is attributable to HPV, the proportion of other anogenital cancers that are etiologically connected to HPV varies (2). In those cancers showing associations with HPV but with less than 100% attributable to HPV, there are most likely multiple pathways leading to cancer, one (or more) of which involves HPV infection.

Because colorectal cancer originates in epithelial cells and the anal canal, a site known to be associated with HPV-related malignancies (1), leads to the rectum and colon, more than one dozen studies have considered whether colorectal neoplastic tissue contains HPV DNA (9–22). Results from these studies have been inconsistent, with some studies reporting 14–84% of colorectal neoplasia positive for HPV DNA (9–17), and others detecting no HPV DNA in colorectal cancers (18–22) or adenomatous polyps (19, 22). Therefore, the association between HPV and colorectal neoplasia is unclear.

Colorectal cancer is a heterogeneous, multifactoral disease with several distinct causal pathways (23). Also, recent evidence supports the hypothesis that specific precursor lesions are associated with different pathways (24). Colorectal adenomatous polyps (adenomas) are well established precursor lesions; however, only a small proportion of these lesions will progress to cancer (25). The adenoma-carcinoma pathway usually involves APC mutation as an early event, followed by an accumulation of other mutations and accompanying morphologic changes (26). Hyperplastic polyps, generally considered innocuous lesions, may in some instances progress to cancer along a separate pathway, termed “the serrated pathway” (27, 28). This pathway is hypothesized to involve aberrant methylation and BRAF mutation (29, 30). Most reported risk factors for hyperplastic polyps are similar to risk factors for adenomas, such as increased risks for male sex and high alcohol consumption and decreased risk for post-menopausal hormone use, calcium intake, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs) drug use (31, 32). However, hyperplastic polyps tend to occur at a younger age than adenomas (31) and have a much stronger association with cigarette smoking (31, 33, 34).

To date, no other studies have examined hyperplastic polyps in relation to oncogenic HPV infection. Also, none of the previous studies used quantitative methods to assess the viral copy number in colorectal case and control tissue samples. Precursor lesions in HPV-related anal and cervical cancer have a higher viral copy number than normal adjacent tissue and normal anal or cervical tissue from disease-free controls (35, 36). If HPV were important in the etiology of colorectal neoplasia, one would expect to observe similarly increased viral copy number specifically in the disease tissue and not in normal tissue. Finally, most of the previous studies have not compared HPV seropositivity (a marker of past infection) in colorectal neoplasia cases to disease-free controls. This is important because antibody analyses are less susceptible to contamination than DNA analyses. Also, because it takes an average of 8–11 months post-infection for HPV-16 antibodies to develop (37, 38), antibody analyses would be better than DNA analyses at differentiating between very recent infection (which would be unlikely to have caused clinically detectable levels of cellular proliferation) and HPV infection occurring further back in time. We conducted a case-control study of the association between oncogenic HPV infection and adenomas and hyperplastic polyps using real-time PCR for HPV-16 and -18, as well as an assay for serologic HPV antibodies.

Methods

Study Population

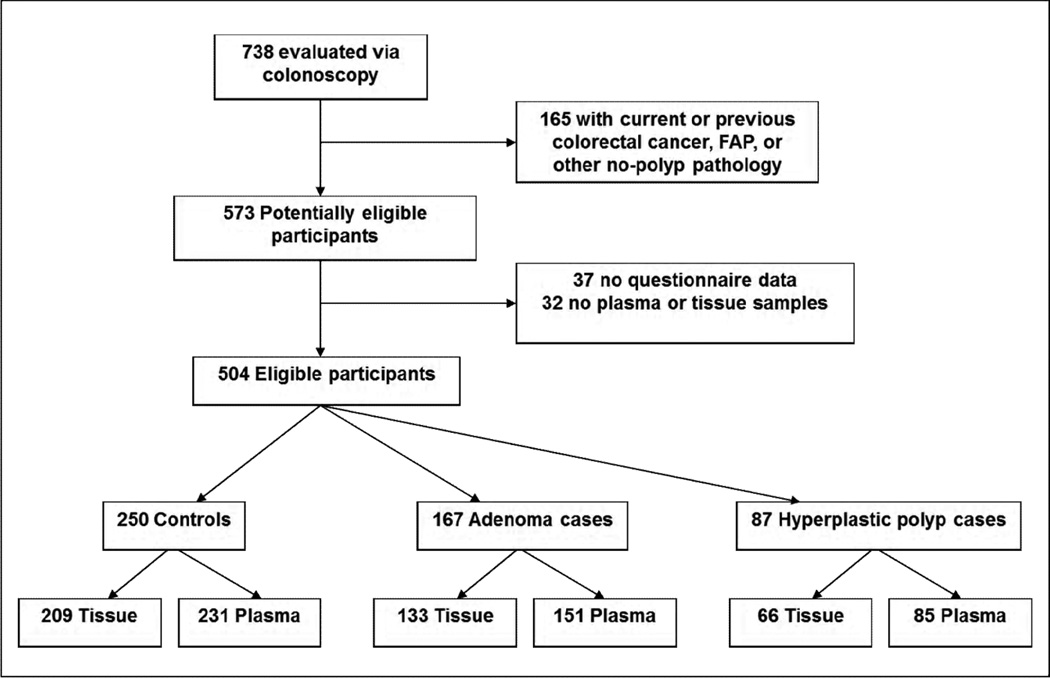

Participants were 30–79 year-old members of Group Health (GH), a large integrated health care system in Washington State, who received a colonoscopy for any indication from September 1998 to March 2003. Prior to colonoscopy, a sequential sample of individuals were invited to take part in a study of colorectal cancer screening markers (39, 40). All study protocols were approved by Institutional Review Boards at GH and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC). Eligibility was limited to participants with at least one prevalent adenoma or hyperplastic polyp at the index colonoscopy and for comparison, participants with disease-free colons and rectums (See “Case-control classification”, below); additionally, among these, only those with questionnaire data and either a blood sample, a tissue sample, or both available for analyses were included in the present study. Of the 738 participants in the parent study, we excluded those who had a self-reported history of colorectal cancer, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), or other non-polyp colorectal pathologies (n=165). Thirty-seven additional participants were excluded due to missing or incomplete questionnaire data, which precluded the ascertainment of colorectal disease history, and 32 were excluded because they did not have blood or tissue samples available for analysis. Thus, 504 participants were eligible (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Case-Control Classification

For polyp cases, standardized pathology reviews were completed, and medical records reviewed to ascertain the size and anatomic site of each polyp. If a participant had at least one of the following polyps, he/she was classified an adenoma case: tubular adenoma, tubulovillous adenoma, or villous adenoma. Cases with microvesicular hyperplastic polyps, goblet cell hyperplastic polyps, serrated polyps, or sessile serrated polyps and no adenomas were classified as hyperplastic polyp cases (41). Controls were participants who had no colorectal pathologies identified during the index colonoscopy. The eligible study population consisted of 167 adenoma cases, 87 hyperplastic polyp cases, and 250 controls (Figure 1).

Data Collection

Study participants completed a self-administered questionnaire, eliciting the following information: demographic characteristics, height, weight, history of colorectal polyps, cancer history, lifetime alcohol consumption, smoking history, aspirin use, and, for women only, reproductive history and hormone use. Over 95% of participants completed the forms prior to colonoscopy, thus minimizing the possibility of recall differences by diagnosis.

Prior to colonoscopy, an EDTA (ethylene-diamine tetra-acetic acid) tube of blood was collected, processed within 20 hours, and stored at −80° Celsius.

During colonoscopy, tissue samples from polyps and other pathologies (e.g., cancer, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease) were collected for diagnostic review. In addition, up to 8 peri-lesional biopsies were collected from the normal mucosa adjacent to polyps, and up to 8 normal-mucosa biopsies were sampled from the rectum of all participants, regardless of clinical findings. Tissues were processed and stored in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks.

Tissue Sample Selection and Preparation

We chose FFPE polyp tissue blocks for analysis if a polyp was at least 3mm in size based on clinical diagnosis, and contained at least 50% lesional tissue according to the H&E slide. Of the 167 eligible adenoma cases, 96 cases had one block and 37 cases had multiple adenomatous polyp blocks that fit these criteria, resulting in a total of 177 adenomatous tissue samples for analyses. For hyperplastic polyp tissue, 66 of the 87 hyperplastic polyp cases had eligible blocks (50 cases with 1 block and 16 cases with multiple blocks) for a total of 84 hyperplastic polyp tissue samples from cases with only hyperplastic polyps. An additional 25 hyperplastic polyp tissue samples were included from 25 cases that had both adenomatous and hyperplastic polyps.

As noted, two types of clinically normal tissue were sampled; 1) normal tissue adjacent to eligible polyps in cases, and 2) tissue from the rectum of polyp-free controls. Of 177 adenomatous polyps, 60 had normal adjacent tissue available for comparison; 62 of the 109 hyperplastic polyps had normal adjacent tissue available. There were normal rectal tissue samples from 209 polyp-free controls. All lesional and normal tissue samples were labeled with identification numbers that did not reveal the source of the tissue or diagnosis.

In preparation for sectioning, tissue samples were arranged in batches containing lesional-tissue blocks interspersed with clinically normal-tissue blocks. Ten 10-micron sections were cut from each block and placed directly into two separate 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes. All blocks were sectioned using the following protocol to limit contamination: 1) prior to beginning sectioning and between each block, the microtome, forceps, and work bench were wiped down with RNase, followed by 1% bleach, then 70% ETOH; 2) a new microtome blade, new forceps, and fresh gloves were used for each block; and 3) a 5-micron section was cut off the front of each block and discarded, prior to cutting any sections used for assays. In addition to these procedures, every 11th block sectioned was comprised of mouse heart tissue which served as sentinels for potential contamination.

DNA Extraction

Tissue sample tubes were kept at room temperature until DNA extraction. We used QIAamp DNA FFPE tissue kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) for DNA extraction and followed the manufacturer’s protocol with modifications to optimize DNA yield. Briefly, 1mL of xylene was added to samples to remove the paraffin, followed by 1mL of 100% ethanol; samples were then incubated at 55°C in a proteinase K solution overnight (16–18hrs). After samples were completely lysed, a conditioning buffer was added, and samples were incubated for 10 minutes at 70°C; they were then transferred to silica-based QIAamp MinElute columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) which selectively bind nucleic acids. DNA was eluted from the columns with 55 µL of 70°C heated buffer solution, quantified using Picogreen (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and stored at −20°C until HPV DNA testing.

Real-time PCR for HPV-16 and -18 DNA

We performed a multiplex real-time PCR assay using TaqMan (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) probes for HPV-16 and -18, based on the methods by Schmitz, et al (42), to detect HPV DNA in colorectal lesional and non-lesional tissue from the above described FFPE samples. Specific primers and probes for this assay were previously reported (42) and were designed to amplify the HPV E6 or E7 genes and to have small product sizes: 128 bp for HPV-16 and 124 bp for HPV-18. The β-globin gene, with a product size of 110 bp, was amplified in the same reaction as HPV types -16 and -18 to control for DNA quality and to determine the concentration of HPV-16 and -18 DNA relative to the number of cells in each sample.

Each probe was labeled with a different fluorescent dye: 5′-Fam/MGB-3′ for HPV-16, 5′-NED/MGB-3′ for HPV-18, and 5′-VIC /MGB-3′ for β-globin. The reaction used 2µL DNA, 10µL TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 10 pmol of each primer and 1–5 pmol of each probe. Forty-five cycles were run at 94°C for 15s, 50°C for 20s, and 60°C for 40s. Heart tissue DNA (HPV-negative), SiHa cell line DNA (HPV-16 positive), and C4-1 cell line DNA (HPV-18 positive) were used for quality control and included in each run. Each sample was run in triplicate, and the mean cycle threshold (CT) was recorded for β-globin, HPV-16, and HPV-18.

SPF PCR with Southern blot hybridization

We used SPF PCR primers and Southern blot hybridization to verify results of the real-time PCR for HPV-16 and -18 and to test for additional HPV types in all rectal adenoma and hyperplastic polyp tissue samples (n=99) and in normal rectal tissue from a subset of randomly selected controls (n=99). These primers, previously described (43), amplify a 65 bp sequence in the L1 open reading frame and can be used to detect 43 different types of HPV. PCR amplification, HPV DNA detection, and Southern blot hybridization were performed as described in Kleter, et al (43).

HPV antibody testing

Of 167 adenoma cases, 151 had blood samples available for HPV antibody analysis; of 87 hyperplastic polyp cases, 85 similarly donated a blood sample, and of 250 controls, 231 donated a blood sample (Figure 1). Plasma samples were tested using a multiplex Luminex assay as described in Waterboer, et al (44). Briefly, we used 10 distinct bead sets, each carrying a specific GST-HPV L1 antigen to one of the following oncogenic types: type 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 52, 58, or 68. In addition, we used a bead set with antigens to BK virus, a ubiquitous virus that the vast majority of the general population has antibodies to, and a bead set without antigens as quality control measures. Two microliters of plasma were mixed and incubated with the beads (final dilution of plasma 1:100). The beads were differentiated using a Luminex analyzer, and bound antibodies detected and quantified using fluorescent reagents. The output for each HPV type is the median fluorescent intensity (MFI), a measure of the amount of antibody bound to the bead.

Statistical analysis

Seropositivity was determined using sex-specific cutpoints from a separate population of healthy men and women in the Puget Sound region with only 1 lifetime sex partner; we used cutpoints equal to the mean MFI value plus 2 standard deviations for each HPV type. Individuals with MFI values above the cutpoint for a specific HPV-type were considered positive for that particular HPV type. Also, we included both a variable for seropositivity to types -16 or -18 and a variable for seropositivity to any of the HPV types tested. We performed multivariable polytomous regression to estimate the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) comparing HPV seropositivity in colorectal adenomas and hyperplastic polyp cases to controls using STATA (version 11.0, 2009, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Regression models were adjusted for age, race, smoking status (never, former, current), education, body mass index (BMI), and usual alcohol consumption (drinks/week), and stratified by sex. We tested for an interaction between HPV seropositivity and sex using a cross-product term and the likelihood ratio test.

If HPV were associated with polyp formation, the presently polyp-free controls that have had polyps in the past may have a higher prevalence of seropositivity than those without previous polyps, and this could attenuate possible associations. Similarly, because colorectal neoplasia is multifactoral, cases with current polyps that have had previous polyps may be at higher risk for polyp formation irrespective of HPV-status (i.e. possible genetic susceptibility to colorectal neoplasia). Thus, a priori, our analysis plan included regression analyses restricting the entire study population to participants without a previous history of colorectal polyps.

We calculated prevalence estimates for HPV-16 or -18 DNA in colorectal adenomatous polyps, colorectal hyperplastic polyps, and in normal tissue samples from the rectum of polyp-free controls.

Results

Table 1 displays selected characteristics of the study population by case-control status. Compared to controls, adenoma cases tended to be older, were more likely to be male, had higher alcohol consumption, and were more likely to have a previous history of polyps (p-value <0.05). Hyperplastic polyp cases were more likely to have BMI ≥30, and to have a previous history of polyps compared to controls (p-value <0.05).

Table 1.

Characteristics of controls, adenoma cases, and hyperplastic polyp cases: Group Health members undergoing colonoscopy 1998–2003.

| Characteristic | Controls (n=250) N (%) |

Adenomas (n=167) N (%) |

P-value* | Hyperplastic polyps (n=87) N (%) |

P-value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| 30–49 | 54 (22) | 19 (11) | 11 (13) | ||

| 50–59 | 88 (35) | 45 (27) | 28 (32) | ||

| 60–69 | 57 (23) | 58 (35) | 29 (33) | ||

| 70–79 | 51 (20) | 45 (27) | <0.01 | 19 (22) | 0.13 |

| Men | 99 (40) | 84 (50) | 0.03 | 41 (47) | 0.22 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Caucasian | 221 (88) | 151 (90) | 76 (87) | ||

| African American | 8 (3) | 3 (2) | 4 (5) | ||

| Asian American | 10 (4) | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | ||

| Hispanic | 2 (1) | 5 (3) | 4 (5) | ||

| Other | 9 (4) | 3 (2) | 0.41 | 2 (2) | 0.18 |

| Cigarette smoking status | |||||

| Never | 108 (43) | 68 (41) | 26 (30) | ||

| Former | 119 (48) | 86 (51) | 51 (59) | ||

| Current | 22 (9) | 13 (8) | 0.75 | 10 (11) | 0.09 |

| Education | |||||

| High school graduate or less | 31(12) | 24 (14) | 13 (15) | ||

| Some college/vocational school | 70 (28) | 57 (34) | 29 (33) | ||

| College graduate | 61 (24) | 26 (16) | 19 (22) | ||

| Post-college graduate school | 88 (35) | 60 (36) | 0.15 | 26 (30) | 0.66 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||

| <25 | 90 (36) | 53 (32) | 23 (26) | ||

| 25–29.9 | 100 (40) | 70 (42) | 31 (36) | ||

| ≥30 | 58 (23) | 43 (26) | 0.77 | 33 (38) | 0.05 |

| Alcohol consumption (drinks/wk) | |||||

| 0 | 51 (20) | 42 (25) | 21 (24) | ||

| 1–7 | 174 (70) | 96 (57) | 56 (64) | ||

| 8–14 | 19 (8) | 16 (10) | 5 (6) | ||

| >14 | 6 (2) | 13 (8) | 0.02 | 5 (6) | 0.36 |

| History of colorectal polyps | 51 (20) | 90 (54) | <0.01 | 35 (40) | <0.01 |

Chi-square p-value comparing adenoma cases to controls

Chi-square p-value comparing hyperplastic polyp cases to controls

HPV DNA results

We tested a total of 617 colorectal tissue samples from 408 different study participants for the presence of HPV-16 and -18 DNA using real-time PCR. Based on standard curves of the positive controls in each plate, if the β-globin CT was lower than the threshold needed to detect a positive HPV-16 or -18 signal, the sample was considered to have insufficient DNA quantity or quality for HPV-16 and -18 DNA detection with this assay. Among the 617 samples tested, 8 samples failed the assay based on poor β-globin CT values; thus, 99% of samples had sufficient DNA quantity and quality to detect HPV-16 and -18 if either type were present in the sample. Despite successful detection of HPV-16 and -18 in each of the respective positive quality control samples, none of the 609 successfully assayed study samples was positive for HPV-16 or -18 DNA.

In addition to real time-PCR for HPV-16 and -18, we conducted a PCR assay using SPF primers on 198 rectal tissue samples, of which 99 were either adenomatous or hyperplastic polyp tissue samples, and 99 were normal tissue samples from disease-free controls. For this assay, the failure rate was 4% (failures were defined by blank wells, indicating insufficient quality or quantity of DNA). For the remaining 190 samples that were successfully assayed, no HPV DNA was detected.

HPV antibody results

The distribution of MFI values for each HPV type differed between men and women, with women having higher mean values. For example, for HPV-16, the mean MFI among women was 1461 (standard deviation (SD) =4576), and among men it was 942 (SD=4827) (data not shown). The finding of higher HPV antibody levels in women is consistent with other HPV-antibody analyses (45, 46), and is the rationale for setting sex-specific cutoffs for HPV seropositivity. Also, as previously mentioned, all analyses were stratified by sex, because previous studies have reported stronger associations between HPV seropositivity and anal cancer in men than in women (47, 48).

There was no association between HPV seropositivity for all types combined, and either type of polyp, for either men or women in the full study population (Table 2). Among women, the adjusted OR for the association between HPV seropositivity to any of the HPV types and adenomas was 0.78 (95% CI, 0.43–1.41), and among men, it was 1.02 (95% CI, 0.48–2.16). For hyperplastic polyps, the adjusted OR in women was 0.88 (95% CI, 0.43–1.80), and in men it was 1.44 (95% CI, 0.61–3.41).

Table 2.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals comparing HPV seropositivity in adenoma and hyperplastic polyp cases to controls, stratified by sex: Group Health members, 1998–2003.

| Women (N=261) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (n=138) |

Adenomas (n=78) |

Hyperplastic Polyps (n=45) |

|||||

| N Pos (%) | N Pos (%) | Crude OR | Adjusted* OR | N Pos (%) | Crude OR | Adjusted* OR | |

| Any type | 61 (46) | 29 (37) | 0.68 (0.39–1.21) | 0.78 (0.43–1.41) | 18 (40) | 0.77 (0.39–1.53) | 0.88 (0.43–1.80) |

| HPV 16 | 35 (25) | 11 (14) | 0.48 (0.23–1.02) | 0.58 (0.27–1.24) | 12 (27) | 1.07 (0.50–2.30) | 1.32 (0.59–2.96) |

| HPV 18 | 18 (13) | 5 (6) | 0.46 (0.16–1.28) | 0.60 (0.21–1.75) | 0 (0) | 0 (0–0.65) | N/A† |

| HPV 16 or 18 | 43 (31) | 15 (19) | 0.53 (0.27–1.03) | 0.63 (0.31–1.26) | 12 (27) | 0.80 (0.37–1.71) | 0.97 (0.44–2.13) |

| HPV 31 | 18 (13) | 8 (10) | 0.76 (0.31–1.84) | 0.90 (0.36–2.25) | 3 (7) | 0.48 (0.13–1.70) | 0.65 (0.18–2.40) |

| HPV 33 | 15 (11) | 3 (4) | 0.33 (0.09–1.17) | 0.31 (0.09–1.14) | 2 (4) | 0.38 (0.08–1.74) | 0.31 (0.06–1.42) |

| HPV 35 | 9 (7) | 5 (6) | 0.98 (0.32–3.04) | 1.14 (0.35–3.74) | 3 (7) | 1.02 (0.26–3.96) | 1.31 (0.31–5.47) |

| HPV 39 | 6 (4) | 1 (1) | 0.29 (0.03–2.42) | 0.41 (0.05–3.71) | 1 (2) | 0.50 (0.06–4.27) | 0.86 (0.09–8.01) |

| HPV 45 | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 0.59 (0.06–5.72) | 0.57 (0.06–5.72) | 0 (0) | 0 (0–4.38) | N/A† |

| HPV 52 | 8 (6) | 2 (3) | 0.43 (0.09–2.07) | 0.42 (0.08–2.06) | 1 (2) | 0.37 (0.04–3.04) | 0.41 (0.05–3.50) |

| HPV 58 | 9 (7) | 5 (6) | 0.98 (0.32–3.04) | 1.05 (0.32–3.45) | 0 (0) | 0 (0–1.42) | N/A† |

| HPV 68 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0–3.56) | N/A† | 0 (0) | 0 (0–6.71) | N/A† |

| Men (N=206) | |||||||

|

Controls (n=93) |

Adenomas (n=73) |

Hyperplastic Polyps (n=40) |

|||||

| N Pos (%) | N Pos (%) | Crude OR | Adjusted* OR | N Pos (%) | Crude OR | Adjusted* OR | |

| Any type | 26 (28) | 20 (28) | 0.97 (0.49–1.93) | 1.02 (0.48–2.16) | 14 (35) | 1.39 (0.63–3.06) | 1.44 (0.61–3.41) |

| HPV 16 | 12 (13) | 10 (14) | 1.07 (0.43–2.64) | 1.01 (0.39–2.59) | 6 (15) | 1.19 (0.41–3.43) | 1.22 (0.40–3.66) |

| HPV 18 | 3 (3) | 2 (3) | 0.84 (0.13–5.20) | 0.87 (0.13–5.75) | 4 (10) | 3.33 (0.71–15.64) | 3.19 (0.63–16.28) |

| HPV 16 or 18 | 13 (14) | 12 (16) | 1.21 (0.52–2.84) | 1.20 (0.49–2.95) | 7 (18) | 1.31 (0.48–3.56) | 1.36 (0.48–3.89) |

| HPV 31 | 6 (6) | 6 (8) | 1.30 (0.40–4.21) | 1.55 (0.45–5.30) | 5 (13) | 2.07 (0.59–7.23) | 2.20 (0.59–8.20) |

| HPV 33 | 3 (3) | 6 (8) | 2.69 (0.65–11.13) | 2.56 (0.59–11.03) | 6 (15) | 5.29 (1.25–22.37) | 5.23 (1.17–23.24) |

| HPV 35 | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 1.28 (0.18–9.32) | 1.04 (0.14–7.93) | 6 (15) | 8.03 (1.55–41.73) | 6.74 (1.24–36.57) |

| HPV 39 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1.28 (0.08–20.78) | 0.98 (0.06–16.41) | 1 (3) | 2.36 (0.14–38.68) | 1.76 (0.10–30.52) |

| HPV 45 | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | ∞ (0.61-∞) | N/A‡ | 1 (3) | ∞ (0.03-∞) | N/A‡ |

| HPV 52 | 4 (4) | 4 (5) | 1.29 (0.31–5.34) | 1.43 (0.33–6.23) | 3 (8) | 1.80 (0.38–8.46) | 1.78 (0.35–9.12) |

| HPV 58 | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 1.28 (0.18–9.32) | 1.24 (0.14–10.81) | 0 (0) | 0 (0–4.75) | N/A† |

| HPV 68 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A§ | N/A§ | 0 (0) | N/A§ | N/A§ |

Adjusted for age, race, smoking status, BMI, alcohol consumption, and education

0 cases seropositive, only crude OR (95% CI) can be calculated

0 controls seropositive, only crude OR (95% CI) can be calculated

0 cases and 0 controls seropositive

When analyses were restricted to participants without previous polyps, among men, there was a 3.1-fold increase (95% CI: 1.04–9.29) in the odds of hyperplastic polyps associated with HPV seropositivity for all HPV types combined (Table 3). The association between HPV seropositivity and hyperplastic polyps in men without previous polyps appeared to be largely explained by seropositivity to HPV-33 (OR=13.71; 95% CI: 2.28–82.29). No associations were seen for adenomas in men, nor for either polyp type in women when we restricted analyses to participants without previous polyps (Table 3).

Table 3.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals comparing HPV seropositivity in adenoma and hyperplastic cases to controls, stratified by sex, participants without previous polyps: Group Health members, 1998–2003.

| Women (N=184) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (n=118) |

Adenomas (n=39) |

Hyperplastic Polyps (n=27) |

|||||

| N Pos (%) | N Pos (%) | Crude OR | Adjusted* OR | N Pos (%) | Crude OR | Adjusted* OR | |

| Any type | 53 (45) | 14 (36) | 0.69 (0.33–1.45) | 0.79 (0.35–1.75) | 10 (37) | 0.72 (0.30–1.71) | 0.87 (0.34–1.75) |

| HPV 16 | 31 (26) | 6 (15) | 0.51 (0.19–1.33) | 0.60 (0.22–1.64) | 5 (19) | 0.64 (0.22–1.83) | 0.81 (0.25–2.54) |

| HPV 18 | 13 (11) | 4 (10) | 0.92 (0.28–3.01) | 1.22 (0.34–4.28) | 0 (0) | 0 (0–1.17) | N/A† |

| HPV 16 or 18 | 35 (30) | 9 (23) | 0.71 (0.31–1.65) | 0.86 (0.35–2.11) | 5 (19) | 0.54 (0.19–1.54) | 0.65 (0.21–2.06) |

| HPV 31 | 14 (12) | 3 (8) | 0.74 (0.19–2.84) | 0.70 (0.18–2.69) | 3 (11) | 0.93 (0.25–3.49) | 1.84 (0.44–7.72) |

| HPV 33 | 13 (11) | 2 (5) | 0.44 (0.09–2.03) | 0.38 (0.08–1.82) | 2 (7) | 0.65 (0.14–3.05) | 0.41 (0.07–2.20) |

| HPV 35 | 6 (5) | 2 (5) | 1.00 (0.20–5.21) | 1.16 (0.21–6.37) | 2 (7) | 1.49 (0.28–7.84) | 2.28 (0.37–14.02) |

| HPV 39 | 5 (4) | 1 (3) | 0.59 (0.07–5.25) | 0.70 (0.08–6.60) | 1 (4) | 0.87 (0.10–7.76) | 1.84 (0.18–18.77) |

| HPV 45 | 3 (3) | 1 (3) | 1.01 (0.10–9.99) | 0.92 (0.09–9.60) | 0 (0) | 0 (0–5.87) | N/A† |

| HPV 52 | 7 (6) | 1 (3) | 0.42 (0.05–3.50) | 0.41 (0.05–3.45) | 1 (4) | 0.61 (0.07–5.18) | 0.75 (0.08–6.80) |

| HPV 58 | 8 (7) | 1 (3) | 0.36 (0.04–2.98) | 0.38 (0.04–3.34) | 0 (0) | 0 (0–2.13) | N/A† |

| HPV 68 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0–5.72) | N/A† | 0 (0) | 0 (0–9.29) | N/A† |

| Men (N=124) | |||||||

|

Controls n=68) |

Adenomas (n=32) |

Hyperplastic Polyps (n=24) |

|||||

| N Pos (%) | N Pos (%) | Crude OR | Adjusted* OR | N Pos (%) | Crude OR | Adjusted* OR | |

| Any type | 17 (25) | 12 (38) | 1.80 (0.73–4.44) | 1.74 (0.65–4.64) | 12 (50) | 3.00 (1.14–7.91) | 3.10 (1.04–9.29) |

| HPV 16 | 8 (12) | 5 (16) | 1.39 (0.42–4.64) | 1.33 (0.37–4.76) | 5 (21) | 1.97 (0.58–6.76) | 2.42 (0.62–9.44) |

| HPV 18 | 2 (3) | 2 (6) | 2.20 (0.30–16.37) | 1.84 (0.23–14.87) | 4 (17) | 6.60 (1.12–38.73) | 5.72 (0.84–38.71) |

| HPV 16 or 18 | 9 (13) | 7 (22) | 1.84 (0.62–5.48) | 1.88 (0.59–5.97) | 6 (25) | 2.19 (0.69–6.97) | 2.70 (0.75–9.65) |

| HPV 31 | 5 (7) | 4 (13) | 1.80 (0.45–7.21) | 1.71 (0.39–7.42) | 4 (17) | 2.52 (0.62–10.30) | 2.12 (0.46–9.70) |

| HPV 33 | 2 (3) | 4 (13) | 4.71 (0.82–27.24) | 4.54 (0.75–27.66) | 6 (25) | 11.00 (2.04–59.20) | 13.71 (2.28-82-29) |

| HPV 35 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0-4.18) | N/A† | 4 (17) | 13.39 (1.42–126.68) | 10.21 (0.76–137.82) |

| HPV 39 | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | ∞ (0.03-∞) | N/A‡ | 1 (4) | ∞ (0.04-∞) | N/A‡ |

| HPV 45 | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | ∞ (1.13-∞) | N/A‡ | 1 (4) | ∞ (0.04-∞) | N/A‡ |

| HPV 52 | 4 (6) | 2 (6) | 1.07 (0.19–6.15) | 1.02 (0.16–6.41) | 3 (13) | 2.29 (0.47–11.05) | 2.08 (0.35–12.31) |

| HPV 58 | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | ∞ (0.03-∞) | N/A‡ | 0 (0) | N/A§ | N/A§ |

| HPV 68 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A§ | N/A§ | 0 (0) | N/A§ | N/A§ |

Adjusted for age, race, smoking status, BMI, alcohol consumption, and education

0 cases seropositive, only crude OR (95% CI) can be calculated

0 controls seropositive, only crude OR (95% CI) can be calculated

0 cases and 0 controls seropositive

The likelihood ratio test for an interaction between sex and HPV seropositivity suggested that the association between HPV seropositivity for all types combined and hyperplastic polyps among participants without a previous history of polyps differed between men and women (P=0.05). However, the likelihood test for an interaction between sex and seropositivity for adenomas, was not statistically significant (P=0.08).

Among men, there was also a statistically significant interaction between HPV seropositivity and history of previous polyps for adenomas (P-value=0.04) and for hyperplastic polyps (P-value = 0.01). No interactions were observed between history of polyps and HPV seropositivity for either polyp type among women.

Discussion

Despite some previous studies detecting oncogenic HPV DNA in as much as 38% of colorectal adenomas (12), our HPV DNA and antibody analyses showed that there is no association between oncogenic HPV and colorectal adenomas. Previous studies of colorectal neoplasia and HPV have primarily focused on HPV DNA detection in colorectal polyps and tumors using PCR-based methods (9–15, 17–22) and, in some cases, even nested PCR assays (9, 13, 15, 17); only one previous study included HPV antibody analyses of colorectal cancer cases (49).

In previous studies of colorectal adenomas, HPV DNA detection varied, ranging from 0–38% (11, 12, 22), and one of these studies reported a statistically significant difference in the proportion of adenomas positive for HPV DNA (38%) compared to normal colonic tissue from disease-free controls (8%) (12). However, PCR, and particularly nested PCR, is prone to contamination. Also, lesional tissue from cases is often from diagnostic specimens and, as such, is processed with other pathology specimens in a clinical setting; thus, lesional tissue from cases has more opportunity to come into contact with sources of HPV DNA contamination, such as diagnostic cervical biopsies. Evaluation of the association between HPV and colorectal neoplasia by PCR methods alone may be inadequate, and strict contamination control procedures need to be followed at all stages of sample preparation and testing.

Several previous studies examining the association between HPV and colorectal neoplasia included laboratory-based methods to assess potential contamination, such as the use of HPV-negative quality control samples in PCR assays (9, 11),(12, 17, 21), and contamination control procedures, such as changing gloves and pipettes between samples while conducting PCR assays (9, 11, 17). However, none of the previous studies detailed their contamination control procedures for sectioning tissue, including methods to control for contamination that could have occurred during clinical processing. This is an important step at which significant contamination could occur, and it needs to be addressed in study protocols.

In our evaluation of the association between oncogenic HPV and colorectal polyps, we controlled for contamination not just during sample testing, but also during sample preparation. We also used two separate PCR assays to evaluate our samples, and included both positive and negative controls in each run. Using two separate HPV DNA assays improved the overall sensitivity for HPV detection. In addition to our HPV DNA assays, we evaluated the association between oncogenic HPV infection and colorectal polyps using an antibody assay. Not only are antibody assays less susceptible to contamination than PCR, but plasma samples from polyp cases and controls have equal opportunity for other measurement errors. In total, 3 assays were used to evaluate the association between HPV and colorectal adenomas; all three assays failed to provide evidence for an association between HPV and colorectal adenomas.

For hyperplastic polyps, we found slightly different results. As with colorectal adenomas, no HPV DNA was detected in colorectal hyperplastic polyp tissue, and there was no association between HPV antibodies and hyperplastic polyps among women. However, we did observe a marginally statistically significant association between seropositivity to HPV and hyperplastic polyps among men without previous polyps (OR: 3.1; 95% CI: 1.04–9.29). Because this is the first study to examine hyperplastic polyps in relation to HPV infection, and because our sample size for hyperplastic polyps among men without previous polyps was small (n=24), this result should be interpreted with caution. Given that none of the hyperplastic polyp tissue samples were positive for HPV DNA and that the association with HPV antibodies was largely driven by HPV-33, a type rarely found outside the cervix, our antibody findings among men with hyperplastic polyps do not provide evidence for a biological relationship between HPV and hyperplastic polyps. HPV antibody analyses need to be conducted in a separate population of hyperplastic polyp cases and controls to determine if these results can be reproduced or if this is a chance finding.

Persistent infection with HPV is necessary for the virus to cause cancer (50). Therefore, if HPV were important to the etiology of hyperplastic polyps, one would expect to find HPV DNA in the lesions. In the absence of HPV DNA in colorectal tissue, a reproducible positive correlation between HPV seropositivity and colorectal hyperplastic polyps in men could, nonetheless, be a clue to other risk factors for hyperplastic polyps among men. In this case, HPV seropositivity would be serving as a surrogate for the true, and yet-unidentified, risk factor. Further investigation into hyperplastic polyps is warranted to test this hypothesis.

We conducted this study among colonoscopy patients from a single medical-care delivery system to ensure cases and controls were comparable to one another, and to ensure that controls were in fact polyp free. This is particularly important when evaluating risk factors for colorectal polyps, because most polyps, regardless of type, do not cause symptoms, and misclassification of disease status could attenuate associations.

Our study results should be interpreted in light of the several limitations. Even though this is the largest evaluation of the association between colorectal polyps and HPV infection to date, small sample sizes, especially for stratified and restricted analyses, resulted in some imprecise estimates. Also, by conducting both the stratified and restricted analyses, we increased the chances of a type I error. However, our analysis plan was informed by previous studies reporting differences between men and women for the association between HPV antibodies and anal cancer. Finally, we did not collect sexual behavior information, such as number of previous sex partners and history of anal intercourse. Because HPV is a sexually transmitted disease, these data would have allowed us to evaluate the association between colorectal polyps and sexual behavior; in particular, we could have determined if the HPV seropositivity results among men with hyperplastic polyps are consistent with the sexually-transmitted nature of these viruses.

In summary, we conducted a rigorous evaluation of the association between HPV and two types of colorectal polyps and found no evidence to support an etiologic role for HPV in either adenomas or hyperplastic polyps. However, our results suggest that further investigation of HPV seropositivity and colorectal hyperplastic polyps among men may be warranted.

Acknowledgements

We would also like to thank Dr. Elena Kuo for her contributions.

Grant Support

This research was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (P01 CA074184 to PAN & JDP and T32009168 to ABH) and the Investigator Studies Program of Merck and Co, Inc. (to SMS).

References

- 1.Munoz N. Human papillomavirus and cancer: the epidemiological evidence. J Clin Virol. 2000;19(1–2):1–5. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(00)00125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steenbergen RD, de Wilde J, Wilting SM, Brink AA, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ. HPV-mediated transformation of the anogenital tract. J Clin Virol. 2005;32 Suppl 1:S25–S33. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, Pawlita M, Fakhry C, Koch WM, et al. Case-control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(19):1944–1956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses in anogenital cancer as a model to understand the role of viruses in human cancers. Cancer Res. 1989;49(17):4677–4681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S, Herrero R, Castellsague X, Shah KV, et al. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(6):518–527. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoots BE, Palefsky JM, Pimenta JM, Smith JS. Human papillomavirus type distribution in anal cancer and anal intraepithelial lesions. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(10):2375–2383. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, Franceschi S. Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(2):467–475. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miralles-Guri C, Bruni L, Cubilla AL, Castellsague X, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S. Human papillomavirus prevalence and type distribution in penile carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62(10):870–878. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.063149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodaghi S, Yamanegi K, Xiao SY, Da Costa M, Palefsky JM, Zheng ZM. Colorectal papillomavirus infection in patients with colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(8):2862–2867. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buyru N, Tezol A, Dalay N. Coexistence of K-ras mutations and HPV infection in colon cancer. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:115. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng JY, Sheu LF, Lin JC, Meng CL. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA in colorectal adenomas. Arch Surg. 1995;130(1):73–76. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430010075015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGregor B, Byrne P, Kirgan D, Albright J, Manalo P, Hall M. Confirmation of the association of human papillomavirus with human colon cancer. Am J Surg. 1993;166(6):738–740. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80690-7. discussion 741-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perez LO, Abba MC, Laguens RM, Golijow CD. Analysis of adenocarcinoma of the colon and rectum: detection of human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA by polymerase chain reaction. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7(5):492–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee YM, Leu SY, Chiang H, Fung CP, Liu WT. Human papillomavirus type 18 in colorectal cancer. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2001;34(2):87–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Damin DC, Caetano MB, Rosito MA, Schwartsmann G, Damin AS, Frazzon AP, et al. Evidence for an association of human papillomavirus infection and colorectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33(5):569–574. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deschoolmeester V, Van Marck V, Baay M, Weyn C, Vermeulen P, Van Marck E, et al. Detection of HPV and the role of p16INK4A overexpression as a surrogate marker for the presence of functional HPV oncoprotein E7 in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perez LO, Barbisan G, Ottino A, Pianzola H, Golijow CD. Human papillomavirus DNA and oncogene alterations in colorectal tumors. Pathol Oncol Res. 2010;16(3):461–468. doi: 10.1007/s12253-010-9246-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koulos J, Symmans F, Chumas J, Nuovo G. Human papillomavirus detection in adenocarcinoma of the anus. Mod Pathol. 1991;4(1):58–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah KV, Daniel RW, Simons JW, Vogelstein B. Investigation of colon cancers for human papillomavirus genomic sequences by polymerase chain reaction. J Surg Oncol. 1992;51(1):5–7. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930510104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shroyer KR, Kim JG, Manos MM, Greer CE, Pearlman NW, Franklin WA. Papillomavirus found in anorectal squamous carcinoma, not in colon adenocarcinoma. Arch Surg. 1992;127(6):741–744. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420060121018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gornick MC, Castellsague X, Sanchez G, Giordano TJ, Vinco M, Greenson JK, et al. Human papillomavirus is not associated with colorectal cancer in a large international study. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(5):737–743. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9502-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yavuzer D, Karadayi N, Salepci T, Baloglu H, Dabak R, Bayramicli OU. Investigation of human papillomavirus DNA in colorectal carcinomas and adenomas. Med Oncol. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9416-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jass JR. Classification of colorectal cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features. Histopathology. 2007;50(1):113–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noffsinger AE. Serrated polyps and colorectal cancer: new pathway to malignancy. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:343–364. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Stegmaier C, Brenner G, Altenhofen L, Haug U. Risk of progression of advanced adenomas to colorectal cancer by age and sex: estimates based on 840,149 screening colonoscopies. Gut. 2007;56(11):1585–1589. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.122739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. The multistep nature of cancer. Trends Genet. 1993;9(4):138–141. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90209-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leggett BA, Devereaux B, Biden K, Searle J, Young J, Jass J. Hyperplastic polyposis: association with colorectal cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(2):177–184. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200102000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jass JR. Serrated route to colorectal cancer: back street or super highway? J Pathol. 2001;193(3):283–285. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(200103)193:3<283::AID-PATH799>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kambara T, Simms LA, Whitehall VL, Spring KJ, Wynter CV, Walsh MD, et al. BRAF mutation is associated with DNA methylation in serrated polyps and cancers of the colorectum. Gut. 2004;53(8):1137–1144. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.037671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Brien MJ. Hyperplastic and serrated polyps of the colorectum. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2007;36(4):947–968. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2007.08.007. viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morimoto LM, Newcomb PA, Ulrich CM, Bostick RM, Lais CJ, Potter JD. Risk factors for hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps: evidence for malignant potential? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(10 Pt 1):1012–1018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallace K, Grau MV, Ahnen D, Snover DC, Robertson DJ, Mahnke D, et al. The association of lifestyle and dietary factors with the risk for serrated polyps of the colorectum. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(8):2310–2317. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ji BT, Weissfeld JL, Chow WH, Huang WY, Schoen RE, Hayes RB. Tobacco smoking and colorectal hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(5):897–901. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shrubsole MJ, Wu H, Ness RM, Shyr Y, Smalley WE, Zheng W. Alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and risk of colorectal adenomatous and hyperplastic polyps. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(9):1050–1058. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woodman CB, Collins SI, Young LS. The natural history of cervical HPV infection: unresolved issues. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(1):11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salit IE, Tinmouth J, Chong S, Raboud J, Diong C, Su D, et al. Screening for HIV-associated anal cancer: correlation of HPV genotypes, p16, and E6 transcripts with anal pathology. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(7):1986–1992. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carter JJ, Koutsky LA, Hughes JP, Lee SK, Kuypers J, Kiviat N, et al. Comparison of human papillomavirus types 16, 18, and 6 capsid antibody responses following incident infection. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(6):1911–1919. doi: 10.1086/315498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ho GY, Studentsov YY, Bierman R, Burk RD. Natural history of human papillomavirus type 16 virus-like particle antibodies in young women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(1):110–116. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-03-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chia VM, Newcomb PA, Lampe JW, White E, Mandelson MT, McTiernan A, et al. Leptin concentrations, leptin receptor polymorphisms, and colorectal adenoma risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(12):2697–2703. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adams SV, Newcomb PA, Burnett-Hartman AN, White E, Mandelson MT, Potter JD. Circulating 25-Hydroxyvitamin-D and Risk of Colorectal Adenomas and Hyperplastic Polyps. Nutr Cancer. :1. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.535960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chung SM, Chen YT, Panczykowski A, Schamberg N, Klimstra DS, Yantiss RK. Serrated polyps with "intermediate features" of sessile serrated polyp and microvesicular hyperplastic polyp: a practical approach to the classification of nondysplastic serrated polyps. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32(3):407–412. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318158dde2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmitz M, Scheungraber C, Herrmann J, Teller K, Gajda M, Runnebaum IB, et al. Quantitative multiplex PCR assay for the detection of the seven clinically most relevant high-risk HPV types. J Clin Virol. 2009;44(4):302–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kleter B, van Doorn LJ, ter Schegget J, Schrauwen L, van Krimpen K, Burger M, et al. Novel short-fragment PCR assay for highly sensitive broad-spectrum detection of anogenital human papillomaviruses. Am J Pathol. 1998;153(6):1731–1739. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65688-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Waterboer T, Sehr P, Michael KM, Franceschi S, Nieland JD, Joos TO, et al. Multiplex human papillomavirus serology based on in situ-purified glutathione s-transferase fusion proteins. Clin Chem. 2005;51(10):1845–1853. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.052381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stone KM, Karem KL, Sternberg MR, McQuillan GM, Poon AD, Unger ER, et al. Seroprevalence of human papillomavirus type 16 infection in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(10):1396–1402. doi: 10.1086/344354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Markowitz LE, Sternberg M, Dunne EF, McQuillan G, Unger ER. Seroprevalence of human papillomavirus types 6, 11, 16, and 18 in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2004. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(7):1059–1067. doi: 10.1086/604729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carter JJ, Madeleine MM, Shera K, Schwartz SM, Cushing-Haugen KL, Wipf GC, et al. Human papillomavirus 16 and 18 L1 serology compared across anogenital cancer sites. Cancer Res. 2001;61(5):1934–1940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Johnson LG, Schwartz SM, Shera KA, Wurscher MA, et al. Human papillomavirus, smoking, and sexual practices in the etiology of anal cancer. Cancer. 2004;101(2):270–280. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strickler HD, Schiffman MH, Shah KV, Rabkin CS, Schiller JT, Wacholder S, et al. A survey of human papillomavirus 16 antibodies in patients with epithelial cancers. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1998;7(4):305–313. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199808000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trottier H, Franco EL. The epidemiology of genital human papillomavirus infection. Vaccine. 2006;24 Suppl 1:S1–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]