Administration of apple polyphenols protects against experimental colitis by diminishing proinflammatory cytokine expression and TCRαβ cell activation in the colon.

Keywords: colon, inflammation, CXCR3, chemokine

Abstract

Human IBD, including UC and Crohn's disease, is characterized by a chronic, relapsing, and remitting condition that exhibits various features of immunological inflammation and affects at least one/1000 people in Western countries. Polyphenol extracts from a variety of plants have been shown to have immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects. In this study, treatment with APP was investigated to ameliorate chemically induced colitis. Oral but not peritoneal administration of APP during colitis induction significantly protected C57BL/6 mice against disease, as evidenced by the lack of weight loss, colonic inflammation, and shortening of the colon. APP administration dampened the mRNA expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-17, IL-22, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11, and IFN-γ in the colons of mice with colitis. APP-mediated protection requires T cells, as protection was abated in Rag-1−/− or TCRα−/− mice but not in IL-10−/−, IRF-1−/−, μMT, or TCRδ−/− mice. Administration of APP during colitis to TCRα−/− mice actually enhanced proinflammatory cytokine expression, further demonstrating a requirement for TCRαβ cells in APP-mediated protection. APP treatment also inhibited CXCR3 expression by TCRαβ cells, but not B or NK cells, in the colons of mice with colitis; however, depletion of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells alone did not abolish APP-mediated protection. Collectively, these results show that oral administration of APP protects against experimental colitis and diminishes proinflammatory cytokine expression via T cells.

Introduction

Crohn's disease and UC are the most prominent forms of IBDs, conditions afflicting millions of individuals [1]. In addition, persistent cases of UC can increase the risk of colorectal cancer development, whereas anti-inflammatory agents, which limit colonic inflammation, appear to reduce the risk of UC-associated cancer development [2]. The etiology and pathogenesis of IBD are poorly understood, but immune dysregulation, barrier dysfunction, and a loss of immune tolerance toward enteric flora [3, 4] are thought to result in an exacerbated immune response with an imbalance of proinflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules, and reactive oxygen metabolites, which leads to tissue injury [3, 5]. In an attempt to recapitulate aspects of human disease, a commonly used animal model for colitis is induced by administering DSS, and DSS-induced colitis exhibits several morphological and pathophysiological features resembling human UC, including superficial ulceration, mucosal damage, production of inflammatory mediators, and leukocyte infiltration [6]. Colitis in mice is thought to be attributed to autoimmune dysregulation or an imbalance of T cells [7, 8]. Several cell types and/or cytokines have been implicated in the induction of and protection from IBD. γδ T cells have been shown to protect against colon injury in chemically induced colitis models [9–11], whereas IL-17A-producing CD4+ T cells have been implicated in interacting with colonic subepithelial myofibroblasts, modifying their cytokine profile and leading to an increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines (such as IL-6) and enhanced tissue damage [12]. Serum and mucosal levels of IL-17A appear to correlate with disease activity in humans [13]. In addition, IFN-γ, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-17A, and IL-6 are required for the full manifestation of colitis in mice [14–18], and the most successful treatments for IBD in humans are therapeutics that target TNF-α [19].

Polyphenols are secondary plant metabolites, ubiquitously present in fruits and vegetables [1]. In vitro, APP stimulates NK cells and γδ T cells in vitro, as measured by up-regulation of CD69, CD11b, and IL-2Rα proliferation and the induction of proinflammatory mRNA transcripts [20–22]. APP also has immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects upon intestinal cells when given orally [23]. Recently, numerous reports have been made of polyphenols conferring protection against murine models of autoimmune disease [1, 23–28]; however, the cell types involved in polyphenol-mediated protection have yet to be thoroughly investigated. Previously, the anti-inflammatory effects of APP were suggested to be related to the expansion of γδ T cells in the murine colon [23] or a result of antioxidant activity [29]. Yet, no studies have directly investigated the mechanism of in vivo action of APP, particularly the immune cell subsets required for protection. Here, we demonstrate that APP administration confers protection against DSS colitis and diminishes proinflammatory cytokine expression. The importance of TCRαβ cells for APP-mediated protection against DSS colitis is also demonstrated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental colitis studies

Female C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD, USA). Breeding pairs of TCRδ−/−, μMT, TCRα−/−, Rag-1−/−, IL-10−/−, and IRF-1−/− mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA), and breeding colonies were maintained at the Montana State University Animal Resource Center (Bozeman, MT, USA; Table 1). All animals were maintained in individually ventilated cages under High-Efficiency Particulate Air-filtered barrier conditions of 12-h light/12-h darkness and were provided with food and water ad libitum. Experiments were conducted with 7- to 10-week-old age-matched mice. To induce colitis, mice received 2.5% DSS (∼40,000 MW, ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, OH, USA) in their drinking water for 8 days. Water intake was monitored, and mice in all groups consumed enough DSS to reach the critical load (30 mg/g body weight [6]) required to induce severe colitis. Some mice also received 1% APP (Apple Poly, Littleton, CO, USA) in their drinking water or received daily treatments of APP via i.p. injection or oral gavage. APP (∼95% polyphenols by weight) is derived from the skin of Malus pumila Mill, also known as the paradise apple. APP is a mixture of monomeric and oligomeric polyphenols with >90% of the polyphenols as tannins [22]. APP was suspended in room temperature H2O, 0.45 μm-filtered, and used within 1 week of suspension. For in vivo T cell depletion studies, mice were treated i.p. on Days –2 and 4 with 0.5 mg GK1.5 (anti-CD4), 2.43 (anti-CD8), or H7-597 (anti-TCRβ) mAb or normal rat or hamster IgG as control. All mAb were obtained from BioXCell (West Lebanon, NH, USA), and neutralization was confirmed via flow cytometry. All animal care and procedures were in accordance with institutional policies for animal health and well-being.

Table 1. Mouse Strains Used in This Study.

| Mouse straina | Immunodeficiency |

|---|---|

| C57BL/6 | WT |

| TCRδ–/– | Lack γδ T cells |

| μMT | Lack B cells |

| TCRα–/– | Lack αβ T cells |

| Rag-1–/– | Lack B and T cells |

| IL-10–/– | Do not produce IL-10 |

| IRF-1–/– | Defects in CD8+, NK, and γδ T cell development, Th1 cell response |

All mouse strains are on a C57BL/6 genetic background.

Histology

Upon termination of experiments, colons from individual mice were removed, washed with PBS following removal of fecal material, and fixed in 10% formaldehyde. Longitudinal sections were then stained with H&E. The entire colon (from anus to cecum) was then examined by a blind pathologist, and areas of inflammation or mucosal ulceration were scored. For inflammation, scores were graded by extent (focal, multifocal, or extensive) and depth/penetration of inflammation (lamina propria, into submucosa, into muscularis propria). The degree of inflammation was then given a numerical value where 0 is none observed, and 3 is severe inflammation. Mucosal ulceration scores were based on size and extent of ulceration where 0 is normal, and 3 is complete ulceration. The total inflammation or mucosal ulceration histologic score from each mouse was the sum score of all of the areas of pathology in an individual colon.

Colon RNA extraction and RT-PCR analysis

The terminal cm of colon was washed with PBS, blotted dry, and stored in RNAlater reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) until RNA extraction. Tissue was then transferred to Qiagen RLT buffer and homogenized prior to lysis on a Qiashredder column (Qiagen) and RNA extraction with an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). cDNA was generated using the Superscript III First Strand synthesis system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Primers for immune-related genes, along with β-actin (endogenous control), were designed using the PrimerQuest application from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA; IDTDNA.com). Amplicons were visualized under UV illumination on a 2% agarose gel containing GelRed (Biotium, Hayward, CA, USA). Amplicon luminosity was determined via densitometry and normalized to β-actin to ascertain relative gene expression. For qRT-PCR, RNA was extracted, and cDNA was synthesized, as described above. Primers were designed with Primer Express, primer design software from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA). Relative-specific mRNA was quantified by measuring SYBR Green incorporation during real-time qRT-PCR using the comparative threshold method [30]. Primers specific for β-actin were used as the endogenous control. The PCR was set up in triplicate and cycled, and data were collected on an Applied Biosystems GeneAmp 5700 sequence detection system.

MPO assay

After the terminal cm of colon was removed for mRNA analysis, the proximal cm of colon was removed, washed with PBS, and blotted dry prior to freezing at –80°C. MPO levels were measured using a modification of previous protocols [6]. Briefly, samples were thawed and suspended (10%, w/v) in MPO buffer [50 mM KPi buffer, pH 6.0, containing 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (0.1 g/20 ml Kpi)] prior to sonication. Sonicates were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4°C, and supernatants were harvested. Supernatants (5 μl) were mixed with a solution of 140 μl MPO buffer + 15 μl 20 mg/ml O-dianisidine dihydrochloride + 15 μl 20 mM hydrogen peroxide. After 10 min, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 3 μl 2% sodium azide, and absorbances were read at 450 nm.

Cell culture and cytokine analysis

Mononuclear cells from spleens and MLNs from mice were isolated as described [31–33] and cultured (5×106 cells/ml) for 5 days at 37°C/5% CO2 in CM and RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1 mM nonessential amino acids, penicillin/streptomycin (10 U/ml), and 10% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta, GA, USA). Supernatants were harvested and stored at –20°C until evaluated by cytokine-specific capture ELISAs, as described [31, 32, 34]. Supernatants were also measured for the accumulation of nitrite, the oxidized product of NO, as described previously [35]. All detection chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Aliquots of 50 μl cell-culture supernatant were reacted with equal volumes of Griess reagent (1% sulfanilamide, 0.1% naphthylenediamine dihydrochloride, 2.5% H3PO4) at room temperature for 10 min. Sodium nitrite was used to generate a standard curve for NO2– production, and peak absorbance was measured at 550 nm with a ThermoMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Cell-free medium contained <1.5 μM NO2–.

FACS analysis

Colonic LP leukocytes were isolated from mice with colitis, as described previously [36]. Subsequent isolation of colons, fecal material, and mucus was flushed using RPMI-1640 medium, flayed open, minced into ∼1-mm pieces, and shaken vigorously in CM to remove remaining mucus and fecal material, and the waste was filtered through a mesh screen. Colonic tissues were then placed in RPMI-1640 medium containing 5% FBS (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) and 2 mM DTT (Sigma-Aldrich) in a 50-ml Teflon flask, gently agitated on a stir plate at room temperature for 5–10 min. This process resulted in the removal of the intestinal epithelial cell fraction. Supernatant was discarded, and DTT was rinsed from the intestinal pieces with RPMI-1640 medium. Intestinal tissues were returned to the Teflon flasks containing 50 U/ml collagenase type IV plus 0.08 U/ml DNase in CM, and the cell suspension was agitated at 37°C. After 2 h, the supernatant containing LP cells was washed in CM, resuspended in 40% Percoll (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden), then layered over 60% Percoll solution, and subjected to a gradient centrifugation. Lymphocytes were removed from the interface, washed, and resuspended in CM. LP cells were then analyzed by FACS analysis using conventional methods [34, 37]. LP cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated or biotinylated mAb (Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA, USA; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA): anti-CD4 (clone L34T4), anti-CD8 (clone 853-6.7), anti-TCRβ chain (clone H57-597), anti-B220 (clone RA3-6B2), anti-MHCII (clone AF6-120.1), anti-CD11b (clone M1/70), anti-CD11c (clone N418), anti-Gr-1 (clone RB6-8C5), anti-CXCR3 (clone CXCR3-173), anti-NK1.1 (clone PK136), or anti-TCRδ chain (clone GL3); cells were then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde. Stained leukocytes were analyzed using an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA).

Statistical analysis

The Student′s t test was used to evaluate the differences in colon length, body weight, MPO levels, cytokine production, histology score, and leukocyte populations when two groups were compared. When more than two groups were compared, an ANOVA, followed by Tukey's test, was used. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Oral APPs protect against DSS-induced colitis

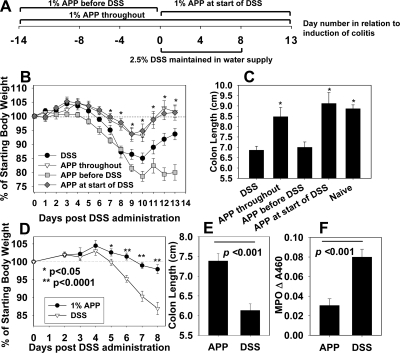

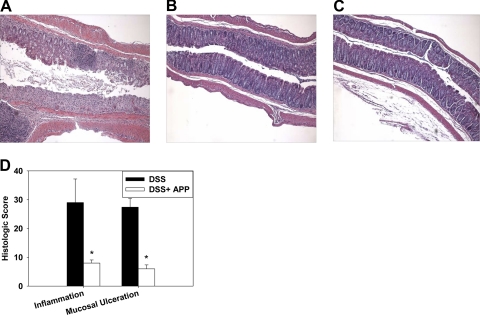

Recent work by others [24, 26] has shown that plant polyphenols can protect against experimental colitis. Prior to inducing colitis, the impact of APP on naïve mice was evaluated, and no differences in weights were observed when compared with water-treated mice (data not shown). To determine if oral treatment with 1% APP given via the drinking water can ameliorate experimental DSS colitis, the efficacy of three different APP treatment regimens was tested: mice received no agonist, 1% APP for 2 weeks prior to colitis induction only (Days –14 to 0), 1% APP starting at the time of colitis induction (Days 0–13), or 1% APP for 2 weeks prior to DSS treatment and throughout the experiment (Days –14 to 13). All groups were given 2.5% DSS in their drinking water for 8 days after which fresh water, or 1% APP without DSS was provided to the mice for 5 days (Fig. 1A). Body weights were monitored daily, and on Day 13, individual colon length was recorded. The results showed that treatment with 1% APP at the time of induction or throughout the experiment significantly increased the resistance of C57BL/6 mice to disease, as evidenced by minimal weight loss (Fig. 1B) and minimal to no shortening of the colon length (Fig. 1C). These findings were confirmed in subsequent experiments, in which mice were treated with 1% APP at the start of colitis induction and evaluated on Day 8 after DSS treatment when colon length was recorded, and MPO activity was measured as a correlate of neutrophil inflammation [6]. Again, APP treatment conferred protection against DSS-induced weight loss (Fig. 1D), colon shortening was induced (Fig. 1E), and MPO activity was reduced significantly in treated mice (Fig. 1F). It was observed that mice given APP were also still able to form fecal pellets, whereas diseased animals had severe bloody diarrhea. H&E staining was performed on formalin-fixed longitudinal sections from mice that received DSS, with or without 1% APP in their drinking water for 8 days. DSS administration results in inflammation of the colon characterized by leukocyte infiltration, crypt destruction, and mucosal ulceration and erosion [29]. As shown, mice treated with DSS displayed massive leukocyte infiltration and mucosal ulceration (Fig. 2A and D), whereas APP ameliorated pathology (Fig. 2B and D).

Figure 1. Oral administration of APP ameliorates DSS-induced colitis.

(A) Experimental design. (B and C) C57BL/6 mice (five/group) were fed 2.5% DSS in their drinking water for 8 days, after which, mice were fed regular water for 5 days. Some mice also received 1% APP in their water source for 14 days prior to colitis induction, at the start of colitis induction, or for 14 days prior to and also during colitis induction. APP (1%) in the water source during colitis induction or throughout the experiment protected mice against colitis, as evidenced by changes in (B) body weights and (C) shortening of the colon. Error bars represent sem. *P < 0.05 as compared with mice receiving DSS only. (D–F) DSS (2.5%) was fed to C57BL/6 mice in their drinking water for 8 days. APP-treated mice received 1% APP in their drinking water starting on Day 0. (D) Body weights were measured, and on Day 8, mice were killed. (E) Colons lengths were measured, and (F) colonic MPO activity was assayed as a measure of neutrophil inflammation according to standard protocols. APP-treated mice were also able to form fecal pellets, whereas control mice had severe bloody diarrhea (data not shown). Data in D–F are pooled from two to four independent experiments with a total of 10–20 mice/group; error bars represent sem. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.0001 as compared with mice receiving DSS only.

Figure 2. APP reduces colonic tissue damage during DSS-induced colitis.

DSS (2.5%) was fed to C57BL/6 mice in their drinking water for 8 days. APP-treated mice also received 1% APP in their drinking water starting on Day 0. On Day 8, longitudinal colon H&E sections were prepared from animals treated with (A) DSS or (B) DSS + APP or (C) from naive mice. Representative sections are shown. (D) Histologic scores were generated as described in Materials and Methods. Data shown are from five mice/group. Error bars represent sem. *P < 0.05 as compared with mice receiving DSS only.

APP dampens colonic expression of proinflammatory mRNAs during DSS-induced colitis

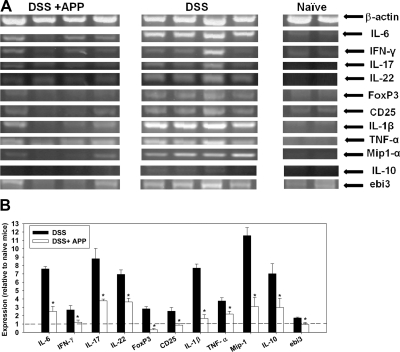

To determine the impact of APP on colonic cytokine expression, total RNA was isolated from the colons of mice (untreated or treated with 1% APP) following 8 days of DSS exposure. RNA was also isolated from the colons of naïve mice as a control. RT-PCR for several cytokine/chemokine and regulatory genes, with β-actin as an endogenous control, was performed. Administration of APP dampened the expression of proinflammatory genes, including IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17, IL-22, and MIP-1α, as well as CD25, in the colons of mice treated with DSS (Fig. 3A and B). mRNA expression of regulatory transcripts, such as IL-35ebi3, IL-10, and FoxP3, was also lower in APP-treated colitis mice, whose colonic cytokine profile more resembled that of naïve mice, rather than mice treated with DSS alone (Fig. 3A and B). No overt transcriptional changes were observed in mRNA expression of IL-15, IL-18, TGF-β, IFN-β, iNOS, p53, myc, bcl2, growth arrest and DNA damage-induced gene-153, IL-4, IL-13, Fas, Fas ligand, GM-CSF, keratinocyte growth factor, CD73, IL-25, IFN-λ, IFN-α, IL-12p35, Stat1, Stat2, Stat3, Stat6, MyD88, retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor γT, or IL-12p40 between DSS- and DSS/APP-treated groups via semi-qRT-PCR.

Figure 3. APP treatment diminishes colonic expression of proinflammatory mRNAs.

(A) DSS (2.5%) was fed to C57BL/6 mice in their drinking water for 8 days. APP-treated mice also received 1% APP in their drinking water starting on Day 0. On Day 8, mice were killed, and the terminal centimeter of the colon was removed and homogenized prior to RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis. Semi-qRT-PCR, for several immune-related genes, along with β-actin as a control, was then performed according to conventional protocols, and amplicons were visualized on a 2% agarose gel. Each lane represents the results from an individual mouse. (B) Amplicon luminosity was determined by densitometry to estimate expression levels and normalized to β-actin. The mean expression level of each gene in relation to the expression level of same gene in naïve mice (indicated by a dashed line) is shown. Error bars represent sem. *P < 0.05 as compared with mice receiving DSS only. Results are representative of two independent experiments.

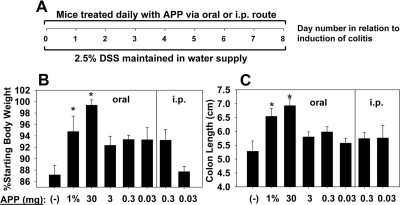

APP protection against DSS colitis is dose- and route-dependent

To determine how the impact of route and dose of APP influences its protective efficacy, mice were orally gavaged daily or i.p.-dosed with 30, 3, 0.3, or 0.03 mg APP, starting at the beginning of DSS administration (Day 0), and results were compared with control mice or mice given 1% APP in their drinking water (Fig. 4A). Mice receiving 1% APP in their water source or 30 mg APP daily via oral gavage were protected against colitis, as measured with minimal to no change in body weights or shortening of colon lengths (Fig. 4B and C). Mice receiving as little as 5 mg APP daily were protected from colitis in some experiments; however, this effect was inconsistent. i.p. administration of APP failed to protect against colitis (Fig. 4), and in fact, i.p. doses of APP ≥ 3 mg APP were found to be toxic, as mice exhibited rapid weight loss and drop in body temperature. For all subsequent experiments, mice were treated with H2O or 30 mg APP daily via oral gavage, as some strains of immunodeficient mice were found to be averse to drinking APP in their water source.

Figure 4. Oral but not peritoneal administration of APP confers protection against DSS-induced colitis.

C57BL/6 mice (five/group) were fed 2.5% DSS in their drinking water for 8 days. One group also received 1% APP in their water source, and the remaining experimental groups received various daily doses of APP given i.p. or via oral gavage. Control mice received a daily oral gavage of sterile water. (A) Experimental design. (B) Body weights were recorded on Day 8, and (C) colon lengths were measured on Day 8. Doses of ≥3 mg APP were found to be toxic when given i.p. Error bars represent sem. *P < 0.05 as compared with mice receiving DSS only.

APP-mediated protection against colitis is lymphocyte-dependent

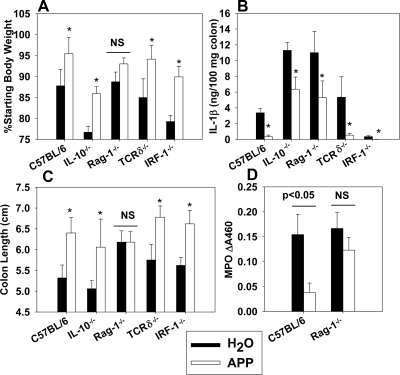

To investigate the mechanism of APP-mediated protection against colitis, WT, IL-10−/−, Rag-1−/− (lacks B and T cells), TCRδ−/−, and IRF-1−/− mice (defects in CD8+, NK, and γδ T cell development and development of a Th1 cell response [38]), all on a B6 background, were orally gavaged daily with H2O or 30 mg APP, beginning on the first day of DSS challenge. Body weights were monitored, and on Day 8, colon lengths were measured, as well as colonic IL-1β and MPO levels. APP administration protected C57BL/6, IL-10−/−, TCRγδ−/−, and IRF-1−/− mice against DSS-induced colitis, as evidenced by changes in body weights or shortening of the colons (Fig. 5A and C). Colonic IL-1β levels were also reduced significantly (Fig. 5B). However, APP treatment of Rag-1−/− mice did not result in significant changes in body weights, colon shortening, or colonic MPO activity (Fig. 5A, C, and D), indicating a role for TCRαβ cells and/or B cells in APP-mediated protection against colitis. IL-1β levels were still diminished in Rag-1−/− mice, suggesting that APP may also be impacting a nonlymphoid cell subset (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. APP requires lymphocytes to confer protection against DSS-induced colitis.

The protective abilities of APP were assayed against colitis in WT C57BL/6 mice, IL-10−/−, Rag-1−/− (lack B and T cells), TCRδ−/−, and IRF-1−/− mice on a B6 background. Four to six mice were used per experimental group. Colitis was induced by the addition of 2.5% DSS to the murine water source for 8 days. Control mice received a daily gavage of sterile water, whereas APP-treated mice received 30 mg daily via oral gavage. (A) Body weights were monitored, and on Day 8, (B) colonic IL-1β levels were measured, (C) colon lengths measured, and (D) colonic MPO levels were determined. Data shown for C57BL/6 and Rag-1−/− mice represent one of two independent experiments with similar results. Error bars represent sem. *P < 0.05 as compared with mice of the same genotype receiving sterile water.

TCRαβ cells are required for APP-mediated protection against colitis and for dampening of proinflammatory cytokine expression

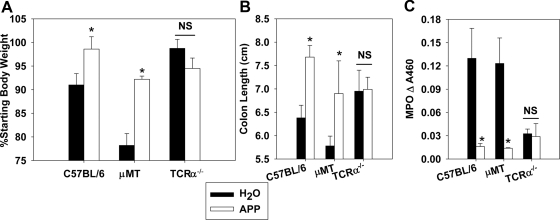

As lymphocytes are required for APP-mediated protection against colitis, subsequent studies tested whether this protection was B or T cell-dependent. C57BL/6, μMT, and TCRα−/− mice were orally gavaged daily with H2O or 30 mg APP, beginning at DSS colitis challenge. APP protected μMT mice against weight loss, shortening of colon length, and colonic neutrophil infiltration, but this protection was abated in TCRα−/− mice (Fig. 6A–C). Interestingly, vehicle-treated μMT mice lost significantly more body weight than vehicle-treated C57BL/6 mice. Cytokine production by cells isolated from the spleens and MLNs from these mice was assessed. Although APP dampened the production of NO, IFN-γ, and IL-6 by WT mice with colitis, administration of APP to TCRα−/− mice with colitis actually enhanced the production of NO, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-17, and IL-22 (Table 2). In addition, although APP diminished proinflammatory mRNA expression in colons of WT mice, no effect of APP was observed in TCRα−/− mice (data not shown). No marked differences were observed in TGF-β, IL-10, or TNF-α production in the spleens or MLNs of mice (Table 2).

Figure 6. APP requires T cells to confer protection against DSS-induced colitis.

The protective effects of APP against colitis were assayed in WT C57BL/6, μMT, and TCRα−/− mice. Colitis was induced by the addition of 2.5% DSS to the murine water source for 8 days. Control mice received a daily gavage of sterile water, whereas APP-treated mice received 30 mg daily via oral gavage. (A) Body weights were recorded, and on Day 8, (B) colon lengths measured, and (C) colonic MPO levels were determined. Data are pooled from two independent experiments with eight to 10 mice/group. *P < 0.05 as compared with mice of the same genotype treated with sterile water.

Table 2. APP Dampens Proinflammatory Cytokine Expression in WT Mice but Exacerbates Proinflammatory Cytokine Expression in TCRα–/– Mice.

| Nitrite | IFN-γ | TNF-α | IL-6 | IL-17 | IL-22 | TGF-β | IL-10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6 H2O/MLN | 14.9 (0.4) | 10.0 (1.5) | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.59 (0.15) | 0.22 (0.18) | 9.8 (1.7) | 0 | 0.12 (0.01) |

| C57BL/6 APP/MLN | 10.7 (0.1)a | 7.0 (1.1)a | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.47 (0.03) | 0.10 (0.08) | 6.7 (1.5) | 0 | 0.36 (0.11) |

| TCRα–/– H2O/MLN | 7.3 (1.2) | 1.89 (0.84) | 0 | 0.51 (0.1) | 0.37 (0.29) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.08 (0.07) | 0 |

| TCRα–/– APP/MLN | 29.4 (1.6)a | 52.9 (6.4)a | 0 | 4.83 (0.24)a | 4.0 (1.7)a | 9.3 (1.1)a | 0 | 0.34 (0.10)a |

| C57BL/6 H2O/Spleen | 12.3 (2.3) | 0 | 0.13 (0.09) | 0.83 (0.40) | 0 | 0 | 0.03 (0.03) | 0.07 (0.02) |

| C57BL/6 APP/Spleen | 4.9 (0.1)a | 0 | 0.03 (0.03) | 0a | 0 | 0 | 0.1 (0.07) | 0.01 (0.008)a |

| TCRα–/– H2O/Spleen | 30.9 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.62) | 0.06 (0.05) | 0 | 0.27 (0.14) | 0 | 0.23 (0.07) | 0.03 (0.02) |

| TCRα–/– APP/Spleen | 37.3 (0.3)a | 0.9 (.45) | 0.08 (0.07) | 2.2 (0.13)a | 0.26 (0.18) | 0 | 0.07 (0.04)a | 0.019 (0.013) |

DSS (2.5%) was fed to C57BL/6 and TCRα–/– mice in their drinking water for 8 days. Control mice received a daily gavage of sterile water, whereas APP-treated mice received 30 mg daily via oral gavage. Mice were sacrificed on Day 8, and spleens and MLNs of mice were removed and pooled from five mice/group. Whole cells (5 × 106 cells/ml) were cultured for 5 days, and cytokine levels in cell-free supernatants were determined via ELISA. Nitrite values are in μM, whereas cytokine levels are in ng/ml. se is shown in parentheses.

P < 0.05 as compared with cytokine production from mice of the same genotype treated with sterile water.

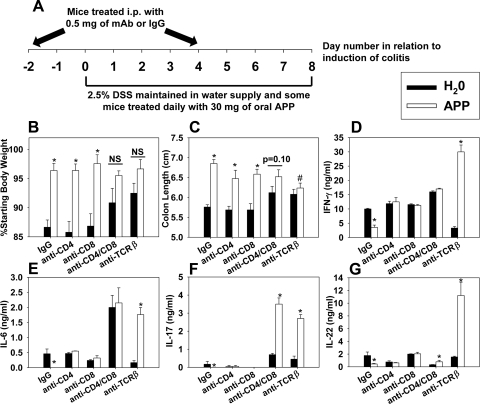

APP-mediated protection is not conferred by CD4+ or CD8+ T cells alone

To further investigate the involved T cell subsets required for APP-mediated protection, C57BL/6 mice were depleted of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells (alone or in combination), depleted of TCRβ+ cells, or treated with respective control rat or hamster IgG. Mice received H2O or 30 mg APP via daily oral gavage starting on the first day of colitis induction (Fig. 7A). Upon termination of DSS treatment on Day 8, colon lengths were recorded, and cytokine production from MLNs was determined. Depletion of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells alone did not diminish APP-mediated protection against weight loss or colonic shortening (Fig. 7B and C); however, depletion of these subsets did reduce the ability of APP to diminish proinflammatory cytokine production by MLNs (Fig. 7D–G). APP also conferred protection in mice depleted of their CD25+ cells (data not shown). Although anti-TCRβ mAb-treated mice were more resistant to DSS colitis than those treated with IgG (Fig. 7B and C), APP treatment could not rescue mice depleted of their TCRβ+ cells, evident by their significantly shorter colons than APP plus IgG-treated mice. In addition, administration of APP during colitis to mice depleted of TCRβ+ cells resulted in an increase in MLN production of IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-17, and IL-22. Double depletion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells partially reduced the protective effects of APP against colitis (Fig. 7B) and enhanced the MLN production of IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-17, and IL-22 in APP-treated mice, although not to the same extent as depletion of TCRβ+ cells (Fig. 7D–G), which may indicate a partial requirement of CD4–/CD8–/TCRβ+ cells for APP-mediated protection.

Figure 7. Depletion of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells alone does not abrogate APP-mediated protection.

Colitis was induced in C57BL/6 mice by the addition of 2.5% DSS to the murine water source for 8 days. Control mice received a daily gavage of sterile water, whereas APP-treated mice received 30 mg daily via oral gavage. On Days –2 and 4, mice received 0.5 mg IgG (n=25/group), 0.5 mg anti-TCRβ (n=20/group), 0.5 mg anti-CD4 (n=15/group), 0.5 mg anti-CD8 (n=15/group), or 0.5 mg anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 mAb (n=10/group). (A) Experimental design. Data in B and C were pooled from five independent experiments; error bars depict sem. (B) Colon lengths and (C) body weights were measured on Day 8. *P < 0.05 as compared with colon length of mice treated with the same mAb treated with sterile water; #P < 0.05 as compared with colon length of mice treated with the same mAb treated with APP. (D–G) MLNs were removed from mice on Day 8 after DSS treatment and pooled from five mice/group. Whole cells (5×106 cells/ml) were cultured for 5 days, and cytokine levels in cell-free supernatants were determined via ELISA. *P < 0.05 as compared with cytokine production from mice treated with the same mAb treated with sterile water; error bars represent sem. Data in D–G are representative of one of two independent experiments with similar results.

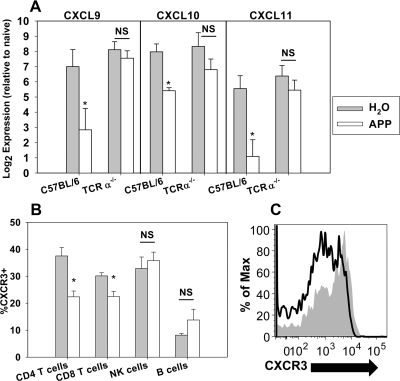

APP dampens the mRNA expression of CXCL9–11 and T cell CXCR3 expression in the colons of mice during colitis

A recent study showed that administration of apple extracts to a LPS-stimulated cell line could dampen the expression of CXCL9 and CXCL10 [39], which along with CXCL11, are all IFN-γ-induced chemokines, up-regulated in the colonic mucosa of patients with inflamed IBD [40], that attract activated Th1 cells expressing high levels of CXCR3 [41]. Others have shown that the proportion of CXCR3+ and CXCR3+CD4+ T cells in the LP is increased in patients with IBD, whereas blockade of the CXCR3 axis can mitigate colitis [41–43]. Therefore, the colonic mRNA expression of CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 was evaluated in APP- or vehicle-treated WT or TCRα−/− mice with colitis. Administration of APP decreased mRNA expression of CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 by four- to 16-fold in WT mice but not in TCRα−/− mice (Fig. 8A). To determine if dampened CXCR3 ligand mRNA expression by APP resulted in a decrease in the proportion of CXCR3+ cells, flow cytometry analysis was performed on leukocytes isolated from the colons of mice with colitis. APP treatment markedly decreased the expression of CXCR3 on CD4+ T cells (Fig. 8B and C). The proportion of CD8+ T cells expressing CXCR3 was also reduced significantly by APP; however, CXCR3 expression by NK and B cells was not affected significantly (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8. APP dampens colonic expression of CXCL9 and CXCL11 mRNAs in WT but not TCRα−/− mice and diminishes colonic T cell CXCR3 expression.

Colitis was induced by the addition of 2.5% DSS to the water source of WT C57BL/6 and TCRα−/− mice for 8 days. Control mice received a daily gavage of sterile water, whereas APP-treated mice received 30 mg daily via oral gavage. (A) On Day 8, mice were killed, and the terminal centimeter of the colon was removed and homogenized prior to RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis. qRT-PCR analysis was then performed on individual colons for CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 relative to β-actin as an endogenous control. Log2 mRNA expression was then plotted relative to expression in naïve WT mice. Data are representative of four mice/group from one of two independent experiments with similar results. Error bars represent sem. *P < 0.05 as compared with mice of the same genotype, which were treated with sterile water. (B and C) Colitis was induced in WT mice, and APP treatments were given as described above. On Day 8, LP lymphocytes were isolated from the colons of mice and analyzed via flow cytometry. CXCR3 expression was measured after gating for CD4+ T cells (CD4+/TCRβ+), CD8+ T cells (CD8+/TCRβ+), NK cells (NK1.1+), and B cells (B220+/MHCIIhi). (B) Data depicted are representative of five mice/group from one of two independent experiments with similar results. Error bars represent sem. *P < 0.05 as compared with mice that were treated with sterile water. (C) Representative histogram for CXCR3 expression on gated colonic LP CD4+ T cells from water (shaded)- and APP (open)-treated mice.

DISCUSSION

Conventional colitis therapies can reduce periods of active disease and help preserve remission; however, these treatments often bring marginal results, and the disease can become refractory [3, 7]. In addition, presently, no definitive surgical cure exists for IBD [44]. As a result of the lack of efficacious conventional treatments, up to 40% of IBD patients are estimated to use some form of megavitamin or herbal or dietary supplement to complement conventional therapies [7, 45, 46]. Plant polyphenols, such as those found in green tea and unripe apples, have been the topic of much research over the past decade [21]. Catechins and tannins, types of polyphenols, display various beneficial, biological activities. For example, unripe APP exhibit antioxidant activities, inhibition of tumor proliferation, and immunomodulatory effects [21, 23, 25, 47, 48]. Plant tannins can stimulate macrophages [21], and green tea polyphenols have been demonstrated to down-regulate CD11b on CD8+ T cells, monocytes, and granulocytes [49]. Of particular interest is the demonstration by others that various polyphenols could provide protection against rodent models of autoimmune diseases, such as IBD and multiple sclerosis [1, 24–27, 50]. In addition, others have shown that feeding APP can increase the percentage of γδ T cell amongst intraepithelial lymphocytes in the intestines of mice [23]. As γδ T cells have been demonstrated to be protective in murine models of colitis [10], we queried whether oral administration of APP could provide protection against DSS-induced colitis. We found that the feeding of 1% APP to mice during the induction of colitis, but not before colitis induction, enhanced the resistance of mice to colitis, as measured by weight loss, colonic shortening, and colonic MPO levels. Leukocyte and mucosal ulceration as a result of colitis was also ameliorated by APP.

We also assessed the effects of APP on proinflammatory cytokine mRNA expression. Administration of APP dampened the expression of proinflammatory transcripts, such as IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-17, IL-22, CD25, IL-1β, TNF-α, and MIP-1α, in the colons of mice treated with DSS. IFN-γ, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-17, and IL-6 are all required for the full manifestation of colitis in mice [14–18]; therefore, the suppression of these cytokines in the colon by APP may be partially responsible for the observed protection. Although IL-22 has been shown to be elevated in human cases of IBD and in experimental mouse models [51], the role of IL-22 in colitis is unclear, as it has been shown to induce proinflammatory cytokines but also has the ability to enhance mucous production and to dampen local intestinal inflammation [52]. A study with human IBD patients demonstrates that serum and mucosal levels of IL-17A correlate with disease activity [13], and the most successful treatments for IBD in humans are those that target the activity of TNF-α [19], indicating that the observed effects of APP in the murine colon during experimental colitis may have relevance to human disease. Although APP diminished proinflammatory Th1- and Th17-type mRNA expression in the colons of mice with colitis, APP did not up-regulate Th2-type mRNAs, and regulatory transcripts, such as IL-35ebi3, IL-10, and FoxP3, were also lower in DSS-treated mice treated with APP, which had colonic cytokine profiles more resembling those of naïve mice than mice treated with DSS alone.

In our initial studies, control mice were supplied with 2.5% DSS in their drinking water, whereas APP-treated mice were supplied with 2.5% DSS, concomitantly with 1% APP in their drinking water. To exclude the possibility that APP binds DSS and thus interferes with colitis development, an experiment was performed in which mice were instead treated daily, orally, or by i.p. administration to assess if APP could protect against colitis. Daily oral, not i.p., treatment protected mice against colitis. In fact, high i.p. doses of APP (>3 mg) were toxic, and none of the i.p. doses tested conferred protection against colitis, a finding consistent with in vitro studies showing high concentrations of APP to be toxic [22]. In contrast, high-dose oral administration of APP was well-tolerated [>100 mg daily (∼4950 mg/kg)], and daily oral administration of 30 mg APP (∼1500 mg/kg) conferred equivalent protection to 1% APP supplied in the drinking water. Based on the relative surface area of humans and mice, a 30-mg daily dose of APP for mice would equate to ∼8 g APP in humans. Protection against colitis was achieved with a 5-mg dose of APP (∼1.4 g human dose) in some experiments; however, this effect was not always reproducible, and a daily dose of 30 mg APP was used for all subsequent experiments. The DSS model used here is a very acute disease; therefore, future studies will be needed to determine if lower doses of APP can confer protection against chronic models of colitis, which may more resemble the onset of disease in humans. The reason such high doses of APP administered orally were not toxic may be because the gut appears to regulate the uptake of orally administered polyphenols, preventing toxic levels from reaching the bloodstream [22]. Others have shown plasma uptake of polyphenols in rats plateaus at 10.2 μg/ml (1000 mg/kg oral dose) and does not elevate, even when rats are supplied with 2000 mg/kg of a polyphenol preparation [53]. This suggests oral administration of polyphenols to animals may naturally prevent overdose and regulate polyphenol concentrations in the plasma at optimal concentrations [22]. Safety evaluations of polyphenols in humans are ongoing, and a recent study shows that a daily oral 4000 mg dose of polyphenols is well-tolerated for at least 1 month of therapy [54].

Recently, a separate group has demonstrated APP can protect against colitis; however, no investigation of the mechanism of protection has been undertaken [29]. To investigate how APP confers protection, colitis was induced in WT C57BL/6, IL-10−/−, Rag-1−/−, TCRδ−/−, and IRF-1−/− mice on a B6 background to assess APP-mediated protection. Although APP has been found to enhance the proportion of γδ T cells in the intestine by others [23], APP-mediated protection against colitis in our study was found to be independent of γδ T cells. Although IRF-1−/− and IL-10−/− mice are more susceptible to DSS-induced colitis [38, 55], IRF-1 signaling and IL-10 were found to be dispensable for APP-mediated protection. The finding that APP can confer protection against colitis in the absence of IL-10 is particularly intriguing, as patients with severe Crohn's disease are defective in IL-10 production [56], and IL-10 expression is impaired in the intestinal mucosa of Crohn's disease patients who failed to respond to steroid therapy [57]. Thus, APP uses an IL-10-independent pathway to provide protection against IBD, implicating APP as a potential benefit to complement therapies targeting IL-10, which can be ineffective.

Although APP conferred protection in WT, IL-10−/−, TCRδ−/−, and IRF-1−/− mice, protection was abated in Rag-1−/− mice, suggesting a role for B or TCRαβ cells. To assess the role of B cells, colitis was induced in μMT mice, and APP was still protective. Interestingly, μMT mice were found to be more susceptible to DSS colitis, as measured by weight loss and rectal bleeding, relative to WT mice, indicating a role for B cells in protection to DSS colitis, which to our knowledge, has not been reported previously. A role for B cells in protection from colitis has been proposed in a spontaneous, chronic colitis model, in which B cells are thought to protect by suppressing the effects of pathogenic T cells [58]. However, future studies will be needed to determine the protective role of B cells, as demonstrated here in an acute, DSS-induced colitis model.

To assess the role of TCRαβ cells, TCRα−/− mice on a B6 background were induced with colitis to determine whether APP is protective. Although DSS colitis was not as pronounced in TCRα−/− mice relative to WT mice, as measured by weight loss, shortening of the colon, and colonic MPO levels, the administration of APP did not provide any protection to TCRα−/− mice. Although APP diminished NO, IL-6, and IFN-γ production by MLNs from WT mice, APP had actually an opposite effect by enhancing the production of NO IL-6, IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ in TCRα−/− mice. APP is a mixture of polyphenols containing monomeric and oligomeric forms [22]; the oligomeric but not monomeric fraction of APP has been shown to have proinflammatory effects upon γδ T cells in vitro [22]. In contrast, polymeric and monomeric fractions of other polyphenols are known to mediate protection against colitis in animal models [26, 59]. The proportion of γδ T cells and NK cells amongst MLN lymphocytes in TCRαβ-deficient mice was found to be increased four- and twofold, respectively. Thus, the increased production of proinflammatory cytokines by TCRα−/− mice treated with APP possibly may be a result of the activation of innate leukocytes by oligomeric polyphenols, an affect that may normally be suppressed by the presence of regulatory T cells.

To further elucidate which TCRαβ cell subsets are required for APP-mediated protection, mice were depleted of CD4+, CD8+, TCRβ+, or CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Depletion of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells had a minimal effect on the protective efficacy of APP; however, the suppressive effect of APP upon proinflammatory expression by MLNs was diminished. Control mice depleted of TCRβ+ or CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were more resistant to colitis, which is not surprising, as CD4+ and CD8+ T cells can induce colitis in animal models [60–62]. However, the protective effect of APP was mitigated in mice depleted of TCRβ+ or CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Colitis induction and APP treatment of mice depleted of TCRβ+ cells resulted in a similar phenotype to that observed in TCRα−/− mice, indicating that the effects of APP observed in TCRα−/− mice were not a result of developmental defects. Although mice depleted of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells displayed similar susceptibility to colitis (with or without APP treatment) as mice depleted of TCRβ+ cells, the exacerbation of proinflammatory cytokine production by MLNs from mice with colitis treated with APP was more pronounced in mice depleted of TCRβ+ cells rather than CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. These results indicate that a double-negative TCRαβ cell (CD4– CD8– TCRβ+) could be partially responsible for suppressing the induction of proinflammatory cytokines by APP in the MLNs of mice with colitis. Recent evidence is emerging that double-negative TCRαβ cells can play a regulatory role and ameliorate autoimmune disease and prevent transplant rejection [63–65]; however, further studies will be needed to clarify their role in colitis.

Others have shown recently that apple extracts added to LPS-stimulated macrophages dampen the expression of CXCL9 and CXCL10 [39], which along with CXCL11, are chemokines that are up-regulated in the colonic mucosa of patients with inflamed IBD [40] and attract activated Th1 cells expressing high levels of CXCR3. Of particular interest to our studies is the finding that blockade of the CXCR3 axis could mitigate symptoms of colitis in experimental models [41, 43, 66]. As such, the effects of APP upon CXCL9–11 mRNA expression in the colons of mice with colitis were assessed. Although APP significantly diminished the mRNA expression of CXCL9–11 in WT mice, no effect of APP was observed in TCRα−/− mice. CXCL9–11 are all induced by IFN-γ [41], which was suppressed during colitis in WT but not in TCRα−/− mice following treatment with APP. This finding could explain the differential effects of APP on CXCL9–11 expression in the colons of the two strains of mice. As CXCL9–11 can recruit CXCR3+ T cells, which are more colitogenic than their CXCR3– counterparts [67], we sought to determine if APP diminished CXCR3 expression by T cells in the colons of mice with colitis. CXCR3 expression was diminished on CD8+ and more notably, on CD4+ T cells in mice treated with APP during colitis. However, CXCR3 expression on B and NK cells was not affected by APP. We showed previously that APP does not require IL-10 to confer protection against colitis, and others have demonstrated that interfering with CXCR3 signaling can protect against rodent models of colitis even in the absence of IL-10 [43, 68]. This may explain why TCRαβ cells are required for APP-mediated protection, as possibly APP may protect against colitis by suppressing the recruitment of colitogenic CXCR3+ T cells to the colon. In addition, it may explain why depletion of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells alone did not abrogate APP-mediated protection. In the absence of a CD4+ or CD8+ T cell subset, it is possible that colitogenic CXCR3+ T cells of the remaining subset mediate colitis, whereas their recruitment or expansion in the colon of APP-treated mice is suppressed. However, the colitis observed here in TCRαβ cell-deficient mice is a result of T cell-independent factors, which appear to be unaffected by APP. CXCR3 also promotes colon cancer metastasis, and patients with CXCR3-positive colon cancer epithelial cells have a more inferior prognosis than those whose cancer does not express CXCR3 [69]; therefore, CXCR3 inhibition by APP could potentially be beneficial in cases of colon cancer as well.

In summary, administration of APPs provided protection against experimental colitis. Oral, but not systemic, treatment of mice with APP conferred protection against colitis and dampened proinflammatory cytokine expression in colons and MLNs of treated mice. Investigation of the cell types and cytokines required for APP to confer protection against colitis revealed that although IL-10, B cells, and γδ Τ cells were dispensable for APP-mediated protection, TCRαβ cells were required. In the absence of TCRαβ cells, the administration of APP to mice with colitis actually exacerbated MLN proinflammatory cytokine production. Although it is well known that polyphenols can ameliorate animal models of colitis, previous studies on the mechanism of polyphenol action have focused on antioxidant activity. However, this study is the first to demonstrate a requirement for TCRαβ cells in polyphenol-mediated protection against colitis. Although we did not define a specific T cell subset that mediates APP protection, CXCR3 expression was shown to be diminished by TCRαβ cells in the colons of mice with colitis. Thus, APP may mediate protection against colitis by inhibiting the recruitment of CXCR3+ TCRαβ cells to the colon. Collectively, the results demonstrate that oral administration of APP can protect against colitis and could serve as a complementary or alternative therapy to augment treatment of colitis, particularly in those cases refractory to IL-10-targeted treatments. The incorporation of APP into therapeutic regimens for colitis may also reduce the risk of colon cancer, which is associated with colitis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by NIH/NCCAM P01 AT004986 and NIH contract HHSN2662004000009/N01-AI40009. μMT mice were a gift from Dr. Allen Harmsen (Montana State University), and Rag-1−/− mice were a gift from Dr. Nicole Meissner (Montana State University). We thank Dr. Gary D. Stoner, Professor of Medicine (Medical College of Wisconsin), for his insightful comments about this manuscript and Ms. Nancy Kommers for her assistance in preparing this manuscript.

SEE CORRESPONDING EDITORIAL ON PAGE 1037

- APP

- apple polyphenol

- CM

- complete media

- cm

- centimeter

- DSS

- dextran sulfate sodium

- ebi3

- EBV-induced gene 3

- FoxP3

- forkhead box P3

- IBD

- inflammatory bowel disease

- IRF-1

- IFN regulatory factor 1

- KPi

- potassium phosphate

- LP

- lamina propria

- MLN

- mesenteric LN

- NO2–

- nitrite ion

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR

- Rag-1

- recontribution activating gene 1

- UC

- ulcerative colitis

AUTHORSHIP

J.A.S. designed the study, performed laboratory experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote the paper. A.R., S.G., M.F.R., G.C., and E.H. performed laboratory experiments. I.K. analyzed the results. M.A.J. designed the study and analyzed the results. D.W.P. designed the study, analyzed the results, and wrote the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1. Larrosa M., Luceri C., Vivoli E., Pagliuca C., Lodovici M., Moneti G., Dolara P. (2009) Polyphenol metabolites from colonic microbiota exert anti-inflammatory activity on different inflammation models. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 53, 1044–1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Montrose D. C., Horelik N. A., Madigan J. P., Stoner G. D., Wang L. S., Bruno R. S., Park H. J., Giardina C., Rosenberg D. W. (2011) Anti-inflammatory effects of freeze-dried black raspberry powder in ulcerative colitis. Carcinogenesis 32, 343–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Larrosa M., Tome-Carneiro J., Yanez-Gascon M. J., Alcantara D., Selma M. V., Beltran D., Garcia-Conesa M. T., Urban C., Lucas R., Tomas-Barberan F., Morales J. C., Espín J. C. (2010) Preventive oral treatment with resveratrol pro-prodrugs drastically reduce colon inflammation in rodents. J. Med. Chem. 53, 7365–7376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sánchez-Fidalgo S., Cardeno A., Villegas I., Talero E., de la Lastra C. A. (2010) Dietary supplementation of resveratrol attenuates chronic colonic inflammation in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 633, 78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Torres M. I., Rios A. (2008) Current view of the immunopathogenesis in inflammatory bowel disease and its implications for therapy. World J. Gastroenterol. 14, 1972–1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vowinkel T., Kalogeris T. J., Mori M., Krieglstein C. F., Grange D. N. (2004) Impact of dextran sulfate sodium load on the severity of inflammation in experimental colitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 49, 556–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Singh U. P., Singh N. P., Singh B., Hofseth L. J., Price R. L., Nagarkatti M., Nagarkatti P. S. (2010) Resveratrol (trans-3,5,4′-trihydroxystilbene) induces silent mating type information regulation-1 and down-regulates nuclear transcription factor-κB activation to abrogate dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 332, 829–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holländer G. A., Simpson S. J., Mizoguchi E., Nichogiannopoulou A., She J., Gutierrez-Ramos J. C., Bhan A. K., Burakoff S. J., Wang B., Terhorst C. (1995) Severe colitis in mice with aberrant thymic selection. Immunity 3, 27–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen Y., Chou K., Fuchs E., Havran W. L., Boismenu R. (2002) Protection of the intestinal mucosa by intraepithelial γδ T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 14338–14343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kühl A. A., Pawlowski N. N., Grollich K., Loddenkemper C., Zeitz M., Hoffmann J. C. (2007) Aggravation of intestinal inflammation by depletion/deficiency of γδ T cells in different types of IBD animal models. J. Leukoc. Biol. 81, 168–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tsuchiya T., Fukuda S., Hamada H., Nakamura A., Kohama Y., Ishikawa H., Tsujikawa K., Yamamoto H. (2003) Role of γδ T cells in the inflammatory response of experimental colitis mice. J. Immunol. 171, 5507–5513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Andoh A., Ogawa A., Bamba S., Fujiyama Y. (2007) Interaction between interleukin-17-producing CD4+ T cells and colonic subepithelial myofibroblasts: what are they doing in mucosal inflammation? J. Gastroenterol. 42 (Suppl. 17), 29–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fujino S., Andoh A., Bamba S., Ogawa A., Hata K., Araki Y., Bamba T., Fujiyama Y. (2003) Increased expression of interleukin 17 in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 52, 65–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ito R., Shin-Ya M., Kishida T., Urano A., Takada R., Sakagami J., Imanishi J., Kita M., Ueda Y., Iwakura Y., Kataoka K., Okanoue T., Mazda O. (2006) Interferon- γ is causatively involved in experimental inflammatory bowel disease in mice. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 146, 330–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ito R., Kita M., Shin-Ya M., Kishida T., Urano A., Takada R., Sakagami J., Imanishi J., Iwakura Y., Okanoue T., Yoshikawa T., Kataoka K., Mazda O. (2008) Involvement of IL-17A in the pathogenesis of DSS-induced colitis in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 377, 12–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kwon K. H., Murakami A., Hayashi R., Ohigashi H. (2005) Interleukin-1β targets interleukin-6 in progressing dextran sulfate sodium-induced experimental colitis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 337, 647–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Obermeier F., Kojouharoff G., Hans W., Scholmerich J., Gross V., Falk W. (1999) IFN-γ- and TNF-induced nitric oxide as toxic effector molecule in chronic dextran sulphate sodium-induced colitis in mice. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 116, 238–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Naito Y., Takagi T., Uchiyama K., Kuroda M., Kokura S., Ichikawa H., Yanagisawa R., Inoue K., Takano H., Satoh M., Yoshida N., Okanoue T., Yoshikawa T. (2004) Reduced intestinal inflammation induced by dextran sodium sulfate in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Int. J. Mol. Med. 14, 191–196 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Neuman M. G. (2007) Immune dysfunction in inflammatory bowel disease. Transl. Res. 149, 173–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holderness J., Hedges J. F., Daughenbaugh K., Kimmel E., Graff J., Freedman B., Jutila M. A. (2008) Response of γδ T cells to plant-derived tannins. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 28, 377–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Graff J. C., Jutila M. A. (2007) Differential regulation of CD11b on γδ T cells and monocytes in response to unripe apple polyphenols. J. Leukoc. Biol. 82, 603–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Holderness J., Jackiw L., Kimmel E., Kerns H., Radke M., Hedges J. F., Petrie C., McCurley P., Glee P. M., Palecanda A., Jutila M. A. (2007) Select plant tannins induce IL-2Rα up-regulation and augment cell division in γδ T cells. J. Immunol. 179, 6468–6478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Akiyama H., Sato Y., Watanabe T., Nagaoka M. H., Yoshioka Y., Shoji T., Kanda T., Yamada K., Totsuka M., Teshima R., Sawada J., Goda Y., Maitani T. (2005) Dietary unripe apple polyphenol inhibits the development of food allergies in murine models. FEBS Lett. 579, 4485–4491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mazzon E., Muia C., Paola R. D., Genovese T., Menegazzi M., De Sarro A., Suzuki H., Cuzzocrea S. (2005) Green tea polyphenol extract attenuates colon injury induced by experimental colitis. Free Radic. Res. 39, 1017–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Martín A. R., Villegas I., La Casa C., de la Lastra C. A. (2004) Resveratrol, a polyphenol found in grapes, suppresses oxidative damage and stimulates apoptosis during early colonic inflammation in rats. Biochem. Pharmacol. 67, 1399–1410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maity S., Ukil A., Karmakar S., Datta N., Chaudhuri T., Vedasiromoni J. R., Ganguly D. K., Das P. K. (2003) Thearubigin, the major polyphenol of black tea, ameliorates mucosal injury in trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 470, 103–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Varilek G. W., Yang F., Lee E. Y., deVilliers W. J., Zhong J., Oz H. S., Westberry K. F., McClain C. J. (2001) Green tea polyphenol extract attenuates inflammation in interleukin-2-deficient mice, a model of autoimmunity. J. Nutr. 131, 2034–2039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haqqi T. M., Anthony D. D., Gupta S., Ahmad N., Lee M. S., Kumar G. K., Mukhtar H. (1999) Prevention of collagen-induced arthritis in mice by a polyphenolic fraction from green tea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 4524–4529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yoshioka Y., Akiyama H., Nakano M., Shoji T., Kanda T., Ohtake Y., Takita T., Matsuda R., Maitani T. (2008) Orally administered apple procyanidins protect against experimental inflammatory bowel disease in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 8, 1802–1807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schmittgen T. D., Livak K. J. (2008) Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1101–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kochetkova I., Golden S., Holderness K., Callis G., Pascual D. W. (2010) IL-35 stimulation of CD39+ regulatory T cells confers protection against collagen II-induced arthritis via the production of IL-10. J. Immunol. 184, 7144–7153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ochoa-Repáraz J., Rynda A., Ascón M. A., Yang X., Kochetkova I., Riccardi C., Callis G., Trunkle T., Pascual D. W. (2008) IL-13 production by regulatory T cells protects against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis independently of autoantigen. J. Immunol. 181, 954–968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kochetkova I., Trunkle T., Callis G., Pascual D. W. (2008) Vaccination without autoantigen protects against collagen II-induced arthritis via immune deviation and regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 181, 2741–2752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ochoa-Repáraz J., Riccardi C., Rynda A., Jun S., Callis G., Pascual D. W. (2007) Regulatory T cell vaccination without autoantigen protects against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 178, 1791–1799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pascual D. W., Trunkle T., Sura J. (2002) Fimbriated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium abates initial inflammatory responses by macrophages. Infect. Immun. 70, 4273–4281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Csencsits K. L., Pascual D. W. (2002) Absence of L-selectin delays mucosal B cell responses in nonintestinal effector tissues. J. Immunol. 169, 5649–5659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pascual D. W., White M. D., Larson T., Walters N. (2001) Impaired mucosal immunity in L-selectin-deficient mice orally immunized with a Salmonella vaccine vector. J. Immunol. 167, 407–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Siegmund B., Sennello J. A., Lehr H. A., Senaldi G., Dinarello C. A., Fantuzzi G. (2004) Frontline: interferon regulatory factor-1 as a protective gene in intestinal inflammation: role of TCR γδ T cells and IL-18-binding protein. Eur. J. Immunol. 34, 2356–2364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jung M., Triebel S., Anke T., Richling E., Erkel G. (2009) Influence of apple polyphenols on inflammatory gene expression. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 53, 1263–1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hosomi S., Oshitani N., Kamata N., Sogawa M., Okazaki H., Tanigawa T., Yamagami H., Watanabe K., Tominaga K., Watanabe T., Fujiwara Y., Maeda K., Hirakawa K., Arakawa T. (2011) Increased numbers of immature plasma cells in peripheral blood specifically overexpress chemokine receptor CXCR3 and CXCR4 in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 163, 215–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Singh U. P., Venkataraman C., Singh R., Lillard J. W., Jr. (2007) CXCR3 axis: role in inflammatory bowel disease and its therapeutic implication. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 7, 111–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sasaki S., Yoneyama H., Suzuki K., Suriki H., Aiba T., Watanabe S., Kawauchi Y., Kawachi H., Shimizu F., Matsushima K., Asakura H., Narumi S. (2002) Blockade of CXCL10 protects mice from acute colitis and enhances crypt cell survival. Eur. J. Immunol. 32, 3197–3205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Singh U. P., Singh S., Singh R., Cong Y., Taub D. D., Lillard J. W., Jr. (2008) CXCL10-producing mucosal CD4+ T cells, NK cells, and NKT cells are associated with chronic colitis in IL-10−/− mice, which can be abrogated by anti-CXCL10 antibody inhibition. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 28, 31–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Engel M. A., Neurath M. F. (2010) New pathophysiological insights and modern treatment of IBD. J. Gastroenterol. 45, 571–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Head K., Jurenka J. S. (2004) Inflammatory bowel disease. Part II: Crohn's disease—pathophysiology and conventional and alternative treatment options. Altern. Med. Rev. 9, 360–401 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Head K. A., Jurenka J. S. (2003) Inflammatory bowel disease Part 1: ulcerative colitis—pathophysiology and conventional and alternative treatment options. Altern. Med. Rev. 8, 247–283 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kürbitz C., Heise D., Redmer T., Goumas F., Arlt A., Lemke J., Rimbach G., Kalthoff H., Trauzold A. (2011) Epicatechin gallate and catechin gallate are superior to epigallocatechin gallate in growth suppression and anti-inflammatory activities in pancreatic tumor cells. Cancer Sci. 102, 728–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ganapathy S., Chen Q., Singh K. P., Shankar S., Srivastava R. K. (2010) Resveratrol enhances antitumor activity of TRAIL in prostate cancer xenografts through activation of FOXO transcription factor. PLoS ONE 5, e15627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kawai K., Tsuno N. H., Kitayama J., Okaji Y., Yazawa K., Asakage M., Hori N., Watanabe T., Takahashi K., Nagawa H. (2004) Epigallocatechin gallate attenuates adhesion and migration of CD8+ T cells by binding to CD11b. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 113, 1211–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yen D., Cheung J., Scheerens H., Poulet F., McClanahan T., McKenzie B., Kleinschek M. A., Owyang A., Mattson J., Blumenschein W., Murphy E., Sathe M., Cua D. J., Kastelein R. A., Rennick D. (2006) IL-23 is essential for T cell-mediated colitis and promotes inflammation via IL-17 and IL-6. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 1310–1316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Te Velde A. A., de Kort F., Sterrenburg E., Pronk I., ten Kate F. J., Hommes D. W., van Deventer S. J. (2007) Comparative analysis of colonic gene expression of three experimental colitis models mimicking inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 13, 325–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sugimoto K., Ogawa A., Mizoguchi E., Shimomura Y., Andoh A., Bhan A. K., Blumberg R. S., Xavier R. J., Mizoguchi A. (2008) IL-22 ameliorates intestinal inflammation in a mouse model of ulcerative colitis. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 534–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shoji T., Masumoto S., Moriichi N., Akiyama H., Kanda T., Ohtake Y., Goda Y. (2006) Apple procyanidin oligomers absorption in rats after oral administration: analysis of procyanidins in plasma using the porter method and high-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 54, 884–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shanafelt T. D., Call T. G., Zent C. S., LaPlant B., Bowen D. A., Roos M., Secreto C. R., Ghosh A. K., Kabat B. F., Lee M. J., Yang C. S., Jelinek D. F., Erlichman C., Kay N. E. (2009) Phase I trial of daily oral Polyphenon E in patients with asymptomatic Rai stage 0 to II chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 3808–3814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pils M. C., Bleich A., Prinz I., Fasnacht N., Bollati-Fogolin M., Schippers A., Rozell B., Muller W. (2011) Commensal gut flora reduces susceptibility to experimentally induced colitis via T-cell-derived IL-10. Inflamm. Bowel Dis., Epub ahead of print [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Correa I., Veny M., Esteller M., Pique J. M., Yague J., Panes J., Salas A. (2009) Defective IL-10 production in severe phenotypes of Crohn's disease. J. Leukoc. Biol. 85, 896–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Santaolalla R., Mane J., Pedrosa E., Loren V., Fernandez-Banares F., Mallolas J., Carrasco A., Salas A., Rosinach M., Forne M., Espinos J. C., Loras C., Donovan M., Puig P., Manosa M., Gassull M. A., Viver J. M., Esteve M. (2010) Apoptosis resistance of mucosal lymphocytes and IL-10 deficiency in patients with steroid-refractory Crohn's disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis., Epub ahead of print [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mizoguchi E., Mizoguchi A., Preffer F. I., Bhan A. K. (2000) Regulatory role of mature B cells in a murine model of inflammatory bowel disease. Int. Immunol. 12, 597–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Abboud P. A., Hake P. W., Burroughs T. J., Odoms K., O'Connor M., Mangeshkar P., Wong H. R., Zingarelli B. (2008) Therapeutic effect of epigallocatechin-3-gallate in a mouse model of colitis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 579, 411–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Nancey S., Boschetti G., Hacini F., Sardi F., Durand P. Y., Le Borgne M., Furhmann L., Flourie B., Kaiserlian D. (2011) Blockade of LTB4 /BLT1 pathway improves CD8+ T-cell-mediated colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 17, 279–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hacini-Rachinel F., Nancey S., Boschetti G., Sardi F., Doucet-Ladeveze R., Durand P. Y., Flourie B., Kaiserlian D. (2009) CD4+ T cells and Lactobacillus casei control relapsing colitis mediated by CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 183, 5477–5486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Liu Z., Geboes K., Colpaert S., Overbergh L., Mathieu C., Heremans H., de Boer M., Boon L., D'Haens G., Rutgeerts P., Ceuppens J. L. (2000) Prevention of experimental colitis in SCID mice reconstituted with CD45RBhigh CD4+ T cells by blocking the CD40-CD154 interactions. J. Immunol. 164, 6005–6014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ford McIntyre M. S., Young K. J., Gao J., Joe B., Zhang L. (2008) Cutting edge: in vivo trogocytosis as a mechanism of double negative regulatory T cell-mediated antigen-specific suppression. J. Immunol. 181, 2271–2275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chen W., Ford M. S., Young K. J., Zhang L. (2004) The role and mechanisms of double negative regulatory T cells in the suppression of immune responses. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 1, 328–335 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Chen W., Ford M. S., Young K. J., Zhang L. (2003) Infusion of in vitro-generated DN T regulatory cells induces permanent cardiac allograft survival in mice. Transplant. Proc. 35, 2479–2480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tokuyama H., Ueha S., Kurachi M., Matsushima K., Moriyasu F., Blumberg R. S., Kakimi K. (2005) The simultaneous blockade of chemokine receptors CCR2, CCR5 and CXCR3 by a non-peptide chemokine receptor antagonist protects mice from dextran sodium sulfate-mediated colitis. Int. Immunol. 17, 1023–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kristensen N. N., Gad M., Thomsen A. R., Lu B., Gerard C., Claesson M. H. (2006) CXC chemokine receptor 3 expression increases the disease-inducing potential of CD4+. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 12, 374–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Singh U. P., Singh S., Taub D. D., Lillard J. W., Jr. (2003) Inhibition of IFN-γ-inducible protein-10 abrogates colitis in IL-10−/− mice. J. Immunol. 171, 1401–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kawada K., Hosogi H., Sonoshita M., Sakashita H., Manabe T., Shimahara Y., Sakai Y., Takabayashi A., Oshima M., Taketo M. M. (2007) Chemokine receptor CXCR3 promotes colon cancer metastasis to lymph nodes. Oncogene 26, 4679–4688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.