Abstract

Spectral library searching is an emerging approach in peptide identifications from tandem mass spectra, a critical step in proteomic data analysis. Conceptually, the premise of this approach is that the tandem MS fragmentation pattern of a peptide under some fixed conditions is a reproducible fingerprint of that peptide, such that unknown spectra acquired under the same conditions can be identified by spectral matching. In actual practice, a spectral library is first meticulously compiled from a large collection of previously observed and identified tandem MS spectra, usually obtained from shotgun proteomics experiments of complex mixtures. Then, a query spectrum is then identified by spectral matching using recently developed spectral search engines. This review discusses the basic principles of the two pillars of this approach: spectral library construction, and spectral library searching. An overview of the software tools available for these two tasks, as well as a high-level description of the underlying algorithms, will be given. Finally, several new methods that utilize spectral libraries for peptide identification in ways other than straightforward spectral matching will also be described.

In the past decade and a half, mass spectrometry-based proteomics has witnessed breathtaking advances. Today, many top research universities and institutes are equipped with proteomics facilities, and the ability to detect and quantify a large number of proteins in a high-throughput manner is having a positive and growing impact in life science research. Among the many proposed experimental workflows, the most widely practiced method is probably the “bottom-up” approach of shotgun proteomics. The key steps of this approach are: (1) proteins are digested into shorter peptides that are more amenable to liquid chromatography (LC)-MS analysis, (2) peptides are further fragmented by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS)1 to yield characteristic fragmentation patterns, and (3) the MS/MS spectra are assigned to their originating peptides by various computational methods (1–4).

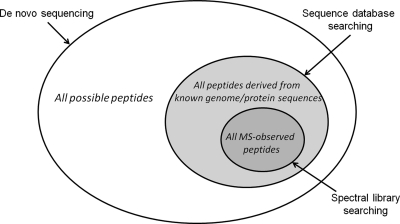

This last step of assigning MS/MS spectra to their peptide identifications is often the rate-limiting step of the whole proteomics experiment, and has received well-deserved attention over the past decade. These computational methods can be generally classified into three groups, in terms of the “search space,” i.e. the set of candidate sequences to consider as possible answers (Fig. 1). On one end of the search space scale are de novo sequencing methods (5–8), which made no initial assumption on what peptides might be present in the sample. Instead the algorithms consider exhaustively all permutations of the 20 amino acids as viable candidates, and try to infer the sequence directly from the MS/MS spectra. In the middle of the search space scale are sequence database searching methods (9–13), which rely on available sequence databases to limit the search space to only peptides that are derivable from known protein sequences. In these methods, each candidate peptide sequence is mapped to a list of expected fragment ions based on some simple rules of peptide fragmentation, to which the query (unknown) spectrum is compared. Aided by the rapid advances in genome sequencing and gene prediction that produces protein sequence databases for many model organisms, sequence database searching has become the method of choice for most proteomics researchers, despite its great demand for computational power. Toward the other end of the search space scale is spectral library searching (14–17). In spectral library searching, the search space is further restricted to only those peptides that have been previously detected and identified, and for which their fragmentation patterns have been experimentally recorded and compiled into spectral libraries. Spectral library searching is essentially a straightforward spectral matching exercise, and can be orders-of-magnitude faster than the other approaches because of its much reduced search space. This latter approach is the subject of this review.

Fig. 1.

The search space of the three classes of peptide identification methods.

Spectral library searching is relatively new in proteomics, but has a long history in the mass spectrometric analysis of small molecules. The widely used NIST/NIH/EPA mass spectral library (http://www.nist.gov/srd/nist1a.cfm), developed by the National Institute of Science of Technology (NIST), contains over 200,000 mass spectra of mostly small organic molecules (18–20). It was only in 1999, however, that the concept of spectral library searching was introduced to proteomics, in the work of Yates et al. (14), which demonstrated that peptide MS/MS spectra are reproducible enough for this approach to be effective. However, at the time mass spectrometers were slow, proteomics data was scarce, and automatic data analysis methods were in their infancy. There was no conceivable way to build comprehensive spectral libraries for use in spectral searching. As a result, this elegant idea failed to catch on until 2006, when several groups published spectral searching methods: X!Hunter (15) and Bibliospec (16) almost simultaneously, and SpectraST (17) a few months later. By then, the technological platform of shotgun proteomics and sequence searching methods had become more mature and widely used, leading to the rapid accumulation of MS/MS data. NIST began in 2006 to extend their mass spectral library to include peptides, and that effort continues in earnest today. At this moment, nearly 1 million reference spectra of peptides in 18 libraries of different organisms and biological samples have been compiled and made freely available as the NIST Libraries of Peptide Tandem Mass Spectra (http://peptide.nist.gov/).

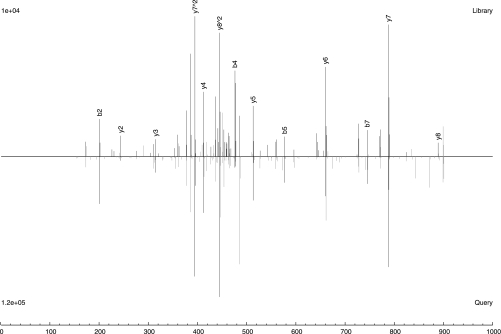

Conceptually, the premise of spectral library searching is very simple: that the fragmentation pattern of a molecule under some fixed conditions is a reproducible fingerprint of that molecule, such that unknown spectra acquired under the same conditions can be identified by spectral matching. Granted, it is true that in practice, spectra will inevitably contain experimental artifacts (e.g. random noise and signals from contaminants), or the fragmentation conditions might not be exactly the same. But very much like fingerprinting in forensic science, imperfect matches do not necessarily preclude correct identification, because the fingerprint typically contains far more information than is necessary to distinguish a significant match from a spurious one. In fact, in spectral library searching, all the features of a reference spectrum, including peak intensities and the presence of minor ions, are used, and similarity is more globally and precisely determined (Fig. 2). This is in contrast to sequence searching, which usually assumes nothing about peak intensities and ignores all noncanonical ions, primarily because of the difficulty in predicting these features for each candidate peptide in a sequence-specific manner.

Fig. 2.

An example of peptide identification by spectral searching. The top spectrum is the consensus library spectrum of the peptide ion VTQM[147]TPAPK (+2). The bottom spectrum (upside down) is a query spectrum identified confidently by SpectraST. Note how spectral searching makes use of the reproducibility of peak intensities and non-b, y ions for a more global and precise similarity scoring, allowing it to tolerate occasional unmatched features.

The effectiveness of this approach depends on (1) high-quality reference spectra, with good signal-to-noise ratios and devoid of impurities, and (2) effective matching algorithms with the robustness and flexibility to accommodate imperfect matches while minimizing false matches. The former is about constructing spectral libraries, and the latter, searching them. In the following sections, these two pillars of spectral library searching will be discussed in detail, and the progress made in the field over the past 5 years will be reviewed.

Spectral Library Construction

Spectral libraries are nothing more than searchable collections of identified spectra. Nonetheless, the conceptual simplicity of this idea belies the complexity of the actual library building process for proteomics applications. The unique difficulty of proteomics is the enormous variety of naturally occurring peptides, which makes it impractical to synthesize purified peptides to generate reference mass spectra for the entire proteome. Instead, the practical approach is to collect spectra from complex mixtures, such as bodily fluids and cell lysates, in typical shotgun proteomics experiments, and identify them by sequence database searching. Library building, therefore, must first start from the tedious and often error-prone procedure of assigning MS/MS spectra to peptide identifications, and must cope with all the well-known pitfalls and limitations of this process.

Nonetheless, for most researchers who are interested in adopting spectral library searching in their data analysis, it suffices to know that there are already high-quality and free-of-charge spectral libraries for proteomics applications that one can download with a click of a button. Since 2006, there have been centralized efforts to build peptide MS/MS spectral libraries, most notably by NIST and also by others (15, 16, 21). These endeavors seek to collect data from many laboratories and a wide variety of instrument platforms, so as to maximize the coverage and quality of the libraries. In this endeavor the emerging data repositories such as PeptideAtlas (21), PRIDE (22), and Tranche (23), have played a key enabling role. The data thus collected is often pushed through state-of-the-art data analysis pipelines to get the most out of the data, and to maintain a consistent standard for identification accuracy. These methods are constantly evolving and usually involve using multiple search engines, validation by error modeling or decoy searching, as well as various postsearch quality filters. NIST, for example, uses no fewer than four different sequence search engines, as well as additional independent postsearch filters in building their spectral libraries. Currently, however, the publicly available libraries only cover a handful of model organisms, contain mostly ion-trap collision-induced dissociation (CID) spectra, and only include modified peptides with the most common amino acid modifications, such as methionine oxidation and N-terminal acetylation. (For more information please see: http://peptide.nist.gov/).

Alternatively, researchers can also build spectral libraries for their own data, especially when no suitable public spectral libraries are available for that particular biological system. It is worth noting that a custom-built spectral library is a concise summary of the individual research group's observed proteomes of interest, and building a spectral library can also be viewed as a means of data storage and organization. In the process of building a spectral library, the spectrum is reconnected with its identification, redundancy is reduced, unidentified spectra are discarded, and relevant meta-data about the observed peptides can be aggregated. The cumbersome raw data is converted to a form that can be indexed for meaningful retrieval, and through spectral library searching, past and future observations of the same peptide are automatically linked (24). Currently, the spectral search engines X!Hunter, Bibliospec, and SpectraST all provide functionalities for building spectral libraries from sequence search results, whether in separate scripts (for X!Hunter and Bibliospec) or as options integrated into the same program (for SpectraST). All three software packages provide detailed documentation and instructions, and the interested reader is referred to the respective websites of these projects for more information (Table I).

Table I. Useful websites for spectral library building and searching tools.

| NISTMS Search | Software and library download, instructions |

| • http://peptide.nist.gov/ | |

| X!Hunter | Software download |

| • ftp://ftp.thegpm.org/projects/xhunter/binaries | |

| Library download | |

| • ftp://ftp.thegpm.org/projects/xhunter/libs | |

| Instructions | |

| • http://h201.thegpm.org/docs/xhunter_system.html | |

| Web client to X!Hunter on remote server | |

| • http://xhunter.thegpm.org/ | |

| Bibliospec | Software download |

| • http://depts.washington.edu/ventures/UW_Technology/Express_Licenses/bibliospec.php | |

| Library download and instructions | |

| • http://proteome.gs.washington.edu/software/bibliospec/documentation/ | |

| SpectraST | Software download |

| • http://sourceforge.net/projects/sashimi/files/ (SpectraST is part of TPP) | |

| Library download | |

| • http://www.peptideatlas/speclib/ | |

| • http://peptide.nist.gov/ | |

| Instructions | |

| • http://tools.proteomecenter.org/wiki/index.php?title = SpectraST | |

| Web client to SpectraST on remote server | |

| • http://www.peptideatlas.org/spectrast/ |

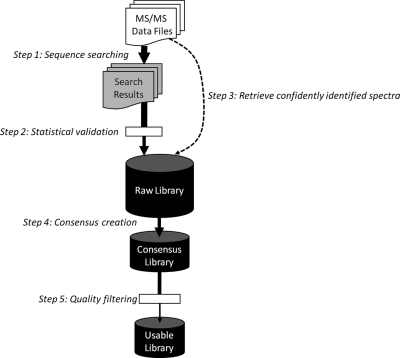

The actual process of building a spectral library from experimentally collected MS/MS spectra can be roughly divided into 5 steps (Fig. 3). First, the spectra are analyzed by traditional peptide identification tools, most commonly sequence search engines. Second, some form of statistical validation is performed to screen for confident identifications, according to some predefined standard for identification accuracy. Third, the spectra and their respective identifications must be retrieved from various files and linked together, and entries from as many data sets as possible are combined. This includes the mundane but tedious task of integrating data and search results from different locations and different formats. Fourth, once the “raw” library is built, spectra assigned to the same peptide ion identification (termed replicates) are merged to produce a single, representative “consensus” spectrum for that peptide, thereby reducing redundancy and improving search speed. An alternative and simpler approach is to select the “best” replicate among all to represent the peptide ion. The fifth and final step is quality control. This refers to the process by which incorrectly identified or noisy spectra are selectively removed from the library.

Fig. 3.

The prototypical procedure of spectral library building, starting from experimental MS/MS spectra and resulting in a usable spectral library.

The last two steps deserve some elaboration, as their importance is often overlooked. The step of consensus creation, beyond its obvious role in reducing redundancy, actually has a large impact on the effectiveness of subsequent spectral searching. A good consensus algorithm increases the signal-to-noise ratio of the resulting consensus spectrum, by taking advantage of the fact that noise, by definition, does not appear consistently across replicates, but signals should be conserved. Thus consensus spectrum creation is somewhat analogous to the practice of taking multiple measurements of a physical quantity, and reporting an average that evens out noisy fluctuations of individual measurements. It has been shown that the consensus approach is better than the “best-replicate” approach for reducing redundancy, and that the more replicates that go into forming the consensus, the higher the signal-to-noise ratio of the consensus is, up to a certain saturation limit (24). In terms of actual implementation, the consensus algorithm must also deal effectively with cases where replicates are too dissimilar to each other (perhaps because of ineffective fragmentation, contamination, or false identification in some replicates), and where some replicates are much more noisy than others. To achieve some robustness against the wide variety of spectra that it might encounter, SpectraST (which implements a similar algorithm as NIST's) attempts to detect problematic replicates and remove them before merging, and weighs the replicates by quality rather than taking a straight average. It also employs a “peak voting” method whereby only peaks consistently present in a majority of replicates are admitted into the consensus, further reducing the chance of retaining noise or impurity peaks. For peptide ions that are only observed once, the consensus approach is unavailable, but some spectrum cleaning steps can still be taken to reduce noise, before such “singleton” spectra are admitted into the spectral library.

The consensus spectral library generated in this manner may still have occasional bad apples that need to be thrown out to ensure the eventual success of spectral searching. There are two types of spectra that are unwelcome in spectral libraries: (1) incorrectly identified spectra, and (2) extremely noisy or heavily contaminated spectra. The former are products of fallible sequence search engines, and will propagate errors in spectral searching if allowed in spectral libraries. The latter not only cause false positives because of nonspecific matches, but also lead to a higher background in similarity scores and thereby reduce the discrimination power of the search engine, again because of their propensity to form indiscriminate partial matches. It has been shown that the detection and removal of these undesirable spectra from the spectral libraries contributes to greater sensitivity of the spectral search (24). There are two major mechanisms for filtering spectra for quality control. The first is no different from ordinary statistical validation of sequence search results. Namely, one attempts to reduce false positives and bad spectra by setting appropriate thresholds on sequence search scores. In this regard, it is worth noting that library building generally involves much greater amounts of data, most of which repeated samplings of the same proteome, than typical proteomics experiments. A library builder must therefore be keenly aware of the problem of accumulating false positives as data volume increases (25). To ensure that the library does not accumulate false positives, much more conservative score cutoffs must be applied than is customary in proteomics experiments. NIST actually takes it one step further and throws away all “one-hit wonders,” i.e. peptide ions that have been identified only once among tens of millions of spectra. SpectraST implements user-defined options that can selectively remove all “one-hit wonders” or only those that cannot be confirmed by another identification (e.g. of the same sequence but a different charge state) in the library. Although it has been demonstrated that many of the “one-hit wonders” are in fact correct (25), it is not unreasonable to take an exceedingly conservative position, and sacrifice some coverage for the sake of minimizing errors in the library, especially if the library is intended for public use. Throwing away “one-hit wonders” also has the benefit of ensuring all spectra in the library are consensus spectra.

The second method of library quality control is to filter based on the properties of the spectra themselves. As mentioned before, noisy or contaminated spectra, even correctly identified ones, are undesirable in spectral libraries. In this regard, there is a rich literature on quality assessment of MS/MS spectra that a library builder can make use of (26–28). However, most quality assessment tools are intended for filtering spectra prior to searching, whereas in library quality control, the spectra are already identified. Therefore the identification can be used to help determine if the spectrum is noisy or contains a dominant impurity. SpectraST, for example, tries to annotate all peaks in a spectrum to plausible fragment ions of the peptide, considering a wide range of possibilities including uncommon neutral losses. Then a filter can be set such that any spectrum containing too many unexplained peaks or too high a fraction of unexplained signals will be removed.

Lastly, for a library to be useful as a living resource, various meta-data about the library spectra should also be stored. This includes information about the sample sources, the search engines used to identify them, and measures of confidence for the identification. For large libraries built from many data sets, this information need to be aggregated and summarized meaningfully as replicates from different sources are merged. The measure of confidence is also important as a means to convey uncertainty about the spectrum's identification, such that the spectral search engine can take this into account as it assigns confidence to an identification made by spectral matching (17).

Spectral Library Searching

Several spectral search engines designed for proteomics applications have been developed in the past 5 years. In this section the focus is on the traditional, more well-established tools that perform straightforward spectral matching; newer methods that use libraries for peptide identification in some other ways are discussed in a later section. The intention here is to first briefly describe each engine in terms of their defining features, and then conceptualize the common steps and algorithmic framework of spectral searching exemplified in these methods. For a more in-depth discussion on the usability and surrounding informatics support of these tools, the reader is referred to Ref (30).

As mentioned, there is a long tradition of using spectral library searching for identification of small molecules from mass spectra. NIST MS Search (19) is a search engine originally developed for that purpose, and has since been modified to support peptide identification with the release of the NIST peptide mass spectral libraries. A stripped-down, command-line version, MSPepSearch, is now available, which can be more easily adapted to high-throughput data analysis pipelines.

X!Hunter (15) is a close cousin to the popular open-source sequence database search engine X!Tandem (11), developed at the Global Proteome Machine (31). This open-source program was designed to work with GPM's own downloadable spectral libraries. X!Hunter share the same informatics infrastructure and statistical models as X!Tandem, so X!Tandem users should be able to adopt X!Hunter in their data analysis pipeline without a steep learning curve.

Bibliospec (16) was developed by the MacCoss group at the University of Washington. The program is available freely for academic use, but is not open-source. Bibliospec also comes with its own spectral libraries built by the “best-replicate,” rather than the consensus, approach. Bibliospec implements multiple ways of spectrum filtering and similarity scoring, including the sophisticated cross correlation function of SEQUEST.

SpectraST (17, 24) was initially developed in collaboration between the Institute for Systems Biology (ISB) and NIST, as a search engine for NIST's nascent peptide mass spectral libraries. As such, the library file formats and the algorithmic details of SpectraST have a lot in common with NIST MS Search, but the two search engines are not identical. SpectraST is integrated with the Trans Proteomic Pipeline (TPP) software suite (32), which provides the supporting functionalities necessary in a full proteomic data analysis pipeline, from data format conversion to statistic validation and protein inference.

Algorithmically, the key component of any spectral library searching method is a scoring function that numerically defines the similarity of two spectra. The aforementioned engines generally share the same approach in this regard, but differ slightly in the details, as follows. First, the entire m/z range is subdivided into a predefined number (N) of “bins,” and the peak lists are converted to an N-dimensional vector, with each of the N elements being the summed intensity within one bin. The bin width can be chosen to reflect the mass resolution of the instrument; with typical ion trap instruments a bin width of 1 Da/e is customary. This process of “binning” converts peak lists of different lengths into equal-size vectors, so that they can be easily compared. The scoring function then takes these vectors as input, and computes a quantity that reflects how similar the two vectors are (19, 20). It is illustrative to describe the two extremes among these similarity score functions. On one extreme is the shared peak count, i.e. the number of peaks that are found in both of the spectra to be compared, divided by some normalization factor. This function does not take into account of the peak intensity at all, which somewhat defeats the purpose of spectral library searching. In fact, this scoring function is commonly used in sequence search engines, for which the peak intensity is not readily predictable from the sequence. On the other extreme is the dot product, which simply measures the cosine of the angle subtended by the two vectors in N-dimensional space. (A dot product of one indicates identical vectors, whereas a dot product of zero indicates orthogonal vectors.) A matching peak that is twice as large will count 4 times as much in the dot product, as the matching intensities from either spectrum are multiplied. As such, the dot product weighs the peak intensity heavily, and can be prone to error when there are dominating peaks or when the peak intensities have low reproducibility for some reason. A sensible approach, therefore, would be to strike a balance between these two extremes, to accommodate different spectral shapes and to anticipate some noisy fluctuations in the peak intensities. X!Hunter, for example, uses the dot product multiplied by a factor calculated from the shared peak count as the scoring function. NIST MS Search, Bibliospec and SpectraST down-scale the peak intensity (taking the square root of the intensity) before calculating the dot product. SpectraST also uses an additional score, the dot bias, to detect the cases where a high dot product score is merely because of the matching of a few dominating peaks, and apply a penalty accordingly.

In addition to the similarity scoring function, all search engines employ some form of spectrum preprocessing to reduce noise prior to spectral matching. Typical methods include arbitrary thresholding based on the absolute intensity or relative intensity, and limiting a spectrum to only a fixed number of intense peaks (in the entire spectrum or within sliding m/z windows). X!Hunter and Bibliospec, for example, retain only the top 20 peaks, and top 100 peaks, respectively. The logic behind this approach is simple: one expects that the majority of information of a reference spectrum is captured in the handful of most intense peaks, and that there should be a limited number of prominent fragment ions for any given peptide under typical fragmentation conditions. However, it has also been shown that oversimplification of spectra will hurt the discrimination power (24), and that minor ions such as fragment neutral losses indeed carry information that helps boost the sensitivity of spectral searching (33). Finally, peaks that are too close to the precursor region are often ignored because these tend to be sequence-nonspecific neutral losses of the precursor, but can sometimes overshadow the rest of the spectra in case of poor fragmentation.

As with sequence database searching, the spectral search engine considers all candidates within a certain precursor m/z window for each query spectrum, and returns the top scoring (most similar) match among the candidates. Besides the measure of spectral similarity, such as the dot product, the search engine will also provide additional scores that help establish the statistical significance of the match. Intuitively, that the top-ranked identification not only wins but wins by a large margin lends additional confidence to its being correct. Put differently, the score separation of the top-ranked identification and the rest of the candidates is a useful measure of how unlikely it is for the top-ranked identification to occur just by random chance (11, 12). For example, X!Hunter provides a X!Tandem-style E-value that is related to the probability that the match is a random event. SpectraST reports the dot product gap between the best and the second best matches. It is then up to the user to apply some cutoff on these scores to strike the desired balance between sensitivity and specificity. This last step, sometimes referred to as statistical validation, is necessary for all search methods and usually done independently of the search engine. The reader is referred to Ref (34) for an overview. Of special note is increasingly popular decoy searching method, which does not require parametric assumptions about the score distributions (35). In the context of spectral library searching, decoys take the form of library spectra that should necessarily generate wrong answers when matched, but are realistic enough to mimic the features of real spectra. Users can choose to use a spectral library of a different organism as decoys, or more generally, to create artificial decoy spectra for this purpose using the spectral search engine SpectraST (36).

Lastly, it should perhaps be noted that although these methods are tested and optimized on training data sets, there might exist scoring functions that might perform better in other situations, and research is ongoing in further improving these methods.

Other Spectral Library-based Peptide Identification Methods

Before the advent of peptide spectral libraries as we know it today, methods of clustering peptide MS/MS spectra by similarity, a process akin to spectral library searching, has been proposed to improve data analysis methods (37, 38). More recently, several groups have published methods on using spectral matching as a means to identify unexpected post-translational modifications or amino acid substitutions. The idea was first introduced as the concept of spectral network by Bandeira et al. (39). In this approach, MS/MS spectra are not searched in the traditional sense, but are rather clustered by spectral similarity, and organized in a network in which similar spectra are linked as neighbors. The premise was that spectra belonging to the same cluster must also have related identifications, and that identification of one spectrum in the cluster will enable the identification of all in the cluster. Importantly, the spectral similarity calculation allows for partial matches, such as unexpected modifications can be detected by a constant mass shift of a subset of peaks. The original work by Bandeira et al. used de novo sequencing methods to identify well-connected members of clusters. Another similar tool that exploits this idea was Bonanza (40), which essentially builds a spectral library from sequence search results and then uses it to identify more related spectra among the unidentified. The similarity scoring is modified to allow for mass-shifted peak matches that might arise because of an unexpected modification. More recently, a similar approach was implemented in the tool pMatch (41), which further allows more flexibility to match spectra with modification that might change the fragmentation pattern beyond simple mass shifts, as well as accounts for the possibility of multiply-charged fragment ions.

It has long been known that many MS/MS spectra in a typical proteomics experiment are superposition of the fragment ion spectra of multiple, co-eluting peptides. These mixture spectra are often difficult to identify by traditional methods. Wang et al. developed the tool M-SPLIT (42) that is capable of comparing a query spectrum to linear combinations of any two spectra in a spectral library. It was demonstrated that a great majority of mixture spectra can be identified, and the relative amount of the two peptides in the mixture determined, even for abundance ratio as high as 10:1. The ability to identify mixture spectra will find application in newer mass spectrometric workflows such as data independent acquisition (DIA) and MSE, which deliberately generate mixture spectra (43, 44).

It has also been proposed that spectral searching can be extended to previously unobserved peptides by using theoretically predicted spectra. This can be viewed as an intermediate between sequence and spectral searching approaches. Yen et al. (45) made use of the spectrum prediction tool, MassAnalyzer (46, 47), to generate a library of predicted spectra for all tryptic peptides in human, and used X!Hunter to search it, and obtained comparable performance as Mascot, the sequence search engine. Although this did not, in itself, argued for the use of this approach over traditional sequence searching, it was however an encouraging start, given that current spectrum prediction algorithms have much room for improvement, and that the scoring function was adapted without change from X!Hunter and not further optimized. Recently a semi-empirical approach to generate predicted spectra for peptides was also proposed, whereby instead of predicting a spectrum from the sequence directly, an existing library spectrum of a related peptide was used as a template (48). These works represent a step forward in extending the proteome coverage of existing spectral libraries and broadening the applicability of spectral library searching.

Last but not least, the emerging approach of selected reaction monitoring (SRM, also known as multiple reaction monitoring, MRM) can also be viewed as an indirect use of spectral libraries for peptide identification. The challenge of designing SRM experiments often is to determine the peptide and transitions to monitor for any given protein of interest. Peptides represented in spectral libraries are guaranteed to be ionizable and observable, and the knowledge of the MS/MS spectra makes it straightforward to select appropriate transitions. Several software tools have been developed to use spectral libraries to aid SRM assay design (49, 50), and online databases of SRM assays have also been populated from spectral libraries (51).

Future Challenges

There is no doubt that the spectral library approach in proteomics has become more generally accepted since it first appeared 5 years ago. Thanks to the effort of NIST and others, libraries are growing rapidly and getting better. Yet the libraries are so far not catching up with the advances in technology or the expanding realm of biology being investigated by proteomic methods today. Many model organisms still do not have libraries yet. Post-translational modifications remain very limited in publicly available libraries. Spectra of newer fragmentation methods, such as electron transfer dissocation, and high mass-accuracy MS/MS spectra, are still in the pipeline. It is important to note that the idea of fingerprinting by spectral matching should be general; there is no reason why the same principle cannot be applied to all these other cases, perhaps with minor modification in the algorithms. The current limitation, therefore, is mostly because of the insufficiency of data. There is an inevitable lag time between the introduction of new technologies and the point where enough data is accumulated for libraries. Of course, much work will still have to be done for the proteomics community to share data more effectively for library building, and for the library builders to learn to cope with larger and larger amount of data.

Currently, despite the availability of software tools for this purpose, the library building process still requires manual intervention every step of the way, from the collection and processing of data from the community, to the occasional manual validation of library spectra. With growing data volume, this is perhaps unsustainable in the long run. Therefore, further research in the automation of this process will be important. This likely requires a more seamless integration of spectral library building with online data repositories, more robust algorithms for quality control, and perhaps some feed-back mechanisms for users to report errors. Moreover, as libraries grow, it will become harder and harder to rebuild them from scratch as new data is added, or when peptide identification methods are improved. Libraries may need to be updated incrementally, while still maintaining a mechanism for error removal. The best strategy for library update remains to be worked out.

On the searching side, there remains ample room for improvement in the spectral search engines, in terms of the user interface, the search algorithm, speed, and surrounding informatics support. As with sequence searching, methods for spectral preprocessing and similarity scoring may be further improved and optimized for different types of spectra. One example is high mass-accuracy MS2 spectra that are increasingly generated from TOF and Orbitrap instruments. To take advantage of the mass accuracy, some minor modifications to the existing algorithms, for instance bin width adjustment, are likely required. Though they are already quite fast, spectral search engines can certainly be made even faster by parallelization or use of graphics processing units (GPUs). Finally, given the complementary nature of sequence searching and spectral searching, better methods and more user-friendly software tools to combine these two approaches without hassle should be of great value.

Lastly, despite the utilities of spectral libraries described above, there remains much to be done to bring these methods of library building and searching to the mainstream. The reality is that many new advances in computational proteomics, this one included, are slow to be adopted by most biologists, if at all. There needs to be more time and resources dedicated to the software engineering side of method development, such that great algorithms become truly useful applications. It would also help a great deal if these new methods become integrated with well-established commercial software packages, including software bundled with instruments.

Concluding Remarks

This review offers a brief overview of the software tools and underlying algorithms in building and searching spectral libraries for proteomics applications. The intention was more to inform the reader of this approach rather than to advocate on its behalf, as the advantages and limitations of this approach has already been discussed elsewhere (15–17, 30, 33). To briefly summarize, spectral library searching and sequence database searching should be considered complementary to each other, and each is more suitable to certain proteomics applications. Sequence searching is more suited to discovery-oriented experiments where identification of novel peptides or modifications is the goal, whereas spectral library searching is a more effective way to detect previously observed and identified peptides. There is recent demonstration that, given the same answers to choose from, spectral library searching is more sensitive (identifies more spectra at the same error rate) than sequence database searching (33). This seems to suggest that, as long as the peptide to be detected is in the library, spectral library searching should be the method of choice. However, one should never forget that if the peptide to be detected is not in the library, then spectral library searching will never return the right answer regardless of what algorithm it uses. (In the same way, sequence database searching is also guaranteed to fail if the right answer is not in the sequence database for some reason, or if the correct post-translational modification is not being considered.) Given the complementary nature of the two approaches, they can and should be combined, either as parallel peptide identification methods, or in tandem (52, 53). As an obvious example, sequence searching can first be applied to a reference sample to construct a reference spectral library, followed by quick and sensitive spectral searching to confirm the same identifications in subsequent experiments to detect and quantify the same set of interesting proteins under different experimental conditions. This is particularly suited for experiment involving many samples and replicates, such as clinical studies.

As a final remark, it should be obvious that the success and range of applicability of spectral library searching depends strongly on the proteome coverage of the spectral libraries. Thanks to the efforts of NIST and others, the public spectral libraries are rapidly expanding and should, in time, cover more and more proteomes of interest to the research community, though progress is still greatly hindered by the difficulty to gather raw data from individual researchers. As a matter of principle, spectral libraries should be considered a community resource not unlike sequence databases, which are now compiled and frequently updated by centralized efforts using sequence data deposited into repositories by contributors worldwide, either voluntarily or as mandated by publication or funding agency guidelines. It is conceivable, even probable, that this development in genomics will be mirrored in proteomics in the near future, with emerging proteomics data repositories playing the role of data hubs. If and when sharing of proteomics data becomes the norm, as in the case of genome sequences, one can expect that public spectral libraries will also be frequently updated to reflect the proteome collectively observed by the entire community at that point in time. This should become an enormously useful resource for all proteomics researchers, acting as the bridge between discovery-oriented proteomics and targeted proteomics.

Footnotes

* H. L. is financially supported by the Research Grant Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project No. HKUST 601909).

1 The abbreviations used are:

- MS/MS

- tandem MS

- NIST

- National Institute of Science of Technology.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aebersold R., Mann M. (2003) Mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nature 422, 198–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Domon B., Aebersold R. (2006) Mass spectrometry and protein analysis. Science 312, 212–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Washburn M. P., Wolters D., Yates J. R., 3rd (2001) Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat. Biotechnol. 19, 242–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Steen H., Mann M. (2004) The ABC's (and XYZ's) of peptide sequencing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 699–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dancik V., Addona T. A., Clauser K. R., Vath J. E., Pevzner P. A. (1999) De novo peptide sequencing via tandem mass spectrometry. J. Comput. Biol. 6, 327–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ma B., Zhang K., Hendrie C., Liang C., Li M., Doherty-Kirby A., Lajoie G. (2003) PEAKS: Powerful software for peptide de novo sequencing by tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 17, 2337–2342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Frank A., Pevzner P. (2005) PepNovo: de novo peptide sequencing via probabilistic network modeling. Anal. Chem. 77, 964–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pitzer E., Masselot A., Colinge J. (2007) Assessing peptide de novo sequencing algorithms performance on large and diverse data sets. Proteomics 7, 3051–3054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eng J. K., McCormack A. L., Yates J. R., 3rd (1994) An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 5, 976–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Perkins D. N., Pappin D. J. C., Creasy D. M., Cottrell J. S. (1999) Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence database using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis 20, 3551–3567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Craig R., Beavis R. C. (2004) TANDEM: matching proteins with tandem mass spectra. Bioinformatics 20, 1466–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Geer L. Y., Markey S. P., Kowalak J. A., Wagner L., Xu M., Maynard D. M., Yang X., Shi W., Bryant S. H. (2004) Open mass spectrometry search algorithm. J. Proteome Res. 3, 958–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. MacCoss M. J. (2005) Computational analysis of shotgun proteomics data. Cur. Opin. Chem. Biol. 9, 88–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yates J. R., 3rd, Morgan S. F., Gatlin C. L., Griffin P. R., Eng J. K. (1998) Method to compare collision-induced dissociation spectra of peptides: Potential for library searching and subtractive analysis. Anal. Chem. 70, 3557–3565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Craig R., Cortens J. C., Fenyo D., Beavis R. C. (2006) Using annotated peptide mass spectrum libraries for protein identification. J. Proteome Res. 5, 1843–1849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frewen B. E., Merrihew G. E., Wu C. C., Noble W. S., MacCoss M. J. (2006) Analysis of peptide MS/MS spectra from large-scale proteomics experiments using spectrum libraries. Anal. Chem. 78, 5678–5684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lam H., Deutsch E. W., Eddes J. S., Eng J. K., King N., Stein S. E., Aebersold R. (2007) Development and validation of a spectral library searching method for peptide identification from MS/MS. Proteomics 7, 655–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Domokos L., Hennberg D., Weimann B. (1984) Computer-aided identification of compounds by comparison of mass spectra. Anal. Chim. Acta 165, 61–74 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stein S. E., Scott D. R. (1994) Optimization and testing of mass spectral library search algorithms for compound identification. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 5, 859–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Owens K. G. (1992) Application of correlation analysis techniques to mass spectral data. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 27, 1–49 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Deutsch E. W., Lam H., Aebersold R. (2008) PeptideAtlas: a resource for target selection for emerging targeted proteomics workflows. EMPO Rep. 9, 429–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martens L., Hermjakob H., Jones P., Adamski M., Taylor C., States D., Gevaert K., Vandekerckhove J., Apweiler R. (2005) PRIDE: the proteomics identifications database. Proteomics 5, 3537–3545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hill J. A., Smith B. E., Papoulias P. G., Andrews P. C. (2010) ProteomeCommons.org collaborative annotation and project management resource integrated with the Tranche repository. J. Proteome Res. 9, 2809–2811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lam H., Deutsch E. W., Eddes J. S., Eng J. K., Stein S. E., Aebersold R. (2008) Building consensus spectral libraries for peptide identification in proteomics. Nat. Methods 5, 873–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reiter L., Claassen M., Schrimpf S. P., Jovanovic M., Schmidt A., Buhmann J. M., Hengartner M. O., Aebersold R. (2009) Protein identification false discovery rates for very large proteomics data sets generated by tandem mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 2405–2417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gupta N., Pevzner P. A. (2009) False discovery rates of protein identifications: a strike against the two-peptide rule. J. Proteome Res. 8, 4173–4181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Salmi J., Nyman T. A., Nevalainen O. S., Aittokallio T. (2009) Filtering strategies for improving protein identification in high-throughput MS/MS studies. Proteomics 9, 848–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Renard B. Y., Kirchner M., Monigatti F., Ivanov A. R., Rappsilber J., Winter D., Steen J. A., Hamprecht F. A., Steen H. (2009) When less can yield more - Computational preprocessing of MS/MS spectra for peptide identification. Proteomics 9, 4978–4984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nesvizhskii A.I., Roos F. F., Grossmann J., Vogelzang M., Eddes J. S., Gruissem W., Baginsky S., Aebersold R. (2006) Dynamic spectrum quality assessment and iterative computational analysis of shotgun proteomic data. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5, 652–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lam H., Aebersold R. (2011) Building and searching tandem mass (MS/MS) spectral libraries for peptide identification in proteomics. Methods 54, 424–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Craig R., Cortens J. P., Beavis R. C. (2004) Open source system for analyzing, validating, and storing protein identification data. J. Proteome Res. 3, 1234–1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Deutsch E. W., Mendoza L., Shteynberg D., Farrah T., Lam H., Tasman N., Sun Z., Nilsson E., Pratt B., Prazen B., Eng J. K., Martin D. B., Nesvizhskii A. I., Aebersold R. (2010) A guided tour of the Trans-Proteomic Pipeline. Proteomics 10, 1150–1159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhang X., Li Y., Shao W., Lam H. (2011) Understanding the improved sensitivity of spectral library searching over sequence database searching in proteomics data analysis. Proteomics 11, 1075–1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nesvizhskii A. I., Vitek O., Aebersold R. (2007) Analysis and validation of proteomic data generated by tandem mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods 4, 787–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Elias J. E., Gygi S. P. (2007) Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods 4, 207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lam H., Deutsch E. W., Aebersold R. (2010) Artificial decoy spectral libraries for false discovery rate estimation in spectral library searching in proteomics. J. Proteomics Res. 9, 605–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Beer I., Barnea E., Ziv T., Admon A. (2004) Improving large-scale proteomics by clustering of mass spectrometry data. Proteomics 4, 950–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tabb D. L., Thompson M. R., Khalsa-Moyers G., VerBerkmoes N. C., McDonald W. H. (2005) MS2Grouper: group assessment and synthetic replacement of duplicate proteomic tandem mass spectra. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 16, 1250–1261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bandeira N., Tsur D., Frank A., Pevzner P. A. (2007) Protein identification by spectral networks analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 6140–6145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Falkner J. A., Falkner J. W., Yocum A. K., Andrews P. C. (2008). A spectral clustering approach to MS/MS identification of post-translational modifications. J. Proteome Res. 7, 4614–4622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ye D., Fu Y., Sun R. X., Wang H. P., Yuan Z. F., Chi H., He S. M. (2010) Open MS/MS spectral library search to identify unanticipated post-translational modifications and increase spectral identification rate. Bioinformatics 26, i399–i406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang J., Pérez-Santiago J., Katz J. E., Mallick P., Bandeira N. (2010) Peptide identification from mixture tandem mass spectra. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9, 1476–1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bern M., Finney G., Hoopmann M. R., Merrihew G., Toth M. J., MacCoss M. J. (2010) Deconvolution of mixture spectra from ion-trap data-independent-acquisition tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 82, 833–841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Silva J. C., Gorenstein M. V., Li G. Z., Vissers J. P., Geromanos S. J. (2006) Absolute quantification of proteins by LCMSE. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5, 144–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yen C. Y., Meyer-Arendt K., Eichelberger B., Sun S., Houel S., Old W. M., Knight R., Ahn N. G., Hunter L. E., Resing K. A. (2009) A simulated MS/MS library for spectrum-to-spectrum searching in large scale identification of proteins. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 857–869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhang Z. (2004) Prediction of low-energy collision-induced dissociation spectra of peptides. Anal. Chem. 76, 3908–3922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang Z. (2005) Prediction of low-energy collision-induced dissociation spectra of peptides with three or more charges. Anal. Chem. 77, 6364–6373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hu Y., Li Y., Lam H. (2010) A semi-empirical approach to predict unobserved peptide MS/MS spectra from spectral libraries. Human Proteome Organization 9th Annual World Congress, Sydney, Australia (2010) [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sherwood C. A., Eastham A., Lee L. W., Peterson A., Eng J. K., Shteynberg D., Mendoza L., Deutsch E. W., Risler J., Tasman N., Aebersold R., Lam H., Martin D. B. (2009) MaRiMba: a software application for spectral library-based MRM transition list assembly. J. Proteome Res. 8, 4396–4405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. MacLean B., Tomazela D. M., Shulman N., Chambers M., Finney G. L., Frewen B., Kern R., Tabb D. L., Liebler D. C., MacCoss M. J. (2010) Skyline: an open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments. Bioinformatics 26, 966–968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Picotti P., Lam H., Campbell D., Deutsch E. W., Mirzaei H., Ranish J., Domon B., Aebersold R. (2008) A database of validated assays for the targeted mass spectrometric analysis of the S. cerevisiae proteome. Nat. Methods 5, 913–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ning K., Fermin D., Nesvizhskii A. I. (2010) Computational analysis of unassigned high-quality MS/MS spectra in proteome data sets. Proteomics 10, 2712–2718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ahrné E., Masselot A., Binz P. A., Müller M., Lisacek F. (2009) A simple workflow to increase MS2 identification rate by subsequent spectral library search. Proteomics 9, 1731–1736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]