Abstract

Background:

To study the pattern of Internet use across people of various professions who have access to it; the impact of Internet use on their personal, social, and occupational life; and to evaluate their Internet use on the International Classification of Diseases–Tenth Revision (ICD-10) dependence criteria and Young's Internet Addiction Diagnostic Questionnaire (IADQ).

Materials and Methods:

Hundred four respondents were assessed on a 31-items self-rated questionnaire covering all the ICD-10 criteria and Young's criteria for Internet addiction.

Results:

The typical profile of an Internet user was as follows: the mean duration of Internet use was 73.43 months (SD 44.51), two-thirds (65.38%) of them were using Internet on a regular basis for a period of more than a year, the mean duration of daily Internet use was 39.13 months (SD 35.97), the average time spent in Internet use was 2.13 h (SD 1.98) everyday, more than half (56.73%) of the sample was using Internet at least for 2 h/day, and the most common purpose of Internet use was educational for two-thirds (62.5%) of the sample. The five most commonly endorsed items were as follows: the need to use the Internet everyday (53.8%), Internet use helping to overcome bad moods (50%), staying online longer than one originally intends to (43.3%), eating while surfing (24%), and physical activity going down since one has started using the Internet (22.1%). When evaluated on ICD-10 substance dependence criteria and Young's IADQ separately, the prevalence of the ‘cases’ of Internet addiction came out to be 51.9 and 3.8%, respectively.

Conclusions:

The Internet affects the users’ life in multiple ways. The sharp difference in the prevalence estimates of Internet addiction depending on the type of criteria used shows the fragility of the construct of Internet addiction. A cautious approach should be adopted while revising the nosological system to differentiate users from those who are dependent.

Keywords: Addiction, impact, internet, prevalence

The Internet is a global system of interconnected computer networks that has become an integral part of modern life. It has become an increasingly popular notion that similar to other subjectively rewarding activities (e.g., drug use, shopping, working, running, gambling, and using the computer), using the Internet can also become the object of addiction. Various terminologies are in vogue to describe this phenomenon of excessive Internet use.[1–5] However, questions have been raised whether the Internet can be considered as the source of gambling or an object of addiction, as it is not clear what precisely Internet addicts become addicted to, although various possibilities have been suggested.[6–8]

Young was one of the first to describe excessive and problematic Internet use as an addictive disorder and modified the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for pathological gambling to construct the diagnostic criteria for pathological Internet use.[9,10] Over the years, other researchers have also come up with other diagnostic criteria, and various community and online surveys have been conducted to estimate the prevalence of Internet addiction.[11–16]

Recently, the Task Force on Substance Use Disorders of the American Psychiatric Association recommended inclusion of a topic on Internet Addiction in its forthcoming DSM-V, but only as an ‘Appendix’ (in order to stimulate further research in this area) and not in the main body discussing the addictive disorders.[17,18]

Internet use has both positive and negative aspects.[19] The positive consequences of Internet use include enhanced self-confidence, increased frequency of communication with family and friends, and feelings of empowerment.[20]

Internet use to the point of addiction, however, can have wide-ranging adverse consequences that can affect interpersonal, social, occupational, psychological, and physical domains of the individual's life.[21] Serious relationship problems including marital conflicts and increased rate of divorce due to ‘cyber affairs’ have been reported by various authors.[10,22,23] Excessive Internet use has also been reported to lead to non-work-related Internet use, impaired functioning at work, poor academic performance in schools and colleges, sleep deprivation, poor functioning of the immune system, lack of proper exercise, increased risk for carpal tunnel syndrome, back strain, eyestrain, and even cardiac arrest.[24–29]

India is not an exception to this global trend of increase in Internet use. The total number of Internet users in India is estimated to be 81 million (i.e., 6.9% of the total population) in the year 2010.[30] The profile of a typical Internet user in India is as follows: youths (72%), accessing Internet through cyber cafes (37%), with the purpose of checking mail (87%), and for general information search (80%).[31] Although Internet has been used quite frequently, there is dearth of literature with respect to its impact on life of its users from India.

The aim of this research was to study the pattern of Internet use across people of various professions who have access to it; to study the impact of Internet use on their personal, social, and occupational life; and to evaluate their Internet use on the International Classification of Diseases–Tenth Revision (ICD-10) dependence criteria and Young's Internet Addiction Diagnostic Questionnaire (IADQ).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

For this study, a 31-item self-rated questionnaire was designed. For the same, all the available Internet addiction questionnaires were reviewed. In addition, items were generated keeping the ICD-10 criteria of substance dependence in mind.[32] Initially the questionnaire had 53 items. This questionnaire was reviewed by a panel of six qualified psychiatrists, including those with a specialist experience of dealing with addictive disorders. In addition, the questionnaire was reviewed by a clinical psychologist and a psychiatric social worker working in this field. All the panelists were requested to critically review the questionnaire for completeness of addiction criteria as per substance dependence syndrome criteria of ICD-10, for completeness of excessive behaviors that could be associated with Internet use, and for overlapping questions, if any.[32] After receiving the feedback, a 42-item questionnaire was generated, which was again reviewed by all the panelists for its completeness. It was reviewed by experts for syntax as well. Finally, a 31-item questionnaire was accepted with responses in the form of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. The questionnaire covered all the ICD-10 criteria (which were covered by 1-14 questions of the questionnaire) and Young's criteria for Internet addiction.[10,32] Later, basic demographics (age, gender, level of education, and occupation), basic Internet use pattern (duration of Internet use in years, for how long are you using Internet daily, number of Internet use hours per day, and various purposes for which you use Internet), and one question tapping family history of substance dependence were added.

The questionnaire was sent to 284 persons through e-mail and was given to 38 Internet users in person over a period of 2 months by one of the authors (K.C.). Of the 284 persons approached through e-mail, 11 e-mails met with failure notice generated by the system (due to nonexistent/wrong e-mail addresses). Hence, the effective number of persons contacted through e-mail was 273. The subjects were informed about the purpose of the study and were given freedom of choice to respond or not to respond. They were also assured about maintenance of confidentiality and anonymity so that no individual responder could be identified from the collective data. The questionnaire was sent to the subjects one to four times (those who responded back were not sent reminder mails) at a weekly interval. It was presumed that the persons who would respond would provide implied consent to participate in the study. The responses on the questionnaire were evaluated on the ICD-10 substance dependence criteria and Young's IADQ.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed by using SPSS version 14.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Mean and standard deviation were calculated for the continuous variables and frequencies, and percentages were computed for the discontinuous variables. Comparisons were done by using unpaired Student's t test and chi-square test. Spearman's rank order correlation analysis was used to study the relationship between parametric variables (age, total duration of Internet use, duration of daily Internet use, time spent in Internet use everyday) and Internet addiction.

RESULTS

Of the total 312 persons contacted, 104 (33.4%) responded to the survey. Males (58.7%) outnumbered females (41.3%), and most of them had completed their graduation (N=101; 97.1%). Half of the sample comprised of doctors, about a fifth (20.2%) of sample comprised other professionals (nurses, engineers, and scientists), and the rest were students (29.8%). The mean age of the sample was 27.73 years (SD 5.14; range 20-49), with females (mean 24.79; SD 4.64) being significantly younger (t-test value 5.56, P<0.001) than males (mean 29.80; SD 4.44).

The mean duration of Internet use was 73.43 months (SD 44.51), and this was significantly longer (t-test value 3.00; P<0.001) for males (mean 84.03, SD 43.75) compared to females (mean 58.39, SD 41.58). Two-thirds (65.38%) of them were using Internet on a regular basis for a period of more than a year, and the mean duration of daily Internet use was 39.13 months (SD 35.97) and this was significantly longer (t-test value 3.43; P=0.001) for males (mean 48.80, SD 36.48) than for females (mean 25.41,SD 30.73). The average time spent in Internet use was 2.13 h everyday (SD 1.98), with no significant difference between males (mean 2.44, SD 2.17) and females (mean 1.69, SD 1.60). More than half (56.73%) of the sample was using Internet at least for 2 h/day, and the daily Internet use of more than half of the sample (58.6%) was in the range of 1-3 h. Nine (8.65%) subjects had a first-degree relative who was currently using or had used alcohol or any other drug of abuse, leading to marked dysfunction in social and occupational functioning.

When the respondents were asked to rank the purposes of their Internet use on a scale of 1 (i.e., most common purpose for use) to 5 (i.e., least common purpose for use), the most common purpose of use was educational for two-thirds (62.5%) of the sample. Other common purposes of use were chatting (50.9%), recreational (37.5%), and e-mailing (33.6%).

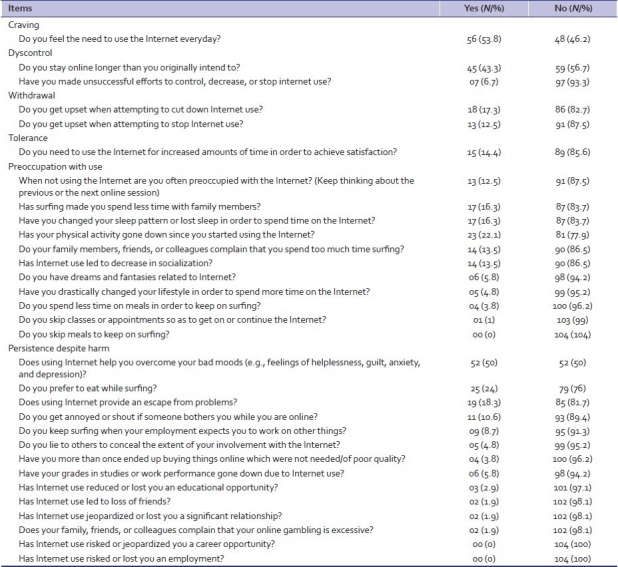

Table 1 shows the items of Internet use questionnaire grouped under suitable criteria of ICD-10 substance dependence. The five most commonly endorsed items were as follows: the need to use the Internet everyday (53.8%), Internet use helping to overcome bad moods (50%), staying online longer than one originally intends to (43.3%), eating while surfing (24%), and physical activity going down since one has started using the Internet (22.1%).

Table 1.

Items of Internet use questionnaire

For assessing the ICD-10 criteria, any subject who answered positively on any 1 item covering a particular criterion was considered to be fulfilling that criterion. Accordingly, the ICD-10 dependence criteria that were fulfilled by about half of the sample were persistence despite harm (54.8%), craving (53.8%), preoccupation with use (51%), and dyscontrol (49%). The ICD-10 criteria of withdrawal (20.2%) and tolerance (14.4%) were fulfilled by only a few subjects. Overall, 51.9% of the sample met any 3 of the total 6 ICD-10 criteria together, and hence could be considered as ‘cases’ of Internet addiction according to the definitional equivalent of the ICD-10 diagnostic guidelines for substance dependence.

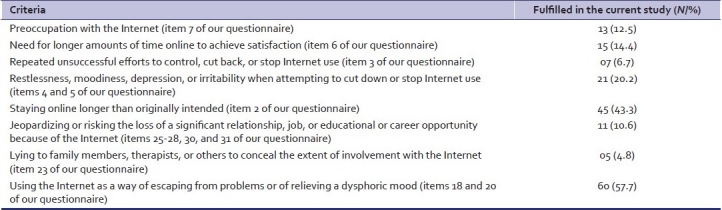

From the 31 items of the Internet use questionnaire, items similar to Young's IADQ [Table 2] were chosen; the prevalence of Internet addiction as per IADQ (i.e., had at least five criteria out of eight) was only 3.8%.

Table 2.

Young's criteria for internet addiction

Correlation analysis

Significant association was seen between dependence as per ICD-10 criteria and male gender (Spearman's rank order correlation 0.325; P<0.01), duration of daily Internet use (Spearman's rank order correlation 0.228; P<0.05), and average time spent in Internet use everyday (Spearman's rank order correlation 0.273; P<0.01).

DISCUSSION

This was a preliminary survey to evaluate the Internet addiction and impact of Internet use in a purposive Indian sample. In the present study, more male subjects were addicted to the Internet compared with their female counterparts. Available data from the community and online surveys as well as clinical samples[33–38] suggest that Internet addiction appears to have a male preponderance. In a Finnish study, men had significantly higher mean score on the Internet Addiction Test (IAT) than did women.[39] A study that included adolescents revealed 50% increased odds for males to be addicted to the Internet (OR=1.5, 95% CI=1.1–2.2) when compared with females.[40] It is suggested that the gender distribution may be explained by the fact that men are more likely to express interest in games, pornography, and gambling activities that have all been associated with problematic Internet use.[33]

Studies have found that the Internet addiction usually manifests itself in the late 20s or early 30s.[41,42] The mean age (27.73±5.14 years) of the subjects in the index study also support the same. Black et al.[42] reported a lag time of 11 years from the initial use to the problematic use. Other studies have also reported a 3-year history of problematic use at the time of interview.[41,42] Subjects in the present study had a lag period of approximately 6 years (73.43±44.51 months) from the initial computer use to the index assessment for Internet addiction, which is in the range of that reported in the other studies.[41,42] Subjects in the present study used Internet for 2.13 h/day, which translates into 14.91 h/week, which is lower compared with that reported by other studies.[9,41]

In the index study the most commonly endorsed items on Internet use questionnaire were the need to use the Internet everyday (53.8%), Internet use helping to overcome bad moods (50%), staying online longer than one originally intends to (43.3%), eating while surfing (24%), physical activity going down since one has started using the Internet (22.1%), using Internet to escape from problems (18.3%), becoming upset on attempting to cut down Internet use (17.3%), surfing being responsible for spending less time with family members (16.3%), surfing causing a change in sleep pattern (16.3%), and so on. Previous studies from other countries have also reported similar positive and negative impact of Internet use as found by us.[25,42,43] A study from India too reported that those who were dependent on Internet would delay their work to spend time online, lose sleep due to logging in till late night, feel lonelier, and feel life would be boring without the Internet as compared with nondependent subjects.[44]

The studies that have estimated the prevalence of Internet addiction have come up with varying results (0.9-38%) depending on the criteria used and the sample studied.[34,45] In a methodologically rigorous study that involved a random telephone survey of 2513 adults aged 18 years and older and employed four criteria sets, prevalence rates varied from 0.3 to 0.7%.[13] The only published study from India, which evaluated Internet addiction by using Davis Online Cognition Scale in school-going children aged 16-18 years, reported a prevalence of 18%.[44]

The reasons for huge variation in the prevalence rates could be as follows: difficulty in conceptualizing Internet addiction, heterogeneity of population studied, lack of availability of standard diagnostic criteria, studies failing to differentiate between essential and nonessential Internet use, and nonconsideration of psychiatric comorbidity in some of the studies.[13,16,33,36–38,45–48] More surprisingly, the studies that have used Young's IAT have also come up with varied prevalence rates. This suggests that a single instrument cannot reliably pick up the cases of Internet addiction. Another fact that contributes to a wide variation in the prevalence rates is the fact that Internet addiction has been viewed from different theoretical perspectives such as an impulse control disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, and substance use disorder.[16] However, there is very little agreement between these on the crucial components and dimensions of Internet addiction. In the present study, the prevalence rate of 51.9% as per ICD-10 substance dependence criteria seems to be overinflated whereas the prevalence of 3.8% as per IADQ is probably an underestimate, although both the figures are very near to range reported in the literature.

This wide variation suggests that some conceptual issues have to be addressed before we even plan to define Internet addiction and estimate its prevalence. For example, are we going to diagnose Internet addiction in people who are compelled to use Internet for prolonged periods of time because of the nature of their occupation? What about people who are logged on to Internet all the time just checking their mails intermittently? Should it be appropriate to diagnose Internet addiction in a job seeker or a researcher who try to keep abreast of the recent developments by logging on to the Internet? What about people who use Internet as a medium of sexual gratification? Sexual compulsion may be a more appropriate diagnosis in such cases. The Internet, like mobile phones and other electronic gadgets, has become a part and parcel of modern life. An in-depth interview of the subject, with corroboration of history from the family members, might be a more reasonable approach to diagnose Internet addiction. A diagnostic questionnaire at best can serve as a screening instrument to detect the population at risk of Internet addiction rather than identifying the persons having full blown disorder.

The findings of the present study must be considered within its limitations. The sample size was small and the sampling was nonrandom. No face-to-face interview was conducted to explore the phenomenology of Internet addiction; data were exclusively gathered by the self-reporting Internet use questionnaire. The instrument used in the index study has not been validated. Items were generated from various questionnaires developed to identify Internet addiction and some items were constructed keeping the ICD-10 criteria of substance dependence in mind. It can be argued that ICD-10 dependence criteria are developed for psychoactive substance dependence and hence cannot be applied to those substance-neutral behaviors commonly performed in daily life. Thus, the item for assessing the criterion craving (item 1: Do you feel the need to use the Internet everyday?) would easily capture the work-related Internet users for whom daily Internet use is essential. The questionnaire is self-administered and thus the authors cannot clarify the meaning of such items. That is why more than 50% of the subjects replied ‘Yes’. However, when the hardcore physical dependence features, i.e., tolerance and withdrawal, are concerned, only about 15% of subjects fulfill such criteria. As mentioned earlier, this study did not differentiate between essential and nonessential Internet use. The issue of the presence of psychiatric comorbidity in the subjects was also not considered.

Nevertheless, in view of the current ongoing debate on Internet addiction after its inclusion in the proposal draft of DSM-V, this study from India could provide some insights into the impact of Internet use and, more importantly, the issues facing the delineation of a syndrome of ‘Internet addiction’. The sharp difference in the prevalence estimates of Internet addiction depending on the type of criteria used shows the fragility of the construct of Internet addiction. This study should not be cited as a usual ‘prevalence’ study of a particular disorder, because of both sampling issues and methodological issues as mentioned. Moreover, the issue of whom to treat and whom not to still remains open. Before embarking on any kind of major manipulation to the diagnostic system, a through understanding of the concept of Internet addiction is required. This study brings into focus some of these conceptual and methodological issues that must be debated before any decisive action in this regard is taken.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shaffer HJ. The most important unresolved issue in the addictions: Conceptual chaos. Subst Use Misuse. 1997;32:1573–80. doi: 10.3109/10826089709055879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaffer HJ. Strange bedfellows: A critical view of pathological gambling and addiction. Addiction. 1999;94:1445–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.941014451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silver G. San Francisco: Harper and Row; 1979. The dope chronicles: 1850-1950. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau; 2005. US Census Bureau. Computer and Internet use in the United States: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw M, Black DW. Internet addiction: Definition, assessment, epidemiology and clinical management. CNS Drugs. 2008;22:353–65. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200822050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaffer HJ, Hall MN, Vander Bilt J. “Computer addiction”: A critical consideration. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:162–8. doi: 10.1037/h0087741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffiths M. Internet addiction: Does it really exist? In: Gackenbach J, editor. Psychology and the Internet. Waltham, Massachusetts: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caplan SE. Problematic Internet use and psychosocial well-being: Development of a theory-based cognitive-behavioral measurement instrument. Comput Human Behav. 2002;18:553–75. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young KS. 1998. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; Caught in the net: How to Recognize the Signs of Internet Addiction - and A Winning Strategy for Recovery. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young K. Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychol Behav. 1996;3:237–44. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shapira N, Goldsmith T, Keck P, Jr, Khosla UM, McElroy SL. Psychiatric features of problematic Internet use. J Affect Disord. 2000;57:267–72. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shapira NA, Lessig MC, Goldsmith TD, Szabo ST, Lazoritz M, Gold MS, et al. Problematic Internet use: Proposed classification and diagnostic criteria. Depress Anxiety. 2003;17:207–16. doi: 10.1002/da.10094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aboujaoude E, Koran LM, Gamel N, Large MD, Serpe RT. Potential markers for problematic Internet use: A telephone survey of 2,513 adults. CNS Spectr. 2006;11:750–5. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900014875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tao R, Huang X, Wang J, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Li M. Proposed diagnostic criteria for Internet addiction. Addiction. 2010;105:556–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petersen KU, Weymann N, Schelb Y, Thiel R, Thomasius R. [Pathological Internet use--epidemiology, diagnostics, co-occurring disorders and treatment] Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2009;77:263–71. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1109361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chakraborty K, Basu D, Vijaya Kumar KG. Internet addiction: Consensus, controversies, and the way ahead. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2010;20:123–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DSM-5 Development, American Psychiatric Association. Substance-related disorders. [Last acccessed on 2010 May 26]. Available from: http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevisions/Pages/Substance-RelatedDisorders.aspx .

- 18.O’Brien CP. Commentary on Tao et al. Internet addiction and DSM-V. Addiction. 2010;105:565. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guan SS, Subrahmanyam K. Youth Internet use: Risks and opportunities. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22:351–6. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32832bd7e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark DJ, Frith KH, Demi AS. The physical, behavioural and psychosocial consequences of Internet use in college students. Comput Inform Nurs. 2004;22:153–61. doi: 10.1097/00024665-200405000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murali V, George S. Lost online: An overview of Internet addiction. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwiatkowska A, Ziolko E, Krysta K, Muc-Wierzgon M, Krupka- Matuszczyk I. Impact of Internet abuse on human relationships. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22:S192. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quittner J. Divorce Internet style. Time. 1997;14:72. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beard K. Internet addiction.Current status and implications for employees. J Employ Couns. 2002;39:2–11. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menlo Park, California: Robert Half International; 1996. Surf's up! Is productivity down? pp. 10–1. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphey B. Computer addictions entangle students. APA Monitor. 1996;27:38–9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scherer K. College life on-line: Healthy and unhealthy internet use. J Coll Stud Dev. 1997;38:655–65. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young KS. Internet addiction: Symptoms, evaluation and treatment. In: Van de Creek L, Jackson T, editors. Innovations in clinical practice: A source book. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press; 1999. pp. 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christakis DA, Moreno MA. Trapped in the Net.Will Internet addiction become a 21st-century epidemic? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:959–60. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Internet Usage Stats and Telecommunications Market Report. [Last accessed on 2011 Feb 9]. Available from: URL: http://www.internetworldstats.com/asia/in.htm .

- 31.Internet in India – 52 Million Active Users in India, 37% Internet access happens from cybercafés. [Last accessed on 2011 Feb 9]. Available from: URL: http://www.pluggd.in/internet-usage-in-india-marketstatistics-297/

- 32.Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1994. World Health Organisation. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morahan-Martin J, Schumacher P. Incidence and correlates of pathological Internet use among college students. Comput Human Behav. 2000;16:13–29. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoo HJ, Cho SC, Ha J, Yune SK, Kim SJ, Hwang J, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity symptoms and Internet addiction. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58:487–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2004.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niemz K, Griffiths M, Banyard P. Prevalence of pathological Internet use among university students and correlations with self-esteem, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) and disinhibition. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2005;8:562–70. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2005.8.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chou C, Hsiao MC. Internet addiction, usage, gratification, and pleasure experience: The Taiwan college students’ case. Comput Educ. 2000;35:65–80. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaltiala-Heino R, Lintonen T, Rimpela A. Internet addiction? Potentially problematic use of the Internet in a population of 12-18 year old adolescents. Addict Res Theory. 2004;12:89–96. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johansson A, Gotestam K. Internet addiction: Characteristics of a questionnaire and prevalence in Norwegian youth (12-18 years) Scand J Psych. 2004;45:223–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2004.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Korkeila J, Kaarlas S, Jääskeläinen M, Vahlberg T, Taiminen T. Attached to the web – harmful use of the Internet and its correlates. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;25:236–41. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lam LT, Peng ZW, Mai JC, Jing J. Factors associated with Internet addiction among adolescents. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2009;12:551–5. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2009.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Young K, Pistner M, O’Mara J, Buchanan J. Cyber-disorders: The mental health concern for the new millennium. Cyberpsychol Behav. 1999;2:475–9. doi: 10.1089/cpb.1999.2.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Black DW, Belsare G, Schlosser S. Clinical features, psychiatric comorbidity, and health-related quality of life in persons reporting compulsive computer use behavior. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:839–44. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ko CH, Yen JY, Chen CS, Yeh YC, Yen CF. Predictive values of psychiatric symptoms for internet addiction in adolescents: A 2-year prospective study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:937–43. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nalwa K, Anand AP. Internet addiction in students: A cause of concern. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2003;6:653–6. doi: 10.1089/109493103322725441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jang KS, Hwang SY, Choi JY. Internet addiction and psychiatric symptoms among Korean adolescents. J Sch Health. 2008;78:165–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghassemzadeh L, Shahraray M, Moradi A. Prevalence of Internet addiction and comparison of Internet addicts and non-addicts in Iranian high schools. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008;11:731–3. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim K, Ryu E, Chon MY, Yeun EJ, Choi SY, Seo JS, et al. Internet addiction in Korean adolescents and its relationship to depression and suicidal ideation: A questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43:185–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pallanti S, Bernardi S, Quercioli L. The Shorter PROMIS Questionnaire and the Internet Addiction Scale in the assessment of multiple addictions in a high-school population: Prevalence and related disability. CNS Spectr. 2006;11:966–74. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900015157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]