Abstract

We have shown that isoflurane application at the onset of reperfusion (postconditioning) reduces brain ischemic injury in rats. This study was designed to determine whether this protection involved activation of prosurvival protein kinases and maintenance of normal mitochondrial membrane permeability. Two-month old male rats were subjected to a 90-min middle cerebral arterial occlusion. They then were exposed or were not exposed to 2% isoflurane for 1 h. Ischemic penumbral cerebral cortex was harvested immediately and separated into the mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions. We showed that the mitochondrial nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide content in the ischemic penumbral cortex was significantly reduced, suggesting an increased mitochondrial membrane permeability. This increase was partly attenuated by isoflurane postconditioning. The mitochondrial adenosine diphosphate content in the penumbral cortex was reduced no matter whether the animals were postconditioned with isoflurane. The mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate concentration was not different among various experimental conditions. The phospho-Akt in the cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions of the ischemic penumbral cortex was higher than that in the control cortex. This increase trended to be higher in animals with isoflurane postconditioning. A similar change pattern was observed in the mitochondrial phospho-glycogen synthase kinase 3β, an Akt substrate that can regulate the mitochondrial membrane permeability. Isoflurane postconditioning reduced oxygen-glucose deprivation-induced injury of rat cortical neuronal cultures and increased phospho-Akt in these cells. The isoflurane postconditioning-induced protection in the neuronal cultures was decreased by the Akt inhibitor LY294002. These results suggest that isoflurane postconditioning effects may be mediated by Akt and involve reduced mitochondrial membrane permeability.

Keywords: Akt, glycogen synthase kinase 3β, isoflurane, neuroprotection, mitochondrial membrane permeability, postconditioning

Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of death and disability in the USA and world (Martin et al., 1999; Ingall, 2004). Currently, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) therapy is the only intervention approved by US Food and Drug Administration for clinical use to reduce ischemic brain injury. However, the very short time-window for tPA therapy to be neuroprotective limits the use of this therapy to less than 4% patients with ischemic stroke (Reeves et al., 2005; Fang et al., 2010). Thus, identification of neuroprotective strategies for possible clinical use is urgently needed. In addition, reestablishing blood circulation to ischemic brain tissues by tPA therapy may cause significant reperfusion injury to the tissues. Developing methods to reduce reperfusion injury obviously will improve the safety profile of tPA therapy.

A method identified in recent years that can reduce reperfusion injury is called postconditioning (Zhao et al., 2003). Postconditioning was used initially to describe a protective effect induced by manipulating the reperfusion process after ischemia (ischemic postconditioning) (Zhao et al., 2003). It has been shown that other methods, such as certain medications, also can induce a postconditioning effect. We and others have shown that volatile anesthetics including isoflurane induce a postconditioning effect in the brain (Lee et al., 2008; McMurtrey and Zuo, 2010; Zhou et al., 2010). However, very little is known about this anesthetic postconditioning-induced neuroprotection.

Ischemia and reperfusion significantly impair the mitochondrial functions and integrity. Mitochondrial injury after ischemia and reperfusion is a fundamental process that leads to cell injury and death (Lipton, 1999; Kroemer et al., 2007). For example, increased mitochondrial membrane permeability that results in release of substances from the mitochondria to the cytosol has been considered as a critical pathological process to induce cell death (Kroemer et al., 2007; Li et al., 2008). Thus, we hypothesize that isoflurane postconditioning reduces ischemia-reperfusion-induced increase of the mitochondrial membrane permeability. Since prosurvival protein kinases, such as protein kinase B/Akt and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β), can regulate the mitochondrial membrane permeability (Juhaszova et al., 2004; Kroemer et al., 2007), we also hypothesize that the activation of Akt is involved in isoflurane postconditioning-induced neuroprotection.

Materials and methods

The animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, United States. All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication No. 80-23) revised in 1996. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

Transient middle cerebral arterial occlusion (MCAO) and isoflurane postconditioning

Sprague-Dawley 2-month old male rats weighing 280 to 300 g were anesthetized with isoflurane, intubated and mechanically ventilated. Anesthesia was maintained with 2% isoflurane. Right MCAO was achieved by advancing a 3-0 monofilament nylon suture (Beijing Sunbio Biotech Co. Ltd., Beijing, China) with a rounded tip to the right internal carotid artery via the external carotid artery until slight resistance was felt. The common carotid artery was transiently occluded but was not ligated during the process. Isoflurane anesthesia was stopped immediately once the suture was in place. After recovery from anesthesia, rats were placed back into their cages with ad libitum access to food and water. Rats were re-anesthetized with isoflurane at 90 min after the onset of MCAO. The nylon suture was removed. The re-anesthesia time was about 1 min for each animal. The rats in the MCAO plus isoflurane postconditioning group were maintained under anesthesia with 2% isoflurane via an endotracheal tube for 60 min. During anesthesia for achieving MCAO and postconditioning period, temporalis muscle temperature was strictly maintained at 37 ± 0.2 °C by a warming blanket. The inhaled and exhaled gases were also monitored with a Datex infrared analyzer (Capnomac, Helsinki, Finland) to maintain normal end-tidal carbon dioxide concentrations.

Brain tissue sampling and the fractionation of cytosol and mitochondria

Rats were euthanized by 5% isoflurane and transcardially perfused with saline at 1 h after MCAO. The frontal cortex area 1 (Fr1) of the right cerebral hemisphere was removed. This brain region has decreased blood flow and is classified as a penumbral area after MCAO (Nagasawa and Kogure, 1989; Memezawa et al., 1992; Li et al., 2008). The cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions of the harvested brain tissues were prepared as previously described (Hirai et al., 2004; Li et al., 2008). Briefly, each brain tissue sample was placed in ice-cold buffer (200 mM mannitol and 80 mM HEPES-KOH at pH 7.4) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail and homogenized by 30 strokes of gentle pounding in a glass tissue grinder. Homogenates were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The resulted pellets were washed 3 times and suspended in the buffer as the mitochondrial fractions. Supernatants of the 8,000 × g centrifugation were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The resulted supernatants were cytosolic fractions.

Measurement of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) contents in the mitochondria

Isolated mitochondria were used to measure the mitochondrial NAD concentrations according to the manufacture’s protocol (EnzyChrom™ NAD+/NADH Assay Kit, catalog number: ECND-100; BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA). The mitochondrial content of ATP and ADP was measured according to the manufacture’s protocol (ADP/ATP Ratio Assay Kit, catalogue number: ab65313; Abcam, Cambridge, MA). The results were normalized to the corresponding mitochondrial protein concentrations. The NAD results of the rats subjected to MCAO or to MCAO plus isoflurane postconditioning were then normalized to the corresponding data of control rats. The ATP and ADP results were presented as arbitrary unit.

Western analysis

Proteins of 30 μg per lane of mitochondrial or cytosolic fractions were subjected to 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. After being incubated with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% non-fat milk and 0.1% Tween-20 for 1 h at room temperature, the membranes were probed overnight at 40C with various primary antibodies in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST). The primary antibodies used were the anti-Akt antibody (1:1000 dilution, catalog number: 9272; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), anti-phospho-S473-Akt antibody (1:1000 dilution, catalog number: 9271; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-GSK-3β antibody (1:1000 dilution, catalog number: 9315; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-phospho-S9-GSK-3β antibody (1:1000 dilution, catalog number: 9336, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) (1:1000 dilution, catalog number: 4866; Cell Signaling Technology) and anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibody (1:4000 dilution, catalog number: G9545; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). After being rinsed with PBST, the membranes were incubated with the corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature.

The protein bands were visualized with the enhanced chemiluminescence method using a Genomic and Proteomic Gel Documentation (Gel Doc) Systems from Syngene (Frederick, MD). The densities of Akt, phospho-Akt, GSK-3β and phospho-GSK-3β protein bands in the mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were normalized to those of VDAC or GAPDH, respectively, to control for errors in protein sample loading and transferring during Western analysis. VDAC is a mitochondrial protein (Li et al., 2008). GAPDH is expressed abundantly in the cytosol. The results from rats exposed to MCAO or MCAO plus isoflurane postconditioning were then normalized to the corresponding data of control rats on the same film to control for the errors caused by different exposure times of films.

Primary rat cortical neuronal culture

Primary rat cortical neuronal cultures were obtained from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA; Catalog number: A10840-01). The neurons were harvested from 18-day old embryos of the Fischer 344 rats. Neurons were plated at approximately 1.4 × 104 cells per well in 96-well plates. Neurons were cultured in Neurobasal medium (Catalog number: 21103-049, Invitrogen Life Technologies) supplemented with 200 mM Glutamax-1 (Catalog number: 35050, Invitrogen Life Technologies) and B-27 (Catalog number: 17504, Invitrogen Life Technologies). The cells were fed twice each week by replacing half of the culture medium with new medium that had the appropriate supplements as specified above, and were kept in a cell culture incubator with 95% air -5% CO2 at 37ºC.

Study groups of neuronal cultures

The neurons were divided into 5 groups: 1) control group; 2) oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) group; 3) OGD plus isoflurane postconditioning group; 4) LY 294002 treatment plus OGD group; 5) LY294002 treatment plus OGD plus isoflurane postconditioning group. The final LY294002 concentration in the culture medium was 10 μM and LY294002 was present for 1 h started immediately before the OGD application.

OGD and isoflurane postconditioning in the neuronal cultures

On the fifth day in culture in our laboratory, the neuronal features are well developed. The culture medium was removed and cells were washed with Neurobasal-A medium (Catalog number: 10888022, Invitrogen Life Technologies) that had no glucose, glutamine and B27. As we described previously (Kim et al., 2009), this Neurobasal-A medium was pregassed with 95% N2-5% CO2 for 20 min to get rid of oxygen in the solution. The neurons were placed into this pregassed medium and the culture plates were placed in a Billups-Rothenburg container. The container was flushed with 95% N2-5% CO2 for approximately 10 min until O2 levels in the outlet gases from the container were < 2%. The outlet gases were continuously monitored by a DatexTM infrared analyzer (Capnomac, Helsinki, Finland). The container was then sealed and the cells were kept in this condition for 1 h at 37ºC. At the end of this OGD period, the cells were re-exposed to room air. Glucose, glutamine and B27 were added to the incubation solution. This process simulates reperfusion. For the control group, the culture medium was replaced with fresh regular medium instead of Neurobasal-A medium. Isoflurane postconditioning was performed by exposing the cells to 2% isoflurane for 1 h immediately after the OGD in the Billups-Rothenburg container. This was achieved by flushing the container with 2% isoflurane in 95% air-5% CO2 for 10 min after glucose, glutamine and B27 were added to the medium. The isoflurane exposure duration and isoflurane concentration were decided based on our previous study (Zheng and Zuo, 2003; Lee et al., 2008).

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

At 1 h after the onset of simulated reperfusion or immediately after isoflurane post-treatment, the MMP of the primary cortical neuron cultures was measured using the JC-1 Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay Kit (Catalog number: 10009172; Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan) according to the manufacture’s protocol.

Quantification of phosphorylated Akt

Primary cortical neuronal cultures were used for quantification of phospho-Akt at 1 h after the end of OGD or immediately after isoflurane post-treatment. The Akt phosphorylated at S473 was measured using the Pierce AKT Colorimetric In-cell Elisa Kit (Catalog number: 62215; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacture’s protocol. The results were normalized by the corresponding cell numbers and then normalized to the mean value of the control neurons in the same culture plate.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release

Neuronal injury at 24 h after the onset of simulated reperfusion was quantified by measuring LDH release using the LDH Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (Catalog number: PT3947-1; Clontech, Mountain View, CA) according to the manufacture’s protocol. LDH release was calculated as a percentage of LDH released to the culture medium in the total LDH in the cells of each well. The LDH release in percentage was calculated using the following equation: LDH level in the incubation medium x 100/(intracellular LDH level + LDH level in the incubation medium).

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ± S.D. (n ≥ 4 for each experimental condition). Results were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls Method for post hoc analysis after the confirmation of normal distribution of the data or by one-way analysis of variance on ranks followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls Method for post hoc analysis if the data are not normally distributed. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

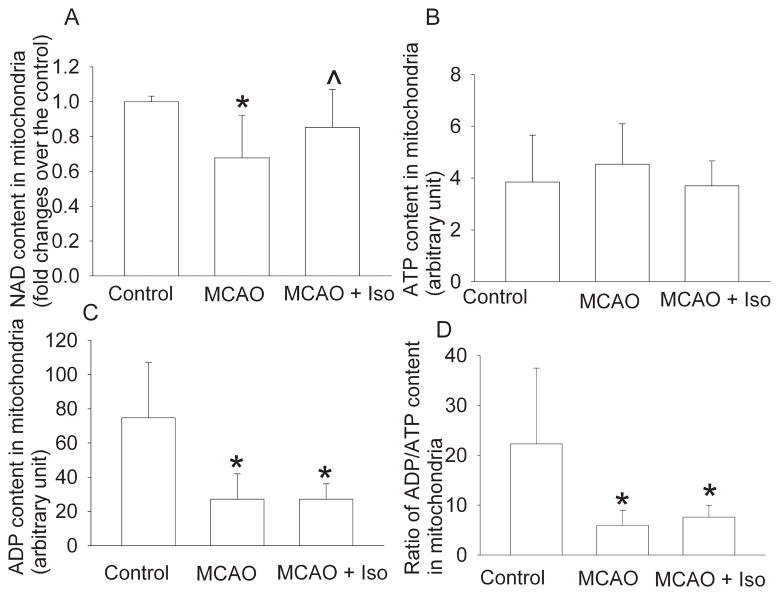

We have shown that postconditioning with 2% isoflurane for 1 h significantly reduces infarct volumes and improves neurological functions after a 90-min MCAO in rats (Lee et al., 2008). In this study, no animals died during the experimental procedure because we scheduled to harvest brain tissues at 1 h after the onset of reperfusion. The 90-min MCAO decreases the mitochondrial NAD concentrations in the ischemic penumbral brain tissues of rats. This decrease was partly attenuated by isoflurane postconditioning (Fig. 1). Reduction of the mitochondrial NAD concentrations has been used as an indicator for the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) (Feng et al., 2005). Our results suggest that the ischemia-reperfusion-increased mitochondrial membrane permeability is attenuated by isoflurane postconditioning. No matter whether the rats had MCAO or MCAO plus isoflurane postconditioning, the mitochondrial ATP concentrations in the ischemic penumbral brain tissues were not altered when compared with those in control rat brains. However, the mitochondrial ADP concentrations and the ratios of ADP/ATP were significantly reduced in the ischemic penumbral tissues. These reductions were not affected by isoflurane postconditioning (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Isoflurane postconditioning effects on mitochondrial nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) contents.

Adult male rats were subjected to a right 90-min middle cerebral arterial occlusion (MCAO) followed with or without a 60-min exposure to 2% isoflurane (Iso). Control animals were not subjected to brain ischemia or isoflurane exposure. The right frontal cortex area 1 was harvested to prepare the mitochondria at 1 h after the onset of reperfusion or immediately after the end of the isoflurane exposure. The contents of NAD, ATP and ADP, and the ratio of ADP to ATP in the mitochondria are presented in panel A, B, C and D, respectively. Results are mean ± S.D. (n = 10 for panel A and 4 for the other three panels). * P < 0.05 compared to control. ^ P < 0.05 compared to MCAO only.

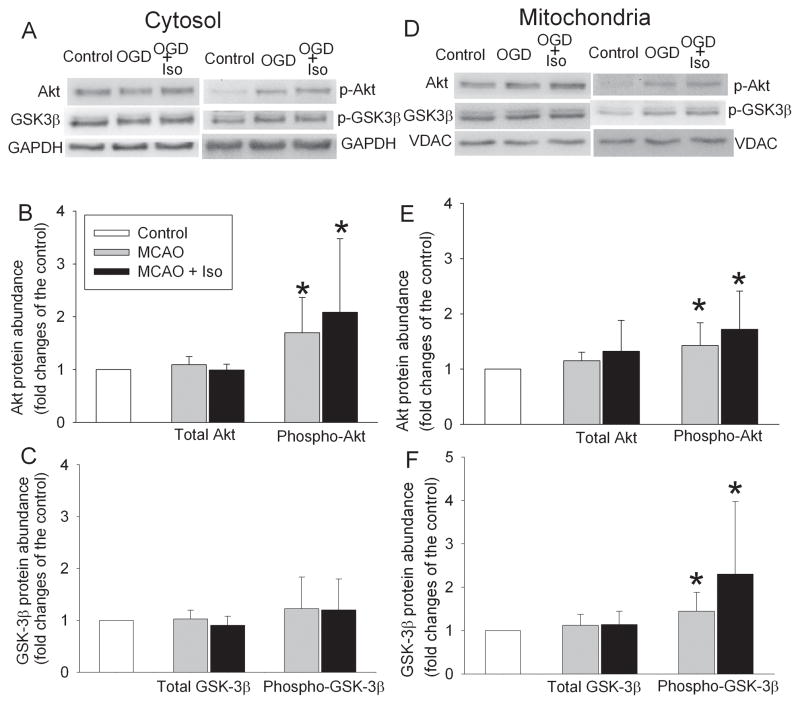

MCAO or MCAO plus isoflurane postconditioning did not change the expression of total Akt or GSK-3β in the mitochondrial or cytosolic fraction of the ischemic penumbral brain tissues. However, phospho-S473-Akt in the cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions of the ischemic penumbral brain tissues of rats subjected to MCAO or MCAO plus isoflurane postconditioning was significantly increased compared to control. The mitochondrial phospho-S9-GSK-3β also was increased in the ischemic penumbral brain tissues (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Effects of isoflurane postconditioning on protein kinase B/Akt and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β) expression.

Adult male rats were subjected to a right 90-min middle cerebral arterial occlusion (MCAO) followed with or without a 60-min exposure to 2% isoflurane (Iso). Control animals were not subjected to brain ischemia or isoflurane exposure. The right frontal cortex area 1 was harvested to prepare the mitochondrial or cytosolic fractions for Western blotting at 1 h after the onset of reperfusion or immediately after the end of the isoflurane exposure. Results are mean ± S.D. (n = 6). * P < 0.05 compared to control.

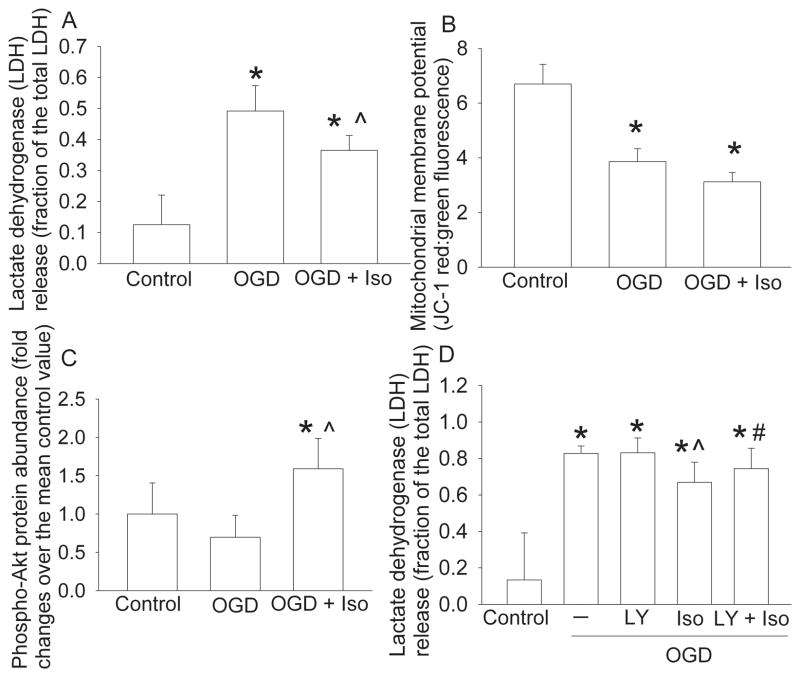

Consistent with the in vivo neuroprotective effects of isoflurane postconditioning, isoflurane postconditioning also reduced OGD and simulated reperfusion-induced LDH release in the primary cortical neuronal cultures. In the sister cells, OGD and simulated reperfusion also reduced the MMP. However, this reduction was not affected by isoflurane postconditioning. In another set of experiments, isoflurane postconditioning significantly increased phospho-Akt expression compared with the control or OGD conditions. In addition, the reduction of OGD-simulated reperfusion-induced LDH release by isoflurane postconditioning was attenuated by LY294002, an Akt signaling pathway inhibitor (Vlahos et al., 1994). LY294002 alone did not affect the OGD-simulated reperfusion-induced LDH release (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Isoflurane postconditioning-induced neuroprotection in the rat primary neuronal cultures.

The neuronal cultures were subjected to oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) for 1 h followed with or without an exposure to 2% isoflurane for 1 h (Iso) immediately after the OGD. Control cells were not exposed to OGD or isoflurane. (A) Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release was assayed at 24 h after the OGD or at the corresponding time for control cells. (B) The sister cells of those used in panel A were assessed for mitochondrial membrane potential at 1 h after the OGD or immediately after the isoflurane postconditioning. (C) Akt phosphorylated at S473 was measured at 1 h after the OGD or immediately after the isoflurane postconditioning. (D) The neuronal cultures were incubated with or without 10 μM LY294002 for 1 h during the OGD. The LDH release was assayed at 24 h after the OGD. LY: LY294002. Results are mean ± S.D. (n = 12 for panel A, 6 for panel B, 8 for panel C and 9 for panel D). * P < 0.05 compared to control. ^ P < 0.05 compared to OGD only. # P < 0.05 compared with OGD plus isoflurane postconditioning.

Discussion

Ischemia and reperfusion can increase the mitochondrial membrane permeability. The release of intramitochondrial contents, such as cytochrome C, into the cytosol activates apoptotic pathways, which ultimately leads to cell death (Kroemer et al., 2007). Apoptosis may be a major form of cell death in the ischemic penumbral brain tissues. Consistent with this mechanism, our results showed that ischemia and reperfusion reduced mitochondrial NAD content, an indicator for the increased mPTP opening (Feng et al., 2005), in the ischemic penumbral brain tissues of rats. Isoflurane postconditioning attenuated ischemia-reperfusion-induced NAD decrease in the mitochondria. These results suggest that isoflurane postconditioning may reduce the increased mPTP opening after brain ischemia and reperfusion, a possible mechanism for isoflurane postconditioning-induced neuroprotection.

The mitochondrial membrane permeability can be increased by activated GSK-3β under ischemia and reperfusion condition (Kroemer et al., 2007). Part of the mechanisms for Akt to provide prosurvival effects is to reduce GSK-3β activation/activity (Juhaszova et al., 2004; Kroemer et al., 2007). Our results showed that ischemia and reperfusion increased the activated/phosphorylated Akt in the cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions. The GSK-3β phosphorylated at S9 in the mitochondrial fraction also was increased. Since phosphorylation at S9 decreases GSK-3β activity (Cole et al., 2004), this result is consistent with the known effect that Akt reduces GSK-3β activation (Juhaszova et al., 2004; Kroemer et al., 2007). S9 in GSK-3β also is a known phosphorylation site for Akt (Wang et al., 1994). Thus, ischemia and reperfusion appear to activate Akt and then inhibit GSK-3β to attenuate the increase of mitochondrial membrane permeability under these pathological processes. This effect seems to be enhanced by isoflurane postconditioning because rats exposed to MCAO plus isoflurane post-treatment trended to have higher levels of phosphorylated Akt and GSK-3β than animals exposed to MCAO only, although the difference in the amount of phosphorylated Akt and GSK-3β between these two groups of animals was not statistically significant. In support of this in vivo finding, we have showed that isoflurane postconditioning significantly inhibits GSK-3β and that this inhibition may play an important role in isoflurane postconditioning in human neuron-like cultures (Lin et al., 2011).

The possible involvement of Akt activation in the isoflurane postconditioning-induced neuroprotection is supported by our results from the primary cortical neuronal cultures. Isoflurane postconditioning increased phosphorylated/activated Akt expression. LY294002, an Akt signaling pathway inhibitor (Vlahos et al., 1994), inhibited isoflurane postconditioning-induced neuroprotection; whereas LY294002 alone did not affect the OGD-simulated reperfusion-induced neuronal injury. Consistent with our conclusion, activation of Akt signaling pathway has been suggested to be involved in the isoflurane postconditioning-induced neuroprotection in neonatal rats after brain ischemia-hypoxia insult (Zhou et al., 2010).

Detrimental insults, such as ischemia and reperfusion, reduce the MMP (Juhaszova et al., 2004), which is often associated with an increase of the mitochondrial membrane permeability. Our results showed that OGD and simulated reperfusion reduced the MMP in the cortical neuronal cultures. However, this reduction was not attenuated by isoflurane postconditioning. Since isoflurane postconditioning may reduce the ischemia-reperfusion-increased mitochondrial membrane permeability in our study, it seems that there is dissociation between the changes in MMP and mitochondrial membrane permeability under isoflurane postconditioning condition. The reasons for this dissociation are not clear. Although decreased MMP can lead to increased opening of mPTP, various pathophysiological conditions including oxidative stress, acidosis and activation of protein kinases and phosphatases also regulate the opening of mPTP (Paillard et al., 2009; Zorov et al., 2009). In our study, the dissociation between the decreased MMP and attenuation of increased mitochondrial membrane permeability under isoflurane post-treatment condition may be due to the activation of Akt, which may directly reduce the increase of mitochondrial membrane permeability through GSK-3β inhibition without the involvement of changing the MMP. Similar to our findings, a previous study showed that ischemic postconditioning reduced ischemia-reperfusion-induced mPTP opening but did not affect ischemia-reperfusion-induced decrease of the MMP in rabbit hearts (Paillard et al., 2009).

Ischemia causes significant decrease of the mitochondrial adenine nucleotides. This effect is mostly due to degradation of those nucleotides into adenosine that is then leaked out into the cytosol (Watanabe et al., 1983). The reduction of ATP under ischemic condition may be mainly due to reduced synthesis (Classen et al., 1989). Direct leakage of intramitochondrial adenine nucleotides may not occur in relatively short ischemia or anoxia periods (< 120 min) (Watanabe et al., 1983; Dos Santos et al., 2002). Consistent with these findings, the mitochondrial ADP contents were significantly reduced in the ischemic penumbral brain tissues of rats. However, the mitochondrial ATP contents were not changed after brain ischemia and reperfusion. The reasons for this unchanged ATP contents may include that the synthesis of ATP has resumed during the 1-h reperfusion, which has masked the reduction of ATP during the ischemia period. The mitochondrial ATP is often transported to cytosol for use by ATP/ADP translocase (Pebay-Peyroula et al., 2003). This translocase may not function well during the ischemia period, which attenuates the reduction of the mitochondrial ATP contents under this pathological condition. Our results showed that isoflurane postconditioning did not affect the mitochondrial ATP and ADP contents after ischemia and reperfusion, suggesting that isoflurane postconditioning may not significantly affect the mitochondrial energy supply/adenine nucleotide metabolism in the ischemic penumbral brain tissues to provide neuroprotection.

We observed an increased phosphorylated/activated Akt in the cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions under MCAO or MCAO plus isoflurane post-treatment conditions. However, those experimental conditions increased phospho-GSK-3β at S9 only in the mitochondrial fraction but not in the cytosolic fraction. The reasons for the failed increase of phospho-GSK-3β in the cytosolic fraction in the context of increased activated Akt are not clear. However, it is known that the phosphorylation status of GSK-3β is regulated by multiple protein kinases and phosphatases (Zorov et al., 2009).

In summary, we have shown that isoflurane postconditioning may reduce ischemia-reperfusion-increased mitochondrial membrane permeability. This effect may be due to the activation of the Akt signaling pathway. The activation of this prosurvival pathway may contribute to the ultimate neuroprotection caused by isoflurane postconditioning.

Research highlights.

Post-treatment with the anesthetic isoflurane induces neuroprotection in rats.

Isoflurane post-treatment reduces ischemia/reperfusion-induced mitochondrial membrane permeability

Isoflurane post-treatment-induced neuroprotection may be mediated by protein kinase B/Akt

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant (R01 GM065211 to Z Zuo) from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, by a grant from the International Anesthesia Research Society (2007 Frontiers in Anesthesia Research Award to Z Zuo), Cleveland, Ohio, by a Grant-in-Aid from the American Heart Association Mid-Atlantic Affiliate (10GRNT3900019 to Z Zuo), Baltimore, Maryland, and the Robert M. Epstein Professorship endowment, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia.

Abbreviations

- ADP

adenosine diphosphate

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- Fr1

frontal cortex area 1

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GSK-3β

glycogen synthase kinase 3β

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- MCAO

middle cerebral arterial occlusion

- MMP

mitochondrial membrane potential

- mPTP

mitochondrial permeability transition pore

- NAD

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- OGD

oxygen-glucose deprivation

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PBST

phosphate buffered saline containing Tween-20

- tPA

tissue plasminogen activator

- VDAC

voltage-dependent anion channel

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Classen JB, Mergner WJ, Costa M. ATP hydrolysis by ischemic mitochondria. J Cell Physiol. 1989;141:53–59. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041410109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole A, Frame S, Cohen P. Further evidence that the tyrosine phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) in mammalian cells is an autophosphorylation event. Biochem J. 2004;377:249–255. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos P, Kowaltowski AJ, Laclau MN, Seetharaman S, Paucek P, Boudina S, Thambo JB, Tariosse L, Garlid KD. Mechanisms by which opening the mitochondrial ATP- sensitive K(+) channel protects the ischemic heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H284–295. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00034.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang MC, Cutler DM, Rosen AB. Trends in thrombolytic use for ischemic stroke in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:406–409. doi: 10.1002/jhm.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Lucchinetti E, Ahuja P, Pasch T, Perriard JC, Zaugg M. Isoflurane postconditioning prevents opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore through inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:987–995. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200511000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai K, Hayashi T, Chan PH, Zeng J, Yang GY, Basus VJ, James TL, Litt L. PI3K inhibition in neonatal rat brain slices during and after hypoxia reduces phospho-Akt and increases cytosolic cytochrome c and apoptosis. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;124:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingall T. Stroke--incidence, mortality, morbidity and risk. J Insur Med. 2004;36:143–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhaszova M, Zorov DB, Kim SH, Pepe S, Fu Q, Fishbein KW, Ziman BD, Wang S, Ytrehus K, Antos CL, Olson EN, Sollott SJ. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta mediates convergence of protection signaling to inhibit the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1535–1549. doi: 10.1172/JCI19906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JA, Li L, Zuo Z. Isoflurane induces a postconditioning effect on bovine pulmonary arterial endothelial cells exposed to oxygen-glucose deprivation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;615:144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Brenner C. Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in cell death. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:99–163. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JJ, Li L, Jung H-H, Zuo Z. Postconditioning with isoflurane reduced ischemia-induced brain injury in rats. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:1055–1062. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181730257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Peng L, Zuo Z. Isoflurane preconditioning increases B-cell lymphoma-2 expression and reduces cytochrome c release from the mitochondria in the ischemic penumbra of rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;586:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.02.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Li G, Zuo Z. Volatile anesthetic post-treatment induces protection via inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta in human neuron-like cells. Neuroscience. 2011;179:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.01.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton P. Ischemic cell death in brain neurons. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1431–1568. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Smith BL, Matthews TJ, Ventura SJ. Births and Deaths: Preliminary Data for 1998. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 1999;47:1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurtrey RJ, Zuo Z. Isoflurane preconditioning and postconditioning in rat hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 2010;1358:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memezawa H, Minamisawa H, Smith M-L, Siesjo BK. Ischemic penumbra in a model of reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. Exp Brain Res. 1992;89:67–78. doi: 10.1007/BF00229002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa H, Kogure K. Correlation between cerebral blood flow and histologic changes in a new rat model of middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 1989;20:1037–1043. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.8.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paillard M, Gomez L, Augeul L, Loufouat J, Lesnefsky EJ, Ovize M. Postconditioning inhibits mPTP opening independent of oxidative phosphorylation and membrane potential. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:902–909. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pebay-Peyroula E, Dahout-Gonzalez C, Kahn R, Trezeguet V, Lauquin GJ, Brandolin G. Structure of mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier in complex with carboxyatractyloside. Nature. 2003;426:39–44. doi: 10.1038/nature02056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves MJ, Arora S, Broderick JP, Frankel M, Heinrich JP, Hickenbottom S, Karp H, LaBresh KA, Malarcher A, Mensah G, Moomaw CJ, Schwamm L, Weiss P. Acute stroke care in the US: results from 4 pilot prototypes of the Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Registry. Stroke. 2005;36:1232–1240. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000165902.18021.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahos CJ, Matter WF, Hui KY, Brown RF. A specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, 2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (LY294002) J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5241–5248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang QM, Fiol CJ, DePaoli-Roach AA, Roach PJ. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta is a dual specificity kinase differentially regulated by tyrosine and serine/threonine phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14566–14574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe F, Kamiike W, Nishimura T, Hashimoto T, Tagawa K. Decrease in mitochondrial levels of adenine nucleotides and concomitant mitochondrial dysfunction in ischemic rat liver. J Biochem. 1983;94:493–499. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao ZQ, Corvera JS, Halkos ME, Kerendi F, Wang NP, Guyton RA, Vinten-Johansen J. Inhibition of myocardial injury by ischemic postconditioning during reperfusion: comparison with ischemic preconditioning. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H579–588. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01064.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S, Zuo Z. Isoflurane preconditioning reduces Purkinje cell death in an in vitro model of rat cerebellar ischemia. Neuroscience. 2003;118:99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00767-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Lekic T, Fathali N, Ostrowski RP, Martin RD, Tang J, Zhang JH. Isoflurane posttreatment reduces neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in rats by the sphingosine-1-phosphate/phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt pathway. Stroke. 2010;41:1521–1527. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.583757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorov DB, Juhaszova M, Yaniv Y, Nuss HB, Wang S, Sollott SJ. Regulation and pharmacology of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;83:213–225. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]