Abstract

RNA interference (RNAi) has become the cornerstone technology for studying gene function in mammalian cells. In addition, it is a promising therapeutic treatment for multiple human diseases. Virus-mediated constitutive expression of short hairpin RNA (shRNA) has the potential to provide a permanent source of silencing molecules to tissues, and it is being devised as a strategy for the treatment of liver conditions such as hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infection. Unintended interaction between silencing molecules and cellular components, leading to toxic effects, has been described in vitro. Despite the enormous interest in using the RNAi technology for in vivo applications, little is known about the safety of constitutively expressing shRNA for multiple weeks. Here we report the effects of in vivo shRNA expression, using helper-dependent adenoviral vectors. We show that gene-specific knockdown is maintained for at least 6 weeks after injection of 1 × 1011 viral particles. Nonetheless, accumulation of mature shRNA molecules was observed up to weeks 3 and 4, and then declined gradually, suggesting the buildup of mature shRNA molecules induced cell death with concomitant loss of viral DNA and shRNA expression. No evidence of well-characterized innate immunity activation (such as interferon production) or saturation of the exportin-5 pathway was observed. Overall, our data suggest constitutive expression of shRNA results in accumulation of mature shRNA molecules, inducing cellular toxicity at late time points, despite the presence of gene silencing.

Ahn and colleagues investigate the safety of constitutively expressing short hairpin RNA (shRNA), using helper-dependent adenovirus vectors for multiple weeks in vivo. Hairpin molecules were effectively processed, and gene-specific knockdown was maintained for at least 6 weeks after injection. However, accumulated mature shRNAs declined gradually after week 4, suggesting induction of cell death with concomitant loss of viral DNA and shRNA expression. No evidence of innate immune activation was observed.

Introduction

RNA interference (RNAi) is a cellular mechanism to inhibit expression of gene products in a highly specific manner. Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) is recognized by Dicer, a ribonuclease III (RNase III) enzyme, which cleaves the dsRNA into 21- to 23-nucleotide small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). On loading onto the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), one of the two strands is selected (referred to as the guide strand) and the other one is degraded (passenger strand) (Matranga et al., 2005). The RISC–siRNA complex binds to mRNA targets and triggers their degradation through Argonaute (AGO)-mediated cleavage (Liu et al., 2004; Song et al., 2004). Compared with siRNA delivery, short hairpin RNA (shRNA) expression has the advantage of providing a continuous source of silencing molecules and is a potent experimental tool for long-term gene silencing (Brummelkamp et al., 2002; McIntyre and Fanning, 2006). Constitutive synthesis of shRNA is being pursued to treat genetic conditions such as Huntington's disease (Boudreau et al., 2009), or chronic viral infections such as hepatitis B virus (Grimm and Kay, 2006; Giering et al., 2008). In addition to its use as a gene therapy treatment, constitutive shRNA expression has ample applications in gene function studies, in particular in vivo, as it allows shortening the time-consuming process of generating tissue-specific null animals. Expression of shRNA has had an enormous impact on accelerating discovery of therapeutic targets (Colombo and Moll, 2008; Ruiz et al., 2009).

The liver is a crucial tissue implicated in the control of glucose and lipid homeostasis, and the target tissue for functional studies directed at studying the molecular mechanisms leading to prevalent conditions such as type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. Adenoviruses are highly efficient vectors for delivery of genes into the liver. The feasibility of silencing gene expression in animal models, using this vector system, has been shown in multiple studies (Xia et al., 2002; Taniguchi et al., 2005; Narvaiza et al., 2006). Nevertheless, all these studies used first-generation (E1-deleted) adenoviral vectors, which are highly hepatotoxic at high doses and immunogenic, leading to clearance of transduced cells (Yang et al., 1994; Morral et al., 1997). In addition, these vectors express VA1 noncoding RNA, which inhibits microRNA processing by interfering with nuclear export and Dicer functionality (Lu and Cullen, 2004). The use of helper-dependent adenoviral vectors (also known as “gutless” or high-capacity vectors), devoid of viral genes, has been shown to overcome these problems (Schiedner et al., 1998; Morral et al., 1999; O'Neal et al., 2000). Helper-dependent adenoviruses conserve the advantages of early-generation adenovirus vectors, including high-efficiency in vivo transduction and high-level transgene expression, with the added features of long-term gene expression and negligible cytotoxicity at high doses. We have previously shown 75–90% gene silencing in short-term in vivo experiments (Witting et al., 2008; Ruiz et al., 2009).

Despite the enormous potential of RNAi as a therapeutic treatment and as a tool in functional studies, unintended interactions between the silencing molecule and cellular components occur (known as nonspecific effects). Administration of high doses of siRNA can result in nonspecific events due to activation of innate immune responses such as the interferon response, through poorly understood molecular mechanisms (Robbins et al., 2008). Induction of this response is siRNA concentration dependent (Persengiev et al., 2004) and cell type dependent (Reynolds et al., 2006), which indicates that data generated in one cell type may not apply to a different one, and that studies need to be conducted in the cell/tissue of interest. In addition, it has been shown that cells have a limited capacity to process shRNA, and that oversaturation of the exportin-5 pathway (necessary to transport shRNA to the cytoplasm) by high-level shRNA expression results in downregulation of endogenous microRNAs, inducing cell death (Grimm et al., 2006). Our studies have shown that constitutive expression of shRNA induces interferon responses in a sequence and adenovirus dose-dependent manner (Witting et al., 2008). Altogether these data clearly indicate that the successful establishment of RNA interference as a universal tool to study gene function and for clinical applications requires a better understanding of shRNA processing in vivo.

We have reported that it is possible to express shRNA from the U6 promoter and to induce gene silencing in liver for up to 3 weeks in the absence of interferon responses (Ruiz et al., 2009). To study the feasibility of constitutively expressing shRNA for multiple weeks, we analyzed the impact on target gene expression, endogenous microRNA levels, as well as expression of interferon-responsive genes. Our data suggest that constitutive shRNA expression results in effective processing of hairpin molecules. Nevertheless, mature hairpin molecules accumulate to an extent that eventually induces cellular toxicity.

Materials and Methods

Helper-dependent adenoviral vector production

Cloning and rescue of helper-dependent adenoviral vectors gAd.shSREBP1, gAd.shSCR, and gAd.NEC have been described previously (Witting et al., 2008; Ruiz et al., 2009). All these vectors are based on serotype 5 adenovirus, which transduces hepatocytes efficiently (Stratford-Perricaudet et al., 1990) and can infect hepatic stellate cells (Inagaki et al., 2005) and macrophages (Wheeler et al., 2001), but poorly transduces sinusoidal endothelial cells (Hegenbarth et al., 2000). Large-scale preparations of these three vectors were obtained in 293Cre4 cells (Microbix Biosystems, Toronto, ON, Canada) (Parks et al., 1996), following a previously described protocol (Ruiz et al., 2009). Briefly, 293Cre4 cells grown at 95% confluency in 15 triple flasks (500 cm2; 5–7 × 107 cells per flask) were infected with helper-dependent vector at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 3 and with helper H14 at an MOI of 2. Cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, and were harvested in the presence of >90% cytopathic effect (CPE). The virus was purified by one CsCl step gradient centrifugation followed by one CsCl isopycnic separation. The helper-dependent adenovirus band was collected and dialyzed in TMN buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol). Total viral particles were determined spectrophotometrically after particle disruption with 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (absorbance at 260 nm [A260] = 1 corresponds to 1.1 × 1012 viral particles/ml). Stocks were stored at −80°C and diluted in TMN buffer for in vivo administration.

Animals

Male 8-week-old C57BL/6J mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Animal care guidelines set forth by the Indiana University School of Medicine (Indianapolis, IN) were followed. Mice were kept in a BL2 facility and had access to standard chow and water ad libitum. Mice received 1 × 1011 viral particles (VP) of gAd.shFABP5, gAd.shSREBP1, gAd.shSCR, gAd.NEC, or vehicle in a volume of 250 μl, by tail vein injection. Animals were killed at the times indicated in text. Livers were collected and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen or fixed in 10% formalin buffer for histological analysis. Serum was obtained and frozen at −20°C.

Alanine aminotransferase test

Serum alanine aminotransferase was tested with a liquid ALT (SGPT) reagent set (Pointe Scientific, Canton, MI). Twenty microliters was used for the analysis, in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blotting

Liver protein extracts were generated by tissue homogenization in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer containing protein inhibitors (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.25% [w/v] deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], aprotinin/leupeptin/pepstatin [1 μg/ml]; pH 7.5). Protein concentration was measured with a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Forty micrograms of protein was loaded in 10 or 15% SDS–polyacrylamide Criterion gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred to 0.2-μm polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Blocking was performed in TBS-T (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20; pH 7.5) with 5% blocking-grade milk (Bio-Rad). Primary antibodies against sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 (SREBP1) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), Eri-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), fatty acid binding protein-5 (FABP5) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), α-tubulin (Millipore, Temecula, CA), and cyclophilin-40 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) were diluted in blocking solution and incubated for 2 hr at room temperature (α-tubulin) or overnight at 4°C (SREBP-1, Eri-1, FABP5, and cyclophilin 40). Secondary antibody incubations were carried out for 1 hr at room temperature. Blots were developed with an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and exposed to enhanced chemiluminescence film (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

RNA isolation and Northern blot analysis

RNA was isolated from approximately 100 mg of frozen liver tissue, using a mirVana RNA isolation kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer's instructions. mRNA and microRNA (miRNA)-enriched RNA fractions were obtained. RNA concentration was determined by light absorption at 260 nm (A260), using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Six micrograms of miRNA-enriched RNA was heated for 5 min at 95°C. Samples were separated on 15% TBE–urea gels (Bio-Rad), transferred to Hybond N+ membranes (GE Healthcare) at 10 V for 1.5 hr, and UV-cross-linked with a Stratalinker 2400 (Stratagene/Fisher Scientific, La Jolla, CA). Sequences of the DNA oligonucleotide probes used are shown in Table 1. RNA oligonucleotides with the sequence of the precursor shRNA (50-nucleotide) sequence, or the mature SREBP (21-nucleotide) sequence, were used as controls to determine the size of the shRNA produced in vivo. For hybridization, DNA oligonucleotide probes (100 pmol) were labeled with digoxigenin-labeled deoxyuridine-triphosphate (DIG-dUTP), using a DIG oligonucleotide tailing kit, second generation (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Membranes were prehybridized for 2 hr at 60°C. Probes were hybridized to membranes at 25°C overnight in a hybridization oven. After hybridization, membranes were briefly washed and incubated for 30 min in blocking solution. Blots were subjected to immunological detection, using anti-digoxigenin antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (AP) (Roche Diagnostics). The signal was developed with a CSPD ready-to-use kit (Roche Diagnostics).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide Sequences

| Primers for qRT-PCR (5′ → 3′) | |

| ISG56: | AGAGAACAGCTACCACCTTT (F) TGGACCTGCTCTGAGATTCT (R) |

| OAS1b: | TTGATGTGCTGCCAGCCTAT (F) TGAGGCGCTTCAGCTTGGTT (R) |

| Eri-1: | ATCGAAGTTCATTTCCTCCAATGG (F) TCATAGTAACTGTCCCCAGCGG (R) |

| AldoA: | GAGCAGAAGAAGGAGCTGTC (F) GTCTCGTGGAAGAGGATCAC (R) |

| Primers for vector genome qPCR (5′ → 3′) | |

| pSHL: | GCGTGCCAGACAAAAGGAAAG (F) CACTCCAGCAGCCCAGAATC (R) |

| GK: | GGACCAGAGGCTCCTTACCT (F) ACCAGCTTGAGCAGCACAAG (R) |

| Oligonucleotides for Northern blot (5′ → 3′) | |

| 5S RNA: | TTAGCTTCCGAGATCA |

| SCR-as: | ACTTGACCTCCTTATACTCTC |

| SCR-s: | GAGAGTATAAGGAGGTCAAGT |

| SREBP1-as: | AGTTTGTCTGTGTCCACAACC |

| SREBP1-s: | GGTTGTGGACACAGACAAACT |

| miR122-as: | TGGAGTGTGACAATGGTGTTTGT |

| miR122-s: | ACAAACACCATTGTCACACTCCA |

ISG56, interferon-stimulated gene 56; OAS1b, 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase 1b; ISG20, interferon-stimulated gene 20; Aldo A, aldolase A; pSHL, shuttle plasmid for rescue of helper-dependent adenoviral vectors; GK, glucokinase; as, antisense; s, sense.

qRT-PCR

The mRNA-enriched fraction (described previously) was treated with RNase-free DNase (Qiagen, Germantown, CA) to remove contaminant DNA. The concentration of the RNA was determined in the NanoDrop 2000, and the A260/A280 ratio was between 1.9 and 2.1. mRNA quantification was performed by real-time RT-PCR, using a SYBR green Qiagen one-step RT-PCR kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. qRT-PCR was carried out with an ABI 7500 instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primer pairs were designed to bind different exons of the gene and amplify fragments of approximately 200 bp, and were first confirmed to yield a single band of the expected size by agarose gel electrophoresis, as well as a negative result in wells containing sample without reverse transcriptase (RT–). Primer pairs were synthesized by Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and are described in Table 1. A standard curve was generated with serial dilutions of an RNA sample from a vehicle-treated mouse (200 ng down to 6.25 ng). Test samples were diluted to 25 ng/μl and quantification of mRNA levels was done by analyzing 50 ng of RNA, in duplicate, in a 50-μl reaction volume and using a 0.5 μM concentration of each primer. Threshold cycle (Ct) values were compared with those of the standard curve. Aldolase A was used as loading control gene. This gene was selected on the basis of the absence of statistically significant differences between the groups. Fold changes are expressed relative to the gAd.NEC-treated group. This group was used as reference after confirming that levels of all genes analyzed were not significantly different from the vehicle-treated group (data not shown). All gAd.NEC, gAd.shSREBP1, and gAd.shSCR samples were analyzed in the same 96-well plate.

Microarray analysis

Samples (three per group) were labeled as per the standard Affymetrix protocol for the WT sense target labeling and control reagents kit according to the Affymetrix user manual GeneChip Whole Transcript (WT) Sense Target Labeling Assay. Individual labeled samples were hybridized to the GeneChip Mouse Gene 1.0 ST array for 17 hr and then washed, stained, and scanned according to the standard protocol, using the Affymetrix GeneChip operating system (GCOS). GCOS was used to generate data (CEL files). Arrays were visually scanned for abnormalities or defects. CEL files were imported into the Partek genomics suite (Partek, St. Louis, MO). RMA (robust multichip average) signals were generated for the core probe sets, using the RMA background correction, quantile normalization, and summarization by median polish. Summarized signals for each probe set were log2 transformed. These log-transformed signals were used for principal components analysis, hierarchical clustering, and signal histograms to determine whether there were any outlier arrays. Untransformed RMA signals were used for fold change calculations. Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), using log2-transformed signals with treatment as factor and all possible contrasts made. Fold changes were calculated using the untransformed RMA signals. Gene expression comparisons were made between shSCR (scrambled shRNA sequence) versus NEC control and shSREBP1 (shRNA knocking down SREBP1 expression) versus NEC control, and only genes changing in the same direction in both comparisons with p < 0.01 and false discovery rate < 0.05 were considered. A total of 2016 genes were upregulated and 577 were downregulated. To identify pathways/processes in which these genes are implicated, 1.5-fold upregulated genes (868) and 1.5-fold downregulated genes (216) were classified by functional annotation clustering (NIH DAVID [Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery] database; Huang et al., 2009) and a medium- or high-stringency level. Only clusters with an enrichment score ≥1.3 were considered.

Vector genome copy number

Genomic DNA was extracted from approximately 100 mg of frozen tissue, using a Qiagen genomic kit. Helper-dependent adenoviral vector genome copy number was quantified by real-time PCR, using an ABI 7500 instrument (Applied Biosystems) and a power SYBR green kit (Applied Biosystems) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. Vector DNA quantification was done as previously described (Ruiz et al., 2009), using a 0.5 μM concentration of a primer pair specific to the backbone sequence in the helper-dependent vector genome, and primers specific to the glucokinase gene, used as loading control (Table 1). A standard curve was generated by spiking DNA, isolated from a mouse treated with vehicle, with known amounts of pSHL-GFP plasmid to generate a standard curve with 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 copies per cell. DNA levels in standards and test samples were measured by analyzing 30 ng of DNA, in duplicate. After adjusting for glucokinase levels, the genome copy number of each sample was determined by regression analysis.

Histology

Four-micron-thick sections were cut from paraffin-embedded tissue and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histological analysis. Processing and staining were performed at the Immunohistochemistry Core (IHC) at Indiana University Medical Center (Indianapolis, IN). Liver sections were analyzed by an experienced liver pathologist (R.S.) in a blinded fashion.

Statistical analysis

Numerical data represent means ± SD. Significant differences are defined as p < 0.05 by two-tailed, unpaired t test.

Results

Gene silencing is maintained over time

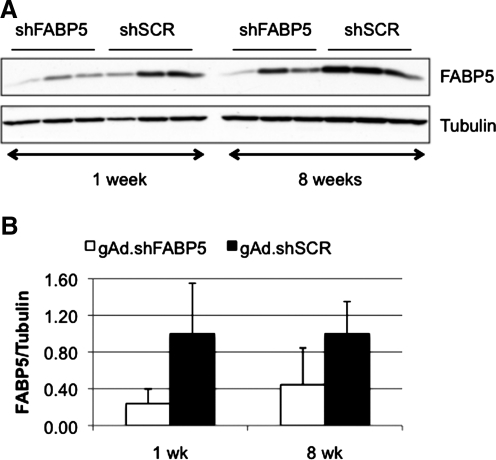

We have previously reported that administration of 1 × 1011 VP of gAd.shFABP5 (expressing an shRNA to knock down fatty acid binding protein-5 [FABP5]) resulted in 75% gene silencing 1 week after vector administration (Witting et al., 2008). To study the feasibility of expressing shRNA for multiple weeks in liver, C57BL/6 mice were given 1 × 1011 VP of gAd.shFABP5 or gAd.shSCR (expressing a scrambled sequence), and were killed after 1 or 8 weeks. A significant level of silencing was maintained at week 8 compared with week 1 (Fig. 1), suggesting it is possible to obtain stable knockdown with helper-dependent adenoviral vectors.

FIG. 1.

Gene silencing is maintained over time. Mice were given 1 × 1011 VP of gAd.shFABP5 or gAd.shSCR intravenously (n = 3). Animals were killed 1 or 8 weeks later. (A) Levels of FABP5 protein were quantified by Western blot. Lanes correspond to individual animals. (B) Densitometry analysis of FABP5 levels. Data represents averaged results of individual animals.

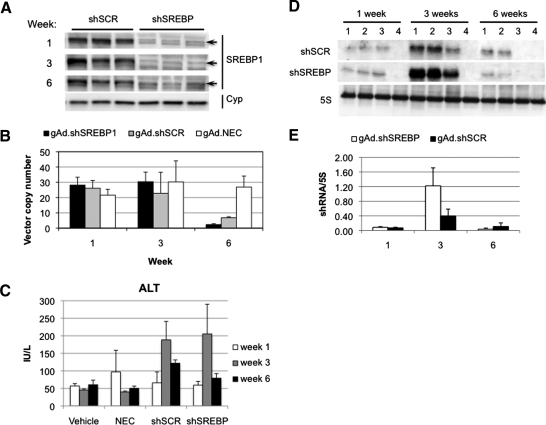

Constitutive shRNA expression leads to liver cell damage

To determine whether these observations were reproduced with a vector targeting a different gene and to study in more detail the effects of expressing shRNA for multiple weeks, C57BL/6 mice were injected 1 × 1011 VP of gAd.shSREBP1 (expressing an shRNA to knock down the transcription factor sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 [SREBP1]) or gAd.shSCR. As controls for shRNA expression, groups of mice received gAd.NEC (no expression cassette) or vehicle. Mice were killed 1, 3, and 6 weeks postinjection. SREBP-1 knockdown was observed at weeks 1 and 3 and was maintained at week 6 (Fig. 2A). Surprisingly, quantification of adenoviral vector genome copy number revealed a significant decrease between weeks 3 and 6 with both shRNA-expressing vectors (gAd.shSCR and gAd.shSREBP1) (Fig. 2B). This correlated with an increase in ALT levels, a marker of liver damage (Fig. 2C). No difference in vector genome copy number was observed in animals treated with gAd.NEC, indicating the loss of vector DNA was not due to toxicity from the helper-dependent adenoviral vector itself, but was associated with shRNA expression.

FIG. 2.

Long-term shRNA expression results in loss of vector genomes. Mice were given 1 × 1011 VP of gAd.shSREBP1, gAd.shSCR, or gAd.NEC, or vehicle, intravenously and were killed 1, 3, and 6 weeks postinjection (n = 3). (A) SREBP1 gene silencing in the liver was evaluated by Western blot analysis. Lanes correspond to individual animals. Cyp, cyclophilin. (B) DNA was isolated from liver and vector genome copy number was analyzed by real-time PCR. DNA vector from the shRNA-expressing vectors decreased between weeks 3 and 6. (C) ALT levels were increased over time only in shRNA-expressing groups, not in vehicle and NEC (no expression cassette) groups. (D) The microRNA fraction was extracted from liver and shRNA expression was quantified by Northern blot. The level of shRNA expression was highest at 3 weeks and then declined, correlating with the level of vector DNA. Numbers 1 to 3 at the top of the lanes represent mice that received adenoviral vector. Lane 4 represents a mouse treated with vehicle (negative control for shRNA expression). (E) Densitometric analysis of shRNA expression relative to 5S.

Loss of vector DNA correlates with shRNA accumulation in the liver

To determine whether vector DNA correlated with level of shRNA, the microRNA-enriched RNA fraction was isolated and levels of shRNA present in the liver were quantified by Northern blot. Interestingly, shRNA levels increased between weeks 1 and 3 and decreased between weeks 3 and 6, correlating with the DNA levels (Fig. 2D and E). Similar results were seen for both shRNA-expressing vectors, regardless of whether the shRNA silenced a gene or not. The accumulation of shRNA between weeks 1 and 3 was surprising, as steady state expression is achieved within a few days after administration of a helper-dependent adenoviral vector expressing a transgene (Morral et al., 1998).

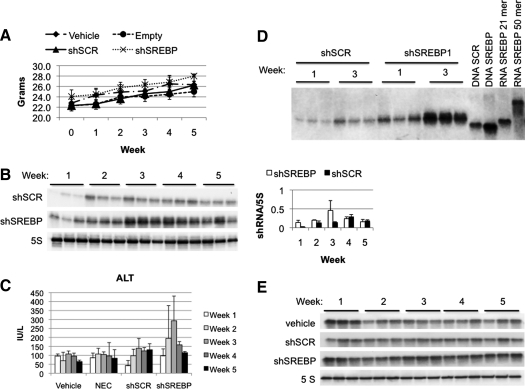

Loss of transduced hepatocytes is unrelated to saturation of the RNAi machinery

To study in more detail how this process occurs, mice were given 1 × 1011 VP of gAd.shSREBP1, gAd.shSCR, or gAd.NEC, or vehicle, and killed weekly for 5 consecutive weeks. Mouse body weight did not change in any vector group compared with mice receiving vehicle (Fig. 3A), and none of the animals displayed any signs of sickness or discomfort, indicating that the presence of shRNA-related toxicity in liver did not result in fulminant hepatitis, as had previously been described for adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated shRNA expression (Grimm et al., 2006). As previously observed, shRNA accumulation was observed over weeks 1 to 4, and then levels declined gradually (Fig. 3B). This correlated with ALT levels, suggesting liver cell death (Fig. 3C). McBride and colleagues (2008) have shown that expression of shRNA in the brain, using the U6 promoter, leads to toxicity as the result of accumulation of unprocessed hairpin molecules. Contrary to what has been observed in the brain, unprocessed molecules were not detectable in the liver (Fig. 3D). Only mature molecules of the expected 21-nucleotide molecular mass were detected (Fig. 3D), indicating that a mechanism of unprocessed shRNA was unlikely in our study. A second possible cause of toxicity was saturation of the exportin-5 pathway, inducing endogenous microRNA dysregulation and eventually cell death, as previously reported by Grimm and colleagues (2006). Levels of miR-122, a liver-expressed miRNA, were not different in expression among treatments and time points (Fig. 3E), suggesting that processing of constitutively expressed shRNA did not saturate exportin-5.

FIG. 3.

shRNA expression elicits buildup of molecules over time. Mice were administered 1 × 1011 VP of gAd.shSREBP1, gAd.shSCR, or gAd.NEC, or vehicle, and were killed weekly for 5 weeks (n = 3). (A) Body weight was not altered significantly among treatment groups. (B) shRNA expression was quantified by Northern blot (left) and densitometric (right) analysis of shRNA levels. Lanes correspond to individual animals. (C) ALT levels. (D) Northern blot of the microRNA-enriched fraction, using oligonucleotide (oligo) sequences to detect shSCR or shSREBP molecules. An RNA oligo with the precursor (50-mer) or mature (21-mer) SREBP sequence was spiked into the RNA of a vehicle-treated animal to determine the size of the shRNA molecules present in liver. Only molecules corresponding to the processed shRNA were detected. DNA SCR, scrambled DNA 21-nucleotide antisense sequence; DNA SREBP, SREBP DNA 21-nucleotide antisense sequence; RNA 21-mer, SREBP mature 21-nucleotide RNA oligo; RNA 50-mer, SREBP precursor 50-nucleotide oligo. (E) miR-122 levels were not altered at any time points.

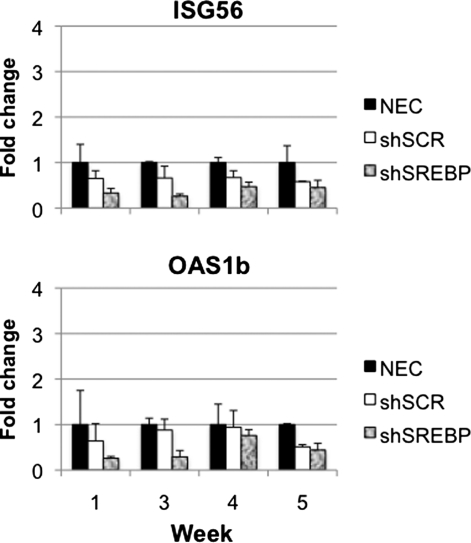

Constitutive expression of shRNA induces cell death without interferon response activation

To test whether the accumulation of shRNA on week 3 stimulated the cellular antiviral defense pathway, interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) Oas1b and Isg56, were analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. OAS1 (oligoadenylate synthetase-1) induces degradation of RNA through activation of RNase L and subsequent inhibition of protein synthesis (Sledz and Williams, 2004), and ISG56 functions as a suppressor of viral replication and protein translation (Terenzi et al., 2006). Oas1b and Isg56 levels were not different between the gAd.NEC and vehicle groups (data not shown). No increase was observed between the gAd.shSREBP1 or gAd.shSCR group and the gAd.NEC-treated mice, at any of the time points (Fig. 4). This suggested that the interferon response was not activated in shRNA-expressing mice.

FIG. 4.

Interferon-stimulated gene (ISG) expression. Mice were treated as described in Fig. 3. Expression levels of two ISG genes, ISG56 and Oas1b, were quantified by real-time RT-PCR. No increase was observed in the gAd.shSREBP and gAd.shSCR groups compared with the gAd.NEC group.

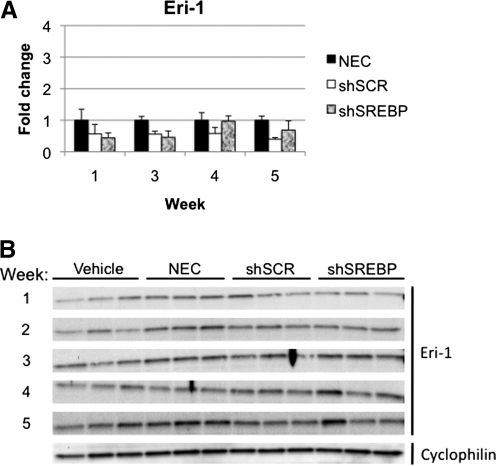

Exonuclease Eri-1 (enhanced RNAi) has been reported to have negative regulatory effects on RNAi (Gabel and Ruvkun, 2008). Eri-1 can degrade the 3′ end of siRNA and histone mRNA in Caenorhabditis elegans, humans, and fission yeast (Hong et al., 2005; Gabel and Ruvkun, 2008). Administration of high doses of siRNA induces Eri-1 expression in mice (Hong et al., 2005). Thus, we tested whether Eri-1 expression was upregulated in mice expressing shRNA. No increase in Eri-1 mRNA or protein was observed in the gAd.shSREBP or gAd.shSCR group at any time point (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Eri-1 gene and protein analysis. Mice were treated as described in Fig. 3. (A) mRNA expression analysis of Eri-1 in liver by real-time RT-PCR. (B) Western blot quantification of Eri-1 protein. No differences were observed in any group at any time point.

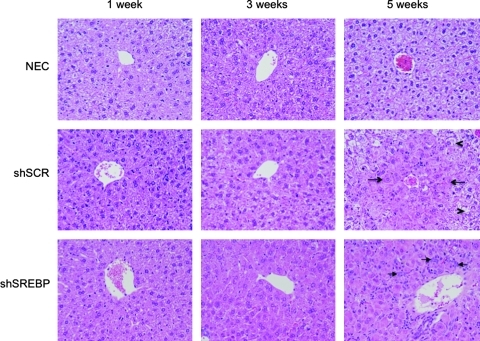

To determine whether the toxicity correlated with the presence of inflammation, liver sections were stained with hematoxylin–eosin and analyzed by a liver pathologist in a blinded fashion. In agreement with the absence of positive data on the interferon response, no significant inflammation was observed in any of the groups at any time point (Fig. 6). Instead, there was evidence of cellular toxicity, manifested as enlarged hepatocytes that contained pale, ground glass cytoplasmic inclusions. This cellular change was accompanied by numerous apoptotic bodies without accompanying inflammation. Although mitotic figures were present, apoptotic activity outstripped mitotic activity. These histological changes were first observed at a low level at week 3 and involved hepatocytes around the central veins. At weeks 4 and 5, the changes involved increasing numbers of hepatocytes, extending outward toward the portal tracts. The change was both more prominent and more extensive in the gAd.shSREBP1 mice than in the gAd.shSCR animals, extending further out toward the portal tracts in the former group. At week 5, the gAd.shSREBP1 mice showed prominent oval cell proliferation around the portal tracts (Fig. 6). Oval cells are stem cells of the liver that proliferate when the capacity of hepatocytes to divide has been exhausted (Oh et al., 2002). Overall, these observations suggest a process of cellular damage triggered by accumulation of mature shRNA molecules. The more extensive damage in mice that received gAd.shSREBP compared with mice that received gAd.shSCR most probably resulted from the higher accumulation of shRNA in the former animals between weeks 1 and 3 (Fig. 3B). This in turn led to oval cell proliferation as the proliferative capacity of damaged hepatocytes was depleted.

FIG. 6.

Histology of mouse liver sections. Mice were treated as described in Fig. 3. Liver sections were stained with hematoxylin–eosin and analyzed by a liver pathologist. Panels display the central vein area. In gAd.shSCR-treated liver, dense cells suggestive of having cellular toxicity are denoted by arrows, and normal cells are identified by arrowheads. In animals that received the gAd.shSREBP vector, dense cells were observed almost everywhere in the liver. Arrows indicate the presence of oval cells.

Microarray analysis suggests role of RNAi components in the pathology

To identify pathways that were altered from overexpressing shRNA, RNA was isolated from livers of mice that received the gAd.NEC, gAd.shSCR, or gAd.shSREBP1 vector and were killed at week 4. This time point was chosen because both groups were expected to have alterations in gene expression induced by shRNA toxicity. We did not observed upregulation of interferon-induced genes (including ISG20, OAS1, and ISG56, which we had previously found highly upregulated when sequences that induce an interferon response are expressed in liver; Witting et al., 2008), confirming that the response is distinct from well-characterized mechanisms of toxicity (Witting et al., 2008). In accordance with the protocol established by Huang and colleagues (2009), functional annotation clustering was performed. This type of analysis organizes redundant/similar/hierarchical terms within a group and allows the investigator to focus on multiple redundant clusters at a glance (Huang et al., 2009). The downregulated genes gave clusters that contained two classes of genes: ribosomal and mitochondrial (Table 2; the full gene list is available on request). Functional annotation clustering for upregulated genes gave clusters in the following categories: cell division (mitogen-activated protein kinase [MAPK] pathway, cytoskeleton organization, cell cycle/growth arrest); endosomal vesicle formation; intracellular protein transport; chromatin-remodeling genes (such as Baz2a, a gene shown to inhibit ribosomal RNA [rRNA] synthesis; Zhou et al., 2002); ubiquitination; gene silencing; helicase activity (Table 3; the full gene list is available on request). Genes in more than one of these categories were expected to be dysregulated in the livers of gAd.shSCR- and gAd.shSREBP1-treated mice, given the presence of cell death/division in liver sections (Fig. 6). Interestingly, we observed that several genes in the RNAi pathway were upregulated. Previous studies have shown that siRNA transfection leads to increased expression of TNRC6 (trinucleotide repeat-containing-6), a component of the miRNA pathway (Khan et al., 2009). Our microarray data suggest a possible model in which constitutive expression of shRNA induced expression of molecules of the RNAi pathway such as Dicer1, Mov10, Tnrc6b, and Cnot1. Upregulation of these molecules may have initiated a cascade of events through increased recruitment of cellular mRNA–RISC complexes for mRNA degradation, inducing alterations in cellular mRNA levels incompatible with normal function, and causing cell death.

Table 2.

Genes Downregulated More Than 1.5-Fold

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Fold change shSCR and shSREBP1 vs. NEC |

|---|---|---|

| Ribosome, structural constituents of ribosome | ||

| Snrpg | Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein polypeptide G | −2.15 |

| Rps25 | Ribosomal protein S25 | −2.09 |

| Rps12 | Ribosomal protein S12 | −1.98 |

| Mrpl13 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L13 | −1.95 |

| Rps24 | Similar to ribosomal protein S24 | −1.89 |

| Rps27 | Ribosomal protein S27 | −1.87 |

| Rps23 | Ribosomal protein S23 | −1.83 |

| Mrps33 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein S33; predicted gene 12540 | −1.78 |

| Rps7 | Ribosomal protein S7 | −1.78 |

| Rpl36 | Ribosomal protein L36 | −1.76 |

| Rpl3 | Ribosomal protein L3 | −1.74 |

| Rpl11 | Ribosomal protein L11 | −1.73 |

| Rpl35a | Similar to ribosomal protein L35a | −1.72 |

| Mrps7 | Mitchondrial ribosomal protein S7 | −1.68 |

| Rpl27a | Ribosomal protein L27a | −1.66 |

| Rps18 | Similar to ribosomal protein S18 | −1.6 |

| Rpl5 | Similar to 60S ribosomal protein L5 | −1.58 |

| Rpl14 | Ribosomal protein L14 | −1.57 |

| Rps9 | Ribosomal protein S9; predicted gene 5905 | −1.57 |

| Mitochondria | ||

| Ociad2 | OCIA domain containing 2 | −2.01 |

| Cml1 | N-Acetyltransferase 8B; camello-like 1 | −1.97 |

| Atp5e | ATP synthase, H+ transporting, mitochondrial F1 complex, ɛ subunit | −1.88 |

| 1810027O10Rik | RIKEN cDNA 1810027O10 gene | −1.85 |

| Cox4i1 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV isoform 1 | −1.82 |

| Ndufa4 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1α subcomplex, 4 | −1.81 |

| Ndufb8 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1β subcomplex 8 | −1.79 |

| Dnajc19 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily C, member 19 | −1.76 |

| Ndufb3 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1β subcomplex 3 | −1.75 |

| Cidea | Cell death-inducing DNA fragmentation factor, α subunit-like effector A | −1.63 |

| Cisd1 | CDGSH iron sulfur domain 1 | −1.61 |

| Atp5l | ATP synthase, H+ transporting, mitochondrial FO complex, subunit G2, pseudogene | −1.6 |

| Tomm7 | Translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 7 homolog (yeast) | −1.54 |

Table 3.

Genes Upregulated More Than 1.5 Fold

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Fold change shSCR and shSREBP1 vs. NEC |

|---|---|---|

| Posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression | ||

| Mov10 | Moloney leukemia virus 10; predicted gene 7357 | 2.36 |

| Eif4g1 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4, γ1 | 2.14 |

| Mknk2 | MAP kinase-interacting serine/threonine kinase 2 | 2.12 |

| Dicer1 | Dicer1, Dcr-1 homolog (Drosophila) | 2.06 |

| App | Amyloid β (A4) precursor protein | 1.93 |

| Cpeb2 | Cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein 2 | 1.85 |

| Eif4g3 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4γ, 3 | 1.83 |

| Flna | Filamin, alpha | 1.79 |

| Zcchc11 | Zinc finger, CCHC domain containing 11 | 1.78 |

| RNA-mediated gene silencing | ||

| Mov10 | Moloney leukemia virus 10; predicted gene 7357 | 2.36 |

| Tnrc6b | Trinucleotide repeat containing 6b | 2.07 |

| Dicer1 | Dicer1, Dcr-1 homolog (Drosophila) | 2.06 |

| Cnot1 | CCR4-NOT transcription complex, subunit 1 | 1.86 |

| Zcchc11 | Zinc finger, CCHC domain containing 11 | 1.78 |

| Ubiquitin-associated | ||

| Mark2 | MAP/microtubule affinity-regulating kinase 2 | 2.02 |

| Dhx57 | DEAH (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp/His) box polypeptide 57 | 2.01 |

| Ubqln2 | Ubiquilin 2 | 1.95 |

| Ubap2 | Ubiquitin-associated protein 2 | 1.90 |

| Nbr1 | Neighbor of Brca1 gene 1 | 1.87 |

| Helicase | ||

| Mov10 | Moloney leukemia virus 10; predicted gene 7357 | 2.36 |

| Ddx58 | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 58 | 2.12 |

| Dicer1 | Dicer1, Dcr-1 homolog (Drosophila) | 2.06 |

| Dhx57 | DEAH (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp/His) box polypeptide 57 | 2.01 |

| Chd8 | Chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 8 | 2.00 |

| Smarca4 | SWI/SNF related, matrix associated, actin dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily a, member 4 | 1.98 |

| Ep400 | E1A binding protein p400 | 1.85 |

| Chd9 | Chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 9 | 1.77 |

| Ercc2 | Excision repair cross-complementing rodent repair deficiency, complementation group 2 | 1.76 |

| Cell cycle | ||

| Rb1 | Retinoblastoma 1 | 2.67 |

| Ccnb1 | Cyclin B1 | 2.63 |

| Ccnd1 | Cyclin D1 | 2.44 |

| Ep300 | E1A binding protein p300 | 2.12 |

| Ccna2 | Cyclin A2 | 2.08 |

| Plk1 | Polo-like kinase 1 (Drosophila) | 2.04 |

| Crebbp | CREB binding protein | 1.97 |

| Cdk6 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 | 1.82 |

| Smad3 | MAD homolog 3 (Drosophila) | 1.68 |

| Smc1a | Structural maintenance of chromosomes 1A | 1.64 |

| Endosome/lysosome | ||

| Tpp1 | Tripeptidyl peptidase I | 2.97 |

| Igf2r | Insulin-like growth factor 2 receptor | 2.81 |

| Clcn7 | Chloride channel 7 | 2.41 |

| Siae | Sialic acid acetylesterase | 2.40 |

| Cd68 | CD68 antigen | 2.18 |

| Slc15a3 | Solute carrier family 15, member 3 | 2.06 |

| Man2b1 | Mannosidase 2, α B1 | 2.01 |

| Ctns | Cystinosis, nephropathic | 2.00 |

| Laptm5 | Lysosomal-associated protein transmembrane 5 | 1.99 |

| Arsb | Arylsulfatase B | 1.98 |

| Arl8a | ADP-ribosylation factor-like 8A | 1.95 |

| Hexb | Hexosaminidase B | 1.87 |

| Npc1 | Niemann Pick type C1 | 1.84 |

| Gns | Glucosamine (N-acetyl)-6-sulfatase | 1.83 |

| 0610031J06Rik | RIKEN cDNA 0610031J06 gene | 1.75 |

| Lrba | LPS-responsive beige-like anchor | 1.75 |

| Ctsa | Cathepsin A | 1.74 |

| Gba | Glucosidase, β, acid | 1.74 |

| Lgmn | Legumain | 1.71 |

| Psap | Prosaposin | 1.67 |

| Slc29a3 | Solute carrier family 29 (nucleoside transporters), member 3 | 1.58 |

| Vps11 | Vacuolar protein sorting 11 (yeast) | 1.55 |

| Cytoskeleton | ||

| Spna2 | Spectrin α 2 | 2.33 |

| Utrn | Utrophin | 2.28 |

| Vcl | Vinculin | 2.26 |

| Mast2 | Microtubule associated serine/threonine kinase 2 | 2.22 |

| Wasf2 | WAS protein family, member 2 | 2.06 |

| Spnb2 | Spectrin β 2 | 2 |

| Nf1 | Neurofibromatosis 1 | 1.99 |

| Mapre3 | Microtubule-associated protein, RP/EB family, member 3 | 1.91 |

| Actn4 | Actinin α 4 | 1.84 |

| Phactr4 | Phosphatase and actin regulator 4 | 1.84 |

| Add1 | Adducin 1 (α) | 1.83 |

| Tln1 | Talin 1 | 1.83 |

| Actn1 | Actinin, α 1 | 1.81 |

| Flna | Filamin, α | 1.79 |

| Flnb | Filamin, β | 1.79 |

| Fmnl2 | Formin-like 2 | 1.79 |

| Arfgef2 | ADP-ribosylation factor guanine nucleotide-exchange factor 2 (brefeldin A-inhibited) | 1.78 |

| Ctnna1 | Catenin (cadherin associated protein), α 1 | 1.78 |

| Coro1c | Coronin, actin binding protein 1C; predicted gene 5790 | 1.77 |

| Eps8l2 | EPS8-like 2 | 1.76 |

| Ablim3 | Actin binding LIM protein family, member 3 | 1.74 |

| Cap1 | CAP, adenylate cyclase-associated protein 1 (yeast) | 1.72 |

| Diap2 | Diaphanous homolog 2 (Drosophila) | 1.72 |

| Myo9b | Myosin IXb | 1.71 |

| Msn | Moesin | 1.69 |

| Myo9a | Myosin IXa | 1.67 |

| Pxk | PX domain containing serine/threonine kinase; similar to PX domain-containing protein kinase-like protein (Modulator of Na,K-ATPase) (MONaKA) | 1.65 |

| Myo5b | Myosin VB | 1.64 |

| Shroom2 | Shroom family member 2 | 1.63 |

| Macf1 | Microtubule-actin crosslinking factor 1 | 1.62 |

| Pls3 | Plastin 3 (T-isoform) | 1.59 |

| Chromatin remodeling | ||

| Rb1 | Retinoblastoma 1 | 2.67 |

| Mll5 | Myeloid/lymphoid or mixed-lineage leukemia 5 | 2.12 |

| Ep300 | E1A binding protein p300 | 2.12 |

| Bre | Brain and reproductive organ-expressed protein | 2.11 |

| Ncor1 | Nuclear receptor co-repressor 1 | 2.04 |

| Baz2a | Bromodomain adjacent to zinc finger domain, 2A | 2.01 |

| Chd8 | Chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 8 | 2.00 |

| Smarca4 | SWI/SNF related, matrix associated, actin dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily a, member 4 | 1.98 |

| Crebbp | CREB binding protein | 1.97 |

| Huwe1 | HECT, UBA, and WWE domain containing 1 | 1.94 |

| Myst3 | MYST histone acetyltransferase (monocytic leukemia) 3 | 1.87 |

| Ep400 | E1A binding protein p400 | 1.85 |

| Smarcc1 | SWI/SNF related, matrix associated, actin dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily c, member 1 | 1.84 |

| Eya3 | Eyes absent 3 homolog (Drosophila) | 1.82 |

| Setd2 | SET domain containing 2 | 1.80 |

| Bptf | Bromodomain PHD finger transcription factor | 1.79 |

| Ezh1 | Enhancer of zeste homolog 1 (Drosophila) | 1.78 |

| Chd9 | Chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 9 | 1.77 |

| Nsd1 | Nuclear receptor-binding SET-domain protein 1 | 1.74 |

| Aifm1 | Apoptosis-inducing factor, mitochondrion-associated 1 | 1.73 |

| Ubn1 | Ubinuclein 1 | 1.71 |

| Myst2 | MYST histone acetyltransferase 2 | 1.70 |

| Pbrm1 | Polybromo 1 | 1.69 |

| Smc1a | Structural maintenance of chromosomes 1A | 1.64 |

| Rnf40 | Ring finger protein 40 | 1.63 |

| Rcor1 | REST corepressor 1 | 1.57 |

| Rbm14 | RNA binding motif protein 14 | 1.57 |

| Protein transport | ||

| Praf2 | PRA1 domain family 2; predicted gene 4168 | 2.46 |

| Ap2b1 | Adaptor-related protein complex 2, β 1 subunit | 2.17 |

| Scamp2 | Secretory carrier membrane protein 2 | 2.17 |

| Sec31a | Sec31 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) | 2.11 |

| Mia3 | Melanoma inhibitory activity 3 | 2.07 |

| Pom121 | Nuclear pore membrane protein 121 | 2.06 |

| Slc15a3 | Solute carrier family 15, member 3 | 2.06 |

| Tpr | Similar to nuclear pore complex-associated intranuclear coiled-coil protein TPR; translocated promoter region | 2.00 |

| Spnb2 | Spectrin β 2 | 2.00 |

| Tom1l2 | Target of myb1-like 2 (chicken) | 1.99 |

| Ap2a1 | Adaptor protein complex AP-2, α 1 subunit | 1.96 |

| Nup210 | Nucleoporin 210 | 1.94 |

| Ipo13 | Importin 13 | 1.93 |

| Copa | Coatomer protein complex subunit α | 1.91 |

| Ipo4 | Importin 4 | 1.91 |

| Xpo6 | Exportin 6 | 1.87 |

| Nup214 | Nucleoporin 214 | 1.86 |

| Sec24b | Similar to SEC24 related gene family, member B (S. cerevisiae) | 1.86 |

| Htt | Huntingtin | 1.85 |

| Pdcd6ip | Programmed cell death 6 interacting protein | 1.85 |

| Actn4 | Actinin α 4 | 1.84 |

| Tln1 | Talin 1 | 1.83 |

| Nsf | N-Ethylmaleimide sensitive fusion protein | 1.80 |

| Psen1 | Presenilin 1 | 1.80 |

| Arf3 | ADP-ribosylation factor 3 | 1.80 |

| Hgs | HGF-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate | 1.79 |

| Ctnnb1 | Catenin (cadherin associated protein), β 1 | 1.79 |

| Flna | Filamin, α | 1.79 |

| Scamp3 | Secretory carrier membrane protein 3 | 1.78 |

| Ap3b1 | Adaptor-related protein complex 3, β 1 subunit | 1.76 |

| Lrba | LPS-responsive beige-like anchor | 1.75 |

| Vps13a | Vacuolar protein sorting 13A (yeast) | 1.75 |

| Mon2 | MON2 homolog (yeast) | 1.73 |

| Os9 | Amplified in osteosarcoma | 1.72 |

| Ston2 | Stonin 2 | 1.70 |

| Oxa1l | Oxidase assembly 1-like | 1.69 |

| Rab10 | RAB10, member RAS oncogene family | 1.67 |

| Ranbp2 | RAN binding protein 2 | 1.67 |

| Ap1b1 | Adaptor protein complex AP-1, β 1 subunit | 1.67 |

| Tnpo2 | Transportin 2 (importin 3, karyopherin β 2b) | 1.66 |

| Scamp4 | Secretory carrier membrane protein 4 | 1.65 |

| Cog1 | Component of oligomeric Golgi complex 1 | 1.64 |

| Myo5b | Myosin VB | 1.64 |

| Ap3d1 | Adaptor-related protein complex 3, δ 1 subunit | 1.63 |

| Shroom2 | Shroom family member 2 | 1.63 |

| Macf1 | Microtubule-actin crosslinking factor 1 | 1.62 |

| Eif4enif1 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E nuclear import factor 1 | 1.60 |

| Trpc4ap | Transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily C, member 4 associated protein | 1.59 |

| Vps11 | Vacuolar protein sorting 11 (yeast) | 1.55 |

| Tom1 | Predicted gene 5884; target of myb1 homolog (chicken) | 1.51 |

| Tsc2 | Tuberous sclerosis 2 | 1.50 |

Discussion

The speed and cost-effectiveness of in vivo gene silencing using viral vectors compared with generating knockout mice has made this system an essential tool to study gene function and in target validation. Several studies have shown the feasibility of this approach to silence liver genes, using AAV and adenoviral vectors (Giering et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2009; Ruiz et al., 2009). We have previously shown that hepatic shRNA expression, using helper-dependent adenoviral vectors, is a feasible approach, and approximately 75–90% gene specific knockdown can be obtained in short-term experiments (1 to 3 weeks) (Witting et al., 2008; Ruiz et al., 2009). In addition, hepatic shRNA expression has the potential to become a treatment for human diseases such as hepatitis B and C virus infection (McCaffrey et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2007). However, the safe application of RNAi as a therapeutic intervention and in functional studies remains an issue, as little is known about the side effects induced by constitutive expression of shRNA in vivo.

A previous study investigated the feasibility to use first-generation adenoviral vector-mediated shRNA expression in gene-silencing studies (Narvaiza et al., 2006). This type of vector results in activation of cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses, and clearance of transduced cells occurs soon after vector administration (Yang et al., 1994). Thus, expression of shRNA is expected to be transient and gradually decline as cells are cleared. Expression of shRNA peaked on day 7 and declined afterward, with small amounts of shRNA still being detectable after 150 days (Narvaiza et al., 2006). Target gene silencing was observed for only 12 days (Narvaiza et al., 2006). In contrast, transduction of liver cells by helper-dependent adenoviral vectors results in long-term gene expression (Morral et al., 1999). Thus, shRNA expression with this type of vector is expected to be maintained over time. In the present study we have shown that shRNA expression levels accumulate over a period of 3–4 weeks. Although transient toxicity was induced after this time point, resulting in loss of vector genomes and a subsequent reduction in shRNA levels, gene silencing was maintained for at least 6 weeks. This observation suggests that low amounts of processed shRNA are needed to obtain silencing. It is interesting that in the study by Narvaiza and colleagues, despite the low level of shRNA detection, no gene silencing was observed beyond 12 days. Given that each shRNA sequence has a different efficacy at silencing the target gene, it is possible that our construct was more efficacious than the one used by Narvaiza and colleagues (2006).

It is remarkable that shRNAs did not reach a steady state level by 7 days after vector administration, as occurs with transgene expression from constitutive promoters, but instead accumulated up to weeks 3 and 4. Three possible scenarios could be devised to explain the increase in shRNA levels after week 1. The first involves downregulation of the U6 promoter (used to express shRNA) on adenovirus entry in liver cells, and subsequent recovery to normal promoter activity after 2–3 weeks. If this scenario were true, the cellular U6 small nuclear RNA (snRNA) gene would also be dysregulated, and levels of this snRNA would gradually increase during weeks 2 and 3 compared with week 1, similar to what was observed with shSREBP1 and shSCR shRNAs. However, we did not observe differences in U6 snRNA levels between time points for any of the groups (data not shown). Thus, accumulation is unlikely to be related to U6 promoter activity. A second possibility is that shRNAs are amplified once the double-stranded RNA is formed in the cell, a mechanism that has been described in C. elegans and plants, and more recently in Drosophila (Aliyari and Ding, 2009; Lipardi and Paterson, 2009). siRNA amplification occurs as part of the antiviral response and is needed for RNAi in lower eukaryotes. However, dsRNA amplification has never been described in mammals, and the homologous RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) required for amplification has not been identified. The third scenario involves multiple rounds of mRNA degradation by the same RISC–shRNA complex. In RNA reactions using HeLa S100 extracts, RISC–let-7 complexes are known to participate in at least 10 rounds of mRNA cleavage (Hutvagner and Zamore, 2002; Gregory et al., 2005). A single administration of siRNA in vivo maintains silencing in tissues for approximately 5–7 days. Thus, it would be expected that constitutive expression of shRNA combined with a multiple-turnover RISC–shRNA complex would lead to increasing levels of shRNA over the course of a few weeks. We believe this is the most plausible explanation to our observations. Future studies will include looking at effects of constitutive expression for multiple months to determine whether silencing can be maintained.

To look into the mechanism causing cellular toxicity, we observed that buildup of mature shRNA molecules occurred between weeks 1 and 4, regardless of whether the shRNA had a target (shSREBP) or not (shSCR) (Fig. 3B). Vector genome copy number was maintained during this time period, and declined afterward. This suggests excess mature hairpin molecules may have elicited a response that resulted in cell death. It is interesting that shRNA sequences without a target are also loaded into RISC and eventually can induce toxic effects similar to those elicited by shRNA molecules with a target mRNA. Higher loss of vector genomes (Fig. 2B) and more severe pathology profiles (including abundant numbers of oval cells around the portal tracts) were observed in the gAd.shSREBP1-treated animals compared with the gAd.shSCR group (Fig. 6). Whether this is related to the fact that the former has a gene target, and the latter does not, is unknown. A second possibility is that higher levels of shSREBP1 accumulated between weeks 1 and 3 (Figs. 2D and 3B), leading to more cellular damage.

We did not observe accumulation of precursor shRNA molecules or alterations in miR-122 levels (Fig. 3D and E), suggesting that exportin-5 and processing of the precursor shRNA to the cytoplasm were not limiting factors. Interferon-responsive genes were not upregulated (Fig. 4), and inflammatory cells were not present in the liver (Fig. 6), all of which suggest that activation of innate immunity was not the cause of cell death. We have previously observed a strong correlation between induction of an interferon response by shRNA and the presence of inflammation in liver (Witting et al., 2008). Lack of interferon-responsive gene expression was confirmed by microarray analysis of livers of mice killed at week 4. Data generated from this analysis suggest that shRNA expression upregulates genes involved in the RNAi pathway (Table 3). Three of these genes, Mov10, Tnrc6b, and Ccr4-Not1, are located in P-bodies (Table 3). The first two are associated with Argonaute (Ago) in mammalian cells and are required to mediate miRNA-guided mRNA cleavage (Meister et al., 2005). Mov10 is the human ortholog of Drosophila translational repressor Armitage, and has been shown to form a complex with RISC, eukaryotic translation initiation factor-6 (eIF6), and ribosomal proteins of the 60S subunit. eIF6 binds to 60S and inhibits assembly of the 60S and 40S ribosome for protein translation (Chendrimada et al., 2007). In neurons, Mov10 degradation has been shown to regulate synaptic plasticity through release of miRNA-mediated translationally repressed mRNA (Banerjee et al., 2009). Tnrc6b is one of three paralogs of GW182 in vertebrates (Ding and Han, 2007) and has been implicated in translational repression (Baillat and Shiekhattar, 2009). Last, Ccr4-Not is a protein present in P-bodies and is involved in mRNA decay through deadenylation (Behm-Ansmant et al., 2006). A model could be envisioned in which upregulation of several genes present in P-bodies may have triggered a cascade of events, starting with inappropriate levels of degradation of miRNA-regulated mRNAs, to a point incompatible with normal hepatocyte function, leading to cell death. Other studies have shown that shRNAs compete with endogenous miRNA for RNAi activity (Castanotto et al., 2007). In addition, saturation of molecules in the RNAi pathway has previously been shown to lead to toxicity (Grimm et al., 2006, 2010). Saturation of exportin-5 results in fulminant hepatitis (Grimm et al., 2006), and saturation of Ago proteins, in particular Ago-2, induces toxicity and cell death (Grimm et al., 2010). Increasing Ago-2 activity alleviates the toxicity and extends RNAi (Diederichs et al., 2008; Grimm et al., 2010). Nevertheless, Grimm and colleagues showed that the most efficient way to reduce cytotoxicity and prolong gene silencing was to use weaker promoters that resulted in lower levels of shRNA (Grimm et al., 2010). Kahn and colleagues have reported that transfection of small RNAs into cells results in increased expression of miRNA-regulated genes, likely through saturation of RNAi components downstream from exportin-5, such as Argonaute proteins and TRBP (HIV-1 trans-activating response [TAR] RNA-binding protein) (Khan et al., 2009). One of the upregulated genes was TNRC6 (Khan et al., 2009), one of the three GW182 paralogs. The data generated in our study suggests a model in which several genes in the RNAi pathway were upregulated, three of which are associated with P-bodies. Additional studies need to be conducted to confirm this model and whether increased P-body function is sufficient to induce toxicity. Last, it is also conceivable that downregulation of cellular gene expression due to off-target effects contributed to induce toxic effects and cell death. On the basis of all these studies, constitutive shRNA expression may result in toxicity from a combination of mechanisms, including saturation of the exportin-5 pathway, competition of shRNA with endogenous miRNA for RISC or for other molecules downstream from exportin-5, upregulation of genes in the RNAi pathway, or off-target effects, all of which can lead to dysregulated expression of cellular genes and potentially induce cell death.

In conclusion, expression of shRNA from helper-dependent adenoviral vectors leads to a high level of silencing for multiple weeks in vivo. Despite silencing, expression of shRNA results in cellular apoptosis and loss of vector genomes, likely because of excess accumulation of mature shRNA molecules. Our data have implications for the safe design of shRNA expression cassettes, and argue for close monitoring for signs of toxicity at multiple time points. This is particularly important for studies in which cell death/survival is an outcome of the gene-silencing treatment. As also observed by other groups (Grimm et al., 2010), our data suggest that the development of future vectors should include expression cassettes with lower promoter strength or inducible systems, to provide safer tools for gene function studies, gene target validation, and for clinical applications.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DK069432-01, DK078595); American Diabetes Association (1-08-RA-135); and INGEN (Indiana Genomics Initiative of Indiana University supported in part by Lilly Endowment Inc.). The authors thank Dr. Jeanette McClintick for assistance on microarray analysis, which was carried out using the facilities of the Center for Medical Genomics at Indiana University School of Medicine, supported in part by a grant from the Indiana 21st Century Research and Technology Fund, and by INGEN. Miwon Ahn was supported by the T32-Indiana University Diabetes and Obesity Research Training Program (DK064466), and Scott R. Witting by a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Aliyari R. Ding S.W. RNA-based viral immunity initiated by the Dicer family of host immune receptors. Immunol. Rev. 2009;227:176–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillat D. Shiekhattar R. Functional dissection of the human TNRC6 (GW182-related) family of proteins. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;29:4144–4155. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00380-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S. Neveu P. Kosik K.S. A coordinated local translational control point at the synapse involving relief from silencing and MOV10 degradation. Neuron. 2009;64:871–884. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behm-Ansmant I. Rehwinkel J. Doerks T., et al. mRNA degradation by miRNAs and GW182 requires both CCR4:NOT deadenylase and DCP1:DCP2 decapping complexes. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1885–1898. doi: 10.1101/gad.1424106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau R.L. McBride J.L. Martins I., et al. Nonallele-specific silencing of mutant and wild-type huntingtin demonstrates therapeutic efficacy in Huntington's disease mice. Mol. Ther. 2009;17:1053–1063. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummelkamp T.R. Bernards R. Agami R. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science. 2002;296:550–553. doi: 10.1126/science.1068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castanotto D. Sakurai K. Lingeman R., et al. Combinatorial delivery of small interfering RNAs reduces RNAi efficacy by selective incorporation into RISC. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:5154–5164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.C. Ko T.M. Ma H.I., et al. Long-term inhibition of hepatitis B virus in transgenic mice by double-stranded adeno-associated virus 8-delivered short hairpin RNA. Gene Ther. 2007;14:11–19. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chendrimada T.P. Finn K.J. Ji X., et al. MicroRNA silencing through RISC recruitment of eIF6. Nature. 2007;447:823–828. doi: 10.1038/nature05841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo R. Moll J. Target validation to biomarker development: Focus on RNA interference. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2008;12:63–70. doi: 10.1007/BF03256271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederichs S. Jung S. Rothenberg S.M., et al. Coexpression of Argonaute-2 enhances RNA interference toward perfect match binding sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:9284–9289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800803105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L. Han M. GW182 family proteins are crucial for microRNA-mediated gene silencing. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabel H.W. Ruvkun G. The exonuclease ERI-1 has a conserved dual role in 5.8S rRNA processing and RNAi. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:531–533. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giering J.C. Grimm D. Storm T.A. Kay M.A. Expression of shRNA from a tissue-specific Pol II promoter is an effective and safe RNAi therapeutic. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:1630–1636. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory R.I. Chendrimada T.P. Cooch N. Shiekhattar R. Human RISC couples microRNA biogenesis and posttranscriptional gene silencing. Cell. 2005;123:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm D. Kay M.A. Therapeutic short hairpin RNA expression in the liver: Viral targets and vectors. Gene Ther. 2006;13:563–575. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm D. Streetz K.L. Jopling C.L., et al. Fatality in mice due to oversaturation of cellular microRNA/short hairpin RNA pathways. Nature. 2006;441:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature04791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm D. Wang L. Lee J.S., et al. Argonaute proteins are key determinants of RNAi efficacy, toxicity, and persistence in the adult mouse liver. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:3106–3119. doi: 10.1172/JCI43565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegenbarth S. Gerolami R. Protzer U., et al. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells are not permissive for adenovirus type 5. Hum. Gene Ther. 2000;11:481–486. doi: 10.1089/10430340050015941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J. Qian Z. Shen S., et al. High doses of siRNAs induce eri-1 and adar-1 gene expression and reduce the efficiency of RNA interference in the mouse. Biochem. J. 2005;390:675–679. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu P.F. Chen H. Zhong W., et al. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of siRNA against PAI-1 mRNA ameliorates hepatic fibrosis in rats. J. Hepatol. 2009;51:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D.W. Sherman B.T. Lempicki R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutvagner G. Zamore P.D. A microRNA in a multiple-turnover RNAi enzyme complex. Science. 2002;297:2056–2060. doi: 10.1126/science.1073827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki Y. Kushida M. Higashi K., et al. Cell type-specific intervention of transforming growth factor β/Smad signaling suppresses collagen gene expression and hepatic fibrosis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:259–268. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A.A. Betel D. Miller M.L., et al. Transfection of small RNAs globally perturbs gene regulation by endogenous microRNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27:549–555. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipardi C. Paterson B.M. Identification of an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in Drosophila involved in RNAi and transposon suppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:15645–15650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904984106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Liu J. Carmell M.A. Rivas F.V., et al. Argonaute2 is the catalytic engine of mammalian RNAi. Science. 2004;305:1437–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.1102513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S. Cullen B.R. Adenovirus VA1 noncoding RNA can inhibit small interfering RNA and microRNA biogenesis. J. Virol. 2004;78:12868–12876. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12868-12876.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matranga C. Tomari Y. Shin C., et al. Passenger-strand cleavage facilitates assembly of siRNA into Ago2-containing RNAi enzyme complexes. Cell. 2005;123:607–620. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride J.L. Boudreau R.L. Harper S.Q., et al. Artificial miRNAs mitigate shRNA-mediated toxicity in the brain: Implications for the therapeutic development of RNAi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:5868–5873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801775105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey A.P. Meuse L. Pham T.T., et al. RNA interference in adult mice. Nature. 2002;418:38–39. doi: 10.1038/418038a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre G.J. Fanning G.C. Design and cloning strategies for constructing shRNA expression vectors. BMC Biotechnol. 2006;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister G. Landthaler M. Peters L., et al. Identification of novel Argonaute-associated proteins. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:2149–2155. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morral N. O'Neal W. Zhou H., et al. Immune responses to reporter proteins and high viral dose limit duration of expression with adenoviral vectors: Comparison of E2a wild type and E2a deleted vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 1997;8:1275–1286. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.10-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morral N. Parks R. Zhou H., et al. High doses of a helper-dependent adenoviral vector yield supraphysiological levels of α1-antitrypsin with negligible toxicity. Hum. Gene Ther. 1998;9:2709–2716. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.18-2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morral N. O'Neal W. Rice K., et al. Administration of helper-dependent adenoviral vectors and sequential delivery of different vector serotype for long-term liver-directed gene transfer in baboons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:12816–12821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narvaiza I. Aparicio O. Vera M., et al. Effect of adenovirus-mediated RNA interference on endogenous microRNAs in a mouse model of multidrug resistance protein 2 gene silencing. J. Virol. 2006;80:12236–12247. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01205-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neal W.K. Zhou H. Morral N., et al. Toxicity associated with repeated administration of first-generation adenovirus vectors does not occur with a helper-dependent vector. Mol. Med. 2000;6:179–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S.H. Hatch H.M. Petersen B.E. Hepatic oval “stem” cell in liver regeneration. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2002;13:405–4009. doi: 10.1016/s1084952102001271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks R.J. Chen L. Anton M., et al. A helper-dependent adenovirus vector system: Removal of helper virus by Cre-mediated excision of the viral packaging signal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:13565–13570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persengiev S.P. Zhu X. Green M.R. Nonspecific, concentration-dependent stimulation and repression of mammalian gene expression by small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) RNA. 2004;10:12–18. doi: 10.1261/rna5160904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds A. Anderson E.M. Vermeulen A., et al. Induction of the interferon response by siRNA is cell type- and duplex length-dependent. RNA. 2006;12:988–993. doi: 10.1261/rna.2340906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins M. Judge A. Ambegia E., et al. Misinterpreting the therapeutic effects of small interfering RNA caused by immune stimulation. Hum. Gene Ther. 2008;19:991–999. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz R. Witting S.R. Saxena R. Morral N. Robust hepatic gene silencing for functional studies using helper-dependent adenovirus vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2009;20:87–94. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiedner G. Morral N. Parks R., et al. Genomic DNA transfer with a high-capacity adenovirus vector results in improved in vivo gene expression and decreased toxicity. Nat. Genet. 1998;18:180–183. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sledz C.A. Williams B.R. RNA interference and double-stranded-RNA-activated pathways. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2004;32:952–956. doi: 10.1042/BST0320952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J.J. Smith S.K. Hannon G.J. Joshua-Tor L. Crystal structure of Argonaute and its implications for RISC slicer activity. Science. 2004;305:1434–1437. doi: 10.1126/science.1102514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratford-Perricaudet L.D. Levrero M. Chase J.F., et al. Evaluation of the transfer and expression in mice of an enzyme-encoding gene using a human adenovirus vector. Hum. Gene Ther. 1990;1:241–256. doi: 10.1089/hum.1990.1.3-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi C.M. Ueki K. Kahn R. Complementary roles of IRS-1 and IRS-2 in the hepatic regulation of metabolism. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:718–727. doi: 10.1172/JCI23187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Terenzi F. Hui D.J. Merrick W.C. Sen G.C. Distinct induction patterns and functions of two closely related interferon-inducible human genes, ISG54 and ISG56. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:34064–34071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605771200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler M.D. Yamashina S. Froh M., et al. Adenoviral gene delivery can inactivate Kupffer cells: Role of oxidants in NF-κB activation and cytokine production. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2001;69:622–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witting S.R. Brown M. Saxena R., et al. Helper-dependent adenovirus-mediated short hairpin RNA expression in the liver activates the interferon response. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:2120–2128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704178200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia H. Mao Q. Paulson H.L. Davidson B.L. siRNA-mediated gene silencing in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:1006–1010. doi: 10.1038/nbt739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. Li Q. Ertl H.C. Wilson J.M. Cellular immunity to viral antigens limits E1-deleted adenoviruses for gene therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:4407–4411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y. Santoro R. Grummt I. The chromatin remodeling complex NoRC targets HDAC1 to the ribosomal gene promoter and represses RNA polymerase I transcription. EMBO J. 2002;21:4632–4640. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]