Abstract

Caminibacter mediatlanticus strain TB-2T [1], is a thermophilic, anaerobic, chemolithoautotrophic bacterium, isolated from the walls of an active deep-sea hydrothermal vent chimney on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and the type strain of the species. C. mediatlanticus is a Gram-negative member of the Epsilonproteobacteria (order Nautiliales) that grows chemolithoautotrophically with H2 as the energy source and CO2 as the carbon source. Nitrate or sulfur is used as the terminal electron acceptor, with resulting production of ammonium and hydrogen sulfide, respectively. In view of the widespread distribution, importance and physiological characteristics of thermophilic Epsilonproteobacteria in deep-sea geothermal environments, it is likely that these organisms provide a relevant contribution to both primary productivity and the biogeochemical cycling of carbon, nitrogen and sulfur at hydrothermal vents. Here we report the main features of the genome of C. mediatlanticus strain TB-2T.

Keywords: Epsilonproteobacteria, thermophiles, free-living, anaerobes, chemolithoautotrophy, Nautiliales, deep-sea hydrothermal vent

Introduction

Caminibacter mediatlanticus type strain TB-2T (=DSM 16658T=JCM 12641T) is an epsilonproteobaterium isolated from the walls of an active deep-sea hydrothermal vent on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge [1]. C. mediatlanticus is part of the recently proposed order Nautiliales [2], which comprises three genera: Nautilia, Caminibacter and Lebetimonas. All Nautiliales cultured are thermophilic chemolithoautotrophs and have been isolated from deep-sea hydrothermal vents. The genus Caminibacter includes three described species: C. hydrogeniphilus, the type strain for this genus [3], C. profundus [2], and C. mediatlanticus [1]. All three Caminibacter species are thermophilic (55- 60 °C) and conserve energy by coupling the oxidation of hydrogen to the reduction of nitrate and sulfur. C. profundus can also grow microaerobically (0.5% O2) [2]. The genus Nautilia includes four species: N. lithotrophica [4], N. profundicola, whose genome was recently sequenced [5,6], N. abyssi [7] and N. nitratireducens [8]. While all Nautilia spp. couple hydrogen oxidation to sulfur reduction, N. nitratireducens can also use nitrate, thiosulfate and selenate as terminal electron acceptors [8]. The genus Lebetimonas includes a single species, L. acidiphila, a sulfur-respiring chemolithoautotroph [9]. Here we present a summary of the features of C. mediatlanticus strain TB-2T and a description of its genome.

Classification and features

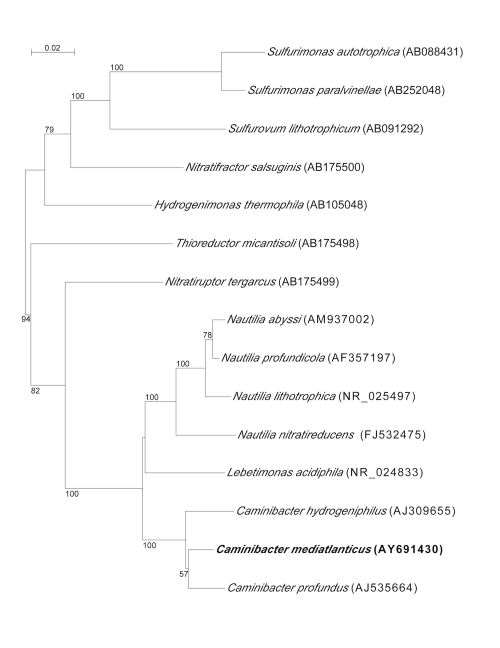

C. mediatlanticus strain TB-2T was isolated from the Rainbow vent field on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (36° 14’ N, 33° 541 W). Caminibacter sp. strain TB-1 [1], C. profundus and C. hydrogeniphilus are the closest relatives to C. mediatlanticus, with a 16S rRNA gene similarity of 99%, 96.3% and 95.9%, respectively. The phylogenetic position of C. mediatlanticus relative to all the known type strains of Epsilonproteobacteria isolated from deep-sea hydrothermal vents is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic position of Caminibacter mediatlanticus strain TB-2T relative to type strains of Epsilonproteobacteria isolated from deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Sequences were aligned automatically using CLUSTAL X and the alignment was manually refined using SEAVIEW [10,11]. Neighbor-joining trees were constructed with Phylo_Win, using the Jukes-Cantor correction [12]. Bootstrap values (>50%) based on 500 replications. Bar, 0.02 substitutions per nucleotide position.

The cells of C. mediatlanticus are Gram-negative rods of approximately 1.5 x 0.75 µm, motile by mean of one to three polar flagella (Figure 2 and Table 1). On solid media, the cells form small brownish colonies. Growth occurs between 45 and 70˚C, 10 and 40 g NaCl L-1 and pH 4.5 and 7.5. Optimal growth conditions are 55˚C, 30 g NaCl l-1 and pH 5.5 (generation time 50 min). Growth occurs under strictly anaerobic, chemolithoautotrophic conditions in the presence of H2 and CO2 with nitrate or sulfur as electron acceptors and the formation of ammonia or hydrogen sulfide, respectively. Oxygen, selenate, arsenate, thiosulfate and sulfite are not used as terminal electron acceptors. No chemoorganoheterotrophic growth has been reported. Evidence that C. mediatlanticus fixes CO2 via the reductive tricarboxylic acid (rTCA) cycle was obtained by the detection, by PCR, of the gene encoding for the ATP citrate lyase, a key enzyme of the cycle, and by the determination of the specific activities of the rTCA enzymes [19]. The genomic G + C content of C. mediatlanticus is 27.13 mol%.

Figure 2.

Electron micrograph of a platinum shadowed cell of Caminibacter mediatlanticus strain TB-2 T showing multiple flagella. Bar, 0.5 μm.

Table 1. Classification and general features of C. mediatlanticus strain TB-2T according to the MIGS recommendations [13].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [14] | |

| Phylum Proteobacteria | TAS [15] | ||

| Class Epsilonproteobacteria | TAS [16,17] | ||

| Order Nautiliales | TAS [2] | ||

| Family Nautiliaceae | TAS [2] | ||

| Genus Caminibacter | TAS [3] | ||

| Species Caminibacter mediatlanticus | TAS [1] | ||

| Type strain TB-2 | TAS [1] | ||

| Gram stain | negative | TAS [1] | |

| Cell shape | short rod | TAS [1] | |

| Motility | motile | TAS [1] | |

| Sporulation | non-sporulating | TAS [1] | |

| Temperature range | 45°C - 70°C | TAS [1] | |

| Optimum temperature | 55 °C | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | opt.: 30 g NaCl l-1 (range 10-40 g NaCl l-1) | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen | obligate anaerobe | TAS [1] |

| Carbon source | CO2 | TAS [1] | |

| Energy source | H2 | TAS [1] | |

| Terminal electron acceptor | NO3, S0 | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | marine, deep-sea hydrothermal vents | TAS [1] |

| MIGS 14 | Pathogenicity | not reported | NAS |

| Biosafety level | 1 | NAS | |

| Isolation | deep-sea hydrothermal vent, black smoker | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free living | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Mid-Atlantic Ridge, Rainbow vent field | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | July 2001 | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | 36° 14’ N | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | 33° 54’ W | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | 2305 m | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | not applicable |

Evidence codes - TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [18]. If the evidence code is IDA, then the property was directly observed, for the purpose of this specific publication, for a live isolate by one of the authors, or an expert or reputable institution mentioned in the acknowledgements.

Chemotaxonomy

None of the classical chemotaxonomic features (peptidoglycan structure, cell wall sugars, cellular fatty acid profile, respiratory quinones, or polar lipids) are known for C. mediatlanticus strain TB-2T.

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

The genome of C. mediatlanticus strain TB-2T was selected for sequencing in 2005, during phase two of the Microbial Genome Sequencing Project of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and it was sequenced at the J. Craig Venter Institute. It was the first genome of an Epsilonproteobacterium from deep-sea hydrothermal vents to be sequenced. C. mediatlanticus was selected because it is a thermophilic member of the Epsilonproteobacteria, which, as a group, represent a significant fraction of the chemosynthetic communities inhabiting the deep-sea hydrothermal vents [20, 21]and because of its ability to fix CO2 under strictly anaerobic conditions [1]. The draft genome sequence was completed in November 2006 and presented for public access on June 19, 2007. The NCBI accession number is ABCJ00000000.1 and consists of 35 contigs (ABCJ01000001-ABCJ01000035). Table 2 shows the project information and its association with MIGS version 2.0 compliance [22].

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Plasmids and cosmids |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | Sanger/pyrosequencing hybrid |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | 8× |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Celera |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | GeneMark and Glimmer |

| Genome Database release | J. Craig Venter Institute | |

| Genbank ID | ABCJ00000000.1 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | June 19, 2007 | |

| GOLD ID | Gi01407 | |

| Project relevance | Chemosynthetic ecosystems, CO2 fixation, Thermophiles |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

C. mediatlanticus was grown in modified SME medium at 55°C under a H2/CO2 gas phase (80:20; 200 kPa) with CO2 as the carbon source and nitrate as the electron acceptor, as described by Voordeckers et al. [1]. Genomic DNA was isolated from 1–1.5 g of pelleted cells using an extraction protocol that involved a phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol(50:49:1) step followed by isopropanol precipitation, as described by Vetriani et al. [23].

Genome sequencing and assembly

Two genomic libraries with insert sizes of 4 and 40 kbp were constructed from the genomic DNA of C. mediatlanticus as described in Goldberg et al. [24]. The resulting plasmid and fosmid clones were sequenced at the J. Craig Venter Institute from both ends to provide paired-end reads and an 8× coverage. The Celera assembler was used to generate contigs and reconstruct the draft genome [25].

Genome annotation

The genome sequence was analyzed using the Joint Genome Institute IMG system [26], the RAST (Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology) server [27], the GenDB annotation program [28] at the Center for Genome Research and Biocomputing at Oregon State University, and the NCBI Prokaryotic Genomes Automatic Annotation Pipeline.

The annotation of the draft genome was done using the Prokaryotic Genomes Automatic Annotation Pipeline of the National Center for Biotechnology Information [29]. The PGAAP combines HMM-based gene prediction methods with a sequence similarity-based approach, and compares the predicted gene products to the non-redundant protein database, Entrez Protein Clusters, the Conserved Domain Database, and the COGs (Clusters of Orthologous Groups).

Gene predictions were obtained using a combination of GeneMark and Glimmer [30-32]. Ribosomal RNAs were predicted by sequence similarity, using BLAST against the non-redundant nucleotide database and/or using Infernal and Rfam models. The tRNAscan-SE [33] was used to find tRNA genes. The predicted CDS were then searched using the NCBI nonredundant protein database. The predicted protein set and major metabolic pathways of TB-2T were searched using the KEGG, SwissProt, COG, Pfam, and InterPro protein databases implemented in the IMG and GenDB systems. Additional gene prediction analysis and manual functional annotation was performed within the IMG and using the Artemis software (release 13.0, Sanger Institute).

Genome properties

The genome consists of a 1,663,618 bp long circular chromosome with a 27.13 mol% G + C content (Table 3). Of the 1,894 genes predicted, 1,826 were protein-coding genes. Of these, 1,180 were assigned to a putative function, while the remaining genes were annotated as coding for hypothetical proteins. In the genome of C. mediatlanticus, 84 protein-coding genes belong to 38 paralogous families, corresponding to a gene content redundancy of 4.44%. The properties and the statistics of the genome are summarized in Table 3. The distribution of genes into Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs) functional categories is shown in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of totala |

|---|---|---|

| Size (bp) | 1,663,618 | |

| G+C content (bp) | 451,320 | 27.13 |

| Coding region (bp) | 1,583,997 | 95.21 |

| Total genesb | 1,894 | |

| RNA genes | 68 | 3.59 |

| Protein-coding genes | 1,826 | 96.41 |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 84 | 4.44 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 1,461 | 77.14 |

| Genes assigned in Pfam domain | 1,371 | 72.39 |

| Genes connected to KEGG pathways | 630 | 33.26 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 214 | 11.30 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 400 | 21.12 |

| Paralogous groups | 38 | 2.01 |

a) The total is based on either the size of the genome in base pairs or the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome.

b) no pseudogenes found.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the 25 general COG functional categories.

| Code | Value | %agea | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | 130 | 7.12 | Translation | |

| K | 53 | 2.9 | Transcription | |

| L | 84 | 4.6 | Replication, recombination and repair | |

| D | 21 | 1.15 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis | |

| V | 14 | 0.77 | Defense mechanisms | |

| T | 79 | 4.33 | Signal transduction mechanisms | |

| M | 108 | 5.91 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis | |

| N | 58 | 3.18 | Cell motility | |

| U | 52 | 2.85 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion | |

| O | 73 | 4 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones | |

| C | 116 | 6.35 | Energy production and conversion | |

| G | 50 | 2.74 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism | |

| E | 128 | 7.01 | Amino acid transport and metabolism | |

| F | 52 | 2.85 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism | |

| H | 87 | 4.76 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism | |

| I | 34 | 1.86 | Lipid transport and metabolism | |

| P | 66 | 3.61 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | |

| Q | 14 | 0.77 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism | |

| R | 153 | 8.38 | General function prediction only | |

| S | 89 | 4.87 | Function unknown | |

| - | 365 | 19.99 | Not in COGs | |

a) The total is based on the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome.

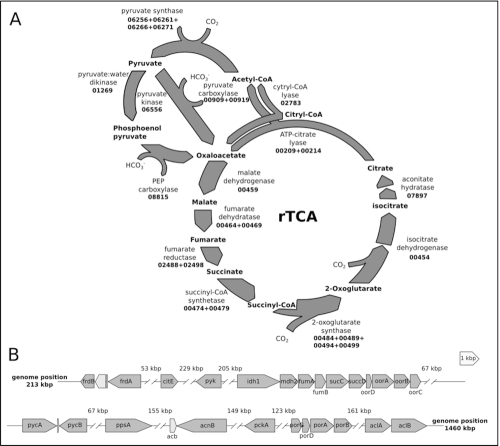

Reconstruction of the rTCA cycle for CO2 fixation from the genome sequence of C. mediatlanticus strain TB-2T

C. mediatlanticus strain TB-2T is an obligate anaerobic, hydrogen-dependent chemolithoautotroph. In this bacterium, CO2 fixation occurs via the reductive tricarboxylic acid (rTCA) cycle [19]. By fixing CO2 in the absence of oxygen, C. mediatlanticus is completely independent from photosynthetic processes, and therefore this bacterium is a true primary producer in the deep ocean (in contrast to aerobic chemosynthetic bacteria, which ultimately depend on photosynthesis-derived oxygen for their energy metabolism). In Figure 3 we show a reconstruction of the rTCA cycle and the organization of the rTCA cycle-related genes in the genome of C. mediatlanticus.

Figure 3.

Reconstruction of the rTCA cycle and related gene clusters in C. mediatlanticus strain TB-2T. A) rTCA cycle. Enzymes are identified by the corresponding gene locus in the C. mediatlanticus genome (CMTB2_gene number). B) Structure of the gene clusters encoding for enzymes involved in rTCA cycle. ORF present within the same clusters are shown in light gray. The distance between clusters is reported in thousands of base pairs (kbp). Genes are oriented according to their direction and drawn to scale. frdBA: fumarate reductase; citE: citril-CoA lyase; pyk: pyruvate kinase; idh1: monomeric isocitrate dehydrogenase; mdh2: malate dehydrogenase; fumAB: fumarate hydratase; sucCD: succinyl-CoA synthetase; oorDABC: 2-oxoglutarate ferredoxin synthase; pycAB: pyruvate carboxylase; ppsA: pyruvate water dikinase; acb: bifunctional aconitate hydratase/methyl isocitrate dehydratase; acnB: aconitate hydratase; pckA: phosphoenol pyruvate carboxy kinase; porGDAB: pyruvate ferredoxinoxido reductase/synthase; aclBA: ATP-citrate lyase.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation for supporting the C. mediatlanticus genome sequencing project, and the technical team at the J. Craig Venter Institute. Work on C. mediatlanticus was supported, entirely or in part, by NSF Grants MCB 04-56676, OCE 03-27353, MCB 08-43678 and OCE 09-37371 to CV, and by the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station.

References

- 1.Voordeckers JW, Starovoytov V, Vetriani C. Caminibacter mediatlanticus sp. nov., a thermophilic, chemolithoautotrophic, nitrate-ammonifying bacterium isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2005; 55:773-779 10.1099/ijs.0.63430-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miroshnichenko ML, L'Haridon S, Schumann P, Spring S, Bonch-Osmolovskaya E, Jeanthon C, Stackebrandt E. Caminibacter profundus sp. nov., a novel thermophile of Nautiliales ord. nov. within the class Epsilonproteobacteria, isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2004; 54:41-45 10.1099/ijs.0.02753-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alain K, Querellou J, Lesongeur F, Pignet P, Crassous P, Raguenes G, Cueff V, Cambon-Bonavita MA. Caminibacter hydrogeniphilus gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel thermophilic, hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium isolated from an East Pacific Rise hydrothermal vent. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2002; 52:1317-1323 10.1099/ijs.0.02195-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miroshnichenko ML, Kostrikina NA, L'Haridon S, Jeanthon C, Hippe H, Stackebrandt E, Bonch-Osmolovskaya EA. Nautilia lithotrophica gen. nov., sp. nov., a thermophilic sulfur-reducing epsilon-proteobacterium isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2002; 52:1299-1304 10.1099/ijs.0.02139-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JL, Campbell BJ, Hanson TE, Zhang CL, Cary SC. Nautilia profundicola sp. nov., a thermophilic, sulfur-reducing epsilonproteobacterium from deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2008; 58:1598-1602 10.1099/ijs.0.65435-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell BJ, Smith JL, Hanson TE, Klotz MG, Stein LY, Lee CK, Wu D, Robinson JM, Khouri HM, Eisen JA, et al. Adaptations to submarine hydrothermal environments exemplified by the genome of Nautilia profundicola. PLoS Genet 2009; 5:e1000362 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alain K, Callac N, Guegan M, Lesongeur F, Crassous P, Cambon-Bonavita MA, Querellou J, Prieur D. Nautilia abyssi sp. nov., a thermophilic, chemolithoautotrophic, sulfur-reducing bacterium isolated from an East Pacific Rise hydrothermal vent. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009; 59:1310-1315 10.1099/ijs.0.005454-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pérez-Rodríguez I, Ricci J, Voordeckers JW, Starovoytov V, Vetriani C. Nautilia nitratireducens sp. nov., a thermophilic, anaerobic, chemosynthetic, nitrate-ammonifying bacterium isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2010; 60:1182-1186 10.1099/ijs.0.013904-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takai K, Hirayama H, Nakagawa T, Suzuki Y, Nealson KH, Horikoshi K. Lebetimonas acidiphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel thermophilic, acidophilic, hydrogen-oxidizing chemolithoautotroph within the 'Epsilonproteobacteria', isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal fumarole in the Mariana Arc. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2005; 55:183-189 10.1099/ijs.0.63330-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galtier N, Gouy M, Gautier C. SEAVIEW and PHYLO\_WIN: two graphic tools for sequence alignment and molecular phylogeny. Computer applications in the biosciences. CABIOS 1996; 12:543-548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL\_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:4876-4882 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perrière G, Gouy M. WWW-query: an on-line retrieval system for biological sequence banks. Biochimie 1996; 78:364-369 10.1016/0300-9084(96)84768-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Phylum XIV. Proteobacteria phyl. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part B, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Validation List No 107. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2006; 56:1-6 10.1099/ijs.0.64188-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Class V. Epsilonproteobacteria class. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part C, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1145. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voordeckers JW, Do MH, Hugler M, Ko V, Sievert SM, Vetriani C. Culture dependent and independent analyses of 16S rRNA and ATP citrate lyase genes: a comparison of microbial communities from different black smoker chimneys on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Extremophiles 2008; 12:627-640 10.1007/s00792-008-0167-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakagawa S, Takai K, Inagaki F, Hirayama H, Nunoura T, Horikoshi K, Sako Y. Distribution, phylogenetic diversity and physiological characteristics of epsilon-Proteobacteria in a deep-sea hydrothermal field. Environ Microbiol 2005; 7:1619-1632 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00856.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.López-García P, Duperron S, Philippot P, Foriel J, Susini J, Moreira D. Bacterial diversity in hydrothermal sediment and epsilonproteobacterial dominance in experimental microcolonizers at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Environ Microbiol 2003; 5:961-976 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00495.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vetriani C, Jannasch HW, MacGregor BJ, Stahl DA, Reysenbach AL. Population structure and phylogenetic characterization of marine benthic Archaea in deep-sea sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 1999; 65:4375-4384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldberg SM, Johnson J, Busam D, Feldblyum T, Ferriera S, Friedman R, Halpern A, Khouri H, Kravitz SA, Lauro FM, et al. A Sanger/pyrosequencing hybrid approach for the generation of high-quality draft assemblies of marine microbial genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103:11240-11245 10.1073/pnas.0604351103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myers EW, Sutton GG, Delcher AL, Dew IM, Fasulo DP, Flanigan MJ, Kravitz SA, Mobarry CM, Reinert KH, Remington KA, et al. A whole-genome assembly of Drosophila. Science 2000; 287:2196-2204 10.1126/science.287.5461.2196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markowitz VM, Chen IMA, Palaniappan K, Chu K, Szeto E, Grechkin Y, Ratner A, Anderson I, Lykidis A, Mavromatis K, et al. The integrated microbial genomes system: an expanding comparative analysis resource. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38:D382-D390 10.1093/nar/gkp887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, et al. The RAST server: Rapid Annotations using Subsystems Technology. BMC Genomics 2008; 9:75 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer F, Goesmann A, McHardy AC, Bartels D, Bekel T, Clausen J, Kalinowski J, Linke B, Rupp O, Giegerich R, Pühler A. GenDB—an open source genome annotation system for prokaryote genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2003; 31:2187-2195 10.1093/nar/gkg312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.NCBI http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/static/Pipeline.html

- 30.Borodovsky M, McIninch J. GENMARK: parallel gene recognition for both DNA strands. Comput Chem 1993; 17:123-133 10.1016/0097-8485(93)85004-V [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delcher AL, Harmon D, Kasif S, White O, Salzberg SL. Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic Acids Res 1999; 27:4636-4641 10.1093/nar/27.23.4636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lukashin AV, Borodovsky M. GeneMark. hmm: new solutions for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res 1998; 26:1107-1115 10.1093/nar/26.4.1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:955-964 10.1093/nar/25.5.955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]