TRAF3 decreases B-cell early signals and downstream functions in response to Toll-like receptors.

Keywords: lymphocyte activation, innate immunity, signal transduction

Abstract

The key role of TRAF6 in TLR signaling pathways is well known. More recent evidence has implicated TRAF3 as another TRAF family member important to certain TLR responses of myeloid cells. Previous studies demonstrate that TRAF3 functions are highly context-dependent, displaying receptor and cell-type specificity. We thus examined the TLR responses of TRAF3−/−mouse B lymphocytes to test the hypothesis that TRAF3 plays distinct roles in such responses, depending on cell type. TRAF3−/− DC are known to have a defect in type 1 IFN production and here, showed diminished production of TNF and IL-10 and unaltered IL-6. In marked contrast, TRAF3−/− B cells made elevated amounts of TNF and IL-6 protein, as well as IL-10 and IP-10 mRNA, in response to TLR ligands. Also, in contrast to TRAF3−/− DC, the type 1 IFN pathway was elevated in TRAF3−/− B cells. Increased early responses of TRAF3−/− B cells to TLR signals were independent of cell survival or proliferation but associated with elevated canonical NF-κB activation. Additionally, TRAF3−/− B cells displayed enhanced TLR-mediated expression of AID and Ig isotype switching. Thus, TRAF3 plays varied and cell type-specific, biological roles in TLR responses.

Introduction

TLRs are a large family, mediating signals important to development of the innate immune response [1]. It has been known for over one decade that one of the key players in TLR signaling is a member of the TRAF adaptor protein family, TRAF6 [2]. For many years after this discovery, TRAF6 was the only TRAF implicated in TLR signaling pathways, and other TRAFs were known primarily for their roles as adapters, which associate directly with cell surface receptors of the TNFR superfamily [3]. However, reports published in 2006 indicate a role for TRAF3 in regulating a subset of TLR signals delivered to macrophages and DCs [4, 5], and this role was validated recently in a rare human disorder featuring a loss-of-function TRAF3 allele [6]. These signals are primarily implicated in TLR influence, particularly TLR3, on type 1 IFN production and antiviral responses.

TLRs play major roles in regulating the function of cells of the myeloid lineage, so it is not surprising that the majority of studies of TLR function focuses on these cells [7–9]. However, B lymphocytes also express most of the known TLRs and are highly responsive to TLR ligands [10]. TLR signaling to B cells has also been associated with autoimmune disease [11, 12]. Recently, it was shown that B cells play an important role in innate-protective responses to bacterial sepsis [13]. Thus, it is important to understand how TLRs signal and function in the B cell component of innate and adaptive immune responses.

It has become clear over the years since their discovery that TRAFs function in a manner strongly influenced by cell type, stimulating receptor(s), and the presence or absence of additional TRAF family members and other proteins in the signaling complex [14]. TRAF3 function appears to be particularly context-dependent. TRAF3, in contrast to TRAF2, -5, and -6, does not activate a NF-κB reporter gene when overexpressed in the 293 epithelial cell line [15–18]. In these cells, transfected TRAF3 also inhibits TRAF2 and TRAF5 overexpression-mediated, noncanonical NF-κB2 activation associated with a variety of transfected TNFR superfamily members [19]. In B lymphocytes, endogenous TRAF3 serves as an inhibitor of TRAF2-dependent CD40 signals [20, 21], as well as BAFF-R signals [22, 23]. In sharp contrast, TRAF3 is a key positive regulator of signals delivered to B cells by the EBV-encoded CD40 mimic and latent membrane protein 1 [24] and of signals delivered to 293 cells by a transfected ectodermal dysplasia receptor [25]. Interestingly, a novel human CD40 polymorphism that confers a gain-of-function to B cells in vitro [26] also uses and requires TRAF3 as an inducer rather than inhibitor of CD40 signals [27]. TRAF3 is also important to apoptotic signals mediated by the lymphotoxin-β receptor [28]. TRAF3 expression in B cells plays a critical restraining role in B cell survival and homeostasis [23, 29], which may be related to its ability in this cell type to negatively regulate the noncanonical NF-κB2 pathway [19, 23, 29, 30]. TRAF3−/− T lymphocytes also display increased NF-κB2 activation. However, in marked contrast to TRAF3−/− B cells, mice lacking TRAF3 specifically in T cells have impaired CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses and display defects in early TCR signaling [31].

Given the varied roles played by TRAF3 in immune cells, an important knowledge gap includes the distinct functions of TRAF3 in TLR signaling to B cells. To address this question, we examined TLR-mediated functions in B cells from TRAF3-conditional knockout mice [23]. We determined that most TLR-mediated signals and functions in B cells, in contrast to several of those reported previously for myeloid cells, were markedly enhanced in TRAF3−/− B cells, in a survival-independent manner. This elevation was seen in MZ and non-MZ B cells. Additionally, TLR-mediated Ig isotype switching and production of AID, a key enzyme involved in combinatorial switch recombination, were elevated in TRAF3−/− B cells. These results add new information to understanding the pleiotropic functions of this interesting and functionally important adaptor protein in cells of the immune system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

TRAF3flox/flox mice [23] were crossed with CD19+/Cre mice [32] obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and subsequently backcrossed onto TRAF3flox/flox mice, as described previously, to produce B cell-specific B-TRAF3−/− mice [23]. To create a DC-TRAF3−/− mouse, TRAF3flox/flox mice were crossed with CD11c-Cre mice [33] provided by Dr. Richard Hodes (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) with permission from Dr. Boris Rezis (Columbia University, New York, NY, USA), and it was verified that DCs from these mice are TRAF3−/−. The phenotype of these mice will be described in detail elsewhere (unpublished results); they breed and develop normally. The mice are on a mixed genetic background between 129/SvJ and C57Bl/6, and Cre-negative littermates, designated LMC, were used as controls in all experiments.

Cell purification

BMDCs were generated by culturing RBC-depleted BM cells in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS, penicillin/streptomycin, 10 μM 2-ME, 1000 U/ml rGM-CSF, and 25 U/ml rIL-4 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). BMDCs were harvested on Day 10 of culture and were purified further using anti-CD11c, mAb-conjugated microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA). The purified BMDCs were >90% CD11c+, as assessed by flow cytometric analysis. Resting splenic B cells were purified by Percoll density gradient centrifugation as described previously [23], followed by negative selection using anti-mouse CD43-coated magnetic beads and a MACS separator (Miltenyi Biotec), as recommended by the manufacturer. The purified B cells were >95% B220+, as assessed by flow cytometric analysis of stained cells.

Cell sorting

Splenocytes from 2- to 3-month-old LMC or B-TRAF3−/− mice were stained with the fluorescent antibodies rat anti-B220-allophycocyanin (clone RA3-6B2, eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) and rat anti-CD1d-FITC (clone 1B1, BD PharMingen, Mountain View, CA, USA) at 0.07 ug/106 cells. Cells were sorted into B220+CD1dhi and B220+CD1dlo populations using a BD FACSDiva at The University of Iowa Flow Cytometry Facility (Iowa City, IA, USA). MZ B cells are CD1dhi [34]. Following the sort, MZ and non-MZ B cells were equilibrated on ice for 1 h, after which, TLR stimuli were added.

TLR ligands

TLR agonists used were: TLR3 = poly(I:C), 5 ug/ml for B cells; 30 μg/ml for DCs (Invivogen, San Diego, CA, USA); TLR2/4 = LPS 0111:B4, 20 ug/ml for B cells or 1 ug/ml for BMDCs (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO, USA); TLR7 = R848, 100 ng/ml (Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA, USA); TLR9 = 100 nM phosphorothioate oligonucleotide CpG 1826 (for DCs) or CpG 2084 (for B cells; Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA) [35].

Antibodies

Antibodies specific for phospho-IκBα and phospho-IRF3 (Ser396) were from Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA, USA). Antibodies to TRAF3 and YY1 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Antibody to actin was from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA, USA). Antibody to AID and anti-mouse TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-12p40 ELISA antibody pairs were from eBioscience. The agonistic anti-CD40 mAb, used as a control in Ig isotype-switching experiments, was HM 40-3 (eBioscience). Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated polyclonal goat antibodies specific for mouse IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, IgA, and IgE were from Southern Biotechnology Associates (Birmingham, AL, USA).

Cytokine ELISA assays

Purified, resting splenic B cells, unseparated or sorted as above, were cultured in 96-well plates at 1 × 106 cells/ml in 0.2 ml vol RPMI-1640 culture medium, supplemented with 5% FCS, 10 μM 2-ME, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.55), 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (BCM). BMDCs were cultured at 5 × 105 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, penicillin/streptomycin, and 2-ME. As designated in figures, some cultures included TLR agonists, agonistic anti-mouse CD40 mAb (HM40.3, eBioscience), and/or rmIL-4 (100 ng/ml; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). Quantitative mouse IL-6, IL-12, IL-10, and TNF-α ELISAs were performed on 24-h DC culture supernatants [72h for poly (I:C)] as described previously [36]. B cell cytokine production was assessed similarly, except for TNF-α production. To measure TNF-α, B cells were resuspended in BCM with 10% FCS (1×106 cells/ml) following the wash, rested for 1 h, and then placed in an anti-TNF-α-coated 96-well flat-bottom plate with the appropriate antibodies. This ″in-plate″ assay is necessary, as B cells express TNFR2 and rapidly bind the TNF-α, which they secrete. Thus, TNF ELISAs were performed on supernatants of cells cultured for 4 h as described previously [37].

Western blots

For detection of phospho-IRF3 and AID in LMC or TRAF3−/− B cells, purified, resting splenic B cells (0.5×106 cells/ml) were cultured in 24-well plates, with or without 20 μg/ml poly(I:C) or 100 nM CpG 2084 and 100 ng/ml rIL-4. Nuclear extracts were prepared from cells for detection of phospho-IRF3 as described [38]. Whole cell lysates were prepared for AID experiments. Cells were resuspended in 2× SDS lysis buffer and sonicated, and phospho- and total IκBα were detected as described [38]. Actin blotting was used as a loading control, and total protein amounts were determined for equal lane loading using the BCA assay from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA).

Taqman assay of IL-10 and IP-10 mRNA expression

Splenic B cells were purified using negative selection with CD43 beads, as described above, and then stimulated with TLR ligands, as detailed above for 0, 2, or 4 h. Total cellular RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was prepared from RNA using the high-capacity cDNA RT kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the TaqMan gene assay kit (Applied Biosystems). TaqMan primers and probes (FAM-labeled) specific for individual mouse cytokines were used in the PCR reaction to detect IL-10 or IP-10 mRNA. Reactions were performed on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Each reaction also included primers and the probe (2′-chloro-7′-phenyl-1,4-dichloro-6-carboxyfluorescein-labeled) specific for mouse β-actin mRNA, which served as endogenous control. Relative mRNA expression levels of cytokines were analyzed using sequencing detection software (Applied Biosystems) and the ΔΔ Ct, comparative Ct threshold method following the manufacturer's procedures. For each biological sample, duplicate PCR reactions were performed.

Ig isotype production

To detect TLR-driven isotype-switched Ig production, B cells were cultured in the presence of TLR agonists or as a positive control, agonistic antimouse CD40 mAb + rmIL-4 (100 ng/ml; PeproTech) for 5 days. Culture supernatants were assayed by ELISA for individual Ig isotypes using isotype-specific reagents from Southern Biotechnology Associates, according to the manufacturer's protocols as described previously [23].

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed by Student's t test. P values are indicated in figures above bar graphs by asterisks: *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001.

RESULTS

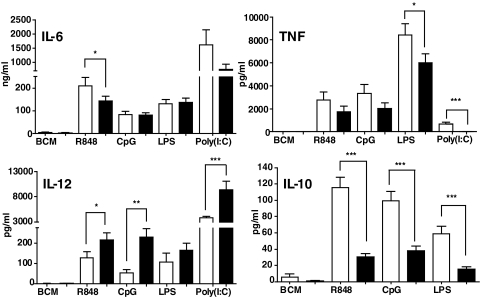

Effect of TRAF3 deficiency on TLR-mediated proinflammatory cytokine production by DCs versus B cells

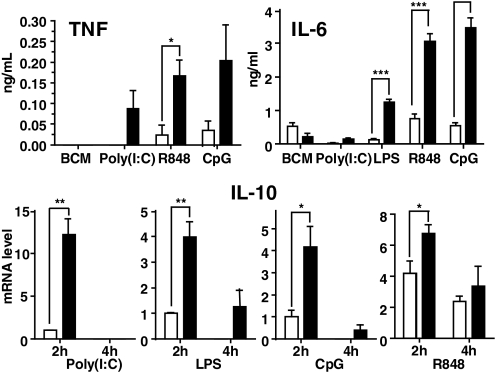

As deletion of TRAF3 from all cells of a mouse is neonatally lethal [39], previous studies reconstituted WT mice with TRAF3−/− BM. BM-derived macrophages from the recipients produce elevated IL-12, thought to result from reduced IL-10, in response to ligands for TLR4 and TLR9 [4]. In the present study, BMDCs from DC-TRAF3−/− mice also produced elevated IL-12 and decreased IL-10 compared with DCs from their LMC counterparts in response to ligands for TLR4, -7, and -9 (Fig. 1). To directly compare TRAF3−/− DCs with TRAF3–/– B cells, we examined two proinflammatory cytokines measurably produced as secreted protein by both cell types in culture upon TLR stimulation, TNF-α and IL-6. Fig. 1 shows that TRAF3 deficiency resulted in partial but reproducible decreases in TNF-α production by BMDCs in response to TLR ligands. TRAF3−/− DCs showed no significant change in IL-6 production compared with DCs from LMC mice. In contrast, TRAF3−/− B cells produced markedly elevated amounts of TNF-α and IL-6 in response to TLR stimulation, compared with LMC B cells (Fig. 2, upper panels). Production of both cytokines was assessed at early poststimulation time-points, when there were no detectable differences in cell viability or number between TRAF3−/− and LMC B cells (data not shown). Neither TRAF3−/− nor LMC B cells produced reliably detectable IL-12 in response to the tested TLR ligands (not shown). Interestingly, TRAF3−/− B cells showed an early enhanced production of IL-10 mRNA in response to signals from several TLRs, but this enhancement disappeared or decreased markedly by 4-h poststimulation (Fig. 2, lower panels), and IL-10 protein in B cell cultures was undetectable until 72 h poststimulation, at a time when TRAF3−/− B cells also display a survival advantage [23]. At this late time post-TLR stimulation, TRAF3−/− B cells did not show enhanced IL-10 production (data not shown). Thus, the effect on IL-10 is early and transient. However, it can be concluded that overall, TRAF3 deficiency has markedly different effects upon cytokine production by B cells versus DCs.

Figure 1. Effect of TRAF3 deficiency on TLR-mediated cytokine production by DCs.

BMDCs were isolated and cultured with the indicated stimuli and cytokine production measured, as described in Materials and Methods. Filled bars are data from BMDCs of DC-TRAF3−/− mice, and open bars are data from LMC mice. Data represent the mean values ± sd of three experiments. Statistical analysis was conducted using Student's t test. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

Figure 2. Effect of TRAF3 deficiency on TLR-mediated cytokine production by B cells.

Resting B cells were isolated and cultured + the indicated stimuli and cytokine production measured, as described in Materials and Methods. Measurement of mRNA production for IL-10 was as described in Materials and Methods. Filled bars are data from B cells of B-TRAF3−/− mice, and open bars are data from LMC mice. Data represent the mean values ± sd of three experiments. Statistical analysis was conducted using Student's t test. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

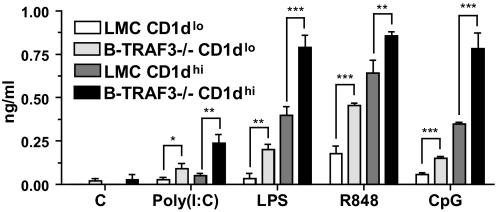

Enhanced cytokine production by MZ and non-MZ B cells in the absence of TRAF3

B-TRAF3−/− mice have increased total B cells, as well as an increased percentage of transitional and MZ B cells [23]. To address the possibility that the increased TLR responses seen in Fig. 2 were a result of an enhanced responsiveness selectively of the MZ B cell subset, we separated MZ and non-MZ B cells as described in Materials and Methods and cultured them with various TLR ligands as in Fig. 2. Data presented in Fig. 3 demonstrate that MZ B cells of LMC and B-TRAF3−/− mice produced more IL-6 than non-MZ B cells in response to all TLR ligands. However, there were statistically significant increases in TLR responses of both subsets of B cells from B-TRAF3−/− mice; their enhanced responses were not confined to the MZ subset. A similar trend was seen in TNF-α production, but TNF production by sorted LMC B cells was too low to quantify reliably (not shown). We also measured protein expression of TLR3 and TLR9 (we could not find reliable antibodies for detecting protein expression of mouse TLR4 or -7) in B cell subsets of LMC and B-TRAF3−/− mice; no differences were seen (not shown).

Figure 3. Effect of TRAF3 deficiency on TLR responses of B cell subsets.

Splenic B cells were isolated from LMC and B-TRAF3−/− mice and then separated by flow cytometric sorting into non-MZ (Cd1dlo) and MZ (CD1dhi) populations, as described in Materials and Methods. Sorted cells were cultured with the indicated stimuli and IL-6 measured as in Fig. 2. Data represent the mean values ± sd of three experiments. Statistical analysis was conducted using Student's t test. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

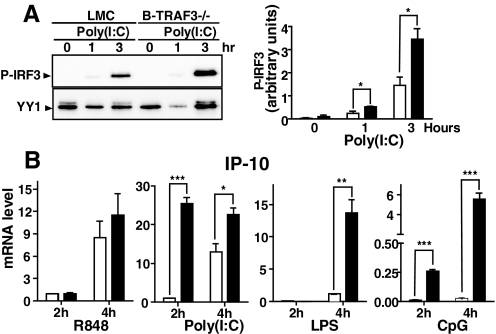

Effect of B cell TRAF3 deficiency on the TLR-mediated type 1 IFN pathway

The predominant effect of TRAF3 deficiency in BM-derived macrophages and DCs from mice adoptively transferred with TRAF3−/− BM is a greatly reduced, TLR3-induced type 1 IFN response [4, 5], which we also observed in DCs from our DC-TRAF3−/− mouse (unpublished results). This specific defect is also implicated in the impaired response to Herpes simplex virus of a patient with TRAF3 deficiency [6]. We thus examined B cells from conditional TRAF3−/− mice for their type 1 IFN pathway response to poly(I:C), a TLR3 ligand. Levels of type 1 IFN protein in B cell culture supernatants were too low to be reliably quantifiable, but we investigated an upstream regulator and a downstream target of the type 1 IFN signaling pathway. Phosphorylation of IRF3, a transcription factor that regulates type I IFN production, proved a useful measure of B cell TLR3 responses. Fig 4A shows that TRAF3−/− B cells exhibited elevated phosphorylation of IRF3 within 1 h of poly(I:C) treatment, and this amount was more than double the phospho-IRF3 produced by LMC B cells after 3 h of TLR3 stimulation. We also measured B cell production of mRNA for the type 1 IFN-regulated chemokine IP-10 in response to all four of the TLR ligands. Fig. 4B shows that TRAF3−/− B cells gave elevated responses at 2 h and 4 h poststimulation (except for LPS, where 2-h measurements were not detectable), compared with responses of LMC B cells. Thus, B cells again showed a divergence from DCs in the role played by TRAF3 in the type 1 IFN pathway in response to TLR stimulation.

Figure 4. Effect of TRAF3 deficiency on activation of the TLR-mediated type 1 IFN pathway in B cells.

B cells from LMC or B-TRAF3−/− mice were cultured with the TLR ligands, indicated as described in Materials and Methods, for the indicated times. For all bar graphs, filled bars represent results from B-TRAF3−/− B cells and open bars data from LMC B cells. (A) Western blots of cell nuclear lysates were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Blotting for the resident nuclear protein YY1 served as a lane-loading control. Data are representative of three similar experiments. Chemiluminescence of phospho-IRF3 (P-IRF3) bands was quantitated and normalized to the intensity of the YY1 band signals in the right bar graph. Graphs depict the results of three independent experiments with duplicate samples in each experiment (mean±sd). (B) mRNA for IP-10 was quantitated as described in Materials and Methods. Graphs depict the results of three independent experiments with duplicate samples in each experiment (mean±sd). Statistical analysis was conducted using Student's t test. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

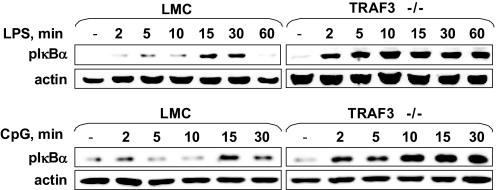

TLR-induced canonical NF-κB1 activation in TRAF3−/− B cells

Although, as discussed above, TRAF3−/− B cells have constitutive activation of the noncanonical NF-κB2 pathway, B cells from B-TRAF3−/− mice show no alteration in CD40-mediated activation of the NF-κB1 pathway [23]. This canonical NF-κB pathway plays an important role in rapid poststimulus production of proinflammatory cytokines and is also activated by TLR signal cascades [40]. Additionally, TRAF3 can associate with components of the TLR-mediated NF-κB1 activation pathway in transformed cell lines [4, 5]. We thus examined activation of the canonical NF-κB1 pathway in TRAF3−/− and LMC B cells stimulated via TLR4 (a membrane TLR) or TLR9 (an intracellular TLR). Fig. 5 demonstrates that IκBα phosphorylation in response to TLR4 (upper panels) or TLR9 (lower panels) was elevated in TRAF3−/− B cells evident as early as 2 min after stimulation. The NF-κB1 response to LPS was also sustained in TRAF3−/− B cells compared with LMC. Thus, in TLR responses, in contrast to CD40 signals, TRAF3−/− deficiency enhanced NF-κB1 activation.

Figure 5. TLR-induced canonical NF-κB1 activation in TRAF3−/− B cells.

B cells were stimulated for the times shown with the indicated TLR ligands. Preparation of whole cell lysates and Western blotting for phospho-IκBα and actin were as described in Materials and Methods. Results are representative of three similar experiments for each TLR ligand used.

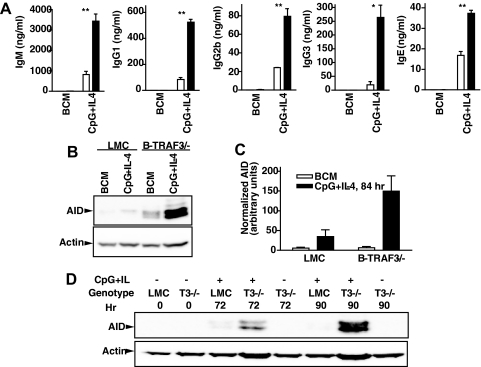

TLR-induced Ig isotype switching in TRAF3−/− B cells

A TLR-induced function unique to B cells is Ig production. Ig isotype switching can be induced by adaptive and innate immune signals to B cells [41–44]. We thus examined the effect of TRAF3 deficiency on TLR-mediated production of various isotypes of Ig by LMC and TRAF3−/− B cells.

Consistent with our previous findings with sera from unimmunized B-TRAF3−/− mice [23], total IgM production was elevated modestly, whereas little IgG1, a predominantly T cell-dependent Ig isotype, was produced in response to TLR ligands (Fig. 6). CD40 + IL-4 stimulation served as a positive control; TRAF3 has been shown to act as an inhibitor of CD40-mediated IgM production [20]. As in mouse sera, B cell in vitro production of other IgG isotypes and IgA in response to TLR ligands was elevated in the absence of TRAF3. Responses to LPS were less-predictable and -consistent than those to other TLR ligands, possibly because LPS can use multiple signaling pathways [9, 45]. However, the general trend that emerged was enhanced production of T-independent Ig isotypes in response to TLR family ligands.

Figure 6. TLR-induced Ig isotype switching in TRAF3−/− B cells.

B cells were cultured with the indicated stimuli and individual Ig isotypes measured by ELISA, as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent the mean values ± sd of triplicate cultures in an experiment representative of three similar experiments. Statistical analysis was conducted using Student's t test. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

TRAF3 deficiency does not cause increased proliferation of B cells but does result in the enhanced ability to survive in the absence of activating stimuli [23]. We did not detect increased numbers of B cells in cultures measured in Fig. 6 (not shown). However, to determine if TLR stimulation of TRAF3−/− B cells increases activity of the isotype-switch process itself, we examined production of AID, a key factor in combinatorial switch recombination of Ig genes [46]. Fig. 7 demonstrates that LMC and TRAF3−/− B cells have enhanced AID production following TLR9 + IL-4 stimulation, but this AID up-regulation was considerably more marked in cells deficient in TRAF3 in relation to production of actin, a ″housekeeping″ protein.

Figure 7. TLR-induced AID production in TRAF3−/− B cells.

B cells were cultured with the indicated stimuli. (A) Measurement of Ig isotypes was as in Fig. 5. (B) B cells were cultured for 84 h prior to cell lysis, SDS-PAGE of lysates, and Western blotting for AID, as described in Materials and Methods. Actin was used as a lane-loading control. (C) Chemiluminescence of AID bands was quantitated and normalized to the intensity of the actin band signals. Data represent mean values ± sd from three experiments. Statistical significance of the difference between stimulated and unstimulated TRAF3−/− B cells by Student's t test was a P value of 0.026. (D) AID levels were tested at two additional time-points: 72 and 90 h of stimulation. Experiments presented are each representative of three similar experiments. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01.

DISCUSSION

The present study showed that signaling by TLR3, -4, -7/8, and -9 in B lymphocytes is elevated in the absence of TRAF3. This indicates that TRAF3 normally constrains signaling by these receptors in B cells, in interesting contrast to its effects on TLR signaling to myeloid cells. TLRs are one of the most important groups of PRRs, and our findings suggest that TRAF3 can play essential roles in modulating innate and humoral immunity in response to pathogen infections that trigger TLRs. Furthermore, the hyper-responsiveness of TRAF3−/− B cells to TLRs may contribute to the autoimmune manifestations observed in B-TRAF3−/− mice as they age [23]. We showed previously that TRAF3−/− B cells, including those producing autoantibodies, exhibit prolonged survival, independent of BAFF. Our present study suggests that autoreactive TRAF3−/− B cells are not only increased in number in the host as a result of this enhanced survival but are also functionally enhanced as a result of amplified responses to signaling by TLRs. This can also contribute to autoimmune manifestations [23].

Our prior studies revealed that B-TRAF3−/− mice have an elevated number and percentage of MZ B cells [23]. Published evidence has indicated that MZ B cells play unique roles in T-independent antibody responses and can interact in distinct ways with DC and T cells (reviewed in ref. [47]). Previous reports show that MZ B cells can produce elevated IL-10 in response to prolonged TLR stimulation [48, 49], and our data expand on this by showing that MZ B cells produce enhanced IL-6 in response to a much-shorter stimulation with ligands for TLR3, -4, -7, and -9. However, this was the case for MZ B cells, whether or not they lack TRAF3, and non-MZ B cells from B-TRAF3−/− mice also produce elevated cytokines in response to TLR stimulation, so the effects of TRAF3 deficiency do not only affect, nor are solely attributable to, the MZ subset.

Results shown here reveal that the roles played by TRAF3 in response to TLR signaling to B lymphocytes are overlapping yet distinct from those that TRAF3 plays in TLR responses of DCs. It has been reported recently that in myeloid cells, the self-catalyzed, K63-linked polyubiquitination of TRAF3 is required for IRF3 activation induced by TLR-Toll/IL-1R domain-containing adaptor-inducing IFN-β signaling [50]. Interestingly, we found that in B cells, IRF3 activation is not abolished but instead enhanced in TRAF3−/− B cells. These results reinforce the concept that TRAF signaling adapters have highly context-dependent functions. In addition to receptor or cell type-specific varied roles of TRAF3 discussed in the Introduction, we now show that in response to the same receptors in different cell types, TRAF3 can exert different and even contrasting effects.

This is the first demonstration, to our knowledge, that TRAF3 can play distinct roles in signaling by the same receptors in different cell types of the immune system. However, there is precedent for such distinction in function in the actions of TRAF2 and -6. CD40-mediated IL-6 production by DCs has been reported to depend on TRAF2 [51], whereas IL-6 induction in B cells by CD40 requires CD40-TRAF6 association but not TRAF2 or -3 [36, 52]. Like B cells, macrophages primarily rely on TRAF6 for IL-6 production, but in contrast to B cells, macrophages show little if any use of TRAF2 in CD40-mediated canonical NF-κB1 activation [53, 54]. As TRAF2 serves as the principal regulator of CD40-induced TRAF2 and -3 degradation in B cells [55, 56], this may explain why CD40 signaling in macrophages does not induce TRAF2 degradation [57]. Finally, in nonimmune cells, TRAF6 appears to be necessary for TRAF2-mediated CD40 induction of kinase and NF-κB activation [58].

Another member of the TNFR superfamily, TNFR2/CD120b, also shows distinct patterns of TRAF use in various cell types. Cooperation between CD40 and CD120b in the induction of B cell Ig production requires TRAF2 [59], whereas in activation of antimicrobial activity in macrophages, cooperation between these two receptors is TRAF6-dependent [60]. A contrasting negative regulatory role in CD120b signaling is played by TRAF2 in the transformed epithelial cell line, 293T [61].

Precisely how TRAFs exert different influences in distinct situations is likely dependent on a number of interacting factors, including the strength and nature of receptor associations, the presence of other TRAFs and additional molecules in the signaling complex, and which additional receptors and intracellular proteins are expressed by the cells under the conditions examined. Our previous work [23] showed that TRAF3 deletion in B cells results in enhanced survival compared with normal mouse B cells, which die rapidly in culture in the absence of stimulation. The noncanonical NF-κB2 pathway, which promotes B cell survival [62], is constitutively activated in TRAF3−/− B cells, although this activation can be enhanced further by CD40 signals [23]. However, this same constitutive NF-κB2 activation is seen TRAF3−/− T cells but without increased cell survival [31]. It was thus important to consider differences in cell number and viability as the explanation for enhanced B cell responses to TLR signals reported here. For many of the parameters measured, we were able to examine cells at early times poststimulation (Figs. 1–5), before any detectable survival advantage is displayed by TRAF3−/− B cells. In experiments examining isotype switching, a process requiring more time (Figs. 6 and 7), we found that TLR stimulation enhanced the survival of LMC B cells as well, so there were no significant differences between B cell number or viability in the experiments shown. The only exception to this was in the unstimulated B cell cultures, and in these samples, we show that no nonspecific elevations in any of the parameters measured were seen in TRAF3−/− B cells.

In response to TLR stimulation, TRAF3−/− B cells showed a marked increase in TLR-induced canonical NF-κB1 activation (Fig. 5), as well as cytokine production (Fig. 2). TRAF3 B cells also displayed enhanced activation of the type 1 IFN pathway (Fig. 4), whereas TRAF3−/− myeloid cells show a very different phenotype [4–6]. It has been hypothesized that TRAF3 plays a key role in NF-κB activation in canonical and noncanonical pathways via its regulation of the NIK [30, 63–65]. However, TRAF3−/− B cells do not display greater constitutive or CD40-mediated canonical NF-κB1 activation than do control B cells [23, 24]. Thus, the TLR specificity of the effect on NF-κB1 activation shown here is unlikely to be explained solely by TRAF3 effects on NIK. As we cannot detect measurable amounts of NIK protein in unstimulated or stimulated B cells used in this study, we cannot yet definitively address its potential involvement. It is interesting to note that in an earlier study, DCs from NF-κB p100-deficient mice, whether or not they lack TRAF3, show the same defect in IFN-α production as TRAF3−/− p100+/+ mice [5], suggesting that elevated nuclear p52 may not explain the differential type 1 IFN response to TLRs.

Another possible mechanism of the specific effects of TRAF3 deficiency on B cell TLR responses reported here is potential interaction between TRAF3 and -6. CD40-mediated canonical NF-κB1 activation [66], IL-6 production [52], and Ig production [52, 67] are all dependent on TRAF6, and these functions are interconnected—IL-6 production requires NF-κB activation and can, in turn, promote Ig production and isotype switching [68, 69]. In B cells, the cell type-specific homeostatic function of TRAF3 may extend to cytoplasmic TRAF6, as heterotypic TRAF interactions are known to occur [38, 70, 71], including TRAF3–6 interactions [66]. CD40 signals induce TRAF3 degradation [72] and cooperate with TLR signals in B cells [73, 74], and it is possible that TRAF3 deficiency releases more TRAF6 to serve TLR signaling pathways. In DCs, in which TRAF3 does not play a negative regulatory role in cell survival, interactions between TRAF3 and other signaling proteins appear to have distinct downstream consequences.

Future studies will seek additional details of the mechanism(s) by which TRAF3 plays distinct roles in different cell types. The work presented here highlights the importance of studying TRAF functions in specific, normal cell types, particularly when contemplating TRAFs as therapeutic targets in malignancy and autoimmune disease, as responses to even the same receptors cannot be extrapolated from one cell type to another. Our present findings also highlight the complex and pleiotropic biology of this fascinating family of signaling proteins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by NIH R01 AI28847 and VA Merit Review 383 to G.A.B. and an American Heart Association National Scientist Development award to P.X. This work was supported in part with resources and the use of facilities at the Iowa City Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Footnotes

- AID

- activation-induced deaminase

- B-TRAF3–/–

- B cell-specific TRAF3-deficient mice

- BAFF-R

- B cell activation factor receptor

- BCM

- B cell medium

- BMDC

- bone marrow-derived DC

- DC-TRAF3–/–

- selectively deleted TRAF3 in DC mice

- IP-10

- IFN-inducible protein 10

- IRF3

- IFN regulatory factor 3

- LMC

- littermate control

- MZ

- marginal zone

- NIK

- NF-κB-inducing kinase

- poly(I:C)

- polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid

- rm

- recombinant mouse

- TRAF3−/−

- TRAF3-deficient

AUTHORSHIP

P.X., J.P., L.L.S., and G.A.B. designed experiments; P.X., J.P., L.L.S., S.M.S., M.L.S., and L.E.C. performed experiments; P.X., J.P., L.L.S., S.M.S., M.L.S., L.E.C., and G.A.B. analyzed and discussed data and prepared figures; and P.X., J.P., L.L.S., S.M.S., and G.A.B. wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aderem A., Ulevitch R. J. (2000) Toll-like receptors in the induction of the innate immune response. Nature 406, 782–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kirschning C. J., Wesche H., Merrill A. T., Rothe M. (1998) Human TLR2 confers responsiveness to bacterial LPS. J. Exp. Med. 188, 2091–2097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arch R. H., Gedrich R. W., Thompson C. B. (1998) TRAFs—a family of adapter proteins that regulates life and death. Genes Dev. 12, 2821–2830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Häcker H., Redecke V., Blagoev B., Kratchmarova I., Hsu L-C., Wang G. G., Kamps M. P., Raz E., Wagner H., Häcker G., Mann M., Karin M. (2006) Specificity in TLR signaling through distinct effector functions of TRAF3 and TRAF6. Nature 439, 204–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oganesyan G., Saha S. K., Guo B., He J. Q., Shahangian A., Zarnegar B., Perry A., Cheng G. (2006) Critical role of TRAF3 in the TLR-dependent and independent antiviral response. Nature 439, 208–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pérez de Diego R., Sancho-Shimizu V., Lorenzo L., Puel A., Plancoulaine S., Picard C., Herman M., Cardon A., Durandy A., Bustamante J., Vallabhapurapu S., Bravo J., Warnatz K., Chaix Y., Cascarrigny F., Lebon P., Rozenberg F., Karin M., Tardieu M., Al-Muhsen S., Jouanguy E., Zhang S-Y., Abel L., Casanova J-L. (2010) Human TRAF3 adaptor molecule deficiency leads to impaired TLR3 response and susceptibility to Herpes simplex encephalitis. Immunity 33, 400–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Akira S. (2003) TLR signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 38105–38108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Takeda K., Akira S. (2005) TLRs in innate immunity. Int. Immunol. 17, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kawai T., Akira S. (2010) The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on TLRs. Nat. Immunol. 11, 373–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peng S. L. (2005) Signaling to B cells by TLRs. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 17, 230–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sabroe I., Read R. C., Whyte M. K. B., Dockrell D. H., Vogel S. N., Dower S. K. (2003) TLRs in health and disease: complex questions remain. J. Immunol. 171, 1630–1635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang Q., Pope R. M. (2010) TLR signaling: a potential link among RA, SLE, and atherosclerosis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 88, 253–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kelly-Scumpia K. M., Scumpia P. O., Weinstein J. S., Delano M. J., Cuenca A. G., Nacionales D. C., Wynn J. L., Lee P. Y., Kumagai Y., Efron P. A., Akira S., Wasserfall C., Atkinson M. A., Moldawer L. L. (2011) B cells enhance early innate immune responses during bacterial sepsis. J. Exp. Med. 208, 1673–1682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bishop G. A. (2004) The multifaceted roles of TRAFs in the regulation of B cell function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 775–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rothe M., Sarma V., Dixit V. M., Goeddel D. V. (1995) TRAF2-mediated activation of NF-κB by TNF receptor 2 and CD40. Science 269, 1424–1427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Devergne O., Hatzivassiliou E., Izumi K. M., Kaye K. M., Kleijnen M. F., Kieff E., Mosialos G. (1996) Association of TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF3 with an EBV LMP1 domain important for B-lymphocyte transformation: role in NF-κB activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 7098–7108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ishida T.., Mizushima S., Azuma S., Kobayashi N., Tojo T., Suzuki K., Aizawa S., Watanabe T., Mosialos G., Kieff E., Yamamoto T., Inoue J. (1996) Identification of TRAF6, a novel TRAF protein that mediates signaling from an amino-terminal domain of the CD40 cytoplasmic region. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 28745–28748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ishida T. K.., Tojo T., Aoki T., Kobayashi N., Ohishi T., Watanabe T., Yamamoto T., Inoue J-I. (1996) TRAF5, a novel TNF-R-associated factor family protein, mediates CD40 signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 9437–9442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hauer J., Püschner S., Ramakrishnan P., Simon U., Bongers M., Federle C., Engelmann H. (2005) TRAF3 serves as an inhibitor of TRAF2/5-mediated activation of the noncanonical NF-κB pathway by TRAF-binding TNFRs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 2874–2879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hostager B. S., Bishop G. A. (1999) Cutting edge: contrasting roles of TRAF2 and TRAF3 in CD40-mediated B lymphocyte activation. J. Immunol. 162, 6307–6311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haxhinasto S. A., Hostager B. S., Bishop G. A. (2002) Cutting edge: molecular mechanisms of synergy between CD40 and the BCR: role for TRAF2 in receptor interaction. J. Immunol. 169, 1145–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xu L-G., Shu H-B. (2002) TRAF3 is associated with BAFF-R and negatively regulates BAFF-R-mediated NF-κB activation and IL-10 production. J. Immunol. 169, 6883–6889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xie P., Stunz L. L., Larison K. D., Yang B., Bishop G. A. (2007) TRAF3 is a critical regulator of B cell homeostasis in secondary lymphoid organs. Immunity 27, 253–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xie P., Hostager B. S., Bishop G. A. (2004) Requirement for TRAF3 in signaling by LMP1, but not CD40, in B lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 199, 661–671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sinha S. K., Zachariah S., Quiñones H. I., Shindo M., Chaudhary P. M. (2002) Role of TRAF3 and 6 in the activation of the NF-κB and JNK pathways by X-linked ectodermal dysplasia receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 44953–44961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Peters A. L., Plenge R., Graham R., Altshuler D., Moser K., Gaffney P. M., Bishop G. A. (2008) A novel polymorphism of the human CD40 receptor with enhanced function. Blood 112, 1863–1871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Peters A. L., Bishop G. A. (2010) Differential TRAF3 utilization by a variant human CD40 receptor with enhanced signaling. J. Immunol. 185, 6555–6562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Force W. R., Cheung T. C., Ware C. F. (1997) Dominant negative mutants of TRAF3 reveal an important role for the coiled coil domains in cell death signaling by the lymphotoxin-β receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 30835–30840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gardam S., Sierro S., Basten A., Mackay F., Brink R. (2008) TRAF2 and TRAF3 signal adapters act cooperatively to control the maturation and survival signals delivered to B cells by the BAFF receptor. Immunity 28, 391–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zarnegar B. J., Wang Y., Mahoney D. J., Dempsey P. W., Cheung H. H., He J., Shiba T., Yang X., Yeh W-C., Mak T. W., Korneluk R. G., Cheng G. (2008) Noncanonical NF-κB activation requires coordinated assembly of a regulatory complex of the adaptors cIAP1, cIAP2, TRAF2 and TRAF3 and the kinase NIK. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1371–1378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xie P., Kraus Z. J., Stunz L. L., Liu Y., Bishop G. A. (2011) TRAF3 is required for T cell-mediated immunity and TCR/CD28 signaling. J. Immunol. 186, 143–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rickert R. C., Roes J., Rajewsky K. (1997) B lymphocyte-specific, Cre-mediated mutagenesis in mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 1317–1318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Birnberg T., Bar-On L., Sapoznikov A., Caton M. L., Cervantes-Barragán L., Makia D., Krauthgamer R., Brenner O., Ludewig B., Brockschnieder D., Riethmacher D., Rezis B., Jung S. (2008) Lack of conventional DC is compatible with normal developent and T cell homeostasis, but causes myeloid proliferative syndrome. Immunity 29, 986–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Roark J. H., Park S., Jayawardena J., Kavita U., Shannon M., Bendelac A. (1998) CD1.1 expression by mouse antigen-presenting cells and marginal zone B cells. J. Immunol. 160, 3121–3127 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stunz L. L., Lenert P., Peckham D., Yi A-K., Haxhinasto S. A., Chang M., Krieg A. M., Ashman R. F. (2002) Inhibitory oligonucleotides specifically block effects of stimulatory CpG oligonucleotides in B cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 32, 1212–1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Baccam M., Bishop G. A. (1999) Membrane-bound CD154, but not anti-CD40 mAbs, induces NF-κB independent B cell IL-6 production. Eur. J. Immunol. 29, 3855–3866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hostager B. S., Bishop G. A. (2002) Role of TRAF2 in the activation of IgM secretion by CD40 and CD120b. J. Immunol. 168, 3318–3322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xie P., Hostager B. S., Munroe M. E., Moore C. R., Bishop G. A. (2006) Cooperation between TRAFs 1 and 2 in CD40 signaling. J. Immunol. 176, 5388–5400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xu Y., Cheng G., Baltimore D. (1996) Targeted disruption of TRAF3 leads to postnatal lethality and defective T-dependent immune responses. Immunity 5, 407–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Andreakos E., Sacre S. M., Smith C. I., Lundberg A., Kiriakidis S., Stonehouse T., Monaco C., Feldmann M., Foxwell B. M. (2004) Distinct pathways of LPS-induced NF-κB activation and cytokine production in human myeloid cells defined by selective utilization of MyD88 and Mal/TIRAP. Blood 103, 2229–2237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Finkelman F. D., Holmes J., Katona I. M., Urban J. F., Beckmann M. P., Park L. S., Schooley K. A., Coffman R. L., Mosmann T. R., Paul W. E. (1990) Lymphokine control of in vivo Ig isotype selection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 8, 303–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bishop G. A., Haxhinasto S. A., Stunz L. L., Hostager B. S. (2003) Antigen-specific B lymphocyte activation. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 23, 149–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Borst J., Hendricks J., Xiao Y. (2005) CD27 and CD70 in T cell and B cell activation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 17, 275–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Turelli P., Trono D. (2005) Editing at the crossroad of innate and adaptive immunity. Science 307, 1061–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. O'Neill L. A. J. (2006) How TLRs signal: what we know and what we don't know. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 18, 3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chaudhuri J., Alt F. W. (2004) Class-switch recombination: interplay of transcription, DNA deamination, and DNA repair. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 541–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lopes-Carvalho T., Foote J., Kearney J. F. (2005) Marginal zone B cells in lymphocyte activation and regulation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 17, 244–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brummel R., Lenert P. (2005) Activation of MZ B cells from Lupus mice with type A(D) CpG-oligodeoxynucleotides. J. Immunol. 174, 2429–2434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Barr T. A., Brown S., Ryan G., Zhao J., Gray D. (2007) TLR-mediated stimulation of APC: distinct cytokine responses of B cells and dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 37, 3040–3053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tseng P-H., Matsuzawa A., Zhang W., Mino T., Vignali D. A. A., Karin M. (2010) Different modes of ubiquitination of the adaptor TRAF3 selectively activate the expression of type I interferons and proinflammatory cytokines. Nat. Immunol. 11, 70–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mann J., Oakley F., Johnson P. W., Mann D. A. (2002) CD40 induces IL-6 gene transcription in DC: regulation by TRAF2, AP-1, NF-κB and CBF1. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 17125–17138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jalukar S. V., Hostager B. S., Bishop G. A. (2000) Characterization of the roles of TRAF6 in CD40-mediated B lymphocyte effector functions. J. Immunol. 164, 623–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hostager B. S., Haxhinasto S. A., Rowland S. R., Bishop G. A. (2003) TRAF2-deficient B lymphocytes reveal novel roles for TRAF2 in CD40 signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 45382–45390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mukundan L., Bishop G. A., Head K. Z., Zhang L., Wahl L. M., Suttles J. (2005) TRAF6 is an essential mediator of CD40-activated proinflammatory pathways in monocytes and macrophages. J. Immunol. 174, 1081–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Brown K. D., Hostager B. S., Bishop G. A. (2002) Regulation of TRAF2 signaling by self-induced degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 19433–19438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Moore C. R., Bishop G. A. (2005) Differential regulation of CD40-mediated TRAF degradation in B lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 175, 3780–3789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Moore C. (2006) Degradation of TRAFs: characterization and consequences. Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Iowa [Google Scholar]

- 58. Davies C. C., Mak T. W., Young L. S., Eliopoulos A. G. (2005) TRAF6 is required for TRAF2-dependent CD40 signal transduction in nonhemopoietic cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 9806–9819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Munroe M. E., Bishop G. A. (2004) Role of TRAF2 in distinct and overlapping CD40 and TNFR2/CD120b-mediated B lymphocyte activation. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 53222–53231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Andrade R. M., Wessendarp M., Portillo J-A. C., Yang J-Q., Gomez F. J., Durbin J. E., Bishop G. A., Subauste C. S. (2005) TRAF6-dependent CD40 signaling primes macrophages to acquire antimicrobial activity in response to TNF-α. J. Immunol. 175, 6014–6021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Grech A. P., Gardam S., Chan T., Quinn R., Gonzales R., Basten A., Brink R. (2005) TNFR2 signaling is negatively regulated by a novel, carboxyl-terminal TRAF2 binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 31572–31581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sen R. (2006) Control of B lymphocyte apoptosis by the transcription factor NF-κB. Immunity 25, 871–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Liao G., Zhang M., Harhaj E. W., Sun S-C. (2004) Regulation of NIK by TRAF3-induced degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26243–26250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ramakrishnan P., Wang W., Wallach D. (2004) Receptor-specific signaling for both the alternative and canonical NF-κB activation pathways by NIK. Immunity 21, 477–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zarnegar B., Yamazaki S., He J. Q., Cheng G. (2008) Control of canonical NF-κB activation through the NIK-IKK pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 3503–3508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Rowland S. L., Tremblay M. L., Ellison J. M., Stunz L. L., Bishop G. A., Hostager B. S. (2007) A novel mechanism for TRAF6-dependent CD40 signaling. J. Immunol. 179, 4645–4653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ahonen C., Manning E. M., Erickson L. D., O'Connor B. P., Lind E. F., Pullen S. S., Kehry M. R., Noelle R. J. (2002) The CD40-TRAF6 axis controls affinity maturation and the generation of long-lived plasma cells. Nat. Immunol. 3, 451–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Burdin N., Van Kooten C., Galibert L., Abrams J. S., Wijdenes J., Banchereau J., Rousset F. (1995) Endogenous IL-6 and IL-10 contribute to the differentiation of CD40-activated human B lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 154, 2533–2544 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Oka Y., Rolink A. G., Suematsu S., Kishimoto T., Melchers F. (1995) An IL-6 transgene expressed in B lymphocyte lineage cells overcomes the T cell-dependent establishment of normal levels of switched Ig isotypes. Eur. J. Immunol. 25, 1332–1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Pullen S. S., Miller H. G., Everdeen D. S., Dang T. T. A., Crute J. J., Kehry M. R. (1998) CD40-tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) interactions: regulation of CD40 signaling through multiple TRAF binding sites and TRAF hetero-oligomerization. Biochemistry 37, 11836–11845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. He L., Grammer A. C., Wu X., Lipsky P. E. (2004) TRAF3 forms heterotrimers with TRAF2 and modulates its ability to mediate NF-κB activation. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 55855–55865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Brown K. D., Hostager B. S., Bishop G. A. (2001) Differential signaling and TRAF degradation by CD40 and the EBV oncoprotein LMP1. J. Exp. Med. 193, 943–954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Gantner F., Hermann P., Nakashima K., Matsukawa S., Sakai K., Bacon K. B. (2003) CD40-dependent and -independent activation of human tonsil B cells by CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. Eur. J. Immunol. 33, 1576–1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Vanden Bush T. J., Bishop G. A. (2008) TLR7 and CD40 cooperate in IL-6 production via enhanced JNK and AP-1 activation. Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 400–409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]