Abstract

Objective

We assessed barriers and facilitators to uptake of the intrauterine device (IUD) among primiparous African American adolescent mothers.

Study Design

Twenty participants who expressed IUD desire completed 4–5 qualitative interviews during the first postpartum year as part of a larger longitudinal study. Transcripts were analyzed for salient themes using a grounded theory approach to content analysis.

Results

Twelve participants did not obtain IUDs and instead used condoms, used no method, or intermittently used hormonal methods, resulting in 3 repeat pregnancies. Outdated IUD eligibility requirements, long wait times, lack of insurance coverage and fear of IUD-related side effects precluded or delayed uptake. Facilitators to IUD uptake included strong recommendations from providers or family members, planning for IUD during pregnancy, and perceived reproductive autonomy.

Conclusions

Postpartum adolescents may reduce their risk of rapid repeat pregnancy by using IUDs. Providers and members of adolescents’ support networks can be instrumental in method adoption.

Keywords: Adolescent, African Americans, Intrauterine Devices, Postpartum Period, Qualitative

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

The United States has the highest adolescent birth rate in the developed world.1 Rapid repeat pregnancy (RRP), occurring within 24 months of the previous birth, is experienced by 20–66% of adolescent mothers, and increases the risk of poor maternal and fetal outcomes, unemployment and poverty.2–5 National birth data indicate higher rates of RRP among African American adolescents (23%) compared to White adolescents (17%).6 Reducing the proportion of rapid repeat pregnancies among women in the United States, including adolescents, is a Healthy People 2020 objective.7

Interventions to reduce RRP among adolescents have featured home visiting, motivational counseling, mentoring, and monetary incentives. While some recent achievements have been noted,8, 9 these programs have not demonstrated consistent success and some researchers have called for the promotion of long-acting contraception methods for at-risk adolescents.5, 10–12 Indeed, studies have shown that adolescent mothers who initiate longer-acting, reversible contraceptive methods (i.e., depot medroxyprogesterone acetate [DMPA] or progestin-only implants) immediately after delivery have a lower risk of RRP and higher method continuation rate at 12 months compared to those who adopt shorter-acting methods like oral contraceptive pills or the contraceptive patch.13–16

The intrauterine device (IUD) is an ideal postpartum method because it does not interfere with lactation, facilitates adequate birth spacing and does not require repeat health care visits for contraceptive refills. A recent committee opinion by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends the IUD as a first-line choice for adolescents.17 Despite its potential benefits, the IUD remains underused in the United States by women of all age groups18 and research has demonstrated barriers for postpartum and adolescent populations. A retrospective study found that only 60% of postpartum women who requested an IUD obtained the device, waiting an average of 60.5 days post-delivery for insertion.19 Providers may limit IUD use among adolescents by citing concerns about infection, expulsion, and infertility.20, 21

The purpose of this research is to better understand barriers to IUD uptake by postpartum adolescents. Through longitudinal qualitative interviews, we identify factors that prevent, delay or support uptake of the IUD among postpartum adolescents who expressed desire to obtain the IUD. We focus exclusively on African Americans to provide rich information on a subset of the adolescent postpartum population at high risk for RRP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This analysis uses data from the Postpartum Adolescent Birth Control Study (Postpartum ABCs), a longitudinal study of first-time African American adolescent mothers. Participants were recruited through referral from physicians, social workers, labor and delivery nurses, housing programs, community-based programs, and schools in the Chicago area serving pregnant adolescents. Toward the end of the study we used snowball sampling to recruit participants in order to accelerate progress toward enrollment targets; four participants enrolled in the study through this mechanism. Eligible participants were 14–18 years old at childbirth, primiparous, African American, ≤9 weeks postpartum, and living in Chicago. Following enrollment, we conducted qualitative, semi-structured interviews at 4–9 weeks (baseline), 3 months, 6 months, 9 months and 12 months postpartum. Eligibility criteria were relaxed for four participants who enrolled later in the postpartum period (i.e., 11–13 weeks) and thus completed a combined baseline/3-month interview, for a total of 4 total interviews. Forty participants enrolled in the study and completed a baseline interview. Interview completion rates at each study visit were 100%, 90%, 85%, 85%, and 80%, respectively, with 31 (78%) participants completing all study visits. Participants received $20 for each completed interview. We obtained written informed consent from all participants and parental consent for those younger than 18 years old. The Institutional Review Board at The University of Chicago approved the research protocol.

Female research staff conducted 45 to 90-minute interviews in a private space in the participants’ homes. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim by study staff or a professional service. The interview guide was derived through formative research consisting of two focus groups with young African American women who had given birth as adolescents. Based on findings from these sessions, the longitudinal interviews explored the following topics: contraceptive use and attitudes; postpartum physical changes; relationship dynamics with parents, peers, and partners; educational and vocational goals; and neighborhood safety.

This analysis focuses on the section of the interview in which participants were asked about their use of contraception. From the larger study sample of 40 participants, we restricted the analysis cohort to participants who expressed both desire for and intention to obtain the IUD in at least one interview. Those missing more than three interviews (n=2) were excluded from this analysis, given its focus on longitudinal outcomes. This resulted in 20 participants: 19 who completed all study visits and one who missed only her 3-month visit. We used ATLAS.ti 5.0 (Scientific Software Development, GmbH, Berlin, Germany), a qualitative data analysis software program, to code and assist in data analysis. Research staff developed an initial code dictionary of concepts pertaining to contraceptive use and postpartum well-being using the interview guide. At least two researchers coded each transcript, adding new codes for emerging concepts based on a grounded theory approach.22 Rare coding discrepancies were resolved through discussion. We then constructed matrices based on salient themes – those appearing in multiple interviews – to facilitate in-depth analysis and synthesis.23

RESULTS

The participants were 18 (n=8), 17 (n=6), 16 (n=5) or 15 (n=1) years old. Most (n=12) identified as Baptist and as being “somewhat religious” (n=15). Half reported that their mothers first became pregnant when they were 18 or younger.

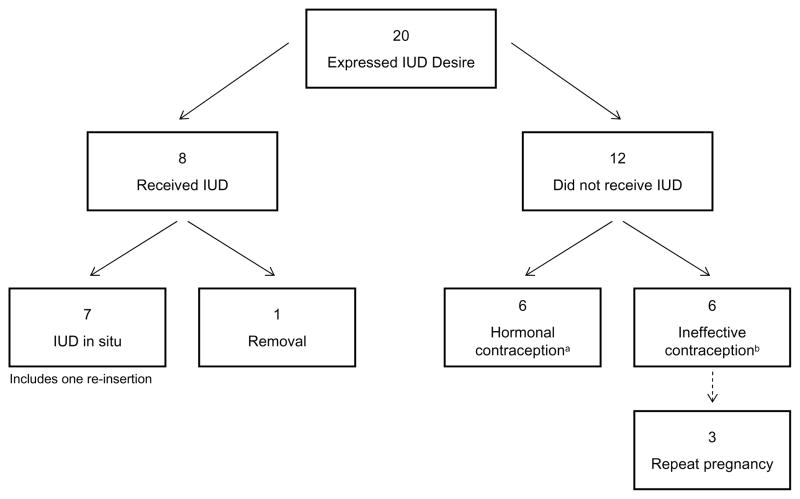

Contraceptive and pregnancy outcomes of the 20 participants are in Figure 1. Almost all participants expressed their IUD desire early in the postpartum period, at the baseline or 3-month interview. The 8 participants who successfully received an IUD obtained it within 6 weeks (n=3), 3–4 months (n=2) and 5–6 months (n=3) postpartum. All were using the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. One participant had her IUD removed due to pain. Another participant had her device removed after downward displacement into the cervical canal. She obtained her second IUD a month later and used the vaginal ring in the interim. Twelve did not receive an IUD within the 12-month study period; three of these adolescents experienced a repeat pregnancy. Most used condoms or withdrawal in the interim and struggled with adherence to these and other methods, including oral contraceptive pills and the vaginal ring.

Figure 1.

Contraceptive and reproductive outcomes of the study cohort over 12 months

aParticipants who predominantly used hormonal contraception during 12-month follow-up; includes 5 DMPA users and one DMPA/ring user.

bParticipants who predominantly used condoms and/or withdrawal during 12-month follow-up; includes 2 short-term users of oral contraceptive pills.

Our qualitative data revealed a number of barriers and facilitators to IUD uptake among postpartum adolescents. Barriers fell within three major domains: service-level obstacles (insurance, clinic access and providers); fears and concerns (including those influenced by peers, families, and partners); and shifting birth control preferences. Facilitators to IUD use reflected similar domains including helpful clinic procedures and providers; the influence of family, friends and partners; and failed attempts at using other contraceptive methods. Findings are described below and summarized in Tables 1–3, where we provide representative participant quotations for each theme along with contraceptive and pregnancy outcomes for quoted participants.

Table 1.

Service-level obstacles to IUDs

| Barrier | Participant Quotations | Participant Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Insurance coverage for device and insertion | I told them that the people hadn’t send me my medical card, they told me when they send the medical card then I come in and they gonna… set me up for an appointment. (Age 17) | Never got IUD; used condoms and had repeat pregnancy. |

| Scheduling and attending appointments | But I ain’t never went up there, so I was having so much stuff… to do. So much stuff. (Age 17) | Never got IUD; used condoms. |

| I missed my appointment… last month but I couldn’t do it ‘cause I couldn’t afford to miss any more days out of school. (Age 18) | Never got IUD; used condoms/OCPs. | |

| Referrals | When I talked to the lady that be up in the department, she was telling me I had to go to my doctor and get a note stating that I wanted to get an IUD. (Age 17) | Never got IUD; used condoms and had repeat pregnancy. |

| Clinic mobility | Because every time I had a doctor’s appointment to get it, it was always something else. Like they were always moving the clinics and stuff. So I just started to take the pill. (Age 18) | Used OCPs until IUD at 9 months postpartum. |

| Provider inexperience with IUD insertion | I asked my doctor about it but it’s only certain doctors that do it, like there’s only certain doctors that do the shot. (Age 18) | Never got IUD; used DMPA. |

| Eligibility requirements | [M]y doctor don’t do it… [He said] that hospital doesn’t do it because they’re a Catholic hospital… and his clinic doesn’t do it because they’re affiliated with the hospital. (Age 17) | Never got IUD; used DMPA. |

| They said I couldn’t get the IUD because I had… I think chlamydia? And gonorrhea. And they said I couldn’t get it because I had to be clean for a whole year. (Age 16) | Never got IUD; used condoms and had repeat pregnancy. | |

| The people at the hospital… say you have to be 18 or have parent consent. (Age 17) | Used DMPA until IUD at 5 months postpartum; had IUD removed. |

DMPA=depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; IUD=Intrauterine device; OCPs=oral contraceptive pills.

Table 3.

Facilitators of IUD Uptake

| Facilitator | Participant Quotationsa |

|---|---|

| Strong provider recommendation | My doctor came and told me like, look girl, I don’t want you back in this hospital no more [laughs]. So I rather prefer you the IUD. And I’m like you right, I don’t want to be back in this hospital no more either. (Age 16) The doctor asked me what I use for birth control and I said nothing and I said that I was not going to have sex no more and she said yeah effing right…I had thought IUD and she said that it was the perfect choice…and I said alright. (Age 16) |

| Planning for IUD during pregnancy | When [I was] pregnant…I found out about a 5-year IUD and that’s when I started wanting it. As soon as I went to [my next prenatal visit] they asked me what did I want and I told them and they ordered it then. (Age 18) … they had it ready for my six week check up…I was like six months pregnant, they had asked me…did I plan on using the birth control method and the doctor had ordered it for me. (Age 18) |

| Recommendations from friends and family | You don’t have to worry about forgetting to take a pill or … having an appointment to get a shot or anything like that … I talked to people who had [IUDs]. (Age 17) Our sister was using it and she said like, it work or whatever so she had came, that’s why I got it. (Age 18) |

| Reproductive autonomy/partner support | ‘Cause he want to have a baby, another one, at least three, and me… no. But it don’t matter, it’s me, it’s my body…that’s my decision. (Age 16) He was the person who basically talked me into getting birth control…I talked to him about the IUD and he agreed, so, it was like, I guess, he was all for it. I was all for it, so, we both just saw eye to eye to the whole situation. (Age 17) |

| Struggling with adherence and side effects of other methods | [E]ver since I had him it’s like I have memory lapse…I don’t think the other methods would be good for me and this is something that I don’t have to worry about. So with the IUD I can just insert it and then I can go about my life. (Age 17) I missed my shot in February because I didn’t go to the doctor, I forgot I had an appointment and I didn’t go…and then I got on the IUD. (Age 17) |

IUD=Intrauterine device.

All quotations are from participants who successfully obtained an IUD during the 12-month follow-up.

Service-level obstacles

For many, the health care system posed obstacles to IUD uptake (Table 1). Barriers included lack of insurance coverage, difficulty scheduling appointments, limited clinic hours, referral requirements, long wait times, clinic closings, and lack of provider training. One participant lacked Medicaid coverage at her 6-week postpartum visit and used condoms instead; she experienced a repeat pregnancy. Several participants struggled with scheduling and attending appointments, often related to juggling multiple responsibilities as new parents. Despite being dissatisfied with DMPA side effects, two participants remained on the method because their providers were not trained to insert IUDs.

Participants were informed of eligibility requirements that precluded them from obtaining an IUD. One was incorrectly told by a provider that she had to be 18 years old or have parental consent. Another was denied an IUD because she had a sexually transmitted infection at her 6-week postpartum visit; she experienced a repeat pregnancy and obtained an abortion. When she requested an IUD post-abortion she was told that she “had to leave with the birth control shot (DMPA).”

Fears and concerns

Participants voiced multiple concerns about IUD-related side effects, risks, and procedures (Table 2). Family members and friends were very influential, with older family members being particularly persuasive. Their comments centered on infection, infertility, hair loss, and the insertion process.

Table 2.

Fears and concerns about IUDs

| Fear | Participant Quotations | Participant Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Uterine perforation | ‘Cause [my doctor] said it was gonna rip. I don’t want nothing to rip inside of me. So I got scared but I’m still thinking about getting it but, that scared me. (Age 18) | Never got IUD; used condoms and withdrawal. |

| [My grandmother] had the 5 year one and they implanted it when they did it. It went up to her stomach, so. She had had a C-section and they had to go back in and take it out. (Age 16) | Got IUD 4 months postpartum. | |

| Expulsion | Well they gave me like a packet…and I read the side effects and I was like ohhh… I was like I don’t know if I want to get this. It can fall out and get all these infections. (Age 16) | Never got IUD; switched between multiple methods. |

| Infertility | It can scar your ovaries and then you can’t get pregnant later on in life. But [the hospital staff] said it’s like a low percentage. (Age 16) | Got IUD 5.5 months postpartum. |

| Um, my stepmother she had her sister, she wasn’t able to have kids… And the doctor was saying … you know it’s different now but you know if something happen like that, you know, I don’t even want to try it. I… changed my mind. (Age 15) | Never got IUD; used DMPA. | |

| Infection | [My mom] told me that she had the IUD before and I shouldn’t get it because she got an infection from it… and she was like don’t get that …. And I was like okay. (Age 16) | Got IUD 5.5 months postpartum. |

| Yea, ‘cause my mom said it’s bad, everyone she knew was on there they had to get a hysterectomy… ‘cause it set up infection in your cervix. (Age 18) | Got IUD 6.5 months postpartum. | |

| Side effects | [My cousin] she don’t got no hair around the sides or the front of her head to like right here, so I’m like oh no, I don’t want to look like that [laugh]. (Age 17) | Never got IUD; used DMPA. |

| Insertion | Um, the fact that it’s like a mini-surgery. And they have to insert it into my cervix and that’s not the most comfortable thing. (Age 16) | Never got IUD; used condoms and had repeat pregnancy. |

| I don’t know what they gonna do they might stick me with something and I’m scared of needles and stuff like that. (Age 17) | Never got IUD; used condoms. |

DMPA=depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; IUD=Intrauterine device.

“Because, my mom was telling me how they put it in and everything… she worked there before and it was really rough.” (Age 17)

Another participant initially became interested in the IUD after hearing positive things from her sister (“she like it, like she was telling me about it, like she hadn’t bled for so long and like it’s, it’s cool.”), but eventually continued using DMPA after hearing about side effects that her cousin attributed to the IUD.

Some participants echoed provider warnings about future fertility and were frightened by the possibility of rare complications found in the packet insert. Others feared the IUD insertion process, likening it to other painful procedures that they had experienced. Additional concerns included having a foreign object inside of one’s body (“something inside [me] that doesn’t belong for 5 years”) and the string check requirement (“I don’t think I could do that. Like go up there, like every...[period].”).

Although the majority of participants either received active support or ambivalence from their partners about choosing the IUD, some faced strong opposition due to their partner’s attitude toward future childbearing and concerns about the device. Nearly all of the participants who reported partner opposition were unsuccessful in obtaining the device. Participants who believed their partners wanted another child sooner than 5 years or disliked the idea of a long-acting method grew ambivalent about the IUD.

He say he want another baby. But I’m, I’m not ready. I don’t want one… Like he got mad at me because I wanted to get on the 5 year thing. (Age 18)

Another participant who failed to get her IUD reported that her partner “don’t want anything inside of me for 5 years” and “strongly disagree[d] with the IUD.” She added:

… he didn’t want me to get it… my doctor said [my boyfriend is] scared of the thing if we was to have sex, something inside me for 5 years. (Age 18)

Shifting birth control preferences

Some participants decided against the IUD, ultimately determining that other contraceptive methods would work better for them. At times, the contraceptive gap between delivery and insertion led to a change in method choice. One participant opted for DMPA despite having ordered an IUD during pregnancy:

Just because they was offering it to me when I was leaving the hospital, and I just wanted to be, you know, safe, after it. (Age 18)

Other participants ultimately chose a method other than the IUD because their perceptions of the device’s efficacy changed upon reading educational materials and/or talking to other people, including physicians, following their delivery.

Yeah IUD, but they was like, once they put it in you, sometimes it comes out or something like that I was like, uh, I want a steady method. So I just started taking the pill. (Age 17)

A few participants expressed mistrust of all contraceptives, including the IUD, and opted for abstinence instead. This concern was particularly noted among participants who perceived themselves to be especially fertile. One participant recalled a conversation with her doctor:

I mean, I’m gonna get pregnant if I have sex. That’s what I tell myself, so. I just said, I’m just gonna stop all together. I have to. It’s gonna be hard, but, yeah. I got pregnant with my son on the pill. (Age 16)

However, at subsequent interviews she described an inability to remain abstinent, missed her DMPA appointments, and experienced a repeat pregnancy.

Facilitators of IUD Uptake

Among the eight participants who received the IUD by the end of the postpartum year, emergent themes reflected influence from providers, family members, and partners as well as participants’ own experiences with birth control (Table 3). While all participants reported learning about the IUD from a variety of sources including advertisements, friends and family, those who were successful in obtaining the device often reported that their doctor recommended – and even insisted on – the IUD. Three of the four participants who successfully obtained an IUD at their six week postpartum visit solidified their IUD decision during a prenatal visit with their doctor, who made sure the IUD was in stock for their postpartum check-up. Most of the participants who were successful in obtaining an IUD also had friends or relatives (predominantly mothers) who were supportive of the method. They also reported limited partner influence regarding their IUD decision, using phrases like “my body” or “my decision” in their responses. One participant, however, had a partner who was very supportive of the IUD and even initiated the conversation about postpartum birth control. Lastly, struggling with adherence and the side effect profile of other postpartum methods, in particular oral contraceptive pills, prompted some participants to choose the IUD.

COMMENT

This qualitative research provides new insights as to why adolescents at high risk of rapid repeat pregnancy who desire the IUD may or may not initiate the method. Repeated longitudinal interviews enabled us to determine time to insertion, adolescent views on why insertion did not occur, and the contraceptive outcomes of nonuse. Here, we found that 40% of requesters ultimately received an IUD. The three rapid repeat pregnancies were associated with non-use or irregular use of hormonal contraception. Successful IUD users indicated some facilitators; however, barriers were dominant among participant responses.

In another study of barriers to IUD use among postpartum women, including adolescents, a significant portion (35%) of women did not return for their scheduled postpartum visit and IUD insertion.19 Our study provides insight into missed visits, as participants juggled medical appointments among many other responsibilities, including parenting and school attendance. Insurance status may also preclude IUD uptake; despite Medicaid coverage of IUDs in most states, postpartum insurance coverage is more restricted than insurance during pregnancy and may end altogether by 8–10 weeks postpartum.

Our study notes that healthcare providers strongly influence IUD decision-making, sometimes preventing and at other times facilitating device uptake. Clinician-related barriers and facilitators are important as these are potentially modifiable. Other studies have demonstrated provider reluctance to use certain contraceptive methods among urban adolescents at risk of sexually transmitted infections.24 A recent survey among adolescents and young women with no history of IUD use demonstrated that provider counseling was associated with desire to use an IUD.25

Fears and concerns about perforation, insertion and infertility have also been found in studies of non-postpartum women.26 Studies of pregnant adolescents show a lack of knowledge of the safety and efficacy of the IUD compared to other methods.27 The significance of fears and misconceptions should not be underestimated, as they prompted many of our participants to choose less effective methods. Our findings suggest that discussing contraception with teens may not be enough. Family members, peers, and even patient education materials can cause youth to focus on rare, serious side effects. Attempts by male partners to control a woman’s fertility through coercion and/or violence have been well-documented in the literature.28 Our study provides insight to this phenomenon that is specific to adolescents and IUD use.

Our study revealed several facilitators to IUD use; in particular it shows how peers, partners and family members can facilitate IUD adoption. In an older prospective study of adolescent Norplant users, almost half of the participants reported that their mothers significantly influenced their decision to initiate the method.29 While the literature on condom negotiation among adolescent dyads is robust, there is a scarcity of published data regarding partner influence on hormonal birth control use, especially long-acting reversible contraceptives. However, one recent survey reveals perceived partner support to be an important predictor in consistent hormonal method use among adolescent girls.30

Because our study involved in-depth, qualitative interviews with a small sample of adolescents, it is hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory in nature. A larger quantitative study is needed to better understand the frequency of unfulfilled IUD requests. Our findings, based on a population of urban African American postpartum adolescents, may provide insight for other adolescent populations but further research is needed. By using a semi-structured interview guide that allowed for unscripted follow-up questions, the wording of questions varied between visits and across participants. Similarly, participant responses varied in amount of detail they provided regarding contraception.

Our study has a number of implications for clinical practice and future research. There is a clear need for additional training and education among clinicians as some may adhere to incorrect eligibility requirements (e.g. current STI infection, age), lack experience with IUD insertion, and be unaware of the benefits of IUDs for adolescents. Similarly, providers should conduct more thorough counseling and education on the safety and health benefits of the IUD with their adolescent patients. Specific areas for counseling might include the insertion procedure, pain control, string checks, and the remoteness of complication risks. Our study also suggests that in some instances partners may benefit from being included in the counseling process. Similarly, educational campaigns and interventions targeting postpartum adolescents’ network of influential people (e.g., family members, partners, and peers) may be needed to shift general attitudes and knowledge of IUDs. Future research should identify the most effective messages and best channels to deliver clear and balanced information about the IUD.

Our study also suggests that interval placement of the IUD (i.e., during or after the 6-week postpartum visit) may pose logistic and financial barriers for adolescent mothers. Post-placental insertion at the time of cesarean or vaginal delivery is being studied31, 32 and might benefit adolescent mothers. For now, providers should remove unnecessary barriers to interval IUD insertions and improve coordination of reproductive care for adolescent mothers. Such approaches might include: ordering the device in advance of the postpartum visit, educating adolescents on how to maintain their public insurance, removing unnecessary documentation and eligibility requirements, and expanding hours to evening or weekends. Long-acting, reversible methods of contraception have shown to be effective in preventing repeat pregnancy for adolescent mothers. While some adolescents may change their minds about choice of contraceptive method, here we demonstrate the role – both positive and negative – that health care providers and the health care system have in enabling youth to access their desired contraceptive method.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant #5K23-HD042614-02from The National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Child Health and Development.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.World Development Indicators. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacoby M, Gorenflo D, Black E, Wunderlich C, Eyler AE. Rapid repeat pregnancy and experiences of interpersonal violence among low-income adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 1999;16:318–21. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meade CS, Ickovics JR. Systematic review of sexual risk among pregnant and mothering teens in the USA: pregnancy as an opportunity for integrated prevention of STD and repeat pregnancy. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:661–78. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raneri LG, Wiemann CM. Social ecological predictors of repeat adolescent pregnancy. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2007;39:39–47. doi: 10.1363/3903907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens-Simon C, Kelly L, Kulick R. A village would be nice but.. it takes a long-acting contraceptive to prevent repeat adolescent pregnancies. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:60–5. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00316-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schelar E, Franzetta K, Manlove J. Repeat Teen Childbearing: Differences Across States and by Race and Ethnicity. Washington, DC: Child Trends; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Healthy People 2020 Topics and Objectives: Family Planning. [cited 2011 January 31, 2011]; Available from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicid=13.

- 8.Rubin DM, O’Reilly ALR, Luan X, Dai D, Localio AR, Christian CW. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010. Nov 1, Variation in Pregnancy Outcomes Following Statewide Implementation of a Prenatal Home Visitation Program. archpediatrics.2010.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnet B, Liu J, DeVoe M, Duggan AK, Gold MA, Pecukonis E. Motivational intervention to reduce rapid subsequent births to adolescent mothers: a community-based randomized trial. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:436–45. doi: 10.1370/afm.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elster AB, Lamb M, Tavare J, Ralston C. The Medical and Psychocial Impact of Comprehensive Care on Adolescent Pregnancy and Parenthood. JAMA. 1987;258:1187–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polit DF. Effects of a comprehensive program for teenage parents: five years after project redirection. Fam Plann Perspect. 1989;21:164, 9, 87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevens-Simon C, Dolgan JI, Kelly L, Singer D. The effect of monetary incentives and peer support groups on repeat adolescent pregnancies. A randomized trial of the Dollar-a-Day Program. JAMA. 1997;277:977–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polaneczky M, Slap G, Forke C, Rappaport A, Sondheimer S. The use of levonorgestrel implants (Norplant) for contraception in adolescent mothers. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1201–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411033311806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thurman AR, Hammond N, Brown HE, Roddy ME. Preventing repeat teen pregnancy: postpartum depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, oral contraceptive pills, or the patch? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2007;20:61–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Templeman CL, Cook V, Goldsmith LJ, Powell J, Hertweck SP. Postpartum contraceptive use among adolescent mothers. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:770–6. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00787-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis L, Doherty D, Hickey M, Skinner R. Predictors of sexual intercourse and rapid-repeat pregnancy among teenage mothers: an Australian prospective longitudinal study. MJA. 2010;193:338–42. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 392. Intrauterine device and adolescents. Obstet Gynecol. 2007 December;110:1493–5. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000291575.93944.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trussell J, Wynn LL. Reducing unintended pregnancy in the United States. Contraception. 2008;77:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogburn JA, Espey E, Stonehocker J. Barriers to intrauterine device insertion in postpartum women. Contraception. 2005;72:426–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harper CC, Blum M, de Bocanegra HT, et al. Challenges in translating evidence to practice: the provision of intrauterine contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1359–69. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318173fd83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanwood NL, Garrett JM, Konrad TR. Obstetrician-gynecologists and the intrauterine device: a survey of attitudes and practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:275–80. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01726-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilliam ML, Hernandez M. Providing contraceptive care to low-income, African American teens: the experience of urban community health centers. J Community Health. 2007;32:231–44. doi: 10.1007/s10900-007-9045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleming KL, Sokoloff A, Raine TR. Attitudes and beliefs about the intrauterine device among teenagers and young women. Contraception. 2010;82:178–82. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asker C, Stokes-Lampard H, Beavan J, Wilson S. What is it about intrauterine devices that women find unacceptable? Factors that make women non-users: a qualitative study. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2006;32:89–94. doi: 10.1783/147118906776276170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanwood NL, Bradley KA. Young pregnant women’s knowledge of modern intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1417–22. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000245447.56585.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller E, Decker MR, McCauley HL, et al. Pregnancy coercion, intimate partner violence, and unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2010;81:316–22. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rickert VI, Hendon AE, Davis P, Kozlowski KJ. Maternal influence on the decision to adopt Norplant. J Adolesc Health. 1995;16:354–9. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(94)00102-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kenyon DB, Sieving RE, Jerstad SJ, Pettingell SL, Skay CL. Individual, interpersonal, and relationship factors predicting hormonal and condom use consistency among adolescent girls. J Pediatr Health Care. 2010;24:241–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grimes DA, Lopez LM, Schulz KF, Van Vliet HA, Stanwood NL. Immediate post-partum insertion of intrauterine devices. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(5):CD003036. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003036.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen BA, Reeves MF, Hayes JL, Hohmann HL, Perriera LK, Creinin MD. Postplacental or delayed insertion of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device after vaginal delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1079–87. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f73fac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]