Abstract

Objective:

Most cognitive models of substance abuse and dependence posit that controlled and automatic processes are central to substance use. Tests of these models rely on methods that are interpreted to measure one or the other of these processes. There has been growing interest in the use of implicit substance use tasks, which are posited to reflect automatic processes. Recent model advancements suggest that behavior is determined by multiple cognitive processes and that dual-process models may provide an overly simplistic account of the cognitive process involved in the assessment of implicit cognition. The goal of the current study was to apply the Quad Model to children's performance on implicit substance use tasks and consider associations with early substance use.

Method:

Children (N = 378; 52% girls) ranging from 10 to 12 years old completed alcohol and cigarette Single Category Implicit Association Tests (SC-IATs) and self-reports of substance use.

Results:

Four distinct cognitive processes were found to influence SC-IAT performance, one of which reflected automatic activation, the process typically viewed as central to IAT performance. Differences across drinking status revealed weaker automatic activation of negative alcohol associations for those who had (vs. had not) initiated drinking, and a strong likelihood to overcome biased attitudes was supported for all children. The low prevalence of cigarette use in our young sample prohibited examination of the model across smoking status.

Conclusions:

Findings suggest that performance on implicit substance use tasks is not process pure. Quantifying and interpreting the multiple influencing processes are crucial for further development and evaluation of cognitive risk models of substance use.

Initiation and escalation of alcohol and cigarette use occur during late childhood and adolescence (Chen and Kandel, 1995; Colder et al., 2002; Eaton et al., 2006), making this an important developmental period in which to examine precursors of substance use. Cognitive theory and empirical evidence suggest that positive and negative valenced attitudes and outcome expectancies are central to substance use (e.g., Bandura, 1977, 1986; Goldman et al., 1999; Maisto et al., 1999; Sayette, 1999), including initiation and maintenance of alcohol use and cigarette smoking (e.g., Chassin et al., 1981, 1984; Darkes and Goldman, 1993; Wahl et al., 2005). Dual-process models emphasize the role of self-regulatory (reflective) and impulsive processes on substance use (Chaiken and Trope, 1999; Deutsch and Strack, 2006; Devine, 1989; Evans, 2003; Evans and Coventry, 2006; see Sherman et al., 2008; Wiers et al., 2007) and provide an account for how cognitions influence substance use. The self-regulatory process is thought to involve deliberative and conscious appraisals of available information and influence behavior via a controlled process. Conversely, the impulsive process is thought to involve spontaneous and reflexive appraisals of stimuli and influence behavior via an automatic process. Dual-process models suggest that the joint effect of these two processes influences behavior (Chaiken and Trope, 1999).

Consistent with the dual-process model, there has been a marked shift toward examining the influence of both controlled and automatic cognitive processes on substance use, in both child and adult samples (e.g., Jajodia and Ear-ley wine, 2003; McCarthy and Thompsen, 2006; O'Connor et al., 2007; Pieters et al., 2010; Wiers et al., 2002). To date, two broad categories of measures have primarily been used in the substance use-cognition literature to map onto the dual-process model; these include explicit (self-report) and implicit (reaction time) measures. These have predominantly been assumed to correspond to self-regulatory (controlled) and impulsive (automatic) cognitive processes, respectively. Typically, individual differences assessed with these measures are interpreted to reflect a single cognitive process. This, however, may be an oversimplification of the processes that influence responding on measures of both implicit and explicit substance use cognition. If this is true, then interpreting measures in simplistic dichotomous terms (measuring controlled or automatic processes) may obscure our understanding of the association between cognition and substance use. The focus of the current study is on multiple processes that might affect assessment of implicit substance use attitudes, and we propose that only some are germane to substance use.

Over the past 10 years, there has been a substantial increase in the use of implicit tasks (e.g., priming tasks, Tabossi, 1996; Implicit Association Test [IAT], Greenwald et al., 1998; see Houben et al., 2006, for review) as a way to assess automatic substance use associations (Houben et al., 2006; Reich et al., 2010; Rooke et al., 2008). Automatically activated associations are thought to reflect the strongest associations formed in memory; thus, they may be particularly relevant to in-the-moment decisions to engage in substance use (Goldman et al., 2006; Greenwald and Banaji, 1995; Nisbett and Wilson, 1977). Moreover, disentangling individual differences in automatic compared with controlled processes should lead to a better understanding of the cognitive mechanisms leading to substance use. Like adult studies, examinations of early substance use in child and adolescent samples have pitted (e.g., Pieters et al., 2010; Thush and Wiers, 2007) or directly compared (e.g., O'Connor et al., 2007) responses on implicit tasks with those on explicit self-reports and from this have drawn conclusions about the distinct role of automatic activation of valenced substance use attitudes for behavior. Although automatic processes are of central interest with respect to implicit measures, we propose that performance on these measures may reflect processes in addition to automatic processes. That is, performance on implicit tasks likely reflects automatic valenced associations thought to be relevant to substance use but also other processes not germane to substance use. An important direction in the literature is to distinguish multiple cognitive processes involved in measures often assumed to be “process pure.”

Conrey et al.’s (2005) quadruple process model (Quad Model) suggests that behavior is determined by the relative influence of four cognitive processes. These include impulsive responding driven by the activation of an association (AC); accurate detection (D) of the contextually appropriate response; engagement of a self-regulatory process and overcoming the bias (OB); and guessing (G) or a response bias in the absence of clear information that leads to the engagement of another process (Sherman, 2006; Sherman et al., 2008). Conrey et al. (2005) applied the mathematical Quad Model to performance on the widely used IAT (Greenwald et al., 1998). In brief, the IAT requires categorization of stimuli from one of two object categories (e.g., insect, flower) and one of two evaluative categories (e.g., pleasant, unpleasant) as quickly as possible. Performance on compatible trials (e.g., flower and pleasant paired to same response key) compared with incompatible trials (e.g., insect and pleasant paired to same response key) is of interest. The Quad Model examines error rates across trials, in contrast to conventional scoring of the IAT, which examines reaction times. According to the Quad Model (Conrey et al., 2005), correct categorization in the compatible blocks depends on the activation (AC) of a pleasant-flower/unpleasant-insect bias (i.e., association) or, when a bias is not activated, detecting the correct response (D) or guessing (G) in a way that is consistent with bias. Similarly, correct categorization in the incompatible blocks depends on accurately detecting the correct response (D) and overcoming the bias (OB), when the bias is activated (AC), or detecting the correct response (D) or guessing (G) in a way that is not consistent with bias when a bias is not activated. Analysis by Conrey et al. (2005) supported the Quad Model, suggesting that the IAT reflects not only the automatic AC–a process it is traditionally interpreted to assess—but also the influence of D, OB, and G.

Recent social-cognition research has applied the Quad Model to implicit task data (see Sherman et al., 2008, for a review). For example, in a study of racial stereotyping, Gon-salkorale et al. (2009) found that traditional interpretation of the IAT suggested that elderly age was associated with negative racial biases. However, Quad Model findings showed that elderly age was not associated with strong activation of negative race associations, but rather elderly individuals were less likely to engage the self-regulatory process of overcoming their bias. Thus, ignoring multiple processes that influence performance on the IAT can lead to erroneous conclusions. It is crucial that a similar examination be done to distinguish the cognitive processes that are central to assessments of substance use attitudes.

In the current study, we applied the Quad Model to children's performance on substance use IATs and examined differences in the cognitive processes across substance use status. Consistent with dual-process models, of particular interest was explicating the joint influence of the automatic AC and engaging the self-regulatory OB process. The Quad Model would allow us to tease these processes apart from the other processes that may influence implicit task performance but are less theoretically relevant to substance use (i.e., G, D). Examining these processes in children who are normatively entering a stage for substance use initiation (Griffin, 2010) will permit an understanding of the role of these cognitive processes in early substance use. We focus on alcohol and cigarettes because these are the two most commonly used drugs in the early stages of substance use (Kandel and Yamaguchi, 2002). In addition, we also present results for traditional scoring (i.e., D-score) of the IAT for comparison.

Several adaptations of the IAT are available (e.g., unipolar Single Target-IAT [ST-IAT], Thush and Wiers, 2007; unipolar IAT, Houben and Wiers, 2006). These tasks differ from the original IAT on the object and/or the evaluative category side of the task. For example, the unipolar ST-IAT uses a single object category (e.g., alcohol), and both of these unipolar tasks use valenced versus neutral categories on the evaluative side (e.g., positive vs. neutral). Single Category IATs (SC-IATs, Karpinski and Steinman, 2006) are like the unipolar ST-IAT in that a single object category is used. However, unlike the unipolar tasks, the SC-IAT maintains the bipolar, contrasting evaluative categories (e.g., positive vs. negative). Using a single object category may be particularly suited for the assessment of alcohol and cigarettes, given the lack of naturally opposing categories. In addition, the bivalent nature of the attitudinal associations (“good” vs. “bad”) may have ecological validity for assessing substance use attitudes because substance use contexts typically include both positive and negative cues that compete for attention. Accordingly, SC-IATs were used in the current study to assess alcohol-and cigarette-related cognition.

Method

Participants

The sample is from an ongoing longitudinal project examining development of children's substance use and includes 378 families (one caregiver; one child) recruited in Erie County, NY, via random digit dialing. Participation rate was 48.5%, which is well within the range of population-based longitudinal studies (Galea and Tracy, 2007). Data for the current study come from the initial assessment. Children's (52% girls) mean age was 11.1 years (SD = 0.85; range = 10–12 years old). The majority of the children were White (75%), 15% were Black/African American, 3% were Hispanic, 2% were Asian/Pacific Islander, and 5% reported another race/ethnicity. The median yearly income was $60,000 USD.

Measures

Single Category Implicit Association Test (SC-IAT).

The SC-IAT (Karpinski and Steinman, 2006) is a modification of the IAT (Greenwald et al., 1998) that measures the strength of evaluative associations with a single attitude object. In the current study, children completed two separate SC-IATs, one for alcohol and one for cigarettes.

The SC-IATs involved discriminating between an evaluative dimension (good and bad words) and an object category (pictures of alcohol/cigarettes). Words were selected to be at a fourth-grade reading level and were balanced across evaluative dimension on word frequency, length, and syllabic content. The evaluative words were presented auditorily to decrease the lexical demand of the task, and object categories were presented on the computer screen in picture format. Participants were instructed to press the left-hand key (Z key) on their keyboard when they heard a good word (e.g., beautiful) and to press the right-hand key (?/ key) when they heard a bad word (e.g., sickness). The object category (alcohol/cigarettes) was paired with the response key for bad words in one block and then with the response key for good words in another block. Each block consisted of 24 practice trials, followed by 72 test trials. To limit response bias, the evaluative and object stimuli were not presented at equal frequency within the block. When alcohol/cigarette pictures were paired with good words, 21 trials consisted of good words, 30 trials consisted of bad words, and 21 trials consisted of alcohol/cigarette pictures. This resulted in relatively evenly balanced responses, with 58% of correct responses being on the left key and 42% being on the right key. Likewise, when alcohol/cigarette pictures were paired with bad words, 30 trials consisted of good words, 21 trials consisted of bad words, and 21 trials consisted of alcohol/ cigarette pictures. This resulted in 42% of correct responses being on the left key and 58% being on the right key. Thus, alcohol/cigarette pictures were paired with good and bad words at equal rates across the task.

Stimuli were presented for 1,500 ms, and labels reminding the participants which key to press for the evaluative and object stimuli were presented in the lower left and right corners of the computer screen. The inter-trial interval during the test trials was 250 ms. Feedback indicating correct (a green circle) and incorrect (a red X) responses was presented for 250 ms after each trial. The trial timed out after 1,500 ms, and accordingly no response was recorded for these trials. Participants who did not respond within the allotted time were given the following feedback for 250 ms: “Please respond more quickly.” Response times less than 350 ms were considered anticipations, and, in this case, participants received the following feedback for 250 ms: “Please wait for the stimulus.”

Self-report alcohol and cigarette use.

Alcohol and cigarette use questions (Johnston et al., 2003) were administered on a computer. Children were asked, “Have you ever used alcohol (or cigarettes for the cigarette questionnaire) with your parent's permission?” and “Have you ever used alcohol (or cigarettes for the cigarette questionnaire) without your parent's permission?” Children entered yes/no responses. Of the sample retained for analyses (see Data analytic plan and screening section below), 168 (45%) youth reported lifetime alcohol use (142 with parental permission and 26 without parental permission) and 13 (3.5%) youth reported lifetime smoking (all 13 smoked without parental permission). Levels of use were low; typical quantity was less than one drink or cigarette per occasion, and frequency of use in the past year was on average one time for both alcohol and cigarettes.

Procedure

On arrival to the laboratory, consent/assent forms were signed. The caregiver and child then completed assessments in separate rooms. All measures were administered on a computer, and directions/questionnaires were read aloud by the experimenter. The full assessment battery typically took 2.5–3 hours. Of relevance to this investigation was the child's performance on the alcohol and cigarette SC-IATs and self-reports of alcohol and cigarette use. The family was compensated with $75 for their participation, and the children earned a prize for their performance during the laboratory tasks.

Data analytic plan and screening

We analyzed the traditionally used D-scores, which are based on reaction time data, followed by the Quad Model analyses, which are based on rates of correct/incorrect responding. For each analytic strategy, we first examined the alcohol and cigarette SC-IATs for the overall sample, and this was followed by an examination of the SC-IATs across substance use status. The small number of children who had tried smoking precluded comparison across smoking status. Thus, only comparisons across drinking status were examined. Children were categorized into one of two drinking levels: those who had never drunk alcohol and those who had drunk alcohol either with or without their caregivers’ permission.

Approximately 1% of the trials on each SC-IAT were excluded from analyses because of no response. Data were excluded for two children on each SC-IAT because error rates were greater than 40%, and one child did not complete the cigarette SC-IAT; therefore, only their data for the alcohol SC-IAT is included. Treatment of trials with fast responses (<350 ms) varied across D-score and Quad Model analyses. Consistent with traditional scoring, fast responses were excluded from the D-score calculation because they were considered anticipatory responding. In contrast, incorrect/ correct responses made in less than 350 ms may be indicative of guessing and thus were retained for the Quad Model analyses.

Results

Traditional D-score

D-scores for the overall sample.

The D-score algorithm for IAT data developed by Greenwald et al. (2003) and adapted for the SC-IAT by Karpinski and Steinman (2006) was used. As calculated for the purpose of this study, a negative D-score indicated faster responding when substance use was paired with bad relative to good words. Thus, a negative D-score indicated stronger negative compared with positive substance use associations, and a positive D-score indicated stronger positive compared with negative substance use associations.

A test of the difference of the mean D-scores from μ = 0 for the alcohol (M = −0.044, SD = 0.286, n = 376) and cigarette (M = −0.066, SD = 0.288, n = 375) SC-IATs revealed D-scores that were less than zero, t(375) = −2.98, p = .003, d = 0.15; t(374) = −4.42, p < .001, d= 0.23, respectively. Thus, overall, responses were faster on blocks when substance use was paired with the same key as bad, rather than good, words. Although these findings suggest stronger negative compared with positive associations with alcohol and cigarette use, the small effect sizes (Cohen's d; Cohen, 1988) indicate possible ambivalence.

D-scores by drinking status.

A comparison of D-scores across drinking status, t(374) = 1.28,p = .20, d= 0.13, suggested that those who had tried alcohol (M = −0.023, SD = 0.294, n = 168) had equally as strong negative alcohol associations as those who had never tried alcohol (M = −0.061, SD = 0.279, n = 208). However, it is notable that the trend in the means suggests stronger negative attitudes among abstainers.

Quad Model

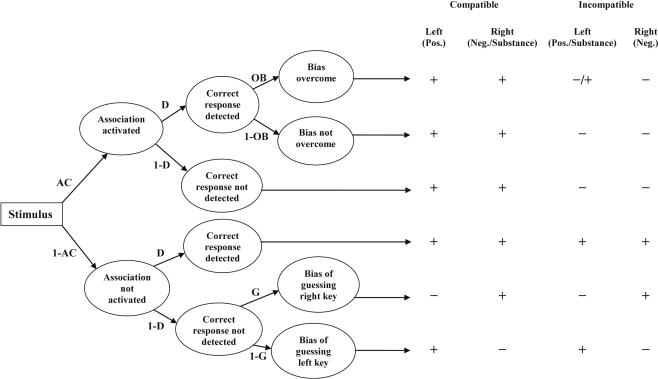

The first step in applying the Quad Model to the SC-IATs was to determine valence of the activated association by distinguishing compatible and incompatible pairings. The second step was to estimate the impact of the four proposed cognitive processes on performance on the substance use SC-IATs. This was done by fitting a hypothesized model to the pattern of correct/incorrect responses (Figure 1; equations are included in a Technical Appendix available from the first author on request).

Figure 1.

Processing tree of the quadruple process model (Quad Model) applied to substance use (alcohol, cigarettes). Model presented shows likelihood of correct/incorrect responses when there is activation of a negative substance association and general positive category (i.e., negative substance use pairing is compatible). Parameters with lines leading to it are conditioned on all preceding parameters. Right side of figure shows response [correct (+) or incorrect (−)] to valenced (positive and negative) words and substance use (alcohol, cigarettes) targets as a function of processes and block type (compatible; incompatible). AC = activation of an association; D = detection (correct response); OB = overcoming bias; G = guessing right key; 1 -AC = lack of activation of an association; 1-D = failure of detection (correct response); 1-OB = failure to overcome bias; 1-G = guessing left key; Pos. = positive; Neg. = negative.

Collapsing across blocks, error rates were 9% and 13% on the alcohol and cigarette SC-IATs, respectively. An examination of error rates by block revealed higher error rates when alcohol was paired with good (11%) compared with bad (8%) words and when cigarettes were paired with good (13%) compared with bad (12%) words. This suggests that substance use and bad word pairs were compatible and therefore supported testing the activation of negative associations with alcohol (AC negative-alcohol) and cigarettes (AC negative-cigarettes).

The Quad Model is a multinomial processing tree model (see Batchelder and Riefer, 1999) in which each path represents a predicted likelihood of making a correct/incorrect response based on a hypothesized model (Conrey et al., 2005; Gonsalkorale et al., 2009; Sherman et al., 2008). For each path, the parameter of a process that has lines leading to it is conditioned on all preceding process parameters. For example, in our hypothesized model (Figure 1), the probability of making a correct response (left key press) when a substance use stimulus (alcohol/cigarette) was presented during the incompatible block was the following: p(correct | substance use, incompatible) =AC × D × OB + (1 − AC) × D + (1 − AC) × (1 − D) × (1 − G). The conditioned relationships in our hypothesized model resulted in 10 such equations (these equations are included in a Technical Appendix available from the first author).

HMMTree software for multinomial processing tree models (Stahl and Klauer, 2007) was used to estimate the model using observed probabilities of correct/incorrect responses. In each application of the model, five parameters were estimated. These include activation of a general positive category (AC positive); activation of a negative substance use association (AC negative-alcohol/cigarette); and overcoming the bias of associating substance use with negative valence (OB), D, and G. Given that the models were saturated, of interest were the parameters produced by the model and whether each process affected SC-IAT performance rather than overall model fit.

Quad Model for overall sample.

The parameter estimates for the overall sample are presented in Table 1. Nested G2 tests (i.e., asymptotically chi-square-distributed log-likelihood statistic; see Hu and Batchelder, 1994) were used to evaluate statistical significance of the AC, D, and OB parameters; difference in strength of the AC parameters; and right-key bias. Parameters were tested in separate models, resulting in ΔG2(1 df) for each parameter. A statistically significant decrement in model fit from the full (hypothesized) to constrained model suggested that the parameter of interest was nonzero; or, in the case of parameter equivalence and right-key bias, the parameters statistically differ from one another and from .50 (suggesting bias), respectively.

Table 1.

Parameter estimates for alcohol and cigarette SC-IATs

| Parameter | Estimate | [95% CI] |

| Alcohol SC-IAT (n = 376) | ||

| AC negative–alcohol | 0.035 | [0.027, 0.042] |

| AC positive | 0.038 | [0.029, 0.047] |

| D | 0.820 | [0.813, 0.826] |

| OB | 1.000 | [0.718, 1.282] |

| G | 0.482 | [0.464, 0.500] |

| Cigarette SC-IAT (n = 375) | ||

| AC negative–cigarette | 0.041 | [0.032, 0.050] |

| AC positive | 0.034 | [0.024, 0.043] |

| D | 0.771 | [0.764, 0.778] |

| OB | 1.000 | [0.728, 1.272] |

| G | 0.437 | [0.421, 0.453] |

Notes: SC-IATs = Single Category Implicit Association Tests; CI = confidence interval based on expected Fisher information (see Stahl and Klauer, 2007); AC = activation of an association; D = detection (correct response); OB = overcoming bias; G = guessing right key.

Consistent with hypotheses, the AC negative-alcohol, ΔG2(1) = 82.35, p < .001, and AC negative-cigarette, ΔGl) = 88.38, p < .001, parameters were statistically significant. This supports automatic activation of negative substance use associations and suggests that a negative substance use bias plays a significant role in substance use SC-IAT performance. Activation of a general positive category (AC positive) was also supported, as demonstrated by the statistically significant parameter estimates on the alcohol, ΔG2(1) = 85.04, p < .001, and cigarette, ΔG^l) = 58.81, p < .001, SC-IATs.

To test for parameter equivalence, the AC negative-alcohol/cigarette parameter estimates were constrained to be equal to the AC positive parameter estimates in respective models. Constraining these parameter estimates to be equal did not result in a significant decrement in model fit for both alcohol and cigarettes, ΔG2s(l) ≤ 1.46, ps ≥ .23. This suggests that activation of a negative substance use association and a general positive category had an equivalent influence on task performance. In other words, a negative substance use bias is equal in strength to a broad positive category.

The OB parameters were statistically significant for both alcohol, ΔG2(1) = 73.96, p < .001, and cigarette, ΔGl) = 87.61, p < .001, tasks—suggesting that this self-regulatory process influenced performance. Detection of the correct response appeared to markedly influence performance on both SC-IATs, because constraining the D parameter to zero resulted in the models not converging. Finally, guessing (i.e., positive key bias) also influenced performance on the alcohol, ΔG2(1) = 4.86, p = .05, and cigarette, ΔG^l) = 79.83, p < .001, SC-IATs. Overall, these findings provide evidence for each of the four processes of the Quad Model influencing SC-IAT performance.

Quad Model by drinking status.

Multigroup tests were used to identify differences in strength of processes across drinking status. Parameter equivalence across drinking status was tested in five separate models, where a different parameter was constrained to be equal across groups in each model. A statistically significant ΔG2(1 df) indicated decrement in model fit with the added constraint, thus suggesting a difference in parameter strength across drinking status.

Parameter estimates and 95% confidence intervals for the hypothesized Quad Model applied to the data by drinking status are presented in Table 2. Consistent with expectation, the AC negative-alcohol parameter was higher for those who had never tried compared with those who had tried alcohol, ΔG2(1) = 17.87, p < .001. Thus, those who had never tried alcohol showed stronger negative association with alcohol. The D parameter was lower for those who had never tried alcohol compared with those who had, suggesting that the process of detecting the correct response was less engaged by those who had never drunk alcohol, ΔG2(1) = 10.72, p = .001. The OB process did not differ in strength across child drinking status, ΔGl) = 0.00, p > .99. Also, neither the AC positive nor G processes appeared to differ in strength across child drinking status, ΔG2s(1)) ≤ 2.07, ps > .05.

Table 2.

Parameter estimate for alcohol SC-IATs across drinking status

| Never drank (n = 208) |

Ever drank (n = 168) |

|||

| Parameter | Estimate | [95% CI] | Estimate | [95% CI] |

| AC negative–alcohol | 0.049a | [0.039, 0.060] | 0.017b | [0.006, 0.027] |

| AC positive | 0.044a | [0.032, 0.056] | 0.031a | [0.019, 0.044] |

| D | 0.811a | [0.802, 0.820] | 0.831b | [0.821,0.840] |

| OB | 1.000a | [0.721, 1.279] | 1.000a | [0.168, 1.832] |

| G | 0.491a | [0.467, 0.515] | 0.470a | [0.442, 0.498] |

Notes: SC-IATs = Single Category Implicit Association Tests; Never drank = never drank with or without parents’ permission; Ever drank = drank with and/or without parents’ permission; AC = activation of an association; D = detection (correct response); OB = overcoming bias; G = guessing right key;

a, bDifferent letter superscripts within a row indicate a statistically significant difference (p < .01) of the parameter estimate across drinking status. This was based on a multigroup analysis in which a statistically significant ΔG2(1 df) indicated decrement in model fit with the added constraint of parameter equivalence across drinking status. Parameter equivalence was tested in five separate models.

Discussion

There has been a marked increase in the use of implicit measures of cognition in the adult substance use literature (e.g., Jajodia and Earleywine, 2003; McCarthy and Thompsen, 2006; O'Connor and Colder, 2009; see also Houben et al., 2006, Reich et al., 2010, and Rooke et al., 2008, for reviews). A few studies have begun to extend downward to late childhood/adolescent samples to gain a better understanding of cognitive mechanisms leading to early substance use (e.g., O'Connor et al., 2007; Pieters et al., 2010; Thush and Wiers, 2007). The current study makes an important contribution to the relatively sparse literature on children's implicit substance use attitudes and critically extends the general substance use implicit cognition literature by examining the influence of multiple cognitive processes on SC-IAT performance.

Our data suggest that it is inaccurate to interpret the SC-IAT—and potentially the IAT and its other adapted forms—as assessing only automatic associations, as is typically done in the literature. Distinguishing multiple processes may prove to be important for our understanding of cognitive mechanisms of substance use. In particular, the activation of associations and guessing may both fall into the general category of automatic processes when examined from a dual-process model. However, the Quad Model allows distinction of these two processes and specific examination of activation of associations, which may be particularly relevant to substance use. Likewise, both overcoming biases and discriminating the correct response may be conceptualized as deliberate, controlled processes by dual-process models, whereas the Quad Model permitted a refined examination of the unique role of each. Thus, the Quad Model allowed us to delineate the role of the self-regulatory process of getting past one's bias to make a behavioral response, which may be particularly relevant to early substance use.

Examination of the joint influence on behavior of impulsive, automatic activation of associations and self-regulated, deliberate attempts to act in contrast to biases fits well with dual-process models (Deutsch and Strack, 2006; Evans, 2003; Evans and Coventry, 2006; Wiers et al., 2007). Results of our study found that children at the normative developmental stage for substance use initiation activated negative substance use biases but were successful in overcoming these biases and accessing positive associations with alcohol and cigarettes. Memory network models suggest that both positive and negative substance use expectancies are activated in early adolescence (Dunn and Goldman, 1998, 2000). Our findings are consistent with this, although they suggest that negative and positive substance use–related cognition may operate via different processes during initiation: one automatic and the other controlled. These competing controlled and automatic processes may reflect ambivalence. Motivational models suggest that ambivalence is central to decisions to use or not use a substance (Breiner et al., 1999; Cox and Klinger, 2002), and some evidence suggests that initiation of substance use in early adolescence is characterized by ambivalent substance use attitudes (Cameron et al., 2003; O'Connor et al., 2007). Our sample of 10- to 12-year-olds is at the early stages of initiation and may be moving toward ambivalence with respect to alcohol and cigarettes. This was evident in both the D-scores, which revealed only small effects for negative substance use biases, and in the Quad Model, which revealed automatic activation of negative substance use associations and deliberate attempts to overcome this negative bias.

When we compared children on drinking status, those who had tried alcohol showed a weaker activation of negative associations with alcohol than abstainers did. This is consistent with expectation and prior research showing that perceived costs decrease as children approach the age of initiation (O'Connor et al., 2007) and with observed declines in negative outcome expectancies after first initiation (Goldberg et al., 2002). We also found that children who had and had not tried alcohol were similarly likely to overcome their negative alcohol bias. This may reflect ambivalence about alcohol that characterizes abstainers and triers among early adolescents. Interestingly, those who had tried drinking, compared with those who had not, showed stronger engagement of the other self-regulatory process, that of determining the correct response. This process is conceptualized as a deliberate evaluation of the information at hand (i.e., correct/incorrect response). Alcohol stimuli may be self-relevant for children with drinking experience, and yet drinking alcohol is an illicit behavior. Thus, children with some drinking experience may be deliberating more during the task. Guessing and activation of the positive category did not vary across drinking groups, suggesting that although these processes influence task performance, they do not appear to be relevant for early alcohol use.

Traditional analysis of the reaction time data (D-score) highlights the limitation of this method. It does not allow full articulation of the processes influencing performance on the IAT, some of which we have argued are relevant to substance use (i.e., automatic activation and overcoming bias). Nonetheless, our analysis of the traditional D-score of reaction times suggested some similarity with the Quad Model findings. The D-score analysis indicated that children in our sample had negative alcohol and cigarette associations. This is consistent with the pattern of error rates and with nonzero AC negative-alcohol/cigarette parameters from the Quad Model analysis, both of which suggest negative substance use associations. Despite this area of agreement, important differences were also observed. Specifically, a difference in automatic activation of negative attitudes across drinking groups was evident with the Quad Model but not with the traditional D-score analyses, although means were in the expected direction.

Wiers and Stacy (2010) suggested that implicit tasks likely reflect processes in addition to automatic “associative processes” (p. 14). We suggest that the Quad Model provides an index of automatic activation of associations that is not contaminated with other processes. Findings from child/ adolescent studies using the traditional reaction time analysis of IAT data are inconsistent with respect to differences across drinking status. For example, Thush and Wiers (2007) found that abstainers had stronger negative alcohol associations than did drinkers in a sample of 15-year-olds, whereas Pieters et al. (2010) found that among 11- to 12-year-old children, the likelihood of drinking alcohol was positively related to having stronger associations of alcohol with sad versus happy faces. Thush and Wiers (2007), Pieters et al. (2010), and our current examination of reaction time data were similar in that they all used an IAT to assess valenced alcohol associations, but they differed with respect to IAT variant (unipolar ST-IAT vs. traditional dual category IAT vs. SC-IAT), evaluative category stimuli (visually presented words vs. pictures vs. auditorily presented words), and age (15- vs. 11- to 12- vs. 10- to 12-year-olds). It is hard to know what might account for the different findings. However, our Quad Model analysis suggests that the failure to isolate the process of automatic activation of associations may in part account for the variability in findings.

In summary, our findings suggest that children automatically activated negative alcohol and cigarette attitudes. The strength of these negative alcohol attitudes varied across drinking status; however, all children at this developmental stage were equally likely to overcome this bias. Future research should consider how these processes unfold as children age and escalate in their substance use. This will help us understand how negative automatic substance use associations and self-regulatory processes affect initiation, escalation, and maintenance of use. For example, is the weakening of negative substance use associations an antecedent or a consequence of use? That is, do negative substance use associations naturally dissipate as children approach the normative stage of substance use initiation, or are the weaker negative substance use associations that we found among those who had compared with those who had not tried alcohol a reflection of not experiencing negative consequences during early experimentation with alcohol (as found by Goldberg et al., 2002)? Developmentally oriented research should also address whether the strength of the four cognitive processes shifts as use escalates to heavy and problematic levels.

Our findings also speak to the importance of delineating cognitions beyond broad dual-process models for understanding early substance use. Specifically, the automatic process of activating negative substance use associations differed across drinking status, whereas the automatic process of guessing did not. Likewise, the controlled process of overcoming the bias did not differ across substance use status, whereas the controlled process of detecting the correct response did. Collapsing within these automatic and controlled categories, or collapsing across all of these processes as is typically done with implicit tasks, would have masked the findings, as was evident from our analyses of the reaction time data. Thus, a fruitful direction for the implicit substance use cognitive literature is to consider the role of multiple processes for task performance. Such a focus will help us better understand our measures and the cognitive mechanisms of substance use and substance use disorders.

Despite the contributions of this study to the cognitive-substance use literature, there are a few notable limitations. First, only a small number of children had initiated cigarette smoking, and therefore the model could not be extended to make a comparison of children's implicit cigarette task performance across smoking status. Second, this study was cross-sectional, thus limiting causal inferences. Third, this study should not be generalized beyond early adolescents who have limited direct experience with alcohol and cigarettes. The cognitive processes delineated in the Quad Model may change with age and substance use experience. Fourth, there are different variants of the IAT (e.g., unipolar IAT) and tasks other than the IAT (e.g., priming tasks) that have been used to assess implicit substance use cognition. It is unclear how our findings will generalize to these other tasks. However, although it is likely that the relative strength of the multiple processes delineated in this study will vary across tasks, it is anticipated that multiple cognitive processes influence performance on all of these measures of implicit substance use cognition. Finally, the SC-IAT did not permit a statistical test of Quad Model fit. Instead of model fit, we relied on the tests of parameter estimates and group differences on parameters. Extending the model to other implicit tasks may permit a test of Quad Model fit and a stronger test of the aptness of the model.

In spite of these limitations, our evaluation of the Quad Model provides meaningful direction for theory and methodological refinement. To date, implicit measures are most commonly conceptualized as indices of an automatic process of activating associations (e.g., Greenwald and Banaji, 1995; Nisbett and Wilson, 1977). The current study demonstrated that task performance was not process pure. That is, the IAT did not only assess automatic activation of substance use associations as is commonly assumed. Advancing etiologi-cal models of substance use may, in part, hinge on a better understanding of the combined and relative influence of multiple cognitive processes. In terms of methodological implications, it is important for researchers to more carefully interpret the processes captured in cognitive measures. Our data speak specifically to the importance of doing this for implicit cognition measures. Continued examinations of the Quad Model for substance use attitudes may reveal important implications for assessment tools and, eventually, for clinical interventions. For example, IATs may be used to tease apart the strength of a child's deliberative (controlled) and reflexive (automatic) cognitive processes related to substance use. This may be beneficial to individualized treatment planning and monitoring of treatment progress. Moreover, as we come to understand how these processes work in conjunction with one another to influence behavior, direction may be offered to prevention program development.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the University at Buffalo Neighborhood and Family Development Project staff for their help with data collection and all the families who participated in the study.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant R01 DA020171 (to Craig R. Colder).

References

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Batchelder WH, Riefer DM. Theoretical and empirical review of multinomial process tree modeling. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 1999;6:57–86. doi: 10.3758/bf03210812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiner MJ, Stritzke WGK, Lang AR. Approaching avoidance. A step essential to the understanding of craving. Alcohol Research & Health. 1999;23:197–206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron CA, Stritzke WGK, Durkin K. Alcohol expectancies in late childhood: An ambivalence perspective on transitions toward alcohol use. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:687–698. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiken S, Trope Y. Dual process theories in social psychology. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Corty E, Presson CC, Olshavsky RW, Bensenberg M, Sherman SJ. Predicting adolescents’ intentions to smoke cigarettes. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22:445–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, Corty E, Olshavsky RW. Predicting the onset of cigarette smoking in adolescents: A longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1984;14:224–243. [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Kandel DB. The natural history of drug use from adolescence to the mid-thirties in a general population sample. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:41–47. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Campbell RT, Ruel E, Richardson JL, Flay BR. A finite mixture model of growth trajectories of adolescent alcohol use: Predictors and consequences. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:976–985. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrey FR, Sherman JW, Gawronski B, Hugenberg K, Groom CJ. Separating multiple processes in implicit social cognition: The quad model of implicit task performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:469–487. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. Motivational structure. Relationships with substance use and processes of change. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:925–940. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darkes J, Goldman MS. Expectancy challenge and drinking reduction: Experimental evidence for a mediational process. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:344–353. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch R, Strack F. Reflective and impulsive determinants of addictive behavior. In: Wiers RW, Stacy AW, editors. Handbook of implicit cognition and addiction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. pp. 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Devine PG. Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn ME, Goldman MS. Age and drinking-related differences in the memory organization of alcohol expectancies in 3rd-, 6th-, 9th-, and 12th-grade children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:579–585. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn ME, Goldman MS. Validation of multidimensional scaling-based modeling of alcohol expectancies in memory: Age and drinking-related differences in expectancies of children assessed as first associates. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:1639–1646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Ross J, Hawkins J, Harris WA, Wechsler H. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2005. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2006, June 9;55(5):1–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JSt.BT. In two minds: Dual-process accounts of reasoning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2003;7:454–459. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JSt.BT, Coventry K. A dual-process approach to behavioral addiction: The case of gambling. In: Wiers RW, Stacy AW, editors. Handbook of implicit cognition and addiction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. pp. 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Annals of Epidemiology. 2007;17:643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JH, Halpern-Felsher BL, Millstein SG. Beyond invulnerability: The importance of benefits in adolescents’ decision to drink alcohol. Health Psychology. 2002;21:477–484. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.5.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MS, Del Boca FK, Darkes J. Alcohol expectancy theory: The application of cognitive neuroscience. In: Leonard KE, Blane HT, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 203–246. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MS, Reich RR, Darkes J. Expectancy as a unifying construct in alcohol-related cognition. In: Wiers RW, Stacy AW, editors. Handbook of implicit cognition and addiction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. pp. 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Gonsalkorale K, Sherman JW, Klauer KC. Aging and prejudice: Diminished regulation of automatic race bias among older adults. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45:410–414. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Banaji MR. Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review. 1995;102:4–27. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.102.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JLK. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1464–1480. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.6.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Nosek BA, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the implicit association test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:197–216. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Oakes MA, Hoffman HG. Targets of discrimination: Effects of race on responses to weapons holders. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2003;39:399–405. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KW. The epidemiology of adolescent substance use among adolescents and young adults: A developmental perspective. In: Scheier LM, editor. Handbook of drug use etiology: Theory, methods, and empirical findings. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 72–92. [Google Scholar]

- Houben K, Wiers RW. Assessing implicit alcohol associations with the Implicit Association Test: Fact or artifact? Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1346–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houben K, Wiers RW, Roefs A. Reaction time measures of substance-related associations. In: Wiers RW, Stacy AW, editors. Handbook of implicit cognition and addiction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. pp. 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Batchelder WH. The statistical analysis of general processing tree models with the EM algorithm. Psychometrika. 1994;59:21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Jajodia A, Earleywine M. Measuring alcohol expectancies with the implicit association test. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:126–133. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.2.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2002. Volume I: Secondary school students (NIH Publication No. 03–5375) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Yamaguchi K. Stages of drug involvement in the U.S. population. In: Kandel DB, editor. Stages and pathways of drug involvement: Examining the gateway hypothesis. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 65–89. [Google Scholar]

- Karpinski A, Steinman RB. The single category implicit association test as a measure of implicit social cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:16–32. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Carey KB, Bradizza CM. Social learning theory. In: Leonard KE, Blane HT, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 106–163. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy DM, Thompsen DM. Implicit and explicit measures of alcohol and smoking cognitions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:436–444. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett RE, Wilson TD. Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review. 1977;84:231–259. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor RM, Colder CR. Influence of alcohol use experience and motivational drive on college students’ alcohol-related cognition. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33:1430–1439. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor RM, Fite PJ, Nowlin PR, Colder CR. Children's beliefs about substance use: An examination of age differences in implicit and explicit cognitive precursors of substance use initiation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:525–533. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieters S, van der Vorst H, Engels RCME, Wiers RW. Implicit and explicit cognitions related to alcohol use in children. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich RR, Below MC, Goldman MS. Explicit and implicit measures of expectancy and related alcohol cognitions: A meta-analytic comparison. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:13–25. doi: 10.1037/a0016556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooke SE, Hine DW, Thorsteinsson EB. Implicit cognition and substance use: A meta-analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1314–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA. Cognitive theory and research. In: Leonard KE, Blane HT, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 247–291. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman JW. Clearing up some misconceptions about the Quad Model. Psychological Inquiry. 2006;17:269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman JW, Gawronski B, Gonsalkorale K, Hugenberg K, Allen TJ, Groom CJ. The self-regulation of automatic associations and behavioral impulses. Psychological Review. 2008;115:314–335. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl C, Klauer KC. HMMTree: A computer program for latent-class hierarchical multinomial processing tree models. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:267–273. doi: 10.3758/bf03193157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabossi P. Cross-modal semantic priming. Language and Cognitive Processes. 1996;11:569–576. [Google Scholar]

- Thush C, Wiers RW. Explicit and implicit alcohol-related cognitions and the prediction of future drinking in adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1367–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl SK, Turner LR, Mermelstein RJ, Flay BR. Adolescents' smoking expectancies: Psychometric properties and prediction of behavior change. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2005;7:613–623. doi: 10.1080/14622200500185579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, Bartholow BD, van den Wildenberg E, Thush C, En-gels RCME, Sher KJ, Stacy AW. Automatic and controlled processes and the development of addictive behaviors in adolescents: A review and a model. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2007;86:263–283. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, Stacy AW. Are alcohol expectancies associations? Comment on Moss and Albery (2009) Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:12–16. doi: 10.1037/a0017769. discussion 17–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, van Woerden N, Smulders FTY, de Jong PJ. Implicit and explicit alcohol-related cognitions in heavy and light drinkers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:648–658. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.111.4.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]