Abstract

Aims

The aim of this study is to show the feasibility of a biventricular implantable cardioverter-defibrillator [cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT)–ICD] implantation using an electroanatomic navigation system and a low dose of fluoroscopy. Here four case reports of patients affected by dilated cardiomyopathy, who underwent cardiac resynchronization therapy, are described.

Methods and results

During 2010, four patients were admitted to our Cardiology Department for implantation of an CRT–ICD device in primary prevention. All had an ejection fraction of <35% and were in New York Heart Association class III despite optimal medical therapy. The implantations were performed using the EnSite NavX system. All the leads were positioned in the cardiac chambers utilizing the three-dimensional navigation system and only using X-ray to check that the leads had been positioned correctly. To our knowledge, these cases are the first use of an electroanatomic system for implantation of an CRT–ICD device and in all four cases the cannulation of the coronary sinus (CS) was performed only using the mapping system. Electroanatomic navigation made it possible to minimize X-ray exposure during the implantation of the CRT–ICD device; in addition, the mapping system was used to choose the optimum position of the CS catheter using as reference the maximum activation delay between the two ventricles.

Conclusions

The NavX system shows great potential during the implantation of an CRT–ICD device. It seems to be feasible, safe, and extremely beneficial in terms of a reduction in X-ray exposure. Furthermore, there is benefit of more detailed information and accuracy during the CS lead placement.

Keywords: Implantation biventricular cardioverter-defibrillator, Non-fluoroscopy imaging, Electroanatomic navigation system

Introduction

The transvenous implantation of devices, such as pacemakers and defibrillators, is usually performed with the aid of fluoroscopy as the standard tool for visualization of the leads in the cardiac chambers. This implies radiation exposure for patients and operators. Furthermore, fluoroscopy allows only a two-dimensional (2D) view of catheter movements, making it difficult to position catheters in the complex anatomy of cardiac structures. Recently, systems for non-fluoroscopic 3D catheter navigation through the cardiac chambers and vascular structures have been developed1–3 and there are some cases,4,5 reported in literature, demonstrating the possibility of implanting pacemakers using these tools and without the use of fluoroscopy. Our aim was to study the feasibility and reliability of implanting a three-lead system [biventricular implantable cardioverter-defibrillator—cardiac resynchronization therapy–implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (CRT–ICD) device] guided by an electroanatomic navigation system, which would minimize fluoroscopy use and focus on the evaluation of coronary sinus (CS) vessels.

Methods

During 2010 four patients were admitted to our Cardiology Department for implantation of an CRT–ICD device in primary prevention. Three patients were affected by ischaemic cardiomyopathy and one by non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy. All had an ejection fraction of <35% and were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III despite optimal medical therapy. Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of the patients as well as the procedure times, the fluoroscopy times, the parameters obtained at implant, and the make of the device.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients, procedure times, fluoroscopy times and parameters obtained at implant and the make of the device.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | M | M | M | F |

| Age | 49 | 79 | 80 | 77 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 20 | 34 | 18 | 32 |

| Cardiomyopathy | Ischaemic | Ischaemic | Ischaemic | Non-ischaemic |

| Cardiac rhythm | Atrial fibrillation | Sinus rhythm | Sinus rhythm | Sinus rhythm |

| Bundle branch block | Right bundle branch block (QRS duration = 154 ms) | Bifascicular block (QRS duration = 164 ms) | Left bundle branch block (paced QRS duration = 174 ms) | Left bundle branch block (QRS duration = 164 ms) |

| Other features | AV node ablation after CRT–ICD implantation | Dual chamber pacemaker carrier before CRT–ICD implantation | ||

| Parameters obtained at implant | ||||

| RV-wave amplitude | 9.1 mV | 14.2 mV | 12.5 mV | 9.1 mV |

| RV lead impedance | 955 Ω at 5.0 V | 1156 Ω at 5.0 V | 738 Ω at 5.0 V | 656 Ω at 5.0 V |

| RV threshold | 0.4 V at 0.5 ms | 0.4 V at 0.5 ms | 0.4 V a 0.5 ms | 0.5 V at 0.5 ms |

| RV lead position | Apex | Apex | Mid-septum | Apex |

| P-wave amplitude | 0.9 ms | 3.1 mV | 3.5 mV | 2.2 mV |

| P lead impedance | not determined | 530 Ω at 5.0 V | 479 Ω at 5.0 V | 528 Ω at 5.0 V |

| P threshold | not determined | 1.2 V at 0.5 ms | 4.5 V at 1.6 ms | 1.3 V at 0.5 ms |

| LV-wave amplitude | 19.9 mV | 9.3 mV | 10.1 mV | 1.2 mV |

| LV impedance | 769 Ω at 5.0 V | 1308 Ω at 5.0 V | 1027 Ω at 5.0 V | 475 Ω at 5.0 V |

| LV threshold | 0.3 V at 0.5 ms | 2.0 V at 0.5 ms | 0.3 V at 0.5 ms | 1.9 V at 0.5 ms |

| Target vein for CS lead | Posterior vein | Anterior vein | Lateral vein | Lateral vein |

| LV lead postion | Distal | Distal | Proximal | Mid |

| Manufacturers of the ICD | Boston scientific livian REF H247 | Boston scientific livian REF H247 | Boston scientific livian REF H247 | Medtronic consulta D234TRK |

| Bipolar ICD lead | Guidant Endotak Reliance G REF 0175 (passive fixation, double coil) | Guidant Endotak Reliance G REF 0175 (passive fixation, double coil) | Guidant Endotak Reliance SG REF 0181 (active fixation, single coil) | Medtronic 6935 (active fixation, single coil) |

| Bipolar left lead | Guidant Easytrak 2 REF 4542 | Guidant Easytrak 2 REF 4543 | Guidant Easytrak 2 REF 4542 | Medtronic 4194 |

| Bipolar atrial lead | Guidant, Fineline 2 (passive fixation) REF 4480 | Guidant, Fineline 2 (passive fixation) REF 4480 | Medtronic 4592 (passive fixation) | Medtronic 5594 (passive fixation) |

| Total time for implantation (min) | 168 | 142 | 130 | 124 |

| Length of radiation exposure (DAP) | 16.8 min (2914 cGy×cm2) | 16.9 min (3984 cGy×cm2) | 7.3 min (3946 cGy×cm2) | 4.2 min (1089 cGy×cm2) |

AV, atrioventricular; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; CS, coronary sinus; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; DAP, dose area product.

The implantation was performed using the EnSite NavX system (St Jude Medical, Endocardial Solutions Inc., St Paul, MN, USA). Three pairs of adhesive electrodes were placed on the chest of each of the patients configuring orthogonal axes and a low-power 5.7 kHz electrical potential was generated across each pair of electrodes (as previously reported in the paper by Ruiz-Granell et al.5 published in Europace). The voltage gradient from each axis helps to generate a 3D navigation field. After the electrodes' size and the inter-electrode spacing has been chosen for each of the catheters, the EnSite system can be used to create geometric models of the patient's cardiac chambers and show in real-time a 3D image of the catheters' location. The EnSite NavX system can be also used to measure the distance between points on the geometric model of the endocardial surface, using the Field Scaling algorithm. Field Scaling is based on geometrical points collected in continuous mode by catheters with defined inter-electrode spacing. Adjustments to the dimensions of the navigation field are made considering the known inter-electrode spacing of the catheters used to create the geometry of the 3D model.

The same experienced cardiologist performed all four procedures. Under local anaesthesia with lidocaine, the left subclavian vein was cannulated three times in order to introduce three different wires. The implantation method was always performed as follows:

First, a bipolar ICD right ventricular lead connected to the NavX system was introduced through a 9F sheath and used to map reference points for the superior vena cava, and then to create a rough 3D model of the right atrium and the right ventricle. After the 3D model had been created, the lead tip was positioned in the apex of the right ventricle and a shadow was registered to check that it remained in its position during the rest of the procedure. The position was also confirmed by a 12-lead electrocardiogram (paced QRS complex morphology) and by a single shot of fluoroscopy. Only in one case (Case 3), the ICD lead was positioned in the mid-septum of the right ventricle (active fixation) due to the presence of a pacemaker lead in the apex from a prior implantation.

Second, a 5F quadripolar electrophysiological catheter, connected to the NavX system, was introduced through the left subclavian vein using a 10F valved sheath. The electrophysiological catheter was introduced via the delivery system and was used to cannulate and to map the CS without resorting to fluoroscopy and it was also used to complete the 3D model of the right atrium (see Figure 1). Short bursts of fluoroscopy were used to check the position of the CS and perform CS angiography. Then, the electrophysiological catheter was withdrawn leaving the delivery system in the CS and through this a bipolar left ventricular lead was immediately inserted. With small movements of the left ventricular lead, connected to the NavX, it was possible to create the 3D map of the CS branches following the CS angiography imaging. When necessary, especially for the smallest vessels, wire incannulation was performed using fluoroscopy. However, for the subsequent selective lead introduction the NavX system was used. During vessel mapping, a number of points were collected and the local ventricular activation time and the bipolar voltage amplitude were recorded on the map during sinus rhythm. The right ventricular electrogram was used as reference during the NavX activation map. The final position of the CS lead in the target vessel was chosen first in relation to the maximum activation delay between the electrogram in the right ventricle and the electrogram in the CS branch as shown on the activation map in Figure 2, but also considering the following factors: stable lead position in the vessel, absence of phrenic nerve stimulation, and an acceptable pacing threshold. As is very often the case, the last three factors led to some compromise in the choice of the final CS lead position.

Finally, the right atrial lead, connected to the NavX system, was placed in the right auricle guided by the navigation system, which at the same time continued to check on the location of the other catheters and was used to help maintain their original position.

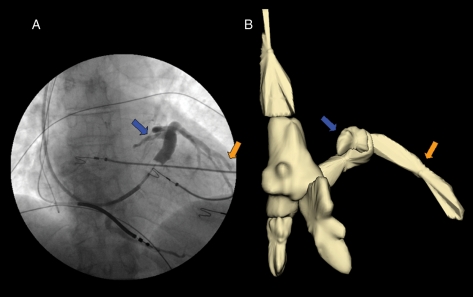

Figure 1.

Case 4. (A) The coronary sinus angiography performed with the Swan-Ganz catheter in a antero-posterior projection. The blue and orange arrows indicate the coronary sinus and the presence of a lateral vein, respectively. This image also shows the presence of a bipolar implantable cardioverter–defibrillator lead placed in the apex of the right ventricle and it is possible to see the tip of a J-wire in the right atrium. (B) Reconstruction of the right cardiac chambers, the superior and inferior vena cava and the coronary sinus using the NavX system; the blue and orange arrows indicate the three-dimensional reconstruction of the coronary sinus and the lateral vein, respectively.

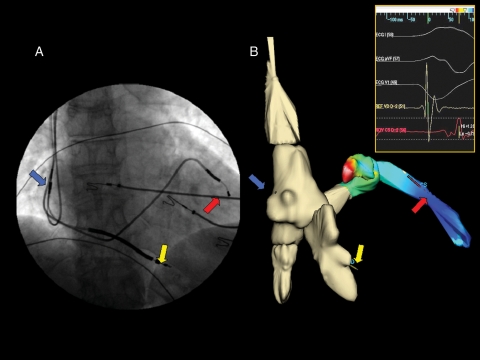

Figure 2.

(A) Final implantation of the cardiac resynchronization therapy–implantable cardioverter–defibrillator device in an antero-posterior projection and the arrows indicate the three-lead positions (blue arrow, right atrial lead; yellow arrow, right ventricular lead; and red arrow, left ventricular lead). (B) The same view of the final implantation of the cardiac resynchronization therapy–internal cardioverter-defibrillator device constructed using the NavX system. It is easy to appreciate how the two images correspond as regards the final position of the leads. The coronary sinus and the lateral vein in (B) also show the activation colour map of the left ventricle during sinus rhythm constructed using NavX system; the purple colour indicates the position of the maximum delay of ventricular activation and therefore the best final position for the left lead. The insert shows the electrograms of the right and left ventricle recorded by the leads during sinus rhythm.

For each procedure the fluoroscopy time, the Dose Area Product (DAP), the time duration and all the lead pacing/sensing parameters were recorded (see Table 1).

Results

All the leads were positioned in the cardiac chambers utilizing, for the most part, the 3D navigation system and only using X-ray to check that they had been positioned correctly (by means of a very low number of oblique projections). It is worth noting that in all the patients the CS was cannulated with the aid of NavX imaging and without X-ray. As shown in Table 1, a progressive reduction in fluoroscopy time was observed from the 16.9 min of the first procedure to the 4.2 min of the last one suggesting improved skill and familiarity with the use of the NavX system for CRT–ICD implantation.

All the implantations were successful and the final pacing/sensing parameters of the three leads (see Table 1) were in the normal range.

No complications were observed during the four procedures and there was no evidence of lead dislodgement the day after implantation. For all four patients, at the 3-month follow-up, the CRT–ICD device was functioning properly with adequate pacing and sensing thresholds and each showed a typical biventricular stimulation at the electrocardiographic registration. All the patients moved up a NYHA class and the physicians considered them CRT responders.

Discussion

There are a number of important aspects in this report:

To our knowledge, these four cases are the first use of an electroanatomic navigation system for implantation of a CRT–ICD device.

In all four cases, the cannulation of the CS was performed only using the mapping system and at the end of the manoeuvre a single shot of fluoroscopy was employed to confirm the correct placement of the delivery system.

Reconstructing the complexities of the cardiac-vein anatomy and guiding the catheter to the target CS vessel using the electroanatomic navigation system proved to be feasible and reliable.

Throughout this approach, it was possible to check the position of each lead at any time without the use of fluoroscopy.

The electroanatomic navigation system allowed us to minimize X-ray exposure during the implantation of the CRT–ICD device and in particular during the placement of the CS lead. The mean total fluoroscopy time for CRT–ICD implantation in previous papers ranged from 23.9 ± 18.1 min6 to 46 ± 23 min7. These four cases show that fluoroscopy time decreased from 16.9 to 4.2 min and this may suggest that ‘near zero’ fluoroscopy use for CRT–ICD implantation is feasible. Furthermore, it would seem that the learning curve for CRT–ICD implantation using an electroanatomic navigation system, in centres with experience with this technology for catheter ablation, is short and easy.

The mapping system was used to choose the optimum position of the CS lead in the target vessel using as reference the maximum activation delay between the two ventricles. Pacing the left ventricle at the most delayed site is now considered a good marker for promoting contractile synchrony and improving ejection fraction.6,7

Conclusion

The use of an electroanatomic navigation system (NavX system) in CRT–ICD implantation shows great potential. It seems to be feasible and safe but the possibility of minimizing X-ray exposure both for patients and physicians is the most attractive aspect. Furthermore, there is the benefit of more detailed information and accuracy during the CS lead placement, both in terms of 3D anatomy knowledge and ventricular activation time, which optimize the pacing site choice. However, similar procedures recounted in studies, case reports or ideally in randomized trials and their reports, would be needed to confirm the experience detailed in this study.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Funding

Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Valmar srl.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Engineer Stefano Indiani (St Jude Medical), his technical support and expertise and Seán Somers for proofreading and correcting the English in the paper.

References

- 1.Gepstein L, Hayam G, Ben-Haim SA. A novel method for nonfluoroscopic catheter-based electroanatomical mapping of the heart. In vitro and in vivo accurancy results. Circulation. 1997;95:1611–22. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.6.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ventura R, Rostck T, Klemm HU, Lutomsky B, Demir C, Weiss C, et al. Catheter ablation of common type atrial flutter guided by three-dimensional right atrial geometry reconstruction and catheter tracking using cutaneous patches: a randomized prospective study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004;15:1157–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2004.04064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Novak PG, Macle L, Thibault B, Guerra PG. Enhanced left atrial mapping using digitally synchronized NavX three-dimensional nonfluoroscopic mapping and high-resolution computed tomographic imaging for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2004;4:521–2. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruiz-Granell R, Morell-Cabedo S, Ferrero A, Garcia-Civera R. Atrioventricular node ablation and permanent ventricular pacemaker implatation without fluoroscopy: use of an electroanatomic navigation system. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:793–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2005.40774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruiz-Granell R, Ferrero A, Morell-Cabedo S, Martinez-Brotons A, Bertomeu V, Llacer A, et al. Implantation of single-lead atrioventricular permanent pacemakers guided by electroanatomic navigation without the use of fluoroscopy. Europace. 2008;10:1048–51. doi: 10.1093/europace/eun139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan FZ, Virdee MS, Fynn SP, Dutka DP. Left ventricular lead placement in cardiac resynchronization therapy: where and how? Europace. 2009;11:554–61. doi: 10.1093/europace/eup076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ansalone G, Giannantoni P, Ricci R, Trambaiolo P, Fedele F, Santini M. Doppler myocardial imaging to evaluate the effectiveness of pacing sites in patients receiving biventricular pacing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:489–99. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01772-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]