Abstract

Long-distance transport of mRNAs is crucial in determining spatio-temporal gene expression in eukaryotes. The RNA-binding protein Rrm4 constitutes a key component of microtubule-dependent mRNA transport in filaments of Ustilago maydis. Although a number of potential target mRNAs could be identified, cellular processes that depend on Rrm4-mediated transport remain largely unknown. Here, we used differential proteomics to show that ribosomal, mitochondrial, and cell wall-remodeling proteins, including the bacterial-type endochitinase Cts1, are differentially regulated in rrm4Δ filaments. In vivo UV crosslinking and immunoprecipitation and fluorescence in situ hybridization revealed that cts1 mRNA represents a direct target of Rrm4. Filaments of cts1Δ mutants aggregate in liquid culture suggesting an altered cell surface. In wild type cells Cts1 localizes predominantly at the growth cone, whereas it accumulates at both poles in rrm4Δ filaments. The endochitinase is secreted and associates most likely with the cell wall of filaments. Secretion is drastically impaired in filaments lacking Rrm4 or conventional kinesin Kin1 as well as in filaments with disrupted microtubules. Thus, Rrm4-mediated mRNA transport appears to be essential for efficient export of active Cts1, uncovering a novel molecular link between mRNA transport and the mechanism of secretion.

Fungal filaments are highly polarized cellular structures that expand at their apical pole. A key feature of this growth mode is the polarized secretion of cell wall material and cell wall-remodeling enzymes at the hyphal tip. Macromolecular structures like the Spitzenkörper (apical body) as well as the adjacent polarisome, which contains polarity factors to organize the fungal cytoskeleton, have been implicated in this specialized growth form. The Spitzenkörper is proposed to function as a vesicle supply center (1), mediating secretion of enzymes such as chitin synthases for cell wall synthesis. Important for the function of the Spitzenkörper and thus polar growth is the continuous supply of vesicles such as chitosomes that are transported along microtubules to the region of active growth (2–4).

A well-studied model for fungal filamentous growth is the corn pathogen Ustilago maydis (5–7). Prerequisite for pathogenicity is the formation of infectious filaments that grow with a defined axis of polarity. Filaments expand at the apical growth cone and insert retraction septa at the basal pole. The septa confine the cytoplasm to the tip compartment and lead to the formation of characteristic empty sections (8). This developmental program is intimately coupled to mating of two compatible partners, which recognize each other using pheromones (9). Stimulated cells form conjugation tubes that fuse at their tips. This activates the heterodimeric homeodomain transcription factor bW/bE that is necessary and sufficient for filamentous growth. Its activity is dependent on cell fusion, because it is only functional as heterodimer with subunits derived from compatible mating partners (10).

The infectious filament penetrates the plant surface and reinitiates proliferation to form a multicellular mycelium within the plant (11, 12). Important for infection is the secretion of effector proteins that are thought, for example, to suppress defense mechanisms (13–15).

In recent years, it has been shown that post-transcriptional control is important for filament formation (16, 17). In particular, microtubule-dependent transport of mRNAs is essential for fast polar growth (18, 19). The RNA-binding protein Rrm4 is a key player in this transport process. In vivo UV-crosslinking revealed that Rrm4 binds more than 50 different mRNAs encoding cytotopically related proteins such as polarity or translation factors. RNA live imaging demonstrated that target mRNAs colocalize with Rrm4 in ribonucleoprotein particles, so-called mRNPs, that shuttle along microtubules (18).

Rrm4 contains three N-terminal RNA recognition motifs (RRMs)1 and a C-terminal MLLE domain (MademoiseLLE domain forming a defined peptide binding pocket involved in protein-protein interactions; found at the C terminus of poly[A]-binding protein PABPC, 20, 21). The latter domain is essential for the formation of shuttling particles (22). Loss of the conventional kinesin Kin1 interferes with mRNP shuttling, suggesting that active transport by molecular motors is important for function (22). Removal of the RNA-binding domain causes loss of transported mRNPs although Rrm4 is still shuttling along microtubules. Thus, Rrm4 constitutes an integral component of the main transport unit of microtubule-dependent mRNA transport (17, 18).

Loss of Rrm4 leads to impaired virulence and filamentous growth (23). A significantly increased number of filaments grow bipolar. Deletion strains fail to insert retraction septa at the basal pole resulting in the formation of shorter filaments (22; Fig. 1A). Although substantial progress has been made in elucidating the function of Rrm4 during microtubule-dependent mRNA transport, the molecular consequences of this transport process are still unclear. To identify proteins with altered abundance in rrm4Δ strains we applied differential proteomics comparing wild type and rrm4Δ filaments. We found that the amount of endochitinase Cts1 was significantly increased. Consistently, we could show that cts1 mRNA is a direct target of Rrm4 and that secretion of Cts1 is almost abolished in the absence of Rrm4. Thus, posttranscriptional control at the level of mRNA transport is crucial for secretion of this cell wall-remodeling enzyme.

Fig. 1.

DIGE identified ten protein variants with altered amounts in the absence of Rrm4. A, rrm4Δ strains are disturbed in filamentous growth. DIC (differential interference contrast) images and fluorescence micrographs detecting Gfp of AB33rrm4G and AB33rrm4Δ filaments are shown. Black arrowheads indicate retraction septa, white arrowheads depict Rrm4-containing particles. Growth cones are marked with asterisks (size bar = 10 μm). B, Cy2 image of a representative DIGE gel showing the internal standard of membrane-associated proteins derived from AB33 and AB33rrm4Δ filaments (size marker on the left, pH range at the top). Ten protein variants exhibiting at least 2.5-fold differences in protein amounts are indicated by numbered arrowheads. Given below are enlarged Cy5 (left) and Cy3 (right) images of the same gel visualizing spots 2, 4, and 6 in protein samples from AB33 and AB33rrm4Δ filaments, respectively. C, The three panels show graphical representations of the standardized logarithmic protein abundances for spots 2, 4, and 6 obtained from three biological replicates. The internal standard (circle) is set to 0 (rectangle, wild type replicates; triangle, rrm4Δ replicates).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and Growth Conditions

Escherichia coli K-12 derivates DH5α (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Top10 (Invitrogen) were used for cloning. Growth conditions for U. maydis strains and source of antibiotics are described elsewhere (23, 24). U. maydis strains were constructed by transformation of progenitor strains with linearized plasmids (supplemental Table S1). Homologous integration events at the cts1 and rrm4 locus were verified by Southern blot analysis (24). Filamentous growth of AB33 derivates for 8 h was induced by shifting cells of an exponential growing culture (OD600 = 0.5) from liquid complete medium to nitrate minimal medium each supplemented with 1% glucose. Cells were incubated at 28 °C shaking with 200 r.p.m.

Plasmids

Standard molecular techniques were followed. Plasmids pCR2.1-Topo (Invitrogen) and pBluescriptSKII (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) were used as cloning vehicles. Genomic DNA of wild type strain UM521 (a1b1) was used as template for PCR amplifications unless otherwise noted. Detailed plasmid description, constructs, and oligonucleotide sequences (supplemental Table S2) are given in supplemental data. All constructs were confirmed by sequencing. Plasmid sequences are available upon request.

Microscopy and Image Processing

Microscopy was carried out as described previously. Epifluorescence was observed using filter sets for detection of Gfp (ET470/40BP, ET495LP, BP525/50), and TexasRed (HC562/40BP, HC593LP, HC624/40BP). To detect Cy3 either TexasRed or TRITC (HC543/22BP, HC562LP, HC593/40BP) filter sets were used (18).

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis was performed as described (18). Four Cy3-labeled probes complementary to gfp were used (oSL387–390, 4 pmol each; see supplemental Table S2). Peaks in the resulting fluorescence intensity graphs were identified using PIA (peak-identifying algorithm by K. Zarnack, J. König, and M. Feldbrügge to be published elsewhere). This algorithm detects all positions within the graph that surmount their local environment (to a maximum distance w to either side) by at least height h. Peak identification was performed using the parameters h = 130 and w = 8 (values were optimized for varying imaging techniques and signal intensities).

Sample Preparation for DIGE and Western Blot Analysis

Whole-cell extracts were prepared from 50 ml (OD600 = 0.5) budding cells or filaments growing for 8 h under inducing conditions. After centrifugation (860 × g for 5 min at 4 °C) cells or filaments were resuspended in 2 ml lysis buffer (100 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 8; 10 mm Tris/HCl, pH 8; 8 m urea; 2 × complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche)) frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground in a pebble mill (Retsch; shaking for 10 min, 30 times/sec). Following a second round of centrifugation (860 × g for 5 min at 4 °C), an aliquot of the supernatant was removed (total cell fraction). The supernatant of a third centrifugation step (51,590 × g for 30 min at 4 °C) constituted the soluble protein fraction. Protein yield was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). The pellet was washed twice with lysis buffer, resuspended in 800 μl membrane protein buffer (10 mm Tris acetate, pH 7.6; 1 mm Mg acetate; 0,1 mm EDTA; 8% glycerine (v/v); 0,1% TritonX-100 (v/v); 4 mm dodecyl-β-d-maltoside; 0,7 mm cholesteryl hemisuccinate; 2 × complete protease inhibitor mixture) and incubated for 5 h on a turning wheel at 4 °C. The supernatant of a fourth centrifugation step (51,590 × g for 30 min at 4 °C) represented the membrane-associated protein fraction. For Western blot experiments 20 μg of total and soluble protein fractions as well as 20 μl of the membrane-associated protein fractions were analyzed. Gfp fusion protein and α-tubulin were detected using an α-Gfp antibody (Roche; mixture of two mouse monoclonal antibodies directed against Gfp) and an α-Tub antibody (Merck4Biosciences; Anti-α-Tubulin Mouse IgG), respectively.

DIGE Analysis

Proteins were labeled with DIGE-specific Cy3, Cy2, or Cy5 according to the manufacturer's instructions (GE Healthcare) with the following modifications: 200 μl of the membrane-associated protein fraction was precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid and washed five times with acetone (−20 °C) according to published procedures (25). For the internal standard, a mixture of 600 μl was used (100 μl of each sample). Samples were resuspended in labeling buffer and tagged with the CyDyes as described (26).

Cy2-, Cy3-, and Cy5-tagged protein samples were mixed (50 μl of each sample, including 25 μl labeling buffer with labeled probe and 25 μl 2 × lysis buffer). DIGE sample buffer (7 m urea; 2 m thiourea; 4% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]propanesulfonate; 20 mm dithiothreitol and 0.5% IPG buffer (GE Healthcare)) was added to adjust the volume to 550 μl. Samples were applied to 24 cm Immobiline Drystrips IPG pH 3–11 (GE Healthcare). IEF (isoelectric focusing) was carried out after 12 h rehydration using an Ettan IPGphor II (GE Healthcare) at 20 °C with maximum 50 μA/strip and the following settings: gradient increase to 500 V in 4 h, continued 500 V for 4 h, gradient increase to 3500 V in 5 h followed by continued 3500 V for 13 h reaching the desired total Vh of 59,000. Subsequently, IPG strips were incubated in equilibration buffer (6 m urea; 30% (w/v) glycerol; 2% SDS; 50 mm Tris/HCl, pH 8.0) first with 0.5% dithiothreitol and then with 2% iodoacetamide each for 15 min. Strips were transferred to 10% SDS-PAGE gels (Ettan Dalt Six gel system, GE Healthcare; 1 W/gel for 2 h and 3 W/gel for 12–16 h). Images were acquired with the multifluorescent point laser scanner Typhoon 9410 (GE Healthcare) and analyzed by the image analysis software (DeCyderTM software, GE Healthcare). Only those protein spots were analyzed further that were present in all nine gels and passed standard protein filter criteria (area ≤ 200; peak height ≤ 200; volume ≤ 10,000). 94% of the ∼600 spots did not change in abundance. Applying a threshold of 2.5-fold difference in abundance, ten protein spots were detected as differentially expressed (p value < 0.01 by Student's t test; DeCyder software, GE Healthcare; Table I).

Table I. Protein variants identified by DIGE.

| Spot | Relative fold differencea | Student's t-test | Unique peptides | Sequence coverage % | Score | um numberb | Geneb | Predicted gene functionb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14.7 | 0.0005 | 4 | 37 | 70 | 04662 | rps19 | Probable RPS19B - ribosomal protein S19 |

| 2 | 5.3 | 0.0019 | 11 | 33 | 120 | 10419 | cts1 | Chitinase |

| 3 | 4.5 | 0.0047 | 3 | 5 | 40 | 00898 | afg3 | Probable AFG3 - protease of the SEC18/CDC48/PAS1 family of ATPases (AAA) |

| 4 | 4.1 | 0.0028 | 9 | 26 | 90 | 10419 | cts1 | Chitinase |

| 5 | 3.3 | 0.0047 | n. i.c | n. i. | n. i. | n. i. | n. i. | n. i. |

| 6 | 3.2 | 0.01 | 7 | 19 | 70 | 10419 | cts1 | Chitinase |

| 7 | 3 | 0.0013 | n. i. | n. i. | n. i. | n. i. | n. i. | n. i. |

| 8 | −3.1 | 0.0052 | 9 | 48 | 90 | 10548 | atp4 | Probable H+-transporting two-sector ATPase chain b precursor, mitochondrial |

| 9 | −3.6 | 0.0061 | n. i. | n. i. | n. i. | n. i. | n. i. | n. i. |

| 10 | −5.8 | 0.0007 | 4 | 37 | 50 | 11495 | nuo2 | Related to NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 21.3 kDa subunit |

Protein Identification with Liquid Chromatography (LC)-Tandem MS (MS/MS)

Total protein post staining using Deep Purple dye was applied according to the manufacturer's instructions (GE Healthcare). The spot picking list was generated with the DeCyder software (GE Healthcare) and picked automatically with an Ettan Spot Picker. Gel plugs were subjected to in-gel tryptic digest (Trypsin, Promega). Peptides were eluted and analyzed by LC-electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS/MS using an ion trap mass spectrometer (LTQ, Thermo Scientific, Hemel Hempstead, UK) with automated data-dependent acquisition. A nanoflow-HPLC system (Surveyor, Thermo Scientific) was used to deliver a flow rate of ∼250 nl/min to the mass spectrometer. Desalting was performed by using a precolumn (C18 material) in line to an analytical self-packed C18, 8-cm column (Picotip, 75 μm inner diameter, 15 μm tip; New Objective). Peptides were eluted by a gradient of 2–60% acetonitrile over 35 min. The mass spectrometer was operated in positive ion mode controlled by the Excalibur software package. It was equipped with a nanospray source and run at a capillary temperature of 200 °C; no sheath gas was used, and the source voltage and the focusing voltage were optimized for the transmission of angiotensin. Data-dependent analysis consisted of six most-abundant ions in each cycle: MS range of mass-to-charge ration (m/z) 300-2000, minimum signal 1000, normalized collision energy 30 and five repeated hits. Isolation width for MS2 analysis was 2 m/z.

Data analysis was performed using the software package BioWorks 3.2 (Thermo Scientific) with the SEQUEST protein identification algorithm using default settings (mass tolerance for parent and fragment ions was 2 and 1 amu, respectively). Fragment ion spectra were searched against the U. maydis protein database MUMDB (http://mips.gsf.de/genre/proj/ustilago/, release March 2006, 6892 predicted protein-coding genes 13; supplemental Table S3). Data analysis revealed typical contaminations (trypsin, keratin, BSA, casein, angiotensin). Search criteria included oxidation of methionine (+16) as variable modification and alkylation of cysteine (+57) as fixed modification. Furthermore, two tryptic termini and up to one missing cleavage site were allowed. Peptides with Xcorr values of 2.0, 2.3, and 3.5 for charges states 1+, 2+, and 3+, respectively, were considered identified.

UV Crosslinking and Immunoprecipitation (CLIP)

To allow high-throughput sequencing of the two independent CLIP libraries that were previously prepared for standard sequencing (18, 27), adapter regions were introduced by five cycles of re-amplification with the oligonucleotides oMFP51 or oMFP52 and oMFP3 (supplemental Table S2). In addition to the adapter regions, oMFP51 and oMFP52 introduced a 3-nt barcode (CCC and GGG, respectively) to each of the two libraries to mark them for computational separation after sequencing. Both libraries were mixed and sequenced on an Illumina GA2 flow cell.

Genomic Mapping and Analysis of CLIP Sequence Reads

The 1,290,949 and 7,594,055 sequence reads from the two CLIP libraries were mapped to the U. maydis genome (MUMDB; ftp://ftpmips.gsf.de/ustilago/Umaydis_MIPS_nuc, version April 2008) using Bowtie allowing only unique hits with no more than one mismatch and one single reportable alignment (bowtie -m 1 -v 1; 28), yielding 616,664 and 5,585,696 mapping reads originating from 1565 and 1521 unique transcript locations (referred to as CLIP tags), respectively. Combining reads from the two libraries resulted in a total of 2551 unique CLIP tags. Associated genes were identified based on current gene annotations (MUMDB; ftp://ftpmips.gsf.de/ustilago/Umaydis_chromosomal/p3_t237631_Ust_maydi2.gff3, version March 2010; 6786 annotated mRNA genes). To include 5′ and 3′ UTRs, each annotation was extended by 300 nt on either side. 1657 of the CLIP tags overlapped in sense orientation with 948 annotated genes. Three genes were omitted, because corresponding CLIP tags mapped to rRNA regions. Detailed annotation on individual genes will be published elsewhere.

Plant Infections

Plant infections of corn variety Early Golden Bantam (Olds Seeds) were performed as previously described (29). Tumor formation was scored after 12 to 14 d. The disease rating was performed using the following categories: no symptoms, chlorosis, ligula swelling, small tumors (<5 mm), large tumors (>5 mm), and wilted or dead plants.

Fluorimetric Measurements of Endochitinase Activity

Endochitinase activity was determined using the specific substrate 4-methylumbelliferyl β-d-N,N′,N″-triacetylchitotrioside (SIGMA Aldrich). Relative fluorescence units (RFUs) were determined at 25 °C with excitation and emission wavelengths of 360 nm and 450 nm (bandwidth of 7.5 nm each) using a monochromator fluorescence reader (Tecan Safire). 30 μl culture of budding cells as well as filaments induced for 8 h (OD600 = 0.5) were incubated with 70 μl/0.25 mm substrate solution for 1 h at 37 °C. For membrane permeabilization, filaments were washed with KHM buffer (110 mm potassium acetate; 20 mm HEPES; 2 mm MgCl2), and incubated for 2 min at 28 °C with different concentrations of digitonin before addition of substrate. Reactions were stopped by adding 200 μl 1 m Na2CO3. For inhibitor studies, 50 ml suspensions of filaments were incubated in the presence of 20 μm benomyl 4 h after induction of filamentation for additional 4 h. In each case, RFUs were determined in three independent experiments using the optimal gain settings (Tecan Safire, Magellan Software; gain 128, 100, 118 and 90 for data shown in Figs. 8A to 8D, respectively).

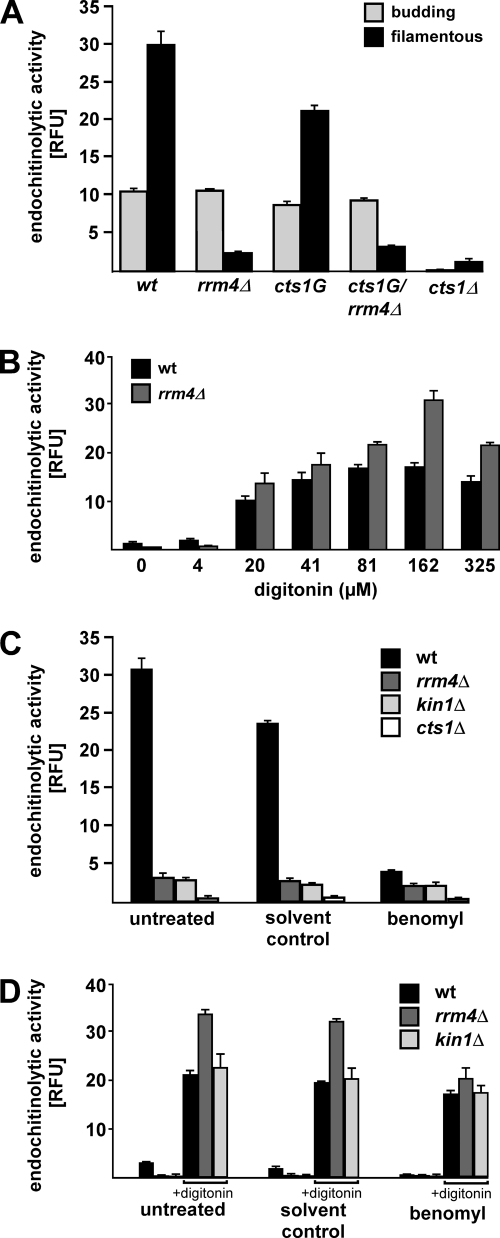

Fig. 8.

Secretion of Cts1 is impaired in rrm4Δ and kin1Δ strains. A, Bar diagram comparing endochitinolytic activity (relative fluorescence units, RFU) in budding cells and filaments (genotype is given below; error bars represent standard deviation, n = 3). B, Bar diagram comparing endochitinolytic activity of filaments of AB33 and AB33rrm4Δ in the presence of increasing concentrations of digitonin (note that fluorescence was measured with optimal gain settings, see Experimental procedures; RFU values cannot be directly compared between panels). C, Bar diagram comparing endochitinolytic activity in filaments of different AB33 derivatives (genotypes are given). Strains were either treated with solvent control or with 20 μm benomyl for 4 h. D, Bar diagram showing results from experimental setup as in (C) including additional treatment with 162 μm digitonin for membrane permeabilization as indicated below.

Molecular Phylogeny of Endochitinases

Eighty sequences of endochitinases were selected on the basis of available genome data sets. These contained 72 fungal sequences including representatives of basidiomycetes (Cryptococcus neoformans, Laccaria bicolor, Malassezia globosa, Puccinia graminis, and U. maydis) and ascomycetes (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Aspergillus fumigatus, and Hypocrea jecorina). For better comparison to previous phylogenetic analysis of chitinases, the whole repertoire of A. fumigatus (30) and H. jecorina (31) was included. The remaining eight sequences were selected from bacteria (Serratia marcescens, Vibrio fisheri, and Vibrio harveyi) and higher plants (Nicotiana tabacum and Arabidopsis thaliana). Accession numbers are given in supplemental data.

An alignment of 3890 amino acids was created using PCMA version 2.0 in default mode (32). Highly variable N- and C-terminal regions were excluded revealing an alignment of 1028 amino acids. The alignment spans the first to the last common motif of more than four amino acids in each sequence including the catalytic center. RAxML 7.0.4 (33) was used to perform a Maximum Likelihood (ML) analysis. 1000 bootstrap replicates were conducted using a rapid bootstrap algorithm (34) applying PROTCAT approximation under the BLOSUM62 amino acid model. The more accurate PROTGAMMA approximation was applied in the subsequent ML search for the best scoring ML tree starting from each fifth bootstrap tree. The alignment is available upon request.

Supplemental Data

Plasmid constructions, strains (supplemental Table S1), oligonucleotides (supplemental Table S2), LC-MS/MS data analysis (supplemental Table S3), and supplemental Fig. S1 are given in Supplemental data.

RESULTS

DIGE Identifies Ten Significant Differences Between Wild Type and rrm4Δ Strains

In order to investigate the role of Rrm4 during formation of infectious filaments we applied difference gel electrophoresis (DIGE; 26). As genetic background we chose the laboratory strain AB33, which expresses an active bW2/bE1 heterodimeric transcription factor under control of the nitrate-regulated promoter Pnar1 (35). In this strain, b-dependent filament formation is uncoupled from mating of two compatible partners. Instead, filament formation can be elicited reliably and in a synchronized form by changing the nitrogen source of the medium. The resulting filaments grow like wild-type filaments (Fig. 1A) and have been successfully used to study, for example, the transcriptional response as well as long-distance transport (18, 36, 37).

Because we observed a number of differences in preliminary experiments comparing the membrane-associated protein fraction of strains AB33 and AB33rrm4Δ, this protein fraction was subjected to DIGE analysis (see Experimental procedures). Protein extracts of three biological replicates were prepared from AB33 and AB33rrm4Δ filaments induced for 8 h. The three protein extracts of AB33 filaments were labeled with CyDye C5 using the minimal labeling technique (GE Healthcare). In order to analyze protein samples within the same gel, three protein extracts of AB33rrmΔ filaments were labeled with CyDye C3. As an internal standard that served to correct for differences because of gel-to-gel variations, all six protein samples were mixed and labeled with CyDye Cy2 (26, 38). Cy2, Cy3, and Cy5-labeled protein samples of biological replicates were coseparated in three independent two-dimensional PAGE gels (Fig. 1B). Approximately 600 protein spots were detected, corresponding to more than 10% of the estimated ∼5800 potentially detectable proteins (MUMDB, http://mips.gsf.de/genre/proj/ustilago; 1100 of the 6892 predicted proteins are outside our detection range between 20 kDa and 170 kDa). Ten protein spots were detected as differentially expressed applying a threshold of 2.5-fold difference in abundance (p value < 0.01 by Student's t test; DeCyder software, GE Healthcare). Ratios ranged from three- to 15-fold differences (Fig. 1B; Table I). In addition, these ten protein variants were identified in a fourth biological replicate performing dye-swap experiments (AB33 and AB33rrm4Δ proteins labeled with Cy3 and Cy5, respectively; data not shown).

For mass spectrometric analysis, proteins were separated by preparative two-dimensional PAGE and stained with Deep Purple (GE Healthcare). Seven differentially expressed protein variants could be assigned to five different genes, rps19, afg3, atp4, nuo2, and cts1 (Table I, supplemental Table S3). Spot 1 that exhibited a 15-fold increase in rrm4Δ filaments corresponded to ribosomal protein Rps19. Spots 3, 8, and 10 represented the mitochondrial proteins Afg3, Atp4, and Nuo2, respectively. The amount of Afg3 was increased, whereas the amounts of Atp4 and Nuo2 were decreased comparing rrm4Δ with wild type (Table I). Three protein variants (spots 2, 4, and 6) with comparable molecular weight, but different isoelectric points corresponded to um10419 annotated as chitinase (Cts1, MUMDB; see below). The amount of all three variants was increased in rrm4Δ filaments indicating that different post-translationally modified variants accumulate in the absence of Rrm4 (Fig. 1C). In essence, differential proteomics revealed that the amount of specific proteins, such as ribosomal, mitochondrial and cell wall proteins, is altered in the absence of Rrm4.

cts1G mRNA Interacts with Rrm4 In Vivo

To differentiate between direct and indirect effects of rrm4 deletion, we tested whether Rrm4 directly binds the mRNAs encoding the differentially expressed proteins. We have previously conducted CLIP (UV crosslinking and immunoprecipitation) experiments and sequenced 96 cDNA clones, which identified 61 Rrm4 target mRNAs, including rho3 and ubi1 mRNA (18). This approach, however, did not identify all mRNA targets of Rrm4 because of the restricted number of sequences that could be obtained using individual cloning and conventional sequencing. To overcome this limitation, we subjected the CLIP libraries (18) to high-throughput sequencing (39), generating a total of 1,290,949 and 7,594,055 sequence reads (see Experimental procedures). These reads were mapped to the genome allowing only unique hits with no more than one mismatch, resulting in 616,664 and 5,585,696 mapped reads that corresponded to a total of 2551 unique CLIP tags. Bioinformatic analysis revealed that CLIP tags corresponded to transcripts of 948 genes, of which 262 carried more than one unique CLIP tag (see Experimental procedures; Fig. 2A). As expected, these included ubi1 and rho3, which were identified by 39 and 6 unique CLIP tags, respectively. Of the five genes identified by DIGE, afg3, nuo2, and atp4 contained no CLIP tags. However, we identified one and two unique CLIP tags in rps19 and cts1, respectively (Fig. 2B). In both transcripts CLIP tags were located in the 3′ UTR, which was previously found as the predominant region of Rrm4 binding (18). These data indicated that cts1 and rps19 mRNAs are direct targets of Rrm4 in vivo. In the remaining study, we focused on the molecular link between Rrm4 and cts1.

Fig. 2.

CLIP experiments reveal that cts1 mRNA is directly bound by Rrm4 in vivo. A, Bar diagram summarizing the results of high-throughput sequencing of previously generated CLIP libraries (18). Labeled arrowheads indicate the presence of relevant transcripts in a given category. B, Graphic representation of the position of unique CLIP tags in target mRNAs using the following symbols for the gene structure: exons, gray rectangles; 5′and 3′UTRs (defined as 300 nt in length), bold lines; introns, thin line. Unique CLIP tags are indicated by small filled rectangles below the gene structure (note that because of space limitations, the wide black rectangle in the 3′ UTR of ubi1 represents 28 unique CLIP tags that are only few nucleotides apart).

cts1G mRNA Accumulates Preferentially in Rrm4-Dependent mRNP Particles

In order to substantiate that cts1 mRNA is a direct target of Rrm4, we assessed its subcellular localization by performing FISH (18). We generated the strain AB33cts1G expressing Cts1 C-terminally fused to the enhanced version of green fluorescence protein (Gfp, Clontech) using a SfiI-mediated homologous gene replacement system (24; see Experimental procedures). Filaments of the resulting strain did not exhibit the mutant cts1Δ phenotype (see below, Fig. 5A), indicating that the fusion protein was fully functional. gfp expressed via the constitutively active promoter Ptef served as heterologous control mRNA (AB33Ptefgfp; 40). To investigate Rrm4 dependence of cts1 mRNA localization we generated the respective rrm4Δ strains.

Fig. 5.

cts1Δ filaments aggregate in liquid culture. A, AB33 and derivatives were grown for 16 h in liquid minimal medium. B, Edge of colonies of strains AB33 and AB33cts1Δ incubated under filament-inducing conditions on minimal medium plates for 24 h. C, Results of plant infection experiments with solopathogenic strains SG200 (47) and SG200cts1Δ. The percentage of plants with typical disease symptoms is given. At least 110 plants were infected with each strain.

Analyzing this set of strains in Northern blot experiments revealed that the amount of cts1G mRNA was comparable to cts1 and the gfp control mRNA. Deletion of rrm4 had no influence on the amount of either mRNA (Fig. 3A; supplemental Fig. S1).

Fig. 3.

cts1G mRNA preferentially accumulates in Rrm4-dependent particles. A, Northern analysis comparing amounts of cts1G and gfp mRNA (indicated on the left) in filaments of strains AB33cts1G and AB33Ptef-gfp as well as respective rrm4Δ derivatives (indicated above). ppi mRNA encoding peptidyl-prolyl isomerase served as loading control. B, FISH analysis of AB33 filaments and derivatives (relevant alleles given on the left). Inverted fluorescence images (left) and fluorescence intensity graphs (right) are shown. In the latter, relative fluorescence signals were plotted along the longitudinal axis of the filament (x axis, distance from the rear pole). Detection of peaks (filled arrowheads) was performed using PIA. C, Bar diagram of mean particle numbers determined by PIA analysis of at least 67 filaments in three independent experiments (relevant genotypes labeled at the bottom; error bars, S.E., n = 3).

For FISH experiments, filaments were grown for 8 h under inducing conditions and fixed with formaldehyde. For optimal comparison, we used the same set of DNA oligonucleotide probes complementary to gfp for all strains (18). In AB33cts1G, hybridization revealed a punctuated staining of cts1G mRNA in particles throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 3B). The particles were quantified as peaks in two-dimensional line scans of more than 67 filaments using a specifically designed PIA (see Experimental procedures; 18). This analysis showed that AB33cts1G contained on average 11 particles per filament (Figs. 3B–3C). Absence of particles in AB33 verified the specificity of the probes. Moreover, cts1G mRNA particles were drastically reduced in AB33cts1G/rrm4Δ indicating that the particles were dependent on Rrm4 (Figs. 3B–3C). Consistent with other mRNA targets of Rrm4, we did not detect any subcellular accumulation or mRNA gradient, such as accumulation at the poles of filaments (Fig. 3B; 18).

Analysis of the heterologous control mRNA revealed that the amount of Rrm4-dependent particles was lower in control strain AB33Ptefgfp (Figs. 3B–3C). These results are consistent with our previous observations made with RNA live imaging. In our previous study, we showed that although all mRNAs can be found in Rrm4-dependent particles, direct targets of Rrm4 shuttle in mRNPs more often and with higher processivity (18). Because cts1G mRNA is present more frequently in Rrm4-dependent particles than a heterologous control, we conclude that this mRNA is most likely specifically recognized by Rrm4. In summary, data obtained in vivo and in situ by CLIP and FISH, respectively, are consistent with the notion that cts1 mRNA is a direct target of Rrm4-dependent mRNA transport.

cts1 Encodes a Bacterial-type Endochitinase

Sequence analysis of cts1 (um10419) using SMART (41) and MUMDB (http://mips.gsf.de/genre/proj/ustilago; 13) revealed that the gene contains a single 81 bp intron and encodes a protein of 502 amino acids (55 kDa; isoelectric point 8.2). The protein harbors a Glyco_18 domain (SMART accession number SM00636) characteristic for endochitinases of the glycoside hydrolase family 18. Therefore, the protein was annotated as endochitinase Cts1. This was supported by a BLAST analysis demonstrating a high sequence similarity to endochitinases from bacteria and fungi (Fig. 4A). Importantly, 13 amino acids that form the substrate-binding pocket and active site in ChiA (42) and CiX1 (43) from the bacterium S. marcescens and the fungus Coccidioides immitis, respectively, are conserved within Cts1. However, additional sequence motifs found in other endochitinases such as an N-terminal secretion signal, a chitin binding domain, a cellulose binding domain or a GPI-anchor attachment motif are missing (glycosyl-phosphatidyl-inositol; 31, 44, 45).

Fig. 4.

cts1 (um10419) encodes a bacterial-type chitinase of glycoside hydrolase family 18. A, Upper part, schematic drawing of Cts1 containing a Glyco_18 domain (SMART accession number SM00636) known from members of the glycoside hydrolase family 18. Amino acid positions are given above. Lower part, the sequence of the Cts1 Glyco_18 domain is aligned to sequences from fungal and bacterial chitinases CiX1 (C. immitis, 43) and ChiA (S. marcescens, 42), respectively. Identical amino acids in two or all three sequences are shaded in gray or black, respectively. Arrowheads indicate conserved amino acids which form the substrate binding pocket and the active site of CiX1 (black) and ChiA (gray) according to structural data. B, Unrooted phylogenetic tree of 80 enzymes of the glycoside hydrolase family 18. Representatives from bacteria (S. marcescens, V. fisheri, and V. harveyi; shaded in white), higher plants (N. tabacum and A. thaliana; shaded in dark gray), and fungi (ascomycetes and basidiomycetes are shaded in light gray and black, respectively) are shown. Maximum Likelihood bootstrap values (1000 replicates) are given for the main branches (asterisks indicate values above 90%). Branch lengths correspond to genetic distances. Organisms are abbreviated as follows: Sm, S. marcescens; Vf, V. fisheri; Vh, V. harveyi; Nt, N. tabacum; At, A. thaliana; Mg, M. globosa; Sc, S. cerevisiae; Sp, S. pombe; Cn, C. neoformans, Af, A. fumigatus; Hj, H. jecorina; Lb, L. bicolor; Pg, P. graminis. Accession numbers are given in Supplementary data. The three predicted endochitinases from U. maydis are indicated as UmCts1 (um10419), um06190, and um02758.

Molecular phylogeny comparing a representative selection of 80 chitinase sequences from fungi, plants, and bacteria (see Experimental procedures) showed that the glycoside hydrolase family 18 subdivides into four monophyletic clades: members of clade A are recognized as class III or bacterial-type chitinases, members of clade B are class V or plant-type chitinases and members of clade C belong to a group of high molecular weight chitinases that have recently been classified analyzing chitinases of Trichoderma reesei (syn. H. jecorina; 31). Clade D comprises basidiomycete-specific enzymes (Fig. 4B). Cts1 belongs to the bacterial-type endochitinases of clade A. The two remaining predicted endochitinases um02758 and um06190 (MUMDB) belong to clades B and D, respectively (Fig. 4B). Thus, U. maydis contains three family-18 endochitinases that belong to separate clades, suggesting very ancient gene duplication and nonredundant functions.

Loss of cts1 Causes Altered Growth in Liquid Culture

To investigate the role of Cts1 during filamentous growth, we deleted the corresponding gene in AB33 using a SfiI-mediated homologous gene replacement system (46). Measuring the chitinolytic activity of cts1Δ filaments with an endochitinase-specific substrate revealed that the enzyme activity was drastically reduced. This confirms that Cts1 functions as endochitinase (Fig. 8A, see below).

In budding cells, no phenotype of cts1Δ strains was observed indicating that the enzyme is not essential for yeast-like growth. However, cts1Δ filaments differed from wild type, because they tended to flocculate and stick to the glass surface in liquid culture (Fig. 5A). Deletion filaments formed large aggregates, in which empty sections composed of cell wall remnants stuck together more pronounced than in wild type (data not shown). However, morphology, insertion of retraction septa, and filament length were comparable to wild type on solid medium (Fig. 5B). Testing different stress conditions such as salt and osmotic stress did not reveal differences in cts1Δ strains (growth on plates in the budding and filamentous form in the presence of 50 μm calcofluor and 200 μm congo red, 2% hydrogen peroxide, 1 m sodium chloride and 1 m sorbitol; data not shown). Thus, no major defects in cell wall function were observed in the absence of Cts1.

For pathogenicity assays, we deleted cts1 in the solopathogenic strain SG200, enabling plant infection without prior mating (47). Infection of corn seedlings revealed no difference between SG200 and SG200cts1Δ indicating that the chitinase is dispensable for infection (Fig. 5C). In essence, loss of Cts1 leads to aggregation during filamentous growth in liquid culture. However, this difference does not cause major alterations in plant penetration, proliferation and tumor induction.

The Amount of Cts1 is Specifically Increased in Membrane-associated Protein Fractions

To analyze the subcellular localization of Cts1 we tested AB33cts1G and the corresponding rrm4Δ strain in Western blot experiments. Comparing whole cell extracts of budding cells and filaments revealed that the amount of Cts1G was drastically increased during filamentation (Fig. 6A, lanes 1 and 3). Comparing wild type and rrm4Δ strains showed that in the absence of Rrm4 the total amount of Cts1G was slightly elevated in budding cells and filaments (Fig. 6A, lane 1–2 and 3–4, respectively). Protein fractionation revealed that the increase of Cts1G in the rrm4Δ strain was negligible in soluble protein fractions (Fig. 6B) and in membrane-associated protein fractions of budding cells (Fig. 6C, lanes 1–2). However, in filaments the amount of Cts1G was strongly increased in the membrane-associated fraction of the rrm4Δ strain (Fig. 6C, lane 34), confirming our DIGE data. To summarize, the amount of the endochitinase Cts1 increases specifically during filamentous growth and loss of Rrm4 causes an elevated abundance of Cts1 in the membrane-associated protein fraction of filaments.

Fig. 6.

The amount of Cts1G is increased during filamentation. Western blot analysis comparing budding cells and filaments of strains AB33cts1G and AB33cts1G/rrm4Δ. Total protein extracts (A) as well as soluble (B) or membrane-associated (C) fractions were investigated. Detected proteins are given on the right (marker in kDa). Detection of α-tubulin Tub1 (in A and B) or Deep Purple (GE Healthcare) protein staining (C) served as loading controls.

Cts1G Localizes at Growth Cones and Reallocates in rrm4Δ Strains

Fluorescence microscopy detecting Gfp in the same set of strains revealed that in budding cells Cts1G was evenly distributed throughout the cytoplasm with a faint signal in the membrane (Fig. 7A). Cts1G did not accumulate at septa between mother and daughter cells consistent with the observation that there was no defect in budding (see above). In accordance with our Western blot analysis (Fig. 6A), Cts1G localization in budding cells was comparable in wild type and the rrm4Δ strain (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Cts1G accumulates at growth cones. DIC images and fluorescence micrographs detecting Gfp of AB33cts1G and AB33cts1G/rrm4Δ are shown. Budding cells (A and B) and filaments (C and D) were analyzed in the upper and lower part, respectively (genotypes are indicated inside DIC images, size bar = 10 μm). White arrowheads in DIC images and fluorescence micrographs indicate retraction septa and accumulations of Cts1G at poles, respectively. D, A bipolar (top) as well as a unipolar filament (bottom) of AB33cts1G/rrm4Δ are shown.

In filaments, Cts1G localized predominantly at membranes of growth cones (Fig. 7C). No accumulation at retraction septa was observed. In bipolar filaments of the rrm4Δ strain, Cts1G accumulated at both growing poles (Fig. 7D). In addition, it localized to the rear membrane of the initial cell in unipolarly growing filaments. These results are consistent with the increased accumulation of Cts1G in the membrane-associated protein fraction, showing that Cts1G accumulates at hyphal tips and reallocates to both poles of the filament in the absence of Rrm4.

rrm4Δ Filaments are Disturbed in Secretion of Cts1G

To answer the question whether enzyme activity is altered in the absence of Rrm4 we determined the endochitinolytic activity by using a specific fluorogenic substrate (see Experimental procedures). In preliminary experiments comparing washed cells or filaments with supernatants most of the enzyme activity was associated with cells and filaments. This finding suggests that extracellular endochitinases are attached to the outside, probably to the cell wall.

In budding cells and filaments, deletion of cts1 caused a drastic reduction in enzyme activity. Thus, Cts1 is the major endochitinase, and any redundant enzymes are likely to play only a marginal role during these stages of the life cycle. Consistent with our previous data (Figs. 6 and 7), deletion of rrm4 did not alter the enzymatic activity in budding cells (Fig. 8A, light gray bars). Measuring endochitinolytic activity in filaments revealed that enzyme activity was increased during filamentation (Fig. 8A). This is in accordance with our Western blot analysis (Fig. 6A). Surprisingly, filaments carrying a deletion in rrm4 showed a drastically decreased activity (Fig. 8A), although protein quantifications indicated a clear increase in Cts1 abundance (Figs. 1B; 6A). Hence, loss of Rrm4 could result in the formation of inactive enzyme or the disturbed secretion of active Cts1. To test these possible explanations, endochitinolytic activity was measured in the presence of increasing amounts of digitonin causing progressive membrane permeabilization and release of intracellular Cts1. Digitonin treatment caused a strong increase in endochitinase activity in wild type and rrm4Δ strains indicating that a substantial amount of active enzyme resides inside. At higher digitonin concentrations, endochitinase activity in rrm4Δ strains markedly exceeded wild type levels (Fig. 8B). Thus, in filaments, loss of Rrm4 causes intracellular accumulation of active enzyme, indicating that secretion of Cts1 is drastically impaired in the absence of Rrm4.

In order to test whether impaired Cts1 secretion is connected to the function of Rrm4 during microtubule-dependent mRNA transport, we measured endochitinolytic activity while interfering with the function of microtubules. To this end, endochitinolytic activity was tested in cells that were either treated with the microtubule inhibitor benomyl (48) or carried a deletion in kin1 (AB33kin1Δ) encoding conventional kinesin. Loss of this molecular motor results in accumulation of Rrm4-containing particles at the hyphal tips (22). We measured the endochitinolytic activity in whole filaments and showed that Cts1 activity was drastically reduced upon treatment with benomyl for 4 h. Consistently, Cts1 activity was low in kin1Δ strains (Fig. 8C). To verify that the drastic decrease of Cts1 activity in the presence of benomyl or in kin1Δ strains was because of impaired secretion of Cts1, benomyl-treated and kin1Δ filaments were incubated with 162 μm digitonin. Because of membrane permeabilization, endochitinolytic activity increased in both cases (Fig. 8D). Thus, intact microtubules, Kin1 and Rrm4 are essential for efficient secretion of Cts1. These findings are consistent with our hypothesis that microtubule-dependent mRNA transport mediated by Rrm4 promotes secretion of Cts1 in infectious filaments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we analyzed the cellular function of Rrm4, a key component of microtubule-dependent mRNA transport (17). Proteomics revealed that a ribosomal protein, three mitochondrial proteins, and an endochitinase were differentially regulated comparing wild type and rrm4Δ filaments. A more detailed analysis of endochitinase Cts1 validated our proteomic approach and demonstrated that microtubule-dependent mRNA transport is important for secretion of Cts1. Thus, we provide evidence for the first time that a secretory mechanism of an enzyme depends on mRNA transport.

Loss of Rrm4 Causes Altered Abundance of Ribosomal, Mitochondrial, and Cell Wall-Remodeling Proteins

Preliminary microarray experiments revealed that the loss of Rrm4 does not cause significant differences on the level of mRNA amounts (M. Scherer, J. Kämper, and M. Feldbrügge, unpublished data). Therefore, Rrm4 does not interfere with mRNA transcription, maturation, or stability suggesting a role in regulation of local protein expression (see below). Our differential proteomic analysis of membrane-associated protein fractions identified five differentially accumulating proteins, including the endochitinase Cts1, the ribosomal protein Rps19, and three mitochondrial proteins Nuo2, Atp4, and Afg3. Three Cts1 variants accumulated to higher extent in rrm4Δ strains. These variants differ in their isoelectric point, most likely due to post-translational modifications. Western blot as well as in vivo localization experiments with Cts1 confirmed these data (see below).

Rps19 is a ribosomal protein of the small subunit that is known to be highly phosphorylated in U. maydis (49). A bacterial homolog is missing, but mutations in the human gene are associated with 25% of cases of Diamond-Blackfan anemia. Characteristic for this hematopoietic disorder is a disturbed erythropoiesis (50, 51). The detection of a single ribosomal protein in the membrane-associated protein fraction might indicate that Rps19 exhibits an additional, membrane-associated extra-ribosomal function. This is supported by the observation that human Rps19 interacts with fibroblast growth factor 2 in vitro and that Rps19 dimers are involved in metal-induced apoptosis in animal cells (52, 53).

The three remaining mitochondrial proteins are Nuo2, Atp4, and Afg3, a subunit of NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I), a component of the Fo subunit of the mitochondrial ATP synthase (complex V), and a subunit of the m-AAA protease, respectively. The latter is thought to regulate protein quality by degrading nonassembled membrane proteins of respiratory chain complexes (54). In U. maydis, we observed a reciprocal relationship between the amount of the protease Afg3 and the amounts of potential targets Nuo2 or Atp4. In rrm4Δ filaments, the Afg3 amount is increased, whereas the amounts of Nuo2 and Atp4 are decreased (Table I). Because Afg3-type m-AAA proteases function during quality control (54), loss of Rrm4 might cause defects in the assembly of respiratory chain complexes.

According to our CLIP data, none of these mitochondrial proteins appear to be direct targets of Rrm4-mediated mRNA transport. Interestingly, conventional as well as high-throughput sequencing of our CLIP libraries revealed a number of potential mitochondrial targets of Rrm4 such as tim8, nuo1, and atp3 (a translocase of the mitochondrial inner membrane, and additional components of complex I and V, respectively; 18). Tim8 (14 kDa) and Nuo1 (9 kDa) could have been missed in our proteomic analysis because of their small size. In essence, loss of Rrm4 might cause defects in mitochondrial protein import resulting in the mis-assembly of complexes of the electron transport chain and up-regulation of Afg3.

This hypothesis is consistent with recent results from S. cerevisiae, where mRNAs encoding mitochondrial proteins localize to the vicinity of mitochondria (55, 56). The Pumilio-type RNA-binding protein Puf3p might be involved in this process (57, 58). Loss of the mitochondrial protein import component Tom20p results in a significant decrease of mRNAs associated with mitochondria. Thus, cotranslational import of certain mitochondrial proteins might depend on activity of specific RNA-binding proteins (59).

The Bacterial-type Endochitinase Cts1 is the Main Extracellular Endochitinase During Filamentous Growth

The most prominent protein identified in our DIGE approach was the endochitinase Cts1. Chitinases (EC 3.2.1.14) cleave the β-1,4-glycosidic bond between N-acetyl-d-glucosamine units of chitin, the main structural component of the cell wall in fungi and the exoskeleton of arthropods. These glycolytic enzymes exhibit diverse functions such as chitin degradation for nutritional purposes in bacteria and defense against fungal pathogens in plants (60, 61). In fungi, chitinases have been proposed to perform morphological functions during cell wall remodeling. However, in the majority of cases, definite proof of the biological function of fungal chitinases is missing. This is because of the fact that most fungi contain multiple chitinases, e.g. four, 12, and 18 in Candida albicans, A. fumigatus and T. reesei, respectively (30, 31, 45). Thus, the interpretation of data obtained by mutational analysis of individual members is hindered by a potential functional redundancy. Cts1p from S. cerevisiae and Cht3 from C. albicans belong to the few examples where a clear function could be assigned. Deletion mutants remain attached at septal sites indicating that these chitinases act specifically during cell wall degradation at the mother/daughter junction (45, 62). In filamentous fungi, deletion of chiB1 from A. fumigatus, cts1 from C. immitis, or chs1–4 from C. albicans did not reveal any mutant phenotypes during polar growth (45, 63, 64).

In U. maydis, the complete chitinolytic repertoire appears to consist of four proteins: Cts1, Um06190 and Um02758 are endochitinases of glycosyl hydrolase family 18, and Um00695 is a putative exochitinase of glycosyl hydrolase family 20. As in other fungi, members of family 19 are missing (65). According to our phylogenetic analysis, all three endochitinases belong to different ancient clades suggesting nonredundant functions.

Measuring the endochitinolytic activity in wild type and cts1Δ strains revealed that (1) Cts1 constitutes the major extracellular endochitinase, (2) enzyme activity is associated with cell walls of sporidia and filaments, and (3) Cts1 amount increases during filamentous growth. However, phenotypic analysis of cts1Δ strains showed that loss of extracellular endochitinase activity affected neither filament morphology nor the infection of corn seedlings. Thus, Cts1 is dispensable for the regulation of morphology and pathogenicity although we cannot rule out that the enzyme might be needed, e.g. during infection under harsh environmental conditions when nutrients are scarce.

It was recently reported that the chitinase ChiA in Aspergillus nidulans specifically localizes to polarized growth sites as well as septa. Subcellular accumulation was no longer detectable when a serine/threonine-rich region and a C-terminal GPI-anchor motif were missing, indicating that these regions are important for membrane localization (44). Interestingly, these motifs as well as obvious chitin-binding domains and a conventional secretion signal are absent in Cts1 from U. maydis, suggesting a potential novel binding and secretion mechanism.

The RNA-Binding Protein Rrm4 is Essential for Efficient Secretion of Cts1

Rrm4 is an integral part of the microtubule-dependent mRNP transport machinery, and mRNAs encoding, for example, polarity factors such as the small G-protein Rho3 constitute target mRNAs (17, 18). Here, we discovered a novel function for microtubule-dependent mRNA transport in fungi, namely the secretion of a cell wall-remodeling enzyme. We found that in the absence of Rrm4, export of the endochitinase Cts1 is drastically impaired in filaments, even though its general transport to the poles and its activity are not disturbed. Possible explanations could be that an associated export factor is missing or that some proteins of the Cts1 secretion machinery depend on the transport of their mRNAs (see below).

To support our hypothesis that microtubule-dependent mRNA transport is crucial for Cts1 secretion, we combined in vivo and in situ techniques to demonstrate that cts1 mRNA is a direct target of Rrm4. High-throughput sequencing of CLIP libraries (18) revealed that cts1 mRNA belongs to a distinct set of 259 transcripts that harbor at least two unique CLIP tags. As expected, this set of transcripts contains the previously identified in vivo targets ubi1 and rho3 mRNA as well as a number of novel candidates (C. Haag, J. König, J. Ule, K. Zarnack, N. M. Luscombe, and M. Feldbrügge, unpublished). Thus, Rrm4 interacts with cts1 mRNA in vivo and according to FISH experiments cts1 mRNA accumulates in Rrm4-dependent particles. The amount of particles was significantly increased in comparison to a heterologous control mRNA. This is consistent with earlier results demonstrating that Rrm4 targets are found in transport units more frequently than other mRNAs (18). Previously, we observed by RNA live imaging that generally all mRNAs can be transported along microtubules by the Rrm4-dependent transport machinery. Target mRNAs of Rrm4, however, accumulate preferentially in transport units, and the presence of a zipcode increases frequency and length of mRNP movement (17, 18). These results are in line with comparable studies in animal cells and fly embryos, demonstrating that localizing transcripts are transported along microtubules more frequently and with higher processivity than nonlocalizing transcripts (66, 67).

In accordance with our hypothesis that Rrm4 influences Cts1 secretion at the level of microtubule-dependent mRNA transport, we demonstrate that a microtubule inhibitor as well as loss of conventional Kin1 exhibits the same effect on Cts1 secretion as loss of Rrm4. Thus, local translation of cts1 mRNA might be needed to render the encoded enzyme competent for secretion. For example, cotransport and local translation of mRNAs might promote formation of secretion-competent complexes, consisting of Cts1 and associated export factor(s) (68, 69).

A molecular link between transport of mRNAs and secretion of encoded proteins has been shown in other systems studying actin as well as microtubule-dependent transport (70). In S. cerevisiae, for example, actin-dependent mRNA transport mediated by the RNA-binding protein She2p is important for mRNA localization of membrane proteins as well as polarity and secretion factors (71, 72). For instance, localization of SEC3 mRNA and accumulation of the encoded secretion factor at the daughter cell pole is impaired in the absence of She2p (72). A possible mechanism could be the myosin-mediated cotransport of cortical ER and mRNA (73). However, direct evidence that mRNA transport is crucial for secretion of the encoded proteins is currently missing.

Recently, it was shown that a critical quality control step for the formation of transport competent mRNPs is the synergistic binding of She3p, a novel RNA-binding protein, with the key RNA-binding protein She2p to RNA zipcodes. Thus, selectivity of cargo mRNAs is only achieved in concert with several factors (74). These results also support our experimental approach that in vivo UV crosslinking is currently the method of choice to verify direct mRNA binding (39, 75).

Microtubule-dependent transport of mRNAs encoding secreted proteins with critical roles during development is well-studied (76). For example, local secretion of Gurken, a TGF-α (transforming growth factor α) family protein, determines the formation of the dorsal-ventral body axis during embryonic development in Drosophila melanogaster (77). Local secretion of Gurken is mediated by microtubule-dependent transport of the corresponding mRNA during maturation of the oocyte. This is a two-step process involving first dynein-dependent transport to the anterior pole followed by active transport to the dorsal site (78). Upon anchoring of the mRNA at the anterior-dorsal corner, local translation initiates the spatially restricted secretion of Gurken involving specific trans-acting factors such as TraI (Trailer hitch) and Bicaudal-C that participate in organizing ER exit sites during classical secretion (79–81). Investigating mutants exhibiting mislocalized gurken mRNA revealed ectopic secretion, demonstrating that Gurken is still secreted at the site of translation (82, 83). Thus, correct transport of this mRNA per se is not essential for the secretory process (82).

Vg1, a secreted TGF-β family member, is another important example studied during embryonic development in Xenopus laevis. Its mRNA localizes to the vegetal hemisphere of the oocyte (84) and local secretion determines mesoderm formation after fertilization (85, 86). Secretion is most likely initiated by local translation at the vegetal ER. Further maturation of the protein that is important for its export is mediated through cleavage by the pro-protein convertase XPACE4 (87). Interestingly, XPACE4 mRNA also localizes to the vegetal pole to support local maturation (87). However, ectopic expression of Vg1 still results in some mesoderm-inducing activity at the animal pole indicating that also in this case mRNA transport is not essential for secretion (88).

In contrast, we observe that Cts1 reaches the site of secretion at the poles even in the absence of mRNA transport suggesting that mRNA transport is not needed for the protein to reach its destination. The resulting active Cts1 protein, however, whose translation has been uncoupled from mRNA transport is secretion-incompetent. Hence, in our system mRNA transport is prerequisite for secretion. The apparent difference to the observations in D. melanogaster and X. leavis might be connected to the specialized mode of secretion of Cts1. Preliminary results using a β-glucuronidase reporter system (89) revealed that Cts1 is not secreted via a conventional route including the ER and the Golgi apparatus but using an unconventional export pathway (J. Stock, K. Schipper, and M. Feldbrügge, unpublished; 90). This is consistent with the absence of a conventional secretion signal in Cts1 suggesting that export independent of the signal recognition particle is operational. mRNA transport might be essential to render the protein competent for this export pathway, for instance by ensuring co-translational association with specific export factors.

Here, we describe for the first time that the secretion of a protein depends on the microtubule-dependent mRNA transport uncovering a novel link between posttranscriptional regulation at the level of mRNA trafficking and the mechanism of secretion. Thus, in addition to long-distance transport of vesicles that are most likely involved in the activity of the Spitzenkörper (2, 91), microtubule-dependent transport of mRNAs might support secretion of distinct proteins in filamentous fungi.

Acknowledgments

We thank lab members for valuable discussion and critical reading of the manuscript. Special thanks to S. Kreibich and Dr. T. Brefort for helpful advice on Cts1 secretion. We gratefully acknowledge P. Happel for excellent technical assistance as well as T. Pohlmann and S. Baumann for help on RNA hybridization experiments. We thank Dr. J. Nyalwidhe, Dr. K. Lingelbach, J. Kahnt, and Dr. L. Søgaard-Andersen for help with mass spectrometry and DIGE infrastructure. Our research was in part financed by grants from the Max Planck Society. C.H. and J.K. were supported by fellowships of the MOI Manchot graduate school and of the long-term human frontiers science programme, respectively. We are grateful to Dr. R. Kahmann and the IMPRS for Environmental, Cellular and Molecular Microbiology from the Max-Planck-Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology in Marburg for their generous support.

Footnotes

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1 and Tables S1 to S3.

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1 and Tables S1 to S3.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- AAA

- protease ATPase associated with diverse cellular activities

- BLAST

- Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

- CLIP

- UV crosslinking and immunoprecipitation

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- DIC

- differential interference contrast

- FISH

- fluorescence in situ hybridization

- Gfp

- green fluorescence protein

- GPI

- glycosyl-phosphatidyl-inositol

- HygR

- hygromycin resistance cassette

- IPG

- immobilized pH gradient

- ML

- maximum likelihood

- MLLE

- MademoiseLLE domain

- mRNP

- ribonucleoprotein particle

- MUMDB

- MIPS Ustilago maydis Database

- NatR

- nourseothricin resistance cassette

- PIA

- peak-identifying algorithm

- ppi

- peptidyl prolyl isomerase

- RFU

- relative fluorescence units

- RRM

- RNA recognition motif

- SMART

- Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool

- TGF

- transforming growth factor

- Xcorr

- cross-correlation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gierz G., Bartnicki-Garcia S. (2001) A three-dimensional model of fungal morphogenesis based on the vesicle supply center concept. J. Theor. Biol. 208, 151–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fischer R., Zekert N., Takeshita N. (2008) Polarized growth in fungi - interplay between the cytoskeleton, positional markers and membrane domains. Mol. Microbiol. 68, 813–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harris S. D. (2006) Cell polarity in filamentous fungi: shaping the mold. Int. Rev. Cytol. 251, 41–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Steinberg G. (2007) Hyphal growth: a tale of motors, lipids, and the Spitzenkörper. Euk. Cell 6, 351–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brefort T., Doehlemann G., Mendoza-Mendoza A., Reissmann S., Djamei A., Kahmann R. (2009) Ustilago maydis as a Pathogen. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 47, 423–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Steinberg G., Perez-Martin J. (2008) Ustilago maydis, a new fungal model system for cell biology. Trends Cell Biol. 18, 61–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bölker M. (2001) Ustilago maydis - a valuable model system for the study of fungal dimorphism and virulence. Microbiology 147, 1395–1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Steinberg G., Schliwa M., Lehmler C., Bölker M., Kahmann R., McIntosh J. R. (1998) Kinesin from the plant pathogenic fungus Ustilago maydis is involved in vacuole formation and cytoplasmic migration. J. Cell Sci. 111, 2235–2246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bölker M., Urban M., Kahmann R. (1992) The a mating type locus of U. maydis specifies cell signaling components. Cell 68, 441–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kämper J., Reichmann M., Romeis T., Bölker M., Kahmann R. (1995) Multiallelic recognition: nonself-dependent dimerization of the bE and bW homeodomain proteins in Ustilago maydis. Cell 81, 73–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Feldbrügge M., Bölker M., Steinberg G., Kämper J., Kahmann R. (2006) Regulatory and structural netwoks orchestrating mating, dimorphism, cell shape, and pathogenesis in Ustilago maydis. In: Kües U., Fischer R. eds. The Mycota I, pp. 375–391, Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vollmeister E., Schipper K., Baumann S., Haag C., Pohlmann T., Stock J., Feldbrügge M. (2011) Fungal development of the plant pathogen Ustilago maydis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. DOI 10.1111/j.1574–6976.2011.00296.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kämper J., Kahmann R., Bölker M., Ma L. J., Brefort T., Saville B. J., Banuett F., Kronstad J. W., Gold S. E., Müller O., Perlin M. H., Wösten H. A., de Vries R., Ruiz-Herrera J., Reynaga-Peña C. G., Snetselaar K., McCann M., Pérez-Martín J., Feldbrügge M., Basse C. W., Steinberg G., Ibeas J. I., Holloman W., Guzman P., Farman M., Stajich J. E., Sentandreu R., González-Prieto J. M., Kennell J. C., Molina L., Schirawski J., Mendoza-Mendoza A., Greilinger D., Münch K., Rössel N., Scherer M., Vranes M., Ladendorf O., Vincon V., Fuchs U., Sandrock B., Meng S., Ho E. C., Cahill M. J., Boyce K. J., Klose J., Klosterman S. J., Deelstra H. J., Ortiz-Castellanos L., Li W., Sanchez-Alonso P., Schreier P. H., Häuser-Hahn I., Vaupel M., Koopmann E., Friedrich G., Voss H., Schlüter T., Margolis J., Platt D., Swimmer C., Gnirke A., Chen F., Vysotskaia V., Mannhaupt G., Güldener U., Münsterkötter M., Haase D., Oesterheld M., Mewes H. W., Mauceli E. W., DeCaprio D., Wade C. M., Butler J., Young S., Jaffe D. B., Calvo S., Nusbaum C., Galagan J., Birren B. W. (2006) Insights from the genome of the biotrophic fungal plant pathogen Ustilago maydis. Nature 444, 97–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Doehlemann G., van der Linde K., Assmann D., Schwammbach D., Hof A., Mohanty A., Jackson D., Kahmann R. (2009) Pep1, a secreted effector protein of Ustilago maydis, is required for successful invasion of plant cells. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schirawski J., Mannhaupt G., Münch K., Brefort T., Schipper K., Doehlemann G., Di Stasio M., Rössel N., Mendoza-Mendoza A., Pester D., Müller O., Winterberg B., Meyer E., Ghareeb H., Wollenberg T., Münsterkötter M., Wong P., Walter M., Stukenbrock E., Güldener U., Kahmann R. (2010) Pathogenicity determinants in smut fungi revealed by genome comparison. Science 330, 1546–1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feldbrügge M., Zarnack K., Vollmeister E., Baumann S., Koepke J., König J., Münsterkötter M., Mannhaupt G. (2008) The posttranscriptional machinery of Ustilago maydis. Fungal Genet. Biol. 45, S40–S46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zarnack K., Feldbrügge M. (2010) Microtubule-dependent mRNA transport in fungi. Eukaryot. Cell 9, 982–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. König J., Baumann S., Koepke J., Pohlmann T., Zarnack K., Feldbrügge M. (2009) The fungal RNA-binding protein Rrm4 mediates long-distance transport of ubi1 and rho3 mRNAs. EMBO J. 28, 1855–1866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vollmeister E., Feldbrügge M. (2010) Posttranscriptional control of growth and development in Ustilago maydis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13, 693–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kozlov G., De Crescenzo G., Lim N. S., Siddiqui N., Fantus D., Kahvejian A., Trempe J. F., Elias D., Ekiel I., Sonenberg N., O'Connor-McCourt M., Gehring K. (2004) Structural basis of ligand recognition by PABC, a highly specific peptide-binding domain found in poly(A)-binding protein and a HECT ubiquitin ligase. EMBO J. 23, 272–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kozlov G., Ménade M., Rosenauer A., Nguyen L., Gehring K. (2010) Molecular determinants of PAM2 recognition by the MLLE domain of poly(A)-binding protein. J. Mol. Biol. 397, 397–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Becht P., König J., Feldbrügge M. (2006) The RNA-binding protein Rrm4 is essential for polarity in Ustilago maydis and shuttles along microtubules. J. Cell Sci. 119, 4964–4973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Becht P., Vollmeister E., Feldbrügge M. (2005) Role for RNA-binding proteins implicated in pathogenic development of Ustilago maydis. Eukaryot. Cell 4, 121–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brachmann A., König J., Julius C., Feldbrügge M. (2004) A reverse genetic approach for generating gene replacement mutants in Ustilago maydis. Mol. Genet. Genomics 272, 216–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Görg A., Obermaier C., Boguth G., Csordas A., Diaz J. J., Madjar J. J. (1997) Very alkaline immobilized pH gradients for two-dimensional electrophoresis of ribosomal and nuclear proteins. Electrophoresis 18, 328–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Westermeier R., Scheibe B. (2008) Difference gel electrophoresis based on lys/cys tagging. Methods Mol. Biol. 424, 73–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ule J., Jensen K. B., Ruggiu M., Mele A., Ule A., Darnell R. B. (2003) CLIP identifies Nova-regulated RNA networks in the brain. Science 302, 1212–1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Langmead B., Trapnell C., Pop M., Salzberg S. L. (2009) Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10, R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brachmann A., Schirawski J., Müller P., Kahmann R. (2003) An unusual MAP kinase is required for efficient penetration of the plant surface by Ustilago maydis. EMBO J. 22, 2199–2210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Taib M., Pinney J. W., Westhead D. R., McDowall K. J., Adams D. J. (2005) Differential expression and extent of fungal/plant and fungal/bacterial chitinases of Aspergillus fumigatus. Arch. Microbiol. 184, 78–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Seidl V., Huemer B., Seiboth B., Kubicek C. P. (2005) A complete survey of Trichoderma chitinases reveals three distinct subgroups of family 18 chitinases. FEBS J. 272, 5923–5939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pei J., Sadreyev R., Grishin N. V. (2003) PCMA: fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment based on profile consistency. Bioinformatics 19, 427–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stamatakis A. (2006) RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stamatakis A., Hoover P., Rougemont J. (2008) A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML Web servers. Syst. Biol. 57, 758–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brachmann A., Weinzierl G., Kämper J., Kahmann R. (2001) Identification of genes in the bW/bE regulatory cascade in Ustilago maydis. Mol. Microbiol. 42, 1047–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Heimel K., Scherer M., Vranes M., Wahl R., Pothiratana C., Schuler D., Vincon V., Finkernagel F., Flor-Parra I., Kämper J. (2010) The transcription factor Rbf1 is the master regulator for b-mating type controlled pathogenic development in Ustilago maydis. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schuster M., Kilaru S., Ashwin P., Lin C., Severs N. J., Steinberg G. (2011) Controlled and stochastic retention concentrates dynein at microtubule ends to keep endosomes on track. EMBO J. 30, 652–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gade D., Thiermann J., Markowsky D., Rabus R. (2003) Evaluation of two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis for protein profiling. Soluble proteins of the marine bacterium Pirellula sp. strain 1. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 5, 240–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Licatalosi D. D., Mele A., Fak J. J., Ule J., Kayikci M., Chi S. W., Clark T. A., Schweitzer A. C., Blume J. E., Wang X., Darnell J. C., Darnell R. B. (2008) HITS-CLIP yields genome-wide insights into brain alternative RNA processing. Nature 456, 464–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Spellig T., Bottin A., Kahmann R. (1996) Green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a new vital marker in the phytopathogenic fungus Ustilago maydis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 252, 503–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Letunic I., Copley R. R., Schmidt S., Ciccarelli F. D., Doerks T., Schultz J., Ponting C. P., Bork P. (2004) SMART 4.0: towards genomic data integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D142–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Perrakis A., Tews I., Dauter Z., Oppenheim A. B., Chet I., Wilson K. S., Vorgias C. E. (1994) Crystal structure of a bacterial chitinase at 2.3 A resolution. Structure 2, 1169–1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hollis T., Monzingo A. F., Bortone K., Ernst S., Cox R., Robertus J. D. (2000) The X-ray structure of a chitinase from the pathogenic fungus Coccidioides immitis. Protein Sci. 9, 544–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yamazaki H., Tanaka A., Kaneko J., Ohta A., Horiuchi H. (2008) Aspergillus nidulans ChiA is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored chitinase specifically localized at polarized growth sites. Fungal Genet. Biol. 45, 963–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dünkler A., Walther A., Specht C. A., Wendland J. (2005) Candida albicans CHT3 encodes the functional homolog of the Cts1 chitinase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Fungal Genet. Biol. 42, 935–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kämper J. (2004) A PCR-based system for highly efficient generation of gene replacement mutants in Ustilago maydis. Mol. Gen. Genom. 271, 103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bölker M., Genin S., Lehmler C., Kahmann R. (1995) Genetic regulation of mating, and dimorphism in Ustilago maydis. Can. J. Bot. 73, 320–325 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fuchs U., Manns I., Steinberg G. (2005) Microtubules are dispensable for the initial pathogenic development but required for long-distance hyphal growth in the corn smut fungus Ustilago maydis. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 2746–2758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Böhmer M., Colby T., Böhmer C., Bräutigam A., Schmidt J., Bölker M. (2007) Proteomic analysis of dimorphic transition in the phytopathogenic fungus Ustilago maydis. Proteomics 7, 675–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gregory L. A., Aguissa-Touré A. H., Pinaud N., Legrand P., Gleizes P. E., Fribourg S. (2007) Molecular basis of Diamond-Blackfan anemia: structure and function analysis of RPS19. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 5913–5921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ellis S. R., Gleizes P. E. (2011) Diamond blackfan anemia: ribosomal proteins going rogue. Semin. Hematol. 48, 89–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Soulet F., Al Saati T., Roga S., Amalric F., Bouche G. (2001) Fibroblast growth factor-2 interacts with free ribosomal protein S19. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 289, 591–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nishiura H., Tanase S., Shibuya Y., Futa N., Sakamoto T., Higginbottom A., Monk P., Zwirner J., Yamamoto T. (2005) S19 ribosomal protein dimer augments metal-induced apoptosis in a mouse fibroblastic cell line by ligation of the C5a receptor. J. Cell Biochem. 94, 540–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tatsuta T., Langer T. (2008) Quality control of mitochondria: protection against neurodegeneration and ageing. EMBO J. 27, 306–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Margeot A., Garcia M., Wang W., Tetaud E., di Rago J. P., Jacq C. (2005) Why are many mRNAs translated to the vicinity of mitochondria: a role in protein complex assembly? Gene 354, 64–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Garcia M., Darzacq X., Delaveau T., Jourdren L., Singer R. H., Jacq C. (2007) Mitochondria-associated yeast mRNAs and the biogenesis of molecular complexes. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 362–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Garcia-Rodriguez L. J., Gay A. C., Pon L. A. (2007) Puf3p, a Pumilio family RNA binding protein, localizes to mitochondria and regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and motility in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 176, 197–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Saint-Georges Y., Garcia M., Delaveau T., Jourdren L., Le Crom S., Lemoine S., Tanty V., Devaux F., Jacq C. (2008) Yeast mitochondrial biogenesis: a role for the PUF RNA-binding protein Puf3p in mRNA localization. PLoS One 3, e2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Eliyahu E., Pnueli L., Melamed D., Scherrer T., Gerber A. P., Pines O., Rapaport D., Arava Y. (2010) Tom20 mediates localization of mRNAs to mitochondria in a translation-dependent manner. Mol. Cell Biol. 30, 284–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lesage G., Bussey H. (2006) Cell wall assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70, 317–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Adams D. J. (2004) Fungal cell wall chitinases and glucanases. Microbiology 150, 2029–2035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kuranda M. J., Robbins P. W. (1991) Chitinase is required for cell separation during growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 19758–19767 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jaques A. K., Fukamizo T., Hall D., Barton R. C., Escott G. M., Parkinson T., Hitchcock C. A., Adams D. J. (2003) Disruption of the gene encoding the ChiB1 chitinase of Aspergillus fumigatus and characterization of a recombinant gene product. Microbiology 149, 2931–2939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Reichard U., Hung C. Y., Thomas P. W., Cole G. T. (2000) Disruption of the gene which encodes a serodiagnostic antigen and chitinase of the human fungal pathogen Coccidioides immitis. Infect. Immun. 68, 5830–5838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Henrissat B., Bairoch A. (1993) New families in the classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem. J. 293, 781–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fusco D., Accornero N., Lavoie B., Shenoy S. M., Blanchard J. M., Singer R. H., Bertrand E. (2003) Single mRNA molecules demonstrate probabilistic movement in living mammalian cells. Curr. Biol. 13, 161–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bullock S. L., Nicol A., Gross S. P., Zicha D. (2006) Guidance of bidirectional motor complexes by mRNA cargoes through control of dynein number and activity. Curr. Biol. 16, 1447–1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]