Abstract

A fast and easy modified QuEChERS (quick, easy, cheap, rugged and safe) extraction method has been developed and validated for determination of 33 parent and substituted polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in high-fat smoked salmon that greatly enhances analyte recovery compared to traditional QuEChERS procedures. Sample processing includes extraction of PAHs into a solution of ethyl acetate, acetone and iso-octane followed by cleanup with dispersive SPE and analysis by GC-MS in SIM mode. Method performance was assessed in spike recovery experiments (500 ng/g wet weight) in three commercially available smoked salmon with 3 – 11% fat. Recoveries of some 2, 3 and 5-ring PAHs were improved 50 – 200% over traditional methods, while average recovery across all PAHs was improved 67%. Method precision was good with replicate extractions typically yielding relative standard deviations < 10% and detection limits were in the low ng/g range. With this method, a single analyst could extract and cleanup ≥ 60 samples for PAH analysis in an 8 hour work day.

Keywords: PAHs, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, QuEChERS, smoked salmon, fish, seafood, bio-matrix, food safety

INTRODUCTION

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and their substituted derivatives are widespread environmental contaminants that may originate from petrogenic or pyrogenic sources. PAHs are present in smoke as combustion by-products (1–3) and display a range of toxic, mutagenic and carcinogenic properties (4–5). It has been demonstrated that PAH burdens are generally higher in smoked foods than in the corresponding non-smoked foods (6–8) and that PAH profiles in foods are combustion material specific (9). Bio-analytical methods that allow for the rapid monitoring of these residues in lipid-rich foods are therefore important for monitoring human dietary exposure to PAHs.

Analytical methods have been developed for assessing PAH residue loads in many matrices with the distinguishing factor being the mode of sample preparation. Common preparation techniques include solid-liquid extraction, soxhlet extraction, sonication assisted extraction or accelerated solvent extraction coupled to a sample cleanup procedure using solid-phase extraction or gel permeation chromatography (6–13). However, these methods are often labor, time and solvent intensive, require advanced analytical expertise and lab equipment and rely on the use of chlorinated extraction solvents. To overcome these challenges, QuEChERS (quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged and safe) based sample processing procedures have been investigated.

Traditionally, the QuEChERS method has been used for the rapid (< 15 min/batch) determination of pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables where sample extraction involves addition of acetonitrile and subsequent liquid-liquid partitioning of residues through the addition of magnesium sulfate, sodium chloride and various pesticide specific pH buffering agents such as sodium acetate or sodium citrate. Sample cleanup is then achieved using various dispersive solid-phase extraction materials and magnesium sulfate to remove polar matrix components and water (14). The stream-lined nature of the QuEChERS procedure has led to its implementation in the analysis of veterinary pharmaceuticals in animal tissues, mycotoxins in breakfast cereals and flours, phthalates in fruit jellies and oil dispersion surfactants used in the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill (15–19). Furthermore, several QuEChERS methods have been developed for the analysis of PAHs in seafood such as shrimp, scallops, mussell and finfish (20–25).

Though several QuEChERS based PAH methods have been previously described, none have been validated in high-fat bio-matrices (> 3.5% fat) or with substituted PAHs. Application of traditional QuEChERS methods to PAH extraction from high-fat salmon led to poor recoveries, typically averaging only 61–68%. Most QuEChERS methods are validated using only 16 EPA priority pollutant PAHs in low-fat National Institute of Standards and Technology standard reference materials, such as mussel tissue. Given the unmet need for a robust PAH method in high-fat bio-matrices, we sought to develop a fast, selective and sensitive analytical method that combined the QuEChERS high throughput attributes with an extended characterization of PAHs in high-fat bio-matrices. Using two developed modified QuEChERS methods, three high fat salmon were characterized for 33 PAHs. The fat profile ranged from 3–11% fat; the highest known values reported for a QuEChERS based PAH extraction method.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Chemicals and food products

A stock solution of 33 PAHs and substituted PAHs was prepared by combining 16 EPA priority pollutant PAHs, a custom PAH mix and individual PAHs and diluting to volume with iso-octane (see Table 1). In addition to EPA priority pollutant PAH residues, selected PAHs included retene for use as a marker of certain types of wood combustion material (1), substituted PAHs due to high levels reported in smoked fish (7) and dibenzo[a,l]pyrene because of its recent identification in NIST SRMs associated with urban combustion pollution (26). Furthermore, exposure to these compounds has been associated with an increased risk for developing adverse health effects (26–27). All pre-made mixtures and individual PAHs were purchased from AccuStandard Inc. (New Haven, CT) and were guaranteed to be greater than 97% pure. Working standards were prepared by dilution of the stock standard with iso-octane and stored in the dark at 4 °C.

Table 1.

Retention times, monitored quantitation and confirmation ions, and instrument detection limits (IDL) for 33 PAHs by GC-MS

| PAH | Corresponding chromatogram # | DB5 Rt (min) | Target compound monitored SIM ions (m/z) | r2 | IDLa (pg/μL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quant | Confirm | |||||

| Perylene-D12 | ISTD 1 | 25.72 | 264 | 260, 265 | ||

| Naphthalene | 1 | 8.77 | 128 | 127, 129 | 0.999 | 1 |

| 2-Methylnaphthalene | 2 | 10.30 | 142 | 141, 115 | 0.999 | 1 |

| 1-Methylnaphthalene | 3 | 10.52 | 142 | 141, 115 | 0.999 | 1 |

| 1,6-Dimethylnaphthalene | 4 | 11.97 | 156 | 141, 153 | 0.999 | 1 |

| Acenaphthylene | 5 | 12.34 | 152 | 151, 150 | 0.999 | 1 |

| 1,2-Dimethylnaphthalene | 6 | 12.35 | 141 | 156, 115 | 0.999 | 1 |

| Acenaphthene | 7 | 12.75 | 153 | 154, 152 | 0.999 | 1 |

| Fluorene | 8 | 13.96 | 166 | 165, 167 | 0.999 | 1 |

| Dibenzothiophene | 9 | 15.91 | 184 | 139, 185 | 0.999 | 1 |

| Phenanthrene | 10 | 16.21 | 178 | 176, 179 | 0.999 | 5 |

| Anthracene | 11 | 16.33 | 178 | 176, 179 | 0.996 | 5 |

| 2-Methylphenanthrene | 12 | 17.42 | 192 | 191, 165 | 0.998 | 5 |

| 2-Methylanthracene | 13 | 17.53 | 192 | 191, 165 | 0.992 | 5 |

| 1-Methylphenanthrene | 14 | 17.67 | 192 | 191, 165 | 0.999 | 5 |

| 9-Methylanthracene | 15 | 18.00 | 192 | 191, 165 | 0.999 | 5 |

| 3,6-Dimethylphenanthrene | 16 | 18.43 | 206 | 191, 205 | 0.999 | 1 |

| Fluoranthene | 17 | 19.01 | 202 | 203, 200 | 0.999 | 1 |

| 2,3-Dimethylanthracene | 18 | 19.09 | 206 | 191, 205 | 0.996 | 5 |

| Pyrene | 19 | 19.53 | 202 | 200, 203 | 0.999 | 1 |

| 9,10-Dimethylanthracene | 20 | 19.60 | 206 | 191, 205 | 0.998 | 1 |

| Retene | 21 | 20.27 | 219 | 220, 234 | 0.999 | 1 |

| 1-Methylpyrene | 22 | 20.86 | 216 | 215, 217 | 0.999 | 1 |

| Benz[a]anthracene | 23 | 22.37 | 228 | 226, 229 | 0.983 | 5 |

| Chrysene | 24 | 22.45 | 228 | 226, 229 | 0.994 | 1 |

| 6-Methylchrysene | 25 | 23.49 | 242 | 241, 226 | 0.999 | 1 |

| Benzo[b]fluoranthene | 26 | 24.78 | 252 | 253, 250 | 0.994 | 1 |

| Benzo[k]fluoranthene | 27 | 24.85 | 252 | 253, 250 | 0.992 | 1 |

| Benzo[e]pyrene | 28 | 25.44 | 252 | 250, 253 | 0.999 | 1 |

| Benzo[a]pyrene | 29 | 25.57 | 252 | 253, 250 | 0.996 | 1 |

| Indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene-D12 | ISTD 2 | 28.78 | 288 | 284, 289 | ||

| Indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene | 30 | 28.86 | 276 | 277, 274 | 0.997 | 1 |

| Dibenz[a,h]anthracene | 31 | 28.95 | 278 | 279, 276 | 0.998 | 5 |

| Benzo[g,h,i]perylene | 32 | 29.63 | 276 | 277, 274 | 0.999 | 1 |

| Dibenzo[a,l]pyrene | 33 | 33.91 | 302 | 300, 303 | 0.998 | 1 |

IDL assigned when PAH lowest abundant confirmation ion S/N > 3 for standards prepared in iso-octane.

Perylene-D12 and indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene-D12 were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. (Andover, MA) and used as internal standards for instrumental quantitation. High purity Optima acetonitrile, ethyl acetate, acetone, hexane and pesticide grade iso-octane were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) and used throughout the study. Glacial acetic acid was from J.T. Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ) and high purity water was supplied by a Barnstead EASYpure UV compact ultrapure water system (Dubuque, IA). Commercially available Sampli-Q QuEChERS AOAC (6 g of magnesium sulfate, 1.5 g sodium acetate/package) and EN (4 g of magnesium sulfate, 1 g of sodium chloride, 1 g sodium citrate, 0.5 g sodium hydrogencitrate sesquihydrate/package) extraction salts and 2 mL AOAC fatty sample dispersive SPE tubes (50 mg PSA, 50 mg C18EC and 150 mg magnesium sulfate) were obtained from Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA).

Three commercially available smoked salmon fillets (~113g wet weight) were purchased from local grocery stores. Salmon fat content was determined and reported by the manufacturer in the product nutrition label. Salmon were homogenized via freeze fracture using a Robot Coupe BlixerR 2 food processor (Ridgeland, MS) and liquid N2, transferred into amber glass screw-top jars and stored in the dark at −20 °C. All sample preparation equipment and machinery were washed with soap and water and rinsed with high purity water, acetone and hexane prior to use and between samples.

GC-MS analysis

All standards and samples were analyzed using an Agilent 5975B GC-MS (Santa Clara, CA) with electron impact ionization (70 eV) utilizing selective ion monitoring (SIM) in positive ion mode and a DB-5MS column (30 m length, 0.25 μm film thickness, 0.25 mm I.D., Agilent J&W). The instrument injection port was operated in the pulsed splitless mode, fitted with a 2 mm glass liner with deactivated glass wool and delivered a 1 μL injection to an inlet maintained at 300 °C. Chromatography of PAHs was achieved using the following program at a column flow rate of 1 mL/min using helium as the carrier gas: the initial oven temperature was 70 °C, 1 min hold, ramp to 300 °C at 10 °C/min, 4 min hold, ramp to 310 °C at 10 °C/min, 7 min hold for a total run time of 36 min. Mass spectrometer transfer line, source and quadrapole temperatures were 280 °C, 230 °C and 150 °C respectively. PAH SIM ions are presented in Table 1 along with retention times and coefficients of determination.

Sample preparation and fortification

Sample preparation followed a modified QuEChERS methodology (14). For PAH spike and recovery experiments, 1 g of salmon homogenate (wet weight) was weighed into a 15 mL conical centrifuge tube using a Brinkmann Instruments Inc. Sartorius 1202 MP analytical balance (Westbury, NY) and allowed to come to room temperature. Spiked samples were fortified with 50 μL of a 10 μg/mL composite of 33 PAHs (500 ng/g) directly onto the fish matrix and allowed to acclimate for 2 minutes. Matrix blanks were prepared similarly but were not fortified. Samples were then extracted by one of four methods.

Sample extraction procedures – see Table 2 for summary

Table 2.

Summary of tested QuEChERS extraction conditions for recovery of 33 PAHs from smoked salmon.

| Extraction scheme | Extraction solvent (vol) | Extraction salt

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Type and composition (g) | Amount used (g) | ||

| E1 | 1% (v/v) acetic acid in acetonitrile (5 mL) | AOACa - MgSO4 (6g),NaC2H3O2 (1.5 g) | 2.5 |

| E2 | Acetonitrile (2 mL) | ENb -MgSO4 (4 g), NaCl (1 g), NaC6H7O7 (1 g), Na2C6H8O8 (0.5 g)c | 1.3 |

| E3 | 2:2:1 (v/v/v) acetone, ethyl acetate, iso-octane (2 mL) | AOAC | 1.3 |

| E4 | 2:2:1 (v/v/v) acetone, ethyl acetate, iso-octane (2 mL) | EN | 1.3 |

Commercially availableextraction salt packets developed by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC).

Commercially available extraction salt packets developed by the European Committee for Standardization (EN).

Na2C6H8O8 = sodium hydrogencitrate sesquihydrate.

Four extraction methods (E1, E2, E3 and E4) were used in the study. Schemes E1 and E2 represent methods commonly referred to as the ‘traditional QuEChERS methods’ and employ AOAC and EN salts respectively. Full details for extraction schemes E1 and E2 are described elsewhere (20, 22–24). Briefly, E1 samples received 4 mL of H2O followed by vigorous shaking/vortexing for 1 min. To this slurry was added 5 mL of 1% acetic acid in acetonitrile and the resulting mixture was mixed for 1 min. Next, 2.5 g of AOAC extraction salts were added and the mixture was shaken/vortexed for 1 min and centrifuged at 3800 g for 5 min with an Eppendorf 5810R centrifuge (Westbury, NY). E2 samples received 1 mL of H2O and were shaken/vortexed for 1 min. Then 2 mL of acetonitrile was added and the resulting mixture was mixed thoroughly for 15 min. Samples were subsequently treated with 1.3 g of EN extraction salts, shaken/vortexed for 15 min and centrifuged at 3800 g for 5 min.

Two new extraction schemes, E3 and E4, were developed as modifications to E1 and E2. Scheme E3 and E4 samples received 1 mL of H2O followed by vigorous shaking/vortexing for 1 min. The resulting slurries were treated with 2 mL of a solution of high purity acetone, ethyl acetate and iso-octane (2:2:1; v/v/v) and thoroughly mixed for 5 min. Then, samples were treated with either 1.3 g of AOAC or EN extraction salts, shaken/vortexed for 5 min and centrifuged at 3800 g for 5 min. Samples treated with AOAC and EN salts are denoted as schemes E3 and E4 respectively.

Sample clean-up and internal standard addition procedure

All extracted samples were subject to dispersive solid-phase extraction as it has been previously demonstrated to improve PAH recoveries in shrimp and sample drying (14, 21). Extracts (1 mL) were aliquoted into commercially available 2 mL Sampli-Q AOAC fatty sample dispersive SPE tubes, shaken/vortexed for 5 min and centrifuged at 13,600 g for 5 min with an Eppendorf 5415C microcentrifuge (Westbury, NY). Aliquots of the resulting supernatant (200 μL) were transferred to autosampler vials fitted with small volume inserts, spiked with perylene-D12 and indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene-D12 internal standards, vortex mixed and stored in the dark at −20 °C until analysis. All spike-recovery experiments and matrix blank determinations were conducted in replicates of four and three respectively.

PAH and substituted PAH quantification

Following extraction, cleanup and internal standard addition, all samples were quantified for PAHs and substituted PAHs using GC-MS. Purchased native standards were used to accurately identify and quantify PAHs and their substituted derivatives. Analyte concentrations were determined from calibration curves of relative response factors of analytes to internal standards. Calibration curves were generated from seven calibration standards prepared in iso-octane with a concentration range of 1–1000 pg/μL. Extractions of non-spiked salmon matrix were performed in replicate (n = 3) for PAH background determination. Method recoveries (%) were subsequently background subtracted.

Quality assurance/control

Each analytical batch contained a minimum of 15% quality control samples, including solvent blanks, check standards and over-spikes. Instrument stability was assessed by analyzing continuing calibration verification standards every 6–8 samples. The accuracy and precision of continuing calibration verification standards were typically within ± 15% of expected values. Additionally, inter-day/batch accuracy and precision over four analytical batches run on four different days were typically within ± 10% of expected values. Finally, the presence of artifact PAHs arising from laboratory associated procedures was assessed through the analysis of laboratory reagent blanks. Parent and substituted PAH residues were not detected in any laboratory reagent blank samples.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

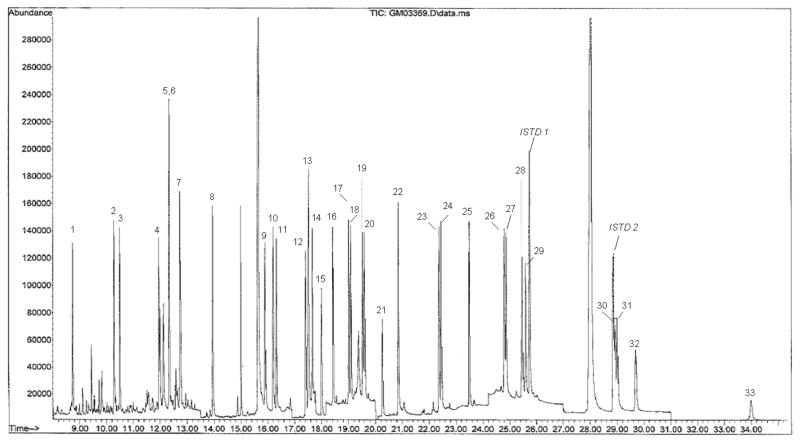

Figure 1 is an example chromatogram generated from salmon spike-recovery experiments demonstrating sufficient separation/detection of 33 PAHs and substituted PAHs by GC-MS in 36 minutes at a sample overspike concentration of 500 ng/g (wet weight). Table 1 summarizes native PAH and deuterated internal standard GC-MS instrumental parameters and detection limits. Benz[a]anthracene was the only compound that had a coefficient of determination (r2) less than 0.99 (r2 = 0.983); all others had coefficients ≥ 0.99 within the calibration range of 1 – 1000 pg/μL, demonstrating excellent method linearity. Parent and substituted PAH instrumental detection limits were assigned to PAH molecular ions when their lowest abundance confirmation ion signal-to-noise (S/N) ≥ 3 as determined by the signal-to-noise script of the Agilent MSD ChemStation data analysis software, version E (Santa Clara, CA). Samples used in the determination of instrumental detection limits were standard solutions analyzed from several batches over several days. The instrumental detection limits for quantified analytes ranged from 1 to 5 pg/μL. Analytes were considered quantitative when they calibrated with r2 ≥ 0.98, their lowest abundance confirmation ion had S/N > 3 and had reproducible and accurate quantitation (± 20% of their true value) as assessed from continuing calibration verification standards. All parent and substituted PAHs met these criteria. Sample residues that met all criteria but had S/N < 3 were designated below detection limit (BDL), while those that did not meet one or more of the above criteria were designated non-detectable (ND).

Figure 1.

Representative selective ion monitoring total ion current (TIC) for PAHs in smoked salmon with a 500 ng/g wet weight overspike. PAHs corresponding to chromatogram numbers can be found in Table 1.

Table 3 summarizes PAH spike recoveries obtained for traditional acetonitrile based QuEChERS extraction methods E1 and E2 from smoked salmon with 3, 8, and 11% fat content. Recoveries from smoked salmon using extraction scheme E1 (1% acetic acid in acetonitrile and AOAC salts) yielded low recoveries, on average less than 67%, with individual PAH recoveries typically ranging from 35 to 87%. Extraction scheme E2 (acetonitrile and EN salts) performed equally poorly, with average PAH recoveries being less than 68% and individual PAH recoveries ranging from 24 to 88%. Both extraction scheme E1 and E2 were especially poor at recovering 2-, 3-, 5- and 6-ring PAHs, where average recoveries across this subgroup of PAHs were 57% and 56% respectively.

Table 3.

Traditional QuEChERS method performance in recovering 33 PAHs (mean ± RSD; n = 4) from increasing fat content smoked salmon fortified at 500 ng/g wet weight.

| PAH | Recovery (%)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1a |

E2a |

|||||

| 3%b | 8% | 11% | 3% | 8% | 11% | |

| Naphthalene | 39.6 ± 47.7 | 30.0 ± 5.5 | 45.5 ± 8.4 | 34.3 ± 45.6 | 38.7 ± 5.8 | 43.3 ± 12.7 |

| 2-Methylnaphthalene | 48.8 ± 32.2 | 42.5 ± 2.2 | 53.2 ± 5.3 | 42.2 ± 35.1 | 47.5 ± 5.0 | 49.6 ± 10.4 |

| 1-Methylnaphthalene | 47.0 ± 29.5 | 44.1 ± 0.9 | 54.2 ± 5.7 | 43.1 ± 31.9 | 47.5 ± 3.0 | 50.3 ± 9.5 |

| 1,6-Dimethylnaphthalene | 55.0 ± 21.9 | 51.2 ± 0.5 | 58.5 ± 3.9 | 48.8 ± 28.2 | 52.0 ± 3.6 | 54.2 ± 7.8 |

| 1,2-Dimethylnaphthalene | 62.3 ± 26.5 | 61.4 ± 3.8 | 60.7 ± 3.1 | 49.7 ± 26.8 | 56.6 ± 1.8 | 55.4 ± 7.8 |

| Acenaphthylene | 56.5 ± 21.9 | 57.1 ± 2.1 | 58.2 ± 4.5 | 50.2 ± 25.0 | 58.0 ± 2.3 | 55.6 ± 6.9 |

| Acenaphthene | 56.1 ± 21.2 | 55.0 ± 1.5 | 56.9 ± 3.7 | 47.8 ± 25.5 | 55.1 ± 1.7 | 54.0 ± 7.5 |

| Fluorene | 60.6 ± 18.5 | 62.7 ± 1.5 | 65.0 ± 3.6 | 54.5 ± 22.0 | 64.6 ± 1.7 | 61.8 ± 5.6 |

| Dibenzothiophene | 62.7 ± 12.7 | 68.1 ± 2.1 | 62.8 ± 2.7 | 58.9 ± 15.0 | 71.4 ± 1.6 | 62.4 ± 4.0 |

| Phenanthrene | 65.4 ± 13.4 | 74.2 ± 2.0 | 66.8 ± 2.3 | 63.0 ± 12.2 | 76.0 ± 2.0 | 66.0 ± 3.5 |

| Anthracene | 71.0 ± 10.2 | 82.0 ± 1.6 | 73.6 ± 2.5 | 67.1 ± 13.3 | 82.4 ± 2.0 | 70.3 ± 3.6 |

| 2-Methylphenanthrene | 73.0 ± 8.1 | 83.2 ± 1.8 | 70.8 ± 3.0 | 71.5 ± 8.6 | 85.1 ± 1.6 | 71.9 ± 2.7 |

| 2-Methylanthracene | 71.1 ± 10.1 | 66.3 ± 44.5 | 33.9 ± 5.3 | 73.4 ± 11.8 | 93.5 ± 2.3 | 74.4 ± 3.8 |

| 1-Methylphenanthrene | 72.8 ± 8.8 | 84.6 ± 1.0 | 69.0 ± 3.7 | 66.9 ± 8.4 | 79.3 ± 1.1 | 68.3 ± 2.5 |

| 9-Methylanthracene | 76.3 ± 6.2 | 83.7 ± 2.2 | 73.2 ± 1.9 | 70.8 ± 8.5 | 83.6 ± 1.3 | 70.0 ± 2.6 |

| 3,6-Dimethylphenanthrene | 74.0 ± 5.2 | 77.0 ± 1.4 | 68.4 ± 2.5 | 68.6 ± 7.9 | 77.9 ± 1.3 | 66.4 ± 2.5 |

| Fluoranthene | 75.0 ± 4.2 | 84.4 ± 2.1 | 69.6 ± 2.4 | 72.1 ± 5.3 | 85.3 ± 0.4 | 69.1 ± 1.3 |

| 2,3-Dimethylanthracene | 74.1 ± 3.8 | 79.8 ± 1.8 | 67.8 ± 2.6 | 70.7 ± 6.2 | 80.3 ± 1.0 | 66.2 ± 2.1 |

| 9,10-Dimethylanthracene | 76.7 ± 3.3 | 79.3 ± 2.1 | 70.6 ± 2.4 | 72.4 ± 5.1 | 79.0 ± 0.8 | 66.7 ± 1.8 |

| Pyrene | 73.2 ± 4.5 | 83.4 ± 2.7 | 67.1 ± 1.9 | 71.1 ± 4.5 | 82.1 ± 0.5 | 65.8 ± 1.4 |

| Retene | 73.1 ± 2.9 | 74.5 ± 2.0 | 66.1 ± 3.6 | 69.4 ± 5.2 | 76.0 ± 1.1 | 64.4 ± 1.7 |

| 1-Methylpyrene | 69.2 ± 2.5 | 78.4 ± 1.9 | 65.2 ± 7.6 | 66.8 ± 3.7 | 77.0 ± 0.5 | 63.9 ± 1.5 |

| Benz[a]anthracene | 87.6 ± 3.8 | 96.0 ± 2.0 | 80.0 ± 2.7 | 88.9 ± 2.8 | 95.9 ± 0.4 | 80.4 ± 0.7 |

| Chrysene | 75.9 ± 3.3 | 83.6 ± 2.2 | 69.5 ± 2.7 | 77.4 ± 2.8 | 83.0 ± 0.6 | 69.7 ± 0.8 |

| 6-Methylchrysene | 73.2 ± 2.0 | 72.5 ± 2.0 | 62.8 ± 2.2 | 71.7 ± 3.8 | 71.9 ± 0.6 | 62.9 ± 0.9 |

| Benzo[b]fluoranthene | 68.6 ± 3.8 | 70.8 ± 2.3 | 61.4 ± 2.9 | 73.4 ± 2.4 | 70.9 ± 1.1 | 63.6 ± 0.8 |

| Benzo[k]fluoranthene | 66.2 ± 4.5 | 68.4 ± 2.0 | 59.3 ± 3.8 | 72.6 ± 2.6 | 69.1 ± 0.9 | 62.2 ± 1.1 |

| Benzo[e]pyrene | 66.4 ± 3.1 | 65.3 ± 2.1 | 57.1 ± 2.8 | 65.1 ± 2.3 | 63.2 ± 0.8 | 56.6 ± 1.2 |

| Benzo[a]pyrene | 64.0 ± 4.4 | 63.8 ± 2.0 | 55.6 ± 3.0 | 67.0 ± 2.5 | 60.8 ± 1.0 | 56.4 ± 1.5 |

| Indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene | 53.2 ± 4.0 | 54.6 ± 1.3 | 47.6 ± 2.5 | 62.0 ± 1.6 | 53.8 ± 1.1 | 51.3 ± 1.6 |

| Dibenz[a,h]anthracene | 63.5 ± 2.9 | 66.6 ± 0.5 | 55.6 ± 2.6 | 68.9 ± 1.2 | 62.7 ± 0.6 | 59.0 ± 1.4 |

| Benzo[g,h,i]perylene | 51.7 ± 2.2 | 47.7 ± 1.6 | 44.0 ± 2.7 | 56.7 ± 1.5 | 47.2 ± 0.4 | 46.2 ± 2.0 |

| Dibenzo[a,l]pyrene | 62.6 ± 4.5 | 34.2 ± 4.2 | 45.0 ± 8.7 | 71.5 ± 1.3 | 24.5 ± 8.6 | 46.7 ± 2.0 |

| Average recovery across all PAHs (%) | 66 | 67 | 61 | 64 | 68 | 61 |

See Table 2 for method specifics.

Fat content

Variant QuEChERS solvent systems have been described for the analysis of pesticide residues in fruits (14, 28). Additionally, the individual and combined performance of various ratios of ethyl acetate, acetone, hexane, methylene chloride, acetonitrile, cyclohexane and iso-octane have been reported for multiple residue pesticide methods and EPA methods for extraction of nonvolatile and semivolatile organic compounds from solid and semi-sold samples (10, 12–13, 28). Of interest were solvent systems with improved selectivity for non-polar PAH residues and that were lower in cost than acetonitrile. It was found that a three-component variant solvent system of acetone, ethyl acetate and iso-octane (2:2:1; v/v/v) met these criteria.

Table 4 summarizes PAH recoveries obtained from smoked salmon using modified QuEChERS extraction schemes E3 and E4. Extraction scheme E3 (acetone, ethyl acetate, iso-octane and AOAC salts) led to good recoveries, on average 90% over all fish tested. Notable performance gains were made for 2-, 3- and 5-ring PAHs where recoveries were improved 50–200%, while recoveries of 4- and 6-ring PAHs were slightly improved by ~ 30–45% as compared to acetonitrile. Extraction scheme E4 (acetone, ethyl acetate, iso-octane and EN salts) performed equally well, with an average PAH recovery of 87% across all fish and individual PAHs displaying the same range of improvement as extraction scheme E3. Additionally, both extraction scheme E3 and E4 displayed good extraction precision with relative standard deviations typically less than 10% for all fish tested.

Table 4.

Modified QuEChERS method performance in recovering 33 PAHs (mean ± RSD; n = 4) from increasing fat content smoked salmon fortified at 500 ng/g wet weight.

| PAH | Recovery (%)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E3a |

E4a |

|||||

| 3%b | 8% | 11% | 3% | 8% | 11% | |

| Naphthalene | 72.4 ± 2.5 | 98.3 ± 3.4 | 76.4 ± 1.6 | 73.4 ± 7.0 | 96.0 ± 3.1 | 70.0 ± 3.4 |

| 2-Methylnaphthalene | 77.5 ± 3.1 | 102.7 ± 2.5 | 82.3 ± 1.8 | 79.1 ± 7.4 | 96.5 ± 2.2 | 76.0 ± 2.7 |

| 1-Methylnaphthalene | 73.8 ± 3.5 | 98.7 ± 2.7 | 80.5 ± 2.5 | 75.6 ± 7.3 | 94.6 ± 3.7 | 73.6 ± 2.1 |

| 1,6-Dimethylnaphthalene | 80.9 ± 3.5 | 107.4 ± 2.6 | 85.6 ± 1.6 | 83.2 ± 7.0 | 102.1 ± 3.7 | 77.9 ± 2.0 |

| 1,2-Dimethylnaphthalene | 81.1 ± 2.4 | 108.0 ± 3.1 | 81.2 ± 2.2 | 82.9 ± 6.1 | 102.3 ± 3.4 | 74.6 ± 2.2 |

| Acenaphthylene | 77.7 ± 3.6 | 103.0 ± 2.5 | 80.3 ± 1.3 | 80.0 ± 6.9 | 98.0 ± 3.5 | 73.1 ± 1.7 |

| Acenaphthene | 76.8 ± 3.5 | 103.4 ± 2.6 | 79.2 ± 1.4 | 78.6 ± 7.0 | 97.4 ± 3.2 | 71.3 ± 1.8 |

| Fluorene | 81.9 ± 3.7 | 107.9 ± 2.8 | 86.9 ± 1.5 | 84.1 ± 7.0 | 102.2 ± 3.7 | 79.8 ± 1.9 |

| Dibenzothiophene | 79.2 ± 3.8 | 105.2 ± 2.4 | 82.6 ± 1.5 | 82.3 ± 6.9 | 100.1 ± 4.1 | 76.9 ± 1.8 |

| Phenanthrene | 80.5 ± 3.8 | 107.8 ± 2.8 | 85.1 ± 1.6 | 82.3 ± 7.2 | 101.9 ± 3.8 | 78.4 ± 2.0 |

| Anthracene | 89.9 ± 4.2 | 120.4 ± 2.8 | 95.4 ± 1.6 | 92.7 ± 7.2 | 113.5 ± 4.0 | 87.8 ± 2.0 |

| 2-Methylphenanthrene | 88.2 ± 4.0 | 122.0 ± 2.8 | 88.8 ± 12.0 | 90.9 ± 6.8 | 113.7 ± 3.9 | 85.8 ± 2.1 |

| 2-Methylanthracene | 76.6 ± 6.8 | 128.7 ± 12.5 | 84.5 ± 13.4 | 93.7 ± 4.0 | 75.1 ± 5.4 | 79.9 ± 2.4 |

| 1-Methylphenanthrene | 85.0 ± 3.9 | 115.1 ± 1.8 | 92.5 ± 1.5 | 88.6 ± 8.2 | 111.2 ± 3.6 | 86.2 ± 2.4 |

| 9-Methylanthracene | 90.7 ± 3.9 | 117.4 ± 2.4 | 95.6 ± 1.4 | 92.8 ± 7.4 | 110.7 ± 3.7 | 87.9 ± 1.5 |

| 3,6-Dimethylphenanthrene | 85.3 ± 3.2 | 108.9 ± 2.6 | 89.2 ± 1.5 | 88.1 ± 7.8 | 104.3 ± 3.7 | 84.5 ± 1.7 |

| Fluoranthene | 84.6 ± 3.6 | 111.9 ± 2.7 | 88.5 ± 2.0 | 86.4 ± 6.9 | 105.5 ± 3.6 | 81.1 ± 1.9 |

| 2,3-Dimethylanthracene | 91.4 ± 3.7 | 115.4 ± 2.8 | 94.9 ± 1.8 | 93.7 ± 6.9 | 108.3 ± 3.9 | 88.9 ± 1.7 |

| 9,10-Dimethylanthracene | 89.9 ± 3.3 | 113.6 ± 2.3 | 94.6 ± 1.6 | 91.8 ± 7.0 | 107.4 ± 3.8 | 87.8 ± 1.9 |

| Pyrene | 84.2 ± 3.8 | 117.0 ± 2.6 | 87.8 ± 3.3 | 86.2 ± 6.7 | 106.0 ± 3.1 | 79.9 ± 2.4 |

| Retene | 90.1 ± 3.3 | 112.9 ± 2.5 | 97.0 ± 1.7 | 92.2 ± 6.4 | 106.4 ± 3.7 | 90.2 ± 1.8 |

| 1-Methylpyrene | 83.5 ± 3.3 | 106.8 ± 2.4 | 92.3 ± 1.7 | 84.2 ± 7.3 | 100.6 ± 3.5 | 83.2 ± 1.7 |

| Benz[a]anthracene | 102.2 ± 3.9 | 130.4 ± 2.6 | 106.0 ± 1.5 | 105.1 ± 6.9 | 122.6 ± 4.0 | 98.1 ± 1.9 |

| Chrysene | 89.8 ± 3.8 | 114.1 ± 2.8 | 92.9 ± 1.6 | 92.1 ± 6.9 | 107.1 ± 3.9 | 86.0 ± 1.8 |

| 6-Methylchrysene | 82.7 ± 2.8 | 98.9 ± 2.4 | 84.6 ± 1.5 | 84.5 ± 7.5 | 93.6 ± 3.7 | 79.3 ± 2.1 |

| Benzo[b]fluoranthene | 87.2 ± 3.9 | 97.1 ± 1.9 | 85.9 ± 1.6 | 89.5 ± 6.3 | 92.4 ± 3.8 | 80.3 ± 2.2 |

| Benzo[k]fluoranthene | 87.9 ± 4.2 | 96.7 ± 0.7 | 85.7 ± 1.6 | 89.6 ± 5.8 | 92.4 ± 4.1 | 79.8 ± 2.6 |

| Benzo[e]pyrene | 78.3 ± 3.0 | 83.4 ± 1.6 | 75.4 ± 1.0 | 79.6 ± 6.3 | 80.7 ± 2.8 | 70.3 ± 1.4 |

| Benzo[a]pyrene | 85.3 ± 3.3 | 89.2 ± 1.7 | 82.0 ± 1.0 | 87.4 ± 6.7 | 85.4 ± 3.2 | 76.2 ± 1.2 |

| Indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene | 80.1 ± 2.3 | 82.5 ± 2.6 | 79.6 ± 2.5 | 83.5 ± 6.1 | 77.9 ± 4.4 | 72.9 ± 1.1 |

| Dibenz[a,h]anthracene | 83.2 ± 2.5 | 84.0 ± 2.3 | 81.4 ± 1.4 | 86.6 ± 6.3 | 79.6 ± 4.3 | 74.9 ± 1.3 |

| Benzo[g,h,i]perylene | 74.1 ± 1.7 | 69.5 ± 2.9 | 68.1 ± 1.9 | 76.5 ± 5.1 | 67.2 ± 3.6 | 61.9 ± 0.4 |

| Dibenzo[a,l]pyrene | 67.6 ± 2.6 | 40.5 ± 10.1 | 48.5 ± 3.5 | 77.5 ± 4.9 | 52.4 ± 4.4 | 36.0 ± 3.0 |

| Average recovery across all PAHs (%) | 83 | 104 | 85 | 86 | 97 | 78 |

See Table 2 for method specifics.

Fat content

It is well understood that the planar hydrophobic chemical structure of PAHs leads to their association with fatty components of biological matrices (i.e. waxes, lipids, steroids and pigments). Extraction conditions that disrupt these associations should give rise to enhanced extraction performance. A solvent’s ability to disrupt interactions may be assessed by comparison of solvent and PAH octanol-water partition coefficients (log KOW), where solvents with coefficients similar to PAHs should display enhanced selectivity. The log KOW for PAHs used in this study ranged from 3.3 for naphthalene to 7.7 for dibenzo[a,l]pyrene. Acetonitrile has a reported log KOW = −0.34, while values for acetone, ethyl acetate and iso-octane are −0.24, 0.73 and 4.1 respectively. It has also been demonstrated that extraction of various food stuffs with acetonitrile resulted in limited extraction of hydrophobic matrix components (14, 29). This information coupled to our results suggests that the three component extraction solvent used in extraction schemes E3 and E4 possesses physicochemical characteristics that allow it to interact more intimately with fatty fish matrices. At the molecular level, extraction with acetone, ethyl acetate and iso-octane may lead to improved recoveries by allowing water miscible acetone and ethyl acetate to recover PAHs trapped in water-sealed matrix pores and making them available for transfer to iso-octane.

It is also known that increased extraction temperatures can disrupt analyte-matrix interactions by decreasing the activation energy required for analyte desorption processes and decreasing solvent viscosity, facilitating better solvent-matrix penetration (12). It was found that addition of magnesium sulfate containing extraction salts generated sample extraction temperatures of 45 – 50°C that persisted for the duration of the extraction/partition procedure (data not shown). Extraction temperatures in the range observed have been by reported by others and should increase solvent capacity for PAHs (12, 14). The findings presented indicate that the improved extraction performance of schemes E3 and E4 likely resulted from the combined influence of enhanced solvent selectivity and elevated sample extraction temperatures.

In order to evaluate the effectiveness and utility of the modified QuEChERS methods developed in this study, a comparison to other published extraction techniques is presented (Table 5) (13). Compared to soxhIet extraction with hexane, it was found that modified QuEChERS methods substantially improved average recovery of all 15 PAHs by roughly 38% and led to individual gains of 50–125% for naphthalene, anthracene, benz[a]anthracene, benzo[k]fluoranthene and dibenz[a,h]anthracene. Similar overall improvements were demonstrated when compared to accelerated solvent extraction (ASE) with hexane. Interestingly, the performance of modified QuEChERS methods was comparable to a validated dichloromethane and acetonitrile (1:1; v/v) based ASE extraction method in average recovery across all PAHs. However, modified QuEChERS methods showed improved recoveries in lower molecular weight PAHs, while ASE performed better at recovering benzo[g,h,i]perylene. Estimated method detection limits (MDL) for modified QuEChERS methods are presented in Table 6 in relation to FDA PAH levels of concern in shrimp, crab, oysters and finfish (25). MDLs were defined as the product of the analyte instrument detection and the method dilution factor, which was a factor of 2 in this case. MDLs were all well below levels of concern in these food stuffs, demonstrating the potential utility of the developed methods. If needed, additional method sensitivity could be achieved through the introduction of a solvent reduction procedure prior to instrumental analysis.

Table 5.

Modified QuEChERS extraction performance (% recovery ± SD) compared to literature reported soxhlet and accelerated solvent extraction (ASE) in recovering 15 PAHs from fish tissues.

| PAH | Recovery (%)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soxhlet with hexanea | ASE with hexanea | ASE with CH2Cl2:ACN (9:1)a | Modified QuEChERS E3b | Modified QuEChERS E4c | |

| Naphthalene | 51 ± 6 | 58 ± 5 | 62 ± 6 | 82 ± 12 | 80 ± 13 |

| Acenaphthylene | 84 ± 7 | 88 ± 9 | 76 ± 5 | 87 ± 12 | 84 ± 12 |

| Acenanphthene | 68 ± 4 | 67 ± 6 | 69 ± 4 | 86 ± 13 | 82 ± 12 |

| Fluorene | 77 ± 6 | 81 ± 7 | 77 ± 10 | 92 ± 12 | 89 ± 11 |

| Phenanthrene | 91 ± 12 | 71 ± 11 | 93 ± 8 | 91 ± 13 | 88 ± 11 |

| Anthracene | 66 ± 5 | 61 ± 5 | 81 ± 7 | 102 ± 14 | 98 ± 12 |

| Fluoranthene | 71 ± 9 | 73 ± 9 | 101 ± 7 | 95 ± 13 | 91 ± 12 |

| Pyrene | 69 ± 7 | 68 ± 6 | 92 ± 5 | 96 ± 16 | 91 ± 12 |

| Benz[a]anthracene | 70 ± 5 | 68 ± 4 | 96 ± 11 | 113 ± 13 | 109 ± 12 |

| Chrysene | 44 ± 3 | 53 ± 4 | 93 ± 9 | 99 ± 12 | 95 ± 10 |

| Benzo[k]fluoranthene | 45 ± 10 | 54 ± 11 | 89 ± 5 | 90 ± 5 | 87 ± 7 |

| Benzo[a]pyrene | 74 ± 14 | 57 ± 6 | 79 ± 8 | 85 ± 4 | 83 ± 6 |

| Indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene | 56 ± 6 | 56 ± 12 | 81 ± 3 | 81 ± 2 | 78 ± 6 |

| Dibenz[a,h]anthracene | 55 ± 8 | 48 ± 8 | 84 ± 8 | 83 ± 2 | 80 ± 6 |

| Benzo[g,h,i]perylene | 61 ± 11 | 67 ± 10 | 85 ± 7 | 71 ± 3 | 69 ± 7 |

| Average recovery across all PAHs (%) | 65 | 65 | 84 | 90 | 87 |

Values originally reported by Wang et al. (1999); n = 4 replicates for each extraction method.

Values represent mean recovery across all three fat level fish tested by extraction method E3; n = 12.

Values represent mean recovery across all three fat level fish tested by extraction method E4; n = 12.

Table 6.

Comparison of FDA PAH levels of concern in relation to estimated modified QuEChERS method detection limits (MDL).

| PAH | FDA levels of concern (μg/g)

|

Modified QuEChERS MDL (ug/g)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shrimp and craba | Oystera | Finfisha | ||

| Naphthalene | 123 | 133 | 32.7 | 0.002 |

| 2-Methylnaphthalene | NAc | NA | NA | 0.002 |

| 1-Methylnaphthalene | NA | NA | NA | 0.002 |

| 1,6-Dimethylnaphthalene | NA | NA | NA | 0.002 |

| Acenaphthylene | NA | NA | NA | 0.002 |

| 1,2-Dimethylnaphthalene | NA | NA | NA | 0.002 |

| Acenaphthene | NA | NA | NA | 0.002 |

| Fluorene | 246 | 267 | 65.3 | 0.002 |

| Dibenzothiophene | NA | NA | NA | 0.002 |

| Phenanthrene | 1846d | 2000d | 490d | 0.010 |

| Anthracene | NA | NA | NA | 0.010 |

| 2-Methylphenanthrene | NA | NA | NA | 0.010 |

| 2-Methylanthracene | NA | NA | NA | 0.010 |

| 1-Methylphenanthrene | NA | NA | NA | 0.010 |

| 9-Methylanthracene | NA | NA | NA | 0.010 |

| 3,6-Dimethylphenanthrene | NA | NA | NA | 0.002 |

| Fluoranthene | 246 | 267 | 65.3 | 0.002 |

| 2,3-Dimethylanthracene | NA | NA | NA | 0.010 |

| Pyrene | 185 | 200 | 49.0 | 0.002 |

| 9,10-Dimethylanthracene | NA | NA | NA | 0.002 |

| Retene | NA | NA | NA | 0.002 |

| 1-Methylpyrene | NA | NA | NA | 0.002 |

| Benz[a]anthracene | 1.32 | 1.43 | 0.35 | 0.010 |

| Chrysene | 132 | 143 | 35.0 | 0.002 |

| 6-Methylchrysene | NA | NA | NA | 0.002 |

| Benzo[b]fluoranthene | 1.32 | 1.43 | 0.35 | 0.002 |

| Benzo[k]fluoranthene | 13.2 | 14.3 | 3.5 | 0.002 |

| Benzo[e]pyrene | NA | NA | NA | 0.002 |

| Benzo[a]pyrene | 0.132 | 0.143 | 0.035 | 0.002 |

| Indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene | 1.32 | 1.43 | 0.35 | 0.002 |

| Dibenz[a,h]anthracene | 0.132 | 0.143 | 0.035 | 0.010 |

| Benzo[g,h,i]perylene | NA | NA | NA | 0.002 |

| Dibenzo[a,l]pyrene | NA | NA | NA | 0.002 |

Values obtained from U.S. FDA (2010).

MDL = IDL multiplied by a dilution factor of 2.

Levels of concern not known at time of publication.

Represents summed levels of concern for phenanthrene and anthracene.

A comparison of PAH levels measured in commercially available smoked salmon using both modified QuEChERS extraction schemes E3 and E4 is presented in Table 7. Results for the two methods were quite similar across all fish in terms of PAH profile, quantitation, extraction precision and sum of quantified PAHs (ΣPAHs). Naphthalene, 2-methylnaphthalene, 1-methylnaphthalene, phenanthrene, fluoranthene, pyrene and benzo[g,h,i]perylene were consistently detected. Anthracene was observed only in 3% fat salmon, but was not quantified because it did not meet signal-to-noise limits. Levels of individual PAHs typically fell in a range of 5–60 ng/g wet weight with fluoranthene and benzo[g,h,i]perylene displaying the lowest levels and naphthalene, 2-methylnaphthalene and pyrene consistently accounting for > 70% of total PAH mass recovered. Extraction schemes E3 and E4 also performed equally well with regards to extraction precision (RSD < 20%) and produced nearly identical ΣPAH values within and across the fat levels used. Results from this study are comparable to other studies in terms of PAH profile, range and summed residue loads and, together with spike-recovery experiments, demonstrate that choice of extraction solvent is crucial to extraction performance (6–7, 13).

Table 7.

Comparison of PAH levels (mean ng/g wet weight ± SD, n = 3) measured in commercially available smoked salmon by two new modified QuEChERS extraction schemes

| PAH | 3%a |

8%

|

11%

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E3 | E4 | E3 | E4 | E3 | E4 | |

| Naphthalene | 49.1 ± 5.9 | 52.6 ± 4.0 | 59.6 ± 2.5 | 62.9 ± 2.2 | 46.1 ± 2.7 | 48.6 ± 7.7 |

| 2-methyl-naphthalene | 24.5 ± 3.9 | 26.7 ± 2.9 | 38.5 ± 0.6 | 38.6 ± 2.3 | 15.8 ± 0.9 | 17.2 ± 3.4 |

| 1-methyl-naphthalene | 11.5 ± 1.3 | 13.0 ± 1.6 | 18.0 ± 1.5 | 17.6 ± 1.6 | 8.0 ± 0.6 | 9.0 ± 1.6 |

| Phenanthrene | 12.0 ± 1.3 | 13.8 ± 0.5 | 11.3 ± 0.2 | 12.6 ± 0.7 | 11.2 ± 0.6 | 11.2 ± 0.8 |

| Anthracene | BDLb | BDL | NDc | ND | ND | ND |

| Fluoranthene | 7.5 ± 1.1 | 9.3 ± 0.4 | 8.9 ± 0.6 | 9.1 ± 0.1 | 7.6 ± 1.7 | 8.4 ± 1.7 |

| Pyrene | 24.7 ± 6.7 | 28.5 ± 1.5 | 22.9 ± 2.7 | 28.9 ± 1.3 | 26.4 ± 6.6 | 29.4 ± 6.8 |

| Benzo[g,h,i]perylene | 7.2 ± 3.9 | 6.0 ± 0.6 | 5.4 ± 0.9 | 4.3 ± 0.9 | 6.9 ± 1.3 | 7.2 ± 1.3 |

| ΣPAHsd (ng/g wet weight) | 137 ± 11 | 150 ± 6 | 165 ± 4 | 174 ± 4 | 122 ± 8 | 131 ± 11 |

Fat content.

BDL: compound met all quantitation criteria, but S/N < 3.

ND: the compound was not detected; PAHs absent from the table were not detected.

ΣPAHs represents the summation of PAHs with levels above detection limits. PAHs absent from the table were not detected in salmon samples.

The goal of the current study was to develop and validate a multi residue method for the analysis of PAHs and their substituted derivatives in high-fat smoked salmon. The data presented strongly indicate that a QuEChERS based analytical platform implementing a three-component acetone, ethyl acetate and iso-octane extraction solvent in a 2:2:1 (v/v/v) ratio coupled to dispersive SPE sample cleanup and GC-MS is a fast, selective, efficient and precise method for the determination of PAHs in high-fat smoked fish products. The modified QuEChERS methods described show good potential for use in monitoring levels of PAHs in lipid-rich fish.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

The project described was supported by Award Number P42 ES016465 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences or the National Institute of Health.

The authors thank Dr. Wendy Hillwalker, Mr. Ricky Scott, Dr. Jeremy Riggle, Ms. Melissa McCartney, Ms. Kristin Pierre and Mr. Theodore Haigh for their invaluable assistance with sample preparation and chemical analyses.

Abbreviations used

- AOAC

Association of Official Analytical Chemists

- ASE

accelerated solvent extraction

- EN

European Committee for Standardization

- GC-MS

gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- PAH

polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon

- PSA

primary, secondary amine

- QuEChERS

quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged and safe

- SIM

selective ion monitoring

- SPE

solid-phase extraction

- TIC

total ion current

Literature Cited

- 1.Khalili NR, Scheff PA, Holsen TM. PAH source fingerprints for coke ovens, diesel and, gasoline engines, highway tunnels, and wood combustion emissions. Atmos Environ. 1995;29:533–542. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gustafson P, Östman C, Sällsten G. Indoor levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in homes with or without wood burning for heating. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:5074–5080. doi: 10.1021/es800304y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bignal KL, Langridge S, Zhou JL. Release of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide and particulate matter from biomass combustion in a wood-fired boiler under varying boiler conditions. Atmos Environ. 2008;42:8863–8871. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baird WM, Hooven LA, Mahadevan B. Carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts and mechanism of action. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2005;45:106–114. doi: 10.1002/em.20095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xue W, Warshawsky D. Metabolic activation of polycyclic and heterocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and DNA damage: A review. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;206:73–93. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zabik ME, et al. Pesticide residues, PCBs and PAHs in baked, charbroiled, salt boiled and smoked Great Lakes lake trout. Food Chem. 1996;55:231–239. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Afolabi OA, Adesulu EA, Oke OL. Polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons in some Nigerian preserved freshwater fish species. J Agric Food Chem. 1983;31:1083–1090. doi: 10.1021/jf00119a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wretling S, Eriksson A, Eskhult GA, Larsson B. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Swedish smoked meat and fish. J Food Compos Anal. 2010;23:264–272. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stumpe-Viksna I, Bartkevics V, Kukare A, Morozovs A. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in meat smoked with different types of wood. Food Chem. 2008;110:794–797. [Google Scholar]

- 10.United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) Method 3540C, Soxhlet Extraction. U.S. EPA; Washington, D.C: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanz-Landaluze J, et al. Accelerated extraction for determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in marine biota. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2006;384:1331–1340. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-0249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richter BE, et al. Accelerated solvent extraction: A technique for sample preparation. Anal Chem. 1996;68:1033–1039. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang G, et al. Accelerated solvent extraction and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry for determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in smoked food samples. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47:1062–1066. doi: 10.1021/jf980956h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anastassiades M, Lehotay SJ, Stajnbaher D, Schenck FJ. Fast and easy multiresidue method employing acetonitrile extraction/partitioning and dispersive solid-phase extraction for the determination of pesticide residues in produce. J AOAC Internat. 2003;86:412–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stubbings G, Bigwood T. The development and validation of a multiclass liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) procedure for the determination of veterinary drug residues in animal tissue using a QuEChERS (QUick, Easy, CHeap, Effective, Rugged and Safe) approach. Anal Chim Acta. 2009;637:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2009.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma Y, Hashi Y, Ji F, Lin JM. Determination of phthalates in fruit jellies by dispersive SPE coupled with HPLC-MS. J Sep Sci. 2010;33:251–257. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200900557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunha SC, Fernandes JO. Development and validation of a method based on a QuEChERS procedure and heart-cutting GC-MS for determination of five mycotoxins in cereal products. J Sep Sci. 2010;33:600–609. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200900695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sospedra I, Blesa J, Soriano JM, Mañes J. Use of the modified quick easy cheap effective rugged and safe sample preparation approach for the simultaneous analysis of type A- and B-trichothecenes in wheat flour. J Chromatogr A. 2010;1217:1437–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2009.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.United States Food and Drug Administration (U.S. FDA) Laboratory Information Bulletin. FDA/ORA/DFS; Washington, D.C: 2010. Determination of dioctylsulfosucinate in select seafoods using a QuEChERS extraction with liquid chromatography-triple quadrupole mass spectroscopy. ( http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ScienceResearch/FieldScience/UCM231510.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith D, Lynam K. Agilent Technologies Application Note 5990-6668EN. Agilent Technologies; Santa Clara, CA: 2010. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) analysis in fish by GC/MS using QuEChERS/dSPE sample preparation and a high efficiency DB-5ms ultra inert GC column. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smoker M, Tran K, Smith RE. Determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in shrimp. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:12101–12104. doi: 10.1021/jf1029652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.João Ramalhosa M, et al. Analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in fish: evaluation of a quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged, and safe extraction method. J Sep Sci. 2009;32:3529–3538. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200900351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cochran J. The QuEChERS approach with GC-TOFMS and GCxGCTOFMS for PAHs in oil contaminated seafood. Restek Corporation Application Poster; Florida Pesticide Residue Workshop; St. Pete Beach, Florida. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevens J, Szelewski M, Feyerherm F. Advanced analytical technologies for analyzing environmental matrixes contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbons - QuEChERS with GC-Q and GC-QQQ PAH analyzers. Agilent Technologies Application Seminar; Gulf Coast Conference; Tomball, TX. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.United States Food and Drug Administration (U.S. FDA) Laboratory Information Bulletin. FDA/ORA/DFS; Washington, D.C: 2010. Screen for the presence of polycyclic aromatic hydocarbons in select seafood using LC-fluorescence. ( http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ScienceResearch/UCM220209.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Layshock J, Simonich SM, Anderson KA. Effect of dibenzopyrene measurement on assessing air quality in Beijing air and possible implications for human health. J Environ Monitor. 2010;12:2290–2298. doi: 10.1039/c0em00057d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barron MG, Carls MG, Heintz R, Rice SD. Evaluation of fish early life-stage toxicity models of chronic embryonic exposures to complex polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon mixtures. Toxicol Sci. 2004;78:60–67. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stevens J, Zhao L, Zweigenbaum J. Modified QuEChERS: Variant solvent systems in response to the acetonitrile shortage. Agilent Technology Application Poster; 123rd AOAC International Annual Meeting; Philadelphia, PA. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lehotay SJ, Lightfield AR, Harman-Fetcho JA, Donoghue DJ. Analysis of pesticide residues in eggs by direct sample introduction/gas chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:4589–4596. doi: 10.1021/jf0104836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]