Abstract

Background

Few data are available on access to contraception following a natural disaster. The current study extends the literature by examining access to various types of birth control in a large sample of women from diverse backgrounds following Hurricane Ike, which made landfall on September 13, 2008, on the upper Texas Gulf Coast.

Methods

We examined Hurricane Ike's influence on access to contraceptives through survey results from 975 white, black, and Hispanic women 16–24 years of age receiving care at one of five publicly funded reproductive health clinics in the Texas Gulf Coast region between August 2008 and July 2010.

Results

Overall, 13% of women reported difficulties accessing contraception. Black women had more difficulty than their white (p<0.001) and Hispanic (p=0.019) counterparts. Using multivariate analysis, we found that although family planning clinics in the area were open, black women (odds ratio [OR] 2.25, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.37–3.73; p=0.001] and hurricane evacuees (OR 2.17, 95% CI 1.27-3.72; p=0.005) reported greater difficulty in accessing birth control. Last, we found that a lack of access to birth control was related to having a higher frequency of unprotected sex for women of all races (p=0.001).

Conclusions

Access to resources is critical in differentiating the level of impact of disasters on various groups of people. We suggest a community-based disaster preparedness and response model that takes women's reproductive needs into account.

Introduction

The devastating effects of natural disasters uncover social inequalities such as the differential distribution of resources1,2 that often affect racial/ethnic minorities, women, children, the poor, and the elderly the most.3–11 The relationship between race/ethnicity or class inequalities and natural disasters has been studied in the past decade.12 With regards to gender, studies illustrate that natural disasters adversely affect women in a number of ways, including more reproductive tract infections, shortened life expectancy,13,14 increased number of children,15 early onset of labor,16–18 and infertility.16,19,20 In addition, women subjected to natural disasters are more prone to sexual violence as well as higher states of anxiety and depression and may face a lack of access to feminine hygiene products and prenatal care.16,21

It is also possible that natural disasters create difficulties with contraceptive access. One prior study found a lack of access to contraception following Hurricane Katrina after conducting interviews with 55 predominantly black women.19 This report adds to their findings by examining birth control by method, in a larger sample of women from diverse backgrounds following Hurricane Ike, which made landfall on September 13, 2008, on the upper Texas Gulf Coast.22 This hurricane resulted in a mandatory evacuation for all residents in a large geographic region.23 In many cases, it was weeks before people could move back into their homes.24 In this study, we examined whether Hurricane Ike created an environment that restricted access to birth control as self-reported by non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic women who received reproductive care at public clinics.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey on health behaviors among women 16–24 years of age between August 2008 and July 2010 attending one of five publicly funded reproductive health clinics. On September 13, 2008, Hurricane Ike struck the Gulf Coast, affecting many women who received care in these clinics. To obtain information on the hurricane's effect on their access to birth control, additional questions were added to the ongoing survey in November 2008, 2 months after the storm. The mean number of respondents per month during the 2-year collection period was 136±60.0 (range, 44–249). There was a general downward trend over time in the number of respondents who answered hurricane-related questions as the time since the disaster increased.

All surveys were self-administered, and those who agreed to participate were reimbursed $5 for their time. To assure that patients completed the survey only once during this 2-year interval, study personnel maintained a cumulative database containing the names of those who had previously completed the survey and compared it daily to the names of those appointed for a visit. Women who had previously completed the survey were not approached a second time. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Medical Branch.

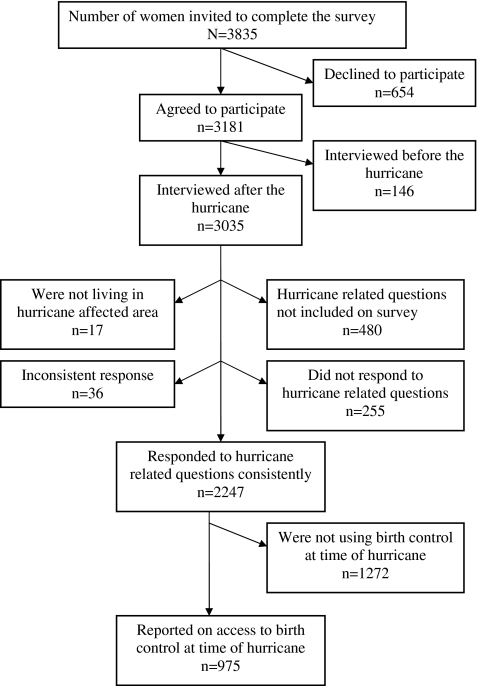

Overall, 654 women declined when asked to participate in the general survey. During the 2-year interval examined in this study, the survey was administered to 3181 women (Fig. 1). For this report, we excluded the following respondents: 146 women who were interviewed before the hurricane, 480 women who took the survey before hurricane-related questions were added, 255 women who did not respond to the hurricane-related questions, 17 women who were not living in hurricane-affected areas, and 36 women with inconsistent responses. Thus, data from a total of 2247 women were analyzed.

FIG. 1.

Flow diagram for final sample size.

Since contraceptive use at the time of the disaster and living in an effected area were inclusion criteria, we elected to omit 1272 women who reported that they were not using any birth control at the time of the hurricane. The remaining 975 women were eligible for inclusion in this study. The respondents (n=2247) and nonrespondents to Hurricane Ike questions (n=735 who answered the survey before the storm or did not respond to the hurricane-related questions) did not greatly differ by age (mean age 20.7 vs. 21.0 years), but differed by race/ethnicity. White (30.6% vs. 22.2%) and black (27.6% vs. 18.9%) women were more likely to be included than Hispanic women (41.8% vs. 59.0%).

Through three questions, the 975 eligible women reported on their access to contraceptives following Hurricane Ike. The first question was “What method of birth control were you using when Hurricane Ike made landfall?” There were eight possible responses for types of birth control, including not using any birth control. The second question prompted a “yes” or “no” response and assessed if women were unable to use their birth control due to the storm: “Did you experience a time when you were unable to use your birth control because of Hurricane Ike?” Although there may be other reasons why women were unable to use their birth control due to the hurricane (e.g., a pill pack got wet), we made the assumption that access was the primary problem based on their responses to the third question. This question solicited reasons for the inability to use birth control with eight possible answers (see Table 1): “Why were you unable to use your birth control because of Hurricane Ike? Mark all that apply.”

Table 1.

Reasons Unable to Access to Birth Control Method by Race/Ethnicity

| Reasona | Overall | White | Black | Hispanics | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upset | 14 (1.6) | 5 (1.6) | 5 (2.0) | 4 (1.2) | 0.704 |

| Partner did not have condom | 21 (2.4) | 2 (0.7) | 9 (3.6) | 10 (3.1) | 0.029 |

| Unable to get shot on time | 21 (2.4) | 4 (1.3) | 17 (6.9) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| No appointment for shot | 21 (2.4) | 5 (1.6) | 13 (5.2) | 3 (0.9) | 0.004 |

| Did not bring pill pack | 19 (2.2) | 4 (1.3) | 5 (2.0) | 10 (3.1) | 0.316 |

| Finished pill pack | 14 (1.6) | 3 (1.0) | 3 (1.2) | 8 (2.5) | 0.318 |

| No refill | 12 (1.4) | 4 (1.3) | 6 (2.4) | 2 (0.6) | 0.168 |

| No appointment for pills | 14 (1.6) | 7 (2.3) | 4 (1.6) | 3 (0.9) | 0.364 |

| No patch | 7 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (1.2) | 3 (0.9) | 0.509 |

| Other | 12 (1.4) | 2 (0.7) | 6 (2.4) | 4 (1.2) | 0.214 |

Reasons unable to access birth control did not vary by age group (16–19 years vs. 20–24 years).

Other questions included evacuation status before the hurricane (yes or no) and unprotected sex during the month of the hurricane: “Thinking back to the month of Hurricane Ike (September 12 to October 12), how many times did you have sex when you were not using birth control (you did not have condoms, birth control pills, your shot had run out, or you needed to replace your patch)?” Survey responses were: 0, 1–3, and 4+ times.

Demographic variables included marital status, household income, education level, and age, which was calculated using years and months. Race and ethnicity were also self-reported with choices including non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian/Alaskan native, native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, or other. No classification was available for mixed race. We restricted our analysis in this paper to non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic women due to the limited sample size (n=7) of other categories.

Bivariate comparisons were performed using a chi-square test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify correlates of an inability to access contraceptives. Variables were screened for inclusion in an initial multivariable model and candidate variables with p≤0.20 were retained. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test25 was used to assess the fit of the final model. All analyses were performed using STATA 11 (Stata Corporation).

Results

The mean age of the 975 women who reported using birth control at the time of the hurricane and responded to other Hurricane Ike questions was 21.0±2.5 years. The racial composition was 334 (34.3%) non-Hispanic white, 271 (27.8%) non-Hispanic black, 363 (37.2%) Hispanic, 6 (0.6%) Asian, and 1 American Indian/Alaskan Native (0.1%). The vast majority reported that they had access to contraception after Hurricane Ike (n=848; 87%), yet 127 (13%) women reported an inability to access their birth control method due to the hurricane. Black women had particular difficulty as compared with their white (19.2% vs. 8.7%; p<0.001) and Hispanic (19.2% vs. 12.4%; p=0.019) counterparts. No difference was found between white and Hispanic women (8.7% vs. 12.4%; p=0.112).

Race/ethnicity and evacuation status were both positively associated (p=0.001) with a lack of access to birth control (Table 2). Further, over half of the women had sex without access to any form of birth control: 34.2% reported one to three episodes of unprotected sex and 21.4% reported four or more episodes during the month of the hurricane. The association between engaging in unprotected sex and a lack of access to birth control was statistically significant (p<0.01) across all races (data not shown). Nonsignificant correlates for access/no access were age, marital status, education, and household income.

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics by Access to Contraceptive Methods

| Had access (n=848) | No access (n=127) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 21.0 (2.4) | 20.9 (2.6) | 0.654 |

| Race/ethnicitya | 0.001 | ||

| White | 305 (36.2) | 29 (23.0) | |

| Black | 219 (26.0) | 52 (41.3) | |

| Hispanic | 318 (37.8) | 45 (35.7) | |

| Marital status, (%)b | 0.955 | ||

| Single, never married | 529 (62.6) | 79 (62.2) | |

| Living together/married | 280 (33.1) | 42 (33.1) | |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 36 (4.3) | 6 (4.7) | |

| Education, (%)c | 0.775 | ||

| Did not complete high school | 127 (15.1) | 21 (16.8) | |

| High school graduated | 414 (49.2) | 63 (50.4) | |

| At least some college | 301 (35.8) | 41 (32.8) | |

| Household income, (%)e | 0.462 | ||

| <$30,000 | 626 (82.5) | 93 (85.3) | |

| $30,000 or more | 133 (17.5) | 16 (14.7) | |

| Evacuation statusf | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 600 (72.0) | 106 (86.2) | |

| No | 233 (28.0) | 17 (13.8) | |

| Birth control methodg | 0.360 | ||

| Pills | 343 (42.5) | 49 (38.6) | |

| Shot | 213 (26.4) | 33 (26.0) | |

| Condoms | 124 (15.4) | 17 (13.4) | |

| Ring/IUD/patch/implant/others | 128 (15.8) | 28 (22.1) | |

| Unprotected sexh | <0.001 | ||

| None | 663 (83.9) | 52 (44.4) | |

| 1–3 times | 83 (10.5) | 40 (34.2) | |

| 4 or more times | 44 (5.6) | 25 (21.4) |

SD=standard deviation.

Five Asians and one Native American were in the “had access” group while 1 Asian was in “no access” group.

Three women did not answer in the “had access” group.

Two women in the “no access” group and six women in the “had access” group did not answer this question.

Or currently enrolled.

One women in the “no access” group and four women in the “had access” group did not answer this question.

Four women in the “no access” group and 15 women in the “had access” group did not answer this question.

Thirty-seven women did not answer in the “had access” group.

Ten women in the “no access” group and 58 women in the “had access” group did not answer this question.

When reasons for being unable to access birth control were examined, we noted that black women were either unable to get their injectable contraception on time (p<0.001) or could not get an appointment for the shot (p=0.004; Table 1). Responses to the statement “Partner did not have a condom” were also statistically significant, but the percentage difference between the groups was small.

Variables that met the screening criteria for inclusion in the multivariable model were race/ethnicity and evacuation status after Hurricane Ike. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test showed a good fit of the model as the final logistic model yielded a p value of 0.282 (χ2=2.53). As shown in the final logistic model, black women had significantly more trouble accessing contraceptives during the hurricane (OR 2.25, 95% CI 1.37–3.73; p=0.001) compared with white women (Table 3). Those who evacuated during Hurricane Ike were also more likely to have barriers to access contraceptives compared with their counterparts (OR 2.17, 95% CI 1.27–3.72; p=0.005).

Table 3.

Correlates of Inability to Access Contraceptives During Hurricane Ike

| Characteristics | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | Reference | |

| Black | 2.25 (1.37–3.73) | 0.001 |

| Hispanic | 1.44 (0.87–2.38) | 0.154 |

| Evacuation | ||

| No | Reference | |

| Yes | 2.17 (1.27–3.72) | 0.005 |

Based on logistic regression analysis. Dependent variable: restricted contraceptive access (yes=1, no=0). Predictors: race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white=0, non-Hispanic black=1, Hispanic=2). Evacuation status (yes=1, no=0). CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

Most women responding to the survey had access to birth control in the immediate period after the largest hurricane to hit the Galveston Bay area in decades. This is likely because the University of Texas Medical Branch family planning clinics that provide extensive services across the region re-opened within days of the storm making landfall. However, we did observe that those who evacuated their homes reported less access to birth control after the disaster. This may have occurred because they were no longer living within commuting distance of their regular clinic and may not have had the resources to access another provider. This is consistent with the observation that those with less social and economic capital have fewer resources for pre- and postdisaster help.26 Birth control may also have not been prioritized, given the many competing demands with family, home, and jobs that people are concerned about postdisaster.19

Those who had the most difficulty accessing contraception were non-Hispanic black women using injectable contraception, which suggests that appointment timing was an issue. It is possible that transportation, other family and home demands, inadequate knowledge of access and location of unfamiliar clinics, displacement and rebuilding obligations, or other issues were factors in the inability to obtain timely contraception. These data are particularly significant, given that national data show that black, compared with white, women have higher utilization rates of injectable contraceptives27 and a greater need for access to birth control.28

We also observed that a lack of access to birth control was positively correlated with an increase in the frequency of unprotected sex. This is crucial information because women in disaster situations are at higher risk of both unintended pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases.29 This is a curious finding, and one not shown in other studies. We were unable to find other correlates and cannot rule out that this may be a spurious correlation whose confounding variable remains unknown. One explanation may be that increased stress led to a higher frequency of sexual intercourse, although those who had access to birth control also had high amounts of stress. An increase in unprotected sex may also have been related to power outages in the area for several weeks,30 although one previous study found that power blackouts do not necessarily lead to an increase in sexual frequency.31

One prior study reported that frequency of sexual intercourse is positively associated with the effectiveness of the contraceptive method being used.32 In lieu of this research, perhaps our finding can be partially explained by the fact that women in our study using Depo Provera® had the most trouble accessing their birth control. We do not have data on sexual behavior before the storm and thus cannot determine if these women exhibited similar behaviors before the disaster. For example, we do not know if these women had higher coital frequency before the storm and did not alter their behaviors when they were unable to obtain their contraception after the storm. With so many distractions, birth control may not have been prioritized or thought about as much.

The one existing study on access to contraception after a hurricane does have predisaster data, but not on frequency of sexual intercourse. In that study, 55 of the original 164 participants were contacted 5–6 months post-hurricane. The participants compared their pre- and postdisaster condom usage as “more,” “less,” “same,” or “don't use condoms.” The majority reported using condoms the same amount as they did before the storm, but because the amounts were not specified, we do not know their frequency of (un)protected sex. Further, 17 (31%) of these women had trouble getting the pill, patch, or Depo Provera. However, these three methods were grouped together so it is not apparent whether they had particular difficulty in obtaining Depo, as the women in our study did. Last, although the study shows a reduction in risk behaviors measured by fewer sexual partners and vaginal douching, frequency of sexual intercourse is not recorded.19

This study has several limitations. We included self-reported information on sensitive issues, such as sexual behavior, that may be subject to under-reporting. Further, we examined the ability to access contraception in young, low-income women, so we do not know whether these findings are generalizable to other populations. Last, recall bias cannot be ruled out as some women reported information on the effects of Hurricane Ike up to almost 2 years after the incident.

Despite these limitations, our work adds to the literature because it is among the first to examine the effects of a hurricane-related evacuation on access to reproductive health care. Our data may be used to address potential problems in future natural disasters. Access to resources is critical in distinguishing the impact of disasters on different groups of people.2 Ways to address the harmful effects of disasters include taking measures to avoid or allay the impact of the disasters or attempt to ameliorate postdisaster situations. These have a symbiotic relationship since lessening the disaster vulnerability of disadvantaged groups simultaneously improves both pre- and postdisaster living conditions, especially if measures are taken to empower vulnerable populations to be more self-sufficient.2

For predisaster preparation, several new studies have called for new emergency response models33 that more specifically serve the needs of diverse groups. With regards to contraception, perhaps family planning clinics can provide education and more mobile forms of birth control, such as condoms, to be added to people's disaster emergency packs.

For postdisaster response, our findings suggest a community-based disaster model that takes women's reproductive needs into account (see also Pan American Health Association7 and Richter and Flowers16) such as access to and education on various forms of birth control. This access and education may have to be provided to women (e.g., brought to shelters or have mobile clinics) rather than expecting women to come to a family planning clinic. This planning may be better accomplished by including more women and disaster survivors in disaster response preparation, implementation, and evaluation34 at the city, state, and national levels to focus on relief and rebuilding efforts.2

Debate exists about whether disasters and responses to them produce long-term change or merely accelerate or decelerate preexisting trends. The amount of potential change depends not only on the unit of analysis (individuals versus structures),35 but also upon the abilities of those in influential positions. There are those who are aware of their powerful positions and do not want to change the status quo. There are, however, many more who have some ability to change existing inequality yet lack the knowledge of the situations at hand or the knowledge of how to make change.2 Our findings are geared to an audience of public and urban planners, politicians, social scientists, and medical and insurance providers, in hopes of making appropriate changes before the next natural disaster.

Acknowledgments

Federal support for this study was provided by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) as follows: Dr. Berenson, under a midcareer investigator award in patient-oriented research (K24HD043659), and Dr. Leyser-Whalen, as an National Research Service Award postdoctoral fellow under an institutional training grant (T32HD055163). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Elliott JR. Pais J. Race, class, and Hurricane Katrina: social differences in human responses to disaster. Soc Sci Res. 2006;35:295–321. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaikie P. Cannon T. Davis I. Wisner B. At Risk: Natural Hazards, People's Vulnerability, and Disasters. New York: Routledge; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belkhir JA. Charlemaine C. Race, gender and class lessons from Hurricane Katrina. Race, Gender & Class. 2007;14:120–152. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butterbaugh L. Why did Hurricane Katrina hit women so hard? Off Our Backs. 2005;35:17–19. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cordero JF. The epidemiology of disasters and adverse reproductive outcomes: lessons learned. Environ Health Perspect. 1993;101(Suppl 2):131–136. doi: 10.1289/ehp.93101s2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hines RI. Natural disasters and gender inequalities: the 2004 tsunami and the case of India. Race, Gender & Class. 2007;14:60–68. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan American Health Organization. Program on women, health, and development of the Pan American Health Organization: gender and natural disasters fact sheet. http://www.paho.org/English/DPM/GPP/GH/genderdisasters.pdf. [Aug 18;2010 ]. http://www.paho.org/English/DPM/GPP/GH/genderdisasters.pdf

- 8.Peacock WG. Morrow BH. Gladwin H. Hurricane Andrew: Ethnicity, Gender and the Sociology of Disasters. New York: Routledge; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pittaway E. Bartolomei L. Rees S. Neglected issues and voices. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2007;19 doi: 10.1177/101053950701901S11. Spec No 69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seager J. Noticing gender (or not) in disasters. Social Policy. 2005/2006;36:29–30. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Gender and Health in Disasters 2002. http://www.who.int/gender/other_health/en/genderdisasters.pdf. [Aug 18;2010 ]. http://www.who.int/gender/other_health/en/genderdisasters.pdf

- 12.Barnshaw J. Trainor J. Race, class, and capital amidst the Hurricane Katrina diaspora. In: Brunsma DL, editor; Overfelt D, editor; Picou JS, editor. The Sociology of Katrina: Perspectives on a Modern Catastrophe. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; 2007. pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neumayer E. Plümper T. The gendered nature of natural disasters: the impact of catastrophic events on the gender gap in life expectancy, 1981–2002. Ann Assoc Am Geographers. 2007;97:551–556. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rivers JPW. Women and children last: an essay on sex discrimination in disasters. Disasters. 1982;6:256–267. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin CYC. Instability, investment, disasters, and demography: natural disasters and fertility in Italy (1820–1962) and Japan (1671–1965) Pop Env. 2010;31:255–281. doi: 10.1007/s11111-010-0103-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richter R. Flowers T. Gendered dimensions of disaster care: critical distinctions in female psycholsocial needs, triage, pain assessment, and care. Am J Disaster Med. 2008;3:31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weissman A. Siegler E. Neiger R. Jakobi P. Zimmer EZ. The influence of increased seismic activity on pregnancy outcome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1989;31:233–236. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(89)90158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Impact of the environment on reproductive health. Prog Hum Reprod Res. 1991;20:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kissinger P. Schmidt N. Sanders C. Liddon N. The effect of the Hurricane Katrina disaster on sexual behavior and access to reproductive care for young women in New Orleans. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:883–886. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318074c5f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu S. Han J. Xiao D. Ma C. Chen B. A report on the reproductive health of women after the massive 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2010;108:161–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stockemer D. Gender inequalities and Hurricane Katrina. Int J Divers Org Commun Nations. 2006;6:137–142. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berg R. Tropical Cyclone Report Hurricane Ike (AL092008) 1–14 September 2008, 23 January 2009. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-AL092008_Ike_3May10.pdf. [Aug 30;2010 ]. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-AL092008_Ike_3May10.pdf

- 23.Dorrell O. Hundreds of thousands flee as Ike roars toward Texas. USA Today, September 14, 2008. http://www.usatoday.com/weather/hurricane/2008-09-11-hurricane-ike-texas_N.htm?csp=34. [May 26;2011 ]. http://www.usatoday.com/weather/hurricane/2008-09-11-hurricane-ike-texas_N.htm?csp=34

- 24.Witt H. Galveston, Texas, still struggling to recover, rebuild after hurricane. Chicago Tribune, February 16, 2009. http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/chi-galveston_wittfeb16,0,6649545.story. [May 26;2011 ]. http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/chi-galveston_wittfeb16,0,6649545.story

- 25.Hosmer DW., Jr Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. Second. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peacock WG. Girard C. Ethnic and racial inequalities in hurricane damage and insurance settlements. In: Peacock WG, editor; Morrow BH, editor; Gladwin H, editor. Hurricane Andrew: Ethnicity, Gender and the Sociology of Difference. New York: Routledge; 1997. pp. 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosher WD. Martinez GM. Chandra A. Abma JC. Wilson SJ. Use of contraception and use of family planning services in the United States: 1982–2002. Adv Data Vital Health Stat 2004:350:1–46. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad350.pdf. [Sep 4;2010 ]. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad350.pdf [PubMed]

- 28.Frost JJ. Henshaw SK. Sonfield A. Contraceptive needs and services: national and state data, 2008 update. Guttmacher Inst 2010:1–23. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/win/contraceptive-needs-2008.pdf. [Sep 9;2010 ]. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/win/contraceptive-needs-2008.pdf

- 29.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Reproductive Health in Refugee Situations: An Interagency Field Manual. 1999. http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/home/opendocPDFViewer.html?docid=3bc6ed6fa. [Jun 3;2011 ]. http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/home/opendocPDFViewer.html?docid=3bc6ed6fa

- 30.Roepken C. Some mainland residents are still without power. Galveston County Daily News, September 22, 2008. http://galvestondailynews.com/story/126004/ [Sep 15;2010 ]. http://galvestondailynews.com/story/126004/

- 31.Rodgers JL. St. John CA. Coleman R. Did fertility go up after the Oklahoma City bombing? An analysis of births in metropolitan counties in Oklahoma, 1990–1999. Demography. 2005;42:675–692. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westoff CF. Coital frequency and contraception. Fam Plann Perspect. 1974;6(3):136–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Picou JS. Marshall BK. Katrina as paradigm shift: reflections on disaster research in the twenty-first century. In: Brunsma DL, editor; Overfelt D, editor; Picou JS, editor. The Sociology of Katrina: Perspectives on a Modern Catastrophe. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; 2007. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Enarson E. Morrow BH. A gendered perspective: the voices of women. In: Peacock WG, editor; Morrow BH, editor; Gladwin H, editor. Hurricane Andrew: Ethnicity, Gender and the Sociology of Difference. New York: Routledge; 1997. pp. 116–140. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morrow BH. Peacock WG. Disasters and social change. Hurricane Andrew and the reshaping of Miami? In: Peacock WG, editor; Morrow BH, editor; Gladwin H, editor. Hurricane Andrew: Ethnicity, Gender and the Sociology of Difference. New York: Routledge; 1997. pp. 226–242. [Google Scholar]