Abstract

Despite its relative infrequency, pregnancy is perceived by parents in rural Malawi as a leading cause of school dropout among female students. This paper explores parents’ beliefs about adolescent sexual activity and schoolgirl pregnancy, and how these perceptions frame parents’ aspirations and expectations about girls’ schooling. In-depth interviews were collected in rural Malawi from 60 adults aged 25–50 who were the parent of at least one school-aged child. Four themes emerged from the data: how expectations about sexual activity frame parental expectations about schooling duration and dropout; the loss of parental control; the negative influence of classmates; and schools as unsafe environments. These concerns frame how parents consider a daughter’s schooling prospects and are active even for parents whose daughters are not sexually active or who are not yet old enough to have gone through puberty. Although all parents aspire for their children to attend secondary school, these perceptions of daughters’ relative risk weaken parents’ motivation to encourage daughters to remain in school.

Keywords: adolescent, pregnancy, parental attitudes, Malawi

Introduction

In 1994, Malawi became the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to eliminate primary school fees, improving access to schooling for all children, particularly girls and the rural poor. As more young women enter school and remain enrolled in school longer than previous cohorts were able to do, opportunities for social and family tension emerge. This paper uses in-depth interviews to explore the gendered concerns that parents in rural Malawi have for their daughters’ educational attainment. The sexual activity of schoolgirls emerges from these data as a topic of particular worry, framing parents’ expectations and understandings of girls’ continued schooling.

To a large extent, school is a protective environment for young people. Across sub-Saharan Africa, young people who are enrolled in school are significantly less likely to have started having sex than adolescents who are no longer enrolled in school, and those students who have begun sexual activity are significantly more likely to use a condom than non-students (National Research Council-Institute of Medicine 2005). However, there is also strong evidence that young women who begin sexual activity while they are enrolled in school are significantly more likely to subsequently drop out of school than young women who have never had sex (Biddlecom et al. 2008). It is difficult to attribute causality to this association, because school participation and the onset of sexual activity share common influences, such as prior school performance (Grant and Hallman 2008), gendered classroom environments (Mensch et al. 2001), and young people’s ambitions for the future (Johnson-Hanks 2006). Almost all research on this association between sexual activity and school dropout has focused on the role of adolescent agency in the decision to leave school; however, in most settings, parents and other relatives are also actively involved in decisions about schooling duration. Continued school enrolment is often dependent on financial support from family members in order to cover school-related expenses. Family members evaluate whether the benefits of continued schooling outweigh these expenses, as well as the social and material opportunity costs of a young persons’ labour and delayed marriage.

Continued school enrolment increases the age at marriage, both because students are expected to remain unmarried and because of the effect of greater education on women’s economic lives and lifestyle expectations. However, this is not a neutral or universally desired outcome, as education and the prospect of social mobility complicate traditional family relationships (Stambach 2000), particularly as schooling creates a social space in which children are less subject to parental control. Delayed marriage increases the period of time when young women are exposed to the possibility of premarital sex, which becomes problematic when sexual activity is separated from the marriage process and raises the possibility of non-marital childbearing (Meekers 1992; 1994). Sexually active female students embody these risks, which not only challenge traditional forms of family organisation but are also perceived as endangering the family’s investment in education.

Education and sexual activity in rural Malawi

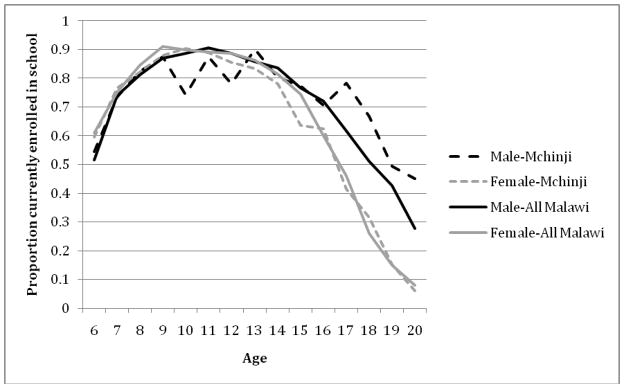

The tensions created by the expansion of female school enrolment into ages at which sexual activity is likely to happen are particularly relevant for Malawi. In 1994, the government of Malawi eliminated all school fees at the primary level, enabling free education for all students through the end of standard eight. However, families are still responsible for all non-tuition school expenses, including uniforms, exercise books and any other school supplies. Although minimal, the cost of these supplies strain most household budgets, given that almost 75 percent of the population in Malawi subsists on less than US$1.25 per day (United Nations Development Programme 2010). By 2004, almost all children had had some minimum level of schooling and the gender gap in primary school completion had closed in most regions of the country (National Statistics Office-Macro 2004). Figure 1 uses data from Malawi Longitudinal Survey of Families and Households (MLSFH) to show the percent of children enrolled in school, by age and sex, in Mchinji, Malawi, the setting of this study, relative to the age and sex pattern of school enrolment for the country as a whole (Malawi Longitudinal Survey of Families and Households 2009; National Statistics Office Macro 2004). There is no difference in the enrolment of boys and girls until after age 14, when girls leave school faster than boys. Grade repetition is very high, particularly for boys, both at lower grades and in standard eight, the last year of primary school, which many students repeat in order to improve their scores on the Primary School Leaving Exam and raise their chances of placement into a government secondary school. Beginning at age 15, boys have a higher mean grades completed by age relative to girls, with the gap widening over time (National Statistics Office - Macro 2004). Gender gaps emerge in the transition to secondary school, where tuition fees range from 30 to 200 US dollars, such that by age 20 twice as many males as females have entered secondary school (MLSFH 2009).

Figure 1.

Current school enrollment by sex, age 6–20

Source: Mchinji: Malawi Longitudinal Survey of Families and Households, 2006 (MLSFH 2009)

All Malawi: Demographic and Health Survey, 2004 (National Statistics Office -Macro 2004)

At the same time that girls’ schooling was expanding, there was no comparable decline in adolescent sexual activity or childbearing. Given the increased level of female educational attainment, it is likely that an increased percentage of young women have had their first sexual experience while still enrolled in school. Evidence from rural Malawi support the idea that these conflicts are not new developments; in the past it was not uncommon for girls to be withdrawn from school at the onset of menses (Helitzer-Allen 1994, cited in Kalipeni 1997), and some have speculated that parents pre-emptively remove daughters from school in order to more closely control their daughters’ sexual behaviour (National Research Council 1993).

Schoolgirl pregnancy is the realization of these fears. This combination of early school leaving and non-marital childbearing may disrupt the economic and marital aspirations of families and the young people themselves, impacting reputations and constraining future opportunities. However, data suggest that schoolgirl pregnancy plays a smaller role in determining girls’ educational trajectories than popular perceptions assert. In Malawi, the majority of childbearing before age 18 is marital childbearing, and schoolgirl pregnancy remains a relatively rare event. Data from the 2006 Malawi Longitudinal Survey of Families and Households (MLSFH) indicate that among women who were still enrolled in school at age 14, 4.5 percent of 15–19 year olds and 12.4 percent of 20–24 year olds became pregnant before they left school (author’s calculations). The 2008 MLSFH asked parents why their children had left school and found that more than half of 20–24 year female children were reported to have left school because they were “ready for marriage/sexually active,” compared to less than 10 percent who left school because of pregnancy(author’s calculations). These numbers are comparable to those in a recent study of five francophone African countries, which found that schoolgirl pregnancy only accounted for five to ten percent of all female school dropouts, and that young women were significantly more likely to leave school for marriage than for pregnancy (Lloyd and Mensch 2008). Nonetheless, schoolgirl pregnancy continues to be a focal point for parental and popular concern (Munthali et al. 2006).

Evidence from the early 1990s suggests that marriage has always been a prevalent cause for dropout among female adolescents in Malawi, although at lower levels than found in the MLSFH (Davison 1993). The same study noted parents’ concerns that continued schooling might limit girls’ matrimonial chances and that school subjects were not seen as relevant for the skills a young woman needed for married life. Although schoolgirl sexual activity may be part of the courtship process leading to marriage (Clark, Poulin and Kohler 2009), such relationships often occur without parental knowledge, creating a space for young women to exercise greater agency in their marital and sexual choices than might otherwise be the case.

This paper explores the intersection between parents’ aspirations for their children’s educational attainment and their discourse about how their daughters’ real and perceived sexual activity interferes with these goals. Prior analyses of the relationship between educational attainment and adolescent sexual activity have neglected the role that parents play in determining their daughters’ continued school enrolment. By describing the range of attitudes and concerns expressed by parents in in-depth interviews, this paper will cast light on how their interests shape decisions around school enrolment. I will explore the most common factor that parents describe as contributing to girls’ school dropout: adolescent sexual activity. I argue that parents’ perceptions about female sexual activity and the risk of pregnancy frame parents’ expectations for their daughters’ schooling trajectories and guide decisions about whether to encourage continued school enrolment. Not only do parents overestimate the prevalence of schoolgirl pregnancy as a cause of girls’ school leaving, but they also express a highly gendered perception of girls —but not boys— as unable to balance both a romantic interest and a focus on school. Parents frame their expectations for their children’s futures around these concerns and appear to revise their assessment of a child’s possible success or failure in relation to their perception of a child’s behaviour.

Data

This paper focuses on in-depth interviews collected in rural Malawi during the summer of 2006. The sample consists of 39 women and 21 men aged 25–50 who were the parent of at least one school-aged child (Table 1). The respondents were randomly sampled from the list of respondents to the Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project (MDICP), a longitudinal survey of the role of social interactions in HIV/AIDS attitudes, perceptions and risk behaviours. The MDICP has followed approximately 1,500 women and their spouses since 1998. Participants in the qualitative study were approached after the 2006 survey round was completed and were invited to take part in a one-time study about their children’s education. The female respondents were, on average, three and a half years younger than the male respondents. The average female respondent had 4.3 surviving children at the time of the interview. In comparison, male respondents had 5.5 living children. All interviews were collected in Mchinji district, located in the central region of Malawi. This sub-sample of the MDICP is predominantly Chewa. Although the Chewa are a matrilineal ethnic group, migration patterns and economic shifts towards cash cropping in Mchinji have undermined traditional inheritance and residence patterns and led to irregular enforcement of these norms (Phiri 1983; Takane 2009).

Table 1.

Qualitative sample characteristics, by sex of respondent, Malawi, 2006

| Sample Charateristics | Females (N=39) | Males (N=21) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 36.9 | 40.5 |

| Completed grades of school (mean) | 3.3 | 4.0 |

| Fertility | ||

| Children ever born (mean) | 5.7 | 6.8 |

| Living children (mean) | 4.3 | 5.5 |

| Children aged 6–18 (mean) | 2.6 | 3.4 |

Source: Malawi Longitudinal Survey of Families and Households, 2006 (MLSFH 2009)

All interviews were conducted in Chichewa, the prevalent language in this region. Each interview lasted approximately 40 minutes. All interviewers followed a common interview guide, covering topics that included: a complete education history for each of the respondent’s children, the anticipated returns on education for their children, their aspirations for each child’s educational attainment, and their perceptions of schooling patterns in their community. Other than these questions, interviewers were not given more specific interview guidelines but were encouraged to use a conversational tone and to allow the respondents to speak at length about their experiences and opinions.

Interviews were simultaneously transcribed and translated into English by the interviewers within 24 hours of the time of the interview, allowing the author to seek clarifications and advise revisions to the interview protocol as issues developed. The majority of changes focused on rephrasing questions that respondents had difficulty understanding and improving the probing techniques used by the interviewers. The transcripts were read closely by the author and coded, first with reference to the general themes covered by the interview guide described above. During the second coding, responses within each topic were classified into sub-categories. A large proportion of the responses referenced in this paper were provided following an open-ended question given to all respondents that asked whether the parent had any worries about their children. Relevant themes were also associated with questions that asked parents to comment on schooling patterns in their community, and also about their aspirations for their children’s schooling. Respondents were not asked directly about youth sexual activity or schoolgirl pregnancy; these topics were spontaneously mentioned by 38 of the 60 respondents. The quotations presented here were selected to represent key themes that characterise viewpoints that were shared by these respondents.

Results

This paper examines the range of ways that parents expressed concern for how sexual activity affects female schooling outcomes. Four themes emerged from the data: how expectations about sexual activity frame parental expectations about schooling duration and dropout; the loss of parental control; the negative influence of classmates; and schools as unsafe environments.

Framing expectations

As described earlier, schoolgirl pregnancy remains relatively infrequent in Malawi. Nonetheless, it looms large in the background of my interviews. Although only five of the 60 respondents had a child who left school because of pregnancy, parents as a group fear that once their young daughters reach puberty, they will become sexually active and get pregnant:

I: Do you have any other child who is still in school?

R: There’s a girl, an adolescent, she has just passed through puberty this year, so she is enrolled in school, she is doing grade six.

I: How far do you want that one to go with her school?

R: I can say that one should go further with her schooling, but it’s like, it’s the fate of these girls…they are just conceiving. Mmm, they are just conceiving, so even if we say they should go further, it’s impossible…Even if you advise them and say don’t play with boys…you’ll see that it is what? That the girls who will leave school are just conceiving. (Margret, female, 40 years old, 8 children)

Many of the respondents cited schoolgirl pregnancy as a leading reason why girls in their community drop out of school early, even though the event is relatively infrequent. Margret hopes that her daughter will be able to go far in school but is afraid that a pregnancy will derail her daughter’s educational attainment, as she observes that it has for other girls in her community. Although her daughter has only just reached menarche, Margret almost seems resigned that a pregnancy will keep her daughter from achieving her educational goals. This perceived high risk of pregnancy frames parents’ expectations for their daughters’ schooling trajectories and guides decisions about whether to encourage continued school enrolment:

I: So why did she drop out from school?

R: We tried to encourage her, but she was refusing, so her mother said, ah, no, do not force her, she can be impregnated…The worry has been about my daughters, I thought that they will be impregnated before formal marriages or contracting HIV/AIDS (Cosmas, male, 56 years old, 8 children).

In this case, Cosmas acknowledges that his daughter was a reluctant student. Whereas he wanted to encourage her to continue with her schooling, his wife argued that they should allow their daughter to drop out of school. His wife suspected that their daughter was distracted by a sexual relationship that might lead to a pregnancy that would force their daughter to drop out of school at some point in the future. Rather than continue paying for their daughter’s school expenses in the interim period until she “inevitably” would become pregnant, Cosmas and his wife decided to save the money and allow her to leave school. However, the second part of the quotation reveals a deeper fear: that a poorly-timed pregnancy would disrupt his daughters’ marriage prospects.

Most of [the girls], before finishing school, are found pregnant and stay at the household of their parents, so things are spoiled. (Liness, 35 years old, 8 children).

Lines stakes this concern one step further, worried that schoolgirl pregnancy “spoils” marriage process. Although concerns about marriage were only mentioned by a handful of respondents, these references suggest concerns about marriage may underlie some of the worries about schoolgirl sexual activity.

Even amongst parents whose children are too young to be sexually active, the future risk of pregnancy already casts a shadow over girls’ education. The oldest daughters of Madalitso and Tiyamike are both only seven, yet both parents already spontaneously bring up concern about whether those daughters will become pregnant and be forced to leave school:

I: So you have said you want your children to reach form four, so do you think the same for your girl child?

R: Of course all of them…[But] what the problem is with girls, as of now we can depend on her, but if she will reach womanhood, aaah. At womanhood she has reached puberty, so there can be many problems according to boys, but if she is principled she can finish school, but if she coaxes boys, she can be impregnated, and then that can be the end of her schooling…

I: But she can return to school after delivery.

R: Provided she is good but …here in the village, they just say, aaah, we have failed …then they [the girls] drop school while a boy can just come and impregnate a girl then he goes off back to school. (Madalitso, male, 25 years old, 3 children)

I: So what else are you worried about?

R: That maybe if my child will grow up, maybe she will not listen at school and will be pregnant, then she can drop school and also because of poverty, maybe my children cannot go to school because of poverty at home. (Tiyamike, female, 28 years old, 3 children)

These parents aspire for their daughters to go as far in school as possible, but their goals are framed by the possibility of sexual activity and the risk of pregnancy. Both Madalitso and Tiyamike approach this as a behavioural choice their daughters will make in the future—to be “principled”, focused on school, and able to avoid sexual activity, or to not listen at school and instead “coax boys” into relationships that will curtail their schooling.

In this context, schoolgirl pregnancy serves as a distraction from the more probable risks of dropout due to the pressures of extreme poverty or a child’s lack of interest in school (Mpando 2003). Rather than focusing on their potential inability to cover the costs of school expenses or the low likelihood that their children will find future employment, parents choose to focus on their daughters’ sexual activity as endangering their schooling prospects. Although girls’ primary school performance is equal to, if not better than, that of boys in rural Malawi (Hewett et al. 2008), parents choose to focus on daughters’ risks instead of that of sons. The parents interviewed in this sample occasionally appraised the relative intelligence of their children and seemed to be just as likely to cite a daughter as the most promising student in the family. However, no clear association between girls’ academic performance and parental anxiety emerged from the data.

Loss of parental control

The first dimension of parents’ bias is related to their perception that girls fail to follow their counsel to avoid premarital sex. Responsibility for abstaining from sex is placed on daughters, who are deemed incapable of resisting sexual temptation:

I: Was Maria enrolled in school by you?

R: She was enrolled in school by her parents, then when she was in standard three her parents died. That’s when I had taken her. With me she finished standard five, but because her life is not my life, she liked boys, then I tried hard in this and that way to control her, but it did not work…the disagreement of the child and me was because of her love of boys, that’s what made her leave my hands while she was young. (Loveness, female, 40 years old, 1 child).

I: The way I see is that your children have not done very well as far as education is concerned. What do you think is the problem?

R: The problem has been that the children have not been listening to my advice. I tried to force them to school but they could not listen, so I just said okay, it is up to you…The girls have been confused by the boys who were proposing to them in school. (Cosmas, male, 56 years old, 8 children).

Parents focus on sexual activity as something that distracts girls’ attention from school. In some ways, this perspective is consistent with the literature that examines the endogeneity of adolescent sexual activity and schooling outcomes (NRC 1993). Other interviews with adolescents in rural Malawi found that young women who deferred sexual activity believed that sexual relationships might interfere with their ability to do well in school and thus jeopardize future employment opportunities, whereas young women who lacked the same aspirations may have been both less committed to remaining in school and less motivated to resist sexual proposals (Frye 2010; Poulin 2006). Likewise, in neighbouring Tanzania, Wight et al (2006) describe the longstanding expectation that school girls will abstain from sexual relationships so that their attention will not be diverted from their studies.

In the tales recounted above, Loveness and Cosmas do not reflect on how their daughters’ sexual relationships led to their school dropout; it is presented as an almost inevitable outcome for daughters who did not listen to their parents. The parents do not tell us whether their daughters’ academic performance suffered or how their interest in school declined because of the relationship. Instead, these parents lament that their daughters did not listen to their advice to remain abstinent. Rather than recognizing that girls’ sexual activity might have its roots in girls’ academic performance or classroom experiences (e.g. Mensch et al 2001; Grant and Hallman 2008), parents in this sample perceive their daughters’ sexual activity as being more closely related to not listening to parental advice—they seem to be mourning a loss of control over their daughters.

However, it is unclear whether this is a real or imagined loss of control; in the case of divorce, Kaler (2001) shows that older Malawians were just as likely to bemoan marriage as a deteriorating institution in the 1940s as in the 1990s, suggesting the strong role of invented tradition to deal with intergenerational discontent. Other studies from around East Africa have found that adult misperceptions of youth sexual activity reflected parents’ feelings of helplessness in the face of a changing sexual landscape shaped by the HIV/AIDS epidemic (Stewart 2000). Traditional cultural practices that provided information about sexual behaviour and values through formalized kinship relationships weakened and were partially replaced by public health and media-driven messages about sex (Stewart 2000; Parikh 2005). At the same time, young people reported that parents no longer provided relevant information and didn’t understand their children’s lives (Mmari, Michaelis and Kiro 2009; Remes et al. 2010). The expansion of school enrolment in Malawi has been a powerful force for intergenerational change, as many children surpass the educational attainment of their parents. The perceived loss of parental control described by respondents in this sample may reflect parents’ lack of familiarity with the lives of their children and apprehensions about the potential of schooling to create both future opportunities and spaces where children are subject to non-family influences.

Peer influence

Parents voice particular concerns about the influence of school friends, who may be wealthier than village friends. Girls are framed as being more vulnerable to sexual activity than boys, because they are seen both as unable to resist the temptation of sex and as more susceptible to peer pressure: they begin sexual activity in order to acquire the material goods possessed by their better-off friends. Within adolescent sexual relationships in Malawi, the exchange of money and gifts is normative. While girls perceive themselves as actively choosing a partner who will improve her life by providing her with lotions, new shoes, or even money (Poulin 2007), parents perceive these relationships as something that will spoil a daughter’s future:

You go to school…there you meet friends. We come from different households. Some are well to do, you see this morning your friend has put on this, this morning has put on that, so when you say, aaah, I may also be like this one, the end result is that a male person proposes to you, that means maybe he has given you a pregnancy, that’s all, you’ve failed school. You are going to sit down at home…that female has dropped out from school, but he…will still continue school. That’s the problem. (Eliza, female, 37 years old, 4 children).

I have worry because I have only given birth to girls so these days there are many things happening like admiring nice clothes…she can admire them, so I have worry that this one is moving with this friend wearing a nice cloth. What will be her thoughts, so I do worry much, that what should I do to help these children…maybe she can cope with her friends’ behaviour and these days are more dangerous with diseases, yah, there is worry. (Ruth, female, 29 years old, 2 children).

Parents worry that daughters who envy wealthier friends will enter sexual relationships in order to acquire the material goods that their friends possess. Like all of the other parents interviewed, Eliza and Ruth consider sexual relationships to be incompatible with continued school enrolment. Eliza frames her concerns around the prospect that such a sexual relationship would lead directly to pregnancy and, hence, to school dropout. At the same time, she notes that boys experience few negative consequences for impregnating a girl and their schooling is unlikely to be formally affected. In contrast, Ruth worries that if her daughters want nice things that she cannot afford, it will make them more vulnerable to sexually transmitted diseases, such as HIV.

Surprisingly, in these interviews with parents, the possibility of pregnancy was more threatening to their daughters than the risk of becoming infected with HIV. While parents more generally consider their own future health when making decisions about their children’s schooling (Grant 2008; de Lannoy 2005), they are less explicit about their children’s future health. To the extent that parents do invoke the chance that their children might become infected with HIV, it is presented as an alternative to education, rather than something that alters the benefits of education:

R: The health of my children, I really worry, especially on the side that I have already said that it worries when you see that you have advised children, then that child goes out and shall contract something out there and maybe the one your child is going out with is not a right person, then at that point the child has started double dealings. When the kid is at home she is like a normal person but when the kid goes out she is mixed up with other immoral behaviours, then the health of this person is unpredictable…the most important thing is that this child should be educated, she should not be in the group of beggars, this child cannot afford it…Now in the modern life you can be chatting with each other [i.e. in a relationship] and there are some words that one speaks that pressures the other, almost like stealing, maybe that kid can start another life of stealing, so that child will get lost. (Chifundo, female, 35 years old, 6 children).

Whereas theories of human capital focus on how the HIV epidemic might alter the perceived returns on schooling, Chifundo is more concerned with how the sexual relationships that may transmit infection will interfere with her daughter’s schooling. In this case, peer pressure to initiate sexual activity is presented as something that will “steal” her child’s future, by increasing the probability that her daughter will both become infected and drop out of school prematurely. But, fundamentally, the threat to educational attainment is not HIV infection but the participation in “immoral behaviours.”

R: It appears he is intelligent and when I see his writings, I hope it is going to help us… But I see that if the child in Form Two continues like the way he is doing then it will be helpful if he cannot indulge in immoral activities… Nowadays when children go to school especially in high school classes, form one, two, it’s not most of the time to finish because they like females…I just worry that maybe people will destroy my children… [I] tell them to stop this, today there is death through these ways, so if you want to see white hair like mine, you must care for yourself. (Steven, male, 61 years old, 10 children).

The ideal of premarital abstinence still dominates parental expectations, even though at least a third of young women do initiate premarital sexual relationships (National Statistics Office - Macro 2004; Biddlecom et al. 2008). Steven is one of the few parents to extend such concerns to a son in addition to daughters. His son is only two years away from completing secondary school, and Steven reflects that his son’s academic performance promises the possibility of finding paid employment and contributing to the family income. From his viewpoint, his son will achieve these goals, but only if he “cannot indulge in immoral activities.” For daughters, the threat that sexual activity might interfere with educational attainment is weighed from early in a girl’s childhood, whereas for sons this risk is only invoked when boys are on the cusp of completing school.

Schools as unsafe environments

Even when parents present themselves as encouraging their daughters’ schooling, they still frame girls as particularly vulnerable and unable to resist sexual advances. An extreme case is represented in the following excerpt:

I: You have said that you tried to make her stay longer in school, but why did you fail?

R: What happened is that she had a friend who had a sexual relationship with a teacher and that teacher had a friend who together influenced my daughter to be in a sexual relationship. So when I heard this, I reported to the head teacher but it was too late because my daughter had already had sex with that man, so she could not listen to me to continue with school…I explained to her that I could send her to my relatives in Lilongwe [to continue her education], but she refused…You know by this time she had already tasted it. So she could not listen to my advice…Mmh! Once a child has tasted sex, mmh! She likes it a lot. She just concentrates on the boy. (Gift, male, 50 years old, 8 children).

This father, a village chief, is interesting because he did not view his daughter’s sexual activity or its unfortunate circumstances as necessitating the end of her schooling career in and of itself: she could have accepted his offer to transfer her to a different school, away from the teacher who instigated her sexual relationship, but she refused and subsequently dropped out of school. Similar to Loveness and Cosmas, Gift does not discuss his daughter’s academic performance or her attachment to school, but contextualises her drop out in the frame of her sexual activity. He claims that she cannot concentrate on school after she “tasted sex”. This echoes the earlier comments, where parents believe that daughters are “confused” by the invitations of boys asking to be their boyfriend and have sex with them. However, Gift also recognises that the local school was an unsafe environment, where teachers harassed female students and initiated sexual relationships. The refusal of the head teacher to punish the teacher demonstrates that parents have legitimate reasons to worry about whether schools offered risk or protection.

Discussion

The expansion of female schooling following the 1994 education policy that removed primary school fees in Malawi opened up more opportunities for young women to become educated and seek wage employment that would permit them to contribute substantially to the family’s material well-being. However, school enrolment at older ages means that girls spend more time away from familial supervision in a mixed sex environment. Parents cite concerns that their daughters’ potential sexual activity and relationships will interfere with their ability to complete their education, because girls are perceived as less able to resist the temptations of sex and unable to focus on school if they are in a sexual relationship. Whereas the risk of HIV is present for both boys and girls, pregnancy is a threat unique to young women. The social danger of a poorly timed pregnancy may outweigh the benefits of further schooling, particularly when the prospects of secondary school completion are perceived to be uncertain or unlikely.

However, given how low the actual prevalence of schoolgirl pregnancy is, this still begs the question of why this issue seems to dominate parents’ stated concerns for their daughters’ educational attainment. Schoolgirl pregnancy may complicate a family’s response to non-marital childbearing by also transgressing the ideal of schoolgirl abstinence (Poulin 2006; Munthali et al. 2006). Because it is such an undesirable outcome, parents may be more likely to remember those young women in their community who were forced to leave school because of pregnancy than they are to recall the majority of girls who exit school without incident. Research on how people understand risk and estimate subjective probabilities has shown that individuals are more likely to remember the events that happen rather than the events that are avoided (Tversky 1974), and this might drive their preoccupation with their daughters’ sexual behaviour and its perceived educational consequences. Parental perceptions of schoolgirl pregnancy may constitute a sort of moral panic, disproportionate to the actual size of the problem. However, it is also possible that the low levels of schoolgirl pregnancy observed in rural Malawi are produced by the actions of parents who remove sexually active daughters from school before they become pregnant. Parental concern for their daughters’ sexual activity may be preventing pregnancies, although at the cost of women’s schooling attainment. Parents’ concern for how their daughters’ sexual activity might interfere with educational attainment may also belie a possible resource bias in favour of sons. The preoccupation with daughters’ sexual activity disproportionate to that of sons already displays a gendered concern within the household for behaviour control, but it might also reflect that parents have different expectations for the returns on schooling according to a child’s sex. In their discussion of the value of education, parents did not explicitly differentiate between their daughters and sons. If anything, they seemed to favour the child who showed the most academic promise and interest in school, regardless of sex. However, all of the parents interviewed in this study are extremely poor. Given that many parents showed little resistance when their children did drop out of school, it is possible that parents who are operating on such a thin margin of poverty might be looking for reasons to shift resources from one child to another or from education to other household expenses. The assumption that sexual activity impedes school success frames how parents will react when they are confronted with rumours or evidence of their children’s sexual behaviour. Although there is no real difference by sex in primary school completion rates today, parents seem poised to favour the education of sons over daughters.

A final interpretation might be that parents are using their daughters’ sexual activity and the threat of schoolgirl pregnancy to disguise the role that poverty plays in determining children’s schooling duration. However, this is the least likely of the explanations to make sense in rural Malawi. Poverty was the norm in the sample villages, rather than a deviation from a median wealth. Parents freely reported instances of children who were forced to leave secondary school because they could not afford the school fees and reflected that poverty might interfere with the educational aspirations that they had for younger children. If anything, sexual activity and schoolgirl pregnancy were more embarrassing explanations for school leaving, because to many parents these outcomes represented a loss of parental control over children’s behaviour.

To date, almost all analyses that consider the association between adolescent sexual activity and continued school enrolment have focused on the role of adolescent agency in decision-making. However, these interviews with parents demonstrate that the decision to leave school is a multi-actored process. If parents frame sexual activity as a school-ending behaviour for their daughters, this influences how daughters perceive their opportunities and choices during adolescence and early adulthood. These subtle cues of family support and encouragement to continue schooling, or the lack thereof, are likely to play an important role in both school continuation and the onset of sexual behaviour. Future studies of the relationship between sexual activity and educational attainment would benefit from a consideration of how behavioural choices and outcomes are framed within the expectations and resources of the family. While some recent research has begun to move in this direction (e.g. Sekiwunga and Whyte 2010), the majority of studies fail to integrate the perspectives of all actors.

References

- Biddlecom A, Gregory R, Lloyd C, Mensch B. Premarital sex and schooling transitions in four sub-Saharan African countries. Studies in Family Planning. 2008;39(4):337–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S, Poulin M, Kohler H-P. Marital aspirations, sexual behaviors and HIV/AIDS in rural Malawi. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2009;71(2):396–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00607.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison J. School attainment and gender: Attitudes of Kenyan and Malawian parents towards educating girls. International Journal of Educational Development. 1993;13(4):331–338. [Google Scholar]

- De Lannoy A. CSSR Working Paper No. 137. University of Capetown; 2005. “There is no other way out”: Educational decision-making in an era of AIDS: How do HIV-positive mothers value education? [Google Scholar]

- Frye M. Bright futures in Malawi’s new dawn: Educational aspirations as assertions of identity. Paper presented at Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America.2010. [Google Scholar]

- Grant MJ. Children’s school participation and HIV/AIDS in rural Malawi: The role of parental knowledge and perceptions. Demographic Research. 2008;19:article 45, 1603–1634. [Google Scholar]

- Grant M, Hallman K. Pregnancy-related school dropout and prior school performance in Kwa-Zulu/Natal, South Africa. Studies in Family Planning. 2008;39(4):369–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helitzer-Allen D. An investigation of community-based communication networks of adolescent girls in rural Malawi for HIV/STD prevention messages. Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hewett PC, Mensch BS, Lloyd CB, Chimombo J, Rankin J. Assessing the impact of primary school quality on adolescent educational outcomes. Paper presented at Comparative and International Education Society Annual Meeting; Charleston, South Carolina. March 23, 2009..2009. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Hanks J. Uncertain honor: Modern motherhood in an African crisis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kaler A. “Many divorces and many spinsters”: Marriage as an invented tradition in southern Malawi: 1946–1999. Journal of Family History. 2001;26(4):529–556. doi: 10.1177/036319900102600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalipeni E. Gender and regional differences in schooling between boys and girls in Malawi. East African Geographical Review. 1997;19(1):14–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd CB, Mensch BS. Marriage and childbearing as factors in dropping out from school: an analysis of DHS data from sub-Saharan Africa. Population Studies. 2008;62(1):1–13. doi: 10.1080/00324720701810840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Statistics Office - Macro International. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2004. Calverton, MD: Macro International; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mensch BS, Clark WH, Lloyd CB, Erulkar AS. Premarital sex, schoolgirl pregnancy, and school quality in rural Kenya. Studies in Family Planning. 2001;32(4):285–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meekers D. The process of marriage in African societies: A multiple indicator approach. Population and Development Review. 1992;18(1):61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Meekers D. Sexual initiation and premarital childbearing in sub-Saharan Africa. Population Studies. 1994;48(1):47–64. [Google Scholar]

- MLSFH. [Accessed on September 5, 2011.];Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health – Newsletter 2008/1: Summary of data collection 1998—2008. 2009 Available online at http://www.malawi.pop.upenn.edu.

- Mmari K, Michaelis A, Kiro K. Risk and protective factors for HIV among orphans and non-orphans in Tanzania. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2009;11(8):799–809. doi: 10.1080/13691050902919085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mpando LRS. 2002 Malawi Core Welfare Indicators Report. Lilongwe, Malawi: National Statistics Office; 2003. Education and literacy. [Google Scholar]

- Munthali AC, Moore AM, Konyani S, Zakeyo B. Occasional Report No. 23. New York: Alan Guttmacher Institute; 2006. Qualitative evidence of adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health experiences in selected districts of Malawi. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd Cynthia., editor. National Research Council-Institute of Medicine (NRC-IOM) Growing up global: The transition to adulthood in less developed countries. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bledsoe Carolyn, Hill Ken., editors. National Research Council (NRC) Adolescent fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Statistics Office – Macro International. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey. Calverton, MD: Macro International; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Parikh S. From auntie to disco: The bifurcation of risk and pleasure in sex education in Uganda. In: Adams V, Pigg SL, editors. Sex in development: Science, sexuality, and morality in a global perspective. Durham: Duke University Press; 2005. pp. 125–158. [Google Scholar]

- Phiri KM. Some changes in the matrilineal family system among the Chewa of Malawi since the nineteenth century. Journal of African History. 1983;24:257–274. [Google Scholar]

- Poulin MJ. Unpublished PhD thesis. Department of Sociology. Boston University; 2006. The sexual and social relations of youth in rural Malawi: strategies for AIDS prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Poulin MJ. Sex, money, and premarital partnerships in southern Malawi. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65:2383–2393. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remes P, Renju J, Nyalali K, Medard L, Kimaryo M, Changalucha J, Obasi A, Wight D. Dusty discos and dangerous desires: community perceptions of adolescent sexual and reproductive health risks and vulnerability and the potential role of parents in rural Mwanza, Tanzania. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2010;12(3):279–292. doi: 10.1080/13691050903395145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiwunga R, Whyte SR. Poor parenting: Teenagers’ views on adolescent pregnancies in eastern Uganda. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2010;13(4):113–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambach A. Lessons on Mount Kilamanjaro: Schooling, community, and gender in East Africa. New York: Routledge; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart K. Toward a historical perspective on sexuality in Uganda: The reproductive lifeline technique for grandmothers and their daughters. Africa Today. 2000;47(3):123–148. [Google Scholar]

- Takane T. Customary land tenure, inheritance rules, and smallholder farmers in Malawi. Journal of Southern African Studies. 2008;34(2):269–291. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A. Assessing uncertainty. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1974;36(2):148–159. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Program. Human Development Report. New York: United Nations; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wight D, Plummer ML, Mshana G, Wamoyi J, Shigongo ZS, Ross DA. Contradictory sexual norms and expectations for young people in rural Northern Tanzania. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62:987–997. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]