Abstract

Although AMPK plays well-established roles in the modulation of energy balance, recent studies have shown that AMPK activation has potent anti-inflammatory effects. In the present experiments, we examined the role of AMPK in phagocytosis. We found that ingestion of Escherichia coli or apoptotic cells by macrophages increased AMPK activity. AMPK activation increased the ability of neutrophils or macrophages to ingest bacteria (by 46±7.8 or 85±26%, respectively, compared to control, P<0.05) and the ability of macrophages to ingest apoptotic cells (by 21±1.4%, P<0.05 compared to control). AMPK activation resulted in cytoskeletal reorganization, including enhanced formation of actin and microtubule networks. Activation of PAK1/2 and WAVE2, which are downstream effectors of Rac1, accompanied AMPK activation. AMPK activation also induced phosphorylation of CLIP-170, a protein that participates in microtubule synthesis. The increase in phagocytosis was reversible by the specific AMPK inhibitor compound C, siRNA to AMPKα1, Rac1 inhibitors, or agents that disrupt actin or microtubule networks. In vivo, AMPK activation resulted in enhanced phagocytosis of bacteria in the lungs by 75 ± 5% vs. control (P<0.05). These results demonstrate a novel function for AMPK in enhancing the phagocytic activity of neutrophils and macrophages.—Bae, H. -B., Zmijewski, J. W., Deshane, J. S., Tadie, J. -M., Chaplin, D. D., Takashima, S., Abraham, E. AMP-activated protein kinase enhances the phagocytic ability of macrophages and neutrophils.

Keywords: inflammation, phagocytosis, efferocytosis, cytoskeleton

AMPK is a heterotrimeric kinase consisting of an α catalytic subunit and two regulatory subunits, β and γ (1, 2). AMPK activation is classically induced by binding of AMP to the γ subunit, followed by allosteric rearrangement to an active conformation of the AMPKαβγ complex (3, 4). Although the regulation of AMPK activation primarily reflects the amount of bioavailable AMP and the intracellular AMP:ATP ratio, additional mechanisms associated with stress conditions can induce activation of AMPK. For example, phosphorylation of Thr172-AMPKα, binding of glycogen to the AMPKβ subunit, or direct oxidation of cysteines 299 and 304 within the AMPKα1 subunit result in enhanced kinase activity (5–9). Once activated, AMPK down-regulates ATP-consuming events, while inducing catabolic processes that generate ATP, thereby promoting cellular energy preservation (10).

In addition to its role in the regulation of metabolic pathways involving glucose homeostasis, lipid metabolism, and mitochondrial biogenesis, there is growing evidence that AMPK occupies an important role in inflammation (11–15). For example, activation of AMPK was found to decrease production of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, after engagement of Toll like receptor 4 (TLR4) in neutrophils and macrophages (11, 14). AMPK activation in vivo diminished LPS induced acute lung or liver injury (11, 16, 17). AMPK activation was also shown to increase the survival rate of endotoxemic mice (18).

Innate immune responses, including the clearance of invading microbes, and the clearance of apoptotic cells, a process called efferocytosis, play an essential role in host defense and modulation of inflammation (19, 20). For phagocytosis of bacteria and other microorganisms, as well as of apoptotic cells, receptors and ligands on the cell surface permit recognition of the target by macrophages, neutrophils, or other phagocytic cells (21, 22). Cytoskeletal organization, including formation of actin and microtubule networks, is required for engulfment and ingestion of bacteria, apoptotic cells, and nonspecific targets, such as synthetic beads (23–25). In particular, disruption of actin or microtubule was shown to diminish the phagocytic ability of macrophages (24). Small GTPases of the Rho family, such as Cdc42 and Rac1, and downstream effectors, including PAK and WAVE, play essential roles in cytoskeletal formation, including formation of actin and microtubule networks involved in phagocytosis (26). For example, activation of PAK regulates actin cytoskeleton reorganization and cell motility (27, 28), whereas WAVE promotes actin nucleation by activation of the Arp2/3 complex (29). Inhibition of Rac1 signaling significantly decreased macrophage phagocytosis (30). In contrast, activated Rac1 and Cdc42 interact with the microtubule plus-ends tracking protein cytoplasmic linker protein-170 (CLIP-170; ref. 31), which then promotes microtubule stabilization and phagocytosis in macrophages (32). Although recent studies suggest that AMPK can increase Rac1 activity and phosphorylation of CLIP-170 (12, 33, 34), a role for AMPK in phagocytosis has not yet been described.

In the present studies, we found that activation of AMPK increased the phagocytic ability of macrophages and neutrophils through a mechanism dependent on Rac1 and formation of actin and microtubule networks. In addition, we demonstrated that AMPK activation also increased the phagocytosis of bacteria under in vivo conditions in the lungs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Male C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute–Frederick (Frederick, MD, USA). Male mice, 8 to 12 wk old, were used for experiments. The mice were kept on a 12-h light-dark cycle with free access to food and water. All experiments were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Animal Care and Use Committee.

Reagents and antibodies

Fluorescein-conjugated Escherichia coli (K-12 strain) were purchased from Invitrogen (Eugene, OR, USA). RPMI 1640, l-glutamine, penicillin-streptomycin, barberine, metformin, fluorescent carboxylated beads (2 μm), and antibodies to α-tubulin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-d-ribofuranoside (AICAR), nocodazole, and cytochalasin D were purchased from Enzo Life Science (Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA). Antibodies against total and phosphorylated Thr172-AMPK and Ser79-ACC, phosphorylated PAK1 (Ser199/204)/PAK2 (Ser192/197), and WAVE2 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Antibodies to phospho-Tyr150-WAVE and phospho-MYPT1 (Thr696) were purchased from ECM Bioscience (Versailles, KY, USA) and Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA), respectively. The Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 and the AMPK inhibitor compound C were obtained from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA). Custom antibody mixtures and negative selection columns for neutrophil isolation were purchased from Stem Cell Technologies (Vancouver, BC, Canada). Antibodies to CLIP-170 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, whereas anti-phospho-CLIP-170 was generated as described previously (34). Culture medium, scrambled siRNA, and siRNA to the AMPKα1 subunit were purchased from Thermo Scientific/Dharmacon (St. Louis, MO, USA). Hoechst 33342, Alexa Fluor594-conjugated phalloidin, and Alexa Fluor 488- and Alexa Fluor 555-labeled secondary antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Anti-CD11b monoclonal antibody and fluorescent conjugated mouse Fc γ RIIIA/B (CD16) antibody were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA) and R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA), respectively.

Cell isolation and culture

Bone marrow neutrophils were isolated as described previously (35–37). Neutrophil purity was consistently >97%, as determined by Wright-Giemsa-stained cytospin preparations. Neutrophils were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS and treated as indicated in the figure legends. Neutrophil viability under experimental conditions was determined using trypan blue staining and was consistently >95%.

Peritoneal macrophages were elicited in 8- to 10-wk-old mice using Brewer thioglycollate. Cells were collected 5 d after intraperitoneal injection of Brewer thioglycollate and were cultured in 12-well plates (106 cells/well) in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS at 37°C. After 1 h, nonadherent cells were removed by washing with culture medium. The murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 (38) was purchased from American Type Culture Collection. Cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and 4 mM glutamine at 37°C.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (11). Briefly, equal amounts of protein were resolved by 8–12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Immobilon-P; Millipore). To measure total and phosphorylated proteins, membranes were probed with specific antibodies, followed by detection with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG. Bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL Plus; Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and quantified by AlphaEase FC software (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA, USA). Each experiment was carried out ≥2 times using cell populations obtained from separate groups of mice.

siRNA knockdown of AMPKα1

RAW 264.7 cells were incubated with 2 μM scrambled siRNA or siRNA specific to AMPKα1, as described previously (39). Briefly, cells (3×105/well) in 24-well plates were incubated in Accell medium with scrambled siRNA (2 μM) or siRNA (2 μM) to AMPKα1 for 72 h. Cells were treated as described in the figure legends and then subjected to Western blot analysis or phagocytosis assays.

Efferocytosis assay

The ability of macrophages to phagocytose apoptotic cells was determined as described previously (40, 41). In brief, apoptotic neutrophils were obtained by incubation in RPMI 1640 with 1% FBS at 43°C for 1 h, followed by culture for an additional 2 h at 37°C, whereas apoptotic thymocytes were obtained after treatment with dexamethasone. Phagocytosis was initiated by adding apoptotic neutrophils to macrophages (10:1 ratio) or apoptotic thymocytes to macrophages (5:1 ratio) and culturing in RPMI 1640 medium with 1% FBS at 37°C for 90 min or for time indicated in figure legends. Noningested neutrophils were removed by washing the cells 3 times with PBS, and the cells were then fixed with 100% methanol and stained with HEMA3. Phagocytosis was evaluated by an observer masked to experimental conditions through counting 200–300 macrophages/slide from triplicate experiments. The phagocytic index was represented as the percentage of macrophages containing ≥1 ingested neutrophil.

In vitro phagocytosis assay

Phagocytosis of fluorescently labeled E. coli or beads by macrophages or neutrophils was determined by adding a 10-fold excess of E. coli or fluorescent carboxylated beads to the cells. Fluorescent carboxylated beads with 2-μm diameter size were used, as described previously (23–25). To measure internalization of beads or bacteria, fluorescent E. coli or beads were incubated with macrophages for 15 or 20 min at 37°C, and cells were then washed 3 times in ice-cold PBS. Next, cells were incubated with or without trypan blue solution (0.2% trypan blue, 20 mM citrate, and 150 mM NaCl, pH 4.5) for 1 min, then centrifuged, and the cell pellet was resuspended in PBS, followed by flow cytometry. Macrophages were detached from the wells using EDTA (4 mM) in PBS, and the amount of fluorescence was measured using flow cytometry.

Imaging neutrophils or macrophages

Cells were incubated with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature, then washed with PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% TritonX-100/PBS for 4 min. The cells were then washed and incubated with 3% BSA in PBS for 45 min, followed by the addition of Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated phalloidin (25 μl/ml, Invitrogen) for 20 min at room temperature. To image phospho-CLIP-170 or α-tubulin, specific polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies were added overnight at 4°C. The cells were then washed and incubated with fluorescent anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies (Alexa-488 or Alexa-555) for 90 min at room temperature. After the cells were washed with PBS, they were mounted with emulsion oil solution containing DAPI to visualize nuclei. Confocal microscopy was performed as described previously, using a Leica DMIRBE inverted epifluorescence/Nomarski microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) outfitted with Leica TCS NT laser confocal optics (42).

In selected experiments, macrophages were stained with fluorescent-conjugated CD11b antibody (1:200 dilution) overnight at 4°C, or incubated with anti-FcγRIII (CD16) antibody overnight at 4°C, followed by washing and then incubation with fluorescently conjugated secondary antibody for 60 min at room temperature. Cells were washed, and membrane receptors were imaged using confocal microscopy.

RhoA activity assay

RhoA activity was measured in the cell lysates of peritoneal macrophages (106/ml) using an ELISA-based RhoA activation assay (G-LISA; Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

In vivo phagocytosis assay

Mice were given AICAR (500 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle in 0.2 ml of PBS 4 h prior to intratracheal administration of fluorescent E. coli, as described previously (11). Briefly, the tongue was gently extended in isoflurane-anesthetized mice, and the fluorescent E. coli solution (2×107 cells in 50 μl PBS) was deposited into the oropharynx. Typically, ∼2.5 × 105 leukocytes reside in the alveolar space of a naive animal, so the multiplicity of infection (MOI) of this challenge is ∼1:80. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid samples were collected 2 h after administration of E. coli by lavaging the lungs 3 times with 1 ml of iced PBS with 5 mM EDTA. Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and incubated with 0.2% trypan blue solution for 1 min (43), and then nuclei were stained with Hoechst solution. The samples were subjected to confocal microscopy. The amounts of fluorescent E. coli/cell were calculated using IP-lab software.

Statistical analyses

Statistical significance was determined by the Student's t test for comparisons of 2 groups. Multigroup comparisons were performed using 1-way ANOVA with Turkey's post hoc test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

AMPK activation increases macrophage phagocytosis

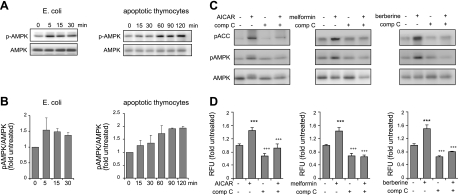

In initial experiments, we determined whether phagocytosis affected AMPK activation in macrophages. As shown in Fig. 1A, B, AMPK phosphorylation increased on culture of macrophages with E. coli or apoptotic thymocytes. Moreover, incubation of macrophages with AICAR, metformin, or berberine resulted in activation of AMPK, as evidenced by increased phosphorylation of Thr172 in AMPK, as well as by phosphorylation of ACC, a downstream target of AMPK (Fig. 1C, D). Such activation of AMPK was diminished when the cells were pretreated with the specific AMPK inhibitor compound C. These results are consistent with previous studies showing that AICAR, metformin, or berberine could activate AMPK, whereas compound C specifically inhibited AMPK activation in multiple cell populations, including macrophages and neutrophils (11, 13).

Figure 1.

AMPK activation increases phagocytosis of E. coli by macrophages. A, B) Peritoneal macrophages (106 cells/ml) were incubated with E. coli (107 cells/ml) or apoptotic thymocytes (5×106 cells/ml) for the indicated times. A) Representative Western blots. B) Ratios of phospho-AMPK to total AMPK. C) Peritoneal macrophages were cultured with AICAR (0 or 1 mM), metformin (0 or 500 μM), or berberine (0 or 10 μM) for 1.5 h. In designated experiments, cells were treated with compound C (comp C; 0 or 10 μM) for 30 min before exposure to AICAR, metformin, or berberine. Representative Western blots show the amounts of total and phospho-AMPK, as well as the levels of phospho-ACC. A second experiment provided similar results. D) Macrophages (1×106) were cultured with or without AICAR (1 mM, 1.5 h), metformin (500 μM, 2.5 h), or berberine (10 μM, 2.5 h), and then were incubated with fluorescent E. coli (10-fold excess over cell numbers) for 15 min. The numbers of cells positive for E. coli uptake were determined using flow cytometry (means±sd from 3 independent experiments). In designated experiments, compound C (10 μM) was included for 30 min before treatment with the AMPK activators. ***P < 0.001 vs. untreated cells; +++P < 0.001 vs. AICAR only.

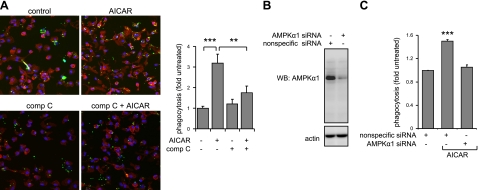

AMPK activation increased the ingestion of fluorescent E. coli by peritoneal macrophages, whereas inclusion of compound C in the macrophage cultures prior to AICAR exposure diminished uptake of bacteria (Fig. 1D). Although AMPK activation significantly increased ingestion of E. coli, only minimal increases in fluorescence intensity for E. coli bound to the macrophage membrane were found for AICAR-treated as compared to control cells (Supplemental Fig. S1A, B). Similar to the results obtained from flow cytometry, microscopic analysis showed that treatment with AICAR increased the numbers of macrophages positive for fluorescent bacteria, an effect that was decreased in compound C-treated cells (Fig. 2A). In addition, knockdown of AMPKα1 in RAW 264.7 cells, which do not contain AMPKα2 (44), inhibited the potentiating effects of AICAR treatment on phagocytosis (Fig. 2B, C).

Figure 2.

AMPK activation increases phagocytosis by macrophages. A) Peritoneal macrophages were cultured with or without AICAR or compound C (comp C) or the combination of AICAR and compound C, as described in Fig. 1B. Representative images show that activation of AMPK increased, whereas compound C diminished, uptake of fluorescent E. coli by the macrophages (means±sd, n=4). Green, E. coli; red, phalloidin; blue, nuclei. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. B) Knockdown of AMPKα1 prevents AICAR-induced increase in macrophage phagocytosis. Representative Western blots show the amounts of AMPKα1 or actin in macrophages treated with nonspecific scramble siRNA (control) or specific siRNA to AMPKα1. C) Phagocytosis was measured in macrophages treated with control (scramble siRNA) or siRNA to AMPKα1. Numbers of cells positive for E. coli were determined using flow cytometry (means±sd from 3 independent experiments). ***P < 0.001 vs. control.

The enhancing effects of AMPK activation on phagocytosis were not limited to macrophages, as culture with AICAR, metformin, or berberine also increased the ability of neutrophils to ingest bacteria (Supplemental Fig. S1C). The ability of AMPK activation to increase phagocytosis was also found with targets other than bacteria, including fluorescent beads (Fig. 3). Activation of AMPK by AICAR or metformin also increased efferocytosis, as evidenced by an increase in the percentage of macrophages that engulfed apoptotic neutrophils (Fig. 3). These results indicate that AMPK activation contributes to a generalized increase in the phagocytic activity of macrophages. The enhancement of phagocytosis found in AMPK-activated macrophages may depend on increased availability of cell surface receptors, including αM integrin or Fc receptors. However, similar distributions of CD11b or FcγRIII (CD16) on the cell surface were present after incubation of peritoneal macrophages with or without AICAR (Supplemental Fig. S4).

Figure 3.

AMPK activation increases phagocytosis of synthetic bead and efferocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages. Macrophages were treated with or without AICAR (1 mM) for 1.5 h or metformin (500 μM) for 2.5 h and then incubated with fluorescent carboxylated beads or apoptotic neutrophils, followed by microscopic analysis. Quantitative data show an increase in the uptake of fluorescent beads (left panel) or apoptotic neutrophils by macrophages stimulated with AICAR (middle panel) or metformin (right panel). Data are means ± sd from 3 independent experiments. ***P < 0.001 vs. untreated cells.

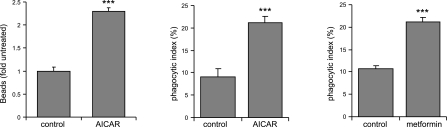

Effects of AMPK activation on microtubule formation and phagocytosis

Although our initial studies showed that AMPK activation participates in regulating phagocytosis, the mechanisms responsible for this effect were not determined. Confocal images demonstrate that cells cultured with AMPK activators exhibit morphological changes, including increased cell size and microtubule formation (Fig. 4A). The increase in cell size and α-tubule network formation found in these experiments was specific for AMPK activation because such effects were diminished by treatment with compound C (Fig. 4A). Similarly, the effects on cell size and morphology associated with AMPK activation were ablated after treatment with nocodazole, which destabilizes microtubule formation (Fig. 4A). The increase in macrophage phagocytosis induced by AMPK activation was diminished by incubation with nocodazole or compound C (Fig. 4B). These findings suggest that enhanced microtubule formation and increased cell size were downstream effects of AMPK activation.

Figure 4.

AMPK activation affects microtubule network formation in macrophages. A) Confocal images show the patterns of α-tubulin in control macrophages or macrophages treated with AICAR and nocodazole or compound C (comp C). B) Macrophages were incubated with AICAR (0 or 1 mM) or nocodazole (20 μM) for 2 h, or nocodazole was added to cells 30 min before exposure to AICAR. Cells were then incubated with fluorescent E. coli for 15 min, and bacterial uptake was determined by flow cytometry (means±sd, n=3). ***P < 0.001.

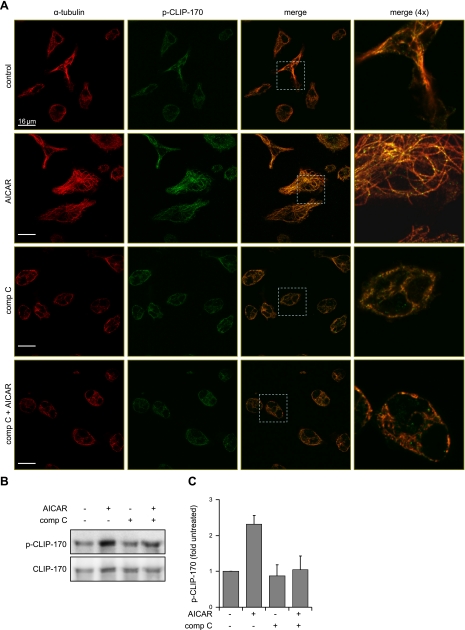

Recent studies have found that AMPK can modulate the rate of microtubule formation, particularly by phosphorylation of the microtubule plus-end protein CLIP-170 (34). To determine whether similar events take place in macrophages after AMPK activation, we examined levels of Ser311 phosphorylated CLIP-170 (phospho-Ser311-CLIP-170) after AICAR treatment. Confocal analysis (see representative images in Fig. 5A) showed that activation of AMPK was associated with colocalization of α-tubulin with phospho-CLIP-170. In contrast, incubation of control or AICAR-treated cells with compound C diminished microtubule formation, as well as the intensity of phospho-CLIP-170 staining. The results obtained from microscopy were confirmed using Western blot analysis of CLIP-170. In particular, levels of phospho-CLIP-170 increased in macrophages after exposure to AICAR, whereas pretreatment with the AMPK inhibitor compound C completely diminished such phosphorylation (Fig. 5B, C).

Figure 5.

AMPK regulates CLIP-170 phosphorylation and microtubule network formation. A) Representative images show fluorescent intensity and subcellular localization of α-tubulin and phospho-CLIP-170 in control macrophages and in macrophages treated with AICAR, compound C (comp C), or the combination of compound C and AICAR. Merged images (dotted white boxes) were magnified to determine colocalization of α-tubulin and phospho-CLIP-170 (yellow). Red, α-tubulin; green, phospho-Ser311-CLIP-170. B) Representative Western blots show total CLIP-170 and phospho-CLIP-170 in control macrophages and macrophages treated with AICAR, compound C, or the combination of compound C and AICAR. Quantitative data are calculated using ratio of phospho-CLIP-170/total CLIP-170. Data are means ± sd from 2 independent experiments.

Effects of AMPK on Rac1 signaling and actin polymerization

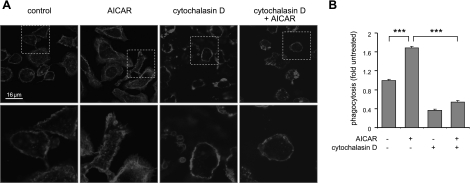

While the above experiments show that AMPK activation results in enhanced phosphorylation of CLIP-170 and microtubule formation, it is possible that AMPK can affect other cytoskeleton regulatory proteins associated with phagocytosis, including those participating in actin polymerization and microtubule stabilization, such as Rac1 and the Rac1 effector proteins p21-activated kinases (PAKs) and WAVE (26, 45). Confocal analysis showed that AMPK activation leads to enhanced intensity of actin staining in macrophages, predominantly in proximity to the membrane ruffles and in finger-like filopodia (Fig. 6A). Moreover, AMPK activation was associated with increased membrane ruffles in neutrophils (Supplemental Fig. S2B). The actin-disrupting agent cytochalasin D diminished the ability of macrophages to ingest E. coli when added to control or AICAR-treated cells (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that AMPK can influence phagocytosis through modulating actin assembly.

Figure 6.

Cytochalasin D diminishes the effects of AMPK activation on actin network formation and macrophage phagocytosis. Peritoneal macrophages were treated with cytochalasin D (0 or 15 μM) for 30 min, and then cultured with AICAR (0 or 1 mM) for 1 h. A) Representative images show fluorescent subcellular patterns of actin in control and treated cells. Areas indicated by dotted white boxes were magnified to demonstrate membrane ruffles. B) Macrophages were incubated with the combination of cytochalasin D (0 or 15 μM) and AICAR (0 or 1 mM) for 1 h followed by inclusion of fluorescent E. coli in the cultures for 15 min and then phagocytosis was determined using flow cytometry. Data are means ± sd. ***P <0.001.

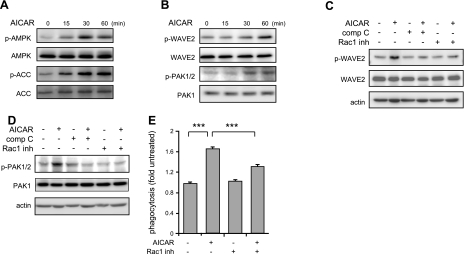

We next determined whether activation of AMPK affects the phosphorylation status of PAK1/2 and WAVE2, two kinases downstream of Rac1 that are known to enhance actin polymerization (26, 45, 46). The addition of AICAR to macrophages resulted in time-dependent increases in the phosphorylation of AMPK, ACC, PAK1/2, and WAVE2 (Figs. 6A, B). Moreover, the effects of AICAR activation on PAK1/2 or WAVE2 phosphorylation diminish when the cells were pretreated with NSC23766, a Rac1 inhibitor, or compound C. Exposure to NSC23766 not only prevented WAVE2 and PAK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 7C, D), but also diminished the ability of macrophages to ingest E. coli (Fig. 7E). Furthermore, NSC23766 disturbed actin reorganization induced by AICAR (Supplemental Fig. S2A). Taken together, these results suggest that AMPK activation, in addition to enhancing CLIP-170-dependent microtubule synthesis, also stimulates phagocytosis through mechanisms that involve activation of signaling cascades downstream of Rac1, and enhancement of actin polymerization.

Figure 7.

Activation of Rac1 signaling cascade is required for AMPK-induced enhancement of macrophage phagocytosis. A, B) Representative Western blots show AICAR dose- and time-dependent activation of AMPK (total and phospho-AMPK or ACC; A) or effects of AMPK activation on total and phospho-WAVE or PAC1/2 (B) in macrophages. C, D) Macrophages were preincubated with compound C (comp C; 0 or 10 μM) or Rac1 inhibitor (NSC23766, 0 or 100 μM) for 30 min and then cultured with AICAR (0 or 1 mM) for 1 h. Representative Western blots are shown. Similar results were obtained from an additional independent experiment. E) Macrophages were treated with NSC23766 (0 or 100 μM) for 30 min and then incubated with AICAR (0 or 1 mM) for 1.5 h. After addition of fluorescent E. coli, phagocytosis was determined by flow-cytometry. Data are means ± sd. ***P < 0.001.

AMPK activation can potentially affect other signaling pathways involved in actin polymerization and endocytosis. To address this issue, we examined whether AMPK activation, in addition to its effects on Rac1, can affect other small GTPases, such as RhoA. As shown in Supplemental Fig. S3, AMPK phosphorylation/activation was inversely correlated with activity of RhoA and levels of phospho-MYPT1, a downstream target for RhoA. Although both Rac1 and RhoA are important in regulating actin polymerization (26), our results suggest that activation of AMPK results in stimulation of signaling cascades involving Rac1/CLIP-170, but inhibition of RhoA.

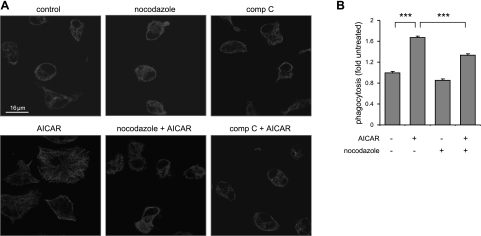

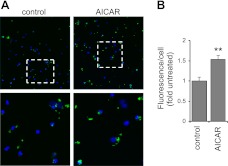

Effects of AMPK activation on phagocytosis in vivo

To examine the effects of AMPK activation on phagocytosis in vivo, mice were treated with AICAR to activate AMPK and were then subjected to intratracheal administration of fluorescent labeled E. coli. We found a modest decrease in glucose levels in AICAR-treated mice. In particular, mean glucose levels were 232.6 ± 28.2 mg/dl before and 203.4 ± 29.5 mg/dl 4 h after treatment with AICAR (n=5 mice/group). The number of engulfed bacteria was measured in alveolar macrophages isolated from BAL fluid. A significant increase in the number of alveolar macrophages positive for ingestion of fluorescent bacteria was found in mice given AICAR as compared to control mice that had received saline vehicle (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

AMPK activation increases the phagocytic ability of macrophages under in vivo conditions in the lungs. Mice were injected with AICAR (0 or 500 mg/kg, i.p.) 4 h before intratracheal instillation of fluorescent E. coli. Representative images (A) and quantitative data (B) show increased uptake of bacteria by macrophages obtained from BAL of AICAR compared to control mice (means±sd, n=4). Green, E. coli; blue, nuclei. Areas in dotted white boxes are enlarged in bottom panels. **P < 0.01 vs. control.

DISCUSSION

The present results demonstrate that activation of AMPK increases the phagocytic activity of macrophages and neutrophils. In cultured macrophages, 3 activators of AMPK, i.e., metformin, AICAR, and berberine, all increased the ability of these cells to ingest bacteria. Although each of these agents has been reported to affect signaling pathways in addition to those associated with AMPK activation, the fact that similar enhancing effects on phagocytosis were found with all of these compounds, despite different mechanisms being involved in AMPK activation (42, 47, 48), provides confidence that AMPK activation is associated with enhanced phagocytosis. Moreover, all effects attributed to AMPK activation in cells treated with AICAR, metformin, or berberine were fully reversible by the addition of the AMPK inhibitor compound C to the cultures. Similarly, siRNA-induced knockdown of the AMPKα1 subunit prevented the AICAR-induced increase in phagocytosis by macrophages. Previous studies, as well as our own results and our unpublished results, have shown that peritoneal or RAW 264.7 macrophages express AMPKα1, but not AMPKα2. These findings indicate that activation of AMPKα1 was sufficient to increase phagocytosis. In addition, activation of AMPK not only increased the ingestion of bacteria by macrophages and neutrophils, but also resulted in enhanced engulfment of other targets, including synthetic beads or apoptotic cells (Fig. 3). Of note, recent studies have shown that metformin-induced activation of AMPK increased the phagocytosis of fluorescent microspheres (49). These data support the conclusion that AMPK activation promotes nonselective phagocytosis rather than utilization of more specific receptor-driven mechanisms that are involved in the recognition of particular targets (21, 22).

The ability of AMPK activation to enhance phagocytosis appears to be related to interaction with cytoskeletal organization, including enhancement of microtubule and actin polymerization. In particular, the effects of AMPK activation on microtubule formation and phagocytosis were diminished by the microtubule-disrupting agent nocodazole, as well as the AMPK inhibitor compound C. A potential mechanism by which AMPK activation produces increased microtubule formation may be through phosphorylation and activation of CLIP-170, consistent with previous studies that described the importance of CLIP-170 on microtubule network formation in phagocytosis (24, 32, 50). In particular, CLIP-170 was shown to regulate microtubule dynamics through coupling to plus-ends of microtubules during tubulin polymerization (51, 52). A recent study found that AMPK can directly regulate the rate of microtubule formation through phosphorylation of CLIP-170 (34). Several previous studies also suggested that CLIP-170 occupies a major role in regulating macrophage phagocytosis, independent of receptor-driven mechanisms that are responsible for recognition of specific targets (32, 53).

Besides activation of CLIP-170, AMPK has also been shown to induce cytoskeletal reorganization, including formation of actin and microtubule networks through activation of Rac1 and associated downstream signaling events (33). In the present studies, we found a marked increase in actin staining in macrophages after AMPK activation. The effects of AMPK activation on actin polymerization and macrophage phagocytosis dissipated after inclusion in the cell cultures of the AMPK inhibitor compound C or after exposure of the cells to cytochalasin D, an agent that prevents actin assembly. These results are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated that cytochalasin D and other compounds that block actin assembly were potent inhibitors of phagocytosis (24, 54). Further, we have shown that PAK1/2 and WAVE2, both downstream components of the Rac1 signaling pathway, were phosphorylated and activated in macrophages after AMPK activation. Of note, activation of Rac1 and PAK phosphorylation was previously described in myoblast cells treated with AICAR (33). Additional evidence for AMPK-dependent regulation of Rac1 and related downstream signaling events was obtained in the present studies by inclusion of the Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 or the AMPK blocker compound C in macrophage cultures, where either compound diminished phosphorylation of PAK1 and WAVE2, actin polymerization, and phagocytosis. Our results are consistent with previous studies showing the ability of AMPK to regulate Rac1 and associated downstream signaling events, and particularly reports demonstrating that AMPK affects the nitric-oxide synthase pathway in endothelial cells or glucose uptake in skeletal muscle cells through mechanisms involving Rac1 activation (12, 33). Of note, Rac1 was previously found to modulate the activity of CLIP-170 in Vero cells (31), findings that are consistent with our results implicating both Rac1 and CLIP-170 as essential mediators in AMPK-dependent activation of phagocytosis. Although AMPK activation is typically associated with reduced energy expenditure, recent studies suggest that cellular processes that require energy are also enhanced by AMPK function. In particular, a recent study has shown that AMPK activation increased cellular motility as a result of tubulin polymerization followed by cytoskeletal reorganization (34). Such findings are consistent with our results that showed a central role for AMPK in cytoskeletal rearrangement and phagocytosis.

In previous studies (11, 13–15), we demonstrated that AMPK activation had potent immunomodulatory effects both in vitro and in vivo. In those experiments, activation of AMPK resulted in diminished production of proinflammatory mediators, including TNF-α, in TLR4-stimulated macrophages and neutrophils. We also found that AMPK activation under in vivo conditions diminished the severity of LPS-induced acute inflammatory lung injury. The results from our present experiments provide further evidence for an important role of AMPK in modulating inflammation and immune responses. In particular, activation of AMPK was associated with increased activity of PAK1 and WAVE2, kinases downstream to Rac1, phosphorylation of CLIP-170, cytoskeletal rearrangement, and enhancement of phagocytosis under both in vitro and in vivo conditions, including ingestion of bacteria by alveolar macrophages. These results delineate a novel role for AMPK in modulating the phagocytic activity of macrophages, neutrophils, and, presumably, of other phagocytic cell populations. The ability of AMPK activation to enhance phagocytosis may be important in host defense through increasing uptake and clearance of bacteria and other microorganisms, and may also contribute to efferocytosis-related resolution of inflammation, resulting in a more effective removal of apoptotic neutrophils and other cell populations from inflammatory foci.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants HL76206 and GM87748 to E.A. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1. Iseli T. J., Oakhill J. S., Bailey M. F., Wee S., Walter M., van Denderen B. J., Castelli L. A., Katsis F., Witters L. A., Stapleton D., Macaulay S. L., Michell B. J., Kemp B. E. (2008) AMP-activated protein kinase subunit interactions: beta1:gamma1 association requires beta1 Thr-263 and Tyr-267. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 4799–4807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Steinberg G. R., Kemp B. E. (2009) AMPK in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 89, 1025–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Scott J. W., Hawley S. A., Green K. A., Anis M., Stewart G., Scullion G. A., Norman D. G., Hardie D. G. (2004) CBS domains form energy-sensing modules whose binding of adenosine ligands is disrupted by disease mutations. J. Clin. Invest. 113, 274–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Towler M. C., Hardie D. G. (2007) AMP-activated protein kinase in metabolic control and insulin signaling. Circ. Res. 100, 328–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stein S. C., Woods A., Jones N. A., Davison M. D., Carling D. (2000) The regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase by phosphorylation. Biochem. J. 345, 437–443 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McBride A., Ghilagaber S., Nikolaev A., Hardie D. G. (2009) The glycogen-binding domain on the AMPK beta subunit allows the kinase to act as a glycogen sensor. Cell Metab. 9, 23–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zmijewski J. W., Banerjee S., Bae H., Friggeri A., Lazarowski E. R., Abraham E. (2010) Exposure to hydrogen peroxide induces oxidation and activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 33154–33164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hawley S. A., Davison M., Woods A., Davies S. P., Beri R. K., Carling D., Hardie D. G. (1996) Characterization of the AMP-activated protein kinase kinase from rat liver and identification of threonine 172 as the major site at which it phosphorylates AMP-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 27879–27887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hawley S. A., Gadalla A. E., Olsen G. S., Hardie D. G. (2002) The antidiabetic drug metformin activates the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade via an adenine nucleotide-independent mechanism. Diabetes 51, 2420–2425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kahn B. B., Alquier T., Carling D., Hardie D. G. (2005) AMP-activated protein kinase: ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab. 1, 15–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhao X., Zmijewski J. W., Lorne E., Liu G., Park Y. J., Tsuruta Y., Abraham E. (2008) Activation of AMPK attenuates neutrophil proinflammatory activity and decreases the severity of acute lung injury. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 295, L497–L504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Levine Y. C., Li G. K., Michel T. (2007) Agonist-modulated regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in endothelial cells. Evidence for an AMPK → Rac1 → Akt → endothelial nitric-oxide synthase pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20351–20364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jeong H. W., Hsu K. C., Lee J. W., Ham M., Huh J. Y., Shin H. J., Kim W. S., Kim J. B. (2009) Berberine suppresses proinflammatory responses through AMPK activation in macrophages. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 296, E955–E964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sag D., Carling D., Stout R. D., Suttles J. (2008) Adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase promotes macrophage polarization to an anti-inflammatory functional phenotype. J. Immunol. 181, 8633–8641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aoki C., Hattori Y., Tomizawa A., Jojima T., Kasai K. (2010) Anti-inflammatory role of cilostazol in vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro and in vivo. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 17, 503–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peralta C., Bartrons R., Serafin A., Blázquez C., Guzmán M., Prats N., Xaus C., Cutillas B., Gelpí E., Roselló-Catafau J. (2001) Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase mediates the protective effects of ischemic preconditioning on hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury in the rat. Hepatology 34, 1164–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zmijewski J. W., Lorne E., Zhao X., Tsuruta Y., Sha Y., Liu G., Siegal G. P., Abraham E. (2008) Mitochondrial respiratory complex I regulates neutrophil activation and severity of lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 178, 168–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tsoyi K., Jang H. J., Nizamutdinova I. T., Kim Y. M., Lee Y. S., Kim H. J., Seo H. G., Lee J. H., Chang K. C. (2010) Metformin inhibits HMGB1 release in LPS-treated RAW 264.7 cells and increases survival rate of endotoxaemic mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 162, 1498–1508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stuart L. M., Ezekowitz R. A. (2008) Phagocytosis and comparative innate immunity: learning on the fly. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 131–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ravichandran K. S., Lorenz U. (2007) Engulfment of apoptotic cells: signals for a good meal. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 964–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dupuy A. G., Caron E. (2008) Integrin-dependent phagocytosis: spreading from microadhesion to new concepts. J. Cell Sci. 121, 1773–1783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Niedergang F., Chavrier P. (2004) Signaling and membrane dynamics during phagocytosis: many roads lead to the phagos(R)ome. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 16, 422–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Newman S. L., Bucher C., Rhodes J., Bullock W. E. (1990) Phagocytosis of Histoplasma capsulatum yeasts and microconidia by human cultured macrophages and alveolar macrophages. Cellular cytoskeleton requirement for attachment and ingestion. J. Clin. Invest. 85, 223–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sulahian T. H., Imrich A., Deloid G., Winkler A. R., Kobzik L. (2008) Signaling pathways required for macrophage scavenger receptor-mediated phagocytosis: analysis by scanning cytometry. Respir. Res. 9, 59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Khandani A., Eng E., Jongstra-Bilen J., Schreiber A. D., Douda D., Samavarchi-Tehrani P., Harrison R. E. (2007) Microtubules regulate PI-3K activity and recruitment to the phagocytic cup during Fcgamma receptor-mediated phagocytosis in nonelicited macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 82, 417–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Iden S., Collard J. G. (2008) Crosstalk between small GTPases and polarity proteins in cell polarization. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9, 846–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Machuy N., Campa F., Thieck O., Rudel T. (2007) c-Abl-binding protein interacts with p21-activated kinase 2 (PAK-2) to regulate PDGF-induced membrane ruffles. J. Mol. Biol. 370, 620–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vidal C., Geny B., Melle J., Jandrot-Perrus M., Fontenay-Roupie M. (2002) Cdc42/Rac1-dependent activation of the p21-activated kinase (PAK) regulates human platelet lamellipodia spreading: implication of the cortical-actin binding protein cortactin. Blood 100, 4462–4469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lebensohn A. M., Kirschner M. W. (2009) Activation of the WAVE complex by coincident signals controls actin assembly. Mol. Cell 36, 512–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Caron E., Hall A. (1998) Identification of two distinct mechanisms of phagocytosis controlled by different Rho GTPases. Science 282, 1717–1721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fukata M., Watanabe T., Noritake J., Nakagawa M., Yamaga M., Kuroda S., Matsuura Y., Iwamatsu A., Perez F., Kaibuchi K. (2002) Rac1 and Cdc42 capture microtubules through IQGAP1 and CLIP-170. Cell 109, 873–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Binker M. G., Zhao D. Y., Pang S. J., Harrison R. E. (2007) Cytoplasmic linker protein-170 enhances spreading and phagocytosis in activated macrophages by stabilizing microtubules. J. Immunol. 179, 3780–3791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee Y. M., Lee J. O., Jung J. H., Kim J. H., Park S. H., Park J. M., Kim E. K., Suh P. G., Kim H. S. (2008) Retinoic acid leads to cytoskeletal rearrangement through AMPK-Rac1 and stimulates glucose uptake through AMPK-p38 MAPK in skeletal muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33969–33974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nakano A., Kato H., Watanabe T., Min K. D., Yamazaki S., Asano Y., Seguchi O., Higo S., Shintani Y., Asanuma H., Asakura M., Minamino T., Kaibuchi K., Mochizuki N., Kitakaze M., Takashima S. (2010) AMPK controls the speed of microtubule polymerization and directional cell migration through CLIP-170 phosphorylation. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 583–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tsuruta Y., Park Y. J., Siegal G. P., Liu G., Abraham E. (2007) Involvement of vitronectin in lipopolysaccaride-induced acute lung injury. J. Immunol. 179, 7079–7086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zmijewski J. W., Zhao X., Xu Z., Abraham E. (2007) Exposure to hydrogen peroxide diminishes NF-κB activation, IκB-α degradation, and proteasome activity in neutrophils. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 293, C255–C266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lorne E., Zmijewski J. W., Zhao X., Liu G., Tsuruta Y., Park Y. J., Dupont H., Abraham E. (2008) Role of extracellular superoxide in neutrophil activation: interactions between xanthine oxidase and TLR4 induce proinflammatory cytokine production. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 294, C985–C993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Raschke W. C., Baird S., Ralph P., Nakoinz I. (1978) Functional macrophage cell lines transformed by Abelson leukemia virus. Cell 15, 261–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Steenport M., Khan K. M., Du B., Barnhard S. E., Dannenberg A. J., Falcone D. J. (2009) Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1 and MMP-3 induce macrophage MMP-9: evidence for the role of TNF-alpha and cyclooxygenase-2. J. Immunol. 183, 8119–8127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Friggeri A., Yang Y., Banerjee S., Park Y. J., Liu G., Abraham E. (2010) HMGB1 inhibits macrophage activity in efferocytosis through binding to the αvβ3-integrin. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 299, C1267–C1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Friggeri A., Banerjee S., Biswas S., de Freitas A., Liu G., Bierhaus A., Abraham E. (2011) Participation of the receptor for advanced glycation end products in efferocytosis. J. Immunol. 186, 6191–6198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zmijewski J. W., Lorne E., Zhao X., Tsuruta Y., Sha Y., Liu G., Abraham E. (2009) Antiinflammatory effects of hydrogen peroxide in neutrophil activation and acute lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 179, 694–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wan C. P., Park C. S., Lau B. H. (1993) A rapid and simple microfluorometric phagocytosis assay. J. Immunol. Methods 162, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jhun B. S., Jin Q., Oh Y. T., Kim S. S., Kong Y., Cho Y. H., Ha J., Baik H. H., Kang I. (2004) 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced TNF-alpha production through inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt activation in RAW 264.7 murine macrophages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 318, 372–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kheir W. A., Gevrey J. C., Yamaguchi H., Isaac B., Cox D. (2005) A WAVE2-Abi1 complex mediates CSF-1-induced F-actin-rich membrane protrusions and migration in macrophages. J. Cell Sci. 118, 5369–5379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Edwards D. C., Sanders L. C., Bokoch G. M., Gill G. N. (1999) Activation of LIM-kinase by Pak1 couples Rac/Cdc42 GTPase signalling to actin cytoskeletal dynamics. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 253–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hawley S. A., Ross F. A., Chevtzoff C., Green K. A., Evans A., Fogarty S., Towler M. C., Brown L. J., Ogunbayo O. A., Evans A. M., Hardie D. G. (2010) Use of cells expressing gamma subunit variants to identify diverse mechanisms of AMPK activation. Cell Metab. 11, 554–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Turner N., Li J. Y., Gosby A., To S. W., Cheng Z., Miyoshi H., Taketo M. M., Cooney G. J., Kraegen E. W., James D. E., Hu L. H., Li J., Ye J. M. (2008) Berberine and its more biologically available derivative, dihydroberberine, inhibit mitochondrial respiratory complex I: a mechanism for the action of berberine to activate AMP-activated protein kinase and improve insulin action. Diabetes 57, 1414–1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Labuzek K., Liber S., Gabryel B., Adamczyk J., Okopien B. (2010) Metformin increases phagocytosis and acidifies lysosomal/endosomal compartments in AMPK-dependent manner in rat primary microglia. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 381, 171–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. McGee K., Holmfeldt P., Fällman M. (2003) Microtubule-dependent regulation of Rho GTPases during internalisation of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. FEBS Lett. 533, 35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Diamantopoulos G. S., Perez F., Goodson H. V., Batelier G., Melki R., Kreis T. E., Rickard J. E. (1999) Dynamic localization of CLIP-170 to microtubule plus ends is coupled to microtubule assembly. J. Cell Biol. 144, 99–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Folker E. S., Baker B. M., Goodson H. V. (2005) Interactions between CLIP-170, tubulin, and microtubules: implications for the mechanism of Clip-170 plus-end tracking behavior. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 5373–5384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lewkowicz E., Herit F., Le Clainche C., Bourdoncle P., Perez F., Niedergang F. (2008) The microtubule-binding protein CLIP-170 coordinates mDia1 and actin reorganization during CR3-mediated phagocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 183, 1287–1298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. DeFife K. M., Jenney C. R., Colton E., Anderson J. M. (1999) Disruption of filamentous actin inhibits human macrophage fusion. FASEB J. 13, 823–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.