Abstract

CD73 is a GPI-anchored cell surface protein with ecto-5′-nucleotidase enzyme activity that plays a crucial role in adenosine production. While the roles of adenosine receptors (AR) on osteoblasts and osteoclasts have been unveiled to some extent, the roles of CD73 and CD73-generated adenosine in bone tissue are largely unknown. To address this issue, we first analyzed the bone phenotype of CD73-deficient (cd73−/−) mice. The mutant male mice showed osteopenia, with significant decreases of osteoblastic markers. Levels of osteoclastic markers were, however, comparable to those of wild type mice. A series of in vitro studies revealed that CD73 deficiency resulted in impairment in osteoblast differentiation but not in the number of osteoblast progenitors. In addition, over expression of CD73 on MC3T3-E1 cells resulted in enhanced osteoblastic differentiation. Moreover, MC3T3-E1 cells expressed adenosine A2A receptors (A2AAR) and A2B receptors (A2BAR) and expression of these receptors increased with osteoblastic differentiation. Enhanced expression of osteocalcin (OC) and bone sialoprotein (BSP) observed in MC3T3-E1 cells over expressing CD73 were suppressed by treatment with an A2BAR antagonist but not with an A2AAR antagonist. Collectively, our results indicate that CD73 generated adenosine positively regulates osteoblast differentiation via A2BAR signaling.

Keywords: CD73, adenosine, osteoblasts, bone, mouse

Introduction

A balanced relationship between bone resorption by osteoclasts and bone formation by osteoblasts is essential for bone remodeling which maintains bone integrity. The extracellular nucleotide ATP can be one of the key mediators in bone metabolism, not only as a phosphate source, but also as a signaling molecule via P2 receptors. In fact, osteoblasts have been reported to release ATP into the extracellular environment constitutively followed by engagement of P2 receptors (Buckley et al., 2003). The release of ATP by osteoblasts could be facilitated by mechanical stress (Romanello et al., 2001) and released ATP serves as an autocrine or paracrine regulator of both osteoblast and osteoclast function (Grol et al., 2009; Orriss et al., 2010). Meanwhile, it has been reported that P2 receptor signal transduction is rapidly inactivated by the extracellular breakdown of ATP to adenosine by the sequential actions of enzymes including members of the ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase and ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase families, ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) and alkaline phosphatases (ALPase) (Yegutkin, 2008). Although the role of ATP in bone metabolism has been revealed to some extent, functions of its metabolite adenosine are not fully elucidated.

The biological actions of adenosine are mediated via A1, A2A, A2B and A3 adenosine receptors that are ubiquitously expressed seven transmembrane spanning G-protein-coupled receptors. A1AR and A3AR mediate an inhibitory effect on adenylyl cyclase via Gi/Go, resulting in decreasing cAMP levels, whereas A2AAR and A2BAR stimulate adenylyl cyclase via activation of Gs with a consequent increase of cAMP (Ralevic and Burnstock, 1998). Recent reports suggested that adenosine supports osteoclast formation and bone resorption. It was shown that A1AR signaling was required for osteoclastogenesis in vitro (Kara et al., 2010b) and lack of A1AR resulted in increased bone mass in mice (Kara et al., 2010a). In addition, Evans et al. (2006) demonstrated that AR activation inhibited osteoprotegerin expression but did not affect receptor activator of NF-κB ligand expression in human osteoblasts. On the other hand, several in vitro studies demonstrated the role of adenosine in osteoblasts. Engagement of AR on murine osteoblasts induced mitogenesis (Fatokun et al., 2006; Shimegi, 1998) and protected them from cell death (Fatokun et al., 2006). In addition, selective agonists specific for each AR subtype modulated proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow stromal cells (Costa et al., 2010; Costa et al., 2011). Although these reports strongly suggest that AR signaling may play a critical role in osteoblasts, no report provides in vivo evidence.

AR activation is believed to be regulated by the extracellular adenosine level which is controlled by the coordinated action of an equilibrative nucleoside transporter and ecto-nucleotidases. CD73 is a major enzyme involved in the generation of extracellular adenosine by the dephosphorylation of adenosine 5′-monophosphate (Thomson et al., 1990). Although cytoplasmic nucleotidases also make a contribution to adenosine production, recent studies utilizing cd73−/− mice clearly demonstrated that CD73 plays a major role in the generation of extracellular adenosine in vivo in a number of physiologically relevant experimental models (Eckle et al., 2007; Takedachi et al., 2008; Thompson et al., 2004; Volmer et al., 2006). Interestingly, CD73 expression is regulated by Wnt-β-catenin signaling (Spychala and Kitajewski, 2004), a known critical pathway in bone metabolism (Baron et al., 2006; Piters et al., 2008; Williams and Insogna, 2009). It is also noteworthy that hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), a transcription factor reported to be important for bone regeneration and skeletal development (Wan et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2007), also regulates CD73 expression (Synnestvedt et al., 2002). Therefore, we hypothesized that CD73 may be involved in regulating osteoblast function through modulating nucleotide metabolism and generating extracellular adenosine that can activate AR.

To address this hypothesis, we asked whether CD73 functionally regulates bone metabolism in vivo by characterizing the bone phenotype of cd73−/− mice. In addition, we investigated the involvement of CD73 and AR signaling in osteoblast differentiation in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Mice

cd73−/− mice were developed as described (Thompson et al., 2004) and backcrossed onto the C57BL/6J background for 14 generations. Genotyping was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using DNA extracted from toes and primers that differentiate between the wild type cd73 allele and the mutated cd73 allele containing a neomycin resistance cassette (Thompson et al., 2004). All mice were bred and maintained in our animal facilities under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation and Osaka University Graduate School of Dentistry.

Peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) and micro-computed tomography (μCT)

In pQCT analyses, femurs were harvested from cd73+/+ and cd73−/− male and female mice at 13 -weeks of age and were fixed with 10% buffered formalin for 24 h and analyzed using an XCT Research SA+ instrument (Stratec Medizintechnik GmbH, Pforzheim, Germany). Voxel size was 0.08 × 0.08 × 0.46 mm. The contour of the total bone was determined automatically by the pQCT software algorithm. The parameters were obtained at 1.2 mm from the distal growth plate using threshold values of 690 mg/cm3 for the cortical region and 395 mg/cm3 for the trabecular region.

In μCT analyses, tibias from 13 -week-old cd73+/+ and cd73−/− male mice were scanned using μCT (μCT40, SCANCO Medical, Bruttisellen, Switzerland) to assess trabecular bone microarchitecture at the proximal tibia metaphysis. Scans of the proximal tibia metaphysis were performed at a resolution of 2048 × 2048 pixels. Analyses of the proximal tibia were accomplished by placing semi-automated contours beginning 0.03 mm distal to the growth plate and including a 0.6 mm volume of interest (VOI) of only secondary spongiosa for trabecular analyses. All samples were evaluated at a global threshold of 300 in the per mille unit to segment mineralized from soft tissue. Trabecular parameters evaluated included bone volume expressed per unit of total volume (BV/TV; %), trabecular number (TbN; 1/mm), trabecular thickness (TbTh; μm), and trabecular separation (TbSp; μm).

Histology and immunohistochemistry

For histological analysis, tibias were dissected from 13 week-old cd73+/+ and cd73−/− male mice and fixed overnight at 4°C in 10% formalin in PBS, decalcified in 10% EDTA at 4°C for 10 days and embedded in paraffin. Sections (4 μm) were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). For immunohistochemistry, calvaria were collected from 3 day-old cd73+/+ and cd73−/− male mice and fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, decalcified in 7.5% EDTA at 4°C for 14 days and embedded in OCT compound (Sakura Finetek Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Then 7 μm frozen sections were prepared and treated with 2.5% hyaluronidase (Sigma-Aldrich, St.Louis, MO, USA) in PBS at 37°C for 1 h, followed by inactivation of endogenous peroxidase with 0.3% H2O2 in PBS containing 0.3% FBS (NICHIREI BIOSCIENCES, Tokyo, Japan). After blocking with 3% BSA in PBS overnight at 4°C, sections were reacted with 5 μg/ml rat anti-mouse CD73 antibody (TY/23) (Yamashita et al., 1998) (BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). After washing, they were then incubated with biotin-conjugated anti-rat IgG, treated with the ABC reagents (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA), developed with DAB (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) and counterstained with hematoxylin.

Serum measurements

OC, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase isoform 5b (TRAP5b), C-teminal telopeptide of type I collagen and phosphate were measured in mouse sera collected from 13 week-old cd73+/+ and cd73−/− male mice after an overnight fast. OC was determined by sandwich ELISA using the mouse osteocalcin EIA kit (Biomedical Technologies Inc., Stoughton, MA, USA). TRAP5b level was determined by a solid phase immunofixed enzyme activity assay using the MouseTRAP Assay kit (IDS Ltd., UK). C-teminal telopeptide of type I collagen was measured by RatLaps ELISA kit (Nordic Bioscience Diagnostics, Herlev, Denmark) using a rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against a synthetic peptide having a sequence specific for a part of the C-terminal telopeptide α1 chain of rat type I collagen. Serum inorganic phosphate was determined by the improved Malachite Green method utilizing the malachite green dye and molybdate provided by the Phosphate assay kit (BioChain, Hayward, CA, USA).

Reverse Transcription (RT) -PCR

Total RNA was extracted from calvarial or femoral bones of 13 week-old cd73−/− male mice and wild type control mice by TissueLyser II (Retch, Haan D, Germany) or from in vitro cultured cells using RNA-Bee (TEL-TEST, Inc., Friendwood, TX, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified total RNA was reverse-transcribed using M-MLV (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) reverse transcriptase with random hexamers. For semiquantitative analysis, PCR was carried out using AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The primer sequences used for semiquantitative PCR are previously described (Van De Wiele et al., 2002). Real-time PCR analysis was performed using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix and a 7300 Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The primer sequences used for Real-Time PCR are listed in Table1.

Table 1.

Nucleotide sequences of primers used for PCR

| Gene | Product size(bp) |

Primer sequence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| beta actin | 171 | F | 5′- CATCCGTAAAGACCTCTATGCCAAC -3′ |

| R | 5′- ATGGAGCCACCGATCCACA -3′ | ||

| Runt related transcription factor 2 | 144 | F | 5′- CACTGGCGGTGCAACAAGA -3′ |

| R | 5′- TTTCATAACAGCGGAGGCATTTC -3′ | ||

| Bone sialoprotein | 153 | F | 5′- ATGGAGACTGCGATAGTTCCGAAG -3′ |

| R | 5′- CGTAGCTAGCTGTTACACCCGAGAG -3′ | ||

| Osteocalcin | 178 | F | 5′- AGCAGCTTGGCCCAGACCTA -3′ |

| R | 5′- TAGCGCCGGAGTCTGTTCACTAC -3′ | ||

| Alkaline phosphatase | 159 | F | 5′- ACACCTTGACTGTGGTTACTGCTGA -3′ |

| R | 5′- CCTTGTAGCCAGGCCCGTTA -3′ | ||

| CD73 (5′ nucleotidase, ecto) | 118 | F | 5′- AGTTCGAGGTGTGGACATCGTG -3′ |

| R | 5′- ATCATCTGCGGTGACTATGAATGG -3′ | ||

| Adenosine A2a receptor | 172 | F | 5′- ATTCGCCATCACCATCAGCA -3′ |

| R | 5′- ACCCGTCACCAAGCCATTGTA -3′ | ||

| Adenosine A2b receptor | 157 | F | 5′- GTCGACCGATATCTGGCCATTC -3′ |

| R | 5′- TGCTGGTGGCACTGTCTTTACTG -3′ | ||

Cell culture and transfection

Primary osteoblasts were isolated from 3 day-old pups by digesting calvarial bones in PBS containing 0.1% collagenase (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) and 0.2% dispase (Roche Applied Science) for 20 minutes at 37°C. The digestion was sequentially performed three times and cells isolated from last two digestion were cultured in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS as primary osteoblasts. MC3T3-E1 cells were obtained from the RIKEN Cell Bank (Tsukuba, Japan). Cells were maintained in α-MEM (Nikken Biomedical Laboratory, Kyoto, Japan) supplemented with 10% FBS and 60 μg/ml kanamycin. To induce differentiation, cells were cultured in a 24-well plate until they reached confluence and then switched to mineralization medium (α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate and 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid) which was replaced every 3 days.

To produce stable transfectants, 2×104 MC3T3-E1 cells/well were plated in a 24 well plate and after 24 h, were transfected with the pHβ Apr-1-neo-cd73 expression vector (Resta et al., 1994) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. After 24 h, the culture medium was supplemented with 600 μg/ml geneticin (Invitrogen) to initiate drug selection. After selection, we then established the stable transfectant over expressing CD73 (MC/CD73). Cells used in this study had been passaged 3-5 times.

Colony forming assay

Bone marrow cells were flushed with PBS from femurs and tibias of 13 week-old cd73+/+ and cd73−/− mice. One million bone marrow cells/well were plated in a 6 well plate and cultured in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS for 14 days. The cells were fixed with methanol and stained with Giemsa (Wako Pure Chemical Industries). Colonies with >20 cells were counted as fibroblast colony forming units (CFU-F). To enumerate osteoblast colony forming units (CFU-OB), bone marrow cells were cultured in mineralization media for 10 days and fixed with ethanol. Formation of osteoblast progenitors were detected using an ALPase staining kit (Sigma-Aldrich) and ALPase positive colonies with >20 cells were counted. Then Giemsa staining was performed and total colonies were counted. CFU-OB was calculated as a ratio of ALPase positive colonies/total colonies.

Flow cytometry analysis

Single cell suspensions of MC/CD73 or control transfectants were prepared by trypsinization and reacted with 10 μg/ml PE-conjugated rat anti-CD73 antibody TY/23 (BD Pharmingen) or an isotype-matched control antibody. Data were collected with a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and analyzed with CellQuest software.

Proliferation assay

Proliferation of MC/CD73 and control transfectants was measured using the nonradioactive colorimetric WST-1 Cell Proliferation Assay (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This assay is based on the cleavage of a tetrazolium salt by mitochondrial dehydrogenases to form formazan in viable cells. Briefly, 1×104 cells were plated in 24 well plates and cultured in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS. The number of viable cells was determined by adding WST-1 reagent and colorimetric evaluation of OD450/630 by a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) after 30 min incubation.

ALPase Activity

After washing twice with PBS, the cells were sonicated in 0.01 M Tris/HCl (pH 7.4) and then centrifuged for 5 min at 12,000 g. Subsequently the supernatant was mixed with 0.5 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 9.0) containing 0.5 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate as substrate, 0.5 mM MgCl2 and 0.006% Triton X-100. Then the samples were incubated at room temperature for 60 min, and the reaction was stopped by addition of 0.2 M NaOH. The hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl phosphate was monitored as a change in OD410. ALPase from bovine intestinal mucosa was used as a standard and one unit of activity was defined as the enzyme activity hydrolyzing 1 μmol of p-nitrophenyl phosphate per min at pH 9.8 at 37°C. Protein concentration was determined by Lowry method and the results were expressed as mU/μg protein.

Mineralization assay

Histochemical staining of calcified nodules was performed with alizarin red S. Cell monolayers were washed twice with PBS, and then fixed with dehydrated ethanol. After fixation, the cell layers were stained with 1% alizarin red S in 0.1% NH4OH (pH 6.5) for 5 min, then washed with H2O.

cAMP measurement

Cells were washed with serum-free α-MEM and treated with 0.1% DMSO (as carrier) or 10 nM - 1 μM of the A2AAR antagonist ZM241385 (Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO, USA) or 10 nM - 1 μM of the A2BAR antagonist MRS1754 (Sigma-Aldrich). After 10 min incubation, cells were stimulated with 100 μM adenosine (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min. Intracellular cAMP was determined by competition between cAMP of cells and cAMP conjugated to ALPase detected by rabbit polyclonal antibody to cAMP using a cyclic AMP complete EIA kit (Assay designs, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Protein concentration was determined by the Lowry method and the cAMP results were expressed in pmol/mg protein.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the mean ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed by Student’s t-test. In some experiments, statistical analyses were performed by one-way ANOVA and specific differences were identified by the Bonferroni test: p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

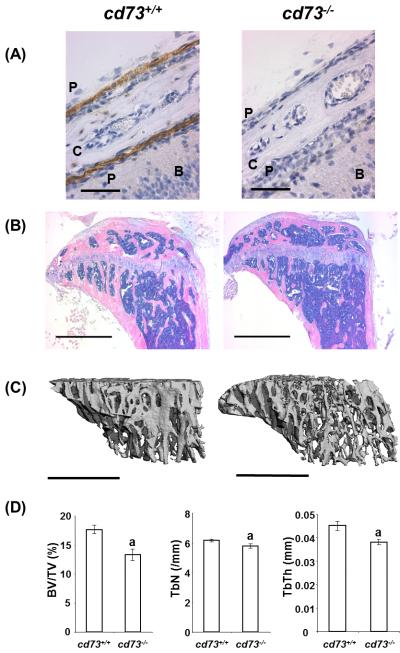

CD73 is expressed in periosteal osteoblasts

To determine where CD73 is expressed in bone tissue, frozen sections of calvaria specimens from 3 day-old cd73+/+ mice were examined. Incubation with anti-CD73 antibody (TY/23) demonstrated that periosteum containing osteoblast and osteoblast precursors expressed CD73 (Fig. 1A). In contrast, no CD73 expression was observed in the periosteum of cd73−/− mice.

Figure 1.

cd73−/− mice exhibit osteopenia

To examine the skeletal phenotype of 13 week-old cd73−/− mice, we first evaluated the bone mineral density by pQCT. Compared to control littermates, male cd73−/− mice had significantly lower bone mineral content in the trabecular bone of the femur metaphysis (Table 2). No differences were observed in the trabecular bone of female cd73−/− or cortical bone of either male or female mice at the femur diaphysis. Histological evaluation of the proximal tibias showed that cd73−/− male mice exhibited small and scattered bone spicules in the proximal metaphysis area compared with sex-matched wild type mice (Fig. 1B).

Table 2.

Cortical and trabecular bone mineral density at the distal femur metaphysis and body weights of cd73−/− and cd73+/+ male and female mice

| genotype | bone mineral density (mg/cm3) | body weight (g) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| trabecular bone | cortical bone | |||

| male | CD73+/+ | 271.15±23.09 | 1081.48±18.77 | 27.32±1.57 |

| CD73−/− | 246.13±13.78a | 1070.55±25.78 | 27.52±1.48 | |

| female | CD73+/+ | 206.23±23.03 | 1051.62±18.13 | 19.23±2.14 |

| CD73−/− | 207.39±21.65 | 1055.03±20.64 | 19.43±0.64 | |

p<0.05 compared with cd73+/+ mice.

Quantitative analyses of trabecular bone were accomplished using μCT. Representative three-dimensional images reconstructed from μCT scans of trabecular bone at the proximal tibia metaphysis further demonstrated osteopenia in male cd73−/− mice (Fig. 1C). These changes were characterized by reduced trabecular bone volume, decreased trabecular number and thickness (Fig. 1D) and increased trabecular separation (data not shown) in cd73−/− mice.

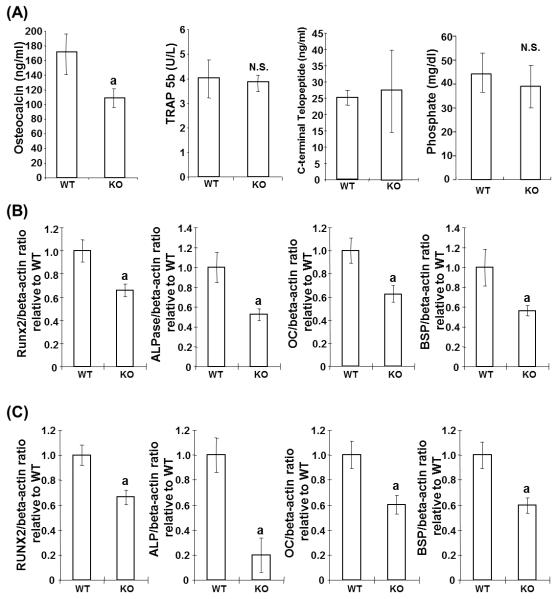

cd73−/− mice exhibit decreased bone formation and osteoblast differentiation in vivo

We then investigated whether osteopenia in male cd73−/− mice was the result of impaired bone formation or activated bone resorption. To address this question, we measured biochemical markers of in vivo bone turnover. As shown in Fig. 2A, a significant decrease in serum OC, a metabolic marker of in vivo bone formation (Hauschka et al., 1989), was observed in cd73−/− mice. In contrast, levels of the osteoclast marker TRAP5b (Alatalo et al., 2003) and fragments of type I collagen (C-terminal telopeptide), the products of bone resorption (Garnero et al., 2003), were comparable in the two strains of mice.

Figure 2.

To further substantiate the involvement of impaired osteoblasts in the phenotype of cd73−/− mice, we investigated the gene expression of osteoblast markers in calvarial and femoral bones. Real time PCR analysis demonstrated significantly decreased expression of Runx2, ALPase, OC and BSP in calvarial and femoral bones of cd73−/− mice (Fig. 2B, C). These results suggested that the involvement of CD73 in bone homeostasis was directed to the osteoblast.

Inorganic phosphate required for osteoblast differentiation and mineralization (Beck, 2003) is produced when CD73 catalyzes the conversion of adenosine monophosphate to adenosine. To examine if decreased inorganic phosphate contributed to the reduction in trabecular bone volume in cd73−/− mice, serum phosphate was determined. As shown in Fig.2A, serum phosphate in cd73−/− mice was similar to that in cd73+/+ mice, suggesting that CD73 has a minor role in production of phosphates.

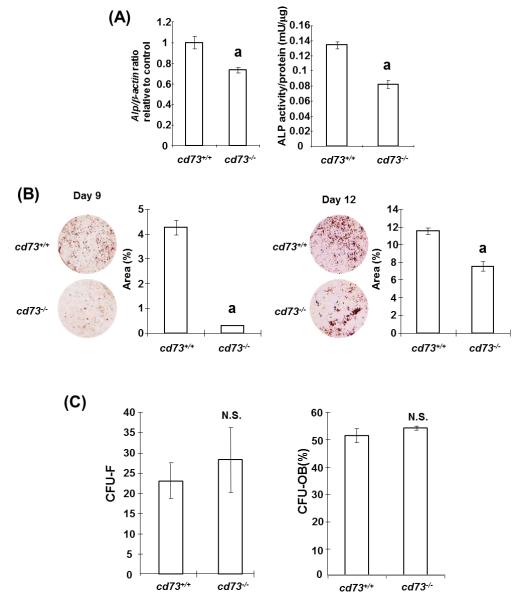

CD73 deficiency impairs osteoblast differentiation in vitro

Ex vivo studies were performed to identify the role of CD73 in osteoblasts differentiation and mineralization. Primary osteoblasts were isolated from calvarial bones of cd73+/+ mice and cd73−/− mice and cultured in mineralization medium to examine the role of CD73 in osteoblast differentiation. As shown Fig. 3A, ALPase mRNA expression and activity were significantly decreased in CD73-deficient osteoblasts compared to wild type osteoblasts at 6 days of culture. Moreover, calcified nodule formation was delayed in cultures from cd73−/− mice, suggestive of reduced mineralization (Fig.3B).

Figure 3.

Because A2AAR is reported to play a role in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell development (Katebi et al., 2009), we assessed the number of bone marrow stem cells and osteoblast progenitors in bone marrow of cd73−/− mice. Colony forming assays revealed that bone marrow cells cultured from cd73−/− mice formed similar numbers of fibroblast colonies and ALPase positive osteoblast colonies compared to cultures from cd73+/+ mice (Fig.3C). Taken together, our results suggested that CD73 plays a role in osteoblast differentiation but not in the development of osteoblast progenitors.

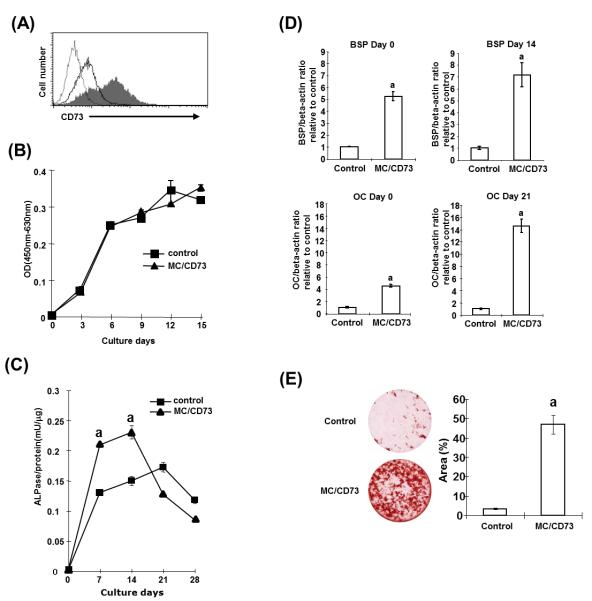

Osteoblast differentiation is accelerated in MC3T3-E1 cells over expressing CD73

To investigate the mechanism by which CD73 promotes osteoblast differentiation, we established MC3T3-E1 cells over expressing CD73 (MC/CD73) by transfecting with pHβ Apr-1-neo-cd73. Increased expression of CD73 in MC/CD73 is shown in Fig. 4A. MC/CD73 cells exhibited normal cell shape (data not shown) and comparable proliferative ability (Fig. 4B). To examine the effects of CD73 over expression on differentiation, we cultured MC/CD73 cells in mineralization medium and assessed ALPase activity at weekly intervals. ALPase activity was significantly higher at day 7 and day 14 compared with control transfectants (Fig. 4C). However after reaching peak activity on day 14, the ALPase activity of the MC/CD73 cells decreased more rapidly in the late stages of culture.

Figure 4.

We next examined the expression of BSP and OC in MC/CD73 cells as differentiation markers of mature osteoblasts. As shown in Fig. 4D, mRNA expression of BSP and OC was significantly higher in MC/CD73 cells compared with control transfectants, even when cells were cultured in normal culture medium, suggesting that over expression of CD73 promoted osteogenic potential. Elevated BSP and OC gene expression was further enhanced by cultivation in mineralization medium. Moreover, alizarin red S staining showed increased calcified nodule formation in MC/CD73 cells after 28 days of culture (Fig. 4E). These observations support the findings from primary osteoblast cultures that CD73 has a positive role in osteoblast differentiation and function.

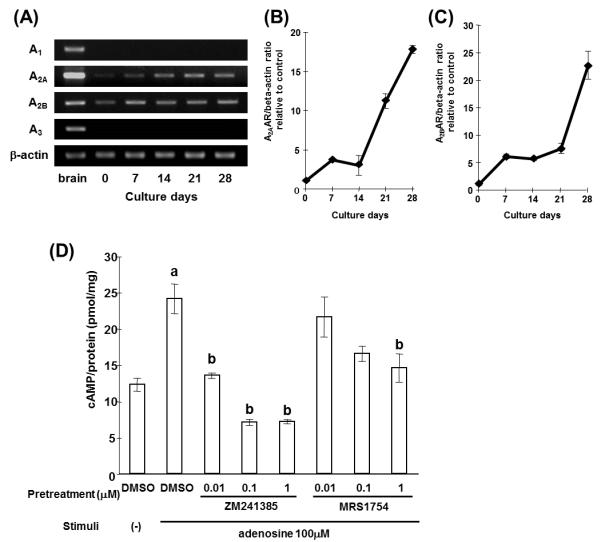

Adenosine receptor expression increases during osteoblastic differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells

As CD73 is a major enzyme generating extracellular adenosine, we next evaluated AR expression on MC3T3-E1 cells. We performed RT-PCR analysis of each subtype of AR using RNAs isolated from the MC3T3-E1 cells cultured with mineralization medium. As shown in Fig. 5A, expression of A2AAR and A2BAR were increased during culture in mineralization medium, and strong expression was observed in the later stages of osteoblast differentiation. Real-time PCR analysis confirmed the increase of A2AAR and A2BAR mRNA expression (Fig. 5B, C). In contrast, A1AR and A3AR mRNA were not detected throughout the culture by RT-PCR. To confirm the functional expression of A2AAR and A2BAR on MC3T3-E1 cells, cells were stimulated with exogenous adenosine in the presence or absence of A2AAR and A2BAR antagonists (ZM241385 and MRS1754, respectively) and cAMP, the second messenger of both receptors, was measured. Significant increases of cAMP were observed by adding 100 μM adenosine to cells that had been cultured for two weeks in mineralization medium. This response to adenosine was suppressed in a dose dependent manner by an A2AAR or A2BAR antagonist (Fig. 5D). These results demonstrated that differentiating osteoblasts express functional A2AAR and A2BAR and that their expression increases with differentiation.

Figure 5.

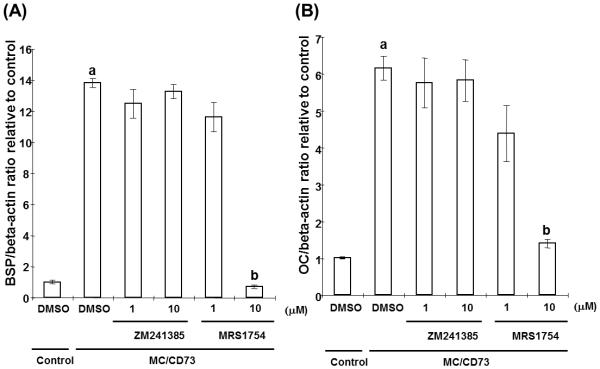

CD73-generated adenosine stimulates osteoblasts via A2BAR signaling

Having demonstrated functional A2AAR and A2BAR on MC3T3-E1 cells, we next utilized ZM241385 and MRS1754 to determine if one or both of these receptors is involved in the CD73-induced alterations in osteoblast differentiation. As shown in Fig. 6A, B, enhanced gene expression of BSP and OC in MC/CD73 was significantly suppressed by treatment with an A2BAR antagonist. Surprisingly, an A2AAR antagonist had no effects on the BSP and OC gene expression of MC/CD73. It is important to note that A2AAR and A2BAR mRNA expression on MC3T3-E1 was not changed by over expression of CD73 (data not shown). These data suggest that CD73-generated adenosine modulates osteoblast differentiation and function via activation of A2BAR.

Figure 6.

Discussion

Adenosine has a plethora of biological actions on a large variety of cells and modulates their function. Cells responsible for bone remodeling are no exception. In vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that formation and function of osteoclasts responsible for bone resorption require A1AR signaling (Kara et al., 2010a; Kara et al., 2010b). In vitro studies showed proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts responsible for bone formation could be modulated by AR signaling (Costa et al., 2010; Costa et al., 2011; Fatokun et al., 2006; Shimegi, 1998). Extracellular adenosine which activates AR is generated, at least in part, by ecto-5′-nucleotidse: CD73. The expression of this molecule is regulated by the canonical Wnt and HIF-1α pathways, crucial signaling cascades in bone forming cells (Spychala and Kitajewski, 2004; Synnestvedt et al., 2002). Thus, the possibility that CD73 could impact osteoblast function by modulating nucleotide metabolism and adenosine concentrations prompted us to examine the role of this molecule in bone metabolism.

Significantly decreased serum OC and suppressed osteoblastic gene expression in bone of male cd73−/− mice suggest that their reduced bone volume is due to, at least in part, to a defect of osteoblast function (Fig. 2). As CD73 plays a major role in extracellular adenosine generation, this is the first report indicating the involvement of endogenous adenosine in osteoblast function in vivo. A better understanding of the specific role of adenosine can be gained by a detailed analysis of the phenotype observed in cd73−/− mice. Unlike cortical bone, trabecular bone volume and trabecular thickness were significantly reduced (29.5% and 17.9% reduction, respectively) in cd73−/− mice as compared to wild type mice. Likewise, bone mineral density was significantly reduced in the trabecular rich metaphysis but was not statistically reduced in cortical bone. These findings suggest bone microenvironmental-specific (trabecular vs cortical regions) requirements for CD73. Additionally, whole mount staining with alcian blue and alizarin red of E18.5 fetal skeletions, revealed no significant abnormalities between cd73−/− and wild type embryos (data not shown). These data reveal that CD73 is not required for embryonic bone patterning or initial bone formation but is most likely required for bone remodeling that occurs with age. In this study, we showed that CD73 deficiency resulted in osteopenia in male mice but not in female mice at 13 weeks of age. Mature male and female mice are known to show different bone status and remodeling rates. Thus, there may be an interaction between CD73-generated adenosine and one or more age-dependent factors such as sex hormones. Exploring this interaction will be a topic of future work.

In this study, a series of in vitro studies revealed that CD73 promoted osteoblast differentiation, consistent with earlier reports indicating that AR activation regulated proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts in vitro (Costa et al., 2011; Shimegi, 1998). The relatively modest bone phenotype of cd73−/− mice may be due to redundant pathways of adenosine production such as via cytoplasmic nucleotidases or S-adenosyl homocysteine hydrolase. As it is possible that some of these pathways could be up regulated as a consequence of life-long CD73 deficiency, it would be interest to compare the bone phenotype in mice with conditional CD73 deficiency when they become available.

Unlike previous reports suggesting that adenosine supports osteoclast formation and bone resorption (Evans et al., 2006; Kara et al., 2010a; Kara et al., 2010b), we found osteoclast markers were normal in cd73−/− mice in the steady state (Fig. 2A) and TRAP staining of tibia showed comparable osteoclast numbers in wild type and cd73−/− mice (data not shown). However, CD73-generated adenosine may modulate osteoclast formation and function during inflammatory bone diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis, because inflammatory cytokines are capable of inducing CD73 expression (Kalsi et al., 2002; Niemelä et al., 2004) and adenosine is a well-known anti-inflammatory mediator (Blackburn et al., 2009; Haskó et al., 2008). Future studies utilizing cd73−/− mice in experimental bone disease models will give us more insight into the role of CD73 and endogenous adenosine in the pathogenesis of these diseases.

Elevation of A2AAR and A2BAR expression was observed during osteogenic differentiation (Fig. 5). These subtypes of AR are coupled with Gs proteins that can initiate signaling to stimulate bone formation (Hsiao et al., 2008; Sakamoto et al., 2005). Interestingly the positive role of CD73 on osteoblast differentiation in vitro was mediated by the A2BAR but not the A2AAR (Fig. 6A, B). Our experiments do not rule out the possibility that the A2AAR functions in osteoblast differentiation in vivo independently of CD73; additional experiments with gene targeted mice will be necessary to address this issue. Based on our data, we hypothesize that CD73-generated adenosine stimulates the A2BAR but not the A2AAR or that A2AAR signaling is not coupled to osteogenic pathways. This idea is supported by reduced bone volume in A2BAR deficient mice (data not shown) and previous studies that demonstrated a tight relationship between CD73 and the A2BAR in endothelial and epithelial cell function (Eckle et al., 2007; Eltzschig et al., 2003; Lennon et al., 1998; Strohmeier et al., 1997; Takedachi et al., 2008). Although the mechanism by which CD73-generated adenosine activates the A2BAR is not known yet, we speculate that the proximity between the A2BAR and CD73 on microdomains of the plasma membrane may lead to efficient activation of the A2BAR by CD73-generated adenosine.

In conclusion, we propose that endogenous adenosine generated by CD73 promotes osteoblast differentiation via A2BAR signaling. The A2BAR is a seven-transmembrane - spanning G protein - coupled receptor that is coupled to Gs and uses cAMP as a second messenger. It has been reported that cAMP promotes osteoblast function and the anabolic action of bone formation by enhancement of bone morphogenetic protein signaling (Nakao et al., 2009). Experiments are now ongoing to further define the role of the A2BAR in osteoblast differentiation. Together with our findings in this study, such information may lead to the development of new anabolic therapeutic targets for bone diseases.

Acknowledgments

MT is a research fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. LFT holds the Putnam City Schools Distinguished Chair in Cancer Research. The authors thank Stephanie McGee, Patrick Marble, and Emiko Maeda for excellent technical assistance.

Contact grant sponsor: Ministry of Education, Science, Technology, Sports and Culture of Japan Grant number: No.2110452

Contact grant sponsor: NIH Grant number: AI18220, DE19398

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest All authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alatalo S, Peng Z, Janckila A, Kaija H, Vihko P, Vaananen H, Halleen J. A novel immunoassay for the determination of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b from rat serum. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(1):134–139. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R, Rawadi G, Roman-Roman S. Wnt signaling: a key regulator of bone mass. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2006;76:103–127. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(06)76004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck GR. Inorganic phosphate as a signaling molecule in osteoblast differentiation. J Cell Biochem. 2003;90(2):234–243. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn M, Vance C, Morschl E, Wilson C. Adenosine receptors and inflammation. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;(193):215–269. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-89615-9_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley K, Golding S, Rice J, Dillon J, Gallagher J. Release and interconversion of P2 receptor agonists by human osteoblast-like cells. FASEB J. 2003;17(11):1401–1410. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0940com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M, Barbosa A, Neto E, Sá-E-Sousa A, Freitas R, Neves J, Magalhães-Cardoso T, Ferreirinha F, Correia-de-Sá P. On the role of subtype selective adenosine receptor agonists during proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of human primary bone marrow stromal cells. J Cell Physiol. 2010 doi: 10.1002/jcp.22458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa MA, Barbosa A, Neto E, Sá-e-Sousa A, Freitas R, Neves JM, Magalhães-Cardoso T, Ferreirinha F, Correia-de-Sá P. On the role of subtype selective adenosine receptor agonists during proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of human primary bone marrow stromal cells. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226(5):1353–1366. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckle T, Krahn T, Grenz A, Köhler D, Mittelbronn M, Ledent C, Jacobson M, Osswald H, Thompson L, Unertl K, Eltzschig H. Cardioprotection by ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) and A2B adenosine receptors. Circulation. 2007;115(12):1581–1590. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.669697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltzschig H, Ibla J, Furuta G, Leonard M, Jacobson K, Enjyoji K, Robson S, Colgan S. Coordinated adenine nucleotide phosphohydrolysis and nucleoside signaling in posthypoxic endothelium: role of ectonucleotidases and adenosine A2B receptors. J Exp Med. 2003;198(5):783–796. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans B, Elford C, Pexa A, Francis K, Hughes A, Deussen A, Ham J. Human osteoblast precursors produce extracellular adenosine, which modulates their secretion of IL-6 and osteoprotegerin. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(2):228–236. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.051021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatokun A, Stone T, Smith R. Hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in MC3T3-E1 cells: The effects of glutamate and protection by purines. Bone. 2006;39(3):542–551. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnero P, Ferreras M, Karsdal M, Nicamhlaoibh R, Risteli J, Borel O, Qvist P, Delmas P, Foged N, Delaissé J. The type I collagen fragments ICTP and CTX reveal distinct enzymatic pathways of bone collagen degradation. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(5):859–867. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.5.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol MW, Panupinthu N, Korcok J, Sims SM, Dixon SJ. Expression, signaling, and function of P2X7 receptors in bone. Purinergic Signal. 2009;5(2):205–221. doi: 10.1007/s11302-009-9139-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskó G, Linden J, Cronstein B, Pacher P. Adenosine receptors: therapeutic aspects for inflammatory and immune diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(9):759–770. doi: 10.1038/nrd2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauschka P, Lian J, Cole D, Gundberg C. Osteocalcin and matrix Gla protein: vitamin K-dependent proteins in bone. Physiol Rev. 1989;69(3):990–1047. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1989.69.3.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao E, Boudignon B, Chang W, Bencsik M, Peng J, Nguyen T, Manalac C, Halloran B, Conklin B, Nissenson R. Osteoblast expression of an engineered Gs-coupled receptor dramatically increases bone mass. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(4):1209–1214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707457105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalsi K, Lawson C, Dominguez M, Taylor P, Yacoub M, Smolenski R. Regulation of ecto-5′-nucleotidase by TNF-alpha in human endothelial cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;232(1-2):113–119. doi: 10.1023/a:1014806916844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kara F, Doty S, Boskey A, Goldring S, Zaidi M, Fredholm B, Cronstein B. Adenosine A(1) receptors regulate bone resorption in mice: Adenosine A(1) receptor blockade or deletion increases bone density and prevents ovariectomy-induced bone loss in adenosine A(1) receptor-knockout mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2010a;62(2):534–541. doi: 10.1002/art.27219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kara FM, Chitu V, Sloane J, Axelrod M, Fredholm BB, Stanley ER, Cronstein BN. Adenosine A1 receptors (A1Rs) play a critical role in osteoclast formation and function. FASEB J. 2010b;24(7):2325–2333. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-147447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katebi M, Soleimani M, Cronstein BN. Adenosine A2A receptors play an active role in mouse bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell development. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85(3):438–444. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0908520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon P, Taylor C, Stahl G, Colgan S. Neutrophil-derived 5′-adenosine monophosphate promotes endothelial barrier function via CD73-mediated conversion to adenosine and endothelial A2B receptor activation. J Exp Med. 1998;188(8):1433–1443. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao Y, Koike T, Ohta Y, Manaka T, Imai Y, Takaoka K. Parathyroid hormone enhances bone morphogenetic protein activity by increasing intracellular 3′, 5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate accumulation in osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells. Bone. 2009;44(5):872–877. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.01.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemelä J, Henttinen T, Yegutkin G, Airas L, Kujari A, Rajala P, Jalkanen S. IFN-alpha induced adenosine production on the endothelium: a mechanism mediated by CD73 (ecto-5′-nucleotidase) up-regulation. J Immunol. 2004;172(3):1646–1653. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orriss IR, Burnstock G, Arnett TR. Purinergic signalling and bone remodelling. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10(3):322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piters E, Boudin E, Van Hul W. Wnt signaling: a win for bone. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;473(2):112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50(3):413–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resta R, Hooker S, Laurent A, Shuck J, Misumi Y, Ikehara Y, Koretzky G, Thompson L. Glycosyl phosphatidylinositol membrane anchor is not required for T cell activation through CD73. J Immunol. 1994;153(3):1046–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanello M, Pani B, Bicego M, D’Andrea P. Mechanically induced ATP release from human osteoblastic cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;289(5):1275–1281. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto A, Chen M, Nakamura T, Xie T, Karsenty G, Weinstein L. Deficiency of the G-protein alpha-subunit G(s)alpha in osteoblasts leads to differential effects on trabecular and cortical bone. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(22):21369–21375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500346200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimegi S. Mitogenic action of adenosine on osteoblast-like cells, MC3T3-E1. Calcif Tissue Int. 1998;62(5):418–425. doi: 10.1007/s002239900454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spychala J, Kitajewski J. Wnt and beta-catenin signaling target the expression of ecto-5′-nucleotidase and increase extracellular adenosine generation. Exp Cell Res. 2004;296(2):99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohmeier G, Lencer W, Patapoff T, Thompson L, Carlson S, Moe S, Carnes D, Mrsny R, Madara J. Surface expression, polarization, and functional significance of CD73 in human intestinal epithelia. J Clin Invest. 1997;99(11):2588–2601. doi: 10.1172/JCI119447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synnestvedt K, Furuta G, Comerford K, Louis N, Karhausen J, Eltzschig H, Hansen K, Thompson L, Colgan S. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) regulation by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates permeability changes in intestinal epithelia. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(7):993–1002. doi: 10.1172/JCI15337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takedachi M, Qu D, Ebisuno Y, Oohara H, Joachims M, McGee S, Maeda E, McEver R, Tanaka T, Miyasaka M, Murakami S, Krahn T, Blackburn M, Thompson L. CD73-generated adenosine restricts lymphocyte migration into draining lymph nodes. J Immunol. 2008;180(9):6288–6296. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson L, Eltzschig H, Ibla J, Van De Wiele C, Resta R, Morote-Garcia J, Colgan S. Crucial role for ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) in vascular leakage during hypoxia. J Exp Med. 2004;200(11):1395–1405. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson L, Ruedi J, Glass A, Moldenhauer G, Moller P, Low M, Klemens M, Massaia M, Lucas A. Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies to the glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored lymphocyte differentiation antigen ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) Tissue Antigens. 1990;35(1):9–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1990.tb01750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van De Wiele CJ, Vaughn JG, Blackburn MR, Ledent CA, Jacobson M, Jiang H, Thompson LF. Adenosine kinase inhibition promotes survival of fetal adenosine deaminase-deficient thymocytes by blocking dATP accumulation. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(3):395–402. doi: 10.1172/JCI15683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volmer J, Thompson L, Blackburn M. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73)-mediated adenosine production is tissue protective in a model of bleomycin-induced lung injury. J Immunol. 2006;176(7):4449–4458. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan C, Gilbert S, Wang Y, Cao X, Shen X, Ramaswamy G, Jacobsen K, Alaql Z, Eberhardt A, Gerstenfeld L, Einhorn T, Deng L, Clemens T. Activation of the hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha pathway accelerates bone regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(2):686–691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708474105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wan C, Deng L, Liu X, Cao X, Gilbert S, Bouxsein M, Faugere M, Guldberg R, Gerstenfeld L, Haase V, Johnson R, Schipani E, Clemens T. The hypoxia-inducible factor alpha pathway couples angiogenesis to osteogenesis during skeletal development. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(6):1616–1626. doi: 10.1172/JCI31581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B, Insogna K. Where Wnts went: the exploding field of Lrp5 and Lrp6 signaling in bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24(2):171–178. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita Y, Hooker SW, Jiang H, Laurent AB, Resta R, Khare K, Coe A, Kincade PW, Thompson LF. CD73 expression and fyn-dependent signaling on murine lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28(10):2981–2990. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199810)28:10<2981::AID-IMMU2981>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yegutkin G. Nucleotide- and nucleoside-converting ectoenzymes: Important modulators of purinergic signalling cascade. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783(5):673–694. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]