Abstract

There is potential that the pathological effects of oxidative stress (OS) associated diseases such as diabetes could be ameliorated with antioxidants, but this will require a clearer understanding of the pathway(s) by which proteins are damaged by OS. This study reports the development and use of methods that assess the efficacy of dietary antioxidant supplementation at a mechanistic level.

Data reported here evaluate the impact of green tea supplementation on oxidative stress induced post-translational modifications (OSi-PTMs) in plasma proteins of Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rats. The mechanism of antioxidant protection was examined through both the type and amount of OSi~PTMs using mass spectrometry based identification and quantification.

Carbonylated proteins in freshly drawn blood samples were derivatized with biotin hydrazide. Proteins thus biotinylated were selected from plasma samples of green tea fed diabetic rats and control animals by avidin affinity chromatography, further fractionated by reversed phase chromatography (RPC), fractions from the RPC column were tryptic digested, and the tryptic digest fractionated by RPC before identified by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). Relative quantification of peptides bearing carbonylation sites was achieved for the first time by RPC-MS/MS using selective reaction monitoring (SRM). Seventeen carbonylated peptides were detected and quantified in both control and treated plasma. The relative concentration of eight was dramatically different between control and green tea treated animals. Seven of the OSi-PTM bearing peptides had dropped dramatically in concentration with treatment while one increased, indicating differential regulation of carbonylation by antioxidants. Green tea antioxidants were found to reduce carbonylation of proteins by lipid peroxidation end products most, followed by advanced glycation end products to a slightly lower extent. Direct oxidation of proteins by reactive oxygen species (ROS) was protected the least by green tea.

Keywords: Carbonylation, oxidative stress, biotin hydrazide, antioxidants, green tea, catechins, and selective reaction monitoring

INTRODUCTION

Interest in antioxidant supplements for treatment of oxidative stress related diseases has increased dramatically in the last decade. As a consequence several in vitro and in vivo assays have been developed to assess antioxidant efficacy. In vitro evaluation methods such as the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay or the horseradish peroxidase-luminol-hydrogen peroxide assay correlate poorly with observed in vivo efficacy1 2. This has been attributed to the interaction of antioxidants with food constituents, in vivo degradation, inadequate bioavailability, and their location relative to reactive oxygen species. in vivo assays of antioxidant efficacy are probably more direct, measuring the decrease in lipid oxidation in the thiobarbituric acid test3 or DNA oxidation with the 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine test4.

Assessing the impact of antioxidants on protein oxidation is another approach. It is known that antioxidants diminish protein oxidation based on assays for protein carbonyl content (PCC).5 The PCC assay estimates carbonyl content in proteins by derivatization of carbonyl residues with the yellow 2,4-dinitrophenyl hydrazine reagent. Subsequent to protein pull-down, the degree of carbonylation in resuspended proteins is determined colorimetrically. 6 The problem with this assay is that it lacks specificity, being incapable of differentiating between the level of oxidation among individual proteins, oxidation at specific sites in a protein, or the pathway by which site specific oxidation occurs. Another test of OS is measurement of the total 3-nitrotyrosine released after acid treatment or proteolytic digests.7 Again this assay lacks specificity. Finally, an approach was developed that measures the effects of antioxidants on the total protein expression levels using two dimensional gel electrophoresis8-10. Although more specific, this method does not assess oxidation pathways or sites of modification in proteins. Recent studies have shown that in general, fifty to several hundred proteins are oxidized in a single OS episode, some being oxidized more than others along with variability in specific site modifications.11-16 Clearly the assay methods described above lack the requisite specificity and resolution to assess the impact of an antioxidant on a biological system. A more sophisticated approach is needed.

Based on recently described proteomics methods for targeting the isolation and identification of carbonylated proteins it is known that i) carbonylation is a universal indicator of oxidative stress11, ii) carbonylated proteins are easily selected in a proteome11, iii) these proteins carry multiple forms of oxidative stress induced post- translational modifications12, 13, iv) sites and types of oxidative modification can be identified in individual proteins12, 13, and v) carbonylated signature proteins appear reproducibly in plasma12. This study reports a new method that allows multiple characteristics of an antioxidant to be assessed simultaneously in suppression of protein carbonylation. Among the properties being appraised are 1) the oxidation mechanism the antioxidant suppresses most successfully, 2) the degree to which specific sites in a protein are protected from oxidation in vivo, and 3) which proteins experience the greatest suppression of carbonylation.

It is important in evaluating the therapeutic efficacy of an antioxidant to have a baseline signature, particularly in the case of a disease. This has been achieved recently with Zucker diabetic (ZDF) rats in which oxidative stress induced post-translational modifications (OSi~PTMs) were recently identified during the course of type II diabetes mellitus 17. Moreover, the methods used to assess carbonylation were identical to those used in this study”

Oxidative stress is affected by multiple factors including; disease18, age,19, 20 gender,21 diet, exercise,22 rest,23 drugs, (e.g. Adriamycin24 and Doxorubicin25), environmental exposure,26 seasonal variability,27 surgery28 and smoking.29 Therefore Zucker diabetic rats were used a model system to reduce experimental variables.

The antioxidant studies reported here were achieved by supplementing the diet of Zucker ZDF diabetic rats with green tea (Camellia sinensis). Green tea was selected as the antioxidant source based on the fact that epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) in tea leaves has been shown to have strong antioxidant efficacy30, 31.

Data reported here were derived from comparative proteomics studies in green tea treated diabetic and diabetic control rats that assessed qualitative and quantitative differences in the carbonylation of proteins shed in the blood during the course of differential dietary supplementation with green tea. Carbonylated proteins in blood samples were derivatized with biotin hydrazide (BH) upon collection and the resulting Schiff’s bases reduced with sodium cyanoborohydride. Subsequent to removal of excess BH by dialysis, biotinylated proteins were selected by avidin affinity chromatography. This affinity enriched, carbonylated protein fraction was then further fractionated by reversed phase chromatography (RPC), trypsin digested, and carbonylated peptides identified and quantified by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The materials used in this study are listed in the text after Table S-2 in Supporting Information (titled Materials).

Animal Model

All animal experimentation was approved by the Purdue Animal Care and Use Committee. Zucker diabetic (ZDF) rats were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Rats were obtained at 6 weeks of age and gavaged with green tea (85mg catechins/Kg) or water twice daily for 6 weeks. The green tea powder utilized in this study is a hot water extract of green tea (A gift from the Nestle Product Technology Center, Marysville, OH) provided to the laboratory of Professor Mario Ferruzzi (Purdue University). The light/dark cycle of the room was reversed for the dosing schedule to correspond to the feeding cycle of the rats. Blood was harvested at sacrifice (12 weeks of age) and used for proteomic analysis.

Biotinylation of the plasma samples

Five diabetic and five green tea treated diabetic rats were sacrificed at 12 weeks and blood collected in a venous blood Vacutainer™ collection tube coated with EDTA (Fisher Scientific, Hanover Park, IL, USA). Generally one tablet of protease inhibitor cocktail was dissolved in distilled water and added to prevent proteolysis during storage. Biotin hydrazide was then added at a final concentration of 5mM. The resulting Schiff’s bases were then reduced by sodium cyanoborohydride and the samples were dialyzed to remove unreacted BH. A detailed protocol for the biotinylation of plasma samples can be found in the text after Table S-2 in the Supporting Information.

Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry

Avidin affinity chromatography was used to purify biotinylated proteins from the plasma. Protein purified were further fractionated by a propylsilane (C3) reversed phase chromatography (RPC) before trypsin digestion of proteins in the RPC fractions and LC-MS/MS analysis (nanoUPLC instrument coupled to a QSTAR workstation) of the tryptic peptides as described previously.17 Detailed protocols are listed in the text after Table S-2 in the Supporting Information (titled Purification of the biotinylated proteins using avidin affinity chromatography, Separation of biotinylated proteins using reversed phase chromatography, Proteolysis and LC/MS/MS of digested fractions) An in-house MASCOT server (Version 2.2, Matrix Science, London, U.K.32) was used to process the mass spectrometric data. A complete list of the parameters used for Mascot database searches are included in Supporting Information (Data processing). This resulted in the identification of the carbonylation sites. To provide quantitative comparison of the levels of carbonylation sites, SRM analysis targeted the carbonylated peptides in the pooled plasma of green tea fed diabetic rats and their diabetic controls. For these experiments, Agilent 6410 triple quadrupoles ((Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used as described previously 17. The details for the SRM analysis can be found in the text after Table S-2 in the Supporting Information (titled Relative quantification of carbonylation sites using selective reaction monitoring (SRM).

RESULTS

Model system

Zucker diabetic rat is homozygous for a leptin receptor defect, becoming obese and developing diabetes naturally at about 7 weeks of age. Animals were fed a Purina 5008 chow diet supplemented with green tea. Methods from a previous study on oxidative stress induce carbonylation13,17 were adapted to measure antioxidant efficacy based on changes in carbonylation at specific sites in proteins as a function of antioxidant (green tea) supplementation.

Analytical plan

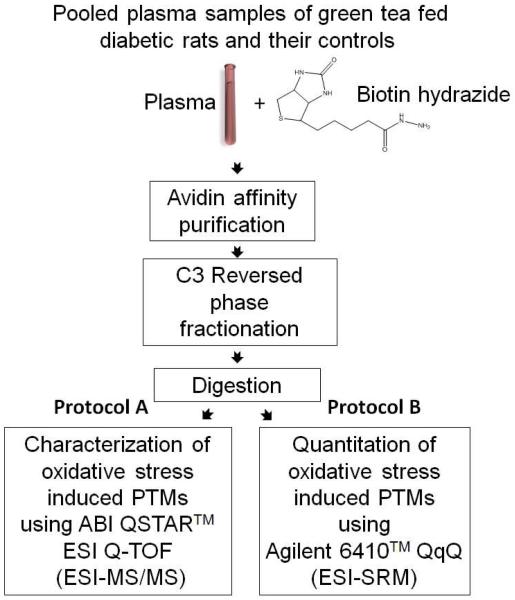

The objectives of the study reported here were to i) identify proteins that had undergone carbonylation, ii) determine sites of oxidation in these proteins, iii) ascertain the pathway by which oxidation occurred at these sites, and iv) measure the degree of protection supplied by antioxidant therapy. The analytical plan to achieve these goals arose from integration of methods developed in a series of previous studies ranging from studies of protein carbonylation in yeast13 to the identification of carbonylated proteins in plasma of diabetic Zucker ZDF rats17. Plasma samples were derived from each of five green tea fed Zucker diabetic rats and five control Zucker ZDF diabetic animals. Following biotinylation of carbonylated plasma proteins with biotin hydrazide, proteins thus derivatized were selected from pooled plasma through avidin affinity chromatography and further fractionated by a propylsilane (C3) reversed phase chromatography (RPC) before trypsin digestion of proteins in the RPC fractions and LC- MS/MS analysis of the tryptic peptides (Figure 1A and 1B). Two or more un-modified tryptic peptides were used to identify affinity selected peptides while OSi-PTM sites in these proteins were identified based on mass spectrometry based sequence analysis the location of biotin in the sequence. Among the~50 different types of OSi-PTM associated with biotin hydrazide derivatization, all are recognizable by mass spectral analysis. Subsequent to protein and site specific localization of OSi-PTMs, relative changes in their concentration were quantified using an Agilent Triple Quad 6410 LC/MS in the selected reaction monitoring (SRM) mode of detection (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the strategy used for the identification, quantification, characterization, and carbonylation site assignment in proteins from the plasma of green tea fed diabetic rats and diabetic controls. Five samples from each of the green tea fed diabetic and their control diabetic rats were pooled to enrich the oxidation sites and these sites were then i) characterized using LC-ESI-MS/MS (protocol A) and ii) quantified by selective reaction monitoring (SRM) (protocol B).

Avidin Affinity Selection

As described in previous studies12, 17 involving the detection of carbonylated proteins in the plasma, highly abundant proteins were not removed prior to analysis for several reasons. One is that some of the oxidized isoforms of proteins can be crosslinked or complexed with abundant proteins. It has been shown previously that abundant protein removal by immunoaffinity chromatography results in the removal of at least 129 nonspecifically bound proteins.33 This means that abundant protein removal could lead to the loss of some carbonylated isoforms. Still another reason is that mathematical modeling has shown that washing affinity columns with 15 or more column volumes of the loading buffer removes most the non-specifically bound proteins.34 More than 60 column volume washes were used in this work. Return of detector absorbance to zero on a milli-absorbance scale was used to determine that non-specifically bound proteins had been eluted. The affinity column was tested periodically with standard biotinylated bovine serum albumin as a control to assess proper operation. Approximately 5 mgs of plasma proteins were loaded on the avidin affinity column using a PBS (0.15M, pH 7.4) loading buffer at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Proteins selected in this manner were then eluted by switching to 0.1 M dimethylglycine (pH 2.5).

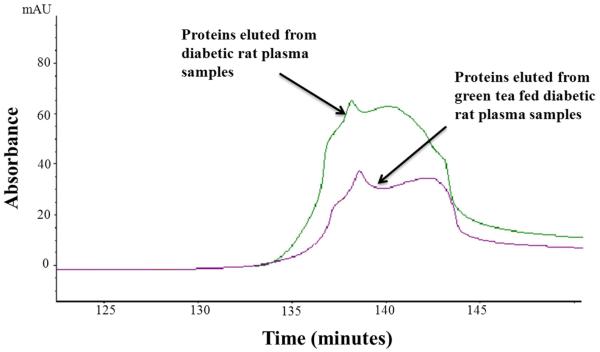

Using absorbance at 280 nm and assuming that affinity selected and unbound proteins have the same extinction coefficient, approximately 1.7% (SD=0.0014) of the protein in Zucker diabetic rat plasma was bound to the avidin affinity column compared to 1.2% (SD=0.2) from green tea fed diabetic rat plasma, p<0.05 (Figure 2). It should be noted that naturally biotinylated proteins, proteins naturally complexed with or crosslinked to the biotinylated proteins, and non-specifically bound proteins are included in this affinity selected fraction as well.13

Figure 2.

Avidin affinity chromatogram of Zucker diabetic rat plasma samples (green line) overplayed on that of a green tea fed diabetic rat plasma sample (purple line). Plasma samples (each with 5mg of total protein) were applied directly to a 4.6 × 100 mm avidin column packed with UltraLink Biosupport™ to which avidin had been immobilized. The column was washed initially with 0.15 M phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4) at 0.5 mL/min for 120 min, then switched to a mobile phase containing 0.1M dimethylglycine / HCl(pH 2.5) for an additional 40 min wash at the same flow rate. Absorbance was monitored at 280 nm. Based on absorbance measurements, an average of 1.2 % of the total protein from a pooled (5 animals) plasma sample drawn from green tea fed diabetic rat was captured by avidin affinity chromatography (SD= 0.2). In contrast, the relative amount of protein captured from a pooled (5 animals) plasma sample drawn from diabetic control rats was 1.7% (SD=0.0014).

Oxidation site detection and quantification measurements

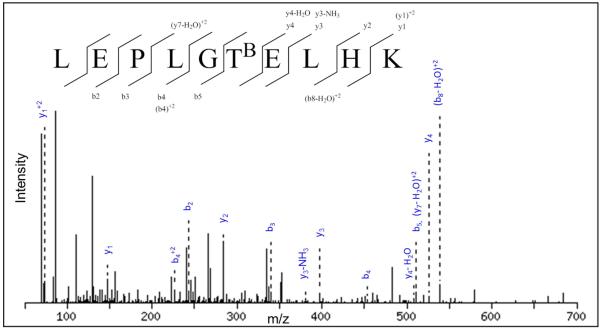

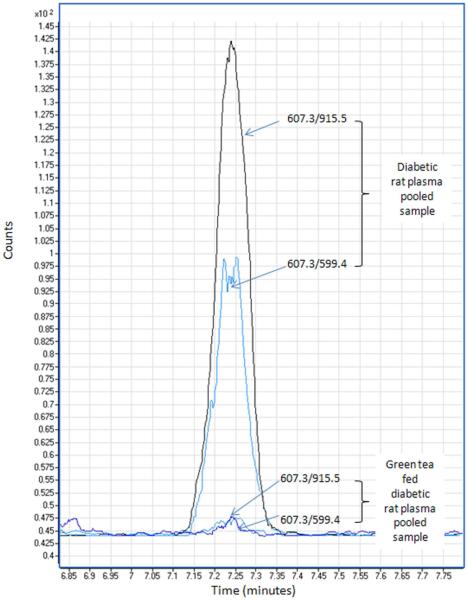

As noted above, the affinity selected protein fraction was further fractionated by RPC on a propylsilane (C3) bonded phase column. Fractions collected from the RPC column were then digested with trypsin and carbonylation sites, or more specifically biotinylation sites were detected with a QSTAR ESI/MS/MS and quantified by ESI/SRM with an Agilent 6410 Triple Quadrapole LC/MS. A prerequisite in carbonylation site identification is that unmodified-peptides from a protein must be identified in the C3 RPC fraction before an OSi~PTM peptide identification from the same protein can be accepted. Having identified un-modified peptides from a protein, confidence in the identification of OSi~PTM bearing peptide along with the modification site is much higher. Figure 3 shows an example MS/MS spectrum for a carbonylated peptide where we were able detect the oxidation of T147 in preproapolipoprotein A-I to 2-amino-3-ketobutyric acid. Going to the SRM method for quantification was selected for two reasons. One was that carbonylated peptide detection could be achieved at levels far below the detection limit possible with LC/ESI/MS/MS. The second was that further validation of carbonylation sites was achieved during detection of multiple product ions from each OSi~PTM bearing peptide. An example of the transitions used to quantify carbonylated peptides is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

MS/MS spectrum of the biotinylated peptide LEPLGTBELHK from preproapolipoprotein A-I . TB indicates a biotinylated oxidized threonine residue (2-amino-3-ketobutyric acid).

Figure 4.

Relative quantitation of carbonylated peptides using selective reaction monitoring (SRM). Peptide KVADALAK modified with HNE and then biotinylated through addition of the biotin hydrazide. The peptide was quantitated based on two transition, 915.5 (y5) and 599.4 (y2-NH3). As seen, the levels were reduced 25 fold in the pooled plasma sample from green tea fed diabetic rats compared to the pooled plasma sample from control diabetic animals.

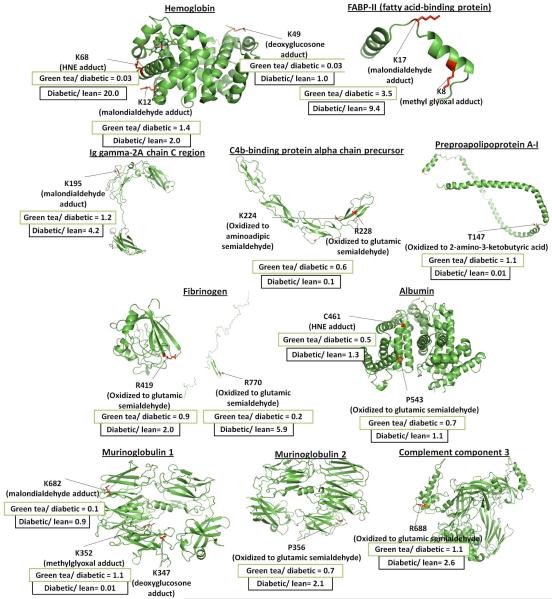

On the average 10625 spectra were obtained during the analysis of a sample. As shown in Figure 5, Table 1 and Supplemental Table S-1, seventeen carbonylation sites were detected and quantified. General structures of the carbonylation products detected in this study are shown in Supplemental Table S-2. Plasma samples from green tea treated animals were reduced more than 2 fold with seven carbonylation peptides. The modification sites were found at K68 of the hemoglobin alpha 2 chain, K49 of the hemoglobin beta-chain, R770 of fibrinogen alpha polypeptide isoform 1, K161 of Inter-alpha-inhibitor H4 heavy chain, R731 of murinoglobulin 1 homolog, K682 of murinoglobulin 1, and C461 of albumin.

Figure 5.

Carbonylation sites quantified using SRM. The figure shows average ratios for carbonylated peptides in diabetic rats to their lean controls17 and in green tea treated diabetic rats to their diabetic controls as detected in this study. Structures were made using the SWISS-MODEL Workspace software from the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. Each sequence was uploaded into the Modeling Workspace where the software finds the best structure template based on homology with other proteins of known structure. There was no known structure that could provide a template for the protein Inter-alpha-inhibitor H4 heavy chain and residue 731 of murinoglobulin 1. A complete list of carbonylation sites quantified using SRM can be found in Table 1 and Supplemental Table S-1.

Table 1.

A list of the carbonylation sites quantitated using SRM.

| Accession number |

Protein name | Oxidative modification | Average (diabetic /lean rat plasma pooled sample) 17 |

Average (green tea/diabetic rat plasma pooled sample) |

CV% (green tea/diabetic rat plasma) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gi |60678292 | Hemoglobin alpha 2 chain |

K68: Biotinylated HNE adduct | 20.0 | 0.03 | 20.0% |

| gi |204352 | Hemoglobin beta-chain | K49: Biotinylated deoxyglucosone adduct |

1.0 | 0.03 | 24.1% |

| gi |60678292 | Hemoglobin alpha 2 chain |

K12: Biotinylated malondialdehyde |

2.0 | 1.4 | 9.7% |

| gi |50657404 | Murinoglobulin 2 | P356: Biotinylated oxidized proline |

2.1 | 0.7 | 7.9% |

| gi |56797757 | Fibrinogen, alpha polypeptide isoform 1 |

R770: Biotinylated oxidized arginine |

5.9 | 0.2 | 8.6% |

| gi |56797757 | Fibrinogen, alpha polypeptide isoform 1 |

R419: Biotinylated oxidized arginine |

2 | 0.9 | 17.1% |

| gi |404382 | FABP-II (fatty acid- binding protein {N- terminal} |

K8:Biotinylated malondialdehyde adduct, K17:Biotinylated methyl glyoxal adduct |

9.4 | 3.5 | 3.6% |

| gi |2493792 | C4b-binding protein alpha chain precursor (C4bp) |

K224: Biotinylated oxidized lysine, R:228 Biotinylated oxidized arginine |

0.1 | 0.6 | 5.7% |

| gi |55391508 | Albumin | P543: Biotinylated oxidized proline |

1.1 | 0.7 | 5.2% |

| gi |121052 | Ig gamma-2A chain C region |

K195: Biotinylated malondialdehyde |

4.2 | 1.2 | 35.5% |

| gi |2292988 | Inter-alpha-inhibitor H4 heavy chain |

K161: Biotinylated malondialdehyde |

1 | 0.4 | 7.3% |

| gi |8393024 | Complement component 3 |

R688: Biotinylated oxidized arginine |

2.6 | 1.1 | 2.8% |

| gi |12831225 | Murinoglobulin 1 homolog |

R731: Biotinylated oxidized arginine |

1.2 | 0.4 | 14.2% |

| gi |55747 | Preproapolipoprotein A-I |

T147: Biotinylated oxidized threonine |

0.01 | 1.1 | 12.9% |

| gi |12831225 | Murinoglobulin 1 homolog |

K347: biotinylated deoxyglucosone adduct,K352: biotinylated methylglyoxal |

0.01 | 1.1 | 10.8% |

| gi |12831225 | Murinoglobulin 1 homolog |

K682: Biotinylated malondialdehyde |

0.9 | 0.1 | 13.1% |

| gi |55391508 | Albumin | C461:HNE adduct | 1.3 | 0.5 | 1.5% |

Among the six carbonylated peptides that didn’t change significantly between the diabetic and lean animals, modifications at five were substantially reduced in association with green tea treatment. These modifications were found at K49 of the hemoglobin beta-chain, K161 of Inter-alpha-inhibitor H4 heavy chain, R731 of murinoglobulin 1 homolog, K682 of murinoglobulin 1, and C461 of albumin.

Surprisingly, some carbonylation sites were either not impacted by treatment with green tea or carbonylation increased. Carbonylation at site P543 in albumin was not affected while the peptide carrying two oxidation sites at K8 and K17 of FABP-II (fatty acid- binding protein) increased dramatically in treated versus control diabetic animals. Another anomaly was that of the three carbonylated peptides that unexpectedly decreased in the diabetic rat plasma samples compared to the lean controls, green tea had no significant impact on their concentration.

Among a total of nine direct carbonylation sites, green tea dramatically reduced oxidation at two; R770 of fibrinogen alpha polypeptide isoform 1 (with a ratio of 0.2 ) and R731 of murinoglobulin 1 homolog (with a ratio of 0.4). With the seven carbonylated peptides carrying ALE adducts (the HNE adduct on K68 of hemoglobin alpha 2 chain, malondialdehyde adduct on K12 of hemoglobin alpha 2 chain, malondialdehyde adduct on K8 of FABP-II (fatty acid-binding protein), malondialdehyde adduct on K195 Ig gamma-2A chain C region, malondialdehyde adduct on K161 of inter-alpha-inhibitor H4 heavy chain, malondialdehyde adduct on K682 of murinoglobulin 1 and HNE adduct on C461 of albumin), green tea dramatically reduced four of them (the HNE adduct on K68 of hemoglobin alpha 2 chain (with a ratio of 0.03), malondialdehyde adduct on K161 of Inter-alpha-inhibitor H4 heavy chain (with a ratio of 0.4), malondialdehyde adduct on K682 of murinoglobulin 1 (with a ratio of 0.1) and HNE adduct on C461 of albumin (with a ratio of 0.5) while the levels of one (K8 of FABP-II (fatty acid-binding protein)) increased (with a ratio of 3.5). Additionally, among the two carbonylated peptides carrying two AGE adducts (deoxyglucosone adducts on K49 of hemoglobin beta-chain and K347 of murinoglobulin 1 homolog), green tea dramatically reduced one of them (deoxyglucosone adducts on K49 of hemoglobin beta-chain with a ratio of 0.03). Methyl glyoxal adducts can be of either ALE or AGE origin.35 Among the two carbonylated peptides carrying methyl glyoxal adducts (on K17 of FABP-II (fatty acid-binding protein) and K352 of murinoglobulin 1 homolog), green tea increased one (on K17 of FABP-II (fatty acid-binding protein) with a ratio of 3.5 but had no effect on the other. Although cases were seen in which green tea reduced carbonylation by all of the three known pathways, ALE adduct formation was reduced most by green tea. Reduction of AGE adduct formation was the next most abundant while direct carbonylation was affected the least.

Finally, the most dramatic decrease in carbonylation induced by green tea was a 33 fold reduction of the HNE adduct at the K68 in the hemoglobin alpha 2 chain (with an average ratio of 0.03). The second most striking decrease was a 12 fold reduction in malondialdehyde adduct formation at K682 of the murinoglobulin 1 homolog (with an average ratio of 0.1).

DISCUSSION

An objective of this study was to develop a methodology for assessing the impact of dietary antioxidant supplementation on oxidative stress induced carbonylation of proteins. The strategy deployed in this study to assess antioxidant efficacy used methods described in the INTRODUCTION in addition to new SRM methods for quantifying biotinylated peptides.

The results in Figure 5, Table 1 and Supplemental Table S-1 show clearly that these methods (Figure 1) identify sites of carbonylation in a number of plasma proteins from rats and that carbonylation changes differentially in diabetic Zucker ZDF rats relative to lean controls as a function of both disease progression and antioxidant supplementation. Moreover, the label free SRM quantification method used in these studies was sufficiently sensitive to assess differences between biotinylated peptides of identical structure. This is a major advance beyond current methods that assess changes in bulk protein carbonylation based on the absorbance of 2,4-dinitophenyl hydrazine derivatives. Still to be developed are plasma methods that allow organ specific protein carbonylation to be identified and used to assess antioxidant therapy at the organ level. This may be possible as the sensitivity of mass spectrometers evolves, through the use of larger samples, or specific antibodies.

A second objective of this study was to determine the manner in which green tea supplementation impacted protein carbonylation in Zucker ZDF rats with type II diabetes17. As part of the analytical component of this work, sites of oxidation, oxidation pathways, and the extent of oxidative modifications within individual proteins were examined. Carbonylation sites were identified by MS/MS along with exploiting the sensitivity and selectivity of triple quadrapole based SRM methods to quantify changes in oxidation at these sites. It was found that green tea dramatically reduced the level of seven of seventeen OSi-PTM bearing peptides; primarily due to the presence of polyphenolic compounds in green tea. However, the level of one OSi-PTM bearing peptide increased. Clearly, antioxidant protection against carbonylation is not universal. One third of the dry weight of green tea is composed predominantly of flavonols known as catechins36 such as: epicatechin, epigallocatechin, epicatechin gallate and epigallocatechin gallate (Supplemental Figure S-1).36 Generally, these constituents showed large antioxidant activity. Administration of green tea has been shown to increase antioxidant potential in the serum of normal and dyslipidemic subjects.30 There is also evidence that green tea ameliorates oxidative stress in diabetes.37, 38

Based on data from this study the major effect of green tea was on ALE adduct formation. This is consistent with the observation that green tea reduces lipid peroxidation in rat plasma.39 It has also been shown that green tea almost completely blocks adduction formation between proteins in rats and 4-HNE formation that was induced by ethanol.40 Moreover, in rats subjected to aerobic exercise the level of lipid peroxidation was reduced by consumption of green tea.41 The mechanism by which this occurs has been attributed to the two hydroxyl groups of the catechol ring (Supplemental Figure S-1) forming hydrogen bonds with the lipid peroxyl radical, preventing it from contributing to lipid peroxidation.42

There is precedent for the impact of green tea supplementation on AGE adduct formation with proteins as well. Several studies have shown that radical species (e.g. superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide, and singlet oxygen) play an important role in AGE formation.43-45 Inhibition of oxidative stress pathways in vivo may be responsible for the inhibition of AGE formation seen in this study. Additionally, it has been shown that the gallate group (Supplemental Figure S-1) plays an important role in protection against protein oxidation and glycation.45 Another study showed that the administration of green tea significantly reduced AGE formation in the plasma of diabetic rats along with lipid peroxidation.37,46 Maillard-type fluorescence and collagen crosslinking induced by AGE formation is also reduced in the heart of diabetic rats47. Another reason for decreased formation of AGEs may be due to the reduction of glucose levels with green tea administration. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), one of green tea constituents (Supplemental Figure S-1) was shown to have many of the cellular effects of insulin, including the reduction of hepatic glucose production. These effects were exerted by changing the redox state of the cell.48 Additionally, green tea extract can produce an antidiabetic effect in diabetic mice by reducing insulin resistance49. Formation of diabetic cataracts was retarded through this hypoglycemic effect.50 It has been shown by this laboratory as well that green tea reduces glucose in ZDF rats51.

Green tea also had some effect on the level of direct carbonylation believed to arise from the chelation of metals like iron that scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS).52 For example, a previous study showed that green tea reduces iron and erythrocyte ROS in the rat plasma.39 Still another study showed that green tea reduced oxidative stress induced by tert-butylhydroperoxide treatment of cultured mouse C2C12 myotubes.53 Moreover, it also reduced the propensity of human LDL oxidation by CuSO4 xs54.

On the other hand, it’s not surprising to see an increased level of one of the carbonylated peptides. This may be due to the pro-oxidant action of green tea55. Additionally, it was previously shown that green tea could worsen glycoxidation in several tissues in diabetic rats56.

A critical point established by this work is that although antioxidant supplementation can have a large impact on protein carbonylation through different pathways, it is far from universal within a given pathway. There are huge differences in the degree to which carbonylation is altered by antioxidants between proteins being oxidized by the same pathway and even between sites in the same protein. The hemoglobin alpha 2 chain provides an example. Carbonylation at residues K12 and K68 in this protein occurs through ALE adduct formation. With the K12 modification the diabetic to lean ratio is 2.017 while the antioxidant treated diabetic to diabetic control ratio is 1.4, i.e. they are almost the same. In contrast, at K68 the ratio between diabetic and lean control animals was 20.017 while the ratio between antioxidant treated diabetic to un-treated diabetic control was 0.03. These two sites vary by more than 40 fold in the degree of protection obtained by green tea antioxidants. Clearly the regulatory mechanism for antioxidant protection against carbonylation by advanced peroxidation end products is more complicated than described above.48-50 Similar, but less dramatic results were seen with arginine oxidation at residues R419 and R770 in fibrinogen alpha polypeptide isoform 1. With the R770 modification the diabetic to lean ratio was 5.9 while the antioxidant treated diabetic to diabetic control ratio was 0.2. At residue R419 the diabetic to lean ratio is 2.0 while the antioxidant treated diabetic to diabetic control ratio is 0.9, i.e. they are almost the same. Again there is a substantial difference in the degree of antioxidant protection at two sites in a protein modified by the same pathway. Similar results were seen between different proteins being carbonylated through the same mechanism (e.g. ALE adduct formation) in the cases of Inter-alpha-inhibitor H4 heavy chain, hemoglobin, fatty acid binding protein, Ig gamma-2A chain C region, murinoglobulin 1 homolog, murinoglobulin 2, and albumin.

CONCLUSIONS

A series of conclusions can be made relative to antioxidant therapy in reducing oxidative stress initiated carbonylation of proteins. Based on the fact that the detection limit of peptides is more than ng/ml57 it can be concluded that the analytical methods described in this work are capable of measuring the impact of antioxidant therapy on specific carbonylation site when the protein bearing the modification occurs at concentrations above this detection limit and modified peptides from the protein can be transported into the gas phase by electrospray ionization. At this level of sensitivity proteins of intermediate to high abundance can be examined with ease. Lower abundance, carbonyl bearing proteins will have to be enriched by biotinylation with biotin hydrazide and avidin affinity chromatography.

A second conclusion that by using the mass spectrometry based methods described here to differentiate between protein carbonylation at specific sites it is possible to assess the efficacy of antioxidant therapy in suppressing carbonylation through a particular pathway, at specific sites, in intermediate to high abundance proteins. These methods take antioxidant efficacy assessment to a new level of specificity.

A third conclusion is that green tea antioxidants do in fact provide protection against oxidative stress induced carbonylation of proteins in Zucker ZDF diabetic rats in the cases of the ALE and AGE modification pathways. A small degree of protection was even afforded with ROS triggered oxidation in some cases. But protection was not universal. There are huge differences in protection between sites in a protein, among proteins being modified by the same mechanism, and probably between locations in a cell. Protection between organs was not examined in this study, but variations are expected there as well.

Although the studies described here were directed at method development and assessment, they make it abundantly clear that antioxidant protection is vastly more complicated than the simple mechanisms offered in the literature. From the data collected here it seems very unlikely that a single antioxidant or even a single food source bearing antioxidants will provide universal protection. Although the tools described here allow assessment of antioxidant therapy, vastly more work is required before antioxidant regulation is understood.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Special thanks to Dr. H. Dorota Inerowic for managing the Purdue Proteomics Facility. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of this work by the National Cancer Institute (grant number 1U24CA126480-01), the national institute of aging (grant number 5R01AG025362-02) and the Purdue University-University of Alabama at Birmingham Botanical Center for Age Related Diseases funded by the Office of Dietary Supplements and NCCAM grant P50 AT 00477 and the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute funded in part by grant # RR 02576 from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

REFERENCES

- (1).Cos P, Rajan P, Vedernikova I, Calomme M, Pieters L, Vlietinck AJ, Augustyns K, Haemers A, Vanden Berghe D. Free Radical Research. 2002;36:711–716. doi: 10.1080/10715760290029182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Georgetti Sandra R, Casagrande R, Di Mambro Valeria M, Azzolini Ana ECS, Fonseca Maria JV. AAPS pharmSci. 2003;5:E20. doi: 10.1208/ps050216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hermans N, Cos P, Vanden Berghe D, Vlietinck AJ, de Bruyne T. Journal of Chromatography, B Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences. 2005;822:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Podmore ID, Griffiths HR, Herbert KE, Mistry N, Mistry P, Lunec J. Nature (London) 1998;392:559. doi: 10.1038/33308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Levine RL, Garland D, Oliver CN, Amici A, Climent I, Lenz AG, Ahn BW, Shaltiel S, Stadtman ER. Methods in Enzymology. 1990;186:464–478. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86141-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Hermans N, Cos P, Maes L, De Bruyne T, Vanden Berghe D, Vlietinck AJ, Pieters L. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2007;14:417–430. doi: 10.2174/092986707779941005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Salman-Tabcheh S, Guerin M-C, Torreilles J. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 1995;19:695–698. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Weinreb O, Amit T, Youdim MBH. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 2007;43:546–556. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Santos-Gonzalez M, Gomez Diaz C, Navas P, Villalba JM. Experimental Gerontology. 2007;42:798–806. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Li M, Ma Y.-b., Gao H.-q., Li B.-y., Cheng M, Xu L, Li X.-l., Li X.-h. Chinese Medical Journal (Beijing, China, English Edition) 2008;121:2544–2552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Madian A, Regnier F. Journal of Proteome Research. 2010;9:3766–3780. doi: 10.1021/pr1002609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Madian AG, Regnier FE. Journal of Proteome Research. 2010;9:1330–1343. doi: 10.1021/pr900890k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Mirzaei H, Regnier F. Analytical Chemistry. 2005;77:2386–2392. doi: 10.1021/ac0484373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Mirzaei H, Regnier F. Journal of Proteome Research. 2006;5:3249–3259. doi: 10.1021/pr060337l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Mirzaei H, Regnier F. Journal of Proteome Research. 2006;5:2159–2168. doi: 10.1021/pr060021d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Mirzaei H, Regnier F. Journal of Chromatography, A. 2007;1141:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Madian AG, Myracle AD, Diaz-Maldonado N, Rochelle NS, Janle EM, Regnier FE. Journal of Proteome Research. 2011;10:3959–3972. doi: 10.1021/pr200140x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Stadtman ER. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2000;928:22–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Perez VI, Bokov A, Van Remmen H, Mele J, Ran Q, Ikeno Y, Richardson A. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, General Subjects. 2009;1790:1005–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Perez VI, Buffenstein R, Masamsetti V, Leonard S, Salmon AB, Mele J, Andziak B, Yang T, Edrey Y, Friguet B, Ward W, Richardson A, Chaudhuri A. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:3059–3064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809620106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Guevara R, Santandreu FM, Valle A, Gianotti M, Oliver J, Roca P. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 2009;46:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Bloomer RJ, Fisher-Wellman K. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:3–11. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Siu PM, Pistilli EE, Alway SE. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1695–1705. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90800.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Julka D, Sandhir R, Gill KD. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1993;29:807–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Wolf MB, Baynes JW. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2006;1760:267–271. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Migliore L, Coppede F. Mutat Res. 2009;674:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Rossner P, Jr., Svecova V, Milcova A, Lnenickova Z, Solansky I, Sram RJ. Mutat Res. 2008;642:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kucukakin B, Gogenur I, Reiter RJ, Rosenberg J. J Surg Res. 2009;152:338–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.12.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Ozguner F, Koyu A, Cesur G. Toxicol Ind Health. 2005;21:21–26. doi: 10.1191/0748233705th211oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Camargo AEI, Daguer DAE, Barbosa DS. Nutrition Research (New York, NY, United States) 2006;26:626–631. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Chung F-L, Xu Y, Jin C-L, Wang M. Food Factors for Cancer Prevention, [International Conference on Food Factors Chemistry and Cancer Prevention], Hamamatsu, Japan, Dec., 1995. 1997:130–133. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Perkins DN, Pappin DJ, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:3551–3567. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Gong Y, Li X, Yang B, Ying W, Li D, Zhang Y, Dai S, Cai Y, Wang J, He F, Qian X. Journal of Proteome Research. 2006;5:1379–1387. doi: 10.1021/pr0600024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Cho W, Jung K, Regnier FE. Analytical Chemistry (Washington, DC, United States) 2008;80:5286–5292. doi: 10.1021/ac8008675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Zhang Q, Ames JM, Smith RD, Baynes JW, Metz TO. Journal of Proteome Research. 2009;8:754–769. doi: 10.1021/pr800858h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Kaszkin M, Beck K-F, Eberhardt W, Pfeilschifter J. Molecular Pharmacology. 2004;65:15–17. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Kinae N, Masumori S, Masuda S, Harusawa M, Nagai R, Unno Y, Shimoi K, Kator K. Special Publication - Royal Society of Chemistry. 1994;151:369–374. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Wolfram S, Raederstorff D, Preller M, Wang Y, Teixeira SR, Riegger C, Weber P. Journal of Nutrition. 2006;136:2512–2518. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.10.2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Ounjaijean S, Thephinlap C, Khansuwan U, Phisalapong C, Fucharoen S, Porter JB, Srichairatanakool S. Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;4:365–370. doi: 10.2174/157340608784872316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Arteel GE, Uesugi T, Bevan LN, Gabele E, Wheeler MD, McKim SE, Thurman RG. Biological Chemistry. 2002;383:663–670. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Chai Y-M, Rhee S-J. Journal of Food Science and Nutrition. 2003;8:377–382. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Tejero I, Gonzalez-Garcia N, Gonzalez-Lafont A, Lluch JM. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129:5846–5854. doi: 10.1021/ja063766t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Chace KV, Carubelli R, Nordquist RE. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1991;288:473–480. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90223-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Yim H-S, Kang S-O, Hah Y-C, Chock PB, Yim MB. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:28228–28233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.47.28228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Nakagawa T, Yokozawa T, Terasawa K, Shu S, Juneja LR. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2002;50:2418–2422. doi: 10.1021/jf011339n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Babu PVA, Sabitha KE, Shyamaladevi CS. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2006;162:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Babu PVA, Sabitha KE, Srinivasan P, Shyamaladevi CS. Pharmacological Research. 2007;55:433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Waltner-Law ME, Wang XL, Law BK, Hall RK, Nawano M, Granner DK. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:34933–34940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204672200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Miura T, Koike T, Ishida T. Journal of Health Science. 2005;51:708–710. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Vinson JA, Zhang J. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2005;53:3710–3713. doi: 10.1021/jf048052l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Janle EM, Morré DM, Morré DJ, Zhou Q, Y Z. Journal of Dietary Supplements. 2008;5:248–263. doi: 10.1080/19390210802414279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Jhoo J-W. ACS Symposium Series. 2007;956:215–225. [Google Scholar]

- (53).Buetler TM, Renard M, Offord EA, Schneider H, Ruegg UT. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2002;75:749–753. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.4.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Gomikawa S, Ishikawa Y. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition. 2002;32:55–68. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Azam S, Hadi N, Khan NU, Hadi SM. Toxicology in Vitro. 2004;18:555–561. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Mustata Georgian T, Rosca M, Biemel Klaus M, Reihl O, Smith Mark A, Viswanathan A, Strauch C, Du Y, Tang J, Kern Timothy S, Lederer Markus O, Brownlee M, Weiss Miriam F, Monnier Vincent M. Diabetes. 2005;54:517–526. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.2.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Surinova S, Schiess R, Huttenhain R, Cerciello F, Wollscheid B, Aebersold R. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:5–16. doi: 10.1021/pr1008515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.