Abstract

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is recognized as a serious global health problem that is characterized by high blood sugar levels. Type 2 DM is more common in diabetic populations. In this type of DM, inhibition of α-glucosidase is a useful treatment to delay the absorption of glucose after meals. As a megabiodiversity country, Indonesia still has a lot of potential unexploited forests to be developed as a medicine source, including as the α-glucosidase inhibitor. In this study, we determine the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of 80% ethanol extracts of leaves and twigs of some plants from the Apocynaceae, Clusiaceae, Euphorbiaceae, and Rubiaceae. Inhibitory activity test of the α-glucosidase was performed in vitro using spectrophotometric methods. Compared with the control acarbose (IC50 117.20 μg/mL), thirty-seven samples of forty-five were shown to be more potent α-glucosidase inhibitors with IC50 values in the range 2.33–112.02 μg/mL.

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is the most common endocrine disease worldwide. About 173 million people suffer from diabetes mellitus. The number of people with diabetes mellitus will more than double over the next 25 years to reach a total of 366 million by 2030 [1]. In 2000, Indonesia is ranked the fourth largest number of people with DM, after India, China, and the United States, which is about 8.4 million people. The amount is expected to rise to 21.3 million in 2030 [2].

DM consists of several types, one of which is noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (type 2 DM). This type of DM is more common, reaching 90–95% of the population with DM [3]. This increasing trend in type 2 DM has become a serious medical concern worldwide that prompts every effort in exploring for new therapeutic agents to stem its progress.

In type 2 DM, inhibition of α-glucosidase therapy is beneficial to delay absorption of glucose after a meal [4]. α-glucosidase plays a role in the conversion of carbohydrates into glucose. By inhibiting α-glucosidase, glucose levels in the blood can be returned within normal limits [5].

Natural resources provide a huge and highly diversified chemical bank from which we can explore for potential therapeutic agents by bioactivity-targeted screenings [6]. As a megabiodiversity country, Indonesia still has a lot of potential unexploited forests to be developed as a source phytopharmaca or modern medicine [7]. Opportunity exploration of medicinal plants is still very wide open in line with the development of herbal industry, herbal medicine, and phytopharmaca. Therefore, researchers try to explore the potential antidiabetic agents with the mechanism of action of α-glucosidase inhibition in several plant species from four families: Apocynaceae, Clusiaceae, Euphorbiaceae, and Rubiaceae. The four families were chosen because members of some species have been scientifically proven to have antidiabetic activity. Based on the theory of kinship through a systematic approach to plant (chemotaxonomy), plants with the same family generally have similar chemical content, so it may just have the same potential for the treatment of a disease [8].

2. Method and Material

2.1. Plant Material

The stem bark and leaves of plants material were collected in November 2010 and identified by Center for Plant Conservation-Bogor Botanical Garden.

2.2. Extraction

Each dried powdered of wood bark, twig and leaves (20 g) were extracted by reflux with ethanol 80% then evaporated.

2.3. Inhibition Assay for α-Glucosidase Activity

The inhibition of α-glucosidase activity was determined using the modified published method [9]. One mg of α-glucosidase (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was dissolved in 100 mL of phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) containing 200 mg of bovine serum albumin (Merck, German). The reaction mixture consisting 10 μL of sample at varying concentrations (0.52 to 33 μg/mL) was premixed with 490 μL phosphate buffer pH 6.8 and 250 μL of 5 mM p-nitrophenyl α-D-glucopyranoside (Sigma-Aldrich, Switzerland). After preincubating at 37°C for 5 min, 250 μL α-glucosidase (0.15 unit/mL) was added and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 2000 μL Na2CO3 200 mM. α-glucosidase activity was determined spectrophotometrically at 400 nm on spectrophotometer UV-Vis (Shimadzu 265, Jepang) by measuring the quantity of p-nitrophenol released from p-NPG. Acarbose was used as positive control of α-glucosidase inhibitor. The concentration of the extract required to inhibit 50% of α-glucosidase activity under the assay conditions was defined as the IC50 value.

2.4. Kinetics of Inhibition against α-Glucosidase

Inhibition modes of sample that had the best α-glucosidase inhibiting activity in Clusiaceae, Euphorbiaceae, and Rubiaceae were measured with increasing concentration of p-nitrophenyl α-D-glucopyranoside as a substrate in the absence or presence of ethanolic extract at different concentrations. Inhibition type was determined by the Lineweaver-Burk plots analysis of the data, which were calculated from the result according to the Michaelis-Menten kinetics.

2.5. Phytochemistry Test

In this research we performed phytochemistry test which consists of alkaloid test with Mayer, Dragendorff, and Bouchardat reagents; Flavonoid test with Shinoda and Wilson Töubock reaction; tannin test with gelatin test, gelatin-salt test, and test with ferrous (III) chloride; glycoside test with Molisch reaction; saponin test with honeycomb froth test; anthraquinone test with Bornträger reaction; terpenoid test with Liebermann-Burchard reagent.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Phytochemistry Test

Compounds with α-glucosidase inhibitory activity were preliminary identificated by the existence of alkaloid, terpene, saponin, tannin, glycoside, flavonoid, and quinone (Table 1).

Table 1.

Phytochemical screening of 80% ethanol extracts from some plants of Apocynaceae, Clusiaceae, Euphorbiaceae, and Rubiaceae.

| Simplicia | Chemical contents | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloid | Flavonoid | Terpenoid | Tannin | Glycoside | Saponin | Anthraquinone | |

| Apocynaceae | |||||||

| Beaumontia multiflora Teijsm. & Binn. Folium | + | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Beaumontia multiflora Teijsm. & Binn. Cortex | − | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| Carissa carandas L. Folium | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Carissa carandas L. Cortex | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| Ochrosia citrodora Lauterb. & K. Schum. Folium | + | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| Rauvolfia sumatrana Jack Folium | + | − | + | − | + | + | − |

| Strophanthus caudatus (Blume.f.) Kurz Folium | − | − | + | − | + | + | + |

| Strophanthus caudatus (Blume.f.) Kurz Cortex | + | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| Strophanthus gratus Baill. Folium | − | − | + | − | − | + | − |

| Strophanthus gratus Baill. Cortex | + | − | + | − | + | + | − |

| Tabernaemontana sphaerocarpa Blume Folium | + | − | + | − | + | + | − |

| Willughbeia tenuiflora Dyer ex Hook.f Folium | − | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| Willughbeia tenuiflora Dyer ex Hook.f Cortex | + | − | + | + | + | + | − |

|

| |||||||

| Clusiaceae | |||||||

| Calophyllum tomentosum Wight. Folium | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Garcinia bancana Miq. Folium | + | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| Garcinia daedalanthera Pierre. Folium | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Garcinia daedalanthera Pierre. Cortex | − | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| Garcinia hombroniana Pierre. Folium | + | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| Garcinia kydia Roxb. Folium | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Garcinia rigida Miq. Folium | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

|

| |||||||

| Euphorbiaceae | |||||||

| Antidesma bunius (L.) Spreng Folium | − | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| Antidesma bunius (L.) Spreng Cortex | + | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| Antidesma celebicum Cortex | − | − | − | + | + | + | − |

| Antidesma celebicum Folium | − | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Antidesma montanum (Blume) Folium | + | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| Antidesma neurocarpum Miq. Folium | + | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Blumeodendron toksbrai (Blume.) Kurz. Cortex | + | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| Blumeodendron toksbrai (Blume.) Kurz. Folium | + | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| Croton argyratus Blume. Folium | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| Cephalomappa malloticarpa J.J.Sm. Cortex | − | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| Cephalomappa malloticarpa J.J.Sm. Folium | − | − | + | + | + | − | + |

| Galearia filiformis Blume. Folium | + | − | + | + | + | − | + |

| Sumbaviopsis albicans (Blume) J.J.Sm. Cortex | − | − | + | − | + | + | − |

| Sumbaviopsis albicans (Blume) J.J.Sm. Folium | − | − | + | − | + | + | − |

| Suregada glomerulata (Blume) Baill. Folium | + | − | + | − | + | − | − |

|

| |||||||

| Rubiaceae | |||||||

| Adina trichotoma Zoll. & Moritzi. Folium | + | − | + | − | + | − | + |

| Amaracarpus pubescens Blume. Folium | + | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| Canthium glabrum Blume. Folium | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Chiococca javanica Blume. Folium | + | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| Hydnophytum formicarum Folium | + | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| Hydnophytum formicarum Cortex | + | + | + | − | + | − | − |

| Nauclea calycina (Batrl.ex DC.) Merr. Folium | + | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| Nauclea calycina (Batrl.ex DC.) Merr. Cortex | − | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Posoqueria latifolia (Lam.) Roem. & Schult. Folium | − | − | + | + | + | − | − |

Key: +: present; −: absent.

3.2. Assay for α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity

The α-glucosidase of S. cerevisiae is used to investigate the inhibitory activity of the rude extracts. α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of rude extracts compounds against α-glucosidases were determined using p-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (p-NPG) as a substrate and these were compared with acarbose (Table 2). The IC50 values of compounds range from 2.33 μg/mL to 706.81 μg/mL. There are thirty-seven of samples which have IC50 lower than acarbose. Extracts derived from leaves of Garcinia daedalanthera showed inhibitory activity against α-glucosidase enzyme significantly, with IC50 value of 2.33 μg/mL. Inhibitory activity of the enzyme α-glucosidase at forty-five extracts may be due to the glycoside content in each extract. Glycosides consist of sugars that may be structurally similar to carbohydrate which is a substrate of the enzyme α-glucosidase [10]. IC50 value of samples of plant extracts are lower than acarbose because their active chemical compounds have no further fractionation and may have a synergistic effect in inhibiting α-glucosidase [11].

Table 2.

IC50 values of rude extracts against α-glucosidase.

| Number | Sample | IC50 (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | Acarbose | 117.20 |

|

| ||

| Apocynaceae | ||

| (2) | Beaumontia multiflora Teijsm. & Binn. Folium | 79.80 |

| (3) | Beaumontia multiflora Teijsm. & Binn. Cortex | 130.20 |

| (4) | Carissa carandas L.Folium | 21.14 |

| (5) | Carissa carandas L.Cortex | 20.44 |

| (6) | Ochrosia citrodora Lauterb. & K. Schum. Folium | 112.02 |

| (7) | Rauvolfia sumatrana Jack Folium | 174.27 |

| (8) | Strophanthus caudatus (Blume.f.) Kurz Folium | 706.81 |

| (9) | Strophanthus caudatus (Blume.f.) Kurz Cortex | 13.93 |

| (10) | Strophanthus gratus Baill.Folium | 50.61 |

| (11) | Strophanthus gratus Baill. Cortex | 202.17 |

| (12) | Tabernaemontana sphaerocarpa Blume Folium | 554.32 |

| (13) | Willughbeia tenuiflora Dyer ex Hook.f Folium | 8.16 |

| (14) | Willughbeia tenuiflora Dyer ex Hook.f Cortex | 42.11 |

|

| ||

| Clusiaceae | ||

| (15) | Calophyllum tomentosum Wight. Folium | 15.83 |

| (16) | Garcinia bancana Miq. Folium | 22.41 |

| (17) | Garcinia daedalanthera Pierre. Folium | 2.33 |

| (18) | Garcinia daedalanthera Pierre. Cortex | 3.71 |

| (19) | Garcinia hombroniana Pierre. Folium | 11.30 |

| (20) | Garcinia kydia Roxb. Folium | 3.88 |

| (21) | Garcinia rigida Miq. Folium | 24.48 |

|

| ||

| Euphorbiaceae | ||

| (22) | Antidesma bunius (L.) Spreng Folium | 7.94 |

| (23) | Antidesma bunius (L.) Spreng Cortex | 3.90 |

| (24) | Antidesma celebicum Cortex | 3.93 |

| (25) | Antidesma celebicum Folium | 2.34 |

| (26) | Antidesma montanum (Blume) Folium | 2.83 |

| (27) | Antidesma neurocarpum Miq. Folium | 4.22 |

| (28) | Blumeodendron toksbrai (Blume.) Kurz. Cortex | 22.82 |

| (29) | Blumeodendron toksbrai (Blume.) Kurz. Folium | 64.78 |

| (30) | Croton argyratus Blume. Folium | 366.07 |

| (31) | Cephalomappa malloticarpa J.J.Sm. Cortex | 12.22 |

| (32) | Cephalomappa malloticarpa J.J.Sm. Folium | 2.66 |

| (33) | Galearia filiformis Blume. Folium | 21.54 |

| (34) | Sumbaviopsis albicans (Blume) J.J.Sm. Cortex | 42.66 |

| (35) | Sumbaviopsis albicans (Blume) J.J.Sm. Folium | 43.40 |

| (36) | Suregada glomerulata (Blume) Baill. Folium | 57.46 |

|

| ||

| Rubiaceae | ||

| (37) | Adina trichotoma Zoll. & Moritzi. Folium | 28.22 |

| (38) | Amaracarpus pubescens Blume. Folium | 3.64 |

| (39) | Canthium glabrum Blume. Folium | 117.85 |

| (40) | Chiococca javanica Blume. Folium | 23.86 |

| (41) | Hydnophytum formicarum Folium | 181.90 |

| (42) | Hydnophytum formicarum Cortex | 11.04 |

| (43) | Nauclea calycina (Batrl.ex DC.) Merr. Folium | 18.81 |

| (44) | Nauclea calycina (Batrl.ex DC.) Merr. Cortex | 25.99 |

| (45) | Posoqueria latifolia (Lam.) Roem. & Schult. Folium | 80.27 |

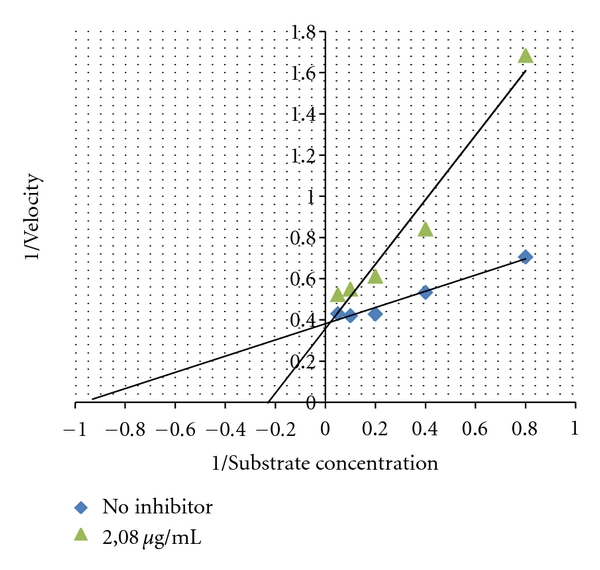

Inhibition mode of leaves extract of Antidesma celebicum from Euphorbiaceae was investigated. Inhibition mode of 80% ethanol extract showed competitive inhibitory mode. This mode may have been due because the structure is similar with glucose. This result is similar with inhibition mode of Nojirimycin which has a competitive inhibition against α-glucosidase [9] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Lineweaver-Burk plot of 80% ethanol extract of leaves of Antidesma celebicum with concentration of 2.08 μg/mL with pNPG substrate concentration of 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 mM.

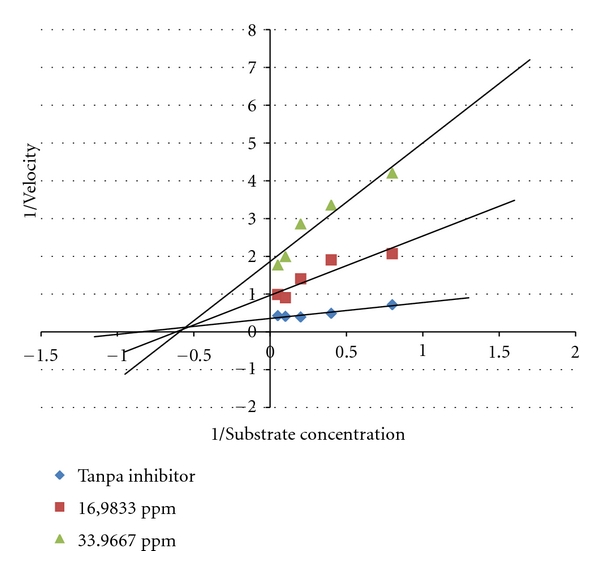

Inhibition mode of leaves extract of Garcinia kydia from Clusiaceae was investigated. Inhibition mode of 80% ethanol extract showed noncompetitive inhibitory mode [12] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Lineweaver-Burke plot of the reaction α-glucosidase in the presence of 80% ethanol extract from Garcinia kydia Roxb. Leaves.

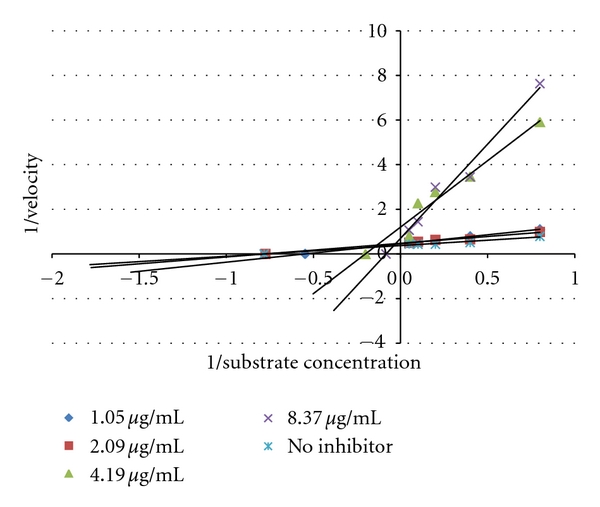

Inhibition mode of 80% ethanol extract from Amaracarpus pubescens Blume. leaves had a combination of competitive and uncompetitive inhibition. Combination of competitive and noncompetitive may have been due to the extract having more than one compound that has α-glucosidase inhibitory activity [13] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Lineweaver-Burke plot of the reaction α-glucosidase in the presence of 80% ethanol extract from Amaracarpus pubescens Blume.

4. Conclusion

In vitro assays of α-glucosidase activity showed thirty-seven of forty-five samples had IC50 values of between 2.33 μg/mL and 112.02 μg/mL, which were lower than that of acarbose (117.20 μg/mL). Based on family, 80% ethanol extract from Garcinia daedalanthera Pierre. leaves (Clusiaceae), Antidesma celebicum leaves (Euphorbiaceae), Amaracarpus pubescens Blume. leaves (Rubiaceae), and Willughbeia tenuiflora Dyer ex Hook.f leaves (Apocynaceae) had the highest α-glucosidase inhibiting activity with IC50 of 2.33 μg/mL, 2.34 μg/mL, 3.64 μg/mL, and 8,16 μg/mL. Meanwhile, types of enzyme inhibition mechanism from Garcinia kydia Roxb. leaves (Clusiaceae), Antidesma celebicum leaves (Euphorbiaceae), and Amaracarpus pubescens Blume. leaves (Rubiaceae) were noncompetitive inhibitor, competitive inhibitor, and mixed inhibitor. Currently attempts to purify the active compound from leaves extract of Garcinia kydia Roxb. (Clusiaceae), Antidesma celebicum (Euphorbiaceae), and Amaracarpus pubescens Blume. (Rubiaceae) are conducted to understand the inhibitory mechanisms more clearly. Moreover, further in vivo study is also required.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like thank to Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, University of Indonesia for supporting this project.

References

- 1.Funke I, Melzig MF. Traditionally used plants in diabetes therapy—phytotherapeutics as inhibitors of α-amylase activity. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia Brazilian Journal of Pharmacognosy. 2006;16(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(5):1047–1053. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health Republic of Indonesia. Pharmaceutical Care for Diabetes Mellitus. Kurihara, Indonesia: Department of Health Republic of Indonesia; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim KY, Nam KA, Kurihara H, Kim SM. Potent α-glucosidase inhibitors purified from the red alga Grateloupia elliptica. Phytochemistry. 2008;69(16):2820–2825. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bösenberg LH, Van Zyl DG. The mechanism of action of oral antidiabetic drugs: a review of recent literature. Journal of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes of South Africa. 2008;13(3):80–88. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lam SH, Chen JM, Kang CJ, Chen CH, Lee SS. α-Glucosidase inhibitors from the seeds of Syagrus romanzoffiana. Phytochemistry. 2008;69(5):1173–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wahyuningsih MSH, Wahyuono S, Santosa D, et al. Plants exploration from central kalimantan forest as a source of bioactive compounds. Biodiversitas. 2008;9:169–172. [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Padua LS, Bunyapiaphatsara N, Lemmens RHMJ. Plant Resources of South-East Asia: Medicinal and Poisonous Plants 1. Bogor, Indonesia: Prosea Foundation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dewi RT, Iskandar YM, Hanafi M, et al. Inhibitory effect of Koji Aspergillus terreus on α-glucosidase activity and postprandial hyperglycemia. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences. 2007;10(18):3131–3135. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2007.3131.3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugiwati S, Setiasi S, Afifah E. Antihyperglycemic activity of the mahkota dewa [Phaleria macrocarpa (scheff.) boerl.] leaf extracts as an alpha-glucosidase inhibitor. Makara Kesehatan. 2009;13(2):74–78. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrade-Cetto A, Becerra-Jiménez J, Cárdenas-Vázquez R. Alfa-glucosidase-inhibiting activity of some Mexican plants used in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;116(1):27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee DS, Lee SH. Genistein, a soy isoflavone, is a potent α-glucosidase inhibitor. FEBS Letters. 2001;501(1–3):84–86. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02631-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Storey KB. Functional Metabolism: Regulation and Adaptation. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley-Interscience; 2004. [Google Scholar]