Abstract

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by mutations in the gene encoding the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). The most common mutation, ΔF508, causes retention of CFTR in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Some CF abnormalities can be explained by altered Ca2+ homeostasis, although it remains unknown how CFTR influences calcium signaling. This study examined the novel hypothesis that store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) through Orai1 is abnormal in CF. The significance of Orai1-mediated SOCE for increased interleukin-8 (IL-8) expression in CF was also investigated. CF and non-CF human airway epithelial cell line and primary cells (obtained at lung transplantation) were used in Ca2+ imaging, electrophysiology, and fluorescence imaging experiments to explore differences in Orai1 function in CF vs. non-CF cells. Protein expression and localization was assessed by Western blots, cell surface biotinylation, ELISA, and image correlation spectroscopy (ICS). We show here that store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) is elevated in CF human airway epithelial cells (hAECs; ∼1.8- and ∼2.5-fold for total Ca2+i increase and Ca2+ influx rate, respectively, and ∼2-fold increase in the ICRAC current) and is caused by increased exocytotic insertion (∼2-fold) of Orai1 channels into the plasma membrane, which is normalized by rescue of ΔF508-CFTR trafficking to the cell surface. Augmented SOCE in CF cells is a major factor leading to increased IL-8 secretion (∼2-fold). CFTR normally down-regulates the Orai1/stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) complex, and loss of this inhibition due to the absence of CFTR at the plasma membrane helps to explain the potentiated inflammatory response in CF cells.—Balghi, H., Robert, R., Rappaz, B., Zhang, X., Wohlhuter-Haddad, A., Evagelidis, A., Luo, Y., Goepp, J., Ferraro, P., Roméo, P., Trebak, M., Wiseman, P. W., Thomas, D. Y., Hanrahan, J. W. Enhanced Ca2+ entry due to Orai1 plasma membrane insertion increases IL-8 secretion by cystic fibrosis airways.

Keywords: calcium influx, calcium channels, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, CFTR, cytokine

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive disease caused by mutations in the cftr gene and characterized by abnormal epithelial ion transport, viscous mucus, chronic bacterial infection, and exaggerated airway inflammation (1). The most common mutation in this ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter is a deletion of phenylalanine at position 508 (ΔF508) in the first nucleotide binding domain. The CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) normally functions as a cAMP-regulated anion channel (2–4); however, its misfolding and retention in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) also affect the transport of other ions, and CFTR mutations have many effects that remain poorly understood but are likely to be crucial during CF pathogenesis (5, 6). The presence of early and excessive inflammation associated with sustained accumulation of neutrophils, high proteolytic activity, and elevated levels of cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-8 are hallmark features of CF lung disease.

Exaggerated intracellular Ca2+ (Ca2+i) signaling on activation of various membrane receptors (e.g., histamine and cytokines) is also characteristic of CF cells (7–9) and is partly due to the expansion of apically confined ER Ca2+ stores during inflammation in vivo (8). However, other intrinsic mechanisms are also involved since Ca2+i signaling is still up-regulated in CF cell lines after many passages in vitro (7, 10). Most studies of Ca2+i in CF have focused on IP3 receptor (IP3R)-mediated Ca2+ release from ER stores (i.e., the site where ΔF508-CFTR is retained); however, derangements in Ca2+i signaling could arise through several mechanisms. Interestingly, Ratner et al. (11) have demonstrated that CF pathogens, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, can promote IL-8 secretion through a Cai2+-dependent mechanism in airway epithelial cells. Ca2+-release from the ER activates sustained Ca2+ influx through channels in the plasma membrane (PM), a phenomenon referred to as store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE). Depletion of Ca2+ from the ER triggers a signaling cascade beginning with activation of the ER-resident Ca2+ sensor protein stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1; refs. 13–15). STIM1 in the ER membrane approaches the PM, where it interacts with, and activates, the Ca2+ release-activated channel (CRAC) Orai1 (16–19) and transient receptor potential-canonical channels (TRPC1, TRPC4, and TRPC5; ref. 20), although the involvement of the latter in SOCE remains controversial (20–22).

The effect of CFTR and the mechanisms that underlie augmented Ca2+ signaling in CF have remained obscure; however, the recent discovery of STIM1 and Orai1 as key players in SOCE prompted us to examine their role in the context of CF physiopathology. Here, we report that ΔF508-CFTR human airway epithelial cells (hAECs) have enhanced SOCE, which is mediated by STIM1 and Orai1. This up-regulation results from the absence of CFTR at the PM and is clearly distinct from the stimulation of TRPC6 channels reported recently (23). Elevated Ca2+ signaling is caused by an increase in the exocytotic insertion of Orai1 into the PM and the formation of more STIM1/Orai1 complexes during store depletion. We also show that the increased SOCE in CF cells enhances IL-8 secretion; therefore, it may contribute to the hyperinflammatory state that characterizes CF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

siRNA transfection

CF bronchial epithelial wild-type (CFBE-WT) and CFBE-ΔF508 cells were transiently transfected with 50 nM siRNA against Orai1 (Mission siRNA; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) using the N-Ter nanoparticle transfection reagent (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Cell culture

The CFBE41o− airway epithelial cell line, originally developed by Gruenert and colleagues by immortalizing CF (ΔF508/ΔF508) bronchial cell primary cultures (24, 25), was used after transduction with WT or ΔF508 CFTR. The transduced CFBE41o− cell lines used in experiments were a generous gift from Dr. J. P. Clancy (University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL, USA) and were cultured on plastic as described previously (26).

Isolation and culture of human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells

Human lung tissues were obtained from non-CF and CF individuals after lung transplantation with informed consent under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Research Ethics Office of McGill University. Isolation, culture, and differentiation of HBE cells were adapted from procedures previously described (27, 28). Briefly, non-CF and CF airway epithelial cells were isolated from bronchial tissue by enzymatic digestion and were cultured in bronchial epithelial growth medium (BEGM; ref. 27) on vitrogen-coated plastic flasks (Advanced BioMatrix, San Diego, CA, USA), then trypsinized, counted, and cryopreserved or transferred directly onto collagen VI-coated culture inserts (0.36 cm2) adapted for imaging (29) and maintained in air-liquid interface (ALI) medium (27) at a density of 8 × 104 cells/insert. Passage 1 (P1) or cryopreserved P1 cells were used. The ALI medium was changed each day for the first 4 d, then the apical medium was removed, and cells were differentiated at the ALI for an additional 7 d before use. For the CF HBE cells, the isolation and growth media were supplemented with specific and adapted antibiotics based on a recent patient antibiogram.

Measurement of [Ca2+]i

Free Ca2+i was measured using a Photon Technology International (PTI; Birmingham, NJ, USA) imaging system coupled to an inverted microscope (IX81; Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA). In brief, cells were rinsed with standard external solution (130 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 10 mM d-glucose, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH) and incubated for 45 min at 37°C in the same solution supplemented with 5 μM of the acetoxy-methyl ester form of the ratiometric indicator Fura-2 (Fura-2AM). Fura-2 was excited at 340 and 380 nm, and emitted fluorescence was measured at 510 nm. Details of the calibration procedure have been published elsewhere (30). Free Ca2+i was calculated as [Ca2+]i = Kd × β × [(R − Rmin)/(Rmax − R)] (ref. 30). Experiments were performed at room temperature (22–25°C). The standard protocol involved applying 10 μM cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) in Ca2+-free solution to deplete the ER stores and activate Ca2+ influx. Once [Ca2+]i reached a constant baseline level, external solution containing 2 mM Ca2+ was added, and the increase in [Ca2+]i was monitored and analyzed for area under the curve (AUC) during the first 5 min, and the initial slope of the [Ca2+]i increase during the first minute following Ca2+addition. AUC was expressed as [Ca2+]I (nM/min), and the rate of increase was calculated by linear regression using GraphPad Prism4 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

Measurement of Ca2+ influx using Mn2+ quenching of Fura-2 fluorescence

Cells were loaded with Fura-2 and excited at 360 nm (the isosbestic point where fluorescence is independent of [Ca2+]i), and emitted fluorescent light was monitored at 510 nm. The influx of Mn2+ through cationic channels was evaluated by measuring the quench of Fura-2 fluorescence after adding 50 μM Mn2+ to the bath solution. The influx rate was estimated from the slope during the first 20 s. ER Ca2+ stores were depleted by exposing cells to 10 μM CPA in Ca2+-free solution to trigger SOCE. To ensure that quenching was minimal under resting conditions, control experiments were performed by adding Mn2+ without store depletion.

RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells using an RNA isolation kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). RT-PCR was performed using 1 μg of total RNA and the following sense and antisense primers: Orai1 5′-AGGTGATGAGGCCTCAACGAG and 5′-GTAGTCGTGGTCAGCGTCC, STIM1 5′-TCACAGTGAGAAGGCGACAG and 5′-GTGGATGTTACGGACTGCCT, TRPC1 5′-ATGTATACAACCAGCTCTATCTTG and 5′-AGTCTTTGGTGAGGGAATGATG, TRPC2 5′-TCTGGACCATGTTCGGTATG and 5′-GCTACCTCGCTTTGCAGTC, TRPC3 5′-CTGCAAATGAGAGCTTTGGC and 5′-AACTTCCATTCTACATCACTGTC, TRPC4 5′-TTGCCTCTGAAAGACATAACATAAG and 5′-CTACTAACACACATTGTTCACTGA, TRPC5 5′-ACTTCTATTATGAAACCAGAGC and 5′-GCATGATCGGCAATAAGCTG, TRPC6 5′-ACAGATAATGCAAAACAGCTG and 5′-ATGATGCTCTGGGCTTTG. The amplicons were separated on a 3% agarose 3:1 HRB gel (Amersco, Solon, OH, USA) and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Western blot

Cells were lysed in 250 μl RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Tris/HCl, 1% w/v deoxycholic acid, 1% w/v Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitors). Gels were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes for Western blot analysis.

Immunolocalization

Cells were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in TBS (20 mM Tris base, 154 mM NaCl, 2 mM EGTA, and 2 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5) and permeabilized in TBS/0.5% Triton X-100 solution for 10 min. After incubation with primary antibodies [rabbit anti-Orai1 (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA); anti-TRPC1 and anti-TRPC4 (Sigma); mouse anti-STIM1 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA); and anti-CFTR (clone 24-1; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA)] in TBS/1% BSA for 1 h and washing in TBS, the cells were incubated with biotinylated antibodies (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) and with Texas-red streptavidin-conjugated antibody (1:200; Vector Laboratories). Samples were then mounted in Vectashield medium containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories) to label nuclei and viewed with a confocal laser scanning microscope (Confocor LSM 510 META, Carl Zeiss, New York, NY, USA).

Electron microscopy

Cells were fixed in a 2.5% glutaraldehyde/0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) for 1 h at 4°C, then postfixed in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer containing 1% osmium tetroxide, and 1.5% potassium ferrocyanide for 1 h at 4°C. Cells were then dehydrated through a series of ethanol baths and embedded in Epon at 60°C for 48 h. Thick sections (0.5 μm) were cut, stained with 1% toluidine blue for several seconds, and observed using a light microscope. Thin sections of selected regions were cut from each block using a diamond knife, placed on copper 1-slot grids, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined using a Philips EM 410 electron microscope (Philips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

Total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells were transiently cotransfected with 1 μg DNA encoding GAP-GFP (membrane, green) and DsRed-KDEL (ER, red; see Fig. 4), or STIM1-GFP (green) and ORAI1-mCherry (red) using FuGene 6 transfection reagent (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were bathed in the same extracellular solution used during Ca2+ influx experiments, and the same procedure to deplete the stores was applied (i.e., CPA). Illumination at 488 and 543 nm was supplied by a 200-mW argon-ion laser and a helium neon green laser, respectively, coupled to an inverted microscope (IX81; Olympus) equipped with a ×60/1.4-NA oil-immersion lens. Images were acquired using two EM-CCD cameras (Olympus) for rapid simultaneous GFP/mCherry and GFP/DsRed imaging. Images were captured using 250- to 500-ms exposures and 1- × 1-pixel binning under the control of MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Eugene, OR, USA).

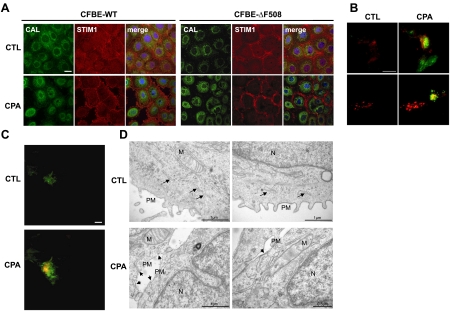

Figure 4.

ΔF508-CFTR does not influence the translocation of STIM1 and the ER toward the PM after Ca2+ store depletion. A) Confocal images of CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells showing STIM1 (red), the ER-resident protein calreticulin (green), and the nucleus (DAPI, blue). Top panels: control conditions (CTL). Bottom panels: after treatment with 10 μM CPA. B) TIRF microscopy of HEK-ΔF508 (top panels) and -WT cells (bottom panels) expressing STIM1-GFP and Orai1-mCherry (kindly provided by Richard Lewis, Stanford University School of Medicine) under control conditions (left images) and after store depletion with 10μM CPA (CPA; right images). Only the red labeling of Orai1 was detected under control conditions; however, green STIM1 was recruited to the PM after CPA treatment. Yellow indicates regions that contain both GFP and mCherry signals, suggesting colocalization of STIM1 and Orai1. C) HEK-ΔF508 cells were transfected with Ds-Red-KDEL (ER marker) and GAP-GFP (PM marker) and imaged using TIRF microscopy. Top panel: only the green PM was detected under control conditions (CTL); ER (red) was not observed. Bottom panel: after store depletion (10 min CPA), the ER appeared and became colocalized with GAP-GFP, indicating movement of the ER close to the cell surface. D) Representative electron microscopy images before (top panels) and after CPA treatment (bottom panels) in CFBE-ΔF508 cells. Nuclei (N), mitochondria (M), and ER (black arrows) are shown. After CPA treatment, the ER was clearly juxtaposed with the membrane. Scale bars = 20 μm (A–C) or as indicated (D).

Membrane potential studies.

Calibration of DiBAC4(3)

The membrane potential of each cell was evaluated using the lipophilic potential-sensitive dye, bis-(1,3-dibutylbarbituric acid)trimethine oxonol [DiBAC4(3)] and methods similar to those described by Epps et al. (31). To calibrate the fluorescence signal, cells were loaded with 500 nM DiBAC4(3) for 15 min at 37°C, then continuously superfused throughout the experiment with Na+-free calibrating solution containing 200 nM DiBAC4(3), with N-methylglucamine to maintain osmolarity and 1 μM of the Na+ ionophore gramicidin to eliminate the Na+ gradient. Under these conditions, the membrane potential is defined by the K+ equilibrium potential according to the Nernst equation (31). DiBAC4(3) fluorescence was measured as extracellular [K+] concentration was stepped from 2.5 to 80 mM while maintaining the product of [K+] × [Cl−] constant to minimize cell swelling. Potentials between −98 and −14mV were calculated using the Nernst equation by assuming that intracellular ion concentrations were 130 mM for K+ and 10 mM for Na+. A positive linear regression was obtained for each cell, with regression coefficients >0.99 (See Supplemental Fig. S4).

Measurement of membrane potential

To measure the membrane potential during Ca2+ influx, the protocol described above for inducing SOCE was applied in cells loaded with the DiBAC4(3). Two-point calibrations were performed at the end of each experiment for every cell studied using 2.5 and 30 mM [K+]e, which should generate membrane potentials ranging between −98 and −38 mV.

Measurement of Mn2+ quenching rate as a function of membrane potential

Solutions containing 2.5, 5, 30, and 120 K were used to clamp the membrane potential of CFBE cells at −98, −82, −38, and −3.8mV, and the rate of Fura-2 fluorescence quenching was measured after addition of 50 μM Mn2+.

Electrophysiology

Conventional whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were carried out using an Axopatch 200B and Digidata 1440A (Axon Instruments, New York, NY, USA) as previously published (32, 33). Clampfit 10.1 software (Molecular Devices) was used for data analysis. Pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (World Precision Instruments, Inc., Sarasota, FL, USA) with a P-97 flaming/brown micropipette puller (Sutter Instrument Company, Novatao, CA, USA) and polished with DMF1000 (World Precision Instruments). Resistances of filled pipettes were 2–3 MΩ. Series resistances were in the range of 2–10 MΩ. The liquid-junction potential offset due to different internal and external saline composition was −4.5 mV and was corrected. Immediately before the experiments, cells were washed with bath solution containing 135 mM Na-methanesulfonate (Sigma), 10 mM CsCl, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 10 mM HEPES, 20 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM glucose (pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). Pipette solution contained 145 mM Cs-methanesulfonate (Sigma), 20 mM Cs-1,2-bis-(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (Cs-BAPTA; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 8 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM HEPES (pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH). Divalent-free (DVF) bath solution contained 155 mM Na-methanesulfonate, 10 mM HEDTA, 1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4, adjusted with NaOH). GdCl3 was from Acros Organics (Morris Plains, NJ, USA). Only cells with tight seals (>3 GΩ) were selected to break in. Immediately after establishing the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration, we start the recording by running the voltage ramp stimulation and performing a first DVF pulse before ICRAC development. These first I/V curves in the absence (curve 1) and presence (curve 2) of DVF solution represent leak currents for Ca2+ ICRAC (curve 3) and Na+ ICRAC currents (curve 4), respectively. After ICRAC currents are fully activated by store depletion, I/V curves are obtained with and without DVF solution conditions. Using Origin Lab 7.5 software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA), I/V curves corresponding to leak currents in Ca2+ and Na+ are subtracted from the I/V curves obtained for Ca2+ ICRAC (curve 3 − curve 1) and Na+ ICRAC (curve 4 − curve 2), respectively, after full current development with store depletion. The subtracted I/V curves are represented as independent I/V curves in figures. Cells were maintained at a 0 mV holding potential during experiments and subjected to voltage ramps from +100 to −140 mV lasting 250 ms every 2 s. Reverse ramps were designed to inhibit Na+ channels potentially expressed in these cells. High MgCl2 (8 mM) was included in the patch pipette to inhibit TRPM7 currents.

Cell surface biotinylation

Cells were exposed to sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin for 5 min at room temperature, rinsed 3 times with Tris buffer (25 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.3), and solubilized in RIPA buffer for 20 min on ice. The resulting lysate was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4°C, and total cellular protein content was determined using the BCA protein assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). The supernatant was incubated with streptavidin beads for 1 h at 4°C (10 μg protein/μl beads preequilibrated with RIPA buffer). Beads were washed 3 times with RIPA buffer, then a 2× sample buffer (4% w/v SDS, 20 mM DTT, 20% w/v glycerol, 125 mM Tris/HCl, and 0.2% bromphenol blue, pH 6.8) was added to the beads at 1:1 ratio to elute adsorbed proteins. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for Western blotting, and scanning densitometry was used for semiquantitative analysis of the blots. Variations in loading were corrected by normalizing results to the Na+/K+ pump α subunit.

Image cross-correlation spectroscopy (ICCS)

CFBE cells were cotransfected transiently with 1 μg DNA encoding STIM1-GFP and Orai1-mCherry using the Normal Human Bronchial Epithelial (NHBE) nucleofection kit from Amaxa (Lonza, Allendale, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Images were collected using an Olympus IX71 FV300 laser scanning microscope with a ×60/1.4-NA oil-immersion lens exciting with a 488-nm laser line for GFP and a 543-nm laser line for mCherry. Emission was collected with a 570-nm dichroic mirror (DM) and 510-nm long-pass filter for GFP and with a 590- to 620-nm bandpass filter for mCherry (a first 488/543/633 DM cuts out the laser lines). Dual channel acquisition was made sequentially to minimize crosstalk (<0.4% in both channels).

The ICCS technique, which measures colocalization of two fluorescently tagged proteins, is described in detail elsewhere (34, 35). Briefly, the fraction of colocalized fluorescent units is measured by a ratio of the amplitudes of the spatial cross-correlation and autocorrelation functions calculated for regions of interest (ROI) in 2 detection channel confocal images, k and l (shorter and longer wavelength channels, respectively). The number of particles per beam area is determined by Eq.1:

| (1) |

where r(0,0)is the 0-lag best-fit amplitude of the spatial autocorrelation (ll and kk) or cross-correlation (kl) function, and A is the effective area of the focal spot for each laser. The ICCS interaction fraction is then defined by the ratio of the number of interacting particles to that of the total number of fluorescently labeled particles in each detection channel:

| (2) |

Analysis was performed on a large ROI inside the cells. This spatial ICCS provides information about the colocalization of large structures (clusters). Measured colocalization values higher than 100% were attributed to noise and were changed to 100% during data analysis. About 50 regions in 10–20 cells were analyzed per condition.

Particle numbers within overlapping clusters of Orai1 and STIM1 (see Fig. 7F) were measured using image correlation spectroscopy (ICS; ref. 35). Intensity thresholding was applied to select only the clusters, and then 〈N〉 = 1/rxx(0,0) was calculated, where rxx(0,0) is the spatial autocorrelation 0-lag amplitude obtained by best fit for each channel (xx = ll or kk).

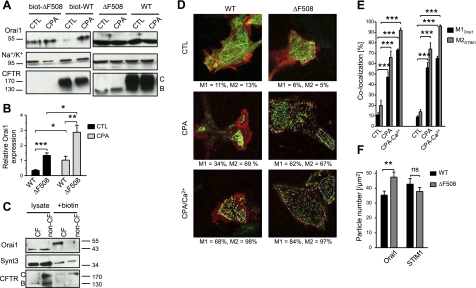

Figure 7.

Increased expression of endogenous Orai1 at the cell surface in CFBE-ΔF508 and human primary CF cells. A) Cell surface biotinylation of Orai1, Na+/K+ pump, and CFTR proteins in CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells. Left panels: representative Western blots of streptavidin pulldowns showing that more Orai1 was biotinylated under control conditions in CFBE-ΔF508 (lane 1) than in -WT cells (lane 3), and that more Orai1 was biotinylated during SOCE (CPA). Right panels: total protein expression in lysates. Note that band B CFTR corresponding to the immature ER form was not detectable at the cell surface, thus providing a control for biotinylation of cell surface proteins. B) Semiquantitative analysis of Orai1 expression at the surface of CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells under control conditions (light gray bars) and during SOCE (CPA; gray bars), normalized to biotinylated α subunit of the Na+/K+ pump. Data are means ± se of 5 experiments. C) Apical cell surface biotinylation of Orai1, Syntaxin 3 and CFTR proteins in polarized human primary CF and non-CF cells. Left panels: total protein expression in lysates. Right panels: representative Western blots of streptavidin pulldowns showing that more Orai1 was biotinylated at the apical surface under control conditions in CF monolayers (lane 3) than in non-CF (lane 4). D–F) Orai1-mCherry and STIM1-GFP colocalization and particle number measured by image correlation and cross-correlation spectroscopy (ICS and ICCS) under control (CTL) conditions, after CPA application (CPA) and during SOCE (CPA + Ca2+) in CFBE-WT vs. -ΔF508 cells. D) Representative confocal images of each condition with the region analyzed indicated by a white polygon. M1 is the percentage of Orai1 colocalized with STIM1 and M2 the percentage of STIM1 colocalized with Orai1 (See Materials and Methods). E) Histogram of Orai1 and STIM1 cluster colocalization in CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells. F) Histogram of particle densities measured inside Orai1/STIM1 clusters during the calcium entry into CFBE-WT (black bars) vs. -ΔF508 cells (gray bars). Data are means ± se of 52 CFBE-WT and 41 CFBE-ΔF508 cells.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of IL-8 secretion

Samples were collected from the apical side of cells grown on filters, which were stimulated for 4 h with CPA or Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) with or without inhibitors. Samples were run in duplicate as indicated in the manufacturer's protocol (Human CXCL8/IL-8 ELISA kit; R&D Systems), and read at 450 nm with an ELX808 Ultra Microplate Reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). Each duplicate was repeated ≥3 times; averages of the 3 experiments are reported.

Statistics

Results are expressed as the means ± se of n observations. Data sets were compared using the Student's t test or by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with GraphPad Prism 4 or with Origin software (OriginLab) for electrophysiology experiments. Differences between the colocalization obtained in control, CPA-, and CPA + Ca2+-stimulated cells were assessed using the nonparametrical Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. Differences were considered statistically significant at values of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

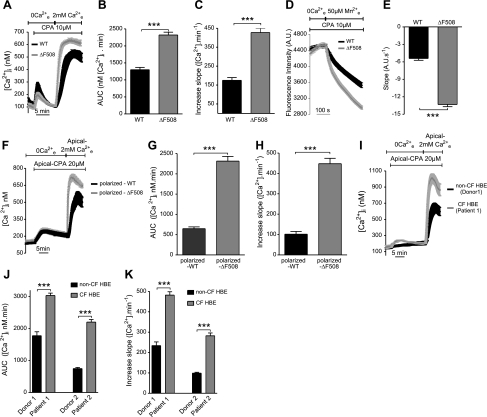

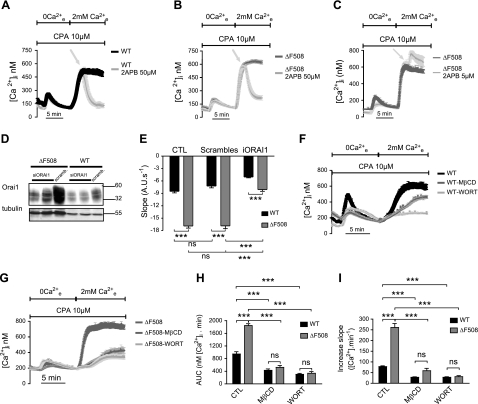

Ca2+ entry after store depletion is enhanced in hAECs expressing ΔF508-CFTR

Ca2+ signals are reportedly larger in CF cells than in non-CF cells (7, 8). We began by establishing this in a CFBE cell line (CFBE41o−) that stably expresses heterologous WT- or ΔF508-CFTR. To induce Ca2+ store depletion, cells were exposed to the SERCA-pump inhibitor CPA (10 μM) in Ca2+-free solution containing EGTA. CPA caused a similar elevation of Ca2+i in CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells, suggesting that total Ca2+ content of the ER stores was similar in both cell lines (Fig. 1A). By contrast, a much larger Ca2+i increase was observed in ΔF508 than in WT cells when Ca2+ was added back to the extracellular medium after store depletion (Fig. 1A). The area under the curve (AUC) and Ca2+ influx rate were both increased significantly in ΔF508 cells compared to WT cells (∼1.8- and 2.5-fold, respectively), indicating a larger and faster Ca2+ influx into CFBE-ΔF508 cells (Fig. 1B, C). Since the fluorescence signal depends not only on the rate of Ca2+ entry but also on extrusion and intracellular buffering, we assessed influx after Ca2+ store depletion more directly by measuring Mn2+-induced quenching of Fura-2 fluorescence at the isosbestic point when Mn2+ and Ca2+ were both added to the extracellular medium. The rate of fluorescence quenching by Mn2+ was greatly increased (∼2.5-fold) in ΔF508 cells compared to WT cells (Fig. 1D, E). Exposure to ATP, a physiological Ca2+ agonist that depletes the ER stores, also activated a larger and faster Ca2+ influx in CFBE-ΔF508 cells compared to WT cells, confirming the results obtained using CPA (See Supplemental Fig. S1A, B). Similar responses were obtained after CPA-mediated store depletion using HEK cell lines that stably express ΔF508- vs. WT-CFTR (Supplemental Fig. S1C, D). Polarized hAECs have functionally distinct apical and basolateral membranes. To determine whether abnormal Ca2+ signaling depends on cell polarization, we also examined monolayers that had been cultured at the ALI and mounted in a double-perfusion chamber (29). Enhanced Ca2+ entry was observed in polarized CFBE-ΔF508 cells after store depletion when extracellular Ca2+ was present only on the apical side, indicating that most Ca2+ entered through the apical membrane (Fig. 1F–H). Highly polarized CF primary HBE cells from two patients that had been cultured at the ALI for >1 mo exhibited significantly larger apical Ca2+ influxes when compared with HBE cells from two non-CF donors (Fig. 1I–K). These results indicate that cells expressing ΔF508-CFTR have enhanced Ca2+ influx following depletion of their Ca2+ stores.

Figure 1.

SOCE is enhanced in CF hAECs. [Ca2+]i was measured using the Ca2+ probe Fura-2. A) Time course of [Ca2+]i when cells were exposed to CPA (10 μM) in Ca2+-free saline to deplete intracellular stores and Ca2+ was added back to the extracellular medium. Calcium readdition produced a much larger Ca2+i increase in CFBE-ΔF508 cells (gray trace, n=78 cells) compared to -WT cells (black trace, n=71 cells). B, C) AUC calculated during the first 5 min after readding Ca2+e to CFBE-WT (black bar) and -ΔF508 (gray bar) cells with depleted stores (B), and slope calculated during the first minute of Ca2+ entry in CFBE-WT (black bar) and -ΔF508 (gray bar) cells (C). Data are means ± se of 86 WT and 113 ΔF508 cells. D) Representative experiment showing the time course of Mn2+ quenching after depleting stores in CFBE-WT (black trace) and -ΔF508 (gray trace) cells. E) Rate of net influx into CFBE-WT (black) and -ΔF508 (gray) cells after store depletion. Data are means ± se of 41 WT and 52 ΔF508 cells. F) SOCE is enhanced in polarized monolayers of cells expressing ΔF508- (gray trace) compared to WT-CFTR (black trace). After ER store depletion by CPA application, a larger Ca2+i increase was observed in polarized CFBE-ΔF508 (gray trace) compared to -WT monolayers (black trace) when extracellular Ca2+ was present only on the apical side. G, H) AUC (G) and slope (H) in polarized CFBE-WT (black bar) and -ΔF508 (gray bar) monolayers. Data are means ± se of 25 WT and 10 ΔF508 cells. I) SOCE is also augmented in polarized CF-HBE (gray trace) compared to non-CF cells (black trace). J, K) AUC (J) and slope (K) in polarized non-CF (black bar) and CF-HBE (gray bar) monolayers. Data are means ± se of 6, 7, 3, and 3 culture inserts from donor 1, patient 1, donor 2, and patient 2, respectively.

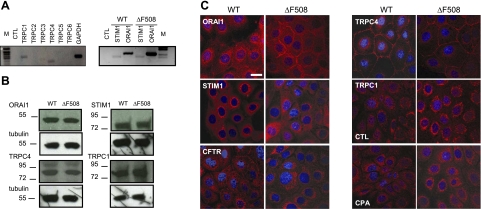

Expression of proteins that mediate SOCE

Although TRPC channels have long been implicated in capacitative Ca2+ influx (21, 22), we also examined Orai1 and STIM1, which have been identified recently as mediators of SOCE in many cell types. Orai1, STIM1, TRPC4, and TRPC1 mRNA and protein were highly expressed in CFBE cells, and no differences were observed between CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells (Fig. 2A, B) or between HEK-WT and -ΔF508 cells (Supplemental Fig. S1E). The intracellular localization was determined for each of these proteins in CFBE cells by immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy (Fig. 2C). Orai1 was distributed diffusely in CFBE cells, although labeling of the PM was more pronounced in ΔF508- cells than in WT-CFTR cells (Fig. 2C, top left). Most STIM1 staining was perinuclear in both cell types, as expected (Fig. 2C). TRPC4 was localized to the PM, whereas TRPC1 staining was diffuse and intracellular in both cell types (Fig. 2C). Translocation of TRPC1 to the cell surface was not detected following Ca2+ store depletion, suggesting that it mediates little, if any, Ca2+ influx after store depletion (Fig. 2C, bottom right) in contrast with other cell types (36). As expected, WT-CFTR was expressed at the PM, whereas ΔF508-CFTR staining was mostly perinuclear (Fig. 2C, bottom left).

Figure 2.

Expression and localization of endogenous Ca2+ signaling proteins in CFBE cells. A) Left panel: agarose gel showing that TRPC1 and TRPC4 were detected in CFBE cells by RT-PCR, but not other TRPC family members (TRPC2, 3, 5, and 6). Right panel: STIM1 and ORAI1 mRNAs were also expressed in both CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells. B) Endogenous Orai1, STIM1, TRPC4, and TRPC1 proteins are expressed at similar levels in CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells. C) Immunolocalization of Orai1, STIM1, CFTR, TRPC4, and TRPC1 in CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells. All these proteins were stained with Texas-Red, and nuclei were stained blue with DAPI. Scale bar = 20 μm. Note PM staining of Orai1, TRPC4, and WT-CFTR, and the perinuclear localization of TRPC1, STIM1, and ΔF508-CFTR.

Orai1 is a store-operated Ca2+channel that mediates Ca2+ entry in hAECs

2-APB inhibits capacitative Ca2+ channels at high concentration and activates them at low concentration (37). When 50 μM 2-APB was added at the Ca2+i peak, Ca2+i fell rapidly to basal levels in CFBE and HEK cells (Fig. 3A, B and Supplemental Fig. S1F), while at 5 μM, 2-APB induced a second peak of Ca2+i increase (Fig. 3C). To confirm the involvement of Orai1 in SOCE, CFBE cells were transfected with siRNA targeting Orai1 transcripts, and the rate of fluorescence quenching by Mn2+ was assessed. The Western blot in Fig. 3D shows moderately efficient knockdown of Orai1 in CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells. Suppressing Orai1 expression by 60% reduced the SOCE in CFBE-ΔF508 cells by 47%, and a ∼50% reduction in CFBE-WT cells reduced SOCE by 30% (Fig. 3E). These results demonstrate the predominant role of Orai1 in SOCE in CFBE cells.

Figure 3.

Orai1 and its signaling complex mediate SOCE. A–C) 2-APB used at high concentration (50 μM) abolishes SOCE in CFBE-WT (A) and -ΔF508 (B), while at low concentration (5 μM), 2-APB activates SOCE (C). Traces are means ± se of 23 and 31 CFBE-WT cells and 22 and 48 CFBE-ΔF508 cells in control and 50 μM 2-APB treatment groups, respectively, and 9 and 6 CFBE-ΔF508 cells in control and 5 μM 2-APB treatment groups, respectively. D) Representative blot showing the effect of siRNA on Orai1 expression in CFBE-WT (10 μg) and -ΔF508 (20 μg) cells. Tubulin was used as an internal control. E) Silencing Orai1 expression reduces the rate of Mn2+ quenching in CFBE-WT (black bars) and -ΔF508 cells (gray bars). Data are means ± se of 21, 23, and 37 CFBE-WT cells and 23, 27, and 43 CFBE-ΔF508 cells under control, scrambled, and Orai1 siRNA-treated conditions, respectively. F, G) Time course of Ca2+ influx in CFBE-WT (black; F) and -ΔF508 (dark gray; G) cells, respectively, under control conditions and after pretreatment with MβCD (2 mM, gray) or wortmannin (10 μM, light gray). Traces are means ± se of 9, 5, and 18 CFBE-WT cells and 11, 14, and 11 cells CFBE-ΔF508 cells in control, MβCD, and wortmannin treatments, respectively. H, I) AUC (H) and the increase in slope (I), as measured for CFBE-WT (black) and -ΔF508 (gray) cells under control conditions and when treated with MβCD or wortmannin. Data are means ± se of 51, 46, and 50 CFBE-WT cells and 45, 49, and 25 CFBE-ΔF508 cells in control, MβCD, and wortmannin treatments, respectively.

The possible role of cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains in modulating Ca2+ influx and formation of a macromolecular signaling complex were investigated using the cholesterol depletion reagent methyl-β-cyclodextrin. Pretreatment with methyl-β-cyclodextrin markedly reduced SOCE in both CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells (Fig. 3F, G). Moreover, cholesterol depletion abolished the difference in total Ca2+i influx between CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells, as determined from the AUC (Fig. 3H). The rate of Ca2+ influx was also slowed significantly after cholesterol depletion (by 64 and 78% in CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells, respectively; Fig. 3I). Phosphoinositides are known to regulate SOCE (38), therefore we tested the effect of wortmannin, which inhibits phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase at micromolar concentrations and causes PIP2 depletion. Micromolar wortmannin drastically inhibited the Ca2+i response during SOCE and delayed Ca2+ influx into CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells (Fig. 3F–I). These effects of cholesterol and PIP2 depletion suggest that SOCE involves the formation of a STIM1-Orai1 signaling complex at the PM that is situated in cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains and regulated by phosphoinositides.

STIM1 and ER movements to the PM are not disrupted by expression of ΔF508-CFTR

Following Ca2+ store depletion, the Ca2+ sensor STIM1 migrates to ER-PM junctions, where it interacts with Orai1. This migration was assessed in CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells by immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy of the ER resident marker protein calreticulin (green) and STIM1 (red; Fig. 4A). Under control conditions (CTL), STIM1 was observed throughout the cytosol and was also colocalized with calreticulin in the perinuclear region in both cell types (Fig. 4A, top panels). After CPA treatment, STIM1 no longer colocalized with calreticulin (Fig. 4A, bottom panels) and became localized beneath the PM in CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells, evidence that STIM1 migration toward the membrane is not altered by ΔF508-CFTR when compared to CFBE-WT. To test whether the interaction of STIM1 with Orai1 is affected by ΔF508- or WT-CFTR after migration to the PM, the fluorescent constructs STIM1-GFP and Orai1-mCherry were cotransfected into HEK-WT and -ΔF508 cells and examined using TIRF microscopy (Fig. 4B). Under control conditions, Orai1-mCherry was detected at the membrane and STIM1-GFP was entirely intracellular in HEK-ΔF508 (Fig. 4B, top left panel) and -WT cells (Fig. 4B, bottom left panel), whereas after stores were depleted using CPA, the STIM1-GFP became colocalized with Orai1-mCherry in the TIRF field in HEK-ΔF508 (Fig. 4B, top right panel) and -WT cells (Fig. 4B, bottom right panel). This indicates that store depletion causes STIM1-GFP migration to the membrane and its interaction with Orai1-mCherry (15) irrespective of the presence of WT or mutant CFTR. To further investigate whether ER retention of ΔF508-CFTR interferes with its migration toward the PM, HEK-ΔF508 cells were cotransfected with KDEL-DsRed and GAP-GFP to label the ER and the PM, respectively. Only the PM (green) could be seen by TIRF microscopy under control conditions (Fig. 4C). However, after Ca2+ store depletion, the ER (red) also became visible by TIRF imaging and colocalized with GAP-GFP (as indicated by yellow region), indicating that the ER had moved in close proximity to the PM (Fig. 4C). Electron microscopy performed on CFBE-ΔF508 cells further confirmed that the ER had approached the PM after store depletion (Fig. 4D, see arrows in the middle and right images). Taken together, these results show that ΔF508-CFTR retention in the ER does not alter the migration of STIM1 and the ER to the PM following depletion of the Ca2+ stores.

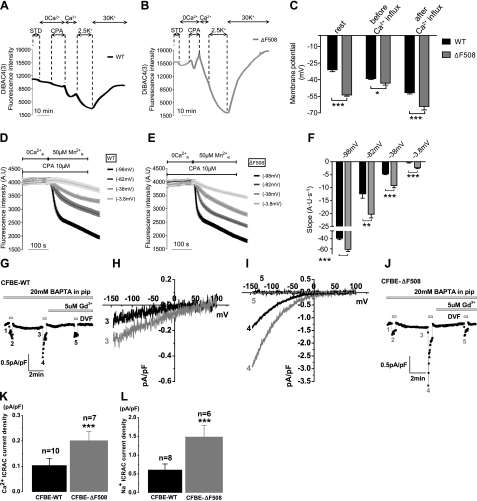

CFTR modulation of Orai1-mediated SOCE is not effected through changes in membrane potential

Ca2+ entry through open Orai1 channels depends on the net electrochemical gradient for Ca2+ at the cell membrane. The Ca2+ current carried by Orai1 is inwardly rectified (19); i.e., larger at hyperpolarized potentials, and it has been suggested that the membrane potential is hyperpolarized in CF cells (39). To examine whether a decrease in membrane potential could explain the larger SOCE in ΔF508-CFTR cells, we first measured the membrane potential during SOCE in CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells using the fluorescent dye DiBAC4(3) (Fig. 5A–C). Under control conditions, the membrane potential of CFBE-ΔF508 (−53.8±1.1 mV) was indeed hyperpolarized compared to CFBE-WT cells (−31.1±1.7 mV; Fig. 5C); however, this difference was nearly abolished by store depletion, so that the average membrane potentials in CFBE-ΔF508 cells (−43.1±1.8 mV) and CFBE-WT cells (−39.0±0.8 mV) were similar (Fig. 5C). Restoring extracellular Ca2+ hyperpolarized both CFBE-WT (−51.8 mV±1.1 mV) and -ΔF508 (−64.2 mV±3.2 mV) cells, presumably due to opening of Ca2+ activated K+ channels. To examine whether increased SOCE in CFBE-ΔF508 cells could be ascribed to this hyperpolarization, the rate of Mn2+ quenching was measured immediately after store depletion while clamping the membrane at different (measured) potentials by varying extracellular potassium concentration (see Materials and Methods). As expected, Mn2+ quenching was most rapid when CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells were hyperpolarized (−98 mV; Fig. 5D–F). Notably, although Orai1 was maximally activated under these conditions, the maximal rate was still significantly higher at −98 mV in CFBE-ΔF508 cells than in -WT cells (e.g., −61.2 vs. −39.0 AU/s, respectively; Fig. 5F). The same pattern (i.e., faster quenching in CFBE-ΔF508 cells) was observed at all membrane potentials tested (−82, −38 and −3.8 mV). Interestingly, the largest difference between CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 quenching rates (∼2-fold) was observed at −38 mV; i.e., approximately the resting membrane potential (Fig. 5F). To further confirm that the membrane potential is not involved in the augmented SOCE in CFBE-ΔF508 cells and to rule out an additional activation of Ca2+ activated Cl− current during store depletion, we performed whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiological recordings in CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells. To characterize the current that mediates SOCE, we used the standard method for measuring ICRAC in whole-cell configuration in which the intracellular compartment is dialyzed with a high concentration of the fast Ca2+ chelator BAPTA to induce passive store depletion, as described previously (32, 33). On breaking into the cell with pipette solution containing 20 mM BAPTA, a relatively small inwardly rectifying ICRAC-like current developed in the presence of external Ca2+ (20 mM) in CFBE cells (Fig. 5G, J and Supplemental Fig. S2). Notably, this current was significantly larger in CFBE-ΔF508 cells than in -WT cells (0.20±0.03 vs. 0.10±0.03pA/pF, respectively; Fig. 5H, K and Supplemental Fig. S2). To amplify and better characterize the ICRAC currents in CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells, we also measured currents using DVF bath conditions, as described previously (40). As shown in Fig. 5I, L, the monovalent ICRAC current measured in CFBE-ΔF508 cells was significantly larger than in -WT cells (1.5±0.3 vs. 0.6±0.2 pA/pF). The use of 5 μM Gd3+, a known inhibitor of Orai1 channels, completely abrogated these currents (Fig. 5I and Supplemental Fig. S2), thus providing evidence that Orai1 was the CRAC channel that is up-regulated in CFBE-ΔF508 cells. Collectively, these data show that although Ca2+ influx through Orai1 is increased by hyperpolarization, the enhanced SOCE observed in CFBE-ΔF508 cells cannot be explained by this change in driving force or by activation of other conductances.

Figure 5.

Increased Orai1-mediated current in CFBE-ΔF508 cells is not through changes in the membrane potential. A, B) Time courses of the MP during the SOCE in CFBE-WT (A) and -ΔF508 cells (B). Traces are means ± se of 21 and 15 cells in CFBE-WT and -ΔF508, respectively. C) Summary of the MP at rest, after CPA-induced store depletion (before the influx was triggered) and after the addition of Ca2+ back to the extracellular medium. Results are from 57 and 54 CFBE-WT (black bars) and -ΔF508 cells (gray bars), respectively. Store depletion nearly abolished differences in the MP between CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells under CTL conditions. D, E) Representative traces showing Mn2+ quenching rate when the membrane potential was measured and clamped at −98, −82, −38, and −3.8 mV during SOCE by elevating extracellular potassium in CFBE-WT (D) and −ΔF508 cells (E). F) Summary of the quench rates estimated during the first 20 s after Mn2+ addition in CFBE-WT (black bars) and -ΔF508 cells (gray bars). Note that Mn2+ entry into CFBE-ΔF508 cells was significantly faster at all membrane potentials studied. Data are means ± se of ∼30 cells for all conditions. G–L) CFBE-ΔF508 cells show larger CRAC current (ICRAC) compared to CFBE-WT cells. G, J) CFBE-WT (G) and -ΔF508 cells (J) were dialyzed with a pipette solution containing 20 mM BAPTA to induce store depletion, and whole-cell currents were measured in the presence of 20 mM Ca2+e and after applying pulses of DVF bath solutions to amplify CRAC currents. Currents recorded in DVF solutions show the typical depotentiation reminiscent of Na+ CRAC currents. Low concentrations of lanthanides (5 μM Gd3+) shown to inhibit Orai1-mediated CRAC currents were used at the end of the recordings. Data points from each ramp were taken at −100 mV and plotted. Small inwardly rectifying ICRAC currents developed in both cell types and were greatly amplified under DVF conditions. H) The I/V relationships show larger Ca2+ ICRAC in CFBE-ΔF508 cells than in -WT cells. I). Similarly, the I/V relationships measured in DVF solutions show larger Na+ ICRAC in CFBE-ΔF508 than in -WT cells, which are completely blocked by 5 μM Gd3+. In all sweeps represented in panels H and I, leak currents were subtracted. K, L) Data summary of Ca2+ ICRAC density in CFBE-WT (n=10) and -ΔF508 (n=7) cells (K) and of monovalent ICRAC density in CFBE-WT (n=8) and -ΔF508 (n=6) cells (L).

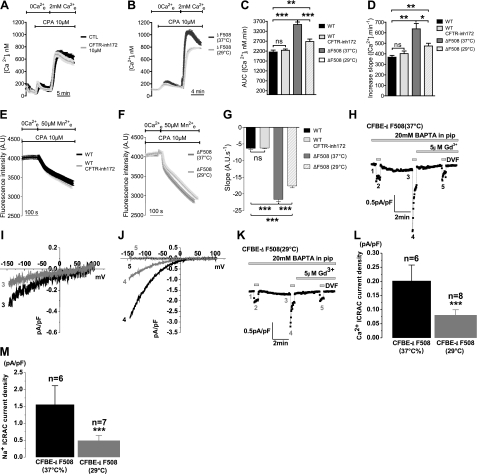

The presence of CFTR in the PM, not its channel function, modulates SOCE

To understand how SOCE activity is increased in ΔF508-CFTR cells, we asked whether CFTR channel activity is required to modulate Ca2+ entry, or whether the expression of WT CFTR protein at the cell surface is sufficient to down-regulate the STIM1-Orai1 complex. Channel function was inhibited in CFBE-WT cells by adding CFTRinh172 at the same time that extracellular Ca2+ was reintroduced. CFTRinh172 did not affect SOCE (Fig. 6A), as assessed by total Ca2+ entry (AUC; Fig. 6C) or rate of entry (slope; Fig. 6D). To further test whether the presence of CFTR protein in the PM influences SOCE activity, SOCE was compared when CFBE-ΔF508 cells were kept at 37°C or incubated for 24 h at low temperature (29°C) to restore ΔF508-CFTR trafficking to the PM, as represented by the appearance of mature band C CFTR in Western blots (Supplemental Fig. S3). Rescuing ΔF508-CFTR reduced the AUC (24%) and slope (29%) to values that were comparable to those in CFBE-WT cells (Fig. 6B–D). Mn2+ quenching was also reduced after low-temperature rescue to rates similar to those in CFBE-WT cells, despite the presence of CFTRinh172 (Fig. 6E–G). Moreover, incubating CFBE-ΔF508 cells at 29°C significantly decreased the amplitude of the ICRAC measured in patch-clamp experiments (0.20±0.06 vs. 0.08±0.02 pA/pF; Fig. 6H–M). The I/V relationships measured in DVF solutions showed a significant decrease in ICRAC currents carried by Na+ when CFBE-ΔF508 cells were incubated at 29°C (1.6±0.6 vs. 0.5±0.2 pA/pF; Fig. 6J, M). Moreover, the current density measured in CFBE-ΔF508 after incubation at 29°C (Fig. 6L, M) was similar to that measured in CFBE-WT (Fig. 5K, L; for comparison, 0.5±0.2 vs. 0.6±0.2 pA/pF, respectively). These results demonstrate that the presence of CFTR at the membrane is required to normalize SOCE. The ability of CFTR to modulate SOCE without being activated by cAMP confirms that down-regulation of SOCE depends on the presence of CFTR protein at the cell surface rather than its channel function.

Figure 6.

SOCE is reduced when ΔF508-CFTR trafficks to the PM, but does not depend on CFTR channel activity. A) Traces of Ca2+i measured in CFBE-WT cells under control conditions (black trace) and after treatment with the CFTR channel inhibitor CFTRinh172 (10 μM; light gray trace). B) Similar experiment with CFTR-ΔF508 cells under control conditions (gray trace) and after incubation at 29°C for 24 h to correct trafficking of the mutant protein (light gray trace). Traces are means ± se of 14–15 CFBE-WT cells and 20–21 CFBE-ΔF508 cells. C, D) AUC (C) and slope (D) of Ca2+i increase in CFBE-WT (control, black bars; CFTRinh172, dark gray bars) and CFBE-ΔF508 cells (control, gray bars; 29°C, light gray bars). Data are means ± se of 27–44 CFBE-WT cells and 39–58 CFBE-ΔF508 cells. E, F) Rate of Mn2+ quench confirms the dependence of SOCE on correction of ΔF508-CFTR trafficking rather than its channel activity, in both CFBE-WT (E; control, black trace; CFTRinh172, light gray trace) and -ΔF508 cells (F; control, gray trace; 29°C, light gray trace). Traces are means ± se of ∼15 cells/condition. G) Summary of the Mn2+ quenching rate measured in 30–36 CFBE-WT cells and 46–90 CFBE-ΔF508 cells. Orai1-mediated current is lowered when ΔF508-CFTR is trafficked to the PM by low-temperature treatment. H–M) ICRAC is normalized by rescue of ΔF508-CFTR trafficking to the cell surface induced by low-temperature treatment. ICRAC was measured in CFBE-ΔF508 cells cultured at 37°C (H) or at 29°C (K) using the same protocol as described in Fig. 5G–L. I/V curves show that 29°C treatment diminished the Ca2+ ICRAC (I) and the Na+ ICRAC (J) in CFBE-ΔF508 cells compared to those incubated at 37°C and were blocked by 5μM Gd3+ (J). L) Data summary of divalent ICRAC density in CFBE-ΔF508 cells at 37°C (n=6) or 29°C (n=8). M) Data summary of monovalent ICRAC density in CFBE-ΔF508 cells at 37°C (n=6) or at 29°C (n=7).

Cell surface expression of Orai1 is increased in CFBE-ΔF508 cells and CF primary HBE monolayers

To investigate whether enhanced SOCE is due to elevated expression of Orai1 on the PM, we performed cell surface biotinylation of CFBE-ΔF508 and -WT cells before and after CPA-mediated store depletion and of CF primary HBE monolayers (Fig. 7A). Remarkably, the steady-state expression of Orai1 at the cell surface was 3-fold higher in CFBE-ΔF508 than in -WT cells under control conditions, and increased dramatically in both cells after CPA-mediated store depletion (Fig. 7A, B). Similarly, in CF primary HBE cells in control conditions, Orai1 is clearly expressed at the cell surface, while in non-CF cells, Orai1 was almost undetectable (Fig. 7C). These differences were apparently due to altered trafficking, since total Orai1 protein expression was not changed. The increase in surface expression of Orai1 in CFBE-ΔF508 cells was studied further during SOCE by quantifying Orai1 coaggregation with STIM1 using ICCS (Fig. 7D, E). CFBE cells were cotransfected with STIM1-GFP and Orai1-mCherry and incubated with CPA to deplete the Ca2+ stores and trigger Ca2+ influx. ICCS was used to measure the percentage of Orai1 clusters that were colocalized with STIM1 clusters in CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells (Fig. 7E). Only a small fraction (∼10–20%) of Orai1 was colocalized with STIM1 under control conditions; however, this increased severalfold after store depletion, and even more colocalization was observed in both WT and ΔF508 cells when calcium was added back to the medium (Fig. 7E). Analysis of particle densities inside colocalized clusters of Orai1 and STIM1 by ICS (see Materials and Methods) revealed a significantly higher number of Orai1 particles during SOCE in CFBE-ΔF508 compared to -WT cells (Fig. 7F), although no difference was found in the number of STIM1 particles. These results clearly demonstrate that Orai1 expression at the PM is increased in CF cells compared to non-CF cells, and this increase in channel density would contribute to the enhanced SOCE.

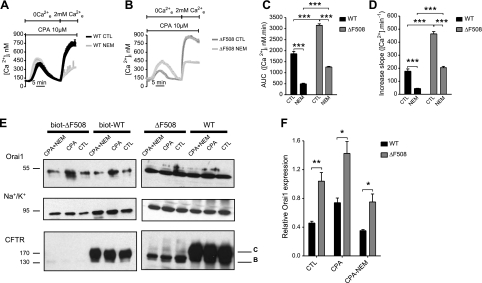

Insertion of Orai1 into the PM is enhanced in CFBE-ΔF508 cells

Recently, it has been shown that most Orai1 is situated in an endosomal compartment under resting conditions, and that it cycles continuously between this compartment and the PM through SNAP-25-dependent exocytosis (41, 42). To examine the role of Orai1 exocytosis we examined CFTR regulation of calcium entry in the presence of N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), an inhibitor of SNARE proteins. NEM treatment dramatically reduced SOCE in both CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells (Fig. 8A, B), although the rise in Ca2+i was more strongly inhibited in WT (73%, n=32) than in ΔF508 cells (60%, n=19; Fig. 8C). Interestingly, the initial phase of Ca2+ influx (i.e., slope) was more strongly inhibited in WT (75%) than in ΔF508 cells (56%, Fig. 8D). Acute perfusion of NEM at the peak of the Ca2+ influx had no inhibitory effect on Ca2+ influx, as compared to the effect of 2-APB (Fig. 3A, B), ruling out a direct inhibitory effect of NEM on Orai1 (data not shown). To confirm the effect of inhibiting exocytosis and insertion of Orai1 into the PM, we also performed cell surface biotinylation during activation of SOCE (Fig. 8E). As expected, NEM abolished CPA-induced Orai1 insertion into the PM in both CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells (i.e., prevented the ∼2-fold increase), although cell surface Orai1 expression remained higher in CFBE-ΔF508 cells by ∼2-fold (Fig. 8F). These results demonstrate that Orai1 channels are inserted during store depletion and this insertion is up-regulated in CFBE-ΔF508 cells.

Figure 8.

Orai1 insertion into the PM is enhanced in CFBE-ΔF508 cells. A–D) Inhibiting exocytosis by NEM reduces SOCE. A, B) Time course of [Ca2+]i showing the inhibition of SOCE when NEM is added along with 2 mM extracellular Ca2+ in CFBE-WT (A; control, black trace; NEM, dark gray trace) and CFBE-ΔF508 cells (B; control, gray trace; NEM, light gray trace). Traces are means ± se of ∼10 cells/condition. C, D) AUC (C) and initial slope (D) measured in CFBE-WT (black bars) and -ΔF508 cells (gray bars) treated with NEM as compared to control. Data are means ± se of 15–32 CFBE-WT cells and 16–19 CFBE-ΔF508 cells. E, F) Cell surface biotinylation studies showing Orai1, Na+/K+ pump and CFTR proteins expression in cells treated with NEM during SOCE. E) Left panels: Western blots showing increase in biotinylated Orai1 during SOCE in CFBE-ΔF508 cells (lanes 2 vs. 3) and CFBE-WT cells (lanes 5 vs. 6) and its inhibition by NEM (lanes 1 vs. 2 and 4 vs. 5). Blocking exocytosis with NEM drastically reduced Orai1 expression on the cell surface in CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells. Orai1 cell surface expression was always higher in CFBE-ΔF508 than in -WT cells. F) Semiquantitative analysis of Orai1 expression at the surface of CFBE-WT (black bars) and -ΔF508 (gray bars) cells under control conditions and after exposure to CPA with or without NEM treatment, normalized to biotinylated α subunit of the Na+/K+ pump. Data are means ± se of 3 experiments. Note that inhibiting exocytosis with NEM under these conditions did not noticeably affect total Orai1 protein expression or surface expression of the Na/K pump.

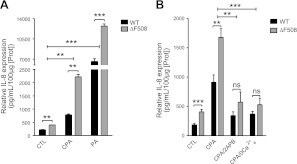

Increased IL-8 secretion is mediated by Orai1-mediated SOCE in CFBE-ΔF508 cells

IL-8 is an important proinflammatory chemokine in airway epithelia, which contributes to the exaggerated inflammatory state of CF airways (43). However, to date it has been unclear whether the Ca2+ influx pathway plays a role in the overproduction of IL-8. The role of SOCE in controlling IL-8 secretion was assessed by measuring IL-8 release into the apical medium of polarized CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells during treatment with 20μM CPA and was compared with IL-8 secretion during infection by PA (Fig. 9A), the most common pathogen in CF. Under basal conditions, CFBE-ΔF508 cells secreted significantly more IL-8 than -WT cells, and on activation of SOCE by CPA the IL-8 secretion was further increased in both CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells, but the increase was always higher in CFBE-ΔF508 than -WT cells (Fig. 9A). PA dramatically stimulated IL-8 release, and this was also significantly higher in CFBE-ΔF508 than in -WT cells (Fig. 9A). The response to PA was 7-fold higher that to CPA alone. To verify that the IL-8 release induced by CPA was via Orai1, cells were treated with CPA and 2-APB (100 μM) or a Ca2+-free solution (Fig. 9B). 2-APB and Ca2+-free solution both inhibited IL-8 secretion induced by CPA in CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells, and both these treatments abolished the difference between -WT and -ΔF508 cells, so that IL-8 release was similar to that under control conditions (Fig. 9B). These results suggest that the SOCE pathway through Orai1 activation modulates IL-8 secretion in human airways and that enhanced SOCE may contribute to the exaggerated inflammatory response in CF.

Figure 9.

Orai1-mediated SOCE induces higher IL-8 secretion in CFBE-ΔF508 cells. A) Effects of CPA and PA on IL-8 secretion in CFBE-WT (black bars) and -ΔF508 cells (gray bars). CFBE cells were grown on filters to polarize and were left untreated or treated with 20 μM CPA or PA (108 CFU/ml) for 4 h at 37°C. Samples were collected from the apical side of the filters, and IL-8 was measured by ELISA. Data are means ± se of 3 experiments. B) Inhibiting Orai1 dramatically reduces IL-8 secretion in CFBE-WT and -ΔF508 cells. Cells grown on filters were untreated or treated with 20 μM CPA with or without SOCE inhibitors (100 μM 2-APB or Ca2+-free solution). Data are means ± se of 5 experiments.

DISCUSSION

Increased Ca2+ signaling in cells expressing ΔF508-CFTR or after knockdown of WT-CFTR has been attributed to enhanced ER Ca2+ release in epithelial cells (7, 8) and smooth and skeletal muscle cells (44, 45). Although a role for CFTR in abnormal Ca2+ signaling has been suggested, the precise mechanisms have remained obscure (10, 39). Here we have shown that SOCE is enhanced markedly in unpolarized and polarized cultures of an hAEC line expressing ΔF508-CFTR and also in polarized CF primary hAEC monolayers. We began these studies after pilot experiments revealed that total Ca2+i influx and the rate of Ca2+ influx during SOCE were both higher in CFBE- and HEK-ΔF508 cells than in corresponding lines expressing WT CFTR (Fig. 1, Supplemental Fig. S1C, D). We found that STIM1 and Orai1, which have been identified as important elements of the SOCE machinery (13, 14, 17, 19), are expressed endogenously in human airways and HEK cells (Fig. 2, Supplemental Fig. S1E). By contrast, although TRPC1 and TRPC4 are also expressed and have been demonstrated to function as SOCs in other cell types (46, 47), we could find no evidence for their involvement in SOCE in hAECs (Figs. 2–5). In our study, TRPC1 and TRPC4 did not form aggregates with STIM1 and Orai1 during store depletion, and TRPC1 was not detected at the PM after store depletion, in contrast to other studies (36, 48). PIP2 inhibits TRPC4 activity; therefore, wortmannin treatment might be expected to cause activation of TRPC4 and increased Ca2+ entry (49). However, SOCE was dramatically inhibited by wortmannin, providing strong evidence against TRPC4 and for the role of Orai1, which is stimulated by PIP2.

The increase in Orai1 surface expression during SOCE and the results obtained using 2-APB, Orai1 siRNA, electrophysiology measurements, MβCD, and wortmannin indicate that Orai1 is the main channel mediating SOCE in airway epithelial cells, and is responsible for augmented Ca2+ entry in ΔF508-CFTR expressing cells (Figs. 3 and 5). Moreover, our results suggest that Orai1 and STIM1 interact in cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains, or at least the mechanisms that couple STIM1 recruitment and Orai1 activation depend on the integrity of those microdomains. Orai1 and STIM1 have been proposed to reside in “lipid rafts” (50), and this proposal would be compatible with our finding that disruption of those microdomains by cholesterol depletion abolishes SOCE modulation by CFTR. Cholesterol-rich lipid rafts have been implicated in numerous signaling pathways (51). Their dynamic formation can initiate signaling either by concentrating a defined number of appropriate proteins or by excluding certain proteins from this membrane structure. CFTR has been shown to be located in such membrane microdomains, where it may activate signaling pathways, including inflammation (52, 53); therefore, the localization of a protein to lipid rafts suggests a possible role in signaling processes. It is conceivable that during the SOCE, CFTR is recruited into the same microdomains as Orai1 and STIM1 aggregates, and modulates SOCE signaling. Enhanced Ca2+ entry in ΔF508 cells may, therefore, reflect an alteration in the dynamics of Orai1/STIM1 complexes at the membrane upon ER store depletion. PIP2 depletion also drastically reduced SOCE (Fig. 3), and phosphoinositides are required for appropriate targeting of STIM1 and for facilitating its interaction with Orai1 (38). PIP2 may help target the macromolecular complex containing Orai1-STIM1 to cholesterol-rich microdomains.

ΔF508-CFTR retention in the ER did not affect STIM1 movement toward the PM after store depletion or its interaction with Orai1 (Fig. 4). Rather, the effect of CFTR is due to an increase in Orai1 density at the cell surface, and this may explain the increase in SOCE and previous studies (9, 10) in which Ca2+ signaling was increased when no WT-CFTR was expressed. Although Orai1 produces an inwardly rectifying Ca2+ conductance (19), studies in which the membrane potential was manipulated during SOCE clearly showed that the increase in Ca2+ entry in CFBE-ΔF508 cells is not due to hyperpolarization (Figs. 5 and 6). Furthermore, CFTR channel inhibition by CFTR-inh172 or activation by forskolin (data not shown), maneuvers that should alter the membrane potential and driving force for Ca2+ entry, also did not affect the CFTR dependence of SOCE, strengthening the conclusion that CFTR channel function is not required. We found that rescuing ΔF508-CFTR protein to the PM did reduce SOCE to normal levels. The amount of the immature band B glycoform in the ER was still comparable to that in untreated cells (Supplemental Fig. S3), but it is noteworthy that a small amount of the mature form of ΔF508-CFTR (band C) appeared after low-temperature rescue, further evidence that some trafficking of CFTR protein to the cell surface was restored. Consistent with the apical localization of Orai1 recently described by Hong et al. (54), SOCE was augmented preferentially at the apical membrane of polarized CFBE-ΔF508 and CF primary HBE monolayers; therefore, its regulation may involve local interactions with apical CFTR channels either directly or through a regulatory complex. Coimmunoprecipitation and GST-pulldown experiments did not reveal a direct interaction between Orai1 and CFTR (data not shown); however, such interactions could be mediated by lipid-rich microdomains, as reported previously (52, 55).

CFTR may promote the assembly of macromolecular signaling complexes at the cell surface (5, 6); thus, further studies should explore whether STIM1-Orai1 and CFTR are part of the same complex or are targeted to the same membrane microdomains (Fig. 4). A major finding in this study was the increased surface expression of Orai1 on CFBE-ΔF508 cells and CF primary HBE monolayers (Fig. 7). Together with the accelerated influx (Fig. 1C), membrane immunolocalization (Fig. 2C), TIRF imaging, and electrophysiology measurements (Fig. 5), the present work indicates that an increase in surface expression of Orai1 contributes to the augmented SOCE. Blocking Orai1 exocytosis strongly inhibited SOCE, suggesting that insertion of Orai1-containing vesicles is required for SOCE, presumably mediated by the SNARE protein SNAP-25 (41). CFTR interacts with SNARE proteins, which may promote vesicle fusion with the PM (56). SNARE proteins are known to regulate ion channel insertion at the apical membrane (57), raising the possibility that CFTR in the cell periphery modulates fusion of Orai1-containing vesicles and thus surface expression.

Another major finding in the present study is that enhanced SOCE through Orai1 in CF cells causes elevated IL-8 secretion compared to non-CF cells, and when SOCE was suppressed by 2-APB or with a Ca2+-free solution, IL-8 secretion was down-regulated (Fig. 9), suggesting a role for Orai1 in the hyperinflammation of CF airways. Neutrophil-associated hyperinflammation has been reported in bronchoalveolar lavages from CF infants without evidence of infection (58), raising the possibility that the increased inflammation is an intrinsic feature of CF, although this remains controversial (39). Fu et al. (12) demonstrated that the absence of extracellular Ca2+ reduced IL-8 secretion induced by concomitant treatment of flagellin (TLR5 agonist) and thapsigargin (a SERCA pump inhibitor). The researchers concluded that a larger Ca2+ influx in CF cells would induce larger innate immune responses to thapsigargin and flagellin than in non-CF cells (12). Our results suggest that elevated IL-8 secretion due to the increased SOCE in CF cells might contribute to the chronic vicious cycle of infections/inflammation in CF. Orai1 is a critical component of the immune system. In mice, Orai1 deficiency severely attenuates cytokine production, including IL-17, IFN-γ, and TNF-α (59, 60). Transferring naive CD4+CD25−CD45RB+ T cells into lymphopenic mice causes severe inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in which naive T cells differentiate into proinflammatory Th1 and Th17 cells (60). Interestingly, although the researchers observed that whereas colons of WT recipients showed severe signs of inflammation, the colons of mice that had received T cells expressing a loss-of-function mutant form of Orai1 were only moderately inflamed and showed few signs of epithelial hyperplasia or loss of goblet cells (60). Some patients with CF develop IBD (61), raising the possibility that increased functionality of Orai1 could be involved in this process. Interestingly, IL-17 is also found in the airways in CF and exacerbates inflammation through the recruitment of neutrophils via secretion of IL-8 (62). Conversely, an increase in SOCE through elevated cell surface expression of Orai1 would be expected to increase IL-17 and augment the production of IL-8, further promoting inflammation in CF.

Further studies are needed to identify the mechanism by which the increased insertion of Orai1 and augmented Ca2+ entry described here contribute to increased release of proinflammatory cytokines (63) and also to establish whether some of many other abnormalities in CF are also a consequence of augmented Ca2+ entry. Cell proliferation (33), altered activity of ion transporters and channels (64) and increased MAPK activity (62) may be influenced by Ca2+ entry. Indeed, Orai1-mediated calcium entry plays an important role in immunity and has been suggested as a potential target for modulating inflammatory pathways (65). Increased cell proliferation has been reported in CF airways (66) and in gastrointestinal epithelia from CF mice (67). Increased inflammation and cell proliferation, which are hallmarks of CF, may be explained in part by the increased Orai1-mediated calcium entry described here. Pharmacological therapies aimed at modulating SOCE through inhibition of Orai1 function may be beneficial in suppressing excess inflammation in CF disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Richard S. Lewis (Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA) for generously providing the STIM1-GFP and Orai1-mCherry plasmids. The authors thank the staff of the McGill University Life Sciences Complex Imaging Facility for excellent technical help and discussion and also the McGill University electron microscopy facility for the technical assistance.

This work was supported by Cystic Fibrosis Canada (CFC) and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Part of this work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants 1R01HL097111 and 5K22ES014729 to M.T. H.B. is supported by a CFC fellowship and B.R. by a Swiss National Science Foundation fellowship. The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gadsby D. C., Vergani P., Csanady L. (2006) The ABC protein turned chloride channel whose failure causes cystic fibrosis. Nature 440, 477–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rommens J. M., Zengerling S., Burns J., Melmer G., Kerem B. S., Plavsic N., Zsiga M., Kennedy D., Markiewicz D., Rozmahel R., Riordan J. R., Buchwald M., Tsui L.-C. (1988) Identification and regional localization of DNA markers on chromosome 7 for the cloning of the cystic fibrosis gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 43, 645–663 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Riordan J. R., Rommens J. M., Kerem B., Alon N., Rozmahel R., Grzelczak Z., Zielenski J., Lok S., Plavsic N., Chou J. L., Drumm M. L., Iannuzzi M. C., Collins F. S., Tsui L. C. (1989) Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science 245, 1066–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hanrahan J. W., Wioland M. A. (2004) Revisiting cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator structure and function. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 1, 17–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Naren A. P., Cobb B., Li C., Roy K., Nelson D., Heda G. D., Liao J., Kirk K. L., Sorscher E. J., Hanrahan J., Clancy J. P. (2003) A macromolecular complex of beta 2 adrenergic receptor, CFTR, and ezrin/radixin/moesin-binding phosphoprotein 50 is regulated by PKA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 342–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guggino W. B., Stanton B. A. (2006) New insights into cystic fibrosis: molecular switches that regulate CFTR. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 426–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weber A. J., Soong G., Bryan R., Saba S., Prince A. (2001) Activation of NF-kappaB in airway epithelial cells is dependent on CFTR trafficking and Cl- channel function. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 281, L71–L78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ribeiro C. M., Paradiso A. M., Carew M. A., Shears S. B., Boucher R. C. (2005) Cystic fibrosis airway epithelial Ca2+ i signaling: the mechanism for the larger agonist-mediated Ca2+ i signals in human cystic fibrosis airway epithelia. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 10202–10209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Antigny F., Norez C., Becq F., Vandebrouck C. (2008) Calcium homeostasis is abnormal in cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells but is normalized after rescue of F508del-CFTR. Cell Calcium 43, 175–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Antigny F., Norez C., Cantereau A., Becq F., Vandebrouck C. (2008) Abnormal spatial diffusion of Ca2+ in F508del-CFTR airway epithelial cells. Respir. Res. 9, 70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ratner A. J., Bryan R., Weber A., Nguyen S., Barnes D., Pitt A., Gelber S., Cheung A., Prince A. (2001) Cystic fibrosis pathogens activate Ca2+-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways in airway epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19267–19275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fu Z., Bettega K., Carroll S., Buchholz K. R., Machen T. E. (2007) Role of Ca2+ in responses of airway epithelia to Pseudomonas aeruginosa, flagellin, ATP, and thapsigargin. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 292, L353–L364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roos J., DiGregorio P. J., Yeromin A. V., Ohlsen K., Lioudyno M., Zhang S., Safrina O., Kozak J. A., Wagner S. L., Cahalan M. D., Velicelebi G., Stauderman K. A. (2005) STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J. Cell Biol. 169, 435–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liou J., Kim M. L., Heo W. D., Jones J. T., Myers J. W., Ferrell J. E., Jr., Meyer T. (2005) STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr. Biol. 15, 1235–1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Luik R. M., Wu M. M., Buchanan J., Lewis R. S. (2006) The elementary unit of store-operated Ca2+ entry: local activation of CRAC channels by STIM1 at ER-plasma membrane junctions. J. Cell Biol. 174, 815–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoth M., Penner R. (1992) Depletion of intracellular calcium stores activates a calcium current in mast cells. Nature 355, 353–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vig M., Peinelt C., Beck A., Koomoa D. L., Rabah D., Koblan-Huberson M., Kraft S., Turner H., Fleig A., Penner R., Kinet J. P. (2006) CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science 312, 1220–1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang S. L., Yeromin A. V., Zhang X. H., Yu Y., Safrina O., Penna A., Roos J., Stauderman K. A., Cahalan M. D. (2006) Genome-wide RNAi screen of Ca(2+) influx identifies genes that regulate Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channel activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 9357–9362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Feske S., Gwack Y., Prakriya M., Srikanth S., Puppel S. H., Tanasa B., Hogan P. G., Lewis R. S., Daly M., Rao A. (2006) A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature 441, 179–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yuan J. P., Zeng W., Huang G. N., Worley P. F., Muallem S. (2007) STIM1 heteromultimerizes TRPC channels to determine their function as store-operated channels. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 636–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vazquez G., Wedel B. J., Aziz O., Trebak M., Putney J. W., Jr. (2004) The mammalian TRPC cation channels. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1742, 21–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pedersen S. F., Owsianik G., Nilius B. (2005) TRP channels: an overview. Cell Calcium 38, 233–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Antigny F., Norez C., Dannhoffer L., Bertrand J., Raveau D., Corbi P., Jayle C., Becq F., Vandebrouck C. (2011) Transient receptor potential canonical channel 6 links Ca2+ mishandling to cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator channel dysfunction in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 44, 83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bruscia E., Sangiuolo F., Sinibaldi P., Goncz K. K., Novelli G., Gruenert D. C. (2002) Isolation of CF cell lines corrected at DeltaF508-CFTR locus by SFHR-mediated targeting. Gene Ther. 9, 683–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Illek B., Maurisse R., Wahler L., Kunzelmann K., Fischer H., Gruenert D. C. (2008) Cl transport in complemented CF bronchial epithelial cells correlates with CFTR mRNA expression levels. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 22, 57–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bebok Z., Collawn J. F., Wakefield J., Parker W., Li Y., Varga K., Sorscher E. J., Clancy J. P. (2005) Failure of cAMP agonists to activate rescued deltaF508 CFTR in CFBE41o- airway epithelial monolayers. J. Physiol. 569, 601–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fulcher M. L., Gabriel S., Burns K. A., Yankaskas J. R., Randell S. H. (2005) Well-differentiated human airway epithelial cell cultures. Methods Mol. Med. 107, 183–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Randell S. H., Walstad L., Schwab U. E., Grubb B. R., Yankaskas J. R. (2001) Isolation and culture of airway epithelial cells from chronically infected human lungs. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 37, 480–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Larsen E. H., Novak I., Pedersen P. S. (1990) Cation transport by sweat ducts in primary culture. Ionic mechanism of cholinergically evoked current oscillations. J. Physiol. 424, 109–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grynkiewicz G., Poenie M., Tsien R. Y. (1985) A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 3440–3450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Epps D. E., Wolfe M. L., Groppi V. (1994) Characterization of the steady-state and dynamic fluorescence properties of the potential-sensitive dye bis-(1,3-dibutylbarbituric acid)trimethine oxonol (Dibac4(3)) in model systems and cells. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 69, 137–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Motiani R. K., Abdullaev I. F., Trebak M. (2010) A novel native store-operated calcium channel encoded by Orai3: selective requirement of Orai3 versus Orai1 in estrogen receptor-positive versus estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 19173–19183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Potier M., Gonzalez J. C., Motiani R. K., Abdullaev I. F., Bisaillon J. M., Singer H. A., Trebak M. (2009) Evidence for STIM1- and Orai1-dependent store-operated calcium influx through ICRAC in vascular smooth muscle cells: role in proliferation and migration. FASEB J. 23, 2425–2437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Comeau J. W., Costantino S., Wiseman P. W. (2006) A guide to accurate fluorescence microscopy colocalization measurements. Biophys. J. 91, 4611–4622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wiseman P. W., Squier J. A., Ellisman M. H., Wilson K. R. (2000) Two-photon image correlation spectroscopy and image cross-correlation spectroscopy. J. Microsc. 200, 14–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mehta D., Ahmmed G. U., Paria B. C., Holinstat M., Voyno-Yasenetskaya T., Tiruppathi C., Minshall R. D., Malik A. B. (2003) RhoA interaction with inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor and transient receptor potential channel-1 regulates Ca2+ entry. Role in signaling increased endothelial permeability. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 33492–33500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Prakriya M., Lewis R. S. (2001) Potentiation and inhibition of Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channels by 2-aminoethyldiphenyl borate (2-APB) occurs independently of IP(3) receptors. J. Physiol. 536, 3–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Walsh C. M., Chvanov M., Haynes L. P., Petersen O. H., Tepikin A. V., Burgoyne R. D. (2010) Role of phosphoinositides in STIM1 dynamics and store-operated calcium entry. Biochem. J. 425, 159–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Machen T. E. (2006) Innate immune response in CF airway epithelia: hyperinflammatory? Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 291, C218–C230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bakowski D., Parekh A. B. (2002) Monovalent cation permeability and Ca(2+) block of the store-operated Ca(2+) current I(CRAC)in rat basophilic leukemia cells. Pflügers Arch. 443, 892–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Woodard G. E., Salido G. M., Rosado J. A. (2008) Enhanced exocytotic-like insertion of Orai1 into the plasma membrane upon intracellular Ca2+ store depletion. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 294, C1323–C1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yu F., Sun L., Machaca K. (2010) Constitutive recycling of the store-operated Ca2+ channel Orai1 and its internalization during meiosis. J. Cell Biol. 191, 523–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. DiMango E., Ratner A. J., Bryan R., Tabibi S., Prince A. (1998) Activation of NF-kappaB by adherent Pseudomonas aeruginosa in normal and cystic fibrosis respiratory epithelial cells. J. Clin. Invest. 101, 2598–2605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Divangahi M., Balghi H., Danialou G., Comtois A. S., Demoule A., Ernest S., Haston C., Robert R., Hanrahan J. W., Radzioch D., Petrof B. J. (2009) Lack of CFTR in skeletal muscle predisposes to muscle wasting and diaphragm muscle pump failure in cystic fibrosis mice. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]