SUMMARY

We analysed the results of haematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) in 30 patients aged 60–78 (median 65) years, with primary myelofibrosis or myelofibrosis evolving from antecedent polycythaemia vera or essential thrombocythaemia. Donors were human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-identical siblings (N = 15) or unrelated individuals (N = 15). Various conditioning regimens were used, ranging from very low intensity (fludarabine plus 2 Gy total body irradiation) to high dose (busulfan plus cyclophosphamide). Stem cell sources were granulocyte colony-stimulating factor mobilized peripheral blood progenitor cells in 29 patients and marrow in one patient. Sustained engraftment was documented in 27 of 30 patients. Day -100 mortality was 13%. With a median follow-up of 22 (range 0.5–69) months, 3-year overall survival and progression-free survival were 45% and 40%, respectively. Currently, 13 patients are surviving. Seven patients died with disease progression at 0.5–22 months, and 10 patients died from other causes at 1.5–37.5 months after HCT. While the selection of older patients for transplantation was probably biased, the present results are encouraging. Motivated older patients with myelofibrosis without substantial comorbid conditions should be offered the option of allogeneic HCT.

Keywords: myelofibrosis, older patients; haematopoietic cell transplantation

INTRODUCTION

The clinical course of primary myelofibrosis (PMF) is variable, but always progressive. Dependent upon patient age and disease features at presentation, the median life expectancy may range from a few years to more than a decade (Cervantes et al, 2009). As the disease advances, patients generally become symptomatic due to varying degrees of anaemia or splenomegaly or both, and present with fatigue and other constitutional symptoms. Patients with polycythaemia vera (PV) or essential thrombocythaemia (ET) may have a rather benign course over many years or even decades. However, when they develop myelofibrosis and reach the advanced phase of their disease, splenomegaly and anaemia may lead to considerable morbidity, similar to that observed with PMF, and treatment options are limited (Tefferi et al, 2007). Eventually the disease may transform into acute leukaemia in a proportion of patients.

The recent identification of mutations in the JAK2 gene in almost all patients with PV and 50%–60% of patients with PMF or ET has generated considerable enthusiasm about the possibility of developing compounds that might inhibit JAK2 autophosphorylation. Several such compounds are currently being tested in clinical trials (Mesa et al, 2008; Verstovsek et al, 2010). Data so far suggest that the major benefit is regression of splenomegaly and improvement in subjective well-being (Cervantes et al, 2009; Verstovsek et al, 2010; Mesa et al, 2008). While the follow-up of patients enrolled in clinical trials with JAK2 inhibitors is still short, inhibition of JAK2 is not expected to be curative for these diseases. Allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is currently the only treatment modality with proven curative potential (Cervantes et al, 2009; Kerbauy et al, 2007; Kröger et al, 2009; Rondelli et al, 2005; Ballen et al, 2010). Typically, HCT has been offered to patients with progressive peripheral blood cytopenias or evidence of transformation to leukaemia.

As most patients with PMF and many patients with myelofibrosis after PV or ET are 60 years of age or older, they have frequently been excluded from HCT because of concern about regimen-related toxicity. Stepwise modification of high dose regimens and the development of reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens has enabled transplants to be performed successfully in older patients (Cervantes et al, 2009; Deeg et al, 2003; Kerbauy et al, 2007; Devine et al, 2002; Hessling et al, 2002; Snyder et al, 2006; Snyder et al, 2010). Both strategies have been shown to result in rapid regression of bone marrow fibrosis and to induce molecular remissions in JAK2 V617F positive patients (Kroger et al, 2007a)

To evaluate the outcome of transplantation in older patients with myelofibrosis, we performed a retrospective analysis of results in 30 patients, aged 60 years or older, who were transplanted after conditioning with various intensity conditioning regimens.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

A retrospective analysis was performed of the transplant course of 30 patients with PMF or myelofibrosis following PV or ET who had undergone allogeneic HCT at one of four academic centres in the U.S.A between December 1999 and December 2007. All patients had given informed consent according to the requirements at the respective institutions. Pertinent patient, disease and transplant characteristics are summarized in Table I. Patients were 60–78 (median 65.0) years old. Seven patients had shown leukemic transformation and five of these were refractory to chemotherapy. Two patients had failed a prior autologous transplant. Co-morbidity scores as determined by the Haematopoietic Cell Transplantation Co-morbidity Index (HCT-CI) ranged from 0 to 6 (Sorror et al, 2005).

Table I.

Patient and disease characteristics, transplant regimen, and outcome

| Patient | Diagnosis | Age (year s) |

Disease Duration (months) |

Co- Morbidity Score2 |

Donor | Conditioning Regimen1 |

GVHD Prophylaxis |

Engraft | GVHD Acute (grade)- chronic |

Chimerism4 | Disease Progression |

PFS (months ) |

OS (month s) |

Cause of Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | PMF | 60 | 5.6 | 2 | MSIB | Bu/Cy | CSP, MTX | Y | 3-n/a | n/a | N | 3.6 | 3.6 | Multi-Organ Failure |

| 20 | PMF | 60 | 7 | 1 | URD | Bu/Cy | CSP, MTX | Y | 3-Y | n/a | Y | 4.8 | 6.2 | Disease Progression |

| 21 | PMF | 60 | 56 | 1 | MSIB | Bu/Cy | CSP, MTX | Y | 2-N | Donor | N | 6.5 | 6.5 | Infection |

| 9 | PMF | 64 | 25 | 0 | URD | Bu/Cy/ATG | CSP, MTX | Y | 0-N | Donor CD3 CD33 | Y | 13.2 | 18.0 | Disease Progression |

| 18 | PMF | 60 | 12 | 3 | MSIB | Bu/Cy/ATG | CSP, MTX | Y | 0-N | Donor CD3 CD33 | N | >68.6 | >68.6 | n/a |

| 3 | PMF | 70 | 4.3 | 6 | URD | camp/Flu/ CD45/4.5 Gy TBI | Tacrolimus | Y | 0-N | Donor | N | 13.2 | 13.2 | Respiratory Failure |

| 11 | PMF | 63 | 7.6 | 4 | MSIB | camp/Flu/ CD45/4.5 Gy TBI | Tacrolimus | Y | 0-N | Donor3 | Y | >24.4 | >73.0 | n/a |

| 15 | PMF | 62 | 65 | 8 | URD | Flu/camp/4.5 Gy TBI | Tacrolimus | N | 0-n/a | Host | Y | 0.0 | 1.2 | Disease Progression |

| 17 | PMF | 61 | 18 | 3 | URD | Flu/camp/4.5 Gy TBI | Tacrolimus | Y | 4- n/a | Donor | N | 2.6 | 2.6 | GVHD |

| 25 | MF post ET | 65 | 122 | 6 | MSIB | Flu/Bu | Tac, MTX | Y | 0-Y | Donor | N | 37.6 | 37.6 | Infection |

| 29 | MF post PV | 66 | 165 | 1 | MSIB | Flu/Bu | Tac, MTX | Y | 0-Y | Donor CD3, CD33 | N | >42.4 | >42.4 | n/a |

| 30 | MF post ET. | 66 | 42 | 1 | MSIB | Flu/Bu | Tac, MTX | Y | 2-N | Mixed chimerism | N | 4.0 | 4.0 | Acute GVHD |

| 2 | PMF | 75 | 69 | 0 | MSIB | Flu/Bu/ATG | Tac, MTX | Y | 1-N | Mixed chimerism | N | >43.2 | >43.2 | n/a |

| 27 | MF post ET | 61 | 108 | 3 | MSIB | Bu/Flu/ATG | Tac, MTX | Y | 0-N | Donor CD3 CD33 | N | >3.3 | >32.4 | n/a |

| 1 | PMF | 78 | 35 | 4 | URD | Flu/2 Gy TBI | CSP, MMF | Y | 2-N | Donor CD3 CD33 | N | >26.3 | >26.3 | n/a |

| 4 | PMF | 69 | 5.6 | 6 | MSIB | Flu/2 Gy TBI | CSP, MMF | N | n/a | n/a | Y | 0.0 | 0.6 | Disease Progression |

| 5 | PMF | 68 | 67 | 5 | MSIB | Flu/2 Gy TBI | Tacro, MMF | Y | 1-N | Donor CD3 CD33 | N | >50.2 | >50.2 | n/a |

| 7 | PMF | 66 | 5 | 1 | MSIB | Flu/2 Gy TBI | CSP, MTX | Y | 0-Y | n/a | N | 14.2 | 14.2 | Infection |

| 8 | PMF | 65 | 3 | 2 | URD | Flu/2 Gy TBI | CSP, MMF | Y | 2-Y | n/a | Y | 6.1 | 11.3 | Disease Progression |

| 10 | PMF | 64 | 101 | 3 | URD | Flu/2 Gy TBI | CSP, MMF | Y | 2-Y | Donor CD3 CD33 | Y | 11.7 | 11.7 | Disease Progression |

| 12 | PMF | 63 | 39 | 6 | URD | Flu/2 Gy TBI | CSP, MMF | N | 2-N | Donor CD3 CD33 | N | >25.9 | >25.9 | n/a |

| 13 | PMF | 63 | 29 | 3 | URD | Flu/2 Gy TBI | CSP, MMF | Y | 0-n/a | n/a | N | 1.6 | 1.6 | Respiratory Failure |

| 14 | PMF | 62 | 10.5 | 1 | MSIB | Flu/2 Gy TBI | Tac, MTX | Y | 2-N | Donor CD3 CD33 | N | >8.4 | >42.5 | n/a |

| 23 | MF post ET | 73 | 130 | 0 | URD | Flu/2 Gy TBI | CSP, MMF | Y | 1-Y | Donor CD3 CD33 | N | >56.4 | >56.4 | n/a |

| 24 | MF post ET | 67 | 4 | 2 | URD | Flu/2 Gy TBI | CSP, MMF | Y | 2-Y | Donor CD3 CD33 | N | >18.4 | >18.4 | n/a |

| 26 | MF post ET | 64 | 4.1 | 0 | MSIB | Flu/2 Gy TBI | CSP, MMF | Y | 0-N | Host | Y | >1.0 | >4.7 | n/a |

| 28 | MF post PV | 66 | 27 | 4 | URD | Flu/2 Gy TBI | CSP, MMF | Y | 3- n/a | Donor CD3 CD33 | N | 6.6 | 6.6 | Infection |

| 6 | PMF | 67 | 7.3 | 4 | URD | Flu/Mel/ATG | Tac/MTX/Pentostatin | N | 1-Y | Not done | Y | 0.0 | 22.1 | Disease Progression, Autologous Recovery |

| 22 | PMF | 60 | 93 | n/a | MSIB | Flu/Mel/ATG | CSP, MMF | Y | 0-n/a | n/a | N | 3.4 | 3.4 | Dissecting Aneurysm |

| 16 | PMF | 62 | 8.2 | 2 | URD | Flu/Mel/camp | Tacrolimus | Y | 1-limited | Donor | N | >48.7 | >48.7 | n/a |

Patients 8 and 13 had failed a preceding autologous transplant.

Patients 2, 6, 15, 25, 28, 29 and 30 had shown leukaemic transformation before transplantation

Patients ordered by conditioning regimen.

Flu/2 Gy TBI = Fludarabine 3 × 30 mg/m2 i.v. plus 2 Gy total body irradiation (TBI).

Flu/Bu + ATG = Fludarabine 4 × 30 mg/m2 i.v. plus busulfan 9.6 mg/kg to 16 mg/kg given over 3 to 4 days (adjusted to achieve steady state plasma levels of 800–900 ng/ml) or fludarabine 4 × 40 mg/m2 plus busulfan 2 × 130 mg/m2 with or without thymoglobulin (ATG) 6 mg/kg i.v. over 3 days.

camp/Flu/CD45/4.5 Gy TBI = Alemtuzumab (campath) 4 × 10 mg/kg, fludarabine 30 mg/m2 × 4, anti-CD45 antibody, 4 × 0.4 mg/kg, plus 4.5 Gy of TBI.

Flu/Mel/ATG (or camp) = Fludarabine 5 × 15 mg/m2 plus melphalan (Mel) 70 mg/m2 × 2, plus Alemtuzumab (campath) 3 × 10 mg or ATG (Atgam) 4 × 10 mg/kg.

Bu//Cy ± ATG = Busulfan 16 mg/kg per 4 days with dose adjustments to achieve plasma steady state concentrations of 800–900 ng/ml plus cyclophosphamide (Cy) 2 × 60 mg/kg i.v., with or without ATG 4.5 mg/kg given over 30 days.

Flu/camp/4.5 Gy TBI = Fludarabine 30 mg/m2 × 4, Alemtuzumab (campath) 4 × 10 mg/kg plus 4.5 Gy of TBI.

According to HCT-CI

After a second transplant

In patients indicated by “Donor” chimerism was determined in total marrow mononuclear cells. Other patients had separate determination in CD3+ and CD33+ cells.

Abbreviations: CSP = cyclosporine; MF post-ET or PV = myelofibrosis after preceding diagnosis of Essential Thrombocythaemia or Polycythaemia vera; MMF = mycophenolate mofetil; MTX = methotrexate; N = no; n/a = not applicable; PMF = primary myelofibrosis; Tac = tacrolimus; Y= yes.

Donor and transplant characteristics

Donors were human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-identical siblings in 15 and HLA-matched unrelated volunteers in 15 patients. Thirteen patients were conditioned with fludarabine (Flu) plus 2 Gy total body irradiation (TBI) (Laport et al, 2008), two with Flu plus melphalan (Mel) plus anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) (Popat et al, 2006; Oran et al, 2007), four with anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab (campath [camp]) combined with Flu (Popat et al, 2005), anti-CD45 antibody and 4.5 Gy TBI (Popat et al, 2005), two with Flu plus busulfan (Bu) (de Lima et al, 2004), two with Flu plus Bu and ATG, three with Bu plus cyclophosphamide (Cy), two with Bu plus Cy with ATG (Kerbauy et al, 2007), and one with Bu plus Mel and camp (Popat et al, 2005).

The source of stem cells was granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) mobilized peripheral blood progenitor cells (PBPC) in 29 patients who received 8.5 ± 4.2 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg, and bone marrow in one patient (Patient 8; 4.1 × 108 mononuclear cells/kg). Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis consisted of previously described regimens, including cyclosporine (CSP) plus mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) in 11 patients (Giaccone et al, 2005), tacrolimus (Tac) plus methotrexate (MTX) in 6, Tac in 5, CSP plus MTX in 6, and Tac plus MMF in one patient (Eissa et al, 2010).

Evaluation

Time of engraftment was defined as the first of three consecutive days with an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≥ 0.5 × 109/l, and platelet engraftment as the first of three days with platelet counts > 20 × 109/l, without transfusion support (Petersdorf et al, 1998). Patients were subsequently followed for complete recovery of (donor-derived) haematopoiesis. Patients were also evaluated for regression of splenomegaly and marrow fibrosis. Acute and chronic GVHD severity were assessed and treated as described previously (Martin et al, 1998; Benesch & Deeg, 2008). We did not reclassify chronic GVHD according to the more recently developed National Institutes of Health consensus criteria (Filipovich et al, 2005; Flowers et al, 2009).

Relapse/disease progression was defined as re-appearance or persistence of host cells with the morphological, cytogenetic, molecular or immunophenotypic markers of the disease pretransplant. The presence of residual marrow fibrosis in the absence of those markers was not considered as disease persistence as in some patients fibrosis resolves only slowly (Sale et al, 2006).

Statistical analysis

Kaplan-Meier estimates were used to plot overall survival. All statistical analyses were performed using R 2.8.0 statistical software. Results were analysed as of April 2010.

RESULTS

Engraftment and Haematopoietic Recovery

Primary engraftment of donor cells with recovery of normal haematopoietic parameters was documented in 27 of 30 patients. One patient died on day 17, too early to assess for engraftment. The remaining two patients, conditioned with Flu/Mel/ATG and Flu/Camp/CD45/TBI, respectively, both showed disease progression. One surviving patient (Patient 3) was found to be a mixed chimera at the last chimerism determination (day 100). While chimerism has not been tested since, the patient has shown normal haematopoietic recovery. Except for the nine patients with disease progression or relapse, splenomegaly regressed and marrow examination showed improvement or complete resolution of marrow fibrosis in all those who were followed for at least 6 months.

GVHD

Acute GVHD grades II–IV/III–IV developed in 11/4 of 27 evaluable patients (40%/ 15%), and chronic GVHD occurred in 10 of 22 evaluable patients (45%) (Table I).

Relapse

Four patients died before day 100, two with disease progression (days 17 and 37, respectively), one with respiratory failure (day 49), and one with GVHD (day 79). Overall, disease progression or relapse occurred in 9 patients, for an incidence of 30% at 3 years. Three of these patients lacked evidence of donor cell engraftment (see above). Among the remaining six patients, three had been conditioned with Flu/2Gy TBI (one transplanted from a sibling and two from unrelated donors), two with Bu/Cy ± ATG (both transplanted from unrelated donors), and one with Flu/Camp/CD45/TBI (transplanted from a sibling donor).

It was of note that none of the eight patients with antecedent ET or PV showed disease progression or relapse, although two died with infections and one from complications related to GVHD.

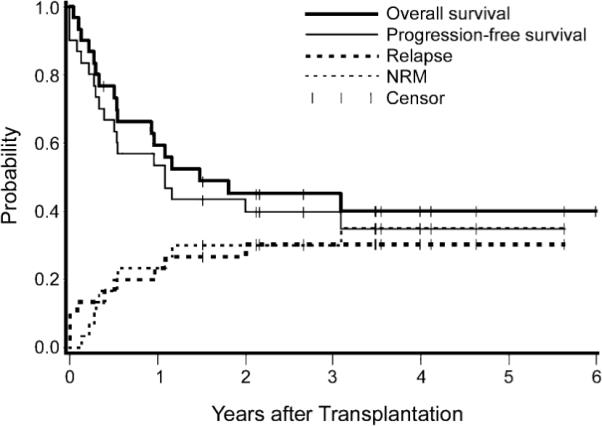

Survival

With a follow-up of 0.5–69 (median 22) months, 13 patients have survived for an overall survival (OS) of 45% and progression-free survival of 40% at 3 years (Fig 1). There was no significant difference in survival between patients aged 60–65 years and those 66–78 years of age.

Fig 1.

Overall survival, progression-free survival, relapse, and non-relapse mortality in 30 patients with myelofibrosis aged 60–78 years.

Causes of Death

At last follow-up 17 patients had died (Table I). Seven patients died with disease progression (6 of these had been transplanted from unrelated donors) and 10 patients (6 transplanted from HLA-identical siblings and 4 recipients of unrelated donor transplants) died from non-relapse causes, for a 3-year incidence of non-relapse mortality of 30%. Major causes of death were infections and organ failure.

DISCUSSION

While the early disease course of patients with PMF and other myeloproliferative neoplasms that may progress to myelofibrosis generally is indolent, management becomes increasingly challenging at more advanced disease stages. The only treatment modality with proven curative potential, generally reserved for advanced disease, is HCT. There has been reluctance to offer HCT to older patients with myelofibrosis, because of concerns about treatment-related toxicity. However, some reports have shown very encouraging results, particularly in patients conditioned with RIC regimens (Snyder et al, 2006; Kröger et al, 2009; Rondelli et al, 2005; Snyder et al, 2010). In the present analysis we combined data on 30 patients, 60 years or older, who were transplanted for myelofibrosis at one of four centres in the USA. The focus was on age rather than a particular conditioning regimen. The results showed that patients in their 60s and even 70s can be transplanted successfully and achieve complete haematological recovery following conditioning with regimens of various intensities, which was remarkable given the age and co-morbid illnesses present in this cohort.

Sequential marrow or blood samples to assess donor cell engraftment were available only in a proportion of patients. However, among patients with haematological reconstitution and without other evidence of disease progression, only one patient was found to be a mixed chimera (as determined by CD33+ cells) at the latest chimerism determination. Persistent mixed donor/patient chimerism in patients with myelofibrosis has been reported previously even in patients conditioned with high intensity regimens (Kerbauy et al, 2007). Currently 13 of 30 patients are surviving, 11 in unmaintained remission. These include 7 of 14 conditioned with Flu/2Gy TBI, and 6 of 16 conditioned with other regimens, including 3 of 4 patients conditioned with a Flu/Bu combination at “conventional” doses as used in younger patients (Kerbauy et al, 2007) Among seven patients with evidence of leukaemia transformation at the time of HCT, two died from disease progression, and three with infectious complications, while two are alive. One of these is in complete remission at 73 months after receiving a second transplant. The second patient is alive at 43.2 months, showing mixed chimerism at the latest determination. A recent report by Ciurea et al (2010) indicates that superior long-term survival may be obtained in patients who responded to pre-HCT chemotherapy and were conditioned with a melphalan-based regimen.

Several previous reports have included transplant results in older patients with myelofibrosis (Kerbauy et al, 2007; Devine et al, 2002; Hessling et al, 2002; Snyder et al, 2006; Kröger et al, 2009; Rondelli et al, 2005; Snyder et al, 2010). Nine patients, median age 54 years, were transplanted using a reduced intensity regimen of fludarabine and TBI (Snyder et al, 2006). Seven of 9 patients engrafted, and the probability of survival at one year was 55%. A more recent report from the same center group suggests that superior results are achieved with a regimen that includes tacrolimus plus sirolimus for GVHD prophylaxis (Snyder et al, 2010). Kroger, et al (2007b) treated 21 patients, 32–63 (median 53) years old, with a busulfan (10 mg/kg), fludarabine (180 mg/m2) plus ATG regimen. Engraftment was achieved in all but one patient, and the 3-year progression-free survival was reported to be 84%. Thus, survival was higher than in the present study, but patients were also younger by more than a decade. The relevance of age is underscored by a more recent report on results in 103 patients by the same investigators (Kröger et al, 2009) showing overall survival of 48% among patients who were older than 55 years at the time of HCT. Rondelli, et al (2005) reported results in 21 patients, 27–68 (median 54) years of age, treated with five different RIC regimens at several centres. Fifteen patients achieved initial engraftment. At a median follow-up of 31 months, 17 patients were alive in remission. Another report on 104 patients, 18–70 years of age, with PMF or myelofibrosis after PV or ET showed a 7-year survival of 61% (Kerbauy et al, 2007). That report included 9 patients older than 60 years who were conditioned with a regimen of fludarabine plus 2 Gy TBI, of whom 4 (44%) were surviving in remission. Ballen et al (2010) recently presented results on 289 patients with PMF reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (Ballen et al, 2010). Patients were 18–73 (median 47) years old and were transplanted from related (N = 188) or unrelated donors (N = 101). The day-100 non-relapse mortality was 18% and 35% for related and unrelated transplant recipients, respectively. The corresponding 5-year relapse-free survival probabilities were 33% and 27%, respectively. For patients conditioned with RIC regimens, 3-year relapse-free survival was 39% and 17% for related and unrelated HCT, respectively.

Thus, considering the age range of patients included in the present report, results compare favourably with other data in the literature. Overall these studies suggest that patients with advanced myelofibrosis, either PMF or myelofibrosis following PV or ET, even in the 7th or 8th decade of life can be treated successfully and be cured by HCT. While all consecutive patients from the four centres were included, it must be acknowledged that the selection of older patients for HCT and the choice of conditioning regimens used in preparation for HCT was likely to have been biased. Presumably, decisions were not based on chronological, but rather “biological” age, no matter how difficult this may be to define.

As pharmacological inhibitors of JAK2 are becoming available, it is likely that in some patients HCT will be delayed as long as symptomatic responses to JAK2 inhibition are observed. It is possible, therefore, that patients will be referred for HCT at an even more advanced disease stage, and it remains to be seen whether results as encouraging as the present ones are achievable in those patients. Further trials are needed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Franchesca Nguyen and Gresford Thomas for data management, Romelia May and Michelle Bouvier RN for data collection, and Helen Crawford and Bonnie Larson for help with manuscript preparation.

The project was supported by P01 HL036444, PO1 CA018029, P30 CA015704, PO1 CA078902, (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center), T32 DK007115, PO1 CA108671 (University of Utah) and Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA125123 (Baylor College of Medicine) from the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Ballen KK, Shrestha S, Sobocinski KA, Zhang MJ, Bashey A, Bolwell BJ, Cervantes F, Devine SM, Gale RP, Gupta V, Hahn TE, Hogan WJ, Kroger N, Litzow MR, Marks DI, Maziarz RT, McCarthy PL, Schiller G, Schouten HC, Roy V, Wiernik PH, Horowitz MM, Giralt SA, Arora M. Outcome of transplantation for myelofibrosis. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2010;16:358–367. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benesch M, Deeg HJ. Acute graft-versus-host disease. In: Soiffer RJ, editor. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2008. p. 589. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes F, Dupriez B, Pereira A, Passamonti F, Reilly JT, Morra E, Vannucchi AM, Mesa RA, Demory JL, Barosi G, Rumi E, Tefferi A. New prognostic scoring system for primary myelofibrosis based on a study of the International Working Group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment. Blood. 2009;113:2895–2901. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-170449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciurea SO, de Lima M, Giralt S, Saliba R, Bueso-Ramos C, Andersson BS, Hosing CM, Verstovsek S, Champlin RE, Popat U. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for myelofibrosis with leukemic transformation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2010;16:555–559. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lima M, Couriel D, Thall PF, Wang X, Madden T, Jones R, Shpall EJ, Shahjahan M, Pierre B, Giralt S, Korbling M, Russell JA, Champlin RE, Andersson BS. Once-daily intravenous buslfan and fludarabine: clinical and pharmacokinetic results of a myeloabltive, reduced-toxicity conditioning regimen for allogeneic stem cell transplantation in AML and MDS. Blood. 2004;104:857–864. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeg HJ, Gooley TA, Flowers MED, Sale GE, Slattery JT, Anasetti C, Chauncey TR, Doney K, Georges GE, Kiem H-P, Martin PJ, Petersdorf EW, Radich J, Sanders JE, Sandmaier BM, Warren EH, Witherspoon RP, Storb R, Appelbaum FR. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for myelofibrosis. Blood. 2003;102:3912–3918. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine SM, Hoffman R, Verma A, Shah R, Bradlow BA, Stock W, Maynard V, Jessop E, Peace D, Huml M, Thomason D, Chen Y-H, van Besien K. Allogeneic blood cell transplantation following reduced-intensity conditioning is effective therapy for older patients with myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. Blood. 2002;99:2255–2258. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissa H, Gooley TA, Sorror ML, Nguyen F, Scott BL, Doney K, Loeb KR, Martin PJ, Pagel JM, Radich JP, Sandmaier BM, Warren EH, Storb R, Appelbaum FR, Deeg HJ. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: relapse-free survival is determined by karyotype and comorbidities. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.09.018. prepublished online September 26, 2010; doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, Socie G, Wingard JR, Lee SJ, Martin P, Chien J, Prezepiorka D, Couriel D, Cowen EW, Dinndorf P, Farrell A, Hartzman R, Henslee-Downey J, Jacobsohn D, McDonald G, Mittleman B, Rizzo JD, Robinson M, Schubert M, Schultz K, Shulman H, Turner M, Vogelsang G, Flowers MED. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and Staging Working Group report. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2005;11:945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers MED, Storer BE, Lee SJ, Campregher PV, Vigorito AC, Carpenter PA, Mielcarek M, Appelbaum FR, Martin PJ. Risk factors for the development of acute and National Institute of Health (NIH) chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2009;114:146. Abstract 345. [Google Scholar]

- Giaccone L, McCune JS, Maris MB, Gooley TA, Sandmaier BM, Slattery JT, Cole S, Nash RA, Storb R, Georges GE. Pharmacodynamics of mycophenolate mofetil after nonmyeloablative conditioning and unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2005;106:4381–4388. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessling J, Kroger N, Werner M, Zabelina T, Hansen A, Kordes U, Ayuk FA, Renges H, Panse J, Erttmann R, Zander AR. Dose-reduced conditioning regimen followed by allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. British Journal of Haematology. 2002;119:769–772. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerbauy DMB, Gooley TA, Sale GE, Flowers MED, Doney KC, Georges GE, Greene JE, Linenberger M, Petersdorf E, Sandmaier BM, Scott BL, Sorror M, Stirewalt DL, Stewart M, Witherspoon RP, Storb R, Appelbaum FR, Deeg HJ. Hematopoietic cell transplantation as curative therapy for idiopathic myelofibrosis, advanced polycythemia vera, and essential thrombocythemia. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2007;13:355–365. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroger N, Badbaran A, Holler E, Hahn J, Kobbe G, Bornhauser M, Reiter A, Zabelina T, Zander AR, Fehse B. Monitoring of the JAK2-V617F mutation by highly sensitive quantitative real-time PCR after allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with myelofibrosis. Blood. 2007a;109:1316–1321. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-039909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroger N, Thiele J, Zander A, Schwerdtfeger R, Kobbe G, Bornhauser M, Bethge W, Schubert J, de Witte T, Kvasnicka HM. Rapid regression of bone marrow fibrosis after dose-reduced allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with primary myelofibrosis. Experimental Hematology. 2007b;35:1719–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kröger N, Holler E, Kobbe G, Bornhauser M, Schwerdtfeger R, Baurmann H, Nagler A, Bethge W, Stelljes M, Uharek L, Wandt H, Burchert A, Corradini P, Schubert J, Kaufmann M, Dreger P, Wulf GG, Einsele H, Zabelina T, Kvasnicka HM, Thiele J, Brand R, Zander AR, Niederwieser D, de Witte TM. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation after reduced-intensity conditioning in patients with myelofibrosis: a prospective, multicenter study of the Chronic Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Blood. 2009;114:5264–5270. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-234880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laport GG, Sandmaier BM, Storer BE, Scott BL, Stuart MJ, Lange T, Maris MB, Agura ED, Chauncey TR, Wong RM, Forman SJ, Petersen FB, Wade JC, Epner E, Bruno B, Bethge WA, Curtin PT, Maloney DG, Blume KG, Storb RF. Reduced-intensity conditioning followed by allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for adult patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and myeloproliferative disorders. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2008;14:246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, Nash R, Sanders J, Leisenring W, Anasetti C, Deeg HJ, Storb R, Appelbaum F. Reproducibility in retrospective grading of acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1998;21:273–279. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesa RA, Verstovsek S, Kantarjian HM, Pardanani AD, Friedman S, Newton R, Erickson-Viitanen S, Hunter D, Redman J, Yeleswaram S, Bradley E, Tefferi A. INCB018424, a selective JAK1/2 inhibitor, significantly improves the compromised nutritional status and frank cachexia in patients with myelofibrosis (MF) Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2008;112:621–622. Abstract 1760. [Google Scholar]

- Oran B, Giralt S, Saliba R, Hosing C, Popat U, Khouri I, Couriel D, Qazilbash M, Anderlini P, Kebriaei P, Ghosh S, Carrasco-Yalan A, de Meis E, Anagnostopoulos A, Donato M, Champlin RE, de Lima M. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for the treatment of high-risk acute myelogenous leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome using reduced-intensity conditioning with fludarabine and melphalan. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2007;13:454–462. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersdorf EW, Gooley TA, Anasetti C, Martin PJ, Smith AG, Mickelson EM, Woolfrey AE, Hansen JA. Optimizing outcome after unrelated marrow transplantation by comprehensive matching of HLA class I and II alleles in the donor and recipient. Blood. 1998;92:3515–3520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popat U, Carrum G, May R, Lamba R, Krance RA, Heslop HE, Brenner MK. CD52 and CD45 monoclonal antibodies for reduced intensity hemopoietic stem cell transplantation from HLA matched and one antigen mismatched unrelated donors. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2005;35:1127–1132. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popat U, Heslop HE, Durett A, May R, Krance RA, Brenner MK, Carrum G. Outcome of reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (RISCT) using antilymphocyte antibodies in patients with high-risk acute myeloid leukemia (AML) Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2006;37:547–552. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondelli D, Barosi G, Bacigalupo A, Prchal JT, Popat U, Alessandrino EP, Spivak JL, Smith BD, Klingemann HG, Fruchtman S, Hoffman R. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning in intermediate- or high-risk patients with myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. Blood. 2005;105:4115–4119. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sale GE, Deeg HJ, Porter BA. Regression of myelofibrosis and osteosclerosis following hematopoietic cell transplantation assessed by magnetic resonance imaging and histologic grading. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2006;12:1285–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder DS, Palmer J, Stein AS, Pullarkat V, Sahebi F, Cohen S, Vora N, Gaal K, Nakamura R, Forman SJ. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation following reduced intensity conditioning for treatment of myelofibrosis. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2006;12:1161–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder DS, Palmer J, Gaal K, Stein AS, Pullarkat V, Sahebi F, Vora N, Nakamura R, Forman SJ. Improved outcomes using tacrolimus/sirolimus for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis with a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen for allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant as treatment of myelofibrosis. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2010;16:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb RF, Baron F, Sandmaier BM, Maloney DG, Barry SE. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific-comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2005;11(Suppl. 1):23–24. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2004. Abstract 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Thiele J, Orazi A, Kvasnicka HM, Barbui T, Hanson CA, Barosi G, Verstovsek S, Birgegard G, Mesa R, Reilly JT, Gisslinger H, Vannucchi AM, Cervantes F, Finazzi G, Hoffman R, Gilliland DG, Bloomfield CD, Vardiman JW. Proposals and rationale for revision of the World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and primary myelofibrosis: recommendations from an ad hoc international expert panel. Blood. 2007;110:1092–1097. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-083501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstovsek S, Kantarjian H, Mesa RA, Pardanani AD, Cortes-Franco J, Thomas DA, Estrov Z, Fridman JS, Bradley EC, Erickson-Viitanen S, Vaddi K, Levy R, Tefferi A. Safety and efficacy of INCB018424, a JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor, in myelofibrosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:1117–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]