Abstract

Assisting patients and their families in complex decision making is a foundational skill in palliative care; however, palliative care clinicians and scientists have just begun to establish an evidence base for best practice in assisting patients and families in complex decision making. Decision scientists aim to understand and clarify the concepts and techniques of shared decision making (SDM), decision support, and informed patient choice in order to ensure that patient and family perspectives shape their health care experience. Patients with serious illness and their families are faced with myriad complex decisions over the course of illness and as death approaches. If patients lose capacity, then surrogate decision makers are cast into the decision-making role. The fields of palliative care and decision science have grown in parallel. There is much to be gained in advancing the practices of complex decision making in serious illness through increased collaboration. The purpose of this article is to use a case study to highlight the broad range of difficult decisions, issues, and opportunities imposed by a life-limiting illness in order to illustrate how collaboration and a joint research agenda between palliative care and decision science researchers, theorists, and clinicians might guide best practices for patients and their families.

Introduction

Palliative care is a recognized specialty; however, evidence and expertise are often “borrowed” from diverse basic and applied fields.1–3 Because one of the central goals of palliative care is to support and assist patients and families with complex decision making,4 collaboration with decision scientists may provide important insights and evidence for palliative care practitioners. Decision scientists aim to understand, test, and clarify the concepts and techniques of shared decision making (SDM), decision support, and informed patient choice in order to ensure that patient and family perspectives shape their health care experience.5 All of these concepts have particular relevance to the field of palliative care. Developing evidence-based approaches to assist patients with life-limiting illness and their families facing multiple complex decisions over time is a palliative care research priority.6–16

A recent National Cancer Institute report, Patient-centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering, identified deficits in communication around decision making across the trajectory of cancer.17 The main research gaps identified were the need to include discussion of alternative options such as forgoing cancer treatment, surrogate decision making, and decision making as the end of life (EOL) approaches.17 Decision scientists have also identified deficits in communication due to the complexity of decision making in serious illness and have identified this as a research priority.18 Given the overlapping interests, there is an urgent need to stimulate and broaden the discussion between these fields. An important common theme is that from the time of diagnosis, patients with life-limiting illness and their families will face multiple, complex decisions that can influence their EOL experience. The purpose of this article is to use a case study to highlight the broad range of difficult decisions, issues, and opportunities imposed by a life-limiting illness in order to illustrate how collaboration and a joint research agenda between palliative care and decision science researchers, theorists, and clinicians might guide best practices for patients and their families.1–3,15

Decision Making in the Course of Serious Illness: Jane's Experience

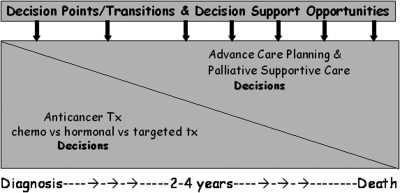

Jane is a 53-year-old mother of two teenagers and a 10-year breast cancer survivor. One day after a long drive, she experienced new, unrelieved back pain and subsequently learned that she had developed a recurrence of her breast cancer in her lumbar spine. Her oncologist recommended radiation therapy and anticancer treatment with a hormonal agent. Jane was referred for a palliative care consultation to help her with symptom management and adaptation to a now incurable disease. Over the next 3 years, Jane's breast cancer responded to several different anticancer treatments; however, each treatment eventually became ineffective at controlling the disease. Throughout these treatments and recurrences she experienced waxing and waning pain and other symptoms. Fig. 1 depicts a series of disease transition points reflecting a diminishing number of treatment choices and an increasing need to make decisions about palliative and life-prolonging treatments. Early in the course of metastatic disease, she mostly faced decisions revolving around anticancer treatments; she underwent five different anticancer treatments including investigational treatments. In an ideal world she would also have been encouraged to complete documents regarding her wishes for a surrogate decision maker and medical care if she should lose decision-making capacity. Later on, she faced decisions about whether or not to continue anticancer treatment and revisited decisions about life-prolonging treatments such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation, hospital or intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and medically administered nutrition and hydration. Ultimately, she had to decide whether she wanted to live her final days in her own home with hospice care, in a nursing home, or in a residential hospice. Jane's decisions were influenced by her values of maintaining her independence and quality of life as long as possible and not being a burden to her family. Jane and her family wanted to optimize her care so that she could live (and then die) in a way that was acceptable to her.

FIG. 1.

Disease transition points.

Contributions of decision science to decision making in serious illness

There are many decision science concepts of relevance to palliative care. The field of decision science focuses on understanding and improving the process and quality of health care decision making. Applied decision science has been described as informed patient choice, evidence-based patient choice, decision support, and SDM with the latter label emerging as the most popular.5 SDM has been defined as a relationship among patients, family, and one or more health professionals where the participants clearly establish the decision that needs to be made, discuss the options (including outcomes of options), elicit patients' values and preferences associated with those options, and engage patients or their surrogates, to the extent desired, in making and implementing a decision.19,20 SDM constitutes an ethical imperative to include patients and their families in health care decision making.21 SDM brings together the patient and family members who are experts in the biography of the illness and personal values with health care professionals who are experts in the disease and recovery process.22 A shared approach is especially important for patients such as Jane with metastatic cancer, or those with other life-limiting illnesses such as heart failure, pulmonary disease, and neurological disorders who face a series of “preference sensitive” decisions. A preference sensitive decision is one in which outcomes are uncertain and there is no clearly superior choice or right answer for every patient because the patient's values or preferences are a key element of making the “best choice.”23 Table 1 summarizes typical preference sensitive decisions faced in life-limiting illness.

Table 1.

Palliative Care and Decision Science Contributions to Complex Decision Making in Serious illness and at the End of Life

| Decision point | Contribution of palliative care | Contribution of decision science |

|---|---|---|

| Selecting a surrogate and other advance care planning decisions |

|

|

| Treatment choices when cure is not possible |

|

|

| Whether or not to be admitted to ICU and receive life-prolonging treatments or to focus on comfort care |

|

|

| Where to receive end-of-life care |

|

|

ACP, advance care planning; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ICU, intensive care unit.

It is well known that patients vary in their individual preferences for their role in decision making; some will prefer to take a more active shared role, whereas others will desire a passive role.24,25 Regardless of a patient's role preference, the stress of progressive illness may cause this role to fluctuate over time or in relation to a particular decision.26 For example, in a study of women with advanced breast cancer, 33% of 102 women wished to take an active role in the decision-making process, but that percentage increased to 43% when making a decision for second-line chemotherapy (p=0.06).27 In a study of 205 women with breast cancer, Hack and colleagues reported at the 3-year follow-up that many women regretted their role in decision making and most women preferred greater involvement in treatment planning than was afforded them.28 Also, they found that compared with women who had adopted a passive role, women who were actively involved in choosing their surgical treatment had higher overall quality of life at follow-up, higher physical and social functioning, and less fatigue.28 Health care providers can develop patients' and families' skills in SDM resulting in a preference for more active involvement.14,29 Decision sciences considers that identifying patients' preferred role, supporting them to balance harms and benefits of the options, and communicating informed values and preferences are essential components of the clinician's approach.11 For patients such as Jane, health care professionals need to afford every opportunity for the patient to take an active role in decision making to the extent the patient desires.

Other key goals of decision science are to assess decisional needs, identify strategies to relieve decision conflict, and provide effective strategies to support decision making in order to produce high-quality decisions.9 Decisional conflict is defined as a psychological state of uncertainty around which course of action to pursue.30,31 Decisional conflict occurs when choices are uncertain, involving value trade-offs between patient-judged benefits and harms and individually valued health states, when there is no clear “right choice.” Unresolved conflict may result in regret over the decision.32 The palliative care patient such as Jane is at high risk for decisional conflict due to multiple decisions that need to be made over time under the physically and psychologically stressful situation of progressive, life-threatening illness. Decision scientists have designed techniques to promote SDM and relieve decisional conflict that are collectively called “decision support.” Decision support is a clinical skill whereby patients are provided with structured support during an explicit process of decision making that includes focused counseling, and in some cases employs a patient “decision aid” to enable them to make informed health care choices.33–35

Patient decision aids are tools that help to clarify personal values and communicate information on the available options so that patients can make informed choices. Patient decision aids do not advise people to choose one option over another, nor are they meant to replace clinician consultation.36 There is strong evidence that for treatment and screening decisions, such programs have improved patients' knowledge about the options and outcomes of the options, increased accurate risk perception, resulted in a better match between values and choices, reduced decisional conflict, and reduced the number of people who remain undecided.14 Decision aids have already been developed for some of the common decisions faced in hospice and palliative care such as completing advance directives, appointing a surrogate decision maker, receiving a feeding tube, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), artificial nutrition and hydration, and place of care (Table 1). However it is unknown to what extent these tools are actually being utilized in palliative care practice. Decision aids could be helpful adjuncts to the palliative care consultation for decisions such as those faced by Jane and her family.

A key challenge for both decision scientists and palliative care clinicians is to provide the needed information in ways that patients and their families can understand. Whereas palliative care has traditionally focused on improving verbal communication,37 other communication mediums may also be useful in overcoming barriers to EOL decision making. Print, audio, video, web-based, visual, and pictorial materials can improve communication of complex information between health care professionals and patients.14,34 Pictorial representations of probabilities have been shown to communicate information better than numbers or verbal descriptions.38,39

A new frontier in decision-making science has included the use of video-based decision support interventions.40 The widespread use of web-streaming has made dissemination of video tools far easier than in the past. Video may be an ideal tool to use in EOL discussions when the interventions and subject matter discussed are unfamiliar to patients making these decisions. The medium of video allows patients to envision health states and medical interventions in a manner not easily captured with verbal communication. Recent work by decision scientists about patients experiencing dementia and cancer suggests that the verbal descriptions supplemented by video may enable individuals to better visualize the late stages of a disease and the potential impact of available options by making this complex information vital for EOL decision making more accessible.40 Video can add a sense of verisimilitude that is sometimes lacking in verbal descriptions. Video adds a textured portrait that helps clinicians communicate the possible outcomes of medical interventions across barriers that hinder accurate and informed decision making at EOL.

The use of decision coaches is another evidence-based decision support innovation that has demonstrated usefulness in assisting and involving the patient and family in decision making.41 Decision coaching is individualized support provided through the decision process by a clinician who guides a patient to consider the information relevant to a particular decision and the patient's values to reach an informed preference.42 Therapeutic relationships in palliative care are philosophically consistent with decision coaching or counseling relationships. Indeed, the typical palliative care consult often begins by clarifying what a patient understands about his or her condition followed by a discussion of the patient's goals of care surrounding symptom control and treatment options.47 Decision coaching using patient decision aids appears to improve knowledge relative to usual care and to improve satisfaction with the decision-making process relative to using patient decision aids alone.42 Jane's palliative care consult could easily combine both symptom assessment and decision coaching.

The field of palliative care has developed and refined communication techniques to support decision making but has struggled to prove its efficacy.44 Although palliative care has had success showing reductions in utilization and improvements in quality of life,45,46 other endpoints such as anxiety and symptom burden may be less amenable to change due to progressive disease. Therefore, endpoints commonly used in decision science, such as reducing decisional conflict and increasing decision quality, may be important mutable outcomes able to be effected by palliative care. For example, one trial of an intervention to support parental involvement in decisions for children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit reported that parents in the intervention group had fewer unrealistic concerns, less uncertainty about infant medical conditions, less decision conflict, more satisfaction with the decision-making process, and reported more SDM with professionals.47 Outcomes such as decision conflict, decision regret, decision preparedness, and perceived or actual involvement may more properly demonstrate the contribution of palliative care to supporting patients and families in health decision making.

Thus far, we have focused on decision science research advances that may benefit palliative care. However, remaining gaps include how to best provide decision support resources longitudinally or in the context of life-threatening illness. Palliative care has made great strides in understanding these very issues, and for this reason the discipline of palliative care has much to offer decision science.

Contributions of palliative care to advancing decision science

In advanced illness, health care decision making comprises a process of considering multiple options, with many attributes, over time, with multiple decisions makers who may each consider these options differently.17 In advanced illness, patients and families must not only cope with the physical and emotional stress of progressive disease, but must also become “expert decision makers.” The complex features of EOL decision making have perplexed decision scientists. Palliative care clinicians have learned that by starting with the patient's goals and values early in the consultation and tailoring the presented options to those goals and values, they are able to individualize and narrow the wide array of options to those most consistent with the patient's values.37,48 Burdening patients and families under stress with options that are not desired, are unrealistic, or are presented in an array may simply be overwhelming or cause decisional “paralysis” causing the patient to defer to the clinician because he or she considers the decision “too complicated” for the lay person. Tailoring and narrowing the presentation of options may diminish the possibility of being “fully informed”; however it may also increase patients and families ability to participate.48,49

As diseases advance, patients such as Jane become more ill and may lose their capacity to make decisions. Surrogate decision makers will be tasked with making difficult decisions on behalf of the patient (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Indeed, palliative care research has focused on the concept of advance directives where patients make treatment decisions in advance so that decisions made with their surrogate decision makers later in life will be consistent with their values. Research suggests that patients who complete advance directives are indeed more likely to receive care that is consistent with those preferences.50 A recent strategy in the implementation of advance directives is the Physician (Clinician) Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) paradigm program that is designed to improve the portability of advance directives across settings.51,52 The forms create an opportunity for patients to identify their wishes for “comfort measures”; limited medical treatment; full medical treatment; and whether they wish to receive specific treatments such as antibiotics and medically administered nutrition and hydration, and by what means and for what length of time. Some have recently argued that the benefits of advance directives might be more appreciated if they were conceptualized as a process to prepare patients and surrogates for late-life decision making rather than being the final word.4 Nonetheless, anticipating and explicitly formulating decisions in advance is a strategy generated by palliative care specialists to shape care to be concordant with patients values and preferences.

Another palliative care approach to aid decision making is to present the “time-limited trial” in the array of options offered to patients and families. For example, the American Society of Nephrology recommends offering a time-limited trial of dialysis for patients with renal failure considering dialysis.53 With acceptance of dialysis framed as a “time-limited trial,” the option importantly allows patients and families to undertake a course of action while giving them time to reconsider their decision and plan for transition to alternate options, if desired.54 During such a trial, there are many opportunities for health care professionals to provide effective decision support.11,33,55

Palliative care clinicians have focused particularly on how to best address the difficult topics of dying and death in advanced illness with patients and their families.56,57 Through experience and some research, palliative care clinicians have developed language to address these topics in an open and acceptable fashion.48,58 Traditional decision aids do not seem to facilitate discussions about the “taboo” subject of death, perhaps at the behest of the content reviewers and institutional review boards because of the unfounded concern that this will cause harm to the patient. The palliative care literature contains language that decision scientist could use to frame these discussions so that patients (and reviewers) will be more comfortable talking about this subject. For example, Back et al. have written about using the phrase “hope for the best, prepare for the worst” to help patients confront the idea that they may maintain hope while at the same time make difficult decisions about options that potentially result in death.59 Indeed, there are many evidence-based resources about communication that decision scientists may find helpful in constructing decision support resources that include life-limiting options and require discussion about the difficult subject of death.51,60–65

Opportunities for future collaboration

Understanding decisional needs is essential to patient and family–centered palliative care66 and the best way to provide decision support remains an important empirical question.18 Improving the complex process of decision making over time and across health care settings and designing effective strategies for providing decision support is a high priority for research in both decision science and palliative care.17,18 Decision scientists should explore the work done by the field of palliative care to gain insights in the practice of patient and family–centered care around advanced illness, and palliative care clinicians and researchers should incorporate both interventions and outcomes developed by the field of decision science into the decision support work of palliative care.

Decision science and palliative care have overlapping goals: ensuring that informed patients' and families' values guide the health decision-making process throughout the course of the illness. These two fields have grown in parallel over the last several decades resulting in considerable advances in both decision science and palliative care. It is time to integrate the lessons learned from each respective field to improve decision making in advanced illness.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Daphne Ellis for assistance with preparation of the manuscript. The authors acknowledge the following sources of funding: National Palliative Care Research Center Junior Career Award (MB), Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making (MB, JK, DDM, AV), Hartford Geriatrics Health Outcomes Research Scholar (DDM), and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality K08 Award (AEV) and National Institute for Nursing Research (R01-NR011871-01) (MB).

The authors also acknowledge Hilary Llewellyn-Thomas, Ph.D. and Annette O’Conner, Ph.D. decision science pioneers and mentors who stimulated the bridge between these fields.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Arnold RM. Jaffe E. Why palliative care needs geriatrics. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:182–183. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Childers JW. Demme R. Greenlaw J. King DA. Quill T. A qualitative report of dual palliative care/ethics consultations: Intersecting dilemmas and paradigmatic cases. J Clin Ethics. 2008;19:204–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liao S. Arnold RM. Heart failure and the future of palliative medicine. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:184. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Consensus Project. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 2nd. Brooklyn, NY: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards A. Elwyn G. Shared decision-making in health care: Achieving evidence-based patient choice. In: Edwards A, editor; Elwyn G, editor. Shared Decision-Making in Health Care: Achieving Evidence-Based Patient Choice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernal E. Marco C. Parkins S. Burderer N. Thum SD. End-of-life decisions: Family views on advance directives. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2007;24:300–307. doi: 10.1177/1049909107302296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruera E. Sweeney C. Calder K. Palmer JL. Benisch-Tolley S. Patient preferences versus physician perceptions of treatment decisions in cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2883–2885. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.11.2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Happ MB. Swigart VA. Tate JA. Hoffman LA. Arnold RM. Patient involvement in health-related decisions during prolonged critical illness. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30:361–372. doi: 10.1002/nur.20197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Legare F. O'Connor AC. Graham I. Saucier D. Côté L. Cauchon M. Paré L. Supporting patients facing difficult health care decisions: Use of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework. Can Fam Physician. 2006;52:476–477. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sahlberg-Blom E. Ternestedt B. Johansson J. Patient participation in decision making at the end of life as seen by a close relative. Nurs Ethics Int J Health Care Pro. 2000;7:296–313. doi: 10.1177/096973300000700404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sepucha K. Ozanne E. Silvia K. Partridge A. Mulley A. An approach to measuring the quality of breast cancer decisions. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stacey D. Pomey M. O'Connor AM. Graham ID. Adoption and sustainability of decision support for patients facing health decisions: An implementation case study in nursing. Implement Sci. 2006;1:17. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sullivan MD. The illusion of patient choice in end-of-life decisions. Am J Geriat Psychiat. 2002;10:365–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Connor AM. Bennett CL. Stacy D. Barry M. Col NF. Eden KB. Entwistle VA. Fiset V. Holmes-Rovner M. Khangura S. Llewellyn-Thomas H. Rovner D. Cochrane Review. 3. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2004. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liao S. Arnold RM. Good communication: The essence and reward of palliative medicine. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:956–957. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.9930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tulsky JA. Fischer GS. Rose MR. Arnold RM. Opening the black box: How do physicians communicate about advance directives? Ann Inter Med. 1998;129:441–449. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-6-199809150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Epstein R. Street R., Jr . Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007. NIH Publication No. 07-6225. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnato AE. Llewellyn-Thomas H. Peters EM. Siminoff L. Collins ED. Barry MJ. Communication and decision making in cancer care: Setting research priorities for decision support/patient decision aids. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:626–634. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07306788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray MA. Miller T. Fiset V. O'Connor AM. Jacobsen MJ. Decision support: Helping patients and families to find a balance at the end of life. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2004;10:270–277. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2004.10.6.13268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheridan SL. Harris RP. Woolf SH. Shared decision making about screening and chemoprevention. A suggested approach from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elwyn G. Edwards A. Kinnersley P. Grol R. Shared decision making and the concept of equipoise: The competences of involving patients in healthcare choices. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:892–899. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tattersall RL. The expert patient: a new approach to chronic disease management for the twenty-first century. Clin Med. 2002;2:227–229. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.2-3-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blank T. Graves K. Sepucha K. Llewellyn-Thomas H. Understanding treatment decision making: Contexts, commonalities, complexities, and challenges. Ann Behav Med. 2006;32:211–217. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3203_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Degner LF. Kristjanson LJ. Bowman D. Sloan JA. Carriere KC. O'Neil J. Bilodeau B. Watson P. Mueller B. Information needs and decisional preferences in women with breast cancer. JAMA. 1997;277:1485–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Degner LF. Sloan J. Decision making during serious illness: What role do patients really want to play? J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:941–950. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Llewellyn-Thomas HA. Measuring patients' preferences for participating in health care decisions: Avoiding invalid observations. Health Expect. 2006;9:305–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00418.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grunfeld EA. Maher EJ. Browne S. Ward P. Young T. Vivat B. Walker G. Wilson C. Potts HW. Westcombe AM. Richards MA. Ramirez AJ. Advanced breast cancer patients' perceptions of decision making for palliative chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1090–1098. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.9208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hack TF. Degner LF. Watson P. Sinha L. Do patients benefit from participating in medical decision making? Longitudinal follow-up of women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15:9–19. doi: 10.1002/pon.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belkora J. Franklin L. O'Donnell S. Ohnemus J. Stacey D. Adaptation of consultation planning for Native American and Latina women with breast cancer. J Rural Health. 2009;25:384–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Connor A. Decisional Conflict Scale. 4th. Ottawa: Ottawa Health Research Institute; 1999. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Connor A. Decisional conflict. In: McFarlan G, editor. Nursing Diagnosis and Intervention. Toronto: Mosby; 1997. pp. 486–496. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brehaut JC. O'Connor AM. Wood TJ. Hack TF. Siminoff L. Gordon E. Feldman-Stewart D. Validation of a decision regret scale. Med Decis Making. 2003;23:281–292. doi: 10.1177/0272989X03256005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feldman-Stewart D. Brennenstuhl S. McIssac K. Austoker J. Charvet A. Hewitson P. Sepucha KR. Whelan T. A systematic review of information in decision aids. Health Expect. 2007;10:46–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Connor AM. Wennberg JE. Legare F. Llewellyn-Thomas HA. Moulton BW. Sepucha KR. Sodano AG. King JS. Toward the 'tipping point': decision aids and informed patient choice. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:716–725. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waljee JF. Rogers MA. Alderman AK. Decision aids and breast cancer: Do they influence choice for surgery and knowledge of treatment options? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1067–1073. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holmes-Rovner M. Nelson WL. Pignone M. Elwyn G. Rovner DR. O'Connor AM. Coulter A. Correa-de.Araujo R. Are patient decision aids the best way to improve clinical decision making? Report of the IPDAS Symposium. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:599–608. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07307272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Back AL. Arnold RM. Baile WF. Fryer-Edwards KA. Alexander SC. Barley GE. Gooley TA. Tulsky JA. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:453–460. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz LM. Woloshin S. Welch HG. Using a drug facts box to communicate drug benefits and harms: two randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:516–527. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-8-200904210-00106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwartz LM. Woloshin S. Welch HG. The drug facts box: Providing consumers with simple tabular data on drug benefit and harm. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:655–662. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07306786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.El-Jawahri A. Podgurski LM. Eichler AF. Plotkin SR. Temel JS. Mitchell SL. Chang Y. Barry MJ. Volandes AE. Use of video to facilitate end-of-life discussions with patients with cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:305–310. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.7502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Connor AM. Stacey D. Legare F. Coaching to support patients in making decisions. BMJ. 2008;336:228–229. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39435.643275.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stacey D. Bennett C. Kryworuchko J. Murray M. What is the contribution of decision coaching to prepare patients for shared decision making when evaluated in randomized controlled trials of patient decision aids?; Paper presented at: 5th International Shared Decision Making Conference; Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morrison RS. Meier DE. Clinical practice. Palliative care. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2582–2590. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp035232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zimmermann C. Riechelmann R. Krzyzanowska M. Rodin GC. Tannock I. Effectiveness of specialized palliative care: A systematic review. JAMA. 2008;299:1698–1709. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.14.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bakitas M. Lyons K. Hegel M. Balan S. Brokaw FC. Seville J. Hull JG. Li Z. Tosteson TD. Byock IR. Ahles TA. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morrison RS. Penrod JD. Cassel JB. Caust-Ellenbogen M. Litke A. Spragens L. Meier DE. Palliative Care Leadership Centers' Outcomes Group Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch of Int Med. 2008;168:1783–1790. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Penticuff JH. Arheart KL. Effectiveness of an intervention to improve parent-professional collaboration in neonatal intensive care. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2005;19:187–202. doi: 10.1097/00005237-200504000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Back A. Arnold R. Tulsky JA. Mastering Communication with Seriously Ill Patients: Balancing Honesty with Empathy Hope. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schneider A. Korner T. Mehring M. Wensing M. Elwyn G. Szecsenyi J. Impact of age, health locus of control and psychological co-morbidity on patients' preferences for shared decision making in general practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61:292–298. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bakitas M. Ahles T. Skalla K. Brokaw FC. Byock I. Hanscom B. Lyons KD. Hegel MT. ENABLE project team: Proxy perspectives regarding end-of-life care for persons with cancer. Cancer. 2008;112:1854–1861. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meier DE. Beresford L. POLST offers next stage in honoring patient preferences. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:291–295. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.9648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hickman SE. Nelson CA. Moss AH. Hammes BJ. Terwilliger A. Jackson A. Tolle SW. Use of the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) paradigm program in the hospice setting. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:133–141. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moss AH. Revised dialysis clinical practice guideline promotes more informed decision-making. Clin J Am Soc Nephro. 2010;5:2380–2383. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07170810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Knight SJ. Emanuel L. Processes of adjustment to end-of-life losses: A reintegration model. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:1190–1198. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chung C. Carlson R. Goals and objectives in the managment of metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist. 2003;8:514–520. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.8-6-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Field MJ. Cassel CK. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Foley KM. Gelband H. Improving Palliative Care for Cancer. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Medicine and National Research Council; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Back AL. Arnold RM. Baile WF. Tulsky JA. Barley GE. Pea RD. Fryer-Edwards KA. Faculty development to change the paradigm of communication skills teaching in oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1137–1141. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Back AL. Arnold RM. Quill TE. Hope for the best, and prepare for the worst. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:439–443. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-5-200303040-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Casarett DJ. Quill TE. “I'm not ready for hospice”: Strategies for timely and effective hospice discussions. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:443–449. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-6-200703200-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goodlin SJ. Quill TE. Arnold RM. Communication and decision-making about prognosis in heart failure care. J Card Fail. 2008;14:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Quill TE. Perspectives on care at the close of life. Initiating end-of-life discussions with seriously ill patients: Addressing the “elephant in the room.”. JAMA. 2000;284:2502–2507. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Quill TE. Dying and decision making—evolution of end-of-life options. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2029–2032. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Quill TE. Arnold R. Back AL. Discussing treatment preferences with patients who want “everything.”. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:345–349. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-5-200909010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Quill TE. Arnold RM. Platt F. “I wish things were different”: Expressing wishes in response to loss, futility, and unrealistic hopes. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:551. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-7-200110020-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Egan KA. Labyak MJ. Hospice Palliative care: A model for quality end-of-life care. In: Ferrell BR, editor; Coyle N, editor. Textbook of Palliative Nursing. 2nd. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 13–46. [Google Scholar]

- 67.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Palliative Care V.I.2006, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. New York: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Green MJ. Levi BH. Pennsylvania State University. Making your wishes known: Planning your medical future. 2008. http://pennstatehershey.org/web/humanities/home/resources/advancedirectives. [Aug 23;2011 ]. http://pennstatehershey.org/web/humanities/home/resources/advancedirectives

- 69.Fraser Health Authority. Planning in advance for your future healthcare choices. 2007. http://www.fraserhealth.ca/ [Aug 23;2011 ]. http://www.fraserhealth.ca/

- 70.Alberta Health Services. My voice—Planning ahead. www.calgaryhealthregion.ca/programs/advancecareplanning/ [Aug 23;2011 ]. www.calgaryhealthregion.ca/programs/advancecareplanning/

- 71.Advance Care Planning (ACP) Decisions Patient Education Videos. www.ACPdecisions.org. [Aug 23;2011 ]. www.ACPdecisions.org

- 72.Health Dialog: Looking ahead: Choices for medical care when you are seriously ill. http://www.healthdialog.com/Main/Personalhealthcoaching/Shared-Decision-Making/Looking-Ahead_OLD. [Aug 23;2011 ]. http://www.healthdialog.com/Main/Personalhealthcoaching/Shared-Decision-Making/Looking-Ahead_OLD

- 73.National Initiative for Care of the Elderly. Capacity & Consent (pocket tool format) http://www.nicenet.ca/list.aspx?menu=43&app=198&cat1=571&tp=9&ik=no. [Aug 23;2011 ]. http://www.nicenet.ca/list.aspx?menu=43&app=198&cat1=571&tp=9&ik=no

- 74.The American Bar Association. Health care decision making resources. http://www.americanbar.org/groups/law_aging/resources/health_care_decision_making.html. [Aug 23;2011 ]. http://www.americanbar.org/groups/law_aging/resources/health_care_decision_making.html

- 75.Ottawa Patient Decision Aid Research Group: A to Z inventory. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/AZinvent.php. [Aug 23;2011 ]. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/AZinvent.php

- 76.Healthwise Knowledgebase. www.healthlinkbc.ca/kb/ [Aug 23;2011 ]. www.healthlinkbc.ca/kb/

- 77.Health Dialog. www.healthdialog.com. [Aug 23;2011 ]. www.healthdialog.com

- 78.Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health Care System: Center for shared decision making. http://patients.dartmouth-hitchcock.org/shared_decision_making.html. [Aug 23;2011 ]. http://patients.dartmouth-hitchcock.org/shared_decision_making.html

- 79.Ottawa Patient Decision Aid Research Group. Making choices: The use of intubation and mechanical ventilation for severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/das/COPD.pdf. [Aug 23;2011 ]. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/das/COPD.pdf

- 80.Healthwise: Should I stop kidney dialysis? www.healthwise.net/cochranedecisionaid/Content/StdDocument.aspx?DOCHWID=tu6095. [Aug 23;2011 ]. www.healthwise.net/cochranedecisionaid/Content/StdDocument.aspx?DOCHWID=tu6095

- 81.Kryworuchko J. Understanding your options: Planning care for critically ill patients in the intensive care unit. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/das/Critically_Ill_Decision_Support.pdf. [Aug 23;2011 ]. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/das/Critically_Ill_Decision_Support.pdf

- 82.Healthwise: Should I have artificial hydration nutrition? www.healthwise.net/cochranedecisionaid/Content/StdDocument.aspx?DOCHWID=tu4431. [Aug 23;2011 ]. www.healthwise.net/cochranedecisionaid/Content/StdDocument.aspx?DOCHWID=tu4431

- 83.Murray MA. When you need extra care, should you receive it at home or in a facility? http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/decaids.html#poc. [Aug 23;2011 ]. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/decaids.html#poc