Abstract

Background:

Optimal depth of endotracheal tube (ET) placement has been a serious concern because of the complications associated with its malposition.

Aims:

To find the optimal depth of placement of oral ET in Indian adult patients and its possible determinants viz. height, weight, arm span and vertebral column length.

Settings and Design:

This study was conducted in 200 ASA I and II patients requiring general anaesthesia and orotracheal intubation.

Methods:

After placing the ET with the designated black mark at vocal cords, various airway distances were measured from the right angle of mouth using a fibre optic bronchoscope.

Statistical Analysis:

The power of the study is 0.9. Mean (SD) and median (range) of various parameters and Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated.

Results:

The mean (SD) lip-carina distance, i.e., total airway length was 24.32 (1.81) cm and 21.62 (1.34) cm in males and females, respectively. With black mark of ET between vocal cords, the mean (SD) ET tip-carina distance of 3.69 (1.65) cm in males and 2.28 (1.55) cm females was found to be considerably less than the recommended safe distance.

Conclusions:

Fixing the tube at recommended 23 cm in males and 21 cm in females will lead to carinal stimulation or endobronchial placement in many Indian patients. The lip to carina distance best correlates with patient's height. Positioning the ET tip 4 cm above carina as recommended will result in placement of tube cuff inside cricoid ring with currently available tubes. Optimal depth of ET placement can be estimated by the formula “(Height in cm/7)-2.5.”

Keywords: Carina, endotracheal intubation, general anaesthesia, tracheal length

INTRODUCTION

Endotracheal intubation is one of the most important and most commonly performed procedures in the field of anaesthesiology, emergency medicine and critical care. One of the major concerns while securing endotracheal tube (ET) is its correct and appropriate depth of placement because of the major complications associated with its malplacement.[1] Too deep a placement can cause impingement on the carina and thus sympathetic stimulation leading to tachycardia, hypertension and/or bronchospasm. Furthermore, endobronchial intubation might result in hyperinflation of the intubated lung, thereby increasing the risk of pneumothorax. Also, at the same time, the non-ventilated lung might become atelectatic with resultant systemic hypoxemia. Conversely, if the depth of insertion of ET beyond vocal cords is too less, the cuff might impinge on the vocal cords on inflation leading to sympathetic stimulation, trauma, recurrent laryngeal nerve compression and increased risk of accidental extubation.

Various techniques have been described to confirm the depth of ET placement including cuff palpation in suprasternal notch,[2] chest X-Rays,[3] fibre optic bronchoscopy,[4] etc., with fibre optic bronchoscopy being the most dependable.[4] However, 5-point auscultation remains the most common method of ascertaining ET position because of feasibility and ease of performing it.

Most of the anaesthesia textbooks recommend depth of placement of ET to be 21 cm and 23 cm in adult females and males, respectively, from central incisors.[5,6] It is suggested that the tip of ET should be at least 4 cm from the carina, or the proximal part of the cuff should be 1.5 to 2.5 cm from the vocal cords.[6] Considering that the length of trachea as well as the distance from teeth to vocal cords is variable, securing ET at a fixed length will result in endobronchial intubation or endolaryngeal placement of the ET cuff in some patients. Few studies have been carried out to determine the correct depth of placement of ET both orally and nasally suggesting positive correlation between height and airway length.[7–9] Also, most of the studies in the literature quote the depth of insertion from midline, while the ET is usually secured at the angle of mouth. However, no study could be found, which investigates the correct depth of placement of ET in Indian population and its correlation with various physical parameters.

Thus, this scientific study was conducted with the aim of determining the optimal depth of ET placement in Indian adult population and its relation with height, weight, arm span and vertebral column length.

METHODS

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval and written informed consent of the patients, this prospective study was carried out in 200 ASA Grade I and II adults who were planned for elective surgery under general anaesthesia requiring orotracheal intubation. Patients requiring use of flexometallic or preformed tubes or having altered airway anatomy, e.g., swelling or deformity in oral, pharyngeal, laryngeal region, and swelling or contractures in the neck were excluded from the study. Age, weight, height, arm span and vertebral column length (from external occipital protuberance to the tip of coccyx) of the patients were recorded.

Intravenous line was established and pethidine 0.5 mg/kg was administered intravenously. General anaesthesia was induced using intravenous thiopentone sodium 5.0 mg/kg. Vecuronium bromide 0.1 mg/kg was administered to facilitate tracheal intubation. Patient's trachea was intubated by performing direct laryngoscopy in sniffing position using cuffed PVC ET (Romsons Sci and Surg Ltd., Agra, India). Appropriate size ET was selected for tracheal intubation, i.e., 7.0 or 7.5 mm ID for females and 8.0 to 9.0 mm ID for male patients. The tube was placed such that the cuff of the endotracheal tube (ETT) disappeared below the vocal cords and the black mark lay between the vocal cords. The head position was made neutral. The ET was secured by tape at the right angle of mouth. Breathing circuit was then attached and placement of ET confirmed by 5-point auscultation and capnography.

A swivel connector with a port for fibre optic bronchoscope (FOB) was attached to the machine end of the ET and anaesthesia was continued. FOB was introduced into the ET through swivel connector and following distances were measured using a tape having 1 mm markings:

Swivel connector to the lips (L): With the tip of FOB at the level of the lower lip, this distance would be total length of FOB insertion cord minus length of the FOB insertion cord above the swivel connector.

Swivel connector to the carina (end of trachea) (C): With the tip of FOB at the level of tracheal carina, this distance would be total length of FOB insertion cord minus length of the FOB insertion cord above the swivel connector.

Swivel connector to the tip of endotracheal tube: With the tip of FOB at the level of tip of the ET, this distance would be total length of FOB insertion cord minus length of the FOB insertion cord above the swivel connector.

Swivel connector to the beginning of trachea (CT): For this last distance, the FOB was withdrawn till the black mark on ETT was just visible through FOB and then FOB light was switched off. A sharp light (Trachlight™ – Laerdal Medical AS; Stavanger, Norway) was then placed externally at the cricotracheal membrane (the beginning of the proximal end of trachea). The depth of FOB (with its light “Off”) was then adjusted for the extratracheal glow to be best visible intratracheally. The distance between swivel connector and the beginning of trachea (i.e., FOB tip positioned as described above) was recorded. The surgery was allowed to start after the measurements. Controlled ventilation was carried throughout the procedure using oxygen-nitrous oxide mixture with isoflurane. At the end of surgical procedure, glycopyrrolate (10 μg/kg) and neostigmine (50 μg/kg) were used to reverse the residual neuromuscular blockade.

All the patients were monitored using pulse oximetry, Electrocardiography (ECG), capnography and non-invasive blood pressure measurements.

Statistical analysis

The sample size of 200 was determined by keeping power of the study as 0.9. The data were analysed using statistical software “SPSS 12.0” and mean (SD) and median (range) of various parameters were calculated. Correlation-Regression analysis was done for correlating various distances and patient factors and Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated. Standard tests of significance were applied to find out the P value. P<0.05 was considered as significant.

RESULTS

The study group of 200 adult patients comprised of 173 females and 27 males.

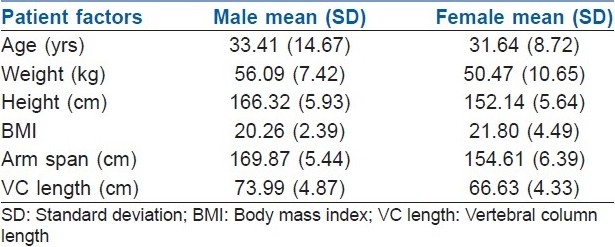

The mean (SD) age was 33.41 (14.67) years and 31.64 (8.72) years for males and females, respectively. The mean weight (SD) was 56.09 (7.42) kg and 50.47 (10.65) kg for males and females, respectively. The mean height (SD) was 166.32 (5.93) cm and 152.139 (5.64) cm for males and females, respectively. The mean arm span (SD) was 169.87 (5.44) cm and 154.61 (6.39) cm for males and females, respectively. The mean vertebral column length (SD) was 73.99 (4.87) cm and 66.63 (4.33) cm for males and females, respectively [Table 1].

Table 1.

Patient statistics

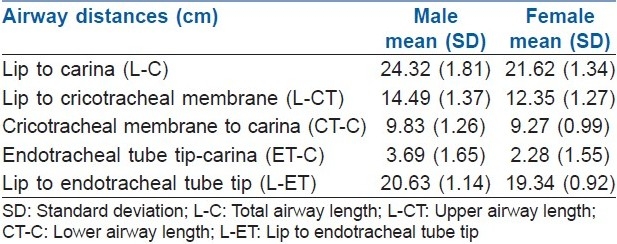

The Airway distances measured in males and females are shown below [Table 2].

Table 2.

Airway distances among males and females

Patient factors were correlated with various airway distances in males and females separately. In males, total airway length (L-C) and lower airway length (CT-C) were found to be significantly correlated with height, arm span and vertebral column length (P<0.05), but the correlation with upper airway length (L-CT) was not statistically significant. However, in females, both the total as well as upper airway length were found to be significantly correlated with height, arm span and vertebral column length (P<0.05).

The correlation between body mass index (BMI) and airway distances was statistically insignificant in both males and females.

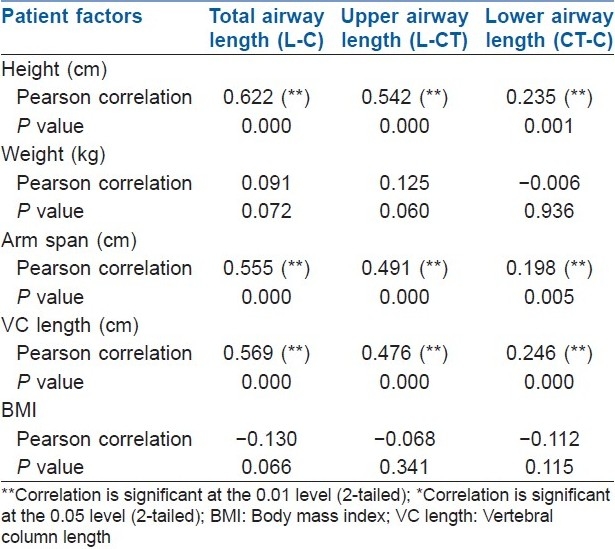

When the various patient factors were correlated with airway lengths in all patients (males and females together), it was found that the total and upper airway length correlated significantly with height, arm span and vertebral column length (P<0.01). Though the lower airway length was also found to have a statistically significant correlation with height, arm span and vertebral column length, the coefficient of correlation was much less suggesting a poor correlation [Table 3]. BMI and airway distances were not found to be correlated.

Table 3.

Correlation of patient factors with airway distances in all patients

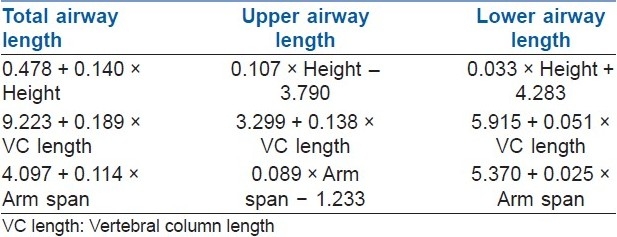

Linear regression and estimated formulae of airway distances

Regression analysis of various patient factors and airway distances was performed and formulae were calculated to estimate various airway distances by these patient variables. The patient's gender is a constant variable that could be excluded in a linear regression analysis. The formulae of linear regression are given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Formulae for various airway distances

DISCUSSION

The optimal placement of an ET should ensure that the tip of the tube is sufficiently distant from carina to avoid endobronchial intubation, especially during movement of head and neck.[10] In addition, the cuff of the ET should be distal to the cricoid ring to avoid damage to vocal cords and inadvertent extubation.[11,12]

In our study, we measured true anatomical tracheal length from cricotracheal membrane to carina. The purpose of choosing cricotracheal membrane as the reference point was to measure true tracheal length in our population and that the cuff of ET should be beyond cricoid to prevent damage to vocal cords and recurrent laryngeal nerve. Also, as cricoid is a complete ring, the concern about mucosal ischemia by cuff pressure is much higher. All other researchers have taken vocal cords as the reference point for measuring tracheal length.[7,9,10] May be, this was because of the ease of measuring this distance or may be that no practical method of locating cricotracheal membrane could be found. Chong et al.[9] however gave the reason of choosing vocal cord carina distance as that it is this part of the airway which accommodates the ET from black mark(s) to the tip and thus is important during clinical airway management.

Comparing airway distances measured in our study to those quoted by other researchers and textbooks reveal that the mean airway length from lip to carina is smaller in Indian population. Also, the trachea in Indian patients is considerably shorter. This emphasises the fact that the recommendation to secure the ET at 23 cm in males and 21 cm in females will result in carinal impingement and endobronchial intubation in most of the Indian patients. Moreover, this depth of fixation has been recommended by measuring the airway distances in midline, although the ET is fixed at the right angle of mouth, which is a shorter distance as compared with that in midline.[13] Therefore, securing the tube according to this recommendation will further increase the chances of endobronchial intubation.

Various anaesthesia textbooks[5,6] state that the ET tip to carina distance should be at least 4 cm. Also, Goodman et al.[14] recommended that the mean endotracheal tip to carina distance that will prevent carinal impingement and endobronchial intubation should be 4 cm (3–5 cm). Result analysis shows that even with our current depth of fixation being 20.67 cm in males and 19.35 cm in females, the ET tip to carina distance was 3.69 cm and 2.28 cm in males and females, respectively, which means 37% male and 72.25% female patients have tube tip to carina distance less than 3 cm. The ET tip was endobronchial in 5/173 female patients at this depth of fixation. This implies that a considerable number of patients may have been prone to endobronchial shift or carinal impingement of the tube.

Various patient factors were correlated to airway distances. The lip to carina distance correlates best with patient's height [Table 3]. The lip to carina distance also correlates with the vertebral column length and arm span. The upper airway length seems to correlate poorly with patient's height in male patients. The reason for this could be that the sample size of male patient is very small. The degree of correlation can be better defined with a larger sample size. In females, however, the correlation between upper airway length and patient factors was found to be best with height followed by vertebral column length followed by arm span. Techanivate et al.[8] found poor correlation between height and upper airway length and a moderate correlation between height and vocal cords to carina distance. They also suggested “Chula formula” based on height to estimate adequate depth of insertion of ET. Chong et al.[9] in their study found statistically significant correlation between vocal cord to carina distance and patient's height and thyrosternal distance and devised a formula to predict this distance. Because of the differences between the airway distances measured in our study and other studies, it will be very unpractical to apply the same formulae to Indian population.

Results of linear regression analysis of the data show that among all patient factors studied, height will best predict the adequate airway length. Also, it is easier to measure height than the vertebral column length and arm span. So, lip to carina distance from right angle of mouth can be calculated by the formula:

(L-C) = 0.478 + 0.14 × height (cm)

As previously stated, various textbooks describe that the depth of placement of endobronchial tube will be adequate when the tip of endobronchial tube rests 4 cm (3-5 cm) proximal to carina.[5,6,14] The basis of keeping these Figures was to allow sufficient distance between the tube tip and carina on one hand, and the tube cuff and cricoid cartilage on the other, to prevent complications associated with movement of head and neck, change in patient position or creation of pneumoperitoneum.

Considering that the safe ET tip to carina distance is 3 to 5 cm, the adequate depth of ET tip in Indian patients from right angle of mouth can be estimated by the following formula (simplified):

Adequate depth of endotracheal tube =

{Height (cm)/7} – 2.5

The above mentioned formula can guide optimal depth of placement of oral ET with tube tip 3 cm above carina in Indian adult patients. The mean height in sample population was 166.32 cm in males and 152.14 cm in females. Accordingly, the average depth of fixation of oral ET should be 20.26 cm in males and 18.23 cm in females from right angle of mouth.

Proper placement of ET also requires that the cuff should be well below cricoid. It seems prudent to avoid the cricoid as this part of the airway is a complete ring as opposed to the trachea which has a membranous posterior wall that may act to relieve the pressure of an over-inflated tracheal tube cuff. To know the relation between the position of proximal edge of the cuff and the cricoid, tracheal tubes used in this study, i.e., 7.0, 7.5, 8.0, 8.5 mm ID (Romsons Sci and Surg Ltd., Agra, India), were analysed. We found that the proximal edge of the cuff was 6.0 cm from the ET tip. It was same in all the sizes used (7.0-8.5 mm ID). These are the sizes which are used in most of the Indian adult patients requiring orotracheal intubation. If the tip of ET is placed 4 cm above carina, then the proximal part of the cuff will lie 10 cm above carina. But, the mean tracheal length (SD) in our population was found to be 9.83 (1.26) cm in males and 9.27 (0.99) cm in females. This means that the cuff would be lying inside the cricoid ring in most of the patients.

The recommendation is to place the proximal part of the cuff 1.5 to 2.5 cm from vocal cords.[6] Cavo[11] recommended placement of a guide mark on ET at 1.5 cm above the proximal end of cuff to prevent damage to vocal cords and anterior branch of recurrent laryngeal nerve. Mehta[12] suggested to place the depth mark at 2.5 cm for males and 2.25 cm for females above the proximal end of cuff. Hartrey and Kestin[15] suggested this guide mark to be placed 3 cm above proximal end of cuff and 8 cm from ET tip.

Placing the tube in this manner will ensure the safe placement of the tip of ET tip and will avoid carinal impingement and endobronchial migration, especially during head and neck movement, creation of pneumoperitoneum and trendelenburg position. However, there might be a high risk of pressure on cricoid by the proximal part of cuff due to “tip to proximal edge of cuff distance” on the available tubes.

CONCLUSION

To conclude, among all the patient factors studied, “height of the patient” best correlates with the “airway length.” The mean airway distances are smaller in Indian population so that the average depth of fixation of oral ET should be 20.26 cm in males and 18.23 cm in females from right angle of mouth. We also recommend to the ET manufacturers to shorten the proximal cuff to ET tip distance to avoid the placement of tube cuff inside cricoid ring by shortening the tracheal cuff and/or shortening the post-cuff distance while still including a “Murphy eye” to mark proximal edge of cuff for easy identification and to place the distance markers at 2 and 4 cm from the proximal edge of the cuff.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Owen RL, Cheney FW. Endobronchial intubation: A preventable complication. Anesthesiology. 1987;67:255–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198708000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cullen DJ, Newbower RS, Gemer M. A new method of positioning endotracheal tubes. Anesthesiology. 1975;43:596–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197511000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunel W, Coleman DL, Schwartz DE, Peper E, Cohen NH. Assessment of routine chest roentgenograms and physical examination to confirm endotracheal tube position. Chest. 1989;96:1043–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.5.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kazuna S, Kozo Y. Reliability of auscultation of bilateral breath sounds in confirming endotracheal tube position (letter) Anesthesiology. 1995;83:1373. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199512000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone DJ, Gal TJ. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005. Airway Management: In Miller's Anesthesia; pp. 1431–2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorsch JA, Dorsch SE. 4th Ed. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1999. Tracheal tubes: Understanding Anesthesia Equipment; p. 589. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherng CH, Wong CS, Hsu CH, Ho ST. Airway length in adult: Estimation of optimal tube length for orotracheal intubation. J Clin Anesth. 2002;14:271–4. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(02)00355-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Techanivate A, Rodanant O, Charoenraj P, Kumwilaisak K. Depth of endotracheal tubes in Thai adult patients. J Med Assoc Thai. 2005;88:775–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chong DY, Greenland KB, Tan ST, Irwin MG, Hung CT. The clinical implication of the vocal cords-carina distance in anaesthetized Chinese adults during orotracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:489–95. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartrey R, Kestin IG. Movement of oral and nasal tracheal tubes as a result of changes in head and neck position. Anaesthesia. 1995;50:682–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1995.tb06093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavo JW., Jr True vocal cord paralysis following intubation. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:1352–9. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198511000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehta S. Intubation guide marks for correct tube placement.A clinical study. Anesthesia. 1991;46:306–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1991.tb11504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma K, Varshney M, Kumar R. Tracheal tube fixation: The effect on depth of insertion of midline fixation compared to the angle of the mouth. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:383–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman LR, Conrardy PA, Laing F, Singer MM. Radiographic evaluation of endotracheal tube position. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1976;127:433–4. doi: 10.2214/ajr.127.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartrey R, Kestin IG. Movement of oral and nasal tracheal tubes as a result of changes in head and neck position. Anaesthesia. 1995;50:682–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1995.tb06093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]