Abstract

Objective

Feedback is a technique used in medical education to help develop and improve clinical skills. A comprehensive review article specifically intended for the emergency medicine (EM) educator is lacking, and it is the intent of this article to provide the reader with an in-depth, up-to-date, and evidence-based review of feedback in the context of the EM clerkship.

Methods

The review article is organized in a progressive manner, beginning with the definition of feedback, the importance of feedback in medical education, the obstacles limiting the effective delivery of feedback, and the techniques to overcome these obstacles then follows. The article concludes with practical recommendations to implement feedback in the EM clerkship. To advance the literature on feedback, the concept of receiving feedback is introduced.

Results

The published literature regarding feedback is limited but generally supportive of its importance and effectiveness. Obstacles in the way of feedback include time constraints, lack of direct observation, and fear of negative emotional responses from students. Feedback should be timely, expected, focused, based on first-hand data, and limited to behaviors that are remediable. Faculty development and course structure can improve feedback in the EM clerkship. Teaching students to receive feedback is a novel educational technique that can improve the feedback process.

Conclusion

Feedback is an important educational technique necessary to improve clinical skills. Feedback can be delivered effectively in the EM clerkship.

INTRODUCTION

“In the setting of clinical medical education, feedback refers to information describing students' … performance in a given activity that is intended to guide their future performance in that same or in a related activity. It is a key step in the acquisition of clinical skills, yet feedback is often omitted or handled improperly in clinical training.1”

These are words from Jack Ende's seminal 1983 article regarding feedback, and they remain true more than 25 years later.1 The emergency medicine (EM) clerkship has been recognized as an important arena for undergraduate medical education, and, subsequently, the number of medical schools with a mandatory experience has increased exponentially.2,3 To reach our potential as educators, we must embrace feedback and learn to deliver it effectively.2,3 The goals of this review are to define feedback and to highlight its importance. We also identify obstacles and review guidelines for effective feedback in the emergency department (ED). We make recommendations regarding the implementation of feedback in your clerkship. Finally, we will introduce the concept of teaching students to receive feedback.

Defining Feedback

Feedback is the process by which the teacher observes a student performing an activity, analyzes the performance, and then provides information back to the student that will enable the student to perform the same activity better in the future. This process is critical to the development of clinical skills.1

Some have categorized feedback by the time frame in which it is delivered.2,4 “Brief feedback” involves focused, useful suggestions for improvement that occur during the course of a shift. For example, a student who auscultates breath sounds anteriorly but fails to have the patient sit up and appreciate wheezing in the posterior lung segments would benefit from brief feedback. “Formal feedback” is delivered at the end of a clinical shift. This is more extensive than brief feedback, but still focused on one or two specific skills. Finally, “major feedback” would occur at a scheduled mid-rotation meeting with a clerkship director or mentor.2,4

When defining feedback, it is critical to distinguish it from evaluation. Feedback begins with a formative assessment by the teacher through observation. The information obtained from this assessment is then delivered back to the learner. The primarily intention of this process is to provide information that the learner can incorporate to improve his or her skills. Evaluation, conversely, is a summative assessment. The purpose is to make a judgment about performance, usually against some standard, and to document this judgment. Evaluation may take the form of a grade or skills report. It is not primarily intended to improve the learner's skill.5

Importance of Feedback

Professionals from fields as diverse as business and medicine agree that feedback is important in the development of expertise.1 Feedback can reinforce good behavior, correct mistakes, and provide direction for improvement.1,6–8 Successful athletes and musicians use coaches to engage in goal setting, practice, and feedback. This active engagement, relying heavily on feedback, is termed deliberate practice. The level of expertise developed through deliberate practice is higher than that reached by passive experience without feedback.9–11

The educational literature supports the notion that feedback has a powerful influence on learning and achievement. A large meta-analysis of student achievement identified 100 influential factors, with feedback ranked in the top 10.12 Further analysis suggests that constructive feedback scored higher than generalized positive reinforcement.12

The literature that directly evaluates feedback as it relates to undergraduate medical education is limited but generally supportive. Feedback has been demonstrated to improve clinical skills. Students given feedback on videotaped history and physical examinations performed significantly better on subsequent interviews compared with students who received no feedback.13 Research from high-fidelity simulation has also demonstrated the importance of feedback to the development of clinical skills.14 Finally, in a limited scope, feedback has been shown to improve physician judgment.15

Students lacking proper feedback may turn to unreliable methods of assessment. Self-assessment is one such method.1 A systematic review of the literature found that physicians have limited ability to self-assess accurately.16 The reason for this is probably a complicated mix of cognitive, biologic, and social factors.17 Students lacking feedback may self-assess or alternatively attempt analysis of external cues as a source of assessment. When this occurs, it is possible that the cues will be misinterpreted.1 A busy faculty member may only allow a student to complete half of a laceration repair before taking over the procedure to save time. Without feedback, the student may interpret the interruption as a cue that the repair was inadequate or faulty, when in fact the student was working at a skill level expected for his or her level of training. Alternative assessments to feedback can foster a false sense of competency, or conversely, a feeling of inadequacy that may be inaccurate.

Obstacles to Effective Feedback

Medical students have long perceived that the feedback they receive on most clinical rotations is lacking in quantity and quality.18,19 Although data specific to EM student clerkships are lacking, a recent report from the perspective of EM residents concludes that feedback in the ED occurs infrequently.20,21

A variety of barriers to the delivery of feedback contribute to its perceived lack of occurrence. Time constraints in the ED have been noted to limit the delivery of feedback in many ways,21 notably, the direct observation of clinical skills.22,23 Observation is the foundation of a formative assessment and, without this, feedback is unlikely to occur or to be of high quality.1 Unfortunately, a lack of direct observation is a long-standing and significant problem.1,24 One study found that learners spend less than 1% of their time in the ED under direct observation.24

Another obstacle to feedback is the teacher's reluctance to deliver it.1,6,21 Teachers report that their hesitancy stems from the fear of a negative emotional response from students who receive feedback on poor performance.21 Such a response may affect the student–teacher relationship, the teacher's popularity, or even the teacher's evaluation.1,21 The reluctance of teachers to deliver feedback can also be attributed to a self-perceived lack of skill in observation and feedback.21,23

These obstacles are significant but not insurmountable. Effective feedback is highly desired by learners.25 The following guidelines are provided to help educators overcome obstacles of effective feedback.

Guidelines for Delivery of Effective Feedback in the ED

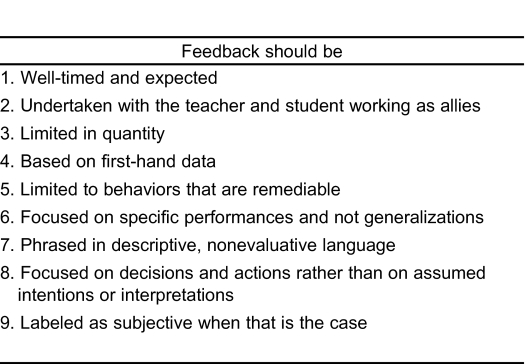

Feedback can fail when the student becomes defensive or embarrassed. To avoid this scenario, the students must receive information in a manner that enables them to accept it as nonevaluative and with the intention to improve clinical skills. Ende1 has adopted guidelines for giving feedback from other professions, such as business management and education (Table). Medical educators have advocated variations of these guidelines.5,6,8,26 One attempt to study these guidelines confirmed their effectiveness.27 These guidelines can be incorporated into the EM clerkship to optimize feedback delivery.

Well-Timed and Expected Feedback

Students should be informed that feedback will be part of the clerkship during orientation. Students should be told to expect feedback at the conclusion of clinical shifts but not to be surprised if it is delivered during patient care as well. Timely feedback is ideal, and anticipation of it will prevent confusion from evaluation or reprimand. To this end, experts recommend starting the feedback process with a phrase that identifies it as such. Something as simple as, “Now I am going to give you some feedback,” will often suffice.

Feedback with the Teacher and Student as Allies

Feedback delivered by a mentor, for whom the student has respect and trust, is more likely to be effective than that delivered by a teacher with no established relationship with the student. The typical student in an EM clerkship is likely to encounter numerous teachers, perhaps a new one every shift, and in that case, other techniques to develop alliances must be developed. Students should be encouraged to ask for feedback. This will align the teacher and student with the common goal of improvement in clinical skills. Feedback cards that students or residents present to their preceptors have been shown to improve the quantity of feedback delivered by supervising physicians.21,28–30 If both parties feel obligated to complete the cards, they will develop a union that fosters feedback. Many educators recommend asking the student for a self-assessment before delivering feedback. This is another way to foster a teaching relationship.

Limiting Quantity of Feedback

Students are not likely to be able to process large amounts of feedback at one time. For this reason, it is best to focus feedback into specific categories. The broad domains of knowledge, skill, and attitude are a good place to start.31 Clinical skills can be further specified through the use of the Association of American Medical Colleges clinical skills competencies. These include history taking, patient examination, patient engagement and communication skill, professionalism, diagnosis, clinical intervention, and prognosis.32

Re-evaluate the skill in question and ensure that the student has improved before moving on to the next skill. During a typical shift, a student can be expected to present multiple patients to the attending physician. If the student appears to have incorporated the attending's suggestions into subsequent patient encounters, then it would be appropriate to move on to another clinical skill.

Feedback Based on First-Hand Data

Direct observation of a clinical skill is the ideal way to assess a student before providing feedback.1,23 This does not have to be a prolonged observation every time. It can be focused to a simple task such as delivery of discharge instructions. In this example, a brief direct observation can be used to provide feedback in competencies such as patient communication. Indirect observations are less ideal. Listening to a student's presentation as a means to assess their history-taking ability is an example of an indirect observation. To better assess history-taking ability, it is imperative to be in the room while the information is gathered. In this example, distinguishing history-taking skills from presentation skills can be difficult. Feedback is least valuable when a clerkship director delivers feedback that another faculty member has formulated. This is termed second-hand feedback, and it is complicated by delays and inaccuracies.1 It also may appear to be more summative than formative.

Limiting Feedback to Remediable Behaviors

Feedback should focus on skills that can be improved with appropriate guidance and direction. A student who has difficulty interacting and communicating with a patient may appear to lack empathy or compassion. Although this may or may not be true, directing the student to work on empathy is unlikely to change behavior and improve future performance. The student should be given specific instructions on how to improve communication. Eye contact, proper introduction, and attentiveness are aspects of “etiquette-based medicine” that are more easily taught than is empathy.33

Focusing Feedback on Specific Performances

Students are more likely to understand and appreciate feedback if it can be related to a specific performance. To this end, if an action plan can be initiated to improve this performance, it will help promote skill development. An inefficient student will not benefit from simply being told to work faster. The student may just be saving all his documentation for the end of the encounter. Appropriate feedback in this example would be to advise the student to improve on efficiency by working on documentation while tests are pending and to prepare in advance for discharges or admissions.

Phrasing Feedback in Descriptive, Nonevaluative Language

Feedback is optimal when it is delivered with descriptive and nonevaluative language. Too often students are told that they are excellent. Even when evaluating a specific clinical skill, such as a procedure, they are often told they did a perfect job. These terms are problematic on two fronts. First, they do not provide a framework that allows knowledge about how to repeat or improve the same performance in the future. Second, such general terms can be confused with an evaluation of the person and not the skill. This becomes especially troublesome when feedback is not positive.

Students who learn to equate feedback of a skill with a judgment of their own personal worth may become defensive, argumentative, or dismissive to any feedback that is not positive. This emotional response interferes with learning. The student with a limited differential diagnosis should not be told that it is simply poor and could be better. It would be more helpful to describe the student's diagnosis as accurate for what was considered, but limited in its scope. Suggestions for improvement can then be provided. The student may improve by considering complaints in an organ-systems approach. Similarly, a student with an extensive differential diagnosis will not benefit from being told it is excellent. It would serve them better to hear that their differential is advanced for their level of training by the inclusion of multiple organ systems and atypical presentations of diseases. This will reinforce what was done well and encourage it to be repeated in the future. Furthermore, the student should be challenged to continue to improve. One way to do this may to be asking the student to develop a tiered approach that considers likelihood and severity of disease.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR IMPLEMENTING FEEDBACK

Faculty Development

Improving feedback in your EM clerkship begins with faculty development to ensure their understanding of the basic principles of effective feedback outlined earlier. Faculty are unlikely to have learned these principles during residency or even subsequently. Furthermore, they may have even learned to avoid delivering feedback, especially when it is negative. To this end, faculty may deliver only positive feedback, as it is easy to do, rarely uncomfortable, and not often associated with a negative emotional response. The delivery of positive feedback may even increase the likelihood that students evaluate the faculty member highly. This is not in the best interest of the student and must be understood by all faculty members.

A variety of faculty-development methods can be considered. Providing faculty reading material is a simple and cost-efficient method, but ensuring compliance with the reading is difficult. Lectures during resident conference have the advantage of accountability but as a form of passive learning, may not effectively reach adult learners. More-formal faculty-development courses that include a combination of lectures, small groups, and active role- playing have literature to support their effectiveness.34,35 However, the cost of these programs and the time commitment may be limiting. Direct observation of faculty themselves in the ED by more-senior educators is another option to consider.

Regardless of the format of the initial faculty-development activity, it is important to have both ongoing reminders and monitoring. Student evaluations of faculty should inquire about constructive feedback. It may also be beneficial to end the clerkship with an anonymous debriefing between the students and an administrator. Further faculty-development activities can be directed based on the information gathered. Global deficiencies may become evident, or individuals may need specific help improving their feedback skills.

Course Structure

Course structure can be used to improve feedback in the clerkship. A discussion of feedback during orientation will help ensure that students differentiate feedback from evaluation, expect feedback, and even seek it out. It may be useful to provide students with multiple shifts with the same faculty member. This design gives the teacher more time to assess deficiencies, provide feedback, and monitor for improvement in skill.

The use of feedback cards has also been mentioned as a tool that can be implemented to improve feedback.28–30 Feedback cards provide structure that ensures that feedback is frequent, expected, timely, and solicited. These cards can be designed to meet the needs of an individual clerkship. We recommend using a competency-specific system in EM to add focus.36

Receiving Feedback

Most of the education literature focuses on improving the delivery of feedback by the teacher. Although this is important, we believe that focusing on this alone will lead to less than optimal results. Concentration must focus on teaching students how to ask for and accept feedback.

It is currently assumed that students are looking for feedback, able to recognize it, able to cope with negative feedback, and able to apply feedback effectively to improve clinical skills. This assumption is faulty and unfair to students. Many medical students have excelled at all educational activities throughout their lives, and it may be that the only feedback they have received in the past has been positive. It is therefore possible that they have not developed the skill to deal with negative feedback.

Ideally, receiving feedback should be taught to medical students early in their education. The skill of receiving feedback is important in all clerkships. A transitional course used at many medical schools before the start of third-year clerkships is one option.37

A better option may be during introduction to clinical medicine courses. These courses typically span the first and/or second year of medical school. The longitudinal nature of these courses may provide more time to develop fully the skill of receiving feedback than may a transitional course. Clerkship orientation may be a good place to reinforce this concept.

CONCLUSION

Feedback is the delivery of information obtained from observing and analyzing a student's performance that is intended to improve their performance in the future. It is through this process that clinical skills are developed and fine-tuned. Feedback should be timely, expected, focused, based on first-hand data, and limited to behaviors that are remediable. Faculty development and course structure can improve feedback in your clerkship. Teaching students to receive feedback is a novel educational technique that can contribute to the development of clinical skills as well.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Jeffrey Druck, MD

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Table.

Guidelines for effective faculty feedback to medical students.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA. 1983;250:777–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manthey DE, Coates WC, Ander DS, et al. Report of the task force on national fourth year medical student emergency medicine curriculum guide. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:E1–E7. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coates WC. An educator's guide to teaching emergency medicine to medical students. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:300–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2004.tb02215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Branch WT, Paranjape A. Feedback and reflection: teaching methods for clinical settings. Acad Med. 2002;77:1185–1188. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200212000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wald DA, Choo EK. Providing feedback in the emergency department. In: Rogers RL, editor. Practical Teaching in Emergency Medicine. Vol. 71 Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing;; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.King J. Giving feedback. BMJ. 1999;318:2. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood BP. Feedback: a key feature of medical training. Radiology. 2000;215:17–19. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.1.r00ap5917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chowdhury RR, Kalu G. Learning to give feedback in medical education. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;6:243–247. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ericsson KA, Krampe RT, Tesch-Romer C. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol Rev. 1993;100:363–406. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ericsson KA. Deliberate practice and the acquisition and maintenance of expert performance in medicine and related domains. Acad Med. 2004;79:S70–S81. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200410001-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ericsson KA. Deliberate practice and acquisition of expert performance: a general overview. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:988–994. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hattie J, Timperley H. The power of feedback. Rev Ed Res. 2007;77:81–112. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheidt PC, Lazortiz S, Ebbeling WL, et al. Evaluation of system providing feedback to students on videotaped patient encounters. J Med Educ. 1986;61:585–590. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198607000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Issenber SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, et al. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2005;27:10–28. doi: 10.1080/01421590500046924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wigton RS, Patil KD, Hoellerich VL. The effect of feedback in learning clinical diagnosis. J Med Educ. 1986;61:816–822. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198610000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, et al. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systemic review. JAMA. 2006;;296:1094–1102. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eva KW, Reghler G. “I'll never play professional football” and other fallacies of self-assessment. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28:14–19. doi: 10.1002/chp.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gil D, Heins M, Jones PB. Perceptions of medical school faculty members and students on clinical clerkship feedback. J Med Educ. 1984;59:856–864. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198411000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hekelman FP, Vanek E, Kelly K, et al. Characteristics of family physicians' clinical teaching behaviors in the ambulatory setting: a descriptive study. Teach Learn Med. 1993;1:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wald DA, Manthey DE, Kruus L, et al. The state of the clerkship: a survey of emergency medicine clerkship directors. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:629–634. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yarris LM, Linden JA, Hern HG, et al. Attending and resident satisfaction with feedback in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:S76–S81. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atzema C, Bandiera G, Schull MJ. Emergency department crowding: the effect on resident education. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;;45:276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fromme HB, Karani R, Downing SM. Direct observation in medical education: a review of the literature and evidence for validity. Mt Sinai J Med. 2009;76:365–371. doi: 10.1002/msj.20123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chisholm CD, Whenmouth LF, Daly EA, et al. An evaluation of emergency medicine resident interaction time with faculty in different teaching venues. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:149–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thurgur L, Bandiera G, Lee S, Tiberius R. What do emergency medicine learners want from their teachers? A multicenter focus group analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:856–861. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richardson BK. Feedback. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:1283e1–1283e15. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hewson MG, Little M. Giving feedback in medical education: verification of recommended techniques. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:111–116. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paukert JL, Richards ML, Olney C. An encounter card system for increasing feedback to students. Am J Surg. 2002;183:300–304. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00786-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richards ML, Paukert JL, Downing SM, et al. Reliability and usefulness of clinical encounter cards for a third-year surgical clerkship. J Surg Res. 2007;140:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kogan JR, Shea JA. Implementing feedback cards in core clerkships. Med Educ. 2008;42:1071–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Association of American Medical Colleges. Learning objectives for medical student education: guidelines for medical schools. Association of American Medical Colleges Web site. Available at: http://www.aamc.org. Accessed June 10, 2010.

- 32.Corbett EC, Berkow RL, Bernstein LB, et al. Recommendations for clinical skills curricula for undergraduate medical education. Association of American Medical Colleges Web site. Available at: http://www.AAMC.org. Accessed July 26, 2011.

- 33.Kahn Michael W. Etiquette-based medicine. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0801863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME guide no. 8. Med Teach. 2006;28:497–526. doi: 10.1080/01421590600902976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marks MB, Wood TJ, Nuth J, et al. Assessing change in clinical teaching skills: are we up for the challenge? Teach Learn Med. 2008;20:288–294. doi: 10.1080/10401330802384177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernard AB, Khandelwal SK. A competency-specific feedback card system in the emergency medicine clerkship; Poster presented at: SAEM Midwest Conference; September 21, 2009; Ann Arbor, MI. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poncelet A, O'Brien B. Preparing medical students for clerkships: a descriptive analysis of transitional courses. Acad Med. 2008;83:444–451. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816be675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]